Abstract

This article scrutinizes the use of liminality as a term to understand medieval dance practices. With the case of the feast day of St. Eluned described in Gerald of Wales Itinerarium Cambriae, I first present common ways that historians and theologians have used the term liminality in order to describe historical depictions of feasts of saints where more unruly forms of movement and dancing have happened. I then analyze this specific depiction by Gerald of Wales through a combination of a kinesic approach and a hermeneutics of suspicion and charity. This approach shows that earlier understandings of dancing always being a problematic element in traditions of Christianity in the west needs to be nuanced. After this, I turn to the critique that Caroline Bynum Walker has brought up, concerning the use of the term liminality in the medieval context. Taking her critique seriously, I return to the story of St. Eluned by focusing on the lived religion from the perspective of the female characters in the setting. Finally, I also bring in Vincent Lloyd’s distinction between rituals and liturgy, to further strengthen how theological discussions can bring in more nuanced and important additions in how we may understand chaotic forms of medieval dance in new ways.

Keywords:

dance; theology; dance history; Wales; saints; liminality; relics; women; liturgy; ritual; hermeneutics of suspicion and charity; kinesic analysis 1. Introduction

In this article, I argue that dance creates theology, rather than being a mere reflection of it. I advocate for the need and benefit of mixed method approaches for both researchers in theology and dance history, when it comes to understanding the religious meaning and purpose of dance in historical records. With the specific case study of the celebration of St. Eluned’s feast day found in Gerald of Wales’s Itinerarium Cambriae I show how kinesic understanding, which is an approach used in dance historical studies, may enrich theological reflection. I further show how analysis of textual sources describing dance benefit greatly from both on-site visits and engagement with iconography. I also show how dance history may gain important insights from following theological arguments concerning the relevance of art as theology (Sarah Coakley’s Théologie totale), as well as specific distinctions made in political theology between the concepts of ritual and liturgy.1 Furthermore, I argue that dance historians need to become more nuanced in how they read and use texts by church authorities.

The main material of this article is a story found in Gerald of Wales’s Itinerarium Cambriae. It is said to be the most detailed medieval description of traditional circle dances.2 In most sources, when the feast of St. Eluned is brought up as an example of dancing in the early medieval period, only parts of the account are quoted.3 Dom Louis Gougaud, who is often referred to in theological treaties on dance, sweeps over the account without much regard, simply grouping it together with the Kölbigk dancers as involuntary spasmodic movements.4 He further remarks that the only purpose of telling stories like these was that they could be used as examples that warn people away from dancing.5 Similar to the recent writings on the Kölbigk dancers in The Cursed Carolers in Context (Renberg and Phillis 2021), I argue that there is much more than a warning to be found in this story.6 Theologically, I argue that the story of St. Eluned’s feast day should be read not primarily as an unruly form of dance, instead, it should be understood as a celebration of a feast day of a saint. For such an understanding, Peter Brown’s use of the term liminality (based on Victor Turner’s development of this concept) is a useful tool. However, I argue that for the terminology of liminality to function in this context it needs to be paired with other concepts brought forth by Brown, such as reverentia, praesentia and potentia. In this combination, the idea of liminality may open up for a theological view on how Christian communities understand their interactions with the divine as, potentially, politically and socially transformative. I further argue that reading dance kinesically, instead of through pre-set ideas about the Church always condemning dance, will help us understand the multi-layered potency of dance in the theological imagination of the medieval period.

In the second half of this article, I then move even further than this. I argue, along with Caroline Walker Bynum, that using the term liminality in a context containing examples of women and laity dancing, as well as in understanding the descriptions of the life of a female saint, the idea of liminality reaches its limits. Instead, I suggest a hermeneutics of suspicion and charity, which reaches for materials beyond the accounts given by male authors. This methodological approach opens up for reading the accounts created by male authors, both with a critical tone, and to find other venues through which one can engage creatively with the lived experiences of women doing theology. It is in this context that the difference brought forth by Vincent Lloyd between dance as a ritual, or dance as part of liturgy, will become significant. When dance is understood as a ritual it will, even within the context of the idea of liminality, mainly be read as a sign of a praxis of social cohesion. When, however, dancing is part of the liturgical expression of the community, it carries the capacity to even alter social norms. In this last section, I thus venture into understanding the account of St. Eluned’s feast day in the context of dance creating theology.

In the end, this article thus offers two different ways in which to read this ethnographic depiction of dancing given to us by Gerald of Wales. It will be up to the reader to judge which of these bests fit their understanding of dance in the medieval period.

2. Background and Methodology

In articles dealing with the dance practices that can be found from the medieval period, liminality has been used as a framework to understand these events. Many of these cases refer to Victor Turner’s theory of liminality, which I will return to in the next section. Examples of the medieval dancing discussed range from unruly carolers in Christmas stories to Gerald of Wales’s explication of the dancers at the feast of St. Eluned.7 In this article, I point out some of the possibilities of understanding dance with the help of liminality. Simultaneously, I argue that when one wants to understand medieval dance happening in and around churches, historians and theologians need to engage in a methodology that employs multiple frameworks of interpretation. Furthermore, both Peter Brown and Caroline Walker Bynum have highlighted the challenges that arise when historical research wants to engage with the lived religion of a specific social class and/or gendered community.8 In this work, I will relate and connect those remarks to the praxis of dancing, arguing that understanding dance features at a saints day celebration requires more theoretical reference points than the framework of liminality may offer.

Historical studies interested in dance before the modern period run into a complex set of challenges when it comes to an understanding of the role and function of the dancing.9 This dilemma is two-fold. On one hand, the fleeting nature of dance—leaving very few material traces behind—always presents challenges for textually focused academic research. Even in a time of video and film, the ambience of the surroundings and the sensory experience of moving in space cannot be fully captured or reproduced.10 The Medieval Folklore encyclopedia explains that information about dance must be gathered from iconographic sources, literary references and sometimes musical evidence.11 This is well exemplified in Kathryn Dickason’s Ringleaders of Redemption: How Medieval Dance Became Sacred (Dickason 2020), where she elaborates with a comprehensive set of images and textual sources. However, as Dickason points out, there has been a strong propensity towards binary thinking when describing and interpreting medieval dancing.12 Furthermore, in Through the Bone and Marrow: Re-examining Theological Encounters with Dance in Medieval Europe (Hellsten 2021). I explain that, particularly when it comes to a theological understanding of dance, the social imaginary of the researchers has prevented them from engaging seriously with dance as a source of theological knowledge. These are some of the reasons why this article adopts a hermeneutics of suspicion and charity as its methods of enquiry.

Sarah Coakley describes that her Théologie totale, with its hermeneutic of suspicion and charity is developed as a method which addresses the particular challenges that are brought forth when praxis meets theory, and previous generations of scholars have ignored more subversive aspects of theology. She explains that, especially when the patriarchal suppression of women, and questions of race and class are brought forth in the materials, a hermeneutics of suspicion is needed. Coakley’s hermeneutics of suspicion is described as “an attitude towards texts that is sceptical about their surface appearance and seeks to reveal authors’ unstated and in particular improper motives”.13 In the current article, such suspicion is applied to the primary text of Gerald of Wales, and the secondary textual interpretations that previous scholars have used when elaborating on the concept of liminality in their readings of Gerald of Wales.

Coakley points out that when researchers are caught up in hegemonic discourses and/or epistemic frameworks—over-emphasizing textual materials and language-based understanding of dance, for example—suspicion is one, but not the only way forward. Coakley, elaborating on Paul Ricoeur’s writing, argues that artistic works can be used to unsettle previous politically and socially “dominant” ways of thinking.14 The arts in general and in this article—dancing in particular—are seen not as an illustration of doctrine or a mere outcome of worship or cultural traditions.15 Instead, dancing creates theology, enabling new expressions of doctrine while simultaneously articulating the lived religion of the people taking part in the dancing. This is something I wish to demonstrate when employing a hermeneutics of suspicion to my reading of Gerald of Wales’s depictions of the feast day of St. Eluned.

Coakley further states that over-emphasizing suspicion also has its flaws. She is particularly wary of the kind of arguments that some strands of feminist theology bring forth, where it is presumed that skepticism will always have the last word. In these depictions, a position of powerlessness is more often reproduced than over-turned, when historical evidence could show us a contrasting story.16 Coakley, along with Lisa Felski, thus brings forth the complement of a hermeneutics of charity to be kept hand in hand with our suspicion. The interpretative patterns suggested by Caroline Walker Bynum and Jane Cartwright, referred to in the second part of the article, want to contradict the tendencies of medieval scholarship to reduce the agency of women. In a similar manner, I aim, in the last part of this article, to present a reading of Gerald of Wales’s story that centers on the female experiences of dancing together at the feast of St. Eluned. In her Limits of Critique (Felski 2015), Felski writes that:

…both art and politics are also a matter of connecting, composing, creating, coproducing, inventing, imagining, making possible: that neither is reducible to the piercing but one-eyed gaze of critique.17

In order to understand how art, dancing and theological expressions from the medieval period may have focused on connecting, creating, co-producing and imagining new ways of being together, a researcher also needs to apply a gaze that is full of charity towards the materials that one encounters. Only by reading and interpreting historical materials with a sense of awe and wonder, will certain elements of the descriptions and depictions open up and reveal themselves to the researcher.18

In particular, when it comes to questions of religion and theological understanding of previous periods, earlier scholarship has presumed certain strands of thought to be superstition or irrational—wanting to psychologically, or even medically, explain away religious experiences.19 In this article, I apply charity as a tool for perceiving the dancing and the religious experiences from the point of view of the practitioners and participants in the rituals. Thus, I frequently apply terminology used by Peter Brown, going beyond liminality, to depict the experiences of relating to martyrs and relics in the early church and early medieval period.20 This includes, but is not limited to, terms like potentia and praesentia of the saint.21 To contextualize the story of the feast day of St. Eluned liminality only takes us so far—deeply theological concepts are also needed. Further, in my attempt to combine a hermeneutic of suspicion and charity, I bring in the theological distinctions made between rituals and liturgies by Vincent Lloyd, in the later part of the article.

Finally, this brings us to this article’s second and last aspect of methodological approaches. When looking at historical depictions of dancing, the most challenging concern is often, not the absence of primary dance sources, but rather, a challenging feature is the fact that texts cannot convey how movements functioned in space and time. As I have already established, Coakley’s hermeneutics of suspicion and charity, opens up to include any art as theology, so it is willing to move beyond texts. However, the lack in her work is that she provides no tools for how to do this.22 This is why I have turned instead to the recently well-argued points about historic dance depictions found in The Cursed Carolers in Context (Renberg and Phillis 2021).23 In this book on medieval dance depictions, a whole chapter is devoted to the need for a kinesic approach to historical dance materials. Rebecca Straple-Sovers explains that kinesic analysis includes following the characters’ gestures, manners and postures in their depictions.24 It “foregrounds the bodily movements performed by characters within literary works and considers how they function as a system of expression and meaning-making”.25 This makes it possible to ask questions, such as how the dancers’ movements supplement, contradict, or complicate their verbal interactions or the narrative content? What might be revealed about the characters, their interactions, states of being and emotional states, from the movements? To this, I would also add: What could be perceived about the meaning-making practices of being in relationship to the divine, and experiences of the closeness or presence of God, in the situation described by their movement patterns?

While doing a kinesic analysis of the movements in the story of Gerald of Wales—which I attempt to do in the first part of this article—is an essential addition to scholarship dealing with dance, it also has its limits. As Rebecca Straple-Sovers and many others have pointed out, experiences of emotions, sensations and the worldviews that one encounters in medieval sources were most probably completely different to what we may experience in our time and age.26 Thus, applying a full archaeology of the senses approach to the story of dancing at St. Eluned’s feast day is beyond the current project. Robin Skeates and Jo Day write in The Routledge Handbook of Sensory Archaeology (2020) about the need to use and explore methods such as critique, reflexivity, incorporation, ethnographic insights and analogies, direct experience, experimentation and reconstruction, imagination and artistic creativity, evocation and empathy when approaching historical materials.27 A satisfactory account of the event incorporating these aspects would require much more space than what this article may offer. However, in gathering materials for this study, I did visit the places where St. Eluned is said to have passed through before her death. Thus, the latter part of this article will also include some kinesic analysis of the actual sites of pilgrimage, and my own movements in this particular space. In this manner, this article, with its hermeneutics of suspicion and charity and the kinesic analysis of the story of St. Eluned, introduces a new kind of multi-method exploration, while its main focus is on the critique of the use of the term liminality in previous research dealing with this specific story.

3. Dance and Theories of Liminality

The term liminal was first coined by Arnold Van Gennep, a folklorist writing about Rites de Passage, 1909 (Van Gennep 2013). The main idea of this term is that, in ritual passages from one state of being to another, there might be an in-between stage characterized by chaos or even destruction. At this threshold, behaviors, practices and modes of being under “normal” circumstances, that would not be accepted or perceived as distressful, are now given space as a path of transition or change.28 In many of dance historian Gregor Rohmann’s works, on exploring potential Christian modes of dancing in the early church and medieval period, this mode of relating to liminality plays a big role in his interpretations.29

After Van Gennep, the concept was picked up by anthropologist Victor Turner when, in 1967, he included an essay, “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage”, in his book The Forest of Symbols.30 In short, the theoretical discussion about liminality is formed around questions of both time and space. The scale of usage can also vary from describing an individual’s life to small community groups, or sometimes encompassing whole societies and eras. This means that the term liminal has been widely used in describing moments, everything from abrupt events like death, illness and divorce, to specific rituals of passage. It has also been used to express longer passages of time, for example, periods of distress like war, famine or plague.31 Furthermore, the term has been used for a specific “type” of people in a community, like a holy person, non-able-bodied individuals or holy fools, like St. Francis.32 Finally, the concept has gained a stronghold in describing specific places and spaces. These may vary from borders of different types, holy wells, trees, or parts of a landscape, to areas like a graveyard or crossroads between life and death, and health and sickness, as the space of a relic or sauna may form.33

Theologically speaking, Peter Brown, in his The Cult of the Saints—Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity (Brown 1981), is one of those authors who used Victor Turner’s ideas about liminality to describe what happened at the shrines of the saints, as well as through the pilgrimage processions to graveyards or other holy sites, in the early church period.34 He writes:

Christians who trooped out, on ever more frequent and clearly defined occasions as the fourth century progressed, experienced in a mercifully untaxing form the thrill of passing an invisible frontier: they left a world of highly explicit structures for a “liminal” state.35

The walking out of the rigid structures of a city landscape and ordered society opened the way for entering a space where a new kind of community could be built, and where behavior that otherwise could be characterized as unruly, or inappropriate, could be unleashed.36 In Brown’s understanding, the shrines of saints were not just places where exorcism and other potentially unsettling practices could occur. They were also spaces where the potentia and praesentia of the divine—mediated by the relic—could transform the social status of individuals and the norms prevalent in society.37

Not only Gregor Rohmann, but also Nancy Mandeville Caciola has used at least part of this terminology to understand the dancing of the medieval period. They have looked at the dances that took place at the pilgrimage sites of St. Vitus and St. John, the famous “Dance Mania” starting in Kölbick around 1017/21, and the account of frenzied dancing described by Gerald of Wales in Itinerarium Cambriae.38 The implicit starting point in these authors’ writings seems to be that dancing is somehow problematic and needs to be explained, and that a dancing saint is out of the norm.39 Liminality is then used to describe how we can make sense of the dancing found in these events. Both Rohmann and Caciola refer mainly to the space of the graveyard and the body (as an ambiguous entity) as a liminal place where dancing could happen.40

Very few dance scholars or medieval historians use Brown’s terminology of potentia and praesentia to explain how we might understand the importance of this kind of dancing to the community, or as a phenomenon with a theological significance. The exception to this rule is Caroline Walker Bynum. In Wonderful Blood—Theology and Practice in Late Medieval Northern Germany and Beyond (Bynum 2007), she brings forth the idea that ambivalent practices—a category in which I include more chaotic forms of dancing—could also have played a part in the activation of the relic.41 In her depictions, just like those brought forth by Brown and Caciola, the relics did not facilitate miracles on a continuous basis. Instead, the birth, death and translation days of relics, in combination with an interactive component of the gathered community, were key in creating a situation where the potentia of the saint became visible to the community.42 In combining Peter Brown’s and Caroline Walker Bynum’s descriptions of what happened at pilgrimage sites and shrines of saints, dancing could play a part in activating a relic and displaying a saint’s praesentia at the site.43 Finally, dancing in combination with healing could further be understood as a sign of the potential of the saint.44 To exemplify, I turn to the description of the feast of St. Eluned.

4. Gerald of Wales and the Itinerarium Cambriae

The Itinerarium Cambriae is described as the eyewitness account by Gerald of Wales (1146–1223), derived from his tour through Wales.45 It can be read as somewhat akin to a diary of an ethnographical expedition.46 Carl S. Watkins, in History and the Supernatural in Medieval England (Watkins 2007), claims that Gerald of Wales was often unsympathetic to the Welsh culture, which he frequently portrayed as uncouth, barbarous and alien.47 Geraldine Heng further explains that Gerald of Wales was particularly ruthless towards the Irish. Describing them, based on their pastoral living and economic practices, as uncivilized, backward and lacking in morals. With the lack of any physiological or even religious differences between the Irish and the English, Gerald of Wales took to the depictions of customs, cultural norms and manners to depict why the English needed to take initiative in this part of the world. He further positioned himself as a leader of the project of bringing the Irish towards evolutionary improvement and instruction.48

In another of his works, the exempla or Gemma Ecclesiastica, Gerald of Wales focused on giving instructions to the clergy.49 Watkins argues that Gerald’s accounts were clearly written with an eye on Rome, and a hope to curry favor in his battle for the bishopric of St. Davids.50 In the Gemma Ecclesiastica, Gerald devotes a whole chapter to speaking against the dancing and singing of vulgar songs in churches and cemeteries.51 He refers to the Councils of Toledo, which stated that dancing and singing during feast days of the saints should be abandoned for the sake of participation in the divine office. He further declares that it is the task of the priests and judges to make sure this is implemented.52 He then continues by presumably quoting St Augustine, who stated that the interior part of the church, the oratory, was named so, because it was for the purpose of prayer (ora = prayer), nothing else.53 Based on these accounts, it seems that Gerald of Wales was a person who, if he found problematic aspects of lived Christian faith amongst the people he met, was bound to report them. He also seemed more than willing to explain what he, as a guardian of the Church, had to offer in correcting such behavior.

It is due to these depictions that it is interesting to see that when he turned to the Itinerarium Cambriae and its description of the feast of St. Eluned, his account lacks a condemning attitude towards singing and dancing.54 Even though the description is one of rural practices and dancing in the cemetery, his concerns about problematic behavior from the laity during the feast day of the saint, are missing. Something else was at stake in this story. Let us now turn to an in-depth reading of Gerald of Wales’s writing about the celebrations of St. Eluned’s feast day, from what may have been 1 August, around the year 1190.55

In Butler’s Lives of the Saints (Butler 1981), Herbert J. Thurston and Donald Attwater write that Gerald of Wales was an archdeacon of the city of Brecon from 1175. Furthermore, he lived for over 20 years in Llanddew, only a few miles away from the shrine of St. Eluned, making both the region and the feast a space and place he would potentially have visited several times.56 In Gerald’s account, he first explains the scenery of where the feast of St. Eluned is placed.

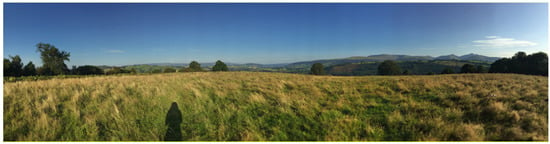

Below is a picture of the space outside of Brecon (which I visited 24 September 2019) in Slwch Tump, which is described as the setting of St. Eluned’s shrine (see Figure 1).57

Figure 1.

A picture of the space outside of Brecon in Slwch Tump, which is described as the setting of St. Eluned’s shrine.

The shrine of St. Eluned was destroyed in 1698, and almost no traces of worship can be found on the spot today.58 A pilgrimage map is provided, but I have found no traces of revival of these practices in the region.59 Thus, to learn more about this tradition, we refer to text by Gerald of Wales:

A powerful and noble personage, by name Brachanus, was in ancient times the ruler of the province of Brecheinoc, and from him it derived this name. The British histories testify that he had four- and -twenty daughters, all of whom, dedicated from their youth to religious observances, happily ended their lives in sanctity. There are many churches in Wales distinguished by their names, one of which, situated on the summit of a hill, near Brecheinoc, and not far from the castle of Aberhodni, is called the church of St. Almedda, after the name of the Holy virgin, who, refusing there the hand of an earthly spouse, married the Eternal King, and triumphed in a happy martyrdom.60

At first, we get to know in which part of the country the account is situated. Gerald of Wales also tells us that this particular region has a long history of Christian rule. The province of Brecheinoc is a sanctified area. This can be understood in two ways: firstly, that the king living and reigning there can produce holy women as his offspring, and secondly, that the grounds of this region had been transformed through the presence of many churches.61 The particular church Gerald of Wales introduces to his listeners is guarded by a Holy virgin: St. Almedda. Also known as St. Eluned or Aluned, she was not only a virgin but, as the story goes, was martyred due to her quest of wanting to give her life to Christ.62 Peter Brown has written extensively on the topic of how females in the early church gained both authority and freedom to break with patriarchal gender norms by rejecting the ordinary life of procreation for a life with Christ.63 Caroline Walker Bynum further explains that, similar to chastity for men, virginity for women was almost a precondition for sanctity in the medieval period.64 The text further emphasizes that Eluned was murdered in the act of protecting her chosen life of holiness.65 This emphasis on martyrdom brings in an even stronger focus on the fact that hers was a life of sanctity and, thus, she had the ability to bring healing to others.66 Similar stories identified in Butler’s Lives of The Saints, further show that it was the task of the whole community to protect this kind of female vulnerability. If the community did not stand up to protect the holy woman who fled from matrimony into the arms of Christ, the space itself was cursed.67 Clearly, the scenery is set to show the Glory of God in the region Gerald of Wales had entered.

The account of Gerald of Wales continues to explain how the feast he encountered was celebrated:

[St. Almedda] to whose honour a solemn feast is annually held on the first day of August. On that day, a large concourse of people from a considerable distance make their attendance, and those persons who labour under various diseases, through the merits of the blessed virgin, receive their wished-for health. What, for me appears remarkable, is that at almost every anniversary of this virgin, similar events as these occur. You may see men or girls, now in the church, now in the cemetery, now in the dance, which is led round the churchyard with songs, on a sudden falling on the ground in ecstasy and silence, then jumping up as in a frenzy, and representing with their hands and feet, before the people, whatever work they have unlawfully done on feast days.68

What Gerald of Wales sees, presumably not just once as a curious exotic trait of his journey, but every year at the anniversary of the saint, he finds remarkable. People attend this feast from afar and are given healing for various diseases. One tenet of the hermeneutics of suspicion and charity is not to disregard aspects of lived religion and religious experiences of people living in another time and age than our own. This means that hagiographic materials and the depictions of the laity’s worship practices are considered theologically relevant materials for discussion.69 As Peter Brown has argued, particularly the cult of the saints incorporated many rowdy forms of practice that had become popular with the populous at the feasts of the martyrs, even when they were frowned upon by certain Church fathers. The experiences labelled as rustic or “vulgar” (both in ancient times and later overlooked by scholars) were even incorporated into the official liturgies of the Church.70 As a continuation of this idea, I argue that dance historians need to become more nuanced in how they read and use texts by Church authorities. Too often, it is taken for granted that the Church condemned all forms of dancing, and then the depictions that are found of dancing are portrayed from the point of view of resistance.71 Instead of looking into particular circumstances and nuances in the details of a story—as I attempt to do here—the diversity and multiplicity of understandings are lost.72

Contrary to the arguments that take for granted that dancing was forbidden in Church contexts, Gerald of Wales does not describe the dancing in Itinerarium Cambriae as problematic. Even when this kind of dancing leads to ecstasy and frenzy—potentially moving away from the pattern of sacred and highly organized dance movements—he does not judge the behavior of the dancers.73 Even though elements of this specific event may fall outside of the “norm” of an anniversary of a saint, he finds them remarkable, rather than condemnable.

I find it particularly important to note that Gerald of Wales does not portray the singing and dancing described here as possession of an unclean spiritus.74 In recent scholarship, when depictions of dancing are brought forth as part of the celebrations of saints, scholars tend to immediately assume that they are situations of possession.75 Contrary to such understandings, Gerald of Wales’s attitude here seems to instead depict Church leadership that understands that the potential and praesentia of a saint—when following the strict setup of ritual practices during a festivity—may have remarkable consequences, and do not necessarily indicate demonic activity.76 The description of healings and dedication to the Blessed Virgin show another way of understanding the dancing, which I return to shortly. At this point, I mainly want to highlight the need for reading accounts like that of Gerald of Wales with a hermeneutics of suspicion towards dominant interpretations in secondary scholarship around dancing in and around churches in medieval Europe.

Kinesically, the description opens with a long row of people mixed across gender and age lines. This depiction breaks with the “normal” patterns of how church processions are to be conducted and what the rules of behavior between the sexes are expected to look like.77 Such breaking of traditional social roles is precisely what Brown speaks of when entering the liminal space, not only of a cemetery or through a pilgrimage to a shrine (both seem to be the case in this event). Particularly, Nancy Caciola’s reading of this account emphasizes the importance of the cemetery as a liminal space, where encounters with the dead could be mediated through dancing.78 In addition to such a view, I would argue that the possible liminality of this event lies in the fact that this is the feast day and liturgical period, when this particular saint would bring forth her praesentia.79 Brown’s account of how the festivities of the saints opened up for a “time out of time” could be one way of understanding why Gerald of Wales did not choose to condemn this particular practice of dancing.

Secondly, the long row of people winding their way in and out of the church and churchyard, and finally creating a round dance encircling (circumfertur) the cemetery, kinesically opens the possibility that, at the beginning of this celebration, the dancing and singing might have been more organized. In Gerald of Wales’s condemnation of dancing in Gemma Ecclesiastica, he adds an exempla, where he explains that the problem with dancing on feast days was that the singing and the movements could distract the priest.80 This is tied to the idea that if the priest made an error in the rite, it jeopardized the well-being of the whole community.81 If we instead entertain the idea that this particular feast was one where the dancing was part of the ritual, such challenges for the priests would disappear. A small indication of the possibility of interpreting Gerald of Wales’s writing in this way is the nuanced differences he uses in describing the singing. The word used for songs in Itinerarium Cambriae is cantilena. Watkins translates it as “traditional songs”.82 However, the term cantilena indicates a vocal song and has many usages, among which dance-songs, sacred songs and love songs can be found.83 More importantly though, when Gerald of Wales condemns the singing on feast days in Gemma Ecclesiastica, he describes them as bad singing (mala canentes), referring to particular kinds of songs that were not appropriate. In contrast to this, in Itinerarium Cambriae he writes about dancing and singing without any indication of which kind, leaving the option that this is a completely approved form of singing for such an occasion.84

Furthermore, kinesically, the movements in the first part of the dance may suggest a more systematic form. There is no description indicating if the people are holding hands or not. Still, there may have been some synchronicity to these movements. Dancing and singing in a line and creating different formations are known from many folk-dance celebrations and depictions in Church art. The most famous of these are the two paintings by Fra Angelico from a completely different time and place than the feast of St. Eluned.85 The visual of such a painting may assist us in seeing and sensing how more organized and worshipful movements would look like in the imagination of a medieval person (see Figure 2).

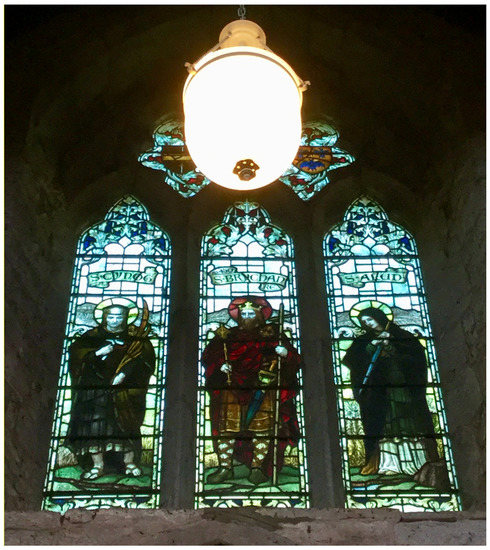

Figure 2.

Fra Angelico was commissioned to do two different The Last Judgement altarpieces. This image shows parts of the piece which was commissioned for the Camaldolese Order (1425–1430) and is situated in Florence, Italy.

Part of Fra Angelico’s The Last Judgement, commissioned for the Camaldolese Order (1425–1430), situated in Florence, Italy, depicts dancing in a long line through a garden. The movements start from the crowd of people being saved at the Last Judgement and move forward towards the heavenly gates of New Jerusalem by holding hands and dancing.

Another point of kinesic depiction in this passage is that the movements flow between a long line dance into the circle format. If there were enough people participating in the event, such a circle dance could have encompassed the whole shrine. Also, this type of dancing is found in artistic depictions. For a comparison between the two different forms, see the following two images (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The image to the right is The Annunciation to the Shepherds by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook or workshop, from about 1480–1515. The image to the left is The Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Rothschild Prayerbook 20, compiled between 1505–1510.

The image to the right is The Annunciation to the Shepherds by the Master of the Dresden Prayerbook or workshop, from about 1480–1515.86 In this image, the male and female shepherds hold hands and dance in a circle. The image to the left is The Annunciation to the Shepherds in the Rothschild Prayerbook 20, compiled between 1505–1510.87 In this image, the men and women form a long line of dancers similar to the saints and angels in the Fra Angelico painting.

As these images show, the concept of mixed-gender dancing, particularly in rural settings, is not foreign to religious art from the medieval period. Even when the recommendations by church leadership would have opted for forbidding mixed-gender dancing, these kinds of images found their way into prayer books depicting worship during a liturgically important event of the year.88 Thus, I suggest that imagining a more worshipful form of communal dancing during the particular feast we examine in this article should not be ruled out.

Comparing the kinesic descriptions in Gerald of Wales’s story with the images found in the Book of Hours of the Altarpieces, from 400 years later and in a different region of Europe, there is reason to bring in some hermeneutics of suspicion towards the kinds of conclusions that can be made. There are, for example, aesthetic and practical reasons for why a depiction of dancing would be created in a line in the margins of the Book of Hours, while full-page pictures would more likely be depicted as a circle formation. So, while images in artwork cannot prove practices in the field, A. William Smith in Picturing Performance (Smith 1999) argues that it is unreasonable to suggest that depictions of dancing in paintings carry no bearing to something the artist has experienced and used as a model for their work.89 Thus, I find it relevant to bring in a hermeneutics of charity and ask: could the first part of the depiction of the feast day of St. Eluned have been a worshipful initiation, or even a prayerful opening of the festivity? When we see that peasant and mixed-gender dancing are options for depicting prayerful worship in the Books of Hours, maybe it could have also been a practice that people embraced during a saint’s feast? In the continuation of the story, we find further reasons for such a reading.

After the winding dance, Gerald of Wales describes that something abruptly happens (subito in terram corruere).90 It is, of course, possible to understand the sentence to mean that the falling down and jumping up in a frenzy occur the whole time, while people are moving around on the cemetery grounds. Some earlier interpretations and translations that opt for the word trance in this section seem to lean towards this understanding.91 There is much to say about such an interpretation.92 However, this article format does not give room for all of those discussions. Rather, I want to focus on a reading based on the kinesic understanding described here, which has not been explored in previous scholarship.

Instead of perceiving the movements as all packed together in an ongoing continuum, we may pick out the details described by Gerald of Wales, and another reading opens up. He states that people suddenly fall to the ground. Reading this kinesically suggests a shift in the bodies and their movements. It is from a previous and different kind of motion that the bodies suddenly fall to the ground. What I thus perceive is a sequence of very different types of movements following each other. First, there is one kind of dancing, and then there is the falling. Furthermore, the exact Latin words used for what follows are: extasim ductos et quietos.93 Therefore, I have not opted for the usage of language that refers to a trance, but instead, I have translated the passage in terms of ecstasy and silence. Shifting from singing and dancing in a pattern that encircled the churchyard to first falling, and then movements of ecstasy and silence, signifies several shifts in bodily tension and movement patterns. Yet, nothing indicates that this needs to be a trance.

Theologically speaking, ecstasy also signifies something different then trance. Ecstasy may occur when the Holy Spirit falls upon people.94 Interestingly, it is this exact pattern that is described in Gerald of Wales’s account. The dancers fall to the ground and then rise up in ecstasy and silence. Ecstatic forms of prayer are not foreign to certain schools of Christian contemplative prayer.95 In his De Poenitentia, Ambrosius of Milan references events in St. Paul’s life as dancing in the Spirit.96 Also, medieval teachers of the Church have continued to speak about forms of prayer where the soul and body co-operate in a way that may lead to extasis or excessus mentis, which is an event where one moves out of the bounds of normal bodily being.97 There are, thus, significant cues in Christian traditions to interpret the dance of the feast of St. Eluned as a situation of worship where people are affected by the Holy Spirit. The bodily gestures described by Gerald of Wales of what might be happening do not fall out of context, and they are not automatically condemnable. His descriptions further indicate why this is not a situation of possession by an evil spirit that is then cleansed by the saintly praesentia. Instead, the movement vocabulary shows prayerful invocations that lead to the arrival of the Holy Spirit.98

It is only after this passage of ecstasy and silence that Gerald of Wales describes a sense of frenzy (phreneaim raptos). Kinesically, the progression goes from dancing and singing to falling and reaching an ecstatic silence. Immediately after this, people move into rapture and leaping up to represent different movements.99 Instead of being in a continued state of trance, there is a clear progression with various movement patterns ending in rapture. Kathryn Dickason points out that the terminology of rapture had a very broad set of meanings in the medieval period. It could range from abduction and seizure to ravishment and rape.100 However, both Dickason and those she builds her argument upon seem to have overlooked that rapture of a spiritual sort, just like prophecy, induced by singing and playing music, are also part of the stories of the Bible.101 Not only did David leap up and dance in front of the Ark, but King Saul fell into a frenzy when the Spirit came upon him in his anointment to become the new king.102 Furthermore, as already indicated in Ambrosius of Milan’s writing, the Apostle Paul speaks about being seized by the Spirit and transported to an altered state of consciousness in his letter to the Corinthians.103 That passage is sometimes referred to as a rapture, not only ecstasy.104 These examples show that the idea of worshipfully engaging in music and dancing, which leads to the arrival of the Holy Spirit and movement patterns of people taking an extraordinary form, could very well be part of something Gerald of Wales found remarkable, even a blessing! Once the Holy Spirit, also called a Spirit of Truth,105 arrives, we see that Gerald of Wales interprets this as a moment where earlier hidden aspects of people’s lives are revealed in the movements they leap up to represent.106

Let us now move to the next section of the story, which depicts what happens in more detail, once what may have been the Holy Spirit appears on the scene:

…you may see one man put his hand to the plough, and another, as it were, goad on the oxen, mitigating their sense of labour, by the usual rude song: one man imitating the profession of a shoemaker; another, that of a tanner. Now you may see a girl with a distaff, drawing out the thread, and winding it again on the spindle; another walking, and arranging the threads for the web; another, as it were, throwing the shuttle, and seeming to weave. On being brought into the church, and led up to the altar with their oblations, you will be astonished to see them suddenly awakened, and coming to themselves. Thus, by the divine mercy, which rejoices in the conversion, not in the death, of sinners, many persons from the conviction of their senses, are on these feast days corrected and mended.107

Kinesically analyzing this passage, one can sense a whole range of gestures pertaining to the agricultural tasks and labor of the populous portrayed. The tasks described are gendered, with work related to men first and those of women or girls coming later. In a note, we can also read that the rude song referred to may have been a Welsh ploughing song, that made the work of both oxen and men more rhythmic.108 Gerald of Wales further explains that these gestures are brought to the altar as an oblation or offering (oblationibus). Once the people arrive inside the church, they suddenly awaken and come to themselves.

Finally, he also writes that those who took part in this gesturing, and those who have seen and heard (vivendo quam sentiendo) what occurred, correct their way and are mended. This last part is quite tricky to translate as the word ultionem, deriving from ultio, may indicate everything from avenge, revenge and punishment to indulgence.109 It is unclear if the text refers to setting free those who had indulged in their sensory experiences, meaning, “whatever work they have unlawfully done on feast days”, or that they were set free by taking part in the gesturing. Another plausible explanation can be derived by considering those watching the gesturing. Was it their indulgence in seeing and hearing the gestures that freed them from the punishment that otherwise would have fallen upon them?

Carl S. Watkins is one of few authors who goes into a lengthier discussion on how to understand this passage based on the whole account. He states that what is acted out in this situation is a local response to the Church’s teaching about sacred time and sin. He suggests that the members of this community had absorbed the idea that working on feast days was sinful. Through their movements, they signaled that they were nevertheless averse to this teaching, and thus perhaps pressured to seek absolution. As there were no readily fulfilling penances, local rituals had emerged to lighten the lot of post-mortem punishment. Watkins concludes this is a ritualized re-enactment of the sin and seeking intercession with the saint.110

Watkins seems to come to this conclusion based on three different clues. First, he sees that Gerald of Wales approved the ritual as “appropriate”. The approval is shown through the priest being placed at the heart of the ritual, dispensing absolution at the altar rail to all those who had participated in the rite.111 This is an interesting understanding, as the text does not speak about priests meeting the afflicted people at the altar. It only states that people were “brought into the church and led up to the altar with their oblations or offerings”.112 Kinesically, the text offers another possibility: the worshipers present at the shrine assist the afflicted people in entering into the space where St. Eluned showed her praesentia and potentia. Invoking the praesentia and potential of the saint alone is what brings people back to their senses.

In some biblical passages, such as 2 Timothy 2:15, Colossians 1:21–23 and Romans 12:1–2, it is claimed that a sinner is only required to present themselves in front of God to receive forgiveness and new life.113 There is a link between sins leading to death in these biblical examples, but there is no mention of post-mortem punishment. Instead, worshipfully presenting one’s body in front of God is a practice that needs to be renewed repeatedly.114 Furthermore, such an offering for the absolution of a particular sin does not require a priestly presence. At the same time, Brown tells us that accounts of healing at the shrines of the saints are always a communal act.115 From this point of view, presuming priestly guidance on this occasion may be apropos. Nonetheless, it is crucial to notice that nothing is said about exactly how the offerings of the dancers were met, or by whom.

Watkins’s second point emphasizes Gerald’s explanation of sin being at the core of this ritual.116 At the end of the account, Watkins takes the statement, “God in mercy does not delight in the death of a sinner, but in his repentance: and so, by taking part in these festivities, many at once see and feel in their hearts the remission of their sins, and are absolved and pardoned”,117 as a key moment for understanding the ritual. He reads this as pinpointing that not God alone, but the priest too, should have an attitude of forgiveness towards sinners. Furthermore, it seems to be the statement about death which leads Watkins to speak about a ritual for absolution from post-mortem punishment. Even though asserting a link between sin and death is understandable, I do not entirely agree with the amount of emphasis Watkins places on post-mortem fear. He writes that there was much preaching concerning the need to make “full satisfaction” for one’s sins in this specific period.118 Yet, as preachings on purgatory and an equal emphasis on the punishments of hell were only emerging at this time, I find this statement somewhat arbitrary.119

Instead, one could read the account as a more general question about healing and re-entry into the community. Those who were healed, when participating in the ritual of the feast day of St. Eluned, were not only those who had sinned against the Sabbath rest by working. In the beginning, it is stated that “persons who labour under various diseases, through the merits of the Blessed Virgin, received their wished-for health”.120 This opens up the possibility that the healings were from many other afflictions, not only those related to the suggested actions breaking God’s commandment of rest. Brown has argued that the festivities of a saint day celebration were periods when God’s acceptance of the whole community could be sensed and seen by bringing disparate members together.121 Speaking about the miracles that happened during the festival of Saint Martin, he states:

The barriers that had held the individual back from the consensus omnium were removed. “With all the people looking on,” the crippled walk up to receive the Eucharist. The prisoners in the lockhouse roar in chorus to be allowed to take part in the procession, and the sudden breaking of their chains makes plain the amnesty of the saint.122

So, even when ecstatic dancing, frenzied movements and gesturing may have been expressions shown only in the bodies of a few members of the congregation, the whole community was affected by what they saw and experienced. One could also take part in the miracle and in the celebration of the mercy of God as an onlooker. This renewal of communal membership through the yearly festivals were a praxis that created solidarity and communion between people from different social classes and positions.123

I find the final point that Watkins makes to be very relevant, though for a slightly different reason than he does. He makes a more general note about the 11th and 12th centuries being a period during which local customs could be particular and specific. On one hand, Watkins writes that “universal” teachings of the Church on questions of penance, the eucharist, good works and last things were still being formalized by both monks and scholars. However, there was no existing structure explaining exactly what the unified body of the official teachings of the Church would be. At local parish levels, the community identified themselves with their local priest and the community gathering for worship. This meant that there could have been specific rituals that were developed in one particular community and practiced only there.124

Vincent Lloyd explains that rituals are actions that reinforce social norms.125 He writes: “Ritual is understood as a community practice, reflecting or growing out of social norms”.126 This local practice could thus have been something that Gerald of Wales found worthy of promoting. It bound the community together and taught the people who arrived at the feast of St. Eluned important lessons about Church teaching. The way that Gerald of Wales describes this event indicates a ritual that showed God’s mighty praesentia and the merciful acceptance of those who chose to present themselves under the Church authorities. In such a view, the ritual itself created what Rohmann calls the liminal space of being in between perdition and salvation.127 Dancing—with its ambivalent status—appears in such a story as an indicator of liminality, or the consequence of liminality. When emphasizing the idea of specific and local rituals as an expression of religious life in the early medieval period, dancing and frenzied gesturing—on their account of being indicators of liminality—are not threats to the Church authorities. Instead, they become tools that can be used to bring people together. Thus, reading the account of Gerald of Wales with liminality as a theoretical starting point is one way to understand why he did not condemn the practices, and why the community was allowed to celebrate their saint in a manner where singing and dancing were part of the yearly festivities.

Choosing this route limits one’s understanding of the Church and Christianity to a male and patriarchal structure. It also strengthens a tradition that is built on reinforcing norms and upholding hegemony.128 Such an option is not the only path forward. Thus, the second part of this article turns to the vital critique of liminality presented by Caroline Walker Bynum.

5. Whose Story? The Critique of Liminality

Watkins introduced the idea of reading the account of Gerald of Wales as a local and “place-bound” practice. This raises the question of what stories we accept as the most important narratives for understanding this dancing event? Are we looking towards theological or philosophical expertise at the educational centers of Europe to understand the praxis, or do we turn to the less known manuscripts of local writers? As scholars and interpreters, do we center the more subtle voices of practitioners and laity found in artwork, praxis, legends and unofficial records or certain textual statements by Church authorities in the region? Watkins presents these challenges when he speaks about the differences in understanding that arise if one listens to cloistered teachers, such as Abbot Ailred, and compares his statements to those of a leader of the local priests, like Gerald of Wales.129 Simultaneously, these approaches center on male voices and more educated people. More importantly, they often take the elite male experiences as an implicit norm for all expressions of living in a Christian tradition. What would happen if we instead looked at the dancing from the point of view of the laity, and the women who took part in the dancing? These questions, and the critique of liminality that Caroline Walker Bynum has expressed, go hand in hand. In this second part of the article, I place the description of Gerald of Wales, as well as the readings of it by Carl S. Watkins, in the foreground and adopt a less text-bound approach towards the feast of St. Eluned and her followers.

In her Fragmentation and Redemption (Bynum 1991), Walker Bynum explains that a challenge with Turner’s theory on liminality is that its emphasis on reversal and elevation only makes sense in a world of hierarchies, and for those individuals (male, aristocratic and educated elites) who have the real possibility of climbing a social ladder. In short, Walker Bynum explains that Turner’s ideas about social dramas could be read—in the episodes of a single saint’s life—as a succession story from “ordinary” life to a “conversion” event where the (male) person passes, either through reversal (turning into woman, bestial or fool) or inversion (claiming poverty or female subjugation), into a climactic episode at which reintegration happens, and then, the individual lands in a new state of being. In the example of a dominant symbol, the idea of reversal or inversion happens when a person takes part in a ritual action that questions the dominant structure. The dominant symbol supports a person in their transformation and elevates them from one status to another.130 However, the prerequisite for this is that the person has the freedom to move between different forms of status, or that there actually is a kind of divine intervention which changes reality.

In contrast, Walker Bynum’s research on females in the medieval period shows that these social dramas and conversion patterns, or dramatic changes, cannot be found. Instead, her investigations of stories about women (especially when told by women) describe patterns of continuity and the deepening or enhancing of an experience. She further argues that when stories, where the experiences of laity or women are not immediately perceived as liminal, are examined with the experiences of these people in mind, something else than liminality comes to view. What may have been a release or escape from ordinary life for those in a status position, is not so with those who are powerless. Instead of voluntary poverty, weakness, or nudity in the process of imitatio Christi for a privileged person, the unprivileged individual does not turn to wealth, strength, or splendor in describing their process (as a reversal), but to a path of continuous struggle.131

From the male-dominant point of view, following Walker Bynum’s analysis, the pilgrimage to St. Eluned’s shrine provided ample opportunity to release societal structures and live in a “time out of time”. In the eyes of a male clerk like Gerald of Wales, the partaking in frenzied dancing may very well have shown the power of a female saint and intimate interaction with a(n idealized) Virgin, which Walker Bynum explains to be characteristic of many medieval males seeking a mystical path. Finally, the story of St. Eluned’s life, framed in the telling of Gerald of Wales, is one of “high” romance: she has to die violently to become united with her beloved Christ.132 What appears if we turn to the daughter of Brachanus herself, or the community of worshippers around her? How would they have expressed their understanding of what happened in the dancing? Does the dancing create a different kind of theology?

One of the ways to go about this is to turn away from Gerald of Wales’s focus on sin and redemption and read with suspicion what can be found “between the lines” about the female characters of the story.133 The first relevant passage for such a reading is: “The British histories testify that he had four and twenty daughters, all of whom, dedicated from their youth to religious observances, happily ended their lives in sanctity”.134 Even though this statement was not penned by the hand of a woman, it does testify to Eluned not being a lone woman. She had a community of sisters around her. Using the hermeneutics of suspicion towards dominant male descriptions, and looking with a hermeneutics of charity for the lived religion of the women in the story, another possible perspective of this feast day is visible.

The text continues by explaining that Eluned refused the hand of an earthly spouse. From this small detail it is plausible to imagine that Eluned, like so many other medieval women, experienced her relationship to Christ from the point of view of being his bride. Walker Bynum explains:

Medieval women, like men, chose to speak of themselves as brides, mothers and sisters of Christ. But to women this was an accepting and continuing of what they were; to men, it was reversal. Indeed, all women’s central images turn out to be continuities.135

Being the bride of Christ displayed the sense of continuity already mentioned where, for females, the active engagement with God did not turn their world upside down. Instead, they continued as women in undertaking very female tasks (being sisters, mothers and spouses). Further, Walker Bynum affirms that the image of a bride or lover of Christ was not one of passivity, but rather an idea of an active involvement and a very sensual engagement with God.136 We do not know how Eluned experienced her sense of belonging to Christ, but the account does tell us that she was ready to break the worldly marriage engagement her father had made on her behalf and flee from the safety of her home.

Furthermore, Eluned was not alone in this experience of leaving the “worldly” life of marriage and caring for children in order to hide out and “elope” with Christ as her bridegroom. Both Jane Cartwright and Liz Herbert McAvoy argue that some of Eluned’s sisters lived anchorite lives.137 In Anchorites, Wombs and Tombs—Intersections of Gender and Enclosure in the Middle Ages by McAvoy and Hughes-Edwards (2005), it is described that choosing the anchorite life of seclusion and solitary prayer seems to have been a very popular option for women, especially in the context of the British Isles.138

The work of McAvoy and Hughes-Edwards traces the development of a solitary life from the Desert Mothers and Fathers of the early Church into the Middle Ages. It particularly looks into the phenomena that developed and guidebooks written for men and women in a Northern European medieval context.139 The study shows that the first written document of a guide for those who wanted to choose the solitary life in an English context already existed in 1080.140 This means that during the time of the written description of Gerald of Wales, the tradition of female recluses was already established in the proximity of this region. It further means that even though there is no written record of the Achrene Wisse or a similar text found in Welsh, the path of an anchorite life might have still been a possible strategy for Eluned. More specifically though, reading about Eluned’s life would have been a story that created associations to an anchorite life in others.141

McAvoy and Hughes-Edwards describe that, even though the idea of an anchorite developed out of the mix of the image of a monk withdrawing into the desert in search of a solitary life, and the suffering of the more urban martyrs, the anchorites and hermits of Northern Europe were an entity in their own right. The hermit, according to Herbert McAvoy and Hughes-Edwards, developed from the idea of withdrawal into a solitary life of prayer and seclusion. In the consequent Northern European tradition, however, this came to indicate a person who was ideologically solitary and, nonetheless, free to move about physically. The anchorite, in contrast, was a person who chose to withdraw from the world, but this withdrawal could be achieved in a solitary form or in a community with others.142 In the Northern European tradition this came to indicate a person who found their place in the “bleak and isolated islands, wild, impenetrable forests, perilous, boggy marshlands”.143 Thus, the main difference here was that these individuals were confined to a stationary, fixed position.144 At the same time, such a life did not always mean seclusion from other people and communities. The female anchorites, in particular, often tended to have a rich life of social connections, with people visiting them, engaging with their teaching and spiritual guidance. Sometimes they even rose to prominent political positions in their society.145 Thus, when we read that St. Eluned chose a life of hiding, as the bride of Christ, this should not be understood as an insignificant step into isolation. She just as well may have been aspiring for a space of prayer and seclusion—a deepening of her life with Christ—while simultaneously enhancing her status as the daughter of a prominent leader. This kind of contextualization of St. Eluned’s life, and her community of females in the region, is more important than what might be clear at first glance. It brings the depiction of the feast of Eluned away from the focus on a ritual, where Church authorities have the last say in how the celebrations evolve. Instead, we may be looking at a female role model who spoke to women and laity in the local community, and strengthened the personal connections between individuals and the experiences of the divine.146

When I visited Brecon, I learnt that the Cathedral Church of St. John has also been in connection with a Benedictine priory.147 In their story of themselves, they state that Eluned visited the monks in their community before heading up to the hill, where she was murdered. It is stated that these brothers offered her shelter. She received their kind offering. Yet, after some time, she continued her journey and was subsequently found by her suitor. We will probably never know why she did not stay with the brothers in the priory, or why she continued up into the countryside. Could she have been looking for this more solitary form of life? Her story allows for the possibility of reading her life as a devotion, and that she did not want to give in to the patriarchal structures of the normal society. This is not a climbing of a social ladder, nor is it a transformation of one’s position, but a constant struggle with the dominant powers of oppression.

Vincent Lloyd tells us that the life of sanctity is an ambivalent path. On one hand, the political potential of sanctity lies in acting as if there are no norms.148 The choice of breaking with the norms of what was expected of a woman and fleeing into the arms of Christ may have been a strong statement of walking on an unthreaded path. Sanctity as a strategy may act to break the hegemony of the visible.149

On the other hand, when one makes sanctity into a lifestyle, it inevitably gives rise to norms. It tethers the plane of practices to the norms.150 This is why it becomes problematic when we only read the stories about female saints penned by male authors in the Church. What once may have been a strategic path of breaking norms is quickly turned into a new hegemony of expected behavior. Still, there are ways to unearth the female voices and find how their stories differ from that of the male practices.

Jane Cartwright, in Feminine Sanctity and Spirituality in Medieval Wales (Cartwright 2008), explains that the statements about Eluned’s sisters is not merely a remark that was put into the story to accentuate her father’s goodness as a king, or to emphasize the Christian character of the region. Each of the sisters were venerated in the region, and one of them is even described as creating a bloodline directly to the male patron saint of Wales, St. David.151 The most common trait of these sisters in the stories is that they, just like Eluned, wanted to become brides of Christ. Along the lines of Walker Bynum’s observations of female saints finding their calling either early in life or rather late, all of these women are told to have started their walk with God at an early age.152 None of them are described as having had dramatic conversion stories. Still, when they take a stance for their virginity in puberty, they are either murdered by pagan Saxon kings wanting to marry them or, like St. Melangell and St. Gwenfrewy, they are miraculously saved from the men pursuing them so that they can start a community for female followers.153

Cartwright further describes a clear difference between the stories told about the male and female saints in Wales. In the Welsh context, the male stories often follow the narrative pattern of a secular hero’s journey.154 This is a different pattern than the liminality described by Walker Bynum. Nevertheless, the male stories follow a clear social drama. Their childhood is great. They receive a good education, and then they “come out” by performing a miracle at some point. After this, they live a long and peaceful life, healing many and punishing unbelievers.155

In contrast, the female stories all involve scenes of abduction, torture, murder and even rape (to explain the birth of a male saint). In conclusion, virginity and martyrdom or life-long dedication to asceticism became the pattern for females in Wales to reach eternal salvation.156 Importantly, when looking at accounts like these, is that the male gaze may subscribe a certain amount of high drama and violence to a story where the female “protagonist” sees herself as only following a continuous path with Christ, going from the role of sister to that of spouse and mother.157 Thus, the theme of continuous struggle, portrayed by Walker Bynum, can still be a dominant trait in these stories. What is clear at least is that the women do not have a moment of “coming out”, nor do they “live happily ever after”, creating miracles and showing up as a male leader.

It is mainly after their death that the female saints of this region become sources of healing, and create a following through the celebration of their feast days with pilgrimages to their shrine, holy well and/or statue.158 Many are also honored in poetry and songs, while some even get a play of some kind performed during their celebrations.159 Also, in the stories told about St. Eluned, we may find that, not only did her site of martyrdom become a place of pilgrimage, she was decapitated, and at the site of where her head fell, a Holy spring burst forth.160 Herbert McAvoy explains that the way that the feast of Eluned is described, as a celebration taking form, not primarily inside the church where her relics were contained (according to Cartwright), is suggestive of the space itself having been sacralised.161 Could the dancing also have been experienced by those who took part in this celebration as a path for creating a theology of sanctification?

Cartwright tells us that the shrine actually contained Eluned’s relics; this is a further clue to how we can understand the dancing. The kinesic depictions of a progression of different forms of dance that I suggest in the first part of this article, may now find a slightly altered nuance. The dancing in the beginning may have been an opening and prayerful greeting of the saint, and the more gesturing movements may have been a way to portray to the saint where various afflictions laid. In the end, it was the true praesentia and poetentia of the saint—evoked by the praise—that brought forth the healing. Her miracle-working power and the particular celebrations around her shrine may even have had such far-reaching importance for the region that Gerald of Wales framed it within the language of sin and repentance to bring it under Church authority. The people celebrating may have had a different story to tell.

Stated in another way, the importance of a sanctified life does not mainly lie in what happened in her actual life. Instead, it lies in what her life and death gave inspiration to. When the life of sanctity was defined by Lloyd as living as there are no norms, he describes that sanctity may inspire liturgy. While rituals are described as practices that uphold norms, liturgy is a practice that has the potential to alter norms.162 “Liturgy involves specific, exceptional practices in which one acts as if there are no norms”.163 It aspires to create a gap towards the norms in order to alter them. This is done partly by offering a foretaste of a world to come.164 So, when the life of St. Eluned speaks about possibilities that are unavailable within the norms, and when listening to stories about her life leads to people taking up new ways of being, altering the way they treat each other, themselves and the creation around them, one can say that Eluned’s life has laid the foundations of a liturgy. When a community comes together to celebrate this life, and such celebrations contain elements of exceptional practices that lack ordinary norms, we may say that her life has created a liturgy. Her life has been able to loosen the forever-present pull that social norms have on us, and thereby has broadened people’s political imaginations.165 This broadening of imaginations may have also been something that the Church authorities found scary and, thus, they wanted to steer the reception of her story away from a living liturgy and into the form of a ritual, which can be contained.

Interestingly enough, not only did the yearly feast of St. Eluned gain a following, so did her life. Cartwright tells us that she was able to localize a community of nuns founded at St. Eluned’s shrine in Usk, sometime before 1135. Cartwright bases this on the work of William Worcestre (1415–1485), that states that the convent was founded by Richard de Clare (c. 1153–1217).166 When Gerald of Wales wrote his account, therefore, an established nunnery probably existed on the site. Communicating St. Eluned’s story may have inspired more women to follow in her footsteps of a sanctified life. Further, it may have been a story written at least partly with the intent to support these sisters’ lives.

Cartwright further tells us that very few convents with women were able to establish a prosperous and strong following in Wales. This was partly due to the Cistercian order being favored by the Welsh nobility; they were not as willing to establish female houses as the Benedictine communities found in England.167 It is thus curious that the nuns that Gerald of Wales may have been promoting with his telling of the story of St. Eluned’s feast day were Benedictines.168 He might have had a double interest in establishing a Benedictine house (tying the Welsh family to the English network) and strengthening a newly founded community with the revenues gained from pilgrims. Whichever way, the community of nuns would have played an integral role in the celebrations of the feasts, and by writing about it, he supported both the ritual and the liturgy established around her shrine.

Brown tells us that the shrines of the martyrs became places where those who had been touched by the saint gathered on a regular basis. He writes that the laity, especially women, were the ones who cleaned the shrines, cared for the distribution of food, and welcomed the pilgrims to the holy places.169 At later periods of time, these tasks were often taken up by more established communities when such could be formed. It was not only the task of the community to care for the shrine and the pilgrims, it was often also a joint task of the laity and the religious “professionals” to build a liturgy around the festivity.170

6. The Liturgy of the Feast

Taking the stance that what we have read in the depictions of Gerald of Wales at least party describes the liturgy practiced on the feast day of the saint, new possibilities of interpretation open up. First of all, it seems more likely that the singing and dancing in the cemetery, inside and outside of the church, were truly signs that all of this area was sacred grounds.171 The healing power of the well and the presence of St. Eluned’s relic opened up for rejoicing as if there were no norms.

Brown tells us that an important part of the understanding of relics was that the healing potential existed in the tension between the saint now resting in the calm and delightful peace of afterlife, and the immense pain they had been able to endure in their bodily existence on earth. This poetentia and praesentia of the saint arrived when the community gathered together to “remember” and welcome her. This was often done by reading the passio, a story of the sufferings of the saint.172

Returning to the stories found about Eluned, Cartwright tells us that, unfortunately, none of the Welsh saints appear to have been canonized by the Roman Catholic Church. There are also very few official vitae or other written documents that give full accounts of the whole lives of these local saints and the cult of their veneration.173 Therefore, we do not know what kind of a passio was being read at St. Eluned’s feast day. It may even be the case that Gerald of Wales’s account would later be used as a passio. On occasions like these, Felski’s words about the limits of a critical stance in understanding our materials may give way to what Seeta Chaganti calls the invention of imagination; the need to let go of our claimable facts and play with the scant findings we do have.174 Re-constructing history from the female and danced point of view requires more openness to what can be found between the lines of what is told in texts and archives.175

Instead of building the story of St. Eluned from her non-existing vitae, there are other ways to bring the celebration of her life into focus. Cartwright describes that, when it comes to other Welsh female saints, there are strands of poetry, pictorial narratives or historical records that can be used instead.176 Bringing many different strands together may create a fuller picture. This raises the question: could the singing and dancing described at the beginning of St. Eluned’s feast be seen in a similar light? Did the singing contain a local song or poem written in her honor? Was the gesturing a way to show affliction in one’s body, that then activated the relic, just like reading of the suffering in the passio would?177

Cartwright tells us again that, in the case of Eluned, there is neither poetry nor records of her feast day found in the Welsh calendars. She turns instead to the account of a very similar story to that of Eluned, that of Gwenfrewy, probably the most renowned Welsh female saint. By examining their lives side by side, Cartwright attempts a reconstruction of Eluned’s life that is denser than that in Gerald of Wales’s version.178