Abstract

This study investigates the ongoing transformation in galleries, auctions, and museums in Hong Kong, Shanghai, Taipei, and Singapore, where new models for art transactions and exhibiting practices lead to unprecedented evolution in the global art market. While the pandemic hit the art market unprecedentedly, art organizations in Asia are seeing the light at the end of the tunnel as the digitalization of online auctions and virtual art-viewing technology has made up for the cancellation of art events. We are also seeing increased cross-regional and cross-national collaborations in marketing and exhibiting activities. Whether or not it is part of their active strategy, to keep up with the rapid market changes, galleries and auctions must now devote more resources to their digital platforms. Affluent art collectors in this region see art consumption not only as a socially conditioned, symbolic mechanism manifesting wealth and cultural capital but also as an attractive investment vehicle with an increased appetite for the financialization of artworks. What are the benefits and complications of the digitalization of online art transactions and art viewing? How do multi-sited auctions and exhibitions indicate the increased demand for collaboration between commercial art organizations and art institutions? Based on fieldwork and semi-structured interviews with actors in the art markets and secondary Chinese resources, this research generates insights into organizational behaviors in Asia’s art scene and how the art market players actively adapt and persevere via taking on new, entrepreneurial models of operation and speeding up trans-regional and trans-national connectivity with their Western counterparts.

1. Introduction

The 1990s–2020s saw a remarkable artistic transformation in Asia, particularly in the rapidly expanding art hubs of Hong Kong, Shanghai, Taipei, and Singapore1. While the COVID-19 pandemic hit the global art market unprecedentedly, art organizations in Asia are seeing the light at the end of the tunnel as the digitalization of online auctions and virtual art-viewing technology make up for the cancellation of art events. We are also seeing increased cross-regional and cross-national collaborations in marketing and exhibiting activities.

Whether or not it is part of the active strategies of marketing and promotion, to keep up with the rapid market changes, galleries and auctions must now devote more resources to their digital platforms (Walmsley 2016). Affluent art collectors in this region see art consumption not only as a socially conditioned, symbolic mechanism manifesting wealth and cultural capital but also as an attractive investment vehicle with an increased appetite for the financialization of artworks.

How did the Asian art market players actively adapt and persevere via taking on new, entrepreneurial models of operation and speeding up trans-regional and trans-national connectivity with their Western counterparts, such as bold experimentation with new tariff-free zones and existing infrastructure of free ports? What are the benefits and complications of the digitalization of online art transactions and art viewing? How do multi-sited auctions and exhibitions indicate the increased demand for collaboration between commercial art organizations and art institutions? This research studies the ongoing transformation in Asian galleries, auctions, and museums, where new models for art transactions and exhibiting practices lead to irreversible changes and refreshing dynamics in the global art market. Based on fieldwork and semi-structured interviews with actors in the art markets and secondary Chinese and English language resources, this study generates insights into organizational behaviors in Asia’s art scene in the framework of building and re-configuring an interconnected paradigm that is centered around concepts of inter-Asian and Asia-global connectivity.

2. Literature Review and Inter-Connected Asia as a Method

An emerging cluster of research tracks the patterns and dynamics of the development of Asia’s art markets from embryonic to the more mature stage. Claire McAndrew’s art market research report (McAndrew 2013) captures the Asian art trade as an essential category in the distribution of the global art market from 1990 onward. Fieldwork-based research of commercial galleries (Kharchenkova 2017), education of creative practices in art schools (Chumley 2016), art fairs and auctions (Molho 2021), amongst other cultural institutions in Asia’s rising art scene, suggest the importance of individual agency, creative entrepreneurship (DeBevoise 2014), and cross-cultural appropriations and links with the more established Western models of operation in the cognitive processes of institutionalization.

Case studies focusing on the concept of hub cities adopt a comparative angle while examining the key characteristics of the organization and strategic models of Asia’s major art market centers confronting accelerated “liquid modernity (Bauman 2000)”, varied geographic and organizational contexts, and policy discourses. Art institutions and actors working in these institutions in the Asian context and their interconnectedness with the global art distribution chain are relatively under-explored, mainly due to their relatively short history and limited access to documentation of primary and secondary resources in this geographical location.

Adopting a comparative lens to study the Asian markets has proved helpful, for it allows us to examine patterns of organizational models and policies in a more nuanced manner. Svetlana Kharchenkova (2019) uses cross-border mimetic isomorphism to investigate the institutional differences, similarities, imitations, and appropriations of the institutional practices in China’s contemporary art market benchmarked against those in the West while taking into consideration the indigenous context. As Jeremie Molho (2021) elaborates, comparing the Hong Kong and Singapore art markets shows contrasting approaches to positioning Asian cosmopolitan cities as art hubs (market-driven vs. state-led) from the perspectives of organizational configuration and infrastructure building.

Literature in social science illuminates the impact of social networks on individual and socio-organizational evolution and success (Burt 2009). Departing from symbolic interactionalism, Becker (1982) emphasizes the importance of interacting actors in shaping and adjusting social structures and conventions rather than the structure itself. Bourdieu’s theory of the field of cultural production (Bourdieu 1993) and Becker’s postulation of the art world complement one another in the dealings of social networks in the sense that the former emphasizes the objectivity of the positional interconnections implicitly embedded and structured in the artistic field, whilst the later more subjectively focuses on the visible social relationships and networks. Becker’s concept of collective art production has fostered discussions in the art market about the joint construction of social value through the socially mediated network structures of individual actors, including artists, art critics, dealers, auctioneers, curators, and consumers (Morgner 2014; Chong and Alexander 2008; Velthuis 2003).

When invoked to signify globalization and the impact of COVID-19 on the Asian art market, “interconnected Asia” calls forth multi-level paradigms meant to expand beyond Euro-American-centered perspectives and the intellectual traditions associated with them:

Instead of focusing on the interior of a single region-, country- or city-based, “interconnected Asia” conceptualizes and situates Asia in global terms with local expressions, formed through ever-shifting, dynamic and fluid networks, cultural connections, processes, and experiences. Instead of focusing on the fixed essence defined by temporality and spatiality, taking on the inter-connectivity-centered approach helps shape a productive understanding of Asia as a transforming process re-activated and re-invigorated by critical connectivities and flexibilities of people, objects, and shared human experiences (Tagliacozzo et al. 2019; Leung 2019; Xiang and Toyota 2013). This may help us realize the many still-unexplored possibilities beyond the disciplinary frameworks and capture nuanced organizational patterns and strategies in the new context, especially as technology-empowered tools enabled and facilitated accelerated trans-regional and trans-national connections, flows, and movement of commodities, individuals, organizations, and communities (Manzenreiter 2014; Ching 2008).

Situating interconnected Asia in the context of the visual arts scene (Antoinette and Turner 2014; Clark 2010) sheds light on how profit and non-profit art intermediaries, artists, collectors, curators, and the general public have collectively contributed to the formation of transcultural, trans-regional, and transnational networks, inter-Asian reach and mobilities through multi-sited collaborations and sharing of online and office spaces for art viewing and sales, as well as increased flexibilities realized and reconfigured through contemporary art curatorship and exhibitions (Sambrani 2011), creative virtual viewing, and sales technologies (Figure 1). The shared experiences and sensibilities of online and office exhibitions and dealership practices were crucial for the formation of the interwoven inter-personal networks and are therefore meaningful for studying Asia’s visual arts scene and cultural landscape, reconstituted in a new economy of the cultural field where creative cultural consumption is continuously re-configured and re-shaped through technology-empowered tools and access.

Figure 1.

Christie’s Shanghai to London Evening Sale Series Realized USD 334 million (RMB 2 billion), 1 March 2022. Image Courtesy: Christie’s. The auction, entitled “20/21 Century Shanghai to London”, started out in Christie’s new office and gallery space at Bund One Shanghai, front-loaded with works by young artists that were nearly fresh from the studio, before turning over to the British capital, where a Surrealist art evening sale was held.

This study relies on mixed sources of data, including semi-structured interviews conducted in the author’s multi-sited fieldwork during 2016–2022, immersive participatory observation, archival materials collected at the Asia Art Archive and the Hong Kong Collection, the Library of the University of Hong Kong, and secondary data. In 2016, the author worked in the marketing department at the fair Art Central Hong Kong (“ACHK”) and conducted eleven-month immersive fieldwork at multiple fair sites, gallery openings, studio visits, and auctions. This led to an accumulation of contacts via the snowballing method (initial contacts leading to others with more institutional knowledge or relevance), including some of the key art world insiders of Greater China.

The pool of key interlocutors consists primarily of art fair organizers (n = 8), art dealers (n = 9), collectors (n = 5), curators and art specialists (n = 7), and artists (n = 8). In addition, numerous visits to artists’ studios, art fairs, gallery events, and conferences in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Shanghai further complement the fieldwork. Archive materials, such as exhibition and auction catalogs, art journals and periodicals, press release articles, recorded interviews with artists, dealers, art fairs, auctions, and gallery managers, provide diversified sources of information complementing the field-based research and form an essential part of the mapping of the institutions and networks of actors as well as contextualizing the different perspectives of the art market development.

Multi-disciplinary in nature, this study is also informed by the contextual history of modern and contemporary Asian art and the evolution and configuration of its art world. The art-historical literature on the history of private art patronage, especially those on pre-modern and modern China’s art market, provides coherent and inter-connected narratives on the emergence of the modern marketplace of art commodities that interface with the discourse of modernization of the country and its art and continue to inform the historical and cultural contextualization of this geography’s art market in present days (Cahill 1994; Chan 2017; Silbergeld 1981; Wue 2015; Zhu 2005).

3. Contextualizing Asian’s Art Market

In historical China’s urban hubs, the imperial court and the private art marketplace were not divorced in the context of collecting, commissioning, appreciating, and exchanging artworks, and especially evaluating their commercial worth and aesthetic quality (C. Wang 2010). Buying and selling antique paintings, works of calligraphy, and precious decorative arts in varied forms, art dealers busied themselves weaving a complex network of the art trade. Demand for these commodities came from the ruling emperors and princes, the elite collectors with highly educated backgrounds, foreign diplomates, missionaries, business associates, and humble traders and nouveau riche that played an increasingly prominent role in this market (Clunas 2017).

We must not neglect the important social and cultural norms that have been deeply rooted in the culture of art collecting and patronage when studying high culture consumption in Asia, especially in the Sinophone world (Latham 2002), while acknowledging its rapid growth and at times a shared tendency to appropriate and imitate the habitus of Euro-American peers. The main body of literati artists in pre-modern (Clunas 2003) and modern China, mostly well-educated officials, created paintings and calligraphy and commissioned fine curios for leisure and social reciprocity (Bai 1999; Ko 2016), as buying and selling art for money was considered a less revered practice with a certain amount of social stigma than creating art for pastime. It was until the late 19th century that with the burgeoning merchant culture in the Yangtze River delta area, especially in Shanghai and Yangzhou, an active private art market meeting the demand of the merchant class rose and supported professional artists that produced art for a living and consequently the early galleries and dealer shops (Wue 2015) (Figure 2). Awareness and understanding of the cultural and historical context complement our perception of the contemporary attitudes and sensitivities towards pricing and marketing strategies and individual and organizational behaviors in this geography in a more nuanced manner.

Figure 2.

Chen Shizeng (1876–1923), Viewing Paintings (Du hua tu), 1918. Ink and color on paper, 87.6 × 46.6. The Palace Museum.

Situating the dynamics of modern and contemporary art development into the political field of power in twentieth-century China, studies address the intersection between the political, social, and moral concerns of the state and intensified commodification of visual trends as represented by actors in the private sector of the art market (Andrews 1994; Kraus 1991). In Viewing Paintings, Chinese painter Chen Shizeng (1876–1923) depicts mixed crowds of Chinese and Westerners appreciating painting scrolls in an exhibition held in Republican Beijing to raise funds for charitable purposes in times of political and military turmoil in the early twentieth century (Nie 2004)2.

With the changing socio-political atmosphere in Mainland China after 1949, the conventional practices of private art dealerships became largely obsolete. The market for art shrank as traditional art galleries withered. Chinese artists faced a tightening of control on artistic production: instead of creating art for private patrons, most now had to paint for the state. To quote China’s founding Chairman Mao Zedong’s famous talk at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1943, art should be “in the service of the people”. In Hong Kong and Taiwan, however, the art and antiquities trade thrived with the flourishing merchant economy and the arrival of galleries and auction houses with an international mindset. It was the liberation of art from the China state monopoly in 1978 that brought the beginning of a nascent regime for Mainland China’s art market. President Xi Jinping urged for “innovative models for China’s cultural industry and consumption sector, providing the people with quality cultural products to ‘improve the culture, the happiness, and well-being of the people’ (Zhao 2021)”.

Hong Kong is one of the few places in world history that came into being on the frontier of an irresistible globalization process that is still actively continuing and evolving (G. Wang 2016). Under the neoliberal market forces, Hong Kong has established a leading position as an important international financial center and trading hub, on a par with New York, London, and Shanghai. Since the 1990s, it has risen to become Asia’s major hub for increasingly globalized exchanges in the art trade. Accounting for 48% of Chinese auction sales, ahead of Beijing (37%) and Shanghai (8%), Hong Kong has long kept a historical role in terms of facilitating and promoting cultural and economic exchanges between the East and the West and enjoyed a simple and low tax system3 as well as geographical proximity to the increasingly affluent Mainland China. Hong Kong’s experience in coping with the increasingly important transcultural art world encounters in its unique cultural landscape—both before and after the British colonization—has positioned it as a microcosm of international society. The Western art market takes it as a model for China and Asia’s art hub and has paid great attention to its internationalization in the art marketplace. The influx and soaring of galleries, art fairs, and auction houses set up good case studies of how Hong Kong’s growing international art networks have increased both the volume and speed in promoting and facilitating the commodification of art (Molho 2021).

The core strength of the Asian art hubs relies on two facts, taking Hong Kong for example:

First, the easy tax policy is clearly advantageous for making it a competitive art hub: there is no goods and services tax, import or export tariffs, and there are no local sales, consumption, or value-added taxes for art. For commercial galleries operating in Hong Kong, corporate taxes can be as low as 6% of the revenue. In comparison with Hong Kong, Mainland China has a very high tax system on art, especially art produced outside China, with the tax of importation at 20–34% and value-added tax at around 17% of the transaction price4.

Second, the technological, operational, and logistical know-hows jointly contribute to the first-rate efficiency and capacity of hosting international art sales and exhibition events. Post-colonial Hong Kong has a higher degree of freedom of speech and a more democratic and open political environment than Mainland China, rendering it compatible with the established conventions and expectations in the international art market.

4. Cannot Walk Back: Post-Pandemic Changes Are Irreversible

According to the 2021 annual global art market report (McAndrew 2021), global sales of art and antiques (USD 50.1 billion) were down 22% in 2020 from 2019. Asian dealers reported an 11% decline in sales, and dealers in Greater China at 12%. They experienced a more severe impact in the first half of 2020 as this geography was among the first to experience the negative impact brought by the immediate lockdowns. With a market share of 36%, Greater China replaced the US (29%) to become the largest market in the auction sales segment. With slower economic growth, China plans a strong fiscal policy and tax and fee cuts (estimated USD 173.68 billion) in 2022 to prop up the economic growth (Reuters 2022, February). During the National Two Sessions (lianghui) in 2021, China’s leadership issued plans to (1) issue legal documents related to the public listing of artworks; (2) further infrastructure building of art trade and exchange centres (yishupin jiaoyi zhongxin) with an estimated goal of 1000 centers nationally in 2025; (3) strengthen professional education and training of licenses art intermediaries.5

The pandemic and the accompanying restrictive administrative measures taken by governments have exerted an unprecedented impact on the Asian art market: stagnated growth in overall art sales, gallery employment, and organization of touring art fairs and exhibitions, cancellations of fairs, and delays in commissioning (Reuters 2021, March). Facing the pandemic-related disruption and uncertainty, some galleries and auctions closed or shrank exhibition space and pivoted to adopting a mixed online and offline strategy for marketing and sales.

Cautious about long-distance travel and concerns about inflation, Asian collectors, especially those in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, shared a focus on local-oriented purchasing, increased acceptance of online sales channels, and stronger motivations to invest to hedge inflation and diversify the portfolio. The increasing openness and acceptance of online art viewing and sales observed in these locations aligned with global performance: in 2020, global online art sales doubled to a record high of USD 12.4 billion, accounting for 25% of the market’s overall value, up from 9% in 2019. Including art fair Online Viewing Rooms (“OVRs”), the share of dealers’ revenues from online art sales tripled from 13% to 39% (McAndrew 2021). As dealers, fair organizers, and museums increasingly adopt digital engagement with audiences that facilitates online participation through social media platforms, anyone curious about a faraway exhibition can virtually attend the event by simply hitting the web address or social media account for JPGs and live updates.

The digital transformation in the art world has had important and lasting effects on cost structure, pricing, content, and distribution of cultural goods and services. Prior to the pandemic, art dealers reported financial burdens in rent costs and expenses for participating in the art fairs (Leung 2019) (Figure 3). While the pandemic hit the art market unprecedentedly, whether or not it was part of their active strategy, galleries and auctions devoted more resources to their digital platforms to keep up with the changing market sentiments, especially in developing the digitalization of online platforms and virtual art-viewing technology with the hope of making up for the cancelation of art events (Feinstein 2020). In other words, dealers replaced the cost of venue rent and fair participation with one taking on an online- and community-oriented model, increasing budget allocation for developing OVRs, digital transactions, and social media marketing. Although virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) supported exhibitions cannot completely replace the conventional experience of viewing, now, with social distancing, the mimicking of the real-world gallery setting, embedded video content, live-chat conversations, and customized interactions with artists enabled in OVR platform and stream services, they have proved effective in reaching existing and new audiences and collectors.

Figure 3.

Visitors at the Art Basel Hong Kong 2021, May 2021. Image Courtesy of Art Basel.

According to the Fine Art and Antiquities Auction Indices issued by the China State Price Bureau (2021), the breakdown of sales of art and antiquities in Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan in 2021 suggested Chinese paintings and calligraphy at 42.1%, antiquities (porcelain, jade, and other curios) at 29.9%, oil paintings and Chinese contemporary art at 12.4%, collectible curios at 5.9%, and fine jewelry and accessories at 9.6%. The data inform us that while the traditional sector of paintings, calligraphy, and antiquities remained stable and resilient after the pandemic (Art & Market 2019), there was an increased appetite for consuming the less conservative contemporary art and non-Chinese art. Experienced collectors were buying conservatively after the pandemic, with nearly half (46%) focusing only on galleries they had patronized before.

For dealers and specialists of masterpieces by established artists and collections and/or blue-chip artworks that had already established trust and reputation with clients, the impact of the pandemic was mainly reflected in the changing channels of communication with increased reliance on OVRs, e-catalogues, and social media communication tools like Wechat, Zoom, Whatsapp, and Instagram. Some reported a higher frequency of communication. As a signifier that stimulates trust, evidence that backs up the authenticity and quality of artworks is positively correlated with sales success rate, price levels, and returns in art auctions and sales (Li et al. 2021). The new viewing options, marketing strategies, and communication tools were able to deliver and highlight such evidence when long-distance traveling and on-site viewing options were reduced and limited.

In March 2021, Warrior by Jean-Michel Basquiat became the most expensive Euro-American artwork (USD 41 million) ever sold in Asia. In March 2022, Christie’s five-hour marathon evening auction—which for the first time bridged an auction with 20 works in Shanghai to another 68 in London and 22 in the Surrealist offering—achieved sales of USD 334 million and was seen as the auction house’s move to further advance into the Asian market, with nearly 30% bidders from Asia and 28% Generation-Y.

The increased appetite for less conservative international modern and contemporary art (Artprice 2018) was closely tied to market demand from new collector demographics that were keen on exploring diversified choices and willing to trade off the stability in price ranges for expectations of future return and social glamour, in which the latter is correlated with a community-based value-creation mechanism that provides an alternative proxy to value, setting itself apart from dealers’ and specialists’ estimates and historical price performances in the secondary market. The high-net-worth Millennials Collectors or Generation-Y (born between 1981–1996) made a significant contribution to this sector with their openness towards online transactions, virtual viewing experiences, and community-based purchasing habits, as well as demand for increased transparency in price and historical transaction records. Asian collectors accounted for 30% of all of Sotheby’s sales in 2020, with nearly 40% being new to the auction house (McAndrew 2021). Often with overseas education and living experiences, these collectors had access to the latest trends in the international art world and self-invented initiatives to educate and familiarize themselves with resources of art history, collections, and museum studies. Besides, relatively unscathed by the economic grips of the pandemic, they were entrepreneurial about tailoring collecting strategies, forming personal tastes, and developing consumption habitus aligned with their social media community, especially as we identified the profound impact of celebrities promoting and curating contemporary art (Villa 2021).

Art market performance and returns on investment in art are sensitive to economic and financial recession and stagnation (Géraldine et al. 2021). As a glamorous, high culture form of investment that makes it stand out from fixed-income options, art investment may not outperform equity (Mei and Moses 2002), but it has emerged as an attractive option for diversifying assets and investment portfolios, enriching cultural capital, and performing social distinction (Bourdieu 1979), which has met the demand and expectations of the new crop of middle-to-upper class (Osburg 2013) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Poster of online art auction. When Tradition Meets Contemporary Art (contemporary ink art, famous prints, sculpture, and Japanese paintings). December 2021. Courtesy: YIT Art and Fine Art Asia. The online auction event, held by the Shanghai-based YIT Art and Hong Kong-based Fine Art Asia features sales of contemporary ink art, famous prints, sculpture, and Japanese paintings.

In this instance, “platformization”, which reduces the importance of intermediaries, has rendered online art sales platforms appealing venues for consumers to access artworks, artists, and prices in a more straightforward manner. Underpinning the trend of merging online and offline marketing and sales is an unmistakably economic-and-technological-determinist ideology, which, in turn, serves greater scale and larger projects of producing new relations and business opportunities that transcend conventional boundaries and restrictions. Before Cecilia Xiunan’s current role, responsible for leading the online art platform YIT Art, based in Shanghai (the art business is part of the rapidly expanding Chinese media and e-commerce company Yitiao Group), she was a specialist in fine Chinese art at an international auction house in Hong Kong. While acknowledging the promising growth potential of the Chinese art market and increased trans-regional and trans-national inter-connectivity and collaborations between involved actors, she also suggested (interview conducted in February 2022):

“The goal is to strengthen the networks (guanxi) and create as much fluidity and collaboration as possible so. We would like the platform to be able to identify and find the right set of artworks and promote artists that would be compatible with consumers and are interested in working with us. [Another goal of the digitalization transformation is to] save as much cost of labor as much as possible via experimenting and introducing new online marketing channels and transaction models”.

What can also be observed in the post-pandemic art market is a shard sense of ambivalence consisting, on the one hand of the pursuit of speed and glamour with less regard to boundaries between nations, cultures, and pre-established socio-cultural norms and restrictions, and, on the other hand, of a contradictory sentiment which continues to question the sustainability of a demand-driven market. Under the increasingly ‘invasive’ pressure and irreversible trend of adopting technology in art viewing, marketing, and sales practices, the boundaries between artists, collectors, art institutions, and the public have been utterly transformed, bringing about profound mutations that remap transformation and rediscovery of priorities and hierarchies in the art industry.

A sense of uncertainty in the high-end art consumption sector can be identified in the fieldwork observation:

First, China’s existing COVID-19 pandemic policy—the zero-tolerance approach—led to isolation in affected communities. Second, as engineers and product managers busy themselves with constant trials and errors on the online art sales platforms, one should also factor in the need to take into consideration the cost of “intangible labor” for developing various channels and tools. Thirdly is the delay of art students entering the market. With an increasing number of college graduates delaying their entry into the job market, we should be aware of the potentially dire implications and ripple effects if the trend persists or intensifies.

In addition, with the rise of new public and private art organizations, there seems to exist a shortfall of talents in museum and art market practices. Universities in Hong Kong and Shanghai launched new academic programs in the museum and curatorial studies, cultural management, and art history to meet the increased demand for talents (Lingnan University 2021; The University of Hong Kong 2020).

Fourth, policies remain uncertain and ambiguous when it comes to regulating digital art assets, especially in the NFT market, leading to space for speculative investment and hyped market sentiment. Implicitly buttressed by a ritual economy of digitalization of art production and transaction models favoring disintermediation, the NFT phenomenon is increasingly an economic and technological determinist ideology. The current policy does not support NFT trading in Mainland China, though many have expressed avid enthusiasm to participate via the multiple platforms available online.

5. Towards an Inter-Connected Asia and Its Integration into the Global Art Market

With the overall art ecology undergoing significant changes, Hong Kong and Shanghai are among the fastest-growing Asian art megacities, both eager to connect to the global art discourse and use the commercial and non-commercial art scenes as useful instruments in urban regeneration, city-branding, and cultural tourism.

Sotheby’s opened the first representative office in Hong Kong in 1973 and Christie’s in 1986. The first art fair took place in the former British colony in 1992. The auction boom started in the early-to-mid-2000s, and the art fair boom started in the late 2000s with the arrival of Art Basel. After New York, Hong Kong became the second-largest auction market for modern art in 2020, overtaking London.

A prominent feature of the Hong Kong art market scene is the laissez-faire economy, where the government takes on minimal intervention in the private sector and yields to a market-actor-driven model for the structuration and formulation of its art infrastructure. The government has set aside HKD 20 billion (USD 2.6 billion) for arts and culture expenditure in 2019, compared with HKD 840 million (USD 108 million) in 2017. In the meantime, the West Kowloon Cultural District project introduces two new museums to the city’s art infrastructure, showcasing cultural policy makers’ ambition to champion contemporary art and promote creative innovation in the visual arts scene: the M+, the museum of modern and contemporary visual arts, and the Hong Kong Palace Museum, a collaborative project between Hong Kong’s West Kowloon Cultural District Authority and Mainland China’s Beijing-based Palace Museum (gugong) (Chow 2021). One of the many intriguing aspects of the development of the M+ project has been under debate and critical discussion about how hegemonic Western-influenced exhibition models and curatorial strategies have pre-conditioned the growth of the city’s cultural institutions, problematizing expectations for the museum’s cultural languages and operational models to engage with distinctively unique local characteristics (Ho 2014).

The Hong Kong art market, despite its many advantages, is faced with two potential stringent issues:

First, it has to do with increased competition from other Asian art hubs such as Shanghai, with a three-folded population of 24 million and the potential for the government to introduce increasingly beneficial tax policies and cut administrative costs associated with importing and exporting artworks, especially in the designated freeport areas with “bonded” customs status, storage facilities, and logistics support and services for artworks to invigorate the art business (China State Taxation Administration 2019). China recently adjusted the value-added tax rate for imported goods, leading to a reduced VAT tax for imported artworks of 13% and further discount policies for VAT for corporate consumption. Since 2019, the tax rate for purchasing an imported oil painting has been reduced from 20% to 14%. The Shanghai Pudong district’s fine art storage bonded warehouse waives the VAT on works of art, saving more costs for collectors and dealers.

Besides Shanghai, the South Korean capital city Seoul, with an active track history of operating local galleries with an international reputation, such as Gallery Hyundai (since 1970), Kukje Gallery (since 1982), and Arario Gallery (since 1989) and an influx of international galleries and art fairs, including KIAF (since 2002), Perrotin (since 2016), Pace Gallery (since 2021), Lehmann Maupin (since 2022), and the Frieze Art Fair (September 2022), has become itself a major destination for international art dealers and collectors to access Asia’s art market (Artnet 2021). With less political risk faced in its peer cities in Mainland China and Hong Kong and the expedited growth of young collector demographics, the strength of Seoul relies on the fact that South Korea does not have import taxes on art or sales tax for artworks below USD 50,000 (KRW 60 million) (The Art Newspaper 2021).

Second, with the influx of mega international galleries and emerging regional galleries in Hong Kong over the past three decades, the galleries are faced with potential saturation, especially since the most important sales tend to take place during the Basel Hong Kong art fair week and the spring and fall auction seasons, and the rental cost for gallery space is expensive (Kanis 2019; Artnet 2018). Factors such as China’s anti-corruption campaign, the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, the Sino-US tensions, and the COVID-19 pandemic have generated anxiety in the art scene in this geography. Although the major international auction houses and the Art Basel Hong Kong fair have reported resilient performances despite these impediments, many regional art market players are reeling from the impact of the pandemic lockdown and social distancing.

Shanghai’s state-owned Shanghai West Bund Development Group holds a key position in Shanghai’s contemporary art ecology (Shanghai National Foreign Cultural Trade Base 2017). In 2014, the Shanghai West Bund Development Group and the Swiss art logistics provider company EuroAsia Investment Group jointly developed a fine art bonded storage and service platform, which is part of the West Bund Fine Art storage project, providing custom bonded and other storage services for over 200 art pieces from international organizations, including the Long Museum, Yuz Museum, West Bund Art and Design, Design Shanghai, Pompidou Centre Shanghai, and Sotheby’s. In 2017, the Shanghai government launched plans to “accelerate the innovative development of cultural and creative industries”, and set out a clear ambition to support the art trade with favorable policies in the pilot free port district, such as partial exemption from customs deposits and import duty and customs clearance facilitation for imported artworks for world-class art fairs (ArtsAsiaPacific 2012).

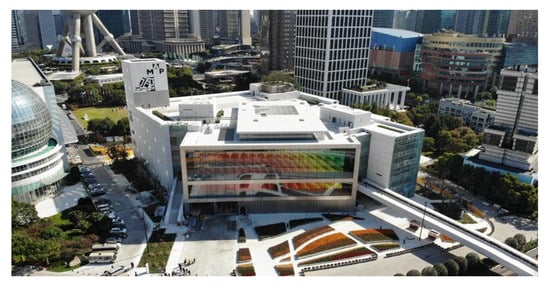

Before COVID-19, in 2018, the Shanghai-based West Bund Art Fair and Art 021 fair attracted 70,000 visitors, in a tie with Art Basel Hong Kong at 80,000 and Art Basel Miami at 83,000 (Yicai 2020). In November 2021, the ART021 Shanghai Contemporary Art Fair opened at the Shanghai Exhibition Centre with 134 participating galleries, and visitors entered the fair with negative test results as a prerequisite. As of October 2021, Shanghai had 96 museums, including 25 state-owned and 71 private, and hosted 2000 exhibitions on average each year (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Visitors at the China International Import Expo, Shanghai, November 2021.

In 2020, the third edition of China International Import Expo introduced an art and cultural relics section in the services trade exhibition area. This section granted each exhibiting organization a zero tariff on five pieces, with the hope of attracting overseas exhibitors and a flow-back of fine artworks and cultural relics (Chinese News Services 2021). A total of 9 international exhibitors, including Christie’s and Sotheby’s, reported sales of 41 items totaling USD 120 million (RMB 760 million) at the exposition’s fourth edition in 2021. The Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama’s iconic Pumpkin was the first tariff-free item on exhibit. According to Shanghai customs, it took 24 h for the customs process to be completed, from the shipment’s exiting the Waigaoqiao Free Trade Zone to its arrival at the exposition site (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The customs transaction was managed and completed within 24 h for Yayoi Kusama’s Pumpkin to arrive at the fourth China International Import Expo, Shanghai. Image courtesy: Shanghai Customs.

Lorenz Helbling, founder of ShangArt Gallery, one of the first and most important commercial galleries in Shanghai, comments on the comparison between Shanghai and Hong Kong’s commercial art scene: “Each side [of Hong Kong and Shanghai] has its pros and cons. Hong Kong may be easier for business and more streamlined with the international world, but Shanghai is a city of 30 million people with a surrounding population of 300 million in a country of a billion”. New online marketplaces for galleries, auction houses, and fairs have been launched in China’s art megacities. Art institutions have seen increased trans-regional collaborative partnerships as joint efforts to broaden access to clients and audiences.

For galleries with operating franchises internationally, this can be easily achieved by touring exhibitions in multiple locations (Figure 7). Such collaborations also strengthened the reproduction of international prestige as a vital currency in today’s art world (Harris 2013). In 2018, the New York and Hong Kong-based Sundaram Tagore Gallery collaborated with the Beijing-based Ink Studio on a collaborative project where the latter exhibited one of the represented artists at Sundaram Tagore’s gallery on Madison Avenue, giving the gallery access to a completely new audience outside China. In 2021, Para Site, one of the oldest and most active independent art institutions in Hong Kong, collaborated with the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai to co-present programs, hoping to bring the art communities in the two cities together and evolve into new synergies.

Figure 7.

Gagosian’s booth at ART021 Shanghai 2021. Image Courtesy: Gagosian and JJYPhoto.

The Hong Kong art dealer Pearl Lam (Artnet 2017), whose gallery business is operated in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Shanghai, sensibly lamented the lack of a local-focused model for successfully promoting Asian artists to the international art market: “Every artist wants to have institutional success and international recognition, but in order to get that they have to cater to the ‘Western approach’” (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

People travel on a tram covered in an ad for the Botticelli and His Times exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, December 2020, image courtesy of Xiaomei Chen. As part of the Hong Kong Jockey Club Series, the Hong Kong Museum of Art collaborated with the Uffizi Galleries in Florence to bring and exhibit a total of 42 Renaissance-era masterpieces. Botticelli’s work is prominently shown with other Renaissance painters, such as Filippo Lippi and Piero del Pollaiolo.

Pearl Lam and several other Asian galleries—Kwai Fung Hin, Alisan Fine Arts, and Galerie du Monde—adopted a “fusion strategy” where they promoted Asian artists with considerable training or living experience in the West or whose styles were interspersed with notable Western artists to the vastly uninitiated, demonstrating a shared desire to foreground Asian art in a unique Asia-focused locale in a transcultural context.

Multi-sited, mixed online and offline curatorial projects and international art exchange programs have populated international and Asian regions. In 2021, the Museum of Art Pudong opened an inaugural collaborative exhibition showcasing the collections of artworks sent over from the London-based Tate Gallery, including those by Claude Monet, John Martin, and Anish Kapoor. This exhibition was part of the partnership between the museum’s developer, Shanghai Lujiazui Group, and the Tate Gallery in the UK. University-based exhibitions and research-oriented curatorial programs featuring multi-sited exhibitions and art and technology received funding and institutional support. The Hong Kong and Beijing-based curator Janet Fong and her international team launched “CITYA”, a multi-city art exchange program and exhibition taking place concurrently in six global cities: Beijing, Hong Kong, Macao, Rome, San Francisco, and Tallinn. Commenting on the impact of the pandemic on the nature of exhibitions, she suggested that post-pandemic changes were irreversible as the calling for collective inter-connectivity has become increasingly important. The fact that a rising number of Euro-American museums have been actively collecting, studying, and displaying artworks from Asia has also led to collaborative interpretations and shared curiosity about what constitutes Asian art, as well as engagement with cultural diversity (Jiao 2021) (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The Jean Nouvel-designed Museum of Art Pudong launched in 2021 with a partner exhibition from Britain’s Tate, image courtesy of Rider Levet Bucknall.

Competition presents equal opportunities to collaborate (Hong Kong Business 2019), maintain relationships with longstanding contacts, and share and exchange resources, especially when demand for stable blue-chip artworks remains high and there exists a shared interest to protect and ensure stable market growth for the represented artists. Trans-regional cooperative commercial exhibitions are case studies of collaborations between dealers and collectors, as well as between multi-sided art communities. Since 2017, the London and Hong Kong-based contemporary art gallery White Cube has collaborated with the Long Museum, China’s leading private art museum founded by the billionaire collectors Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei to exhibit the works of Antony Gormley and Beatriz Milhazes at the museum space in Shanghai. The curatorial concepts, interpretations, and design of the exhibition were led by the gallery’s staff based in London. At the execution level, the installation, marketing, logistics, and business development were shared between the gallery’s operating franchise in Hong Kong and the partnering private museum in Shanghai.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the art market unprecedentedly. Although the major international auction houses and Art Basel Hong Kong reported resilient performances despite the pandemic-related impediments, many regional art market players are reeling from the impact of the pandemic lockdown and social distancing. However, art organizations in Asia see the light at the end of the tunnel as the digitalization of online art sales and virtual art-viewing technology made up for the cancelation of art events and even, in certain situations, replaced conventional on-site exhibition and art sale events. To keep up with the rapid market changes, galleries and auctions devoted more resources to digital platforms, and we are seeing increased cross-regional and cross-national collaborations in marketing and exhibiting activities in the art industry.

New online marketplaces for galleries, auction houses, and fairs have been launched in China’s art megacities. As engineers and product managers busy themselves with constant trials and errors on the online art sales platforms, one should also factor in the need to take into consideration the cost of “intangible labor” for developing various channels and tools. China’s existing COVID-19 pandemic policy—the zero-tolerance approach—led to isolation in affected communities. In the midst of the pandemic-led recession, we also observe the delayed entry of art students into the job market, as well as a shortage of funding for art and cultural institutions. With an increasing number of graduates delaying entry into the job market, we should also be aware of the potentially dire implications and ripple effects if the trend persists or intensifies.

In addition, affluent Asian art collectors see art consumption not only as a socially conditioned, symbolic mechanism manifesting wealth and cultural capital but also as an attractive investment vehicle with an increased appetite for the financialization of artworks. Behind the NFT hype phenomenon, implicitly buttressed by a ritual economy of digitalization of art production and transaction models favoring disintermediation, is the economic and technological determinist ideology. There are still a lot of questions about how digital art assets are regulated, especially in the NFT market. This leaves room for speculative investment and hype in the market.

Situating interconnected Asia in the context of the visual arts scene sheds light on how professional art intermediaries, artists, collectors, curators, and the general public have collectively contributed to the formation of transcultural, trans-regional, and transnational networks, inter-Asian reach and mobilities through multi-sited collaborations and sharing of online and office spaces for art viewing and sales, as well as increased flexibilities realized through virtual viewing and sales technologies and joint efforts to broaden access to clients and audiences. Increased opportunities to form trans-regional and inter-Asian collaborations and partnerships are in parallel with intensified competition between the major Asian art capitals (The Art Newspaper 2021).

Asian art market studies share much with film, music, fashion, and other sectors of the creative culture industry in terms of inter-Asian mobilities and flows of people and capital. However, this research suggests features of the Asian art market under transformation that give distinctiveness to the evolving and changing shared experiences, conventions, and sensibilities of online and office exhibitions and dealership practices. The features and changes unveiled in this study implicate that discovering and understanding the development processes of inter-Asian connectivities in global terms makes a meaningful framework for investigating Asia’s visual arts scene and cultural landscape. In so doing, it emphasizes the connective medium of the art market’s organization and human players as an important bridge in forging connections for the region.

New patterns and complexities observed in the post-pandemic art market in Asia and its increasingly interconnected nature may provide implications for researchers and participants in the global art market. As the 59th edition of the Venice Biennale entitled “The Milk of Dreams” (Alemani 2022) continued to explore the relationship between individuals and technologies and the ever-evolving technological reality we live in and encounter (Paul 1990), one may share similar concerns and curiosity when it comes to the art market. This research has left many interesting issues for future research, for instance: Have the art market actors become increasingly alienated from the experience of engaging with artworks? Or rather, has the enabling of technologies strengthened the accessibility and frequency of art viewing and collecting and the human networks involved in this new reality?

Funding

Lee Hysan-HKIHSS Fellowship Scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the editorial support and helpful suggestions from the external reviewers and the Arts editors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The TEFAF art market report includes Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao for China. Within the scope of this research, the discussion of China mainly refers to Mainland China and Hong Kong and incorporates and highlights the international and trans-regional mobility and travels of the individual actors in the art market in this geography. In addition to the hubs mentioned in this study, other Asian art hubs such as Tokyo, Seoul, New Delhi, and others are of no less importance and demand comprehensive investigation. |

| 2 | For discussion on the modernization of art exhibitions in China see: (Andrews 2007). Exhibition to Exhibition: Painting Practice in the Early Twentieth Century as a Modern Response to ‘Tradition’. In Turmoil, Representation, and Trends: Modern Chinese Painting 1796–1949, International Conference Papers. Gaoxiong, pp. 23–58. In addition, see (Claypool 2011). Ways of Seeing the Nation: Chinese Painting in the National Essence Journal (1905–1911) and Exhibition Culture. positions: east asia cultures critique 19.1, pp. 55–82. |

| 3 | There is no import and export tax, sales tax, and value-added tax for art trades and sales in Hong Kong. Licensing procedures are required for the import and export of some goods. They are mainly to fulfill obligations undertaken by Hong Kong to the trading partners or to meet public health, safety, or internal security needs. |

| 4 | The income tax rate for companies is 16.5%. Wealth tax is not applied to works of art owned by individuals or companies. |

| 5 | China’s National Two Sessions (lianghui) mark the start of the next five-year plan and reveal important information about long-term economic plans. |

References

- Alemani, Cecilia. 2022. The Milk of Dreams. Curatorial Statement of the 59th Venice Biennale. Available online: https://universes.art/en/venice-biennale/2022/the-milk-of-dreams (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Andrews, Julia F. 1994. Painters and Politics in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1979. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, Julia F. 2007. Exhibition to Exhibition: Painting Practice in the Early Twentieth Century as a Modern Response to ‘Tradition’. In Turmoil, Representation, and Trends: Modern Chinese Painting 1796–1949. International Conference Papers. Taipei: Chang Foundation, in Collaboration with the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 23–58. [Google Scholar]

- Antoinette, Michelle, and Caroline Turner, eds. 2014. Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-Making. Canberra: Australian National University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Art & Market. 2019. Hong Kong Art Market Resilience. December 14. Available online: https://www.artandmarket.net/analysis/2019/12/14/hong-kong-art-market-resilience (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Artnet. 2017. Gallerist Pearl Lam on Why the West’s Expansion into Asia’s Art Scene Might Not Be Entirely Healthy. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/partner-content/gallerist-pearl-lam-on-the-rapid-growth-of-asian-art-world-and-how-western-theories-have-distorted-our-perception-of-it (accessed on 14 October 2018).

- Artnet. 2018. How Much Is the Public Paying to See a Fair? We’ve Ranked 200 of the World’s Top Art Events, from Most to Least Pricey. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/market/art-fair-admissions-1300457 (accessed on 14 March 2019).

- Artnet. 2021. Ending Months of Eager Anticipation, Frieze Confirms Its New Seoul Art Fair, Scheduled for September 2022. May 18. Available online: https://news.artnet.com/market/frieze-seoul-september-2022-1969953 (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Artprice. 2018. The Art Market in 2018. Available online: https://www.artprice.com/artprice-reports/the-art-market-in-2018 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- ArtsAsiaPacific. 2012. Freeports. November/December. Available online: http://artasiapacific.com/Magazine/81/Freeports (accessed on 1 April 2016).

- Bai, Qianshen. 1999. Calligraphy for Negotiating Everyday Life: The Case of Fu Shan (1607–1684). New Series 3. Asia Major 12: 67–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Howard. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1979. La distinction. Critique Sociale du Jugement. Paris: Ed. de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Edited by Randal Johnson. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 112–41. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, Ronald S. 2009. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, James. 1994. The Painter’s Practice: How Artists Lived and Worked in Traditional China. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Pedith. 2017. The Making of a Modern Art World: Institutionalisation and Legitimisation of Guohua in Republican Shanghai. Buckinghamshire: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- China State Price Bureau. 2021. Fine Art and Antiquities Auction Indices (yipai quanqiu wenwu yishupin zhishu). Available online: http://jgjc.ndrc.gov.cn/ypqqyspzs.aspx?clmId=769 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- China State Taxation Administration. 2019. Announcement on VAT Policy Changes (Guanyu Shenhua zengzhishui gaige youguan zhengce de gonggao). Available online: http://www.chinatax.gov.cn/n810341/n810755/c4160283/content.html (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Chinese News Services. 2021. Chinese National Cultural Heritage Administration Introduced Policies to Facilitate Flow-Backs of Cultural Relics from Overseas. December 29. Available online: http://wap.art.ifeng.com/?app=system&controller=artmobile&action=content&contentid=3523201 (accessed on 19 February 2022).

- Ching, May Bo. 2008. Where Guangdong Meets Shanghai: Hong Kong Culture in a Trans-regional Context. In Hong Kong Mobile: Making a Global Population. Edited by Helen F. Siu and Agnes S. Ku. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, Robertson, and Iain Alexander, eds. 2008. The Art Business. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, Vivian. 2021. Exhibitions at New $450m Hong Kong Palace Museum Will Offer ‘a Fresh, Contemporary Interpretation of Chinese Culture’. The Art Newspaper. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/hong-kong-museum-s-fresh-take-on-beijing-s-treasures (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Chumley, Lily. 2016. Creativity Class: Art School and Culture Work in Postsocialist China. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, John. 2010. Asian Modernities: Chinese and Thai Art Compared, 1980 to 1999. Sydney: Power Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Claypool, Lisa. 2011. Ways of Seeing the Nation: Chinese Painting in the National Essence Journal (1905–1911) and Exhibition Culture. Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique 19: 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunas, Craig. 2003. Elegants Debts: The Social Art of Wen Zhengming. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clunas, Craig. 2017. Chinese Paintings and Its Audiences. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeBevoise, Jane. 2014. Between State and Market: Chinese Contemporary Art in the Post-Mao Era. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein, Laura. 2020. Beginning of a New Era’: How Culture Went Virtual in the Face of Crisis. Guardian. April 8. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/apr/08/art-virtual-reality-coronavirus-vr (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Géraldine, David, Yuexin Li, Kim Oosterlinck, and Luc Renneboog. 2021. CentER Discussion Paper Series No. DP16575. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3960146 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Harris, Jonathan. 2013. Gatekeepers, Poachers and Pests in Globalized Contemporary Art World System. Third Text 27: 525–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Oscar. 2014. Under the Shadow: Problems in Museum Development in Asia. In Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions: Connectivities and World-Making. Edited by Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. Canberra: Australian National University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Kong Business. 2019. Hong Kong Art Scene Faces Competition. Available online: https://hongkongbusiness.hk/leisure-entertainment/in-focus/hong-kong-art-scene-faces-competition (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Jiao, Tianlong. 2021. Recontextualizing Contemporary Chinese Art at the Denver Art Museum. Orientations 52: 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kanis, Leung. 2019. Hong Kong Artists Bemoan High Cost of Renting New Venue in West Kowloon Cultural District, but Officials Say HK$63,000 Weekly Rent is Reasonable. South China Morning Post. March 29. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/society/article/3012318/hong-kong-artists-bemoan-high-cost-renting-new-venue-west (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Kharchenkova, Svetlana Sergejevna. 2017. White Cubes in China: A Sociological Study of China’s Emerging Market for Contemporary Art. Ph.D. thesis, Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research (AISSR), Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences (FMG), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Kharchenkova, Svetlana Sergejevna. 2019. Bringing Art Market Organizations to China: Cross-Border Isomorphism, Institutional Work and its Unintended Consequences. The China Quarterly 240: 1087–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ko, Dorothy. 2016. The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Richard Curt. 1991. Brushes with Power: Modern Politics and the Chinese Art of Calligraphy. London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, Kevin. 2002. Rethinking Chinese Consumption. In Postsocialism: Ideals, Ideologies, and Practices in Eurasia. Edited by Chris Hann. London: Routledge, pp. 217–37. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Angela Ki Che. 2019. A "South" Imagined and Lived: The Entanglement of Meical Things, Experts, and Identities in Premodern East Asia’s South. In Asia Inside Out: Itinerant People. Edited by Eric Tagliacozzo, Helen F. Siu and Peter C. Perdue. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 122–45. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuexin, Xiaoyin Ma, and Luc Renneboog. 2021. In Art We Trust. CentER Discussion Paper Series No. 2021-016. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3871007 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Lingnan University. 2021. Master of Arts in Creative and Media Industries: Admission from 2021. Available online: https://www.ln.edu.hk/visual/macmi/en/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram. 2014. Playing by Unfair Rules? Asia’s Positioning within Global Sports Production Networks. Journal of Asian Studies 73: 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2013. Global Art Market, With a Focus on China and Brazil. Helvoirt: The European Fine Art Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, Clare. 2021. The Art Market 2021. Basel: Art Basel and UBS Group AG. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, Jianping, and Michael Moses. 2002. Art as an Investment and the Underperformance of Masterpieces. American Economic Review 92: 1658–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molho, Jeremie. 2021. Becoming Asia’s Art Market Hub: Comparing Singapore and Hong Kong. Arts 10: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgner, Christian. 2014. The Art Fair as Network. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 44: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Hui. 2004. Chen Shizeng he ta de ‘Du hua tu’. Zijincheng 125: 100–1. [Google Scholar]

- Osburg, John. 2013. Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China’s New Rich. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Ellen. 1990. Video Is a Hole (Single Channel Video Artwork). Hong Kong: Courtesy of Ellen Paul and Kiang Malingue. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters. 2021. Analysis: One Year into Pandemic, the Art World Adapts to Survive. March 18. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/one-year-into-pandemic-art-world-adapts-survive-2021-03-18/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Reuters. 2022. China Plans Bigger Tax, Fee Cuts in 2022 to Prop Up Slowing Economic Growth. February 22. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3167935/china-plans-bigger-tax-fee-cuts-2022-prop-slowing-economic?utm_source=copy_link&utm_medium=share_widget&utm_campaign=3167935 (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Sambrani, Chaitanya. 2011. When India and China Engage: A Curatorial Adventor. In Conference Paper Abstract for ‘The World and World-Making in Art’ Conference. Canberra: Humanities Research Centre, The Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Shanghai National Foreign Cultural Trade Base. 2017. On Accelerating the Innovation and Development of Shanghai’s Creative Art Industry (Guanyu jiakuai benshi wenhua chuangyi chanye chuangxin fazhan de ruogan yijian). Available online: http://cn.cccweb.org/portal/pubinfo/2020/04/28/200001005121/d81912a133284080add4e9fb68da0867.html (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Silbergeld, Jerome. 1981. Kung Hsien: A Professional Chinese Artist and His Patronage. The Burlington Magazine 123: 400–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliacozzo, Eric, Helen F. Siu, and Peter C. Perdue, eds. 2019. Asia Inside Out: Itinerant People. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Art Newspaper. 2021. Local Galleries Need to Wake Up, Learn to Compete with the Real Deal’: What Seoul’s Galleries Think of the Influx of International Dealers. October 25 Reported by Reena Devi. Available online: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2021/10/25/local-galleries-need-to-wake-up-learn-to-compete-with-the-real-deal-what-seouls-galleries-think-of-the-influx-of-international-dealers (accessed on 14 January 2022).

- The University of Hong Kong. 2020. Inauguration of a New Taught Master’s Degree Program in Art History. Available online: https://arthistory.hku.hk/index.php/academic-programmes/master-of-arts-in-art-history/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Velthuis, Olav. 2003. Symbolic Meanings of Prices: Constructing The Value of Contemporary Art in Amsterdam and New York Galleries. Theory and Society 32: 181–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, Angelica. 2021. Prince, Basquiat Lead Sotheby’s $108.2 M. Jay Chou-Curated Contemporary Sale in Hong Kong. ArtNews. June 18. Available online: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/prince-basquiat-lead-sothebys-108-2-m-jay-chou-curated-contemporary-sale-in-hong-kong-1234596183 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Walmsley, Ben. 2016. From Arts Marketing to Audience Enrichment: How Digital Engagement Can Deepen and Democratize Artistic Exchange with Audiences. Poetics 58: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Cheng-hua. 2010. The Qing Imperial Collection Circa 1905–25: National Humiliation, Heritage Preservation, and Exhibition Culture. In Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Art and Visual Culture. Edited by Hung Wu. Chicago: University of Chicago, pp. 320–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Gungwu. 2016. Hong Kong’s Twentieth Century: The Global Setting. In Roberts, Hong Kong in the Cold War. Edited by Priscilla Roberts and John M. Carroll. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wue, Roberta. 2015. Art Worlds: Artists, Images, and Audiences in Late Nineteenth-Century Shanghai. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Biao, and Mika Toyota. 2013. Ethnographic Experiments in Transnational Mobility Studies. Ethnography 14: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yicai. 2020. Shanghai Launching Art Fairs Whole Year Long, Artworks on Show Nationally under Free Tariff (Shanghai dazao quannian buluomu yibohui, baoshui zhuangtai xia yishupin ke quanguo zhanchu). November 12. Available online: https://www.yicai.com/news/100834858.html (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Zhao, Haiying. 2021. Promoting High Quality Development in the Culture Industry (tuidong wenhua chanye gao zhiliang fazhan). People’s Daily. September 16. Available online: http://opinion.people.com.cn/n1/2021/0916/c1003-32228316.html (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Zhu, Qi. 2005. Xianggang Meishushi [History of Hong Kong Fine Arts]. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).