Abstract

The article discusses an artistic method of the post-Soviet artist Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe (1969–2013) as the nexus of several traditions embedded in modernist legacy. His main genre is remastered (scratched) photographs depicting him impersonating various historical and fictional characters, from Marylyn Monroe (whom he considered his alter ego) to Hitler, Jesus Christ, and Putin. His art and artistically designed image creatively develop the tradition of modernist life-creation (zhiznetvorchestvo), which he enriches by camp, thus becoming a pioneer of this elusive sensibility in post-Soviet culture. Camp, in turn, facilitates Mamyshev-Monroe’s self-fashioning as the trickster whose transgressivity and ambivalence absorb his queerness and drag spectacles, and whose hyperperformativity manifests itself in his performative art. The article analyzes how Mamyshev-Monroe appropriates various cultural material in the trickster’s way by using camp for its critique and deconstruction. The case of Mamyshev-Monroe is especially important since it demonstrates the limits of the trickster’s transgression that resists its instrumentalization by the authoritarian state.

Vladislav Mamyshev, better known under the pseudonym “Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe” for his frequent impersonations of Marilyn Monroe, was one of the most scandalous and willfully kitschiest representatives of the Leningrad-Petersburg group of “New Artists” that included Timur Novikov, Oleg Kotelnikov, Georgii Gur’ianov, Evgenii Yufit, and Sergei Bugaev (Afrika), among others. Although the group was created in 1982, it shaped the core of the first post-Soviet generation of Leningrad artists, who were both inspired and intoxicated by the new freedoms of the Perestroika period and the anarchic 1990s. The group’s aesthetic was eclectic and included influences of Russian futurism, neoprimitivism, expressionism, and European Dada mixed with postmodernist playfulness and daring performance practices (see Andreeva and Podgorskaia 2012). Mamyshev-Monroe gravitated more to the postmodernist end of the spectrum adopted by the New Artists. Among his favorite genres were modified photographs and performances, which typically, albeit not always, represented the artist himself metamorphosing into historical or fictional characters, tinted with a strong sense of humor and irony.1

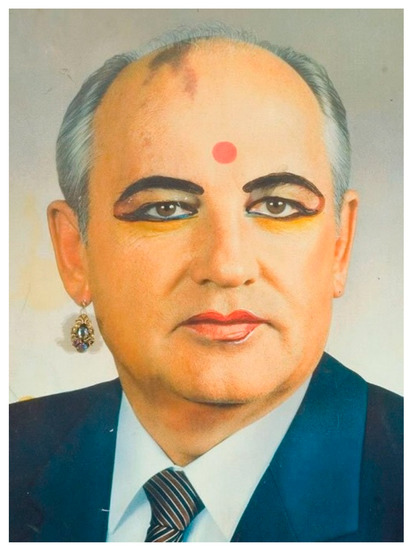

Vladislav Mamyshev’s biography was intentionally mythologized by himself, but thanks to memoirs of his friends (see Berezovskaia 2016) and an all-embracing web-portal dedicated to his life and work2, the main parameters of his adventurous life were restored. Born in 1969 into a family of the party apparatchik, Vladislav first attended a prestigious literary school, but was expelled from it for drawing caricatures of Politburo members.3 After this, he graduated from another school for artistically gifted students, which brought him, while still a very young men, into the circle of Leningrad experimental artists. In 1987, he was recruited to the army, from which he was sent to the mental institution for the impersonation of Marilyn Monroe and for transforming Gorbachev’s official photo into a now famous portrait of Gorbachev as an Indian woman. After his release from the institution, he returned to the Perestroika-driven Leningrad in 1989, where he soon gained tremendous popularity thanks to his colorful impersonation of celebrities (among which Monroe was his favorite), and multiple pranks, scandals, and hilarious trouble-making (frequently drug-inspired). He participated in multiple exhibitions, and the best galleries of St. Petersburg and, since the mid-1990s, Moscow hosted his solo shows. Among the collective exhibitions in which he participated was Caution: Religion! (2003) at the Sakharov Center, which became the target of an attack by a mob of religious obscurantists—and participation in this project signified a protest against growing political and cultural “neo-traditionalism”. In 2007 he received the Kanidnsky Prize, the most significant art award in Russia, for the remake of the classical Soviet comedy Volga-Volga, in which Mamyshev-Monroe played the female protagonist. Since this period, he spent more and more time outside of Russia. In 2010, Mamyshev-Monroe signed an appeal for the Russian opposition, “Putin must go”. His last production was a theater show, Polonium/Polonius (Polonii 2012), at the Moscow Polittheatre, which fused Hamlet motifs with references to the poisoning of Aleksandr Litvinenko with Polonium. This production, however, was interrupted by the sudden death of Mamyshev-Monroe. On 16 March 2013, he was found drowned in a hotel pool in the village of Seminyak in Bali. After his death, two major retrospectives of the artist took place in St. Petersburg (2014) and Moscow (2015). Several catalogues (Turkina and Mazin 2014; Selina et al. 2015) and a book of memoirs have also been published.

As an artist, Mamyshev-Monroe tirelessly tackled authoritative traditions in visual art, from the “parade portrait” of government officials to folklore stylizations harkening back to the early 20th century (Bilibin, Zvorykin). However, in all his encounters with an authoritative tradition, he created its comedic double, sometimes as a parody, sometimes a pastiche, but invariably, Mamyshev-Monroe employed tropes embedded in another long-standing tradition based upon the trope of the trickster.

The trickster is a traditional mythological and folkloric character, exemplified by such personages as Hermes, Prometheus, and Odysseus in Greek myths; Coyote and Rabbit in North American Indian mythology; Loki of the Norse pantheon; the Kitsune in Chinese and Japanese folklore; Ivan the fool and Thief in Russian wondertales; Hershele of Ostropol in Yiddish folklore; Hodja Nasreddin in Turkish; Till Eulenspiegel and Reineke the Fox in German, and so on. The folklore scholar William Hynes, characterizes the trickster as following:

Anomalous, a-nomos, without normativity, the trickster appears on the edge or just beyond existing borders, classifications and categories. […] [T]he trickster is cast as an ‘out’ person, and his activities are often outlawish, outlandish, outrageous, out-of-bounds, and out-of-order.No borders are sacrosanct, be they religious, cultural, linguistic, epistemological, or metaphysical. Breaking down division lines, the trickster characteristically moves swiftly and impulsively back and forth across all borders with virtual impunity. A visitor everywhere, especially to those places that are off limits, the trickster seems to dwell in no single place but to be in continual transit through all realms marginal and liminal.(Hynes 1993, pp. 33–46)

The folkloric trickster gave rise to a number of later sociocultural roles, such as the carnival clown, the fool, the jester, the impostor, the thief, the holy fool, the adventurer, the female trickster, the con artist, and others. Mediated by these sociocultural roles, the trickster tradition boils down to what can be defined as the trickster trope. The constants of the trickster trope include (1) ambivalence, understood as a special principle of deconstruction of binaries; destruction of borders between the sacred and profane, private and public, normative and illicit; (2) transgressivity—the violation of borders, norms and laws of the social order, and the injection of chaos and unpredictability; (3) liminality as the basis for radical freedom connected with nonbelonging to social hierarchies; and (4) hyperperformativity: the trickster replaces his/her “self” with numerous performative “masks” that fuse together the personal and stereotypical, private and public. The trickster’s freedom in this context manifests itself mainly in endless metamorphoses of the subject—liberation from the burden of a given and unchangeable identity serves here as a source of joy and playfulness—as well as the ability to involve others in a kind of participatory theater. The concretization of these constants in each specific case generates a specific set of variables, such as, for example, parodying authority and authorship, the aesthetic excess of tricks, the role of mediator, as well as many other characteristics, often directly reproducing the features of the mythological trickster.

Looking at various trickster roles across ages, it is impossible not to notice that they all retain the mythological semantics of chaos and freedom in their inseparable dialectic connection. This connection is most typically solidified by laughter. There are many tragic heroes who resemble tricksters (Hamlet, for example), but as a trickster they shine only in comic scenes. All of these categories are linked by “circular” cause-and-effect relationships. The liminality of the trickster justifies his or her transgressions, which in turn generate comic and ambivalent effects. In turn, it is the ambivalence of the trickster that motivates his or her liminality and is expressed in comic transgressions.

Looking at the cultural or political authority through the prism of the trickster act, Mamyshev-Monroe reinvented the modernist trickery of classical traditions exemplified by the Futurists’ and Oberiu performances (see Ioffe 2012), Meyerhold’s theater of the 1910–1920s, Eisenstein’s Mudrets (the 1920 production of Aleksandr Ostrovsky’s play Na vsiakogo mudretsa dovol’no prostoty), as well as comedic reinventions of classical plots and situations by the Satirikon writers, especially Aleksandr Averchenko and Teffi. Importantly, he inherited the modernist tradition of the ‘art of life’ (to use the title of Shamma Sahadat’s book about life-fashioning in Russian modernism [Shakhadat 2014]) and consistently inserted colorful theatricalized performances into the fabric of the everyday, as if prompted by Nikolai Evreinov’s theory of the “theatre for oneself”. According to Evreinov, the theatricalization of life is connected not only with the imitation of existing forms of art, but also with the methodical transgression of existing norms (behavioral, social, cultural, and moral), as well as with the excess, redundancy, and demonstrative overproduction of these forms.4 Certainly, one cannot disregard a possible influence of Marcel Duchamp—life theater, gender shifts and alternate identities (especially Rrose Selavy)—and Cindy Sherman’s series, especially “Film Stills” and “Clowns”; Mamyshev-Monroe could have been introduced to these and similar works by his many friends well-informed about the avant-garde Western art. Last but not least, Mamyshev-Monroe reinvented the repressed and underground tradition of drag performance and theatricalized queerness (see Healey 2017, pp. 95–104), which he used for the deconstruction of patriarchal models of power—symbolic and political alike. While doing this, Mamyshev-Monroe, intuitively, rather than deliberately, became a pioneer of the camp aesthetic in Russia, which remained unrecognized as such until recently (notably, the majority of existing critical writing on Mamyshev-Monroe mentions neither camp nor even queerness).

It is a small wonder that the word “trickster” frequently pops up in critical or memoirist writings about Mamyshev-Monroe. Both his cross-gender performances and everyday performative practices trigger the association between Mamyshev-Monroe and the mythological figure of a trickster. Thus, artist and critic Andrei Khlobystin speaks about the connection of nonbinary gender practices in general, and those in Mamyshev-Monroe’s art in particular, with the jester and carnival traditions (Khlobystin 1999). He also compares the artist with a court jester who mocks and appropriates the king’s power in a playful way: “Traditionally for a jester’s mission, Mamyshev was at the same time an alternative king, with the permissiveness he was entitled to. While making others laugh, he amused himself, acting as an expositor and healer of people’s passions” (Khlobystin 2018, p. 17). Olesia Turkin and Viktor Mazin argue that Mamyshev-Monroe’s anarchic freedom “leads not to the schizophrenic doubling of the world but to the role of a quasi-trickster—one who dons and tears off masks and speaks the “truth” about oneself and others” (Turkina and Mazin 2013) (I fail to understand the meaning of the prefix “quasi” before the trickster in this quote). Maria Kravtsova compares Mamyshev-Monroe with 18th-century adventure-seekers who combined roguery with a playful messianism.5 Both Andrei Khlobystin and Ekaterina Andreeva interpret Mamyshev-Monroe as the successor, albeit inconsistent, to the tradition of ancient Greek kynicism as, described by Sloterdijk and Foucault (see Sloterdijk 1987, pp. 156–68; Foucault 2011, pp. 157–306): “Although on the one hand he performs the function of a kynic, showing a different disregard for other people’s property and his own, on the other hand he is also a magpie thief, hungry for everything shiny and attractive”(Khlobystin 1999). A journalist and restaurant owner, Katia Bokuchava, compares Mamyshev-Monroe with “a little devil with an angelic face”, whom “you would pamper as a little child, until he, for example, would burn your apartment. But even after this, you won’t get rid of him” (Bokuchava n.d.). The carnival clown, the court jester, and the adventurer—these are all different historical and cultural manifestations of the trickster trope, combinations of those features that cement various modifications of the trickster myth.

Mamyshev-Monroe’s art is transgressive not only because of its open queerness that inevitably confronts Russia’s homophobic mainstream, but also due to his constant sacrilegious gestures and productions—he impersonated Hitler and Bin Laden, while making fun of national favorites, from Liubov’ Orlova, the famous star of Stalinist cinema, to the protagonist of a cult spy TV series from the 1970s, Otto von Stirlitz. Mamyshev-Monroe doesn’t spare any other norms either—moral, social, or cultural. Ekaterina Andreeva includes in her article an impressive list of his not always so innocent transgressions, among which the most famous is his arson of the apartment belonging to Boris Berezovsky’s daughter (see Andreeva 2014, p. 7). By the same token, the artist’s lifestyle until his last years was truly liminal. According to Andrei Khlobystin, “MVY [Mamyshev Vladislav Yurievich], is a natural, unadulterated adventurer, thief, nomad, living for years without a house or passport, the classic hero of a picaresque novel, constantly gets into risky situations and comes into contact with the criminal world in one way or another. MVY himself can, on occasion, be rude, aggressive and boorish a la Yesenin” (Khlobystin 1999).

Such a defining feature of the trickster as laughter is obviously characteristic of Mamyshev-Monroe’s art, as it is organically connected with different forms of carnivalistic inversions, mesalliances, and metamorphoses. Not only in post-Soviet but also in Russian art, Mamyshev’s series first pioneered camp as a queer sensibility in art, and with an accentuated sense of comedy. According to Susan Sontag, “the whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious […] One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious. […]” (Sontag 1966, p. 285). Among the defining features of camp, Sontag lists such contradictory features as extravagance and exaggeration, total aestheticism and theatricality; the indistinction of good and bad taste, dandyism, and strong ties with queer culture: “While it’s not true that Camp taste is homosexual taste, there no doubt a peculiar affinity and overlap”(ibid., p. 287)6.

Camp is ambivalent by default but, not satisfied with it, Mamyshev-Monroe deliberately accentuated the ambivalent as his artistic principle. His art is ambivalent, because, according to his own self-descriptions, he always enjoyed the moment of metamorphosis into the object of his impersonation. In his projects, the distinction between parody and admiring imitation of the object is frequently elusive. Mamyshev-Monroe semijokingly denoted his artistic method as “insinuationism”, which includes both life-creation and simulations of creative work that are so elaborate that they replace art itself: “Insinuationism is not simply ‘the art of lying,’ which Oscar Wilde admired so much, but the factual justification, the documentation of lies, the fiction, the creation of a logical plausible whole structure capable of misleading an opponent, or better yet, of convincing him of his worthiness (Chichikov)” (Mamyshev-Monro 1993a). Mamyshev-Monroe named Timur Novikov as the creator of this method, but also listed Hitler and Stalin among its forefathers, since they also succeeded in creation of various falsifications that effectively replaced reality: “Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, other tyrants who made their careers out of nothing belong to the guild of insinuators. […] The methods that helped them to cross borders up to the frontier of supreme power are very artistic, daring and even adventurous. Document fraud, falsifications of an ideological nature, equipping their own regimes with a special artistic line designed to imitate an inferior reality, and other “miracles” are truly miracles” (ibid.). This is certainly the trickster’s method of deception which absorbs both post-Soviet cynicism and postmodernist hyperreality of simulacra.

Finally, the trickster’s hyperperformativity secures his/her freedom to judge, perform, and mock within any given cultural milieu. As Bakhtin wrote about tricksters:

They are life’s maskers [litsedei zhizni]; their being coincides with their role, and outside this role they simply do not exist … [They have] the right not to understand, the right to confuse, to tease, to hyperbolize life; the right to parody others while talking, the right to not be taken literally, not to ‘be oneself’; the right to live a life in the chronotope of the entr’acte, the chronotope of theatrical space, the right to act as a comedy and to treat others as actors, the right to rip off the masks, the right to rage at others with a primeval (almost cultic) rage—and finally, the right to betray to the public a personal life, down to its most private and prudent little secrets.(Bakhtin 1982, pp. 159, 163)

This characteristic fully matches Mamyshev-Monroe’s automythology7. Mamyshev used the self-made term «вceвмeщaeмocть»—“allinclusivity” to define his self-expression through the nonstop impersonation of various characters, historical and fictional alike. Ekaterina Andreeva characterizes it as an echo of Dostoevsky’s “universal responsiveness” of the “Russian soul” (Andreeva 2014, p. 8). I see here another manifestation of camp—camp allows one to combine the trickster’s knack for the universal and exaggerated theatricalization (hyperperformativity) with a persistent sense of distancing detachment: “Camp proposes a comic vision of the world… If tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement, comedy is an experience of underinvolvement, of detachment” (Sontag 1966, p. 286). Camp motivates this detachment by pure aesthetic interest, releasing from moral responsibility, which corresponds the trickster’s ability to be “a-moral, rather than immoral” (Hyde 2010, p. 10).8

Most symptomatically, Mamyshev-Monroe manifested the trickster’s hyperperformativity through a nonbinary representation of the male/female dichotomy. In his 1994 article, Mamyshev wrote with sincere admiration about cross-dressing actors and travesties in Soviet film and TV—such as how Baba Yaga in filmic fairytales was routinely played by Georgii Milliar; Aleksandr Kaliagin played Charley’s aunt from Zdravstvuite, ia vasha tetia (Hello, I am Your Aunt, 1975); and the comedians Vadim Tonkov and Boris Vladimirov appeared at all official TV concerts in the makeup of elderly ladies, Veronika Mavrikievna and Avdot’ia Nikitichna (see Mamyshev-Monro 2014).9 However, in the majority of these examples, women’s features were used almost exclusively as comical and “low” (in comparison to the “normative” male characteristics). Post-Soviet drag queens such as Vera Serdiuchka or aggressively misogynistic performers in Roman Viktiuk’s theater not only preserve but aggravate this approach, which, in a new context, also paradoxically acquired homophobic overtones. Although Mamyshev-Monroe hardly knew any other traditions of drag-queen performances, his trickster ways allowed him to minimize the homophobia and misogyny embedded in Soviet drag, while emphasizing queerness and camp as a liminal zone of freedom.

The emphasis on the queer as the liminal zone of liberation from gender stereotypes, can be best illustrated by the work that has brought young Mamyshev international fame—his portrait of Gorbachev as an Indian woman (1989) (Figure 1). By transforming an official photo of the general secretary into a kitschy portrait with rosy cheeks, colored lips, heavy makeup on eyes and eyebrows, wearing an earring and necklace, and, most importantly, with a red Hindu bindi on the general secretary’s bald forehead, surprisingly, did not denigrate Gorbachev, as one would expect. This representation transformed him into an androgenous divinity, a naïve image of an otherworldly messenger of peace—rather than the new ruler of the Soviet empire. At the same time, there is an obvious irony in the ease with which a black and white official portrait can be transformed into an androgynous icon of the kitschy “Oriental beauty”. The positive message of this morphing was obvious and liberating for anyone—which explains why this image appeared on the covers of so many Western magazines in the early 1990s.

Figure 1.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. “M.S. Gorbachev” (1989). https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=47 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

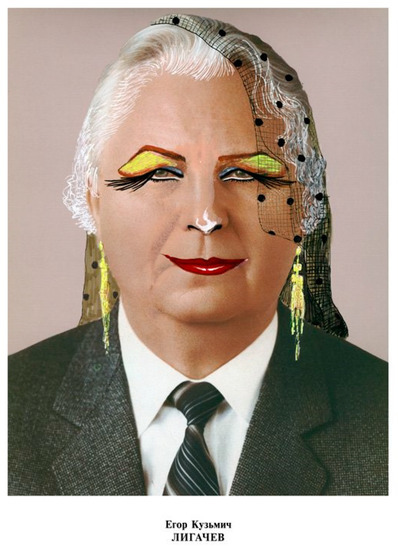

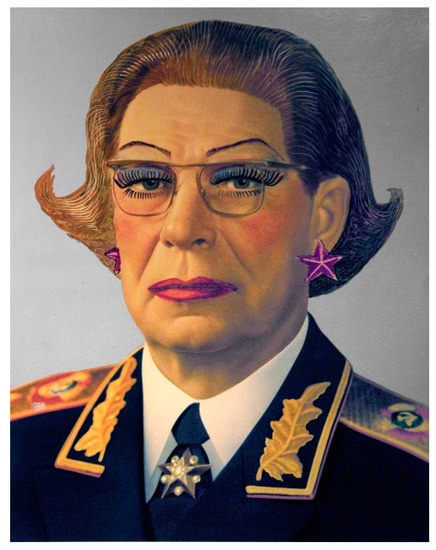

The Gorbachev portrait was followed by Mamyshev’s long-going series “The Politburo” (1990, 1995, 2002, 2011), in which grotesquely exaggerated, almost clownish make-up turned Politburo members into funny and unappealing (unlike Gorbachev) drag queens. Mamyshev was not employing homophobic tropes as a satirical device here. By dressing Soviet functionaries in drag, he performs the transfiguration of scary death masks into carnivalesque figures comparable to Cindy Sherman’s clowns (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The artist in one of interviews recalled that his mother, the party apparatchik, when he was a child, taught him to recognize all the Politburo members by names by playing with him a lotto-like game with their little portraits cut-off from a newspaper. The morphing of these deflated icons of power, thus, defamiliarizes the familiar, makes it strange—as per Shklovsky—and hence, valuable again, but this time, aesthetically rather than politically. After Mamyshev’s “editing”, the new versions of the Politburo’s “official” portraits appear to be filled with life and color, although the grotesque tension between their former (deathlike) and present (carnivalesque) representations remains tangible.

Figure 2.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Politburo” (1995) E.K. Ligachev. https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=4#work-series-4-5 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 3.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Politburo” (2011). D.F Ustinov. https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=16#work-series-16-2 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Symptomatically, Mamyshev’s “morphing” (Ekaterina Andreeva’s term [Andreeva 2014, p. 8])—an impersonation of different historical characters—generates an openly postmodernist effect of the “perpetual present” (Fredric Jameson) that suggests a virtual elimination of history and historical perspective. History appears as a costume, and not even a historical one, but one which a contemporary audience would recognize as “historical”. In other words, such a transformation reproduces a kitschy image of “historical accuracy”, a simulacrum in a chain of simulacra. However, what distinguishes Mamyshev-Monroe, say, from other “quasi-historical” portraits of pop celebrities10, is the detectable sense of irony towards his impersonations—an unstable distance from the created image that is best seen in such series as the “Life of Remarkable Monroes” (1995) (Figure 4 and Figure 5). Despite “glamorous” poses and elaborate makeup transforming the artist into Peter the Great, Marylyn Monroe, Napoleon, Joan of Arc, Sherlock Holmes, Queen Elizabeth, Lenin, Hitler, and Jesus Christ, the series in its entirety produces an ironic effect. Mamyshev impersonated various symbols of power—political, symbolic, or aesthetic alike; at the same time, he tried to “de-ideologize” these icons. In the interview with Tomas Glanc he said: “…the main object of study for me are the geometric forms of these faces, a kind of portrait mandalas, i.e., absolutely symbolic values, which have long ago and automatically fixed in the minds of millions of those or other qualities”.11 However, taken together, these images are truly grotesque—Jesus Christ and Hitler are equal in this series, because they are equally “famous”. This is how an ordinary Russian person imagines power and success; the absence of any ethical values at this mental map produces a staggering effect.

Figure 4.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Life of Remarkable Monroes” (1995). https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=1#work-series-1-9 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 5.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Life of Remarkable Monroes” (1995). https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=1#work-series-1-1 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

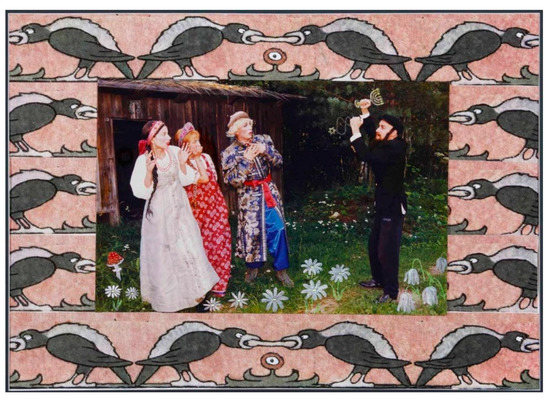

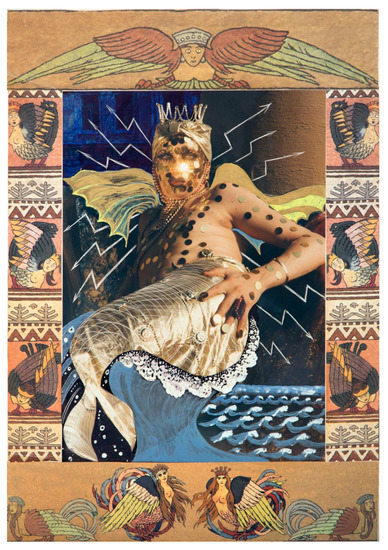

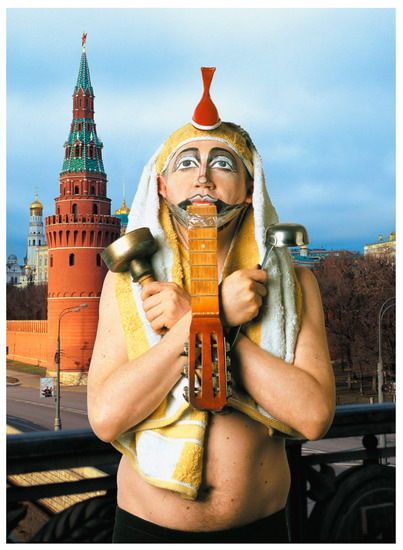

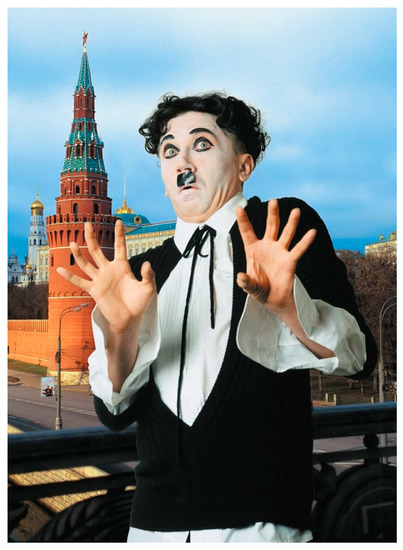

In the later series, such as “The Russian Questions” (1997), “Tales of the Time Lost” (with Sergei Borisov, 2001), “Star3” (CтapЗ, 2005), and “Russia that We’ve Lost” (2007), Mamyshev impersonations were increasingly satirical. In “The Russian Questions” he created a contrast between stylized frames borrowed from Ivan Bilibin’s famous series of illustrations for Russian fairytales and scenes performed by Mamyshev and his friends (Timur Novikov, Georgii Gurianov, Elizaveta Berezovskaya, Irena Kuksenaite, and others). Using costumes from Soviet films such as the legendary Amphibian Man (1961), Mamyshev created grotesque “screenshots” from nonexisting Soviet cinematic fairytales, exemplified by Aleksandr Ptushko and Aleksandr Rou. The artist imitates their visual stylistics but applies it to subjects unimaginable in Soviet films—such as, for example, a confrontation between the Russian prince with a Jew or the representation of a sexually alluring mermaid (Figure 6 and Figure 7). In “Star3”, he depicted various world celebrities against the same background of the Moscow Kremlin, but while doing this he emphasized the unhappy or plain scared expressions of these “foreigners” in Moscow. DIY improvised media was used for their images—duct tape for Chaplin’s and Hitler’s mustaches, a garbage bag for Bin Ladin’s beard, a plastic shopping bag for Marilyn Monroe’s “cocktail dress”, and a ladle and plunger for the Egyptian pharaoh’s symbols of power (Figure 8 and Figure 9)—conveying the simulative, fake nature of the created characters (despite their uncanny similarity to originals), and by this means, revealing the superficiality and hyperreality of westernization in post-Soviet Russia.

Figure 6.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “The Russian Questions” (1997), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=6#work-series-6-3 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 7.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “The Russian Questions” (1997), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=6#work-series-6-5 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 8.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Star3” (2005), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=3#work-series-3-3 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 9.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Star3” (2005), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=3#work-series-3-12 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

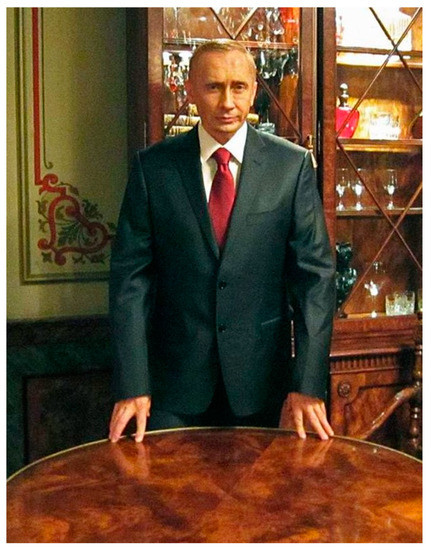

Nevertheless, the distance between the artist and the impersonated character, even one depicted satirically, remains unstable. Illuminatingly, when commenting on his impersonations of Putin (Figure 10) or Valentina Mativenko (at the moment, the governor of St. Petersburg) (Figure 11), Mamyshev emphasized the instant artistic metamorphosis that he experienced and that allowed him to “feel” his object from the “inside”:

First, I copy a character’s face from a photograph, change my clothes, stand in front of the camera… And then there’s a click. And for a few seconds the essence enters my body. Only the first photos can capture this penetration. Then I practice my acting skills. But only those seconds are magical, I myself do not fully understand how it happens.(Mamyshev-Monro 2013a)

Figure 10.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Remember about gas” (Pomiatai pro gaz, 2011), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=42 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 11.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Valentina Matvienko” (2005), https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=30#work-series-30-2 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

When describing how he photographed as Putin for the series “Remember about gas” (2011), Mamyshev went as far as conveying the “inner image” of his model:

If you are making a precise drawing, you do not allow any deviations from the original, then at some point there is a strange chemistry of some kind. It literally lasts for a few seconds-and it’s only at that point that you have to take the picture-that someone else’s soul comes into you. For example, the first time I dressed up as Putin, I had the feeling that I had become some kind of colossal totemic maggot that was about to burst from the shit I ate. At the same time, I’m not a villain, but a forest ranger, and I have to gobble up our country-the dead, great Russian empire, the Soviet Union-as quickly as possible so that a new life can begin.(Mamyshev-Monro 2013b)12

These self-descriptions by Mamyshev are surprisingly reminiscent of those made by Dmitrii Prigov, a leading representative of Moscow Conceptualism. Prigov in similar terms described his poetic technique of speaking through voices of other, imaginary or collective, subjects13, while Mamyshev translated it into the visual. This translation suggests a certain dialectics of “recognition” and “estrangement”, which becomes especially challenging in the preferred medium of Mamyshev—modified photographs. Aleksandr Skidan emphasized in Prigov’s discursive “acting” elements comparable with Brechtian theater, in which

the actor does not reincarnate in the character of the play, but shows it, taking a critical distance in relation to it, so DAP [Dmitrii Aleksandrovich Prigov] in his texts constantly “steps out of the role,” exposing the artificiality, the madeness of the textual construction, along with the construction (“personhood”) of the lyrical subject. […] This self-reflexive, analytical technique becomes in Brecht and Prigov an instrument for the crystallization of the dominant ideology to the degree that it speaks through conventional artistic forms and discourses. Needless to say, for Brecht, the instance of power dispersed in “aesthetics” was bourgeois ideology, while for Prigov it was mostly communist (utopian, messianic) ideology.(Skidan 2010, p. 126)

Unlike Prigov, Mamyshev’s series highlight the artist’s “sincere” fusion with his models, but nevertheless, they also always contain elements of estrangement and irony that shape a critical distance between the artist and his character and prevent a full metamorphosis à la Stanislavsky’s “method”.

But what is the “dominant ideology” that Mamyshev deconstructs? Most likely, this is an ideology of the glamour that concentrates the pathos and repression of the “society of the spectacle”—both in its capitalist (post-Soviet) and quasisocialist (Soviet) versions. In both cases, the visual imagery promises an escape into an alternative—bright, beautiful, fantastic, and uplifting. According to Guy Debord,

the spectacle […] obliterates the boundaries between self and world by crushing the self […] also obliterates the boundaries between true and false by repressing all directly lived truth beneath the real presence of falsehood maintained by the organization of appearances. Individuals who passively accept their subjection to an alien everyday reality are thus driven toward a madness that reacts to that fate by resorting to illusory magical techniques. […] As Gabel puts it in describing a quite different level of pathology, ‘the abnormal need for representation here makes up for a torturing feeling of being on the edge of existence’.(Debord 2014)

In his art, Mamyshev highlights “illusory magical techniques” operating in the society of the spectacle and displays the “crushing of the self” as well as the obliteration of “the boundaries between true and false” in such a demonstrative and even naïve way that the entire theatricality of the society of the spectacle is laid bare, thus revealing a “a torturing feeling of being on the edge of existence”. In this respect, Mamyshev-Monroe’s art is not at all nostalgic, rather it falls into the category of postmodernist performances that, according to Marvin Carlson, combine “mimicry” and “counter-mimicry” (see Carlson 2017, pp. 192–94). Camp as a form of trickery (and trickery as an extension of camp) serves as a glue connecting the opposites and allowing Mamyshev to mock the societal spectacle by the spectacular means.

From this perspective it is not surprising that Mamyshev-Monroe’s attitude to socialist realism was more complex than either a Sots-Art tradition, exemplified by Moscow conceptualists, or the “New Artists’” admiration of socialist realism as a model for their “neo-academism”. On the one hand, he wrote an article on the “Impressive Greatness of Soviet Totalitarian Aesthetics” (see Mamyshev-Monro 1993b), in which he praised Soviet heroic mythology as being not only comparable with the ancient Greek myths but also, similar to them, serve as a source of aesthetically perfect works (he failed to provide concrete examples, of course):

… Soviet heroic mythology is a holistic aesthetic complex united by an impressive pathos of reproduction, a consistent evolution of once chosen artistic style, rich in discoveries, affecting the human psyche in a peculiar but qualitative way. […] An inquisitive mind can take a tremendous aesthetic pleasure comparable to the rapture of a traveler at the recollection of a dizzyingly dangerous expedition.A series of amazing, sometimes incredible feats of Soviet heroes captures the highest degree of self-denial, incomprehensible, but iron logic of events, the vitality of diverse, but united in their heroism of characters, purity and full openness of feelings, the desire for spiritual self-improvement and the true immortality of heroes, finally, the atmosphere of mass heroism, meticulously created by the style of narration …(Mamyshev-Monro 1993b)

On the other hand, he imagined Liubov Orlova as the antipode of his alter ego, Marylyn Monroe. If Mamyshev performed Marylyn as a personalized sentimentality and sensuality, Liubov (literally: Love) Orlova, in his interpretation, on the contrary, embodied a deathlike “mask of happiness” and the aggressive willpower: “The mask of happiness […] crowned the hierarchy of the non-existing fairy-tale like paradise depicted in all her films. […] Orlova herself would better match a non-existent first name ‘Will’ with the last name ‘Steel’ that reflect her professional and personal qualities most faithfully” (Mamyshev-Monro 2015, p. 89). In the later interview he added even angrier definitions of Orlova while comparing her with the snow queen who radiated icy-cold and absolutely asexual power and thus enhanced the regime’s cynical dominance (see Mamyshev-Monro 1993b).

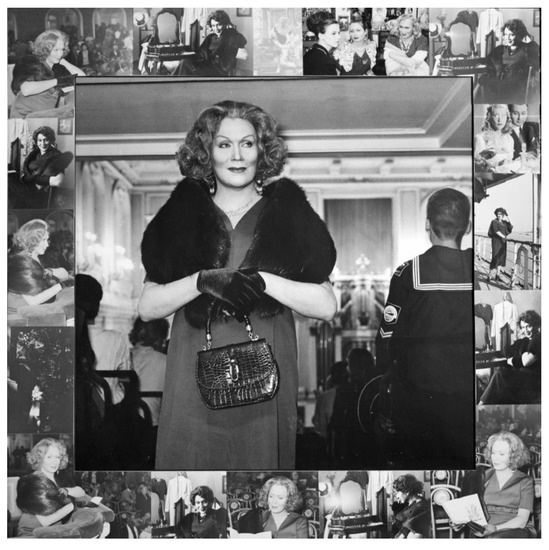

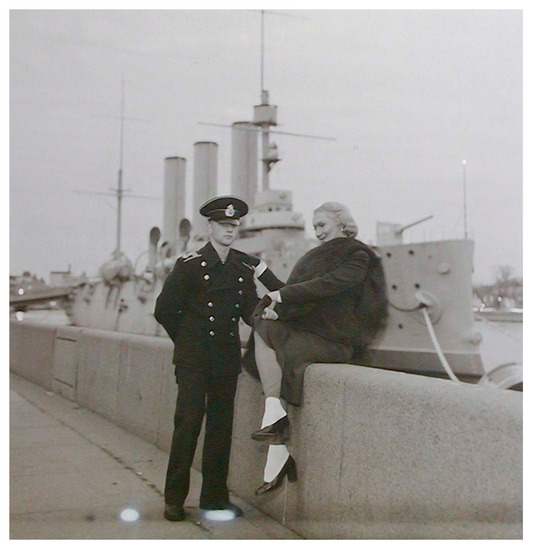

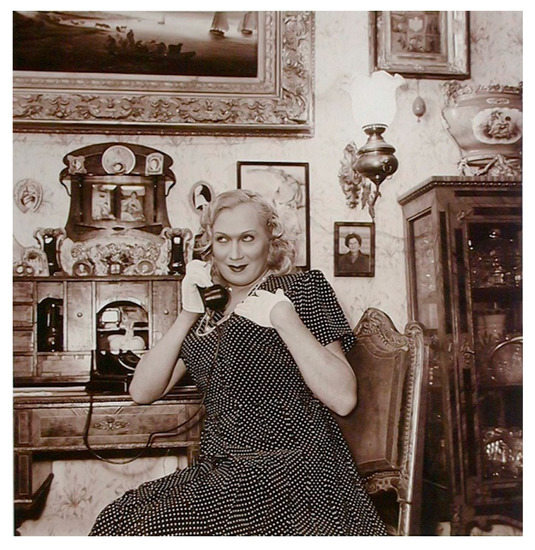

Orlova appears in several of Mamyshev’s projects—most notably in the series of photographs, Happy Love (Schastlivaia liubov’, 2000), and in Pavel Labazov and Andrei Sil’verstov’s remake of Grigorii Aleksandrov’s Socialist Realist comedy, Volga-Volga (1937), with Mamyshev playing Orlova/Strelka (2006, the project won the Kandinsky prize). The first series displays Orlova’s choreographed poses, sophisticated costumes, and interiors oversaturated with symbols of wealth and abundance—old paintings, porcelain, crystal glasses, and carafes. Most likely, Mamyshev wanted to emphasize the hypocrisy of Soviet culture that propagated the revolution and egalitarianism while rewarding most active promoters of these values with the “bourgeois” lifestyle and comfort. (Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14). However, the result appears to be more ambivalent. Twice, Orlova was photographed against the backgrounds of ships—a revolutionary cruiser, Avrora, and the legendary icebreaker, Krasin, for more than a year had been stuck in the polar ice. In both photos, Orlova’s appearance contrasts these symbols of the epoch—her outfit with white socks and furs has nothing to do with the revolution and the heroic hardships. She appears as a timeless figure, free from the Soviet world and using it only as flashy background for her beauty. In other words, Orlova also manifests a fairytale-like freedom—choreographed, manufactured, and subsidized by lies and betrayals—but nevertheless, impressive and alluring.

Figure 12.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Happy Love (Liubov’ Orlova)” (2000); https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=15#work-series-15-9 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 13.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Happy Love (Liubov’ Orlova)” (2000); https://vmmf.org/exhibition/view?id=80 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Figure 14.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe. From the series “Happy Love (Liubov’ Orlova)” (2000); https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=15#work-series-15-3 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

A much less attractive Orlova appears in the remake of Volga-Volga. Mamyshev’s face with heavy make-up was pasted over the “real” Orlova in scenes from Alexandrov’s film. (Figure 15) In Volga-Volga, the real Orlova plays one of the few female tricksters in Soviet culture, who, by her own hyperperformativity, confronts the rigid bureaucrat Byvalov. Mamyshev-Monroe’s performance transforms Strelka into an alien monster with a motionless face and frozen smile. Nothing is changed in the dialogue, but it is Mamyshev who says Strelka’s text, with the tone of his voice rapidly jumping from the artificially girlish to the hypermasculine. All songs were also performed by Mamyshev, who intentionally distorts the music terribly.

Figure 15.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe as Strelka in Volga-Volga (2006, a remake of the 1937 film dir. by Pavel Labazov and Andrei Sil’vestrov).

The meaning of this distortion becomes clear only in correlation with the photographs from the series Happy Love—the monster from Volga-Volga secures the comfort of the elegant lady from the photo series; furthermore, being this monster is the price for Orlova’s freedom and beauty, or its ugly, Hyde-like, shadow. This is the trickery that Mamyshev-Monroe apparently rejects—his idea of hyperperformativity suggests that each of his fictional personae manifests freedom, and each of them is beautiful in its own way.

Café Elefant, Mamyshev-Monroe’s “remake” of the famous scene from the cult TV series, 17 Moments of Spring (1973, dir. Tatiana Lioznova), depicting Otto von Stirlitz’s—played by Viacheslav Tikhonov—silent and contactless “date” with his wife, is probably the most spectacular case of Mamyshev’s camp targeting the Soviet material. In this two-minute-long silent video14, produced for the St. Petersburg New Pirate TV, Mamyshev performs both Stirlitz and his wife and thus rewrites one of the best examples of Soviet patriotic sentimentalism, turning it into a cluster of contradicting narratives. He reproduced the iconic scene frame by frame, which prompted Ekaterina Andreeva to argue that the artist reveals the personal drama of filmic characters: “While remaining very similar to the original and funny at the same time, this scene openly becomes what it is only implied in the film—a representation of mourning for a life lost, exchanged for a heroic feat, an irretrievable life and a tragic love” (Andreeva 2021, p. 78). Mamyshev even managed to “insert” his performance into the opening ceremony of the pompous 2006 exhibition “Russia!” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, attended by Putin, among others. As Ekaterina Andreeva notes, there are no traces of this video in the exhibition’s program, which suggests that it was a last-minute addition—or rather, a trickster’s contraband (see Andreeva 2014, p. 15).

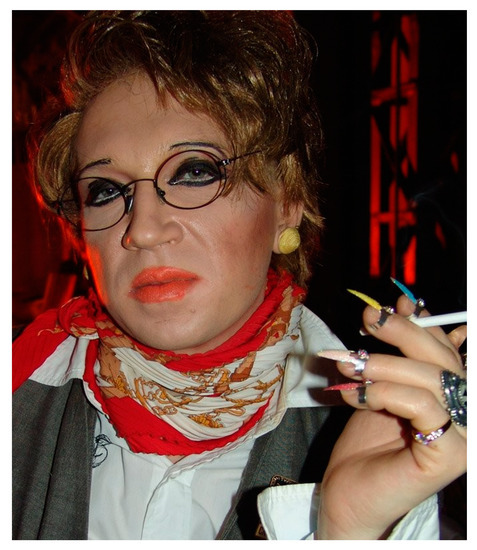

Surprisingly, when writing about Café Elefant, critics fail to notice clear references to the visual discourse of camp and drag culture. Among these signs, one may notice heavy makeup on the face of Stirlitz coupled with Mamyshev’s simultaneous appearance in drag as Stirlitz-Isaev’s wife. No less indicative is the exaggeratedly melodramatic facial and body language of both characters (clearly opposed to subtlety of their originals’ emotional expressivity). The café suddenly turns into a cabaret where the artist in drag reigns upon the stage, performing all the parts by themself.

While recreating a scene of the secret meeting of the Soviet undercover spy with his wife, left behind in the USSR, Mamyshev, on the one hand, reveals the repressed sexuality of the original, and on the other, emphasizes the striking contrast between Stirlitz and his wife. He depicts Stirlitz as a decadent dandy, with exaggeratedly queered expressions and gestures (Figure 16). His wife, on the contrary, appears in drag as an ordinary, mundane lady with no distinctive features except for an awful hairdo and a koshelka in her hands. (Figure 17).

Figure 16.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe as Stirlitz in Café Elefant.

Figure 17.

Vlad Mamyshev-Monroe as Stirlitz’swife in Café Elefant.

The ambiguity of the wife’s image suggests at least two interpretations of the entire scene. One interpretation implies the hidden passion of two queer men, separated by duty and secrecy. If we look at Café Elefant as a secret meeting of estranged queer lovers, the somber scene becomes a melodrama of forbidden passion, queering the patriotic narrative. Another, interpretation offers an alternative reading for the entirety of Stirlitz’s saga, transforming the spy thriller into the story of a queer man, who can be himself only when he is away from his stern motherland. In this interpretation, Stirlitz’s wife appears as the personification of the motherland (cf. Blok’s famous line “жeнa мoя дo бoли”), who patiently waits for him to return and whom he would rather avoid for as long as he possibly can. In both readings, however, Mamyshev’s performance critiques the heteronormative optics that fail to notice the painfully obvious queer overtones of this scene and the entire figure of Stirlitz and his secret freedom.

The coexistence of several parallel interpretations, especially with sexual and queer overtones, is the epitome of camp. According to Susan Sontag: “the Camp sensibility of one that is alive to a double sense in which some things can be taken […] when a person or a thing is ‘a camp’, a duplicity is involved” (Sontag 1966, p. 286). The coexistence of conflicting intertexts leads here to the coexistence of mutually exclusive interpretations that, when taken together, produce at least two conceptual effects. First, they clearly desacralize or profane the sacred imagery associated with the Great Patriotic War and its mythology. The desacralization is performed in a recognizably carnivalesque manner, wherein tragic heroes are replaced by clowns appearing in two roles simultaneously; a display of forbidden sexuality with the spectacle of heroic self-restraint and self-sacrifice for the sake of the motherland; wherein the model of heteronormativity is transformed into a celebration of queer play. Secondly, this performance, with its open and emphatic theatricality, mocks the Soviet society of the spectacle, obviating the constructed and mutable character of cultural icons; showing how slight shifts in visual representation can radically rewrite—and even unwrite—the seemingly unshakeable “message” of the idiomatic spectacle.

Mamyshev-Monroe is not the first campy trickster in the world, but he is the first Russian artist who has turned camp into the foundation for his artistic metaposition. Camp is responsible for the laughter that connects such early works as the Gorbachev portrait with such mature projects as Café Elefant or the Orlova series. His laughter signifies liberation from delimiting gender norms and restraints through an outburst of queer freedom. Mamyshev’s performances and his trickery display the inseparable fusion of camp, queerness, and freedom.

Despite his declarative lack of any political convictions and apparent cynicism, Mamyshev did not try to conform to the changing political climate in Putin’s Russia. Beginning in 2007, he practically emigrated from the country. According to Peter Pomerantsev, Mamyshev’s death in 2013 was also associated—if only indirectly—with an unwillingness to conform to a new authoritarianism: “Vladik himself was dead. He was found floating in a pool in Bali. Death by heart attack. Right at the end an oligarch acquaintance had made him an offer to come over to the Kremlin side and star in a series of paintings in which he would dress up and appear in a photo shoot that portrayed the new protest leaders sodomizing. Vladik had refused” (Pomerantsev 2014, p. 278). In April 2013, the critic Artemi Troitsky published Mamyshev’s emails addressed to him, which corroborated Pomerantsev’s version. According to these documents, Sergei Bugaev (Afrika), a former member of the New Artists group and the star of Sergei Soloviev’s cult movie, Assa (1987), brought the artist to Cambodia, where a notorious businessman Sergei Polonsky, on behalf of Vladislav Surkov (at the moment, Putin’s closest aide and ideolog), pressed Mamyshev-Monroe to produce a series of pornographic photos in his idiosyncratic style depicting the leaders of the anti-Putin opposition (see Troitsky 2013). Appalled by this offer, Mamyshev escaped from Cambodia back to Bali, where he died. In his own words (from a message addressed to Troitsky),”I fu…d off from Sihanoukville, where Africa and Polonsky invited me under the pretext of filming a movie. But it was a trick, Afrika began to push me into making the propaganda for Putin, I fled in horror, the boy went crazy […] I am a weak person, half Marilyn Monroe, you could say, so it’s easier for me to f.ck off, like I went back into drugs or something like that. I’m afraid to quarrel openly with devils” (ibid.).

Apparently, the trickster’s transgressively has its limits—it proves to be incompatible with the authoritarian regime’s attempts to instrumentalize it for its own repressive purposes. This principle, however, does not apply to all cultural tricksters of the 2000s–2010s—many of them gladly allowed their transgressions to be used by the transgressive regime who paid generously for their service (e.g., a transformation of the rock musician Sergei Shnurov, famous for his music videos about hapless tricksters, into an enthusiastic supporter of the regime after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022). Why was Mamyshev-Monroe so appalled by this perspective? He obviously could not cope with the aggression and potential violence that he clearly detected in his commissioners; in his email to Troitsky he wrote about Afrika: “He is fiercely motivated, promising that all those who now opposed it [Putin’s regime], will either be killed or maimed, or deprived of all means of subsistence. He was foaming at the mouth about all this to me. It made me sick”(ibid.).

But, perhaps, camp also granted Mamyshev-Monroe immunity to the attempt to “coopt” him for the repressive needs. “Camp, writes Sontag, is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of ‘style’ over ’content’, ‘aesthetic’ over ‘morality’, of irony over ‘tragedy’”. (p. 10). Possibly, the “commissars”’ proposal was, first and foremost, aesthetically abject for the artist, which suggests that an aesthetic taste for a campy trickster acquires ethical and political meanings. In turn, one may conclude that the trickster’s reputation of being necessarily “a-moral” needs to be adjusted—at least, in the case of Mamyshev-Monroe.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Indicated in the pictures credits.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | As noted by Julie Cassiday, “Despite their close collaboration during the New Academy’s formative years, Mamyshev-Monroe and Novikov gradually parted ways […] Despite his advocacy of the New Academy’s mission, Mamyshev-Monroe fit poorly into the ‘new seriousness,’ whose reactionary aesthetic platform and politics absorbed Novikov’s energies in the final years of his life. In the end, Mamyshev-Monroe’s cross-dressing turned away from both Neoacademism and New Russian Classicism, since his reincarnations of both men and women embodied not merely the beautiful, but also the tawdry, the tasteless, and even the unabashedly ugly” (Cassiday 2019, p. 222). |

| 2 | See https://vmmf.org (accessed on 8 September 2022). Created by the Mamyshev-Monroe Foundation. |

| 3 | See Mamyshev’s bio on https://artguide.com/people/2929 (accessed on 8 September 2022). |

| 4 | On Evereinov’ s theories see (Maksimov 2002; Chubarov 2006; Smith 2018). |

| 5 | “… the biography of Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe is as if deliberately built according to all the canons of the picaresque novel, and in the fate of the artist one can trace many parallels with the fates of the most celebrated adventurers of the XVIII century: Giacomo Casanova, Stepan Zannovich, Alessandro Cagliostro, and especially the chevalier d’Eon, the brave dragoon captain in a woman’s dress, who carried out diplomatic missions for King Louis XV of France and the Russian Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. And in this context, it is not at all surprising that on a par with Hitler’s mask and Marilyn Monroe’s white dress, one of Mamyshev’s guises is that of an 18th-century aristocrat” (Kravtsova 2014). |

| 6 | Julie A. Cassiday defines Mamyshev-Monroe’s performances as “a clearly gender-inflected stiob”, basing her approach on Alexey Yurchak’s concept of stiob (Cassiday 2019, p. 225). However, she uses only one part of Yurchak’s definition—overidentification, while omitting the other—decontextualization. Indeed, unlike Yurchak’s examples of stiob (a birthday card for a friend written in the language of Politburo documents), Mamyshev-Monroe’s impersonations do not decontextualize historical figures, or at least, they are decontextualized no more than any celebrity’s portrait displayed in a gallery. Although there is a certain overlap between concepts of stiob and camp, camp, in my opinion, offers a broader and, at the same time, more specific approach to Mamyshev’s art. |

| 7 | Julie Cassiday cites a vast number of evidences by Mamyshev’s friends and colleagues who testify that the artist was always in character and constantly performing. See (Cassiday 2019, p. 227). |

| 8 | Cf. a remark of the photographer Valerii Katsuba about Mamyshev-Monroe: “Vladislav is doomed to be forgiven. He is constantly balancing between being loved and hated by everyone”. («Bлaдиcлaв вceпpoщaeм. Oн пocтoяннo бaлaнcиpyeт нa гpaни вceoбщeгo любимцa и нeлюбимцa») (Katsuba 2013). |

| 9 | On the history of Soviet transvestism see (Khoroshilova 2012; Cassiday 2018; Cassiday 2019, pp. 229–31; Dviniatina 2018). |

| 10 | For example, Ekaterina Rozhdestvenskaya (a daughter of a renowned Soviet poet) became famous by her photo-portraits of post-Soviet celebrities in “historical” costumes and settings. |

| 11 | Quoted from: https://vmmf.org/series/view?id=1 (accessed on 8 September 2022). |

| 12 | This “insight” translates into an accurate political forecast. When an interviewer asks the artist if he thinks that Putin will indeed “devour us all”, Mamyshev responds: “Yes, very soon. You know, in Bali, where I lived for a long time, there are all kinds of parasites. Some kind of wood bugs, termites. And then there’s this luxurious teak cabinet in the house, Dutch craftsman style. You use it every day, you have clothes hanging in it, but at some point, you touch it, and it crumbles. It’s just eaten up. It’s the same with our country” (ibid.). |

| 13 | For example, in a conversation with Mikhail Epstein, Prigov describes the effect of metamorphing as following:

|

| 14 | Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TfWmlY3hx58&t=164s (accessed on 8 September 2022). |

References

- Andreeva, Ekaterina. 2014. Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro: Genii peremen. Moscow: Ad Marginem. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, Ekaterina. 2021. Sovetskoe v proizvedeniiakh Vladislava Mamysheva-Monro. Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta. Iskusstvovedenie 11: 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, Ekaterina, and Nelli Podgorskaia, eds. 2012. Novye khudozhniki = The New Artists. Moscow: Moskovskiĭ muzeĭ sovremennogo iskusstva. Maier. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1982. Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Edited and Translated by Michael Holquist, and Caryl Emerson. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berezovskaia, Elizaveta, ed. 2016. Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro v vospominaniiakh sovremennikov. Moscow: Artgid. [Google Scholar]

- Bokuchava, Katya. n.d. “Vladik Monro: Instruktsiia dlia Obshcheniia”. Available online: http://kolonna.mitin.com/dantes/dj02/bokuchava.shtml (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Carlson, Marvin. 2017. Performance: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cassiday, Julie A. 2019. Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, Frog-Princess of Neoacademism. The Russian Review 78: 221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiday, Julie A. 2018. Glamazons en travesti: Drag Queens in Putin’s Russia. In Russian Performances: Word, Object, Action. Edited by Julie A. Buckler, Julie A. Cassiday and Boris Wolfson. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 272–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chubarov, Igor. 2006. ’Teatralizatsiia zhizni’ kak strategiia politizatsii iskusstva: Povtornoe vziatie Zimnego Dvortsa pod rukovodstvom N.N.Evreinova (1920 god). In Sovetskaia vlast’ i media. Edited by Hans Gunther and Sabina Haensgen. St. Petersburg: Akademicheskii proekt, pp. 281–95. [Google Scholar]

- Debord, Guy. 2014. The Society of Spectacle. Translated and Annotated by Ken Knabb. The Bureau of Public Secrets: Available online: https://files.libcom.org/files/The%20Society%20of%20the%20Spectacle%20Annotated%20Edition.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Dviniatina, Mila. 2018. Travestiia v sovetskom kino. Teoriia Mody 41: 1. Available online: https://www.nlobooks.ru/magazines/teoriya_mody/47/article/19331/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Epshtein, M. N., and D. A. Prigov. 2010. Popytka ne byt’ identifitsirovannym. In Nekanonicheskii klassik: D.A. Prigov (1940–2007). Edited by Evgeny Dobrenko, Ilya Kukulin, Mark Lipovetsky and Maria Maiofis. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, pp. 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 2011. The Courage of the Truth (The Government of Self and Others II), Lectures at the College De France, 1983–1984. Edited by Frédéric Gros. Translated by Graham Burchell. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Dan. 2017. Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, Lewis. 2010. Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Hynes, William J., ed. 1993. Mapping Mythic Tricksters. In Mythical Trickster Figures: Contours, Contexts, and Criticisms. Tuscaloosa and London: Univ. of Alabama Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2012. The Futurist Pragmatics of Life-Creation and the Performative Ideology of the Avant-Garde. Looking at Aleksej Kručenych Through the Prism of Life-Writing. Russian Literature 71: 371–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuba, Valerii. 2013. “O Vladislave Mamysheve-Monro”. Available online: http://femme-terrible.com/dantes/number-two/o-vladislave-mamysheve-monro/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Khlobystin, Andrei. 1999. Merilin Makhno. Dantes 2. Available online: http://femme-terrible.com/dantes/number-two/merlin-maxno/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Khlobystin, Andrei. 2018. Shizorevoliutsiia: Ocherki peterburgskoi kul’tury vtoroi poloviny XX veka. St. Petersburg: Borey Art Center. [Google Scholar]

- Khoroshilova, Ol’ga. 2012. Russkie travesti v istorii, kul’ture i povsednevnosti. Moscow: MIF. [Google Scholar]

- Kravtsova, Maria. 2014. Monro v zerkale avantiurizma. Art Gid 73, March 13. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimov, V. 2002. Filosofiia teatra Nikolaia Evreinova. In Demon teatral’nosti. Edited and with a commentary by N. N. Evreinov, A. Iu. Zubkov and V. I. Maksimov. Moscow and St. Petersburg: Letnii sad. [Google Scholar]

- Mamyshev-Monro. 1993a. Insinutsionizm. Khudozhestvennyi zhurnal 3. Available online: https://vmmf.org/extlink/files/14/1413_643bae1241bc94a863ca367987ebc5902d8cb7e6.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Mamyshev-Monro. 1993b. Vpechatliaiushchee velichie sovetskoi estetiki totalitarizma. Kabinet 3: 56–59. Available online: http://kolonna.mitin.com/dantes/dj02/monro9.shtml (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Mamyshev-Monro. 2013a. Interview with Maria Moskvicheva. Moskovskii komsomolets, March 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mamyshev-Monro. 2013b. Interview with Natalia Kostrova. Afisha-Gorod. March 11. Available online: https://daily.afisha.ru/archive/gorod/archive/monroe-polonius/Curiously (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Mamyshev-Monro. 2014. Transvestizm v traditsii russkogo messianstva. Available online: https://artguide.com/posts/674 (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Mamyshev-Monro. 2015. Liubov’ ne umiraet. K vystavke v Galeree Marata Gel’mana. In Katalog vystavki v Moskovskom muzee sovremennogo iskusstva. Moscow: Moskovskii muzei sovremennogo iskusstva. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantsev, Peter. 2014. Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia. New York: PublicAffairs. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhadat, Shamma. 2014. Iskusstvo zhizni: Zhizn’ kak predmet esteticheskogo otnosheniia v russkoi kul’ture XVI–XX vekov. Moscow: NLO. [Google Scholar]

- Sloterdijk, Peter. 1987. Critique of Cynical Reason. Translated by Michael Eldred. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Alexandra. 2018. The Transgressive Capacity of the Comic: A Merry Death as an Embodiment of Nikolai Evreinov’s Vision of Theatricality. The Modern Language Review 113: 583–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skidan, Aleksandr. 2010. Prigov kak Brekht i Uorkhol v odnom litse, ili Golem-sovetikus. In A Non-Canonical Classic: Dmitrii Aleksandrovich Prigov (1940–2007). Edited by Evgeny Dobrenko, Ilya Kukulin, Mark Lipovetsky and Maria Maiofis. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 123–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1966. Notes on ‘Camp’, Sontag. In Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Troitsky, Artemii. 2013. Na dne. Prolog. Novaia Gazeta. April 14. Available online: https://novayagazeta.ru/articles/2013/04/15/54350-na-dne-prolog (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Turkina, Olesia, and Viktor Mazin. 2014. Zhizn’ zamechatel’nogo Monro. St. Petersburg: Novyi Muzei. [Google Scholar]

- Turkina, Olesia, and Viktor Mazin. 2013. “Svoeobrazie”. Available online: http://kolonna.mitin.com/dantes/dj02/turkina.shtml (accessed on 8 September 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).