1. Starting Conversations

The first interview I conducted was with my grandmother, Shu-in Lin, who we called Nini. It was 1993 and I was in sixth grade, completing a course assignment by interviewing an older relative. I still have the VHS tape (newish media then) of our interview, in which Nini gleefully describes growing up in Wenzhou, a southeastern Chinese city. She also discusses her fateful move to Taiwan in 1947, coincidentally, two years before the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) takeover of mainland China. My grandparents’ move to Taiwan allowed them to escape ensuing hardships including a massive famine and tumultuous Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Simultaneously, my grandparents became unexpectedly, devastatingly separated from their relatives for half a century. Amidst the CCP’s victory and establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the Nationalist Party fled to Taiwan, creating unrest on the island previously under Japanese colonial rule (1895–1945). Many Taiwanese locals, including indigenous islanders and immigrants from mainland China whose families had settled there long ago, resented the arrival of the Nationalists, along with so many civilians, from mainland China. As Nini explained in our interview, she spent some of her childhood in Xiamen, a mainland Chinese city across the strait from Taiwan, which shared with the island a nearly indistinguishable dialect. Having acquired the dialect, Nini, as the only member of her local community of Wenzhounese transplants who could communicate in Taiwanese, ran everyone’s errands. Others, including my grandfather and father, then just a baby, remained hidden in attics and backrooms, fearing conflicts accompanying the wave of migration. At the time of my sixth-grade interview, I spoke little putong hua (Mandarin Chinese) and no Wenzhounese, the famously indecipherable dialect my grandparents spoke with each other. Nini, who had immigrated to the United States (US) as an adult following my father’s arrival to pursue graduate study in the late 1960s, spoke only basic English. My dad translated our interview and can be heard off-screen. Despite interpretative delays, my interview with Nini was full of smiles and laughter—our appreciation of the chance to share stories shining. Our conversation inspired me to begin studying putong hua so I could better communicate with my grandparents. Language barriers are common among immigrant families, and every family faces generational distances. While we can never wholly pass on lived experiences across generations, such efforts—through interviewing, documenting, reenacting, tracing haunts, learning each other’s languages, or sharing moments of closeness—strengthen our connections while leading to new discoveries.

Over the past several years, I have been exploring how diasporic Chinese artists present familial histories and tales of migration and cross-cultural exchange through video art and cinematic installations for an exhibition I am curating: Another Beautiful Country: Moving Images by Chinese American Artists, scheduled to take place at the University of Southern California (USC) Pacific Asia Museum in 2024. Drawing its title from the Chinese word for America (Meiguo, literally, beautiful country) and the popular abbreviation for American-born Chinese (ABC), Another Beautiful Country foregrounds shifting ideas of nationhood explored by artists who identify, however partially or conflictedly, as do I, as Chinese American. Like me, many of the exhibition’s artists were born in the US, though some were born elsewhere, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Canada, Trinidad, and Tobago. Offering expansive views of cultures and identities, Another Beautiful Country foregrounds moving images (filmic, as well as emotionally evocative and migration-related) by artists confronting subject positions of being both, while perhaps neither enough, Chinese and (nor) American. The featured artworks provide alternatives to official histories of nation formation by exploring how immigrants and their offspring define, critique, and imagine home. I hope visitors will become immersed in the exhibited works and continue contemplating intercultural exchanges. The kind of immersion I endeavor is akin to old-fashioned language immersion, by which people steeped in a foreign language gradually learn to speak with their own accents, cadences, and idiosyncrasies. This type of immersion differs from the flashy experiences promoted in current “new media” exhibitions, whereby visitors feel submerged in artworks (e.g., via all-encompassing video projections, sonic installations, engulfing performances, and/or VR headsets). I seek a more subtle, slower immersion, one which has long been present in museums, in which viewers concentrate before a work of art, closely looking, watching, listening, and feeling. Such concentration invites in artists’ perspectives, in the case of Another Beautiful Country, of being between China and America, enhancing cross-cultural understanding.

This article discusses projects by two of the artists featured in Another Beautiful Country: Richard Fung (b. 1954) and Patty Chang (b. 1972). Both artists utilize video art for intimate portrayals of older family members and/or historical figures. I argue that Fung and Chang’s representations of familial relations and overlooked histories share elder wisdom and multilayered transnational experiences. These artists’ experimental documentaries and performative videos foster deep personal discoveries that defy the late-capitalist obsession with the new defined by youth, novelty, and the next trend, providing revelatory insights through recuperative engagements with what has come before. In discussing artworks by Fung and Chang, I also reference related texts by/about artists and historical figures including German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940); the first Chinese American movie star, Anna May Wong (1905–1961), whose interview with Benjamin inspired an artwork by Patty Chang; and Zhang Ailing/Eileen Chang (1920–1955), who emigrated from the PRC to the US in the 1950s, and whose special collections in the USC Libraries helped inform the exhibition’s programming. I also interweave my own related familial histories and finally share some (not-so-new) curatorial ideas for immersing audiences in cross-cultural art and reflection.

2. Experimental Documentaries by Richard Fung

Born in Port of Spain, Trinidad, and currently based in Toronto, Canada, artist Richard Fung began making video art in the 1980s amidst a striking dearth of representation of Asians and Asian Americans in Western art and popular culture. The artist’s pivotal essay, “Looking for My Penis: The Eroticized Asian in Gay Video Porn” (

Fung 1991), discusses the lack of Asian characters in the context of gay pornography, while scrutinizing widely held beliefs, perpetuated in mainstream media, that Asians constitute the most sexually restrained race. Fung cites a controversial study by psychologist Philippe Rushton which “posits that degree of ‘sexuality’—interpreted as penis and vagina size, frequency of intercourse, buttock and lip size—correlates positively with criminality and sociopathic behavior and inversely with intelligence, health, and longevity” (

Fung 1991, p. 145). The artist writes the following:

Rushton sees race as the determining factor and places East Asians (Rushton uses the word Orientals) on one end of the spectrum and blacks on the other. Since whites fall squarely in the middle, the position of perfect balance, there is no need for analysis, and they remain free of scrutiny. Notwithstanding its profound scientific shortcomings, Rushton’s work serves as an excellent articulation of a dominant discourse on race and sexuality in Western society—a system of ideas and reciprocal practices that originated in Europe simultaneously with (some argue as a conscious justification for) colonial expansion and slavery. In the nineteenth century these ideas took on a scientific gloss with social Darwinism and eugenics. Now they reappear, somewhat altered, in psychology journals from the likes of Rushton. It is important to add that these ideas have also permeated the global popular consciousness. Anyone who has been exposed to Western television or advertising images, which is much of the world, will have absorbed this particular constellation of stereotyping and racial hierarchy. In Trinidad in the 1960s, on the outer reaches of the empire, everyone in my schoolyard was thoroughly versed in these “truths” about the races.

Here, Fung observes how pernicious pseudoscientific studies seep into the collective consciousness, describing the international absorption of racist stereotyping through popular media.

Fung’s notion of absorption is akin to German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s in “The Work of Art in Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (

Benjamin [1935] 1969). Published in 1935 amidst the rise of fascism and on the precipice of World War II, and still highly resonant today, Benjamin’s essay discusses the emergence of reproductive technologies and the corresponding diminishing of the “aura” of the original work of art. Benjamin draws a distinction between (1) art/entertainment, absorbed with apperception, that distracts the masses, and (2) art that absorbs, and in so doing, heightens perception and may enlighten viewers. Architecture and Hollywood movies, Benjamin argues, tend to be absorbed in a state of distraction. In contrast, he cites a Chinese legend in which an artist becomes absorbed by his painting:

Distraction and concentration form polar opposites which may be stated as follows: A man who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it. He enters into this work of art the way legend tells of the Chinese painter when he viewed his finished painting. In contrast, the distracted mass absorbs the work of art.

Benjamin’s reference to art outside Western traditions, and specifically to Chinese painting, to illustrate the principle of being absorbed, exemplifies how people in the West have long looked to Asian practices and philosophies—yoga, meditation, and Buddhism—to heighten perception, attention, and presentness. Technology has developed exponentially since Benjamin wrote “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, and our world is full of absorbing media. Today, contemporary life in the PRC is as, if not more, impacted by distracting media, technological developments, and speed, as is life in the US. As Fung notes, through television and advertising (and to this, we can now add the Internet, social media, video games, apps, and so on), people of all backgrounds around the globe absorb misinformation in states of distraction and apperception, leading to the perpetuation of racist and misogynistic beliefs and actions.

Fung originally presented “Looking for my Penis” at “How Do I Look? Queer Film and Video”, a 1989 conference organized by the editorial group Bad Object-Choices and held at New York’s Anthology Film Archives. The conference aimed to address gay and lesbian media theory, and presenters and audience participants including Fung, Kobena Mercer, and Isaac Julien raised issues of race in addition to sexuality, fostering an intersectional dialogue prior to the coining of the term intersectionality.

1 Bad Object-Choices encouraged participants to transform their presentations into essays for publication but faced difficulty publishing the volume.

2 Douglas Crimp, one of the conference organizers, also planned to publish essay versions of the presentations in a 1990 issue of the art journal,

October, but those essays, including Fung’s, were rejected, and Crimp was ousted from

October’s editorial board, presumably for being too activist- and identity-politics-oriented.

3 Fung’s critique of white supremacist narratives thus extends to the field of art history, as the artist’s writing and videos pose critical challenges to narrow definitions of art, formalist interpretations, and the Western-European-centricity of art historical canon formation.

Since the 1980s, Fung has challenged the lack of Asian representation in gay pornography, film, and art, creating multiple video artworks centering queer Asian as well as diasporic Chinese subjects. Three of Fung’s experimental documentaries focus on older relatives: his father in The Way to My Father’s Village (38 min, 1988), the artist’s mother in My Mother’s Place (49 min, 1990), and his cousin who was ninety years old at the time of Fung’s filming of Nang by Nang (40 min, 2018). These single-channel videos utilize documentary film methods, while subverting any pretense of detached, objective reporting by, for example, the artist appearing in front of the camera or letting his voice be heard out of frame. The videos tell personal histories and share quiet moments of reflection that resist nationalist bombast.

The Way to My Father’s Village (

Figure 1) opens with shaky footage centered on a stone road, followed by a man’s voice answering questions, presumably posed by an immigration officer played by a woman who types his (Fung’s father’s) responses:

Name: Eugene Arthur Fung; Occupation: Businessman; Marital Status: Married; Place and Date of Birth: China, 1 August 1909. A gong and traditional Chinese music sounds and

1279 A.D. appears. The narrator states the following:

700 years ago, the Mongols invaded northern China. Many of the original Chinese inhabitants fled south. The Hakka, as these people came to be known, lived apart from the other Han Chinese on the porous land, all that was available. Today in Kwangtung/Canton, the Hakka maintain their own villages, their own customs, their own language. The word Hakka means guest family.

Computer graphics of traditional Chinese art, footage of natural landscapes (including, presumably, those of Fung’s father’s home village), and hands flipping through a Great World Atlas accompany this historical overview. The narration then shifts, describing the microhistory of Fung’s father: his birth in a little Hakka village to an apothecary and farmer and first migration from a small village in southern China’s Guangdong Province to Trinidad via Hong Kong and Canada; marriage; establishment of a prosperous business; eight children; a second migration in 1976 to Toronto, Canada; and death, following his second stroke, in 1986. Varied footage of landscapes, modes of transport, photographs, and government documents fade in and out, before blank screens with

HISTORY, and then

HISTORY and memory appear.

The Way to My Father’s Village questions HISTORY (in all capitals, or grand historical narratives), as well as individual memories, privileging the latter, albeit with ambivalence. The video then switches to first-person narration with Fung describing his own life experiences and relationship with and memories of his father as he looks through old family photographs and his father’s papers and passports, which, he notes, do not reveal much: “These government documents are all my father left behind, but I find it hard to see my father’s ghost in these statistics” (

Fung 1988). Throughout the video, Fung contrasts his own interest in Chinese culture with his dad’s seeming disinterest and repression as he assimilated as a converted Catholic in Trinidad:

Dad never returned to China in the almost sixty years since he left his village and he never wanted us to. Though he talked a lot about being Chinese, he was proud of his Catholicism and his ability to use a knife and fork. He never taught us his language. There’s a real finality in that. So learning about China was almost an act of rebellion, an invasion of privacy…The past my father tried to escape becomes for me a means of self-definition.

Fung then interviews his cousins, Tony and Dorothy, whose father was the artist’s dad’s older brother. Tony and Dorothy recall their early childhood in Jamaica, being sent back to Hong Kong to study in Jesuit schools, and harrowing escapes from China in the 1930s during the Sino–Japanese War. The video also chronicles the artist’s first trip to China, in 1986, and to his father’s village, which his aunt discouraged him from visiting, saying “There’s nothing to see there” (

Fung 1988). An air of disappointment surrounds Fung’s descriptions of the trip. He describes feeling like a perpetual outsider and having difficulties communicating (his English had to be translated into Cantonese by his mother, which was then translated into Hakka by his aunt). He struggles to imagine the scenes relayed to him by his father and cousins and does not find much. Resignedly, Fung states, “Memory of the real and memory of the imagined become indistinguishable” (

Fung 1988). His camera fixates on the face of an elderly woman. She shares his last name, and he says with uncertainty that she is the oldest Fung in the village. The footage and narration of Fung’s trip to China are interwoven with texts about China by foreigners, including, as labeled,

Marco Polo/explorer, trader. Venice 1298 A.D., speaking about bustling markets, and

Matteo Ricci/missionary, diplomat. Macerata 1552–1610, commenting on the “abomination” of eunuchs and “public streets of boys cut up like prostitutes” (

Fung 1988). Fung’s accounts of his travels both relate to and depart from these legendary, moralistic, and imperialistic tales. Recognizing his outsider status, Fung strives to learn more about his Chinese roots, ruminating on cross-cultural legacies. Revealing the multilayered identities of his father, cousins, and himself, informed by multiple migrations and fluctuating perceptions, Fung’s

The Way to My Father’s Village crystallizes diasporic subjects’ inability to fully identify with a single nationality. Simultaneously, the video illuminates varied ways emigres and their children regard home and reminds us of how much can be sought on a journey.

While

The Way to My Father’s Village was created after the death of Fung’s father, offering a lament on distance in life and in death,

My Mother’s Place (

Figure 2) centers on recorded interviews and conversations in Canada and Trinidad between the artist and his mother, Rita, uplifting her presence and survival amidst hardship. The video integrates theoretical musings on feminism, identity politics, and the legacies of colonialism, opening with four friends of the artist—female intellectuals, activists, and artists—discussing the importance of representation. Following the heading “Reading Instructions”, Indian Canadian sociologist and philosopher Himani Banerji describes how she sees her task as an author of color: “Just to write about how we live with each other…what goes on… without even remembering there is a white audience…I have to ask myself, ‘Who is this for?’… I think what is necessary is to remember what we know ourselves” (

Fung 1990). As Indo-Trinidadian writer Ramabai Espinet states, “One of the major tasks is to facilitate the emergence of women as doers, as producers of their own culture…Another task is really raising the awareness of men…in the society about the problem of violence against women and children…Violence is a fact of life in the Caribbean…it’s part of the legacy from slavery and indentureship” (

Fung 1990). British-born Canadian ethnographer Dorothy Smith recalls how areas in the Caribbean were first presented to her in an atlas with pink areas that were

ours, the British Empire, and the need to consider how colonialism and power relations are circulated and perpetuated amongst ordinary people through flattened texts and modes of representation with “the absence of dimension, the absence of others, the absence of speaking back” (

Fung 1990). Black Canadian filmmaker Glace Lawrence adds, “I would like to just see more images, more faces because I think if people don’t see you, it’s almost as if you don’t exist…and you don’t experience these things and you don’t feel these things. So that’s why I want to make films… I want to make sure that the experiences and…the history has been documented visually” (

Fung 1990).

The video then focuses on Rita and her life stories, as Fung brings theory into artistic action, foregrounding a very personal story of his mother. We see Rita and her relative visiting family members’ graves in Princes Town Cemetery and footage from her childhood village in Moruga in southern Trinidad, a place, Fung notes, that he thought he had visited as a child but realized he just imagined based on his mother’s stories. We see Rita speaking about her family, childhood, education reflective of colonialism (she recalls having to learn the names of British cities), a grandfatherly family friend smoking opium, carnival, race, and class relations in colonial Trinidad and Tobago. She speaks sitting in front of a window in her Canadian home or on a bed with a mirror behind her, in which we see the artist’s reflection. At other times, Rita’s narration is paired with footage of Trinidadian flora, fauna, and people celebrating on the streets during carnival, with the colors of feathers and fabric of costumes graphically enhanced. Throughout the video, Fung contrasts Canada’s suburban landscape (snowy, tree-filled, and lowly populated) with that of Trinidad (wet, warm, lush, and filled with people). Fung also integrates family photographs and home movie footage showing him dancing with the title

One day Mom caught me in one of her dresses and threatened to put me out in the street…I was scared but it didn’t stop me. Fung recalls memories, positive and negative, and considers how home videos reflect the family’s aspirations more than realities. Rita describes her fraught relationship with her father. Despite living in Trinidad for decades, her father maintained that his children, especially his son in China, were far superior to his children born in Trinidad. He insisted Rita and her siblings only befriend children of Chinese descent, but they secretly made friends of all races and backgrounds.

My Mother’s Place speaks to the conflicts but also the importance of familial relations: “When I look at her [my mother]…I know who I am” (

Fung 1990). The artist concludes by describing a disagreement he had with his mom over whether an oak tree in her backyard should be cut down. The artist felt it should stay, but his mother, who had grown up on the edge of a forest and did not find trees romantic, felt it hampered her tomatoes. When the artist returned to Canada, the tree had been cut and beautiful tomatoes abounded. The final shot of

My Mother’s Place shows tomatoes dropped into a salad bowl, with overlaid text:

I once read an article by Dorothy Smith in which she said that the answers the subject gives are much less notable than the questions the sociologist asks.

Fung sees his most recent experimental documentary,

Nang by Nang (

Figure 3), as a continuation of his autoethnographic explorations into members of his Chinese Caribbean family. Fung met his first cousin, Nang, known by many names throughout her life (e.g., Anang, Dorothy, and Mavis) for the first time when he began making the video. He films Nang in her Rio Rancho, New Mexico home and later, the cousins travel together to their hometown in Trinidad. Throughout the video, Nang speaks about her past experiences: growing up as a mixed-race illegitimate child; being raised by her grandparents; various moves around the world including from Trinidad to Venezuela and later to the US; her illustrious dancing career; and several relationships, some abusive, some loving, including five marriages. Out of each of the three videos focusing on the artist’s family members,

Nang by Nang features Fung most prominently. He is often seen on camera, as is his partner, Tim, who Fung notes he brings along as his assistant. After their initial meeting, Fung invites Nang to travel with him to Port of Spain, where both cousins grew up. The trip feels joyous and fruitful as Nang visits old haunts and meets friends she has not seen in years. Fung narrates and asks Nang questions throughout

Nang by Nang, and toward the conclusion, he shares that Nang now calls him regularly to remind him and Tim to take their daily vitamins. Small acts of care abound in

Nang by Nang, and viewers sense this project formed a new, treasured relationship between the artist and his elder cousin.

Upon first watching Nang by Nang, I immediately thought of my grandmother, Nini. I wrote to Fung the following: Your cousin was such a radiant person and you illuminate her beauty, warmth, and electrifying energy, as well as that of the varied landscapes she inhabited. She reminds me of my grandmother, who passed away a couple years ago at 97. Nini was born in Wenzhou, then moved to Taiwan and later to the US. Both women shared a wonderful combination of elegance and edginess, and, even amidst past hardships, exuded joy.

3. Intimate Relations in Patty Chang’s Performative Videos

San Francisco Bay Area-born, Los Angeles-based, Chinese American artist Patty Chang became well known in the 1990s for her bold performances and video artworks addressing love, family, death, and bodily functions. Chang frequently twists conventions of feminine beauty and defies stereotypes of Asian women as passive subjects. In her 1998 performance video,

Melons (At a Loss) (

Figure 4), Chang stares into the camera and tells stories related to a commemorative plate, bearing a photo of her smiling aunt, which she received following her aunt’s death:

When my aunt died, I got a plate. It was the kind of plate with a color photo printed on it in a poisonous ink that you couldn’t eat or else you’d die too. The original, which was made in a fine porcelain, was made back when my aunt and uncle got married, back in the days when black and white meant photos and color meant paint. When she died, extras were ordered from Thrifty’s photo department. $10.99 for saucer, $29.99 for dinner. I was given a saucer and told it was because I was smaller and more petite than everyone else, not because it was cheaper.

While talking, Chang balances a plate atop her head and slices through her bra with a large kitchen knife to reveal a melon, which she then seeds, scoops, and eats, placing excess stringy melon and seeds atop the plate. In a tone that is simultaneously authoritative, straightforward, and droll, Chang continues speaking about the plate and the irreverent ways she used it: “Whenever I was punished for doing something I wasn’t supposed to do, I would take that plate off of its redwood display stand. And lick that puppy until her smile was erased”, she finishes, removing the plate from her head and smashing it on the ground (

Chang 1998).

In other works, Chang enacts intergenerational intimacies, as in

In Love (2001), a video portraying the artist in kissing-like contact with her parents. The two-channel video shows the artist eating a raw onion, shared between mouths, with her father in one video and her mother in the other. Played in reverse, the onion seems to emerge whole from their mouths, and tears stream up their faces and into closed eyes. Chang’s more recent video art installation,

The Wandering Lake (2009–2017) (

Figure 5), departs from Swedish explorer Sven Hedin’s 1938 book of the same title chronicling his travels to a migrating body of water in the western Chinese desert region of Xinjiang.

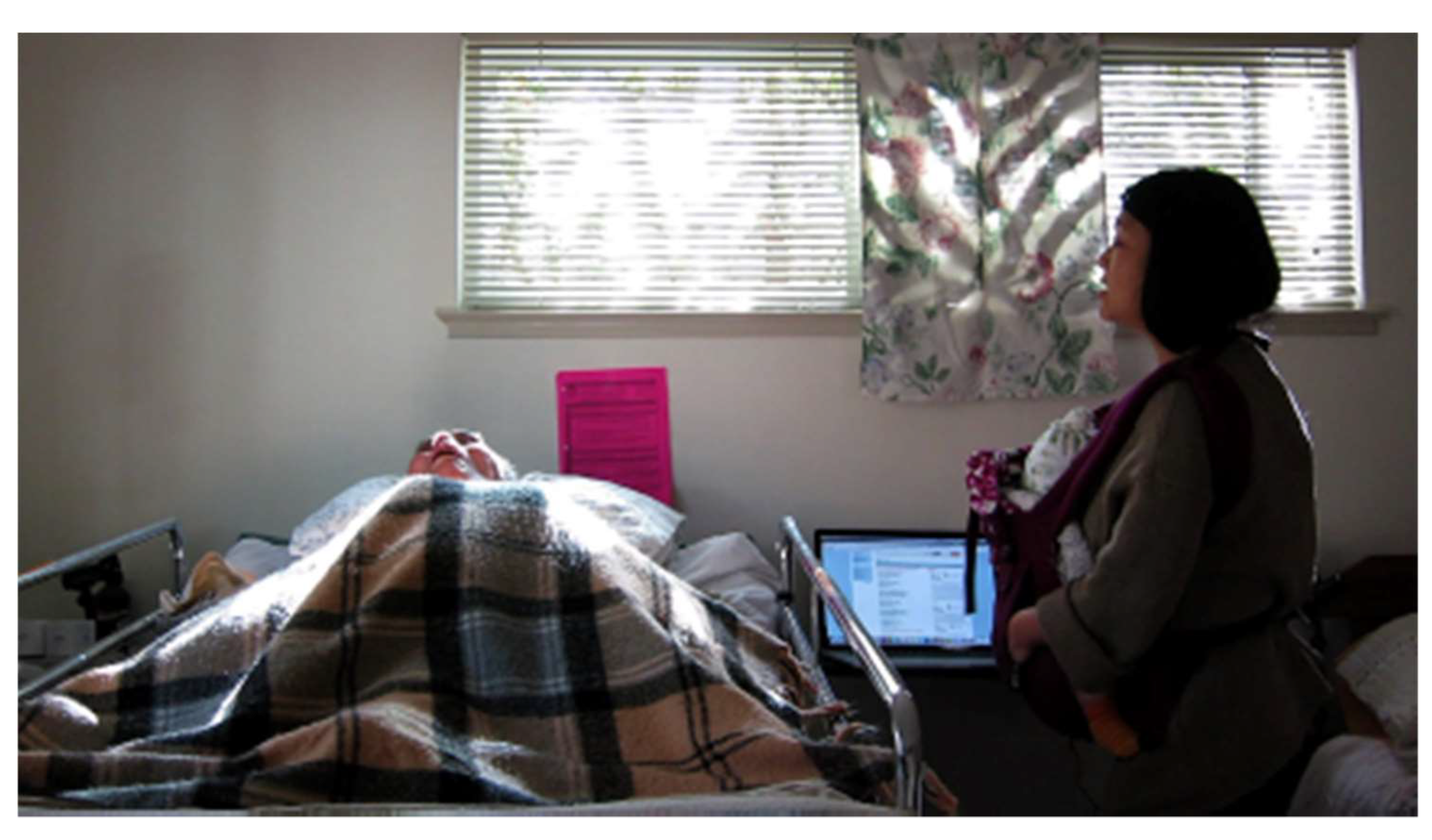

The Wandering Lake includes documents of Chang’s own research on and travels throughout the region. The installation integrates footage of the artist urinating through funnel devices into bottles (and delicate glass reconstructions of those bottles); washing a deceased beached whale; and conversing with members of the Uighur minority group. In one video segment, Chang appears singing to and rocking her newborn baby beside her dying father, who lies nearly motionless on a bed—a tender reminder of life’s cruel and beautiful cycles.

Further exploring Chinese American cultural heritage, gender identities, Asian-European exchange, difficulties of translation, and troubling cinematic histories, Chang’s 42- minute two-channel video installation

The Product Love—

Die Ware Liebe (2009) (

Figure 6) responds to Walter Benjamin’s interview of Chinese American actress Anna May Wong.

4 Published in 1928 in

Die Literarische Welt (

The Literary World), Benjamin’s relatively little-known piece, “Gespräch mit Anne May Wong: Eine Chinoiserie aus dem Alten Westen” (“Interview with Anna May Wong: A Chinoiserie Out of the Old West”) discusses his encounter with and impressions of Wong in Orientalizing and infantilizing language (

Benjamin 1928, p. 213). Chang’s

The Product Love responds to Benjamin’s exoticizing language and to racism in interwar cultural industries, especially Hollywood, where Wong worked.

The Product Love’s first video alternates between three translators struggling to articulate Benjamin’s text in English, highlighting a particular passage each translator reads differently: in response to Benjamin’s question of how Wong would express herself if she were not an actress, Wong replies “Touch would” (written in English in the otherwise German-language article), after which everyone at the meeting knocks on the table. One translator reads Benjamin’s “Touch would” as incorrect, hypothesizing Wong meant “Touch wood” and that the knocking enacts the superstition of “knocking on wood” (i.e.,

let’s hope Wong never has to stop acting) (

Chang 2009). Another translator thinks “Touch would” means Wong would express herself through touch if she were not acting, and that knocking on the table assimilates a German means of expressing satisfaction, like applause, following a performance (

Chang 2009). Latching onto these varied interpretations springing from the English cognates “would” and “wood”, Chang plays with the sexual implications of “Touch wood” coinciding with Benjamin’s apparent desire for Wong (

Chang 2009).

The second video depicts an all-Chinese cast and crew preparing for and shooting a soft-core pornography film starring actors playing Wong and Benjamin. The video begins with the actors getting made up. Reversing the old cinematic practice of Yellow-face (once ubiquitous, like Black-face) and Hollywood’s correlating anti-miscegenation codes aligned with state and federal laws, make-up artists attend to the Chinese male actor playing Benjamin, applying a thick mustache, wig, and cosmetics while referencing a famous portrait, in which the author appears deep in thought, on the cover of

Reflections. The film’s director, who speaks mostly in

putong hua, shifts to English when he describes Benjamin’s feelings for Wong: “He just wants to touch the G-spot of May Wong. And just like culture, he wants to touch the very sensitive place” (

Chang 2009). The film unfolds awkwardly as the two actors, stilted, proceed to have sex, Benjamin atop Wong. Brief moments of enjoyment appear, but illusions break quickly as a director enters the frame. Benjamin and Wong appear post-coitus, and Benjamin fans their naked bodies and then turns his backside to the camera in a shot resembling classical reclining nude portraits. Yet unlike so many Orientalist, patriarchal versions of reclining nudes in Western European art history, Chang foregrounds the white (disguised Chinese) male nude.

The Product Love reveals how exoticization informs both sexual desire and the desire to grasp a foreign culture.

A passage in Benjamin’s interview reads: “May Wong turns question-and-answer into a swing set: she lays herself back and flies up, plunges down, flies up, and it seems as though from time to time I give her a push. She laughs, that’s it” (

Benjamin 1928, p. 213). Benjamin pairs this paternalistic language with Orientalizing references, opening with “May Wong—the name sounds colorfully embroidered, powerful and light as the diminutive chopsticks that constitute it, which unfurl into odorless blossoms like full moons in a bowl of tea” (

Benjamin 1928, p. 213). Throughout the text, Benjamin seeks to spotlight Wong’s youth and Chineseness, fantasized through flowery language. Yet other descriptions reveal the impossibility of reducing Wong’s identity. Following the “Touch would” passage, Benjamin writes of Wong’s dress:

Her dress would not be at all out of place in such playground games: dark blue coat and skirt, light blue blouse with yellow cravat over—it makes you wish you knew a line of Chinese poetry about it. She has always worn this outfit, for she was born not in China but in Chinatown, in Los Angeles. When her roles call for it, though, she readily dons old national attire. Her imagination works more freely in it.

These observations on Wong’s fashion show the difficulty of categorizing the actress using any fixed notion of identity. Despite Benjamin’s repeated references to Wong’s Chineseness

, as well as to her child-like qualities, the interview demonstrates the actress’s agency in transcending such categories. Benjamin reports Wong’s frustration with being typecast as an immature party girl. “I don’t want to play flappers forever”, she says, “I prefer mothers. Once already at fifteen, I played a mother. Why not? There are so many young mothers” (

Benjamin 1928, p. 213). In life, Wong persisted at the intersection of multiple, uncontainable identities: woman, Chinese, American.

In Chang’s video, Wong dons a yellow silk qipao (Chinese dress, also referred to by its Cantonese name, cheongsam), more akin to Benjamin’s fantasy of her than what she would have worn to their meeting in Berlin. Embracing gender-defying garments, Wong’s favorite item of clothing, as described by Benjamin, was a jacket cut from her father’s traditional Chinese wedding coat. Indeed, Wong became internationally known for her acting as well as her sartorial sensibility that distinctly combined Chinese and Euro-American fashions. Born to second-generation Chinese American parents near Chinatown in Los Angeles, Wong’s humble roots as the daughter of launderers exist far from the glamor she would come to inhabit as Hollywood’s, and the world’s, first Asian American film star. Yet, Wong’s rise—from the child of those who washed others’ clothes for a living to a star decked out in cutting-edge cross-cultural fashions—exemplifies the American and Hollywood dreams with their attendant promises and paradoxes. Wong’s transformation signals a success story tied to the fashionable multicultural diversity of Los Angeles in the interwar period. Simultaneously, her life and career reveal the exclusionary racism underlying both the American dream and Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age. Wong achieved worldwide recognition through her performances, but as scholars have noted, she was frequently typecast in Orientalist and sexist roles, often playing the stereotypical “China Doll” (demure ingénue) or “Dragon Lady” (bewitching femme fatale), and seldom received starring parts.

5 Wong’s career hurdles coincided with the rise and aftermath of the US federal Chinese Exclusion Act (passed in 1882 and not repealed until 1943); deep-rooted local anti-Chinese sentiment (in 1879, 98% of voters in Los Angeles County voted against Chinese immigration); and California’s anti-miscegenation law prohibiting interracial marriage (passed in 1872 and not repealed until 1948).

6 The anti-miscegenation law posed a major obstacle for Wong, as Hollywood’s codes forbade interracial couples from coupling on screen. In 1928, Wong, fed up, sojourned in Europe, where she played leading, sexually liberated roles, breaking free from Hollywood’s stereotypes and her family’s Confucian values. In 1936, she traveled for the first time to Shanghai, China, emerging as one of the most cosmopolitan figures of her time.

Born fifteen years after Wong, theorist, illustrator, and author Zhang Ailing took a quasi-reverse route from the actress. Zhang emigrated from Shanghai to Los Angeles via stays in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and New England, and transitioned from the well-off daughter of an elite Chinese family to a writer who struggled to rent various small, bug-ridden apartments in Hollywood. While historically dismissed within mainland China for being less overtly political than her contemporaries, Zhang’s stories tackle turbulent sociopolitical conditions—colonial occupation, oppressive patriarchy, and the war-torn cityscapes of Shanghai and Hong Kong—through intimate narratives of love, lust, and familial distress, often set in stifling domestic interiors.

In her illustrated essay, “Chinese Life and Fashions”, Zhang reflects on fashion’s cross-cultural and sociopolitical implications, posing a nuanced theory of Chinese modernity (

Zhang [1943] 1987). Throughout her writings, Zhang defines Chinese modernity as being in fashion, which in her birthplace of Shanghai, meant hybridizing imperial traditions, foreign references, and cosmopolitanism, represented in the cross-cultural spaces her female protagonists inhabit, jewels they adorn, and qipaos they wear. “Chinese Life and Fashions” appeared at the height of World War II, in a 1943 issue of

The XXth Century, an English language journal published in Shanghai. Sympathetic to the Axis powers,

The XXth Century primarily features articles about battles and warfare technologies by Japanese, German, and Italian generals. Zhang’s article on Chinese fashion, as well as her film review in a later issue, appear as relative anomalies. Within the context of a propagandistic journal, Zhang powerfully illustrates how fashion and film illuminate shifting societal perspectives, and, in some cases, critically recall past conditions. Zhang also considers clothing’s ability to offer respite from societal turmoil:

Come and see the Chinese family on the day when the clothes handed down for generations are given their annual sunning! The dust that has settled over the strife and strain of lives lived long ago is shaken out and set dancing in the yellow sun. If ever memory has a smell, it is the scent of camphor, sweet and cosy like remembered happiness, sweet and forlorn like forgotten sorrow. You walk down the path between the bamboo poles, flanked on each side by the walls of gorgeous silks and satins, an excavated corridor in a long-buried house of fashion. You press your forehead against the gold embroideries, sun-warmed a moment ago but now cold. The sun has gone down on that slow, smooth, gold-embroidered world.

Fashion, like art, can foster intercultural and intergenerational relationships, linking past and present with an appreciation for the passing of time.

In 2020, I organized, together with my colleague, USC Chinese Studies Librarian Tang Li, and a group of student curators, a virtual exhibition showcasing materials from Zhang Ailing’s special collections housed in the USC Libraries, as well as related materials drawn from the Hong Kong University Library and USC Pacific Asia Museum.

7 The exhibition,

In a Bronze Mirror: Eileen Chang’s Life and Literature, utilizes the open-source platform, Scalar. Organized around Zhang’s life and writings, the exhibition contains a section entitled “Chinese Life and Fashions”, which links to Zhang’s essay of the same title, photographs of the writer and her relatives in qipaos and other fashionable garments, as well as images of silk qipaos housed in the USC Pacific Asia Museum’s collection. Qipaos are traditionally custom-made by a tailor, who precisely fits the garment to a woman’s body. Tailored qipaos are very personal objects, but, like so much art and film, come to be through an intricate web of external craftsmanship, economic exchanges, varied designs, and personal relationships. Countless qipaos have traveled across nations and generations and their continued alteration, reproduction, and occasional integration into artworks or exhibitions, connect us to our foremothers, who dreamed of another beautiful country, one based not on greed and nationalism, but on cross-cultural sharing and neighborly kindness.

4. Intercultural Connections and Immersing Audiences

As I discovered in that first interview with my grandmother, because she could speak the local dialect, Nini often shopped for her neighbors in Taiwan upon immigrating there. Even after the masses of people who fled to Taiwan from mainland China came to dominate the island, gaining greater consumer power and freedom to circulate, Nini, who loved fashion and bargaining, continued shopping with friends. Decades later, I would hear another story of Nini taking her younger neighbor friend, like a daughter to her, to shop. The neighbor, engaged to be married, hoped to purchase one or two colorful wedding dresses, including a qipao. Nini brought the bride-to-be to her favorite market in Taipei. Together they selected silk fabrics—one red, one green. Nini’s trusted tailor came to my grandparent’s house to take the young woman’s measurements and craft two dresses, an elegant red gown and a qipao made of green silk. At her wedding banquet, the woman wore a rented white, Western-style wedding dress, and later changed (as is the custom in Chinese weddings) into the red gown and finally the green qipao. The bride would later give birth to a daughter, who would grow up to become an artist—Patty Chang—a coincidence I would not discover until years following my first encounter with The Product Love in a small artist-run space in Beijing and after Chang and I became colleagues in Los Angeles. A couple of years ago, after Nini passed away, Chang’s mother called my dad and shared the story of those wedding qipaos. She remembered the experience fondly—the time Nini took her to shop with her, the care she showed in helping her obtain quality silk, the introduction to her tailor, and the opening of her home for fittings. Patty Chang recently told me the red and green qipaos still hang in her mother’s closet in the Bay Area, recalling how she used to play dress up in them as a child.

One of my main goals as the curator of the exhibition, Another Beautiful Country, is to present intergenerational cross-cultural connections while particularizing Chinese American experiences. Like qipaos, the exhibition’s artworks share stories, cultural critiques, and points of view that allow audiences to see beyond grand historical narratives, stereotypes, and myths, such as that of the model minority, and restrictive labels (e.g., the US as equaling American; the PRC as equaling Chinese). Foregrounding artistic representations of intimate transnational experiences and relations, the exhibition seeks to inspire viewers’ reflections on their own heretofore marginalized histories.

As many of the artworks in Another Beautiful Country are lengthy single-channel videos, they will be shown on monitors in comfortable surroundings, allowing viewers to watch the videos in full. These relatively old modes of display have proven, at least in my experience, to generate new and enduring ideas. I have often found myself alone in the Pacific Asia Museum, and appreciate the solitude afforded by a relatively small university museum. While the impact of museums today is typically measured by the sheer numbers of attendees, popular blockbuster exhibitions, and immersive experiences that are selfie and social-media-post-worthy, I prioritize quality experiences marked by an artwork’s ability to absorb and the lasting impact of that absorption.

The exhibition will be accompanied by related programming that encourages engagement with diverse histories of immigration, intercultural experiences, and Asian American identities in a localized context. In addition to public conversations with participating artists, I am organizing an event hosted by the museum together with the USC Libraries: Visualizing Asian American L.A.: A Workshop on Digitally Exhibiting Art and Archival Materials. This workshop will encourage participants to bring together materials from their own personal archives and the USC Libraries Special Collections, which include historic photographs of Lunar New Year celebrations and other events in Los Angeles’s old and new Chinatowns dating back to the 1920s; documentation of murals and public art projects representing Asian American histories across the city; and as previously mentioned, Zhang Ailing’s papers, photographs, and ephemera. Together with artists and the USC faculty and librarians, participants will select, present, and discuss images and documents for inclusion in a virtual exhibition, free and accessible to the public via Scalar, like our exhibition featuring materials from Zhang Ailing’s special collections. I hope Another Beautiful Country and our virtual exhibition will offer immersive experiences illuminating generations past while sparking new ways of seeing cross-cultural relations that have long surrounded and sustained us. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted how globally interconnected we have become, while further fraying tense international relations and stoking “us vs. them” mentalities, especially amongst the world’s primary superpowers. Amidst rising geopolitical tensions between the US and PRC, as well as ubiquitous distractions wrought by new media, we have much to glean from concentrating on artworks, anecdotes, and archival materials that resist spectacular effects and grand nationalist narratives with slow-paced, carefully crafted considerations of cross-cultural relations and intimate histories.