1. Introduction

In 1976, when Jimmy Carter defeated incumbent president Gerald Ford in the presidential election and two IT giants, Apple and Microsoft, were incorporated, the U.S. celebrated the 200th anniversary of the American Revolution. The Bicentennial celebrations of the formation of the American state paid tribute to the historical events that led up to the creation of the U.S. as an independent republic. Although destined primarily for the American nation, the Bicentennial was more than just a simple matter of domestic politics. It was a high-profile international event that went beyond the U.S. borders. Indeed, U.S. public diplomacy commemorating the occasion “amounted to one of the more significant such campaigns in U.S. history” (

Bennett 2016, p. 696). This was partially because the Seventies were an unusually challenging decade for American foreign policymakers. Speaking in former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s language, the defeat in Vietnam that damaged the country’s international image coupled with the domestic economic malaise led to years of upheaval of U.S. diplomacy worldwide. As historian Claire Bower points out, “even as arts diplomats attempted to construct their programs from the products of the private cultural sphere, the democratic nature of the U.S. that they strove to represent abroad could be easily hijacked by shifting political winds at home” (

Notaker et al. 2016, pp. 122–23). Under such circumstances, “a liberating memory of the American Revolution” represented a unique opportunity to spread globally the “idea of America” in an attempt to “repair the nation’s stained reputation” (

Bennett 2016, p. 696) that dominated the 1970s international public mind.

At the moment when America celebrated its Bicentennial, one of its prominent citizens, Pop artist Andy Warhol (1928–1987), enjoyed growing popularity. Compared to the rebellious Sixties (

Watson 2003), the Seventies were a much quieter decade for Warhol. On 3 June 1968, a radical feminist activist, Valerie Solanas, attempted to assassinate Warhol in his Factory studio, the shooting leaving considerable physical and emotional trauma on the artist. Following the accident, the artist shifted his focus from expanding his social circle to business and entrepreneurship. Among others, in 1969, he co-founded

Interview, a magazine devoted to film, fashion, and popular culture that gave him direct access to American pop stars. In 1971, Warhol, together with Craig Braun, designed the cover for The Rolling Stones’ album

Sticky Fingers, which was nominated for a Grammy Award. In 1975, he published his iconic

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) book and in 1976 started with the help of his assistant Pat Hackett chronicling his daily life, which would be published posthumously in 1989 as

The Andy Warhol Diaries. Since the early 1970s, a celebrity, Warhol began receiving hundreds of commissioned portraits from socialites, film and music stars, and mediated personas. As art historian Robert Rosenblum has once pointed out, Warhol “had become a celebrity among celebrities, and an ideal court painter to this 1970s international aristocracy that mixed, in wildly varying proportions, wealth, high fashion, and brains” (cited in

Geldzahler and Rosenblum 1993, p. 144).

Today, Andy Warhol, together with Pablo Picasso, is recognized as one of the two most expensive twentieth-century artists. In May 2021, five unique NFTs based on Warhol’s digital artworks created in a paint program on the artist’s Commodore Amiga personal computer in the mid-1980s were sold at Christie’s Online for a total value of a little bit more than USD3 million (

Christie’s 2021). In 2022, Warhol’s iconic 1964 silk-screen portrait of Marilyn Monroe

Shot Sage Blue Marylin was sold at Christie’s New York for USD195 million, the highest price ever paid for an American artwork at auction (

Christie’s 2022). Warhol seems to be omnipresent in the contemporary art world. According to the artist’s biographer Victor Bockris, the exact number of Warhol’s exhibitions is unknown: “no complete list of every show [Warhol] ever had existed and it seems doubtful that it will since he was so prolific and had several shows in places like the glorified ice-cream shop, Serendipity, that were not considered exhibitions in the conventional sense” (

Bockris 2003, p. 548).

Even though some academic research sheds light on the history of the international circulation of Warhol’s oeuvre during the artist’s lifetime and after his death (

Curley 2013), nothing is still widely known about his contributions to the international celebrations of the U.S. Bicentennial. The current paper aims to fill in this research gap in the academic literature on the history of U.S. cultural diplomacy (

Dossin 2015). It examines how and why Warhol’s painting

Silver Liz was exhibited in the

200 Years of American Painting exhibition organized by the U.S. government in Bonn in 1976 as part of the international celebrations of the U.S. Bicentennial. The paper first discusses the art historical place of

Silver Liz in the Bicentennial show and then explains what cultural-political effects the inclusion of Warhol’s work in this exhibition had on both the artist’s international success and the U.S. Cultural Cold War strategy.

2. Crucial Role of Art Exhibits for U.S. Cold War Cultural Diplomacy Strategy

Historically, culture had remained at the periphery of the U.S.-government-driven diplomatic initiatives and had been the job of non-governmental institutions or the initiative of private individuals who “busily traveled on the international culture circuit” (Gienow-Hecht in

Osgood and Etheridge 2010, p. 44). With the beginning of the Cold War, however, chaotic private cultural initiatives typical of the nineteenth and early twentieth-century U.S. cultural diplomacy gave way to “an ideologically inspired bureaucracy that was more responsive to managerial imperatives and competitive rationales than to a tradition of liberal idealism for its policy decisions” (

Ninkovich 1981, p. 168).

It is worth mentioning at once that during the Cold War U.S. cultural diplomacy was an unalienable part of the U.S. public diplomacy apparatus. Whereas the practice of U.S. public diplomacy was institutionalized with the creation of the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) by Executive Order 10477 in 1953, the theorization of the phenomenon of public diplomacy began only after the establishment of the Edward R. Murrow Center of Public Diplomacy within the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University in 1965. The founding brochure of the Murrow Center provided the following definition of U.S. public diplomacy:

Public diplomacy…deals with the influence of public attitudes on the formation and execution of foreign policies. It encompasses dimensions of international relations beyond traditional diplomacy; the cultivation by governments of public opinion in other countries; the interaction of private groups and interests in one country with another; the reporting of foreign affairs and its impact on policy; communication between those whose job is communication, as diplomats and foreign correspondents; and the process of intercultural communications.

Since culture played a central ideological role in the Cold War (Shibusawa in

Immerman and Goedde 2013), the contending powers sought to use national cultural achievements, ideas, and persuasive communication tools “to rally, sustain and extend their respective blocs” and to bombard “one another’s home populations with messages to elicit political advantage” (Cull and Mazumdar in

Kalinovsky and Daigle 2014, p. 323). From historian Gordon Johnston’s perspective, “there was no neat alignment between aesthetics and politics during the Cold War” because the accounts of the Cultural Cold War and histories of modernism understated or missed altogether “modernism’s role in Central and Eastern Europe” (

Johnston 2010, p. 291). Unlike Johnston, historian Alain Dubosclard (cited in

Rolland 2004) offers a more complex explanation about why culture became so unexpectedly a crucial element of U.S. public diplomacy during the Cold War. From his perspective, no scholarly works about the place of culture in international relations had been written over the period between 1940 and 1945. At the same time, many European intellectuals were forced to flee from the Nazi regime. Most of these emigrants settled in the U.S. and managed to ‘acculturate’ the local elites in their new home country. As a consequence, the U.S. occasionally turned into the global cultural capital of the Western world. By realizing these unique historical circumstances and the country’s hugely underused cultural potential, the U.S. government decided to turn culture into “a key agent in planning for the possible extinction of communism through a war of global and devastating proportions” (

Parry-Giles 2002, p. 172).

The issue of the interrelatedness between U.S. public diplomacy and American fine arts during the Cultural Cold War remains largely on the outskirts of academic research. Historian Michael Krenn argues that the unpopularity of American fine arts as a research object in the study of the Cultural Cold War is because the U.S. government and American art lovers “were never able to discover a happy medium between art as art and art as propaganda” (

Krenn 2005, p. 4). According to historian John Curley, one should not neglect the role of fine arts in the Cultural Cold War because the Cold War per se was a way of seeing the world. In his opinion, “the

visual qualities suggested by the phrase ‘ideological blindness’—a phrase that came into popular use at the very start of the Cold War, describing how rigid political beliefs can twist perception and interpretation in irrational ways—leads to a consideration of the importance of images, specifically art, to the conflict” (

Curley 2019, p. 10). Interestingly, both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who coined the term “the Iron Curtain”, and U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, who founded USIA, were committed, amateur painters.

Ironically, it was the Soviet Union’s cultural diplomacy program, or as Americans called it the “Soviet cultural offensive” (

Barghoorn 1960), which gave President Eisenhower an official excuse to “completely reshape America’s approach to culture as a Cold War tool” (

Krenn 2017, p. 98). It is not a coincidence that USIA was established in August 1953 as a counteroffensive to the Soviet cultural offensive and that culture alongside the mass media turned into one of the most powerful public diplomacy weapons of “telling the truth” (

Barrett 1953;

Dizard 2004) about America and its people. During the Cold War, USIA used a variety of mass media and cultural tools to win the hearts and minds of foreign publics. To fulfill its ample goals, USIA operated several information and communication channels.

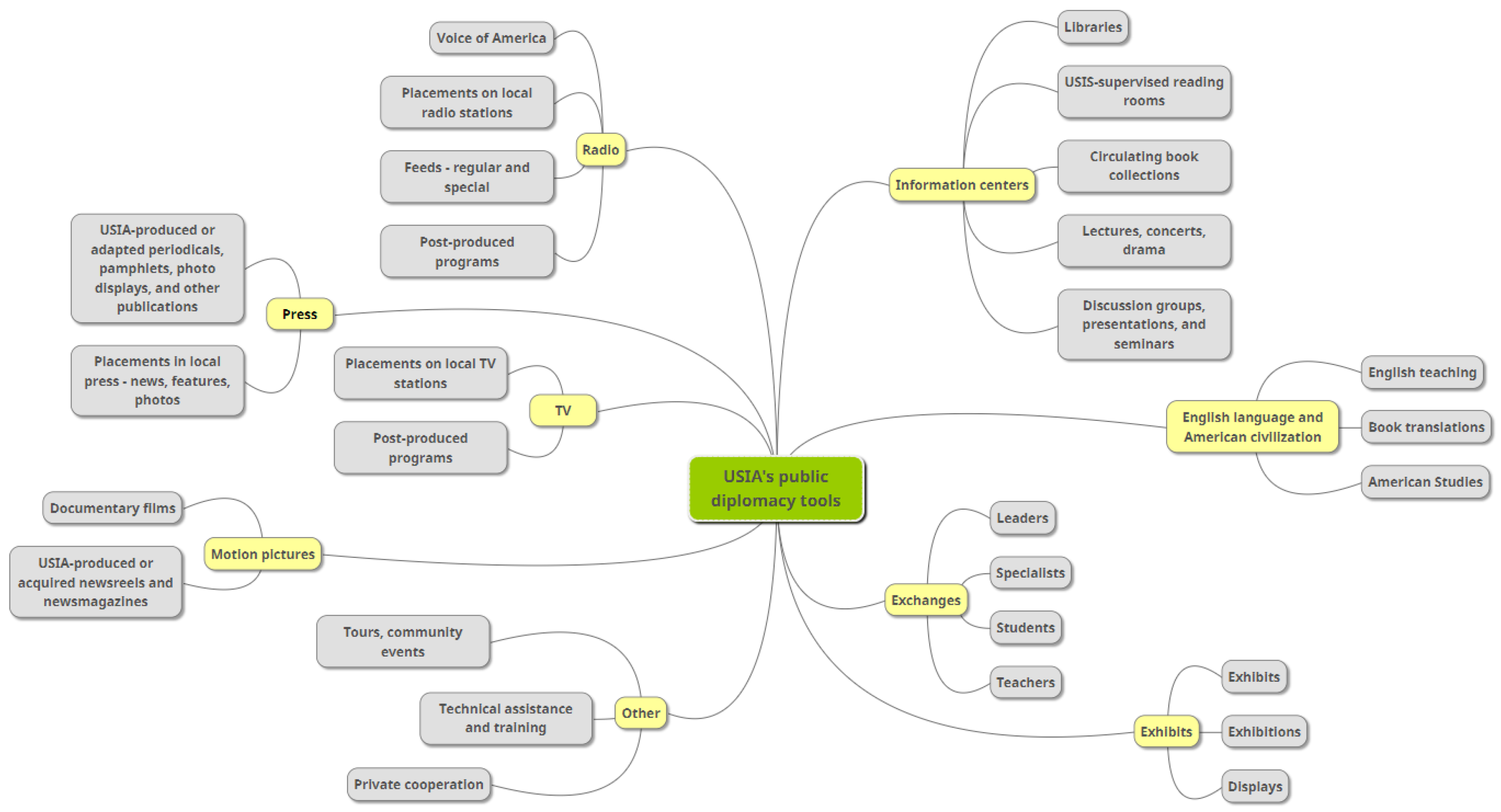

Figure 1 shows the functional organization of USIA’s public diplomacy apparatus.

As it follows from the above-presented cognitive map, exhibits

1 were a very specific instrument of USIA’s Cultural Cold War strategy. Whether they were “the presentation of the works of one American painter or an elaborate, specially-designed exhibition on a theme of international interest”, exhibits constituted “another of the public diplomat’s tools” (

Hansen 1984, p. 146). The more elaborate they had, the more costly they were. By their nature, exhibits demanded considerable time and effort in both the preparation and operation stages. Furthermore, their international political impact was not long-standing: it disappeared when the exhibit ended. Taking all this into account, USIA’s officers were “less than enthusiastic about employing this technique in their program plans” (

Hansen 1984, p. 146). In their opinion, exhibits were a “fine” public diplomacy tool, if it was “the right place, at the right time, with the right exhibit and the right audience” (

Hansen 1984, p. 146). Otherwise, except for small exhibits that were “easy to mount and easy to handle”, their cost-effectiveness was “questionable” (

Hansen 1984, p. 146).

USIA’s exhibitions aimed not just at displaying American national culture to foreign audiences but at using certain cultural elements to communicate with the international public. The Special International Exhibitions Program was introduced to USIA in 1954. With the agreement of the Office of Management and Budget of 1966, most funds of USIA’s circulating exhibitions program went to finance the program in the countries of the Communist bloc. In 1976, however, USIA attempted to rewrite rules for the funding of its traveling shows to enlarge the geography of its exhibits to the developing countries in Asia and the Middle East. This attempt was not very successful. The Office of Management and Budget, which was a key institution in allocating funds for all USIA’s public diplomacy programs, did not receive this idea very well. The Office insisted on USIA’s main exhibitions focusing on the Soviet Union and the Soviet-bloc countries. As a result of the heated discussions, USIA’s Special International Exhibitions Program and the Office of Management and Budget reached a compromise that USIA, while sticking to its previous Cultural Cold War commitments, could send exhibitions to some other parts of the world from time to time. For example, in 1977, the Office granted USIA an annual budget of

$44,263,000. Out of this sum, only

$250,000 could be spent outside the Communist bloc (

Cull 2008, p. 338).

According to historian Andrew Wulf, the zenith of U.S. Cold War cultural activities abroad comprised four categories of exhibitions: international trade fairs, official exchange exhibitions with the Soviet Union, World’s Fairs pavilions, and museum exhibitions. Wulf’s classification is rather narrow. For example, he says nothing of the Venice Biennale. At the same time, as Wulf argues, irrespective of their size, all exhibitions organized or sponsored by the U.S. government during the Cold War shared the same public diplomacy function: they “were developed to demonstrate to all visitors—regardless of geographical locale, ethnic identity, or religious affiliation—the attractiveness and superiority of the American way of life” (

Wulf 2015, p. xiii). In the case of USIA’s traveling shows, in particular, the exhibitions also conveyed to the Communist public the risks of not buying into the national ethos, namely the American Dream. Wulf summarizes brilliantly the public diplomacy objective of USIA’s international exhibitions in the following two sentences:

In this either-or scenario of West versus East, capitalism versus communism, or America versus Evil Empire, the United States was selling more than just department-store-like windows onto a graspable national utopia, a guarantee of material, spiritual, and political prosperity. This was also, arguably, a form of Cultural Manifest Destiny, the colonizing of other cultures through the manipulation of images of what “America” is.

Given such reasoning, USIA’s officers regarded the U.S. Bicentennial not only as a good moment to launch certain public diplomacy programs but also as an opportunity to come up with new methods of conducting U.S. public diplomacy. In particular, the Bicentennial brought about two novelties into USIA’s public diplomacy practice. Primarily, USIA doubted for the first time the effectiveness of U.S. public diplomacy as a one-flow channel of international communication. Due to a widening credibility gap in the post-Vietnam world, USIA’s officers adapted the international celebration of America’s independence to the idea of the interdependent world gaining ground in the 1970s. So, instead of simply lecturing foreign nations about what the American Revolution meant for the whole world, the organizers of the Bicentennial celebrations wanted to gather other nations’ views on American statehood (

Honour 1976). By inviting its counterparts from France and other countries with historical ties to the U.S. to participate in the common celebration of the Bicentennial, USIA turned “what well could have been a monologue about American heritage into a multinational dialogue about the shared past as it pertained to the present” (

Bennett 2016, p. 697).

In addition, on the occasion of the Bicentennial, USIA’s program officers had to deal with the issue of memory as a Cold War cultural-political instrument for the first time. Never before had U.S. public diplomacy been involved in the production of historical memory and the exercise of American soft power. The potential of public diplomacy as of generator and communicator of collective memory first applied in practice by USIA during the Bicentennial celebration would long remain in the shadow of academic research. Only recently has this issue started to appear in the academic literature, when scholar Brian Etheridge coined the term “memory diplomacy” (

Etheridge 2008). In his research, Etheridge defends the idea that the mechanism of public diplomacy has the potential to accommodate competing political narratives about the past in direct support of broader foreign policy goals of the present.

3. A Bicentennial Show of American Art for Bonn

Curiously enough, USIA had no initial intentions of celebrating the Bicentennial abroad. It was West Germans’ idea to organize the Bicentennial celebrations in their country to demonstrate their loyalty to America. As the retired USIA officer Baker puts it: “The Germans took the lead by organizing dozens of major public events to honor the U.S. partly for our key role in German defense but also for our help to rebuild their country after WWII” (

Baker 2011). By participating in the celebration, West Germans sought to show their appreciation and support for the American people, especially after the embarrassing Watergate scandal and the Vietnam imbroglio. At the same time, West Germans wanted Americans to recognize their efforts in organizing the Bicentennial celebration. As Baker suggests: “Because I worked with our Cultural Centers across Germany, in 1975 I received dozens of requests from all over the country for Embassy representation at German celebrations of our Bicentennial” (

Baker 2011). Seeing a huge public interest in the event, the government of West Germany located in Bonn asked the U.S. government to organize some activities on its own to counterbalance the local initiatives put together by West Germans. According to Baker, the U.S. embassy in Bonn had no choice but to organize its own celebration of the Bicentennial at the request of West German officials. As he recalls: “I felt the American Embassy had to put on a big Bicentennial show of its own in Germany; otherwise inaction by us would seem to snub out hosts’ generous celebrations” (

Baker 2011).

Organizing a Bicentennial show on short notice seemed a difficult task due to a limited budget and a lack of time and staff available. From Baker’s perspective, the cheapest way to celebrate the Bicentennial in West Germany was “to organize an important American art exhibition in Bonn and publicize it well” (

Baker 2011). So, he himself suggested the idea of the

200 Years of American Painting exhibition to Ambassador Martin Hillenbrand. As Baker admits: “I used that grab bag theme because I knew all the best American paintings were already committed to Bicentennial shows in the U.S. or Europe. By using such a general theme, I hoped we could still scrape together some good works despite our late start” (

Baker 2011). Ambassador Hillenbrand signed off on Baker’s exhibition proposal. Nevertheless, USIA’s officers in Washington D.C. refused to endorse Baker’s initiative due to the tight deadlines it implied. In March 1976, Ambassador Hillenbrand “became alarmed at the flood of requests he had received directly, asking him to speak at German Bicentennial celebrations” (

Baker 2011). Consequently, he instructed Baker to send his exhibition proposal to USIA’s headquarters again accompanying it this time with a strong support letter. As a result, USIA agreed to the idea of the

200 Years of American Painting exhibition from 30 June to 1 August 1976. The bureaucracy allocated

$40,000 to the show and allowed Baker to hire one German assistant, whose name was Michael

2, “to help with the huge number of details in creating the show and putting it across in German media as a major event” (

Baker 2011).

On Baker’s note, after getting “the OK” from Washington D.C., he rode around “sleepy Bonn on Sundays” on his bike “looking for likely exhibition sites” (

Baker 2011). Out of all the multiple cultural sites in Bonn, Baker was interested in one museum in particular—the Landesmuseum Bonn. As he admits, this museum “seemed the best pick as it was professional, centrally located and had a large temporary exhibition space” (

Baker 2011). Although Baker’s words are true, we should still point out that the Landesmuseum, although, indeed, a large museum located in the very center of Bonn, historically, has nothing to do with art. It is mainly famous for having a huge collection of ancient artifacts that date back to Roman times. The Landesmuseum has never defined itself as an art museum. Moreover, all major museums in Bonn are located in the so-called Museumsmeile, a special district to the south of Bonn close to the German Parliament and the United Nations office. We tend to think that Baker chose the Landesmuseum as a location for his exhibition because no other museum in Bonn had a hiatus in the special exhibitions schedule and could not afford to host Baker’s Bicentennial art show.

The Landesmuseum was very pleased to host the show of American art commemorating the U.S. Bicentennial. As Baker recalls, the newly created political tie made the museum’s director “happy to cooperate as much as possible” (

Baker 2011). The collaboration with the Landesmuseum also suited well the interests of Ambassador Hillenbrand who was preoccupied with only one issue: for him, as the exhibition had a clear objective to respond to the German interest in the celebration of America’s Bicentennial, the exhibition needed to take place in any location and any form. For reasons unknown to us, after the Landesmuseum had confirmed its availability to host the exhibition and Baker, in turn, had reported about this decision to Washington D.C., USIA’s senior staff decided to give a grant to the Baltimore Museum of Art to mount

200 Years of American Painting. It remains a mystery why USIA chose the Baltimore Museum of Art and excluded Baker and the American Embassy in Bonn from the further planning of the exhibition.

With the Baltimore Museum being involved in the preparation of the art show, all negotiations about the Bicentennial between USIA’s headquarters in Washington D.C. and the U.S. diplomatic mission to West Germany were suspended. So, neither the American Embassy in Bonn nor the Landesmuseum could supervise or influence the decisions of the curators at the Baltimore Museum of Art responsible for the preparation of 200 Years of American Painting. Baker received the exhibit in its final configuration several weeks before the exhibition’s opening. As he writes:

Safely in Bonn with the paintings, we discovered a new problem when the crates were unpacked. The museum staff members were upset, while I was furious to learn that twelve of the paintings had arrived unframed with only ten days to hang the exhibit before it opened. A telegram to Washington brought extra money especially to hire and bring down skilled artisans from Hamburg. They framed the paintings with a few days to spare.

Despite all the organizational difficulties,

200 Years of American Painting was inaugurated on time. The catalogue published in the German language

3 served as a means of effective public presentation of the exhibition to the German audience. As Baker noted, “a handsome catalogue was the centerpiece of the plan to make a media splash across Germany” (

Baker 2011). Besides the exhibition itself, the catalogue intended to let the Germans know that the U.S. government appreciated and honored their celebration of the Bicentennial. As a result, the first part of the catalogue accompanying

200 Years of American Painting took the form of a political statement rather than that of a classic museum-like exhibition catalogue. It is no surprise that this first part was written by professional diplomats rather than the curatorial staff. Baker recalled:

Our excellent staff art expert, Dr. Dorothea Von Stettin, was assigned to draft prefatory art notes for signature by the Ambassador while I drafted for the White House a short preface for signature by President Gerald Ford. The wording was approved, and the President’s remarks appeared at the front of the catalogue. Those prefaces stressed German-American amity and the many connections between our countries in art as well as politics.

Apart from explaining the political context of the event, the catalogue likewise provided a short art historical account of

200 Years of American Painting. First and foremost, the catalogue revealed the name of the curator who mounted the exhibition. This was Ann Van Devanter, founder of the Trust for Museum Exhibitions—a Washington, D.C.-based non-profit organization involved in the organization of museum exhibitions in the U.S. and abroad. Devanter was not a typical art historian. Appreciating her achievements in political art curating,

The Art Newspaper proclaimed Devanter as “a one-woman state department for culture” (

The Museum Exchange n.d.). She had an International Relations academic background and previously collaborated with the U.S. government on organizing international art projects. Among others, Devanter had held the position of director of special partnership projects for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and had been the head of the U.S. delegation to the International Festival of Painting in Cagnes-sur-Mer in France. The choice of Devanter as curator of

200 Years of American Painting seems to be an attempt to internationalize the activities of some prominent American art institutions whose scope of cultural-political engagements was limited to U.S. domestic cultural policy only. In the case of the NEA in particular, this institution did not play a big international role during the Cold War since its governing body, the National Council on the Arts, “established a long-term policy of rejecting the funding of international exhibits by the NEA because it did not wish to duplicate the efforts already underway by the State Department and USIA” (

Binkiewicz 2004, pp. 115–16).

Besides the name of the curator, the catalogue disclosed a second important piece of information—the contents of

200 Years of American Painting, which Baker described as “a scratch history of American painting from Benjamin West to Ellsworth Kelly” (

Baker 2011). Interestingly, the catalogue’s brief history of American painting was written not by Devanter but by the director of the National Collection of Fine Arts Joshua Taylor. This detail confirms that the role of Devanter in the preparation of the exhibition was purely political. We assume that whereas Devanter worked on the international public appeal and political correctness of the show, Taylor cared more about its art historical coherence. According to the catalogue (

Taylor 1976), the exhibition featured 59 paintings by 59 different American artists, with the section on post-World War II American art regrouping 20 distinct artists.

Table 1 provides an overview of the American post-World War II art section of

200 Years of American Painting.

As the above-presented table suggests,

200 Years of American Painting displayed post-World War II American art in chronological order. The earliest painting was

The Unattainable (1945) by Arshile Gorky and the latest one was

Blue, Yellow, Red (1971) by Ellsworth Kelly. Such a curatorial approach is rather dubious for several reasons. From the standpoint of formalist Art History, exhibiting artworks by their year of creation does not make any aesthetic sense. Mixing different artistic styles, such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Realism, Minimalism, etc., deprives the exhibition of the art historical meaning, as a viewer does not see the art historical transition from one artistic movement to another. Furthermore, positioning artworks in chronological order is pointless because this approach does not highlight the artistic milestones of a specific historical era. It mixes the late works of older artists and the early works of younger artists without bringing two different generations into connection with each other. The logic of a chronological exhibition order might be even regarded as counter-productive, as it distorts the real development of post-World War II American art in two respects. Firstly, it does not show the transition of American art to the avant-garde. In other words, it does not make a distinction between American pre-modern, modern, and post-modern art. Secondly, it does not reflect the domination of Abstract Expressionism over all other contemporary American art movements that prevailed in the U.S. public diplomacy circles during the Cold War (

Guilbaut 1983;

Obadia 2019).

4. Place of Andy Warhol’s Silver Liz in 200 Years of American Painting

In the rather incoherent presentation of post-World War II American art in

200 Years of American Painting, Andy Warhol’s

Silver Liz5, which represented a silver monochrome double-paneled portrait of the famous American actress Elizabeth Taylor, was placed between two Abstract artworks—

Two Women by Willem de Kooning and

Oasis by Helen Frankenthaler. Other Pop artists present in the show, such as Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, and Roy Lichtenstein, were also isolated from one another. Consequently, the German visitors who attended the exhibition could not get a clear vision of the fundamental values and ideas of American Pop Art due to the presentation of the exhibition’s contents in chronological order. Instead, they were offered a vision of post-World War II American art as a combination of separate images taken out of their natural cultural-historical context.

We tend to think that Andy Warhol’s work was exhibited in the Bicentennial celebration without the artist’s knowledge

6. Neither do we know for sure why and how

Silver Liz was selected for

200 Years of American Painting. We assume that this artwork made it to the Bicentennial exhibition because it demonstrates per se a distinct pairing of politics and popular culture in the U.S. In fact,

Silver Liz contains a hidden political message. The artwork reflects Warhol’s captivation with the blurring boundaries between “political stumping grounds and star-studded circles”, where “politicians and actors can change their personalities like chameleons” (

Weekes 2008). Warhol has once famously noted: “Does the President of the United States ever feel out of place? Does Liz Taylor? Does Picasso? Does the Queen of England? Or do they always feel equal to anyone and anything?” (cited in

Colacello 2011). Warhol’s quote suggests that, in the era where the mass media have a powerful effect on the formation of political attitudes (

Parenti 1986), popular culture embedded in the industry of entertainment can contribute to the advancement of political events and ideas (

Twombly 2019). This means that apolitical culture does not exist anymore: all cultural products are to this or that extent political. This last point is true for Warhol himself. Although Warhol’s official position was political neutrality, he leaned towards supporting the Democratic Party. In the 1970s, Warhol was actively involved in U.S. domestic politics. On behalf of the Democratic National Committee, he assisted the Democratic nominees in the presidential campaigns of 1972 (Warhol created the

Vote McGovern (

Powers 2012) series of prints) and 1976 (Warhol painted a series of portraits of Jimmy Carter

7).

Irrespective of the intentions that the organizers of

200 Years of American Painting had in mind, Warhol’s

Silver Liz was an important piece of art that delivered one vital message to the German audience: it showed a person viewed as an American popular culture icon, the renowned Hollywood actress Elizabeth Taylor, who represented the best of American national cultural achievements of the twentieth century. Undoubtedly,

Silver Liz is viewed today as “one of the most celebrated and acclaimed paintings of Andy Warhol’s entire career” (

Christie’s 2015). For Warhol, Elizabeth Taylor epitomized the artist’s idea of a Hollywood celebrity and, therefore, an American Pop icon: she was rich, famous, and attractive, yet her personal life was rather tragic. By the time Warhol painted

Silver Liz, the actress, already an Oscar winner and the highest-paid actor in Hollywood, was about to divorce her fourth husband and recently recovered from a life-threatening infection. This “peculiar blend of glamour, scandal and illness that plagued Elizabeth Taylor throughout her life made her the ultimate muse for Warhol” (

Christie’s 2015) who depicted the actress at the height of her glamorous career.

If regarded as an American cultural icon,

Silver Liz can be treated as both a metaphor and an image. Icon-metaphors are “powerful artifacts, capable of demanding unswerving devotion and provoking fierce battles” (

Boime 1998, p. 6). They create meanings “infinite in extension, because they are circumscribed within debate in relation to national identity and historical memory” (

Boime 1998, p. 7). Icon-images lie at the core of the study of art history. They serve “as a point of departure for further investigation and decoding of images within a larger complex of cultural, social, and political values called iconology” (

Boime 1998, p. 2). At the same time,

Silver Liz is not just any icon-metaphor or icon-image. It is a metaphor for the Sixties American popular culture and an image of American Pop Art. As a metaphor for the Sixties American popular culture,

Silver Liz discloses that, by the 1960s, the mass media completely dominated the experience of most Americans. It implies that the Sixties were the decade when “the spectacle of images and commercial simulations became more prevalent and real that the things they appeared to depict” (

Carlin and Fineberg 2005, p. 169). In turn, as a Pop Art image,

Silver Liz “helps us understand that everything we see and touch in late-20th-century America is a sign divorced from nature and that each sign can be interchanged with any other sign because we all live on the surface of a one-dimensional visual culture” (

Carlin and Fineberg 2005, p. 177). Being either a metaphor or an image, Warhol’s portrait of Elizabeth Taylor communicates the prose of pop imagery as such. As art historians Nicolas Calas and Elena Calas suggest, Pop Art “at its best is written in excellent prose”: its imagery “accommodates aggression by cultivating a cool attitude on occasion bordering on the grotesque or the burlesque” (

Calas and Calas 1971, p. 83).

Despite the curatorial pitfalls of

200 Years of American Painting, the German public was positive about the exhibition. As Baker writes: “National German television covered the exhibit. Only a handful of the distant editors we invited actually attended, but almost 150 magazines and newspapers carried spreads on the event and on the exhibit” (

Baker 2011). We cannot confirm or reject Baker’s words, as we have not found any confirmation in the archives. Neither can we trace the reaction of the German public to Warhol’s

Silver Liz. We tend to think, however, that even if the German public had a positive reaction to the exhibition,

200 Years of American Painting still did not contribute too much to the improvement of the overall image of the U.S. abroad. According to historian Todd Bennett, “the Bicentennial’s effect seemed far less spectacular with the passage of time” (

Bennett 2016, p. 720). A survey of Western European public opinion conducted by USIA in July and August 1976 revealed that the celebration of the Bicentennial in Europe “had a negligible impact” (

Bennett 2016, p. 720). Fifty-seven percent of West Germans and 38% of French “expressed high opinions” of the U.S., and those figures “represented noticeable jumps” from the previous survey of 1973 (

Bennett 2016, p. 720). At the same time, only 34% of Britons approved of U.S. foreign policy, which was even lower than the previous low recorded in 1971 (

Bennett 2016, p. 720).

As USIA’s analyst Leo Crespi would conclude later in 1978: “Almost all the opinions the [field] officers heard or read were by way of offering congratulations to the US on the occasion of her 200th birthday. But birthdays felicitations need not add up to fundamental favorable orientations” (cited in

Bennett 2016, p. 720). Otherwise speaking, American public diplomats “got swept up in the patriotic fervor” and allowed themselves to believe that the common celebration of the Bicentennial with the Europeans could magically solve America’s image problem in West Europe, “when in fact it had not” (

Bennett 2016, p. 720). Reflecting on the good works the American Revolution performed in the world, the Bicentennial represented a desperate public diplomacy attempt to rebrand the U.S. in the eyes of the world, to “recapture some of the country’s moral authority, its soft power, lost in Indochina” (

Bennett 2016, p. 721). Although the commemorative public diplomacy initiatives provided a bright spot in a dispiriting decade for U.S. foreign policy, they nonetheless could not fix all of America’s reputational problems worldwide.

5. Conclusions

All in all, despite the international political salience of the U.S. Bicentennial, the inclusion of Andy Warhol’s

Silver Liz in

200 Years of American Painting had very little effect either on the further global circulation of Warhol’s art or Warhol’s artistic career. The very painting of Liz Taylor shown in Bonn was never exhibited afterward. The Bicentennial was so far the last occasion on which this artwork appeared in public both in the U.S. and abroad. Before the show in Bonn, however, the

Silver Liz under consideration had been displayed at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles in 1963, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in 1965, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston in 1966, the Solomon Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1966, and the Pasadena Art Museum in 1970. As for the history of its provenance, we know that at the moment of running

200 Years of American Painting,

Silver Liz belonged to the American art dealer Holy Solomon. Notwithstanding, Solomon did not commission this painting to Warhol. The artist conceived

Silver Liz for the Ferus Gallery as part of a series of Elizabeth Taylor portraits. Later, the Ferus Gallery sold this painting to the Leo Castelli Gallery, which, in turn, sold it to Holy Solomon, who sold it to Melvyn Estrin from Maryland (

Frei and Printz 2002, p. 400). In May 2010, Estrin sold the painting to an anonymous collector at Christie’s New York for over

$18 million (

Christie’s 2010), who in 2015 resold it at the same auction to another anonymous collector for over

$28 million (

Christie’s 2015).

Even if

200 Years of American Painting was a marginal international event for the global promotion of Andy Warhol’s Pop Art, it was still a successful U.S. cultural diplomacy initiative. In sum, the exhibition exerted two kinds of international political impact. Most importantly,

200 Years of American Painting demonstrated Germany’s dependence on America in not only political-military but also cultural terms. As art historian Catherin Dossin notices, in the 1970s the American press “started to discuss what was seen as a surprising new phenomenon, the German craze for American pop art” (

Dossin 2011, p. 100). Indeed, as famous German art critic Andreas Huyssen writes, since the mid-1960s “a wave of pop enthusiasm swept the Federal Republic” (

Huyssen 1975, p. 77). Pop became synonymous with “the new life style of the younger generation, a life style which rebelled against authority and sought liberation from the norms of existing society” (

Huyssen 1975, p. 77). In this context, the Bicentennial show “did what it was intended to do politically. America had recognized Germany’s loyalty in a highly public way” (

Baker 2011). Since the Americanization of Germany after World War II centered around two issues, the Holocaust and the Berlin Wall, for the U.S. government, successful U.S. public diplomacy in Germany “meant the transformation of Germany’s story into a chapter of the larger American tale, a narrative in which Germans were sometimes cast as villains and sometimes as heroes but rarely as an incomprehensible ‘others’ who threatened present-day America” (

Etheridge 2016, pp. 280–81).

In addition to addressing the so-called German question,

200 Years of American Painting also emphasized the impact of the Cultural Cold War on the broader West–East European cultural connections (

Krabbendam and Scott-Smith 2004;

Arnoux 2018). In fact, after Bonn, USIA sent this exhibition to other European countries. According to

Baker (

2011), the exhibition traveled to Athens and Belgrade. According to the

Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné (

Frei and Printz 2002, p. 400), the exhibition traveled to Belgrade, Rome, and Warsaw. In any case, the further circulation of

200 Years of American Painting in some countries of the Communist bloc was an excellent opportunity for the Southern and Eastern European public, who was hesitant in formulating the critique of modern painting “in a situation where the value of art and the status of autonomous artworks” were threatened by the cultural policies of the Communist regime (

Piotrowski 2009, p. 257), to get to know American contemporary art in general and American Pop Art in particular. Even if “the Soviet engagement with pop art was predominately antagonistic”, the works of American and Western European Pop artists were known to Southern and Eastern Europeans, “at least indirectly, through their reproduction in books and magazines” (Crowley cited in

Morgan and Frigeri 2015, p. 29). Rare opportunities to see Pop artworks occurred as well, albeit infrequently. According to different art historical sources, the pioneering exhibition of American Pop Art featuring works by Jim Dine, Allen Jones, and Andy Warhol was held in Belgrade and Zagreb in 1966 under the patronage of the tobacco concern Philip Morris International (

Djokic 2022). Three years later the Smithsonian Institution organized

The Disappearance and the Reappearance of the Image exhibition that included works by Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol and traveled to Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Belgium (

Hopkins and Whyte 2020).