Abstract

The rise of Egyptian women artists and art teachers at the end of the 1940s appeared in tandem with an active women’s movement that asserted the agency of women in modern Egyptian public life. In this article, we discuss the art career of Menhat Helmy (1925–2004), a 1949 arts graduate of the ma`had al-ali li-ma`lumat al-funun al-jamila (Higher Institute for Women Teachers of the Fine Arts), located in the working-class district of Bulaq in Cairo, and who was among the first Egyptian graduates of the Slade School of Art in London. In a series of etchings executed from around 1956 and through the 1960s, Helmy produced a visual commentary on the dignity of Bulaq’s residents, with emphasis on the active presence of women in its neighborhood and public spaces. Helmy may be viewed in context with the feminism of her fellow women artists, including Gazbia Sirry (1925–2021) and Inji Efflatoun (1924–1986), and in relation to Efflatoun’s two books on feminist causes. As new professional artists and teachers, they advocated the promotion of education and vocational choice for women. Helmy’s choice of this neighborhood as a subject for art allows a comparison to theories about Bulaq’s development and its locus for the arts for which a multidisciplinary approach is required.

1. Introduction: Egyptian Women Artists and the Role of Education

“Institutes of art education should not turn into machines to produce teachers, but rather become institutes for developing and discovering talents and working on creating the artist first and then the teacher second.

Menhat Helmy (circa 1963–1966)1“A woman kept at home is isolated from art and cultural trends. Art and the artist come first, for art does not distinguish between the sexes”Menhat Helmy(Al-Ahram 1978)

By 1949, a small group of women graduates and art teachers were emerging from the ma`had al-ali li-ma`lumat al-funun al-jamila or Higher Institute for Women Teachers in the Fine Arts (hereafter, HIWT) in Bulaq. These included the new graduates Menhat Helmy (1925–2004), and Gazbia Sirry (1925–2021). In 1952, Zeinab Abdel Hamid, a graduate of a Spanish art academy, began employment as an art teacher at the same institute. Each of these three women are recognized today as among the more prominent artists of a generation of women artists whose careers emerged in the 1950s (Madkour 1991)2. This article considers the early career of Helmy and importance of the institution, and its original locale in Bulaq, a working class district of Cairo. The relation between artist, teacher, school and its community is demonstrated in the choice of Menhat Helmy to return to Bulaq and make it a major subject of her etchings, even after the school had been closed in 1957, when it was reorganized into another teacher’s college in the affluent neighborhood of Zamalek. In the same year that Helmy and Sirry were graduating as newly qualified teachers with diplomas in art education, Inji Efflatoun, a fellow artist, turned journalist, had taken up the very question of the role of education and need for women teachers, including in the arts.

In her 1949 book nahnu al-nisa’i al-misriyya (We the Egyptian Women), Inji Efflatoun, wrote a manifesto for Egyptian women’s causes (Efflatoun 1949)3. Appearing in the same year as Simone de Beauvoir’s Le Deuxième Sexe that was published in Paris, Efflatoun’s book was written independently, for there are no references to Beauvoir. Rather this new book published in Cairo was a product of Efflatoun’s engagement with Egyptian feminist discourse, journalism and activism and reflected the place of Egyptian women from the Global South. She launched an attack against the customs, laws, and traditions of the Egyptian ruling patriarchy. The book made persuasive arguments against Egyptian marriage laws that discriminated against women in criminal and divorce courts and through the legalization of polygamy. It followed the publication of another book she had written the prior year thamānūn milyūn imraʼa ma`na (80 Million Women are with us) in which she reported on her participation at women’s conferences in Paris, Prague and in Cairo (Efflatoun 1948). As a young artist while still a student at the French lycée in Cairo’s Zamalek district, Efflatoun had exhibited provocative paintings at the 1942 Art et Liberté exhibition in Cairo (Bardaouil and Fellrath 2016). By the late 1940s however, Efflatoun had abandoned art in favor of journalism and sought an advocacy of women’s causes through the writing of newspaper opinion columns and these books. The impact and lasting resonance of Efflatoun’s writing on other women of her generation was attested by Soraya Shakir at a conference on women’s history (Shākir et al. 2002). In a chapter on education for Egyptian women Efflatoun provided the following rationale.

But the traditions that still dominate the patriarchal mentality of their fathers stood as a barrier between the girl and this kind of education. These traditions along with other factors—whose explanation will fall into place—enabled them to deprive the Egyptian girl of social progress, and instead limited her to only a primary education or a women’s education that was limited to home management or similar.(Efflatoun 1949, p. 6)

Efflatoun critiqued the impact of British colonial policy after the 1882 occupation that she blamed for reducing the number of primary schools for girls in Egypt. It was only during the 20 year period 1925–1945, after Egyptians resumed control of public schools that the percentage of women students in primary school had more than doubled. Despite this, illiteracy in Egypt was still estimated to be around 80%. Even more startling was the illiteracy rate among women.

As for the situation of Egyptian women today in the field of education, we must confront official statistics that reveal painful truths. This is reflected in the fact that women represent no more than a trivial 2% out of the total of 20% of the population who are educated, meaning that the illiteracy rate among women is 96% and among men is 64%.(Efflatoun 1949, p. 35)

Efflatoun also critiqued the recent changes in education policy that pushed privatization of schools. The turn to privatization, Efflatoun noted had been begun by the British colonial policies that removed free tuition. While Egyptian women were finally gaining access to universities, the effect on women’s access to higher education in the arts was found in the following directives.

Abolishing the free tuition enjoyed by female university students—especially in the Faculty of Arts—this cancellation was enacted in 1946 and prevented the Egyptian girl from being encouraged to enter universities, and kept the number of female students, at only 7% of the total number of students.(Efflatoun 1949, p. 37)

Efflatoun noted the Ministry of Education’s failure to address the shortage of women teachers (Efflatoun 1949, p. 52). Efflatoun, who openly admitted her privilege as a member of the large landowning class, construed the reasons for keeping women illiterate were inferred in census statistics. There was a rise between 1927 and 1937 in the number of women agrarian workers from 523,000 to 703,000 (Efflatoun 1949, p. 44). In fact, the crisis in rural education had been raised in a separate government report (Report of the Committee of Education 1946). Around the same time, these issues had prompted the direct attention and responses of Hassan Al-Banna, himself a graduate of a teacher’s college, and his organization, the Muslim Brothers, who acting as an informal shadow government yet unsupportive of women’s issues, issued their own reports on education and the peasant economy in rural Egypt (Kane 2017, pp. 173–77). Efflatoun also argued that marriage customs and employment policies limited women’s professional development. The 1937 census showed that “women have taken a hit in public services.” There was only a marginal increase in the same period from 14,965 to 16,068 employed in public services. Of these there were only 4000 teachers who upon marriage saw their salary reduced, with only a three-week maternity leave with no pay. Despite these restrictions, she argued nothing prevents an Egyptian woman from working as other women do in the sciences, literature, fine arts and in trade and industry (Efflatoun, p. 94). She provided the following rationale for the expanded role of women in education:

As for women in the fields of science, arts, and literature, the share of Egyptian women in these fields is truly an honorable one. The number of Egyptian University graduates, has increased, giving rise to optimism. Women turned a lot towards self-employment, practicing medicine, law, journalism, writing, and the arts. We find that the Egyptian woman has also occupied her place in the university education bodies, as in the Faculty of Education, which has a number of female teaching assistants, and the Faculty of Arts has a female teacher, but this is a rarity.(Efflatoun, p. 54)

Following Efflatoun’s lead, specific conditions and results of teacher education in the arts may be examined. In the following section we follow Menhat Helmy’s trajectory into art teaching and her choice of subjects centered in Cairo and Egypt between 1956 and 1969. Helmy’s experience and choice of subject is also worth comparing with the artist who most closely shared her experience as a graduate from the same teacher’s college, Gazbia Sirry. While Helmy would consciously locate much of art during this period to scenes of Bulaq and its surroundings, Sirry is also noteworthy for adopting subjects that were directly linked to Efflatoun’s book and the broader issues surrounding the women’s movement from 1949 through the 1950s. By 1957, both artists had produced art directed at women’s issues as a public cause, as seen for example in Helmy’s etching The Elections, that depicts women organizing for the first free elections and full suffrage for women in Egypt, that included women running for public office.

The articulation of an art history of modern Egyptian women artists has received renewed emphasis in the past decade, and build upon earlier efforts of earlier scholarship by Azar (1953), Madkour (1991), Mikdadi (1994), Naef (1996), Radwan (2016, 2017, 2021), Adal (2019), Ozpinar and Kelly (2020), and Atallah (2020). For scholars, the difficulty of finding and locating etchings by Helmy or the paintings by Sirry with such overt themes is notably overly dependent upon locating family members and personal archives of collections, documents or notes that have not been made public (Radwan 2021)4. Hence, most of these art works have not been previously known or able to be discussed in an open forum. A proposed solution that is only in its early stages is the new Al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art at NYU Abu Dhabi, under the auspices of Professor Salwa Mikdadi, which seeks to create a digital archive of family and privately held artist archives. Without a publicly available accessible database or open access museum collection to these artists, the development of a critical art history remains hindered when compared with poets, novelists, playwrights and other writers, whose works are better disseminated.

A theory of women artists and writers is needed to correlate the studies of Egyptian feminism with art history. Efflatoun attempted to link art and journalism at various phases of her career. Helmy’s own comments are limited to several short news articles and interviews. However, the field of Egyptian women’s history is more fully developed in historical studies, and in the literature than it is in art history. Several works that attempt to situate the feminist history of period of the 1940s to 1950s include a survey of the role of women journalists by (Moriscotti 2008) and the political rhetoric of the state toward women following the 1952 Egyptian officer’s coup, and more general overviews offered by (Badran 1995) and (Bier 2011).

2. Art Teachers as New Intellectuals—The Choice of Career and Subject

As a member of the first generation of professionally trained Egyptian women art teachers, Menhat Helmy’s career in teaching spanned a period of nearly 50 years. Her teaching began upon her return from London in 1955. After her marriage to the physician Abdulghaffar Khallaf in 1957, she resumed her teaching as a working mother with an interruption when she relocated again to London between 1973–1979 where her husband was the medical attaché to the Egyptian embassy. The Egyptian press gave notice to the artist’s presence in London (Al-Akhbar al-Jum`a 1975) and her solo exhibition at the XVIII Gallery (XVIII Gallery 1978; Al-Ahram 1978); and to an exhibition of her new graphic design prints and etchings at an exhibition at the Goethe Institute of Cairo (1979) held upon her return to Egypt in October 1979 (Al-Akhbar 1979; Al-Katib 1979); and her exhibition in India as the representative from Egypt (Top Egyptian Artist undated). While ill health struck in the 1980s and limited her art production, her art was included in a London art exhibit on Contemporary Arab Graphics at the Graffiti gallery in London (Joyce 1982; Arabia 1982) and she nevertheless continued teaching art as a faculty member at Helwan University’s Faculty of Art up until her death in 2004.

After graduating from the Higher Institute for Women Teachers of Art in Bulaq in 1948, Menhat Helmy remained another year to receive a diploma in teaching. Helmy was also the first Egyptian, aided by a government scholarship, to attend and graduate from the Slade College of Art in London (1952–1955)5. During the First World War, Amy Nimr (1898–1974) another woman Egyptian artist, had also attended the Slade but at her own expense (Atallah 2018). At Slade, Helmy received honors and a competition award for etching in 1955. Throughout her career she was distinguished as both a graphic artist and painter, exhibited internationally and was given the rank of honorary professor at the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence, as well as a professorship in art at the Faculty of Arts at Helwan University, based at the College of Fine Arts in Zamalek. While her international reputation was well established at the Ljubljana Biennales from the early 1960s, she continued to exhibit internationally in group and solo exhibitions in Latin America, Japan in both Eastern and Western Europe, as well as in Egypt. Her later art career, from the 1970s onwards, shows a remarkable turn toward painting, design and abstraction and an attention toward the application of science and art, that distinguished her among her Egyptian peers, while Ramses Younan by the early 1960s had also shown an interest in studies of geology in his abstract paintings

Helmy’s formation as an art teacher as well as painter and graphic artist was established by the 1950s. It is from the 1950s and 1960s that her etchings and graphic works most directly comment upon the social scenes and life of Cairo, as well as some scenes of rural Egypt. Many of these featured in the 1966 Akhenaton Gallery solo exhibition in Cairo, including some of English landscapes and scenes of nature that she completed during her Slade years. Both the exhibtion catalogue and the art critic Hussayn Bikar listed and noted a total of 55 etchings (Bikar 1966). That show encapsulated the scope and range of subjects, from both her London student days and her return to Egypt. It is the focus on Egyptian women of the lower classes in this exhibition and up to this period that Helmy’s art most directly parallels that of other Egyptian women feminists and artists, most notably among these, Inji Efflatoun, who in her paintings had focused largely on the Egyptian peasant women, (Kane and Mikdadi 2022)6. Unlike Efflatoun, she avoided a public association with political parties, and yet her artwork of this period is a direct comment upon the social life and conditions of the working poor and women in the environs of her art school. Whereas Efflatoun’s turn to depicting scenes of rural Egyptian life and peasant women was a feature of her art during the 1950s, there were few scenes of urban life. One finds in Helmy’s renderings an assertion for a community of art and the vibrancy and resonance of the human subjects in their local milieu. If Helmy was apolitical in the formal sense of political party membership, she was certainly an advocate of women’s issues of public health, childcare and education as rendered in her etchings of this period. While her art is less polemical than her fellow art student Sirry, her etchings reflect the concurrent philosophies of a social philosophy of art already espoused in the Contemporary Art movement of the late 1940s to early 1950s, to which Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar was a principal representative and the Art and Social Life movement led by Hamed Said from the late 1940s, or Hamed Owais and the Group of Modern Art in the 1950s with its interest in social realism. Curiously, we have no apparent documentary evidence that Helmy was a part of or associated with either group of artists, despite her proximity as an art teacher in and around Bulaq and Zamalek where most of these artists gathered. How then do we explain Helmy’s rise as an art teacher?

In the 1930s male graduates and attendees at the men-only College of Fine Arts in Zamalek, were sent to various towns to teach art in primary and secondary schools under the initiative of Habib Gyorgy (Kane 2021). However, these initiatives were delayed for women, as the formal teaching of art for women teachers only began in the 1940s at a separate school in Bulaq. During the late 1930s, some instruction in drawing and the fine arts had begun at the women’s schools in Zamalek and in Bulaq, but this had not been organized into a course of matriculation for teachers. As a result, many of Helmy’s women contemporaries had chosen private paths into the visual arts, in the manner that Efflatoun alluded to in her 1949 book. Efflatoun remained an independent artist, who despite her privileged family background and excellent education at the Lyceé in Cairo, received studio training, and never formally attended college. While Efflatoun attended or undertook studio classes at or around the Faculty/College of Fine Arts in Zamalek, it remained a men only college through the 1940s.

Table 1 shows a chronology of the separate art academies or schools of art in the neighborhoods of Bulaq and Zamalek in Cairo at which men and women were studying between 1928 and the 1950s7. Figure 1 shows a photograph of students at the HIWT in Bulaq circa 1947–1949. Where the fine arts schools fulfill an ideological role for the Egyptian ruling class, the industrial applied arts have their own pedagogical history that conforms to the need to establish a working class. In Bulaq a school of arts and royal industries was established by Muhammad Ali in 1839. A separate set of applied art schools were also established, including the Khedival School of Arts and Crafts (1910) and reorganized and renamed several times: al-madrasa al-`ulya li-l-funun al-tatbiqiya (The Higher School of Applied Arts) (1941) and again in 1953 as the Kulliyat al-funun al-tatbiqiya (The Faculty of Applied Arts) (Shehab and Nawar 2020, p. 45). A fuller study of the history of these schools and the experience of women at the College of Fine Arts compared with these other institutions would be useful for scholars, including more on the curriculum and languages of instruction.

Table 1.

Art colleges in the Zamalek and Bulaq districts of Cairo circa 1928 to 1970s.

Figure 1.

Photograph of students at the Higher Institute Women Teachers of the Fine Arts in Bulaq circa 1947–1949, with Menhat Helmy seated at the far right with their art teacher, seated second from left; Menhat’s sister Reaya, also a student at the school is standing at the far left. The photograph may also be showing Gazbia Sirry. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

These images show the women students preparing sculptural models in clay or drawing still life from common objects displayed in the classroom. On Gazbia Sirry’s similar path into art teaching see the studies by Atallah (2017, 2019). She graduated in the same year in 1948 from the teacher’s institute in Bulaq, and may also have received a teaching diploma with an additional year of study.

In the family archives, are about 3 dozen drawings and watercolors of Helmy’s student work at the teacher’s institute. Executed between 1946 and 1949, these show the technical competence and variation in exercises and subjects undertaken by Helmy and her fellow students. Several watercolors by her sister Reaya also survive, who also graduated from the institute, excelled at sculpture and married the art critic Badr Al-Din Abu Ghazi, who later served as a Minister of Culture in the early 1970s. Black and white portraits of both men and women as seated subjects were executed in three-quarters pose and in profile and drawn in pencil or pastels. A series of watercolors or gouaches of still life interiors and a garden scene attest to the range of medium and subjects. Several preliminary sketches or under-drawings of seated women at work, and of Cairo’s markets or street scenes demonstrate a use of mise-en-scène arrangements of street life that would later feature in Helmy’s etchings in the 1950s and 1960s. We also find a variety of drawings of male and women subjects featured as full-length seated poses in the studio classrooms. A separate drawing exists of a nude portrait of a fragmented classical sculpture bust that appears in one or more of a series of black and white photographs of the school, its classrooms and school trips. Several watercolor portraits of semi-nude full-length portraits also exist that suggest these women students were comfortable with posing for each other within the privacy of the women only school. Given the anti-feminist strain in public Egyptian life against women’s freedom, these art works attest to the self-assertion of these young women artists and their teachers (Esanu 2018). In her introduction to her 1949 book, Efflatoun noted the threat of violent struggles against the activist Egyptian women’s movement. The achievements amid trying times of women art teachers is a valuable testament to the professionalism of the art school, and a full and competent portfolio that enabled Helmy’s admission into the Slade School of Art in London in 1952. Her sister Reaya Helmy, wrote a personal memoir for the 2005 retrospective exhibition catalogue about their early education and experience as students together in the 1940s at HIWT, where she named and noted the excellence of their women art instructors (Helmy 2005).

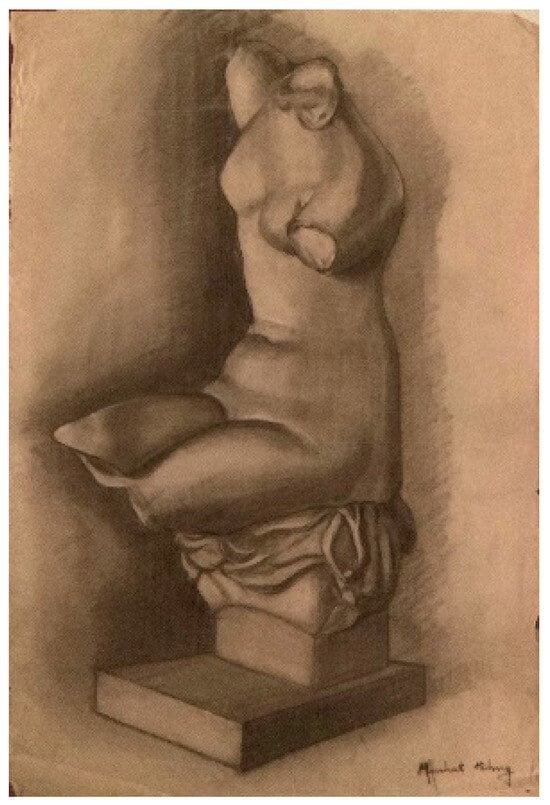

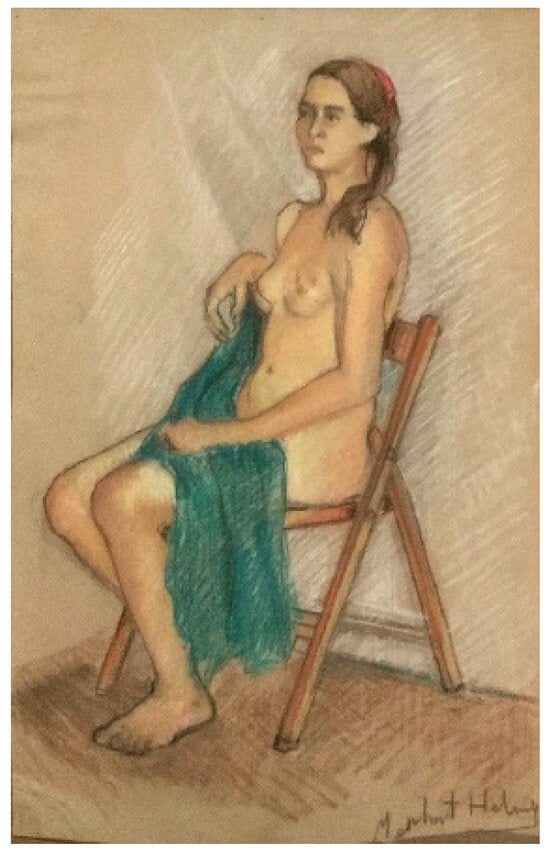

Examples of the use of nude portrait studies are found in these archives. In Figure 2 and Figure 3 (below), we find a progression in studies of the female nude, from a drawing based on a fixed sculptural bust found in the classroom studio to a live portrait of a semi-nude model seated in the same three-quarters portrait view. In Figure 4 we find a photograph from the studio sessions at the art school where similar casts are being created in clay during a sculpture class.

Figure 2.

Menhat Helmy, Portrait of Bust (1947–1949). Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

Figure 3.

Menhat Helmy, Untitled. Semi-Nude Portrait (1947–1949). Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

Figure 4.

Photo from Art School (1947–1949). Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

The young Helmy’s ambivalence towards a political rhetoric for art contrasts with that of her classmate, Gazbiyya Sirry. Sirry’s turn to art activism on behalf of the burgeoning women’s movement has only recently been elicited with articles detailing her sequence of politically themed art works from the late 1940s and continuing through the 1960s. An early series of Sirry’s paintings were dedicated to women’s political issues. These have come to light through reproduction of her 1949 painting Tahrir al-Mara’a (Women’s Liberation) that appeared in a short but revealing new review (Mostafa Kanafani 2021). Sirry’s 1952 painting, Umm Saber, is a tribute to a peasant woman killed by the British during protests and whose image was carried in protests on the streets by women marchers, led by Efflatoun among others. Assuredly, Sirry continued on this theme with a painting al-Zawjatan (The Two Wives; 1953) as a critique of polygamy. These new revelations and collections of Sirry’s paintings confirm that a number of women artists were joining a feminist movement that had organized itself around journalism. Altogether these paintings comment on the major issues of divorce law, polygamy and women’s status developed by Efflatoun in her book nahnu nisa’i al-misriyya (We the Egyptian Women) published in December 1949, and in Efflatoun’s opinion columns that appeared between 1949 and 1952 in various Egyptian newspapers, including Al-Masri. During these years, Sirry had studied painting in Paris during 1951, in Rome in 1952 and then attended the Slade School of Art circa 1954–1955 (Embassy of Egypt 1981, p. 34).

Another painting possibly made from around the time that Sirry was studying at the Slade, is dated 1954 and titled, L’Institutrice (The Teacher) (Sirri 1954). However, it was Helmy who taught art as a career choice, while Sirry was demonstrably more public in her political activism than Helmy. Her 1955 painting, Abbas Bridge has been described and reproduced in a short article by Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi as a commentary on the crushing of 1946 protests by students and workers against the repressive policies of the government then led by the Prime Minister, Mahmoud El Nokrashy (Al Qassemi 2020)8. Sirry’s own life parallels that of Inji Efflatoun as a direct consequence of having both their husbands imprisoned by the Nasser regime. Efflatoun’s husband died shortly after his release from prison in 1957, in circumstances that some Efflatoun family members believed was a brain hemorrhage caused by his beatings in prison by authorities. Efflatoun was imprisoned in 1959 in the same year that Sirry was herself jailed for several days and her husband imprisoned for several years by Nasser’s crackdown on leftists and communist party members. This difference between Sirry and Helmy may be explained in part by the latter’s own move to London in 1952, where she remained until graduating from the Slade School of Art in 1955. Helmy’s lack of party membership, meant that she was able to avoid this wave of imprisonment of artists and writers that prevailed throughout the Nasser period.

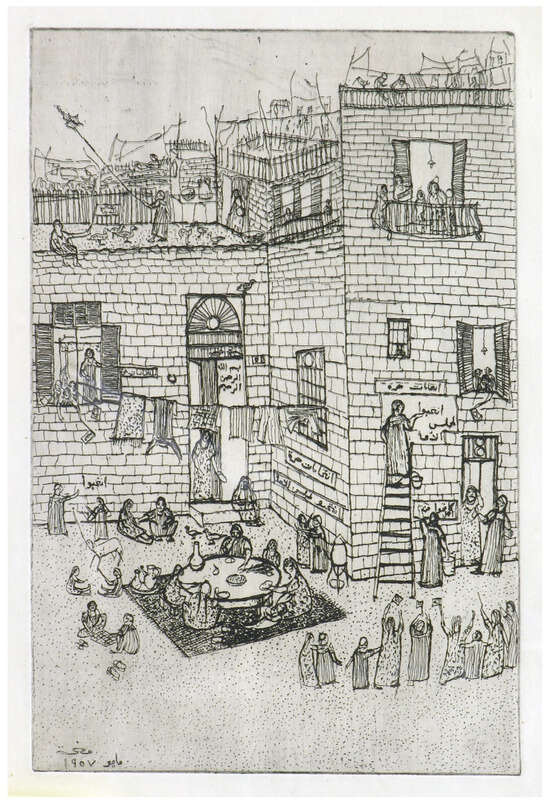

Nevertheless, her provocative etching The Elections (1957) (Figure 5) attests that Helmy was openly advocating Egyptian women’s political rights and women’s agency alongside her role as a teacher, and by the late 1950s, as a new mother. Helmy joined an open campaign for women to be elected in the first elections in 1957 when women were granted full suffrage and to stand for elected public office. Women are shown hanging banners announcing the first free elections. These initiatives led to the election of Shahinda Maqlad, the peasant labor organizer from Kamshish, who was elected the following year to the National Union as a representative for Manufiya Governate.

Figure 5.

Menhat Helmy, The Elections (1957). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

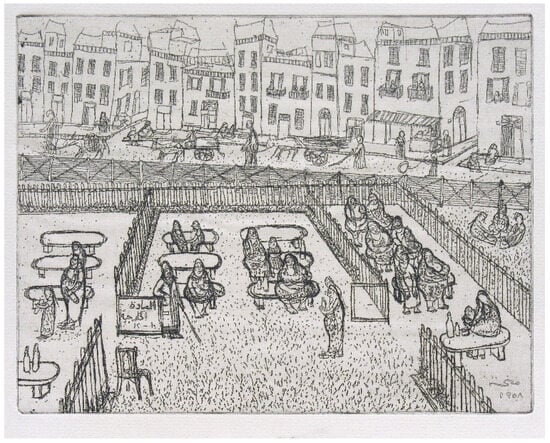

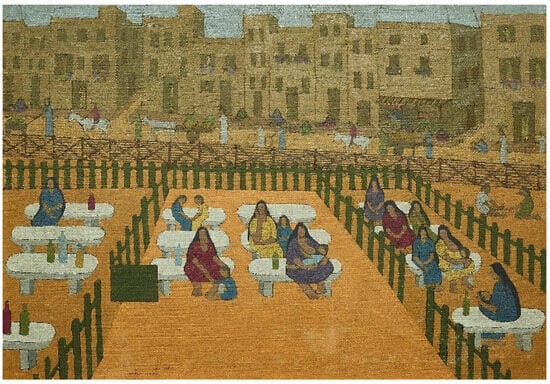

In 1958, it appears a directed campaign by these women toward women’s health was being raised. As a deliberate strategy, Egyptian women were not going to rest and be content merely with the right of suffrage, but they now openly advocated public health, and particularly the need for women’s clinics. A current exhibition at the Barjeel Art Foundation, Memory Sews Together Events that hadn’t Previously Met, has brought forth two remarkable paintings on this very subject of women’s and public health. One of these paintings, entitled Outpatient Clinic (1958), was by Menhat Helmy, and is likely a reworking of her etching of the same title.

The choice of the artist to depict the same scene twice, offer two narratives, once as an etching with details and features, including directional signs on the gates, and separately as color painting, that retains most of the characters but removes extraneous features and accentuates each character in pure and saturated colors. The painting’s style may be viewed as a tapestry, as the brushstrokes are textured in a thread-like weaving that run horizontally across the painting. Several nursing mothers in the Outpatient Clinic (1958) (Figure 6 and Figure 7) were shown again in the Circus 1961. As if to emphasize the safety and respect for the place of the nursing mothers, possibly the only adult male shown within the gated enclosures in the etching is elderly and walking with a cane and is possibly blind. By contrast, in the painting this sole male figure is removed, and the only men shown are beyond the gates along the street in the background.

Figure 6.

Menhat Helmy, Outpatient Clinic (1958). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

Figure 7.

Menhat Helmy, Outpatient Clinic (1958). Oil on canvas, 66 × 80 cm. Image, courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

The second painting on display at the Barjeel exhibition, and similarly entitled Clinic, (1958) (Figure 8) is by Mariam Abdel-Aleem, (1939–2010) also a distinguished graphic artist, and among the first women graduates in 1954 from the Zamalek based College of Fine Arts College, and whose career was recognized in Fathy Ahmad’s book on Egyptian graphic art (1985). There are remarkable parallels between the two paintings. As in Helmy’s etching we find in Abdel-Aleem’s painting, a solitary male figure with a cane, probably blind, who is leaving the entry way to the clinic where the women are shown waiting in line with their children. The suggestion in Abdel-Aleem’s painting is that there is a shortage of clinics or doctors, hence the long waiting line. The closely modeled theme and accentuation of disabled elderly male figures with waiting women patients in both paintings strongly suggests that both artists were in a collaborative dialogue on the importance of the theme and subject of the elderly, women, and children’s health. These paintings may be viewed alongside continuing journalistic efforts for women’s causes. It was the very issue of women’s health and paid maternity leave that their fellow artist Inji Efflatoun had raised in one of her 1958 newspaper articles on the productive role of women in the workforce (Efflatoun 1958).

Figure 8.

Maryam Abdel-Aleem, Clinic (1958). Oil on board, 77 × 83 cm. Image, courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.

Confronted by prevailing patriarchal customs, these young art students and teachers joined an active movement asserting an independence for women. Collectively, they fostered a social philosophy of the arts as both theory and practice, and as advocates of the inclusion of women as subjects of the arts. In so doing, these women moved beyond the stasis model placed upon women by male hegemony that prevailed in the social realist based Egyptian novels of the same period, including those of Naguib Mahfouz and Abdurrahman al-Sharqawi (Selim 2004).

3. Bulaq as a Subject for the Arts and Social Sciences

The social drawings or etchings found in Helmy’s works on the neighborhood of Bulaq, evince a comparison with the famous social novels of the period, most notably Naguib Mahfouz. It is difficult to identify another Egyptian visual artist who so clearly identifies her subjects and their neighborhood over the course of a ten to twelve year period of intensive concentration through etchings, drawings or other medium. Among the many social novels of this period Zuqaq Midaq (Midaq Alley) (1947) allows a direct comparison with several of Helmy’s etchings of the 1950s. A debate about the relative pessimism or optimism depicted in Mahfouz’ Midaq Alley was put forth by literary critics. The choice of Mahfouz to focus on a neighborhood alley in a poor part of Cairo was criticized by Mahmud Amin al-ʻAlim as a backward vision of pessimism (Al-ʻAlim 1970). This criticism was opposed by Sasson Somekh who in an ad hominin attack cites the critic’s Marxism as overstating Mahfouz’s desire for return to a glorious past to evade the realities of an ugly present (Somekh 1973, p. 67). Somekh notes the generalized portrayal of women in Mahfouz’s social novels of the 1940s and 1950s as socially imprisoned, the older women have resigned to their fate, and while the younger women have little or no real alternative to escape other than undertaking risky affairs or prostitution (Somekh 1973, pp. 80–82). By the late 1950s, Edward Al-Kharrat and other writers produced story narratives of urban life that were less dependent and capturing a purely realist depiction and turned toward a trope of psychological realism (Kittani 2013).

How did writers depict Cairo of the 1940s and the environs in which Menhat Helmy, Efflatoun and other women emerged? This was the period in which Naguib Mahfouz emerged with his Midaq Alley and other short stories about Cairo (Maḥfūẓ and Hutchins 2008). There is wide recognition for the author’s placing of a historical-social context for the characters who are interacting with or impacted by recent Egyptian history (Mahmoud 2019). Mahfouz’s 1947 novel, Midaq Alley, intersects with Helmy’s own experiences in these older neighborhoods of Cairo. Some criticism of Mahfouz’s restrictive views and depictions of gender and feminism have been raised (Salti 1994), while others defend his depiction of the difficulty of women’s lives as indicative of the limited choices confronting his women characters while asserting persistence and an active presence in and around the social milieu of Midaq Alley. One may read Midaq Alley in different ways. Mahfouz may be merely restating the existing patriarchal structure that limits women’s options during the late war years, hence the moral dilemma and choice of the young Hamdia to resort to working as a dance hall girl at bars frequented by British soldiers. While Midaq Alley was situated inside Old Cairo, other writers have more directly recalled conditions in Bulaq during the 1940s and 1950s.

In her art, Helmy approaches the social novels of the period. As in Mahfouz’ novels, there is rarely any overt political affiliation or apparent allegiance, instead social conditions are shown as relations between characters in their own space of the neighborhood. Unlike Mahfouz’ social novels, there are no depictions of interior conditions, no insight into the rooms, kitchens, bathrooms or living areas. Instead, Helmy places women and children, the elderly in the public streets and exteriors of residences. These scenes accentuate women’s lives as active agents, unlike the oppressive conditions women find themselves in Mahfouz’s novels. She presents the scenes as drawn outlined forms, set in bold sepia tones or in black and white. The outlines, drapery and lines of the characters, shown as fluid forms stand apart from the rectangles and straight lines of the building details. Geometric lines and textures frame the decorative forms of the brick structures surrounding them and provide contrast and depth of background against the active space for the subjects.

Several of Helmy’s etchings offer views of rooftops with women and children tending to daily chores or taking a moment for reflection or rest. These perhaps recall street scenes developed by Mahfouz in the 1940s, these perspectives of streets and rooftops also featured in later Egyptian fiction (Schlote 2011). Viewed in sequence or as a whole, Helmy’s panoramas and vistas yield a cinematic scope of story board sequences.

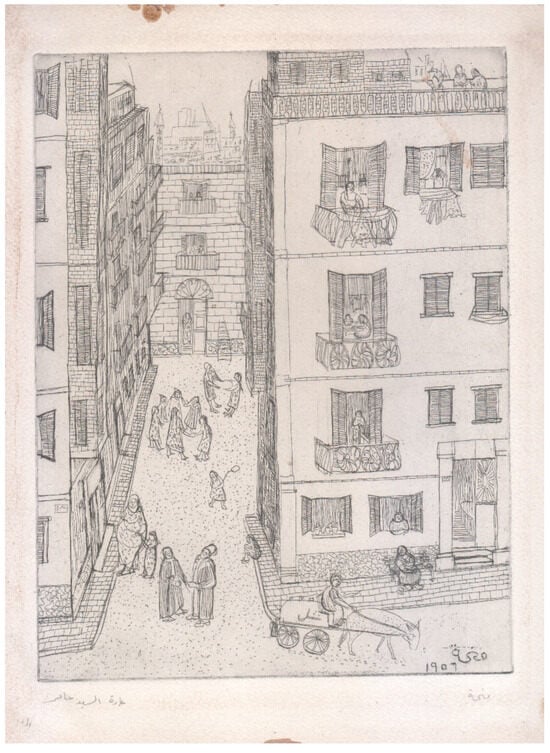

As if in answer to the social novel, Helmy tasked herself with creating a visual series of etchings, that today we would collect and recognize as a graphic documentary or novel. Menhat’s personal interest in the relation of art and literature was affirmed in an interview (Al-Ahram 1978) and in her sister Reaya’s short memoir written for the retrospective exposition (Helmy 2005). In Helmy’s 1956 depiction of an alley (Figure 9), we find a focus on the women and children of the alley. Women on the upper floors hang laundry from their window while looking upon the scene below. Several adults converse at the intersection of the alley with the street, while a mother holds her child’s hand and groups of children are at play within the safe confines of the alley’s inset passage from the traffic of the street. In fact, throughout Helmy’s series on Bulaq and other parts of urban Cairo, we find few automobiles and trucks, rather there are more animal drawn carts of vegetable sellers and other goods, making their way to stores, or outdoor markets.

Figure 9.

Menhat Helmy, The Alley (1956). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

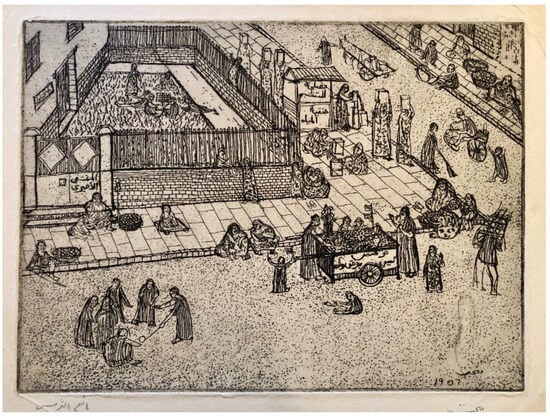

In the Lupin Seller (Figure 10) we find various small vendor stalls surrounding a school with signs announcing their products. In the distant middle of the street, is a water seller at a stand with two signs. The sign above advertises this as medicinal water, and perhaps the vendor’s name below: “Hanifiyya’s Water.” Walking in procession toward the stand are several women bearing water cans on their head, perhaps bringing fresh water to the vendor who uses additives or herbs to freshen the water. This suggests women are perhaps working for or selling to the vendor. Several other women are shown carrying water cans away from the stand, shown as customers of the vendor. Perhaps the women are bringing these as empty cans to be filled up and then taking them home. Alongside the vending stand are two seated figures with a water can. The title of the etching names only one location of this wider scene of women, men and children shown moving about the vending stalls, with young children at play or seated beside a mother seated alone in the left foreground selling some food items. The use of metal cans for these water sellers is a shift in material from the water skins used in earlier periods by vendors (Maʼmūn 2014) and the qila or pottery jugs used to hold and carry water made in Upper Egypt (Koptiuch 1999). As with the substitution of plastic arusa dolls for the sugar baked dolls, or of plastic and mass-produced metal wares that replaced pottery, these shifts in material production reflect the changes in petty commodity production that altered the nature of work and tradecraft (Al-Shal 1967). These metal water cans were possibly a surplus from the German and British military stocks used during World War II and continuing through the early 1950s. A viewer may infer the hardship of bearing water cans to be a sign of a lack of public fountains, pumps or running water.

Figure 10.

The Lupin Seller (1956). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

At the lupin seller’s stall in the front foreground, we notice women customers gathered around the wheeled stand, whose sign advertises the termes or lupin beans, sold as a street food snack, while others are seated in various locations engaged around a stick and wheel game. Is this relative safety and calm of the streets reflective of an idealized panorama of daily life or is the artist instead choosing to show the mixture of play, work and socializing among the women?

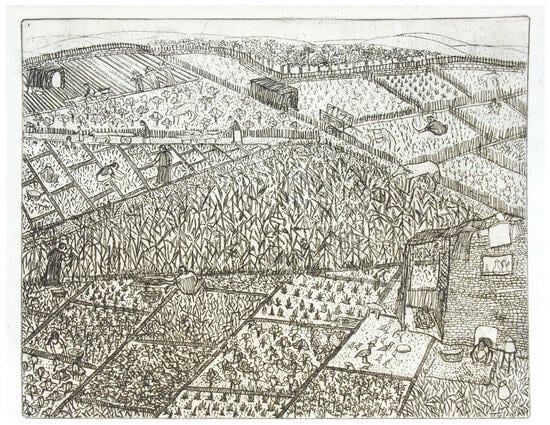

On occasion, Helmy turned out agricultural scenes with sensitivity to rural landscapes and its peasantry that commonly were found in Efflatoun’s paintings from the 1950s onward. An undated etching most likely made during the period between 1956–1966, and entitled Agricultural Production (Figure 11) in the family digital archive, shows Helmy’s interest in rural subjects. The art critic Al-Razzaz also described the title as al-intaj al-zira`a (agricultural production), that suggests a strong attention to what he considered to be the artist’s attention to socialist aspirations and conditions of Egyptian economic and social life (Al-Razzaz 2006). Applying a bird’s eye view, her sweep of the terrain and details of subdivided lands may be viewed alongside a reading of Abdel Rahman Al-Sharqawi’s social novel, Al-Ardh (The Earth). The slightly fragmented outlines of the human figures, shown at work in the different fields, seep into the land and crops that they till, so that a blending of forms, gender, and nature, are subsumed into one another. Each figural representation is indistinct from each other, rather a consensus of shared work is distributed about the entire etching. Helmy’s overview of agricultural labor, shows a marked turn from the emphasis on individual and group scenes of characters that dominated the illustrations by Hassan Fu`ad, the original illustrator for the first edition of Al-Sharqawi’s novel, originally serialized in newspapers and first printed in 1953–1954. Helmy also does not show any large estate home or any other marker of the status of the large landowners who dominated ownership and conditions in modern Egyptian agriculture up through this period. However, in the center of the scene is a triangular field that may be corn or perhaps sugar cane. It is the pattern of the fields, their subdivisions into small parcels, that dominate the composition, and there is a rather even distribution of peasant men and women around the fields, for only a cluster of three are shown tilling the rows of a new field. The scene is of a verdant agriculture, the product of the collection of workers, shown in gestural relief. The location of this rural scene is uncertain, although the art critic Al-Razzaz places her rural scenes at “el-Temsah village in Islamia Province” in lower Egypt (Al-Razzaz 2005b, p. 36; 2006, p. 48), while the family archives contain another etching with the location titled after the Upper Egyptian village of Timshayya, where her grandparent’s family originated.

Figure 11.

Menhat Helmy, Agricultural Production (undated, circa 1956–1966). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy. Note: According to Al-Razzaz (2006), this may have been entitled al-intaj al-zira`a (Agricultural Production).

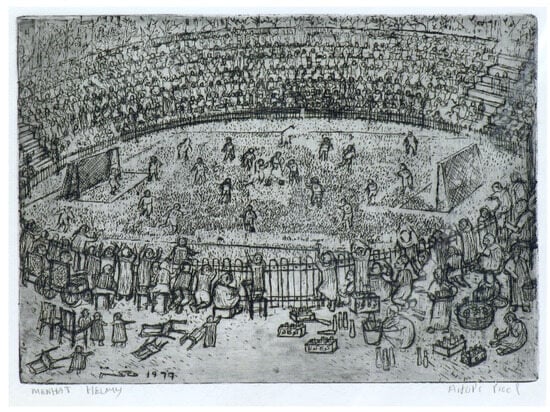

Stylistically and thematically, the bulk of Menhat’s etchings are set in urban Cairo, and perhaps recall the figural gestures of L.S. Lowry’s social scenes of the urban working class industrial areas of northern England. Lowry had connections with the Slade where he had once been a tutor in painting. Although we lack evidence of any direct knowledge or connection with each other’s art, we can reasonably assume that Helmy was well aware of Lowry’s approach to painting scenes of the working class on streets and public spaces of Manchester (Thompson 2013). At the time of Helmy’s admission into the Slade School of Art, Lowry’s reputation had grown to such an extent that he was made the official artist of the new Queen’s coronation in 1952. A direct comparison may be made between Lowry’s 1949 painting The Football Match, with its bird’s-eye perspective (BBC News 2011), the 1953 painting Going to the Match, and Helmy’s own 1966 etching Football Stadium, of a Cairo football grounds and spectators. If Lowry’s painting was shown soon after its completion, it is possible that Helmy, who had just entered Slade would have known of it. In both painting and etching attention is given to the exterior of the stadium, its surroundings and activities of spectators outside the grounds. In Lowry’s Going to the Match, only a glimpse of one grandstand is seen, and emphasis is instead given to the fans forming files of lines to enter the stadium, Helmy gives a bird’s eye view of the stadium, a passing reference to Lowry’s earlier painting. This allows the viewer to gaze down into the rows of seats for the paying spectators and the full gamut of both teams facing off at midfield. One assumes there is a difference in status or choice between the paying customers inside the stadium and the preference of those looking on over the fence from outside. It is this outside cluster of fans that includes what appear to be women and children, and some bottle vendors or discarded bottles from picnickers or spectators remaining outside the grounds.

4. Menhat Helmy at the Ljubljana Biennales in Yugoslavia

By the early 1960s, Helmy had completed a number of her most poignant etchings in the series centered on Bulaq. As Egyptian artists gained the attention and support of the Ministry of Culture, government sponsorship to exhibit abroad enabled a series of artists to exhibit in Western and Eastern Europe, and at other international biennales and exhibitions. During the Cold War years, the Biennale of Graphic arts in Ljubljana was a major center for graphic arts and exhibitions with a wide appeal to artists from the Global South, as well as Central and Eastern Europe. A survey of the history and function of the biennale is found in Komorowski (2018) who situates the Ljubljana Biennale as among a series of regional based international biennales emerging in the 1950s that included the Biennale de la Méditerranée in Cairo, founded in 1955, and the Biennale of Arab Arts in Baghdad. These art movements were closely aligned as socialist influenced culture, now referred to as Nonaligned Modernism (NAM) aligned with the international politics of the Non-aligned Movement. Yugoslavia’s hosting of these art exhibitions was given state support by Tito and the Yugoslavian state to bolster these alliances as ideological countermeasures against the Cold War imperialism of the major blocs of US and Western European capitalism and modernism, and the stylized socialist realism of the Stalin era. The history of the Ljubljana Biennale has received noteworthy attention (Teržan 2010; Biennial Foundation 2021; Videkanić 2019). A review of the rise of post-World War II international biennales is found in (Gardner and Green 2013, 2016). The appeal and wider inclusiveness of artists from the Global South at the Ljubljana Biennale, like those of other emerging biennales as at Dakar (Wictorin 2014), served as an effective counterweight to the more conventional nation-state sponsored model of the Venice Biennale.

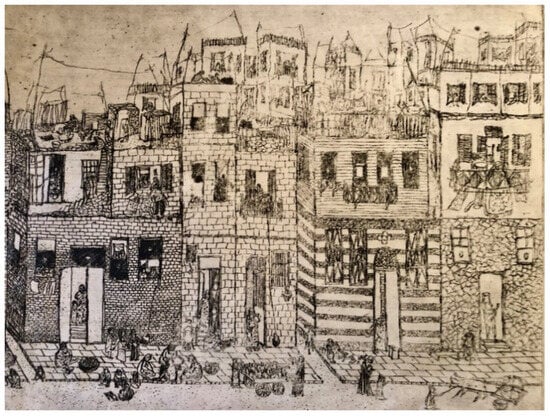

Menhat Helmy exhibited at and attended many of the Ljubljana biennales between 1961 and 1979, as well as at the Biennale de la Méditerranée. Helmy was taking part in what has aptly been labeled as a nonaligned modernism, in which Eastern European, Asian and other artists of the Global South found sponsorship and encouragement. Videkanić identified Helmy as an exhibitor in the 1961 and 1967 catalogues, and gives special attention to the award winning Old Cairo (1957) (Figure 12). In that print, the artist’s attention to graphic details of the building’s textures and patterns, provide a setting for the street theatre of adults and children moving about and working in their everyday lives. The exact number of Ljubljana Biennales that Helmy exhibited is uncertain among scholars. The 1963 catalogue included her Theatre Populaire (1961) and listed two other works, including her Ezbet al-Ward. The 1967 catalogue included three works, including an animal market scene and a rendering of the Aswan High Dam during construction. The 1977 catalogue included three of her abstract and scientific themed etchings, including a color etching, Le mystère de l’univers (1977). The 1979 Ljubljana Biennale (13th biennale) catalogue included two more of her color etchings and noted she had exhibited altogether at the 4th (1961), 5th (1963) and consecutively from the 7th (1967) through 12th (1977) for a total of 9 biennales.

Figure 12.

Menhat Helmy, Old Cairo (circa 1957). Etching. Source: Menhat Helmy family archive and also republished in Videkanić (2019).

“Bulaq Wins Honorary Prize in Yugoslavia!” beamed the headline in an Egyptian newspaper, celebrating a series of etchings by Menhat Helmy, a distinguished Egyptian artist and professor of art (Menhat Helmy Estate 1966). Her prize-winning participation at the 1963 Ljubljana Biennale in Yugoslavia, was the second consecutive award given to Helmy. At the 1961 biennale, an honorary prize was awarded for her etching, “Bulaq,” a representation of that working-class Cairo neighborhood. From the vantage of 21st century with its own serious disorder and challenges, it is worth revisiting those artists from the burgeoning milieu of Egyptian cultural life of the 1940s to 1960s who aspired for and portrayed a realistic optimism and an agency for its subjects.

Menhat’s successful career, her numerous awards and international exhibitions, most notably at the Ljubljana Biennales of the 1960s and 1970s, attest to her international recognition. This article draws upon the resources of the estate of Menhat Helmy who shared original notes, news clippings and interviews of the artist, as well as invaluable images of her original etchings. By focusing on her dozens of images centered on the working-class environs of the Bulaq district in Cairo, her choice and emphasis of subjects was situated amidst a considerable debate on Bulaq’s urban planning that began during the Nasser period. The problems confronting the planning, redevelopment and demolition of parts of the neighborhood followed from the gentrification and rebuilding of the Bulaq waterfront in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In this regard, Helmy’s etchings provide a conscious choice to capture and represent a neighborhood upholding its daily work and social interaction, while confronted by urban disruptions of infrastructure and poverty. A solution was to make women the central figures in her etchings of everyday scenes. This artistic vision and her social philosophy of the arts is compared with other artists and writers who have used Bulaq as the central location of their novel, as in Idris Ali’s Taht al-khatr al-faqr (Under the Poverty Line) (Ali 2005), translated in English by Elliott Colla as Poor (Ali 2013).

In 1957 HIWT was relocated and merged into the Teachers College in the wealthy island district of Zamalek, across the river from Bulaq. Despite the physical relocation of her college, Helmy recalled in an interview that she would take the bus back to parts of Old Cairo to continue her sketching out of social scenes as etchings on zinc (Fanim 1966). In dozens of etchings from the 1950s and 1960s, Helmy shows the everyday life of the industrial and residential neighborhood of Bulaq, and the adjoining districts of Shubra and Ezbet al-Ward. Bulaq remains a working neighborhood, where car mechanics, used and remanufactured auto parts, lumber yards and carpenters, are dispersed among densely built workshops and residential masonry buildings.

Helmy’s recollection of bus trips to Old Cairo, and presumably to the nearby neighborhoods of Bulaq and Shubra, placed her amid the settings found in Mahfouz’ novels, including Khan al-Khalili, Midaq Alley and the area adjoining Al-Azhar. “Old Cairo” resonated in the titling of her award-winning etching of the same title, Old Cairo, (Figure 12) that featured at and was awarded a prize at the 1967 Ljubljana Biennale. Just like Mahfouz and other writers and artists, she chose to move about and capture scenes and characters in their local environs, with a folk realist style.

In Helmy’s reflective view of Old Cairo and Bulaq, the lives of women and children feature amid the relative openness of small public squares or spaces between or around the buildings that in comparison are curiously nearly devoid of any vehicular traffic. Whether this elimination of automobiles is a documentary of the relative absence of automotive traffic in these neighborhoods in the late 1950s or a conscious choice of the artist to depict an imagined recent past is an open question that viewers must decide.

Another set of delicately rendered etchings were dedicated to the mawlid festivals of the neighborhood, the popular sugar doll given to children, and other settings used to celebrate the Prophet’s birthday or on other occasions, the mawlid of local saints. These were subjects found among other artists of this period, including Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar and Jamal El-Seguini, and were admired by the artist and art critic Mostafa Al-Razzaz, who also noted that Helmy’s locations of scenes located along the Nile, to the southwest of Bulaq, between Giza and Zamalek, as resonating with places found in Mahfouz’ novels, notably tharthara fawq al-nil (Adrift on the Nile, 1966) and his Cairo trilogy (1956–1957) (Al-Razzaz 2006, p. 46). In Bulaq on the Prophet’s Birthday, (Figure 13) the artist renders the lace-like hangings of the street decorations in exquisite detail. The etching shows a command of etching point and special care and attention to the printing with the contrast of the darker building windows and balustrades, overlaid with the décor of the street festival and its preparations. The spectacle of popular arts and symbolism of gift-giving and colorful displays was given noteworthy attention by writers and in studies of popular folk arts. These included studies published around the time that Helmy was producing these etchings as in a study of the appeal of colors in popular arts (ʻAbd al-Latif 1964) and a study of the sugar doll craft industry that was soon to disappear (Al-Shal 1967). These may be compared with later studies on the wider appeal and context of the festival (Mustafa 1980) and its links with Sufism (Abu Zahra 1988).

Figure 13.

Menhat Helmy, Bulaq on the Prophet’s Birthday (1956). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

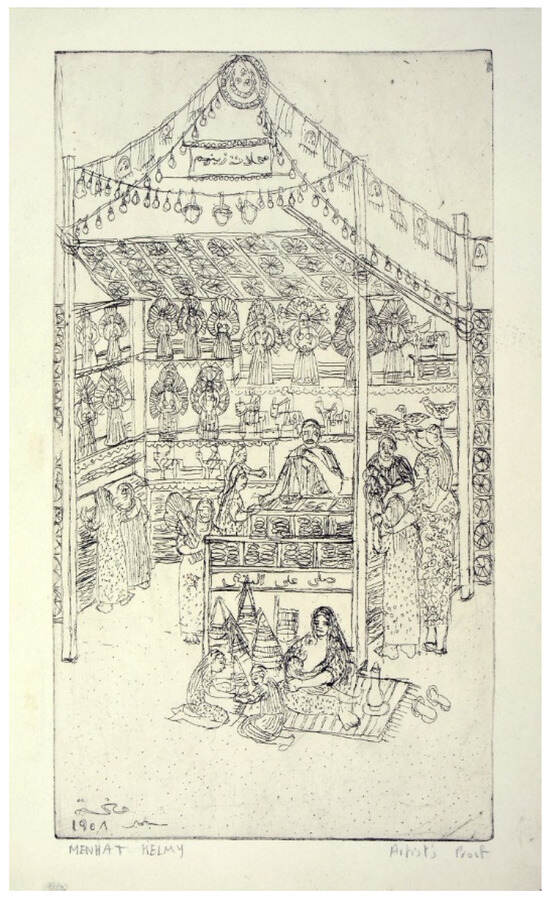

Having sketched a bird’s eye view of the festival in 1956, Helmy later takes the viewer on a tour at street level to its stalls, vendors, customers, and children at play. In the etching Zeinhoum’s Market (Figure 14), the intricate details of a vendor’s single stall filled with rows of ‘arusa dolls and candy are shown. The exacting and close attention to the curtains and overhanging lights and trimmings frame the vendor’s stall and show cards announcing his goods for sale. These were the last decades of the predominance of the crafted sugar doll before the arrival of mass-produced pink plastic dolls appeared. The special features of the doll itself had earlier inspired Helmy to produce a woodcut of the details of the arusa doll with its expressive features, see reproduction and commentary by Karim Zidan on the etching, Zeinhoum’s Market/Sweets of the Prophet’s Birthday (Menhat Helmy Instagram 2022).

Figure 14.

Menhat Helmy, Zeinhoum’s Market (1958). Etching, 15.5 × 21 cm. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

How else may we read and view Helmy’s etchings today, especially with their notable focus on women’s lives? An insight is found in study of gender and space in urban Cairo that included extensive studies of the neighborhood of Bulaq and its environs (Ghannam 2002a)9. Ghannam studied the multiple ways women organized to create small vendor shops and vegetable markets (Singerman 1995). In Bulaq, women used rooftop spaces for raising chickens or ducks, whereas in the more compressed rooftop spaces of the newer public housing, it was necessary to resort to raising pigeons (Ghannam 2002b, p. 69). Vivid details appear in several of the Bulaq and Old Cairo series of Helmy’s etchings.

Bulaq’s modern history witnessed its transformation from a 17th and 18th century winter suburban residence for the wealthy, to an industrial port, and then a mixed industry and dense residential area in the 20th century (Ghannam 2002a, p. 35). Clichés about Bulaq’s negative status as a denizen of crime and drugs, prevailed among modern planners, government officials and journalists in the years leading up to and following the establishment of the public housing projects in Al-Zawiya (Ghannam 2002b, pp. 43, 75). These stereotypes continued to resonate in the opinions by officials and other outsiders toward the neighborhood (Early 1993, p. 32). Other studies of Bulaq and older neighborhoods include Rugh (1979) and Singerman (1995).

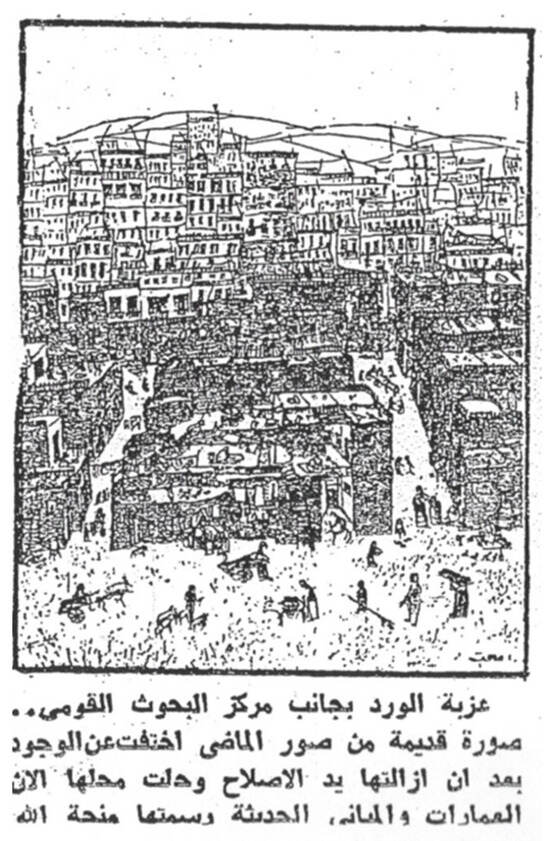

Another etching was entitled Ezbet al-Ward (Figure 15) and is a representation of the neighborhood of the same name. It shows an extensive collection of dense residential buildings of what were then near the limits of the northern part of the city. A reproduction of the image is found in Fathy Ahmad’s 1985 book, The Egyptian Graphic Art as well as in the original catalogue from the biennale (Ahmad 1985). As noted in the caption of the etching that appeared in the news article, Helmy has chosen to render a large section of housing in the neighborhood of Ezbet al-Ward (Figure 15) that was torn down to make way for renewal by new structures. The artist has made a conscious choice to depict the scene as a commentary on the past and the uncertain conditions of those in the neighborhood.

Figure 15.

Caption from 1966 newspaper showing the etching by Menhat Helmy, entitled Ezbet al-Ward (1965).

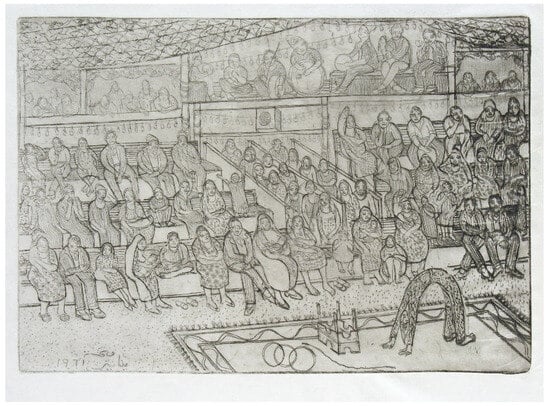

While Helmy was not alone among Egyptian artists in depicting popular performances, circuses and images of the annual festivals or mawlids of the Prophet’s Birthday or other Muslim religious saints, her placement of women in these scenes is emphatic. The art critic Mostafa Al-Razzaz identified these scenes as depictions of the Mawlid of Sidi Salama. In El-Gazzar’s drawings and paintings most of the subjects, spectators and performers are men. But in the 1961 etching of the Circus (also titled as Popular Theatre), (Figure 16), women are predominant in numbers in the front row of spectators as well as the standing area in the middle are mostly women. The centrality of women including young mothers we have seen in the set of a parallel etching and painting from 1958, entitled Outpatient Clinic.

Figure 16.

Menhat Helmy, Circus or Popular Theatre, 1961 etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy. See also, reprint in 1963 Ljubljana Biennale Catalogue.

5. Artistic, Literary and Sociological Interpretations of Bulaq

What about other artists and writers who depicted Bulaq? Idris Ali (1940–2010), is one of the few modern novelists to comment on Bulaq in an autobiographic trope. For Ali, Bulaq was the first neighborhood he moved into in around 1950 with his family migration from Aswan in Upper Egypt, that he identifies as Nubia. This distinction between Sa’idi as Upper Egyptian, and Nubian, denoting those from Aswan or further South, was an emphasis of identity arising in part from the phases of construction of the High Dam. Those from Aswan or further South were forcibly relocated, whereas other Sa’idis from Upper Egypt below the High Dam were migrating for related reasons of employment, poverty or opportunity to be sought in Lower Egypt, and particularly in Cairo. Hence, the use of the term Nubian was a result of this structural difference in economic policy and developments and the avoidance of stereotypes and assumptions about Sa`idi and Nubian conditions require diligence (Ali 2005; Tam 2021)10.

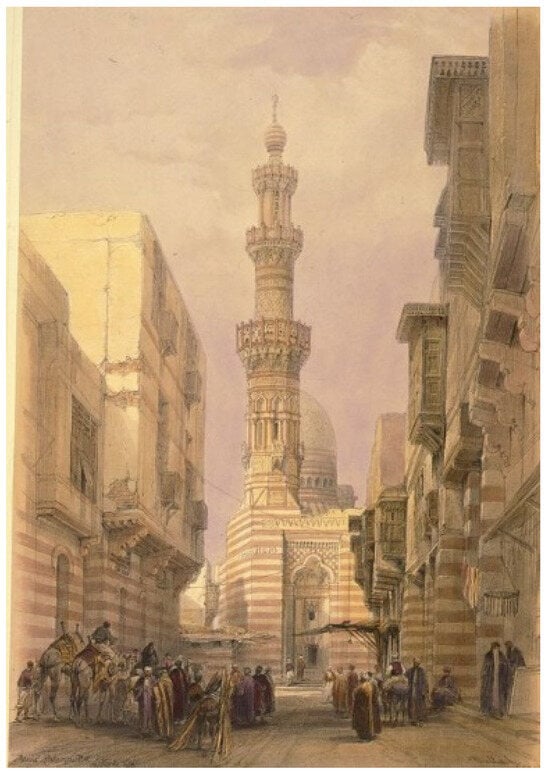

Helmy explained her choice of the neighborhood of Bulaq as a subject for her art in a 1966 interview. Noting the privilege of attending and graduating from the Slade School of Art in the early 1950s, Bulaq’s attraction as a subject was an affirmation of its resonance and influence. From the 16th to early 19th centuries, Bulaq grew as a suburb built on the shores of the Nile to the north of the city. It functioned as the working port for Cairo, connecting it to the trade of the Ottoman Empire, and became the center of shipbuilding, textile mills and other industries. The new mosque architecture and residences transformed the area into a prosperous northern suburb where a new elite relocated (Hanna 1983)11. An idealized view of Bulaq as a newer and prosperous suburb is found in the Orientalist 19th century lithograph (Figure 17) of the Masjid Abu al-‘Ila by David Roberts and (Haghe and Roberts 1846–1849)12.

Figure 17.

David Roberts, Bullack (sic Bulaq) Printed between 1846–1849. Photograph of Lithograph. Source: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002718727/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

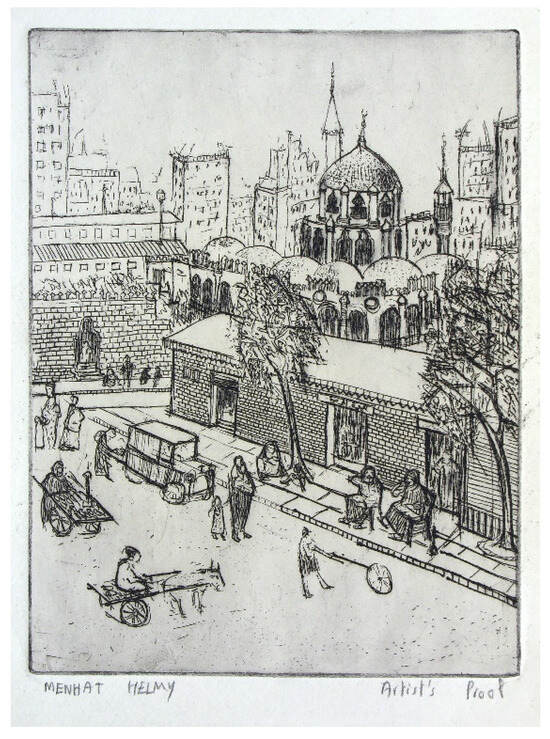

By the mid to late 20th century, Bulaq and the older neighborhoods of Eastern Cairo, often called Old Cairo, have become clichéd tropes for contrasting rich and poor, and failures of governance, planning and development. Concern for the fate of Bulaq and the clash between plans for reconstruction and transformation of the waterfront and demolition drew the attention of scholars to the threatened status of monuments and historic areas (Hanna 1980). When Helmy turned toward these neighborhoods for her series of etchings, Bulaq and its adjoining neighborhoods, Turgoman, Shubra and Ezbet al-Ward, were crowded, poor and in need of new infrastructure and rebuilding. In contrast to David Roberts’ mid-19th century Orientalist idealized view of one of Bulaq’s most famous mosques, in which the mosque is centered and made the focal point, Helmy situates her rendering of a mosque to right of center and places a single-story brick residence or shop in a diagonal that crosses and obscures the view of the mosque itself. Whereas Roberts’ vista leads the viewer on the righteous path to the mosque, Helmy interrupts this path and makes the viewer negotiate and weave about the characters in the foreground. A child plays with a stick and hoop in our immediate but imaginary footpath. We must then weave through several carts. An automobile is outlined and parked at curbside. A mother carrying an infant is walking beside another child in the street, while several residents look upon the scene from the front of their shop or residence (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Menhat Helmy, A Mosque in Bulaq. Artist’s Proof. 1956. Etching on zinc. 16.5 × 21 cm.

A demographic and census study comparing Bulaq and Zamalek published in 1996, pointed out Bulaq’s high rates of illiteracy at about 42% (Ḥuzayyin 1996, p. 29)13. These conditions had prevailed since the Second World War as migration increased from the rural areas. When Helmy rode the bus from Zamalek across the bridges of the Nile back to Bulaq and Old Cairo on the east side, she was crossing from two vastly different neighborhoods, separated by wealth and poverty, education and illiteracy, affluent residences and poor densely populated residential areas. As a teacher she was aware of the difference between high rates of literacy in Zamalek where she taught and the prevailing level of illiteracy in Bulaq. The differences were so stark that the main reasons any illiteracy in Zamalek reached about 12% could only be attributed to its more or less, temporary workers, who worked as bellmen, doormen, and servants for its rich permanent residents (Ḥuzayyin 1996, p. 30). Helmy resolves these class differences in a visual language drawn into her etchings, just as the poor and illiterate used radio news to inform themselves of current and national events.

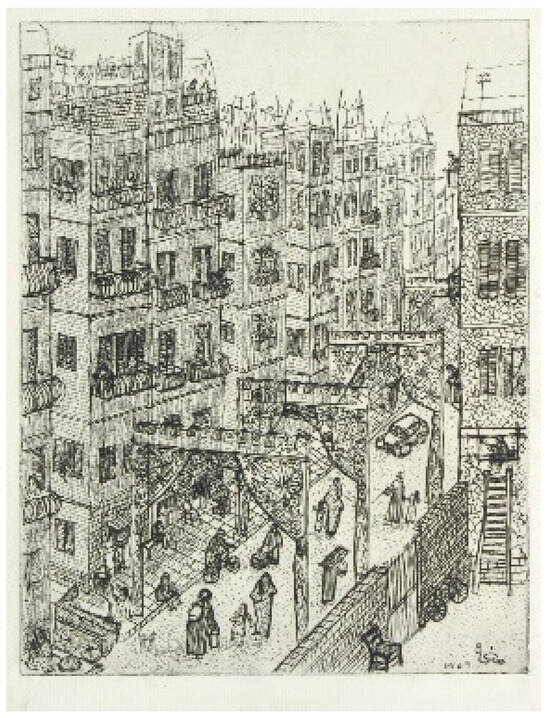

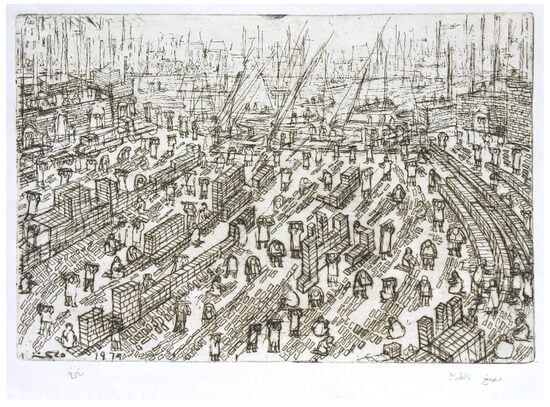

Bulaq’s industry continued, as its many workshops, mills and car repair shops, lumber yards prevail, despite the relative lack of wealth and high unemployment of the area. In her series of etchings Helmy displayed scenes of animal markets located across the river at Imbaba, as well as shipbuilding and repairs (Al-Razzaz 2005b, p. 36). In one of her last etchings of Bulaq from 1969 (Figure 19), we find another of these scenes of a large outdoor brick factory, making use of manual labor to haul, mold, and lay out bricks, apparently to be dried and baked in the sun, and located near the shores for transport by boat. Is Helmy choosing to depict the scale of industry and labor as it is, in real space and time, or was this an interpretation of the passing of a scale of labor and employment that was vanishing? Given her comments in interviews, the artist was determined to depict what she had witnessed. Was this etching made in anticipation of the threat to its status? We cannot be as certain from this scene, but we know from comments on her etching of Ezbet al-Ward that she was intentionally capturing the passing of a neighborhood before its destruction.

Figure 19.

Menhat Helmy, Brick Factory. (1969) Etching.

In the 21st century a spate of dystopian novels about Cairo cast these neighborhoods as the contemporary locus of social crisis, distress and despair. These include Tarik Khaled Ahmed, Utopia (2008), where in the near future, the rich live in walled and heavily guarded enclaves and hunt, kill and kidnap the poor of Cairo as a sport. In Muhammad Rabie’s novel Otared (2015), Cairo in the year 2025 is divided between a newly invaded occupied East Cairo and the resistance based in West Cairo. The protagonist resistance officer directs an assassination squad from the 15th floor of Cairo Tower, the only active building on the formerly rich bourgeois island of Zamalek, now deserted because of massive bombardment, and that straddles the Nile between the poorer East and richer West Cairo. In yet another novel of the future, Makinat Cairo (The Maquette of Cairo), the author veers between the Spring uprising of 2011 and the year 2045, where the Gallery Makinat remains a transitional space for art straddling the third of a century that has passed since the failed popular revolt. These doubts about the city and its neighborhoods, its people and livelihood are given the grimmest of descriptions by the character Otared, who describes the remains of decaying, and abandoned office and hotel complexes circling Tahrir Square. These scenes of abandonment are a mimesis for they extend the current rebuilding projects undertaken by the Egyptian state. These include Egyptian government decision to relocate the corpus of the colonial era Egyptian Museum to the safer environs of a new structure in Giza, but also the decision to relocate the capital itself, and the symbol of the bureaucracy, the Mogamma Building, by building a new capital district in the Eastern desert (Singerman and Amar 2006)14. In describing the origins of this dystopian crisis, it is the character Otared, who describes the neighborhood of Bulaq thus:

To the north was the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a tall European gent in an oriental turban, looming over the city, and at his back those numberless interlocked blocks of smaller buildings with no architectural style, or layout, or even specification in common, cut up by crooked streets whose widths would alter every hundred yards: the chaotic neighborhood of Bulaq Abul-Ela, its disorder a fitting backdrop for the infantile troublemaking that had broken out there years before.

In these approaches, the dystopian novels of the 21st century confront the current hegemony of the military governments’ monopolization of the state and support for the separation of the rich from the poor. Hence, Bulaq and its environs are seen as in neglect or to be neglected. A more direct and insightful analysis of the function of state power to engineer itself against the poor is found in the urban planning study by Gehan Selim (2014, 2016). Numerous studies have approached Bulaq as a problematic sector of Cairo’s urban governance, policing and development (Khalil 2015; Shakran 2016). In his ethnographic study of the Ramlet Bulaq sector, Omnia Khalil analyzed how planners and officials demonized the poor of Bulaq and other neighborhoods as Ashwayyat or “chaotic neighbors” or as criminals (Khalil 2015). Khalil shows how the residents of Bulaq organized around their class consciousness to acknowledge not only those residents who were victims of state violence against some of their neighbors. This determination led the residents of Ramlet Bulaq to organize their own resistance and public march and demonstration that pressured the courts to grant a stay of eviction from residents of the neighborhood. For a conventional architectural history approach centered on Bulaq’s religious structures see Williams (Williams 2008). For a study of how local residents cope and adapt their own social space in residential areas, including Bulaq, see Ghannam (2002a) and Selim (2016). Other approaches study the security apparatus as applied to Bulaq (Ismail 2006).

As we recognize a new horizon for a theory of the space and place of art, we also encounter increased censorship against the popular art forms, notably in the suppression by the Egyptian Musician’s Syndicate against the Mahragana music movement based in Bulaq and working class neighborhoods. As another example, in 2017, the Syndicate of Arab Musicians became the proxy for the Ministry of Culture to suppress cultural forms that it saw as threatening or inciting insurrection, criticism, sarcasm or mocking of its authority. This led to their decree forbidding the hiring of Mahraganat singers at nightclubs (Egyptian Streets 2020). This formal censorship was confirmed four years later, when the head of Egypt’s Musicians Syndicate Hany Shaker, who has been its most visible spokesperson, pressed his attacks as recently as last November, to continue the ban on the singers, as he called for the “return of musical education classes to schools and increase interest in all arts academically15.” Yet, in “Bulaq”, a short 3 min film by Wael Alaa about the Mahraga music and dance, the protagonist musicians declare: “It is art… There isn’t a social class that doesn’t listen to mahragan.” Hence, the need of the state and the ruling elite to suppress popular art movements reflects a crisis over their hegemony and resort to repression (Alaa 2017; Zuhur 2022).

In Mahfouz, we found a sequential chronology in the novels form the 1940s to 1950s, so as to represent life events in causal relations to one another and interacting with other characters (El-Enany 1993). A similar representation of time in confined and historical sequence marks Abderrahman’s Al-Ardh (The Land). The contemporary novels of the 21st century transcend passages in time to compare conditions of the present with the past, or in other novels of the future with the near present. In his semi-autobiographical novel, Taht khatt al-faqr (Poor) (Ali 2005, 2013), Idris Ali begins his narrative of present day Cairo in his opening chapters and then recounts his childhood, and the conditions of poverty in the environs of Bulaq Abul-l-Ela as the place of settlement for recent migrants from Nubia in Upper Egypt. In his chapter “Bulaq Abul-l-Ela 1950 Rock Bottom” he compares the absolute poverty, yet clean and pristine environs of Nubia, to the relative poverty and abject conditions of crowding, filth, and lack of sanitation in Bulaq of the 1950s. To what extent, however, has the author injected portrayals from the deterioration of Bulaq by the 21st century onto the neighborhood of 1950? On city life, the father of the migrant Nubian family says to his son:

People here are different than where we’re from, especially in the working-class neighborhoods. Poor people help each other out and things are a bit relaxed.(Trans. Elliot Colla, p. 85)

During the 1950s Bulaq appealed as a place of settlement for new migrants from Upper Egypt because of its proximity to the adjoining neighborhood of Shubra al-Khayma, where light industries were increasingly placed (Selim 2014, p. 74). Ali’s descriptions focus on the crowded and appalling effects of the interiors without descriptions of the exteriors, courtyards, and small semi-public spaces that are the themes of Menhat Helmy’s etchings. What is not certain is the extent to which Helmy had personal interactions and invitations by local women into their homes or whether her choice of emphasizing women and children’s roles on the outside is a deliberate commentary to counter the prevailing patriarchal image and chant of conservatives in the 1940s al-mara’tu li’l bayt (Women belong in the Home).

In Idris Ali’s novel, its characters venture outside Bulaq, just as Hamdia, the female protagonist in Mahfuz’ Midaq Alley, took walks to the prosperous merchant streets, not unlike a character in Proust. In Ali’s Poor these walks and ventures across Champollion Street and Suleiman Pasha Street, reach Cairo Station where the difference in social class is consciously evaluated, and where the father figure of Bulaq is deemed as seemingly insignificant or worthless because of his poverty.

These kids work in workshops. They’re dropouts. They’ve been kicked out of their homes. They’re runaways, fleeing the bottom of the bottom. These kids are the dregs. The able-bodied among them play soccer with a rag ball. Ever since a kid from Bulaq joined the Ahli Sports Club team and became a star, these kids dream about the big sports clubs.(Trans. E. Colla, pp. 97–98)

In the Helmy etching of a football match (Figure 20), we find a sharp contrast to a reading Idris Ali’s description of the dreams of using football to escape. While Ali centers on football as an agency for the low probability but high reward of attaining a professional football track, Helmy accentuates the social fabric of the spectators, families with women and children picnicking on grounds overlooking the fence down onto the football field, while inside paying customers ring the field in their seats or stands.

Figure 20.

Menhat Helmy, Football Stadium (1966). Etching. Courtesy of estate of Menhat Helmy.

In Ali’s chapter “Gorky,” the aspirations of climbing out of poverty are found by the protagonist through reading Maxim Gorky, including his autobiography My Childhood, and novel, Mother. This too has resonance with the recollections of other Egyptian artists, poets and middle-class students who read Gorky in the 1940s. It was in the 1940s that the young teenager Inji Efflatoun had been introduced to Gorky’s novel Mother. Idris Ali’s protagonist seeks out literature and books to achieve a sense of self-worth and knowledge, and to compare his world with other literary representations of poverty as found in Gorky. The sense of fate as one’s social class is discussed in references to Mahfouz’ 1949 novel about the failed aspirations of middle-class family falling back into poverty while living in the newer suburbs of Cairo, The Beginning and the End. In that novel, we find again that one of the main female characters, the young Nefisa, is set up for disappointment, heartbreak, and resorts to serial affairs with men for money. Like Hamdia, in Mahfouz’s earlier novel, Midaq Alley, there are only passing vignettes of hope and ultimately setback for women’s lives, who instead are seen as victims of unchanging patriarchy as these women must be resigned to their fate and live within their shame. None of these scenes or assumptions are found in any of Helmy’s etchings of Bulaq and its environs.

6. Menhat Helmy’s Later Career

Beyond her Bulaq and Cairo City series of etchings that ranged from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s, Helmy resumed an expansion of themes and medium through explorations of abstract designs in etching and paintings. Some of these were developed while she was developing the Bulaq series. By the 1960s we find a series on the Aswan Dam, and in the 1970s and 1980s, paintings of space exploration and astronomy (Ahmad 1985)16.

An Al-Ahram article and interview in 1978 gave Helmy a voice to comment not only the place of women artists, but of women’s careers and aspirations. When asked whether there is to be an independent art school, inferring the type of school she attended in the 1940s, Helmy responded that “I am convinced that art does not differentiate between the sexes,” and recalled the success internationally of other Egyptian women artists including Gazbia Sirry (sic) and Inji Efflatoun (Al-Ahram 1978).

Helmy’s understanding of the meaning of history, past and contemporary makes her art more compelling and requires an attendance to detail and relations between characters, spaces, and actions. Through her art she presents a philosophy of art that recognizes the dignity and perseverance of the poorest neighborhoods and residents of Cairo. As an artist whose own career shows great resilience, and determination, this same optimism is carried through to her subjects who are not seen as failures of a society or as residents of a failed neighborhood. Rather the respect of place and its residents is given gravitas.

Helmy asks that we accept the presence and contributions of all of society’s members. Idris Ali in his passages on Bulaq of the 1950s, portrays the unrealized dreams and stasis of Bulaq, through the autobiographical tone of his own knowledge and journey to become a writer while in his own life he worked construction jobs to support himself for much of his life. Idris Ali then may himself be inserted as a character into one of Helmy’s etchings. From these varied approaches we find a reckoning with the challenges of hardship and real life, whether the Orwellian warnings of the worst that may yet come as in the dark novels of Muhammad Rabie, Otarad (2015) and Ahmed Tawfiq’s Utopia. Helmy provides a vivid recognition of the conditions of past and present through these non-judgmental etchings. These contrast with the setbacks and reality of prejudice and bias against the poor found in Idris Ali’s Poor. From each may be found poetic insights into the conditions of the recent past as well as in our own times.

7. Conclusions

This article has focused only on select aspects of Helmy’s art career from the 1950s through the 1960s whose art of this period asserted an evolving feminist vision and an active role for women as artists and teachers. Her teaching career spanned nearly 50 years from around 1956 until her death in 2004. Her works were included in a group show in 2005 (Darwish 2005), and in a retrospective on her art shown in 2005, the year after her death (Al-Ahram 2005; Al-Quds al-`Arabi 2006). Her friend and fellow artist, Mostafa Al-Razzaz, who had written a moving obituary (Al-Razzaz 2004) wrote several catalogue entries and articles (Al-Razzaz 2005a, 2005b) on the importance of her career and life that included a discussion of the later phases of her career from the 1970s to 1980s in abstraction and graphic design (Al-Razzaz 2006)17. Al-Razzaz emphasized Helmy’s originality and invention among Egypt’s 20th century modern artists, as being among the first to experiment with the graphic arts and etching. In choosing images for the article, he noted the Bulaq based sites in her works, such as the Jami` Mosque of Sinan Pasha, and selected scenes of etchings of Bulaq and this early period of her career, including The Elections, and Outpatient Clinic from 1957–1958. He also selected and highlighted one of her most colorful and vivid paintings, entitled al-hayat al-sha`abiyya (The People’s Lives) showing a procession of peasants walking home from the fields bearing the fruits of their labor. Her later abstract art from the 1970s and 80s, incorporated science and astronomy, and anticipated a future in which Egyptians share in the universe of exploration.