A new man was one of the principal utopias of the Russian and European art of the early twentieth century. All sorts of cultural figures anticipated the possible and downright inevitable transformation of man in that period. Pyotr Ouspenskii, whose books were well known in artistic circles, wrote in 1911, “Man is by and large a transitional form, moving, progressing, and changing nearly before our eyes” (

Ouspenskii 1913, p. 87). Anthropological fantasies usually associated with modernist art are typically connected with human machine projects, the radical change of man’s natural form and the creation of a symbiosis of the living and the mechanical. Enthusiasm for machinery prevails in the images of a new man in the early twentieth century. However, occasionally fantasies of a human machine entered seemingly impossible interactions with vitalistic and religious ideas. Precisely such interactions became the decisive factor in the evolution of his version of new anthropology in Chekrygin’s works.

In the early twentieth century, neovitalism was a notable trend in reflections on the new man. Anti-mechanistic anthropology relied on new concepts of life, discoveries in biology and chemistry and new ideas of matter (vibration theories, radiating power, electromagnetic waves, etc.). Protoparticles of life, protoplasm and “living matter”; Hans Driesch’s entelechy governing living matter, the “cellular soul” of Ernst Haeckel and “biogenous ether” of Alexander Danilevsky are but a few examples of the vast range of ideas that promoted the spread of new views of the living organism, matter, and human body. The possibility of fathoming the depths of organic matter and transforming it not only at the level of cells but also at the invisible levels of emissions, vibrations and waves opened breathtaking prospects for creatively intervening in the human organism and changing the border between the animate and inanimate.

New anthropology fed on these ideas that were in the air and came to be discussed in scientific articles, as well as in numerous media publications, and gradually penetrated art. Tangible changes occurred in the “shape of man”. The human body lost its solid closed outline and appeared as part of the finest movements and fluctuations of the environment and space pervaded by emissions and vibrations. Such bodies can be seen in many of the pictures of the Neo-Impressionists and Futurists (G. Seurat, La Parade, 1889; G. Previati, The Return of the Pious Women, 1910; L. Russolo, Profumo, 1910; C. Carrà, Leaving the Theatre, 1910). The disconnected physicality of emissions, light waves, and electromagnetic fields appeared in works of František Kupka (Woman Picking Flowers, 1910–1911) and Marcel Duchamp (Portrait of Dr. Dumouchel, 1910).

Some Russian projects, primarily Rayonism of Mikhail Larionov and his associates, also fitted into the anti-mechanistic line of new anthropology. Closed bodies likewise disappeared from Larionov’s Rayonist works. The human body found itself drawn into light and energy flows of the surrounding space; what was more, the living body itself was capable of emitting “radiant matter” (Woman at a Table, 1912; Rayonist Portrait, 1913). Unstable, open human shapes also appeared in the works of Larionov’s associates (Mikhail Le Dantu, The Portrait of M. Fabbri, 1912, and Lady in a Café, 1910s).

Vasily Chekrygin, too, proceeded from such anti-mechanistic anthropology in his works. In the 1910s, he cooperated with Larionov and contributed to exhibitions organised by the latter. After Larionov had left Russia, Chekrygin stayed in touch with him and in his letters discussed his artistic projects in detail. Nonetheless, in his art, Chekrygin comes across rather as the antipode of Larionov. A paradoxical blend of scientific and occult thought and ideas of Christian anthropology became a crucial component of Chekrygin’s works. Unlike Larionov, who never addressed Christian iconographical sources, Chekrygin produced his anthropological project at the intersection of two cultural paradigms—one Christian and the other scientific and occult. This merger of such heterogeneous concepts was not an accidental fact of the artist’s biography. It makes it possible to see certain problems and antinomies that were fundamental to Russian culture in the 1910s.

There is an established custom of associating the concepts of a new man exclusively with secular ideas of science and philosophy. I would like to point to yet another context, that of Christianity, which is in fact primary and serves as a point of reference for philosophical and social concepts. The anthropology of change, transformation, and radical transfiguration of man (not only internal, but also of the human body) lies at the heart of the Christian view of man. The epistles of Paul the Apostle repeatedly speak of the Christian man as a goal and project to be implemented in history. The Epistle to the Colossians reads, “Do not lie to each other, since you have taken off your old self with its practices and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator” (Col. 3 9–10). Or the first letter of St John, “what we shall be has not yet been revealed. We do know that when it is revealed we shall be like him” (1 John 3: 2). The ontological transformation of man and going beyond the borders of actual human nature were set as goals and viewed as a desired prospect for the realisation of the Christian man. Man’s transformation is possible primarily as an eschatological prospect in future resurrection. That projected image of a Christian oriented towards radical transformation, no doubt, continued to play an important role in secular culture as well, frequently in the form of a covert or distorted archetype for modernist projects. This Christian context became a crucial one for Vasily Chekrygin.

A broad range of scientific and occult ideas connected with neovitalism was another component of Chekrygin’s new anthropology. Notions of the human organism going beyond its physical and chemical parameters and the presence of some “vital force” or entelechy guiding a living organism were the basic neovitalist ideas of the late nineteenth—early twentieth centuries. Already then, people observed parallels between the neovitalist ideas and certain concepts of Christian authors. Such parallels were above all encountered in thoughts about the resurrection of the dead and the dissolution of the human body. “It is easy to see in the first elements of St Gregory of Nyssa a very close similarity with the living proto elements of modern vitalist revival”, said one of the 1912 publications in

Bogoslovsky vestnik (Theological Bulletin) (

Strakhov 1912, p. 10). The primary particles of life that lie beyond the boundaries of physical being and are only noumenal, yet capable of interacting with matter to form inimitable living organisms, were a frequent motif of Christian anthropology. Athenagoras of Athens wrote about the intangible “particles of the body” that upon the death of man “combined with the elements and the universe” (

Athenagoras of Athens 2013, p. 15) and the raising of those gathering to form a new body. In the anthropology of Saint Gregory of Nyssa supersensible substance (“intelligible elements for the emergence of bodies”) consisting of “the first elements created in the beginning of creation” (

Strakhov 1912, p. 10) is viewed as the innermost foundation of the soul. These prime elements are “quite real, but bodyless and merely intelligible essences” (

Strakhov 1912, p. 10). The prime elements of the soul leave their special signs or imprints on the primary elements of the body.

1 Saint Gregory of Nyssa writes, “…some signs of our compound nature remain in the soul even after dissolution” that enable it to recognise kindred things at the moment of resurrection, and then “the soul attracts again to itself that which is its own and properly belongs to it” (

Saint Gregory of Nyssa 1861, p. 188).

Christian anthropology itself underwent certain changes way back in the nineteenth century. The outcomes of contemporaneous scientific theories and experimental scientific discoveries were frequently incorporated in theological reflections on man. The polemics between Saint Ignatius (Dmitry Brianchaninov) and Saint Theophan the Recluse was perhaps the most indicative in this respect. The debate arose in 1863 after Saint Ignatius published his

Word on Death, in which he, drawing on the contemporaneous teachings of gases, considered the human soul as a fine “ethereal body”. His ideas of the “fine ethereal corporeity” of angels and souls became commonly known. Saint Theophan reciprocated with his arguments under the expressive title

Dusha i angel—ne telo, a dukh (The Soul and Angel Are No Body but Spirit”, 1891), accusing his opponent of “ultra-materialism”. Skipping the details of their heated polemics, let me point out that Saint Theophan himself addressed the teaching of ether. He wrote about a “very subtle element” that “penetrates and passes everywhere, serving as the smallest particle of material substance”; “the soul itself is the immaterial spirit; but its covering is made from this ethereal immaterial element” (

Saint Theophan the Recluse 2012, p. 51). What is more, in his texts Saint Theophan used modern images such as electricity, wireless telegraphy and emissions to describe the effect of prayer and communication with the spirit (

Saint Theophan the Recluse 2012, p. 57). Similar views (of course with significant corrections) were also common among the spiritualists and theosophists. In his early works

Souls (1914–1915, see

Figure 1) Chekrygin nearly literally reproduced the ethereal corporeity of the soul that was much written about in those years. The glowing outlines of bodies in his work reference, for instance, Saint Theophan’s descriptions of the immaterial angelic vision capable of seeing the ethereal body of the soul: “Then, having turned your gaze upon the earth, you would see among the varied masses of people bright shades, semi-bright, hazy, murky” (

Saint Theophan the Recluse 2012, p. 53).

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the entire atmosphere of early twentieth-century culture was pervaded with the ideas of new anthropology, in which Christian, scientific and occult ideas occasionally formed a paradoxical fusion. That atmosphere became the cultural context in which Vasily Chekrygin developed his ideas.

Another important context of his anthropology had to do with radical fantasies and expectations born of the 1917 Russian revolution. The conceptions of the radical transformation of man formed a significant part of Russian culture in the post-revolutionary period. In these theories, socio-political radicalism frequently accompanied anthropological radicalism. Dreams of the ultimate revolution that was to transform human nature and free man from the last bondage of death inspired anarcho-futurists, biocosmists and members of the Proletkult.

2 The attainment of immortality and the raising of the dead were discussed in the 1920s as the pressing objectives set by the revolutionary epoch. P. Ivanitsky (member of the biocosmist group) wrote in those years, “proletarian mankind will of course not confine themselves to securing immortality only for the living, they will not forget those who have fallen to accomplish this social ideal, they will undertake to free ‘the last of the oppressed’, to raise those who lived in the past. After all, the material basis of man (the atoms of his organism) does not disappear in principle, and consequently there is hope for its restoration” (

Ivanitskii 1921, p. 8). In their reflections, artists and men of letters addressed not only the philosophical legacy of Nikolai Fyodorov, but also the numerous scientific experiments of the early twentieth century. In Russia, both before and after the revolution, scientists attempted to resuscitate (individual organs, parts of the body or cells of a living organism) and extend life through cryopreservation or anabiosis.

3 Biocosmist A. Svyatogor wrote in that period, “Unprecedented grand prospects are opening up before man (mankind). Struggle against death is no longer fundamentally impossible (experiments of Steinach, Andreyev, Kravkov, etc.). The possibility of individual immortality can already be substantiated scientifically, while accomplishments of physics and technology give grounds to raise the cosmic problem (interplanetarism) scientifically. <…> The ultimate aspiration is immortal life in space. The ultimate evil is death. (…) The postulated problem strongly requires man to be free” (

Svyatogor 2008, p. 414).

It was in this space of culture, where the problem of transforming human nature occupied pride of place, that Vasily Chekrygin developed his ideas.

Rayonism can be considered the starting point for Chekrygin’s anthropological fantasies in art. In one of his texts, he pointed out, “I would like to paint with rays of light” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 222). In a 1921 letter to Mikhail Larionov Chekrygin spoke of “light as an instrument of revivers” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 195). The new body of the risen man is made of rays of light. Mentioning that repeatedly in his texts, he spoke of “the revelation of the human body in light” or about “man in the whirlwind of his tribe swept in time like a fiery column” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 246). He pictured the creation/resurrection of a new body as construction “from fiery grains (atoms, electrons)” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 247).

In his reasoning about the risen flesh, Chekrygin also proceeded from the theory of “luminiferous ether” that transmitted and sustained the vibrations of all atoms forming bodies. It was in that light-bearing environment that at the moment of resurrection the original elements of human bodies scattered in cosmos would be able to recognise one another by subtle vibrations and reunite in a new body. In one of his manuscripts, Chekrygin described the process of the ultimate transformation of the human body in terms of the scientific and occult knowledge of his time as follows, “The son has in his hand the ray weapon of Resurrection. The process and way of the conversion of rays can be presented in the following way, the vibration or convulsion to which the particles were subjected inside the organism continue upon their release from the organism and the destruction of the body <…> From these convulsions the rays, penetrating towards the surface, go together with the reflected and other rays, forming not only the outer image and those living on it, but also the inner one with the dead decomposing in it <…> The construction activity of the rays begins here. <…> the rays bear in them the images of the creatures who lived and then died, the images of the bodies decomposed into particles, these rays, meeting the particles, reunite the pictured gaseous molecules of the atmosphere with the solid ones on earth <…> into living bodies” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 41). For Chekrygin the human body is a subtle physiology of fluctuations, vibrations, emissions, and light and electromagnetic waves. It is within this occult and scientific mechanics of the recreation of a new body that traces gleam, or the ruins of the Christian tradition are discerned.

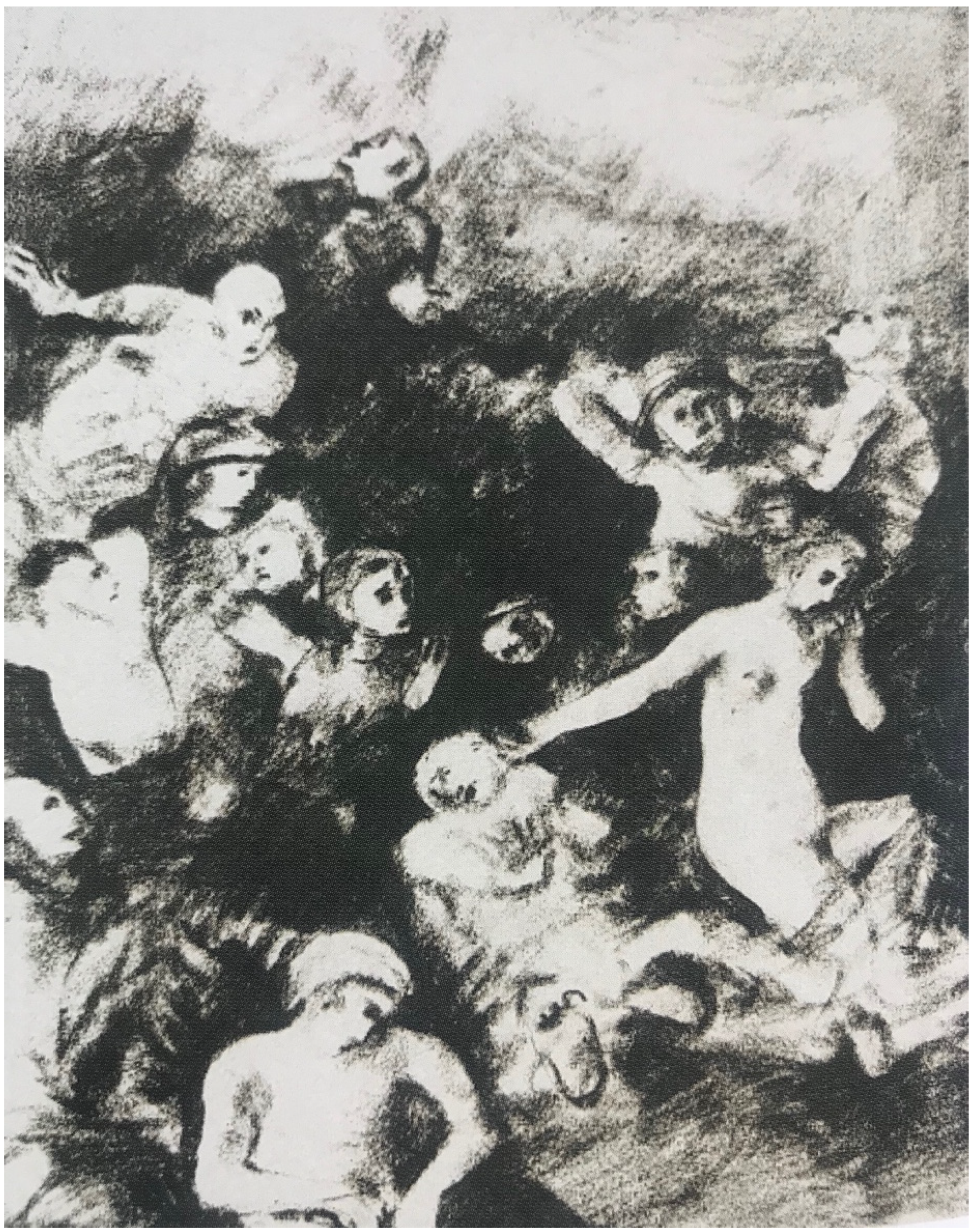

The destiny of the human body, the different metamorphoses that it undergoes or can undergo in the future, flesh itself and matter are always at the heart of Chekrygin’s anthropology. The normal static human body remains at the periphery of his interests. Chekrygin is above all interested in the changed, decomposing, or reconstituted human body, a body in extreme conditions. In his series

Execution by Shooting (1920, see

Figure 2),

Crazy People (1921–1922),

Orgies (1918) and

Povolzhye Famine (1922, see

Figure 3) he examined man at the borderline moments of being.

Pregnancy (1913) was yet another motif of interest to Chekrygin that also had to do with changing corporality. And finally, the main theme of Chekrygin’s works of the final years of his life—the raising of the dead—references the most radical transformation that the human body can undergo.

4 An important feature of Chekrygin’s works is his direct reliance on Christian iconography and, above all, the iconography of bodily transformations.

5 References to such iconography can be encountered in quite a few of his works. Just a few of them will be mentioned below.

Adam and Eve (1913) pictures the moment of their loss of heavenly physicality and acquisition of “garments of skin”.

Three Figures (1914–1915, see

Figure 4) references the iconography of the Transfiguration, when according to Saint Gregory Palamas, “(the disciples) of the Lord <…> passed beyond mere flesh into spirit through a transformation of their senses” (

Lossky 1991, p. 368). The same theme is elaborated in

The Transformation of Flesh into Spirit (1913, see

Figure 5). Traces of the traditional iconography of

The Descent into Hell are discernible in the nearly abstract mass of colour on the canvas. A study for

Down with Illiteracy (1920) is associated with the iconography of the Ascension.

Chekrygin is literally enchanted by the phenomenon of transforming physicality. He sees the mystery of the Eucharist as the archetype for every transformation of flesh, as well as for artistic creativity that transforms natural matter into a work of art. In his notes he repeatedly writes about that: “Creativity is the sheer Eucharist, the supreme creation regardless of time and space” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 166). The mystery of the Eucharist enables him to describe the creative process itself as the transformation of the natural matter the artist works with. Chekrygin writes that the artist “does not know in the Eucharist of creativity where his flesh is—in the chalice on the altar or he is in it. Time and space recede, and it is the artist’s flesh in the altar, the chalice, and the wine is his blood while flesh is matter, stone, canvas. This is a mystery” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 166). Chekrygin’s interest in the Eucharist resides in the context of that period’s general excitement about the problems of material world transformations, transformation/disappearance of matter and, on the other hand, the discovery of the materiality of the mind and the invisible.

A characteristic of Chekrygin’s references to Christian iconography is their “ruined” state. The artist extracts the very core and essence from his iconographic references, e.g., the figures of Christ, Moses or Elijah, that is, the very phenomenon of transfiguration from

The Transfiguration, and leaves in the figures of the Apostles, that is, just signs of trauma and shock. In

The Descent into Hell there remain traces of images barely discernible in the play of colours and in

The Ascension only the column of light or blank space amidst the crowd and hands raised to heaven. And, finally, in one of the drawings of

The Raising of the Dead series (see

Figure 6) there remains only the empty mandorla and the cross of the traditional iconography of

The Descent into Hell, while the figure of Christ effecting the transfiguration of man disappears. These deletions from the iconography are not fortuitous. Chekrygin’s man exists on the ruins of the Christian world. His man is a sign of trauma. Christianity itself is rather a trauma for Chekrygin, a traumatic memory or magic instrument, the entire skill of using which has been forgotten. In one of his letters of 1915 he characteristically admits, “I am no Christian or Buddhist but mostly a pagan, or to be more correct, all of them put together” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 158).

The ideas of Nikolai Fyodorov, whose works Chekrygin got to know only in late 1920 shortly before his death, merely gave a boost to his extreme conclusions and radicalised the motifs he had already had. At the same time, it was Fyodorov’s concepts that imparted a definite bioengineering tenor to all Chekrygin’s constructs and turned his Eucharist creativity into a “common cause” or “common enterprise”, cosmic liturgy outside of church.

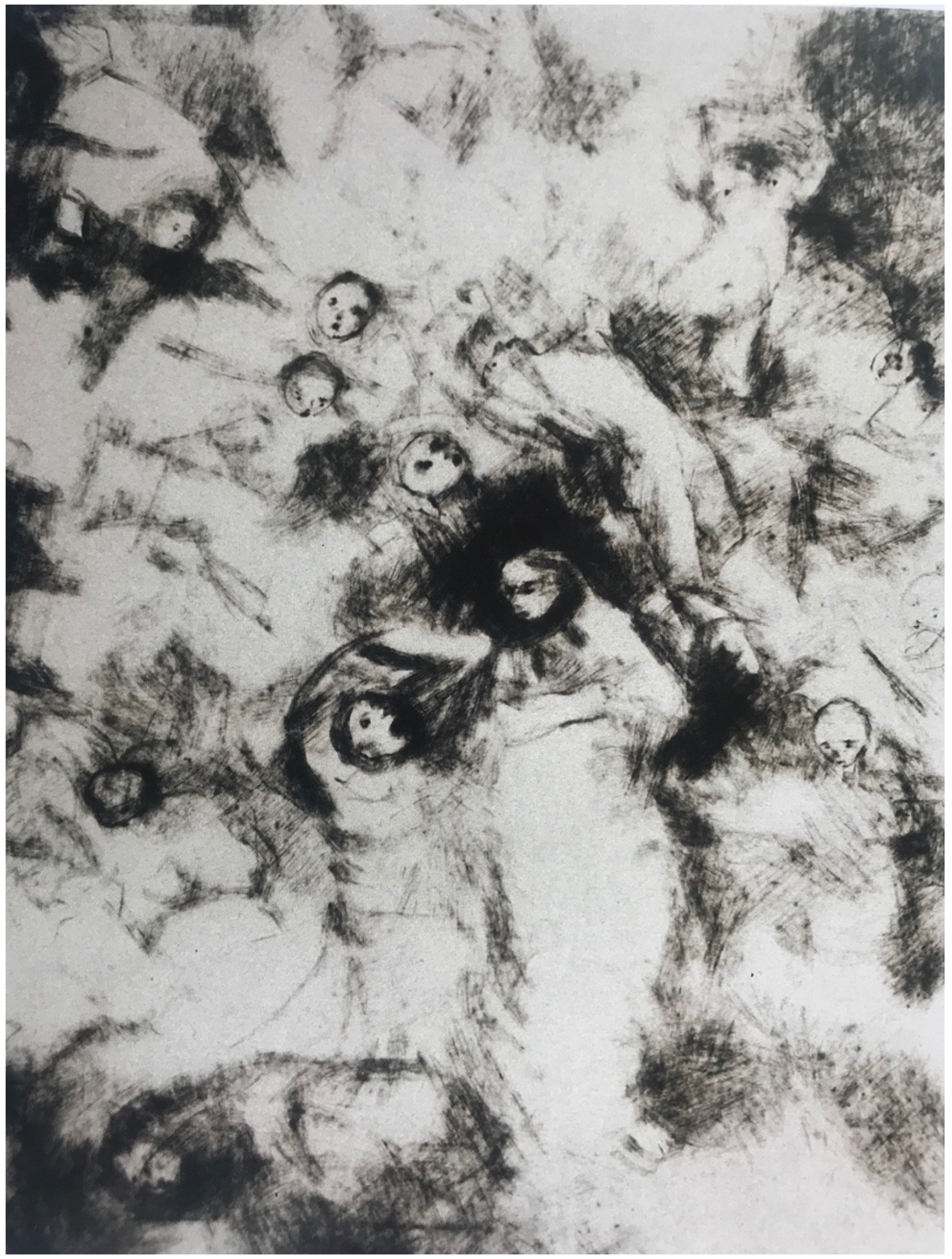

His most radical statement on new anthropology was a series of works (or rather hundreds of graphic sheets) that Chekrygin made as studies for monumental paintings for the Cathedral of the Reviving Museum. The raised bodies of Chekrygin are the result of bioengineering—the regulation of light flows and control over atoms, prime particles, and vibrations of “luminiferous ether”. They appear outside the Christian prospect of resurrection and as a result of the technical magic of manipulation of matter. The hundreds of drawings made by Chekrygin in the final years of his life are astounding in their agonising monotony and endless repetition of the same thing. All the compositions consist of heaps of bodies twisted into balls and glued together into a horrendous biomass. His mystery of human transformation shows a mass of people either rising from the dark or falling into cosmic darkness. His bodies are drawn into an endless and inextricable process of the transformation of matter. It is never nor can ever be finished. The vortex of bodies is like the eternal gyre of the elements of nature (see

Figure 7).

Chekrygin’s images of new man raised by the force of reason and science are captivating with their grandiose and daring concept and at the same time off-putting with their wearisome repetition and monotony. The closest parallel is the description of the world of the Titans from Greek mythology offered by Friedrich Jünger. According to him, the world of the Titans, in which there are no Gods, is “an eternal vortex closed in itself” and “coming into being that has no point of support outside itself and is anxiously going back and forth as an ebb and flow”; it “produces nothing mature, nothing accomplished” (

Jünger 2006, pp. 55, 62). Many contemporaries saw the same monotony and hopelessness in Fyodorov’s philosophy. In his philosophical conceptions, according to one of the reviewers, “history short of loses its creative character and becomes a restricted vortex of forces: all it has is the mixing and restoration of the primordially given elements” (

Golovanenko 1915, p. 502).

The iconographical prototypes for Chekrygin’s “common cause” can be identified primarily in scenes of the Last Judgement and the torment of sinners. His man (see

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) arising from nonexistence agonisingly goes through resurrection very much like human bodies go through hell. It seems that the pictorial language per se, which is deeply rooted in traditional religious iconography and from which Chekrygin cannot nor wants to break free, “leaks a word” about a deep conflict: the insoluble problem of victory over death without Divine involvement in the process of Resurrection. Like many of his works based on Christian iconography, his scenes of the restoration of human bodies are distinguished by a characteristic “gap”, an incomplete process, and the loss of a conceptual focus. A well-known passage from the Book of Ezekiel on bringing “dry bones” back to life is best suited to describing that incomplete and unfinished process of restoring man involving bodies in Chekrygin’s liturgy outside of church: “Then he said to me, ‘Prophesy over these bones, and tell them: Dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. This is what the sovereign Lord says to these bones: Look, I am about to infuse breath into you and you will live. I will put tendons on you and muscles over you and will cover you with skin; I will put breath in you and you will live. Then you will know that I am the Lord.’ So I prophesied as I was commanded. There was a sound when I prophesied—I heard a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to bone. As I watched, I saw tendons on them, then muscles appeared, and skin covered over them from above, but there was no breath in them” (Ezekiel 37:4–8).

Chekrygin’s cosmic liturgy and his religious technological project of making a new man in fact negated the centerpiece of Christian faith—the redemptive sacrifice and Second Coming. He replaced messianic expectations and the unknown historical perspective open for creativity with mechanical collective work and consistent regulation of the eternal cycling of matter in nature. At the heart of his teaching of man is care about the future of man’s dust and body and the unconditional prevalence of the ancestral and collective over things personal (see

Figure 11 and

Figure 12). His new man is entirely and inevitably subordinated to the collective liberation project. However, the coveted freedom from death leads to total dependence: the new man remains forever shut in the cosmic vortex of natural matter. Chekrygin’s anthropology reflects the inherent and insoluble antinomy of Russian culture of the revolutionary period, on the one hand, and, in a broader sense, of the entire modern epoch, on the other, and looking further forward, modernity, when every titanic stride towards human freedom results in its loss at an increasingly deeper level. His Cathedral of the Reviving Museum comes across as a prelude to the alarming and intriguing biotechnologies of our day and the images of current biopower that is penetrating human life ever deeper and more comprehensively.

In Chekrygin’s works, the contours of new anthropology loom out of the ruins of Christian images. This is the fundamental difference between his anthropology and the many fantasies of his contemporaries. Unlike, for example, biocosmists or proletarian poets, who just parodied Christian motifs and images (“The Gospel According to the Mare” by the biocosmist A. Svyatogor and “The Iron Messiah” by the proletarian poet V. Kirillov), Chekrygin was profoundly traumatised by the ruins of the Christian world. In his projects Christianity manifests itself only as a trace, “the mark, perceptible to the senses, which some phenomenon, in itself inaccessible, has left behind” (

Bloch 1973, p. 33). It is these traces of Christian culture discernible behind bioengineering fantasies that imbue Chekrygin’s works with a real dramatic effect. “I used to think,” the artist wrote, “that creation comes easy. That ‘out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks’. It speaks out of the tormented heart. My art sees life that is ominous, the life of the flesh. In its fall it feels heavens far stronger” (

Murina and Rakitin 2005, p. 224).