1. Introduction

Forceful or voluntary migration and displacement re-evaluate the idea and aesthetics of home through a placemaking narrative that critiques notions of site, agency, and memory. Photography, as used by Cambodian artist Lim Sokchanlina (b.1987) in his

National Road Number 5 series (2015–2020) and Indonesian artist Yoppy Pieter (b.1984) in the

Saujana Sumpu series (2013–2015), instigates an alternative interpretation of placemaking whose meaning transcends geopolitical boundaries. The artworks emphasise the blurred borders between the Southeast Asian nations by communicating perspectives of the universality of the concept of home. While the subject of photography of both artists remains that of home, Sokchanlina’s series facilitates a conversation about geographical displacement through traumatic photographic testimony. In contrast, Pieter’s series conveys loss that becomes a condition to maintain the Sumpu community located in Sumatra, Indonesia. Collective concerns in Cambodia and Indonesia have made apparent the need to metaphorically expand borderlands and address these local conditions of migration through regional and national discourses.

1Migration literature and diaspora scholarship comprise typologies based on causes of mobility and the intentions of those moving.

2 The migrant experience is replete with marginalisation and the erasure of knowledge and history.

3 The inequalities experienced with “belonging” to a specific place create representative classes amongst migrants, as suggested by Edward Said’s “other” and Gayatri Chakravorthy Spivak’s “subaltern”. However, this article does not intend to engage with the politics of migration but instead it maps the effect of migration on the aesthetics of home through photographic documentation of cross-regional communities. The artistic tendencies of Sokchanlina and Pieter methodologically construe linkages between art, mobility, place, and identity.

Sokchanlina and Pieter portray a fraught relationship between place and identity, integrating nuances of belonging integral to a residence and connecting the medium of photography with the notion of a home. Placemaking is a process through which the transformation and development of spaces make them valuable to people. Moreover, placemaking becomes an experience highlighting the relationship between human beings and geographies.

4 Contemporary urban restructuring in Southeast Asia has caused the relocation or displacement of people, melding together geographical, cultural, and temporal processes. The interaction between people and spaces, the configuration of values and identities, and the manifestation of personal and collective memory consolidate the idea of placemaking with the aesthetics of home. The practice creates a robust framework for an interdisciplinary study of place as an attachment of people to their landscape.

The artists’ photographic narration of the effects of migration in Cambodia and Indonesia draws upon the relevance of personal and communal history as related to locale. This article strives to address three queries. One, the conceptual strategies used by the artists in their photographic practice to augment the perception of a dwelling for those forced or voluntarily abandoning their homes. Two, the notion of placemaking through photography generating embodied experiences for migrants, contextually producing memories of home. And three, photographic aesthetics that create agency, enabling the site of a home to be meaningful to the migrants.

This article broadly defines critical concepts of placemaking and home concerning migration and the linkages between Southeast Asian countries and photography. The subsequent section discusses the idea of Southeast Asia, followed by a brief description of the artworks.

5 The explanation of home and placemaking concepts allows for a critical and comparative analysis of Sokchanlina’s

National Road Number 5 and Pieter’s

Saujana Sumpu series, after which the article concludes.

2. Southeast Asian Connections

Nations in Southeast Asia, despite their geographical proximity and colonial legacies (Thailand was the only country in the region that evaded Western colonialism), do not formally share cultural, sociopolitical, and economic histories. Nevertheless, scholarship proves these very connections in Southeast Asian art exist.

6 The creation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations or ASEAN in 1967 to bolster economic growth and regional stability additionally enhanced connectivity transcending political and geographical boundaries. According to Amitav Acharya, a scholar of international relations, “Regionalism […] implies the deliberate act of forging a common platform […] to deal with common challenges, realise common objectives, and articulate and advance a common identity.” (

Acharya 2010, p. 1002). He also argues that the establishment of ASEAN insinuated a precedent for regionalism in Asia, as the Asian identity was a reaction to colonialism and Western bias. ASEAN promotes, fosters, and advances the Southeast Asian perspective globally. Southeast Asia has developed ideas of individual nationalisms while bolstering the “imagined” (as expounded by Benedict Anderson) regional community.

According to sociologists who have studied the region, Southeast Asia’s sociocultural features were aligned before giving way to the increasing diversity seen today (See

King 2008). Parallels drawn between linguistic and religious connections only emphasise the regional capacity to assimilate and conform to the long and sustained interaction of various external forces in Southeast Asia. While the Southeast Asian identity cannot be isolated from Chinese and Indian cultural influences, Western hegemonic structures that dictated the art market until the 2000s have argued otherwise. Western biases have propelled notions that Southeast Asians do not possess an identity independent from South or East Asia or its colonial past (

Taylor 2011, p. 8). Contemporary historians continue to address the relevance of regional art by separating the Southeast Asian narrative and creating one distinct from that provided by the West.

Art creates a platform enabling a comparative model that underscores connections within Southeast Asia and the links it has established with the world. Using concepts of placemaking and home, Sokchanlina and Pieter’s photography traces the contemporary network of cultural interactions in Southeast Asia’s geographies, histories, and environments. Their art becomes “simultaneously Asian and of the world”, emerging from the specific Southeast Asian sociopolitical migration condition.

7 The artworks place Southeast Asia within a global context by examining circumstances leading to the physical relocation of a population due to economic pressure. Migration is not always an isolated event, and aspects of a home that “make place” appeal to those migrants returning. This position of home, as a placemaker, is portrayed in the artworks

National Road Number 5 and

Saujana Sumpu. 3. Artworks

3.1. National Road Number 5

Sokchanlina’s

National Road Number 5 is a series of photographs from 2015–2020, documenting private residences along national highway 5 connecting Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, to the Thailand border (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In early 2015, the Cambodian Ministry of Public Works and Transport received a loan from Japan through the Japan International Cooperation Agency—JICA—to expand the two-lane road into a four-lane one (

Hong n.d.). The consequence of facilitating considerable economic growth and enhancing trade and tourism involved demolishing the private houses built along national highway 5. Sokchanlina’s photographs document the agrarian landscape and the advancing highway construction and record the houses in various stages of demolition.

Sokchanlina references how the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) has used economic corridors—an infrastructural network in a particular geographical area—to bolster the economy. Since 1998, this has linked different countries, expedited conveyance between manufacturers and consumers, and advanced cooperation between local and central governments and public and private sectors. The Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) connects Cambodia with Thailand (Bangkok), Vietnam (Ho Chi Minh City), and Laos.

8 Economic development-induced migration resulting from the construction of the highway connecting the SEC region generates sociocultural turmoil for those forcefully displaced.

9 In most cases worldwide, large-scale development has conclusively proved to be primarily beneficial to the elite, while discriminating against the marginalised.

3.2. Saujana Sumpu

Pieter’s

Saujana Sumpu is a project from 2013–2015 (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Sumpu is a village where an ethnic matrilineal community of Minangkabau people live on the island of West Sumatra, Indonesia (

Sankari 2016). The title of the series of works,

Saujana (as far as eyes can see), indicates both the medium of photography and the medium being a clairvoyant practice.

10 Due to rural migration, the community has steadily declined, and Pieter records the remnants of Sumpu, the notion of home left behind by the process of

merantau or migration. Traditionally, as women inherit property and wealth, the men are morally responsible for building a prosperous society, resulting in migration to gain the skillset required. The concept of

merantau within the Minangkabau becomes a rite of passage for young men to gain wealth, experience, and knowledge outside the village and be independent (See

Pardi et al. 2022). While both men and women have migrated from Sumpu to either fulfil dreams or seize better opportunities, the exodus has also occurred recently due to natural disasters, poverty, and political unrest.

11Occasionally, the Minangkabau who have migrated do not return home to Sumpu.

12 Indonesian researcher Heru Joni Putra explains that despite not returning home, the Minangkabau are responsible for monetarily developing their hometown or creating opportunities through youth mentoring. Putra clarifies that returning home can mean either physically or “in the form of “name”—if you still send assistance or help people in the village, then generations in the hometown still remember your name.”

13This article addresses how the intent, meaning, and valuation of the concepts of home and placemaking function in these photographs. The artistic practices of Sokchanlina and Pieter articulate collective identities and histories that frame the photographic narrative within a sociopolitical discourse. The following sections define home and placemaking as contextually nuanced sites relevant to people and communities.

4. Comparative Implications through Photography

Artist-curator Zhuang Wubin critiques that the Southeast Asian photographic practice hovers problematically between being characterised as art and being a documentary account in journalism (

Wubin 2017, p. 13). Wubin additionally explains that the classification remains problematic because there are no valid criteria for the distinction between an artist photographer and a documentary photographer. He argues that multidisciplinary artists who use photography in their practice are not considered journalists, yet those historicising events or landscapes through photography become documentary photographers. While discourse on the photographic practice of Southeast Asia lies beyond the scope of this article, unequivocally, the “reductive positions” (as used by

Wubin 2017, p. 13) and limitations of compartmentalising these dual qualities do not preclude how Sokchanlina’s and Pieter’s practices remain entrenched in social change and action. The artists’ frame of reference is the knowledge production and experiences within Southeast Asia. Their artwork spatially and temporally roots placemaking within the larger sociocultural, regional, and political context. Their photographs preserve sites, producing particular spatial identities reiterating ideas of place according to migratory narratives and patterns observed through time. These photographic narratives, while enabling comprehension of tangible and visible developments in the communal landscape, are also associated with posterity.

The medium of photography demands embodied responses from the single moment of existence captured by a camera. Embodied responses using multisensory counters—such as odours, physical sensations, perceptions, and auditory aids—are not represented in photography, a visual medium. However, the translation of the visual medium accesses memories, engages the senses, and intensifies the viewer’s experience. Moreover, the methodology raises critical inquiries into viewer subjectivity regarding historical and generational narratives often present through objects in the home (for example, ancestral property or heirlooms). Lim Sokchanlina’s and Yoppy Pieter’s photographs portray the aesthetics of home by documenting Cambodian and Indonesian migratory accounts. By responding to the memories contained in the photographs, the artworks reveal the meaning and value (for the migrant) of the transitory landscape.

The artists create photographs that enable the perception of a community and express said community’s principles. Sokchanlina and Pieter record the nature of migration due to economic prosperity in Cambodia and Indonesia. Their chronicle of the dwelling enables the perception that home is that which is left behind, a permanent, mythical place that holds memories, yet hints at the probability of return. The artwork enhances our understanding of the continuing reconstitution and reconfiguration of place and identity. The photographs demonstrate the ability of individuals and the community to be resilient in the face of shifting landscapes, while acknowledging the transitional nature of society today. Pieter examines the lived experience of a community whose members continue to migrate, leaving behind their homes in search of financial well-being, while Sokchanlina critiques the displacement of Cambodians due to national infrastructure development.

5. Home

Philosopher Martin Heidegger uses an etymological and lexical approach to methodologically critique the similarities between the German words home (dwelling) and existence (to be) (

Heidegger 1975, pp. 146–47). Heidegger argues that a home is an extension of ourselves and our identity only because we build structures, systems, and ideologies to address our needs. A house implies isolation from worldly demands, engaging in “active place-making” because of disassociation from the outside environment (

Handel 2019, p. 4). The relationship between public and private realms, the objects inside the house, and the movement of people inhabiting the spaces strengthen the disparate identity of the home. Elements accumulated during the creation of a home, akin to an assemblage, produce a more nuanced methodology for placemaking.

14 An assemblage reconsiders ideas about a place based on “process, identity formation and becoming.” (

Dovey 2012, p. 374). The assemblage allows a home to become more than a physical building by recognising the personal and social needs the home serves. An assemblage is a tool aiding comprehension and representing connections between social boundaries, construction of the self, and expression.

Home is a universally essential and implicit concept intriguing scholars such as art historian Claudette Lauzon who has written about the strategies artists use to convey the meaning of home (See

Lauzon 2017). Her book discusses some artistic practices in Euro America regarding the meaning of home in the West in the twenty-first century.

15 Nevertheless, in the exhibition canon, Southeast Asian artists have alluded to their homeland using national and regional history as a methodology.

16 The notion of home conceived through memories and archived in photographs, anchors and makes visible these memories, mirroring that which exists and preserving it for posterity. Knowledge production in photography occurs through forming a pictorial narrative of nostalgia, “an imaginary possession of a past”, embodying time and place and portraying the lived and the perceived experience (

Sontag 2005, p. 6). Scholar John Roberts argues that photography exercises “a singular event”, whereby elements align pictorially (

Roberts 2009, p. 283). Roberts continues to explain that this moment comprises the historicity of the image, creating a moment wherein the photograph is predisposed to a condition of having taken place in history.

The identity of its inhabitants fashions the home as an object. A biography of objects is dependent on transformations that occur through time. Moreover, people are “[…] ultimately composed of all the objects they have made and transacted, and these objects represent the sum total of [a person’s] agency.” (

Gosden and Marshall 1999, p. 173). The home gains social relevance by emphasising the shared biography between a dwelling and its residents. Consolidating people with their belongings weaves together the histories of objects and people.

17 Metaphorically the home collects, records, and preserves memory, thereby being singularly associated with the occupant’s life. Photography expresses how the home (an object) is manipulated and interpreted through a broader narrative of placemaking. The home symbolically enmeshes Southeast Asia’s sociopolitical and cultural processes.

6. Placemaking

The concept of place usually means a geographical location, and space is a metaphorical interpretation and experience of place.

18 The nature of place and space is abstract and indefinite as they comprise “embodied experiences” reciprocally created from knowledge and participation within that location (

Ganapathy 2013, p. 98). According to ethnographer Monika Palmberger, places “are continuously renegotiated”, and their “multiple interpretations” exist together (

Palmberger 2022, p. 93). Contextually, places become meaningful upon connection with identity and memory. The approach towards spatial production is mainly subjective and constantly fluctuates over time depending on cultural, sociopolitical, economic, and historical contexts. Place is located spatially and temporally and can be created and recreated through communication, observation, and interaction, allowing for a constantly evolving form of placemaking. Moreover, it constitutes space claimed, generated, and made through dynamic experiences, making present geographical locations and transforming that particular site’s function and materiality. Placemaking is a multifaceted concept referring to the arrangement and design of infrastructure and amenities, but also proactively denoting meaning and identity to the location by conveying its shared history.

19Placemaking enhances the aesthetics of place and reinforces the relationship between people and their environment. Hence, when applied within a community, it brings to the forefront cultural traits that tie the community together, such as shared connections and histories because of a common cultural heritage.

20 Since dwellings conceptually embody intangible practices of placemaking ascertaining meaning and purpose, homes categorically become a narrative to reconfigure transitional patterns—those of movement or migration. The nature of migration involves clinging to ideals of home, while concurrently negotiating external forces that caused the migration. For a migrant, the home ceases to exist, signalling the end of a spatial and temporal experience. In a globalised world with its shifting landscapes, the migrant becomes a “self without place” (

Casey 2001, p. 684). The migrant nomadically deprives the self of cultivating identities and networks based on place. The resulting contestation alludes to the lack of an attachment that makes a home “simply a point of departure.” (

Purichanont 2020, p. 49).

Further challenging this line of enquiry are manifestations of sensory emotions between self and place, allowing for stimulating artistic developments that deliberate the home’s cultural and spatial identity. Lim Sokchanlina and Yoppy Pieter visually manipulate the aesthetics of belonging, depicting distinct versions of home as personal and communal spaces. Their photography embeds conceptual references by recognising that comparative differences exist, yet allowing those differences to generate new trajectories regarding place and home in Southeast Asia. The home becomes emblematic of the inhabitants’ experience, sustaining knowledge that is private, public, and existing in a “third space” (as propounded by Homi Bhabha) in between. The hybridisation of these modes of knowledge produce perspectives that are “highly differentiated yet [an] inevitably connected whole”, signalling diversity, a characteristic feature of Southeast Asia.

21Sokchanlina and Pieter explore a three-fold intent of place, having a geographical presence, an environment to conduct social relations, and an entity encouraging inherent attachment, constantly shifting between the various connotations, creating intermediary nuances between the meanings. Their photographs portray a mode of resistance against ideas of migration and spatial restructuring by actively redefining the essence of home as a site containing life. The artworks, as a narrative form of resistance, are a conceptual strategy addressing the migratory realities of Southeast Asia. The artists generate images that provisionally draw attention to the home and the aesthetic encounters with place, triggering associated memories and emotions. While Sokchanlina’s photographs indicate human existence only through objects that remain in the abandoned house, Pieter photographs people who showcase the significance of a community in making a place a home.

7. Comparative Analysis of the Artworks

It is essential to begin a comparative analysis of Sokchanlina’s and Pieter’s art keeping in mind that migration in Southeast Asia has remained a survival technique adopted to evade natural and manufactured disasters. Sokchanlina and Pieter create art about the home as it centres around a dialogue about contemporary life in Cambodia and Indonesia. This section will analyse the individual photographs (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) and then compare and contrast the images of Sokchanlina with those of Pieter.

Economically motivated migration in Cambodia has enabled Sokchanlina to juxtapose a house’s demolition with the constructed, expanded highway in front of it (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). In the images, the home possesses objects (clothes, kitchen implements, a vehicle, miscellaneous items) located in the bisection of the dilapidated structure. The home remains a semblance of a once liveable site. Household artefacts, surplus doors, fencing, and asbestos sheets within the dwelling produce intangible and embodied responses articulating the history of the place—the nature of it having been once-habitable and the denial of its sudden destruction (seen through the number of items left behind). Nevertheless, the meaning of place coherently suppresses the imagery of the house (in

Figure 1) split into two halves and the residence (in

Figure 2), comprising only walls and no roof, exposing damaged rebar, brick, and cement.

The Chinese signs around the door (in

Figure 2) bless the inhabitants with prosperity and good fortune, producing an identity related to the place and home. Placemaking, denoting identity to these homes, takes on a paradoxical form—the destroyed home prevails in the foreground, while new construction of a dwelling-like structure occurs in the background (as seen on the right in

Figure 1). In this case, place’s nuance and implication contextually change according to distance—measuring mere meters. The artist confronts and critiques changing landscapes to address what is lost, while acknowledging what is new. For instance,

Figure 2 produces an impression of the home being a transitory space because of its ruined state and because the car’s presence subtly suggests movement. Sokchanlina seemingly documents the impersonal and neutral testimony of a location compelling the viewer, as an agent, to affix intimate details (to location), thereby enhancing the meaning of placemaking.

Sokchanlina’s

National Road Number 5 2015 #3 (

Figure 3) exhibits a structure that remains concealed and shielded from view by a blue tarp that neatly wraps around broken pillars on either side of the dwelling. The intact blue clay tiled window awnings on both sides of the house beautify and contribute to the home’s value and worth. The encased structure also lends the impression that it is not vacant because of the ladder leaning precariously against the damaged plinth towards a narrow corridor serving as an access point. Even upon the structure’s condemnation, the inhabitants’ continued residence in the establishment preserves the significance of place. In this particular image, Sokchanlina focuses on and critiques the transitional phase, the temporary manifestation of a home, the third space in between, by highlighting the relationship between human beings and geographies.

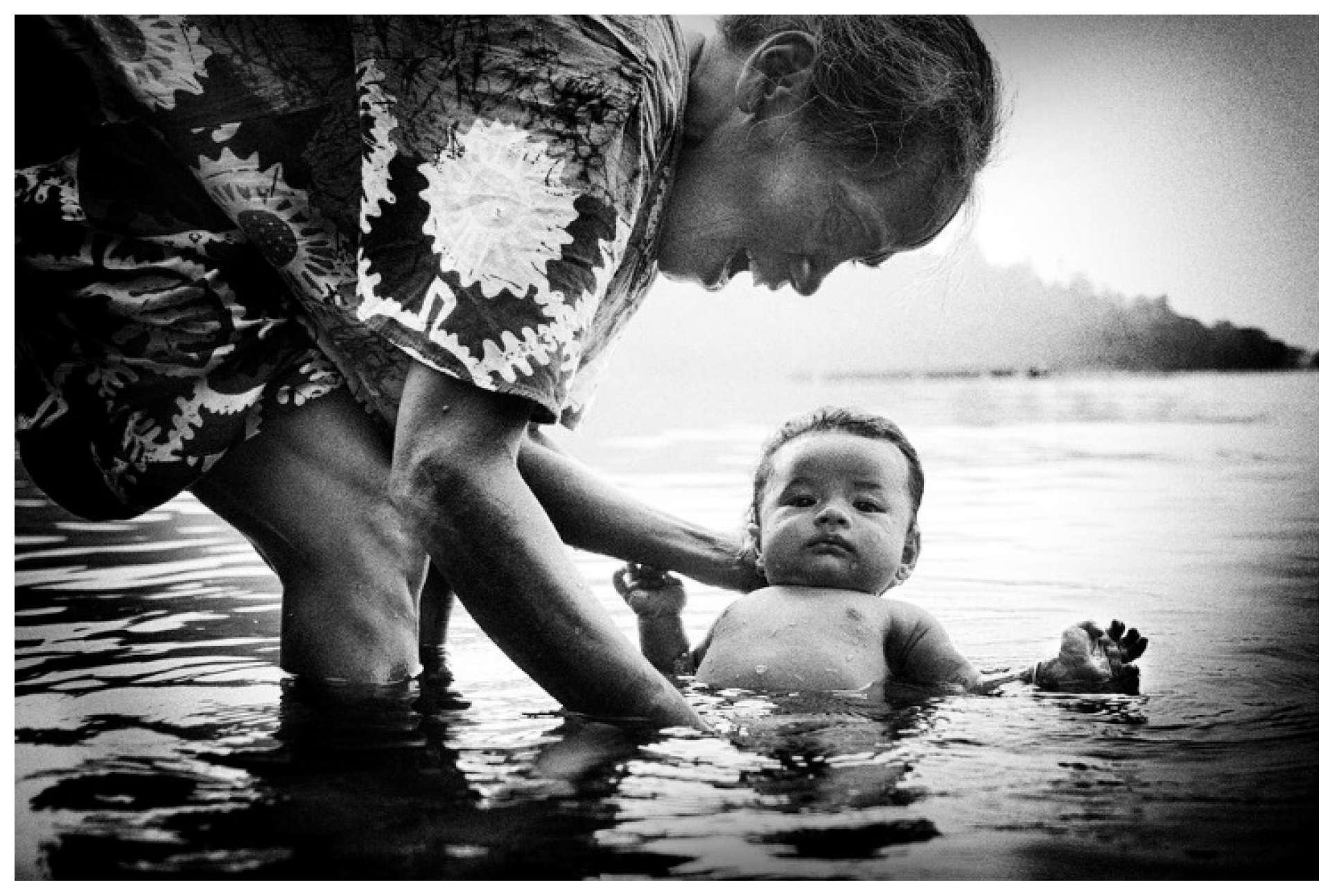

Yoppy Pieter’s photographs extend the meaning of home as comprising a slowly shrinking community. Home in Pieter’s art demonstrates collective modes of storytelling and intergenerational histories (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). His artworks make the viewer privy to genuinely visceral moments between people in the Sumpu community. Titles and photographic descriptions by Pieter in his artist book with the same name as his series, acknowledging members of the community depict his attachment to the Sumpu village, enabling the creation of a bond between the photographer and place. For instance, in

Bath by the Lake (

Figure 4), Pieter credits Sasmiati for bathing her granddaughter, who revels in her family’s return to Sumpu from the city.

22 Pieter’s intrusion upon the family is apparent through the granddaughter’s gaze at the photographer instead of at her grandmother.

Pieter’s photographs also attest to the aesthetics of home as a place inherently nostalgic, rendered by the romanticised use of only black and white imagery.

The Ancestors (

Figure 5) depicts antique heirlooms, belonging to

Datuk Basa nan Tinggi from the 1900s, of images of Bungo Padi (on the left) and Reno Urai (on the right).

23 Pieter has portrayed family descendants continuing to live in the same place as their ancestors. The possession of genealogical ties to place equates the meaning of family to that of home because place symbolises the family’s roots.

Datuk Basa nan Tinggi, who is not pictured, but whose wrinkled hands clutch the heirlooms, sustains not only the cultural memory of the Sumpu people but also preserves the biography of the relics.

The Ancestors metaphorically depicts how antiquities construct narratives about place by demonstrating that the object is a substitute for home and earth (seen through the obscure background).

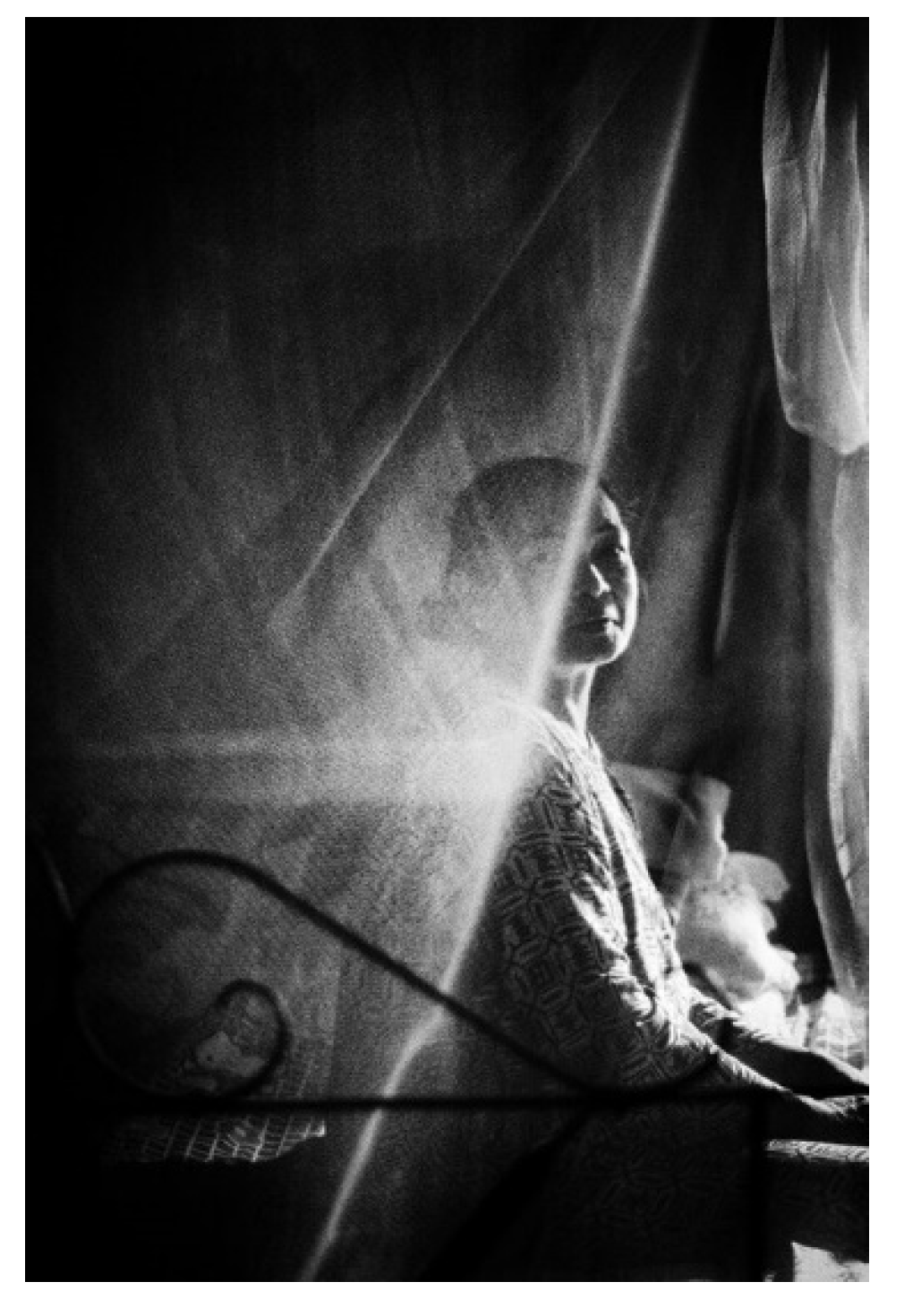

Pieter’s

Asnah (

Figure 6) gazes steadfastly at the viewer through softly lit sheer curtains, activating the space between the viewer and the titular character. This space activation triggers fictional, inherited, and authentic people-oriented narratives mapping connections with, and resonating with the spirit of place. Asnah defiantly sits on her bed in her dilapidated

rumah gadang (traditional home of the Minangkabau).

24 Asnah pointedly looks at the photographer, suggesting that even as her house crumbles around her, she will endure because her place as the Minangkabau is in Sumpu.

Sokchanlina’s coloured images of structures resembling homes reproduce contemporary urbanisation markers (for example, electricity cables, modern vehicles, and building scaffolding). Pieter’s vintage and archaic greyscale images omit suggestive temporal and geographical indicators. Pieter’s photographs imply the feeling of being home, part of a close-knit community, without directly depicting a dwelling. Both artists portray how place equates to home by featuring interaction with spaces and collaborations between people and place. Sokchanlina and Pieter use aesthetic and conceptual strategies to simultaneously position and demonstrate the coherence of concepts such as home and placemaking—depicting how they are merely two sides of an entity. The National Road Number 5 and the Saujana Sumpu series showcase contemporary urban restructuring that melds together geographical, cultural, and temporal processes.

The juxtaposition of cross-cultural identities (in the case of Cambodia and Indonesia) reveals how the concept of place supplies the sense of self. The houses along national highway 5 remain in varied stages of destruction. While their actual location and identity are anonymous (Sokchanlina provided no addresses), certain distinct features of the home prominently represent attachments to place—the photograph of the wrapped home denotes a family reluctant to leave their residence. Familial bonds root the Sumpu community’s identity to place, making home essential in establishing history, meaning, and memory. While no distinct environmental markers designate the photograph’s site as Sumpu, people in the photographs indicate the attachment to the locale. Sumpu attempts to re-establish connections to land, as evidenced by the community welcoming Pieter to record the mundane. The artists creatively process ties that individuals and communities have with the land, tracing changes in the landscape and recording movement of the past and the present.

8. Conclusions

“Language, identity, place, home: these are all of a piece—just different elements of belonging and not-belonging.”—Jhumpa Lahiri (

Ghoshal 2014).

In her quote, author Jhumpa Lahiri references a methodology through which the word belonging has its roots in culture, physical space, or a belief in particular values. Global contestation of formal state structures such as border control implements differences between belonging and not-belonging. Nevertheless, the essence and meaning of Lahiri’s statement encompass and transcend physical demarcations, contextually justifying a broader framework for the sense of belonging. The nature of belonging evolves and demonstrates the necessity to address, empirically and theoretically, overarching concepts such as migration, displacement, exile, and diaspora.

Placemaking embraces experiences, cultures, and relationships located within the biography of a person, creating their identity. The notion of home generally remains absolute, unchanging, and constant. In the case of migration, concepts such as location and dwelling become part of the series of objects and ideas that need replacement, exchange, and renegotiation. A home can then be interpreted as a site enclosing the lives of those who inhabit it, contextually producing a relationship between place and people. How the placemaking narrative is used in photography, embodying personal and collective memories within particular sites, augments the perception of a habitat. Photographic aesthetics in Sokchanlina and Pieter’s art designate the locale of home as meaningful, critically enquiring (the locale’s) geographical, sociocultural, and temporal processes.

While the framework of placemaking and the aesthetics of home in this article have been considered from the perspective of photographs by Sokchanlina and Pieter, the concepts mentioned have not been applied to the larger national or regional context. The narrow scope has also disabled dialogue about the problematics of place and home occurring in metropolitan and rural areas—which the artists allude to in their artwork—but remains unaddressed in this article. This article’s cursory examination of migration also deserves further scrutiny to consider the impact of nomadism on placemaking. Several queries regarding this field of study arise, such as categorising the characteristic features of placemaking and the aesthetics of home. The parameters of placemaking require a definition so that its principles can be applied universally, regionally, or even worldwide. Other inquiries consist of how the aesthetics of home differ for people without private residences and how object biographies influence the aesthetics of home.

Lim Sokchanlina’s and Yoppy Pieter’s photographs document the meaning of home for those displaced along national highway 5 in Cambodia and those in Sumpu, Indonesia. Their methodology of using placemaking to deconstruct the traditional model of a home using contemporary art with a community’s heritage creates a unique Southeast Asian identity. Homes are sites of processes associated with spatially produced memories by imagining the human body in a particular place. Establishing human presence and anchoring humanity within terrestrial parameters links the present to the past, promoting shared histories and integrating cultural identities.