One of the clichés of scholarship on conceptual art concerns the supposed “dematerialization” of the object and its replacement by a notion of “art as idea”.

1 That has been a truism about conceptualism in the West since the publication of Lucy Lippard’s groundbreaking volume on the subject in Anglo-American conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it is still a commonplace in studies of conceptualism around the world. Yet recent studies have suggested that the transformation of the concrete object in conceptual art is both more complex and less widespread than expected, even in the work of the Art & Language artists Lippard favored. Christian Berger is just one of the scholars calling for an approach to Anglo-American conceptual art that is “not so rigidly ‘anti-materialist’” and for a “more holistic view” of the phenomenon worldwide as well (

Berger 2019, p. 15).

2 Once we look closer, it becomes clear that the supposed disappearance of the concrete work of art played a more limited role than expected both East and West. For a significant group of unofficial artists in the late Soviet Union in particular, the conceptual object—far from being replaced by the idea—actually provided a path to return meaning, community, and agency to the practice of art. Creative focus on material objects allowed unofficial artists in the late Soviet Union to move beyond modernist ideas of artistic autonomy and nonconformist spirituality to a more broadly accessible, collaborative model of art situated in continual practice. In one of the many underappreciated aspects of Moscow conceptualism, a select group of artists used materiality and the concrete object as a postmodern springboard to return both sense and sensibility to unofficial art, moving as they did from a notion of “art as idea” to the related and equally revolutionary notion of “art as communication, dialogue, and embodied meaning”.

3 Acknowledgement of the importance of the concrete object to these artists and of their role in the development of Moscow conceptualism is essential for a fuller understanding of both the movement as a whole and its relevance to developments in global conceptualism.

Descriptions of Moscow conceptualism have generally focused on disembodied and dematerialized artworks, particularly the ephemeral and esoteric works of Ilya Kabakov, Andrei Monastyrski’s Collective Actions, and others, to the exclusion of more direct, materially grounded, and collaborative conceptual work. Primed to see the effects of Soviet “logocentrism” everywhere, observers have frequently treated the substitution of text for object as a near inevitability in the post-Stalin era, explaining it as an expected outcome of the “hypertrophy of the text” that supposedly accompanied the “atrophy of the image” (

Debray 2007, p. 12) throughout the post-war Soviet bloc.

4 Boris Groys’s assertion that “Soviet culture had always been conceptual…in its entirety” both typifies and strives to justify such an approach (

Groys 2008, p. 31).

5 Contending that conceptualism in Russia was characterized by the “deliberate presentation of ideas denuded of their material referent”, Mikhail Epstein argues that “pointing to [such] emptiness” is what distinguishes conceptualism in Russia from its Western counterpart (

Epstein 1995, p. 35). Leaving minimal traces of its physical existence, such disembodied work is often deliberately detached from its surroundings, unforthcoming or deceptive about its origins, stripped of materiality, and focused on thought and cognition over everyday process and negotiated real-world practice.

Such commentary, although compelling for the work of certain unofficial artists in the Soviet Union, obscures the unexpectedly central role that concrete objects played in the work of other Moscow conceptualists, beginning in the mid-1970s. That is particularly the case for the Nest, an influential group of artists active from 1974 to 1979 largely excluded from the current limited “canon” of Moscow conceptualism.

6 Nest artists frequently relied on extremely literal, over-realized metaphors in their efforts to expand the possibilities for artistic expression in the late Soviet Union. Such works typically included performative elements that required artists and spectators alike to acknowledge the interplay between rhetorical metaphors and their solid, tangible, often crude material manifestations in the real world. The performative elements of such “embodied” works emphasized the role even uninitiated observers play in making meaning manifest, further opening artistic inquiry to postmodern input from multiple sources. As a result, these concrete objects served as useful tools in liberating unofficial art from the confines of Socialist Realist strictures and nonconformist pieties alike. My closer look here suggests their particular importance in the Moscow conceptualist shift from modernism to postmodernism.

Focus on texture and tactility, or

faktura, had been central to the Russian avant-garde, and it might be easy to imagine a connection between those early twentieth-century calls for the importance of material culture and the embodied metaphors of these late-Soviet unofficial artists.

7 But Nest artists Gennady Donskoy, Mikhail Roshal, and Victor Skersis, had relatively little information about the historic avant-garde and scant interest in exploring it. They inherited their understanding of the material object primarily from their teachers Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid

8 and from their own creative reinterpretation of dilemmas that Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, and other Western artists had left unanswered. In fact, their shared attention to materiality helps distinguish the work of these “analytical conceptualists”, including Yuri Albert, Vadim Zakharov, Nadezhda Stolpovskaya, and others, from that of their contemporaries.

9 Like most people in the late-Soviet unofficial art milieu, these artists, too, had noticed the disjunction between word and image around them: as official Soviet rhetoric grew further and further detached from the world of the signified, the denotative meanings of words had less and less connection to the material world they allegedly described. Kabakov describes the response of artists in his circle to this situation, noting “there was a complete absence of pragmatic subject matter. Any approach to that sphere was understood as painful dissonance” (

Kabakov and Epstein 2010, p. 63). Rather than retreating from the world of everyday things and

byt, as those contemporaries did, however,

10 the Nest and other analytical conceptualists chose to highlight the stubborn literality of the objects around them, insisting on their material existence and their importance to the collectively determined meanings of the metaphors they reified.

Their approach did not include close attention to aesthetic beauty or the physical attributes of objects for “art’s sake”, naturally, but signaled instead these artists’ insistence on the real-world connections of their artistic activity. By fully “realizing” the rhetorical metaphors that surrounded them and reinvesting official and shared language with hard-edged contours, the Nest occasionally bordered on a pleonastic use of language that critics and even some fellow artists dismissed. Curators of the 2005 retrospective exhibit

Accomplices, for example, called their approach “naively idiotic”(

Erofeev et al. 2005, p. 40). Some of the Nest’s own later explanations of their work seem to encourage such an interpretation: Nest artist Roshal, for example, noted the group’s tendency to take the principle of “art as action, action as life and so on” to “the absurd” (

Roshal 2008, p. 53). Art historian Octavian Eşanu explains this Nest technique as the artists’ supposed interest in “literal illustration” and dismisses it as “short-lived puns…quickly understood” (

Eșanu 2013, pp. 98–99). Yet such interpretations miss the point, mistaking extended length, intricate structure, and retention of final artistic control for conceptual depth. As a comment by Gayatri Spivak makes clear, however, the disarming micronarrative is a powerful tool in disrupting power imbalances. Commenting on the need to overcome lingering colonial histories, for example, she argues that “the alternative to Europe’s long story—generally translated ‘great narratives’—is not only short tales (

petits récits), but tampering with the authority of storylines” (

Spivak 1990, p. 228). In the late-Soviet environment also, “short-lived puns…quickly understood” were often the best antidote to a totalizing State monologue.

The willful and intentionally comic “misreadings” of language that result from the Nest’s close focus on materiality thus serve a serious purpose: by highlighting the concreteness of such literal meaning, the artists direct viewers’ attention to the necessity of continual interpretation and artistic engagement with the world around them. Analytical conceptualists saw what Yuri Albert calls their “Art of short stories and quick perception”

11 as a way to reengage with the contingent meanings of everyday life, establish the validity of their own postmodern investigations into the meaning of art, and encourage others to join them in an unconstrained artistic process open to all. By insisting on the literal meaning of words and opening up the dialogue to others, these artists claim real-world authenticity for their work while rejecting modernist notions of transcendent spirituality and artistic autonomy and keeping it safely grounded in the contingent. The resulting conceits expose the actual dimensions of each figure of speech in order to insist that users of the language comprehend their own interactions with such commonplace metaphors and their real-world implications in context. Their focus on materiality did not preclude disembodied works of art. In fact, these artists created a number of such works themselves, fully embracing the occasional utility of such an approach in their ongoing investigations of the fundamental question “what is art”. It is also worth noting that literality in the hands of these artists destabilizes meaning as often as it reveals it. But their early emphasis on performing embodied materiality was essential, a needed next step in conceptual art as a whole and crucial to the liberation of the late-Soviet unofficial art world. These artists saw from the beginning that exclusive focus on the disembodied, the spiritual, “art as idea”, or any other single-minded approach to the varied discipline of art would eventually lead to a creative impasse. As we will see, their investigations into object and metaphor in the late-Soviet period expand on lessons from semiotics, Formalism, and conceptual art to argue for a postmodern approach aimed at unscripted experimentation and collaborative investigation into the question of how art is made.

Komar and Melamid had demonstrated that mass-produced texts, like mass-produced artistic reproductions, belonged to everyone in the Soviet ecosystem. Nest artists made that lesson part of their overall project to return meaning, accountability, shared comprehensibility, and delight to the individual utterance, assigning actual weight to language that had otherwise lost its everyday connection to “fragile human existence”.

12 In the Soviet atmosphere of high-flown rhetoric and grandiloquent speechifying, their focus on the humorous and real-world implications of the words and images they used was unexpected even for those in the unofficial art world. Despite their hatred of empty rhetoric, most unofficial artists in the mid-1970s were committed to an exalted model of artistic endeavor in which the creative individual produced “hermetic” works of such “mystical, irrational, or spiritual” intent that they required the artist’s (or the informed specialist’s) interpretation.

13 In contradistinction to both official and underground approaches, however, Nest artists imagined assigning real weight to the everyday concepts that had lost their real-world signifiers and become nothing but hot air. Their little-known work

Mevkopizsan (Material Equivalent of the Air Fluctuations of Specific Periodicity and the Symbolic Markings Associated with It) (

Material’nyj Ekvivalent Vosdushnykh Kolebanii Osoboi Periodichnosti i Znakovoi Simvoliki Assotsiirovannoi s Nim), for example, involved a new periodic table of sorts in which each letter in the Russian alphabet was assigned a specific weight. The letter “A” was equal to 1 g; “Б” 2 g; “B” 3 g, and so on. The “weight” of a specific word—calculated whimsically according to the “fluctuation of air” that accompanies the pronunciation of each phoneme—combined the individual masses of each letter. To make the resulting “material equivalent of [such] air fluctuations” visible and palpable, the artists conceptualized metal cylinders equal to the summary mass of each individual’s name in a strictly personalized construction. Using “scientific” methodology humorously to make a serious point, the resulting cylinders—unfortunately none extant—offered concrete and graphic evidence of the Nest’s new approach to the language of art. Their primary focus with

Mevkopizsan was to engage others in an individualized and constantly evolving conversation about the continually developing discipline of art. Cleansing humor was an essential part of that.

14 Thus, the artists laughingly promise that others will have the ability “not only to hear their own name, but also to sniff, lick, and do much, much more to it”.

15 The project, amusing and self-affirming, is educational as well. Each creation serves as a realized metaphor, announcing to would-be participants that words—with actual dimensions, specific meaning, and value—need their close attention and care. By interacting physically with embodied written texts, participants learn that they too have artistic agency and can mean what they say. The Nest’s lighthearted and determinedly material touch renders the serious endeavor of returning sense to everyday discussions open to all.

Nest artists continued to focus attention on the physical, concrete, and literal in their path-breaking performance piece

Hatching a Spirit (

Vysizhivanie dukha) (

Figure 1). The work, exhibited publicly for the first time at the watershed VDNKh exhibit in 1975,

16 played consciously on the amorphous spirituality that characterized much of the Russian avant-garde and late-Soviet unofficial art as well. But the Nest replaced exalted calls for ephemeral spirituality (

dukhovnost’) with a real egg in an actual nest of leaves and branches that announced the artists’ freedom from both official and disembodied unofficial art and issued a general invitation for others to join them in the generation of embodied artistic meaning. Convinced they were creating “the most radical of events, even compared to things like Chris Burden’s body art”, the Nest envisioned their work as a “re-evaluation of all the principles of art” (

Skersis 2014, p. 149).

17 To achieve that goal, the artists made a virtue of collaboration, fully embodying their practice by occupying the nest publicly and cultivating an inclusive model of creation based on co-authorship (

so-avtorstvo). Each artwork figured as a succinct and negotiated contribution to an ongoing dialogue intended as neither authoritarian nor sectarian but open and democratic.

Eye-catching, accessible, and fun, the young artists’ multi-day, interactive space became a focal point of the exhibit, their open invitation to all who wished to join them in the nest for unscripted artistic performances of their own. Such public displays were so unprecedented that art historian Vitaly Patsyukov considered the coordinates of the nest itself the center of the entire exhibit, arguing that such performative works by the group served to release Russian art from the constraints of “fundamental traditions”.

18 Artist Viktor Pivovarov remembers it as “revolutionary in the extreme” (

Pivovarov 2014, p. 136). As Daniil Leiderman has argued, certain late-Soviet artists adopted a “strategy of shimmering”, or

mertsanie, as the best way to avoid becoming trapped in any single discourse, avoiding final identification with a single language by “alternately becoming caught up with one and then the other opposing discourse, repeatedly betraying them for one another”(

Leiderman 2018, p. 52).

19 The Nest posited a different approach to making art in the real world, largely abandoning the modernist pretense of even temporarily autonomous art to embrace the cacophony of postmodern dialogue. In these public, collaborative, open-ended, performative works, there was no privileged observer to override the actions of the “Other”, no “shimmering” authorial persona with a final say over meaning. In fact,

Hatching a Spirit and other such Nest works demonstrated just the opposite, insisting that we are all in the same boat (or nest), hatched from the same egg, and required to negotiate the contours of our shared language together. The Nest’s artistic mission included their investigation of the limits of that common language and repeated attempts to expand on its creative potential, but their rejection of the ephemeral “spirituality” of disembodied artwork in favor of direct engagement with meaning in the real world could not have been more resolute.

For these artists, solidity, literal meaning, and tangibility refocus attention on the possibility—the necessity—of action as the signifier of a concept. The Nest’s performative 1975 work

Pump the Red Pump! (

Kachaite krasnyi nasos!) invited spectators at VDNKh to choose between two bicycle pumps—a red pump of détente and a black one of international tension—and thus demonstrate their commitment to global dialogue by pumping the red pump “in the name of peace on earth” (

Figure 2).

In

Thermography of Maxim Gorky, another tactile work from the same year, participants are jokingly encouraged to imagine the life of the writer, one of the founders of Socialist Realism, by touching a heated metal plate to distinguish warm moments of apparent artistic passion from colder points of his life.

20 The work makes graphically clear the liberating effect their focus on materiality had for the Nest (

Figure 3). “What’s the point of paint and canvas?” Skersis asks in recalling the group’s creation of the work (

Skersis 2008b, p. 11). No longer tied to traditional notions of visual art, the Nest was free to focus on alternative media and genres, particularly on unstructured performative works, that helped transform the unofficial art world.

Their work

Communication Tube (

Kommunikatsionnaia truba), which was also first displayed at VDNKh, was equally literal and interactive.

21 The metal cylinder retained evidence of an official lineage in the bright Soviet-red paint that covered it (

Figure 4). Yet because the tube needed at least two individuals in order to “function”, the object theorized not monologic communiques from on high, but an active process of dialogue and communication between willing individuals. Participants soon learned that the tube was able to facilitate genuine conversation instead of official pronouncements, positing not passive spectators but real contributors capable of constructing their own individual messages. That was the point of the object: the Tube was an “essential item for communication” in this “century of isolation”, allowing participants “to look or listen to one another” (

Skersis 1981). The implied interactivity of such works was essential to the Nest. For this group of artists, art no longer involved a staged activity conducted by an artist directing others to an immutable truth, but rather an unstructured, open, and constantly evolving postmodern conversation about art that is itself continually changing. Their works returned the idea of humorous, genuine, pleasurable human communication to art and placed it literally in the hands of individual agents. Skersis describes the process as leading words from the level of “metaphor to the level of concrete expression”, insisting on the notion of a concept that moves from its “overinflated” position in a “hyper-system” to be “transformed into a literality”. We were “struck by that”, Skersis continues, and by the fact that “once you simply take those metaphors literally”, then the ideas and concepts that had “hung over everything, that explained that was going on” now “turn out to be something different”. According to him, the process changed the constrained Soviet situation completely, making it “comprehensible” and “clear”, and leaving artists free to act.

22Their insistence on employing realized metaphors to reconnect hegemonic ideas from Soviet discourse with their material embodiments in the real world requires the artists to deny, at least temporarily, the existence of such multi-stable images in the world around them. As W. J. T. Mitchell notes, multi-stable images often function to evoke a “threshold experience” in which “time and space, figure and ground, subject and object play an endless game of ‘see-saw’” (

Mitchell 1994, p. 46). Arguing that such meta-pictures serve as emblems of “resistance to stable interpretation”, Mitchell contends that multi-stable images are what “allow us to observe observers” (

Mitchell 1994, p. 49). Mitchell’s “see-saw” metaphor, however, like Wittgenstein’s famous Duck-Rabbit, moves back and forth between only two possibilities. When Nest artists juxtaposed demonstratively concrete objects to the rhetorical system of over-determined language and images that characterized life in the Soviet Union, they clearly wanted to confront that binary system with tactile evidence of its ideological overreach. In their restless, collaborative explorations of the role of materiality in meaning, however, they also saw the folly of trying to position themselves as supposedly independent observers of that same environment. Rejecting the modernist, either-or dichotomy that would restrict them to a game they no longer wished to play, these artists conceptualized instead a postmodern world of myriad possibilities, each firmly grounded in a decidedly contingent material world.

Such a corrective was particularly needed in the late-Soviet context where, as Piotr Piotrowski points out, the modernist paradigm continued “its programmatic investment in autonomy” long after it was abandoned elsewhere.

23 The Nest was moved by the solidity of all the words they incorporated into their work, and their creations played on this directly, using textual specularity and tactility in a bid to enhance—rather than debase—language’s communicative functions. Their approach was not on language as the “universal expression of the Other”, supposedly “predestined and even imposed from outside” (

Bobrinskaya 2012, pp. 190–91). In their work, language hews closer to the “death of the author” that Roland Barthes imagined: “not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the ‘message’ of the Author-God) but a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash” (

Barthes 1977, p. 146). Some of Barthes’s work was undoubtedly familiar to these artists: a translated excerpt from

Writing Degree Zero, with its discussion of Saussure’s distinction between “langue” (language/

iazyk) and “parole” (speech/

rech’), and the distinction between the signified (

oznachaemoe) and the signifier (

oznachaiushchee), appeared in a 1975 volume published in Moscow, and Skersis remembers that it was of general interest.

24 He and his colleagues were struck by the Saussurean notion that meaning was unstable, established in a complicated negotiation process between interlocutors endlessly conducted on the vast territory of shared language. That idea was the fertile ground on which many Nest artworks sprouted, and it served as powerful inspiration for Skersis’s work as a solo artist as well, as these artists pushed the idea of verbal instability and cognitive play to its logical limits.

The Nest’s 1976 work

Iron Curtain is the most obvious example since it interrogates the predictive power of words and their visual representation (

Figure 5). The simplicity, density, and tactility of their “Iron Curtain” seems the literal embodiment of oppressive language, Churchill’s words in the original English appearing to reflect the Nest’s own doubly marginalized position in relation to them. The question of artistic hegemony arises naturally once that abstract concept is made concrete. Yet the Nest’s found object disturbs both sides of the East-West equation, condensing and concentrating the post-war period, offering the phrase and its history for spectator delectation, reinterpretation, and re-use. By rendering the phrase and the concept it represents in concrete form, the artists reveal the ephemeral underpinnings of that tyrannical threat. Their palpable object is real iron, and it rusts. The Iron Curtain works as embodied thought, its tangibility serving to capture the political debate and render those polarities human-size and harmless. It is aimed, then, not at “seizing the apparatus of value-coding” (

Spivak 1990, p. 228), but at alerting spectators to the totalitarian project and urging them to evaluate it for themselves. These supposedly silent late-Soviet subalterns are multilingual, their real-world curtain—scavenged from a Soviet building site—extending the invitation to speak to other citizen-artists. Authority now resides not with the artists—or even the artistic spectator, as we are accustomed to claiming for postmodernism—but with the larger community.

Less convinced of their complete isolation than their older colleagues, the analytical conceptualists imagined themselves as integral parts of a global conversation about art to which they might contribute directly. With that in mind, the apparent simplicity of their literality becomes a canny artistic device, as in the Nest’s 1977 work

Let’s Become One Meter Closer! (

Stanem na metr blizhe!) (

Figure 6). That lighthearted work engaged participants on both sides of the artificial boundary separating East and West in the excavation of half a meter of the soil separating them in an attempt to draw people both physically and psychologically closer. This cheerful play with realized metaphor and the artists’ relaxed irony toward official rhetoric underlines their ongoing emphasis on concrete and unpretentious communication. In a world grounded in authorized predictability and centralized communication, the direct utterance holds genuine power, as the Nest’s work

Art to the Masses (

Iskusstvo v massy) makes clear (

Figure 7). Interpreting Lenin’s slogan “

Art Belongs to the People” literally, the artists brashly shared their art directly with the “masses”, demonstrating a Soviet banner rewritten as an abstract expressionist slogan on a busy Moscow street in 1978. Their skewed citation of Franz Kline’s

Accent Grave in the work indicates an underlying optimism about the possibility of connection that was missing from most other Moscow conceptualist work.

That creative focus on communication, citation, and shifting signifiers continued to interest these artists once the Nest unraveled in 1979. Skersis plays with denotation and connotation in a number of works from that year that were influenced by Joseph Kosuth, especially Kosuth’s classic conceptual piece

One and Three Chairs from 1965. Kosuth’s artwork draws equivalences between the actual chair the artist displayed, a photograph of a chair, and a dictionary description of that named object, and he comments in a 1970 interview that the artwork proved that “formal components weren’t important” (

Kosuth 1992, p. 225).

25 Skersis, noting that he and the other Nest artists considered themselves part of a larger circle that included “Joseph Kosuth, Andy Warhol, Yves Klein, and, of course, the majestic Marcel Duchamp” (

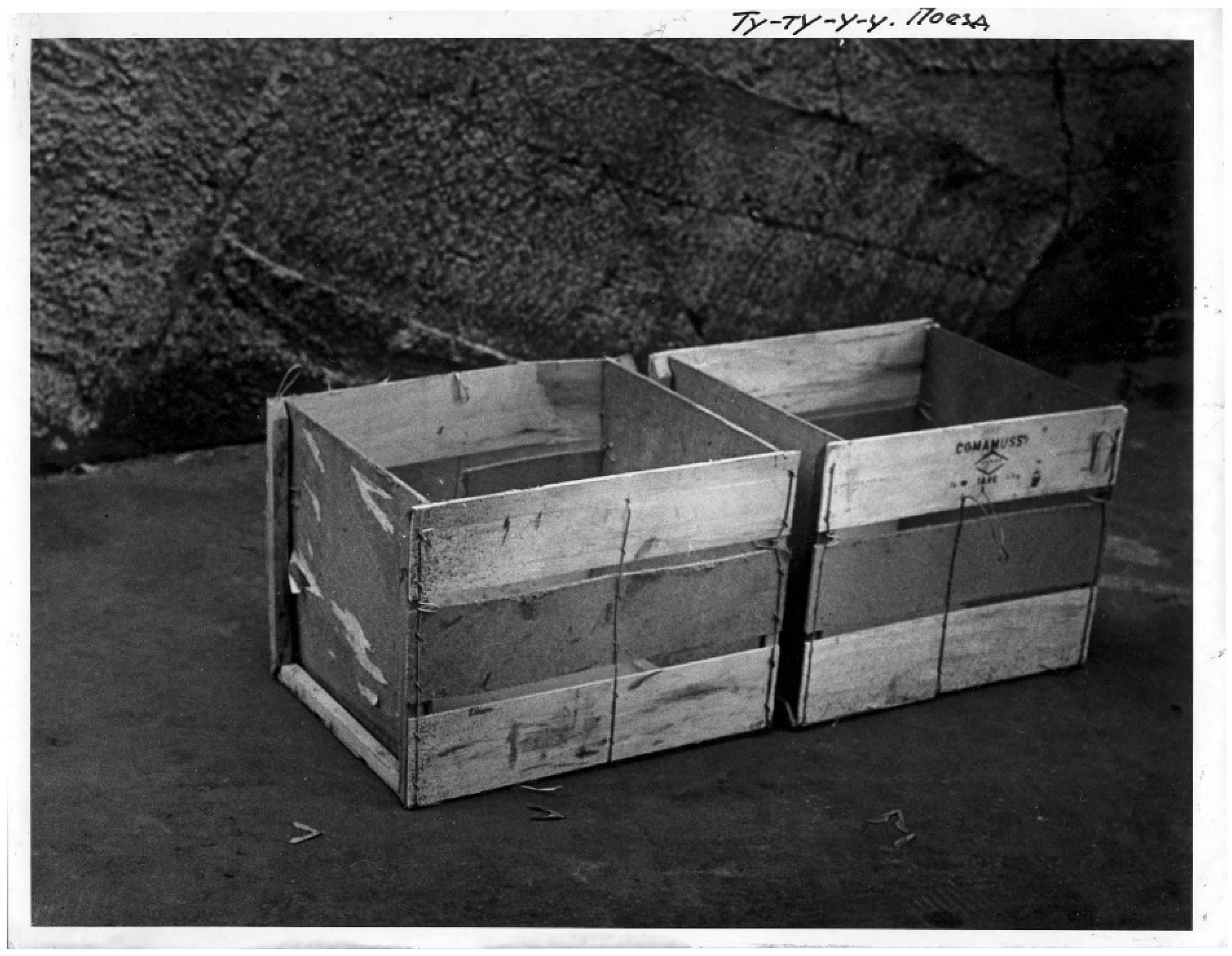

Skersis 2008b, p. 15), draws a slightly different conclusion, however. His black-and-white 1979 photographic series featuring two simple wooden vegetable crates testifies to Skersis’s fascination with the displacement of objects from one semantic field to another, and the unexpected impact of the series relies almost entirely on the humorous mismatch between the various titles of individual works in the series and the primitive materiality of the stark images depicted there. As Skersis notes, the objects are simple “containers for holding items or storing or moving things around. But as soon as we call them by a different name, they transform into something else completely”.

26 Although all the works in the series employ the same two rough wooden crates, the changing titles and the crates’ relative placement in the photographs occasion the appearance of “meaningful transformations that were not obvious at first”.

27 Those “meaningful” differences depend precisely on our perception of the incongruity of the rough, late-Soviet, material substrate and its alleged description, an inconsistency further heightened by the cultural differences and political divisions that separated these artists from their colleagues around the world.

The crates—crude, impoverished, authentic, humble, honest—appear as the main protagonists in

You’re President. I’m President (

Ty President. Ia President) (

Figure 8),

Choo-choo train (

Tu-tu-u-u. Poezd) (

Figure 9),

Peekaboo, Sweetie (

Ku-ku, Pupsik), and others in the series. In

Chair Wrapped in Chairs (

Stul zavernutyi stuliami), another work from 1979, Skersis again makes a point of materiality by exploring what he calls the “interference” of influence from both Kosuth and Christo (

Figure 10).

28 The resulting homage emerges as uniquely late-Soviet in its absurd, brutal, inconvenient, laughable (in)consistency. Skersis’s 1980 work

Chair. Photograph of a Chair. Definition of a Chair extended this creative dialogue even further by substituting three blank pieces of paper for Kosuth’s original chair, photograph, and definition. By including the work in the first volume of the famous MANI archive Skersis made it generally available to “friends and acquaintances and even strangers” (

Danilova and Kuprina-Lyakhovich 2017, p. 236).

29 Far from being irrelevant or redundant, the work’s material content, visual depiction, and characterization are now essential to the meaning of the collaborative work, contingent on individual contributions and shared interpretation.

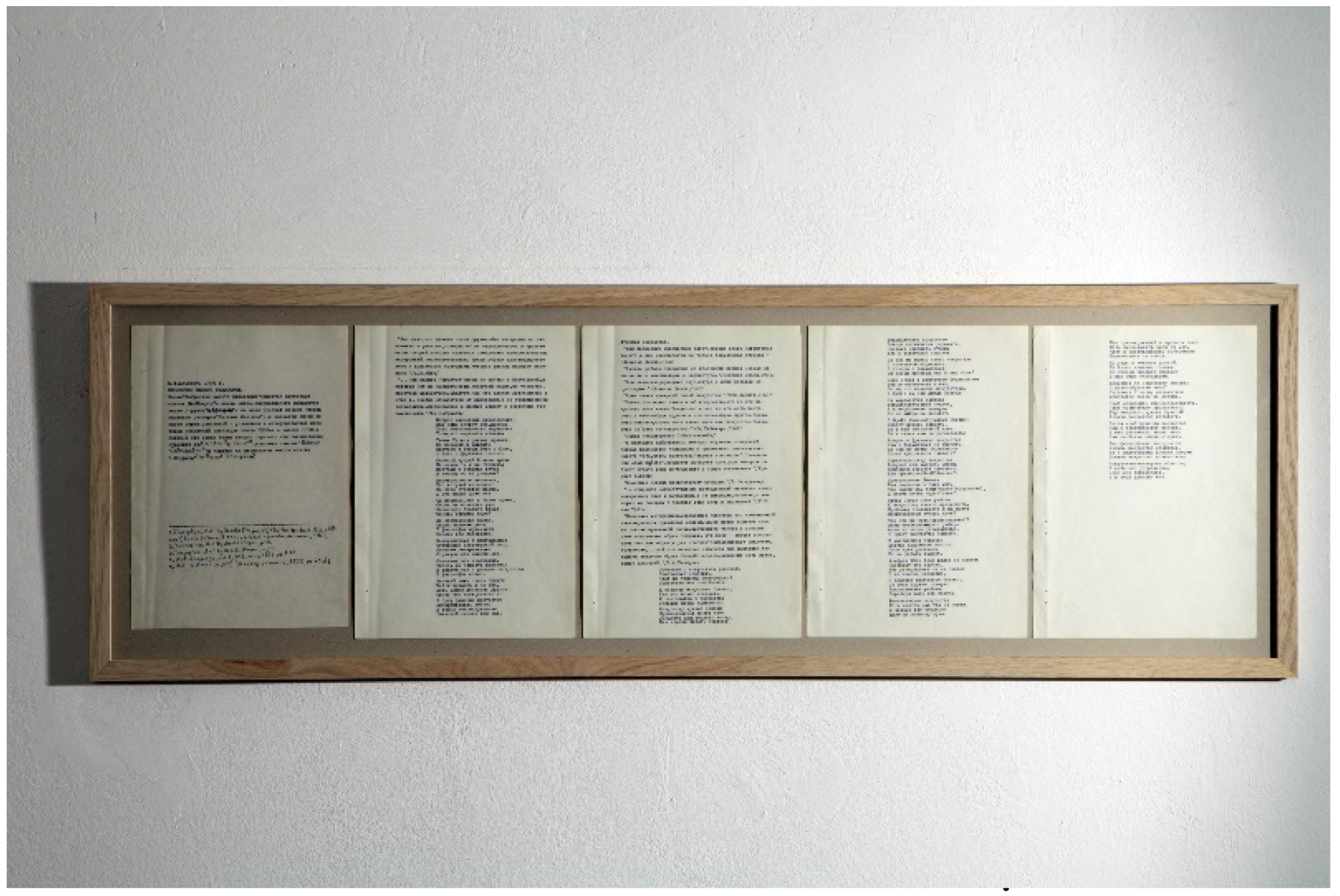

At the same time that Skersis was engaged in this extended dialogue with Kosuth, his friend and colleague Yuri Albert was creating a series of textual works to explore related problems of representation and meaning in art. Albert had been interested in work by Art & Language artists since his first encounter with it as a young art student while visiting the studio of Komar and Melamid, and one of his own early works involved a translation of Kosuth’s article “Art Instead of Philosophy” into Russian (

Figure 11). His interest in materiality and its connection to the artistic process is on full display in his engagement with the Kosuth text, which he presents not as a standard translation from English to Russian but as a poem. Equally unexpected is the fact that Albert bases his interpretation of Kosuth’s work on the Onegin sonnet, one of the most demanding and still most recognizable Russian verse forms. Created by Alexander Pushkin for his masterpiece, the “novel in verse”

Eugene Onegin, the Onegin stanza is uniformly admired by poetry lovers, as is the sparkling original itself, renowned for its wit, multilingual puns, effervescent rhythm and rhyme scheme, and encyclopedic narrative of early nineteenth-century Russian life.

The Onegin stanza is a decidedly unorthodox form to adopt for the first in a series of works Albert dedicated to the “mastery and interpretation of certain positions taken by the avant-garde of the end of the 1960s and the beginning of the 1970s”.

30 His decision to employ the complicated poetic form to explore one of Kosuth’s most anti-material pieces, however, is an early example of his committed investment in carefully rendered texts, physical labor, and directly manifested materiality as part of his artistic process. The effort of exploring Kosuth’s prose was itself a painstaking and time-consuming process, which he was able to complete only thanks to a collaboration with Nadezhda Stolpovskaya, who remembers devoting months at a time to the unavoidably laborious translation of such works.

31 Conveying Kosuth’s abstract thoughts in a strict rhythm and rhyme scheme in Russian and preparing the complicated typescript required considerable additional time and effort. Yet such meticulous work with material was clearly essential to both artists’ understanding of practice, as the other pieces in Albert’s series—translations of excerpts from Terry Atkinson, Bernar Venet, and Robert Morris—demonstrate. Each of the other translations is presented in prose, but they are carefully typed and prepared for exhibition along with the conscientiously prepared, handwritten drafts. Such textured and deeply personal investment in the artistic process results in the artist’s intense engagement with his material, almost against common sense and his own anti-material wishes, yet such embodied performance is crucial to his work too. In a pattern that would reoccur repeatedly over his career, Albert chooses to express his conceptual discoveries in carefully rendered, highly individualized, and often deeply inconvenient fashion, as though the meaning of each work depends on his commitment to the assiduous rendering and performance of it.

Commentary from the late 1970s by Stolpovskaya makes it obvious that concepts of accessibility and materiality are essential in her richly textured works as well. In unpublished remarks from the time, she offers a clear rejection of the “traditional interpretation of the work of art as devoid of any kind of materiality [or] functional proximity to everyday, utilitarian objects”. In customary understanding, she notes, the supposed autonomous aesthetic artwork “existed as something independent of real measures of time”. Convinced they were creating eternal works of art, artists preferred “durable” (

dolgovechnye) materials. In such a hierarchy, Stolpovskaya continues, works on paper occupy a special position since they are traditional in form but executed on “short-lived” material more common in everyday life than in the ethereal world of high art. Working against that tradition, however, Stolpovskaya uses the long-established materials of pen and paper to underline their “untraditional” qualities. Insisting that her works not only “can but should be touched”, the artist insists that perception of them, “like perception of any action (

aktsiia) …unfolds over time” with an “active role” played by the spectator. “My works exist in real time and are subject to it”, Stolpovskaya notes. “They yellow and fade. Their edges get torn. They are not ‘unique, unrepeatable creations.’ Thanks to simple technology, they can be remade. And that copy, like all to follow, will have the same significance as the first”.

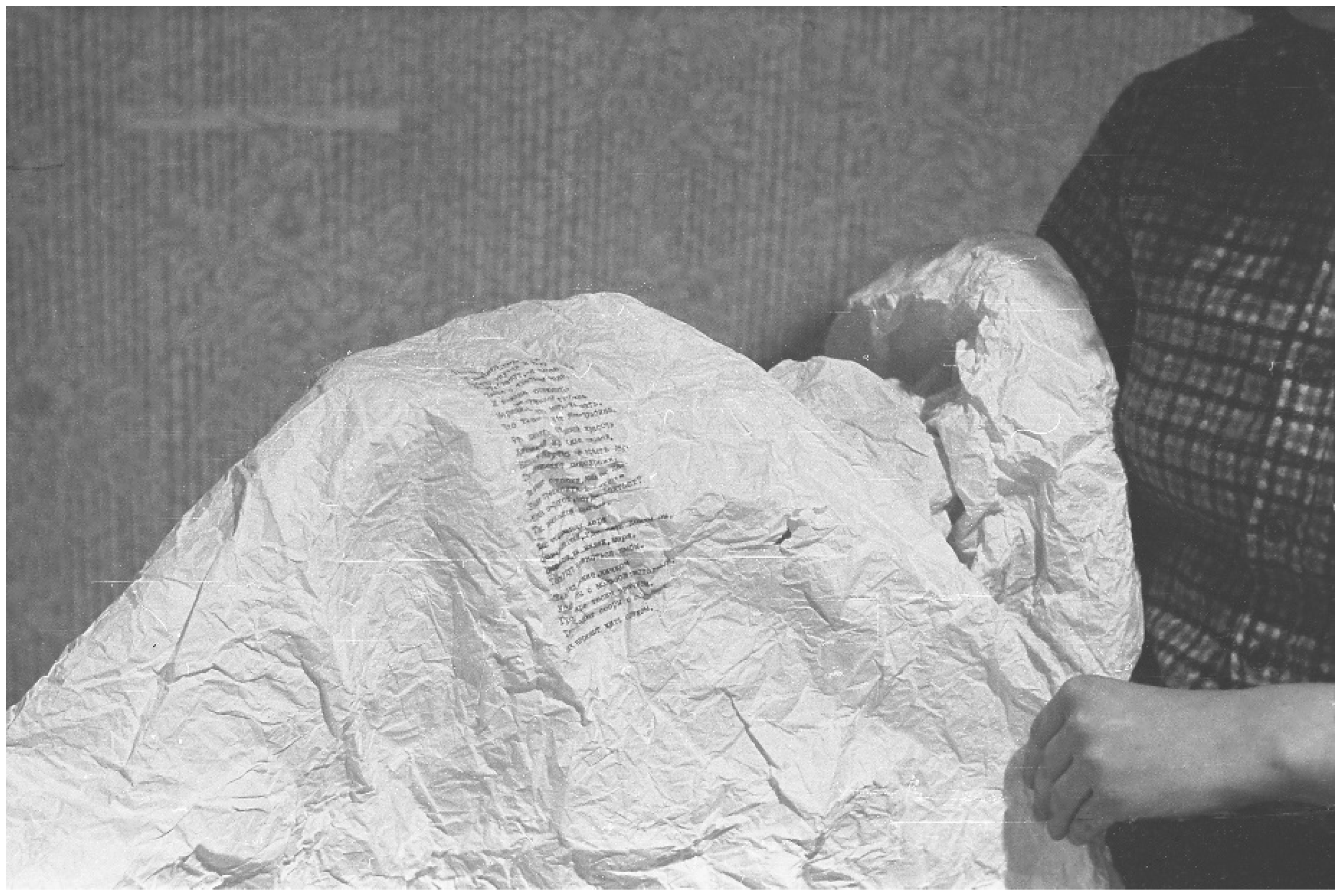

32 Stolpovskaya’s insistence on the active participation of the spectator is particularly obvious with tactile works such as

A Poem by Boris Pasternak (

Stikhotvorenie B. Pasternaka) from 1978–79 (

Figure 12), where the meaning of the artwork and the Pasternak poem it references are revealed only when the paper object is removed from its envelope and gradually unfolded.

33By making her work touchable and the artistic act approachable, Stolpovskaya helped to relieve art itself of its pathos, freeing both the activity and the individual from the burdens of mystery and heroics, but nevertheless insisting on the importance of embodied engagement in the processes of the everyday artistic endeavor. This was precisely the intent of Vadim Zakharov’s early works, especially his very first artistic endeavor,

An Exchange of Information with the Sun (

Obmen informatsiei s Solntsem) from 1978 (

Figure 13). The work is elegant in its simplicity: the artist, a nineteen-year-old student in the Moscow Pedagogical Institute at the time, documents his entry into the creative world by firmly impressing his own thumbprint on a small hand mirror before angling the mirror to catch the sun’s rays. Like many other early works by Zakharov, the gesture is self-affirming and bold, announcing the artist’s arrival on the artistic scene with unalloyed certainty. The brashness of the announcement is tempered, however, by the artist’s location in a winter landscape of late-Soviet prefabricated construction, returning Zakharov’s interstellar communication to the prosaic earthly environment of Brezhnev’s Moscow.

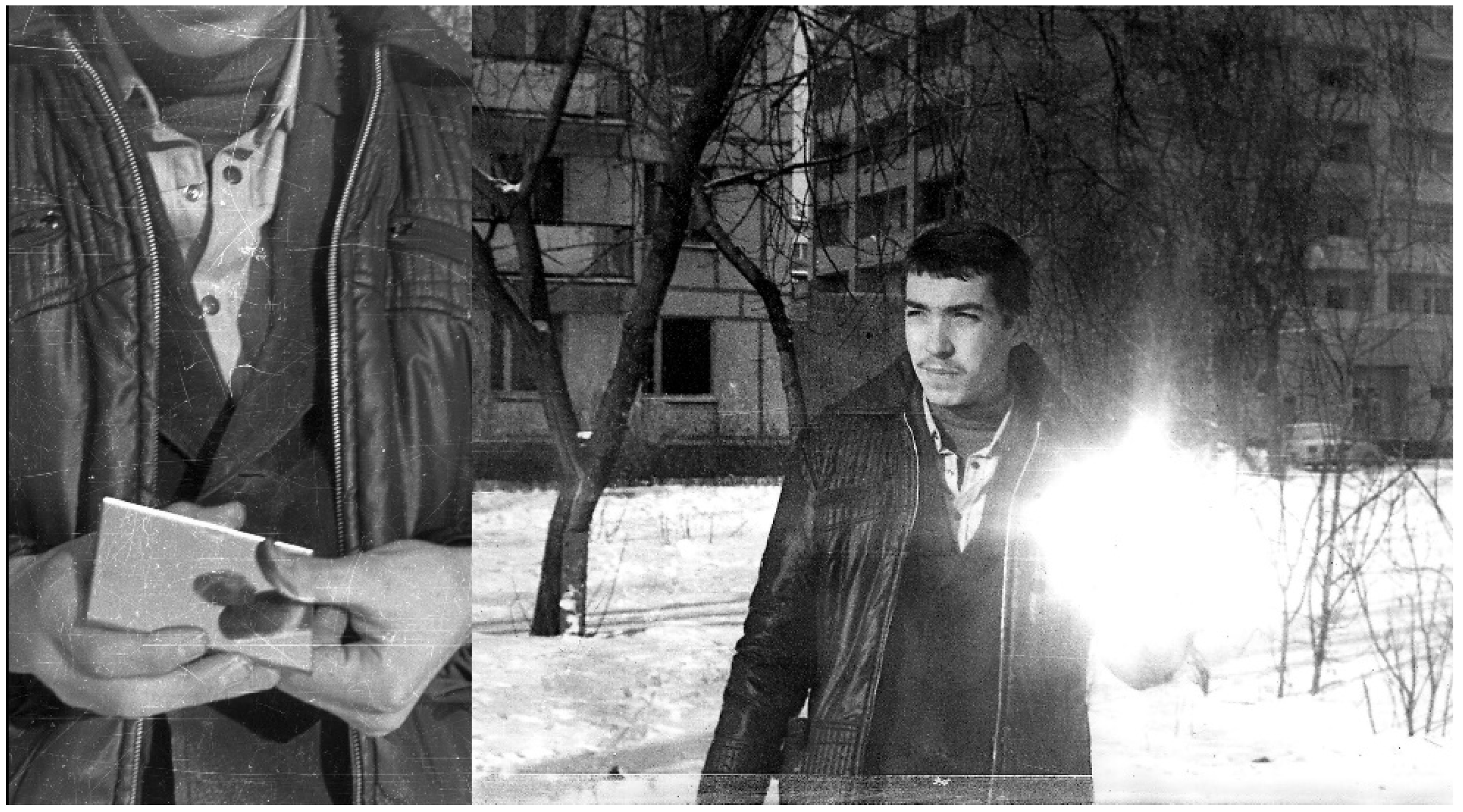

That same devotion to process, personal investment, and focus on materiality was, in fact, part of Yuri Albert’s debut work,

Y. F. Albert gives his entire share of warmth to others (

Iu. F. Albert vse vydeliaemoe im teplo otdaet liudiam) from 1978 (

Figure 14). The text for this early performance work consisted of the single declarative sentence of the title, printed in black capital letters on a white signboard approximately one foot wide and two feet long. Albert hung the board around his neck and carried it around an artistic gathering at the studio of artist Mikhail Odnoralov while shaking spectators’ hands in what he calls an “action” (

aktsiia) and a “kind of performance” (

kak by performans). His pointed demonstration of the awkward sign and his embodied gesture of generosity served as the gift to which the sign alludes.

34 Tellingly, the artist does not address his “warmth” only to fellow artists at the studio or to that traditional Soviet audience, the folk (

narod). Just as the Nest did with

Communication Tube, Albert calibrates his target to a larger and more inclusive audience instead, that of the ubiquitous, democratic, inclusive “people” (

liudi). Albert’s first action thus underlines the parameters of these artists’ creative activity: concrete, accessible, direct, and broadly participatory. As with his work

Household Help (

Pomoshch’ po khoziastvu) from 1979–1981,

35 this work also focuses on process, practice, and everyday existence to make its point (

Figure 15).

Albert’s complicated 1980 reworking of the Kosuth-Skersis dialogue plays with concepts both those artists had invoked. Albert’s photographic work

Chair on Clay Legs, Two Chairs (V. Skersis) (

Stul na glinianykh nogakh, Dva stula [V. Skersis]) (

Figure 16) from 1980 alludes to and continues the work of both Kosuth and Skersis, making the Biblical metaphor that the gods are fallible a tactile reality. Albert’s chair returns the concept of “chair” to its origin as a physical object, as he plays simultaneously with notions of artistic influence, loyalty, and supposed betrayal. The Russian idiom “to sit on two chairs” refers to an individual who tries to hold two mutually contradictory opinions in the hope of benefiting from both positions. Albert’s bold adoption of that very position indicates his arrival as an artist, his belief in the modular nature of art investigation, and his acknowledgment of the role both personal investment and co-authorship play in every work of art. Rather than disguise the appropriated core at the center of all artistic endeavor, Albert highlights it, making his assumption of a metaphorical seat at the artistic table both comfortable and temporary. This explains his dual insistence that the focus of all his work is art alone and his equally hardheaded conviction that the individual work is less important than the connections artists make with other like-minded researchers.

Albert expands on that notion in his open-ended

Autoseries, an extended set of textual works begun in 1979. The series consists of short, typed statements originally conceived as conceptual works to be signed, framed, and exhibited under glass. Spectators would then “complete” these texts by imagining the artworks the artist describes. Yet these pieces evolved beyond their intended role as classically conceptual texts when they appeared out of context as commentary on work by Albert generally.

36 Albert worried that such a shift would deprive them of their status as conceptual works of art in their own right, but it does not, of course: their ability to move seamlessly from work to commentary to work establishes them definitively as postmodern texts. It is precisely such works and Albert’s studied production of them that help locate the artist in the pantheon of modern art. As he notes in the 1981

Autoseries II, “Art has no permanent features: its unity and continuous development are the result of the continuity of ties” that unite “traditions, influences, analogies, associations, contrasts, imitations, and so on” (

Figure 17). Proceeding with a model of art that emerges from “three-dimensional space”, Albert imagines a map of sorts, on which individual artworks are the constantly shifting points of the compass. These individual works are connected by the “multiplicity of lines” representing that complex of influences, Albert continues, and his goal is to “connect those lines without leaving any [fixed] points” of his own. To attempt that feat, he creates works that incorporate real and immediate yet decidedly temporal gestures. Thus

Autoseries I imagines an artist who plans to undertake serious research in his works, but “never brings the concept to a conclusion”, and insists that “fundamental to my work is that art interests me greatly” (

Figure 18).

Autoseries II refers pointedly only to Albert’s “latest works”.

Autoseries III from 1984–1985 (

Figure 19) conceptualizes a work that is “not mine” but nevertheless“ does not violate the structure called ‘The Art of Y. Albert.’ ” Such works diverge significantly from the

personazhnost’ that Victor Tupitsyn and others identify as a characteristic of Moscow conceptualism. Tupitsyn argues that “the camouflaging of the authorial ‘I’ became […] rather typical for Moscow communal conceptualism” (

Tupitsyn 2009, p. 60), but Albert’s goal is investigation rather than camouflage, and the records he produces of those experiments exist as valid, concrete, material reflections of his continuing artistic evolution.

Collaboration and materiality play significant roles in

Eight Assignments for N. Stolpovskaia (

Vosem’ zadanii N. Stolpovskoi), a work Albert created in 1980–1981 with the help of Stolpovskaya (

Figure 20). Both concepts are complicated here by the fact that this seeming co-authorship involves a strict division of labor, Albert assuming a dual role as “influence” and “art critic” as he assigns eight creative tasks for Stolpovskaya to complete. In a gesture he categorizes as an attempt to impact her work and determine the boundaries of it by pushing her to overstep those borders, he first presses Stolpovskaya to create an artwork depicting “someone else’s” work (

chuzhaia). Other set tasks involve requests that Stolpovskaya create works done for “mass production” (

tirazhnaia), pieces focused individually on painting or sculpture, and works concentrated on experiments in poetry or textual analysis.

The experiment seems purposefully intended to encourage Stolpovskaya to violate the boundaries of her creative life, but she succeeds in extending them instead, nowhere more elegantly than in her “painting dedicated to the definition of painting”,

Cross-stitched Headscarf (

Vyshityi krestikom platok) from 1980 (

Figure 21).

The painting itself, executed in oil on canvas 80 × 80 cm square, manages to contribute to several artistic traditions simultaneously. Most obvious is the role the work seems to adopt as decorative handiwork, like that done for centuries by Russian women. Using a traditional color palette of black and red, Stolpovskaya recreates a cross-stitch pattern classic to embroidery of the region, featuring a cross in the center of the “cloth” that is repeated in a decorative border around the edge of the canvas. Scrupulously reproduced, the traditional pattern uses a feminine vernacular that knowingly references the role of the woman artist and the traditional genres open to her. But Stolpovskaya’s creative use of the vernacular establishes her work comfortably in that tradition but nevertheless overturning it quietly: by using traditional motifs in her “painting to define painting”, Stolpovskaya makes the yawning difference between traditional modes of expression and her own radical reconfiguration of art unmistakable.

As she wields paint to mimic the supposedly more womanly arts, Stolpovskaya establishes both her mastery of the full range of contemporary and traditional media and her simultaneously easy claim of and indifference to solo authorship.

37 As such, Stolpovskaya’s painted canvas participates assuredly in the tradition of trompe l’oeil as a technique to establish artistic dominance. Stolpovskaya references this mimetic tradition in her “painting”, a perfectly executed swatch of apparent embroidery that is set to fool modern-day Zeuxis and Parrhasius into thinking that she accepts the restrictions set for her and believes in the need to overcome them to prove her worthiness. Her emphatic rejection of both limitations and the need for dominance suggests why Stolpovskaya has chosen a “white square” for her work rather than the rectangular shape typical for these embroidered samplers. The classic

rushnik, or ritual cloth, would traditionally follow a girl from adolescence and engagement through marriage and final funeral rites. Stolpovskaya’s reinterpretation of the traditional craft suggests her intention to analyze such historical precedents and rework them for a modern context. The work is unquestionably Stolpovskaya’s own, but her deft allusions to both avant-garde innovation and time-honored tradition renders the question of proprietorship, appropriation, even influence per se largely irrelevant.

Stolpovskaya’s handling of the assignment to produce a work of poetry results in her equally sure-footed

Poem (

Stikhotvorenie) (

Figure 22). Noting later that “with every one of their works”, Albert, Skersis, and Zakharov had “hypothesized an answer to the question ‘What is Art?”,

38 she engages easily with that same inquiry, answering it on her own terms. Her response to Albert’s request is phrased, as always, as an ongoing process that engages spectators and leaves final reactions to them. Thus, for the assignment to produce a work of verse, she creates a collection of small glass globes that comes with instructions: “About this work I want to say only that the globes painted green are stressed syllables, while the unpainted globes are unstressed”. With this small gesture, Stolpovskaya again manages to expand, rather than violate, the boundaries of her own art practice by opening the work of art to spectators for direct tactile, auditory, and intellectual engagement on their own terms.

Charged in the eighth “assignment” to overstep her own approach by creating an “analytical work”, she feigns confusion before announcing that her participation in the project itself is that very investigative process. In

Analytical Work (

Analiticheskaia rabota (

Figure 23), she thus declares “This text is not the analytical work”, but “all the works themselves”. As she mentions in an interview with Vadim Zakharov, Stolpovskaya notes that “the spectator is very important to me and my works”, including physical contact with the artworks themselves. Noting her interest in work by Walter de Maria, Bruce Nauman, Robert Morris, Richard Serra, and others, she emphasizes the role of the viewer—or reader—of Nauman’s monitors in particular, arguing that “without the spectator, the work doesn’t even exist”. Eschewing any complicated “subtext” to her works, “most likely as a reaction to the Moscow environment”, Stolpovskaya concludes that she considers a work “successful if the structure of the work transmits the structure of the depicted object”. For that, she notes, it is essential for the viewer to “open the work fully, to experience its materiality”.

39 That helps explain her focus on the mundane and common, on processes of everyday life accessible to everyone who takes the time to engage with them.

Albert combines a similar interest in materiality and open accessibility in his series

Continuation of Others’ Series from 1980 and 1981. This exercise again makes a virtue of his devotion to materiality by allowing him to focus on process as he engages stylistically with the work of artists both in the Soviet Union and outside its borders. The series includes works that echo concepts from Joseph Beuys, Carl Andre, and others, documenting, for example, work by Roy Lichtenstein that Albert would develop further at the end of the decade. Early examples of such outreach expanded on work from artists in Albert’s own circle as well, as he reacted to work by Stolpovskaya, Zakharov, and, as we have seen, Skersis.

Glass with Sour Cream (N. Stolpovskaya) (Stakan so smetanoi [N. Stolpovskaia]), for example, has Albert engaging with paper and acrylic enamel to create an imagined continuation of distinctive graphic work by Stolpovskaya (

Figure 24). Part of the conceptual beauty of this work—and of the series in general—is that spectators of it are unavoidably pressed into service as participants in an extended analysis of the meaning of originality, authorship, and creation. Another reaction to and collaboration with Stolpovskaya involved an efficiently co-authored “work” from 30 December 1981: their signed and dated document hints at a rich and ongoing dialogue to which the artists allude in their otherwise succinct assertion that “this work we made together”. They refuse to belabor the point, however, inserting the signed document into the MANI archive as is, devoid of explanatory material or pictorial embellishment.

40 Such laconicism focuses attention on the collaborative process of art for this branch of Moscow conceptualism: by shifting their teamwork to the end of the sentence, where it assumes pride of place as the most important information in the statement, the artists are able to underline their emphasis on artistic practice and shared endeavor.

Albert engages Zakharov directly in a letter from 30 April 1981 in which he requests that Zakharov conceive of, carry out, and then send him a work to continue that artist’s work

Stimulations, itself a profoundly tactile and collaborative series. The typed letter Albert sends to Zakharov documents Albert’s request and makes it clear that Albert will include whatever work Zakharov produces into his own series. In anticipation of such co-authorship, Albert continues his own textual explorations of the meaning of art in context by imagining a work of art that would hang “between Nadia Stolpovskaya’s

Table Covered with a Tablecloth and Vadim Zakharov’s

Stimulation series”. This, then, is the work that Albert creates by suggestion in his letter to Zakharov (

Figure 25). Its exhibition makes it clear that this curated artistic community, ongoing conversation in and about it, and contextualized meaning are essential to the analytical branch of Moscow conceptualism.

Like

Continuation of Others’ Series, Albert’s numerous anti-self-portraits in his

I Am Not… series demonstrate his attention to and engagement in the materiality of the artistic process. Each work carefully appropriates the style, medium, color scheme, and other features of various well-known artists only to insist that Albert is a different creator altogether. The unexpected effect of these partially appropriated material qualities is a paradoxical insistence on the artist’s irrefutable individuality. Albert’s studied and painstaking performance of the roles he then rejects in the anti-self-portraits serves antithetically to establish him as a significant presence in the art world. The

I am not… series carefully analyzes the many techniques and styles Albert might have adopted, but has not, finally, assumed. He measures each role conscientiously, investigating each model fully before moving to another in a process that is intellectual and analytical but, antithetically, also personalized. His considered deployment of a host of artistic models, any one of which is part of Albert’s artistic conversation, but none of which can sum up the artist in totality, counterintuitively manages to establish the parameters of his activity as an artist. The seemingly paradoxical conclusion that such borrowed material leads to a profoundly personal statement helps to explain Albert’s interest in work by the Russian Formalist writer Yuri Tynianov. Tynianov’s conviction that the application of old forms to serve new functions is one of the most productive ways for art to renew itself is directly applicable to Albert and other analytical conceptualists.

41 For these artists, additional iterations of an idea are acceptable, even welcome, and reengagement or repurposed performance of an earlier work makes perfect artistic sense. As Zakharov notes in a comment from his own collaborative project with Stolpovskaya, “the time for individual struggle [

ryvok] has passed… Now the artist is allowed to use all methods and means”.

42SZ, a partnership between Skersis and Zakharov, continued these artists’ early focus on real life and its material substrate in a number of works intended to elicit the direct participation of spectators acting independently. The SZ series

Self-Defense Courses Against Things (

Zashchita i kursy samooborony ot veshchei) from 1981–1982, for example, engaged spectators in a set of exercises to learn how to defend themselves from objects in the surrounding world (

Figure 26). Combining outreach and humor with a clear recognition of the unfriendly reception late-Soviet reality—and even some colleagues—offered their work, the self-defense courses encouraged artists to return to the real world. The works developed in part from Skersis’s earlier investigations of the anthropomorphization of inanimate objects in a series entitled

In Order to Humanize Objects, We Need Birth Control and Punishment Devices. Since the Soviet system discouraged independent initiatives, including unauthorized courses for self-defense, the SZ series also alluded in passing to the more dangerous aspects of autonomous action in the late-Soviet period. But their attacks on cupboards, doors, tables, and toilets and the clearly facetious “magical spells” (

zaklinaniia) the artists wrote to arm their fellow citizens against such everyday objects aimed less at political power than at the constraints that restricted artistic innovation.

43 In a comment from 1982, Anatoly Zhigalov mentions that exact aspect of SZ work as the group’s most significant contribution, noting “SZ is distinguished by genuine democratism”. Zhigalov particularly notes the “neutrality” of their language and its adequacy to the “environment”, emphasizing that SZ work is accessible to all participants, regardless of their level, professional standing, or previous preparation. Zhigalov identified the Self-Defense Courses, as well as SZ’s 1980 series

Anatomy of Safety Matches (

Anatomiia spichek) as part of a necessary “‘kitchen rebellion’ against [overly spiritual] art”.

44Zhigalov’s own work, done with his co-author and wife Natalia Abalakova, included similar moments of concretized meaning. At an AptArt apartment exhibit, their label on the gas stove (

dukhovka) offered a tangible counterpoint to the exaggerated

dukhovnost’ (spirituality) of older generations, especially when coupled with the neologism—

netlenka, or “imperishables”—over the kitchen sink, used ironically to refer to both immortal works of art and the detritus that ends up in the sink after a meal. Their 1982 work

Black Square (Chernyi kvadrat)—a large plastic bag filled with carbon paper—provided concrete evidence of their ambivalence to the avant-garde inheritance and their rejection of the disembodied, ephemeral, and vague (

Figure 27).

45 Their justly famous

The Chair is Not for You. The Chair is for Everyone (

Stul ne dlia Vas. Stul dlia vsekh), an actual chair that was also exhibited at AptArt with its title keeping would-be users at bay, created vivid longing for the real-world “chairness” of the actual physical object.

For these analytical conceptualists, anxiety over the frequently predicted “end of art” involved less a sense of personal tragedy than it did for many of their Moscow colleagues or their counterparts in the West. In the late-Soviet unofficial art world, the end of “Real Art” (

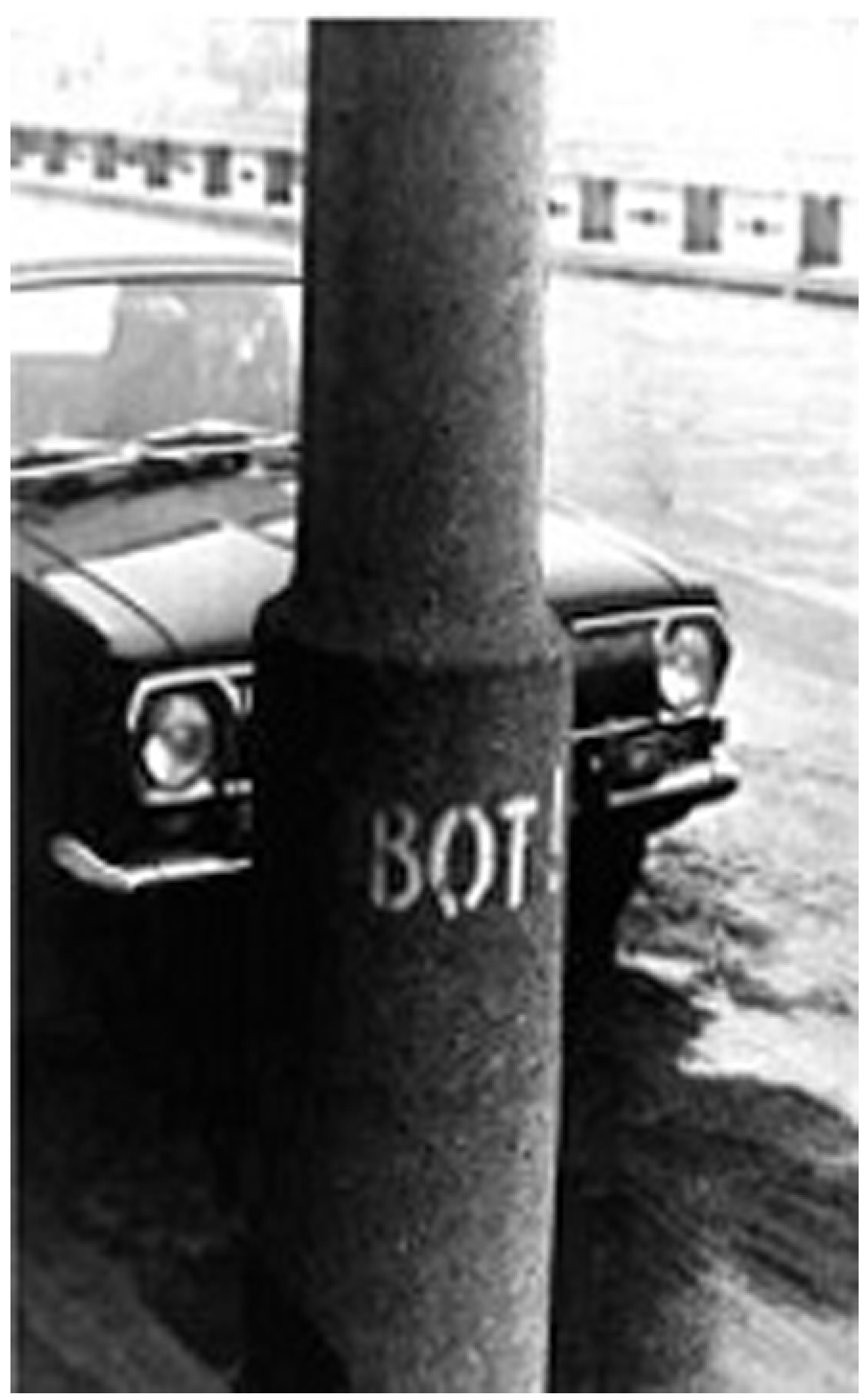

nastoiashchee), to use Albert’s terminology, came with a realization that the artist was just one voice among many clamoring for attention; paint and canvas was just one medium available for authentic artistic expression. Thus, chairs, bags, bodies, and other such objects came to play an increasing important role in their embodied art, linking it to both a nonconformist past and the performative future of Russian actionism. Although Albert’s repeated reference to their current relegation to the category of merely “contemporary art” suggests lingering regret over that state of affairs, these artists embraced their position in the world of materiality and concrete objects in place of an exalted imaginary status apart from everyday existence. Commentators have described the rough, uneven, often unfinished physical nature of these and other works of Moscow conceptualism as an effect of, variously, Soviet “poverty”, the artists’ preferred focus on the ephemeral, or a reflection of their naïve sincerity. At least for this branch of conceptualists, however, the emphasis on tangibility and substance refocused attention on situational, real-time, embodied everyday meaning. By unwrapping certain key metaphors completely, mapping them fully onto the domain of quotidian life, Nest artists and their colleagues succeeded in making language solid and real. By doing so, they were able to direct attention to the compelling texture of art at our very fingertips. Some half a century on from the emergence of Moscow conceptualism and the (re)appearance of Russian performative art, it is time to expand our understanding of the movement as a whole to include such works. These artists and their concrete objects serve as particularly vivid counterexamples to the notion that conceptual art relied solely on the dematerialized, disembodied idea. As the 1980 work

Here! (

Vot!), from SZ’s graffiti series

Inscriptions (

Nadpisi) (

Figure 28) reminds us: art is continually right before us, concrete and real. All we have to do is notice it.