Abstract

The article examines the War in Heaven scene depicting the Fall of the Rebel Angels in the 1200s Anglo-Norman group of illustrated Apocalypse manuscripts, key in the development of Apocalypse illustration as far as quality, quantity, and art historical heritage are concerned. The iconography of the crucial War in Heaven scene shows a variety in the manuscript group; the compositions, divided into three well-defined groups at Satan’s pivotal moment of defeat, are depicted in three principal compositional types: one manuscript group focuses on the narrative of the battle, the second fuses the battle and its victorious result, and the third type focuses on the victory itself. The article establishes further subgroups on the basis of compositional similarities, and results occasionally strengthen or weaken existing theories about the traditional grouping of the manuscripts. The highlighted iconographical similarities provide new material for the reconsideration of the manuscripts’ artistic relations and dating.

1. Introduction

“Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon. And the dragon and his angels fought back, but he was defeated, and there was no longer any place for them in heaven.”1

Revelations 12:7-9, telling of the expulsion of a dragon from Heaven by angels under the leadership of St Michael the Archangel, is one of the handful biblical passages associated with the apocryphal Fall of the Rebel Angels lore.2 The New Testament idea that God permits evil but only for a short period is also the core message of the Book of Revelations, which turns the War in Heaven scene into a key moment in Apocalypse imagery. This is the moment of final defeat for Satan, who appears in the form of a dragon. The intertwining of the Fall of the Angels tradition and the biblical passage is traceable in textual and visual sources from the early Middle Ages on, and the present essay explores its visual imagery in the so-called Anglo-Norman or Anglo-French group of illustrated Apocalypse manuscripts. This manuscript group is a defining milestone in the history of Apocalypse illustration in terms of quality, quantity, and artistic heritage. The present article aims to move research forward on the relative dating of the manuscripts through a quest for iconographical similarities within the War in Heaven scenes.

2. Source Material

Anglo-Norman illustrated Apocalypses stem from a long development in manuscript illumination; the Apocalypse itself was a rare topic in art before Christianity’s establishment as a state religion in 391. The emergence of Apocalypse motifs in fifth- and sixth-century Rome started roughly in parallel with the allegorisation of the Book of Revelations, following the exegeses of Tyconius and Augustine (Klein 1992, p. 165). Even though Romanesque art started to combine individual Apocalypse scenes with a ‘synthetic rather than narrative’ approach (Klein 1992, p. 169), the multifigure War in Heaven scene remained a rare topic of monumental art3 and became more preferred in manuscript illumination. The richest Apocalypse illustrations embrace lavishly illustrated manuscript cycles with astonishing detail, among them the Anglo-Norman manuscript group.

The appearance of the earliest illustrated Apocalypse in England happened in Northumbria at around 700.4 The Venerable Bede, who also wrote an Apocalypse commentary, recorded that Benedict Bishop, the Abbot of Monkwearmouth, had acquired Revelations images in Rome and placed them on the north wall of his church. Nevertheless, no followers of this early Northumbrian Apocalypse have been found yet. The Gothic English tradition seems to be independent from the Early Medieval English beginnings,5 and there is no consensus in scholarship concerning the reasons for the reappearance of illustrated Apocalypse cycles in mid-thirteenth century England.6

Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts continued to be produced from c. 1250 until c. 1280, forming the First Wave of English Apocalypse illustration. Early members of the group are picture books, commonly followed by rectangular images crowning a double-register text in later pieces. Besides the text of the Book of Revelations, the manuscripts often include scenes from the apocryphal life of John or images representing the deeds of the Antichrist. The language of the manuscripts is Latin, Anglo-Norman, or Old French; many of them include extracts from the extensive Berengaudus Apocalypse commentary. Little is known about the author of the latter, although the text has been preserved in numerous nonillustrated copies in English monastic libraries since c. 1100. The Berengaudus commentary presents the Book of Revelations as a text referring to past, present, and perhaps prophetically even to the future;7 the commentary also elaborates on the importance of preaching and penance.8

Previous research has more or less consistently grouped Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts on the basis of their dating, origin, stylistic and iconographical similarities. (Table 1.) The Paris Apocalypse (Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale de France fr. 403, c. 1250–55) forms arguably the earliest group together with two picture books, namely, the Morgan Apocalypse (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library M.524, c. 1255–60) and the Bodleian Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library Auct. D.4.17, c. 1255–60). The latter two manuscripts contain Latin excerpts from either the Berengaudus commentary or Revelations, set as image captions on scrolls accompanying tinted drawing pictures. The French commentary of the Paris Apocalypse, meanwhile, closely follows that of a Bible Moralisé, with the text of the Revelations given in Anglo-Norman French. The manuscript’s two-column text with a crowning rectangular miniature layout also became the typical choice of later Anglo-Norman Apocalypses.

Table 1.

Common chronological and stylistic grouping of Anglo-Norman illustrated Apocalypse manuscripts.

The roughly contemporary second group is generally referred to as the Metz-Lambeth group in scholarship, signalling two subgroups stemming from two different prototype manuscripts. Both prototypes go back to the same lost Archetype of the entire Anglo-Norman group, supposedly a picture book produced in the 1240s (Morgan 1990, pp. 41–42). The Metz Apocalypse (Metz, Bibliothéque Municipale MS Salis 38, c. 1250–55), destroyed in a bombing in 1944, is the earliest combination of the Berengaudus commentary with the double-register text plus rectangular image format. The Tanner Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library Tanner 184, c. 1250–55) is supposed to derive from the same prototype as Metz. Full colouring substitutes earlier tinted drawings in the Lambeth Apocalypse (London, Lambeth Palace Library MS 209, c. 1264–67), the relatively well-defined dating of which has also served as a signpost for the dating of other Anglo-Norman Apocalypses and this subgroup’s lost prototype.9 Two further Apocalypses are attributed to the workshop of the Lambeth Apocalypse, namely, the Gulbenkian Apocalypse (Lisbon, Gulbenkian Museum L.A. 139, c. 1265–70) and the Abingdon Apocalypse (London, British Library Add. 42555, c. 1270–75), which might have relied on Lambeth for a model. As we see below, the Cambrai Apocalypse (Le Labo—Cambrai Bibliothéque Municipale MS 422, 1260) might also belong to this subgroup.

Although they are not supposed to be the product of the same workshop, iconographic and stylistic similarities are easy to spot between the Eton Apocalypse (Eton College Library MS 177, c. 1260–70) and Lambeth Palace Library MS 434 (c. 1250–60, hereafter: Lambeth 434).10 These two manuscripts also belong to the earlier Anglo-Norman Apocalypses, although their closer dating falls between the Metz and Lambeth subgroups.

Members of the fourth group, often referred to as the Westminster group in scholarship, are all associated with Westminster Abbey and royal patronage, but differ in layout and content. Four manuscripts belong here: British Library MS Add. 35166 (c. 1260, hereafter: BL 35166), where the War in Heaven scene is omitted; the Getty or Dyson Perrins Apocalypse (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum MS Ludwig III 1, c. 1255–60); the Douce Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library Douce 180, c. 1265–70); and Paris Bibliothéque Nationale lat. 10474 (c. 1270–90, hereafter: BNF 10474) (Morgan 2007, pp. 21–30).

Lastly, the luxurious Trinity Apocalypse (Cambridge, Trinity College MS R.16.2, c. 1255–60) stands apart from any other Anglo-Norman Apocalypse by way of its uniquely large size and unusual format. Its images, varying in size, are also set in varying positions within the text.11 Stylistic similarities were detected with the Paris and Tanner Apocalypses, but also with Trinity College MS B.10.6 (hereafter: TC 10.6, c. 1270–80), the Apocalypse that had famously belonged to Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury and leader of the English Reformation. The Trinity Apocalypse contains a French version of the Berengaudus commentary accompanying the text of Revelations.

Revelations 12:7-12 is interpreted in the Berengaudus commentary as the battle fought by Christ for the salvation of souls through the Passion and His death. Saint Michael represents Christ, and his angels are explained as the apostles who spread the Word through preaching. With a notoriously anti-Judaic exegetical commentary, the text identifies the dragon’s fallen angels with the Jews who persecuted and killed Christ and the apostles, together with other pagans and demons. Satan’s fall is expected to bring revenge upon the Jews and other nonbelievers for crucifying Christ. I know about only one attempt made at the comparative examination of images representing this scene. In search of the common archetype of the manuscript group, Suzanne Lewis argued that this lost common source contained "an archetypal text division that ignored the logical separation of the conflict from its outcome, by fusing the battle and fall into a single complex and dynamic pictorial narrative, followed by a static moment of victory, as in Getty. The meaning of the resultant illustrations was no longer self-evident, causing Morgan to divide the text further into three […] actions. Only Trinity, because it maintained the integrity of the subtext for 12:7-12, managed to provide a coherent visual account of the consecutive actions […], but the contrasting reactions of heavenly celebration and […] satanic rage, which were […] developed in the Morgan and Westminster manuscripts and which are essential to understanding the subsequent episodes of Revelations 12, are […] in Trinity […] lost (Lewis 1995, pp. 126–27).

Lewis’ concise summary is, in accordance with the overall approach of her volume, limited to the examination of the manuscripts containing the Berengaudus commentary. At the same time, it introduces a very important division of the images to those representing the battle and those depicting its result. Accordingly, Revelations 12:7-12 is often divided into two scenes in Apocalypse illustration: the War in Heaven in verses 7-9 and the Fall of Satan in verses 10-12. Lewis indicated that their merge in the manuscripts complicates the iconographical interpretation. The present essay takes on that challenge and narrows the focus to the War in Heaven scene in verses 7-9, but extends the range of examined manuscripts to the full Anglo-Norman Apocalypse group. Once we examine a wider group of manuscripts with a narrower focus, the more subtle compositional alterations turn into signposts for the steps of the iconographical development and the relative dating of the manuscripts.

The iconographical analysis of the War in Heaven scene inevitably touches upon the Fall of the Angels iconography as the wider art historical context.12 Belief in the expulsion of rebelling angels from Heaven easily gained popularity by providing an explanation for the origin and demise of evil, associating both with angels. No wonder the story was expounded by the early Fathers, remained on the schedule of theologians throughout the Middle Ages, and progressed into heretical movements as well (Quay 1981; Colish 1995; Iribarren and Lenz 2008; Chase 2002; Auffarth 2004a, pp. 192–223; all with further bibliography). The popular but rather complex theological issue became common in manuscript illumination from Ottonian art,13 enriching art and art history with an unusually wide variety of compositional arrangements. Fall of the Angels representations often vary so much that only the conventional characters, Saint Michael and his angels vs. Lucifer and his angels are constant. Their distributions within the pictorial space hardly resemble one another, which probably also contributes to the lacuna of a comprehensive iconography. Iconographical case studies outweigh systematising approaches.14 Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts, however, provide a well-defined group of images and textual environment where patterns can be traced, and compositional groups can be established.

3. Discussion: Battle on the Edge of Heaven

The Anglo-Norman Apocalypse images representing the War in Heaven scene divide into three large groups that do not fully conform to their traditional groupings. If Suzanne Lewis’ proposition concerning the archetypal fusion of the War in Heaven and Fall of Satan scenes is correct, she is also right in indicating the difference between the archetypal composition and that of the Morgan Apocalypse. The Morgan Apocalypse separates the War in Heaven scene from the Fall of Satan, but it is by far not alone with this choice among the early manuscripts.

3.1. Group 1—Focus on the Battle

The Morgan Apocalypse belongs to the first iconographical group of the War in Heaven scene (1), which embraces compositions showing the battle still in progress on the edge of Heaven. The Apocalyptic dragon has not yet fallen, the heavenly sphere is not separated from Earth in the image, the drama is unfolding in front of the viewer’s eyes, and Heaven opens up in the pictorial space. Within this first iconographical group, Subgroup 1.1 consists of the three very similar images in the early Paris-Morgan-Bodleian group. Three angels are fighting merely one large-scale dragon in these compositions, which means they slightly divert from the text of Revelations. The latter refers to ‘the dragon and his angels’, but the fallen angels are missing from these images.

The other participants of the battle are nonetheless all present. The larger St. Michael in the middle is identified by the inscription Sanctus Michael above the halo in the Bodleian Apocalypse. In the Morgan image, this inscription is partly hidden behind the Archangel’s halo, while it is completely missing from the Paris Apocalypse (Figure 1). The Paris composition lacks any inscription, while Apocalypse 12:7-8 is written on the image between Michael and the right angel in the Morgan and Bodleian Apocalypses (Figure 2). An angel armed with a sword and a shield is leaning down from a cloud delineated by two curlicue lines in all three images, helping his angelic colleagues in combat. Their enemy, the apocalyptic dragon, is larger than any angel and it is winged (as all dragon figures in the images examined here). One of the dragon’s seven heads is situated at the end of a coiling tale and is being stabbed by a third angel on the left. Meanwhile, Michael is about to pierce through the first crowned dragon head in the middle, though the crown is missing in the Paris Apocalypse. In accordance with their slightly later dating, the Morgan and Bodleian compositions overall show more compositional similarities.

Figure 1.

Paris Apocalypse (Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France MS fr.403). Fol. 20r, c. 1250–55, © Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Figure 2.

Bodleian Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Auct D.4.17). Fol. 8v, c. 1255, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

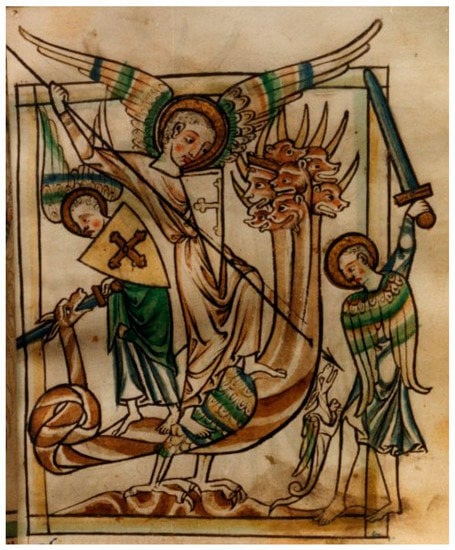

Subgroup 1.2 of images showing the battle in its heated process consists of those compositions where the Revelations’ reference to the dragon’s angels manifests in a second, smaller-scale dragon also fighting the three angels. Two manuscripts follow this pattern and together they form the Eton-Lambeth 434 group in scholarship. Even without any identifying inscription, the larger angel in the middle is identifiable as Saint Michael in both images, piercing through a large dragon again. The dragon’s now eighth head at the end of the tail is once again fighting a smaller angel on the left—the tail-head perhaps slightly seceding from the tail in Eton. Meanwhile, the angel on the right is striking down a second, smaller-scale dragon, which is gripping the angel’s mantle. The left hand of the right angel is missing in both images, a detail further supporting the idea of the two manuscripts being related.

A brownish area delineates perhaps a little hill or another slightly elevated surface under the feet of this right angel in the Eton image, and under the dragon in Lambeth 434 (Figure 3). Its brownish colour perhaps suggests that the dragon is already fallen to Earth, in contrast with the previous subgroup. Neither of the two Apocalypses contain commentaries, however, and the Revelations text accompanying the two images is limited to sections of Revelations 12:7-9. This suggests that the intention, similarly to the first subgroup, was to represent the battle, i.e., only the War in Heaven scene, without Revelations 12:10, the Fall of Satan.

Figure 3.

Lambeth 434 (London, Lambeth Palace Library MS 434). Fol. 18r, c. 1250–60, by permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

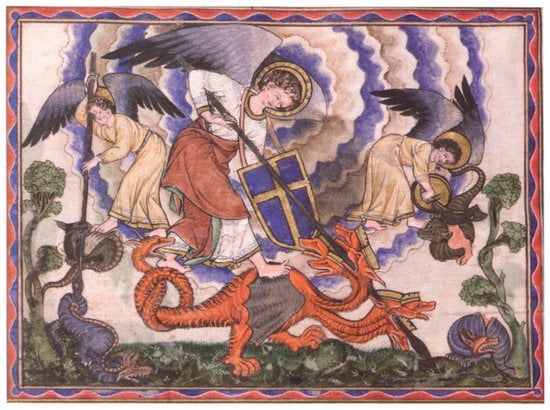

These two relatively simple compositions share this detail with the luxurious Trinity Apocalypse (Figure 4), which alone forms the third subgroup of War in Heaven scenes focusing on the battle in progress (1.3). The iconography of this exceptional manuscript is unique at the War in Heaven scene either. With four angels fighting four dragons, angels do not outnumber dragons anymore. Four angels and four dragons are fighting in pairs, as though we are witnessing a series of chivalric duels. This detail is indeed a major step ahead for the sinister side, and not only brings the Trinity image closer to the text of the Book of Revelations but also lends dramatic excitement to the battle. The equal number of angels and dragons suggests that the result of the battle between good and evil is still difficult to predict.

Figure 4.

Trinity Apocalypse (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.16.2). Fol.13v, c. 1255–60, © The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Compositional symmetry is also reinterpreted in Trinity. Saint Michael and his dragon are still situated towards the centre, but they are now the second couple from the left in the iconographical narrative. Every head of the Archangel’s dragon is surrounded by halos composed of tiny circles, a detail that the Trinity composition shares with the Paris-Morgan-Bodleian subgroup (and with the also early Tanner Apocalypse, analysed below). The seven heads, however, now twist up steeply, like in the Eton-Lambeth 434 group, apparently to leave space for the duels of two more angel and writhing dragon couples on the right. As opposed to the two previous subgroups, the Archangel’s seven-headed dragon has no proper tail-head in Trinity. The left angel’s small dragon being situated just above the end of the primary dragon’s tail, however, looks as though the old tail-head has now fully seceded and grown out into a separate dragon.

Trinity also contains the longest text accompanying the War in Heaven scene among Anglo-Norman manuscripts. It quotes and interprets Revelations 12:7-12, including both the War in Heaven and the following Fall of Satan scenes. The Fall of Satan, however, is not visually depicted in the War in Heaven image. Rich as the Trinity picture cycle seems to be, the Fall of Satan is not given a scene in the manuscript at all. Nonetheless, one last detail that the Trinity composition shares with the Paris-Morgan-Bodleian subgroup is an inscription in the upper right corner, where Revelations 12:10 appears on a ribbon coming out of the mouth of a head. This verse announces the Fall of Satan, which drifts the Trinity composition towards the second larger group of Anglo-Norman War in Heaven Apocalypse scenes.

3.2. Group 2—Battle and Victory

The second large group of War in Heaven scenes in Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts consists of compositions displaying both the battle and its glorious result. Only two Apocalypse manuscripts belong to this group: the early Getty Apocalypse (Figure 5) and TC 10.6 (Figure 6), currently dated at least a decade later. Their similarity at this scene is all the more intriguing as they are typically not aligned in the above-mentioned traditional grouping of the manuscripts in scholarship.

Figure 5.

Getty or Dyson Perrins Apocalypse. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum MS Ludwig III.1, Fol. 20v, c. 1255–60. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Figure 6.

TC 10.6. (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS B.10.6) Fol.19r, c. 1270–80. © The Master and Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge.

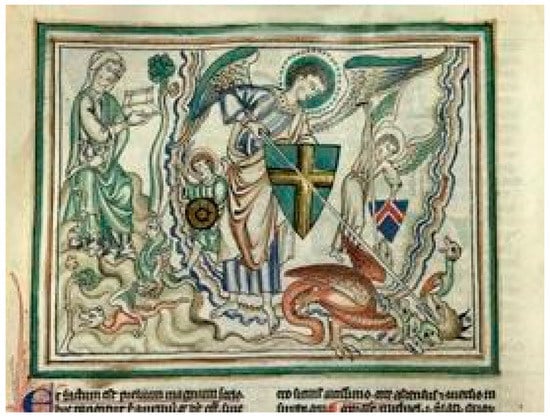

Similarly to the Trinity Apocalypse, the Getty Apocalypse is a luxurious manuscript, and the number of fighting angels and dragons in the War in Heaven scene is once again equal. The battle is again depicted as a series of chivalric duels. Although Saint Michael and his large, red, six-headed dragon are again situated in the middle, they are hardly the most exciting couple from an iconographical point of view. The Archangel’s dragon is again equipped with a tail-head, but the angel on the left is not fighting the tail-head in Getty. The left angel is fighting a smaller-scale dragon situated right above the tail-head, in a position similar to the one seen in the Trinity image above. The Getty Archangel’s large dragon also raises its heads to leave space for the events happening on the right, and to direct attention to a more gripping detail: the third angel on the right is fighting the tail-head of a third winged dragon. The angel is forcefully pushing this dragon down with a spit fork grabbed in both hands, and the front half of the dragon’s body is already under the earth, out of the pictorial sphere. This dragon, therefore, is already fallen. The image can be interpreted as the Fall of Satan fused into the War in Heaven scene, which is also supported by the Revelations text accompanying the Getty image.15

Taking into consideration that, in all compositions examined here, only one, the largest, dragon is equipped with a tail-head, this similarity makes one wonder if the same dragon is represented twice. Perhaps we witness a narrative: the dragon first being fought and finally cast down. However, the angels fighting the two dragon figures are not the same: they differ in their size, clothing, the colour of the wings, and even in their weapons. The left dragon has only one head without horns, as opposed to the six horned heads of the dragon under Saint Michael’s feet. What we witness, therefore, is either three different dragons or two dragons fought by three different angels. In the former scenario, the equal number of angels and dragons would be another similarity with the Trinity Apocalypse (1.3). In the latter case, the three angels vs. two dragons distribution would be reminiscent of the Eton-Lambeth 434 subgroup (1.2) above, but unique among the compositions examined so far, with a narrative of the events depicted in one composition, which fuses the War in Heaven with the Fall of Satan.

A further similarity between the Getty image and the Eton-Lambeth 434 subgroup is the attempt to represent space. Given that the upside-down dragon on the right is falling through a layer of circular lines in Getty, this bluish layer must imply the edge of Heaven, perhaps in the form of a bordering cloud. John is watching the events through a hole in the frame on the right, apparently having a vision of Heaven while still being on Earth. The slightly hilly, greyish area of earthly realms under John’s feet is clearly differentiated from the blue curlicue lines bordering Heaven inside the frame. In other words, the viewer joins John in glancing into Heaven and watches a fierce battle all the way to the final triumph, the Fall of Satan.

The Fall of Satan as the result of the War in Heaven is also depicted in the TC 10.6 composition. Similarly to the Trinity Apocalypse, TC 10.6 depicts four angels and four dragons fighting duels, but Saint Michael and his seven-headed dragon with the extra tail-head are now the leftmost couple. Roughly in the middle of the composition, a second, smaller angel is combatting the tail-head of a dragon depicted upside down in a position that mimics the fallen Getty dragon. On the basis of the similar green and white pattern, and the wings, the falling TC 10.6 dragon is identifiable with the dragon fought by Saint Michael. By all probability, the same dragon is depicted twice, like in the Getty Apocalypse, fighting and falling in a narrative sequence.

Two more very small dragon figures also appear above the tail-head in TC 10.6, depicted in a fight with two larger angels. The identification of these dragons with the one fighting Saint Michael and then falling out of Heaven is prevented by the same problem that we also saw in the Getty composition: they have only one head, as opposed to the seven heads of Saint Michael’s dragon. The three dragons can hardly represent the same figure, therefore. They rather function as subsidiary figures representing the fallen angels mentioned in Revelations 12:7, participating in the War in Heaven but finally overthrown together with Satan.

The TC 10.6 image nonetheless merges one more scene into the composition, unique among the Anglo-Norman manuscripts. An angel in the sky is holding a book, and another angel is leaning down from a cloud to a winged figure standing; more precisely, it is hovering above the ground on the right. The figure’s head is covered with a blue veil, suggesting that she is female and could be identical with the Woman of the Apocalypse who receives wings in Revelations 12:14, quoted right above the image. Therefore, the TC 10.6 composition, uniquely among the Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts, fuses the War in Heaven both with the Fall of Satan and the Apocalyptic Woman Receiving Wings scenes.

3.3. Group 3—Focus on the Victory

The third and last, quite bountiful group of War in Heaven scenes consists of images that direct attention to the result as opposed to the actual process of the battle. This group embraces six Apocalypse images where a curlicue half-circle delineates the border of the heavenly sphere and keeps all dragons outside. These dragons are now clearly fallen. Besides the standard participants of the War in Heaven, the members of this manuscript group insert additional figures into the compositions and divide into three subgroups on the basis of these subsidiary figures.

Subgroup 3.1 contains only the arguably earliest Anglo-Norman illustrated Apocalypse, the Tanner Apocalypse (Figure 7), where the curlicue borderline of Heaven extends from the upper left corner to approximately half of the image. Two angels are visible on the edge of the heavenly sphere, the larger one on the left is identifiable as Saint Michael piercing his lance into the only dragon in the image. The Tanner dragon is situated outside Heaven, depicted upside down, with its head disappearing in a position similar to those seen in Getty and TC 10.6. The Tanner dragon does not have a head at the end of its tail, however. The text accompanying the scene quotes both the War in Heaven and Fall of Satan, confirming that the Tanner image was intended to fuse the two scenes with a stronger focus on the latter.

Figure 7.

Tanner Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Tanner 184). Fol. 66v, c. 1250–55, ©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

The Tanner composition features two subsidiary figures. John is watching the scene on the right, represented as a bearded man with a halo and a book in his left hand. The sphere of the angels and the dragon is well-differentiated from the area where John is standing, reminding the viewer that John is having a vision. The other subsidiary figure is watching the events from Heaven, and only his head and shoulders appear behind the curlicue borderline of Heaven between John and the angels. This figure has a halo but no wings; the colour of the halo and the clothing differentiates him from both John and the angels. Given that the text accompanying the image is Revelations 12:7-12, this figure could perhaps utter the voice announcing the victory in verse 10. For any case, there is no parallel for this figure in other Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts; the entire Tanner composition is, indeed, rather unique among them.

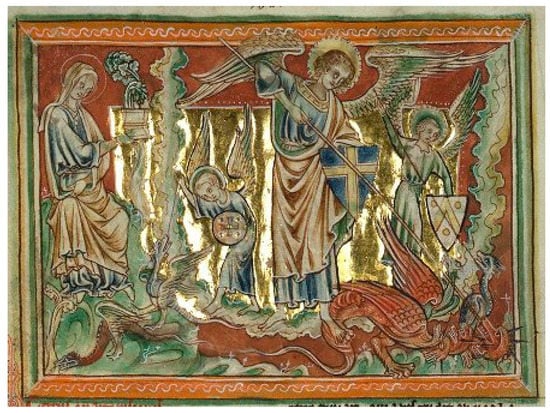

The identification of subsidiary figures is less problematic in case of the second subgroup (3.2) of images highlighting the result of the battle. War in Heaven compositions in the Cambrai (Figure 8), Lambeth (Figure 9), Gulbenkian, and Abingdon (Figure 10) Apocalypses differ only in smaller details, such as weapons missing from the hands of angels in the latest member of the subgroup, the perhaps unfinished Abingdon composition. The heavenly sphere, delineated again with a curlicue line separating at least half of the pictorial space, appears on the right in these manuscripts. Now, three angels are visible in Heaven, the larger Saint Michael in the middle is endowed with an unusual three pairs of wings in the Abingdon Apocalypse. Each angel is duelling one fallen dragon, but the differences between the dragon figures render it unlikely that the same dragon would be represented multiple times in a narrative sequence in these images.

Figure 8.

Cambrai Apocalypse (Le Labo—Cambrai Bibliothéque Municipale MS 422). Fol. 47v, c. 1260, « cliché: IRHT-CNRS ».

Figure 9.

Lambeth Apocalypse (London, Lambeth Palace Library MS 209). Fol. 15v, c. 1264–67, by permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

Figure 10.

Abingdon Apocalypse (© British Library Board MS Add. 42555). Fol. 66v, c. 1270–75.

Every single dragon is depicted outside Heaven. Similarly to the Tanner Apocalypse, Satan has already fallen in these images, and victory has been achieved. The texts accompanying the images also merge the two scenes as the manuscripts quote Revelations 12:7-12 and the relevant section of the Berengaudus commentary. Outside Heaven, the fallen dragons share the space of a woman sitting under a tree and reading a book on the far left, who shows little concern for the heated battle. These compositions, therefore, also fuse the War in Heaven and Fall of Satan with the Woman in the Wilderness scene, immediately preceding the War in Heaven episode in Revelations.

The third subgroup of images focusing on the result of the battle (3.3) closes the present iconographical overview with the Douce Apocalypse (Figure 11) and BNF 10474 (Figure 12). Both manuscripts delineate the heavenly sphere with a particularly well-developed curlicue borderline flourishing in multiple layers in the centre of the composition. Once again, three angels appear fighting, with the larger Archangel situated in the middle; but neither image features subsidiary figures besides the participants of the battle. The angels’ sinister opponents nonetheless differ in the two manuscripts.

Figure 11.

Douce Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 180). Fol. 44r, c. 1265–70, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Figure 12.

BNF 10474 (Paris Bibliothéque Nationale MS lat. 10474), Fol. 22r, c. 1270–90, © Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Dragons now outnumber the angels in both images, increasing the turmoil on the heavenly battlefield. A smaller winged dragon on the left of the Douce image is biting the haft of a smaller angel’s spear just on the edge of Heaven. Beneath this dragon, another small dragon is lying under a tree, already cast down to Earth. On the right, another small angel is cutting into half a fourth dragon; and underneath this scene, a fifth dragon is cut in half under a tree. The trees, grass, and leaves surrounding the fallen dragons are rendered with a particularly high degree of naturalism. All dragons are clearly fallen out of Heaven, and we are witnessing the last minutes of the battle.

The differing colours again make it unlikely that the same dragon would be represented multiple times in the Douce Apocalypse, which is a marked difference from the corresponding, uncoloured image in BNF 10474. Saint Michael’s dragon, i.e., Satan himself, remarkably appears twice in the latter image: the same large, seven-headed dragon with a crown on each head and a tail-head appears in the middle and the left side of the composition. This dragon is still within Heaven amid the fight with the Archangel in the centre; it is falling out of Heaven upside down, being pushed down by a smaller angel on the left. Therefore, this composition also fuses the War in Heaven and Fall of Satan scenes, but in quite a unique way among the Anglo-Norman Apocalypses. The apocalyptic dragon is depicted in its entirety twice, with the full body visible in both cases.

Another unique detail is the variety in the rendering of fallen angel figures. Two more angels are fighting smaller dragons on the left and right sides of the heavenly border; and two more smaller scale dragons are falling out of Heaven upside down in the centre; while a fifth angel is leaning down from the bottom right corner of Heaven to fight an anthropomorphic demonlike figure, unprecedented in the Anglo-Norman Apocalypse compositions analyzed above. Instead of a dragon, this is a hairy demon with a tail. He seems to be winged, though the wing is partly hidden behind a fighting angel’s circular shield. Most importantly, and again in a unique way in the Anglo-Norman Apocalypses, this demon has a weapon: he is trying to attack the angel with a bow. A second, very similar demon figure armed with a sword appears outside Heaven, in the centre of the foreground between two upside-down falling dragons. This demon is crawling on his knees, apparently having just landed on Earth. Considering that narrative depictions of the same figure repeated multiple times in one composition have been traced above in other members of the manuscript group, the possibility that here we witness the process of the two falling dragons turning into demons on earth must not be excluded.

This multicharacter image in BNF 10474, therefore, is the odd one out, even in the third group of Anglo-Norman War in Heaven scenes. On the one hand, it gives equal importance to the process and the result of the battle, similarly to the second Anglo-Norman Apocalypse group. On the other hand, its compositional arrangement with the thick curlicue lines delineating the edge of Heaven, relates it to the Tanner, Lambeth, Gulbenkian, Abingdon, Cambrai, and Douce Apocalypses; while the lack of subsidiary figures besides the participants of the battle links it more closely with Douce. The anthropomorphic demon figures, at the same time, also connect BNF 10474 to Gothic English illustrated Apocalypses produced towards the end of the 1200s (Paris Bibliothéque Nationale de France MS fr.9574; London, Lambeth Palace Library MS 75; and Oxford, New College MS D.65). They differ from the earlier Anglo-Norman group both stylistically and in their iconography, and prefer French Apocalypse commentaries. These equally fascinating manuscripts open the next chapter in English Apocalypse illustration.

4. Conclusions

This essay presented an iconographical analysis of the War in Heaven scene in the 1200s Anglo-Norman wave of Apocalypse illustration. On the basis of the division of the Revelations narrative to the battle and its result, three iconographical groups were established, divided into further subgroups on the basis of compositional similarities. Given that the study analysed only one scene in the Apocalypse narrative, it did not aim to reshuffle the traditional grouping of the manuscripts in scholarship, but it may draw attention to previously perhaps unnoticed subtleties hiding in the details, which may indicate directions for future research.

Scholarship commonly divides the manuscripts into four main groups on the basis of iconographical and stylistic similarities. The first is formed by three early manuscripts, namely, the Paris (c. 1250–55), Morgan (c. 1255–60), and Bodleian (c. 1255–60) Apocalypses. Within the second, the Metz-Lambeth group, the War in Heaven scene of the early Tanner Apocalypse (c. 1250–55) is supposed to derive from a different prototype than that of the Cambrai (c. 1260), Lambeth (c. 1264–67), Gulbenkian (c. 1265–70), and Abingdon (c. 1270–75) Apocalypses. The third group embraces the Eton Apocalypse (1260–70) and Lambeth 434 (c. 1250–60). The War in Heaven scenes of the fourth, so-called Westminster group, embellish the Getty or Dyson Perrins Apocalypse (1265–70), BNF 10474 (1270–90), and the Douce Apocalypse (1265–70). The last traditional group is formed by the Trinity Apocalypse (c. 1255–60) and the perhaps related TC 10.6 (1270–80).

The iconography of the War in Heaven scene slightly diverts from traditional manuscript groupings. The first, the Paris-Bodleian-Morgan group, nevertheless remains intact, as all three manuscripts depict only the battle in three very similar compositions without giving away the result. This subgroup shares parts of their compositional arrangement with the Eton Apocalypse and Lambeth 434, which also do not announce the result of the battle. The Trinity Apocalypse does not either, which largely differs from other manuscript in the iconography of the War in Heaven scene.

TC 10.6 is unique among the Anglo-Norman Apocalypses in merging the Woman Receiving Wings scene with the War in Heaven. The closest iconographical relative of this image appears to be the Getty Apocalypse inasmuch as these compositions render both the battle and its result in a narrative sequence within the same image. Satan, i.e., the largest dragon figure, is depicted twice: once in the middle of a duel and once in the process of falling down from Heaven after losing.

The earliest appearance of this falling dragon motif occurs in the Tanner Apocalypse. Despite its early dating, this manuscript depicts the War in Heaven in a markedly different way from the also early Paris-Morgan-Bodleian subgroup. Tanner also witnesses the earliest appearance of the characteristic curlicue borderline delineating the heavenly sphere in the Lambeth line of the Metz-Lambeth group. The Lambeth, Gulbenkian, Abingdon, and Cambrai Apocalypses also include the Woman in the Wilderness in the War in Heaven image scene. By representing the fallen dragons outside the heavenly sphere, these manuscripts focus less on the battle and more on its result, similarly to the Tanner Apocalypse.

The Douce Apocalypse and BNF 10474 form the closing subgroup by situating Heaven in the compositional centre and lacking subsidiary figures supporting the main participants of the battle. While Douce, however, focuses on the result of the battle and shows multiple dragon figures outside Heaven; BNF 10474 fuses the battle and its result. This latest Anglo-Norman illustrated Apocalypse concludes the analysis with the most developed demonology, depicting, uniquely in the Anglo-Norman group, fallen angels also in the form of anthropomorphic demon figures (Table 2).

Table 2.

Grouping of Anglo-Norman illustrated Apocalypse manuscripts on the basis of the War in Heaven iconography examined in the article.

Differences between the two lists may indicate further as-yet unexplored relationships between the Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts. The Paris-Morgan-Bodleian, Metz-Lambeth, and Eton-Lambeth 434 groups also remain consistent in their iconography in the case of the War in Heaven scene; the Trinity Apocalypse also stands apart from the other manuscripts. TC 10.6, however, relates more to the Tanner and Getty Apocalypses than to Trinity, perhaps signalling a common line of iconographical development. Indeed, the early Tanner Apocalypse may have influenced the Metz-Lambeth and Westminster groups, and TC 10.6, and sets the Getty Apocalypse apart from other members of the Westminster group. It is just a matter of time before research finds out whether these relationships are limited to the War in Heaven scene or extend to other scenes within Anglo-Norman Apocalypse manuscripts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | ‘Standard English Bible Translation’ in The Bible Gateway Searchable Online Bible https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelation+12&version=ESV accessed 1 December 2021. |

| 2 | Further biblical passages alluding to various versions of the Fall of the Rebel Angels include Genesis 6:1-4, Isaiah 34:4, John 8:44, 2 Peter 2:4, Jude 6. For a list of variations of the Fall of the Angels narrative see (Godwin 1990, pp. 81–99). For a list of apocalyptic and sapiential writings referring to the Fall of the Angels, see (Stuckenbruck 2004; Lichtenberger 2004). |

| 3 | For Revelations 7 among the iconographical types of Saint Michael the Archangel, see (Rohland 1977, pp. 114–25; Harrison 1993; Trotta and Renzulli 2003). |

| 4 | Although there are no complete cycles preserved from the earliest period, Apocalypse manuscripts may have been based on Late Antique—Early Christian works. The first extant cycles are early medieval manuscripts; the influence of exegesis became significant with the appearance of Beatus manuscripts written in Asturia at the end of the eighth century. Cycles in the Romanesque style date from the ninth until the sixteenth century with various derivatives. Gothic cycles also embrace the Continental and Trecento cycles besides the Anglo-Norman group. Apocalypse manuscripts also appeared in the form of block-books in the Netherlands around 1425–50. (Klein 1992, pp. 175–99). |

| 5 | Morgan (2005); Morgan (2007, pp. 10–20). For general overviews of Gothic Apocalypses and the Anglo-Norman manuscript group see, for instance, (Morgan 1988, pp 16–19; McKitterick 2005, pp. 3–22). |

| 6 | The presence of a French Bible Moralisée in the country might have inspired their production; growing interest in Apocalypse illustration in the period could also be related to patronage and readership (Gee 2002; Morgan 2002; Alexander 1983). |

| 7 | This interpretation could have also been supported by natural disasters and military invasions happening in the period by writings on the Antichrist or problems within the Church (McGinn 1998). |

| 8 | Given that both preaching and penance are core elements of Franciscan teaching, the influence of the royally patronised Franciscans was mentioned among the possible factors behind the choice of the Berengaudus commentary. Joachim of Fiore, whose prediction of the end of the world for 1260 was associated with Revelations 9, was also popular among the Franciscans. For a selection of Joachim of Fiore’s relevant writings and those of the Joachite Movement before 1260, and writings from Franciscan spirituals and the Fraticelli, see McGinn (1998). |

| 9 | The text of the Revelations and the commentary are followed by 28 additional images in the Lambeth Apocalypse, and the lady kneeling before the Virgin in the last image (Fol. 53r) was identified as Lady Eleanor De Quincy, Countess of Winchester. The manuscript is dated between her first marriage to Roger De Quincy, Earl of Winchester, and her second marriage to Roger de Leybourne. (Morgan 1988, p. 103). |

| 10 | These features and the iconography suggest that the source of this manuscript might have been a late Spanish Beatus Apocalypse. The possible patron might have been a woman appearing out of context in certain images, perhaps Eleanor of Castile (1241–1290) or Eleanor de Montfort (1252–1282) (McKitterick 2005). |

| 11 | See Note 10. |

| 12 | Enoch I (Ethiopic Enoch, 200 B.C.—60 B.C.) is possibly the earliest source calling the Devil a fallen angel. The sin attributed to the angels and eventually causing their fall turned from lust to the envy of God and pride in Jewish apocalyptic literature (Russell 1981). |

| 13 | Fall of the Angels representations are also common in Creation cycles, relating to an exegetical tradition that conceived the Fall of the Angels as an event preceding the creation of man, and the creation of man with the aim to fill the places left vacant by fallen angels. St. Augustine in the City of God wrote that angels were created at the same time as the light on the first day of Creation, which paralleled the Fall of the Angels with the separation of light from darkness. The manuscript types where the representation of the Fall of the Angels in Creation cycles is common include the Bible Moralisèe and the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Pinson 1995). |

| 14 | For instance, (Kirschbaum 1990, 642 ff.; Dodgson 1931; Polzer 1981; Medicus 2003; Auffarth 2004b). |

| 15 | A dragon with the head(s) under the earth is also depicted in the Dragon Chained and Led to Prison scenes, e.g., in the Tanner, Bodleian, Trinity, Eton, Lambeth 434, and Abingdon Apocalypses. The Berengaudus commentary identifies this figure as the fallen Satan. |

References

Primary Sources

Abingdon Apocalypse (London, British Library MS Add. 42555).Bibliothéque Nationale MS lat. 10474, Paris.Bodleian Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Auct D.4.17).Cambrai Apocalypse (Le Labo—Cambrai Bibliothéque Municipale MS 422).Douce Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Douce 180).Eton Apocalypse (Eton, Eton College Library MS 177).Getty orDyson PerrinsApocalypse (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum MS Ludwig III.1) fol. 20v, c. 1255–60.Gulbenkian Apocalypse (Lisbon, Gulbenkian Museum MS L.A.139).Lambeth Apocalypse (London, Lambeth Palace Library MS 209).Lambeth Palace Library MS 434, London.Morgan Apocalypse (New York, Pierpont Morgan Library MS M.524).Paris Apocalypse (Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale de France MS fr.403).Tanner Apocalypse (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Tanner 184).Trinity Apocalypse (Cambridge, Trinity College MS R.16.2).Trinity College MS B.10.6, Cambridge.Secondary Sources

- Alexander, Jonathan James Graham. 1983. Painting and MS illumination for Royal Patrons in the later Middle Ages. In English Court Culture in the Later Middle Ages. Edited by John Scattergood. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Auffarth, Christoph. 2004a. Angels on Earth and Forgers in Heaven: A Debate in the High Middle Ages Concerning Their Fall and Ascension. In The Fall of the Angels. Edited by Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 192–223. [Google Scholar]

- Auffarth, Christoph. 2004b. The Invisible Made Visible: Glimpses of an Iconography of the Fall of the Angels The Invisible Made Visible: Glimpses of an Iconography of the Fall of the Angels. In The Fall of the Angels. Edited by Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, Steven. 2002. Angelic Spirituality. Medieval Perspectives on the Ways of Angels. New York: Paulist Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colish, Marcia L. 1995. Early Scholastic Angelology. Recherches de Théologie Ancienne et Médiévale 62: 80–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, Campbell. 1931. School of Dürer: “The Fall of the Rebel Angels”, fragment of a cartoon for stained glass. Old Master Drawings 5: 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Loveday Lewes. 2002. Women, art and patronage from Henry III to Edward III, 1216–1377. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, Malcolm. 1990. Angels. An Endangered Species. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Dick. 1993. The Duke and the Archangel. A Hypothetical Model of Early State Integration in Southern Italy through the Cult of Saints. Collegium Medievale 6: 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Iribarren, Isabel, and Martin Lenz, eds. 2008. Angels in Medieval Philosophical Inquiry. Their Function and Significance. Hampshire: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum, Engelbert, ed. 1990. Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie. Rome: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Peter K. 1992. The Apocalypse in Medieval Art. In The Apocalypse in the Middle Ages. Edited by Richard K. Emmerson and Bernard McGinn. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 159–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Suzanne. 1995. Reading Images. Narrative Discourse and Reception in the Thirteenth/Century Illuminated Apocalypse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberger, Herman. 2004. The Down-Throw of the Dragon in Revelation 12 and the Down-Fall of God’s Enemy. In The Fall of the Angels. Edited by Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 119–47. [Google Scholar]

- McGinn, Bernard. 1998. Visions of the End. Apocalypstic Tradition in the Middle Ages. New York: Columbia University. [Google Scholar]

- McKitterick, David, ed. 2005. The Trinity Apocalypse (Trinity College Cambridge, MS R.16.2). London: The British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Medicus, Gustav. 2003. Some observations on Domenico Beccafumi’s two Fall of the Rebel Angels panels. Artibus et historiae 47: 209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Nigel. 1988. A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles. Early Gothic Manuscripts (II) 1250–1285. London: Harvey Miller. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel. 1990. The Lambeth Apocalypse. Manuscript 209 in Lambeth Palace Library. London: Harvey Miller Publisher. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel. 2002. Patrons and Devotional Images in English Art of the International Gothic. In Reading Texts and Images. Essays on Medieval and Renaissance Art and Patronage. Edited by Bernard J. Muir. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel. 2005. Illustrated Apocalypses of mid-thirteenth-century England: Historical Context, Patronage and Readership. In The Trinity Apocalypse (Trinity College Cambridge, MS R.16.2). Edited by David McKitterick. London: The British Library, pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Nigel. 2007. The Douce Apocalypse. Picturing the End of the World in the Middle Ages. Oxford: University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Quay, Paul M. 1981. Angels and Demons: The Teaching of IV Lateran. Theological Studies 42: 20–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinson, Yona. 1995. Fall of the Angels and creation in Bosch’s Eden: Meaning and iconographical sources. In Flanders In A European Perspective: Manuscript Illumination around 1400 in Flanders and Abroad. Edited by Sharon Macdonald. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 693–705. [Google Scholar]

- Polzer, Joseph. 1981. ‘The ‘Master of the Rebel Angels’ reconsidered. The Art Bulletin 63: 563–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rohland, Johannes Peter. 1977. Der Erzengel Michael: Arzt und Feldherr. Zwei Aspekts des Vor- und Frühbyzantinischen Michaelskultes. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton. 1981. Satan: The Early Christian Tradition. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckenbruck, Loren T. 2004. The Origins of evil in Jewish Apocalyptic Tradition: The Interpretation of Genesis 6:1–4 in the Second and Third Centuries B.C.E. In The Fall of the Angels. Edited by Christoph Auffarth and Loren T. Stuckenbruck. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 87–118. [Google Scholar]

- Trotta, Marco, and Antonio Renzulli. 2003. La grotta garganica: Rapporti con Mont-Saint-Michel e interventi longobardi. In Culte et pèlerinages à Saint Michel en Occident: Les trois monts dédiés à l’archange. Edited by André Vauchez, Pierre Bouet and Giorgio Otranto. Rome: École Française de Rome, pp. 427–88. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).