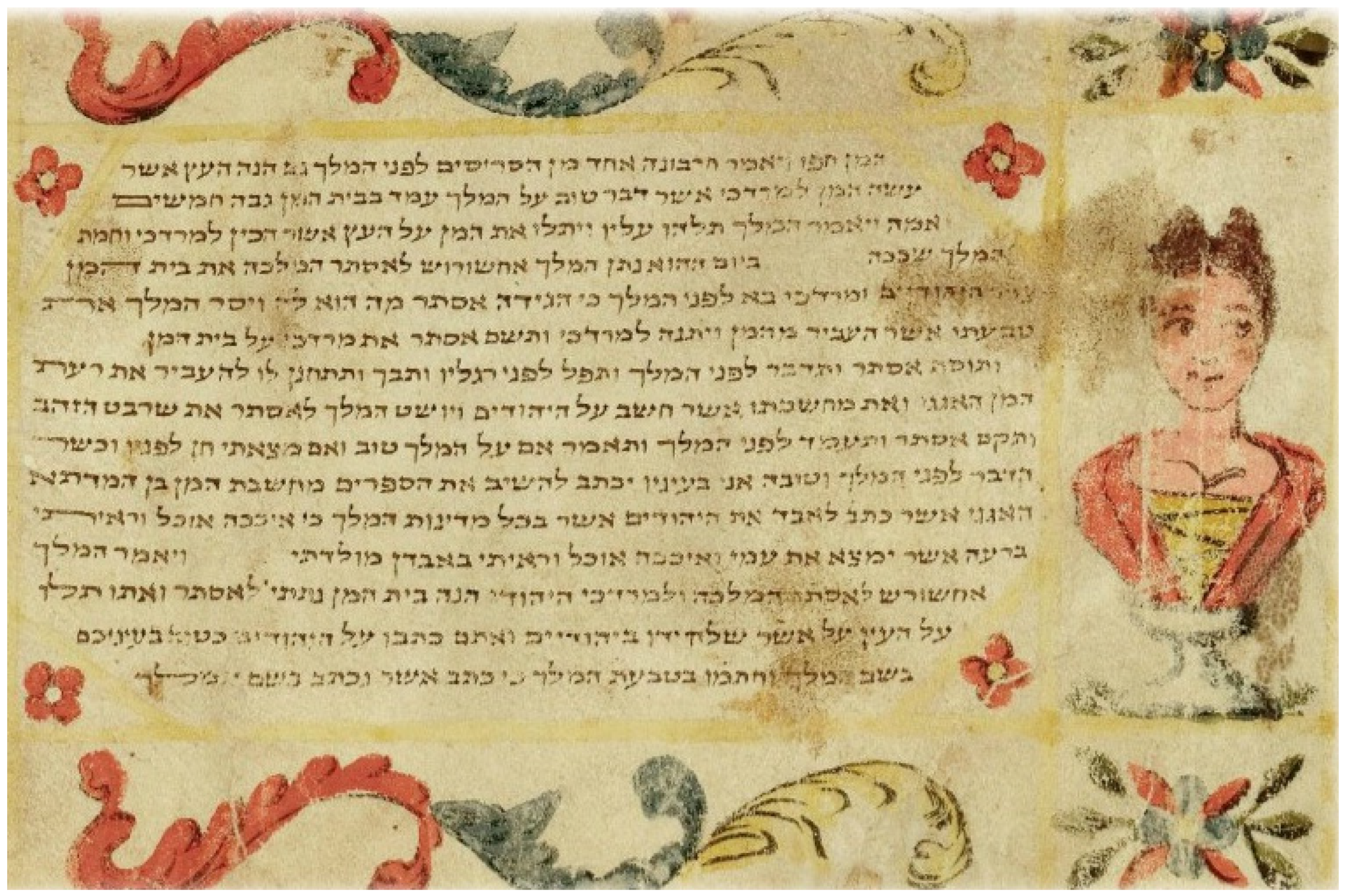

Between Queen Esther and Marie-Antoinette: Courtly Influence on an Esther Scroll in the Braginsky Collection

Abstract

:“Each column of text is bordered above and below by bands of scrolling vines. Lively figures, several shown strolling with walking sticks in hand and others gesturing, are interspersed with human busts, owls, and a gargoyle. These fanciful images appear to bear no specific relationship to the Esther story”.

“This teaches [us] that the wicked Vashti would take the daughters of Israel, and strip them naked, and make them work on Shabbat.… The verse states: ‘But the Queen Vashti refused to come’ (Esther 1:12). The Gemara asks: Since she was immodest, as the Master said above: The two of them had sinful intentions; what is the reason that she did not come? … The angel Gabriel came and fashioned her a tail”.(Babylonian Talmud Megillah 12.2)

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | On the relation between Christian art and Esther scrolls see Carruthers (2020); Epstein (2015); Mann and Chazin (2007); Sabar (2012); Wiesemann (2014). |

| 2 | On the website of The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, Object ID: 35194: https://cja.huji.ac.il/gross/browser.php?mode=set&id=35194, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 3 | On the website of The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, Object ID: 39595: https://cja.huji.ac.il/gross/browser.php?mode=set&id=39595, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 4 | On the website of The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, Object ID: 200: https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=200, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 5 | Klagsbald (1981); and on the website of The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, Object ID: 34758: https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=set&id=34758, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 6 | On Sotheby’s website https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2006/important-judaica-including-property-from-the-jewish-community-of-amsterdam-nihs-n08266/lot.186.html, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | On a critical edition of Midrash Esther Rabbah see Tabory and Atzmon (2014). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Félix Lecomte, Marie-Antoinette, 1783, marble, h. 86 cm, Versailles, Château de Versailles et de Trianon. |

| 15 | Deitsch and Liberman Mintz, “Esther Imagined,” 268. On this phrase, see Apperson (2006). See also (Freddy and Weyl 1977). I thank the anonymous reviewer for this reference. |

| 16 | See image on the website of The Bezalel Narkiss Index of Jewish Art, Object ID: 34758: https://cja.huji.ac.il/browser.php?mode=alone&id=328143, accessed on 13 January 2022. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 |

References

- Apperson, G. L. 2006. The Wordsworth Dictionary of Proverbs. Ware: Wordsworth Reference. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Jo. 2020. The Politics of Purim: Law, Sovereignty, and Hospitality in the Aesthetic Afterlives of Esther. London: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Deitsch, Elka, and Sharon Liberman Mintz. 2009. Esther Imagined: Second Half of the Eighteenth Century Alsace. In A Journey through Jewish Worlds: Highlights from the Braginsky Collection of Hebrew Manuscripts and Printed Books. Edited by Evelyn M. Cohen, Sharon Liberman Mintz and Emile G. L. Schrijver. Amsterdam: Bijzondere Collecties, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Zwolle: Distributed by Waanders, pp. 268–69. [Google Scholar]

- Doerflinger, Marguerite. 1979. Découverte Des Costumes Traditionnels en Alsace. Colmar-Ingersheim: Editions SAEP, pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, Anne E., Donald Haase, and Helen Callow. 2016. Folktales and Fairy Tales: Traditions and Texts from around the World. Santa Barbara: Greenwood, pp. 124, 293, 350–53, 480. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Marc Michael. 2015. Skies of Parchment, Seas of Ink: Jewish Illuminated Manuscripts. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freddy, Raphaël, and Robert Weyl. 1977. Juifs en Alsace: Culture, Société, Histoire. Toulouse: Privat, p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Gindin, Tamar Eilam. 2016. The Book of Esther Unmasked. Kefar Sava: Zeresh Books, p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Elliot, and Evelyn Cohen. 1990. In Search of the Sacred: Jews, Christians, and the Ritual of Marriage in the Later Middle Ages. Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 20: 225–49. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, Elliot. 1986. ‘The Way We Were’: Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. Jewish History 1: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idem. 2014. Marriage Rituals Italian Style: A Historical Anthropological Perspective on Early Modern Italian Jews. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Idem. 2015. The Portrait Bust and French Cultural Politics in the Eighteenth Century. Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Klagsbald, Victor. 1981. Catalogue Raisonné de la Collection Juive du Musée de Cluny. Paris: Musée des Thermes et de l’Hôtel de Cluny, pp. 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Vivian B., and Daniel D. Chazin. 2007. Printing, Patronage and Prayer: Art Historical Issues in Three Responsa. Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture 1: 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, Peter, ed. 2017. A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion. In 4 In the Age of Enlightenment. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, Ronit. 2012. Decent Exposure: Bosoms, Smiles and Maternal Delight in Pre-Revolutionary French Busts. Sculpture Journal 21: 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offenberg, Sara. 2019. Up in Arms: Images of Knights and the Divine Chariot in Esoteric Ashkenazi Manuscripts of the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: Cherub Press, pp. 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Orgad, Zvi. 2020. Prey of Pray: Allegorizing the Liturgical Practice. Arts 9: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raphael, Freddy. 2004. Popular Art of the Jewish Communities in Alsace at the Time of their Entry into the Modern Period. Studia Rosenthaliana 37: 133–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Aileen. 2002. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715–89. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Sabar, Shalom. 2012. A New Discovery: The Earliest Illustrated Esther Scroll by Shalom Italia. Ars Judaica 8: 119–36. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, Debra Higgs. 2003. Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 136–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tabory, Joseph, and Amnon Atzmon, eds. 2014. Midrash Ester Rabbah: Critical Edition. Jerusalem: Schechter Institute, pp. 117, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, Benjamin. 1851. Northern Mythology, Compromising the Principal Traditions and Superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands: Compiled from Original and Other Sources, 3 Vols. London: Edward Lumley, vol. II, pp. 148–58. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Caroline. 2006. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Holt, pp. 95–96. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Roni. 2006. Gift Exchanges during Marriage Rituals among Italian Jews in the Early Modern Period: A Historic-Anthropological Reading. Revue des Etudes Juives 165: 485–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesemann, Falk. 2014. The Esther Scroll. Cologne: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, R. Turner. 2011. Folk and Festival Costume: A Historical Survey with Over 600 Illustrations. Mineola: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Zika, Charles. 2017. Recalibrating Witchcraft through Recycling and Collage: The Case of a Late Seventeenth-Century Anonymous Print. In The Primacy of the Image in Northern European Art, 1400–1700: Essays in Honor of Larry Silver. Edited by Debra Cashion, Henry Luttikhuizen and Ashley West. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 391–404. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Offenberg, S. Between Queen Esther and Marie-Antoinette: Courtly Influence on an Esther Scroll in the Braginsky Collection. Arts 2022, 11, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020040

Offenberg S. Between Queen Esther and Marie-Antoinette: Courtly Influence on an Esther Scroll in the Braginsky Collection. Arts. 2022; 11(2):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020040

Chicago/Turabian StyleOffenberg, Sara. 2022. "Between Queen Esther and Marie-Antoinette: Courtly Influence on an Esther Scroll in the Braginsky Collection" Arts 11, no. 2: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020040

APA StyleOffenberg, S. (2022). Between Queen Esther and Marie-Antoinette: Courtly Influence on an Esther Scroll in the Braginsky Collection. Arts, 11(2), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020040