Abstract

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, many builders, artists, and architects living on the shores of Italian lakes decided to settle in Poland. Upon arrival, they pursued brilliant careers in various areas of life. Over time, they became Polonized. This was also the case for Giovanni Battista Trevano, who was active in Krakow in the first half of the 17th century and whose lifetime achievement was to become the royal architect of the Vasa kings. This article presents Trevano’s artistic oeuvre and provides insight into his social, economic, and intellectual status in the new community, including the architect’s offspring, who pursued successful careers in army, church, and state offices throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. These new findings are based on manuscripts that have recently been discovered by the author of the article in both Polish and Swiss archives. They allow for expanding the knowledge of the Trevano family’s genealogy and biography, and correcting some unjustified views in the discourse. On the basis of research on new archival sources, one can conclude that Giovanni Battista Trevano was a prominent architect, who is credited with introducing in Poland the early Baroque style, which soon became dominant in northern European art.

1. Introduction

Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, representatives of many European nations, including Italians, settled in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in search for better opportunities for development. Giovanni Battista Trevano (who died in Krakow in 1642) is a remarkable example of a success story: he was a native of Northern Italy who became the royal architect at the court of the Vasa dynasty. He was credited with introducing early Baroque to the Polish lands.

The article aims to prove Giovanni Battista Trevano’s significance as the leading architect in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 1st quarter of the 17th century by presenting his artistic oeuvre and career path. The article expands the catalogue of Trevano’s works and is the first biographical entry discussing the artist’s social status, professional network, and intellectual interests.

Polish studies on the topic tend to focus on the artistic activity of Italian expatriates, while other aspects of their lifes (e.g., social and economic status, and relations among artists and other foreigners) require more attention, which is also true for Trevano. In the first half of the 20th century, several Polish authors contributed to creating a catalogue of works by Trevano, including rebuilding the royal castle in Krakow and the palace in Lobzow, expanding the Zwierzyniec monastery, numerous commissions by bishop Szyszkowski at the Krakow cathedral, and the completion of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul (Klein 1910, pp. 23–57; Tomkowicz 1912, pp. 128–34; Kutrzebianka 1925, pp. 14–15; Łoza 1931, pp. 341–42). Olga Solarz (1960, pp. 457–58), which confirmed Trevano’s involvement in the construction of the Senators’ Staircase of the Royal Castle. Adam Małkiewicz (1967, pp. 78–80) provided a detailed review of Trevano’s involvement in the building of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul. Antoni T. Piotrowski (1984, pp. 350–54) attributed construction of the side chapel of the Carmelite church to Trevano. In past decades, Polish author Mariusz Karpowicz produced (and circulated including outside Poland: (Karpowicz 1983, pp. 22–39)) the unjustified view that Trevano was solely a mediocre builder of average talent whose style can be regarded as unsophisticated (Karpowicz 1994, pp. 47–71; Karpowicz 2002, pp. 23–28; Karpowicz 2013, p. 14). Karpowicz based his theory on the limited number of historical sources to which he had access and on his personal opinion that Trevano’s contemporary Matteo Castello was the leading architect of the time. His theory was opposed by Adam Małkiewicz and Kazimierz Kuczman (Małkiewicz 1994, pp. 319–21; Kuczman 1994, pp. 168–74; Małkiewicz 1997, p. 107)1. The first studies concentrating on Trevano’s life, published by Piotr J. Janowski (2019a, pp. 57–59; 2021, pp. 104–5), revealed new details from the artist’s biography and determined his date of death, a fact that was not confirmed before.

Recently, however, new findings by the author of the current article allow for the correction of the unjustified views formulated by Karpowicz. Thus, Giovanni Battista Trevano now stands a chance of regaining his reputation as an intriguing figure with a bright career. The current article confirms that Trevano was the country’s leading architect and a prominent social figure of the time by elaborating on several aspects of his life: the title of Royal Architect, individual privileges granted by the king, his art becoming a model for his contemporaries, economic status, and intellectual interests. This was possible thanks to manuscript and stylistic analyses. Newly discovered manuscript sources include Krakow municipal acts, royal accounts, acts of the King’s grand governor of Krakow, and parish registers of Lugano Cathedral.

2. Factors Influencing Changes in Polish Art and Culture in the 16th and the First Half of the 17th Century

The 16th century was a golden age of Polish art and culture. The rule of the last two kings from the Jagiellonian dynasty, Sigismund I the Old (1506–1548) and his son Sigismund II August (1548–1572), was a period of political and economic prosperity, when unprecedented development happened in art and culture as the thriving capital city of Krakow attracted many Italians.

In 1518, Sigismund I the Old married Bona Sforza d’Aragona (Besala 2012). During their reign, two Italian architects, Francesco Fiorentino and Bartolommeo Berrecci, oversaw the rebuilding of the Wawel Royal Castle in Krakow in a Renaissance style. They are also credited with expanding Krakow’s cathedral to include the Sigismund Chapel, the burial site of the Jagiellonian kings, which is considered to be a masterpiece of Renaissance architecture in Poland (Zlat 2010, pp. 15–52; Mossakowski 2012; Fabiański 2017; Mossakowski 2021). This prosperous era continued during the reign of the last Jagiellonian king, Sigismund II August, an art lover and the owner of a unique tapestry collection who, in 1569, forged a real union between Poland and Lithuania, resulting in the two countries becoming one federal state with the third largest territory in Europe (Witusik 2000, pp. 115–24).

However, the golden age did not end with the dynasty’s extinction. Over a dozen years after the death of the last Jagiellonian, the throne was assumed by the Swedish prince Sigismund (1587–1632), who became the first member of the Vasa house to rule Poland–Lithuania2. His long rule was marked by the advent of Baroque in Poland.

Following the coronation ceremony, Sigismund III Vasa moved into the royal residence at the Wawel Hill in Krakow. In 1595, the castle’s northeastern aisle was destroyed by fire (Leitsch 1978, pp. 245–50). This sad event turned out to be a blessing for the residence. The king ordered the destroyed castle to be rebuilt. At the same time, the fire might have accelerated Sigismund’s decision to expand his residence in Warsaw that was to become a frequent destination for the king (Wrede 2013). In order to realize his artistic ambitions, Sigismund III Vasa hosted many foreign artists, predominantly those of Northern Italian origin (Kuczman 1994, pp. 163–74).

3. Giovanni Battista Trevano’s Career as an Artist in Poland–Lithuania

Giovanni Battista Trevano was probably born in the late 1560s. He died in Krakow in the fall of 1642 (Janowski 2019a, pp. 58–59; Janowski 2021, pp. 104–5). Trevano was a native of Cassarate near Lugano, born as the son of a patrician family that appears in documents as far back as the 12th century. In the Middle Ages, members of the family included clergy, notaries, and public officers in Lugano and the surrounding area (Lienhard-Riva 1945, pp. 486–87)3. According to a document from 1662, Giovanni Battista was the son of Vito, a man-at-arms in service of the kings of France (Trezzini 1934, pp. 45–46; AGAD, MK 203, f. 76v). Although the reasons why Trevano decided to move to Poland remain obscure, one could assume he was willing to improve his financial conditions or pursue a successful career.

Many Polish sources from the early 17th century, including those of the Vasa court, have not survived, which greatly hinders determining the date and circumstances of Trevano’s arrival to Poland4. The same applies to identifying the architect’s first works. The first mention of Trevano’s name appears in a 1599 document regarding the payment for the construction of the Senators’ Staircase of Wawel Castle (Solarz 1960, p. 457). The commissioned works were part of the castle’s rebuilding following the 1595 fire.

Trevano began leading the refurnishing of the castle’s interiors in 1602 (AGAD, ASK 1, RK 337, f. 153, 180v; AGAD, ASK IV, Księgi Rekognicji 11, f. 1124; Kieszkowski 1935, p. 18). Over the course of the reconstruction efforts, several rooms were equipped with new stucco moldings, early Baroque portals, and floorings. Early Baroque window frames were placed in the Senators’ Staircase. By 1603, a two-story tower had been erected at the northeastern corner of the castle. Each story had a cabinet with a hallway. Next to the tower, a royal chapel was built with a richly decorated stucco vault.

Trevano can thus be credited with introducing new architectural themes to the Wawel residence, and the design and construction of the north façade of the castle facing the city center, with two residential towers placed in the corners (Figure 1) (Tomkowicz 1908, pp. 345–48; Bochnak 1948, pp. 122–23; Szablowski 1965; Kuczman 1994, pp. 163–66)5. This should be acknowledged as an extraordinary achievement given the fact that Wawel’s north façade would become a model for many other residences in Poland (e.g., Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw and the Palace of the Krakow Bishops in Kielce; see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Northern elevation of Wawel Castle with its two residential towers, view from Old Town (designed by Giovanni Battista Trevano). www.shutterstock.com. Image in the public domain.

Figure 2.

Palace of Krakow Bishops in Kielce, supposedly based on a design by Trevano. www.shutterstock.com. Image in the public domain.

Soon, Trevano would be entrusted with another prestigious commission by Sigismund III Vasa. The king decided to expand his summer palace located in Łobzów, just outside the gates of Krakow, where queen consorts-to-be coming from abroad to marry Polish kings were solemnly received6.

The extension of the Łobzów palace took place between 1603 and 1605. The most important works included the construction of a representational southern wing attached to earlier Gothic and Renaissance buildings, resulting in a three-winged Baroque edifice surrounded by a garden. The castle’s elevations received new window frames and cornices, while the interiors were equipped with early Baroque portals, following the example of the Wawel residence. Łobzów remained a place of frequent visits of the Vasa family (Kieszkowski 1935, pp. 17–19; Rączka 1983, pp. 34–37; Janowski 2019a, pp. 56–64).

Another initiative for which Trevano was commissioned was the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, the first Jesuit church in Krakow, which was funded by pious Catholic king Sigismund III Vasa (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Stone façade of Church of Saints Peter and Paul at Grodzka Street in Krakow attributed to Trevano. www.wikipedia.de. Image in the public domain.

Figure 4.

Stone cartouche with coat of arms of the Polish branch of the Vasa house, detail from Church of Saints Peter and Paul’s façade. www.shutterstock.com. Image in the public domain.

The church was erected along the Royal Route, the capital’s representative road serving as a suitable background to coronations, parades, and other ceremonies. Although construction began at the end of the 16th century, it was probably around 1610 that Giovanni Battista Trevano, already styled the Royal Architect, took over the supervision of the construction activities, which lasted at least until 1619. He had the building’s construction reinforced. During that period, the church’s dome was erected, the stone articulation of the façade was built, and the decoration of the church interiors began. The Church of Saints Peter and Paul remains one of the masterpieces of Baroque art in Poland. It is an example of the early transition of new patterns inflowing to Krakow directly from Italy (Bochnak 1948, pp. 89–113; Małkiewicz 1967; Małkiewicz 1997).

Trevano would also soon be commissioned for prestigious works by the clergy of Krakow. The three-decorative-gated wall surrounding the Krakow cathedral at Wawel Hill (1616–1619; Figure 5) is attributed to him.

Figure 5.

Southern gate of the wall surrounding the Wawel cathedral attributed to Trevano, detail. www.shutterstock.com. Image in the public domain.

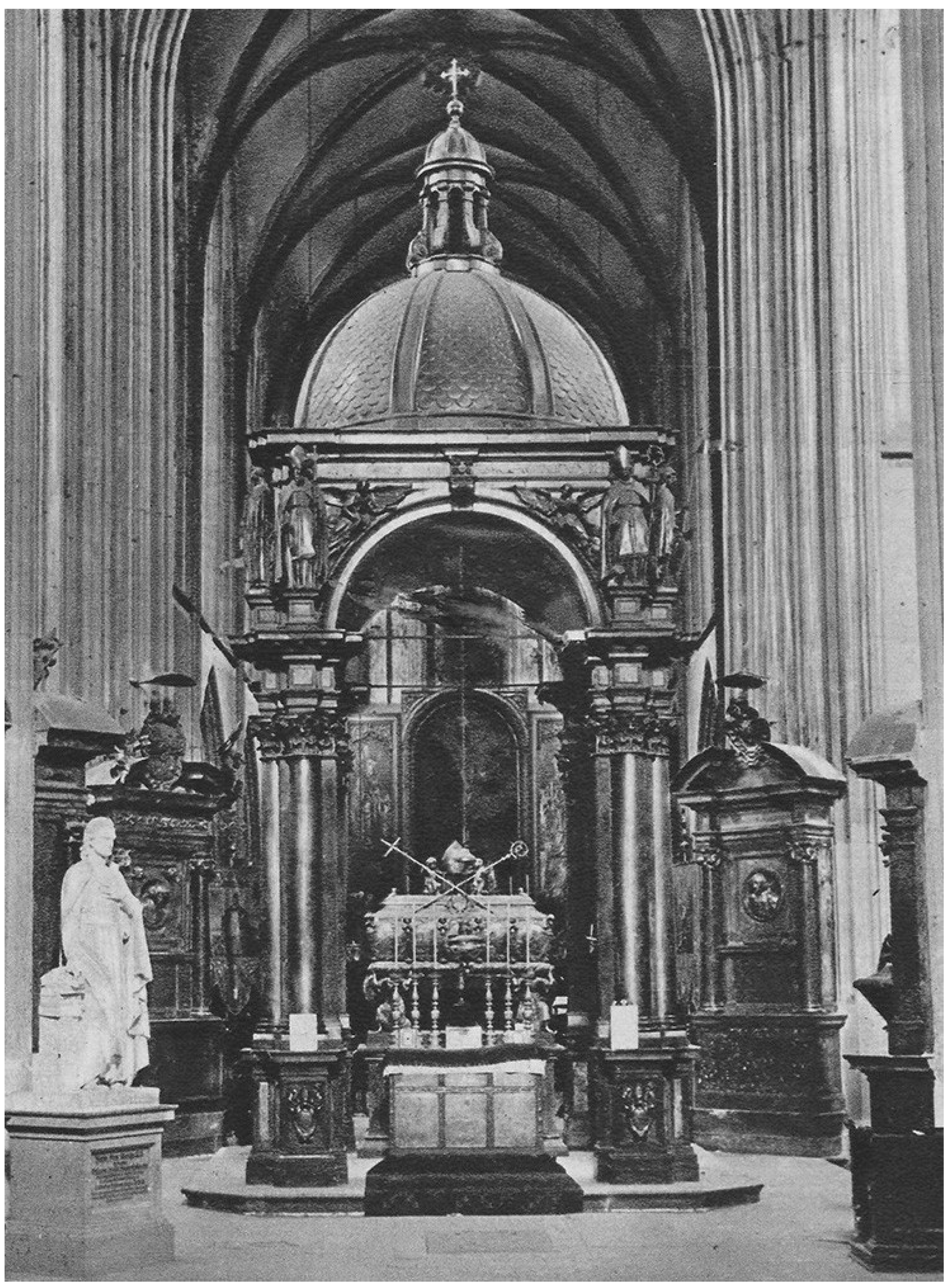

He is also believed to have erected the canopy chapel over the tomb of Poland–Lithuania’s patron, St. Stanislaus, inside the cathedral (1624–1629). The work was funded by the bishop of Krakow, Marcin Szyszkowski (Figure 6), who later commissioned Trevano to create his tombstone (Bochnak 1948, pp. 114–20; Szablowski 1965; Rożek 1980, pp. 47, 74, 104).

Figure 6.

Canopy chapel of St. Stanislaus, patron saint of Poland in Wawel Cathedral, attributed to Trevano. www.dbc.wroc.pl. Image in the public domain.

Stylistic analysis and Trevano’s relationship with the Szyszkowski family are two factors that allow for attributing the rebuilding works in the Gothic Renaissance castle located in the village of Spytkowice, outside Krakow, where an early Baroque palace was most likely erected between 1622–1633 (Figure 7), to him. It was a two-story three-winged edifice with a pillared gallery closed from the north by a screen façade (Holcerowa 1985, pp. 8–15, 54–58, 64–67).

Figure 7.

Façade of the Szyszkowski castle in Spytkowice, near Krakow. Photo by author.

Two square towers were erected at both corners of the front façade. Early Baroque portals were placed in the castle, while new window frames were added in the elevations. The main arguments for Trevano’s involvement in the rebuilding efforts in Spytkowice are the architectural forms and solutions applied previously in the Wawel castle: a tunnel staircase with landings, an early Baroque palace façade with residential towers placed in two corners, and the stonework’s style and articulation7.

Giovanni Battista also worked for female orders, e.g., the general rebuilding of the Norbertine Monastery of Zwierzyniec (near Krakow) in the first decade of the 17th century. Although he collaborated with another builder of Italian origin, Giovanni Battista Petrini, on this commission, it seems it was Trevano who designed the new wing that would be erected next to the monastery’s second cloister and was responsible for turning several buildings of various styles into a harmonious, late Renaissance complex (Daranowska-Łukaszewska and Henoch-Marendziu 1995). In subsequent years, the architect worked for the Carmelite nuns in Krakow, for whom he is attributed to have erected a small one-nave church in early Baroque style (the Church of St. Martin; built in 1638–1644; Figure 8) (Tomkowicz 1912, p. 133).

Figure 8.

Church of St. Martin in Grodzka Street. www.wikipedia.de. Image in the public domain.

Trevano could be the architect of St. Norbert’s Church in Krakow, whose construction commenced in 1637. Attributing this work to him seems justified in light of his earlier works commissioned by the Norbertine order and numerous stylistic similarities to Zwierzyniec Monastery, such as the attic decorated with a sequence of niches.

The third group of Trevano’s commissioners were the patriciate. This area of Trevano’s activity is relatively unrecognized, as most of such buildings had gone through major modifications and reconstructions.

However, Trevano rebuilt Sigismund Alantse’s townhouse on 12 Św. Jana Street in 1611, turning it into a flamboyant patriciate residence. The architect could be the author of the representational staircase of the house as well as its gallery, which was most likely located in the courtyard (Tomkowicz 1912, p. 130; Dettloff et al. 2015). A recent study has confirmed that by 1616 Trevano designed and supervised the building of two townhouses on the prestigious Grodzka Street, a route expanding from Krakow’s Main Square to the royal residence at Wawel Hill8. One of them was commissioned by Simone Mutti, a merchant and citizen of Krakow. Mutti must have enjoyed a closer acquaintance with the architect, as he not only built his new house, but also lent him money for this costly investment9. Trevano may have taken up many other jobs of the kind (ANKr., AMK, Cons., Inscriptiones 458, p. 601).

Giovanni Battista Trevano’s artistic oeuvre from his Polish–Lithuanian period indicates that he was already a fully developed artist at the time of his arrival to Krakow. His first works, commissioned by the king, won him the position of the country’s leading architect in the first quarter of the 17th century. By that time, he was on his way to new lucrative commissions.

Trevano introduced new architectural styles emerging from the circles of Carlo Maderno to Poland. His stylistic repertoire influenced local artists for decades. The artist’s source-confirmed works and those attributed to him confirm his skills in adapting existing structures into new constructions to create a harmonious edifice.

Trevano’s style can be considered coherent. His works demonstrate uniformity despite being partially or entirely structured from older buildings maintaining some of their primary features. Trevano’s name should be connected to a multitude of masonry works. He must have designed or produced early Baroque portals or ear-shaped window frames that today are considered to be a typical feature of the so-called Vasa style. Giovanni Battista Trevano utilized design solutions and decorative motives, applying the elements on the basis of his client’s status, the type of material, or the ordered object. Other features typical of Trevano’s style are stone-carved elements: winged heads, swag curtains, volutes, and denticule guttae.

4. Giovanni Battista Trevano’s Social and Economic Status

Although previous studies of Trevano concentrated on his artistic achievements, they remain silent on his social and financial position. Today, new archival sources allow for assessing Trevano’s position within the community. It is highly probable that he enjoyed special protection from Sigismund III Vasa from the beginning of his career.

In the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sigismund III Vasa was the monarch who had the power to grant the servitorate: an individual privilege for a person employed by the royal court to be exempted from the municipal jurisdiction. Being subject to municipal laws obliged each craftsman to become a member of a guild, a specialized corporation of people practicing the same profession within the city walls. Guild law was strict in limiting independent professional activity of the guild and regulating the number of jobs taken up by each craftsman. When the Krakow stonemasons’ guild accused Giovanni Battista of having accepted too many commissions at once and having an advantageous access to material in 1620, Trevano used the right of servitorate in his defense. The architect may have received the privilege from Sigismund III Vasa in Warsaw in 1613 (Tomkowicz 1912, pp. 131–32; ANKr., AMK, Cons., Controversiae 511, pp. 176–77, 441–42). New findings, however, confirm that Trevano was already using the title of the royal servitor in 1607 (ANKr., AMK, Scab. 30, p. 155).

This proves he was exempted from the local jurisdiction and limitations imposed by the guild on its members, which granted him freedom in his artistic activity and enabled contacts with his future commissioners among court officials, nobility, and clergy.

In addition to his regular architect’s salary, he also received a special stipend from the monarch, which was secured from income from the salt mines of Wieliczka. The artist was also granted the privilege to derive benefit from a farm located in the village of Zielonki outside Krakow (AGAD, ASK XLVI, Lustracje, rewizje i inwentarze dóbr królewskich 47, p. 252; Keckowa 1969, p. 414, note 22; Leśniak 1996, p. 25, note 46). There are archival sources recording loans that Trevano gave to Krakow merchants. Trevano’s wealth is best captured in an inventory register following his death in 1642. Posthumous inventory registers listed a deceased person’s property and estimated its value, as a means to protect the assets from potential creditor’s claims and secure the rights of the heirs. The document lists Trevano’s personal property, such as gem-studded pieces made of gold and silver. There are numerous paintings and valuable household items on the list. Comparing the list to other posthumous inventories of the period, one could assess Trevano’s wealth as that of a nobleman or a wealthy patriciate member. This is also confirmed by the listing of luxurious goods including rich vestments belonging to the architect and his spouse (ANKr., KWK, Acta 10, pp. 547–55; Janowski 2021, pp. 106–7).

The source also lists the artist’s books, which shed some light on his education and intellectual interests. The collection includes over 50 books, most of them written in Latin and Italian, including architecture treatises by Vitruvius, Leo Battista Alberti, Andrea Palladio, and Sebastiano Serlio.

The ability to prepare a given area for battle or to design and build fortifications became inherent qualifications for an architect in the Vasa-ruled Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which is probably why Trevano kept a copy of a treatise by Giovanni Battista Belluzzi, who once worked for Cosimo I de’ Medici and is remembered for fortifying the cities of Florence and San Marino. Among Trevano’s books one cannot ignore works on fortifications by Lorini Buonaiuto or Theatrum instrumentorum et machinarum by Jacobo Bessoni (ANKr., KWK, Acta 10, p. 554; Janowski 2021, pp. 107–8). It now seems even more justified to accept a source-based assumption that Trevano participated in Sigismund III Vasa’s 1609 expedition to Smolensk to fight against the Tsarist Russia (AGAD, MK 203, f. 76v; Wagner 2013, p. 270).

Another not fully discovered chapter of Trevano’s biography is the social and financial network he built in Poland. Shortly after his arrival in Krakow, he took up projects in collaboration with other Italian artists living in Poland: builder Giovanni Battista Petrini and Milanese sculptor Ambrogio Meacci. Trevano guarded the interests of his own brothers, the Venetian merchants Paolo and Giovanni Maria, in Krakow. He maintained a closer relationship with other immigrants from Ticino area (Francesco Mucino/Mocino) and his native Lugano (Giovanni Reitino, Sebastiano Sala). Trevano was often nominated as the executor of last will by foreigners who died in Krakow, some of whom confided their children to Trevano’s care (Tomkowicz 1912, pp. 129–33; Karpowicz 1994, pp. 48–50; Kuczman 1994, pp. 168–74; Karpowicz 2013, pp. 9–31). The artist was a member of the Confraternity of St. John the Baptist (Confraternita di San Giovanni Battista della Nazione Italiana di Cracovia), a religious society that had been founded in the 16th century in Krakow, bringing together local Italians (Tomkowicz 1900, p. 11). The confraternity owned a chapel in the Church of St. Francis and drew profits from its own estates as well as testamentary dispositions received. Its members included merchants, bankers, craftsmen, and artists. The organization was not merely a religious society, however: it served as an Italian community center in Krakow aiming to support Italians already living in the city or those arriving and to facilitate their career launch. The confraternity’s chapel retained its original portal funded by Simone Mutti, was mentioned above (Figure 9). This work can also be attributed to Giovanni Battista Trevano (Rożek 1977, pp. 111–15), which only reaffirms his strong ties with the Italian community in Krakow.

Figure 9.

Portal of the Italian Chapel in the Franciscan Church in Krakow, funded by Simone Mutti in 1634. Photo by author.

Trevano maintained business relationships with Krakow merchants until his death: Giovanni Vincenzo Bottini, Marcantonio Moriconi, and Andrea Cellari. The artist also had financial ties with Jews from Kazimierz, such as the physician Samuel or merchant Isaac Jakubowicz, the founder of a synagogue built in Kazimierz near Krakow between 1638 and 1644 (ANKr., KWK, Acta 10, p. 548; Piechotkowie 1999, pp. 129–33). The synagogue itself is sometimes linked with Trevano, as its vaulting bears similarity to that of the Church of St. Martin.

The king’s protection of Trevano deeply influenced his and his family’s life. Everything seems to indicate that the architect never purchased any estate in Krakow. To be able to do that, he would have had to submit himself to the local jurisdiction of Krakow, which he never did. In turn, Trevano was granted a special privilege by Sigismund III Vasa allowing for him to dwell in a townhouse owned by the monarch, probably around 1610. The house was located in the vicinity of Wawel Castle, on Kanonicza Street (AGAD, MK 182, f. 95v–96; Janowski 2019a, p. 58, note 22).

Trevano was first married to a woman from Lugano, Elisabetta Cannaga, who died before 8 May 1634. They had three daughters (Concordia, Maria Egiziaca, Caterina Teresa) and two sons. One of the sons, Ilario, became a Jesuit priest in Krakow, while Francesco fought at the side of King John II Casimir Vasa in the Khmelnitsky Uprising (1648–1654). The latter would later be granted an indigenatio by John II Casimir Vasa on 20 June 1662 in recognition of his own merits in the field and his father’s long service. This document granted Polish noble status to a foreign noble, which served as a naturalization procedure for nobles. This act was to be perceived as a sign of exceptional recognition granted only to those few foreigners who deserved well of Poland (Grzebień 1996, p. 700; Wagner 2013, p. 270).

There are still some facts from Trevano’s family life that spark interest. For example, in 1631, he purchased some estates together with Elisabetta in Lugano from his relatives while in Lwów (today Lviv, Ukraine), who at the same time were heirs to Zaccaria Castello, a stonemason master of Lviv (Motta 1909, p. 33). The transaction included a townhouse located in Lugano, and a farm with a house, gardens, fields, a vineyard, and a fishing pond. It is difficult to explain the reasons for this transaction; however, one cannot rule out Trevano planning to return home to spend the rest of his days there. What could have disrupted those plans was Elisabetta’s death that followed soon after the purchase.

Another striking fact is that Trevano enjoyed high esteem in Poland, but decided not to marry a local woman, instead setting out on a long journey to Lugano where he married Santina, the daughter of Francesco de Carli (ANKr., KWK, Acta 10, p. 549). The wedding took place on 16 February 1634 in the Cathedral of Saint Lawrence in Lugano; the ceremony was witnessed by Giovanni Maria Trevano, most likely Giovanni Battista’s brother, who is mentioned by archival sources in Krakow in 1609 (ADL, Parrocchia Cattedrale s. Lorenzo Lugano, Matrimoni 3, f. 21v; Tomkowicz 1912, pp. 109, 130). Acting on behalf of himself, and his and Elisabetta Cannaga’s children, Trevano sold the estates of Lugano to Giovanni Battista Quadrio from Lugano and Marta Ciceri, widow of Tommaso Quadrio, for the amount of 225 golden ducats on 8 May 1634 (Motta 1909, p. 33).

Having sold his Luganese properties, the architect returned to Poland. His return is confirmed in King Ladislaus IV Vasa’s letter dated 1635 ordering Trevano to build a catafalque inside Wawel Cathedral for the funeral of the monarch’s brother (Grabowski 1845, p. 84). Trevano and his second wife, Santina, had three children, who were all minors at the time of their father’s death in 1642.

5. Conclusions

The newly discovered archival sources during the author’s research increase our knowledge of the life of royal architect Giovanni Battista Trevano. Focusing on the social, financial, and family aspects of Trevano’s life and work for the first time gives a broader view of his career in Poland–Lithuania in the first half of 17th century.

Thanks to the new findings presented in the current article, one can further argue that Trevano was not merely an average stonemason, but in fact deserves renown as a leading artist of primary importance to the development of the early Baroque style in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. This was helped by Trevano being given the royal privilege of servitorate, thanks to which he was able to develop a thirving career and establish a successful and profitable enterprise. Trevano’s high social position and his financial wealth, as presented in the current article, are two more arguments justifying this view. It is the author’s intention to continue research on the careers of Italian immigrants in Krakow in the 17th century.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Mariusz Karpowicz put forward an unjustified hypothesis that there were actually two persons called Giovanni Battista Trevano living in Krakow, a father and son, both of whom worked as royal architects (Karpowicz 1994, pp. 52–53). Janowski rejected this explanation on the basis of archival sources (Janowski 2019a, pp. 57–58; Janowski 2019b, pp. 234–35) |

| 2 | The last Vasa king to rule Poland–Lithuania was John II Casimir (1609–1672), whose reign was marked by several crises, including a civil war (Khmelnitsky Uprising), the Polish–Russian war, the Swedish invasion (‘deluge’). Fatigued by these events and his beloved wife’s death (Marie Lousie Gonzaga), the monarch abdicated in 1668. |

| 3 | Mariusz Karpowicz took all the Trevano families living in different places across Ticino, all described by Lienhard-Riva, and mixed them into one narration in his publications. This confusion could have been prevented by analyzing those archival sources drawing relationships between Giovanni Battista Trevano and the Trevano family living in Cassarate (Karpowicz 1994, pp. 49–50). |

| 4 | A portion of the significant Vasa royal accounts to the topic of the article was purloined by the Swedish army in 1656. Some other sources (e.g., part of the so-called Marszałkowskie Archive), stored at the Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw, which could provide more insights into the subject, were destroyed in a 1944 bombardment (Straty 1957, pp. 117–18; Wrede 2019, pp. 10–11). |

| 5 | The second tower was only built in 1618–1621, although it had been included in the primary design from the beginning of the 17th century (AGAD, MK 172, p. 292r). |

| 6 | In 1512, Barbara Zapolya was the first future queen-consort to be received in Łobzów. Six years later, Łobzów saw the arrival of Bona Sforza d’Aragona. Two wives of Sigismund II August received a solemn welcoming ceremony there too (Elisabeth Habsburg in 1543, and Elisabeth’s sister Catherine in 1553, both daughters of Ferdinand Habsburg and Anne Jagiellon). In 1592, Łobzów welcomed Anne Habsburg, daughter of Charles II Francis of Austria and Maria Anna of Bavaria. By 1605, the future second wife of Sigismund III Vasa, Constance Habsburg, was received in front of the Łobzów palace already rebuilt by Trevano (Janowski 2018, pp. 30–34, 41–45, 77–78, 102–3). |

| 7 | Piotr Józef Janowski attributed the rebuilding of the Spytkowice castle to Trevano during an academic assembly at the Early Modern Art Section of Department of the History of Fine Arts of Institute of Art of Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw on June 2019, in a lecture titled: “The Royal Architect Giovanni Trevano: New Findings”. |

| 8 | A recent study by Katarzyna Wagner provides a categorization of Krakow’s Grodzka Street as the city’s most prestigious area, where the city’s wealth was concentrated (Wagner 2020, pp. 81–96). |

| 9 | In 1634, Simone Mutti donated the said townhouse to the Italian confraternity (ANKr., AMK, Cons., Inscriptiones 460, p. 1061). |

References

Primary Sources

(ADL) Archivio diocesano Lugano:Parrocchia Cattedrale s. Lorenzo Lugano, Matrimoni 3.(AGAD) Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw (Polish: Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie):(AGAD, MK): Metryka Koronna 172, 173, 182, 203.(AGAD, ASK) Archiwum Skarbu Koronnego:.(AGAD, ASK 1): (RK) Royal Accounts (Polish: Rachunki Królewskie) 337.(AGAD, ASK IV): Księgi rekognicji 11.(AGAD, ASK XLVI): Lustracje, rewizje i inwentarze dóbr królewskich 47.(ANKr.) National archives in Krakow (Polish: Archiwum Narodowe w Krakowie):(ANKr., KWK) Księgi wielkorządów krakowskich, Acta 10.(ANKr., AMK) Acts of the city of Krakow (Polish: Akta Miasta Krakowa):.(ANKr., AMK, Cons.) Consularia: Inscriptiones: 458, 460; (ANKr. AMK, Cons.) Controversiae: 511:.(ANKr., AMK, Scab.) Scabinalia: 30.Secondary Sources

- Besala, Jerzy. 2012. Zygmunt Stary i Bona Sforza. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Zysk i S-ka. [Google Scholar]

- Bochnak, Adam. 1948. Kościół św. Piotra i Pawła w Krakowie i jego rzymski pierwowzór oraz architekt królewski Jan Trevano. Prace Komisji Historii Sztuki 9: 89–125. Available online: https://delibra.bg.polsl.pl/dlibra/publication/25950/edition/24160/content (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Daranowska-Łukaszewska, Joanna, and Henoch-Marendziu Renata. 1995. Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce. Zwierzyniec, Nowy Świat, Półwsie Zwierzynieckie: Kościoły i Klasztory. part 7. IV vols. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Dettloff, Paweł, Rafał Nestorow, and Andrzej Włodarek. 2015. Katalog Zabytków Sztuki w Polsce. Śródmieście Ulica Świętego Jana. part 12. IV vols. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Fabiański, Marcin. 2017. Zamek króla Zygmunta I na Wawelu: Architektura, Dekoracja Architektoniczna, Funkcje (King Sigismund I’s Castle at Wawel: Architecture, Decoration, Functions). Kraków: Zamek Królewski na Wawelu–Państwowe Zbiory Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski, Ambroży. 1845. Władysława IV. Krola Polskiego Listy. Kraków: Drukarnia Stanisława Gieszkowskiego, Available online: https://books.google.pl/books?id=19ZbAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=listy+w%C5%82adys%C5%82awa+IV&hl=pl&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=listy%20w%C5%82adys%C5%82awa%20IV&f=false (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Grzebień, Ludwik. 1996. Treuani (Trewan Hilary (Hilarion). In Encyklopedia Wiedzy o Jezuitach na Ziemiach Polski i Litwy 1564–1995. Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM, p. 700. [Google Scholar]

- Holcerowa, Teresa. 1985. Spytkowice /woj. Bielsko-Bialskie/, Wczesnobarokowy Zamek Marcina Szyszkowskiego Starosty Lelowskiego i Mikołaja Szyszkowskiego Biskupa Warmińskiego, Dokumentacja Historyczna Opracowana na Zlecenie Wojewódzkiego Konserwatora Zabytków w Bielsku-Białej. Kraków: Archiwum Wojewódzkiego Urzędu Ochrony Zabytków w Krakowie. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2018. Pałac Królewski w Łobzowie w Okresie Nowożytnym. Architektura, Funkcje Dworskie i Gospodarcze. Master’s thesis, Archiwum Uniwersytetu Papieskiego Jana Pawła II w Krakowie, Kraków, Poland. Thesis written under Supervision of Prof. Kazimierz Kuczman at Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2019a. Rezydencja królewska w Łobzowie w epoce Wazów 1597–1668. In Residentiae in Temporibus Belli et Pacis. Materiały do Badań i Ochrony Założeń Rezydencjonalnych i Obronnych. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2019b. Review of the Article: Jacek Żukowski, Pałac królewski w Łobzowie–funkcje i przekształcenia w latach 1633–1648, Barok. “Historia–Literatura–Sztuka”, XXIV/1–2 (47–48) 2017, s. 15–37. Folia Historica Cracoviensia 25: 229–42. Available online: http://czasopisma.upjp2.edu.pl/foliahistoricacracoviensia/article/view/3604 (accessed on 12 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Janowski, Piotr Józef. 2021. Inwentarz pośmiertny ruchomości architekta królewskiego Jana Trevana z roku 1642. Rocznik Krakowski 87: 101–117. Available online: http://rk.tmhzk.krakow.pl/dane/abstracts/rk87/rk87_5_en.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 1983. Artisti Ticinesi in Polonia nei ‘600. Bellinzona: Cantone del Ticino. [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 1994. Matteo Castello. Architekt Wczesnego Baroku. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Neriton. [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 2002. Artisti Ticinesi in Polonia Nella Prima Metà del ‘600. Ticino: Edizioni Arte e storia. [Google Scholar]

- Karpowicz, Mariusz. 2013. Artyści Włosko–Szwajcarscy w Polsce I Połowy XVII Wieku. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sióstr Loretanek. [Google Scholar]

- Keckowa, Antonina. 1969. Żupy Krakowskie w XVI–XVIII Wieku (do 1772 roku). Wrocław, Warszawa and Kraków: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. [Google Scholar]

- Kieszkowski, Witold. 1935. Zamek królewski w Łobzowie. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki i Kultury 4: 6–25. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/bhsk1935_1936/0016 (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Klein, Franciszek. 1910. Kościół ś.ś. Piotra i Pawła w Krakowie. Rocznik Krakowski 12: 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczman, Kazimierz. 1994. Przełom wawelski. In Sztuka XVII wieku w Polsce. Materiały Sesji Stowarzyszenia Historyków Sztuki Kraków, Grudzień 1993. Edited by Teresa Hrankowska. Warszawa: Arx Regia. Ośrodek Wydawniczy Zamku Królewskiego, pp. 163–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kutrzebianka, Kazimiera. 1925. Mauzoleum św. Stanisława w Katedrze na Wawelu. Kraków: Drukarnia "Przeglądu Powszechnego". [Google Scholar]

- Leitsch, Walter. 1978. Der Brand im Wawel am 29. Jänner 1595. Studia do Dziejów Wawelu 4: 245–60. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/sdw1978/0255 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Leśniak, Franciszek. 1996. Wielkorządcy krakowscy XVI–XVIII wieku. Gospodarze Zamku Wawelskiego i Majątku Wielkorządowego. Kraków: Zamek Królewski na Wawelu. [Google Scholar]

- Lienhard-Riva, Alfredo. 1945. Armoriale Ticinese: Stemmario di Famiglie Ascritte ai Patriziati Della Repubblica e Cantone del Ticino, Corredato di Cenni Storico-Genealogici. Losanna: Società araldica Svizzera. [Google Scholar]

- Łoza, Stanisław. 1931. Słownik Architektów i Budowniczych Polaków oraz Cudzoziemiców w Polsce Pracujących. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Kasy im. Mianowskiego, Instytutu Popierania Nauki. [Google Scholar]

- Małkiewicz, Adam. 1967. Kościół śś. Piotra i Pawła w Krakowie–dzieje budowy i problem autorstwa. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Prace z Historii Sztuki 5: 43–86. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/phs1967/0097 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Małkiewicz, Adam. 1994. Krakowski kościół Św. Piotra i Pawła: Trevano czy Castello? Kilka uwag na marginesie referatu Mariusza Karpowicza. In Sztuka XVII wieku w Polsce. Materiały Sesji Stowarzyszenia historyków Sztuki Kraków, grudzień 1993. Edited by Teresa Hrankowska. Warszawa: Arx Regia. Ośrodek Wydawniczy Zamku Królewskiego, pp. 315–21. [Google Scholar]

- Małkiewicz, Adam. 1997. Trevano czy Castello autorem ostatniej fazy budowy kościoła ŚŚ. Piotra i Pawła w Krakowie. Folia Historiae Artium 2–3: 91–108. Available online: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/fha1997/0095 (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Mossakowski, Stanisław. 2012. King Sigismund Chapel at Cracow Cathedral (1515–1533). Cracow: “Irsa” & Zamek Królewski na Wawelu–Państwowe Zbiory Sztuki. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski, Stanisław. 2021. Pałac Królewski na Wawelu w Czasach Zygmunta Starego. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Emilio. 1909. Ticinesi in Polonia. Bolletino Storico della Svizzera Italiana 31: 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Piechotkowie, Maria, and Kazimierz. 1999. Bramy Nieba. Bożnice Murowane na Ziemiach DAWNEJ Rzeczypospolitej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Krupski i S-ka. [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski Antoni T. 1984. Kaplica karmelitańska Matki Boskiej Piaskowej w Krakowie. Nieznane dzieło architekta królewskiego Jana Trevano. Biuletyn Historii Sztuki 46: 345–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rączka, Jan Władysław. 1983. Królewska rezydencja pałacowo-ogrodowa na Łobzowie. Stan Badań i zachowane źródła archiwalne (1585–1655), cz. 2. Teka Komisji Urbanistyki i Architektury 17: 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rożek, Michał. 1977. Mecenat Artystyczny Mieszczaństwa Krakowskiego w XVII Wieku. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Rożek, Michał. 1980. Katedra Wawelska w XVII Wieku. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. [Google Scholar]

- Solarz, Olga. 1960. Nieznane źródło do historii przebudowy Pałacu Wawelskiego za panowania Zygmunta III Wazy. Studia do Dziejów Wawelu 2: 455–61. [Google Scholar]

- Straty archiwów i Bibliotek Warszawskich w Zakresie Rękopiśmiennych Źródeł Historycznych. vol. 1: Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych. Stedelski, Adam, ed. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Szablowski, Jerzy. 1965. Katalog zabytków sztuki w Polsce, Wawel. part 1. IV vols. Warszawa: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkowicz, Stanisław. 1900. Włosi kupcy w Krakowie w XVII i XVIII wieku. Rocznik Krakowski 3: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkowicz, Stanisław. 1908. Wawel. Tom I. Zabudowania Wawelu i ich dzieje. Teka Grona Konserwatorów Galicji Zachodniej 4: 345–48. Available online: https://jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl/dlibra/publication/208728/edition/197452/content (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Tomkowicz, Stanisław. 1912. Przyczynki do Historii Krakowa w Pierwszej Połowie XVII w. Lwów: Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa dla Popierania Nauki Polskiej. [Google Scholar]

- Trezzini, Celestino. 1934. Trevani (Trevano). Historisch–Biographisches Lexikon der Schweiz 7: 45–46. Available online: https://biblio.unibe.ch/digibern/hist_bibliog_lexikon_schweiz/Tinguely_Ungarn_001_139.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Wagner, Katarzyna. 2020. Mieszczanie i Podatki. Nierówności Majątkowe w Wybranych Miastach Korony w XVII Wieku. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, Marek. 2013. Trewani a Cassaragi Franciszek. In Słownik Biograficzny Oficerów Polskich Drugiej Połowy XVII wieku. 1 vol. Oświęcim: Wydawnictwo Napoleon V, p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Witusik, Adam Andrzej. 2000. Pamiętna Unia Lubelska 1569. In Lublin w Dziejach i Kulturze Polski. Edited by Adam Andrzej Witusik and Tadeusz Radzik. Lublin: Polskie Towarzystwo Historyczne Oddział w Lublinie, Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza-Lublin: pp. 115–24. Available online: http://dlibra.umcs.lublin.pl/dlibra/docmetadata?id=478&from=publication (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Wrede, Marek. 2013. Rozbudowa Zamku Królewskiego w Warszawie przez Zygmunta III. Warszawa: Arx Regia. [Google Scholar]

- Wrede, Marek. 2019. Itinerarium króla Zygmunta III 1587–1632. Warszawa: Semper. [Google Scholar]

- Zlat, Mieczysław. 2010. Sztuka Polska. Tom 3. Renesans i Manieryzm. Warszawa: Arkady. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).