Abstract

This article examines autotheory and clinical trauma theory in relation to the author’s studio-based visual arts practice. This is addressed through surveying the development of the drawing series An open love letter. This ongoing series stems from an expanded practice of life drawing and explores experiences of love in relation to PTSD. Trauma is an event that fractures the sense of self, sometimes culminating in PTSD. As someone who experiences PTSD, physical symptoms (sweating, vertigo, emotional flooding) have pulsed against researching trauma. Memory, symptoms, and theory tangle together, challenging expectations of objectivity. The article addresses how autotheory supports the validity of establishing visual arts research engaged with trauma and trauma theory from the embodied experiences of a trauma survivor. The article additionally traces how readings of clinical trauma theory and autotheory inflected across each other in this research. First, through a clinical-trauma-theory reading of autotheory, it examines how autotheory positions itself as restorative of ideological dissociations. Specifically, autotheory intervenes in trends in art practices by privileging conceptual modes over the embodied and emotional. Following, this research establishes the significance of an autotheoretical reading of trauma theory to articulate the embodied experience of the theory. This demonstrates the capacity of autotheory to embrace the associations between research, practice, and lived experiences.

Keywords:

trauma; life drawing; expanded life drawing; drawing; autotheory; PTSD; dissociation; trauma theory; conceptual art 1. Introduction

In my drawing practice, I examine the personal by grounding research from a place of experiential knowledge. In earlier works, the subject matter of the personal has been about articulating forms of intimacy and love through drawing, in particular addressing my partner and my near-two-decade relationship. More recently, this has extended to examining the negotiation between intimacy and trauma that occurs in my relationships more broadly. This is because relationships were the source of my traumatic experiences.

I continue to experience complex posttraumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) particularly (although not exclusively) from long-term developmental or relational trauma in childhood.1 Complex PTSD, proposed by American psychiatrist Judith Herman as a new diagnosis (Herman 1992, pp. 115–29; Courtois and Ford 2013, p. 143), recognises the effects of cumulative, sustained, and repeated traumas (Simon et al. 2020, p. 500), as in childhood abuse. Herman outlines the distinction as “Repeated trauma in adult life erodes the structure of the personality already formed, but repeated trauma in childhood forms and deforms the personality.” (Herman 1992, p. 96). So, where traumatic events in adulthood can have a shattering effect on the self, cumulative traumatic events in childhood have the effect of preventing or distorting the formation of an integrated self, which can later manifest as C-PTSD.

In relational trauma, the events of the trauma arise within the framework of developmental relationships; therefore, so do the triggers. Rather than triggers being, perhaps, environmental (say, the oft-cited scenario of a backfiring car returning a war veteran to the battlefield), the triggers of the relational trauma I experience are interpersonal: a misinterpreted hand gesture, an unsettling tone, a fleeting expression misread, an unfortunately worded sentence, or a silence a beat too long.

I have also had the privilege of being in a healthy, loving, and intimate relationship since I was twenty years old. At—as of writing—thirty-nine years old, in simple terms, trauma and intimacy have neatly bisected the years of my life. Moreover, although intimacy might get refracted through the lens of trauma when triggered, trauma is also refracted through the lens of intimacy via modes of recognition and articulation.

This article follows the trajectory of an ongoing series of drawings titled An Open Love Letter. First begun in 2014, the works set out to ‘draw a relationship’ through the forms and motifs established by conceptual art and applied in what I term the expanded practice of life drawing. These works formed the basis for my practice-based PhD in Fine Arts, which began in 2018. However, between 2016 and 2019, my then-unacknowledged PTSD caused a period of major personal upheaval that ultimately challenged the way I related to drawing as a practice generally and the content of these drawings in particular. This experience laid bare three key points that were, at first, irreconcilable: my lived, personal experiences as I grappled with managing PTSD; the theoretical research I was undertaking for my PhD; and the way my practice, and specifically this series of drawings, resisted accommodating these experiences.

In late 2019 though, I began researching both clinical trauma theory and autotheory. Autotheory umbrellas practices of cultural production that engage with theory from the sites of lived experiences. It disrupts the pretentions of the neutral, objective voice of theory by foregrounding the fact that all theories come from individuals with their own personal, subjective, and embodied experiences and that these experiences almost inevitably feed into their theories (Zwartjes 2019). It does so in part by entangling modes traditionally set in opposition to each other, “[integrating] the personal and the conceptual, the theoretical and autobiographical, the creative and the critical.” (Fournier 2021, p. 7). The move toward autotheoretical modes, Lauren Fournier argues, has arisen as a critique of the artificial division between the intellectual, objective, and cerebral (often aligned with the masculine) and the emotional, subjective, and embodied (associated with the feminine) and the privileging of the former that is seen in Western theory and philosophy (Fournier 2021, pp. 2–3, 5, 43–44).

Perhaps because my understanding of each grew alongside the other, trauma theory and autotheory have become entwined and inform my reading of each to a considerable degree, particularly in relation to dissociation, a symptom of trauma (Herman 1992, pp. 34–35; van der Kolk 2014, p. 66; Davis and Meretoja 2020, p. 13). In the nineteenth century, the physician Pierre Janet theorised the mechanism of dissociation in relation to an event of trauma as the mind ‘splitting off’ from the physical, sensory, and emotional experience of consciousness in response to the horror of the experience, leaving the event unintegrated in the psyche (Davis and Meretoja 2020, p. 13). In more everyday parlance, to dissociate means to, “disconnect or become disconnected; separate.” (Deverson 2005, p. 307).

My trauma-theory-influenced reading of autotheory is that an autotheoretical practice positions itself at points of ideological dissociation. Most broadly, it is positioned as a recourse against the violence of privileging the assumed objectivity of Western enlightenment’s ‘self’ or critical theory’s disembodied ‘subject’ over other epistemologies and politics based on the intersubjective, embodied, and experiential. For example, Robyn Wiegman articulates critical theory as a discourse that, in its attempt to critique the assumed universalism and objectivity of Western enlightenment’s epistemological subject, re-enacts its violence by “inscribing [in its place] an agent-less world governed by the impersonality of language as a disembodied realm” as a new, unacknowledged universalism, whilst simultaneously establishing a canonical body centred on privileged individual critical theorists (Wiegman 2020, pp. 5–6). Wiegman goes on to situate autotheory as, “… A distinctly feminist practice, extending second wave feminism’s commitment to putting ‘flesh’ on the universalist pretensions of established theoretical traditions by situating the story of lived experience in politically consequential terms.” (Wiegman 2020, pp. 7–8). Reintegrating the fractured parts of the traumatised self can be a goal of therapeutically working through trauma; in my reading of Wiegman and others, I see autotheory positioned as a model for reintegrating this key ideological dissociation in a capacious sense by bringing such polarisations into contact with each other. In this article, I address the ideological dissociation as where theory so overwhelms art it almost schisms from practice and how this has reverberated in my own art training (Fournier 2021, pp. 107–9). Autotheory retrospectively contextualised this for me as well as helped to articulate how and why I shifted toward incorporating the personal and emotional into my art practice.

An autotheory-influenced reading of trauma theory helped me reconsider my relationship to trauma theory and imagine anew my relationship with dissociation. As Fournier writes: “Autotheory relies on theorizing and philosophizing from the particular situation one is in, drawing from one’s own body, experiences, anecdotes, biases, relationships, and feelings, in order to critically reflect on such topics as ontology, epistemology, politics, sexuality, or art.” (Fournier 2021, p. 68). From a position such as this, I could begin to understand dissociation as a space from which I could renegotiate my relationship with my drawing practice. In several ways, autotheory became a context that could contain my movements between the valences of trauma as it played out personally, theoretically, and in my practice.

To illustrate the above, this article introduces the drawing series An open love letter and the two main works from this series (The floor we walk on and The days we’ve been together) to illustrate autotheory’s intervention in the ideological dissociations between theory and practice and between the personal and conceptual. Following, I show how an understanding of trauma started to expose where, how, and why my drawing practice at the time could not accommodate the tensions between practice, theory, and personal experience. It then discusses the various iterations of the work A line that, in theory, could connect us as it moved from drawing per se to essay as a mode of drawing. The movement toward writing in my drawing practice began to better accommodate the aforementioned tensions of experiencing and researching trauma. Throughout, I explain how understanding and working with autotheory supported my drawing practice, first, through incorporating the personal into practice; second through negotiating my relationship between trauma and trauma theory; and finally, through being able to encompass more fully writing and drawing as it was occurring in my work.

It is important to note that as an individual within my relationship and as a trauma survivor, I am operating from manifold privileges. The key to autotheory is its engagement with feminist, and particularly intersectional feminist, thinking. As Fournier (citing Stacey Young) writes: “Young reads feminist ‘autotheoretical’ texts as ‘counter discourses’ and as the ‘embodiment of a discursive type of political action, which decenters the hegemonic subject of feminism’, that is, the white, heterosexual, cisgender woman with class privilege.” (Fournier 2018, p. 647). I am a white, heterosexual, cisgender woman with class privilege and my relationship with my husband has enjoyed the privileges that come from us both being white, heterosexual, and financially stable. Additionally, it is in part from these positions of privilege that my experiences of trauma are largely acknowledged and understood as trauma and I have been able to access therapeutic support. This is not a privilege equally available to all trauma survivors; many are treated with suspicion, their experiences are not recognised, and support is frequently unavailable (Davis and Meretoja 2020, p. 5). So, although I work in autotheoretical modes, I want to acknowledge that the project of autotheory more broadly is also about decentring the positions of privilege that I hold.

2. Expanded Life Drawing

I use the term expanded life drawing to define the territory of these drawings. However, my sense of expanded life drawing is loosened from the discipline where an artist draws a model. From my experience as a life drawing tutor in a university art programme, I position life drawing as an accrued, iterative understanding of something based on a period of close observation. My interest is in extrapolating this mode of observation to a literal sense of ‘life’ drawing, that is, the practice of attempting to ‘draw a life’. I draw from life; by this, I mean, I pull out, consider, and try to make sense of things and experiences from my life as a way of making meaning from life. This idea of observation is expanded in my research through broadening ‘seeing’ to something more akin to moving toward comprehension. It is the exclamation, “I see…” that comes from a process of grappling to understand.

My mode of expanded life drawing based on and in modes of description and observation has long been as much language-based as it has been image- or material-based. In this way, my drawings act as descriptions. To describe variously means to give an account of something in words, and to draw, trace, and delineate (Deverson 2005, p. 284; Weber 2003, p. 170). It is in this straddling of language and drawing that I establish this research; it is the gathering of marks on a page, be they marks and lines building an image or lines of text, abstractly or narratively describing an experience.

Although my works have dealt with expanded life drawing in different ways, the series An open love letter centres on trying to draw the relationship between my husband, Justin, and me. In these works, I was attempting to draw the placeholders we use to acknowledge the intangible thing that is a ‘relationship’, whilst acknowledging the poignancy of their inability to fully account for a relationship—the days we’ve been together, the places we’ve lived in, the distances travelled, the spaces dwelt in, the beds slept in, the words spoken, and the ideas shared. All of these things, these placeholders, are meaningful, but all are inadequate for the relationship they are intended to make meaning of.

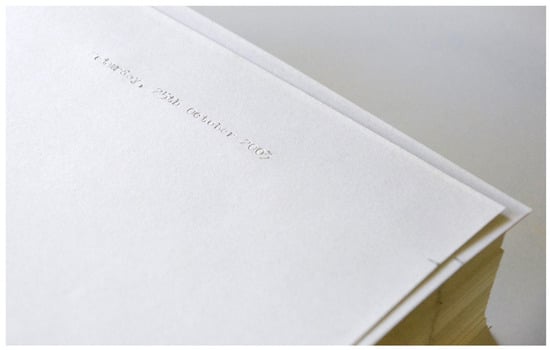

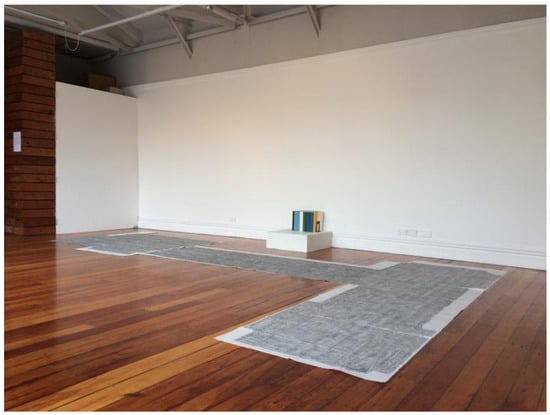

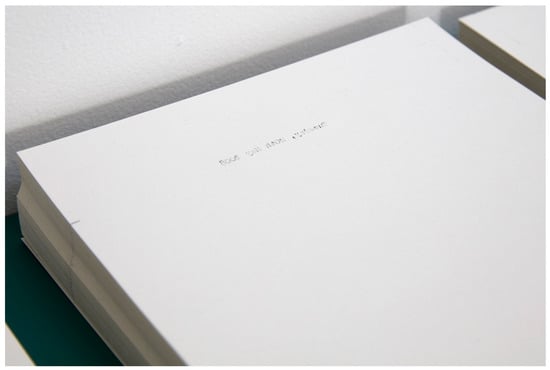

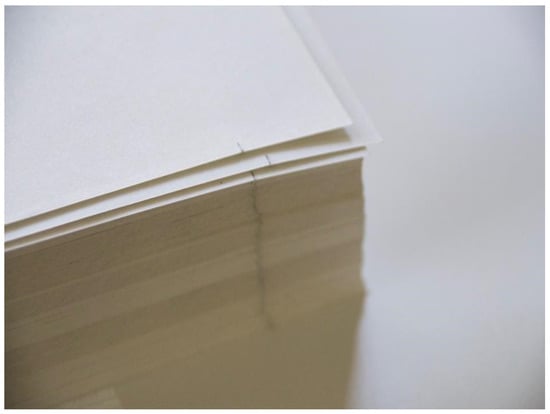

A major work in the series is The days we’ve been together (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The basis of this work is an observation of time both gathering and passing within a relationship and how it can be understood through the form of a date on a page. The work is a series of 4000+ sheets of paper, each of which marks a date that Justin and I have been a couple. The metaphorical lines of dates incrementally changing through a stack of thousands of sheets of paper describes an arc of time from then to a perpetually moving now. In addition, in that positive recording of dates, accruing and accreting, the work also engages with the negative space of what fades, what is left unsaid and unacknowledged, what came before and, ultimately, the fact that it will end. The description of this work lies in how the words of the dates describe that span of time. The dates both mark out the temporal boundaries of our relationship as well as give an account of our relationship (albeit not a detailed one) in words.

Figure 1.

The days we’ve been together, 2018. Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Titirangi, Tāmaki Makaurau Installation detail of Blind Carbon Copy: An Open Love Letter, curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith. Typewriter marks on paper, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett.

Figure 2.

The days we’ve been together, 2018. Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery, Titirangi, Tāmaki Makaurau Installation detail of Blind Carbon Copy: An Open Love Letter curated by Ioana Gordon-Smith. Typewriter marks on paper, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist. Photo: Sam Hartnett.

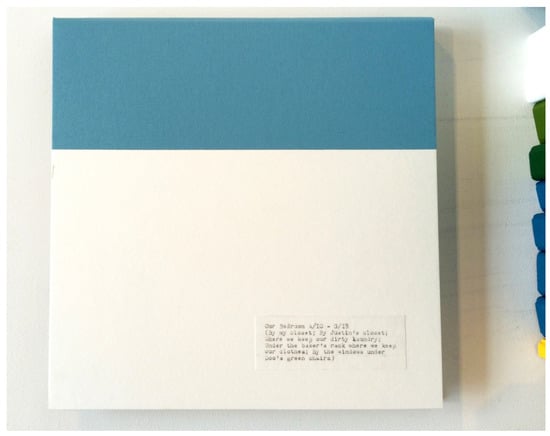

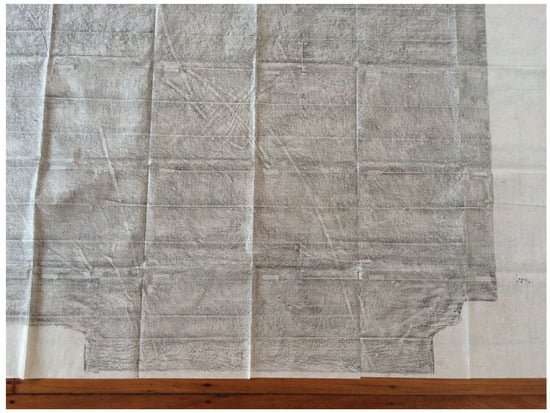

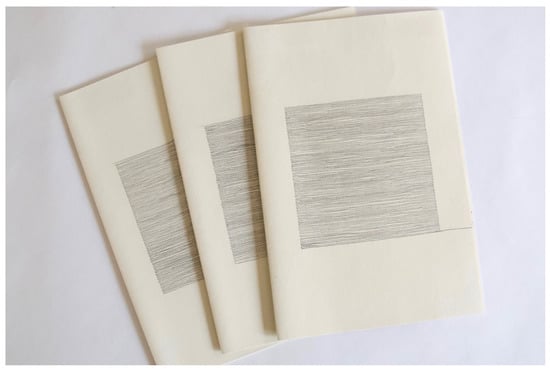

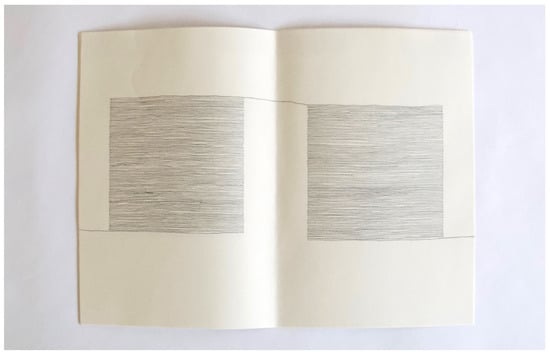

Another key work, The floor we walk on (Figure 3 and Figure 4), is a 94 m2 drawing of the floor of our house in Auckland. It is a series of over a thousand graphite rubbings, recording every accessible centimetre of the texture of the 1950s bungalow’s floorboards, creating a 1:1 drawing of the floor, compiled into the separate rooms, and contained in purpose-made covers. The work thematically engages with the intimacy between us as a couple and the space where that intimacy was, for a period, housed. This was echoed in the intimate process of the rubbing; as a form of drawing, it is centred on touch, press, and impression. The paper touches the surface it records and the graphite touches the paper and forces it into the contours of the floor, forcing the paper to briefly take the form of the floor; I held the graphite. It is a visual representation of the haptic. In other forms of drawing there is an interpretive gap, say, in the moments my eyes shift between the thing being drawn and the drawing. Rubbing, though, is a direct form of documentation of a surface that creates a ‘negative’ akin to a photographic negative. So, in these works, expanded life drawing is positioned as trying to affectively as well as ‘objectively’ (which I pick up on shortly) describe how we share time and where we share space in our relationship.

Figure 3.

The floor we walk on, 2015. Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-tara. Installation detail of Something Felt, Something Shared, curated by Emma Ng. Graphite on paper, dimensions variable. Photo: Andrew Matautia. Collection of Chris Parkin.

Figure 4.

The floor we walk on, 2015. Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-tara. Installation detail of Something Felt, Something Shared, curated by Emma Ng. Graphite on paper, dimensions variable. Photo: Andrew Matautia. Collection of Chris Parkin.

3. Ideological Dissociations and Autotheory

Expanded life drawing became a site for my nascent autotheoretical impulses. When I began the thinking behind these works, I was unaware of autotheory as an emerging field. In retrospect though, autotheory contextualised the way I was starting to make meaning through my practice from my life. In this, I was pushing against the theoretical tendencies of my early art education, which was invested in the poststructuralist turn, postmodernism, and in utilising some precepts of conceptual art such as Sol LeWitt’s ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual art’ and ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’.2 Fournier addresses similar experiences in ‘Autotheory and Activation: What Can Theory Do?’, particularly in relation to (citing Simon Crichtley) the “top-down model, or theory as legitimation of the artist,”, which is also described as “terroristic” (Fournier 2021, pp. 107–8).

However, I experienced some differences, perhaps idiosyncratic of my art school, that An open love letter pushed against. I was always encouraged to start from practice and then find the theory that would support the work (a somewhat diluted version of the above). There was a latent wariness, though, among the teaching staff if students addressed anything explicitly personal or emotional through practice. I was encouraged to source material for making art from outside myself and/or to filter the personal and emotional so fully it would not be legible in the final artwork. Moreover, although we were introduced to art practices that dexterously move between the autobiographical, embodied, poetic, and emotive and the conceptual, theoretical, or political (say, Tracey Emin or Louise Bourgeois), they were sometimes discussed with a sense of disapproval at the perceived overindulgence in the personal. Through this, I internalised a dichotomy about how I should make art; the acceptable side was arm’s length, conceptual, objective, and theoretical; the suspicious side was embodied, personal, emotional, and experiential. The limiting nature of this black-and-white thinking—ingrained at a formative period in life and likely exacerbated by PTSD—remains an ongoing process of unlearning.

To return to my trauma theory reading of autotheory, being taught to see these parts of myself as at once separate and of different worth by the powerholders in an academic art institution enacted an ideological dissociation. Recalling Janet, in trauma, dissociation is the mind splitting off the emotional, physical, and sensory from the conscious, which leaves parts of the self unintegrated. The ideological dissociation occurs in the assumption that there is something dubious or wrong in ways of working that are too openly based on the experiential and emotional so I was encouraged to separate that from my practice. Over time, the suppression of the personal in my artwork led me to feel almost totally detached from my practice in general.

Drawing from my art education, in An open love letter I played on conceptual art’s rejection of the emotional and perceptual in favour of theory to explore the leakiness of that learned dichotomy. Conceptual art came about as a rejection of the then-dominant discourse of Modernism and its hermetic focus on the emotional and perceptual in artworks (Godfrey 1998, pp. 14–15; Wood 2002, pp. 33–34). However, the privileging of theories and ideas in conceptual art and the related purging of the emotional and perceptual, repeated in reverse the problems of Modernism’s discourse, as proponents of both movements assumed it was possible to disconnect the conceptual, perceptual, and emotional.

Although it is contestable that the whole movement can be reduced to this, conceptual art is now known primarily for its engagement with high theory at the expense of more playful manifestations (Godfrey 1998, p. 15). These ascendant theoretical factions of conceptual art have at least been a part of the increased role of theory in art more generally, as outlined earlier (Fournier 2021, pp. 108–9). It is against this backdrop that Fournier situates autotheory as a mode of practice that can remedy what I have positioned as an ideological dissociation in art: “Autotheory reveals the tenuousness of maintaining illusory separations between art and life, theory and practice, work and self, research and motivation, just as feminist artists and scholars have long argued.” (Fournier 2021, pp. 2–3). This is not by purging theoretical tendencies in favour of the subjective, but instead through exploring the layered connections and possibilities that lie between the theoretical and the embodied, personal, emotional, and experiential (Fournier 2021, p. 109). She articulates this as: “…finding strength, pleasure, and jouissance in the practice of that movement through” theory as it comes into contact with the subjective and embodied. For me, moving through implies the availability of a more three-dimensional relationship between poles, which encompasses layered readings of each, seeing them separately, moving between them, looking through one like a lens to the other, and noticing their leaky, blended middle ground.

In An open love letter, I embedded myself in a dialogue with conceptual art, first by using one of LeWitt’s key precepts: “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.” (LeWitt et al. 2012, p. 208). From materials to process to presentation, these works were carefully trialled before I executed them. If there was play in the artworks, it was the play found in a machine: limited and within a very bounded set of parameters (such as where I made a small enough mistake in the execution that I did not feel it was necessary to replace that component). I also used visual forms from conceptual art such as words and repetition in The days and rubbing as documentation in The floor.3 The mechanisation of the ideas alongside the visual forms made The floor and The days legible as works descended from conceptual art.

However, I wanted to subvert the assumptions of conceptual art that schism the emotional and intellectual such as LeWitt’s “It is the objective of the artist who is concerned with conceptual art to make his work mentally interesting to the spectator, and therefore usually he would want it to be emotionally dry.” (LeWitt et al. 2012, p. 208). These works are based on what could be ‘objectively’ knowable about our relationship: its duration, marked by a list of dates, and where it was located through the indexical nature of the rubbings. However, objectivity strains at its own margins. In spite of the dispassionate framing of objectively marking dates or recording spaces, these works carry an affective resonance; this space is actually a place, a home, and a dwelling and these dates are two lives touching, sharing time. I wanted the works to illustrate how the affective and emotional inherently haunt the cool gaze of objectivity. Setting themes of love and intimacy in the visual language of conceptual art held in tension the pared-back aesthetic of the drawings—and relatedly the movement I was evoking—with the excessive intention of trying to draw love.

All the while, though, the works themselves were straining at the seams for me. In my studio diary, I was developing a writing practice around and about these artworks that felt capacious and flexible in a way that the drawings did not. Although this writing was occurring in the margins of my practice, I did not see it as marginal; this movement between drawing and writing set a scaffold that later helped me link drawing and the essay form to address trauma.

4. Trauma as a Form

Running parallel to making the works in An open love letter was the increasing assertion of my PTSD symptoms. Although these works spoke explicitly about intimacy, they were also implicitly involved in actions and dialogues that both unconsciously referenced and arose from trauma: the numbing effect of repeated mark-making, using the presence of these repeated marks to indicate gaps and absences, the outsized importance in the works of what is unsaid or wordless, their functioning as memento mori, and their explication of distance.

Although these drawings were able to express ideas around intimacy, it became apparent to me that unacknowledged trauma was infiltrating the drawings in ways that I was unaware of and thus, was not in control of. Further, trauma was asserting itself through the drawing form itself, specifically (as I go into) in relation to gaps and absences and the unsaid. Because I found drawing forms were mapping so closely to trauma, I could not expand my drawing practice to accommodate an examination of trauma in relation to intimacy. It became apparent to me that I needed to re-evaluate how I was going about my drawings.

On a simple level, I was using repetitive tasks, such as the rubbings that made up The floor we walk on or the typed dates of The days we’ve been together, as a form of emotional numbing. Trauma is a wound in the past that repeats itself in the present through various symptoms and coping mechanisms. As Herman writes, “Long after the danger is past, traumatized people relive the event as though it were continually recurring in the present. They cannot resume the normal course of their lives, for the trauma repeatedly interrupts.” (Herman 1992, p. 37). So, a hallmark of PTSD can be the trauma’s incompleteness because of its atemporality; it disrupts temporality as the past forces itself vividly into the present. Because of trauma’s unfinishedness, numbing can become a coping mechanism for PTSD. Van der Kolk outlines numbing as both part of the dissociative state as well as a way of “bracing against and the neutralizing unwanted sensory experiences.” (van der Kolk 2014, p. 72). He goes on to describe the various behaviours of traumatised people, from drug and alcohol addiction to work and exercise addiction, as “[trying] to dull their intolerable inner world.” (van der Kolk 2014, p. 266). For me, the action of the repeated mark-making dulled the intrusive memories and thoughts; the steady rhythm of accrual was a bulwark against the persistent symptoms of C-PTSD that I was then unable to acknowledge. I would habitually work through physical pain to the point of multiple, recurring injuries to my back and shoulders because I did not want to think and feel. Van der Kolk also notes that these methods give a “paradoxical feeling of control,” which was resonant with my experience; the more the symptoms of trauma asserted themselves, the greater the undertakings I set myself in my artworks and practice until I reached a crisis and entered therapy.

I argue that the theorised form of gaps and fragments in the PTSD memory can map closely to understandings of drawing’s formal relationship between the surface and the mark. PTSD can be understood as the brain’s inability to process the episodic memory of the trauma event into semantic memory; the memory has not been properly encoded as an event that happened in the past (so is reexperienced as if happening in the present) and it remains intense, making it difficult to reflect on and make sense of (Jensen 2019, pp. 13–14). As van der Kolk writes: “[…] processing by the thalamus can break down. Sights, sounds, smells and touch are encoded as isolated, dissociated fragments, and normal memory processing disintegrates. Time freezes, so that the present danger feels like it will last forever.” (van der Kolk 2014, p. 60). So, part of what can characterise the memories of a person with PTSD is that they come in fragments, are filled with gaps and lapses, and are not integrated within the autobiographical narrative experience. In addition to this, Vivien Green Fryd writes of the ‘traumatic paradox’ and states that “the [traumatic] experience often cannot be fully recovered but instead can exist in the mind and body as fragmented memories.” (Fryd 2019, p. 21). So, dissociated memories from trauma can be also understood as both being there and not being there.

In drawing, curators, theorists, and artists often contrast painting’s comparative all-over, full-surface coverage with the more fragmented coverage often found in drawing.4 As Rosand states, “Drawing tends to cover its supporting surface only incompletely; the ground retains its own participating presence in the image, just as the marks it hosts, and which so transform it, retain their autonomy. Ambivalence is an essential and functioning aspect of drawing.” (Rosand 2001, p. 2). A drawing often only partially covers the surface it sits on, setting up a formal collapse between the mark and the surface. If the marks that make up a drawing can be considered an expressed observation, the surrounding blankness of the paper still informs the reading of the drawing. Blank areas of the background can be read as both an image and an absence in relation to the mark. Relatedly, Norman Bryson writes, “… drawing has always been able to treat the whiteness of its surface … as a ‘reserve’: an area that is technically part of the image (since we certainly see it), but in a neutral sense—an area without qualities, perceptually present but conceptually absent.”5 Through this discussion of the relationship between the surface and the mark, drawing is almost definitionally involved in conversations about gaps and fragments and the defining of presence through absences. This can be understood in relation to the conceptually absent trauma’s perceptual incursion through the symptoms of PTSD into the daily life of the survivor. In both PTSD memory and drawing, the surface breaks through and holds apart the narrative quality of the accrued marks.

Addressing the collapse between the mark and the surface, the negative produced by The floor we walk on is disconcerting. Areas that would be shadows, such as the space between the floorboards and the dents and scratches, are highlighted as blank white page (Figure 5). So, absence and gap in this work are visually intensified, pressing forward rather than receding. Relatedly, although The floor we walk on was engaged with a sense of touch, presence, and intimacy, there is also the inescapable press of the absent; the space of the rooms, the missing punctuation of furniture, the weight of the walls, the ceiling, and the way we lived in those rooms. The drawing’s rigorous documentation of only the floor of the house made more apparent what was absent from the drawings.

Figure 5.

The floor we walk on, 2015. Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-tara. Installation detail of Something Felt, Something Shared, curated by Emma Ng. Graphite on paper, dimensions variable. Collection of Chris Parkin.

It is also a drawing that is mostly unseeable. When it has been exhibited, a selection of one space is unfolded and shown in the gallery; the remaining folders are displayed alongside. To date, only the entranceway and hall have been exhibited, with its irregular sequence of narrow rectangles offering the most visually engaging view, as well as a metaphorically apt glimpse of the rest of the work, positioning the viewer at the opening of the house and the drawing. Also, in a one-off public performance, Justin and I unfolded our bedroom, briefly opening that most intimate of spaces for the audience (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The floor we walk on, 2015. Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Te Whanganui-a-tara. One-off public performance for the exhibition Something Felt, Something Shared (curated by Emma Ng). Graphite on paper, dimensions variable. Photo: Louise Rutledge. Collection of Chris Parkin.

The days we’ve been together holds within it the tension between the continuing accrual of pages as we pass each day and an anticipated but unknown end. Like The floor we walk on, its concept is to be a 1:1 of all the days Justin and I have been together; each sheet of paper marks a day in our relationship. However, to simply identify the days, mark them on a page, and then index them within a stack only inadequately addresses the duration of the relationship. Additionally, the collapse between the surface and the mark is taken to heightened levels; the typewriter was used without the ribbon, which had the effect of scoring the paper, forming physical breaks in the drawing (Figure 7 and Figure 8). In contrast to the intimacy of the press in the rubbings, there was a degree of violence in the way the typewriter scarred or even cut through the paper. This form of marking replaced the presence of the typed marks with literal, physical gaps and absences on the page. Both these works trade in an unintentional formal intensification of gap and absence.

Figure 7.

The days we’ve been together, 2018. Detail of back of page, showing scoring of paper by typewriter. Typewriter marks on paper, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist.

Figure 8.

The days we’ve been together, 2018. Detail. Typewriter marks on paper, dimensions variable. Collection of the artist.

The forms of gaps, absences, and fragments are also related to the wordlessness of trauma. As van der Kolk writes:

Even years later traumatized people often have enormous difficulty telling other people what has happened to them. Their bodies reexperience terror, rage, and helplessness, as well as the impulse to fight or flee, but these feelings are almost impossible to articulate. Trauma by nature drives us to the edge of comprehension, cutting us off from language based on common experience or an imaginable past.(van der Kolk 2014, p. 43)

Early literary trauma theory was developed on the premise of trauma’s unutterability, reifying the unspeakable, the unrepresentable, and the forgotten as primary symptoms of PTSD (Davis and Meretoja 2020, pp. 18–19; Gilmore 2001, p. 92). More recent research into trauma and, following, literary trauma theory, has challenged the uniformity of the assumption of language’s failure or the unspeakableness of the effects of trauma (Fryd 2019, p. 22; Gilmore 2001, pp. 6–7; Caruth et al. 2019, p. 48). Nonetheless, the notion of language failing has resonance with my experience. It has taken time and practice to learn to frame words around the traumas that occurred in my childhood.

In The Days we’ve been together, there is a paradox in its use of words. The drawing is made up of words, thousands of them, in the form of dates but the presence of such a quantity of repeated, abstract words to ‘describe’ our relationship has the effect of spotlighting what is unsaid in the work. Relatedly, The floor we walk on presents an empty space, the negative of a marked and scuffed floor, to represent how a couple shares and houses a relationship. Although the silence of the form of drawing that I was using was suitable for articulating intimacy, the absence of language exacerbated the theorised failure of language in trauma.

There was a methodological collapse. The two negatives could not make a positive; the two forms of gaps and the two absences of language—the experience and theorisation of trauma and the silence of the form of drawings I had previously engaged with, as expanded as that practice was—could not make an artwork. I needed writing and words, running and flowing in descriptive, narrative form, in order to make artworks that could negotiate the complex relationship between trauma and intimacy.

5. Trauma Theory and Autotheory

Through nascent autotheoretical impulses, I had begun to integrate the personal into my art practice. Because of its comparative longevity, stability, and security, I could reflect on the love and intimacy between Justin and me. I could process our relationship through the forms of art with which I was conversant. Despite these important acts of progress, researching trauma theory as I personally grappled with PTSD was new and volatile. It felt anathematic to integrate the messy, visceral, and emotional PTSD experiences I was having into my practice-based research.

Although an understanding of trauma contextualised what I was personally experiencing, trauma theory alone produced its own problems regarding how I could engage with it from the place of a ‘survivor’. Trauma theory defines dissociation as an inhibiting symptom that, as someone with PTSD, I am affected by, and—in my reading—the relationship I ought to have with it is to therapeutically address it until it goes away. I found that this single direction definition of dissociation was, itself, inhibiting. Relatedly, although reading about trauma theory was useful for explaining what I was experiencing, as someone struggling with PTSD, reading about trauma theory was unsettling. To form their theories of trauma, clinicians—as the subjects in charge of building and defining a body of knowledge—use as the objects, the experiences of survivors, sometimes directly as case studies and sometimes indirectly as a general scaffolding for their ideas. Although there might be careful collaboration in how this relationship is managed, from the outside it can read as power objectifying vulnerability for its own gain. The objectification I saw occurring in theory-building leaked into the way I saw myself in relation to the theory: as another trauma object being indirectly spoken about by disembodied authority figures. Further, if my experience diverged from trauma theory, I would catch myself seeing my experience as invalid, rather than seeing that divergence as a lack of the capacity of trauma theory to fully account for the manifold personal experiences of trauma.

My parallel reading about autotheory started to structure for me a new relationship with both trauma and trauma theory. As Arianne Zwartjes writes:

Autotheory argues, the physical and graphic details of my embodied life are just as important, just as ‘high-minded’ or elevated, as this theory I will hold up side-by-side. Autotheory says too: all theory is in fact based in someone else’s experience of their one particular body, though they have conveniently erased it from their theorizing and from their writing so as to seem like a disembodied brain, a neutral voice.(Zwartjes 2019)

Zwartjes, here, positions for me the possibilities that autotheory offers a new way to negotiate a theory that talks indirectly about me. To use her phrasing, autotheory emphasises that although traumatic experiences are real, lived, and unique events, trauma as a definition, as a mechanism, and as a part of diagnosis, is a theory. Autotheory reminds me that trauma theory reifies the complexity of lived experiences into a category that can be defined and articulated as a potentially shared phenomenon, but it can never map perfectly every real, lived, and unique experience of trauma (Zwartjes 2019). Based on this, trauma theory will always be lacking.

My relationship to trauma is already the embodied experience of a theory. Trauma is a part of me. It is in my reactions, symptoms, and memories. Therapy, as my therapist says, is a process of better metabolising the real experiences of trauma. Furthermore, like interrupting a conversation about yourself that you overhear, autotheory gave me ways to be in conversation in a critical and emotional capacity, not just with trauma theory but with the trauma itself in that I can hold up as equally valid, alongside the neutral, disembodied voice of the theory, the charged, embodied experience I have of trauma.

In addition, autotheory supports my negotiation between trauma theory and the lived, emotional, and sometimes chaotic space of experiencing PTSD as a place from which to make artworks. Through this, autotheory disrupted the unidirectional relationship I had with trauma theory that led to feelings of objectification. Autotheory helped me realise that trauma theory did not just have to be about me but that I could make it for me. Autotheory instead suggested a way for me to explore how I could inhabit dissociation by helping me to take ownership of dissociation and translating it into a renegotiation of my practice.

6. A Line That, in Theory, Could Connect Us

A line that, in theory, connects us became a thread that traversed the shift An open love letter made as I moved from drawing per se to using the essay as a form of drawing. The methodological collapse I found in my earlier drawings necessitated my pushing back against the assumptions of wordlessness in trauma. I could both see myself and not see myself in this discourse. At first, my trauma memories were images, sounds, and sensations. However, I could not tell my therapist through images or sounds or sensations. I would just be mute in her office, with the images, sensations and sounds whirling through me. So, I had to learn to describe. That is, I had to learn to frame words around my experiences. I practised thinking the words and then saying the words. So, yes, trauma was, for a long time, wordless. Then it was not wordless. More than that, I needed words, and I saw how drawing was lacking that for me.

The early thinking for A line that, in theory, could connect us came while on residency in Banff in 2016. The idea arose from the weighty sensation of distance causing homesickness. I drew a single 390 m line across a large sheet of paper with the impossible intention of making it as long as the distance between Justin and me (Figure 9). Alongside this drawing, I was filling my studio diary with research about distance, such as great circle distance, the angle of flights an aeroplane takes between New Zealand and Canada, and the coastline paradox.

Figure 9.

A line that, in theory, could connect us, 2016. Studio experiment detail. Pencil on paper. Collection of the artist.

Some years later, I revisited this drawing with the intention of creating a book of the pencil line representing that 12,287 km distance between Wellington and Banff but scaled down to 1:1000 (Figure 10 and Figure 11). While I worked on that drawing, Justin travelled to Vancouver and I wanted that line to somehow, no matter how fragile, form a fine land bridge made of graphite to connect us, in spite of its inadequate physical length. However, A line was unintentionally reiterating all the trauma forms of The floor and The days—gaps, absences, wordlessness, repeated gestures—and could not accommodate how my growing understanding of trauma was making me realise that An open love letter needed to address both love and trauma. As discussed, writing was already a part of my drawing practice, hovering in the margins, holding spaces for the ideas and thoughts that could not be accommodated in the drawings themselves. As drawing and trauma started to form too close an analogue, I moved deeper into my writing practice and gravitated toward the essay as a form.

Figure 10.

A line that, in theory, could connect us, 2019. Studio experiment detail. Pencil on paper. Collection of the artist.

Figure 11.

A line that, in theory, could connect us, 2019. Studio experiment detail. Pencil on paper. Collection of the artist.

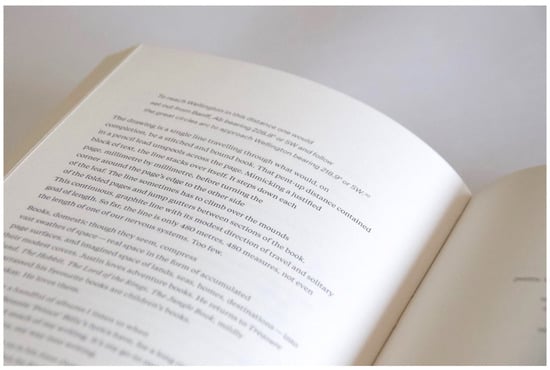

At the same time that I wrestled with drawing that line, I wrote an essay also titled A line that, in theory, could connect us. It took an epistolary form; I wrote to Justin telling him about these various lines filling my thoughts and pages. The essay picked up on the research behind the drawing I did in Banff. I wrote about how, in their potential infinitude, lines are bound up with promise even in their inadequacy to actually bridge gaps. It described the drawn line as it traversed the contours of the book (across pages, between sections, around edges) and speculated whether the rough edge of the graphite line could be subject to the coastline paradox; could it, in fact, contain enough length to connect us (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Elsewhere, or at sea, 2022. Inside detail of part of the essay A line that, in theory, could connect us. Limited edition artist book.

In turning to the essay, the form of the line became lines of facts, narratives, quotes, and anecdotes. It was less about that fine, ceremonial form of the long, lead mark traversing pages. Even though it was still inadequate in traversing the distance, the essay activated the page in a way that contained infinitudes and possibilities alongside those futilities. Iterating A line that, in theory, could connect us into the essay form gave a textual figuration to the manifold ways I was experiencing distance in a way that the drawing did not.

This movement toward the essay as a part of drawing practice had two effects. It first recognised more fully the relationship between drawing and writing that was already inherent in my practice. Further, by centring writing within drawing, it removed the privilege I had given to drawing over writing. Drawing and writing were now operating as twin cores of my visual arts practice that offered movement through, following the Fournier-ian sense. At different times, as separate, things to move between, lenses through which to reinterpret each other, and a joined space with a fruitful middle ground. As I used it, the essay is a form of non-fiction writing that pulls from my life experiences. It is unfixed in style and able to employ different writing styles—poetic, scientific, journalistic, and so on—depending on the essay’s subject. The key to how I use the essay as a form of drawing is that it is anchored in observation and description, as aligned with my broader drawing practice. The essay as a form is definitionally linked to notions of trialling and attempting. My experience of life drawing is tied to notions of searching and testing through observation; as I draw, I examine the form in front of me, trying to establish from fragments small points of relation from which to build the form on the paper. In my expanded life drawing, whether through drawings per se or the essay as drawing, I grapple with understanding and representing a life. Each train of thought recorded as a mark or word is an essay toward understanding. I see the essay as a mode of drawing based on language, similar to the ways that gestural or contour or planar are modes I slip between as I pay attention to different aspects of what I am drawing.

Secondly, in opposition to my own mechanisation of the idea in The floor and The days, the essay as drawing could sprawl to an idea’s furthest boundaries, fleshing out what the drawings would only otherwise hint at. Inherent in this, the essay form more generally began to answer questions for me about how to negotiate and articulate the experiences of PTSD in relation to intimacy. On the essay, Theodore Adorno writes: “It thinks in fragments just as reality is fragmented and gains its unity only by moving through the fissures, rather than by smoothing over them.” (Adorno 1984, p. 164). The essay—like drawing—is a dialogue with dissociative forms such as gaps, fragments, and absences. However, as opposed to drawing’s symbolic, mimetic engagement with trauma that pushed away my interrogation (which echoed my experience of reading trauma theory), the essay offered me words as a way to reckon with dissociation. By setting up the relationship between the writing and visual arts disciplines, and through a broader series of essays as drawings based on described observations, the engulfing void of dissociation became legible. The dissociation and the trauma were first briefly glimpsed. Then they were looked at, seen, acknowledged, examined, articulated, and rendered.

7. Conclusions

In my still-evolving engagement with this still-evolving field, autotheory has led to several major shifts in my visual arts practice. Its positioning as restorative of ideological dissociations retrospectively contextualised my impulse toward incorporating the personal and emotional into my practice, buttressed my negotiations between trauma and trauma theory, and gave a foundation for the relationship between the essay as a writing discipline and drawing as a visual arts discipline. As Fournier writes: “… autotheory seems a particularly appropriate term for works that exceed existing genre categories and disciplinary bounds, that flourish in the liminal spaces between categories, that reveal the entanglement of research and creation, and that fuse seemingly disparate modes to fresh effects.” (Fournier 2021, p. 2). As I found and struggled against the limits imposed by breaking apart the experiential and theoretical, the conceptual and emotional, the embodied and disembodied, writing and drawing, and practice, research, and life, autotheory nimbly moved between each to make legible a valid space for making, thinking, and living between them.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Please note: this paragraph relates to my experience of C-PTSD and the triggers relevant to me. |

| 2 | ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ was first published in 1967; ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’ was first published in 1969. I have accessed these texts from (LeWitt et al. 2012, pp. 208–10 & 214–15). |

| 3 | Tony Godfrey outlines in general terms the four forms that conceptual art may take: the readymade—an everyday object that is asserted as art; an intervention—that is situating an image, text, or object out of context to highlight the nature of that context; documentation—where the evidence (maps, charts, photographs, etc.) that remains of the actual artwork is what is presented; and words, where the concept, proposition or investigation is presented in the form of language. Additionally, Paul Wood notes repetition as a strategy (Godfrey 1998, p. 7; Wood 2002, p. 37). |

| 4 | Emma Dexter builds on the writing of Norman Bryson, Walter Benjamin, and Michael Newman in (Dexter 2005, p. 6); Claire Gilman develops this line of thinking via David Rosand in (Gilman 2013, p. 14). |

| 5 | Norman Bryson in (de Zegher and Newman 2003, p. 151). |

References

- Adorno, Theodor W. 1984. The Essay as Form. New German Critique 32: 151–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruth, Cathy, Romain Pasquer Brochard, and Ben Tam. 2019. “Who Speaks from the Site Of Trauma?”: An Interview with Cathy Caruth. Diacritics 47: 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtois, Christine A., and Julian D. Ford. 2013. Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Scientific Foundations and Therapeutic Models. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Colin, and Hanna Meretoja, eds. 2020. The Routledge Companion to Literature and Trauma. Routledge Companions to Literature. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Zegher, M. Catherine, and Avis Newman. 2003. The Stage of Drawing: Gesture and Act; Selected from the Tate Collection. London: Tate. [Google Scholar]

- Deverson, Tony, ed. 2005. The New Zealand Pocket Oxford Dictionary. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dexter, Emma. 2005. Vitamin D: New Perspectives in Drawing. London: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, Lauren. 2018. Sick Women, Sad Girls, and Selfie Theory: Autotheory as Contemporary Feminist Practice. A/b: Auto/Biography Studies 33: 643–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, Lauren. 2021. Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fryd, Vivien Green. 2019. Against Our Will: Sexual Trauma in American Art since 1970. State College: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Claire. 2013. Drawing Time, Reading Time. Drawing Papers 108: 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, Leigh. 2001. The Limits of Autobiography: Trauma and Testimony. New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, Tony. 1998. Conceptual Art. London and New York: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, Judith. 1992. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror, 2015th ed. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Meg. 2019. The Art and Science of Trauma and the Autobiographical: Negotiated Truths, 1st ed. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- LeWitt, Sol, Béatrice Gross, and Natasha Edwards. 2012. Sol LeWitt. Translated by Miriam Rosen. Metz: Centre Pompidou-Metz. [Google Scholar]

- Rosand, David. 2001. Drawing Acts: Studies in Graphic Expression and Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Naomi, Eric Hollander, Barbara O. Rothbaum, and Dan J. Stein. 2020. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Anxiety, Trauma, and OCD-Related Disorders, 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, 2015th ed. London: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Paige. 2003. Describe, v. In Collins Pocket Dictionary & Thesaurus. London: HaperCollins Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wiegman, Robyn. 2020. Introduction: Autotheory Theory. Arizona Quarterly: A Journal of American Literature, Culture, and Theory 76: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Paul. 2002. Conceptual Art. Movements in Modern Art. London: Tate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zwartjes, Arianne. 2019. Under the Skin: An Exploration of Autotheory. Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. 6. Available online: https://www.assayjournal.com/arianne-zwartjes8203-under-the-skin-an-exploration-of-autotheory-61.html (accessed on 5 July 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).