Abstract

This article examines the notions of history and memory with references to the works of contemporary artists from Iran. It interrogates the theme of challenging the present through the re-interpretation of history and investigates how artists respond to social, cultural and political conditions by creating a multi-faceted aesthetics of resistance. While looking at the broader subject of history and memory in contemporary Iran, the article scrutinises the works of artists who have been involved in themes such as the embodiment of cultural memory, concern for truth, historical record and intellectual reference to history to reflect the present. I adopt a hauntological interpretation when reading works of artists as it corresponds to their recurring references to the past to invoke an unsettling view of an imagined future.

This article aims to explore the notions of history and memory with references to the works of contemporary artists in Iran. It interrogates the theme of challenging the present through the re-interpretation of history—from the pre-Islamic ancient time to the recent past. It investigates the way that contemporary art engages with conditions of social, cultural and political issues to suggest alternative approaches as critical tools that could create a multi-faceted aesthetics of resistance. I use the concept of hauntology1 as a set of ideas concerning the return or persistence of elements from the social or cultural past, as in the manner of a ghost. Specifically, I will adopt hauntological interpretation when reading works of artists as it corresponds to their recurring references to the past to invoke an unsettling view of an imagined future.

While looking at the broader subject of history and memory in contemporary Iran, the article scrutinises the works of artists who have been involved in themes such as the embodiment of cultural memory, concern for truth, historical record and memory and intellectual reference to history to reflect the present. I argue that artists have not been absorbed by the Iranian state’s soft power, which aims to impose its political and ideological values on the nation’s life. It is inevitably related to the questions of power and resistance. Thus, I further contend that artists’ resistance is debated through their works by referring to themes such as political history, cultural memory and power relations. For these artists, ‘past truth is violated not only by making the past falsely identical to what it is now, but also by making it falsely different from what is now’ (King 2000, p. 3). Here, the main objective is examination of works of artists that signify the perception of history that is constantly fastened with the present understanding, since to ‘know about the past is to know about it in the present’ (ibid.). This perception echoes John Lukacs’s notion of a ‘participant history’, in which ‘[o]ur knowledge is not only personal; it is also participant’ (Lukacs 2008). In what follows, I will demonstrate how references to history and memory are unavoidably an engagement with the interpolation of the present, usually with an intention to reveal truths of both the past and the present. As such, each individual, including artists, can determine their own narrative of history.

The main questions that need to be answered are ‘How do contemporary artists in Iran now position themselves in relation to history and past memories and what are the main strategies when these themes are reflected in their works?’ The answers should be related to the ontological questions with which artists who aim to address their conditions of contemporaneity have been engaged; namely, critical re-tellings of the past, a past that no longer exists but keeps haunting the present like a ghost. These critical perspectives are addressed through approaches such as irony, fantasy, intertextuality, mimetic perversions, deconstruction and de-familiarisation.

Hauntology provides a useful descriptor in our lines of inquiry, particularly when dealing with the topics of historical memory and trauma. According to Derrida, the aim of hauntology is to learn how to ‘let them [ghosts] speak or how to give them back speech, even if it is in oneself’ (Derrida 1994, p. 221). Just as the ‘hauntological’ musicians are explained by Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds, the works of these artists explore ideas linked to temporal incoherence, cultural memory and the persistence of the past (Whiteley and Rambarran 2016, p. 412; Fisher 2013). They also signify the enigma of place and placelessness, memorial and longing. Furthermore, as Sadeq Rahimi explains, the logic of hauntology contradicts any established order of power or meaning to the extent that it recognises as haunted the very ‘essence’ of reality and, more importantly, to the extent that it concurrently challenges the most foundational principles of both Utopianism and Messianism (Rahimi 2021), p. 5). Discussing the political significance of the concept, Fisher also wrote, ‘[w]hen the present has given up on the future, we must listen for the relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past’ (Fisher 2013, p. 53). As we will see, this is the very nature of the works of artists, explored here, specifically within the political context of Iran.

Within the hauntological context, as Rahimi maintains, ‘all concepts are haunted, and they have to be haunted before they can become concepts’ (Rahimi 2021, p. 6). The central idea here is that the interconnection of the physical and the symbolic is where both meaning and ghosts are born (ibid.). It is related to the notion that the creation of meaning is a hauntogenic2 event, since ‘the process that produces meaning also creates spectral traces of the original events and entities that are made sense of’ (ibid.). Rahimi further contends that through ‘each wave of elevated representation spectral traces of the signified entities and experiences are also produced, silent/negative references to an original object which “haunt” the new signifier’ (ibid., p. 9) It is through hauntological interpretation that works of artists open a reflexive and critical function for art by demonstration of fragments of historical reality that have been inserted in the narrative frames of history. In this process, to generate a creative approach to the past along with a political action, artists typically use some abstraction or elision of historical concepts.

To examine hauntological facets of works of artists, I will focus on two series of artworks: Parham Taghioff’s Asymmetrical Authority (2018) and Mohammad Ghazali’s Persepolis: 2560–2580 (2021). These works challenge and deconstruct the dichotomy between historical and contemporary discourses and how they speak theoretically and aesthetically in their own right by reflections of self through narrating history and collective memory. The choice of artists is based on criticality and specificity of their work in relation to the post-revolutionary Iran, each deeply affected by their dealings with their cultural communities and historical legacies, and each with a distinct practice and a singular perspective on the relations of history and truth. Their works offer alternatives to hegemonic historicisation and demonstrate the critique of power relations and interventions in the processes through which history is narrated.

1. Historical Narratives and ‘Official’ Ideological Intervention in Contemporary Iran

Historical awareness in modern Iran developed in parallel with the country’s political and social development. Modern Iranian nationalism, which resulted in establishing a modern state, was based on an Iranian awareness of ‘national’ identity with an emphasis which relied upon the pre-Islamic history of Iran. This history, most of which had been lost in myths, was discovered in the nineteenth century through the attempts of European archaeologists and philologists. The Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979) that based its modernisation process particularly upon the adoption of Western civilisation aimed at integrating it with the historical traditions and ancient ancestral honours of Iran. Reza Shah (ruled 1925–1940) turned a carefully crafted vision of nationalism, a so-called ‘romantic nationalism’, that celebrated Iran’s pre-Islamic heritage.3 The nationalist political elites reflected their eclecticism through their advocacy of pre-Islamic Persian splendour with a strong sense of Persian chauvinism. The glorification of such historical myths as Cyrus the Great, the founder of the first Persian Empire (ca. 600–530 B.C.), and the archaeological site of Persepolis was a part of this notion (Merhavy 2019). It also resulted in fascination of Iranians with ancient Iran or Iran’s ‘glorious’ past and the national pantheon. Richard Cottam points out that the Iranians’ cultural consciousness in the Pahlavi era allowed them to view themselves as one of the peoples deserving of respect and admiration of the international society. Such a feeling of uniqueness helped greatly in the integration of nationalism in the popular mind (Cottam 1979). With the 1978–1979 Revolution and the eventual formation of the theocratic state, Islamic revolutionary ideological discourse replaced the modernist secular Pahlavi politico-cultural practices. It inevitably affected Iranian social and cultural life in a radical way. During the revolutionary struggles that followed by the eight-year bloody war with Iraq (1980–1988) the Islamic Republic’s singular ideology dominated all various domains of Iranian life, including cultural endeavours. As Ludwig Paul correctly put it, the post-revolutionary state’s most important slogan is ‘“Islamic government” (hokumat-e eslāmi): In establishing this the Revolution aims for a total Islamization of state politics, society and the individual4 (Paul 1999, p. 190). The inevitable outcome of this system has been an ideological Islamization (Haghayeghi 1993). Herein, the essence of the state’s version of Islam is to invalidate the autonomous individual. One of the key issues with which the identity of the Islamic Republic has become engaged has been their constant enforcement. In brief, the aim of the theocratic state is to formulate an ideological definition of how the ‘New Iranian Man’ should behave and even look (Paul 1999, p. 205).

In the early years of the post-revolutionary period, as opposed to the Pahlavi’s nationalist policy, the political slogan of the Islamic Republic based on ‘export of the revolution’ meant crossing the barrier of nationality and carrying the message of a universalist ideology, namely Islamic unity. In addition to the political and cultural enforcement, in later years the state funded various official events and publications to counter the increasing trend among Iranians to look back to the pre-Islamic Persian history. Through these official projects, the state has tried to belittle or ignore cultural festivities and sensibilities that are considered uniquely ‘Iranian’ (Farhi 2004) According to the Islamic Republic’s official ideology, Iran’s pre-Islamic past is to be understated and its Islamic heritage worshiped, while Western cultural values are to be replaced by their Islamic counterpart (Haghayeghi 1993). Consequently, the Islamic Republic’s cultural policies in essence, from the beginning, contained both ideological and political elements. They were introduced as ‘principles’ of Iran’s ‘Islamic’ identity and means to be used against cultural aggressions.5 It has been said that the forceful post-revolutionary imposition of Islamic values and ways of living was an ideological attempt to fuse culture and religion and to construct a unified set of values (arzesh-hā) and proscribed principles. The state sought to assert cultural authenticity for its formulated agenda and reject any other practices that did not possibly match its own (Farhi 2004).

Along with control of the media, the state established the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (Vezārat-e farhang va ershād-e eslāmi; formerly called the Ministry of Islamic Guidance, Vezārat-e ershād-e eslāmi)6 to formulate and coordinate its ideological policies and to oversee the activities of the media and other cultural enterprises. In particular, the ministry developed overall control of cultural productions, as evident in censorship and repression of the press, writers, film makers, academics and political dissidents.7

However, the outcome of the Islamic theocracy politicising all aspects of Iranian social and cultural life generated multiple contradictions and conflicts. The conflicts inevitably have appeared within various social, political and cultural sections, which have held differing political and ideological views—mostly, expected independence, freedom and social justice. These have included cultural practices that have resisted and refused to vanish. Therefore, despite the state’s obsessive preoccupation with the politico-screening of the cultural enterprises, with some degree of certainty, it has been least successful in its efforts to institutionalise its reign. One can detect cultural counter-reactions formed within new interpretations of national culture and counter-narratives of the state’s hegemonic narrative also manifested in artistic practices. The outcome of this resisting act is the creation of artworks that represent iconography of socio-political and moral contravention—creations that turn into appliance of socio-cultural criticism and political contention. Many artists, particularly from the new generation—born after the revolution, now comprising a large portion of Iranian society—challenge such compulsory settings that aims to direct and dominate systems of belief and actions. These artists try to repossess and redefine individuality by generating discursive strategies through which they can critically approach their practices and the state’s politically formulated history and cultural past. Their attempt to reclaim their own cultural space is another indicator of the state’s ideological crisis.

If contemporary art practices are presentations and dialogues that are responsive to our times, contemporary artists in Iran try to explore histories that continue to shape their present. Focusing broadly on evolving notions of Iranian belonging, their work urges audiences to reconsider their political and national understanding of such histories and allows the complex pasts to be articulated as integral to contemporary narratives. Their art has provided a means to engage with history, politics and society in the present. As a result, the specified official formula has been replaced by multifarious ways in which history can be imagined and narrated.

The painful history of the revolution, war, mass political executions,8 systematic elite killings (the so-called chain murders),9 cultural repressions and international sanctions has created a traumatic experience for Iranian collective memory which keeps haunting the present life of Iranians. Seeking to find an appropriate language with which to tell a story embedded in pain is what many artists are now grappling with. Their work is a response to their own experiences in the context of a cultural trauma pervading the whole society. In the conditions of daily challenges, artists have to cope with challenging conditions for living, let alone practising art. The result is a range of artistic practices in which artists search for the strategies to effectively interpret the traumatic experiences in their country.

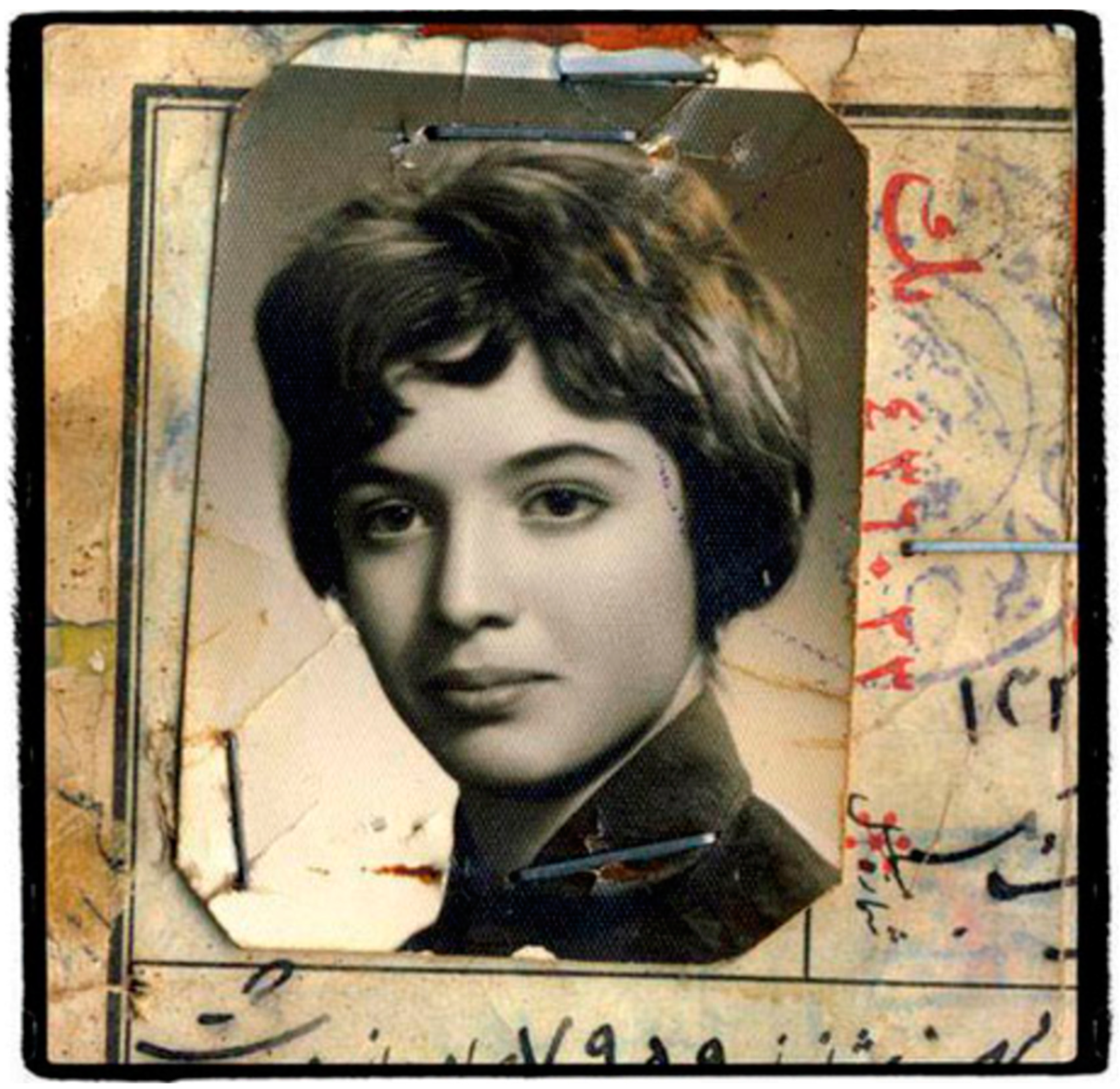

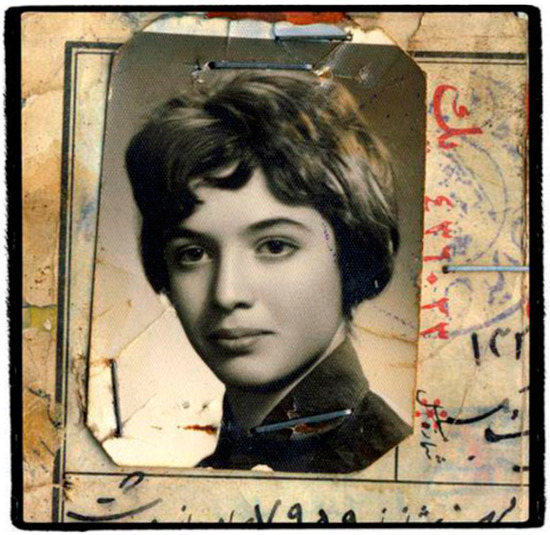

Several artworks in contemporary Iran subvert the traditional telling of history and enable rethinking of the past as the basis for the individual’s existence in the present. Examples of these works vary, but before scrutinising the main case studies, here I would like to address a few other examples. Among many others are the dreamlike fantastical imagery in the paintings of Mehdi Farhadian (b. 1980, lives and works in Tehran), the interrogation of recent Iranian history and collective memory in the staged photographs of Azadeh Akhlaghi (b. 1978, lives and works in Tehran) and the found images of Najaf Shokri (b. 1980, lives and works in Tehran). These are artists from the same generation, mostly born after the revolution. Farhadian’s canvases depict visually dramatic scenes in which inhabited people and animals are joined in enigmatic acts. For example, works in his exhibition Twilight (2020) fuse realistic and fictional narratives of Iran’s modern history, mainly referring to the Pahlavi period (Figure 1). Farhadian’s fantastical imaginary demonstrates his self-utopic accounts of this history, visualising the hidden melancholy resting in the architectural spaces, human characters and all the other elements of the pictures. Akhlaghi’s stage photography project By an Eye Witness (2009–2012) is a series in which she scrutinises history of Iranian intellectuals in the twentieth century by reconstructing the death senses of seventeen iconic figures including journalists, activists, filmmakers, poets and politicians with her own presence as an ‘eyewitness’ (Figure 2). Addressing the ever-present troublesome and tragic destinies of intellectuals in modern history of Iran, the By an Eye Witness series indirectly tests the interrelated parallels under the Islamic Republic. While the artist seeks for the ‘truth’ in following the narratives of eyewitnesses and information derived from archives, it touches upon key questions concerning personal histories, visual memory and the question of ‘documentation’. Najaf Shokri’s Irandokht (daughter of Iran, 2006/2009) presents found photographs of young women from old ID certificates mostly issued in the 1940s that were all invalidated and discarded in the post-revolution period by the National Civil Registrations Organisation (Figure 3). These personal photographs were taken during the Pahlavi era and therefore the appearance of women in those pictures did not meet the Islamic Republic’s code of compulsory hijab. These now-anonymous portraits signify an almost forgotten past and a controversy over prescribed amnesia by the post-revolutionary authorities. Furthermore, his act of ‘recycling’ contributes to the formation of a personal historical account while resisting the systematic removal of historical record and memory. Without being involved in the exoticisation of the artwork,10 these pictures act as microcosms that reveal the tensional history of Iranian women in post-revolutionary Iran.

Figure 1.

Mehdi Farhadian, After Storm, 2017, acrylic on canvas, 130 × 180 cm.

Figure 2.

Azade Akhlaghi, Evin Hills, Tehran, Bijan Jazani 18 April 1975, 2012, digital print on photo paper, 110 × 209 cm.

Figure 3.

Najaf Shokri, from the Irandokht series, 2016, sonography, digital print on paper, 20 × 20 cm.

In what follows, I will further scrutinise the re-interpretation of history and cultural memory by concentrating on the main case studies.

2. Parham Taghioff’s Asymmetrical Authority (2018)

Parham Taghioff (b. 1978, lives and works in Tehran) explores the strategies by which the artist can process the past that, if unprocessed, would create a traumatic pressure on the present and a distortion of a possible future will reveal itself. Mieke Bal, in her book Of What One Cannot Speak, Doris Salcedo’s Political Aer, examines how violence is recorded through art and places an emphasis on the interlinking of art and politics. Her argument addresses the ways in which the issue of memory is associated with the traumatogenic event, an event that is not essentially traumatic in itself but can engender traumatic effects. She argues that an artwork emerges from a collective or culturally violent event that has the traumatogenic status (Bal 2010; de le Court 2020). In the same vein, Taghioff’s work signifies a kind of hauntological reference to the recent traumatic past. It addresses cultural repression and re-shaping memory within the multiple historical conditions in contemporary Iran. Through the reproduction of historical images while aiming at evacuating their signification and exhuming new interpretations, what Taghioff seeks to exhibit is the failure of photographic image not only to record reality reliably and to authenticate memory, but also to address the ruptures associated with traumatic experience.11

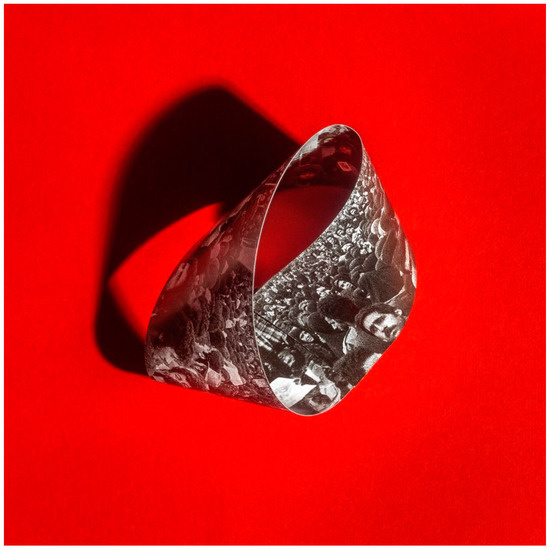

In the Asymmetrical Authority series (2018), official memory degenerates into fragments of personal memories of the artist, enabling a new historical perspective. It consists of simultaneously recognisable and bizarre images imprinted with the recent political history of Iran. They give form to his fragmentary pictures and make the familiar unfamiliar. This reconstruction of history works with and re-contextualises well-known imagery to subvert the viewer’s perceptions. Taghioff aims to direct our attention at the fact that photographic images require context to assume meaning and carry a message. According to Lutz Koepnick,

[N]o image, has an existence or memory of its own. It is what we do with them that decides over their life and afterlife. It is how we situate them against the backdrop of other narratives, discourses, images and strategies of representation that enables them to speak in various ways about the past and its bearing on the present.(Koepnick 2004, p.102)

Taghioff himself asserts,

[T]he camera has the capacity to challenge our understanding of the past. Through reproduction … photography undermines the authority of the original and the sanctity of the author.At the same time, however, the sheer volume of the images in our daily lives diminishes our capacity to discern the historicity of the past. Everyone has acquired the power to establish the meaning of images and by extension, the meaning of history… Today, more than ever, the meaning and significance of images are established in the context of their circulation and reception. The truth of images, in other words, lies beyond their genealogy in a particular time and place. The question is how [do] we locate images in historical narratives and memories, and how do we draw on living images to tie together the past, the present and the future [?](Sumac Space 2021)

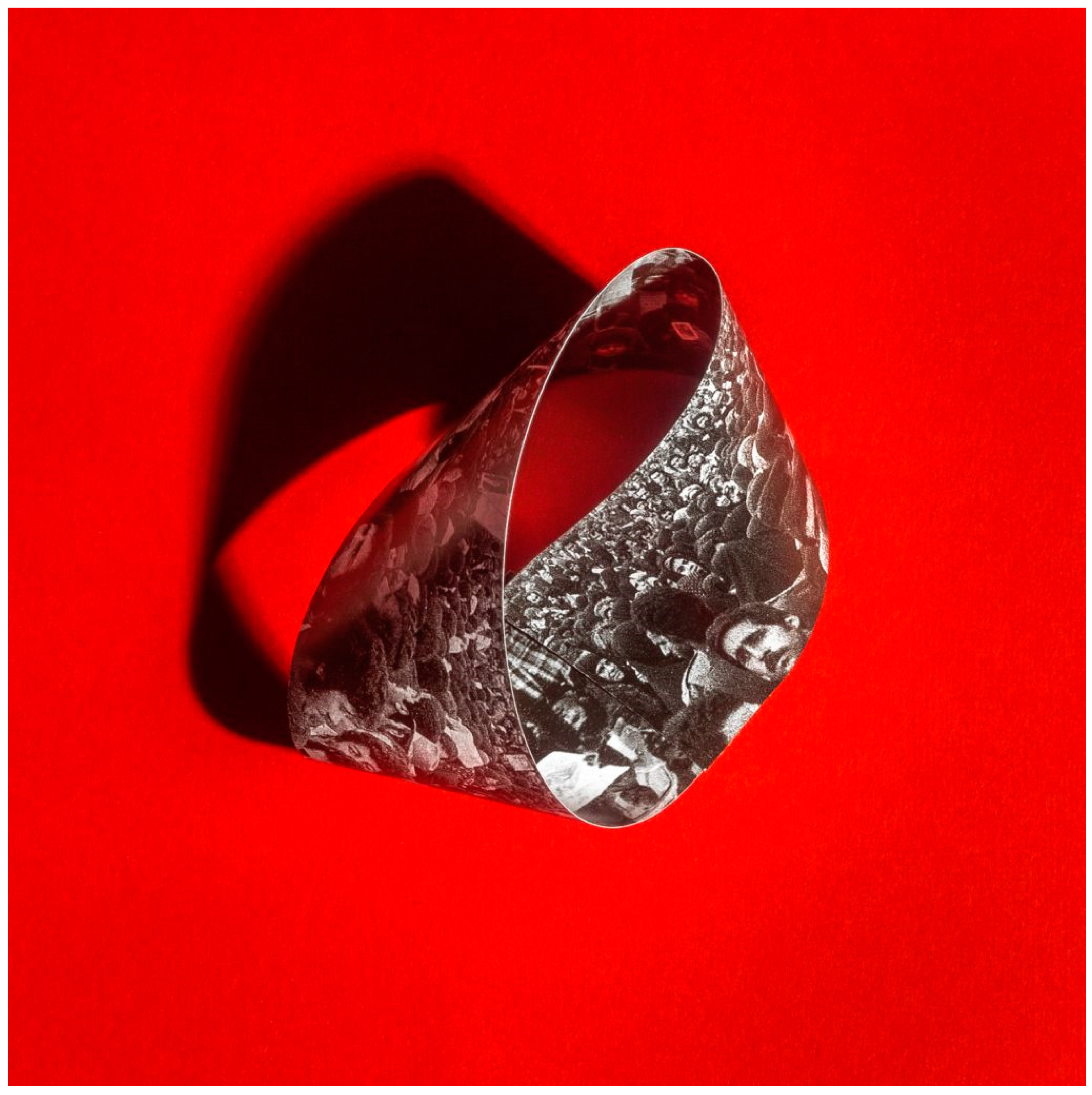

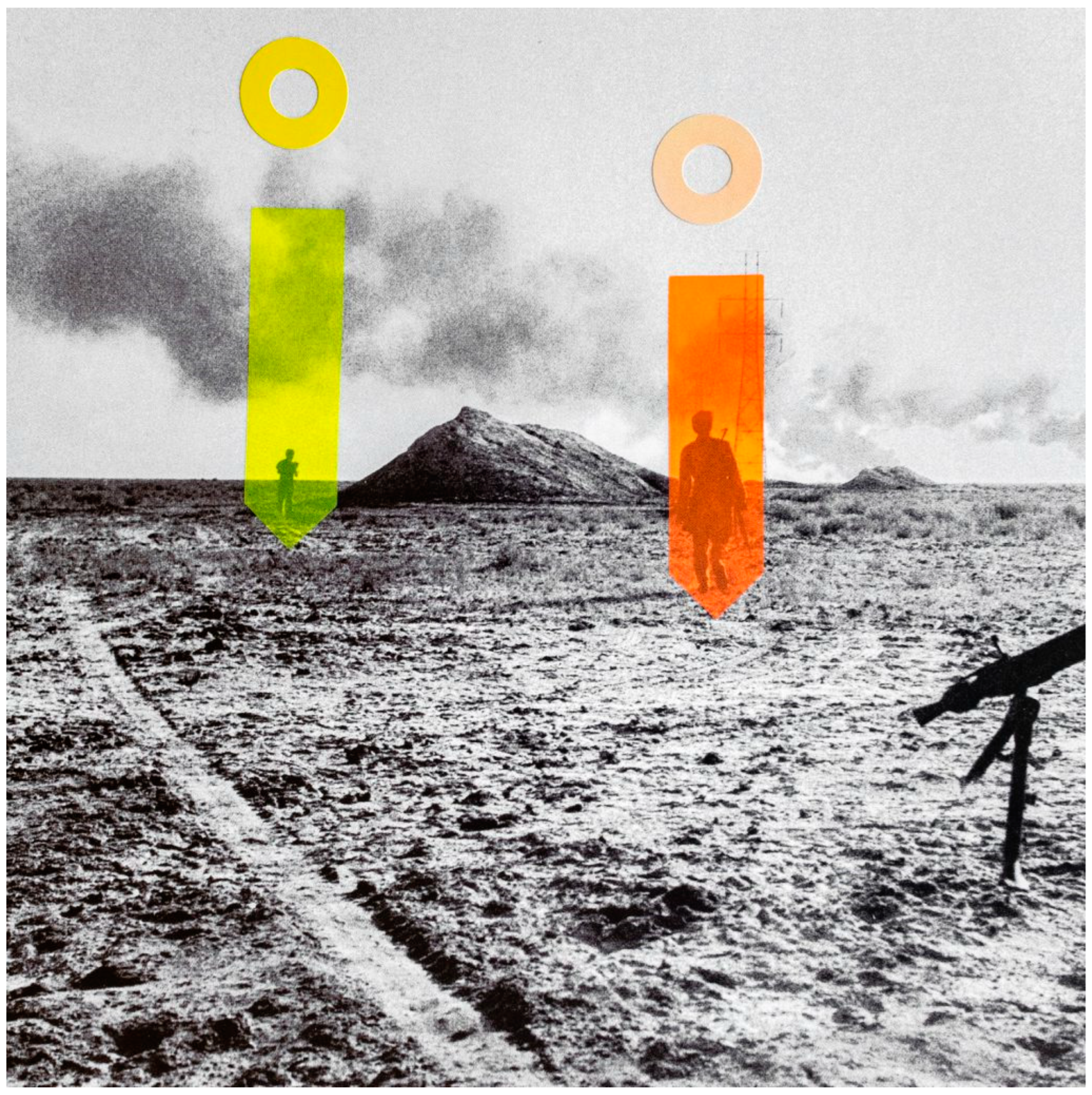

Asymmetrical Authority refers to the post-revolutionary discussion on ‘official’ historiography as an unresolved problematic filled with political ideology. The series depicts how photographic images can mobilise critical historiographical exploration. Through the act of reproduction, Taghioff adapts the black and white ‘documented’ photographic depiction of definitive political events such as the 1978–1979 Revolution and the Iran–Iraq war (1980–1988) in these photographic collages. The sources of these images are documentary photographs such as the archival news images of the revolution or the war that have been published in books, mainly through governmental channels. Based on their nature, these books aim to serve ideological stories and reproduce hegemonic accounts of history. It is not surprising that in line with ideological trajectory of the Islamic Republic, this narration should be persuasive and promotive, meaning to portray a propagandistic account of the events—in particular the revolution and the war, which was named defāʽ-e moghaddas (the ‘holy defence’), or other related events such as occupation of the US Embassy in Tehran by a group of revolutionary university students in 1979 (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).12

Figure 4.

Parham Taghioff, From the Asymmetrical Authority series, 2018, photographs, HD inkjet print on archival acid-free paper, 50 × 50 cm.

Figure 5.

Parham Taghioff, From the Asymmetrical Authority series, 2018, photographs, HD inkjet print on archival acid-free paper, 50 × 50 cm.

Figure 6.

Parham Taghioff, From the Asymmetrical Authority series, 2018, photographs, HD inkjet print on archival acid-free paper, 50 × 50 cm.

Taghioff considers himself as an author who plays with the documented history of the earlier generations’ struggles (Sumac Space 2021). He maintains,

I decided to take on the role of an author for this project so that I could revise history, confront it and even intervene in it by identifying new strains in reaction to the circumstances at hand. …I have employed the self-perpetuating organic system based on my historically lived experience to create new personal narratives and contexts which are somehow based on historical memories.(Taghioff 2023)

Taghioff deconstructs the visual narrative by concealing the identity of events and protagonists in these photographs. He deforms the documentary photos by folding the images, cutting some parts, covering such significant features of bodies as heads in photographs by juxtaposing coloured papers of blue, red, yellow, pink and so on with them or using digital touches—corresponding to the act of censorship, the common practice by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. Here, the absence of those figures, bodies or elements generates as much meaning as their presence. By de-familiarising the scenes, the artist becomes involved in the act of subvention so as to challenge the hegemonic narratives through these documentary photographs. A familiar viewer with these typical scenes is automatically challenged by these manipulated images that offer re-conceptualised and re-contextualised versions of mainstream accounts of history produced through official propaganda. These ‘(de)constructed’, yet enigmatic, histories invite the viewers to imagine their own accounts in order to make new narrations out of them.

As the title Asymmetrical Authority13 suggests, the central theme is the conflict between prescribed forms of authority and a democratic one. This series clearly acknowledges the fact that there is no single story, no coherent narrative, no single viewpoint in narrating history. The images obliterate any sense of temporal continuity or narrative integration, erasing what enables us in the future to understand our present as a meaningful past (Koepnick 2004).14 The Asymmetrical Authority series suggests what has happened in the past is not in the past and unchangeable, that every historical examination can show a different image of the past and, as a result, the past, the present and the future are reconfigured anew.

Haunted by obscured recollections, Taghioff learns how to use the entries of his pictorial narration in order to reconstruct not only what might have happened but something that has happened. These images also suggest the gaps between the representation of the past and the objectivity of the actual past event to recover what was lost to the artist. By emphasising their own status as post-memories, images of the Asymmetrical Authority series catalyse forms of memory that make the viewer feel different from the kind of history whose symptomatic presence in the present is traced in these images (Koepnick 2004) What could possibly be more politically impactful than to understand and unpack the present for what it is and for all that it is? The artist selects a strategic political line to address the possibilities, hopes and desires that were once—and are no longer—available to the Iranian nation: suppressed dreams and lost moments.

3. Mohammad Ghazali’s Persepolis: 2560–2580 (2021)

The work of Mohammad Ghazali (b. 1980, lives and works in Tehran) offers a different take on hauntology. For Ghazali, photography refines the boundaries between visible and invisible. His approach to photography often exposes the intensely subversive and enigmatic aspects of the ordinary and mundane, (Daneshvari 2016) while questioning the ideologically constructed truth formulated by the local political system. His work interrogates the status of the image’s past and present and challenges its reliability as a source of history. Challenging our conventional trust in photographic documents, his work urges us to question why and how we come to encounter photographs as authenticating media of history and memory. He maintains,

I believe all photographic images generally speak about the past, as when we see a photograph, we automatically relate it to the past. [In my photographs] my choice of themes inevitably leads me to become involved in historiography of my time.15

Ghazali’s photographic practice seems to reveal an absence which is voiced around the fact that his photographs carry something mysterious. Although they are about his immediate lived experience, his works take us to unpredicted and often questionable viewpoints where we are invited to stand in a place outside reality. He himself maintains that his work is concerned with the question of relationships between author/creator, spectator and viewpoints.16 His misleadingly simple photographs that move between visual storytelling and reality encourage the viewer to be an active agent in creating and discovering the latent message obscured in the images. Their titles somehow generate the sense that they do not cohere with what they might actually tell us. For example, in one of his earlier projects Where the Heads of the Renowned Rest (2011), the mysterious titles of works, each named after a prominent historical (and contemporary) figure such as Ferdowsi, Saʽadi Reza Abbasi and Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, are perceived only when we realise that the modern scenes of the cities in photographs are taken from the perspective of their tombs, monuments or streets named after them. As Abbas Daneshvari maintains, these icons ‘represent the fixed metaphysical structures of Iran’s adopted socio-religious Truth’ (Daneshvari 2016, pp. 3–4). However, the truth associated with these icons is undermined and overturned when we see the world from the eyes of the photographer. Here, Ghazali questions the officially formulated ‘truth’. We are compelled to assume that these works ‘are translations of the metaphysical games in language and no more, and … are the unconcealment of such games’ (ibid., p. 4). This way, by blurring the boundaries of time and space, Ghazali’s work not only represents a denotation of the past but also objects of the present.

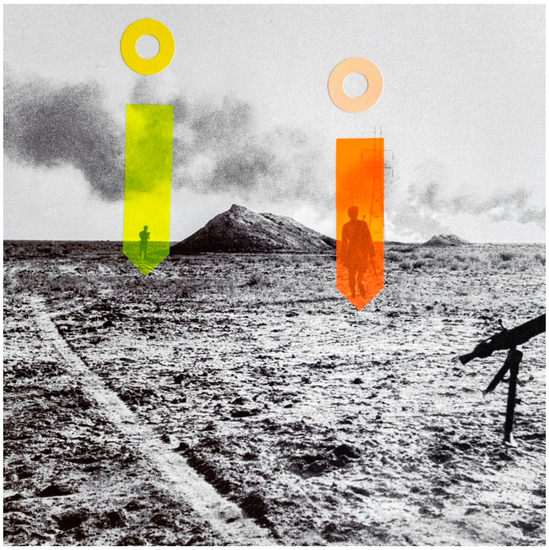

The Persepolis: 2560–2580 series (2021)17 is similarly situated at the edge between objectivity and subjectivity, history and memory. Providing objective accounts of a false historical narrative, the photographs in this series reveal the impossibility of a purely truthful narration. They portray the possibilities of writing the artist’s own history and inscribing it in a collective context. This work is anchored in how elements of history—to which architectural elements belong—could move and circulate in the present day, against the background of a history haunted by doubtful events.

Persepolis: 2560–2580 consists of a collection of thirty-eight small monochromatic images18 mounted together on the wall to make a unified set, along with documentation used to emphasise their authenticity (Figure 7 and Figure 8).19 In the brochure of the exhibition, there are meticulous informative historical materials about ancient inhabitants of Persia, the construction of the palace of Persepolis including its architectural features, structural and decorative elements such as gates and motifs, etc. The photographs pretend to be the actual documentary of the construction of the ancient capital city of the Achaemenid Empire, Persepolis.

Figure 7.

Mohammad Ghazali, from the Persepolis 2560–2580 series, installation view, Ab-anbar Gallery, London 2021.

Figure 8.

Mohammad Ghazali, from the Persepolis 2560–2580 series, installation view, Ab-anbar Gallery, London 2021.

The dates (2560–2580) refer to the solar calendar and the coronation of Cyrus the Great, the first Achaemenid king in 559 B.C. They are in fact related to the years between the time when Ghazali took the photos first in 2001 and when the images were exhibited in 2021 (from the initial idea to materialisation of the project). The photos are a sequence of images taken from the actual construction sites of the Hakim Expressway in Tehran, one of several that have been built in the metropolis during the past decades. These photographs that are similar to archaeological sites deceptively create an imaginary vision of what might have taken place on the original construction site (Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11). They act as indexical representations of the real. However, the doubt starts when the viewer is confronted with scenes devoid of any physical markers of memory. The enigmatic nature of portraying this construction corresponds with the site’s lack of visual appeal and absence of identifiable indications. The viewer is then left with an enigma of how the pictures of the pipes, girders and metal ropes they see correspond to the historical documents provided by the artist. These images appear quiet, but their uncanny silence stimulates the viewer’s critical thinking and the need to connect with some specific extra-pictorial information, be it historical or cultural. Here, Ghazali challenges the concept of authenticity, authentication and ‘true’ documentation. It seems Persepolis: 2560–2580 fuses a point in ancient history with now, linking two architectural structures across the fissures of spatial and temporal dislocation in a process of history making.

Figure 9.

Mohammad Ghazali, from the Persepolis 2560–2580 series, Lost no. 017, 2001–2021, Analog photography, gelatine silver print, 13.5 × 20.5 cm.

Figure 10.

Mohammad Ghazali, from the Persepolis 2560–2580 series, Lost no. 023, 2001–2021, Analog photography, gelatine silver print, 13.5 × 20.5 cm.

Figure 11.

Mohammad Ghazali, from the Persepolis 2560–2580 series, Lost no. 024, 2001–2021, Analog photography, gelatine silver print, 13.5 × 20.5 cm.

Ghazali himself remarks,

I tried to mislead the audience with a lie, pretending that the photos were the visual documentary of the construction of Persepolis. The lie was emphasised by the performative act of presenting the viewers with documented information in the brochure of the exhibition.20

Although, as Allan Sekula argues, the camera serves to ideologically naturalise the eye of the observer, the same picture can express a variety of messages under varying contexts. Therefore, documentary photography is believed to be art when it transcends its reference to the world, when the work above all can be considered as the artist’s self-expression (Sekula 1978). Similar to what Mark Ryan Westmoreland describes about experimental documentary in post-war Lebanon, the documentary photographs presented in the Persepolis: 2560–2580 series are not ‘records of the real, but casings, hollow shells, empty remnants of remembering’ (Ryan Westmoreland 2011, pp. 12–13).Ghazali’s photographs intend to trigger doubt and to encourage the viewer to question what they suppose they see and how they wish to perceive and interpret the images. His photographic reference is concerned with disrupting temporal continuity and thus ‘draw our awareness to the many ghosts that populate our own present’ (Barthes 1981, pp. 88–89). According to Lutz Koepnick, ‘in converting the past into spectre haunting the future, the photographic image can also stimulate a curious solidarity between the dead and the living’ (Koepnick 2004, p. 99). Ghazali similarly seeks to stimulate the question of how past is haunting the present. This way his work creates scepticism and challenge the truth by drawing the viewers’ attention to the exiting political manipulation involved in the construction of official narratives of history and truth.

Landscape as an aesthetic form is typically recognised as a form that can encode historical and ideological specificities. W. J. T. Mitchell links landscape and power, asserting this interconnection between the representation of space, place and its historical narrative and actions (Mitchell 2002). Persepolis: 2560–2580, too, addresses the process by which a historical artifact becomes a national symbol. Some of the issues involved in the discourse on the making of symbols touch upon the choice of the symbol, its appropriation and marketing to the masses as such (Merhavy 2019). Ghazali invites us to inquire into these issues specifically with respect to Persepolis, the site that came to be the Pahlavi state’s most notable, yet controversial, representative of nationalist policy and what that was later challenged by the Islamic Republic’s anti-monarchy historical narrative. Ghazali’s documentary art then disrupts the authoritative historiography and the state’s refusal to bear any alternative accounts to its ideological formulation.

In his statement, Ghazali refers to 1984, George Orwell’s dystopian social science fiction, to emphasise the importance of history making: ‘whoever controls the past can control the future and whoever controls the present can control the past. …(if) we control all memories. Then we control the past, do we not?’ (Ghazali 2021; Bailey 2021).

4. Conclusions

Through examination of the works of the artists, we saw how they have represented their versions of histories through strategies of reassessment and reimagination of the past. Here, by referencing the past, artists do not seek to tell the story of an ‘objectified past’ but situate themselves in the position of being the subject of that history which they are subjectively living in. Through a variety of approaches, they insist on the inviolability of an ideologically constructed history—formulated by the Iranian political system—which normally acts against creative understanding of the past, since ideology itself inevitably demolishes historical perspectives in favour of an abstract ideal. Furthermore, artists are involved in the debate of historical accounts by challenging and addressing current political affairs in their country and, in turn, shaping their own truth. They apply visual strategies to reclaim authority over their own individuality as opposed to the dictated one by the ideology of the Iranian state.

The two artists whose works were examined in this article have not been directly engaged in judgements per se. However, a sense of negotiation might appear in particular from the fact that they refuse to allow invisibility to persevere and obscurity to remain. Their practice of evacuating time and history largely indicates their endeavour to displace the real and change the viewer’s perception of the historical past and fuse it with the present. Taghioff’s photographic images seem haunted by a certain uncanny and therefore resist conventional visual representations. This characteristic allows the artist to display a crisis of representation and memory in Iran and to find a way of transcending these traumatic events and permanent sense of instability. His photographic images in the Asymmetrical Authority series, furthermore, are attempts to address the legacy of a past veiled by threat of censorship and political arrest. Ghazali’s Persepolis: 2560–2580 series, in a similar vein, criticises histories that have been written by the victors (Bailey 2021) and are often assumed as truth. They, however, can be explained as ideologically fabricated stories. The artist’s practice goes against the political will either to forget or to restore specific histories and cultural memories. His work allows us to regain a sense for the random nature of historical narratives and their shifting perceptions. What these artists have in common is that the inevitable ambiguity of the past constantly escapes them, leaving them in their haunted contemporary present. Thus, their works epitomise how memories of the past haunt the present.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term hauntology is a neologism first introduced by French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his 1993 book Specters of Marx. For Derrida, hauntology is a philosophy of history that challenges the easy progression of time by suggesting that the present is simultaneously haunted by the past and the future (Derrida 1994). Derrida’s earlier work on deconstruction, in particular on concepts of trace and différance, provides the foundation of his formulation of hauntology, fundamentally stating that there is no temporal point of pure origin but only an ‘always-already absent present’ (Derrida 1970, p. 254). |

| 2 | It basically refers to the very experience of everyday life which is built around a process that is called hauntogenic, and whose major by-product is a steady stream of ghosts (Rahimi 2021, p. 3). |

| 3 | The enterprises were to be fulfilled by cultural planning and organisation, including the establishment of several cultural centres relating to the revival of ancient Iran’s grandeurs. Some of these enterprises consisted of approbation of a law respecting the preservation of historical antiquities in 1930, the establishment of the Iran-e Bāstān (Ancient Iran) Museum in 1937, the National Library of Iran in 1939, both in Tehran, and the Pars Museum in Shiraz in 1936. |

| 4 | During the past few years, a great number of people have gathered at the tomb of Cyrus the Great in south-central Iran. There, they celebrate the unofficial annual holiday that honours him. In particular, in October 2016 thousands of people from all around the country attended the ceremony. Unsurprisingly, the state did not tolerate this and since then has blocked all the roadways to the tomb during this occasion to stop the annual gatherings. |

| 5 | For examination of the concept of cultural authenticity and its definition by the Iranian state, as well as artistic resistance, see the author’s articles, (Keshmirshekan 2013, 2015). |

| 6 | The ministry was established in 1979 and first named Ministry of National Guidance (Vezārat-e ershād-e melli) and then in 1980 changed to Ministry of Islamic Guidance (Vezārat-e ershād-e eslāmi) and finally in 1987 it renamed to the current title, Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance (Vezārat-e farhang va ershād-e eslāmi). |

| 7 | It was only briefly during the so-called Reform period (1997–2005) when the reformists eased censorship, granting licenses to new publications and other cultural activities and productions. |

| 8 | In 1988, acting on the orders of Ayatollah Khomeini (1902–1989), state authorities executed thousands of political prisoners across the country quite rapidly and extrajudicially. According to estimations from former state officials and lists compiled by human rights and opposition groups, between 2800 and 5000 prisoners in about 32 cities in the country were executed. |

| 9 | It refers to the mass murder of intellectuals, the so-called chain murders (Qatl-hā-ye zangireh-i), of the 1990s in Iran. The chain murders were a series of murders and disappearances of certain Iranian intellectuals who had been critical of the Islamic Republic system and appeared to be linked to each other. The victims included more than eighty writers, poets, translators and political activists. |

| 10 | For the exploration of the concept of exoticism and contemporary Iranian art see the author’s article, (Keshmirshekan 2010). |

| 11 | For analysis of the politics and aesthetics of photographs and memories, see (Koepnick 2004). |

| 12 | In November 1979, a group of Iranian revolutionary college students, later named Muslim Student Followers of the Imam’s Line, took over the US Embassy in Tehran and seized as hostages fifty-two US diplomats and citizens. After Khomeini’s supporting statement, in revolutionary terminology, the Embassy was called ‘American spy den’ (Lāneh-ye jāsusi-ye āmrikā) while in the West it was known as the Hostage Crisis. The hostages were held for 444 days until January 1981 when they were released after the outcome of the American Presidential Election with the victory of Republican Ronald Reagan. |

| 13 | Taghioff is inspired by Lutz Koepnick’s argument about how to place certain ima ges in larger narratives of history and memory. Koepnick maintains, ‘…how we engage older myths of reference, objectivity, and truth in order to define the relationships between image-makers, photographic subjects, and viewers as relationships of either asymmetrical authority or mutual recognition’ (Koepnick 2004, p. 102). |

| 14 | For exploration of the issue of cultural repression and forgetting memories within the complex conditions in Sarajevo and Beirut, see (de le Court 2020). |

| 15 | Interview with the author, December 2022–January 2023. |

| 16 | Ibid. |

| 17 | In my interview with the artist, he stated that this series is a part of a trinary project. The other two are entitled Green House and Stone (Sangāreh). Interview with the author, December 2022–January 2023. |

| 18 | Ghazali wrote to me that the actual number of photos was in fact 250 and it was only possible for a small portion to be exhibited. |

| 19 | A stimulating example of this approach can be found in Walid Raad’s projects under the fictional Atlas Group (1989–2004). These projects consisted of found and produced audio, visual and literary documents that shed light on the contemporary history of Lebanon, with particular emphasis on the Lebanese civil wars of 1975 to 1990. The documentary material that the Atlas Group presented as ‘archival’ materials was of dubious provenance, sourced to anonymous individuals or characters of questionable authenticity. Even when they were attributed to Raad himself, the documents freely combine fact and fiction in a way that suggests the highly subjective and contested nature of historical memory. Raad suggests that ‘the Atlas Group’s documents do not mimic reality, because that reality is itself suspect. What we have come to believe is true is not consistent with what’s available to the senses. If truth is not what’s available to the senses, if truth is not consistent with rationality, then truth is not equivalent to discourse’ (Wilson-Goldie 2004). |

| 20 | Interview with the author, December 2022–January 2023. |

References

- Bailey, Celia. 2021. A review of Mohammad Ghazali: Persepolis: 2560–2580. The London Magazine. Available online: https://thelondonmagazine.org/review-mohammad-ghazali-persepolis-2560-2580-by-celia-bailey/ (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Bal, Mieke. 2010. Of What One Cannot Speak: Doris Salcedo’s Political Aer. Chicago: Chicago University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, pp. 88–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cottam, Richard W. 1979. Nationalism in Iran. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvari, Abbas. 2016. The Aleatory Nature of Being, The Art of Mohammad Ghazali. In Contemporary Iranian Photography, Five Perspectives. Edited by Abbas Daneshvari. Costa Mesa: Mazda. [Google Scholar]

- de le Court, Isabelle. 2020. Post-traumatic Art in the City, Between War and Cultural Memory in Sarajevo and Beirut. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1970. Structure, Sign and Play in The Discourse of Human Science. In The Structuralist Controversy, The Languages of Criticism and The Sciences of Man. Edited by Richard Macsey and Eugenio Donato. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. Translated by P. Kamuf. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Farhi, Farideh. 2004. Cultural Policies in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Paper presented at the Conference Iran after 25 Years of Revolution: A Retrospective and a Look Ahead, Washington, DC, USA, November 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Mark. 2013. The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology. Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, Mohammad. 2021. Persepolis: 2560–2580. Brochure of the Exhibition. London: Ab-anbar Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Haghayeghi, Mehrdad. 1993. Politics and Ideology in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Middle Eastern Studies 29: 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmirshekan, Hamid. 2010. The Question of Identity vis-á-vis Exoticism in Contemporary Iranian Art. Iranian Studies 43: 489–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmirshekan, Hamid. 2013. Reclaiming Cultural Space: Artist’s Performativity versus State’s Expectations in Contemporary Iran’. In Performing the Iranian State: Cultural Representations of Identity and Nation. Edited by Staci Gem Scheiwiller. London and New York: Anthem, pp. 145–55. [Google Scholar]

- Keshmirshekan, Hamid. 2015. The Crisis of Belonging, On the Politics of Art Practice in Contemporary Iran. In Contemporary Art from the Middle East. Regional Interactions with Global Art Discourses. Edited by Hamid Keshmirshekan. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, pp. 109–34. [Google Scholar]

- King, Preston. 2000. Thinking Past a Problem: Essays in the History of Ideas. London: Frank Cass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Koepnick, Lutz. 2004. Photographs and Memories. South Central Review 21: 94–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, John. 2008. Putting Man Before Descartes, Human Knowledge Is Personal and Participant—Placing Us at the Center of the Universe. The American Scholar. December 1. Available online: https://theamericanscholar.org/putting-man-before-descartes/ (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Merhavy, Menahem. 2019. National Symbols in Modern Iran: Identity, Ethnicity, and Collective Memory. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William John Thomas, ed. 2002. Landscape and Power. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Ludwig. 1999. “Iranian Nation” and Iranian-Islamic Revolutionary Ideology. Die Welt des Islams 39: 183–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, Sadeq. 2021. The Hauntology of Everyday Life. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Westmoreland, Mark. 2011. Crisis of Representation: Experimental Documentary in Postwar Lebanon. Charleston: Proquest, Umi Dissertation Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sekula, Allan. 1978. Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on Politics of Representation). The Massachusetts Review 19: 859–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sumac Space. 2021. History/Image: National Memory Beyond Nationalism—A Conversation between Iranian Photographer Parham Taghioff and Milad Odabaei. Available online: https://sumac.space/dialogues/history-image-national-memory-beyond-nationalism/ (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Taghioff, Parham. 2023. A Conversation between Parham Taghioff and Hamidreza Karami. Routledge Journal of Visual Art Practice 22. special issue on contemporary art of Iran (forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley, Sheila, and Shara Rambarran. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Goldie, Kaelen. 2004. Walid Raad and the Atlas Group, Bidoun. Available online: https://www.bidoun.org/articles/walid-raad-and-the-atlas-group/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).