Abstract

The article examines the paintings by Eduard Steinberg, a Soviet non-conformist painter from the 1950s to the 1980s from the standpoint of the plastics of his language. The author focuses on Steinberg’s polemical dialogues with the greatest names in Russian and European avant-garde art, including both common points and disagreements. By analyzing the painter’s texts through the prism of poetics of the invisible and the ontology of traces, the author observes Steinberg’s early art of the 1960s and 1970s as an attempt to create a symbolic language and attach an ideographic status to art. Through simultaneous use of two artistic strategies—mystical and religious symbolism, coupled with metageometry Steinberg arrives at optical formalism and spectator dialectics, vying to see the invisible and record the polysemantic nature of the symbolic sign. The article analyzes the influence Vladimir Veisberg and his “invisible painting” had on Steinberg, including the “white on white” style, as well as Giorgio Morandi’s still-life vision of metaphysical painting. The author believes that by relying on analogies and reminiscences, Steinberg refers his audience to his predecessors and joins them in an intertextual dialogue. A special place here belongs to Kazimir Malevich with his radicalism, his trend towards metasymbolism and the language of the basic forms—the circle, square and cross. All of these are close to Steinberg’s geometric plastics of the 1970s and 1980s. Staying true to the pure forms of Suprematism, Steinberg builds up an aesthetics of the geometric forms of his own, where abstract art comes together with the ontological progress towards God. The Countryside series (1985–1987) shows influence of Кazimir Malevich’s Peasant Cycle, some principles of icon painting and Neo-Primitivist art.

1. Introduction

A lot has been written on Eduard (Edik) Steinberg both in Russia and outside it, including marvellous essays and insightful research articles. Compilations of his letters and memoirs have been published, as well as his numerous interviews. Given the multitude of researcher opinions and reflections, there is still a large, uncovered space of Steinberg’s marginalia—a kind of margin notes which appear as unverified universals, such as the sign/symbol, meaning/non-meaning, the visible/invisible, the sacred and profane. Steinberg’s plastic language borrowed from and appropriated traditions of both Russian and European Modernism, and in search of new modes of expression arrived at a novel visual optic. One way to do it was by entering into polemical conversations with Russian icon art, with mystical ideas of Russian Symbolism, and the other, by setting up a new geometrical lexicon of Suprematism and “optical neoplasticity”1 of contemporary art. The illusion of laconic simplicity of Steinberg’s art often devalues the nature of his plastic expression, and the causal relationships and intertextual parallels are, thus, annulled and ignored. This is probably why the existing body of literature on Steinberg lacks semiotic analysis of his pictorial texts and does not attempt to decipher the meanings present therein, nor feature a detailed study of the morphology and cultural semantics of his art. At the first glance, the plastic symbols of his object-free art seem a manifestation of Steinberg’s unlimited subjectivity. We then discover a plethora of thriving suggestive forms and imagery in his works, and, in search of tools to help us illustrate the work of the artist’s abstract imagination, we have to turn to various fields of the humanities, such as philosophy, religious studies, social sciences, semiotics and arts studies proper, thus, transcending the boundaries of separate disciplines. It is this integrative approach that will help us expand the horizons of how we see Steinberg’s art, discern the traces of the corpus of previous artistic texts therein, as well as actualize the visible and invisible forms, as well as their interaction and juxtaposition. Steinberg’s art teaches us to see new trajectories of how abstract forms move in space, and a new energy of representing the invisible. The creative capability of visual art gives space to more than just the aesthetic and the mystical, it also covers the social function of art. Steinberg’s iconography gives preference to the link between the image and meditative contemplation and empathy, which can be traced throughout the structure of his visual formulas. His art is a representation of an optical experience which arises from congested images created as signs in the space of microcosm and a unique temporality. Our methodology of studying Steinberg’s art is also based on the latest trends in visual studies and the poststructuralism of Jacques Derrida. Without claiming complete coverage, we would like to examine Steinberg’s poetics through the prism of the metaphysics of presence and the “anthology of traces” (Barthes 2020, p. 65) as crucially important visual codes which set the textual trajectory and the semantic of descriptions in the painter’s work.

The concept of ‘trace’ first appeared as a revision of classical metaphysics and its notes in Jacques Derrida’s post-modernist classic “Of grammatology” (1967).2 Derrida links ‘trace’ to the ‘origin’ of sense:

The trace is in fact the absolute origin of sense in general. Which amounts to saying once again that there is no absolute origin of sense in general. The trace is the differance which opens appearance [1’ apparaitre] and signification. Articulating the living upon the nonliving in general, origin of all repetition, origin of ideality, the trace is not more ideal than real, not more intelligible than sensible, not more a transparent signification than an opaque energy and no concept of metaphysics can describe it.(Derrida 1997, p. 65)

The trace as a presence and an act of difference is a phenomenon of graphic writing, but it is also a more global mechanism of the existence of culture and a way to learn the cultural and historical heritage. The trace in Derrida is linked to the multitude definitions of “the metaphysics of presence in the form of ideality” (Derrida 1973, p. 10). The self-erasing trace as a form of both presence and non-presence belongs to both culture and transcendental conscience. According to Derrida, this self-erasure reveals the trace’s double reference, both annulling and representative correlation with another trace. While marking the key phenomena of difference, Derrida mentions yet another important notion—reproducing memory as “reproduction of presentation” (Derrida 1973, p. 49). An important role belongs not only to how he defines metaphysical presence, but also by how he observes the signifier and the signified in the whole context of the system of signs. Adding to ““supplement”, “sign”, “writing”, or “trace” a … newly, ahistorical sense, “older” than presence and the system of truth, older than "history”” (Derrida 1973, p. 103), the philosopher distinguishes between “sensible literalness” and the proper metaphor of the “breakup of presence” (Derrida 1973, pp. 103–4). Extrapolating this model now into the field of the phenomenology of language, Derrida brings presence and trace to work for the form and semantics of text. By seeing the text as a fabric and the language’s ‘interweaving’ nature (Verwebung) as a form of establishing connection with other threads of experience, Derrida is able to state the following:

The interweaving (Verwebung) of language, of what is purely linguistic in language with the other threads of experience, constitutes one fabric. The term Verwebung refers to this metaphorical zone. The “strata” are “woven”; their intermixing is such that the warp cannot be distinguished from the woof. If the stratum of logos were simply founded, one could set it aside so as to let the underlying substratum of nonexpressive acts and contents appear beneath it. But since this superstructure reacts in an essential and decisive way upon the Unterschicht [substratum], one is obliged, from the start of the description, to associate the geological metaphor with a properly textual metaphor, for fabric or textile means text. Verweben here means texere. The discursive refers to the nondiscursive, the linguistic "stratum" is intermixed with the prelinguistic "stratum" according to the controlled system of a sort of text. <…> In the spinning-out of language the discursive woof is rendered unrecognizable as a woof and takes the place of a warp; it takes the place of something that has not really preceded it. This texture is all the more inextricable in that it is wholly signifying: the nonexpressive threads are not without signification.(Derrida 1973, pp. 111–12)

There is yet another important point to make. In his discussion of writing as a form of language’s existence which always leaves traces, Jacques Derrida explains his onthological formula of multiple distinctions, references and erasures as signs which arise through oppositions and differences. Semantic scattering of meanings and the interplay between traces is Derrida’s main focus. He is attracted by how the fabric of text is put together, since everything is textual. This endless vista of interconnected signs and their meanings, authors facing and rethinking cultural traditions is what happens when a text is constructed. We have no proof that Steinberg ever read Derrida’s works, but they have the common background of 1960s as a period aimed at social and creative transformation. Steinberg observed art as a symbolic and metaphorical language. He was a master of analogies which gave signs a new semantics; he directly addressed the cultural memory and elegantly summed up the lived experience. Lifting the curtain of the transcendent, Steinberg invites the spectator to enjoy the deciphering of cross-references and the decoding of the unrevealed traces. Both memory and the elusive optics in his work bring order into what we see and give access to a wide sphere of its semantics.

The constituted sense of Steinberg’s texts is multi-layered. The “interweaving” of signified descriptions that Derrida noted, leads us to search for more layers hidden within the textual space of Steinberg’s art. Similar to reflections in the mirror, they reveal their capability only when found, and what they contain may range from a virgin pre-text to visible traces and imprints of cultural memory. The artist’s text, ‘woven’ from many senses and meanings into the historical and contemporary cultural context, produces an interweaving, and this interweaving as “mirrored writing” (Derrida 1973, p. 113), finds the semi-erased signs and hidden layers of symbolic patterns. In his contemplation of contemporary art, a French philosopher Thierry de Duve was quite right to state that any work of art is “destined to be a sign” (de Duve 2014, p. 31), while the “hum of language” (p. 32) и and the flutter of meanings produce “generate polysemy and ambiguity, noise and dispersion” (p. 32). We will take a deeper look at how analogies, reminiscences, hints and reference help Steinberg add markers to acts of artistic expression. We believe that producing new meanings as a marker of the author’s style owes a lot to the special nature of the artist’s polycode text where the allusive narrativity appears on various levels and might be discovered and deciphered by addressing a previous artistic experience. The artist as an “operator of gestures” (Barthes 2020, p. 54) scans the see-through text to find the meaning (which is not always possible to do) and broadcasts it further as a multitude of modalities, thereby entering an intertextual and polemical dialogue with both previous and contemporary texts of culture and art.

2. The Optical Non-Obvious: On the Way towards a Language of Symbols

In Evgeny Shiffers’ earliest article on Steinberg and his work (1973), the religious thinker and theologian reflects on the ideographic language of the artist whose paintings are “generated by symbolic models” (Schiffers 2019, p. 14). Using the works of Pavel Florensky, Sergey Solovyov and religious mystics as a point of reference, Shiffers traced the connection between the works of Steinberg and the metaphysical symbols of Eternal Being and of the Church (therefore, the paintings are metaphysical), with the manifestly visible world and “the invisible ideas taking flesh” (p. 15). Hence, the picture is an act of “uttering the comprehensible” and a “symbolic creative model” (p. 22). Staying far from the semiotics of art, Schiffers outlined several important ways to study Steinberg’s art. First of all, the ideographic status of Steinberg’s paintings gives them a kind of universal language capable of capturing abstract concepts as symbolic signs. Secondly, Steinberg’s religious and philosophical quests are both permeated with the desire “to develop a modern universal symbolic language” (Chudetskaia 2020, p. 410). Thirdly, Shiffers discovered crucial symbolic patterns that permeate all of Steinberg’s work, including the sphere, cube, pyramid, horizontal and vertical lines, the bird and the cross (Schiffers 2019, p. 14). Regarding the symbols of symbolic “top” and “bottom”, Shiffers observes to have been designed as a bridge between earth and sky, the profane and sacred, hence, the symbolic model of space and time includes the artist’s ideographic alphabet of “water, fire, dove, light, and sphere” (p. 19). A personal meeting with Schiffers helped Steinberg to further his search for a new plastic language rooted in mystical metaphysics and Symbolist worldview. Steinberg himself has repeatedly spoken about the influence the Silver Age and Symbolism had on him, in particular V. Borisov-Musatov and V. Kandinsky (whom he also considered a Symbolist) and stated that he himself was “a Symbolist in point of fact” (Steinberg 2015, p. 236). In a conversation with Yevgraf Konchin, the artist thus described the two artistic strategies that influenced his work:

I haven’t actually discovered anything new, I just gave the Russian avant-garde art a new perspective. What kind of perspective? Rather, a religious one. I based my spatial geometrical structures on old catacomb mural paintings and, of course, on iconography. My small merit is that I have gave the avant-garde a bit of a turn. But on the other hand, I am furthering the traditions of Russian Symbolism in my works, the Symbolism of Boris Musatov. The Mir Iskusstva also approached it, and so did Kandinsky. He is a pure Symbolist in my opinion. The internal concept of my works thus rest on the synthesis of the mystical ideas of 1910’s Russian Symbolism and the plastic solutions offered by Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism.(Steinberg 2015, p. 211)

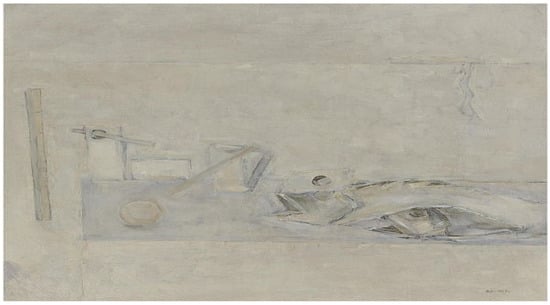

The symbolic structure of Steinberg’s paintings is arranged into a complex system of signs and symbols that are quite difficult to decode. This is further complicated by the fact that the artist never offered interpretations of his texts, and was generally irritated by such attempts. However, the hidden contexts of his works have clear references to Christian iconography and catacomb painting, especially in his early period of the 1960s. For example, in A Composition with Fish (Figure 1), 1967, we encounter the eponymous mythologem associatively linked to the acronym ‘ΊΧθΥΣ,’ which comprises the Saviour’s name and the earliest Christian creed.3 In his numerous interviews, Steinberg frequently admitted the influence of Early Christian catacomb art. In Figure 2, we might probably see a reference to a fresco in the catacombs of St. Callistus church in Rome (Figure 2)—a fish bearing a basket of bread. We see how simple forms codify sacred symbols and ideologemes of signs referring us back to Christian symbolism.

Figure 1.

Eduard Steinberg. A Composition with Fish. Oils on canvas, 1967. 100 * 100. Private collection, USA. https://artinvestment.ru/auctions/2244/records.html?work_id=850820 (accessed on 16 May 2022).

Figure 2.

Eucharistic Fish and Loaves. A fresco of the catacombs of St. Callistus, Rome. 2nd–4th century CE. https://www.wikiwand.com/ru/ (accessed on 16 May 2022).

Sergey Kuskov claims the signs and symbols in Steinberg’s works get “transformed into pockets of spiritual energy” and reveal “the presence, most commonly unseen, of the Vertical of the World, with the whole array of its symbolic divisions” (Kuskov 2019, p. 55). To see the invisible is the task the artist assumes throughout his work. The optically non-obvious nature of his works provokes a search for the polymorphic text hidden in the deeper layers of his works.4 This particular vision manifests optical formalism, when the visual is dialectically conveyed through mirror imagery of the top and the bottom, the horizontal and the vertical, the sky and the Earth. The dichotomy of the visible/invisible captures two important aspects of Steinberg’s art: the enduring presence of the inexpressible and optical duality. The first option Steinberg associates with the transcendental and with the other reality, which in its turn relies on negative theology (apophaticism), i.e., the doctrine of God in Himself, unattainable and unknowable. To attain it, one must follow the “path of negation”, learning to apprehend that God is beyond space and time, invisible, indescribable and unrecognizable. The inexhaustible fullness of God’s super-being cannot be expressed in human words or concepts, so the artist recognizes the immanent essence of the transcendent Absolute. Steinberg was close to the idea of apophaticism and in no way did it contradict his Orthodox religiosity. In his letter to Malevich, the artist discussed his language of geometry as follows: “<…> there is a yearning for the truth and for the transcendent, a certain affinity for apophatic theology” (Steinberg 2015, p. 39). He repeatedly confessed in his correspondence that he was a man of faith, and in a response to Martin Hüttel, Steinberg thus stated his belief: “The Lord God helps me, I know it now, and I know it firmly” (p. 52). His faith is coupled with pessimism, for “our time is a God-forsaken time” (p. 133), plagued with a sense of “unyielding existential disaster” (p. 203). He is also convinced that “everyone matches their her own existential space” (p. 202). His personal view of the Absolute and the Infinite, formed largely through a religious worldview and mystical symbolism, found its expression in pure abstraction, “in a line of persons and signs” (p. 123):

The peace of the Absolute is only conceivable through the variability of becoming. In each period of Steinberg’s existential exploration, a certain stylistic or, more precisely, plastic approach to understanding a unified structure of Being dominated hierarchically among the rest. This ideal and fundamentally ineffable object of contemplation, however, could only be relatively pushed from its apophaticism to become somewhat comprehensible by a gradual hierarchical manifestation. Therefore, every period in the artist’s work was and remains a step of this type in this hierarchy.(Kuskov 2019, p. 61)

Steinberg used to repeat in many of his letters that in God, there is no time. Aware of the transience of metaphysical time, the artist hurries to capture the sense of the invisible and hidden, once saying that “It is important to see in a painting what we cannot see” (Steinberg 2015, p. 151). This presence of the invisible in Steinberg is never limited to the multi-layered structure of the canvas. He observed the whole of his art as one huge painting: “I love paintings where the question is asked and they also answer it” (p. 151). While denying narrativity, technology and depiction of everyday life in painting, the artist follows the ambiguity of visual optics when, through temporal work, all anthropomorphism is eliminated. The illusionism of his minimalist works is such that the juxtaposition of the presence and the trace of another text indicates the overcoming of the barrier between one’s own and another’s artistic statement. The “evidence of presence” (Didi-Huberman 2001, p. 53) in Steinberg consists of the play of visible and invisible forms mirroring each other in the transcendental space of the painting. The ways the “new field of the visible” is discovered (Marion 2010, p. 37) have been masterfully traced by the French phenomenologist and theologian Jean Luc Marion:

The true artist participates in the simple mystery of a unique Creation, in the sense that he reproduces nothing-only produces. Or, more precisely, he leads from the invisible into the visible, sometimes by intrusion, a meager reproduction of the visible done by the visible itself: this is what is usually called “creation” <…>. The real picture does not ascend from one visible thing to another, but conjures the visible which has already appeared to multiply and reveal itself with a new radiance. The invisible ascends to the visible and reaches up to it. But the invisible also informs the visible, presenting and prescribing what the visible had so far been ignoring, and thus restoring the balance of power <…>.(p. 62)

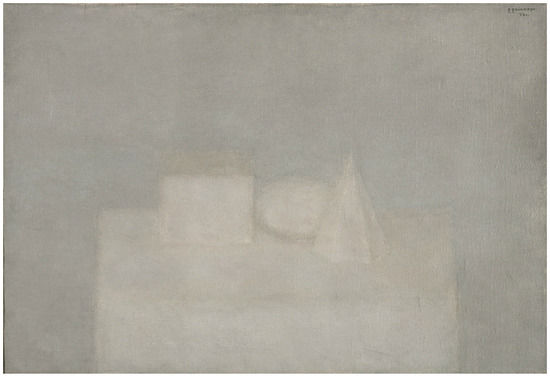

While considering Steinberg’s visual codes and symbolic language, we should focus awhile on his fascination with Vladimir Veisberg’s “invisible painting” (Figure 3), a style of “white on white” that goes back to Malevich’s Suprematism. The artist’s paintings are brought together by half-tones, transparency, and shimmering shades of white. Their subtle immateriality is akin to universal harmony and peace.5 Without doubt, Steinberg is close to Veisberg’s translucent painting and his search for its special tonality and ethereal transparency. He repeatedly singled out Veisberg, together with Krasnopevtsev and Sooster, as his favorite artists from the nonconformist circle. The link between the divine and the unknowable that these artists explored was also important for Steinberg, as was their search for new spatial coordinates and existential formulas. The pictorial parallels are obvious, much similar to the common elements in the plastic language and in the structure of the composition. The space of Veisberg’s paintings is consonant with metaphysical abstraction, with algorithms of signs and a special semantics of meanings firmly embedded.

Figure 3.

Vladimir Veisberg. The cube, sphere and pyramid, 1973. Oils on canvas, 55 * 58. Art4 Museum, Moscow (Igor Markin’s collection). https://www.art4.ru/museum/shteynberg-eduard/ (accessed on 22 May 2022).

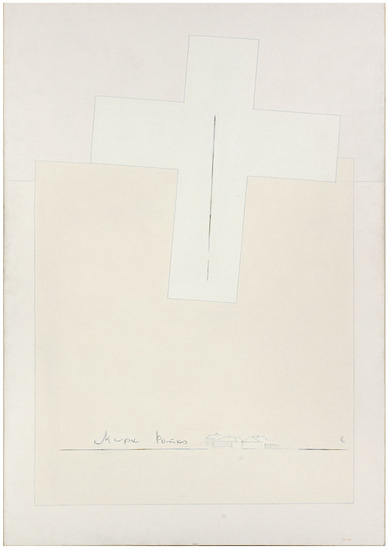

Veisberg’s and Steinberg’s semiotic systems not only share the simplest repeating structures and signs, such as spheres, squares, rectangles, triangles, etc. Their early paintings make use of the technique of grisaille, i.e., creating a painting by using different shades and tones of the same color: Veisberg’s choice was the gray-white, and Steinberg’s was milky beige, sometimes diluted with blue (Figure 4). Their monochrome painting, imitating the plastics and relief of a sculpture, is similar to a mural or decorative panel and cannot avoid the obligatory blurring carried out with a brush, paint and oil. The range of a single tone and its color shades and unique glazes give the image a special optical illusionism and transparency, manifested at the level of deep layers of the text. This optic forms the author’s grammar of symbols, in which the real contrasts with the unreal, the mundane with the spiritual, and the visible with the invisible. Borrowing and perfecting Veisberg’s concept of “invisible painting” allows Steinberg to rethink the relationship between abstract metaphysics and its concrete visual trace, between the dialectic of presence and the optically non-obvious, and finally, between mysticism and symbolism.

Figure 4.

Eduard Steinberg. An abstract composition, 1970. Oils on canvas 80 * 100. Private collection, Switzerland. https://artinvestment.ru/auctions/2244/records.html?work_id=1164540 (accessed on 26 May 2022).

This appeal to the philosophical and mystical tradition of Symbolism is far from accidental, and has been admirably described by Hans Günther:

It is in the symbolic meaning of light, geometric shapes and numbers, as well as in the frequent use of Christian symbols, that we can find a further difference between Steinberg and the Russian avant-garde. He swings the achievements of the avant-garde around and giving them a symbolic sounding. Whereas the avant-gardists strove for pure form-creation and balance, Steinberg offers the viewer a certain conceptuality through the symbolic semantization of abstract forms. One might say he re-endows the avant-garde art with new semantics—precisely in the sense of returning to the aesthetics of early twentieth-century Russian symbolism, which saw the symbol as a mediator between empirical and transcendent realities.(Günther 2019, pp. 41–42)

Blurred and fluid forms, light haze, soft and indistinct contours, nuances of light and the white light emanating from the beige supremacist square and transforming into the shape of a cross—all of these can be seen in Steinberg’s Dedication to Rothko, 1999 (Figure 5). It owes a lot to metaphysical painting, with its emphasis on reminiscences, allusions and visual metaphor. Steinberg’s pictorial analogy works by giving a precise laconic form to functional signs.

Figure 5.

Eduard Steinberg. A Dedication to Rothko, 1999. Oils on canvas, 195 * 130. Art4 Museum, Moscow. https://www.art4.ru/museum/shteynberg-eduard/ (accessed on 22 May 2022).

Steinberg seems to have been impressed by Rothko’s “color field painting”6 and especially by his work with color and the special energy of the pictorial space. In his hommage to Rothko, Steinberg makes use of monochrome color planes and blurred outlines of the rectangle and the cross, arranging colors to capture unconventional combinations of shades which produces a unique effect of flickering and moving glow.

Steinberg was especially fond of the metaphysical art of the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. Morandi’s artistic vision was akin to still life, with the color nuances built on the scheme of the beige, grey and brown, while vessels, jugs, bottles and other objects, coming in various combinations, appearing clear-cut and tangible. At the same time, a certain plastic language, softening their contours, dissolves them in a hazy haze similar to the sfumato and captures reality through abstraction. Despite the difference in their styles of the two artists, there is something that brings Morandi and Steinberg together. According to Claudia Beelitz (see also Beelitz 2005): “In Morandi, as it is in Steinberg, light is transmitted through color. External lighting has no place in Steinberg, and plays only a secondary role in Morandi. The refracted, muted light that appears in subtle tonal shades both keeps the motifs together and links figures with their background. In this respect, both artists give the rhythmic and organizational role to color” (Beelitz 2019, p. 168). Spatial ambivalence and the play of forms define the metaphysicity—the optical illusion of everyday life in Morandi, and the organics of geometric forms and spheres in Steinberg. The latter observed Morandi as one of the most significant artists of his time and said in an interview to Vadim Alekseev, “I love Morandi–with him, art has ended” (Steinberg 2015, p. 237). He apparently referred to the final liberation of painting from objectivity and the rise of object art, which the artist disliked.

3. Rethinking Tradition: From Metageometry to Neo-Primitivism

An internal link between Steinberg and Malevich traced by the scholars of Russian avant-garde is, in fact, quite evident, and should be the subject of a separate in-depth discussion. I will only glimpse at the most important points and landmarks. As an artist, Steinberg was undeniably influenced by the father of Suprematism and stayed in dialogue with him throughout his entire artistic career.7 In an interview given to Grigory Khabarov, Steinberg thus said about Kazimir Malevich: “We all came out of his square. I am the heir of the entire Russian culture” (Steinberg 2015, p. 227). The artist considered himself a follower of the founder of Suprematism, and repeatedly admitted his influence: “This Russian genius of the world, so to say, colored me, flamed me, and here I am, deriving more pleasure from talking with the dead than with the living” (p. 151). Malevich’s radicalism and his trend towards metasymbolism, his language of the primary forms—the circle, square and cross—all of these come close to Steinberg’s geometrical plastics. He believes that Malevich found that fundamental structural formation and optics of vision, which make geometrical abstraction reach a special kind of materiality. Denying the very presence of pure abstraction in Malevich, Steinberg notes, “With Kandinsky and Malevich there is always a reminder of the subject, a connection with the landscape; their works feature no bare play of forms or combinations of blots. So I call myself a traditionalist, since I am firmly rooted in the ground upon which I was born, and art for me it the matter of its coloring” (p. 217). Seeing geometrical abstraction as an aesthetics of pure form, Steinberg transforms the Suprematist tradition by minimizing its sharp contrasts of color. He was most attracted by the religious and mystical aspects of Malevich’s art. Since the artist for Steinberg was primarily a mystic, he puts together a metaphysical geometry of his own, where abstraction and the sacred presence come joined as a synthetic entity. A “Letter to K.S.”, written on 17 September 1981, is revealing in this respect. It presents an important rhetorical dialogue between Steinberg and Malevich as his spiritual teacher and mentor. In the letter, Steinberg discusses the language of artistic geometry and Malevich’s Black Square “as the ultimate godforsakenness” (p. 38) which can be expressed by means of art.

Apparently, you were born to remind the world of the language of geometry, a language capable of expressing a tragic dumbness. The language of Pythagoras, of Plato, of Plotinus, of the early Christian catacombs. For me, this language is not universal, but it does express a yearning for truth and for the transcendental, a certain affinity with apophatic theology. By leaving the viewer free, the language of geometry forces the artist to abandon himself. Trying to make it ideological and utilitarian at the same time violates this language. So for me it has become a way of existence in the night you named the Black Square. I think human memory will keep revisiting it in the moments of mystically experiencing the tragedy of being abandoned by God. Moscow, summer 1981. Your Black Square has once again been exhibited to the Russian public. And once again there is night and death in… And the question persists–will there be a Resurrection? (Steinberg 2015, p. 39).

In this dialogue, Steinberg presents Malevich as an apophaticist (see Landolt 2015), who observed the cosmic abyss through the black square. There are obvious parallels with Malevich’s own ideas of the Mystery of the Universe and “God as the Absolute of Nature’s perfection” (Malevich 1995, р. 243), which the artist observed as incomprehensible truths. The man who strives towards God as an ideal is on a conscious quest for harmony and cosmic calm. He is struggling to understand the meanings which are impossible to find, as they lie beyond human conscience. In fact, Malevich as an original thinker advances his own interpretation of divine ontology—not of a Christian God, but of a transcendental personality, perfection incarnate and incognoscible: “God cannot have a human meaning; since reaching him as the final meaning does not allow to reach God, since God is the final limit, or, more correctly, the limit of all meanings lies before God, and in God there is no meaning already. Thus, in the end, all human meanings pointing towards God the meaning, will be crowned with thoughtlessness, hence God is the non-meaning rather than meaning. It is his thoughtlessness that must be seen as objectlessness in the Absolute, in the final limit. Reaching finality is achieving objectlessness. It is indeed unnecessary to strive for God somewhere in the spaces of the celestial, since He is present in every human meaning, as every meaning of ours is, at the same time, a non-meaning” (Malevich 1995, p. 243).8

By defying both Suprematism as a utopian project and its Utilitarian aspect, Steinberg accentuates the victory of the spiritual over the material. His “metageometry” is a metaphysical language, a system of symbolic signs endowed with existential meaning and apophatic senses. Just as Malevich, Steinberg accepts the notions of the hidden and unknown God, but follows his own path by interpreting Suprematist forms as signs of mystical and religious experience. In a letter to Valentin Vorobiev, a friend and fellow non-conformist painter, Steinberg leaves behind Malevich’s Suprematism to describe his language as “the tragedy of the Russian history with its church Schism” (p. 189). Hence, the artist appears in the letter as a sectarian9, and the Black Square, as a painting primarily focused on philosophic and religious issues: “His Square is also an icon, but that of the schism in the church” (p. 227). For Steinberg, the icon is not only a narrative of the cult, but a special visual representation. Relying largely on the same signs as Malevich did—circles, spheres, squares and triangles—the artist fills his own lexicon with a different semantic subtext and visual imagery. He calls his plastic language of the 1970s “metageometry", appealing to “Christian archetypes” (Patsyukov 2019a, p. 32), and recreating the inner experience and longing for beauty and perfection. The architectonics of his plastic space touches the earth and the sky, and works with the top and bottom. In contrast to Malevich’s philosophy of rest and Nothingness, Steinberg constructs “supra-worldly” figures that symbolize perfection and finality. Responding to questions from Gilles Bastianelli, Steinberg wrote:

The main problem in my paintings is the top and the bottom, heaven and earth. It seems trivial, but on the other hand, it is an important aspect of <my> philosophy. An attempt to discover beauty which does exist in the world, even though they are killing her. If there is anything left of me after death, I would like it to be beauty. The problems of death and beauty, of the beginning and the end are expressed between the two lines-the top and the bottom. The square is the symbol of the earth, and the black square signifies emptiness <…> These are philosophical and religious issues, and in working with them, we should focus on substances, not formalities. And the substantial side is, first of all, the life of the artist, and not ideology, where things can be added or removed–not this, but life itself. They have removed art from contemporary situation, and are offering life alone. What kind of life is that? Does it have freedom? There is no freedom. As I understand it, you get freedom when you die. For us Russians, death is love, death is memory. Or a pragmatic issue that freedom is not when you take, but when you give something.(Steinberg 2015, p. 252)

In the abstract compositions of the 1970s (Figure 6 and Figure 7) we see the geometric shapes of the cross, the circle, 3D quadrangles, and all of these figures represent the continuity of the universe, and the cyclicity of time (with the four circles on the right and left as if returning the whole composition to unity). Pure geometry is likened to sacred geometry, to Platonic bodies as Euclid described them in Book XIII of his Beginnings.10 In ancient cultures, primary geometric forms revealed energies of primal elements of the universe. Geometric forms were then appropriated by both Hellenistic aesthetics and Christianity, which was reflected “in church iconography” (Barabanov 2019, p. 121). One may also recall the Gnostic tradition and alchemical symbolism.

Figure 6.

Eduard Steinberg. An abstract composition. February. 1970. Oils on canvas, 69.5 * 82.5 cm. Denis Khimilyaine’s collection. https://deniscollection.com/eduard-steinberg/composition-1975-5/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

Figure 7.

Eduard Steinberg. A Composition. 1975–77. Oils on canvas, 100 * 90 cm. Denis Khimilyaine’s collection. https://deniscollection.com/eduard-steinberg/composition-1975-5/ (accessed on 6 June 2022).

While remaining faithful to Suprematist primary forms, Steinberg builds his poetics of geometric forms without color contrasts. While Malevich follows the path of economizing and arrives at minimalism, Steinberg demonstrates an ontological pathos, a rise to God and metaphysics. “He soared above geometry”, as Hans-Peter Riese beautifully put it in his obituary (Steinberg 2015, p. 478). “The inner space of Steinberg’s artistic text”, as Vitaly Patsyukov correctly observed, “turns out to be sturdier than any outer space” (Patsyukov 2019b, p. 208). It is in this personal experience of moral laws and the moral imperative that the way of comprehending the Absolute lies. In developing the concept of his metageometry, Steinberg made use of the inherited tradition of geometric abstraction and built a new relationship between the iconographic and the formal. The ontological advantages he gains are in imprinting the trace of past cultures and in asserting the special status of his transcendental vision:

Taking further the comparison with Malevich, there are two entirely new categories that Steinberg introduced and Malevich did not have. I would define them as existential pity and transcendental tenderness. Malevich’s transcendent being is pure and dispassionate, his forms radiate light and energy, but they have nothing to do with us. He is stern and detached. In Steinberg, two streams seem to be merging-pity as if coming from below and tenderness as if from above. Taking this comparison to a higher level (I apologize in advance for this excessive sublimation), Malevich’s painting can be analogous to a Savior the Bright Eye; and Steinberg’s, to an Madonna with Child. Malevich represents male power and energy, while Steinberg stands for the female, warm, enveloping and soothing, for the weak and gentle. In general, the more you compare the two artists, the more you realize that Steinberg, howsoever often he declares loyalty to his teacher, in fact presents, so to say, a different version of the teaching. Malevich differs from Steinberg not as heaven stands apart from earth, but more like the gap between heaven and earth-and-sky. Existential pity and transcendental tenderness could only have emerged in the era of existentialism, and all of us, I mean my generation, are children of that era.(Pivovarov 2019, pp. 70–71)

Central to Steinberg’s paintings is the cross. On the one hand, this is due to his reinterpretation of the iconographic tradition. The artist observes the icon as not only a cult object, but also an object of visual reflection: "For me, the icon is first and foremost a space of cult, from whence I draw my knowledge. The icon has different dimensions, such as religious or visual. It has a timeless artistic language that stems back to Byzantium. As an artist, I came out of the Russian avant-garde, which was connected to Russian icon painting. It was through the icon that I understood Malevich and realized what I myself was doing” (Steinberg 2015, p. 227). On the other hand, Steinberg’s reflection on God as the Absolute and Eternal Truth is no less important. His religious feeling is close to Malevich’s apophaticism, as indicated in the 1981 letter, and to mystical symbolism. In 1968, he was baptized at the age of 31—a crucial step which had a lasting impact on his creative quest. While being a deeply religious man, he did not belong to any church.11 When asked by Evgraf Konchin if he was religious, Steinberg replied, “I am a believer, though not a man of the church. I try not to judge anyone, and to adhere to certain rules. I paint life as it is, with heaven and earth, so my work is filled with religious symbols: the cross, the black and white, life and death, and emptiness. I am fascinated by the early Russian avant-garde, whose language I dared to restore” (p. 218).12

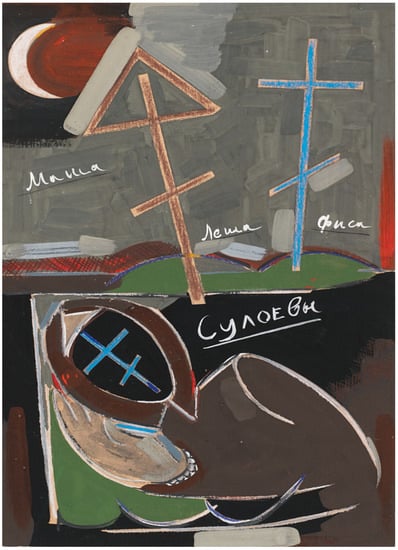

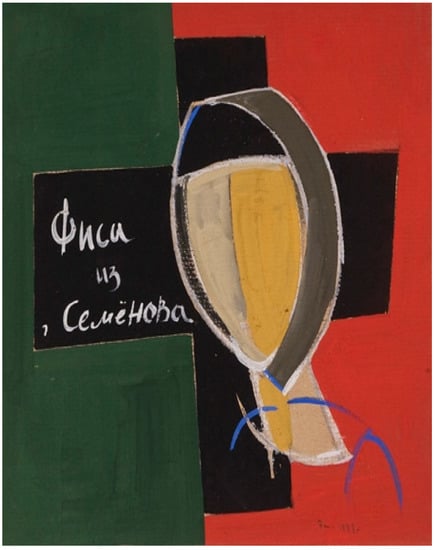

The cross, thus, reproduces the sign on several levels. Steinberg conveys its semantics through various formats of statement. We find reminiscences of the cross in The Countryside series (1985–1987), which was undoubtedly influenced by Malevich’s Peasant Cycle. The plastic language is shaped by the principles of iconography, where the cross is a symbol of sacrifice and redemption, and the ground resembles the “pozyom”, earth as shown on icons (Barabanov 2019, p. 129). On the other hand, the series is apparently imbued with the motif of death and resembles jotted commemoration notes, where all deceased close relatives and friends are listed for their names to be read during the memorial service13 (Figure 8). The series was created when Steinberg was staying in the village of Pogorelka on the bank of the Vetluga River in the Nizhny Novgorod region, and is a requiem for the dead of the Russian countryside. Although the series surely does not feature portrait likeness, the level of symbolization still allows us to see half-destroyed huts, boarded-up windows and cemetery crosses. The dying Russian countryside, which once was the focus of Russian national traditions, evokes the artist’s genuine pain.

Figure 8.

Eduard Steinberg. Masha, Lyosha and Fisa Suloyevy. 1980s. Cardboard, gouache, pastel. 60 * 39. Art4 Museum, Moscow https://www.art4.ru/museum/shteynberg-eduard/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

Some of the departed even receive a personal mention, such as Fisa from Semyonov from the eponymous painting, 1988 (Figure 9), where the title of the painting also works as an epitaph. What we see here is utmost simplification and iconography referring us back to Russian Neo-Primitivism. Members of the Knave of Diamonds group (1911–1912)14 aimed to imitate and use the techniques of the icon painting, lubok (cheap popular print), primitive art, shop signs and popular toys. All of these had their impact on the style of their painting with its simplistic forms, 2D shapes, bright colors and black outlines. Naive vision and childish shapes also appear in Steinberg’s Countryside series. The new alphabet of color in his paintings of the period is dominated by dark colors—black, green, brown, red. The crosses upon the graves of the village people appear in different shapes. The catacomb cross in the Fisa from Semyonov is a simple four-pointed cross, the sign of the victory of life over death and the triumph of Christianity over paganism. Subsequently inherited by the Catholic Church, it was known as the Latin “immissa”, or the Roman cross.15 The cross as the symbol of Christ’s redeeming sacrifice in this painting brings to mind the Old Believers’ cross as well, and this symbol of Church schism and sectarianism is anything but accidental. In Steinberg’s works, it is ambivalent, appearing both as a reference to the fountainhead of Orthodoxy and as an element in the geometrical language of the early Christian catacombs. In Masha, Lyosha and Fisa Suloyevy, we also see six-pointed Orthodox crosses16, which symbolize the ascent to the Kingdom of Heaven.

Figure 9.

Eduard Steinberg. Fisa from Semyonov. 1988. Cardboard, gouache. Moscow Museum of Modern Art (MMOMA). https://mmoma.ru/exhibitions/gogolevsky10/eduard_shtejnberg_esli_v_kolodce_zhivet_voda/ (accessed on 16 June 2022).

The village of Pogorelka for Steinberg is akin to a coffin or a cemetery (pogost) with its dead silence. In a dedicated memoir, “Pogorelka: a village on the hill”, he writes,

The village comes from childhood. Lots of sky, little land. On the horizon, are the roofs of houses and the treetops of an overgrown pogost. Coming from the city, it’s a dream. A dream with your eyes open. The village-silence-silence outside of time. In front of you is your house <…> The house is like a coffin, like an ark, and the land around is a pier. You enter the house–you go into the coffin. Then you go to get some water from the well, and shudder under the gaze of your fellow villagers and their domestic animals. Curiosity and longing follow your trail. You only come here in the summer. And every year someone leaves this place. A new tree-cross rises at the pogost. And the coffin houses still stand. Total emptiness.(Steinberg 2015, p. 55)

This fragment barely hides the pain of losing Steinberg’s village friends, while also exposing the tragedy of desolation and abandonment of the Russian countryside. The interweaving of the real with the unreal, the mundane with the mystical, is conceived in the space of a multidimensional plane, which combines the tradition of Orthodox commemoration and the laconic Neo-Primitivism of the 1910s. The symbol of the inseparable unity of the sensual and the supra-sensual world—the cross—comes as “the intersection of the horizontal line of earthly existence with the vertical of the eternal and the Divine. The semantics of the Christian cross adds an eschatological perspective to this archaic image” (Barabanov 2019, p. 131).

4. Conclusions

Eduard Steinberg’s philosophical and artistic thesaurus cancels the logic of habitual perception due to the multidimensional architectonics of his paintings and appeals to different cultural traditions and languages of art. Bringing back to mind his polemical dialogue with many twentieth-century artists, we can arrive at a number of preliminary conclusions. Having discovered that the view in the multilevel space of Steinberg’s art (metaphysical abstraction, metageometry and peasant lubok) is itself multidimensional, we examined the artist’s work from the perspective of the conjunction of ideas, styles and discoveries in the field of plastic language of both his predecessors (Malevich, Morandi, Rothko) and contemporaries (Veisberg). By appropriating the discoveries of Catacomb Christian art, Russian icon painting and Malevich’s Suprematism, Morandi’s metaphysical abstraction and Veisberg’s “invisible painting”, the artist constructs an artistic universe of his own, where the metaphysics of presence ushers in the idea of apophaticism, concealed Divine Light. By marking invisible traces, Steinberg brings together the invisible and the visible world in the formulas of symbolic signs, focused on personal experience of the spiritual. Christian archetypes, sacred geometry of the ancients and Malevich’s black square shine through the light of the other world and the secrets of the innermost. Optical neoplasticity, where the invisible layer becomes visible due to the discovery of hidden signs, is another important discovery. To decode invisible ideas and symbolic patterns, the viewer must withstand intellectual tension and become an experienced interpreter. Steinberg’s reference to the legacy of Russian Symbolism and the historical avant-garde carries an additional semantic load. Following the pre-existent corpus of ideas and artistic discoveries allows him to set up a morphological infrastructure which can be studied though a number of discursive practices: philosophy, religion, art history and semiotics. A polemical dialogue is a special logic of similarity and difference, of discovering the presence of another’s discourse and an implicit polemic. It is a new reading of the entire previous corpus of pictorial texts, and finding that they somewhat overlap. Steinberg’s semantics of the sign implies different levels of instancing: the vertical, horizontal and hierarchical. In the polymorphic text the artist puts together, one can find traces of folklore and primitivist stylistics, references to Larionov and the grassroots primitive artists of the Knave of Diamonds group. The semantics and chronology of the everyday, the metaphor of the cross as a symbol of death and the finitude of human existence—all these markers of dialogue between the earthly and the heavenly, the secular and the eternal, the light and the dark establish distance from the existential. A legitimate question then arises: what is the meaning of these references to the heritage of Russian and European artists? In our view, Steinberg’s mastering of traditions was to a certain degree a symbolic process. He does not recreate a particular aesthetic system or borrow ideas from the outside, but rather signs off with the deepest respect for his predecessors and their spiritual and artistic experience. Steinberg is quite self-sufficient as an artist, as evidenced by the plastic transformations and stylistic dialectic in his art. It is his uniqueness that determines the dualism of his plastic language, which combines using classics of the avant-garde as his landmarks and setting his inimitably own path and view of the nature of artistic statement.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank the School of Design, National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The term has been suggested by Vitaly Patsyukov, a scholar of arts from Russia. Attempting to define Steinberg’s style, Patsyukov notes the presence of links between the “phenomena of the visible world and corresponding ideas which belong to the plane of the invisible and the most intimate” (Patsyukov 2019a, p. 33). On the one hand, we have here an obvious allusion to Neoplasticism (Nieuwe Beelding)—a new plastic art created by Dutch artists Theo van Doesburg and Pieter Cornelis Mondriaan as an art of primary elements, such as lines, geometrical shapes and figures and the main colors of the spectrum. In 1920, Mondrian published a book in Paris titled Le Néo-Plasticisme: Principe Général de l’Equivalence Plastique. In the book, he proposed the line and a specific rhythm as the main principles of form-building which are somewhat sacred. Mondrian’s hallmark were his abstract compositions of rectangles and squares in «basic colors» and separated with thin black lines. It was the paradoxical simplicity of Mondrian’s lines and shapes that stood behind the basic principles of the art of the Dutch De Stijl. On the other, by introducing the notion of «optical Neoplasticism», Patsyukov emphasizes Steinberg’s unique visual optics, focusing on building a multi-level space where geometrical abstraction and optical illusoriness merge to create a language of art. In this sense, I quite agree with Patsyukov’s definition. |

| 2 | Both works were first published in Paris in 1967: Jacques Derrida. De la grammatologie. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1967, Jacques Derrida. L’écriture et la différence Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1967. |

| 3 | Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ translates as “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour”. The Gospels tell us of the symbolism of the fish in the life, works, death and resurrection of Jesus. The ΊΧθΥΣ sign refers us to many episodes in the New Testament featuring the fish and fishermen, hence the multitude of explanations why it was chosen as a symbol for the Messiah. It must also be noted that some of the Apostles were fishermen and the Saviour Himself called them “fishers of men” (Matthew 4:19, Mark 1:17). For more details, see (Gumerov 2008): Pochemu Iisusa Khrista nazyvali ryboi: https://pravoslavie.ru/7028.html (accessed on 16 May 2022). |

| 4 | An analogy can be drawn here with “covering by discovering”, a famous formulation by Clement of Alexandria (Greek Κλήμης ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, c.150—c.250 CE), Christian theologian and philosopher, head of the theological school of Alexandria. The phrase is linked to the apophatics and liturgical symbolism. |

| 5 | Recalling her meetings with the artist, Elena Murina noted the artist’s inimitable unique style and technique, “Veisberg constantly applied the term ‘touch’, which had a twofold meaning for him. On the one hand, it defined the moment of conjugation of an object and space, that subtle border separating and at the same time connecting them, being a very important indicator of the achieved or broken continuity of the pictorial fabric. On the other hand, the ‘touch’ referred to the moment when the brush touched the surface of the canvas, which should concentrate all the care with which the artist approached the pictorial values at his disposal. Ultimately, each Weisberg painting is "a model of the infinite in the limited space of the finite, where the recognizable and the unrecognizable, the visible and the invisible are in constant equilibrium” (Murina 2000). |

| 6 | Clement Greenberg was one of the first critics of art to discuss this problem. His definition of the abstract is quite indicative: he observes it as pure painting which has a physical impact on the viewer and is endowed with pure plasticity: “The arts, then, have been hunted back to their mediums, and there they have been isolated, concentrated and defined. It is by virtue of its medium that each art is unique and strictly itself. To restore the identity of an art the opacity of its medium must be emphasized. For the visual arts the medium is discovered to be physical; hence pure painting and pure sculpture seek above all else to affect the spectator physically<…> The purely plastic or abstract qualities of the work of art are the only ones that count. Emphasize the medium and its difficulties, and at once the purely plastic, the proper, values of visual art come to the fore. Overpower the medium to the point where all sense of its resistance disappears, and the adventitious uses of art become more important” (Greenberg 1992, р. 4). |

| 7 | It must be noted that the artists of the «second wave of the avant-garde» took deep interest in Malevich and his personality, especially in the radicalism of his creative thought, his attitude to tradition and a new type of artistic utterance. This was mentioned on the pages of the A-Я (Issue 5, 1983), a mouthpiece of non-conformist Russian art, a magazine which was prepared in Russia but published in Paris between 1979 and 1986. The issue featured thoughts on Malevich by Eric Bulatov, Boris Groys, Ilya Kabakov and a number of other non-conformist artists from Moscow. Here is, for instance, the contribution by Oleg Vasiliev: «Malevich appeared to me as a great discoverer. a pilgrim to the summit of intellectual art, a mythical hero who proclaimed the abyss of the «black square» and the «white nothingness». <…> It was emptiness, or rather, «the white nothingness» which was behind the work done now. It was a most serious metaphor by the author of the «black square», the artist who broke through the world of objects to the abyss of another space and ultimately coming to be the one who established objectness on all levels of existence <…> The accent is placed on the moment when the object is liberated from everything, i.e., on the «nothingness» (Vasiliev 2004, рр. 32–33). |

| 8 | Among the academic studies of Kazimir Malevich’s mystical symbolism and apophatism that have been published in the recent decades, the following are to be recommended: (Bering 1986; Bowlt 1991; Goryacheva 2020; Ichin 2011; Krieger 1998; Kurbanovsky 2007; Milner 1996; Mudrak 2016; Marcadet 2000; Rostova 2021; Spira 2008; Sakhno 2021; Tarasov 2002; Tarasov 2017). |

| 9 | In an interview he gave to Vadim Alekseev, Steinberg thus spoke of the matter: “Malevich is a religious artist at his finest, albeit a sectarian. He might have been a khlyst–they had geometric icons. In Russia, one can’t exist without God” (Steinberg 2015, р. 236). |

| 10 | Beginnings (Greek Στοιχεῖα, Latin Elementa), a fundamental work written by Euclid c. 300 BCE and devoted to a systematic reading of geometry and number theory. In Book XIII, Euclid systematizes the knowledge on the five perfect solids which he correlates with natural elements: e.g., the pyramid and tetrahedron match the element of fire. |

| 11 | In Russian Orthodoxy, the votserkovlyonny (lit. ‘churched’) man is a Christian who is a Church member following the teachings of Christ, the rules of Church life, service and the sacraments, a regular reader of the Bible living in accordance with the canons of Orthodox community life. |

| 12 | Steinberg’s baptism brings up another interesting question: how does Steinberg’s art bring together two traditions-Jewish theology and Orthodox religion? As an ethnic Jew, Steinberg feels the drive towards abstraction typical for the old Kabbalistic tradition. but combines it with his interest in Christian iconography. Accepting the teaching of Christ as a “true Jew of the Eternal Israel” (Ioffe 2018, p. 82), Steinberg appeals to Christian symbolism as the space of memory. The man with a "Russian soul", Steinberg kept Malevich as his main interlocutor, but did not refuse dialogue with the iconographic tradition of Andrei Rublev and Theophanes the Greek as well. The artist grew up in provincial Russia, with his painting largely inspired by landscapes of rural Russia, and remained an ardent lover of European culture. Being truly religious, Steinberg was what in Russian can be termed “nadmirny”, a man “above the world” with a transcendental consciousness. In a certain sense Steinberg, having first imbibed numerous religious and artistic traditions, managed to create a personal grammar of most sincere art. This is what he mentioned in his interview to Vadim Alekseev in 2004: “My achievement is that I have built a bridge over time-that’s all” (Steinberg 2015, p. 236). |

| 13 | As reported by Galina Manevich (Beelitz 2005, p. 218). |

| 14 | A group of Russian avant-garde artists comprising, among others, Pyotr Konchalovsky, Ilya Mashkov, Mikhail Larionov, Aristarkh Lentulov, Aleksandr Kuprin, Robet Falk and Natalya Goncharova. |

| 15 | For more detail, see: Pravoslavnye kresty: kak razobrat’sia v ikh znachenii. [Orthodox Crosses and Their Meanings]. https://www.pravmir.ru/kak-razobratsya-v-izobrazheniyax-kresta/ (accessed on 16 May 2022). |

| 16 | Crosses of this shape have long been known in culture: e.g., the six-pointed memorial cross set up by St. Euphrosynia Princess of Polotsk in 1161. |

References

- Barabanov, Evgenii. 2019. Nebo i zemlia odnoi kartiny [Heaven and earth of a painting]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse [A Space Surprised: Thinking of Eduard Steinberg’s Art: A Collection of Articles and Essays]. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, pp. 111–35. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Rolan. 2020. Cy Twombly. Moscow: Ad Marginem Press, Muzei sovremennogo iskusstva «Garazh». [Google Scholar]

- Beelitz, Claudia. 2005. Eduard Steinberg: Metaphysische Malerei zwischen Tauwetter und Perestroika. Köln and Wien: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Beelitz, Сlaudiia. 2019. Cosidetta Realita. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Gаlina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 157–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bering, Kunibert. 1986. Suprematismus und Orthodoxie. Einflüsse der Ikonen auf das Werk Kazimir Malevics. No. 2/3. Minneapolis: Ostkristliche Kunst, Fortress Press, pp. 143–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlt, John. 1991. Orthodoxy and the Avant-Garde. Sacred Images in the Work of Goncharova, Malevich and Thier Contemporaries. Christianity and the Arts in Russia. Edited by Miloš Milorad Velimirovic and William Craft Brumfield. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chudetskaia, Anna. 2020. Fliuidy simvolizma v «metageometrii» Edika Shteinberga [Fluids of symbolism in Edik Steinberg’s “metageometry”]. In Sviaz’ vremen: Istoriia iskusstv v kontekste simvolizma. Kollektivnaia monografiia v trekh knigakh [The Links between Times: History of Art in the Symbolist Context: A Monograph in Three Books]. Edited by Olga Sergeevna Davydova. Moscow: BuksMArt, pp. 402–22. [Google Scholar]

- de Duve, Thierri. 2014. Imenem iskusstva. In K arkheologii sovremennosti [Au nom de l’art: Pour une archéologie de la modernité. Paris: Ed. de Minuit, 1988]. Translated by A. Shestakov. Moscow: Izd. Dom Vysshei shkoly ekonomiki. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1973. Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. Translated by David B. Allison. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1997. Of Grammatology, Corrected ed. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Didi-Huberman, Georges. 2001. To, chto my vidim, to, chto smotrit na nas. [What We See Looks Back at Us]. Translated by Aleksey Shestakov. Saint Petersburg: Nauka Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Goryacheva, Tat’iana. 2020. Pochti vse o «Chernom kvadrate» [Almost everything about the Black Square]. In Teoriia i Praktika Russkogo Avangarda: Kazimir Malevich i ego Shkola [Theory and Practice of the Russian Avant-Garde: Kazimir Malevich and his School]. Edited by Tatiana Vadimovna Goryacheva. Moscow: AST. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1992. Towards a Newer Laocoon. In Art in Theory 1900—1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, pp. 554–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gumerov, Iov. 2008. Pochemu Iisusa Khrista nazyvali ryboi. Available online: https://pravoslavie.ru/7028.html (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Günther, Hans. 2019. Ot konstruktsii k sozertsatel’nosti—Eduard Shteinberg i russkii avangard [From constructing to contemplating: Eduard Steinberg and the Russian avant-garde]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ichin, Cornelia. 2011. Suprematicheskie Razmyshleniia Malevicha o Predmetnom Mire [Malevich’s Suprematist Reflections on the World of Objects]. Moscow: Voprosy filosofii, Izdatel’stvo Nauka, vol. 10, pp. 48–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ioffe, Dennis. 2018. The Garden of Hidden Delights of the Russian-Jewish Avant-Garde. Special Issue: Jewish Underground Culture in the late Soviet Union. East European Jewish Affairs 48: 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, Verena. 1998. Von Der Ikone Zur Utopie: Kunstkonzepte der Russischen Avantgarde. Köln: Böhlau. [Google Scholar]

- Kurbanovsky, Aleksey. 2007. Malevich’s Mystic Signs: From Iconoclasm to New Theology. Sacred Stories: Religion and Spirituality in Modern Russia. Edited by Mark D. Steinberg and Heather J. Coleman. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuskov, Sergei. 2019. Tvorchestvo Eduarda Shteinberga v zerkale idei Serebrianogo veka [Eduard Steinberg’s art in the mirror of the Silver Age]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie, pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Landolt, Emanuel. 2015. À la recherche de la peinture pure et de Dieu: Édouard Steinberg interprète de Malevič. Dans Ligeia. Ligeia 141144: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malevich, Kazimir. 1995. Bog ne skinut. Iskusstvo, tserkov’, fabrika [God has not been toppled: Art, Church and Factory]. In Stat’i, Manifesty, Teoreticheskie Sochineniia i Drugie Raboty. 1913–1929 [Articles, Manifestos, Theoretical Works and Other Texts, 1913–1929]. Moscow: Gileia. [Google Scholar]

- Marcadet, Jean Claude. 2000. Malevich i Pravoslavnaia Ikonografia [Malevich and Orthodox Iconography]. Moscow: Yazyki knizhnoi kul’tury, pp. 167–74. [Google Scholar]

- Marion, Jean-Luc. 2010. Perekrest’ia vidimogo [The Crossing of the Visible]. Translated by Nikolay Sosna. Moscow: Progress-Traditsiia. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, John. 1996. Kazimir Malevich and the Art of Geometry. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudrak, Miroslava. 2016. Kazimir Malevich i Vizantiiskaia Liturgicheskaia Traditsiia [Kazimir Malevich and the Byzantine Liturgical Tradition]. Iskusstvo 2 (597). Moscow: Alya Tesis, pp. 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Murina, Elena. 2000. Vladimir Veisberg. ‘Nevidimaia zhivopis’’ i ee avtor [Vladimir Veisberg: “Invisible painting” and its author]. Nasledie. Istoriko-kul’turnyi zhurnal. №55. Available online: http://www.nasledie-rus.ru/podshivka/5515.php (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Patsyukov, Vitaly. 2019a. Bytie chisla i sveta (o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga) [The being of number and light: On Eduard Steinberg’s art]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Patsyukov, Vitaly. 2019b. Eduard Shtenberg. Dialog s Malevichem [Eduard Steinberg’s dialogue with Malevich]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 201–9. [Google Scholar]

- Pivovarov, Viktor. 2019. K vystavke E. Shteinberga «Derevenskii tsikl» [On E. Steinberg’s The Countryside exhibition]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rostova, Natalia. 2021. Religioznaia taina «Chernogo kvadrata» [The religious mystery of The Black Square]. In Filosofia Russkogo Avangarda: Kollektivnaia Monografia [The Philosophy of the Russian Avant-Garde: A Collective Monograph]. Moscow: RG-Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhno, Irina. 2021. Kazimir Malevich’s Negative Theology and Mystical Suprematism Special Issue East-Slavic Religions and Religiosity: Mythologies, Literature and Folklore: A Reassessment). Religions 12: 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffers, Evgenii. 2019. Ideograficheskii iazyk Eduarda Shteinberga [Eduard Steinberg’s ideographic language]. In Izumlennoe prostranstvo: Razmyshleniia o tvorchestve Eduarda Shteinberga. Sbornik statei i esse. Edited by Galina Manevich. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie, pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Spira, Andrew. 2008. Avant-Garde Icon. In Russian Avant-Garde Art and the Icon Painting Tradition. Aldershot and Burlington: Lund Humphries. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, Eduard. 2015. Materialy k biografii [Materials for a Biography]. Moscow: Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 2002. Icon and Devotion. Sacred Spaces in Imperial Russia. Translated and Edited by Robin Milner-Gulland. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasov, Oleg. 2017. Spirituality and the Semiotics of Russian Culture: From the Icon to Avant-Garde Art. Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art. In New Perspectives. Edited by Louse Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 115–29. [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliev, Oleg. 2004. Portret vremeni [A Portrait of Time]. А—Я. In A Magazine of Non-official Russian Art, 1979–1986, Reprint ed. Edited by Igor Shelkovsky and Alexandra Obukhova. Moscow: ArtKhronika, pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).