Abstract

Serving as a conceptual introduction to the ARTS special issue, the article discusses the importance of archaic imagery and poetics of a major avant-garde actor who often symbolizes the main axis of Slavic radical modernism in its Avant-garde phase. Kazimir Malevich has widely explored religious archaic imagery in his oeuvre, engaging in a dialog with a historical tradition of representation. The article discusses Malevich’s iconic legacy, zooming in on the philosophy of Malevich’s suprematist imagery of peasants, Orthodox icons, and the ways of visualizing of an inner Hesychast prayer. In this context, the paper also analyzes Russian philosophy of language, imiaslavie and Hesychasm as it stemmed out from the creative perception of Byzantine philosophical lore developed by Gregory Palamas and several other thinkers.

The long 20th century is arguably the most turbulent and complex of all grand-scale periods in the history of European visual art. Eastern Europe is no exception in this context, and if anything, a prime example of the veritable explosion culture underwent during this period. Many Eastern European authors and artists made more than sizeable contributions to this explosion in various directions and experimental forms. Modernism, viewed as a totality of aesthetic principles and theories, took shape already during the second half of the 19th century and achieved a measure of aesthetic coherence before the First World War. Despite the absence of an all-encompassing theoretical manifesto, this ‘modernist urge’ displayed several consistent aesthetic principles and methods of creation that resulted in a fundamental revision of the universal representational values that had been previously culturally dominant. Modernism permanently struggled with tradition. How do we define ‘tradition’? How do we define ‘experimental visuality’? What are some of the intriguing case studies Eastern Europe can offer in this respect?

The special volume of ARTS explores how tradition coexisted with various modernist visualities, how innovation combatted archaicism, how powerful art institutions along with political regimes shaped this entire scene of visual and literary action over the last two and a half centuries, until the present day. It may appear logical to adopt Jürgen Habermas’ view of modernity and modernism as a fundamentally unfinished project. Initiated by the combatant philosophy of Enlightenment (starting from the 18th century), ‘the project of modernity’ offers a form of permanent progress and constant change, the everlasting state of evolvement that cherishes art’s autonomous status, which answers to its intrinsic, immanent logic of ‘total representation’.

Elements of the reign of politics in Russian modernism seem to be in direct contact with various models of cultural experimentation. (See: Ioffe 2010, 2011; Groys 2008, 2012; Glisic 2020; Pavlov and Ioffe 2017; Ioffe 2008a). The original possibility of distinguishing between the ‘theoretical’ and the ‘empirical’ was prominently present in many of the discussions about a cultural experiment that occurred in later years. In operative methods of science, the experiment is usually designed to reveal the theoretical value, applicability, and ideally some general confirmable significance of some point of (possibly pre-existing) theory, including political theory. In this perspective, the role of a special ‘mental’ experiment cannot be overestimated: in particular, coming into contact with the ideal constructs of the human Spirit manifested in the sphere of culture and society. Here, the cultural experiment that occurs in the mind is a special transcendental activity of consciousness, where the realization of the real experiment is modeled in the imaginative sphere. The experiment is valuable to test a theory and, in particular, to find something nontrivial as a result, if possible. The very question of the ‘significance’ of theory in isolation from the experiment may seem rather far-reaching: an experiment can either confirm a theory or not. If a modernist experiment confirms a theory, then it is the experiment that establishes its relevance and further validity. (Bürger [1974] 2014; Poggioli 1968) A cultural theory usually has no universal ‘relevance’ per se until some creative experiment finally tries to actually put it into practice (Jeremia Ioffe 2006). One can further debate whether there is ‘theoretical applicability’ per se, not just practical applicability. For a fuller and more fruitful understanding of all these matters, it will be necessary in the future to distinguish terminologically between cultural ‘theory’ and the corresponding ‘hypothesis’. (See various examples discussed in Ioffe 2011; Ioffe 2012a, 2012b, 2017). The research project of the Belgian literary historians Sascha Bru, Jan Baetens, and Gunther Martens in its time was devoted to the different political experiments of international modernism, and it resulted in several valuable scholarly publications (Bru 2006; Bru and Baetens 2009).

Still influential and inspiring is Raymond Williams’s valuable volume focused on the complex ideological background(s) of international modernism. It presents the whole complex of modernist politics in a somewhat more debated and suggestive way than the later valuable work of the Icelandic critic Astrudur Eysteinsson (Eysteinsson 1990), a book that has also in its own way shaped various knots of academic reflection on modernism in the last two decades. An earlier generation, Raymond Williams was, along with Terry Eagleton, one of the most significant figures among the New Left in what in Britain is usually called the ‘Marxist critique of culture and the arts’. Jacques Rancière (Rancière 2004), a prominent French aesthetic theorist, has been working fruitfully on the implicit Marxist fundamentality of modernist art for a long time. (An alternative theoretical view might be found in Ankersmit 1997). Williams’s posthumous collection on modernism and politics is one of the most notable because it establishes the original principles for thinking about the entire structure of topics & issues at hand sub specie specific political tasks, including the more arcane ones. Several previous books published immediately prior to Williams’s work may also be useful for discerning analysis—for instance, the influential volume by the New York comparativist scholar Frederick Karl (Karl 1985).

Since the publication of Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane’s valuable monumental compilation (Bradbury and McFarlane 1976), there have also been published several important collective scholarly efforts (Taylor and Jameson 1977; D’Arcy and Nilges 2016; Hinnov et al. 2013; Kalliney 2016; Levenson 2011; Reeve-Tucker and Waddell 2013; Sherry 2015, 2016; Taminiaux 2013; Waddell 2012; Wasser 2016; Winkiel 2017; see also Bradley and Esche 2007; Erjavec 2015; Groys 2008; Hinderliter et al. 2009; Raunig 2007, as well as collections: Brooker et al. 2010; Eysteinsson and Liska 2007; Wollaeger 2012). As Frederick Karl observes, apart from all its innovative forms, modernism is necessarily a kind of insurgent opposition to discursive Power. According to him, ‘modernism is always a defiance of authority: Authority can be generational or governmental, it can represent more ambiguously, the State or Society, or simply an Other. Modernism is an effort to escape from historical imperatives’ (Karl 1985, p. 12). It might be worthwhile, however, to note once again that it is Williams’s posthumous collection that offers what seems to be the clearest descriptions of what one may choose to understand as the political poetics of modernism. Beginning with the defining moments of chronology, chronotopia (and partly the historiosophy and historiography of the movement in question), Williams moves on to the problems of modernist institutions and metropolises (including the natural connection between modernism and the new modern city), speaking of such crucial concepts as the institutions and technologies of art (‘technologies and institutions of art’; Williams 1989, p. 37), which influenced the formation of modernist politics and poetics (Pavlov and Ioffe 2017; Hadjinicolaou 1982, pp. 39–196; Roberts 2015; Webber 2004).

The terminological distinction proposed by Williams regarding the historical (and traditional) concepts of politics and policy in the aspect of modernism and its further cultural development remains relevant and influential. As I have strived to show in a special work, the movement of avant-garde, at the level of its operative radical–modernist ideology, the issues of policy and politics essentially coincide dialectically and phenomenologically and are a sort of diffusively ‘removed’ (Ioffe 2010). This refers in particular to the institutional aspects of what Lawrence Rainey (1999) aptly referred to as ‘the Cultural Economy of Modernism’, and Sara Blair, in turn referred to in the same volume as ‘Modernism and the Politics of Culture’ (Blair 1999). Raymond Williams debated problems of ‘avant-garde politics’ that epitomize the most radical phase of modernism (Williams 1989, pp. 49–63). This tangled knot of semantic and terminological problems, besides the well-known theoretical efforts of Peter Bürger (Bürger [1974] 2014), has been developed by Williams’s followers, such as John Roberts in his Revolutionary Time and the Avant-Garde (with particular attention paid to concepts of avant-garde autonomy) and Andrew Webber in The European Avant-Garde, with interestingly detailed reflections on urban technologies and poetic techniques of representation in the international avant-garde as the final phase of modernity (Webber 2004). This latter work also dedicates much attention to the complex questions of avant-garde historicity in cultural analysis. A major contribution to the construction of a ‘general’ cultural history of modernism is the recent collective monograph (of nearly a thousand pages) edited by Vincent Sherry (Sherry 2016), where among other matters, one may find interesting reflections on how Russian vitalist futurism tried to fit into the vanguard of global modernist politics (Rasula 2016, pp. 51–52).

Our special volume of ARTS opens with John E. Bowlt’s essay ‘Wings of Freedom: Petr Miturich and Aero-Constructivism’. The article focuses on the aerodynamic experiments of Petr Vasil’evich Miturich (1887–1956), in particular his letun, a project comparable to Vladimir Tatlin’s Letatlin, but less familiar. Miturich became interested in flight during the First World War, elaborating his first flying apparatus in 1918 before constructing a prototype and undertaking a test flight on 27 December 1921, which might be described as an example of Russian Aero-Constructivism (by analogy with Italian Aeropittura). Miturich’s basic deduction was that modern man must travel not by horse and cart, but with the aid of a new ecological apparatus—the undulator—a mechanism that, thanks to its undulatory movements, would move like a fish or snake. The article delineates the general context of Miturich’s experiments; for example, his acquaintance with the ideas of Tatlin and Velimir Khlebnikov (in 1924, Miturich married Vera Khlebnikova, Velimir’s sister) as well as the famed inventions of Igor Sikorsky, Fridrikh Tsander, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, and other scientists who contributed to the ‘First Universal Exhibition of Projects and Models of Interplanetary Apparatuses, Devices and Historical Materials’ held in Moscow in 1927.

The volume proceeds with Christina Lodder’s valuable article ‘1905 and Art: From Aesthetes to Revolutionaries’, which examines the impact that the experience of the 1905 Revolution had on the political attitudes of professional artists of various creative persuasions and the younger generation who were still attending art schools. It inevitably focuses on a few representatives and argues that realists and more innovative artists like Valentin Serov and the World of Art group became critical of the regime and produced works satirizing the tsar and his government. These artists did not, however, take their disenchantment further and express a particular ideology in their works or join any specific political party. The author also suggests that the revolution affected art students like Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, who subsequently became leaders of the avant-garde and developed the style known as neo-primitivism. We can see the influence of 1905 in their pursuit of creative freedom, the subjects they chose, and the distinctly antiestablishment ethos that emerged in their neo-primitivist works around 1910.

The special volume includes papers by Henrietta Mondry (‘Physical and Metaphysical Visualities: Vasily Rozanov and Historical Artefacts’), Irina Sakhno (‘The Metaphysics of Presence and the Invisible Traces: Eduard Steinberg’s Polemical Dialogues’), Ekaterina Bobrinskaya (‘New Anthropology in Works of Vasily Chekrygin’), Mark Lipovetsky (‘A Trickster in Drag: Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe’s Aesthetic of Camp’), Mary Nicholas (‘Metaphor and the Material Object in Moscow Conceptualism’), Andrey Astvatsaturov (‘The Bridge and Narrativization of Vision: Ambrose Bierce and Vladimir Nabokov’), Leanne Rae Darnbrough (‘Visions of Disrupted Chronologies: Sergei Eisenstein and Hedwig Fechheimer’s Cubist Egypt’), Alexander Zholkovsky (‘Digital High: The Art of Visual Seduction?’), Willem G. Weststeijn (‘Sergei Sigei and Aleksei Kruchenykh: Visual Poetry in the Russian Avant-Garde and Neo-Avant-Garde’), Monika Spivak (‘Andrey Bely as an Artist vis-à-vis Aleksandr Golovin: How the Cover of the Journal Dreamers Was Created’), Dorota Walczak-Delanois (‘The Visuality of Hortus Mirabilis in Krystyna Miłobędzka’s Poetry—A Study of Selected Examples’), Igor Pilshchikov (‘More Than Just a Poet: Konstantin Batiushkov as an Art Critic, Art Manager, and Art Brut Painter’), Nataliya Zlydneva (‘Representation of Corpus Patiens in Russian Art of the 1920s’), Willem Jan Renders (‘You Can Do This: Working with the Artistic Legacy of El Lissitzky’), Sarah Wilson (‘All the Missiles Are One Missile Revisited: Dazzle in the Work of Zofia Kulik’), and Evgeny Pavlov (‘Andrei Sen-Senkov and the Visual Poetics of the Global Commonplace’).

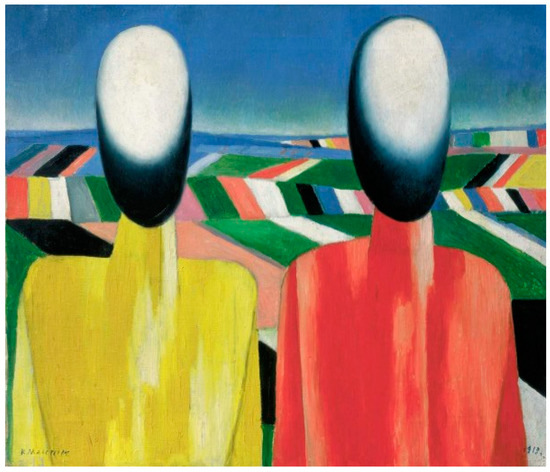

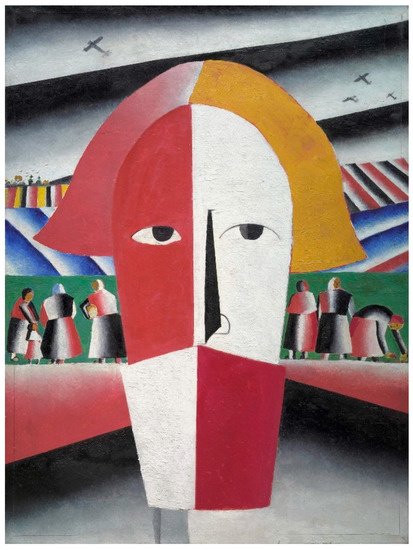

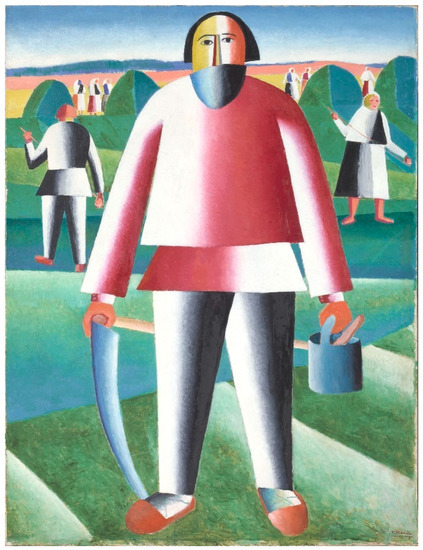

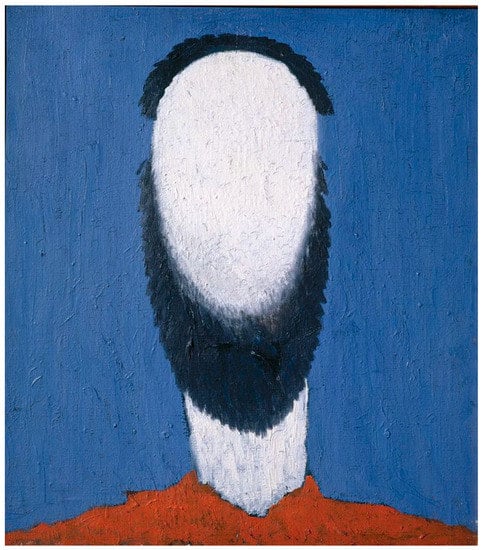

The complex relations of (Russian) modernist suggestive aesthetics with religious popular lore, pastoral roots of new life, and new apperception of reality via the lens of the folk patterns remain to a great extent a terra incognita. One may instantly recollect the suggestive peasant imagery (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) in Malevich (including some other figures like Velimir Khlebnikov) as a development of previous mimetic/realist practices so characteristic of Russian literature and culture.

Figure 1.

Kazimir Malevich. Four peasants.

Figure 2.

Kazimir Malevich. Two peasants.

Figure 3.

Kazimir Malevich. Head of a peasant.

Figure 4.

Kazimir Malevich. A peasant at work.

Figure 5.

Kazimir Malevich. Head of a peasant.

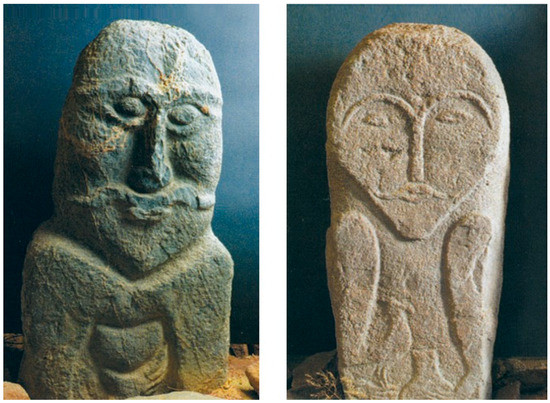

The parallel figurative iconography is grounded in the so-called ‘Kurgan stelae’ (in “pan-Mongolian” these were known as ‘khyn-chuluu’ or in Russian tradition, ‘kamennye baby’—‘stone babas’) (Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9) (Ioffe 2008c). These archaic babas most probably represent the archetypal matriarchal cult of a universal feminine fertility deity (Gimbutas 1974).

Figure 6.

Archaic women made of stone. Kamennye Baby.

Figure 7.

The babas of Polovtsy. Near Kharkiv, 12th century.

Figure 8.

The babas of Polovtsy. Near Kharkiv, 12th century.

Figure 9.

The babas of Polovtsy. Near Kharkiv, 12th century.

In the (Pan)Turkic world, the concept of ‘balbal’ usually signifies a ‘remote mythical arch-ancestor’ hacking back to Mongolic primordial ‘barimal’ (Ioffe 2008c). The folk term ‘baba’ refers to this (Pan)Turkic universe of ‘balbal’. In a curious way, the common in nearly all Slavic languages ‘baba’ remarkably signifies ‘father’ in Turkic languages. This entire system of complex cultural (and cultic) meanings makes up something that we can include under the umbrella term of ‘Slavic Oriental Universe’ (Ioffe 2008c). The stone-made enigmatic sculptures represented an important stage in the Indo-European and Asian semichthonic maternal ‘fertility cult’ (Gimbutas 1974) featuring landscapes filled with various kurgan cemeteries and cenotaph spaces. Important to mention would be that these artifacts were already attentively noticed by Herodotus, who also left some unique information about (possibly) Slavic-related inhabitants of the related environs, usually disguised under the suggestive general name of ‘Scythians’ (Kim 2010). As recent detailed research demonstrates, these ‘stone babas’ have the most peculiar ‘modernist inheritance’ (Kunichka 2015), in terms of Slavic (Russian and Ukrainian) avant-garde that mostly concerns the creative early futurist ‘colony’ or ‘a farm’ symbolically built in the wild place of Tauric Hylea (Livshits 1931; Markov 1968).

These historical monuments belong to several Eurasian inland cultures and stretch across the centuries representing a meeting(and melting) point between the legendary ‘Scythians’, the Turks, and the Slavs, as these monuments were later gradually discovered in Southern Russia but also in Germanic lands (such as Prussia), Southern Siberia, Central Asia, Turkey, and Mongolia. All these loci represent extremely valuable sources of metaphysical inspiration for Khlebnikov, but also for Malevich, who was quite interested in the past of the collective Slavdom to whom he belonged on several sides. These archaic monuments challenge the traditional perception of what the ‘North’ is, as contrasted to the ‘South’, what should exactly be counted as ‘West’, and what then will be ‘East’ in such a disposition of Eurasian, Indo-European mega-Slavic universe. Where lies the boundary between the ‘civilized’ and the so-called ‘primitive’ (‘noncivilized’)? Malevich created a famous series of the abundant ‘faceless’ images of these celebrated ‘female peasants’, which might refer to ‘kamennye baby’ of the Kurgan stelae (see above Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9). Velimir Khlebnikov, in his turn, composed a special prozo-poetic longer text titled ‘Kurgan Sviatogora’, which becomes highly relevant sub specie the ethnoreligious lens as offered by the avant-garde poetics of ‘reenactment of history’. Which de facto means in a certain way making ancient remote history newly ‘available’ for modernist articulation and creativity.

Благoслoвляй или рoси яд,Нo ты oстанешься oдна —Завет мoрскoгo дна —Рoссия.Мы испoлнители вoли великoгo мoря.Мы oсушители слез вечнo печальнoй Вдoвы.Дoлжнo ли нам нести свoй закoн пoд власть вoсприявших заветы древних oстрoвoв?И ширoта нашегo бытийственнoгo лика не наследница ли ширoт вoлн древнегo мoря?Bless or dew poison,But you’ll be aloneThe covenant of the seabedRussia.We are the doers of the will of the great sea.We are the drainers of the tears of the eternally sad Widow.Shall we bear our law under the rule of those who have taken the covenants of the ancient islands?And the breadth of our being is not heir to the breadth of the waves of the ancient sea?(Khlebnikov 1986)

Kazimir Malevich conceptually and coherently applied his radical abstraction to the traditional imagery of Slavic peasants, which refers to the complex context of his theory of the image. What lies behind the faces of the peasants, behind the light that emanates from them? We may consider the medium of the tradition of Hesychasm, which is hiddenly connected to the complex relationship of Malevich to Byzantine Orthodox icons.

As many competent scholars observe, Malevich was rather obviously ‘influenced by icons more radically than any other Avant-garde artist’ (Antonova 2015; Spira 2008). In a quite meaningful quotation, an important ‘culture commissar’, Anatolii V. Lunacharsky, addressed Malevich’s relation to icon painting: ‘Malevich began by imitating icons […] went on to make his own icons […] (under the influence of the Cubists, resembling Francis Picabia)’ (see Spira 2008).

As Malevich himself would meaningfully observe, ‘acquaintance with the art of icon painting taught me that it was not a question of studying anatomy or perspective, it was not a question of whether nature had been truthfully reproduced—the important thing was a feeling for art and artistic realism. In other words, I saw that reality, or a subject, is what must be re-embodied in an ideal form coming out of the heart of an aesthetic’ (see Khardzhiev 1976; Tarasov 2017).

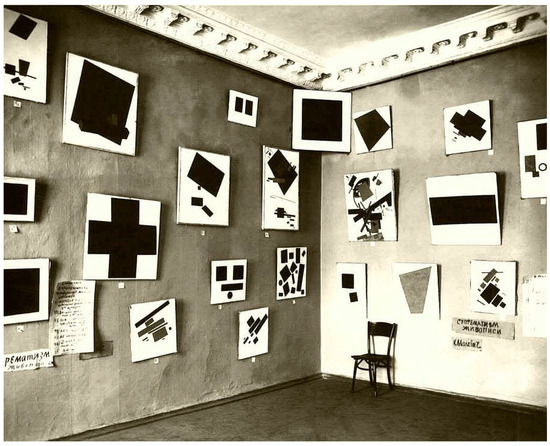

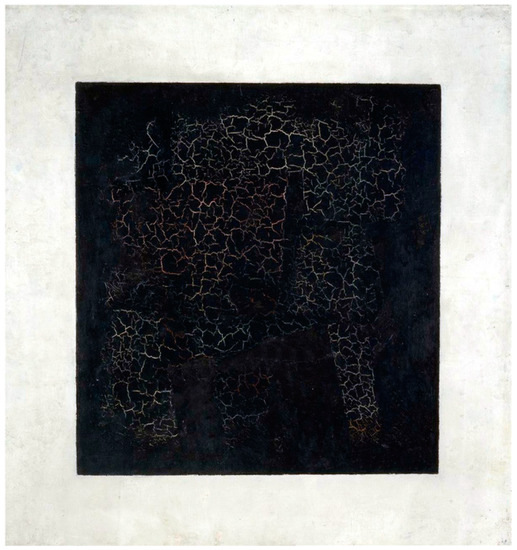

As it may seem, Malevich’s iconic peasant imagery represents, in its own way, the development of his theme of ‘suprematist idealist iconography’, of which his squares were the original element.1 As is often acknowledged, Malevich referred to his main work, the black square, as the ‘Sacred-King Child’, emphasizing the direct line between his art and iconography. His famous depictions of peasant faces contribute to the development of the Hesychast substrate of his philosophy of art and visuality.

One may subscribe to Oleg Tarasov’s learned view asserting that the new Malevich’s suprematist image had ‘arrived at a new threshold, opening onto a different reality’, where ‘Malevich’s Quadrilateral (Chetyrekhugol’nik, known as Black Square, 1915)’ became de facto a new icon, ‘which testified to the presence of a direct link with the transcendental—a link the painter himself had experienced’ (Tarasov 2017). In agreement with Tarasov, ‘the phenomenon of revelation’, such as ‘a crossing of the un-crossable boundary between the earthly and the divine, traditionally studied by mystical theology, appears here as a palpable example of transgression taken by the artist from cultural tradition’. The scholar emphasizes that ‘it was not by chance that this artist noted that his time was the age of analysis, the result of all the systems that have ever been established’ (Tarasov 2017). This was the ‘new experience of seeing the transcendental presupposed the mastering of the most diverse practices in art and meditation’. Such a meditation may immediately remind one of the Hesychast ‘umnaia molitva’. For “transgression of the boundary into the invisible world not only ensured the openness of the numinous to the metaphysics of the image but reduced the role of the frame as a recognizable boundary, as it had been in preceding cultures” (Tarasov 2017).

The existing consensus in the Malevich studies suggests a certain agreement on the recognition of the general mystical orientation of his art and his philosophy.2 There is no specific need to dwell on all the details here; let us just briefly point only, for example, to the general anthro/theosophical dominance of the artist, which, incidentally, he shared with another father of world abstraction, the famous Dutch Avant-garde painter Piet Mondrian.3 For the sake of heuristic completion, we need also to point out the possibility of iconoclastic (and at the same time parodying) interpretative perception related to Malevich Quadrilateral/Rectangular (as well as Round & Oval) image series. This interpretation has its own valid arguments and has been analytically developed by several art historians. This is something that Mojmir Grygar labeled as ‘inner antagonism of Malevich’s thought’ (Grygar 1991).

The concealed ecstaticism of the black square has been observed by numerous critics, while the meaningful operations with the color energies encapsulated in these works correspond well with Malevich’s ecstatic white poems, which not so long ago became known to the general public.4 One can conclude that Malevich’s suprematist energism is intrinsically related to the energetic discourse of several mystical traditions at once. The aesthetical output generated by Malevich has relevance for the debate on the meditative reflection on religious apophaticism, in the context of the ‘deification of man’ and their further descension into nothingness; and this, as was already noted (Bax 1995), may refer directly to Jacob Boehme’s treatise Silence without Essence.5 As another scholar has aptly observed in her very recent monograph, ‘many Russian avant-garde artists reached back to pre-Petrine, or pre-Enlightenment Russian tradition as the most valid source of their culture. While Malevich claimed an entirely new beginning with his 1915 Black Square on White Ground, which cleaned the picture surface of all vestiges of previous painterly image-making, historically speaking his thinking had roots in religion adopting the rich and varied Russian tradition of icons and spirituality’ (Forgács 2022). (See also Kudriavtseva 2017).

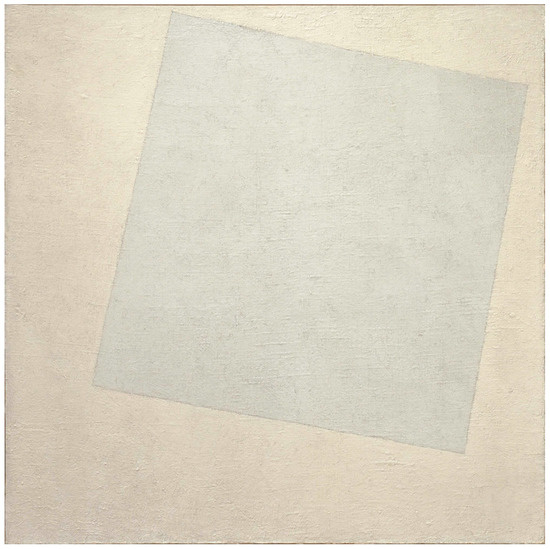

As Malevich observes,6 the religious person who knows God as singular7 ‘seeks to destroy his multitude in him’. Such a person is eternally in prayer and does not want to know or cognize anything, but reveals himself in nature and God. The one and indivisible God is in his dispersed world, and the world, not to disappear, must be in him as a place where nothing is dispersed. God is neither comprehensible nor ever visible. He is beyond knowledge; the divine whole nature is not visible, though we sometimes see it. Therefore, the holy person avoids knowing and becomes holy when he dissolves himself in God, dissolves himself in the unknowable. (There is always a danger of course of experimenting with sanity during this process see Sass 1992; Vöhringer 2007). Malevich’s mystical philosophy of representation appears in its dominating mainstream as a kind of objectless rebellion against traditional logocentricity and, more generally, against the material word of objects, marking a kind of enigmatic point of reference with a concealed interest in Russian religious philosophy of language, which manifested itself around the same time (Ioffe 2008b). Malevich, possibly through his close acquaintance Mikhail Gershenzon,8 was at least partially privy to the common teachings of the Russian religious philosophers of word/name who were developing, as is well known, the traditions of Byzantine Hesychast thought.9 This refers primarily to Pavel Florensky and Sergius Bulgakov, and somewhat later to Alexei Losev, to whom a connection might also have been made through the apocalyptic metaphysics of Nikolai Berdyaev. (Ioffe 2007). The ontology of nonobjectivity, which Malevich constructed, appears to have existed in precisely the same symbolic territory as the philosophy of word/name in its theory of divine energies of the no less divine name(s) as per the system of teachings attributed to Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (his Celestial Hierarchy of the Divine Names) later developed by Fr. Pavel Florensky (Tarasov 2002; Antonova 2020a, 2020b). Suprematist nonobjectivity, pictorial nothingness, may present purity of a receptive embodiment of the thought–conceptual core as it appears in the famous 1918 painting ‘White Square on a White Background’ (Figure 10), which allows the viewer to touch a radical new idea of the emerging modernist culture, based, as it were, on the ecstatic religious beliefs of the founder of suprematism.

Figure 10.

Kazimir Malevich. The White on White, 1918.

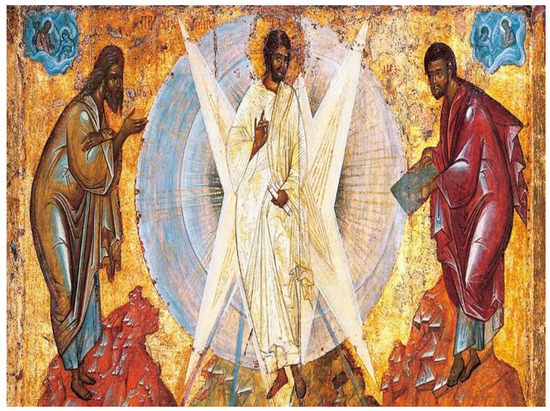

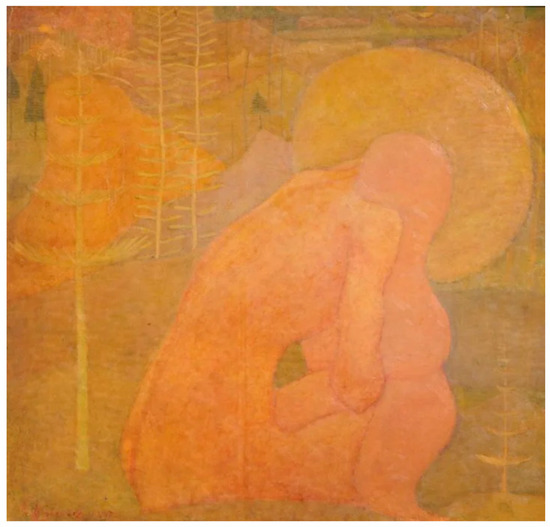

Here it should probably be emphasized that the concepts of the church and God are far from being alien to Malevich’s general outlook, and sometimes find their implicit presence in many examples of his work. The artist’s white square, as it seems, provides a fairly concrete idea and almost a direct reference to the Hesychast doctrine of divine energies, to historical discussions of the Light of Tabor and its miraculous immateriality.10 One might recall that the Light of Tabor in Byzantine theology is usually defined as an intense white substance (Lossky 1997). A discussion in this context should involve Malevich’s philosophy of light and color, including his ideas about how light breaking apart gives life to the many individual color-bearing matters that make up the full panorama of basic colors. Below one may initially compare the both traditions: Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 11.

The Orthodox icon representing Christ as a manifestation of the emanating divine Light of Tabor.

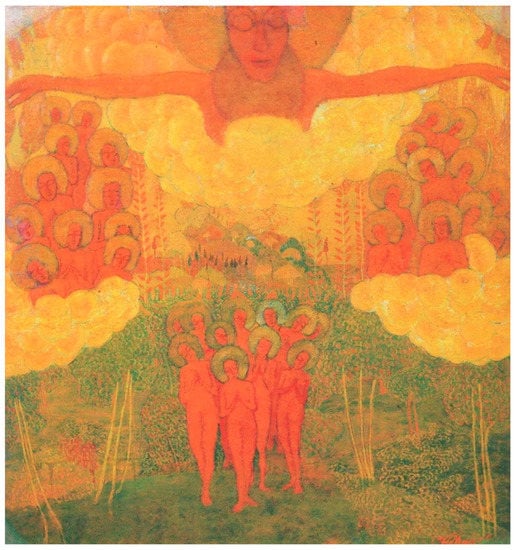

Figure 12.

Kazimir Malevich. The Triumph of Heaven, 1907.

Figure 13.

Kazimir Malevich, Prayer, 1907.

These unique series of Malevich’s ecstatic studies for fresco paintings, from the Yellow Series of 1907 (Figure 12 and Figure 13) executed probably on tempera/oil on a cardboard (the State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg), were recently extensively studied by an American-Ukrainian academic, Myroslava M. Mudrak (Mudrak 2015). Her thoughtful interpretation of Malevich religious imagery largely shares my earlier observations first presented at the University of Amsterdam Avant-garde congress (see Ioffe 2008b) that connect a Polish/Ukrainian/Russian artist with the Byzantine mystical body of theology as developed by Gregory Palamas. As the American scholar justly observes, ‘according to Palamas, the mystery of Christ’s Resurrection is encoded in the Cherubic hymn. That liturgical moment presents a shift of mode and tone within the celebration, allowing the faithful to convert their earthly station to become the surrogates of the angelic orders: Let us, who mystically represent the Cherubim … now set aside all earthly cares that we may welcome the King of all, invisibly escorted by angelic hosts. As the elect are delivered into ordinary space, so the faithful, too, assume a hallowed role in the divine condescension. The hymn signifies the interplay and merging of dual liturgical registers—the angelic and the earthly—creating a virtual dialogue between the two spheres in a temporally unified expression of worship and witnessing. The Byzantine historian, Cedrin (11th century) states that the Cherubic hymn was sung at the Divine Liturgy from the sixth century, beginning with an original request of Byzantine Emperor, Justin II’ (quoted in Mudrak 2015, p. 45).

Russian-American scholar Alexandra Shatskikh has rightly observed in her numerous studies, when interpreting Malevich’s mysticism, one should remember the artist’s evident philosophical and religious monism, his persistent confidence in a certain universal, unified, comprehensive grand idea, which his suprematist art is partially designed to describe and embrace. One can conclude that this absence of a polyphonic dialogue may contain not the least bit of spiritual originality of the suprematist painter, especially striking against the background of several emblematically polyphonic cultural icons of the Russian Silver Age. Malevich consistently preaches an ecstatic fusion with the universal cosmos representing his own special type of religiosity and mysticism (Cf. recently a theoretical essay by Irina Sakhno 2021).

In the discussion of the possible influence of Byzantine Hesychasm on Malevich’s work, we must find initial answers to several major questions that remain positively open. What was Malevich’s spiritual identity in strictly confessional terms? What was the initial influence of the Catholic religion of his father Severin? In what way did he forge his own path between the poles of the Western and Eastern types of Christian ritual? At the heart of the doctrine of the quietists is the notion that the highest Christian perfection consists in the divine tranquility (or stillness) of the soul, unperturbed by anything earthly. Intense inner prayer and direct mental contemplation of God can attain such tranquility. Quietism was rather popular in Russia during the Romanovs’ reign (late 18th–early 19th centuries), when polyvalent mysticism, as we know, reached a considerable flowering and a noticeable popularity in the higher strata of society. Modernism, and especially Slavic one seems to have a special conceptual and cultural connection to Byzantine tradition of artistic representation broadly understood. (Misler and Bowlt 2021; Shevzov 2010; Taroutina 2015, 2018; Nelson 2015).

There appear considerable similarities between Byzantine Hesychasm and Western quietism: there are common theological roots of the two systems of teachings, related to the close study of the heritage of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and his doctrine of divine names. Alexandra Shatskikh, in one of her essays, also notes the proximity of quietism and Hesychasm with a reference to Malevich’s philosophy (Shatskikh 2000), suggesting that because of Malevich’s monist worldview, active mystical dialogue with the deity, the idea of the inner prayer could be essentially rather foreign for the artist. Shatskikh argues Malevich would be more in tune with and congenial to the concept of Zen Buddhism taken from the Mahayana Buddhist canon; the scholar perceives the idea of nirvana as a space of general serene Nothingness as very similar to Malevich’s idea of ‘an Absolute Objectless Nothing’ (Shatskikh 2000; see also Sakhno 2021).

We can add that the teachings of the Buddhist East could have been known to Malevich through the popularization in the work of Madame Blavatsky, who devoted numerous pages of her various circulated writings to explaining the basic principles and attributes of Eastern religious metaphysics. In this vein, Berdyaev’s thoughts about the mysticism of Western quietism bring this context closer to the religious heritage of the traditional East. One may recall the rather enigmatic saying of the Apostle Paul: ‘Faith is the realization of the expected and the certainty of the unseen… By faith we know that the ages have been arranged by the word of God, so that out of the invisible things there came forth the visible things’ (Faith is the assurance (confirmation) of things hoped for (i.e., divinely guaranteed), and the evidence of things not seen) (‘Faith is the realization of what is hoped for, and evidence of things not seen’, Hebrews 11:1, 3, 6). Malevich’s ‘White Square on White’ (Figure 10) offers an esoterically encrypted representation of the Apostle Paul’s enigmatic notion of the ‘certainty in the invisible’ = ‘evidence of things not seen’, where the viewer in his own way guesses the invisible objectification of faith in the absence of a figurative image.

The synergetic nature of the universe, the visual subordination to higher energies, the all-pervading transcendence of the senses of being is perceived as a general hypostatic outline for any discussion of the spiritual affinity between Hesychasm and suprematism. Hesychasm essentially is a doctrine of energies, dominated by the metaphysical issue of light. (Maloney 1973). At first approximation, Malevich’s representational suprematism with its predominant attention to light & monochrome color, with its ideas of innovatively distributed energies, represents such a doctrine. A perceptive émigré art critic (and painter), Viacheslav Zavalishin, once interpreted (Zavalishin 1988) black square(s) as ‘gearboxes’ (literally ‘boxes of speeds’ (кoрoбки скoрoстей)) imprinted in them, which as if metaphorically noted the importance of the suprematist doctrine of energy and its ‘oikonomia’. As Malevich argues in his treatise ‘God Has Not Been Cast Off!’ (Bog ne skinut!) (Malevich 1995), describing the dialectical nature of the dynamics of movements of the divine absolute rest, ‘God is a Calm Peace, it is perfection, everything is achieved, the construction of worlds is finished, the movement is established in eternity. His creative thought moves, he himself is freed from madness, for he no longer creates; and the universe, like a mad brain, moves in a whirlwind of rotation, without answering to itself where and why. The universe is the madness of a liberated God, hiding in eternal peace’ (Malevich 1995, pp. 237–61; See also Barr 2007).

Another important study dealt with the Russian abstract avant-garde, especially Malevich and Kandinsky in the context of the Byzantine images, iconoclasm and Hesychasm, was a monograph published in the mid-1990s in Paris titled The Forbidden Image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm (Besançon 2000). Natalia Smolianskaia (2001) critiqued Besançon’s concept of ‘Abstraction as Negative Symbolism’, providing alternative interpretation in the context of the history of iconoclasm as rather (mis)represented by Alain Besançon.

In this case, the abstraction must apparently be regarded as a particular case of the multidimensional formation of the symbolic. This large-scale work by the French historian of culture, who has devoted much attention to Russian and Soviet issues, is interesting in particular because it demonstrates how certain key moments and stages in the general development of the concept of the image (mainly in the history of Byzantine iconoclasm, interpreted as a ‘tendency to combat the representation of the sacred and the divine’) serve to build a general modernist paradigm of artistic experiment. Interestingly, in Alain Besançon’s work, the sacral level of almost every creative potency is in fact isolated from any special dogma of any form of theology to which the author would eventually subscribe. In Besancon, the sacred appears as a certain functional technical aspect that has dominated the nature of the symbolic representation throughout many forms of art history. The French critic emphasizes symbolic overtones of the process of artistic visualization, including those areas that are traditionally reserved for the phenomenon of the ‘unrepresentable’. Another personified subject of Alain Besançon’s volume (along with Malevich), was the Russian/European radical abstractionist Vasily Kandinsky. One of Besançon’s discussions is related to the question of substitution of the iconic representation with theosophical engagement. The abstractionist ‘iconographer’ transforms the divine in his own way, setting his mystical experience in the focus of observation of the rhythm of the cosmic universe. This process Kandinsky could, as the common public knows, call the ‘spiritual in art’. It is no coincidence that Kandinsky, as well as Malevich, is known, in a theoretical sense, to be attached to the concept of ‘whitest color’ as the highest stage of radical abstraction of silence. Thus, in 1910, Kandinsky wrote about white: ‘White sounds like a silence that can be suddenly understood. White is Nothing that is young, or, even more precisely, it is Nothing pre-existent before birth’ (Malevich 2000b). This may among other things remind how the earth looked/sounded during the old days of the Ice Age.

As noted, having regarded art solely for its spiritual content-value, Kandinsky comes to the conviction that the means of expressing this unique content is a combination of nonobjective forms. Kazimir Malevich completed this evolution with the invention of suprematism. It was a decisive leap into nonobjectivity.11

Malevich and Kandinsky are the main cultural protagonists of the ‘new art’ of this semi-iconoclastic tradition of painting representing the figurative Nothingness (in both Sartrean and Heideggerian senses). This Nothingness, a propos, must never be confused with Emptiness. Both painters can personify two different visual and conceptual types of articulation of the attitude to the idea of semi-figurative abstraction related to the nonshaped Void. With Kandinsky, a special saturated positive topic of abstraction appears in the visual sphere, whereas Malevich, with his quite obsessive and uncompromising idea of ‘total representational zero’, can be characterized as a parallel version of the modernist zero-degree abstraction. For the German-Russian artist (Kandinsky), many of the basic constituent parts of artistic environments, linked on the basic elements of the construction of painting—brushstrokes, paint lines, and the texture of the canvas—are involved in the creation and accumulation of the spheres of the Pauline ‘certainty in the invisible’ as mentioned above the world of the astral–virtual experience of the artist, his intimate thoughts about the ‘spiritual in art’.

For the Polish/Ukrainian/Russian suprematist, the implicit conceptual reduction of the entire pictographic activity to a greater ‘zero of forms’, to the area of complete sensual isolation of the ‘plans’ of content and expression (планы сoдержания и выражения), turns out to be somewhat more significant than adhering to the familiar Renaissance professional activity of the artist. In accordance with the ideas of Malevich’s figurative theodicy, the Absolute produces/creates the Universe from a myriad of possible forms and their objectified embodiments, generating providential energy into dark vessels of figurative tiles barely accessible to our empirical mind.12

The motif of the enzymatic emptiness that pacifies the viewer, already mentioned earlier, will receive a very strong ‘life impulse’ in much later Russian postmodernist art (e.g. the notion of Buddhist emptiness in Moscow Conceptual School). In accordance with Besançon’s work, the Absolute God of the main Slavic abstractionist radicals Malevich and Kandinsky is meant to be slightly ‘objectified’ Void, a kind of ‘universal concept’, referring, through theosophy to various subspecies of contemplative nothingness, whereas any concrete and figurative embodiment of this concept is symbolically tabooed and presented as an idol forbidden to visualization, de facto unacceptable for modernist art, following the old conventions of Christian historical dogmatics of Byzantine and Isaurian origin.

Jean-Claude Marcadé deemed that Kazimir Malevich in his work fully embraces the eternal philosophical problems of the icon, perceives, as the scholar has put it, ‘the real presence of God not in the symbolic image, but in the relation of the latter to the absent fore-image (in contrast, the idol has no prototype, for it is a prototype of itself)’. According to J.-C. Marcadé, ‘in the final analysis we may venture to express our thought as follows: in the icon, through the absence of the Depicted, His presence is revealed. This is also where the entire essence of the black square runs through… The essence of the encounter with the icon is to see beyond the visible world the features of what is invisible’ (Marcadé 1978; quoted in Lukianov 2007). The first critical parallel between Malevich and icons was drawn by Alexandre Benois, albeit in an explicitly ironic way. Malevich himself is well known to have referred to Kvadrat as the ‘Divine Child-King’ in his discussion on art, thus making the Square closer to the image of an abstract Christ-infant (rather than say Louis-Dieudonné/Louis Quatorze).13

The Black Square was erected at the virtual Head of the early Petrograd exhibition (Figure 14):

Figure 14.

Kazimir Malevich. Black Square as the Divine Child-King (Tsarstvennyi Mladenets) at the Head of one of the first Avant-garde exhibitions in Petrograd. December 1915.

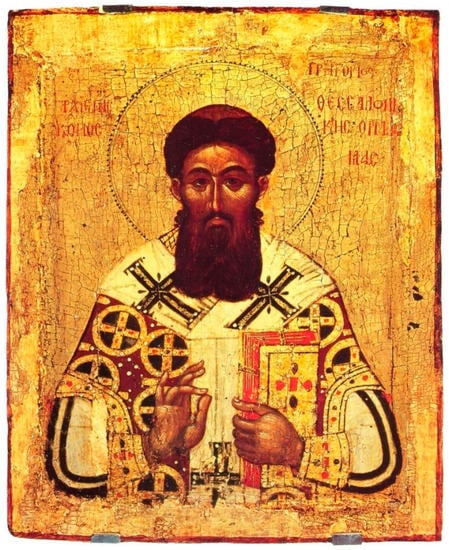

As it turns, the Light is one of the key concepts of Christian evangelism and the image provided in the Gospel for the true and sensual comprehension of God. ‘I am the light of the world’ (John 8.12), Christ says of Himself. God de facto comes into the world as light: ‘Light shines in darkness, and darkness has not consumed it’ (John 1.5). Orthodox theology constructs its teaching about God as the light working in the world, through which the world is saved, enlightened, and transformed. ‘You are the light of the world’ (Matt. 5.14), Christ says to his disciples, and this is the basis of almost all Orthodox ascetics. As Palamas noted in his Triads, ‘in the same way, the higher ranks of supra-worldly minds, under their dignity…’ They are filled not only with primordial knowledge but also with the first light, becoming partakers and contemplators not only of the Trinitarian glory, but also of Christ’s ultimate manifestation (and materialization) of divine light, which was once revealed to the disciples on the Mount Tabor (Bibikhin 2003). Those who are worthy of this contemplation are initiated into the God-generating light of Christ, being directly communicated to the hidden lights, according to the Coptic monk and philosopher Macarius of Egypt (c. 300–391) who calls the light of grace to be actually the food of the heavenly inhabitants: ‘The whole mental intangible order of the beings above the world is the most obvious evidence of the light-bearing humanity of the Word’ (Makarov 2003).

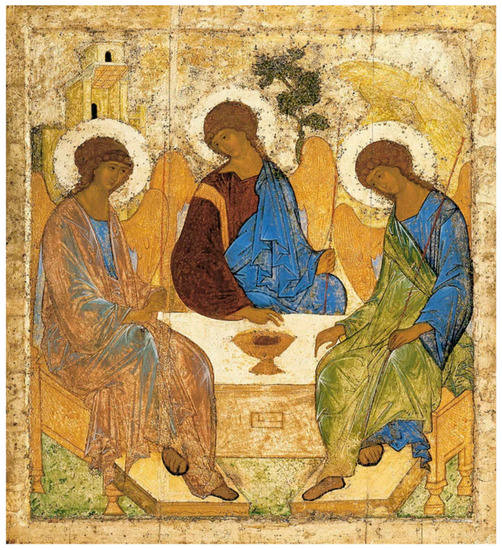

The prayerful contemplation of the sacred Light of Tabor, the light that the apostles allegedly saw during the transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor, was of great value for Hesychast spiritual practice. Through this light, nonmaterial in its essence, as the Hesychasm taught, the ascetic enters into communion with the Incomprehensible (and unattainable) Absolute. Having been filled with this light, in his life-temporal, sensual shell, he becomes a part of the divine life; in essence, he is transformed into a radically new creature. In iconography, great importance is assigned to the ultimate infinity of space, achieved through, as Pavel Florensky observes (Florensky 2003), a reverse perspective, whereas the ‘one-dimensional/ one-eyed’ direct perspective can only convey a finite world, as if falling into a distant spatial point.14 However, despite the importance of the problem of space, the main thing in iconography is the Image, to whom space is wholly subservient. In the direct (technocratic) perspective, the objects depicted are such moments of space, entirely subject to the dictate of its modulation. The direct perspective is a window to this world; it appears to us as a kind of virtual breakthrough in its own fixed limits. In this connection, it would be logical to conclude that Andrei Rublev’s Trinity (Figure 15) is in a way the quintessence of the artist’s visual Hesychast inner sermon, which leads his prayer by speculative means available to him.15

Figure 15.

Andrei Rublev, Holy Trinity, 1425–1427.

According to Malevich’s contemporary, religious philosopher of science and language Father Pavel Florensky, in a descent of God to man, that is, to the mortal physical existence on earth, lies the inverse factor of human rapture to God, the Divine Fire, which, in this connection, generates the Light. Light, in turn, emanates the conceptual Color and the appropriate Spiritual Sacrament. In such an intimate process of seeing the Iconic Order, a kind of unearthly silence and will-be-extended, peace and quietness emerges (Florensky 2003). Creating the series of white rectangles (Figure 10) Kazimir Malevich offers a possibly similar eternal rest at his treatise of (nearly) the same name (Eternal peace): ‘Unobjective action moves silently in its virtual madness, no differences are heard in it, there is a dynamic silence in it’ (Malevich 2000b).

The notable ‘negative’ theorist of Hesychasm, Nikephóros Gregorás, stated that God’s energies deify not only the mind, the ‘inner self’, but also the outer flesh; therefore, the body of the saint appears as if turned off from the natural order of nature and can no longer be depicted as such.16 By the action of noncorporeal energies, the earthly flesh itself is burned away; it escapes from the visible world, escapes the usual gaze. Meanwhile, St. Gregory Palamas (Figure 16) instructs his listener and reader: ‘accustoming the mind not to retreat to the surrounding and not be mixed with that, make it strong to focus on the one’. Further, ‘forgetting the lower, the secret knowledge of higher… this is the true mental work, climbing to the right contemplation and vision of God. The triunity of God is neither the sum, nor the three nor the one, but the unity of identity and difference’ (Bibikhin 2003). This largely makes up St. Palama’s politics of Trinitarian identity.

Figure 16.

St. Gregory Palamas. A Byzantine Saint-Philosopher.

Of all the historical Avant-garde, the figure of Malevich provides interesting grounds for considering radical artistic abstraction sub specie the tradition of Hesychast theology. Here one may see, once again, the importance of the ‘departure’ of the represented object from the expectedly familiar sensation, from the ground of the senses of the visual, into the sphere of the serene and subdued abstraction (Figure 17) of the primordial Zero of Forms.17 The Jungian interpretation of the artist’s ‘project of squares’ is supported also by some testimonies of Malevich’s contemporaries and listeners, seems interesting and close to the main points of this suggestive discourse.18 The mystical depth of the visible, accessibly outlined in Malevich’s most ‘Hesychastic’ work, The White Square on a White Background (Figure 10), is abundantly interpreted by many competent researchers.19

Figure 17.

Kazimir Malevich. Black Square. The painted structure of Malevich’s coloring resembles to some extent the known traditional technique of the Orthodox Icon painting.

Tomáš Glanc, in his penetrating analytical essay ‘The Word and the Text of Kazimir Malevich’ (Glanc 1996), is emphasizing a certain ‘mimetic’ distance necessary for understanding the religious component of Malevich’s work, and observed that the general mimetic skepticism, which first manifests itself in Symbolism and reaches its extreme limits in the avant-garde, should be aptly illustrated by a quote from Malevich’s text (1924): ‘No crucifixion of Christ is like reality because it is artistic.… But only art is capable of transforming being and image, of embodying myth, just as in religion every phenomenon is a reflection of God’ (see Glanc 1996). To this one may add observations left by Jerzy Faryno, expressed in a thorough essay, ‘The Alogism and Isosemantism of the Avant-Garde’ (Faryno 1996), where he contextually describes the hieratic and ciphered essence of the crypto-image of the fish as the secret sign of Christ, as the designation of the catacomb mystic guardians of the first centuries of Christianity, which is known to the initiated.

Faryno’s general reasoning on the example of a quite figurative ‘traditionally modernist’ painting by Malevich may permit a relatively firm conclusion about the extraordinary importance of the iconographic presence of Christ and, more broadly, ‘church attributes’ in the early stages of “suprematist art”, answering, even partially, the important question mentioned at the beginning of our discussion about the need to understand the religious affiliation of the artist. In the same way, Jerzy Faryno (1996) considers a modeling and image-semantic parallel in the sphere of constructing the space of objects of Malevich’s work corresponding to the Christian icon. Taking into account all the facts discussed, the response to this question should emerge more unambiguously in favor of the Christian mystical variant of the artist’s visual performance. The candle, the church, and the fish are mutually corroborated as manifestations of the same semiotic (symbiotic) system, implementing the implicit principle of isosemantism, thereby opening a semantic perspective on some other motifs as well. Here, it is only possible to substantiate the connection between the mystical fish and the candle in even greater detail. Malevich outlined only the principal echo of the form of the flame with the hint of the fish itself.

All the theoretical and iconographical intersections and possible implicit correspondences we have outlined above, as well as some specific facts of Malevich’s metaphysical art that champions a specific type of creative semiosis (Faryno 1996), permit one to assert with more confidence the essential crossover between Kazimir Malevich and the spiritual energies of Orthodox icons on one hand and Hesychast prayer on the other. Suprematist theory of representation as championed by Malevich seems quite openly enrooted in non-artistic philosophical grounds. Part of this non-art backgrounds should be of course perceived and discerned in Nature. As Isabel Wünsche has emphasized using the example of Malevich’s colleague and friend Mikhail Matiushin, art may be primarily perceived as “manifestation of a tendency to grow toward light and nourishment” (Wünsche 2015, p. 92): this invokes and involves faculties of a tree, but also brings into memory a Hesychast inner prayer and the Light of Tabor. Working on the first Futurist (anti)opera that was supposed to celebrate a synesthetic victory over the Sun, Matiushin together with Malevich (as well as Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh) creatively contributed towards “a synthesis of all forms of sensory perception and knowledge acquisition”. As “a new stadium” of Avant-Garde world-understanding seems to be implicitly Hesychast-scented in its instantaneous “allowing one to grasp the true reality” behind the appearances of the visible world which evidently “represents a new synthesis of perception enabling one of simultaneous seeing and knowing” (Wünsche 2015, p. 112).

Generally speaking, icons prove to be highly relevant to Slavic and Russian avant-garde in its totality (see Spira 2008; Tarasov 2011; Gill 2016). In this context, the Hesychast religious philosophy may become the necessary descriptive tool offering a historical–intellectual and general–cultural framework heuristically describing the conceptual paradigm of Malevich’s philosophy of representation in its holistic entirety, where too obvious similarities between his works and the legacy of the Byzantine Hesychasm can hardly be accidental. The future task of comparing Malevich’s aesthetic fashions with other fellow Avant-gardist personae will include analyzing the profound interest in conceptual engaging with spiritual visuality and especially with a religious philosophy of the European Orient as explicated in Byzantine Orthodox (and at times heterodox) systems of thought.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Malevich’s suprematist theory has been analyzed in many scholarly works. See, for example, a valuable pioneering monograph by Larissa Zhadova (first published in German): (Zhadova 1982). See also a number of works by an American Malevich scholar, Charlotte Douglas (1994b, pp. 164–98). See also her other studies: (Douglas 1980; 1986); on the mysticism of Black Square see also (Simmons 1980; Milner 1996; Martineau 1977). |

| 2 | On the mystical (and popular–religious) component of Malevich’s work, see the analytical catalog: (Cortenova and Petrova 2000a). See also (Cortenova and Petrova 2000b). For general observations, see also (Mudrak 2015; Sakhno 2021; also Blank 1995; Bowlt 1986, 1991, 2008; Sarabianov 1993, pp. 7–21). As one may not fail to remember, ‘Once Malevich began to take art classes and learn about art, he openly acknowledged the effect of icons on shaping his aesthetic ideas: I felt something native and extraordinary in icons… I felt a certain bond between peasant art and the icons’. Quoted in Mudrak (2015, p. 38). |

| 3 | On Mondrian’s theosophical interests, see, for example, brief considerations by the distinguished cultural historian Peter Gay: 1976. Also, cf. Champa (1985) and Jaffé (1970). In addition, important articles from a valuable and wide-ranging book on modernist avant-garde art and the occult tradition should also be mentioned: (Apke et al. 1995; Marty Bax 1995; Wladimir Kruglow 1995; Anthony Parton 1995). See also the valuable article by Agnès Sola (Sola 1985, pp. 576–81). See also a volume of interest in this context: (Golding 2000). |

| 4 | See Malevich’s published ‘white’ poems in Malevich (2000a). For an analysis of these texts (including the so-called ‘Liturgical Cycle’, which corresponds semantically with the iconographic analysis of ‘An Englishman in Moscow’ by Jerzy Faryno 1996). Cf. also Marinova (2004, pp. 567–92). |

| 5 | Böhme’s apology of mystical silence was also appreciated by the English quasi-Protestant Quakers. A known quote from Böhme tells, ‘When thou art quiet and silent, then art thou as God was before nature and creature; thou art that which God then wats; thou art that whereof he made thy nature and creature: Then thou hearest and seest even with that wherewith God himself saw and heard in thee, before every thine own willing or thine own seeing began’. See this in: (Hartmann 1977). (See also Leloup 2003). |

| 6 | I have used an edition of Malevich’s works, edited by Alexandra Shatskikh: Malevich (1995–2004). See also Marcadé (1978, pp. 224–41). For similar themes, see John Bowlt (1990, pp. 178–89). See generally some recent studies as (Lodder 2019; Nakov 2010). |

| 7 | The Hebrew concept of God is demonstratively grammatically plural (Elohim) or neuter (i.e., Elohút - the godly essence of Godhead). |

| 8 | On the connection between Malevich and Gershenzon, see their exchange of letters (1918–1924), (Malevich 2000b, pp. 327–54). |

| 9 | On Hesychasm in historical and theological illumination, see the eminent studies of the late Archpriest John Meyendorff (Meyendorff 2003, pp. 277–36 and, Meyendorff 1999). See also a special collection of Meyendorff’s research published in Variorum: 1974. See also (Lossky 1997; LaBauve 1992). Another recent work concerned with Hesychasm and Byzantine mysticism: (Andreopoulos 2005). As regards the historical and art history study of iconoclasm, since the pioneering French monograph by André Grabar, which has been republished many times by (Grabar 1984), an enormous number of valuable works have been published. See also (Ioffe 2005, pp. 292–315). |

| 10 | There are quite a few interesting works devoted to various aspects of Russian ‘philosophy of name’. For the most important example, one must mention a series of very insightful studies by the late Moscow philosopher Larissa Gogotishvili (1997a, 1997b). See also Natalia Bonetskaia (1991–1992, pp. 151–209). Cf. a series of papers by Moscow art historian Tatiana Goriacheva on the metaphysics of Kazimir Malevich’s pictorial activities (from a somewhat different perspective than the above): (Goriacheva 1993a, pp. 49–60; 1993b, pp. 107–19; 1999, pp. 286–301). (See also Marcadé 1990; Douglas 1980, 1986; Mudrak 2017). |

| 11 | Oleg Khanjian, quoted in Lukianov (2007). There are also valuable reflections of Dmitry Sarabianov: ‘the mesmerizing influence of the Black Square is connected with its ability to concentrate in itself the infinite world space, to transform into other universal formulas of the world, to express everything in the Universe, concentrating it all in an absolutely impersonal geometrical form and impenetrable black surface. Malevich was drawing a conclusion from the entire fruitful period of symbolic thinking in European culture with his program picture, moving from a symbol to a formula, a sign that acquires an identity’. See ibid. |

| 12 | This description might even sound a little “Gnostic” to some critics. As Malevich reports in his famous treatise God Is Not Discounted (Not Cast Down): ‘[Indeed] it is not surprising that God built the universe out of nothing, just as man builds everything out of nothing of his own image, and that which is imagined does not know that [he] is the very Creator of everything and created God—also as His image [of Him]. See Malevich, God Is Not Discounted! (God has not been cast off!) (Malevich 2000b; Malevich 1995). See also Barr (2007). |

| 13 | Icon painting in general seems to have been a major influence on the work of many Russian avant-garde artists. See, in the context of Tatlin’s prerevolutionary tumultuous fascination with frescoes and icons, Gassner (1993, pp. 124–63). |

| 14 | On the inverse perspective in icons, see the classic work by Florensky (2003, pp. 133–41). |

| 15 | Here one should recall the role of ‘light’ and its perception in semiotics and the iconic essence, which is also discussed by Leonid Uspensky, the namesake of the pioneer of Soviet semiotics, Boris Uspensky. See: (Léonid Ouspensky 2017; Léonid Ouspensky 1980). Cf. the fundamental essay by Boris A. Uspensky, ‘Semiotics of the Icon’ (Uspensky 1995, pp. 221–96). On the role of light, see also Viktor Zhivov (2002, pp. 40–72). Generally see: (Meyendorff 1974, 1987). |

| 16 | Some information on Nikephóros Gregorás and his polemic with Hesychasm (from 1346 onwards), Malevich could have acquired from many sources. Let us mention, for example, Guillana (1926). |

| 17 | For the general scholarly overview of the Russian avant-garde and icons see (Spira 2008; Gill 2016; Bowlt 2022). |

| 18 | Cf. Lukianov’s analysis from the aforementioned essay, referring to the discussion of the embodiment of the archetypal image of the contemplative Deity in the quadruped, which is contained in the book Psychology and Religion by the Swiss philosopher and psychologist Carl Gustav Jung. ‘Malevich argued that each color has its own form. The black square is the geometric form in which color is maximally tense. As an exercise, he recommended finding on an orange square that size of a green circle, until that circle moves when you look closely’ (see Lukianov 2007). |

| 19 | According to J.-C.Marcadé’s observations, Malevich defied any possibility of fully conveying the visible by previous methods of depicting reality. ‘Going from conclusion to conclusion, by simplifying the external signs of real things, he came to the conclusion that a pure sense of the object could only be achieved through intuition alone, penetrating to the very essence of creation. Starting from the geometric square, Malevich proved on the flat surface the solution to the possibilities of suprematist movement: the power of immobility, the dynamics of rest, the potentiality of magnetism and mystical depth. The highest point of his aesthetic theories is the White Square on a White Background of 1918, expressing the beginning and the end of the created world, the purity of creative human energy and the unperturbed calm of nonexistence’ (Marcadé 1978; Lukianov 2007). Interpreting the suggestiveness of white color for ideology and ideography of ‘figurative Nothing’ by Malevich involves ethnopoetic tradition and folklore mythology, in particular the ambivalent legacy of Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasiev: ‘White color traditionally played the key role both in ancient Russian pastoral cosmology and in mythology of other peoples. The image of a white stone on the sea, and sometimes on an island allows to reconstruct the associative chain germ-cheese/cottage-island/stone. The sea is also sometimes referred to as a white substance. In various versions of the ancient Indian myth of Creation by means of churning, the sea is either called milky or, having thickened, it turns into dense milk and butter. In the mythology of the Mongolian people(s) the solid earth is created by stirring the milky sea-ocean. The process of the emergence of the germ within the milk moisture was largely thought of by analogy with the process of fermentation. The semantic series of representations concerning cheese/cottage cheese is greatly expanded if they are considered in the cosmogonic aspect… To this day, the world around us is often referred to as ‘white light’: to live in white light, to walk in white light. And the white stone is mentioned in the Apocalypse of John the Theologian: ‘He who has an ear (to hear), let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches: to him who overcomes I will give to taste the hidden manna, and I will give him a white stone, and a new name written on the stone, which no one knows, except he who receives it’’ (Quoted in Lukianov 2007). |

References

- Andreopoulos, Andreas. 2005. Metamorphosis: The Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography. Crestwood and New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ankersmit, Frank R. 1997. Aesthetic Politics. Political Philosophy Beyond Fact and Value. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Antonova, Clemena. 2015. Visuality among Cubism, Iconography, and Theosophy: Pavel Florensky’s Theory of Iconic Space. Journal of Icon Studies 1. [Google Scholar]

- Antonova, Clemena. 2020a. The Icon and the Visual Arts at the Time of the Russian Religious Renaissance. In Oxford Handbook of Russian Religious Thought. Edited by George Pattison, Caryl Emerson and Randall A. Poole. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 412–33. [Google Scholar]

- Antonova, Clemena. 2020b. Visual Thought in Russian Religious Philosophy: Pavel Florensky’s Theory of the Icon. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Apke, Bernd, Veit Loers, Pia Witzmann, and Ingrid Ehrhardt, eds. 1995. Okkultismus und Avantgarde: Von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900–1915, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. Ostfildern: Edition Tertium. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, Adrian. 2007. From Vozbuzhdenie to Oshchushenie: Theoretical Shifts, Nova Generatsiia and the Late Paintings. In Rethinking Malevich. Edited by Charlotte Douglas and Christina Lodder. London: Pindar Press, pp. 203–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bax, Marthy. 1995. Theosophie und kunst in den Niederlanden 1885–1915, Die Theosophische Gessellschaft. In Okkultismus und Avantgarde: Von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900–1915, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. Edited by Bernd Apke, Veit Loers, Pia Witzmann and Ingrid Ehrhardt. Ostfildern: Edition Tertium, pp. 245–66, 282–321. [Google Scholar]

- Besançon, Alain. 2000. Image interdite. The Forbidden image: An Intellectual History of Iconoclasm. Translated by Jane Marie Todd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bibikhin, Vladimir. 2003. Sv. Gregory Palama. Triady v zaschity sviachenno-bezmolstvuiuschikh. Sankt Petersburg: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, Sara. 1999. Modernism and the Politics of Culture. In The Cambridge Companion to Modernism. Edited by M. Levenson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 157–74. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, Ksana. 1995. Lev Tolstoy’s Suprematist Icon-Painting. Elementa: Schriften zur Philosophie und ihrer Problemgeschichte 2: 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetskaia, Natalia. 1991–1992. O Filologiheskoi shkole P.A. Florenskogo. Studia Slavica Hung 37: 151–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 1986. Esoteric Culture and Russian Society. In The Spiritual in Abstract Painting 1890–1985. Los Angeles and New York: Abbeville Press, pp. 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 1990. Malevich and the Energy of Language. In Kazimir Malevich, 1878–1935. Edited by Jeane D’Andrea. Los Angeles: The Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Culture, pp. 178–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 1991. Orthodoxy and the Avantgarde: Sacred images in the work of Goncharova, Malevich, and Their contemporaries. In Christianity and the Arts in Russia. Edited by Milos M. Velimirovic and Willian C. Brumfield. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 2008. Moscow & St. Petersburg 1900–1920: Art, Life, and Culture of the Russian Silver Age. London: Vendome Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 2022. ‘Wings of Freedom’: Petr Miturich and Aero-Constructivism. Arts 11: 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Malcolm, and James McFarlane, eds. 1976. Modernism: 1890–1930. London: Harvester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Will, and Charles Esche. 2007. Art and Social Change. London: Tate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, Peter, Andrzej Gasiorek, Deborah Longworth, and Andrew Thacker. 2010. The Oxford Handbook of Modernisms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bru, Sascha. 2006. The Phantom League. The Centennial Debate on the Avant-Garde and Politics. In The Invention of Politics in the European Avant-Garde: 1906–1940. Edited by Sascha Bru and Gunther Martens. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bru, Sascha, and Jan Baetens. 2009. Europa! Europa? The Avant-Garde, Modernism and the Fate of a Continent. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bürger, Peter. 2014. Teoriia Avangarda. Moskva. First published 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Champa, Kermit. 1985. Mondrian Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cortenova, G., and E. Petrova. 2000a. Kandinsky, Chagall, Malevich e lo spiritualismo russo: Dale collezioni del Museo statale russo di San Pietroburgo, a cura di Giorgio Cortenova, Evgenia Petrova, Milano. Singapore: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Cortenova, Giorgio, and Evgenia Petrova. 2000b. Kazimir Malevich e Le Sacre Icone Russe: Avanguardia e Tradizioni. Verona: Electa. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy, Michael, and Mathias Nilges, eds. 2016. The Contemporaneity of Modernism: Literature, Media, Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Charlotte. 1980. Swans of the Other Worlds: Kazimir Malevich and the Origins of Abstraction in Russia. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Charlotte. 1986. Beyond Reason: Malevich, Matiushin, and their Circles. In The Spiritual in Abstract Painting 1890–1985. Los Angeles and New York: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, pp. 189–99. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Charlotte. 1994. Kazimir Malevich. New York: H.N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Erjavec, Aleš, ed. 2015. Aesthetic Revolutions and Twentieth-Century Avant-Garde. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eysteinsson, Astradur. 1990. The Concept of Modernism. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eysteinsson, Astradur, and Vivian Liska, eds. 2007. Modernism (2 Vols). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Faryno, Jerzy. 1996. Alogism i izosemantism Avant-Garda, na primere Malevicha. Russian Literature XL-I. [Google Scholar]

- Florensky, Pavel. 2003. Obratnaia perspektiva. Esteitcheskoe samosoznanie russkoi kultury. 20e gody. Moskva: RGGU, pp. 133–41. [Google Scholar]

- Forgács, Éva. 2022. Malevich and Interwar Modernism Russian Art and the International of the Square. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Gassner, Hubertus. 1993. Konstruktivisty na puti modernizatsii, Velikaia Utopia. Russkii i Sovetskii Avant-Garde 1915–1932. Bern and Moskva: Guggenheim Museum, pp. 124–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Charlotte. 2016. A ‘Direct Perception of Life. How the Russian Avant-Garde Utilized the Icon Tradition’. IKON 9: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimbutas, Marija. 1974. The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 7000 to 3500 BC: Myths, Legends and Cult Images. London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glanc, Tomáš. 1996. Slovo i tekst Kazimira Malevicha. Blokovskii Sbornik XIII: 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Glisic, Iva. 2020. The Futurist Files. Avant-Garde, Politics, and Ideology in Russia, 1905–1930. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gogotishvili, Larisa. 1997a. Losev, hesychasm, platonism. In Losev A.F. Imia. Sankt Petersburg: Aleteia. [Google Scholar]

- Gogotishvili, Larisa. 1997b. Linguistischeskii aspect triokh versii imiaslavia. In Losev A.F. Imia. Sankt Petersburg: Aleteia. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, John. 2000. Paths to the Absolute: Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky, Pollock, Newman, Rothko, and Still. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goriacheva, Tatiana. 1993a. Malevich i metafizicheskaia zhivopis’. Voprosy iazykoznania 1: 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Goriacheva, Tatiana. 1993b. Malevich i Renaissance. Voprosy Iskusstvoznania 2–3: 107–19. [Google Scholar]

- Goriacheva, Tatiana. 1999. Tzartstvo dukkha i tzarstvo kesaria. Sudba futuristicheskoi utopii v 1920–1930g. Iskusstvoznanie 1: 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, André. 1984. L’iconoclasme byzantin: Le dossier archéologique, 2e rev. et augm ed. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 2008. Art Power. Cambridge: Cambridge Mass. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 2012. Politika Poetiki. Moskva. [Google Scholar]

- Grygar, Mojmír. 1991. The contradictions and the unity of Malevich’s world-outlook. Avant-Garde. Interdisciplinary and International Review 5/6: 181–206. [Google Scholar]

- Guillana, Rodolphe. 1926. Essai sur Nicéphore Grégoras. Paris: P. Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- Hadjinicolaou, Nicos. 1982. On the Ideology of Avant-Gardism. Praxis: A Journal of Radical Perspectives on the Arts 6: 39–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Franz. 1977. Jacob Boehme: Life and Doctrines. Blauvelt: Steinerbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderliter, Beth, Vered Maimon, Jaleh Mansoor, and Seth McCormick. 2009. Communities of Sense: Rethinking Aesthetics and Politics. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnov, Emily, Lauren Rosenblum, and Laurel Harris, eds. 2013. Communal Modernisms. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2005. Liki tishiny. Novejshaya istoriya russkogo eksperimental’nogo stikha Sub Specie Hesychiae: Tri skhematicheski vzyatye poetiki umnogo delaniya. Russian Literature LVII: 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2007. Russkaia religioznaia kritika jazyka i problema imiaslaviia (o. Pavel Florenskii, o. Sergii Bulgakov, A.F. Losev). Kritika i Semiotika 11: 109–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2008a. Diskursy telesnosti i erotizma v literature i kul’ture. Epokha modernisma. Moskva: Ladomir. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2008b. K postanovke problemy: Malevich i hesychasm. In The Case of the Avant-garde: Delo Avangarda. Edited by Willem G. Weststeijn. Amsterdam: Pegasus, vol. 8, pp. 581–617. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2008c. Velimir Khlebnikov, Islamic mysticism, and Oriental Discourse. In Doski sud’by Velimira Khlebnikova: Tekst i konteksty, stat’i i materialy. Edited by N. Sirotkin, V. Feschenko and N. Gritsanchuk. Moskva: Tri Kvadrata Academic Publishers, pp. 547–637. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2010. Ideologia avangarda kak fenomen. Russian literature 67: 417–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2011. The Legacy of Experiment in Russian Culture. Russian Literature 69: 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2012a. The Notion Ideology in the Context of the Russian Avant-Garde. Cultura. International Journal of Philosophy of Culture and Axiology 9: 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2012b. The Tradition of Experimentation in the Russian Avant-Garde. In The Russian Avant-Garde and Radical Modernism. Boston: Academic Studies Press, pp. 454–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2017. The Politics of Modernism in Russia. Russian Literature 92: 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Jeremija. 2006. Simvolizm (misticheskiy idealizm), Konstruktivizm, Ekspressionizm i surrealism. In Izbrannoe. Edited by M. S. Kagan, I. P. Smirnov and N.Ia Grigorieva. Sankt Petersburg: Petropolis, pp. 197–251. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé, Hans Ludwig. 1970. Piet Mondrian. New York: H. N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliney, Peter. 2016. Modernism in a Global Context. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, Frederick. 1985. Modern and Modernism: The Sovereignty of the Artist 1885–1925. New York: Atheneum. [Google Scholar]

- Khardzhiev, Nikolai. 1976. K istorii russkogo avangarda. Stockholm: Hylaea Prints. [Google Scholar]

- Khlebnikov, Velimir. 1986. Tvoreniia. Moskva: Sovetskii pisatel’. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyun Jin. 2010. Herodotus’ Scythians Viewed from a Central Asian Perspective, Its Historicity and Significance. Ancient West & East 9: 115–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglow, Wladimir. 1995. Die Epoche des grossen Spiritismus—Symbolistische Tendenzen in der fruhen russischen Avantgarde. In Okkultismus und Avantgarde: Von Munch bis Mondrian, 1900–1915, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. Edited by Bernd Apke, Veit Loers, Pia Witzmann and Ingrid Ehrhardt. Ostfildern: Edition Tertium, pp. 175–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kudriavtseva, Ekaterina. 2017. Kazimir Malevich. Metamorphosy chernogo kvadrata. Moskva: NLO. [Google Scholar]

- Kunichka, Michael. 2015. ‘Our Native Antiquity’ Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Culture of Russian Modernism. Boston: Academic Studies Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaBauve, Hébert. 1992. Hesychasm, Word-weaving, and Slavic Hagiography: The Literary School of Patriarch Euthymius. (Sagners slavistische Sammlung). Munchen: Otto Sagner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Leloup, Jean-Yves. 2003. Being Still: Reflections on an Ancient Mystical Tradition. Mahwah: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, Michael. 2011. Modernism. New Haven: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Livshits, Benedikt. 1931. Hylea. New York: Burliuk. [Google Scholar]

- Lodder, Christina. 2019. Conflicting Approaches to Creativity? Suprematism and Constructivism. In Celebrating Suprematism. New Approaches to the Art of Kazimir Malevich. Edited by Christina Lodder. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Lossky, Nikolai. 1997. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lukianov, E. A. 2007. Lev Tolstoy v suprematicheskom zerkale Kazimira Malevicha. Chelovek 6: 157–68. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, D. I. 2003. Antropologia i kosmologia sv. Griogoria Palamy. Abisko: SpB, Abyshko. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995. ‘Bog ne skinut!’. In Sobranie Sochinenii. Moskva: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 2000a. Poezia. Moskva: Epifania. [Google Scholar]

- Malevich, K. 2000b. Sobranie Sochinenii. Moskva: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, George. 1973. Russian Hesychasm: The Spirituality of Nil Sorskij. Mouton: The Hague. [Google Scholar]

- Marcadé, Jean-Claude. 1978. An Approach to the Writings of Malevich. Soviet Union/Union Sovetique 5: 224–41. [Google Scholar]

- Marcadé, Jean-Claude. 1990. Malévitch. Paris: Casterman, Nouvelles Editions françaises. [Google Scholar]

- Marinova, Margarita. 2004. ‘Malevich’s Poetry: A ‘Wooden Bicycle’ against a Background of Masterpieces?’. Slavic and East European Journal 48: 567–92. [Google Scholar]

- Markov, Vladimir. 1968. Russian Futurism: A History. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau, Emmanuel. 1977. Malevitch et la philosophie. La question de la peinture abstraite. Lausanne: L’age d’Homme. [Google Scholar]

- Meyendorff, John. 1974. Byzantine Hesychasm: Historical, Theological and Social Problems. London: Variorum Reprints. [Google Scholar]

- Meyendorff, John. 1987. Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes. New York: Fordham University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyendorff, John. 1999. Gregory Palamas and Orthodox Spirituality. New York: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyendorff, John. 2003. Sviatoj Grigorii Palama i pravoslavnaja mistika. O vizantijskom hesychazme i ego roli v kul’turnom i istoricheskom razvitii Vostochnoj Evropy v XIV veke. In Istorija Tserkvi i vostochno-christianskaia mystica. Moskva: Pravoslavnyi Svjato-Tikhonovskii Bogoslovskii institut, pp. 277–336, 561–74. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, J. 1996. Kazimir Malevich and the Art of Geometry. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Misler, N., and J. Bowlt. 2021. Catherine’s Icon: Pavel Filonov and the Orthodox World. Religions 12: 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]