Abstract

After his return from Italy in 1608, Peter Paul Rubens received a commission to depict an Adoration of the Magi for the Statenkamer in Antwerp’s Town Hall. It was the first, grand display of his stylistic and iconographic innovations. By building on unexplored contemporary sources and close reading of the iconography, this article posits that Rubens’s canvas served as a questie on various matters under discussion at the time, and was designed to induce divergent affects in the beholders.

Johannes van Oldenbarnevelt and the Dutch delegation must have been speechless by what they first saw upon entering the Statenkamer in Antwerp’s Town Hall in the winter of 1609. On the wall, opposite the fireplace1, in a magnificent play of light and dark emboldened by vibrant colors, three magi entered the room to worship the newborn Messiah (Figure 1). Peter Paul Rubens had brought them all to life on a huge canvas. The painter had just returned from Italy. He had probably obtained the commission with the help of his brother, Philip, who served as the city’s secretary at the time. He was hardly known in the Low Countries, but that was about to change.2

Figure 1.

Peter Paul Rubens, Adoration of the Magi, 1609, canvas, 346 × 438 cm (original measurements: 256 × 381 cm), Madrid, Museo del Prado, inv.no. P-1638.

Originally 2.56 m high and 3.81 m wide—it was later enlarged by Rubens himself3—the Adoration of the Magi covered almost an entire wall of the room, where the peace negotiations among Spain, the northern Netherlandish Provinces, France and England were held. The war between Catholic Spain and the Calvinist Republic had long reached a stalemate. The king of Spain and the archdukes Albrecht and Isabella longed for a pause in the hostilities as did some in the northern provinces. The pragmatic Johannes van Oldenbarnevelt, who headed the delegation from the Dutch Republic, favored a truce. The stadholder of the northern provinces, Prince Maurice of Nassau, did not. Maurice distrusted the Spanish king and the ruling archdukes. However, under the watchful eye of the magi and their entourage, the separate delegations eventually reached an agreement on 9 April 1609 for a Twelve Years’ Truce. The Tractaet van t’Bestant (Treatise on the Truce) was signed and published for everyone to read.4 In the southern Spanish provinces, the truce would bring some welcome rest and prosperity, a situation Rubens hugely benefitted from, as he quickly became the favorite artist of the economic, religious and political elites. In the Dutch Republic, the truce caused an eruption of distrust between Van Oldenbarnevelt and Maurice, leading to a civil–religious clash between moderate and strict Calvinists. The Land’s Advocate of Holland, Van Oldenbarnevelt, who led the moderate faction, lost, was found guilty of high treason, and eventually executed. The strict interpretation of Calvin’s teachings was adopted in the Northern Netherlands, which from that moment on fully marched the path to independence. With the conclusion of the Peace of Münster, in 1648, the Dutch Republic would eventually become an independent state in which Calvinism was the dominant religion. Eighty years of war had come to an end.5

The Twelve Years’ Truce reinvigorated a debate that had lost some urgency in the previous decades. Almost immediately after t’Bestant was signed, the prolific Middelburg polemicist Willem Teellinck published a book to demonstrate the dangers of Catholicism, in particular ‘the grievous gaping at idols’.6 It was written for the ‘traveling men’ who considered visiting Antwerp and warned against the de ‘toverije’ (magic) and ‘hoererije’ (fornication) of Catholic art.

Teellinck, who had studied in Leiden and Poitiers and sojourned in England, had a habit of raging against just about every Catholic ritual. In a long tirade against ‘kermissen’ (saints’ days), he fulminated against the Adoration of the Magi too, which he considered to be fully idolatrous.7 He was the ardent Reformer, who has been dubbed the ‘father of the further Reformation’, a puritanical brand of Calvinism.8 As preachers and writers, he and other staunch Calvinists quickly assembled a significant following in the Dutch Reformed Church, resulting in substantial political influence in the young Republic, especially in the wake of the closing of the Twelve Years’ Truce. In the short dialogue Philopatris, for instance, Teellinck urged the Dutch government to adopt the stern principles of Calvinist Christianity,9 not without success.

A response was inevitable. Publishing under the pseudonym Divoda Iansen van Heylichen-Stadt, Johannes David replied with the Vry-Gheleyde, an invitation to the Reformed to do the exact opposite and come enjoy the tantalizing beauty of the Roman Catholic Churches in the Southern Provinces.10 David had been the rector of the Jesuit colleges of Brussels, Ghent and Antwerp and had published numerous polemical texts, most famously the Christeliiken Waerseggher (The Christian Fortune-Teller, 1603).11 Teellinck subsequently replied with De Ontdeckinge des vermomden Balaams (The Discoveries of Disguised Balaam, 1611), a voluminous refutation of David’s arguments, which was then again countered by the Postillon van de Roskam der vermomder Eselinne (Rider of the Curry Comb of the Disguised Jenny, 1611), David’s final shot at Teellinck.12

The series of books published by David and Teellinck were an opening salvo of another plethora of polemic texts and books on the issues of art and imagery, which had already divided public opinion in the Low Countries since the iconoclastic riots of 1566. The wound of that Beeldenstorm (Iconoclasm), to say the least, had not healed. In 1609, it was torn open again, bleeding discord. The barrage of publications on the matter of art and images would last until 1648, when peace would bring some political and religious stability.

Neither Rubens nor anybody else knew what was about to come, when in spring, 1609, the large canvas was installed in the Statenkamer for all delegates to enjoy.13 Yet, Rubens must have known what he was doing when depicting this most controversial scene. Nothing of this size, style and quality was to be found in the Low Countries at the time, when the arts were still recovering from the decimation of the second half of the sixteenth century. In the Beeldenstorm of 1566 and during the Stille Beeldenstormen (Silent Iconoclasm) of the Calvinist regimes in the late 1570s and early 1580s, an inestimable amount of religious works of art had been destroyed. Certainly, some capital pieces had been saved, and many new panels and canvases were produced in quieter times to refill the empty niches and replace the lost altarpieces, but those were all sculpted or painted in an outdated and controversial Italianate style, which harked back to the innovation of the pre-iconoclastic era. The Francken family, Maerten de Vos (Figure 2), Michael Coxcie or even Rubens’s own master, Otto van Veen, never succeeded in finding a truly innovative approach to tackling the many questions on (religious) art raised by the iconoclasm and by the tumultuous, ongoing public dispute surrounding it.14 Nobody knew what art was to be, let alone what it was to become.15

Figure 2.

Maerten de Vos, Adoration of the Magi, 1599, canvas, 320 × 248 cm, Valenciennes, Musée des Beaux-Arts, inv.no. P.46.1.16.

In the 1609 Adoration of the Magi, Rubens depicted his take on the matter. He introduced a grand new style, combining the innovations he had acquired in Rome, such as Caravaggio’s dramatic chiaroscuro realism and the Carracci’s compositional grandeur, combined with the finesse of execution from Netherlandish tradition and the best that antiquity had to offer. With his combination of compositional mastery, intellectual subtleness, and his ability to work so swiftly on such a large scale, he succeeded in producing a type of painting which struck a nerve.16 The Adoration of the Magi was his first salvo in a series of many and must have left a lasting impression on all delegates. From that moment on, Rubens was the undisputed crown prince of art, first in Antwerp and the Southern Netherlands, and quickly afterwards across the whole of Northwest Europe, even including the Northern Netherlands. Both Prince Maurice’s half-brother and successor, Frederick Henry, and his wife, Amalia van Solms, eventually succumbed to acquiring paintings by this new art star.17

As overwhelming as Rubens’s magnificent new style must have been to the Dutch delegation, just as challenging was the content. Teellinck was not the only one who detested the Adoration. Its subject raised everything that even moderate Calvinists had long shunned in religious art. The topic itself, for starters, vindicated one of the most controversial subjects in Netherlandish painting since the 1560s. To Calvinists the Adoration of the Magi was nothing less than ‘the sweet joke on which Catholic service was founded’, as a polemicist wrote in 1604.18 Indeed, ever since the fervent protagonist of the Dutch Revolt Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde had ridiculed the subject in his bestseller Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke (The Beehive of the Roman Church; 1569, frequently republished until well into the seventeenth century), the Adoration of the Magi was highly controversial.19 This popular subject had already accounted for nearly one in three paintings produced in Antwerp in the first half of the sixteenth century.20 Yet, after 1566 the subject was hardly depicted at all, and when it was, it served as commentary on the ostensibly false use of Matthew’s gospel verses (2:1–12) for Catholic propaganda. Adriaen Thomasz. Key, for instance, an Antwerp painter with documented Calvinist sympathies, omitted the black magus from the scene that he copied from his master Willem Key.21 According to Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, the idea that one of the ‘kings’ was ‘pitch-black as a Moor’ was patently ridiculous, as was the idea that there were three of them; that they were called Balthasar, Melchior and Caspar; and that they were kings.22 None of that was mentioned by Matthew, he argued, so it must have been a papist scam.23 Rubens apparently cared nothing about the controversy. He placed the black magus at the very center of the scene—at least on the canvas in its original state.

But there was more to the painting than meets the eye. Balthazar, as the black magus was called by Catholics, wears a cape of the most expensive azurite and a belt full of gemstones. On his turban, a stuffed bird of paradise (Apis Indica) flutters in the wind.24 It was believed that the bird of paradise had no feet and lived only in the air; therefore, according to Rubens’s contemporary, the popular French writer Pierre Boaistuau, people in the east considered the bird a symbol of the immortality of the soul.25 They adorned their helmets with the feathers of this species, according to the same author. The Turks, in particular, lauded birds of paradise as ‘manucodiata that is the bird of God’. By the time Rubens depicted the bird on the magus’s turban, it was well known in the Low Countries because of such books as Boaistuau’s and earlier representations of the Adoration, such as Hendrik van Balen’s 1598 painting.26 Jan Brueghel the Elder also depicted the bird of paradise around the same time as Rubens.27 Adding this divine bird to the turban, in other words, stressed the sanctity of the magus, generating yet another controversy.

These formal issues—concerning the number of magi, their names and whether they were holy, however important to both factions, as they testified to fundamentally different approaches to the history of Christianity—were not even the primary disagreements around the Adoration of the Magi. To Catholics, the scene was a prime example of God’s legitimation of devotion, including image devotion. Indeed, to Catholics, the Adoration of the Magi—Catholics would have called it Worship of the Kings—served as an important biblical argument in the image debates for two reasons. First, the biblical subject was advanced as a legitimation of the fact that ‘symbols’ such as the star were to be used to reference the divine and to serve as a means to access it. Protestants attacked Catholics relentlessly over the fact that they used animals, people, objects and other symbols to depict the undepictable. An old man, as the substitute for the invisible God, or a dove, as the Holy Spirit, were some of the most controversial examples. God as ‘an old man, dressed as your pope, from whose mouth a pigeon (comes)’, could it get more ridiculous, the bestselling author Johannes Florianus wondered in 1583.28 The fact that the wise men from the east followed a star (Matthew 2:1–12) was proof for Catholic theologians of the fact that God himself had endorsed symbols to guide the pious. Second, the gospel explicitly states that the magi worshiped Christ (Matthew 2:11) and brought him the gifts (offerings) of gold, frankincense and myrrh. In Rubens’s painting, Christ grabs a gold coin from Melchior’s cup.29 This gesture was seen as a legitimation of Catholic devotional practice in which pious offerings (ex votos) were common.

Gold, according to Johannes David, was the symbol of the kingdom of Christ; frankincense of his divinity; and myrrh of his humanity.30 Rubens’s famous syncretistic thinking is on full display here. In the brightest manner, he mixed the biblical references with antique symbolism. The box of myrrh is decorated with a double panther-griffin. This beast was associated with the cult of Sabazios, a Phrygian in antiquity, and it appeared frequently in imperial temples, where it served as a symbol of deification, human ascension to heaven.31 Sabazios was well known in Rubens’s day. Karel van Mander, for instance, mentions him, referring to Pausanias.32 But one could also read about Sabazios in Valerius Maximus’s well-known Memorable Deeds and Sayings. According to Valerius, in a chapter on superstitions, the first Jews were driven out of Rome by a law forbidding the cult of Sabazios.33 Thus, the reference to Sabazios was a nice syncretistic feat, since its reference to the antique deification of mortals reinforced the message of the canvas concerning the pagan religion of the magi. Moreover, it seems to have been familiar in the Low Countries. Sebastiaan Vrancx, for instance, used it in a temple garden scene.34

The importance of frankincense is stressed by the Black boy just behind the kneeling magus, who is blowing on the fire. 35 This act makes a clear reference to the Greek painter and contemporary of Apelles, Antiphilos, who, according to Pliny, depicted a wonderful painting of a boy blowing on a fire.36 Africans in Rubens’s oeuvre were associated with fecundity, joyfulness and even nigredo, that is, the first phase of spiritual alchemy.37 In early modern spiritual alchemy, something Rubens himself was certainly familiar with, it was a metaphor for the burning and putrefaction of the soul, the dark tunnel one had to cross to find a spiritual rebirth.38 In how far beholders of the canvas would have laid that link is more problematic. Spiritual alchemical knowledge was not as common as religious content, of course. Yet, together with the page in front, holding a torch, and the Christ child, they form a threesome of fire and light, a combination that does not seem to have been made haphazardly: Christ is the light himself; the other two figures manipulate it. Since early Christianity, fire and light were popular analogies to explain the complex Holy Trinity dogma.39 The symbol of fire had long been present in Adoration scenes in the Netherlands, such as the panel attributed to Jheronimus Bosch in the Metropolitan Museum.40

van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde’s quoted critique on Dry Coninghen (Three Kings) did not end with the problem of gift giving: ‘three Kings Night, when the good Catholics have fun and shout: the king drinks’; he ridiculed this important Catholic saints’ day, Twelfth Night.41 Indeed, beyond the visual richness of Rubens’s painting, there was more to deal with by the visiting Dutch delegation. In Catholic countries such as the Southern Netherlands, the magi (i.e., kings) were, indeed, celebrated on ‘dry coninghen avont’, a feast that was contested in the northern, Reformed provinces. While Calvinists loathed saints’ feast days in general, Twelfth Night—a title of Shakespeare’s contemporary play—was especially controversial. The reasons why can be read in one of Constantijn Huygens’s poems published in the booklet Heylighe dagen (Holidays), edited by Caspar Baerleus and first published in 1645.

‘Three Kings Night

Where is God’s only Child, so that I can worship it,

Oh Magi show me the way, I see a thousand stars show off

But none which guides me, as with wrong sparkles

I do not see the guiding star, on which your wisdom seen

While I gaze upwards, what mention do I hear

What does the lascivious city shout, drunk in opulence and wine, The King Drinks?

(…)’42

Huygens’s poem most eloquently paraphrases the common critique of the Catholic doctrine of the symbolic meaning of the star, mentioned above, and it strongly condemns the drunkenness common at the carnivalesque feast—much like Jacob Jordaens’s, David Teniers’s and Jan Steen’s depictions in later paintings.43 Obviously, Catholics opposed this view and kept on celebrating the saint’s day. Arguments to do so were already found in Joannes Tauler’s late mediaeval texts, which were republished in 1592.44 Tauler, a German mystic of the 14th century, extensively commented on Twelfth Night, explaining, among other things, how importantly the Nativity and the Adoration served as exempla of God’s desire to visualize himself in order to stimulate devotion. Tauler presented Dry coninghen avond and Dry coninghen dagh (Three Kings’ eve and Three Kings’ Day) as an allegory of the spiritual quest in search of God, and he paid considerable attention to the sense of sight (Epiphany of Christ, the son of God). In 1607, on the eve of Rubens’s commission, the staunch Jesuit Joannes David, whom we met above, published a book in which he explained to the lay audience the very essence of some crucial Christian iconographies: the Bloem-hof der kerckelicker ceremonien (The Flower Garden of Ecclesiastical Ceremonies).45 Chapter 33 deals with the Adoration of the Magi and Dry-konighen-dach. In the typical question–answer format of catechisms, he fiercely defended these celebrations and their symbolism: the star, the gift-giving and, indeed, the physical worship of the magi.46

Rubens’s iconographic experiments did not end with the topic itself, and its many controversial connotations did not either. The clothing he used to dress the magi was highly contentious too. In contemporary polemics, references to and attacks on clothing, in general, and Catholic or Reformed ceremonial clothes in particular, were common. In 1617, for instance, a translation of Lambert Daneau’s dissertation on clothing appeared in Dutch.47 The abandonment of sumptuousness drew special attention, because it was considered fundamental for a good Reformed Christian life to avoid all display of riches. In the Christycke Antwoorde (Christian Answer) to the highly popular treatises by De Launoy and Pennetier, Lambert Danneau and his translator, Johannes Florianus, devoted several pages to the ‘Cleedinge der papen’ (‘dress of the papists’) ridiculing De Launoy and Pennetier’s defense of the luxurious ‘sacramentalia’: ‘to wear or turn on the back of a chasuble or cope of velvet or gold thread as if one were a fool’.48 Harking back to the Catholic argument that Aaron, Moses’s brother and the first high priest, already wore exclusive garments or that the Romans wore such riches, Daneau and Florianus zealously opposed the ceremonial dress code of the Catholics, especially de ‘cappe’. Such chasubles had nothing to do, they added, with the ‘Latum Clavum’, which were worn by Roman senators and councilmen.49 The Reformed attack should not come as a surprise, since these Catholic polemicists had fiercely attacked and ridiculed the lack of decorum in Calvinist services. They wore jerkins decorated with garnishing and colors smelling like mussels, and a Scottish dagger while celebrating, even leather pants and a pistol at their belt plus a bag of stones to greet those who would dislike the service.50 The richness of the chasubles for Catholics, in contrast, served to enchant and instruct devout Christians; hence, the figurative embroidery. Its weight symbolized the weight of the cross—probably the reason it is typically depicted as analogous to Christ stumbling under the weight of the cross. That analogy was detested by Protestants, who considered it as a disrespectful dress-up party.51

To demonstrate the ubiquity of the scorn and its very essence, it is worthwhile to refer to another text by Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, entitled Tafereel der religions verschillen, that is, Display of the differences of opinion. In a chapter on the disputed authority of the pope as the designated heir to Saint Peter’s throne, the famous protagonist of the Dutch Revolt ridicules the Catholic preference for ‘tast’ and ‘sien’, i.e., touch and sight, using the exorbitant chasubles of the princes of the church as prime examples.52 Since the Catholic Church wants a head who is both ‘sienlijck ende rakelijck’ (‘seeable and touchable’), it cannot be genuine faith, the argument goes.

Another symbol of priestly authority worn by Catholic priests during mass and also dismissed by Calvinists as a scam, a stole, lay under Christ’s feet, draped over the edge of the manger. Irritation regarding the use of stoles and chasubles could already be found in Dutch treatises on religious issues in the middle of the sixteenth century; it increased in times of iconoclasm and was still very present during Rubens’s times.53 In the eighth sermon of his Sermoonen op de Epistelen van de Sondaghen des gheheelen laers (Sermons on the Epistles of the Sundays of the Entire Doctrine; 1616), the Jesuit Franciscus Costerus once more explained the meaning of the stole.54 This ‘stoole’, Costerus wrote, symbolized the yoke of original sin and man’s obedience to God. A scam, the reformed Franciscus Alardus had long before argued.55

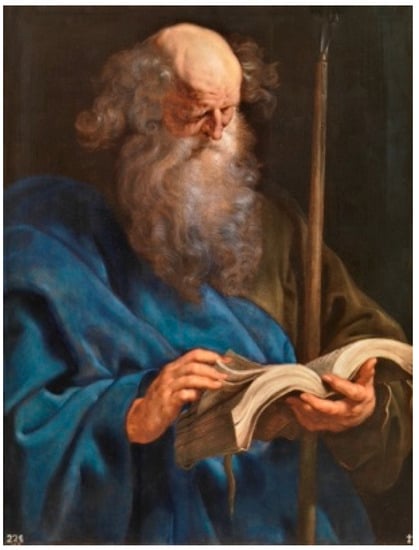

Caspar, the magus on the right, wears a cardinal’s red garb. A page holds the magus’s hat, whose ribbon and plush suggest a resemblance to a cardinal’s hat. This magus’s physiognomy, interestingly, is identical to Saint Thomas’s, as used by Rubens in his more or less contemporary Apostle series (Figure 3). No doubt, this was intentional. After Pentecost, when the apostles spread around the world, Saint Thomas travelled to the east (India), where in Rubens’s day a community of Saint Thomas Christians still existed and was being brought under Catholic rule.56 Hence, he fought idolatry and baptized the magi, according to Saint John Chrysostom, before he eventually died a martyr.57

Figure 3.

Peter Paul Rubens, Saint Thomas (Apostle series), 1612–1613, panel, 108 × 83 cm, Madrid, Museo del Prado, inv.no. P-1654.

Bending over and leaning on a stick, a soldier in contemporary Habsburg armor joins the Adoration. His presence fully shatters the illusion of antiquity. Both the man and his armor closely resemble the Portrait (?) of a Commander Being dressed for Battle by two pages by Rubens, tentatively dated to 1612.58 The richness of his battle dress refers to the high nobility of the mid-sixteenth century, when such armor was in fashion. If the illusion of contemporaneity was not yet triggered by the clothing of the magi and their pages, this armored man erases all doubt: a religious war was being fought in which the Adoration has become a major bone of contention.

Beyond the clothing, two more details hint at contemporary issues. The bizarre pose of the Christ Child, supported by the white linen cloth, is traditionally explained as a reference to the Descent from the Cross, the moment in which the dead body of Christ was enfolded in a shroud.59 The white linen was nothing new and, indeed, references Christ’s death as even Marnix van Sint Aldegonde acknowledged.60 It was to be found in Antwerp depictions of the Adoration since the early sixteenth century. Around that time, painters also start to depict the Virgin holding up one or two corners of the cloth as if she was to be identified with Saint Veronica holding the Vera Icon. This eventually led to paintings in which the newborn was fully associated with the Vera Icon.61 Rubens, on the other hand, used the rolled-up linen as a support for the Christ Child, as if the holy Virgin is holding up the son of God, his legs crossed (a not-so-subtle anticipation of his death). He does not suggest the holy shroud but seems to refer to childbirth itself and the suffering of the mother. In rare depictions of actual birth-giving in early modern Europe, as in some manuscript illuminations (Figure 4), one can see how such a cloth was used by the mother during the actual labor. Whether Rubens did, indeed, refer to birth labor is impossible to know, but the uniqueness of this iconographic feat stands out. Even in his own later depiction of the Adoration, he would not repeat this detail, instead returning to more traditional representations.

Figure 4.

Olympias giving birth to Alexander the Great, in: Augustine, La Cité de Dieu (Vol. I). Translation from the Latin by Raoul de Presles, Maïtre François (illuminator), Paris, c. 1475, The Hague, Royal Library, MMW, 10 A 11 fol. 233v.

However, the mere fact that Mary so obviously upholds the son of God is telling. Within the multifaceted theological debates between Catholics and Protestant, the veneration, even the adoration, of the Holy Virgin played a crucial role. Was she the ‘Mother of God’ or just a pious woman giving birth to Jesus, the man in whom God would reveal himself? In 1604, Rubens’s own intellectual mentor, Justus Lipsius, took the issue center stage with his publication Diva Virgo Hallensis.62 Originally published in 1604, Justus Lipsius had lauded the miraculous sculpture of Our Lady of Halle. The booklet was an immediate bestseller and sparked fierce response from Protestants. Already in 1605, it was falsely translated in Dutch as ‘Heylige Maghet van Halle’, to serve as a ‘mocking of Papal Roman Idolatry’.63 It pressed the staunch Catholic Philips Numan to publish a genuine translation in Dutch in 1607, but by that time the quarrel was already out of control.64 Other booklets, such as ‘Des Halschen Afgodts’, were published, and many a Reformed author used Lipsius’s title ‘diva virgo’ to argue that the Catholics had finally and publicly acknowledged the idolatrous nature of their veneration, i.e., worship, of the Virgin. The Virgin Mary had been called divine, her image was worshiped and considered miraculous. How could that be reconciled with the Second Commandment? As a response, Lipsius wrote a similar eulogy of the Madonna of Scherpenheuvel, published in 1605.65 This fierce polemic impelled the archdukes to heavily invest in the cult of both miraculous Madonna sculptures, with the newly built Basilica of Scherpenheuvel (consecrated 1627) as its culmination.66 Until deep in the seventeenth century, the debate went on.

Willingly—or unwillingly?—Lipsius had brought (religious) art’s two most controversial issues back to the forefront: ‘sien’ and ‘tasten’. His work prompted a new wave of intense image debates, with more participators and even more publications than the Netherlands had witnessed in the wake of the Beeldenstorm. By addressing the miraculous qualities of the ‘Halschen afgodt’, Calvinists could now equate Catholic image devotion, in particular toward the Virgin, with the worship of Diana of Ephesus, who from that moment on would serve as the pagan alter ego of the Madonna.67 Lipisus’s booklet caused a flood of syncretic publications in which Catholic and pagan rites were equated by Reformed polemicists. Cyprianus and Tertullianus were dusted off once more to finally prove that Catholic image devotion was pure idolatry.68

By stressing the motherhood of the ‘Mother of God’, Rubens accentuated her ‘divinity’, the womb from which the Son of God was born, and a crucial key of Salvation: the Second Covenant. Hence, the introduction of cherubim in nativity scenes as, for instance, in Huybrecht Beuckeleer’s Nativity (Figure 5). God had ordered the Jews to decorate the Ark of the Covenant with cherubim, the ultimate Catholic argument in the image debates: God himself had ordered the pious to make images, something even staunch Protestants had to acknowledge.69 However, what is interesting here is that Rubens evokes Catholic and pagan tradition to forward the Madonna as a quintessential figure in Christianity, supporting the newborn Jesus. As such he confirms her special status.

Figure 5.

Huybrecht Beuckeleer, Nativity, 1663, panel, 110 × 141 cm, Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation.

The well-rooted idea in the scholarly literature that Peter Paul Rubens’s Adoration of the Magi was to serve as an allegory of the economic prosperity and diplomacy that was about return to Antwerp, as was first proposed by Frans Baudouin and expanded upon by Julius Held, Hans Vlieghe and Joost Vander Aurera, may hold some truth, but it cannot suffice to understand how the delegates must have responded to the iconography.70 Surely, at first sight, both the topic and the iconography were tactful. To the Catholic delegations from the Southern Netherlands and France, the richness and splendor of Rubens’s canvas will neither have come as a surprise nor will it have been too controversial. To Van Oldenbarnevelt and his fellow negotiators, however, the canvas must have created at least some unease. They probably had not observed the magnificence of a Catholic Mass for ages, if they ever had. The gold brocade glittering under candlelight, the shiny red velvet, the gold vessel, and the associations it evoked must all have felt awkward to them, especially in a painting of such scale, hanging at eye level in a room in which they had to settle a complicated truce in a devastating religious war. When not negotiating, the different delegations must have had much to discuss when standing in front of Rubens’s Adoration other than the return of prosperity. Much more than the portraits of the Burgundian dukes on the adjoining wall, Rubens’s canvas was the eye-catcher, almost as ‘sienlijck ende rakelijck’ (visual and palpable) as Catholicism itself.

However, to typify the majestic canvas as arrogant Catholic propaganda, a feat typically associated with Rubens’s art, might be jumping to conclusions. At the very center of the canvas, in its original state, is the blonde young angelic page with the torch.71 Because of foreshortening, it appears as if he holds it in front of the image plane, lighting the scene itself. He awkwardly holds it backwards, thumb down. While Rubens saved no effort to depict the porters on the right-hand side as naturalistically as possible, showing the tension in their bodies in every muscle, he depicted the beatific boy’s arm most unnaturally. No one, under normal circumstances, would hold a torch like that. Rubens even changed the position of the hand from his preliminary sketch (Figure 6) in which he depicted the page holding the torch straight, his thumb up.72 He clearly deemed it necessary to change to position of the hand, suggesting that the boy originally held his torch upside down and then turned it or that he is about to turn it down. The centrality of this motif and the fact that the awkward twist of the arm would have been in full view if the canvas were hung at eye height suggest that the odd but deliberate change must have been highly meaningful.

Figure 6.

Peter Paul Rubens, Oil sketch for the Adoration of the Magi, 1608–1609, panel, 54.5 × 76.5 cm, Groningen, Groninger Museum, inv.no. 1931/121.

The idea for this pose may have been born from several sources. One plausible option is that Rubens consulted Ceseare Ripa’s Iconologia when making the change. Ripa described the allegorical rendering of crepuscolo della mattina (twilight of the morning) as a young boy holding a torch upside down (Figure 7). In the 1603 Roman edition of this very popular book, the morning twilight was described as the ‘moment of doubt’ between night and day, i.e., the time Rubens depicted in the background, where the sun carefully breaches the dark, cloudy sky.73 Light and dark are in limbo, the young angelic boy being the judge of it all. Given the fact that the canvas was to hang against the backdrop of the negotiations, it is tempting to think of the gesture as a most intelligent allusion to the crucial make-or-break moment, a choice between night and dawn indeed.

Figure 7.

Crepuscolo della mattina, in: Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, overo Descrittione di diverse imagini cauate dall’antichità, & di propria inuentione, Ripa (1603, pp. 95–96).

However, the inverted burning torch was also to be found in Roman antiquity, as an attribute to Somnus, the genius of sleep, or Anteros, Eros’s brother and the deity of love reciprocated.74 A famous example in Rubens’s time was a Sarcophagus with Prometheus and Athena Creating the First Humans, in which one can discern Eros holding his torch upside down over a deceased (?) man.75 In antiquity, Amor leaning on an inverted torch was quite common, also serving in the iconography of death.76

Yet, the most plausible source of inspiration was probably Otto Van Veen. Rubens’s former master used the inverted torch in his Amorum Emblemata of 1608, the year when Rubens returned from Italy and received the Adoration commission. In this best-selling booklet, Vaenius published a picture (Figure 8) with Amor holding his torch upside down (his hand straight) accompanied by the brief heading and poem: ‘QVOD NVTRIT, EXTINGVIT’, or in Dutch: ‘MIJN VOEDTSEL DOODT MY’ (My Nourishment Kills Me).77 Van Veen, moreover, had himself borrowed the emblematic figure from Daniël Heinsius, who in 1601 (republished, 1608) had used it in his emblem book under the motto: ‘QUI ME NOURRIST, M’ESTAIND.’78

Figure 8.

Quod Nutrit Extinguit, in: Otto Vaenius, Amorum Emblemata, Vaenius (1608, pp. 190–91).

The chances are that Rubens used this complicated allegory on love, life, and death by Heinsius or his former master Van Veen to add a riddle to the iconography, using the twisted hand of the young angelic boy as an invitation to the delegates to ponder the necessary of their passionate love for Christ and its consequences: life and death, indeed.

What Rubens might have meant with the twisted hand remains open for discussion, and it would not be surprising if that was exactly his learned intention. Diplomacy is about finding common ground on controversial questies (issues), as they would have said in Dutch. Nothing could serve such a purpose better than the quaestio, the question itself, as the humanist Rudolphus Agricola stated in his books on Dialectic. The quaestio to him was an art and, as such, the foundation of all thinking.79 Humanists followed suit, and Rubens too.80 Rubens used the boy, it seems, to question the controversies themselves, inviting the delegates to reflect on the central matter. For, indeed, the introduction of the twisted hand is much more than an awkward inconsistency. The twist of the hand, therefore, is a great metaphor, of both Rubens’s approach to iconography and the historiography of the iconography of the Adoration of the Magi itself. In the bibliography of this canvas, nearly all attention has been devoted to the intentions of the artist and (to some extent) his patrons. The constrained, simplified reading of the iconography as an allegory of the return of prosperity is the partial result of that approach. Instead of considering the manifold emotional and cognitive associations that various details in the iconography must have provoked in contemporary beholders (the ‘period eye’), the focus has fixed on a generic interpretation of the theme itself. In an age of iconoclasm and image debates, however, the impact of art on the whole of society was equally important to the qualities required for its production, since art was already one of the most controversial and defining religious issues at the time. For if the iconoclasms of the sixteenth century had demonstrated anything, it was that art was not neutral, indeed, that it could enflame society and, ultimately, lead to war. In the Low Countries of the later sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, expectations concerning art, by far, exceeded intentions, especially when it came to religious art. The chances that Van Oldenbarnevelt and the other delegates from the Dutch Republic, to focus on them, were first and foremost inclined to ‘read’ the Adoration of the Magi as an allegory of the return of prosperity, as typically proposed in the literature, are extremely low. Most certainly, the delegates were eager to conclude a truce and reinvigorate the economy too, but their religious background and the age-old controversy on the topic must certainly have prevailed upon seeing the huge canvas for the first time. To them, such a canvas carried a bombshell of emotional and cognitive considerations and associations, generating bewilderment at first and a multifarious network of thoughts later. It provided a provocative invitation to contemplate one of the most fundamental questies of the conflict: the difference—however subtle—between genuine worship and idolatry.

Rubens’s Adoration of the Magi, in other words, testified to what his good acquaintance Franciscus Junius later defined as an important quality of invention: ‘a perfect and exactly handled invention must bud forth out of a great and well rooted fulnesse of learning’.81 It offered a multitude of ideas to ponder. Yet, depending on the background of the beholders, the imagery triggered completely different emotional and cognitive responses, even trains of logic. No doubt, later on in the royal gallery of Madrid in the late 1620s, where the canvas eventually ended up, none of the resentment for the subject that must have been present in the Antwerp town hall in April 1609, could be sensed. Hence, Rubens’s artistic genius could be discussed at length, perhaps as an image embodying the sensuous joy of Catholicism.

Indeed, three years after its completion, the canvas was presented as a gift to the Spanish ambassador Rodrigo Calderón, Conde de la Oliva de Plasencia, Marqués de Siete.82 Calderón, a favorite of the king, moved the large canvas to his residence in Spain, whence, after his downfall and execution in 1621, it was again moved, this time to the Spanish royal collections. When Rubens visited Madrid in 1628, he enlarged the canvas adding the angels above and the figures and animals on the right, including his own self portrait. As Elizabeth McGrath correctly observed, the canvas was no longer a public work with a civic religious meaning; instead, it was a gallery picture to be enjoyed by the happy few in the context of Spanish politics and leisure.83 The chances that King Philip IV of Spain and his guest would be confounded by the iconography, as the delegates of the republic probably were twenty years earlier, were virtually nil. The canvas now fully served the idea of richness, prosperity and orthodox faith under Habsburg rule. Its ‘use’ and context were entirely altered and, as a result, its perception. Rubens apparently deemed it necessary to alter the canvas to fit its new purpose with his added a strip on the right-hand side and on top. As a prominent witness, the knighted painter could look back upon his own, exceptional feat two momentous decades later.

As the example of the Adoration of the Magi shows, dealing with Rubens iconographies is always difficult, since they work associatively on so many different levels. Not only do they testify to an uncommon knowledge of northern, Italian, and antique prototypes, but they also typically combine with exceptional erudition Greco-Roman and Christian themes. This combination of qualities makes it tempting, on the one hand, to project all sorts of ‘meaning’ into Rubens iconographies, but it also must, on the other hand, warn us to be cautious. Rubens’s own learning was uncommon, though it does not explain the immense popularity of his oeuvre. No painter before or after him succeeded in producing, let alone selling, so many inventions and copies as Rubens did: thousands and thousands. Rubens’s artistic and economic success cannot be explained by focusing solely on his ‘genius’, as is so often the case in the historiography of his life and oeuvre.84 Rubens is generally considered a master who was able to create the most witty and inspiring intellectual challenges with swift brushstrokes. Rightly so, but his inventions would not have been successful if they did not appeal to the broadly shared intellectual and artistic concerns of the society he lived in. Consequently, the appeal of Rubens’s immense oeuvre to his contemporaries cannot be understood only by delving deep into the innumerable, recondite, often elitist and hermetic antique sources, which Rubens himself read and used. A painter who could sell thousands of expensive panels and canvasses must, at least, have appealed to common interests, emotional and cognitive, not only in Antwerp but far beyond the city gates. Or phrased differently: Rubens did not create the context; he excelled in it. He was immensely successful in adapting to it artistically, intellectually and economically.

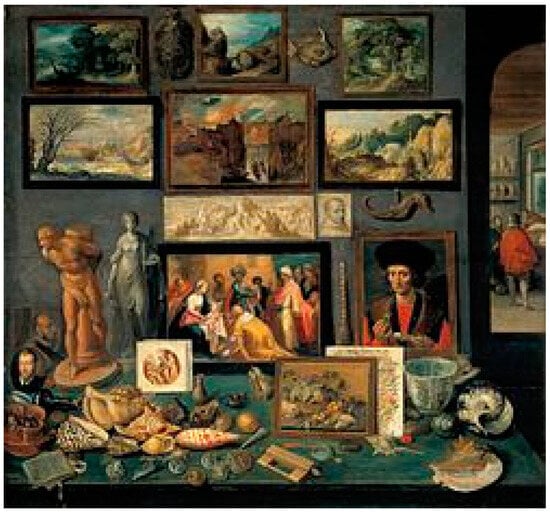

Surely Rubens’s innovative style, which was a well-balanced combination of northern and southern traditions and antique prototypes, was part of his achievement, but the content he added to his well-conceived compositions must have been significant too. After all, if discussing the arts and the art of painting was the kind of pastime the city elites in the (southern) Low Countries enjoyed—as one can see in progress within the many contemporary art cabinet paintings (Figure 9)—it is conceivable that they not only discussed paintings’ artistic or stylistic qualities but also showed some interest in the subtle iconography. Interestingly, many of these cabinets display an Adoration of the Magi as its centerpiece. After all, the image debates in the Low Countries were not a debate about stylistic issues; instead, they engaged in an intense dispute on ‘sienlijck ende rakelijck’, on touch and sight, and on use and perception. Strongly zooming in on iconographies (as Molanus did and Paleotti planned to do),85 as well as how these subjects were to be used, was part of that process.

Figure 9.

Frans Francken the Younger, Art Cabinet, 1636, Panel, 74 × 78 cm, Vienna, Kunsthistorische Museum, inv.no. GG_1048.

Unlike Italian art theories of the early Renaissance, the later sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century image debates in the north made the beholder accountable for art too, a semiotic turn, so to speak. The image debates were not manuals or guidelines on how to create art. They were admonitions to the beholders of art on how to assess it, urging for careful consideration of the questies at stake. They lay responsibility for understanding in the eyes of the beholder. This paradigmatic turn Rubens understood like nobody else. With something as simple as a twisted hand, he used the cognitive–emotional affects to eventually question themselves, reflexively. A brilliant example of Stoicism some would say, prohairesis even.86

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Above which Abraham Janssen’s Scaldis and Antverpia hung (panel, 174 × 308 cm, Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts). |

| 2 | For analyses of this painting see (Vergara et al. 2004; Devisscher and Vlieghe 2014, pp. 110–23). |

| 3 | Garrido and Márquez (2004, pp. 141–54). |

| 4 | Tractaet van ‘t Bestant/ghemaeckt ende besloten binnen de Stadt ende Cité van Antwerpen/den negensten Aprilis 1609. voor den tijt van twaelf jaren/tusschen de Commissarisen van de Serenissime Princen/Eertzhertogen/Albert ende Jsabella Clara Eugenia/so wel inden naem vande Majesteyt Catholijcke/als den haren: met de Commissarisen ende Gedeputeerde vande Jllustre Heeren Staten Generael vande vereenichde Provincien der Nederlanden: ende dat door het tusschen-comen/ende met advijs vande Heeren Ambassadeurs vande Coningen den Alder-Christelicksten/ende van groot Bretaignien, The Hague: Hillebrant Iacobsz., 1609. |

| 5 | On the Eighty Year War see for instance (Groenveld and van Leeuwenbergh 2008). |

| 6 | ‘het verdrietelijck begapen der afgoden’; Teellinck (1609, 1648). |

| 7 | Teellinck (1624, part 1, pp. 10, 15). |

| 8 | Willem Teellinck, it must be noted, was well acquainted with Franciscus Junius the Elder, a theologian who had studied under Calvin and Beza in Geneva and served as a professor of theology at Leiden University. More importantly here: Junius the Elder was the father of Franciscus Junius the Younger, the philologist and writer who published De Pictura Veterum in 1637, a compendium and analysis of the painting of the ancients which was lauded by humanist scholars, including Peter Paul Rubens. Junius junior frequented the same intellectuals and noblemen in England as Rubens did, when he entered the service of the Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (1620), for whom he also acted as the curator of his collection of Antiquities. On Teellinck see: op ‘t Hof (2008). |

| 9 | Teellinck (1608). |

| 10 | David (1609). |

| 11 | David (1603). On Johannes David see i.a.: (Sors 2015, pp. 46–48; Snellaert 1878). |

| 12 | Teellinck (1611); David (1611). |

| 13 | I follow the analysis of the timeline as published in the CRLB. Devisscher and Vlieghe (2014, pp. 110–23). |

| 14 | Vlieghe (1998, pp. 4–10). |

| 15 | Jonckheere (2012). |

| 16 | A nice and recent perspective on Rubens creativity is Marr (2021). |

| 17 | van der Ploeg and Vermeeren (1997). |

| 18 | ‘de soete cluchten waerop haeren dienst ghefondeert is’; Syverts (1604) voorreden. |

| 19 | van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke, s.l. 1569 (re-edition: s.l., 1597), fol. 143v |

| 20 | Ewing (2004–2005, pp. 275–99). |

| 21 | Jonckheere (2012, pp. 264–65). |

| 22 | ‘coninghen’, ‘peck-swart als een Moriaen’; Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke, s.l. 1569 (re-edition: s.l., 1597), fol. 143v. |

| 23 | Another scam was, according to Marnix, that they depicted Longinus at the Crucifiction, piercing the body of Christ. Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke, s.l. 1569 (re-edition: s.l., 1597), fol. 144r. Note Rubens’ famous Coup de Lance (before 1620, canvas, 429 × 311 cm, Antwerp, Royal Museum of Fine Arts). |

| 24 | Marcaida (2014, pp. 112–27). |

| 25 | Dutch translation: Boaistuau (1608, pp. 136–39). There were many more editions. |

| 26 | ‘manucodiata, dat is de voghel gods’; Boaistuau (1608, pp. 136–39). Birds of paradise were not only an exotic breed, imported from the East-Indies, it was also a constellation discovered in the east, and first published in 1598 by Petrus Plancius, a reformed Flemish-Dutch astronomer. The publication drew a lot of attention around 1600. |

| 27 | E.g., Jan Brueghel the Elder, Landscape of Paradise and the Loading of the Animals in Noah’s Ark, 1596, copper, 27 × 35.5 cm, present whereabouts unknown (Sale Sotheby’s New York, 25 January 2015, lot 54). |

| 28 | ‘eenen ouden Man ghecleedt als uwen paus, wt wiens mondt schijnt een jonck Duyfken (…)’; Johannes Florianus (Daneau and Florianus 1583), Christelycke antvvoorde op den eersten boeck der lasteringhen en vernieude valscheden van twee apostaten Mattheeus de Launoy, priester, ende Hendrick Pennetier, die eertijdts ministers gheweest hebben, ende nv wederom tot hare vuytghespogen vuylicheyt, ghekeert zijn […] Nu eerst vvt het Francoys getrouvvelijck ouergeset door Ioanne[m] Florianu[m] […] Midtsgaders een stichtelijcken brief Thomae Tilij […], Antwerpen (Niclaes Soolmans), (1583, p. 82). |

| 29 | Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke, s.l. 1569 (re-edition: Delft: Bruyn Harmansz. Schinckel, 1611), s.p. (Aen den eerweerdighen, heylighen ende hooch-gheleerden (…) Franciscus Sonnius). The use of gold and frankincense in Catholic Mass was a strong bone of contention too, or as it was phrased in the ironic dedication of the 1611 Delft edition of Philips van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde’s Byen-korf: ‘De Sancten en creghen gheen Vette Offerhanden/gheen Wieroock—brandt/noch gheen Bedevaerden meer: Jae men bestonde alreede hare beelden van de altaren af te werpen (…) In somma, alle het heylichdom der Roomsche Catholijcksche kercke, beghonde in de Asschen te vallen’. |

| 30 | David (1607, p. 134). See also John 19:39. the anointing oil was used to treat Christs body after his death. |

| 31 | Allan (2004, pp. 113–55); https://art.thewalters.org/detail/3446/sarcophagus-with-griffins/ (accessed on 8 July 2023). |

| 32 | van Mander (1615), fol. 49v. |

| 33 | Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, Book 1,3 (Of Superstitions). |

| 34 | Sebastiaan Vrancx, Temple-garden scene, Collection of the City of Antwerp, Rubens House, inv. nr. RH.S.078. |

| 35 | Bialostocki (1988, pp. 139–44). |

| 36 | Pliny, Naturalis Historia, 35, 138. |

| 37 | Esposito (2008, 2020); On black people in Rubens’ oeuvre see: McGrath (2018, pp. 291–316). |

| 38 | Rubens famously made note on it in his notebook; Esposito (2008). |

| 39 | E.g., Evans (1976, pp. 46–57). The analogy typically consists of Sun/Flame, Light and Heat. |

| 40 | Bosch (1913). |

| 41 | ‘dry Coninghen avont, als de goede Catholijcken hen vrolick maecken ende roepen: De Coninck Drinckt.’; van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde (1611), Schinckel, s.p. |

| 42 | ‘Dry Coninghen Avond/Waer is Gods eenigh Kind, dat ick ’t aenbidden magh?/O, wijsen, wijst mij ’tpad. ’ksie duijsend Sterren proncken/Maar geene die mij leid’ als met verkeerde voncken./Ick sie de Leid-sterr niet daerop uw wijsheid sagh./Terwijl ick opwaerts gaep, wat hoor ick voor gewagh?/Wat roept de wulpsche stadt, in weeld en wijn verdroncken, De Coningh drinckt? Wegh, wegh, de Coningh heeft gedroncken,/En drinckende voldaen het bittere gelagh,/’Tgelagh van Gall en Eeck, dat gheenen mond en monden,/Daer geen keel teghen mocht, van die daer kopp en keel/En ziel en all verbeurt bekenden voor haer sonden./Nu treed ick moedigh toe met all mijn wonden heel./Komt, wijsen, ‘kweet het pad; all is het steil en verre,/Ick vrees den doolwegh niet, ‘tKind selver is mijn’ Sterre.’; On this poem, the manuscript and its editions see: Strengholt (1974, pp. 46–47); van Strien and Stronks (1999, pp. 143–44). |

| 43 | Irene Schaudies, ‘Jacques Jordaens’s Twelfth Night Politics’, in: DiFuria (2016, pp. 67–98); Westermann (1998). |

| 44 | Tauler (1593, vols. 50v.–58v). |

| 45 | David (1607, pp. 133–35). |

| 46 | Ivy, depicted by Rubens on the wall of the ruins, was a plant associated with twelfth night, as is evidenced in Jordaens later painting of the subject. ‘De onverwelkbare klimop’, as Joost van den Vondel would call it in 1613, was moreover associated with the east, purity and painting itself. See: van den Vondel (1647, pp. 366–67). |

| 47 | Daneau and de Swaef (1617). |

| 48 | ‘op den rugghe een Casuyfel oft Coorcappe, van flouweel of goudtlaen te hebben, hem te draeyen, keerenn ende wenden, oftmen eenen Sot ware’; Daneau and Florianus (1583, p. 392). |

| 49 | Daneau and Florianus (1583, p. 394). |

| 50 | De Launnoy and Pennetier (1578), fol. 73v. |

| 51 | van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde Byencorf der h. Roomsche kercke, s.l. 1569 (re-edition: s.l., 1597), fol. 160–161. |

| 52 | van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde (1601), Cloppenborg, fol. 61r. |

| 53 | E.g., Sleidanus (1558, pp. 326–28); van Hattem (1611, pp. 95–96). |

| 54 | Costerus (1616, p. 216). |

| 55 | Alardus (1566, 1610, p. 25). |

| 56 | Vadakkekara (1995). |

| 57 | Rubens’ re-use of a tronie in this case, was an interesting iconographical feat. |

| 58 | Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait (?) of a Commander Being dressed for Battle by two pages, c. 1612–1613, 122.6 cm × 98.2 cm, On loan to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2023). |

| 59 | In an obvious over-interpretation of the scene the cauldron was forwarded as a metaphor for the birth of artistic genius. Nemerov (2013, pp. 238–47). |

| 60 | See note 51. |

| 61 | E.g., Matthias Stom The Adoration of the Magi, between 1633 and 1655, canvas, 149 × 182.7 cm (sale Bonhams London, 5 December 2018, lot 21). |

| 62 | Lipisus (1604). |

| 63 | ‘bespottinghe der Pauselicke Roomsche Afgoderije’, (van Oosterwijk 1605). |

| 64 | Numan (1607). |

| 65 | Lipisus (1605). Translation: Philips Numan, Mirakelen van Onse Lieve Vrovwe, ghebevrt op Scherpen-heuuel, zedert den lesten boeck daeraff buytghegheuen, met eenighe andere die eerst onlancx tot kennisse zijn ghecomen, Brussels Rutgeert Velpius and Huybrecht Anthoni, 1614. |

| 66 | Duerloo and Wingens (2002). |

| 67 | E.g., De Halschen Afgodts, van Justus Lipsius, s.l., 1605, passim. |

| 68 | On the re-use of early Christian and Byzantine debates in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century see: (Freedberg 1988). |

| 69 | E.g., vander Schuere (1581), fol. 76–82. |

| 70 | See for this reading of the iconography and its historiography: Devisscher and Vlieghe (2014, pp. 110–23). Fucci recently pointed our attention to the circumstances, underscoring the economic importance of the Truce and relating it to the iconography, and pointing out that other treatises on trade were negotioted and signed in the same room later on (Fucci 2019, pp. 75–88.) |

| 71 | This is also the case on the copy which shows the canvas in its original state. Anonymous after Rubens, The Adoration of the Magi, London Private collection. See on this copy: Vergara (2004, pp. 65–67). |

| 72 | Devisscher and Vlieghe (2014, pp. 126–29). |

| 73 | Ripa (1603, pp. 95–96). |

| 74 | See Bober et al. (2010). |

| 75 | Rome Capitoline Museums, inv.no. MC329. |

| 76 | Aristodemou (2021, pp. 25–42). |

| 77 | ‘Het was den fackel voet/en blust sijn vlamme mede/Als die werdt omghekeert/Cupidoos hette groot Den minnaer onderhoudt/en brenght hem oock ter doodt. Na dat sijn lief verhoort/of van haer stoot sijn bede.’ Vaenius (1608, pp. 190–91). |

| 78 | Vt qua nutritur pinguedine tæda liquescit,/Quâ vivo, & nutrior, quam pereo, hâc pereo./Het ghene dat de torts/ontsteeckt/en doetse branden/Dat zelve blust se weer als m’ommekeert zijn handen’Daniël Heinsius, Emblemata Amatoria, s.d. (probably 1601), 2nd edition Amsterdam: Dirck Pietersz., 1608, s.p. emblem 5. |

| 79 | Agricola and Mundt (1992, pp. 229–35). |

| 80 | For the impact of the question on thinking and art in the case of Rubens see Jonckheere (2019, pp. 72–99). |

| 81 | Junius (1638, p. 232). |

| 82 | For its further provenance see: Devisscher and Vlieghe (2014, pp. 110–11). |

| 83 | E. McGrath (McGrath 2018), ‘Review of Rubens. The Adoration of the Magi, by A. Vergara, H. Cabrero, J. García-Máiquez, C.’, in: The Burlington Magazine, 147, 1233 (2005), pp. 831–32. |

| 84 | See Marr (2021) especially the preface (pp. 7–13) offers an excellent introduction to this issue. |

| 85 | Molanus (1570). Recent annotated edition: (Molanus 1996); Paleotti (1582). A recent annotated edition: (Paleotti 2012). |

| 86 | On Rubens and Stoicism: (Morford 1991). The term prohairesis in Epictetus refers to judgment and moral choice guided by human volition. |

References

- Agricola, Rodolphus, and Lothar Mundt. 1992. De Inventione Dialectica Libri Tres. Drei Bücher Über Die Inventio Dialectica. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 229–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alardus, Franciscus. 1566. Een cort vervat van alle menschelijcke insettinghen der Roomscher Kercke (re-edition 1580). Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books/about/Een_cort_vervat_van_alle_menschelijcke_i.html?id=jzdKzgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Alardus, Franciscus. 1610. Een cort verhael van alle menschelijcke insettingen der Roommscher Kercke. Dordrecht: Adriaen Jansz, p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, William. 2004. Religious Syncretism: The New Gods of Greek Tragedy. Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 102: 113–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristodemou, Georgia. 2021. Eros Figures in the Iconography of Death. Some Notes on Funerary Monuments from Macedonia during the Roman Period. Eikón Imago 10: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialostocki, Jan. 1988. Puer sufflans ignes. In The Message of Images: Studies in the History of Art. Vienna: Irsa Verlag, pp. 139–44. [Google Scholar]

- Boaistuau, Pierre. 1608. Het wonderlijcke schadt-boeck (…). Antwerp: Ghelyn Janssens, pp. 136–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bober, Phyllis Pray, Ruth Rubinstein, and Susan Woodford. 2010. Renaissance Artists and Antique Sculpture. A Handbook of Sources, 2nd rev. ed. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, Jheronymus. 1913. Adoration of the Magi, c. 1475. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: John Stewart Kennedy Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Costerus, Franciscus. 1616. Sermoonen op de Epistelen van de Sondaghen des gheheelen laers. Antwerp: Hiëronymus Verdussen, p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Daneau, Lambert, and Johannes de Swaef. 1617. Tractaet vanden eerlicken staet der Christenen in hare cleedinghe. Middelburg: Adriaen Vanden Vivere. [Google Scholar]

- Daneau, Lambert, and Johannes Florianus. 1583. Christelycke antvvoorde op den eersten boeck der lasteringhen en vernieude valscheden van twee apostaten Mattheeus de Launoy, priester, ende Hendrick Pennetier. Antwerp: Nicolaes Soolmans. [Google Scholar]

- David (Divoda Iansen van Heylichen-Stadt), Johannes. 1609. Vry-Gheleyde tot ontlastinghe van conscientie om de catholijcke kercken, beelden, ende godtsdienst te gaen bekiicken. Antwerp: Joachim Trognetius. [Google Scholar]

- David, Johannes. 1603. Christeliiken Waerseggher. Antwerp: Officia Plantina, Ian Moerentorf. [Google Scholar]

- David, Johannes. 1607. Bloem-hof der kerckelicker ceremonien. Antwerp: Ioachim Trognesius, pp. 133–35. [Google Scholar]

- David, Johannes. 1611. Postillon van de Roskam der vermomder Eselinne. Antwerp: Joachim Trognetius. [Google Scholar]

- De Launnoy, Matthieu, and Hendrick Pennetier. 1578. Die verclaringhe ende verworpinghe van het valsch verstant ende quaet misbruycken van sommige sententien der heyliger Schriftueren. Antwerp: Hendrick Wouters. [Google Scholar]

- Devisscher, Hans, and Hans Vlieghe. 2014. The Life of Christ before the Passion. The Youth of Christ (Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, V.1). London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- DiFuria, Arthur J., ed. 2016. Genre Imagery in Early Modern Northern Europe. London: Routledge, pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Duerloo, Luc, and Marc Wingens. 2002. Scherpenheuvel: Het Jeruzalem van de Lage Landen. Leuven: Davidsfonds. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Teresa. 2008. Peter Paul Rubens and the Distribution of Secret Knowledge in Antwerp and Italy. Ph.D. dissertation, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Teresa. 2020. Black Ethiopians and the Origin of ‘materia Prima’ in Rubens’ Images of Creation. Oud Holland 133: 10–32. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Gillian R. 1976. St. Anselm’s Images of Trinity. The Journal of Theological Studie, New Series 27: 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, Dan. 2004–2005. Magi and Merchants: The Force Behind the Antwerp Mannerists’ Adoration Pictures. In Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. Antwerp: KMSKA, pp. 275–99. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, David. 1988. Iconoclasm and Painting in the Revolt of the Netherlands. 1566–1609. Outstanding Theses in the Fine Arts from Britisch Universities. New York and London: Garland. [Google Scholar]

- Fucci, Robert. 2019. Rubens and the Twelve Years Truce: Reconsidering the Adoration of the Magi for the Antwerp Town Hall. In Tributes to David Freedberg. Image and Insight. Edited by Claudia Swan. Published in 2019 in the David Freedberg Festschrift. London: Harvey Miller, pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, Carmen, and Jaime García Márquez. 2004. La adoración de los magos de Rubens. Materiales y técnica pictórica. In Rubens: La adoración de los magos/Rubens: The Adoration of the Magi (2004−2005). Edited by A. Vergara. Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, pp. 141–54. [Google Scholar]

- Groenveld, Simon, and Huib van Leeuwenbergh, eds. 2008. De Tachtigjarige oorlog: Opstand en consolidatie in de Nederlanden (ca. 1560–1650). Zutphen: Walburgpers. [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere, Koenraad. 2012. Antwerp Art after Iconoclasm. Experiments in Decorum 1566–1585. Brussels, New Haven and London: Mercatorfonds—Yale University Press, pp. 264–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jonckheere, Koenraad. 2019. Aertsen, Rubens and the questye in early modern painting. Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art/Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 68: 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junius, Franciscus. 1638. The Painting of the Ancients, in Three Books. London: R. Hodgkinsonne, p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Lipisus, Justus. 1604. Diva Virgo Hallensis. Antwerp: Officina Plantiniana, Ioannes Moretus. [Google Scholar]

- Lipisus, Justus. 1605. Diua Sichemiensis, Siue, Aspricollis. Antwerp: Officina Plantiniana, Ioannes Moretus. [Google Scholar]

- Marcaida, José Ramón. 2014. Rubens and the Bird of Paradise. Painting Natural Knowledge in the Early Seventeenth Century. Renaissance Studies 28: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, Alexander. 2021. Rubens’ Spirit: From Ingenuity to Genius. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, Elizabeth. 2018. Black Bodies and Dionysiac Revels: Rubens’ Bacchic Ethiopians. In Rubens and the Human Body. Edited by Cordula van Wyhe. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 291–316. [Google Scholar]

- Molanus, Johannes. 1570. De Pictvris Et Imaginibvs Sacris (…). Leuven: Hieronymum Wellaeum. [Google Scholar]

- Molanus, Johannes. 1996. Traité Des Saintes Images. Edited by François Boespflug, Olivier Christin and Benoît Tassel. 2 vols. Paris: Les Editions du Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Morford, Mark. 1991. Stoics and Neostoics. Rubens and the Circle of Lipsius. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nemerov, Alexander. 2013. The cauldron: Rubens’ “Adoration of the Magi” in Madrid. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 63: 238–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numan, Philips. 1607. Die Heylighe Maghet van Halle. Brussels: Rutger Velpius. [Google Scholar]

- op ‘t Hof, W. J. 2008. Willem Teellinck (1579–1629). Leven, Geschriften en Invloed. Kampen: De Groot Goudriaan. [Google Scholar]

- Paleotti, Gabriele. 1582. Discorso intorno alle imagini sacre et profane diuiso in cinque libri. Bologna. Available online: https://books.google.com.sg/books/about/Discorso_intorno_alle_imagini_sacre_et_p.html?id=BiWvs5txQmAC&redir_esc=y. (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Paleotti, Gabriele. 2012. Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images. Texts & Documents. Edited by William McCuaig and Paolo Prodi. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 1603. Iconologia, overo Descrittione di diverse imagini cauate dall’antichità, & di propria inuentione. Rome: Lepido Faci, pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sleidanus, Johannes. 1558. Waerachtige beschrivinge hoe dattet met de religie gestaen heeft. pp. 326–28. [Google Scholar]

- Snellaert, F. A. 1878. Jean David. In Biographie Nationale de Belgique. Brussel: Royal Academy of Belgium, vol. IV. [Google Scholar]

- Sors, Anne-Katrin. 2015. Allegorische Andachtsbücher in Antwerpen. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen, pp. 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Strengholt, Leendert, ed. 1974. Constantijn Huygens, Heilighe Daghen. Amsterdam: Buijten & Schipperheijn, pp. 46–47. [Google Scholar]

- Syverts, Wallich. 1604. Roomsche Mysterien: Ondeckt in een Cleyn Tractaetgen (…). Amsterdam: Ambrosius Janszoon. [Google Scholar]

- Tauler, Joannes. 1593. Gheestelycke Predication. Translated and Edited by Bartholt Francois. Antwerp: Hieronymus Verdussen, vols. 50v.–58v. [Google Scholar]

- Teellinck, Willem. 1608. Philopatris (…). Middelburg: Adriaen Vanden Vivere. [Google Scholar]

- Teellinck, Willem. 1609. Timotheus, Ofte Ghetrouwe Waerschouwinge. Middelburg: Adriaen Vanden Vivere. [Google Scholar]

- Teellinck, Willem. 1611. Ontdeckinge des vermomden Balaams. Middelburg: Adriaen Vanden Vivere. [Google Scholar]

- Teellinck, Willem. 1624. Gesonde Bitterheyt Vorden Weelderighen Christen. Brandt. Amsterdam: Marten Iansz. [Google Scholar]

- Teellinck, Willem. 1648. Timotheus, Ofte Ghetrouwe Waerschouwinge, 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Françoys Boels. [Google Scholar]

- Vadakkekara, Benedict. 1995. Origin of India’s St. Thomas Christians: A Historiographical Critique. Delhi: Media House. [Google Scholar]

- Vaenius, Otto. 1608. Amorum Emblemata. Antwerp: Hieronymus Verdussen, pp. 190–91. [Google Scholar]

- van den Vondel, Joost. 1647. Poëzy. Tweede deel, Lofdichten op Schilderyen en andre Kunst. pp. 366–67. [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg, Peter, and Carola Vermeeren. 1997. De kunstcollectie van Frederik Hendrik en Amalia (Mauritshuis, The Hague, 1997–1998). The Hague and Zwolle: Waanders. [Google Scholar]

- vander Schuere, Nicasium. 1581. Een cleyne, oft corte Institutie, dat is onderwijsinghe der Christelijker Religie. Ghent: Gaultier Manilius. [Google Scholar]

- van Hattem, Olivier. 1611. Apostille oft eer een antwoorde op seker calomnieuse requeste, ghestelt by eenen onghenoemden ketter aen den paus sijn heyligheyt, teghen D. Oliverium Hattemium. Antwerp: Gheleyn Janssens, pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- van Mander, Karel. 1615. Vvtlegginge. Amsterdam: Dirck Pietersz. [Google Scholar]

- van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, Philips. 1601. Tafereel der religions verschillen, Dutch ed. Amsterdam: Jan Everaertsz. [Google Scholar]

- van Marnix van Sint Aldegonde, Philips. 1611. Byen-korf. Delft: Bruyn Harmansz. [Google Scholar]

- van Oosterwijk, Aalbrecht. 1605. Heylige maghet van Halle. Hare weldaden ende miraculen ghetrouwelick ende ordentlick wtgheschreven. Delft: Bruyn Harmanssz. [Google Scholar]

- van Strien, Ton, and Els Stronks. 1999. Het hart naar boven. Religieuze poëzie uit de zeventiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Ambo—Amsterdam University Press, pp. 143–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, Alejandro. 2004. Rubens: La adoración de los magos/Rubens: The Adoration of the Magi. Madrid and London: Paul Holberton Publishing, pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara, Alejandro, Cabrero Herlinda, and Rubens Peter Paul. 2004. Rubens: The Adoration of the Magi. Madrid and London: Paul Holberton Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Vlieghe, Hans. 1998. Flemish Art and Architecture, 1585–1700. The Pelican History of Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, Mariet. 1998. The Amusements of Jan Steen: Comic Painting in the Seventeenth Century. Studies in Netherlandish Art and Cultural History. Zwolle: W Books, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).