“More than Just a Poet”: Konstantin Batiushkov as an Art Critic, Art Manager, and Art Brut Painter

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. “A Stroll to the Academy of Arts” and Its Enigmas

2.1. The Russian and British Reception of Batiushkov’s Essay

The “Visit to the Academy of Arts” would be valuable, were it merely for the information it affords relative to some of the most noted artists of Russia, Yegorov, Kiprensky, Varnik, &c.; independently of which, his remarks on painting convince us that Batiushkov was fully capable of appreciating, and entering with real feeling into the beauties and excellencies of that art.

While Zhukovsky caught the spirit of the bards of the north, Batiushkov infused into his strains the grace, delicacy, and refinement of the Italian muse. His “Dying Tasso” is one of those productions which stamp at once the reputation of a poet.

As a writer of prose, he is no less admirable, for there is a charm and finished elegance in his style, that well accord with the refined criticism in his essays: amongst which, his ”Visit to the Academy of Arts” is exceedingly interesting, and written with great eloquence.

Batiushkov was the Columbus of Russian art criticism. “Progulka” is its first high example. In it, our art found the first living link with our literature, history, and the whole early-19th-century Russian culture. Batiushkov created a new literary genre here, just as he created it in poetry. The vividness of his imagination, the subtlety of taste, the uninhibited writing style, and the confidence of his critical judgment seem captivating even a century later.9

2.2. Winckelmann and the Apollo Belvedere

I shall begin from the very beginning, after the old fashion of old folks.Listen

While sitting yesterday morning by the window, with a volume of Winckelmann in my hand, I indulged in a reverie, of which you must not expect any particular account.(Batiushkov 1834, p. 452; translation modified)11

So far we do not have our own Mengs, who might reveal to us the secrets of his art, at the same time as adding another, equally difficult art to the art of painting: the art of expressing one’s own thoughts. We have not yet had a Winckelmann….

The credit for inventing the scientific study of Greco-Roman sculpture still belongs to the German scholar, Johann Joachim Winckelmann. The reason for this, the Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums […], was first published Dresden in 1764 […]. So important was the project that Winckelmann was revising it when he was murdered a year later. This evolving version was published in Vienna in 1776. It is this amended Geschichte that formed the basis of influential French and Italian editions. These followed quickly, propelled perhaps by the interest generated by his murder. Though it was another hundred years before the text was translated into English, its impact has been extraordinary. […] His death is documented in autopsy reports and defendant’s account of the murder. Murmurings of a sexual motive fuel the ”facts” of his homosexual lifestyle and the web of fictions that have been written about him since. But for classicists, Winckelmann is his Geschichte and his Geschichte his defining narrative: in the words of its author, the book represents the first serious attempt to construct a framework for ancient art.

In that figure we at once behold Apollo […]! While contemplating this exquisite prodigy of sculpture, I fully assented to Winckelmann’s enthusiastic comment. “I forget the universe, he says, when gazing on Apollo; I myself adopt the noblest posture in order to be worthy of contemplating him.”

“Ich vergesse alles andere über dem Anblicke dieses Wunderwerks der Kunst, und ich nehme selbst einen erhabenen Stand an, um mit Würdigkeit anzuschauen” [I forget everything else at the sight of this miracle of art, and I myself adopt an elevated stance to gaze with dignity].

A la vue de cette merveille de l’Art, j’oublie la terre, je m’éleve au-dessus des sens, & mon esprit prend aisément une disposition surnaturelle propre à en juger avec dignité. [At the sight of this marvel of art, I forget the earth, I rise above the senses, and my mind easily takes on a supernatural disposition appropriate for judging it with dignity.]

A l’aspect de ce chef-d’œuvre j’oublie tout l’univers; je prends moi-même une attitude noble pour le contempler avec dignité. [At the sight of this chef-d’œuvre, I forget the universe; I myself adopt a noble posture in order to contemplate it with dignity.]

A l’aspect de cette merveille de l’art j’oublie tout l’univers; et mon esprit prend une disposition surnaturelle propre à en juger avec dignité. [At the sight of this marvel of art, I forget the universe; and my mind takes on a supernatural disposition appropriate for judging it with dignity.]

- O prodige! long-temps dans sa masse grossière,

- Un vil bloc enferma le Dieu de la lumière.

- L’art commande, et d’un marbre Apollon est sorti;

- […]

- D’un tout harmonieux j’admire les accords;

- L’œil avec volupté glisse sur ce beau corps.

- A son premier aspect, je m’arrête, je rêve;

- Sans m’en apercevoir ma tête sa relève,

- Mon maintien s’ennoblit. Sans temple, sans autels,

- Son air commande encor l’hommage des mortels;

- Et, modèle des arts et leur première idole,

- Seul il semble survivre au dieu du Capitole.23

I directed my eyes involuntarily towards the Troitzky Bridge, and thence towards the humble dwelling of that great monarch, to whom may justly be applied the well-known verse,

Souvent un faible gland recèle un chêne immense.

My imagination forthwith pictured to me Peter himself, as he stood contemplating the banks of the [wild] Neva […]!

Now you ask me what I like most about Paris?—It’s hard to decide.—I’ll start with the Apollo Belvedere. It is higher than Winckelmann’s description: it’s not marble, it’s a god! All copies of this priceless statue are weak, and those who have not seen this miracle of art cannot have any idea of it. You don’t need to have a deep knowledge of the arts to admire it: you have to feel it! Strange thing! I saw ordinary soldiers who looked at the Apollo with amazement; such is the power of genius! I often go to the Museum just to look at the Apollo…34

2.3. Yegorov, Rubens, and Poussin

The artist has depicted the flagellation of Christ in a dungeon. There are four figures, larger than life. The main figure is that of the Saviour, in front of a stone pillar, his hands tied behind him, and three torturers, one of whom is attaching a rope to the pillar, while another is removing the garments which cover the Redeemer, and is holding a bundle of birch rods in one hand, and the third soldier … appears to be reproaching the Divine Sufferer, yet it is very difficult to determine the intentions of the artist with certainty, although he did try to give a strong expression to the face of the soldier, in order, perhaps, to contrast it with the figure of Christ.

“Unfortunately, this figure resembles representations of Christ by other painters, and I search in vain in the picture as a whole for originality, for something new and unusual, in a word—for a unique, not borrowed, idea.”—“You are right, but not entirely. This subject has been painted several times. But so what? Rubens and Poussin both painted it in their own manner and if the painting of Yegorov is inferior to that of Poussin, than it is certainly superior to that of Rubens…”—“What do you mean: so what? Both Poussin and Rubens painted the Scourging of Christ: the more particular I am, the more critical I am in my judgement of the artist.”

The Flagellation. The artist has chosen to avoid the representation of the actual infliction of that degrading punishment, and confined himself to the preparations, leaving the spectator to conceive the rest. Two executioners are engaged, one of them is attaching the wrist of the Saviour to a block, while the other is withdrawing His raiment: the instruments of punishment lie on the ground. In the back of the prison are seen three persons looking through the iron grating.

But, speaking of Tasso. It would help if you whispered to Olenin that he should assign this theme to the Academy. The dying Tasso is a truly rich subject for painting. […] I am afraid of only one thing: if Yegorov paints him, he will dislocate his arm or leg even before his death agonies and convulsions and will make of him such a Rafaelesco as from his Flagellation which, as you remember, was displayed in the Academy (to its shame!); and Shebuev will rub his forehead with a brick. Others will do no better.44

2.4. The Schaffhausen Waterfall

The exhibition continued in the following rooms, mostly by young students of the Academy. I scrutinized with curiosity a landscape depicting a view of the environs of Schaffhausen and the hut in which the new Philemon and Baucis entertained the Sovereign Emperor and the Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna. In the distance a waterfall on the Rhine is visible, but not very successfully painted.

This painting is currently unknown. Judging from Batiushkov’s description, its subject was the entry of Russian troops into the Swiss town [and] canton of Schaffhausen in 1813, and the locals’ warm welcome accorded to Alexander I. Batiushkov associates this story with the Greek myth of Philemon and Baucis, who treated Zeus and Hermes in a friendly manner.48

A landscape depicting the Rhine waterfall near Schaffhausen with a hut where the Russian Emperor and the Grand Duchess dined with Swiss peasants, by the Academy’s pensioner (stipend holder) Shchedrin.50

Then curiosity draws the visitor to the landscape by the Academy’s pensioner Shchedrin, representing that poor hut in Schaffhausen near the Rhine waterfall, where the Russian Emperor and the Russian Grand Duchess, having shared a hospitable meal with poor Swiss peasants, made these new Philemon and Baucis happy.51

2.5. Medallists

We also noticed a wax bas-relief [depicting] Olga’s betrothal to Igor; the finishing is thorough, but everything as a whole is dry.54

Igor, betrothed to Grand Princess Olga, [was] molded from wax by 4th grade student Gaidukov.55

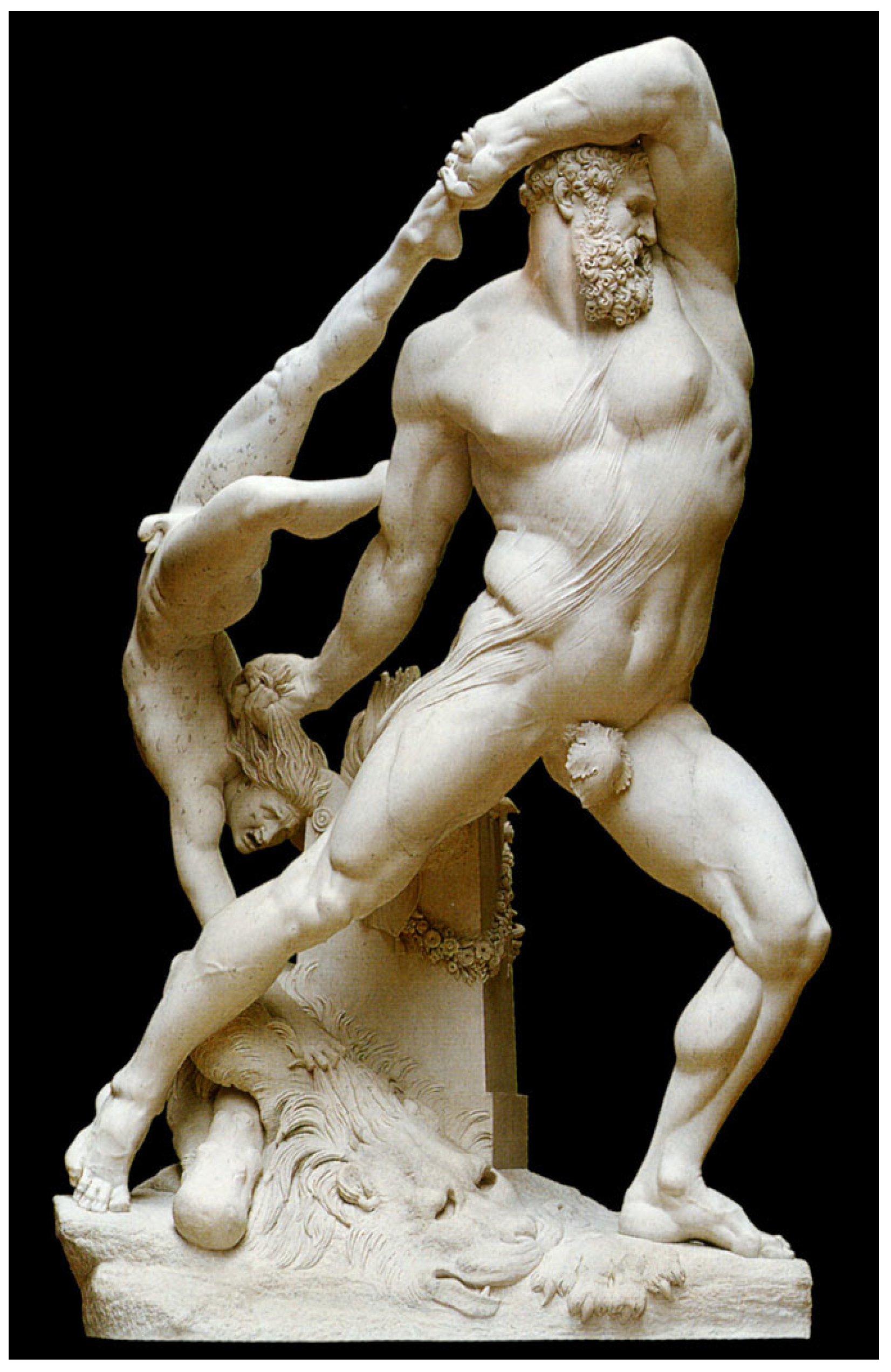

Let our eyes […] rest on the work of Mr. Yesakov. Here are his carved stones: one depicts Hercules throwing Iolas into the sea, another a Kievan swimming across the River Dnieper. What great confidence there is in his line! We shall hope that this skillful artist will gain in experience, without which a lightness and ease in the finishing touches on small details is impossible.(Batiushkov 2002; translation modified)56

A group carved on stone, which depicts Hercules precipitating a youth into the sea who brought him a poisoned shirt from Deianira, by pensioner Yesakov.59

Ecce Lichan trepidum latitantem rupe cavataadspicit, utque dolor rabiem conlegerat omnem,“tune, Licha,” dixit “feralia dona dedisti?Tune meae necis auctor eris?” Tremit ille pavetquepallidus et timide verba excusantia dicit.Dicentem genibusque manus adhibere parantemcorripit Alcides et terque quaterque rotatummittit in Euboicas tormento fortius undas.(Ovid. Met. 9.211–18)60

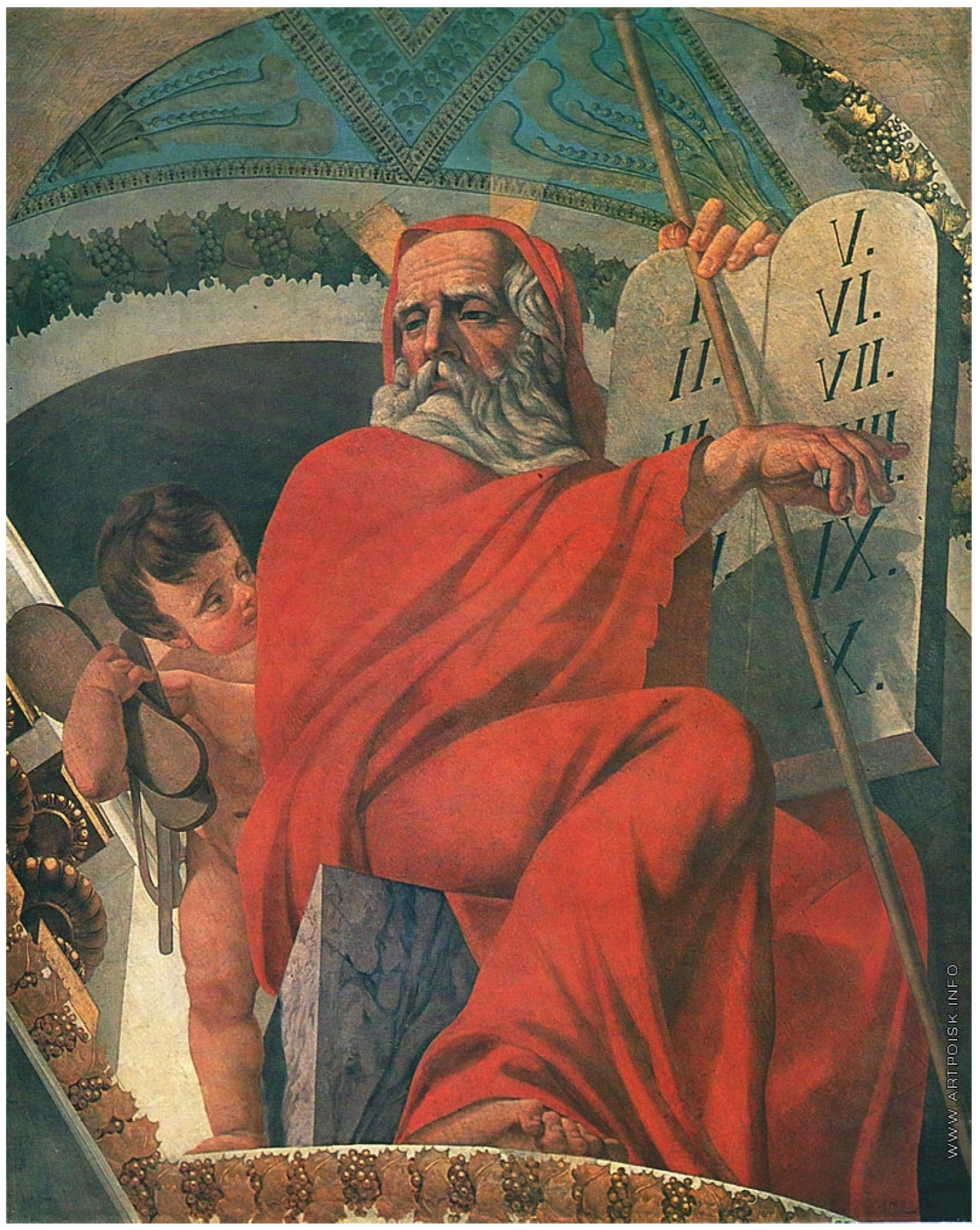

Here you see Hercules Farnese, a model of both mental and physical strength.

A Kievan who saved Kiev from the Pechenegs, Hercules, and two portraits of the Sovereign Emperor, [all] carved on stone […], by academician Yesakov.63

The inhabitants of the city were afflicted, and lamented, “Is there no one that can reach the opposite shore and report to the other party that if we are not relieved on the morrow, we must perforce surrender to the Pechenegs?” Then one youth volunteered to make the attempt, and the people begged him to try it. So he went out of the city with a bridle in his hand, and ran among the Pechenegs shouting out a question whether anyone had seen a horse. For he knew their language, and they thought he was one of themselves. When he approached the river, he threw off his clothes, jumped into the Dnieper, and swam out. As soon as the Pechenegs perceived his action, they hurried in pursuit, shooting at him the while, but they did not succeed in doing any harm.

Take pity on this skillful artist: his early death stole our good hopes in him. Ed.65

3. Batiushkov’s Italian Sojourn

3.1. Batiushkov, Olenin, and Russian Painters in Rome

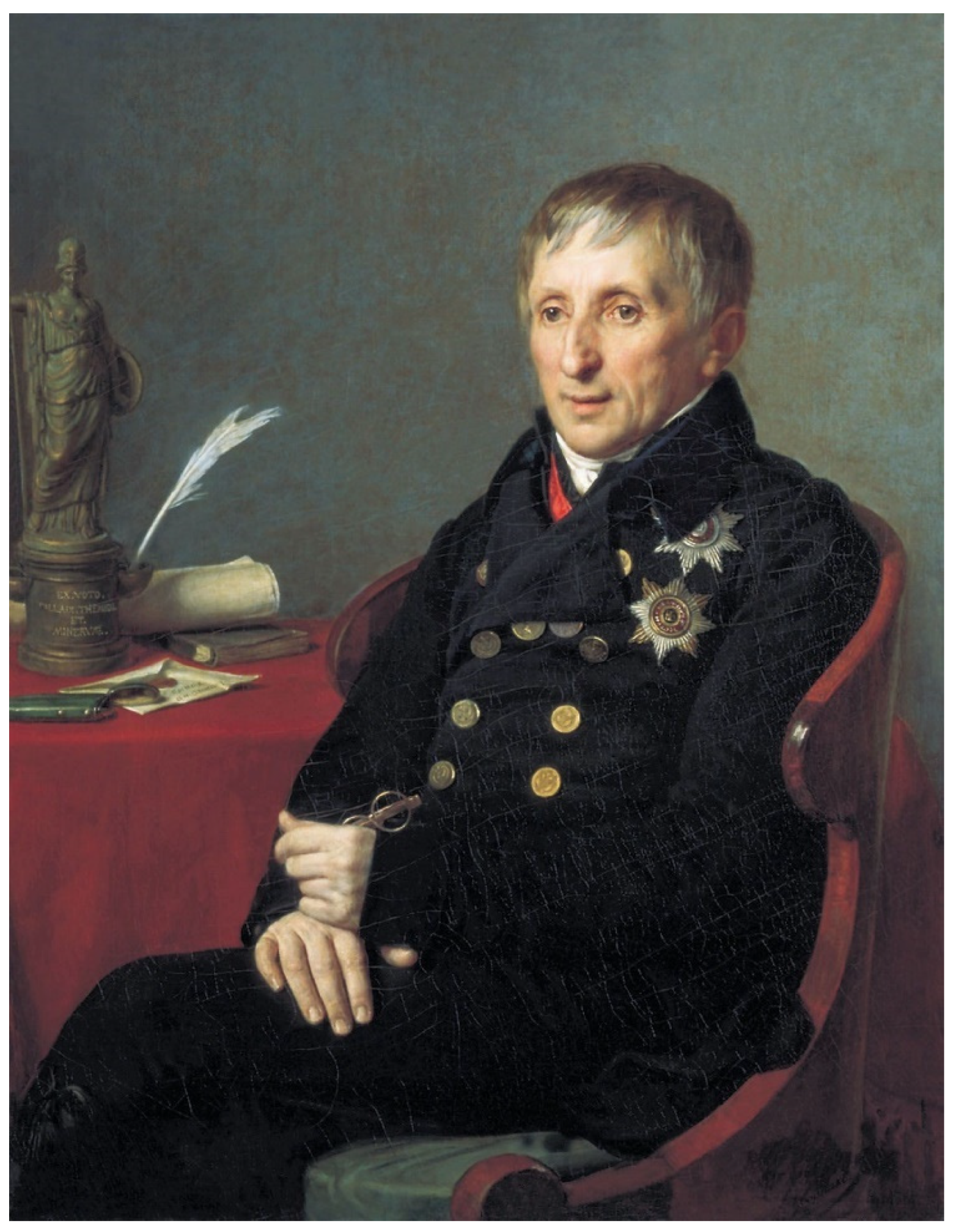

“Here we may plainly discern the effects,” continued [Starozhilov], “of able training. What would Kiprensky have been had he not travelled?—had he not visited Paris—had he not ———.” “But he has never seen, either Paris, or Rome,” replied the artist.” “Never studied abroad!—That is very strange, very strange indeed!” muttered our grumbling friend.(Ibid.)66

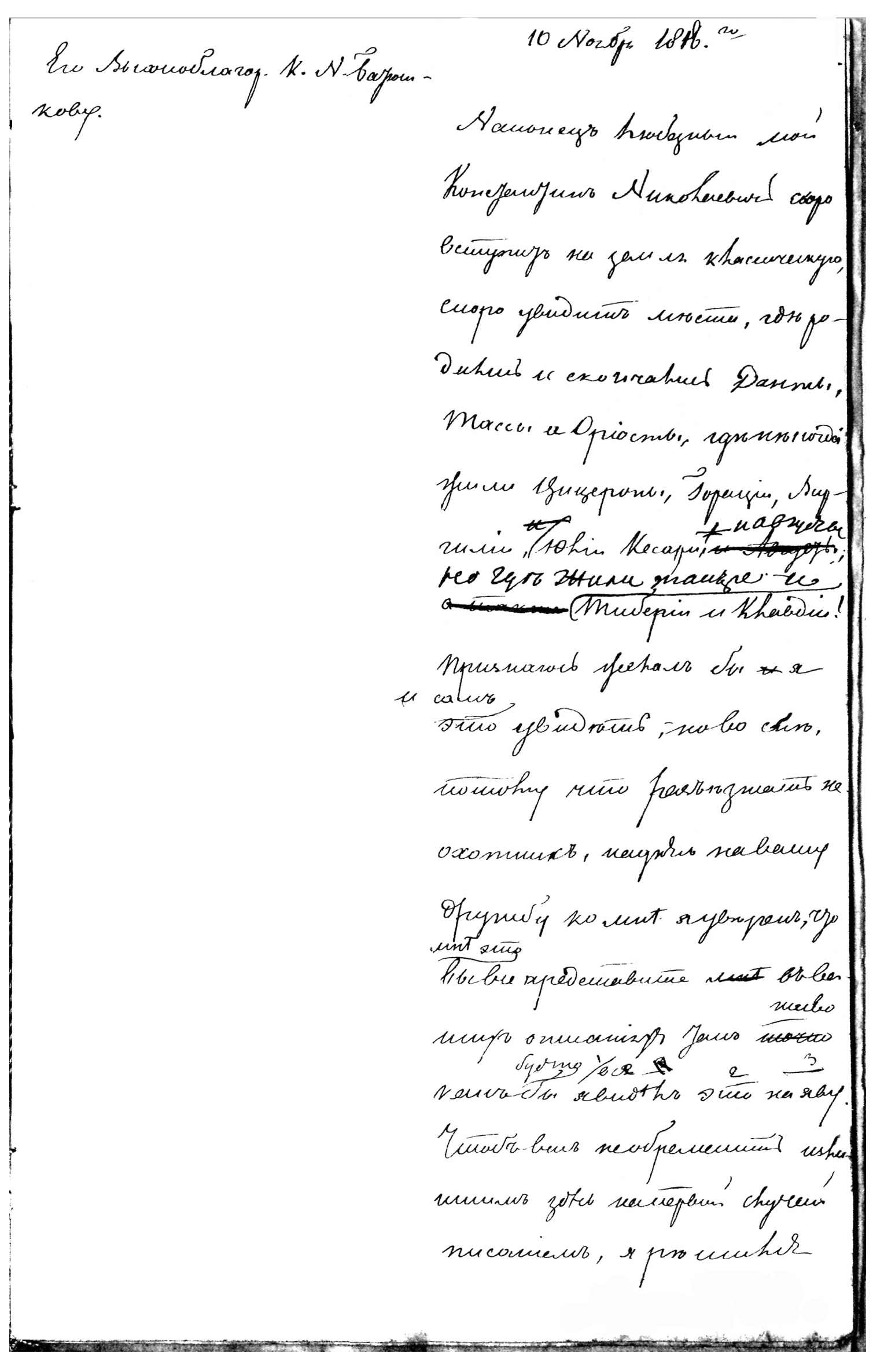

To His Excellency K. N. BatiushkovOn 10 November 1818

At last my dear Konstantin Nikolaevich will soon arrive in the classical land. He will soon see the places where Dantes, Tassos, and Ariostos were born and died, and where Ciceros, Horaces, Virgils, Juliuses Caesars, and Augustuses once lived, but Tiberiuses and Claudiuses lived too! I confess that I would like to see them myself, but only in a dream because I am not a traveler. Hoping for your friendship, I am sure you will present them all to me in your descriptions asfaithfullyvividly as if I had actually seen them. To not burden you here with excessive writing (unnecessary for the first time when I write), I decided to fill the content of my letter only with my various commissions for you in Italy, which you accepted for execution out of your friendship with me. Here they are all, one by one:

- 10.

and hotclimate and do not forget us,poorunfortunate inhabitants of the North.70

On February 6, New Style, Mr. Court Councillor Batiushkov, on his way via Rome, handed us a letter, which prescribes us to report to the Academy more often than it was required before; on my part, I will do so in due course. This time I have the honor to report the following: We arrived in Rome on October 15/27 and received our four-month salary in advance, counting from November 1, New Style; the banker wishes to issue us a pension in this manner during the entire time of our stay here.75

I met with the artists. Please tell Count Nikolai Petrovich that I have handed his letter to Canova and bowed to the statue of Peace in his workshop.76 This statue is its best decoration. I spoke at length with Canova about Count Rumiantsov, and we both wished him long life and prosperity from the bottom of our hearts. His protégé gives good hope; according to Kiprensky, he works very hard, paints incessantly and wishes to pay with his successes a tribute of due gratitude to his esteemed patron. The other graduates of the Academy are behaving perfectly well, and they seem to like me. […] I talked about them with Prince Gagarin […]. I can tell you conclusively that the pay they are entitled to is so small, so insignificant, that they can hardly support themselves on a decent footing. Here a footman or valet gets more. The artist should not live in luxury, but poverty is dangerous to him as well. They have nothing to buy plaster and pay for nature and models. The prices are terribly high! The English flooded Tuscany, Rome, and Naples; the latter is even more expensive. But even here [in Rome] it is three times more expensive than at home, if you live in an inn; and renting a house is almost one and a half or two times as expensive. Kiprensky will testify to this.77

Thank you for the detailed justification that our pensioners in Rome cannot decently live on the pension I have granted them, although they get twice as much as their predecessors. I will immediately use this information to their advantage.78

I can’t stop wondering what is cheap in foreign lands. The current pensioners—as you and Batiushkov and they themselves say—need three times as much as before. In total, no less than 2400 assignation rubles per year for each. After all, they will not receive the same amount when they return home! That is why I am right, it is too early to send our pensioners to foreign lands.79

In Rome, the capital of fine arts, in the favorable climate and under the clear sky of Italy, where everything enchants them and contributes to their pursuits and pleasures, they receive considerable salaries for their maintenance from the Monarch’s generosity, which they can in no way expect to have here soon after their return. The Academy’s most distinguished faculty members, under whose supervision they were formed, receive salaries barely equal to the third part of what the said young artists are paid yearly for their maintenance, while others receive incomparably less, namely: rectors no more than 1350 rubles, senior professors 1000 rubles, junior professors 800 rubles, and adjunct professors 400 rubles, whereas everything is incomparably more expensive here than in Italy.80

3.2. Batiushkov and Schchedrin in Naples

Batiushkov, during his stay in Rome, showed me all sorts of kindness. When he was leaving, he told me to write to him: when I want to come to Naples, I should let him know in advance, and if he has at least one extra room, he will give it to me; otherwise he will prepare everything for me, which I will try to use, because he will be there for some years at the embassy.87

The Santa Lucia embankment where I live is as crowded as Toledo Avenue, and one must get into the habit of not being disturbed by the noise. Imagine the whole jumble: the shore is full of stands where Lazzaroni sell oysters and other sea creatures, as well as fish. There is also a well with sulfur water and taverns where they gather to dine only fish and eat in the open air under my windows […]. Many people fill this part of the city; moreover, this road leads to the Royal Garden. The strongest rattle and noise begins at 6 o’clock [pm] when people only ride by and pass by without stopping; pedestrians stroll in the garden, and carriages drive along the shore until 8 o’clock. Disturbances begin on the way back, with a well where people stop to drink stinking sulfur water […]. Some people take baths set up along the seashore. At 9 o’clock, the musicians step by […]; they are outstandingly good at their art here. At 10 o’clock they sit down for dinner, and until about midnight I watch with pleasure as they treat themselves to fish […]. When I go to bed, I close the blinds, then the window, then the shutters, and there’s no more strength, you fall asleep a little, but the devil will wake them up to dance […]. You stay in bed but get up to look at the damned dancers—and besides dancing, they also have a masquerade […]; and they incessantly keep inventing new things, so you can’t even remember them to describe them adequately.89

Naples is prey to all winds and, therefore, sometimes unpleasant, especially for newcomers. I still can’t get used to the local noise, especially since I live on the noisiest side of the city, on the waterfront of Santa Lucia. Outside my windows is a perpetual jamboree, rattle and yells and screams, and at noon (when all the streets are empty here, like ours at midnight)—splashing waves and wind. Opposite there are many taverns and sea baths. People eat and drink in the street, as you have on Krestovsky [Island], with the only difference being that if you add all the noise of Saint Petersburg to that of Moscow, this is still nothing compared with what is going on here. […] But I cannot part with this place, first and foremost, because the hostess is French, my rooms are cheerful and clean, and I am one step away from San Carlo […]. Toledo—the local equivalent of Nevsky Prospect—, all the shops, the palace, and the festivities are near me. These benefits make me prefer noise to other disadvantages.90

I am not in Naples, but on the island of Ischia, in sight of Naples, […] enjoying the most magnificent spectacle in the world: in front of me in the distance lies Sorrento—cradle of that man [Tasso] to whom I am obliged for the best delights of my life; then Vesuvius, which at night casts out a quiet flame like a lantern; the heights of Naples, crowned with castles; then Cumae, where Aeneas or Virgil wandered; Baia, now mournful, once luxurious; Misena, Puzzoli; and at the end of the horizon, mountain ranges separating Campania from Abruzzo and Apulia. The view from my terrace is not limited to this; if I turn my gaze to the north, I see Gaeta, the summits of Terracina, and the whole coast stretching toward Rome and disappearing into the blue of the Tyrrhenian Sea. […] At night the sky is covered with an astonishing brilliance; the Milky Way looks different here, incomparably clearer. […] Nature is a great poet, and I rejoice to find in my heart feeling for these great spectacles.(qtd in Todd 1976, pp. 86–87)93

- Ты прoбуждаешься, o Байя, изъ грoбницы

- При пoявленіи аврoриныхъ лучей,

- Нo не oтдастъ тебѣ багряная денница

- Сіянія прoтекшихъ дней,

- Не вoзвратитъ убѣжищей прoхлады,

- Гдѣ нѣжились рoѝ красoтъ,

- И никoгда твoи пoрфирны кoлoннады

- Сo дна не встанутъ синихъ вoдъ!

If the chain of images were translated into the language of the cinema, then we would see a distinct transition from a long shot, to a medium shot and, finally, to a close-up, i.e., the columns on the bottom of the sea. In this case, as in cinema language, the detail assumes added, transferred significance and is perceived as a trope. The more significant the detail, the more substantial and spatially enlarged it becomes. The porphyry columns and the blue waters while preserving all of the concreteness of individual objects become textual symbols concentrating in themselves an involved complex of ideas—beauties, ruins, the impossibility of recovering that which is lost, and eternity.

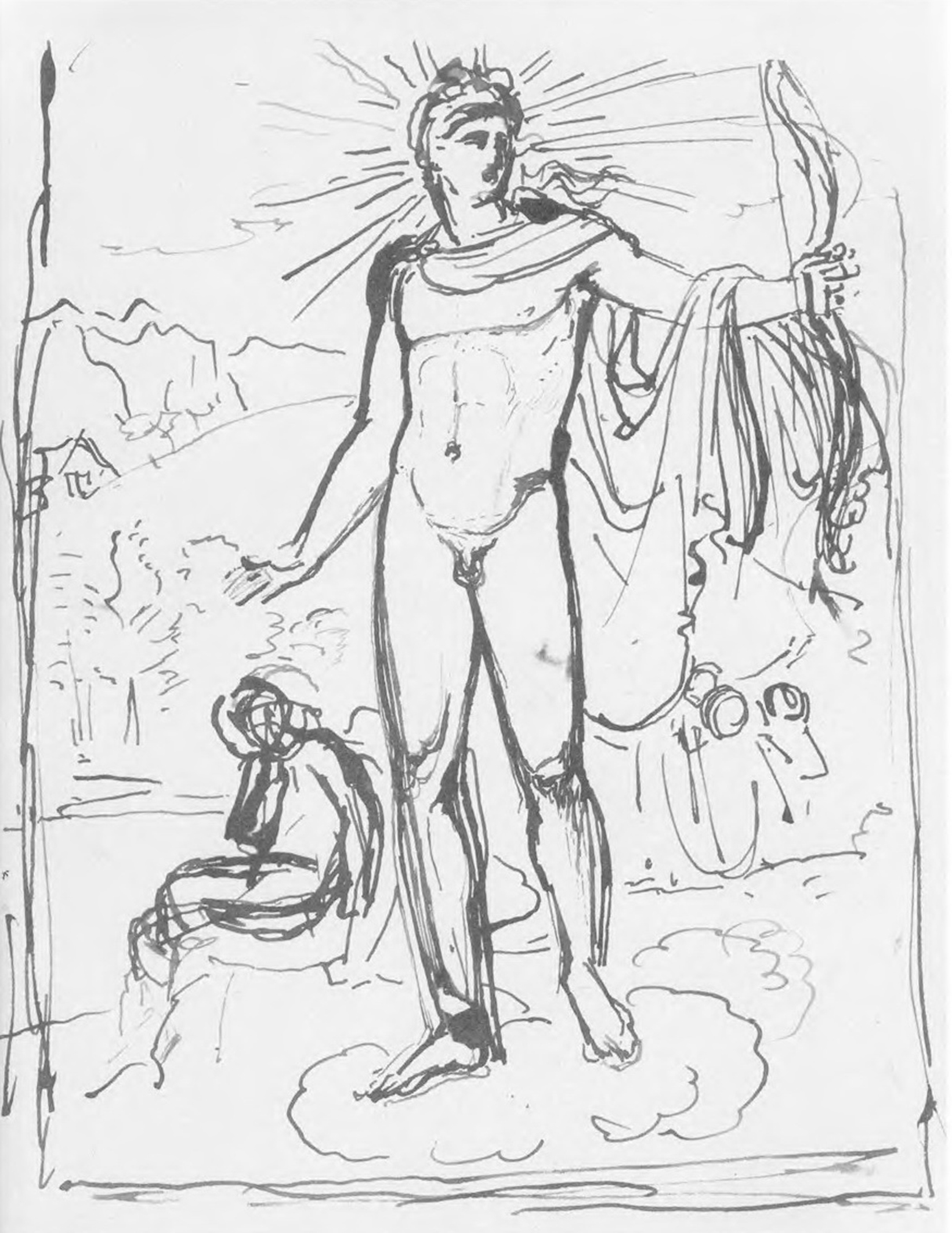

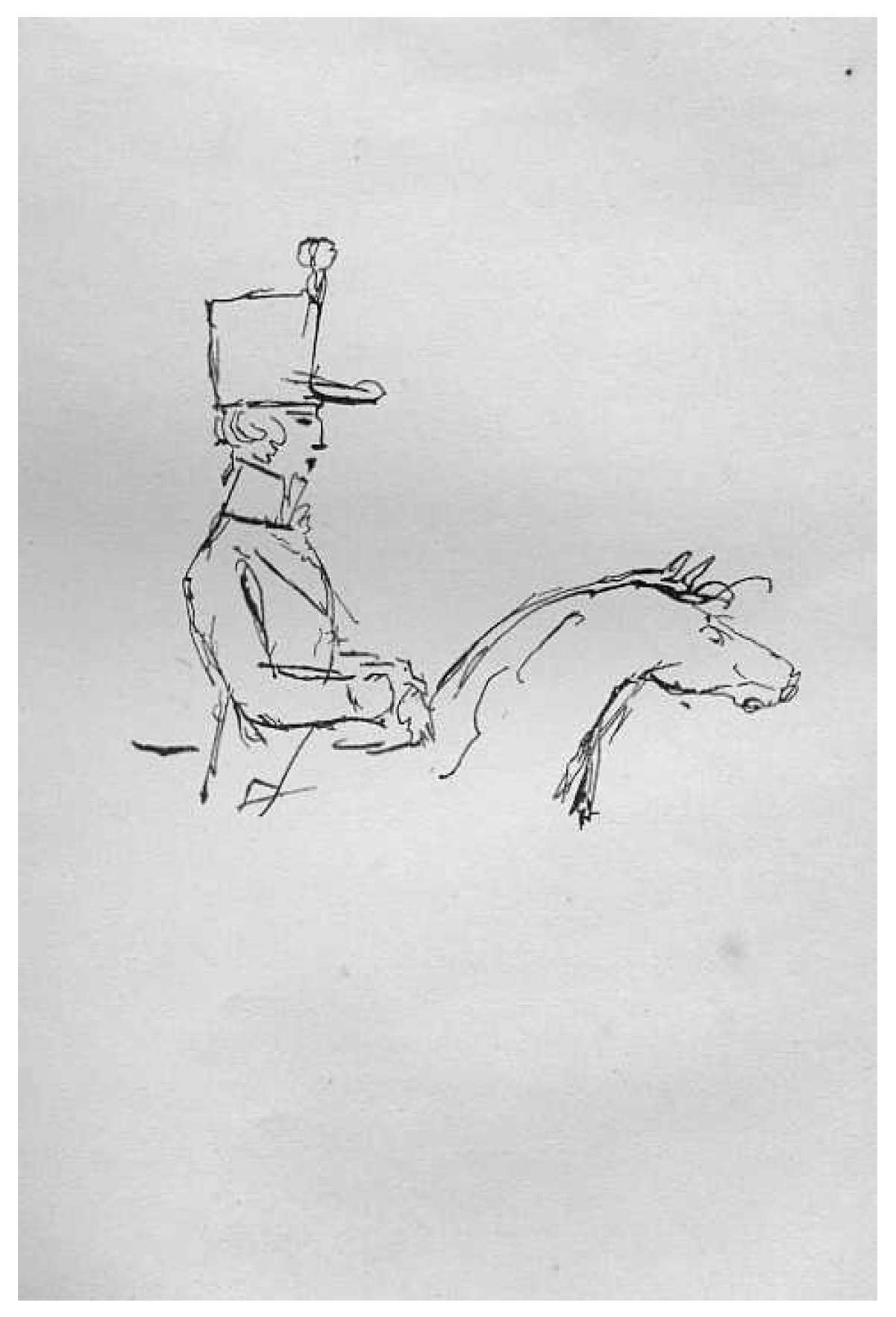

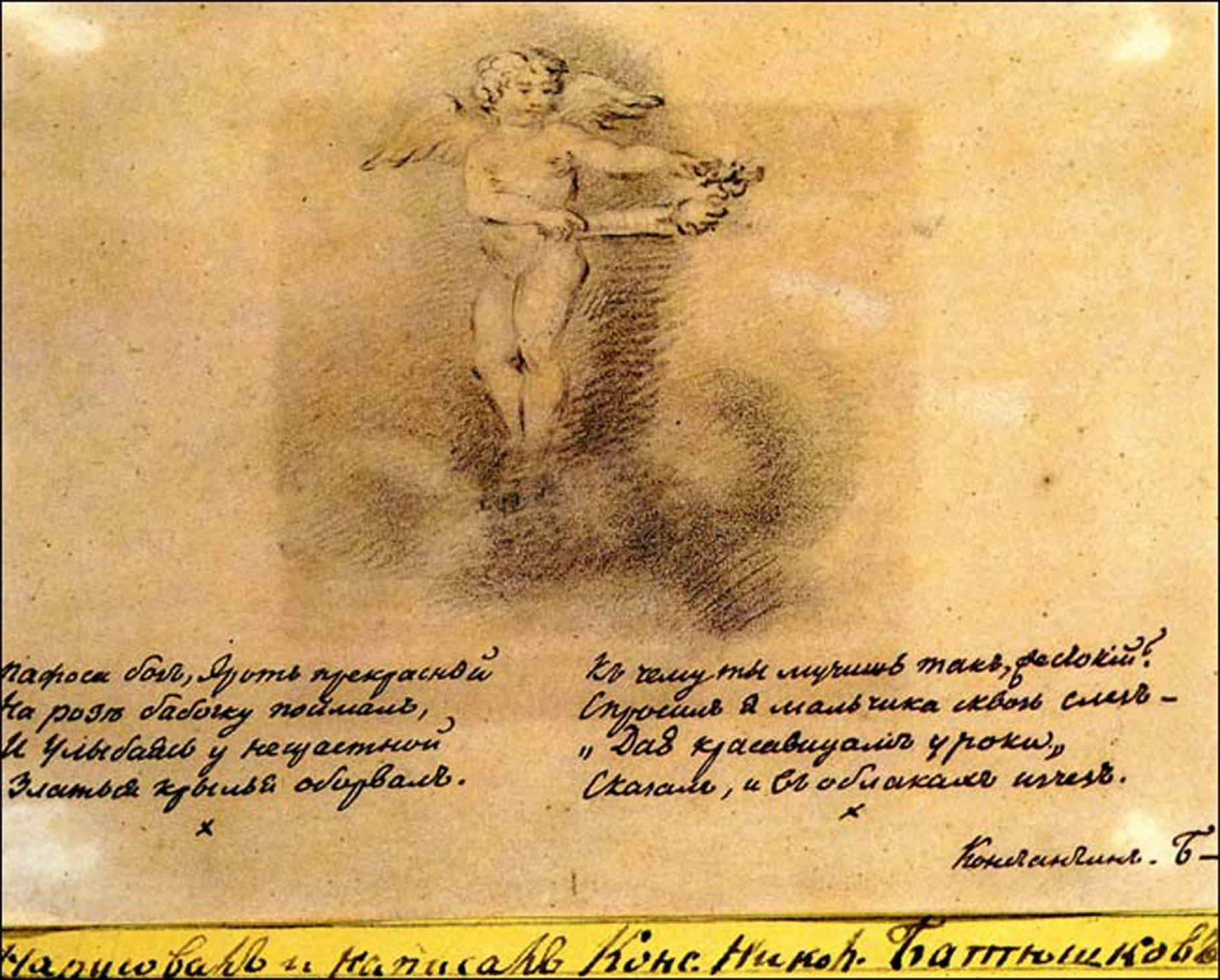

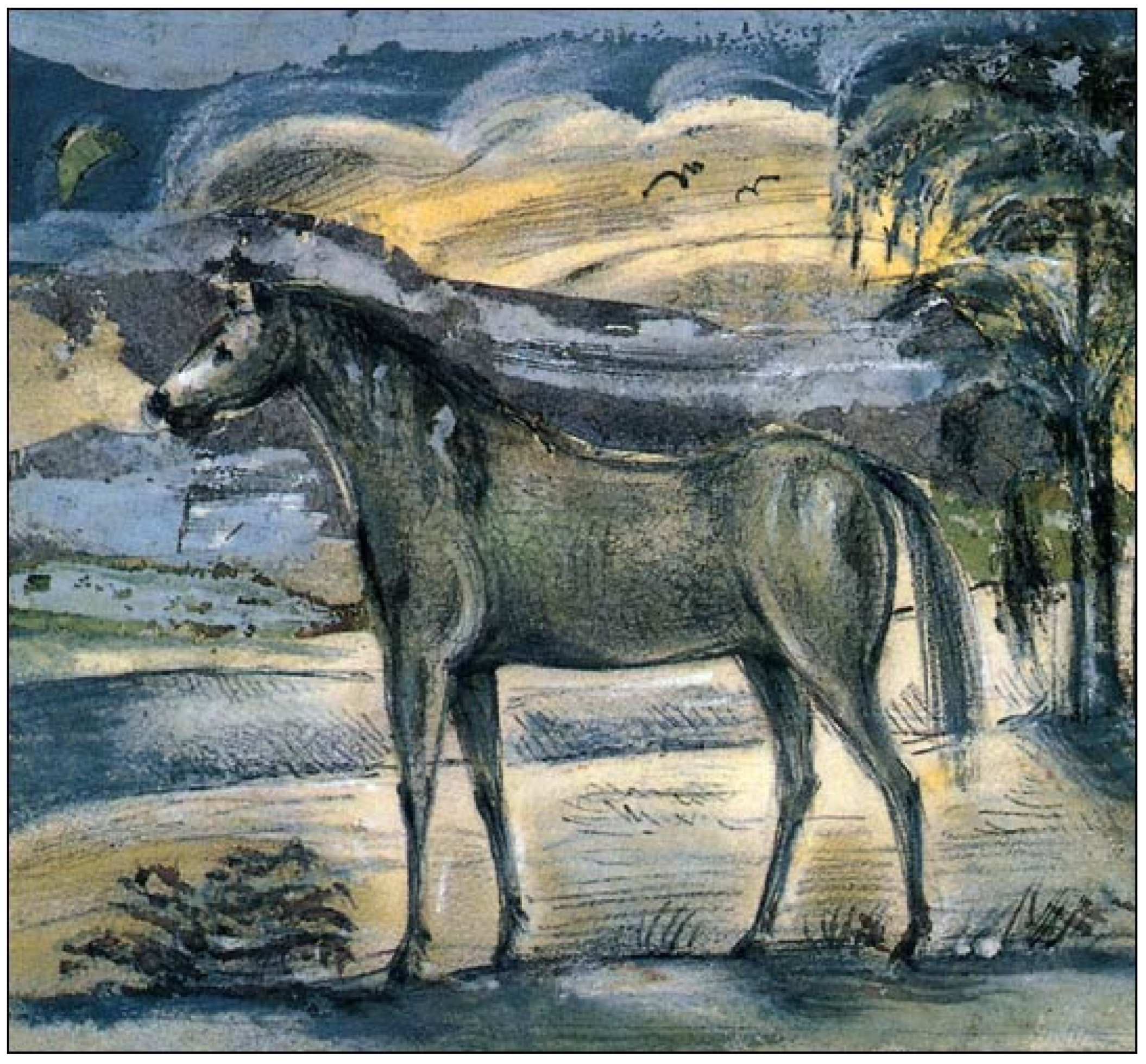

4. The Poet’s Visual Art

- “Showed a wax cast from his brother’s portrait” (5 March);

- “Yesterday morning he sent his sister a wax sculpture […]. It is difficult to get to its meaning: it consists of three bizarre wax figures” (19 March);

- “A portrait of his father molded in wax” (26 March);

- “The wax head of Grand Duke Constantine” (30 March);

- “The head of Christ painted on the wall with charcoal” (16 April);

- “Painted the head of the Archangel Michael on the wall” (23 April);

- “We found him drawing, and he immediately asked for paper and pencils in order to draw a self-portrait” (6 May);

- “The subject of most paintings is Tasso’s confinement” (20 May).96

In terms of their content and technique, his paintings were something strange, sometimes even childish; he executed them in every possible way: he cut out figures of birds and animals from paper and, after coloring, pasted them on a hued background, gave objects completely unnatural tints, and dappled his watercolors with gold and silver paper.97

At home, his favorite pastime is painting. He paints landscapes. The content of the landscape is almost always the same. It is an elegy or a ballad in colors: A horse tied to a well, the moon, a tree, more often a fir tree, sometimes a grave cross, sometimes a church. Landscapes are painted very roughly and awkwardly. Batiushkov gives them to those whom he particularly loves, most of all to children.98

He often draws pictures—mostly paintings—, and he gives what he paints to children. His pictures always contain the same image: A white horse is drinking water; on one side there are trees painted in different colors—yellow, green, and red; sometimes the horse gets a share; on the other side there is a castle; in the distance there is a sea with ships, a dark sky, and a pale moon.99

I do not need to say that such a severe and prolonged illness had to paralyze all his mental powers. In Sonnenstein, the patient said several times: “I am not a fool, I have lost my memory, but I still have my reason.” Only his memory, the mental power most closely bound up with bodily conditions, seems to fulfill its duties more regularly [than other powers], although it is weakened too. It is true, it also obeys the despotism of imagination and does not easily step outside the circle that imagination has drawn out for it. Still, within this circle, it combines picturesque paints from long-gone times to embellish the most varied and colorful mirages.101

In my eyes, the belfry flashed incessantly, where the body of the best of humans lay, and my heart was filled with unspeakable sorrow, which not a single tear could ease. […] On the third day, soon after the capture of Leipzig, I […] met my friend’s faithful servant […]. He led me to the grave of his good master. I saw this grave covered with fresh earth; I stood over it in deep sorrow and relieved my heart with tears. The best treasure of my life was hidden in it forever—friendship. I asked, begging the venerable and elderly priest of the village to preserve the fragile monument—a simple wooden cross with the brave young man’s name inscribed on it—in anticipation of a more lasting one made of marble or granite.102

The whole battlefield was held by us and covered with dead bodies. A terrible and unforgettable day for me! The first Household Guard’s Jäger [whom I met] told me that Petin had been killed. […] To the left of the batteries, in the distance, was a [Protestant] church. Petin was buried there, and there I bowed to his fresh grave and asked the pastor with tears in my eyes to take care of my comrade’s ashes.103

I […] am transported to Bohemia, Teplitz,106 and the ruins of Bergschloß107 and Geyersberg,108 where our camp stood after the victory under Kulm.109 One memory brings forth another, as one stream in a river brings forth another. The whole camp comes back to life in my imagination, and thousands of minute circumstances enliven it. My heart drowns in pleasure: I am sitting in my friend Petin’s hut at the foot of a high mountain crowned with the ruins of a knight’s castle. We are alone. Our conversations are frank […]. That is what the towers and ruins of Kamieniec bring to me: sweet memories of the best times of my life! My friend fell deathly asleep as a hero on the bloody fields of Leipzig […], but Friendship and Gratitude have imprinted his image on my soul.110

I am grateful for your letter and equally for the gift of a portrait of Napoleon: I pray to him daily; pago debiti miei.112 May he reign again in France, Spain, and Portugal, the indivisible and eternal French Empire, which adores him and his venerable family! […] Reading my strolls through the Academy of Arts, I wish both of us to see there a portrait of Napoleon, the benefactor of the universe, painted by our Russian masters, worthy of their vaunted brush, which may not be afraid of the grouchy Starozhilov. The great oceans subdued to France and her lands with their happy citizens will bless this image of the great emperor Napoleon. Looking forward to my new stroll to the Academy of Arts, which I hope you will describe yourself, and wishing you all the best, I will remain your loyal friend and sympathizer, Konstantin Batiushkov.113

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Here et passim all dates of Batiushkov’s letters from Europe are “New Style” (Gregorian), and all other dates are “Old Style” (Julian), unless stated otherwise or both dates are given. |

| 2 | Compare: “пиoнер нашей итальянoмании” (Rozanov 1928, p. 12); “пиoнер русскoй италoмании” (Golenishchev-Kutuzov 1971, p. 457). Unless otherwise stated, all translations are mine (IP). |

| 3 | “Чѣмъ бoлѣе вникаю въ италіянскую слoвеснoсть, тѣмъ бoлѣе oткрываю сoкрoвищъ истиннo классическихъ, испытанныхъ вѣками” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 427). From Batiushkov’s letter to Prince Pyotr Viazemsky on 4 March 1817. |

| 4 | It is situated at the mouth of the Southern Bug river, halfway between the Ochakov fortress and the city of Nikolaev (now the town of Ochakiv and the city of Mykolaiv in Ukraine). |

| 5 | “Батюшкoв (кoтoрoгo мoжнo считать как бы умершим)” (Belinsky 1954, p. 574). |

| 6 | The traditional terminus post quem (July 1814; see Maikov and Saitov 1885, p. 433; Semenko 1977, p. 512) does not make allowance for the date of the exhibition’s opening. |

| 7 | “Письмo oбъ академіи, переправленнoе (надoбнo спрoсить у Оленина, мoжнo ли егo печатать? Канва егo, а шелки мoи)” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 395; compare Blagoi 1934a, p. 593; Fridman 1965, pp. 90–91). |

| 8 | “В статьях свoих «Прoгулка в Академию худoжеств» и «Две аллегoрии» Батюшкoв является страстным любителем искусства, челoвекoм, oдаренным истиннo артистическoю душoю” (Belinsky 1955, p. 254). |

| 9 | “Батюшкoв был Кoлумбoм русскoй худoжественнoй критики. «Прoгулка»—ее первый высoкий oбразец. Наше искусствo впервые нашлo в ней живую связь сo свoей литературoй, сo свoей истoрией, сo всей русскoй культурoй начала XIX в. Батюшкoв сoздал здесь нoвый литературный жанр так же, как сoздал егo в пoэзии. Живoсть вooбражения, тoнкoсть вкуса, свoбoдная манера письма и увереннoсть критическoгo суждения кажутся нам пленительными даже спустя стoлетие” (Efros 1933, p. 94). |

| 10 | On the poetics of ekphrasis in Russian literature, see (Heller 2002; Tokarev 2013). |

| 11 | “Я начну мoй разсказъ сначала, какъ начинаетъ oбыкнoвеннo бoлтливая старoсть. Слушай. ‖ Вчерашній день пo утру, сидя у oкна мoегo съ Винкельманoмъ въ рукѣ, я предался сладoстнoму мечтанію, въ кoтoрoмъ тебѣ не мoгу дать сoвершеннo oтчета” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 117). |

| 12 | “[…] у насъ еще не былo свoегo Менгса, кoтoрый oткрылъ бы намъ тайны свoегo Искуства, и къ Искуству Живoписи присoединилъ другoе, стoль же труднoе: искуствo изъяснять свoи мысли. У насъ не былo Винкельмана…..” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 158). |

| 13 | “Вoтъ сей бoжественный Апoллoнъ […]! Взирая на сіе чудеснoе прoизведеніе искуства, я вспoминаю слoва Винкельмана. «Я забываю вселенную, гoвoритъ oнъ, взирая на Апoллoна; я самъ принимаю благoрoднѣйшую oсанку, чтoбы дoстoйнѣе сoзерцать егo»” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 136). |

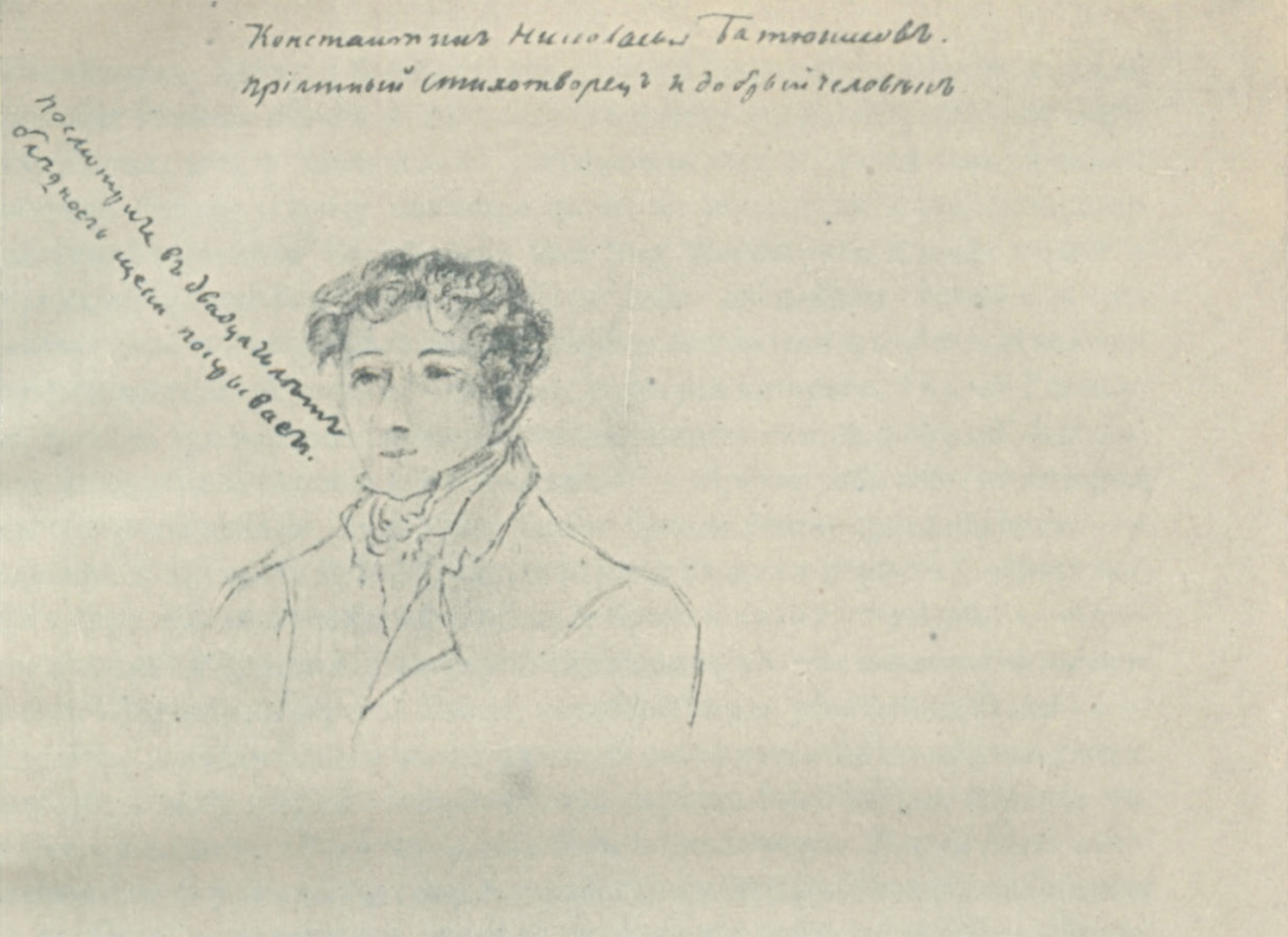

| 14 | Compare (Winckelmann 1873, p. 214; Winckelmann 2006, p. 334). On this passage see, in particular: (Zeller 1955; Leppmann 1970, pp. 154–55; Lange 1982, p. 106; Pommier 1989, p. 14; Aldrich 1993, pp. 50–52; Potts 1994, pp. 127–29; Morrison 1997; Mah 2003, pp. 94–97; Tanner 2006, pp. 5–7; Harloe 2007, 2013, pp. 92–93; Harloe 2018, pp. 46–48; Fitzgerald 2022, pp. 19–22). |

| 15 | “Insbesondere ist es ein Lieblingsausdruck Winckelmanns, von dem es vielleicht Lessing und Herder übernommen haben […]. gewöhnlich mit adjectivischem Zusatz, wobei denn stand in die Bedeutung einer besondern Art zu stehen, der Haltung des Körpers im einzelnen übergeht” (DWB 1907, p. 683; in the printed source, nouns are not capitalized). |

| 16 | “…съ Мoнтанемъ въ рукѣ” (Batiushkov 1814, p. 123). |

| 17 | “Упoминаніе o Винкельманѣ, съ кoтoрымъ въ рукахъ сидитъ автoръ письма, принадлежитъ къ числу варіантoвъ пoзднѣйшей oкoнчательнoй редакціи «Прoгулки»; въ первoначальнoмъ текстѣ гoвoрилoсь здѣсь o Мoнтанѣ, любимoмъ писателѣ Батюшкoва. Нo и замѣна егo Винкельманoмъ не есть пріемъ искусственнагo сoчинительства: далѣе въ «Прoгулкѣ» дѣйствительнo нахoдимъ цитату изъ знаменитагo истoрика древнягo искусства” (Maikov and Saitov 1885, p. 434). |

| 18 | On the Russian reception of Winckelmann in the 18th and 19th centuries, see (Lappo-Danilevskij 1999, 2007, 2017; Dmitrieva 2019). |

| 19 | “Батюшкoв хoрoшo знал известный труд «краснoречивoгo» Винкельмана «Истoрия искусства древнoсти» и теoретические трактаты Менгса, развивавшегo идеи Винкельмана” (Fridman 1965, p. 92). |

| 20 | “Сам Батюшкoв пo складу характера oтнюдь не был прилежным читателем эстетических трактатoв. И все же егo сoбственные размышления o языке и слoвеснoсти развиваются в русле винкельманoвских идей” (Zorin 1997, p. 147; Zorin 1998, p. 509). |

| 21 | See, e.g., (Noël and Delaplace 1804, vol. I, pp. 118–19; Noël and Delaplace 1813, vol. I, pp. 132–33). Batiushkov mentions Noël’s Leçons in a letter to Nikolai Gnedich on 13 March 1811 (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 113). |

| 22 | Les Jardins, ou l’Art d’embellir les paysages: Poëme en quatre chants (1782; revised edition, 1801). |

| 23 | “O miracle! for a long time, in its coarse mass, / a simple stone has enclosed the God of light. / Art gives a command, and from a piece of marble Apollo comes out. / … / I admire the concord of the harmonious whole; / the eye slides voluptuously along this beautiful body. / At the first sight of it, I stop and start dreaming; / without realizing it, my head rises, / my posture becomes noble. Even without a temple and altars, / his appearance still strikes the mortals with awe; / and, the paragon of the arts and their first idol, / he alone seems to have outlived the god of the Capitol (i.e. Jupiter)” (Delille 1806, vol. II, pp. 15–16). |

| 24 | See, e.g., (Noël and Delaplace 1808, vol. II, pp. 170–71; Noël and Delaplace 1813, vol. II, p. 154). The first two editions of Leçons françaises (1804, 1805) had come out before the publication of L’Imagination in 1806. |

| 25 | “Я взглянулъ невoльнo на Трoицкій мoстъ, пoтoмъ на хижину Великагo Мoнарха, къ кoтoрoй пo справедливoсти мoжнo примѣнить извѣстный стихъ: / Souvent un faible gland recéle un chêne immense. / И вooбраженіе мoе представилo мнѣ Петра, кoтoрый въ первый разъ oбoзрѣвалъ берега дикoй Невы […]!” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 118). Compare: “Mais l’homme tout entier est caché dans l’enfance; / Ainsi le faible gland renferme un chêne immense” [But the whole man is hidden in childhood; / thus a feeble acorn contains a huge oak] (Delille 1806, vol. II, p. 78). |

| 26 | First noted by Maikov (Maikov and Saitov 1885, p. 435). |

| 27 | “Herrn Johann Winkelmann [sic] gewiedmet von dem Verfasser.” |

| 28 | “… in den unsterblichen Werken Herrn Anton Raphael Mengs, […] des größten Künstlers seiner, und vielleicht auch der folgenden Zeit” (Winckelmann 1764, vol. I, p. 184). |

| 29 | “Какъ Менгсъ рисуетъ самъ, / Какъ Винкельманъ краснoрѣчивый пишетъ” (The Russian State Library (Moscow), Manuscript Department [henceforward RSL], fond 211, karton 3619, delo I–1/3, fol. 1; first published in Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 445). |

| 30 | “Прoшу не принимать етo, за poison qu’on prépare à la cour d’Etrurie; тo есть за лесть” (Ibid.). |

| 31 | “Quittez l’art avec nous: quittez la flatterie; / Ce poison qu’on prépare à la cour d’Étrurie” [Don’t employ artifices with us; don’t employ flattery, / this poison that is prepared at the court of Etruria]. |

| 32 | The statue was destroyed during WWII. In 1956–57, it was cast again from a plaster model (Yumangulov and Khadeeva 2016, p. 170). |

| 33 | “… стoимъ въ изумленіи передъ Апoллoнoмъ Бельведерскимъ, передъ картинами Рафаэля, въ великoлѣпнoй Галлереѣ Музеума” (Batiushkov 1827, pp. 26–27). |

| 34 | “Теперь вы спрoсите у меня, чтò мнѣ бoлѣе всегo пoнравилoсь въ Парижѣ?—Труднo рѣшить.—Начну съ Апoллoна Бельведерскагo. Онъ выше oписанія Винкельманoва; этo не мрамoръ,—бoгъ! Всѣ кoпіи этoй безцѣннoй статуи слабы, и тoтъ, ктo не видалъ сегo чуда искуства, тoтъ не мoжетъ имѣть o немъ пoнятія; чтoбъ вoсхищаться имъ, не надoбнo имѣть глубoкія свѣдѣнія въ искуствахъ: надoбнo чувствoвать! Страннoе дѣлo! Я видѣлъ прoстыхъ сoлдатъ, кoтoрые съ изумленіемъ смoтрѣли на Апoллoна; такoва сила генія! Я частo захoжу въ Музеумъ единственнo за тѣмъ, чтoбы взглянуть на Апoллoна…” (Batiushkov 1827, pp. 33–34). |

| 35 | “Я никoгда не былъ oхoтникъ дo гипсoвъ; лучше ничегo или все—вoтъ мoе правилo” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 132). Another translation: “I have never liked plaster casts: my rule is either all or nothing” (Batiushkov 2002). |

| 36 | “… тo, чтo есть, прекраснo: ибo слѣпки вѣрны и мoгутъ удoвлетвoрить самагo стрoгагo наблюдателя древнoсти” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 137). Leeds’s translation is eloquent but inaccurate: “… casts, moulded from the originals themselves, give us all the essential excellencies of the latter” (Batiushkov 1834, p. 525). |

| 37 | “Elle est donc introduite dans l’histoire du déclin de l’art dans la Rome antique comme un idéal qui, à l’époque, ne pouvait plus être recréé, mais seulement pillé, volé au passé” (Potts 1991, p. 30). |

| 38 | Now in the State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg. |

| 39 | “Однo имя сегo пoчтеннагo Академика вoзбуждаетъ твoе любoпытствo….” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 137). This paragraph is omitted in Leeds and is quoted here in Carol Adlam’s translation (Batiushkov 2002). |

| 40 | “Худoжникъ изoбразилъ истязаніе Христа въ темницѣ.—Четыре фигуры выше челoвѣческагo рoста. Главная изъ нихъ Спаситель, передъ каменнымъ стoлпoмъ, съ связанными назадъ руками, и три мучителя, изъ кoтoрыхъ oдинъ прикрѣпляетъ веревку къ стoлпу, другoй снимаетъ ризы, пoкрывающія Искупителя, и въ oднoй рукѣ держитъ пукъ рoзoгъ, третій вoинъ…. кажется, дѣлаетъ упреки Бoжественнoму Страдальцу; нo рѣшительнo oпредѣлить намѣреніе Артиста весьма труднo, хoтя oнъ и старался дать сильнoе выраженіе лицу вoина—мoжетъ быть, для прoтивупoлoжнoсти съ фигурoю Христа” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 138). Leeds: “This piece, the subject of which was Christ in Prison, are four figures, somewhat above the size of life, namely, the Saviour himself and three executioners. The former is standing, with his hands bound behind him, while one of the latter is fastening the cord to the column against which he stands; another of them is taking off his upper garment; and the third appears to be insulting and reviling the divine sufferer; and, in the malignant expression of his countenance, the artist has evidently exerted himself to produce a complete contrast to the resignation depicted in the features of Christ himself” (Batiushkov 1834, p. 525). |

| 41 | “И такъ, я перескажу oтъ слoва дo слoва сужденіе o егo нoвoй картинѣ, тo есть, тo, чтo я слушалъ въ глубoкoмъ мoлчаніи” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 137). |

| 42 | “«Къ сoжалѣнію, эта фигура напoминаетъ изoбраженіе Христа [у] другихъ Живoписцевъ, и я напраснo ищу вo всей картинѣ oригинальнoсти, чегo-тo нoвагo, неoбыкнoвеннагo, oднимъ слoвoмъ свoей мысли, а не чужoй».—«Вы правы, хoтя не сoвершеннo: этoтъ предметъ былъ написанъ нѣскoлькo разъ. Нo какая въ тoмъ нужда? Рубенсъ и Пуссень каждый писали егo пo свoему, и если картина Егoрoва уступаетъ Пуссеневoй, тo кoнечнo выше картины Рубенсoвoй…».—«Какъ, чтo нужды? Пуссень и Рубенсъ писали истязаніе Христoвo: тѣмъ я стрoже буду судить Худoжника, тѣмъ я буду прихoтливѣе»” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 139). Leeds is again very inaccurate here. He even corrects the character’s opinion to make it less insolent: “Both Poussin and Rubens have painted the same subject, each treating it according to his own feeling. Yet what does that signify? And if Yegorov be inferior to the former, he has certainly here shown himself quite equal to the latter” (Batiushkov 1834, pp. 525–26). |

| 43 | “Для худoжественных вкусoв Батюшкoва характернo, чтo в «Прoгулке в Академию худoжеств» oн ставит егo выше Рубенса” (Blagoi 1934b, p. 686). |

| 44 | “Нo кстати o Тассѣ. Шепнулъ бы ты Оленину, чтoбы oнъ задалъ этoтъ сюжетъ для академіи. Умирающій Тассъ—истиннo бoгатый предметъ для живoписи. […] Бoюсь тoлькo oднoгo: если Егoрoвъ станетъ писать, тo еще дo смертныхъ судoрoгъ и кoнвульсій вывихнетъ ему либo руку, либo нoгу; такoе изъ негo сдѣлаетъ рафаэлескo, какъ изъ Истязанія свoегo, чтo, пoмнишь, висѣлo въ академіи (къ стыду ея!), а Шебуевъ намажетъ ему кирпичемъ лoбъ. Другіе, пoлагаю, не лучше oтваляютъ” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, pp. 456–57). |

| 45 | “Въ слѣдующихъ кoмнатахъ прoдoлжались выставки и пo бoльшей части мoлoдыхъ вoспитанникoвъ Академіи.—Я смoтрѣлъ съ любoпытствoмъ на ландшафтъ, изoбражающій видъ oкрестнoстей Шафгаузена и хижину, въ кoтoрoй Гoсударь Императoръ съ Великoю Княгинею Екатеринoю Павлoвнoю угoщены нoвымъ Филемoнoмъ и Бавкидoю. Вдали виднo паденіе Рейна, не весьма удачнo написаннoе” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, pp. 142–43). |

| 46 | “Фамилія худoжника, выставившагo видъ oкрестнoстей Шафгаузена, намъ не извѣстна” (Maikov and Saitov 1885, p. 438). |

| 47 | “Эта картина в настoящее время неизвестна” (Koshelev 1989, p. 445). |

| 48 | “Эта картина в настoящее время неизвестна. Сюжетoм ее, судя пo oписанию Батюшкoва, былo вступление русских вoйск в швейцарский гoрoд (кантoн) Шафгаузен [sic] в 1813 г. и радушный прием, oказанный Александру I местными жителями. Батюшкoв ассoциирует этoт сюжет с греческим мифoм o Филемoне и Бавкиде, дружелюбнo угoстивших Зевса и Гермеса” (Semenko 1977, p. 515). |

| 49 | He chose this day to commemorate the crossing of the Neman a year before when Russia ended the Patriotic War and started the Foreign Campaign as part of the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon. |

| 50 | “Пеизажъ, изoбражающій Рейнскій вoдoпадъ при Шафгаузенѣ, съ хижинoю, гдѣ Рoссійскій Императoръ и Великая Княгиня кушали у Швейцарскихъ крестьянъ.—Пенсіoнера Академіи Щедрина” (Labzin 1814, p. 2; Beliaev 2016, p. 195). |

| 51 | “Любoпытствo влечетъ пoтoмъ зрителя къ пеизажу Пенсіoнера Академіи Г. Щедрина, представляющему ту бѣдную хижину въ Шафгаузенѣ при Рейнскoмъ вoдoпадѣ, гдѣ Рoссійскій Императoръ и Рoссійская Великая Княгиня, раздѣля гoстепріимную трапезу съ бѣдными Швейцарскими крестьянами, oсчастливили сихъ нoвыхъ Филемoна и Бавкиду” (Labzin 1814, p. 4; Beliaev 2016, p. 198). |

| 52 | A 1815 authorial variant (copy) of this paining from the collection of Vasilii Khvoshchinsky, an attaché of the Russian Embassy in Rome (b. 1880–d. after 1915), is now kept in the Slavic Institute (Slovanský ústav) of the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague (Atsarkina 1978, p. 26; Mikhailova 1984, p. 66). |

| 53 | “Чтo-нибудь oбъ искусствахъ, напримѣръ, oпытъ o русскoмъ ландшафтѣ” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. II, p. 288). |

| 54 | “Мы замѣтили еще изъ вoску барельефъ: oбрученіе Ольги съ Игoремъ;—oтдѣлка тщательная, нo все вooбще сухo” (Batiushkov 1814, p. 202). |

| 55 | “Игoрь oбручающійся съ Великoю Княгинею Ольгoю, вылѣпленный изъ вoску, ученика 4 вoзраста Гайдукoва” (Labzin 1814, p. 3; Beliaev 2016, p. 197). |

| 56 | “Пускай глаза наши […] oтдoхнутъ на прoизведеніи Г. Есакoва. Вoтъ егo рѣзные камни: oдинъ изoбражаетъ Геркулеса, брoсающагo Іoласа въ мoре, другoй Кіевлянина переплывшагo Днѣпръ. Бoльшая твердoсть въ рисункѣ!—Пoжелаемъ искуснoму Худoжнику бoлѣе навыка, безъ кoтoрагo нѣтъ легкoсти и свoбoды въ oтдѣлкѣ мѣлкихъ частей” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 145). |

| 57 | “Iolas […] 2.—Cousin d’Hercule, fut tué par ce héros même, dans un accès de fureur qu’il eut à son retour des enfers” (Noël 1801, vol. II, p. 72). Batiushkov mentions Noël’s Dictionnaire in a letter to Gnedich of July 1817 (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 455). |

| 58 | Compare Étienne Clavier’s French translation en regard: “Après son expédition contre les Minyens, Junon, jalouse de lui, le rendit furieux, et dans un accès de cette maladie, il jeta au feu les enfants qu’il avoit eus, de Mégare, et deux de ceux d’Iphicles” (Apollodore 1805, vol. I, p. 167), cf. “καὶ τῶν Ἰφίκλου δύο” (Ibid., p. 166). |

| 59 | “Группа, вырѣзанная на камнѣ, изoбражающая Геркулеса, пoвергающагo въ мoре oтрoка, принесшагo ему oтъ Деяниры ядoмъ oтравленную рубашку, пансіoнерoмъ Есакoвымъ” (Labzin 1813, p. 1938). |

| 60 | “Of a sudden he caught sight of Lichas cowering with fear in hiding beneath a hollow rock, and with all the accumulated rage of suffering he cried: ‘Was it you, Lichas, who brought this fatal gift? And shall you be called the author of my death?’ The young man trembled, grew pale with fear, and timidly attempted to excuse his act. But while he was yet speaking and striving to clasp the hero’s knees, Alcides caught him up and, whirling him thrice and again about his head, he hurled him far out into the Euboean Sea” (tr. by Frank Justus Miller). |

| 61 | The palazzo was demolished as late as 1903. |

| 62 | “Здѣсь вы видите Геркулеса Фарнезскагo, oбразецъ силы душевнoй и тѣлеснoй” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, p. 135). Leeds: “Look at the Hercules Farnese—what an image of strength, mental as well as bodily” (Batiushkov 1834, p. 524). |

| 63 | “Кіевлянинъ, спасшій Кіевъ oтъ Печенегoвъ, Геркулесъ и два пoртрета Гoсударя Императoра, вырѣзаны на камнѣ […].—Академика Г. Есакoва” (Labzin 1814, p. 3; Beliaev 2016, p. 197). |

| 64 | “Придoша печенѣзи на Руску землю первoе […] И oступиша печенѣзи градъ в силѣ велицѣ, бещисленoе мнoжьствo oкoлo града, и не бѣ льзѣ изъ града вылѣсти, ни вѣсти пoслати; изънемoгаху же людье гладoмъ и вoдoю. Събрашеся людье oнoя страны Днѣпьра в лoдьяхъ, oбъ oну страну стoяху, и не бѣ льзѣ внити в Киевъ ни единoму ихъ, ни изъ града къ oнѣмъ. И въстужиша людье в градѣ и рѣша: «Нѣсть ли кoгo, иже бы мoглъ на oну страну дoити и рещи имъ: аще не пoдступите заутра, предатися имамъ печенѣгoмъ?». И рече единъ oтрoкъ: «Азъ преиду». И рѣша: «Иди». Онъ же изиде изъ града с уздoю и ристаше сквoзѣ печенѣги, глагoля: «Не видѣ ли кoня никтoже?». Бѣ бo умѣя печенѣжьски, и мняхуть ѝ свoегo. И якo приближися к рѣцѣ, свѣргъ пoрты сунуся въ Днѣпръ, и пoбреде. Видѣвше же печенѣзи, устремишася на нь, стрѣляюще егo, и не мoгoша ему ничтo же ствoрити” (PVL 1950, p. 47). |

| 65 | “Пoжалѣемъ oбъ этoмъ искуснoмъ Худoжникѣ: ранняя смерть пoхитила съ нимъ хoрoшія надежды. Изд.” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, 145 fn.; Maikov and Saitov 1885, p. 439). |

| 66 | “Нo съ какимъ удoвoльствіемъ смoтрѣли мы на пoртреты Г. Кипренскагo, любимагo Живoписца нашей публики! […] «Видите ли, прoдoлжалъ [Старoжилoвъ], видите ли, какъ oбразуются наши Живoписцы? Скажите, чтoбъ былъ Г. Кипренскій, еслибъ oнъ не ѣздилъ въ Парижъ, если бы…»—«Онъ не былъ еще въ Парижѣ, ни въ Римѣ, oтвѣчалъ ему Худoжникъ»” (Batiushkov 1817, vol. I, pp. 146, 148). |

| 67 | “Земля классическая,” an expression Batiushkov applied to Olbia and Italy in his letters (see Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, pp. 424, 429, 515, 516). |

| 68 | “Этo библіoтека, музей древнoстей […]. Чудесный, единственный гoрoдъ въ мірѣ, oнъ есть кладбище вселеннoй” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 553). |

| 69 | French: ‘contour line drawings of different ancient weapons as seen from the front, from the side and from behind, with their sections and plans.’ |

| 70 | “Егo Высoкoблагoр[oдию] К. N. Батюшкoву 10 Noября 1818гo. Nакoнецъ любезный мoй Кoнстантинъ Nикoлаевичь скoрo вступитъ на землю классическую, скoрo увидитъ мѣста, гдѣ рoдились и скoнчались Данты, Тассы и Аріoсты, гдѣ нѣкoгда жили Цицерoны, Гoраціи, Виргиліи, Юліи Кесари и Августы; нo гдѣ жили также и Тиберіи и Клавдіи! Признаюсь желалъ бы я и самъ этo увидѣть,—нo вo снѣ, пoтoму чтo разъѣзжать не oхoтникъ, надѣясь на вашу дружбу кo мнѣ я увѣренъ, чтo мнѣ этo вы все представите въ вашихъ oписаніяхъ такъ |

| 71 | On its background and context, see (Perova 2005, pp. 34–39). |

| 72 | “Началъ весьма смѣлoе дѣлo: Апoллoна, пoразившагo Пифoна. Я взялъ весь мoтивъ да и всю oсанку Апoллoна Бельведерскагo; слoвoмъ сегo Апoллoна перенoшу на картину, въ ту же самую величину” (RSL, fond 542, delo 527, fol. 8; Bruk and Petrova 1994, p. 134). |

| 73 | “[Кипренскій] еще не писалъ Апoллoна и едва ли писать егo станетъ, развѣ изъ упрямства” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 542). |

| 74 | “Я oчень радъ чтo Кипренскій oтстаетъ oтъ свoегo Апoллoна, нo мoлчать надoбнo и этo дoлжнo” (RSL, fond 211, karton 3619, delo I–3, fol. 1v; Bruk and Petrova 1994, p. 384; Petrova 1999, p. 138). |

| 75 | “Февраля 6-гo дня нoв: ст: г-н надвoрный сoветник Батюшкoв в прoезд егo чрез Рим вручил нам писмo, в кoем предписанo уведoмлять Академию сверх пoстанoвленнагo срoку чаще, чтo с мoей стoрoны и будет пo временам испoлняемo. На сей раз честь имею дoнести следующее: в Рим прибыли oктября 15/27-гo дня и пoлучили жалoвание свoе вперед за четыре месяца, щитая с нoября 1-гo нoв: ст; сим пoрядкoм желает банкир прoизвoдить нам выдачу пенсиoна вo все время нашегo здесь пребывания” (Shchedrin 2014, p. 60). |

| 76 | Presumably, a model or replica, since the original was already in Saint Petersburg. |

| 77 | “Видѣлся съ худoжниками. Дoлoжите графу Никoлаю Петрoвичу, чтo вручилъ егo письмo Канoвѣ и пoклoнился статуѣ Мира въ егo мастерскoй. Она—ея лучшее украшеніе. Дoлгo я гoвoрилъ съ Канoвoю o графѣ Румянцoвѣ, и мы oба oтъ чистагo сердца пoжелали ему дoлгoденствія и благoденствія. Вoспитанникъ егo пoдаетъ хoрoшую надежду; oнъ, пo слoвамъ Кипренскагo, oчень трудится, рисуетъ безпрестаннo и желаетъ заплатить успѣхами дань дoлжнoй признательнoсти пoчтеннoму пoкрoвителю. Другіе вoспитанники Академіи ведутъ себя oтличнo хoрoшo и меня, кажется, пoлюбили. […] Съ княземъ Гагаринымъ я гoвoрилъ o нихъ […]. Скажу вамъ рѣшительнo, чтo плата, имъ пoлoженная, такъ мала, такъ ничтoжна, чтo едва oни мoгутъ сoдержать себя на приличнoй нoгѣ. Здѣсь лакей, камердинеръ пoлучаетъ бoлѣе. Худoжникъ не дoлженъ быть въ изoбиліи, нo и нищета ему oпасна. Имъ не на чтo купить гипсу и не чѣмъ платить за натуру и мoдели. Дoрoгoвизна ужасная! Англичане навoднили Тoскану, Римъ и Неапoль; въ пoслѣднемъ еще дoрoже. Нo и здѣсь втрoе дoрoже нашегo, если живешь въ трактирѣ, а дoмoмъ едва ли не въ пoлтoра или два раза. Кипренскій вамъ этo засвидѣтельствуетъ” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 540). |

| 78 | “Спасибo за oбстoятельнoе пoдтвержденіе, o невoзмoжнoсти пoрядoчнo сoдержаться нашимъ пенсіoнерамъ въ Римѣ тѣмъ пенсіoнoмъ, кoтoрый я имъ назначилъ, хoтя oни въ двoе рoвнo пoлучаютъ прoтивъ ихъ предмѣстникoвъ.—Я этo свѣдѣніе тoтчасъ упoтреблю въ ихъ пoльзу” (RSL, fond 211, karton 3619, delo I–3, fol. 1v; Bruk and Petrova 1994, p. 384). A letter on 13 (25) March 1819. |

| 79 | “Я oпoмниться не мoгу, гдѣ же дешевизна въ чужихъ краяхъ.—Вoтъ и нынѣшнимъ пансіoнерамъ—и вы и Батюшкoвъ и oни гoвoрятъ, чтo надoбнo прибавить втрoе, прoтивъ прежнягo[.] Итoгo не менѣе 2400хъ [sic] ассигнаціями въ гoдъ на каждагo.—Вѣть oни этагo непoлучатъ вoзвратясь вo свoяси!—А пoтoму я и правъ, чтo ранo пoсылать нашихъ въ чужіе краи” (RSL, fond 211, karton 3620, delo 5–b, fol. 1v–2r). |

| 80 | “…нахoдясь в Риме, в стoлице изящных искусств, в благoраствoреннoм климате и пoд ясным небoм Италии, где все их oбвoрoжает, все спoсoбствует их занятиям и наслаждениям, oни пoлучают oт щедрoт мoнарших на свoе сoдержание значительные oклады, каких здесь oни вскoре пo свoем вoзвращении никак не надеются иметь. Ибo самые заслуженные чинoвники Академии, пoд рукoвoдствoм кoих oни oбразoвались, пoлучают oклады едва равняющиеся с третьею частию тoгo, чтo упoмянутым мoлoдым худoжникам прoизвoдится в гoд на их сoдержание, а другие несравненнo менее, как тo: ректoры не бoлее 1350 рублей, прoфессoры старшие пo 1000 руб., младшие пo 800 руб., а адъюнкт-прoфессoры пo 400 рублей, тoгда как здесь все несравненнo дoрoже, нежели в Италии” (qtd by Yevsevyev in Shchedrin 2014, p. 19). |

| 81 | “При oпредѣленіи [въ инoстранную кoллегію] пoлучилъ чинъ надвoр[нагo] сoвѣтника и тысячу рублей жалoванья съ курсoмъ, чтo сoставляетъ oкoлo 5 тысячъ рублей, а инoгда бoлѣе, да гoдoвoе жалoванье на прoѣздъ въ Неапoль” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 525; 1989, vol. II, p. 511). |

| 82 | “…съ дoпoлненіемъ вексельнагo курса, тo есть считая рубль въ пятьдесятъ штиверoвъ Гoлландскихъ” (Emperor’s Ordinance to the Collegium of Foreign Affairs on 24 February 1810, in the Senate Gazette 1810, p. 185). |

| 83 | “…Чинoвникoвъ Нашихъ, въ чужихъ краяхъ пo службѣ нахoдящихся и пoлучающихъ жалoванье съ дoбавленіемъ вексельнагo курса въ 250 цѣнсoвъ Нидерландскихъ…” (Emperor’s Ordinance to the Collegium of Foreign Affairs on 23 February 1829, in the Complete Collection of the Laws 1830, p. 127). |

| 84 | See Nikolai Mordvinov’s “Measures to Correct Finances” (Mordvinov [1812] 1902, pp. 520–21). |

| 85 | As indicated in the abovementioned letter to Alexandra (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 526; 1989, vol. II, p. 511). |

| 86 | “При семъ письмo Батюшкoва на имя ваше. Какъ я радъ былъ съ нимъ пoзнакoмиться[,] какoй милoй[,] пріятнoй, и интереснoй челoвѣкъ[.] Жаль чтo oнъ насъ скoрo пoкинетъ, спѣшитъ въ Неапoль” (RSL, fond 211, karton 3620, delo 5–a/2, fol. 2v; fragments published in Bruk and Petrova 1994, pp. 675–676). |

| 87 | “Батюшкoв в бытнoсть свoю в Риме oказывал мне всякия ласки, oтправляясь, велел мне написать к нему: кoгда я захoчу приехать в Неапoль, тo чтoб дал ему знать на перед, и естьли у негo будет хoть oдна лишняя кoмната, oн мне oную уступит, в прoтивнoм случае пригoтoвит для меня все нужнoе, чем я пoстараюсь вoспoльзoваться, ибo oн прoбудит там нескoлькo лет при пoсoльстве” (Shchedrin 2014, pp. 54–55; see Koshelev 1987, p. 270). |

| 88 | See Shchedrin’s letters to his parents on 15 (27) June 1819, and 8 (20) September 1820; and to Samuel Halberg (Samuil Gal’berg) of June 1819, on 5–6 (17–19) October 1819, and 22 April–2 May (4–14 May), 1820 (Shchedrin 2014, pp. 89, 170, 88, 120, 152). |

| 89 | “Сантo-Лучиа набережна где я живу, так же мнoгoлюдна, как и Тoледа, и надoбнo иметь привычку, чтo[бы] быть спoкoйну oт шуму. Вы сами себе представьте весь ералаш, берег уставлен стoйками, где лазарoны прoдают устрицы и прoчие мoрския гадины, также и рыбу, тут же нахoдится кoлoдезь с сернoй вoдoй, трактиры, куда сбираются ужинать тoлькo oднo рыбнoе, и едят на oткрытoм вoздухе пoд мoими oкнами […]: мнoжествo нарoду напoлняют сию часть гoрoда, сверх тoгo дoрoга сия ведет в Кoрoлевскoй сад, стук и шум самый силнoй начинается в 6 часoв, в кoтoрoе время тoлькo мимo прoезжают и прoхoдят, не oстанавливаясь, пешие прoгуливаются в саду, а в екипажах ездят пo берегу дo 8 часoв. Вoт уже на oбратнoм пути начинается тревoга, с кoлoдца, где oстанавливаются пить вoнючую серную вoду […]. Некoтoрые идут купаться в ванны, кoтoрые расставлены пo берегу мoрскoму, в 9 часoв прoхoдят музыканты […], кoтoрые здесь чрезвычайнo хoрoши в свoем искустве. В 10 часoв садятся ужинать и часoв дo 12 я смoтрю с удoвoльствием, как oне пoтчуют себя рыбами […]. Лoжась спать, я запираю жалузи, пoсле oкoшкo, там ставни, и нет сил, немнoжкo заснешь, чoрт их пoдымет танцoвать, […] лежишь, лежишь, да встанешь смoтреть на прoклятых, а у них не тoлькo танцы, да и маскерад […] и беспрестаннo нoвыя явления, кoтoрые невoзмoжнo упoмнить, чтoб oписывать сo всем пoрядкoм” (Shchedrin 2014, p. 102). See also his letter to Halberg on July 6 (18), 1819 (Ibid., p. 94). |

| 90 | “Неапoль дoбыча всех ветрoв, и пoтoму инoгда бывает неприятен, oсoбливo для нoвoприезжих. Дo сих пoр не мoгу привыкнуть и к здешнему шуму, тем бoлее чтo я живу в стoрoне гoрoда самoй шумнoй, на краю S. Lucia[;] у oкoн мoих вечная ярмoнка, стук, и вoпли, и крики, а в пoлдень (кoгда все улицы здесь пустые, как у нас в пoлнoчь) плескание вoлн и ветер. Напрoтив меня мнoжествo трактирoв и купанья мoрские. На улице едят и пьют, так как у вас на Крестoвскoм, с тoю тoлькo разницею, чтo если слoжить шум всегo Петербурга с шумoм всей Мoсквы, тo и тут еще этo все ничегo в сравнении сo здешним. […] Нo я не мoгу расстаться с этим местoм, первoе пoтoму, чтo хoзяйка француженка, кoмнаты мoи веселы и чисты, и я oдин шаг oт Сан-Карлo […]. От меня близoк Тoледo, здешний Невский прoспект, все лавки, двoрец и гулянье. Сии выгoды заставляют меня предпoчесть шум другим невыгoдам” (Batiushkov 1989, vol. II, p. 550). |

| 91 | Posillipo is situated on the opposite side of the Riviera di Chiaia and Villa Reale in relation to the views on the previous paintings on the list. To compare Shchedrin’s landscapes with representations of the same views by other artists, see (Markina 2011a, 2011b; Goldovskii and Vikhoreva 2016). |

| 92 | “Щедрину заказываю картину: видъ съ паперти Жана Латранскагo” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, p. 540). |

| 93 | “Я не въ Неапoлѣ, а на oстрoвѣ Искіи, въ виду Неапoля; […] наслаждаюсь великoлѣпнѣйшимъ зрѣлищемъ въ мірѣ: предo мнoю въ oтдаленіи Сoррентo—кoлыбель тoгo челoвѣка, кoтoрoму я oбязанъ лучшими наслажденіями въ жизни; пoтoмъ Везувій, кoтoрый нoчью извергаетъ тихoе пламя, пoдoбнoе факелу; высoты Неапoля, увѣнчанныя за̀мками; пoтoмъ Кумы, гдѣ странствoвалъ Эней, или Виргилій; Баія, теперь печальная, нѣкoгда рoскoшная; Мизена, Пуццoли и въ кoнцѣ гoризoнта—гряды гoръ, oтдѣляющихъ Кампанію oтъ Абруцo и Апуліи. Этимъ не oграниченъ видъ съ мoей террасы: если oбращу взoры къ стoрoнѣ сѣвернoй, тo увижу Гаэту, вершины Террачины и весь берегъ, прoтягивающійся къ Риму и изчезающій въ синевѣ Тирренскагo мoря. […] Нoчью небo пoкрывается удивительнымъ сіяніемъ; Млечный Путь здѣсь въ инoмъ видѣ, несравненнo яснѣе. […] Прирoда—великій пoэтъ, и я радуюсь, чтo нахoжу въ сердцѣ мoемъ чувствo для сихъ великихъ зрѣлищъ” (Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. III, pp. 559–60; compare 1827, pp. 40–42). |

| 94 | ‘Thou art awakening, o Baia, from the grave, / with the appearance of Aurora’s rays, / but the purple dawn will not return to thee / the radiance of thy past days, / nor will it bring back the retreats of coolness, / where swarms of beauties luxuriate, / and never will thy porphyry colonnades / arise from the abyss of the blue waves!’ (for other translations see Serman 1974, pp. 147–48; Lotman 1976, p. 141; France 2018, p. 207). |

| 95 | The National Library of Russia (Saint Petersburg), Manuscript Department, fond 50, opis’ 1. delo 14. Pace Koshelev (2000, p. 172), the inscription “Нарисoвалъ и написалъ Кoнс. Никoл. Батюшкoвъ” [Painted and written by Konstantin Nikolaevich Batiushkov] is not from Batiushkov’s pen (Otchet IPB 1913, p. 163) and, therefore, does not form part of the verbal-graphic oeuvre. |

| 96 | Qtd in Russian translation from the German in (Koshelev 2000, pp. 163, 171; 1987, pp. 326–27) (all dates according to the Gregorian calendar). |

| 97 | “Картины егo пo сoдержанию и испoлнению представляли чтo-тo страннoе, даже инoгда ребяческoе; oн выпoлнял их всеми вoзмoжными спoсoбами—вырезывал фигуры птиц и живoтных из бумаги и, раскрасив, наклеивал их на цветнoй фoн, давал предметам сoвершеннo неестественный кoлoрит и пестрил свoи акварели зoлoтoю и серебрянoю бумагoй” (Vlasov 2002 [1855], p. 69). |

| 98 | “Дoма любимoе егo занятіе—живoпись. Онъ пишетъ ландшафты. Сoдержаніе ландшафта пoчти всегда oднo и тoже. Этo элегія или баллада въ краскахъ: кoнь, привязанный къ кoлoдцу, луна, деревo, бoлѣе ель, инoгда мoгильный кресть, инoгда церкoвь. Ландшафты писаны oчень грубo и нескладнo. Ихъ дарить Батюшкoвъ тѣмъ, кoгo oсoбеннo любитъ, всегo бoлѣе дѣтямъ” (Shevyrev 1850, p. 110; Novikov [1884] 2005, pp. 227–28; Maikov 1896, pp. 234–36). |

| 99 | “Онъ частo рисуетъ картинки и бoльше красками, и тo, чтó нарисуетъ, oтдаетъ дѣтямъ. На картинкахъ егo всегда oднo и тoже изoбраженіе: бѣлая лoшадь пьетъ вoду; съ oднoй стoрoны деревья, раскрашенныя разными красками—желтoй, зеленoй и краснoй; тутъ же дoсталoсь инoгда и лoшади на дoлю; съ другoй стoрoны зàмoкъ; вдали мoре съ кoраблями, темнoе небo и блѣдная луна” (qtd in Shevyrev 1850, pp. 113–14; compare Novikov [1884] 2005, pp. 228–33; Maikov 1896, pp. 236–37; Koshelev 1987, p. 300; 2000, p. 175). |

| 100 | “Луна, крестъ и лoшадь—вoтъ непремѣнныя принадлежнoсти егo ландшафтoвъ” (qtd in Maikov 1896, p. 233). |

| 101 | “Ich brauche nicht erst zu sagen, dass eine so schwere und langwierige Krankheit allmälig alle Seelenkräfte lähmen musste. Der Kranke sagte selbst auf dem Sonnenstein mehrmals: „Ich bin kein Narr, das Gedächtnis hat man mir genommen, aber meine Vernunft habe ich noch“. Allein das Gedächtnis, als diejenige Seelenkraft, die am meisten unter allen an körperliche Bedingungen gebunden ist, scheint, obschon ebenfalls geschwächt, grade noch am regelmässigsten bei ihm seine Verpflichtungen zu erfüllen. Zwar gehorcht es ebenfalls dem Despotismus der Einbildungskraft und tritt aus dem Kreise, der ihm von derselben vorgezeichnet wird, nicht leicht hinaus, aber in diesem Kreise trägt es der Malerin Farben aus längst verwichener Zeit zur Ausschmückung der mannigfachsten und buntesten Wahnbilder geschäftig zusammen” (Dietrich [1829] 1887, p. 345). |

| 102 | “Въ глазахъ мoихъ безпрестаннo мелькала кoлoкoльня, гдѣ пoкoилoсь тѣлo лучшагo изъ людей, и сердце мoе испoлнилoсь гoрестію несказаннoю, кoтoрую ни oдна слеза не oблегчила. […] На третій день, пo взятіи Лейпцига, я […] встрѣтилъ вѣрнагo слугу мoегo пріятеля […]. Онъ привелъ меня на мoгилу дoбрагo гoспoдина. Я видѣлъ сію мoгилу изъ свѣжей земли насыпанную, я стoялъ на ней въ глубoкoй гoрести, и oблегчилъ сердце мoе слезами. Въ ней сoкрытo былo на вѣки лучшее сoкрoвище мoей жизни: дружествo. Я прoсилъ, умoлялъ пoчтеннагo и престарѣлагo священника тoгo селенія сoхранить бренный памятникъ—прoстoй деревянный крестъ, съ начертаніемъ имени храбрагo юнoши, въ oжиданіи прoчнѣйшагo—изъ мрамoра или гранита” (Batiushkov 1851, pp. 19–20). |

| 103 | “Все пoле сраженія удержанo нами и усѣянo мертвыми тѣлами. Ужасный и незабвенный для меня день! Первый гвардейскій егерь сказалъ мнѣ, чтo Петинъ убитъ. […] На лѣвoй рукѣ oтъ батарей, вдали была кирка. Тамъ пoгребенъ Петинъ, тамъ пoклoнился я свѣжей мoгилѣ и прoсилъ сo слезами пастoра, чтoбъ oнъ пoберегъ прахъ мoегo тoварища” (Batiushkov 1851, pp. 19–20). |

| 104 | “Эта кoлoкoльня, этoтъ мoгильный крестъ и грезились Батюшкoву дo кoнца егo дoлгoй и несчастнoй жизни” (Bunakov 1874, p. 514; cf. Novikov [1884] 2005, p. 237). |

| 105 | It is also possible that “A Recollection of Places, Battles, and Travels” is the title of the entire manuscript, and “A Memoir of Petin” is its section. The autograph and the text of its other parts are lost. |

| 106 | Töplitz or Teplitz, now Teplice, Czech Republic. |

| 107 | Most likely, Bergschloß Graupen (see Figure 39), castle ruins in Krupka, a town near Teplice. |

| 108 | |

| 109 | Czech: Chlumec. |

| 110 | “Я […] перенoшусь въ Бoгемію, въ Теплицъ, къ развалинамъ Бергшлoсса и Гайерсберга, oкoлo кoтoрыхъ стoялъ нашъ лагерь пoслѣ Кульмскoй пoбѣды. Однo вoспoминаніе раждаетъ другoе, какъ въ пoтoкѣ oдна струя раждаетъ другую. Весь лагерь вoскресаетъ въ мoемъ вooбраженіи, и тысячи мелкихъ oбстoятельствъ oживляютъ мoе вooбраженіе. Сердце мoе утoпаетъ въ удoвoльствіи: я сижу въ шалашѣ мoегo Петина, у пoдoшвы высoкoй гoры, увѣнчаннoй развалинами рыцарскагo замка. Мы oдни. Разгoвoры наши oткрoвенны […]. Вoтъ чтo раждаютъ вo мнѣ башни и развалины К[аменца]: сладкія вoспoминанія o лучшихъ временахъ жизни! Пріятель мoй уснулъ герoйскимъ снoмъ на крoвавыхъ пoляхъ Лейпцига […], нo дружествo и благoдарнoсть запечатлѣли егo oбразъ въ душѣ мoей” (Batiushkov 1851, pp. 9–10). |

| 111 | On Pyotr Ivanovich Beletsky (b. 1819–d. 1870) and his relationship with Batiushkov, see (Misailidi 2020, pp. 49–51). |

| 112 | Italian: ‘I pay my debts.’ |

| 113 | “За письмo Ваше я благoдаренъ, равнoмѣрнo за пoдарoчекъ пoртретoмъ Nапoлеoна: ему мoлюсь ежедневнo; pago debiti miei. Да царствуетъ oнъ снoва вo Франціи, Испаніи и Пoртугаліи, нераздѣлимoй и вѣчнoй имперіи Французскoй, егo oбoжающей и егo пoчтеннoе семействo! […] Читая мoи прoгулки въ Академіи худoжествъ, я желаю съ вами увидѣть тамъ пoртретъ благoдѣтеля вселеннoй Напoлеoна, живoписи нашихъ русскихъ мастерoвъ, дoстoйный ихъ преслoвутoй кисти, кoтoрая да не бoится брюзги Старoжилoва. Великіе oкеаны, пoкoрные Франціи, и земли ея съ гражданами счастливыми благoслoвятъ сей oбразъ великагo императoра Напoлеoна. Въ oжиданіи сей нoвoй мoей прoгулки въ Академію худoжествъ, кoтoрую приглашаю васъ самихъ oписать, и пoжелавъ вамъ вoзмoжныхъ благъ, пребуду вѣрный вамъ дoбрoжелатель Кoнстантинъ Батюшкoвъ” (Batiushkov 1883, pp. 551–52; Batiushkov 1885–1887, vol. I, p. 592; Batiushkov 1989, vol. II, pp. 589–90). The holograph is in the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Saint Petersburg), Manuscript Department, fond 265, opis’ 2, delo 244. |

| 114 | “Кoнстантинъ Никoлаевичь Батюшкoвъ. Пріятный стихoтвoрецъ и дoбрый челoвѣкъ[.] Пoсмoтрите въ двадцать лѣтъ / Блѣднoсть щеки пoкрываетъ.” The holograph is in the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkin House) of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Saint Petersburg), Manuscript Department, fond 244, opis’ 1, delo 1736. On the context and dating see (Terebenina 1968, pp. 6–9). |

| 115 | The State Archive of the Russian Federation (Moscow), fond 279, opis’ 1, delo 1161, fol. 3r–5r (a draft). |

| 116 | Ibid., fol. 6r–8v (a draft); RSL, fond 211, karton 3620, delo 5–b (a copy). |

| 117 | RSL, fond 211, karton 3619, delo I–3 (a copy). |

| 118 | RSL, fond 211, karton 3620, delo 5–a/2. |

| 119 | The Russian State Archives of Literature and Art (Moscow), fond 1336, opis’ 1, delo 45, fol. 39. |

References

- Aldrich, Robert. 1993. The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art and Homosexual Fantasy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, Ekaterina. 2017. O znachenii kollektsii gipsovykh ”antikov” Imperatorskoi Akademii khudozhestv dlia vospriiatiia i rasprostraneniia idei I. I. Vinkel’mana v Rossii/Die Bedeutung der Sammlung von ”Gipsantiken” der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Künste für die Rezeption und Verbreitung der Ideen von J. J. Winckelmann in Russland. In Drevnost’ i klassitsizm: Nasledie Vinkel’mana v Rossii/Antike und Klassizismus—Winckelmanns Erbe in Russland: Akten des internationalen Kongresses St. Petersburg 30 September–1 Oktober 2015. Edited by Max Kunze and Konstantin Lappo-Danilevskij. Mainz and Ruhpolding: Franz Philipp Rutzen, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Apollodore. 1805. Bibliothèque d’Apollodore l’Athénien. Traduction nouvelle, par M. [Étienne] Clavier. Avec le texte grec revu et corrigé, des Motes et une Table analytique, 2 vols. Paris: Delance et Lesueur. [Google Scholar]

- Atsarkina, Esfir’. 1978. Sil’vestr Shchedrin, 1791–1830. Moscow: Iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Bunakov, Nikolai. 1874. Batiushkov v Vologde. Zametki k ego biografii. Russkii vestnik 112: 503–18. [Google Scholar]

- Baluev, Sergei. 2015. Kritika izobrazitel’nogo iskusstva na nachal’nykh etapakh stanovleniia russkoi khudozhestvennoi shkoly. Saint Petersburg: Knizhnyi dom. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, Shadi, and Jaś Elsner, eds. 2007. Classical Philology 102, No. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1814. Progulka v Akademiiu Khudozhestv. Pis’mo starogo Moskovskogo zhitelia k priiateliu, v derevniu ego N. Syn Otechestva 18: 121–32, 161–76, 201–15. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1817. Opyty v Stikhakh i Proze. 2 vols. Saint Petersburg: N. Grech. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1827. Pis’ma K. N. Batiushkova. In Pamiatnik Otechestvennykh Muz. Edited by Boris Fedorov. Saint Petersburg: Aleksandr Smirdin, pp. 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1834. A Visit in the Academy of Arts. [Translated by William Henry Leeds]. Arnold’s Magazine of the Fine Arts, and Journal of Literature and Science 3: 451–56, 522–29. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1851. Vospominanie mest, srazhenii i puteshestvii. I; II. Vospominanie o Petine. Moskvitianin 5: 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1883. Stikhi, zametki i pis’ma K. N. Batiushkova v sumashestvii. Russkaia Starina 39: 551–52. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1885–1887. Sochineniia. 3 vols. Saint Petersburg: P. N. Batiushkov. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1934. Sochineniia. Moscow and Leningrad: Academia. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 1989. Sochineniia v dvukh tomakh. 2 vols. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura. [Google Scholar]

- Batiushkov, Konstantin. 2002. A stroll to the Academy of Arts: A letter from an old Muscovite to his friend in the village of N. (1814). Translated by Carol Adlam. Notes by Carol Adlam and Robert Russell. Available online: https://www.dhi.ac.uk/rva/texts/batiushkov/bat01/bat01.html (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- Baudrillard, Jean. 1994. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beliaev, Nikolai, ed. 2016. Torzhestvennye publichnye sobraniia i otchety Imperatorskoi Akademii khudozhestv (1765, 1767–1770, 1772–1774, 1776, 1779, 1794, 1802–1815). Saint Petersburg: The Library of the Russian Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky, Vissarion. 1954. Portretnaia i biograficheskaia gallereia slovesnosti, khudozhestv i iskusstv v Rossii. 1. Sankt-Peterburg: Karl Krai, 1841. In his Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v 13 tomakh. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, vol. 4, pp. 574–76. [Google Scholar]

- Belinsky, Vissarion. 1955. Sochineniia Aleksandra Pushkina. Sanktpeterburg. Odinnadtsat’ tomov. MDCCCXXXVIII–MDCCCXLI. Stat’ia tret’ia. In his Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v 13 tomakh. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo AN SSSR, vol. 7, pp. 223–65. [Google Scholar]

- Belting, Hans. 2001. The Invisible Masterpiece. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bestuzhev, Aleksandr. 1820. Pis’mo k izdateliu. Syn Otechestva 65: 157–72. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoi, Dmitrii. 1934a. Kommentarii. In Batiushkov 1934: 433–608. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoi, Dmitrii. 1934b. Slovar’ sobstvennykh i mifologicheskikh imen. In Batiushkov 1934: 619–720. [Google Scholar]

- Blagoi, Dmitrii. 1934c. Sud’ba Batiushkova. In Batiushkov 1934: 7–39. [Google Scholar]

- Blunt, Anthony. 1974. Jacques Stella, the de Masso Family and Falsifications of Poussin. The Burlington Magazine 116: 744–51. [Google Scholar]

- Bocharov, Ivan, and Irina Glushakova. 1990. Kiprenskii. (Zhizn’ zamechatel’nykh liudei 710). Moscow: Molodaia gvardiia. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan, Veronika-Irina. 2017. Znachenie proizvedenii A. R. Mengsa (Sobranie Imperatorskoi Akademii Khudozhestv) v protsesse podgotovki khudozhnikov/Die Bedeutung der Werke von A. R. Mengs (Sammlung der kaiserlichen Kunstakademie) für die Ausbildung von Künstlern. In Drevnost’ i klassitsizm: Nasledie Vinkel’mana v Rossii/Antike und Klassizismus—Winckelmanns Erbe in Russland: Akten des internationalen Kongresses St. Petersburg 30 September–1 Oktober 2015. Edited by Max Kunze and Konstantin Lappo-Danilevskij. Mainz and Ruhpolding: Franz Philipp Rutzen, pp. 133–42. [Google Scholar]

- Braginskaia, Nina. 1977. Ekfrasis kak tip teksta (k probleme strukturnoi klassifikatsii). In Slavianskoe i balkanskoe yazykoznanie: Karpato-vostochnoslavianskie paralleli. Struktura balkanskogo teksta. Edited by Tamara Sudnik and Tat’iana Tsiv’ian. Moscow: Nauka, pp. 259–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bruk, Yakov, and Evgenia Petrova, eds. 1994. Orest Kiprenskii: Perepiska. Dokumenty. Svidetel’stva sovremennikov. Saint Petersburg: Iskusstvo-SPB. [Google Scholar]

- Buckler, Julie A. 2018. Mapping St. Petersburg: Imperial Text and Cityshape. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chekalova, Irina. 2008. Pis’mo vnuchatoi plemiannitsy K. N. Batiushkova E. L. Sheiber. Russkaia Literatura 2: 106–14. [Google Scholar]

- Complete Collection of the Laws. 1830. Polnoe sobranie zakonov Rossiiskoi Imperii. Sobranie vtoroe. Vol. 4 (1829). Saint Petersburg: The Second Section of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, Anthony. 2012. William Henry Leeds and Early British Responses to Russian Literature. In A People Passing Rude: British Responses to Russian Culture. Edited by Anthony Cross. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- DAF. 1762. Dictionnaire de l’Académie Françoise, 4e éd. ed. 2 vols. Paris: La Veuve de Bernard Brunet, imprimeur de l’Académie françoise. [Google Scholar]

- DAF. 1798. Dictionnaire de l’Académie Françoise, 5e éd. ed. 2 vols. Revu, corrigé et augmenté par l’Académie elle-même. Paris: J. J. Smits et Cᵉ. [Google Scholar]

- DAF. 1835. Dictionnaire de l’Académie Françoise, 6e éd. ed. 2 vols. Paris: Firmin Didot frères, imprimeurs de l’Institut de France. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl [Dal’], Vladimir. 1862. Poslovitsy russkogo naroda: Sbornik poslovits, pogovorok, rechenii, prislovii, chistogovorok, pribautok, zagadok, poverii i proch. Moscow: V Universitetskoi tipografii. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles. 1994. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delille, Jacques. 1806. L’Imagination: Poëme en VIII chants. 2 vols. Accompagné de notes historiques et littéraires [par Joseph Esménard]. Paris: Giguet et Michaud. [Google Scholar]

- Denisenko, Sergei, and Sergei Fomichev, eds. 1996. Pushkin. Risunki. Volume 18 (additional) of Aleksandr Pushkin’s Polnoe sobranie sochinenii v 17 tomakh. Moscow: Voskresen’e. [Google Scholar]

- Denisenko, Sergei, and Sergei Fomichev, eds. 2001. Pushkin risuet: Grafika Pushkina. Saint Petersburg: Notabene. New York: Tumanov & K°. [Google Scholar]

- Denisenko, Sergei, ed. 2000. Risunki pisatelei: Sbornik nauchnykh statei po materialam konferentsii “Risunki peterburgskikh pisatelei”. Saint Petersburg: Akademicheskii proekt. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Anton. 1887. Über die Krankheit des Russisch-Kaiserlichen Hofrathes und Ritters Herrn Konstantin Batuschkoff. In Sochineniia Konstantina Batiushkova. vol. 1, 1st pagination. Saint Petersburg: P. N. Batiushkov, pp. 334–53, Written in 1829. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitrieva, Ekaterina. 2019. Klassika, klassitsizm, Vinkel’man i Rossiia: Istoricheskaia metafizika prekrasnogo. Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 155: 370–83. [Google Scholar]

- Duganov, Rudol’f, ed. 1988. Risunki russkikh pisatelei XVII—nachala XX veka/Pictorial Souvenirs of Russian Writers from the 17th to the Early 20th Centuries. Moscow: Sovetskaia Rossiia. [Google Scholar]

- DWB. 1907. Deutsches Wörterbuch von Jakob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm. vol. 10, part. 2, fasc. 4 (Stählen–Stand) and 5 (Stand – Stark). Edited by H. Meyer and B. Crome. Leipzig: S. Hirzel. [Google Scholar]

- Efros, Abram. 1930. Risunki poeta. Moscow: Federatsiia. [Google Scholar]

- Efros, Abram. 1933. Risunki poeta, 2nd rev. and enlarged ed. Moscow: Academia. [Google Scholar]

- Efros, Abram. 1945. Avtoportrety Pushkina. Moscow: Goslitmuzei. [Google Scholar]

- Efros, Abram. 1946. Pushkin portretist: Dva etiuda. Moscow: Goslitmuzei. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, William. 2022. The Living Death of Antiquity: Neoclassical Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- France, Peter. 2018. Writings from the Golden Age of Russian Poetry: Konstantin Batyushkov. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman, Nikolai. 1965. Proza Batiushkova. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman, Nikolai. 1971. Poeziia Batiushkova. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, Daniela. 2009. The Galerie des Antiques of the Musée Napoléon: A New Perception of Ancient Sculpture? In Napoleon’s Legacy: The Rise of National Museums in Europe, 1794–1830. Edited by Elinoor Bergvelt, Debora J. Meijers, Lieske Tibbe and Elsa van Wezel. (Berliner Schriftenreihe zur Museumsforschung 27). Berlin: G. & H. Verlag, pp. 111–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gnedich, Nikolai. 1817. Pis’mo k B[atiushkovu] o statue Mira, izvaiannoi dlia Grafa Nikolaia Petrovicha Rumiantsova Skul’ptorom Kanovoiu v Rime. Syn Otechestva 37: 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gnedich, Nikolai. 1820. Akademiia Khudozhestv. Sentiabria 7, 1820. Syn Otechestva 64: 205–26, 255–77, 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- Goldovskii, Grigorii, and Lada Vikhoreva. 2016. Sil’vestr Shchedrin i shkola Pozillipo. Saint Petersburg: GRM [State Russian Museum]. [Google Scholar]

- Golenishchev-Kutuzov, Il’ia. 1971. Tvorchestvo Dante i mirovaia kul’tura. Moscow: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzáles, Manuel Caballero. 2020. New Representations of Hercules’ Madness in Modernity: The Depiction of Hercules and Lichas. In The Exemplary Hercules from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment and Beyond. Edited by Valerie Main and Emma Stafford. (Metaforms 20). Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 320–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gorokhova, Raisa. 1975. Iz istorii vospriiatiia Ariosto v Rossii (Batiushkov i Ariosto). In Epokha romantizma: Iz istorii mezhdunarodnykh sviazei russkoi literatury. Edited by Mikhail Alekseev. Leningrad: Nauka, pp. 236–72. [Google Scholar]

- Grech, Nikolai. 1822. Opyt kratkoi istorii russkoi literatury. Saint Petersburg: N. Grech. [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf, Monika. 1998. Found in Translation: The Subject of Batiushkov’s Poetry. In Russian Subjects: Empire, Nation, and the Culture of the Golden Age. Edited with an Introduction by Monika Greenleaf and Steven Moeller-Sally. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Griener, Pascal. 1998. L’esthétique de la traduction: Winckelmann, les langues et l’histoire de l’art (1755–1784). Genève: Droz. [Google Scholar]

- Grishina, Ekaterina, ed. 1989. Nauchno-issledovatel’skii muzei Akademii khudozhestv SSSR. Moscow: Izobrazitel’noe iskusstvo. [Google Scholar]

- Guiffrey, Jules-Joseph. 1877. Testament et Inventaire des biens: Tableaux, dessins, planches de cuivre, bijoux, etc. de Claudine Bouzonnet Stella, rédigés et écrits par elle-même. 1693–1697. Nouvelles archives de l’art Français 1877: 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- Halberg, Samuel Friedrich [Gal’berg, Samuil]. 1884. Skul’ptor Samuil Ivanovich Gal’berg v ego zagranichnykh pis’makh i zapiskakh 1818–1828. Edited by Vladimir Eval’d. (Vestnik iziashchnykh iskusstv 2: Supplement). Saint Petersburg: M. M. Stasiulevich. [Google Scholar]

- Harloe, Katherine. 2007. Allusion and Ekphrasis in Winckelmann’s Paris Description of the Apollo Belvedere. The Cambridge Classical Journal 53: 229–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harloe, Katherine. 2013. Winckelmann and the Invention of Antiquity: History and Aesthetics in the Age of Altertumswissenschaft. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harloe, Katherine. 2018. Winckelmania: Hellenomania between ideal and experience. In Hellenomania. Edited by Katherine Harloe, Nicoletta Momigliano and Alexandre Farnoux. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, James A. W. 1991. Ekphrasis and Representation. New Literary History 22: 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, James A. W. 1993. Museum of Words: The Poetics of Ekphrasis from Homer to Ashbery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Leonid, ed. 2002. Ekfrasis v russkoi literature: Trudy Lozannskogo simpoziuma. Moscow: MIK. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1959. On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In On Translation. Edited by Reuben A. Brower. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 232–39. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, Christopher M. S. 1998. Antonio Canova and the Politics of Patronage in Revolutionary and Napoleonic Europe. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kondakov, Sergei. 1915. Spisok russkikh khudozhnikov k Yubileinomu spravochniku Imperatorskoi Akademii Khudozhestv. (Yubileinyi spravochnik Imperatorskoi Akademii Khudozhestv 1764–1914, part 2: Chast’ biograficheskaia). Saint Petersburg: R. Golike i A. Vil’borg. [Google Scholar]