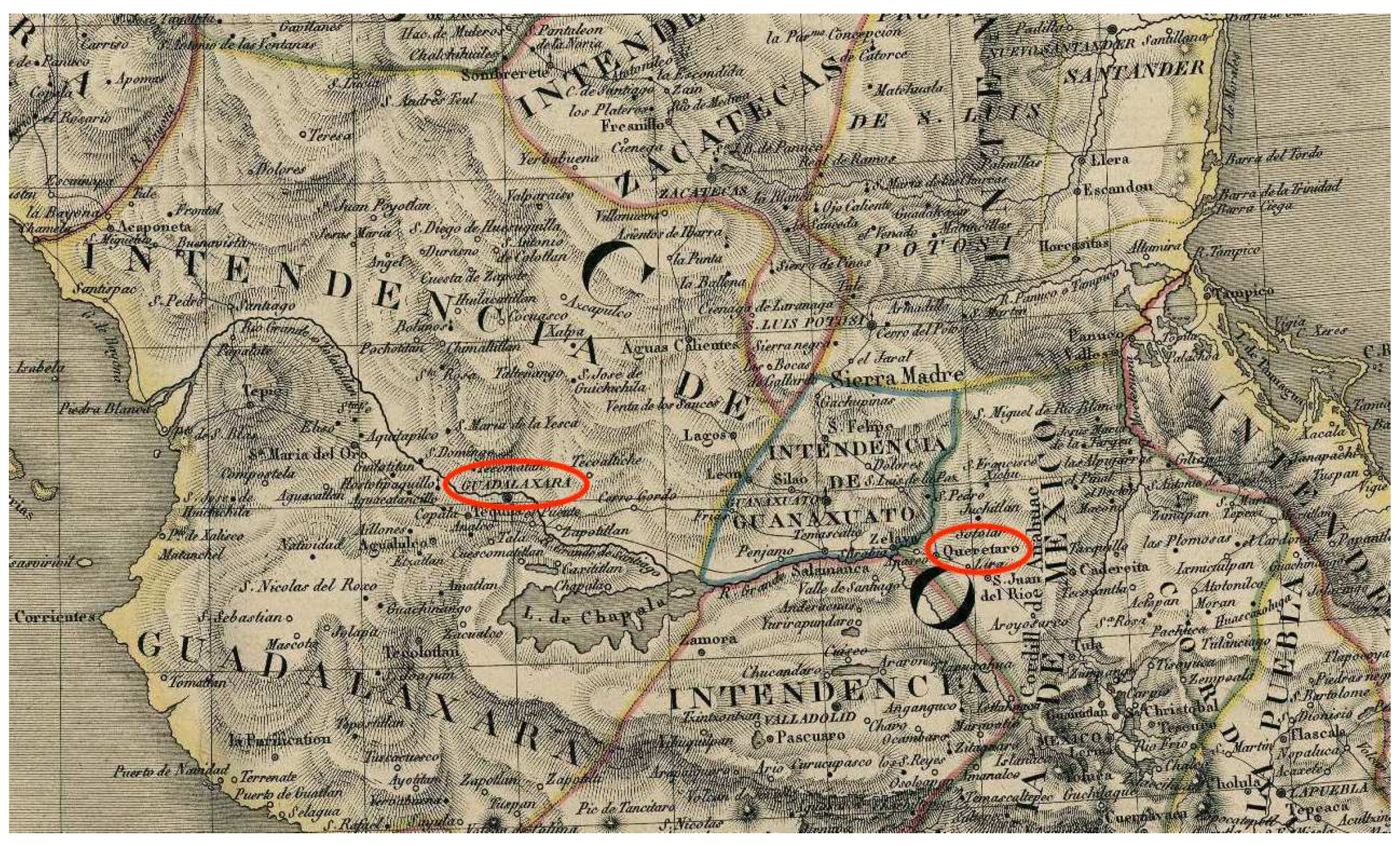

Grain Architecture in Bourbon New Spain: On the Design of Guadalajara and Querétaro’s Alhóndigas

Abstract

1. Introduction: Granaries in Late Colonial Mexico

“I have seen that it [the old granary] is extremely deteriorated, both in its ceilings and in its walls, because some are collapsing and others, like those of its patio, completely fallen to the floors, momentarily threatening an irreparable ruin, thus making it uninhabitable.”(AGN, Alhóndigas, vol. 1, exp. 4, fol. 41)

2. Alarife Pedro José Ciprés and the Plans for Guadalajara’s Alhóndiga

3. Magnificent Granaries: Alhóndigas in Querétaro and the Bajío Region

Bonavía’s comments were consistent with the assessment of contemporary architects and academicians. Spanish mathematician and architect Benito Bails, whose book Elementos de matemática (published in 1783 and reprinted in 1796) was key to the architectural curriculum and study plans implemented in the Mexican Academy, argued that “Public buildings, on being so necessary in a large city that without them it would cease to be comfortable, also contribute greatly to its beauty, both for their grandeur and for the profusion with which the most [of them] are usually adorned” (Bails 1783, p. 808). Furthermore, he strongly advocated for the utility of public granaries, which he described as one of the essential public buildings, and provided some practical recommendations on their construction, mostly oriented to a better preservation of the stored grain.“Public works are always useful, even if there is something of excess in them, they are the true magnificence of the nations, and if there is any favorable luxury, undoubtedly it is this one, the only one capable of uniting simplicity in its demeanor, sobriety, and good habits. I cannot be indifferent in the service to the king, and the public, not just in the province I am heading but even in the last corner of the monarchy. I do not foster what I expect to enjoy, I foster what I consider useful and necessary as I have always done when it goes beyond my limited authority.”(AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 25, exp. 10, fols. 333r–359v).43

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

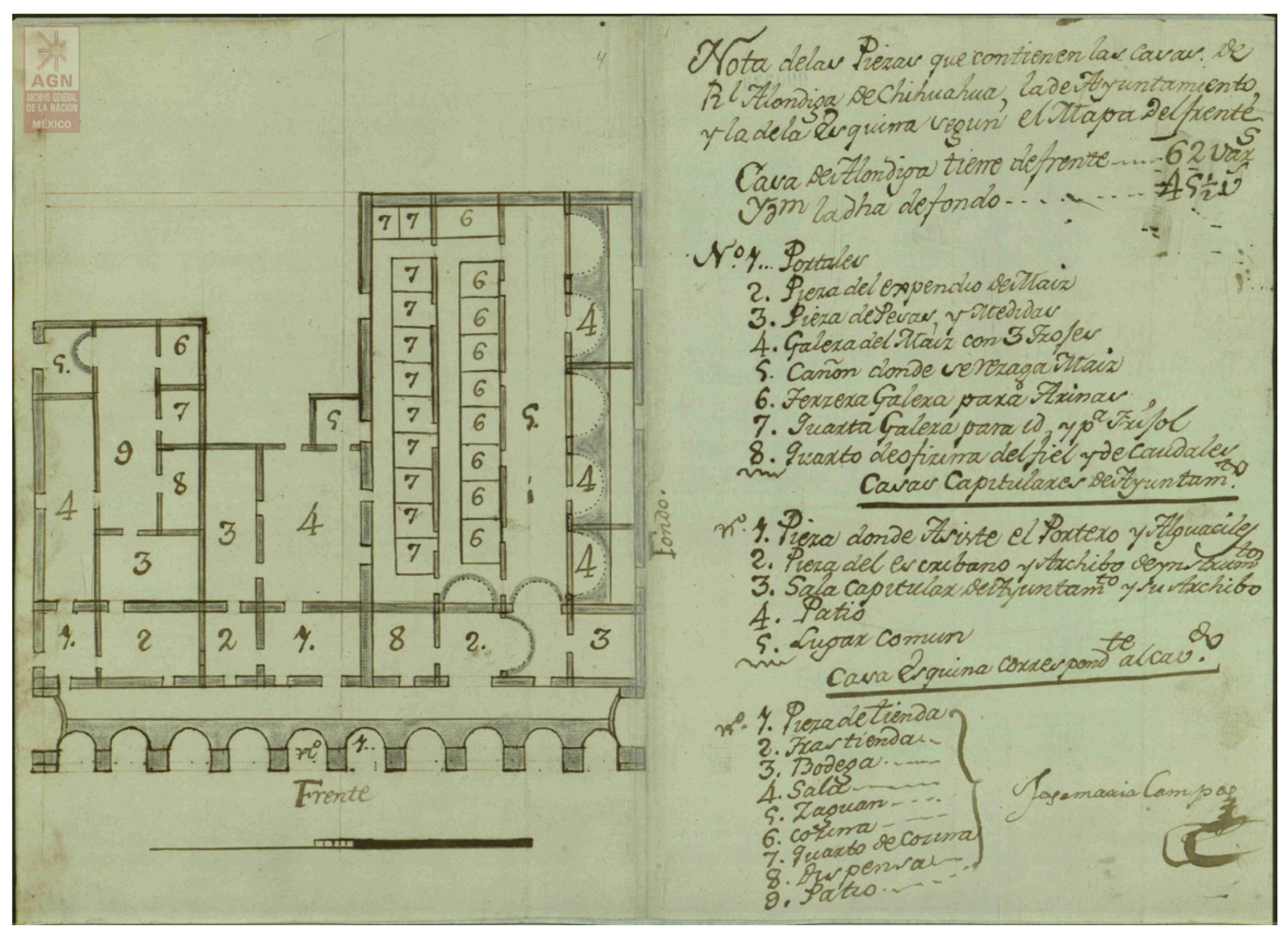

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The 1786 Real Ordenanza instructed the intendentes to inspect the state of the alhóndigas in their provinces, reiterating how cities and towns not only benefitted from these buildings that supplied grain and flour to the population but also to prevent the speculators’ malice. Therefore, replicating the royal legislation compiled in 1681, intendentes were ordered “to establish them in the large cities if they are convenient for the utility of the common [people]” and prepare the ordenanzas for their administration (Real Ordenanza 1786, pp. 83–84). |

| 2 | Pérez Calama’s letter was titled “Carta Histórica sobre siembras extemporáneas de maiz y otras precauciones para lo futuro contra la escasez” (Suplemento a la Gazeta de México 1786, pp. 185–92). |

| 3 | During his tenure as intendente in the province of Michoacán, Juan Antonio de Riaño befriended Pérez Calama. A few years later, after being appointed to the same post in Guanajuato, Riaño would implement these ideas with the building of a monumental granary, a vivid expression in the city of the Bourbon public works agenda. See (Gordo Peláez 2013). |

| 4 | “[…] every well-governed city should have public granaries of good construction and firmness, well protected from humidity, harmful airs, and excessive heat; to be cared for by people who knew how to preserve the grain from mice, birds and harmful insects, cleaning them from time to time […]” (toda ciudad bien gobernada debería tener graneros públicos de buena construcción y firmeza, bien defendidos de la humedad, de los ayres perjudiciales y del excesivo calor, que estuviesen cuidados por personas que supiesen preservar el grano de los ratones, de los pájaros y de los insectos perniciosos, limpiándolo de quando en quando) (Muratori 1790, pp. 215–16). Muratori’s treatise was first published in Italian in 1749, with copies of this and other writings by him circulating soon in Spain and Spanish America. A Spanish edition was printed in 1790. In Guanajuato, the city elite were familiar with Muratori’s ideas. For instance, the city’s customs administrator, José Pérez Becerra, owned a library of over 400 titles on history, philosophy, fine arts, and political science, among others. Two of Muratori’s writings (La Pública Felicidad and a 1790 Spanish edition of La filosofía moral declarada y puesta a la juventud) are listed in the inventory of books, therefore, placing Guanajuato at the center of the contemporary Bourbon reformist agenda (Bernstein 1946). |

| 5 | Archivo General de la Nación (AGN), Gobierno Virreinal, Bandos, vol. 14, exp. 23, fols. 59r–61v. 10 April 1786. See Torre Villalpando, Guadalupe. Compendio de Bandos de la Ciudad de México. Período Colonial. Mexico City, Dirección de Estudios Históricos, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2012. https://bandosmexico.inah.gob.mx/todos/1786_04_10.html# (accessed on 24 November 2021). |

| 6 | The Real Ordenanza (royal instructions) issued in 1786 for the government of the intendentes in New Spain also called for the idle and unemployed population to serve either in the provincial regiments or as part of the crew of warships and merchant ships or in the building of public works (Real Ordenanza 1786, p. 69). |

| 7 | In the 1950s, Mexican historian Luis Chávez Orozco first transcribed part of the documentation on colonial granaries held in Mexico City’s Archivo General de la Nación. |

| 8 | See “Plano ignografico de la ciudad de Guadalaxara de la Nueba Galicia que mandó hacer el Señor L[icenciad]o D[on] Martín de Blancas, oidor de ella para remitir a Su Majestad en su Real y Supremo Consejo de Indias, como Juez Superintendente del agua, que es hoy el dicho Señor de la que en al Ciudad se introdujo […]”, 1745. Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain [AGI], MP-MEXICO,153. http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/20986?nm (accessed on 20 December 2021). |

| 9 | “Alhóndiga de maíz, Guadalajara, Jal.”, 1793. AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones. |

| 10 | See “La Noble y Leal Ciudad de S[an] Luis Potosí, dividida en Quarteles de Orden Superior del Excelentísimo Señor Virrey Marqués de Branciforte. Diciembre 15 de 1794.” AGI, MP-MEXICO,456BIS http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/21386?nm (accessed on 20 December 2021). See also (Cordero Herrera 2013, pp. 309–68). |

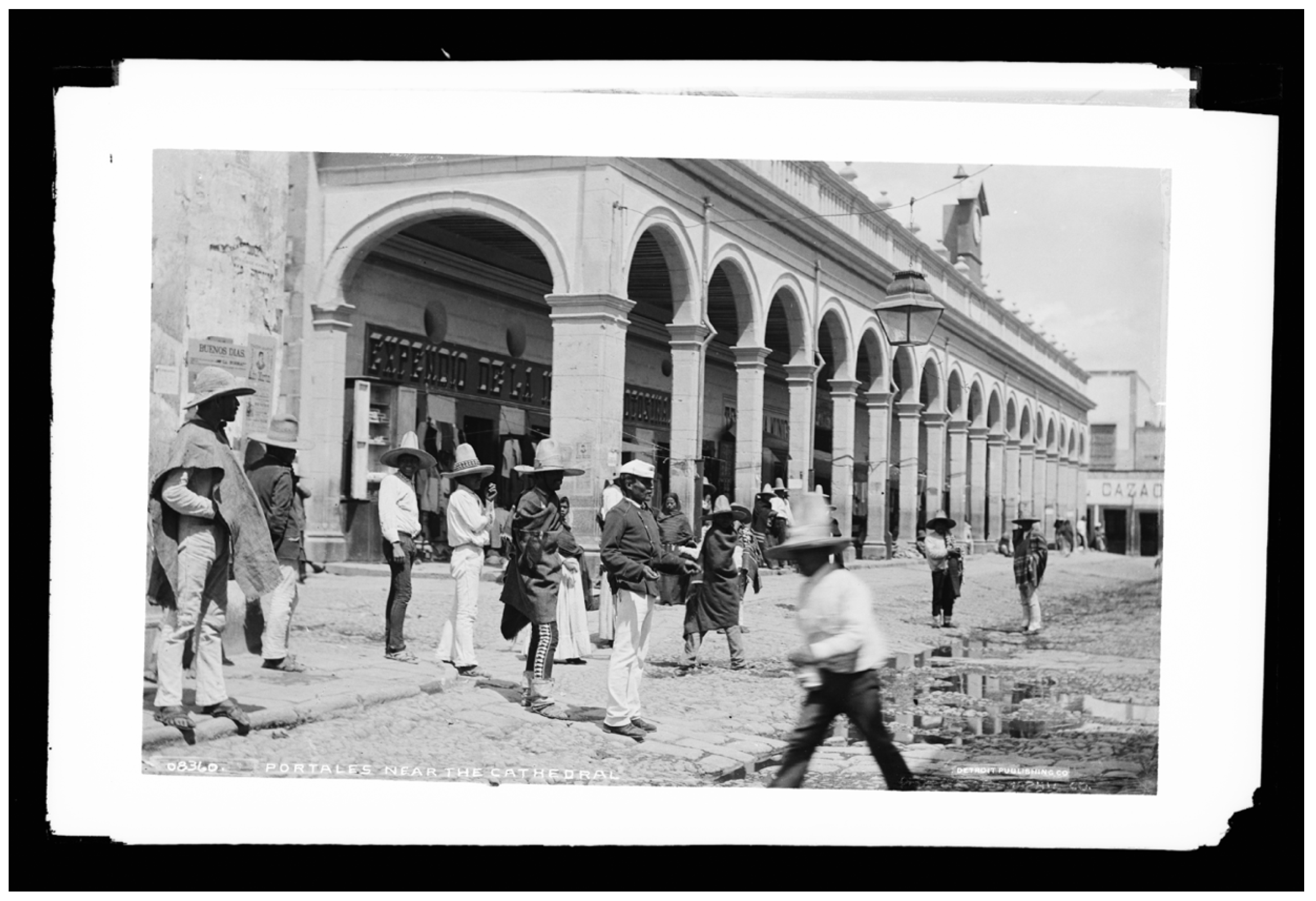

| 11 | By the late eighteenth century, the role of architecture in the production and reception of meaning, particularly as a built and visual metaphor of political authority on the urban space, had a long trajectory in the Spanish empire. To this end, art historians Michael Schreffler, Paul Niell, and C. Cody Barteet have explored varied built forms (physical structures or their visual and textual rendition) in early modern Mérida of Yucatán, Mexico City, and Havana, eloquently exposing how monumental façades played a key role in the shaping of Novohispanic urban fabrics and were a potent symbol of power and authority, tailored to the needs of a particular colonial audience and in a multicultural context in a state of continuous negotiation. See (Schreffler 2007; Niell 2015; Barteet 2019). |

| 12 | The city’s master mason, José María Campos, penned this small plan (30 × 41 cm) that identifies three sections in the same building, with their separate doorways, behind the arcade that runs across the façade. See “Alhóndiga de Chihuahua, Chih.”, 1800. AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones. |

| 13 | Although congregated within the same block, each building had its separate entryway. For instance, the granary’s doorway was open on the south side of the block, and inside, various rooms were organized around an arcaded square patio. |

| 14 | “Alhóndiga, cuartel de milicias y carnicería, Guadalajara, Jal.”, 16 December 1797. AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones. Both drawings differ in size. The “Plano Geométrico” is larger, at 59.3 × 47 cm, while the second plan measures 35 × 44.5 cm. In addition, Ciprés uses the same name (“Plano Geométrico”) in an earlier design, dated 1793. Yet, these two “Geometrical Plans” correspond to two different buildings and sites. |

| 15 | In his 1793 plan, Ciprés envisioned a granary of 84 by 42 varas, along with another attached smaller building for its administrator. |

| 16 | Ciprés described the old granary of Guadalajara as a building of 37 by 65 varas, with one courtyard, entrance hallway, 13 large storerooms, and the residence for the administrator (Chávez Orozco 1956, p. 46). |

| 17 | The 1793 Plano Geométrico proposed a total of 19 storerooms. |

| 18 | At its full capacity, the new alhóndiga of San Luis Potosí, concluded in 1777, was planned to hold up to 36,000 fanegas (Hernández Soubervielle 2013b, p. 209). |

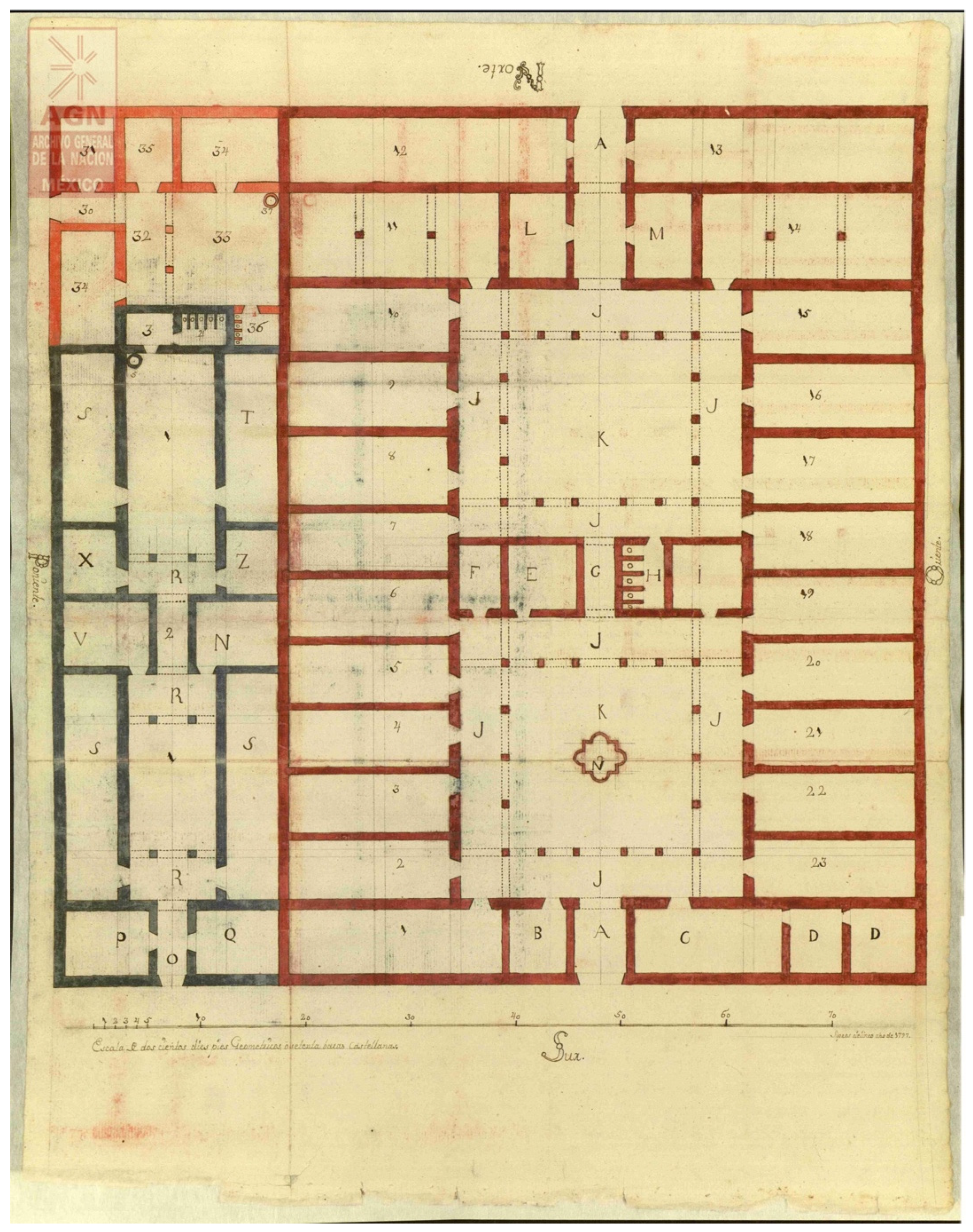

| 19 | This budget was a tenth of the initial cost of the granary planned in Guanajuato. Although contemporary, both alhóndigas were worlds apart. The topography of Guanajuato was a challenge for the granary builders. Additionally, the city’s cabildo aimed at building a colossal and new fabric, unprecedented in the grain architecture of New Spain. |

| 20 | José Gutiérrez (1766–1835) was a peninsular native, born in Málaga and educated both in Madrid and Mexico City where he entered the Royal Academy of San Carlos and graduated as academician of merit in architecture in 1794. His relation with this institution strengthened in the following two decades, collaborating as course instructor and as inspector of varied architectural projects in and near Mexico City. Persuaded by Guadalajara’s bishop Juan Cruz Ruiz de Cabañas, he arrived in the city in 1805 to teach at the local school of drawing and to direct the building of the Casa de la Misericorida (today’s Hospicio Cabañas), a home and shelter for orphans and invalids (Fuentes Rojas 2002, pp. 235–36; Ruiz Razura 2008). |

| 21 | As historian Vera Candiani has exposed, attempts to implement and embrace this visual language also permeated the massive infrastructure of Mexico City’s Desagüe (drainage project). See (Candiani 2014). |

| 22 | A similar sequence with two entrances, two interior courtyards, and a connecting corridor had been previously proposed by Ciprés in 1793 for the adaptation of the former house of bishop Rodríguez de Rivas for its function as granary. See “Alhóndiga de maíz, Guadalajara, Jal.”, 1793. AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones. |

| 23 | In this plan, the alhóndiga is depicted as one large, functional storeroom 41 varas long and 12 varas wide, with independent access from the north side of the building. See “Plano de la Alhóndiga, Casas Reales y Cárcel del Real de Bolaños,” 1753. AGI, MP-MEXICO,773. http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/21761?nm (accessed on 20 December 2021). |

| 24 | Prior to and after his designs for the alhóndiga, Ciprés worked in Guadalajara appraising private properties; inspecting and directing the paving and repair of streets, bridges, and the city’s aqueduct; and proposing some needed works in the city hall. Near the city, he was also involved in building windmills in the ojo de agua (spring of water) of the indigenous village of Mexicaltzingo and providing designs for bridges both near Guadalajara and in San Juan de los Lagos (AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 12, exp. 19, fols. 320–31; AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 12, exp. 21, fols. 348r–374v; BPEJ, Ramo Civil, caja 416, exp. 7, 1r–2v; Muñoz Andrade 2020, p. 26). Historiography has also repeatedly praised Ciprés’ contribution to the splendid church of San Felipe Neri in Guadalajara (Cornejo Franco et al. 1985, p. 156). |

| 25 | Although there is more research to be conducted on his education, we know that Ciprés owned a collection of 93 books at the time of his death in 1820 (Castañeda 2005, p. 234). This collection included, among others, copies of key treatises and publications on architecture, engineering, mathematics, and carpentry, such as the works of Vitruvius, Vignola, Sebastiano Serlio, Diego López de Arenas, Fray Lorenzo de San Nicolás, Tomás Vicente Tosca, Bernard Forest de Bélidor, Tomás Cerdá, and Benito Bails (BPEJ, Bienes Difuntos, caja 272, exp. 6, fols. 16v–17v). |

| 26 | Previous scholarship placed his origins, instead, in the nearby indigenous village of Mezquitán (Cornejo Franco et al. 1985, p. 156). Baptismal records identified the birth of Pedro Joseph on 29 June 1761. He was the son of José Joaquín Ciprés and María Ana Basilia Sánchez. He married several times and fathered, at least, half a dozen children in the 1790s and early 1800s, including Diego Martín Ciprés who followed in his father’s footsteps as a master builder (Ayón Zester 1988, p. 62). See also “México, Jalisco, registros parroquiales, 1590–1979,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9392-DV95-2X?cc=1874591&wc=3JWG-VZS%3A171935001%2C182938601%2C182974601: accessed on 28 June 2014), Guadalajara > Sagrario Metropolitano > Bautismos 1759-1765 > image 262 of 779; parroquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Jalisco; “México, Jalisco, registros parroquiales, 1590–1979,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9392-DV92-1J?cc=1874591&wc=3JWG-6TL%3A171935001%2C182938601%2C182997001: accessed on 9 August 2021), Guadalajara > Sagrario Metropolitano > Bautismos 1799–1806 > image 652 of 817; parroquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Jalisco; “México, Jalisco, registros parroquiales, 1590–1979,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9392-DVS9-ZR?cc=1874591&wc=3JWG-L29%3A171935001%2C182938601%2C183006001: accessed on 9 August 2021), Guadalajara > Sagrario Metropolitano > Bautismos 1810–1815 > image 104 of 695; parroquias Católicas (Catholic Church parishes), Jalisco. These church records form part of the collection of documents microfilmed by the The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and available at familysearch.org. |

| 27 | On the definition and titles of alarifes and other builders in colonial Mexico and the regulations of the building trade, see (Fernández 1986; Ortiz Macedo 2004, pp. 53–69; Burke 2021, pp. 92–95). |

| 28 | In 1801, upon request from Guadalajara’s Consulado (the merchants’ guild), Ciprés crafted several designs for two bridges over the Calderón and La Laja Rivers, to the east of the city, intended to facilitate the increasing commercial activity of the region. His plans were submitted to the San Carlos Academy in Mexico City for their evaluation by the director of architecture, Antonio González Velázquez (Terán 2017a, 2017b). |

| 29 | On the exam of the guild-certified maestros, the role of the city’s maestro mayor, and the architectural practice in the 1790s Mexico City, see (Schuetz 1987, pp. 81–121). |

| 30 | In 1785, he was examined by Joaquín Velázquez de León, director of New Spain’s Tribunal de Minería (Royal Mining Tribunal) and earned the title of perito medidor de minas (mining expert and surveyor). Along with his extensive surveying work, Oriñuela is associated with several designs of domestic architecture and public works, including Querétaro’s new alameda (tree-lined park). He was also instrumental in the project to create a local academy of mathematics in the 1790s, intended to reform and facilitate the instruction of this discipline in Querétaro. Motivated by the recent founding of Mexico City’s Royal Academy of San Carlos, Oriñuela’s proposal was contemporary to similar initiatives in other provinces of New Spain. For instance, a School of Drawing was first established in Guadalajara in 1790 and reformed and expanded a few years later to incorporate studies on arithmetic, geometry, and architecture. See (Boils Morales 1994, pp. 86–96; Ramírez Montes 2010; Camacho Becerra 1997, p. 61). |

| 31 | See “Real Alhóndiga de Querétaro, Qro,” 23 November 1795, 30.5 × 62.5 cm. AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones. |

| 32 | The idea of building a new granary in Zacatecas was first proposed by intendente Felipe Cleere soon after his arrival in the province in 1789, when he petitioned the authorities of the Real Audiencia of Nueva Galicia in Guadalajara for its construction (BPEJ, Ramo Civil, caja 202, exp. 25). A few months later, he proposed the construction of a new granary along with repairs to other public works. “Not having here [in Zacatecas] a subject capable of forming a map of the alhóndiga” (no habiendo aquí sujeto capaz de formar un mapa de la alhóndiga), Cleere asserted, he took matters into his own hands. Guided “by some principals and architectural practice”, he discussed the storerooms and other spaces that were necessary for the new Zacatecas alhóndiga, in consultation “with the workers and experienced individuals of the country” (con los operarios y personas experimentadas del país). As a result, he estimated the cost of a new granary to be 60,000 pesos (AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 31, exp. 9, fols. 103r–103v). |

| 33 | In a carefully drafted drawing (37.3 × 53.7 cm) that evinces his academic training and where he identifies himself as “profesor de arquitectura” (professor of architecture), Crouset planned a building of 68 × 35 varas. It comprised two large storerooms of 24 varas each with independent access from the main façade, eight smaller rooms enclosing an interior patio on three sides, and other auxiliary spaces for the granary’s administrator. See “Alhóndiga de valle de Matehuala, S.L.P.” AGN, Mapas Planos e Ilustraciones. |

| 34 | He is one of the architects involved in repairing the fountains of Mexico City’s Plaza Mayor in the first decade of the nineteenth century, as well as assessing the damage caused by the 1800 earthquake to the city’s buildings and infrastructure. In 1804, contemporary to the designs of the alhóndiga, he was also drawing new plans for Querétaro’s alameda (AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 36, exp. 18, fols. 402–20; AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 6, exp. 16, fols. 290–336; AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 37, exp. 13, fols. 116–65). |

| 35 | Two of these drawings are of similar size: plan of the first floor (48 × 59.3 cm) and plan of the second floor (47.7 × 58 cm); while the third one (section of the building and elevation of the façade) is slightly smaller (48.4 × 52 cm). See AGN, Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones (280)/MAPILU/210100/2856Alhóndiga de Querétaro. Qro. (2698); Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones (280)/MAPILU/210100/2857Alhóndiga de Querétaro. Qro. (2699); and Mapas, Planos e Ilustraciones (280)/MAPILU/210100/2858Fachada de la Alhóndiga de Querétaro. Qro. (2700). |

| 36 | See Plan of a Monumental Staircase, completed by José María Casas in 1805, and the Section of the Caserta Palace, dated 1808 and authored by José María Echeandía. All these drawings, today preserved in Mexico City’s Archivo de la Antigua Academia de San Carlos, are reproduced in Fuentes Rojas 2002, pp. 131, 181, 234, 237–39. |

| 37 | Vitruvius recommended granaries to be set in an elevated position “with a northern or north-eastern exposure, so that the grain will not be able to heat quickly, but, being cooled by the wind, keeps a long time” (Vitruvius 1787, p. 154). These ideas were reiterated in the treatises of Renaissance and eighteenth-century architects. Alberti and Palladio recommended the same attention to the ventilation of the facilities and also advocated for the use of bricks in the paving of the trojes (storage rooms) to prevent moisture (Alberti 1581, pp. 144, 156; Palladio 1797, pp. 57–58). Building upon this architectural theory, Spanish mathematician and architect Benito Bails also urged the use of “the driest material that can be found” for the construction of granaries, particularly in the flooring, avoiding flagstones “because these, in the same way as any kind of stone, are easily soaked by moisture” (Bails 1783, p. 853). Along with a masonry foundation and walls, other elements of the architectural design introduced by Ciprés and Ortiz in their projected granaries of Guadalajara and Querétaro were aimed at implementing dryness. Enlarging the size of the trojes (storerooms), raising their flooring (one vara above the general floor for Querétaro’s alhóndiga), elevating their ceilings (up to nine varas in the granary of Guadalajara), and considering their exposure and orientation (allowing “the winds free for light and ventilation” in the words of Ciprés) were intended to facilitate airflow and protect the stored grain from humidity (AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 23, exp. 5, fol. 169r; Chávez Orozco 1956, pp. 42–43). |

| 38 | Editions in Spanish of both treatises by Vitruvius and Vignola were published in the eighteenth century and were used for educational purposes in the Mexican Academy: Marcos Vitruvio Polión, Los Diez Libros de Architectura (Madrid, 1787) and Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola, Reglas de los Cinco Órdenes de Arquitectura de Vignola (Madrid, 1792). These books also circulated in the provinces of New Spain and were owned and collected by the elite. See (Bernstein 1946; García Melero 2002, pp. 38–53; Chanfón Olmos 2004, pp. 179–84). |

| 39 | When describing the patio in their 1805 report, Ortiz and Pérez stressed this simplicity and clarity of lines in its design, only interrupted by the “small ornament” of stone drops laid in headers over the lintels. Of ancient origin, these forms occurred in Doric cornice (Archivo Histórico de la Universidad de Guanajuato (AHUG), Alhóndiga (2a), Caja 3, 1805-08, fols. 3v–11v). |

| 40 | The use of this Spanish cursive letter suggests a familiarity with eighteenth-century studies to reform handwriting, such as the work of Spanish calligrapher Francisco Javier de Santiago Palomares, who in 1776 published the treatise Arte nueva de escribir. Treatises on handwriting circulated in New Spain in the late eighteenth century. In addition, as art historian Kelly Donahue-Wallace has recently studied, the ideas of Palomares had a strong impact on the work of Jerónimo Antonio Gil, with whom he shared a professional relationship and interest in typeface design prior to the latter’s departure to Mexico City in 1778 and his later appointment as director general of the Royal Academy of San Carlos, where Ortiz and other architecture students trained (Donahue-Wallace 2017, pp. 107–13). |

| 41 | Mexican historian Lucas Alamán, native to Guanajuato, attributed this negative opinion to his father Juan Vicente Alamán and recalled the episode in the following terms: “My father, despite the friendship he had with the intendente [Riaño], disapproved of the construction of this building, considering it preferable that the funds invested in it, coming from a contribution of two reales in each load of maize that was introduced in Guanajuato, be spent [on] making the road that was later began on the hills to the north of the ravine, to avoid the transit through it, very dangerous in times of water, which was the object with which the contribution was imposed, and censuring sharply the too luxurious architecture and ornaments, he said that Mr. Riaño was building a palace for the maize.” |

| 42 | In 1786, local master mason Juan Rodríguez was first commissioned by the cabildo of Durango to elaborate a budget and two plans for the new construction intended to include, among others, the residence of the intendente, the city hall, the customhouse, and the tobacco factory. See AGN, Obras Públicas, vol 25, exp. 2. |

| 43 | Unfortunately, the whereabouts of the drawings are unknown. They were commissioned in 1800 by the intendente Bonavía, per order of Nemesio Salcedo, Comandante General (Commandant-General) of the Internal Provinces of New Spain, and Mexico City’s Junta Superior de Real Hacienda. Durango’s cabildo refused to pay Tolsa’s honorarium because it had not commissioned the plans and had limited funds. After the case was reviewed, the city was ordered to pay. Durango’s cabildo reluctantly obeyed and requested the drawings to be returned from Mexico City in order to be kept in the municipal archive, suspending payment until their arrival. By June 1804, the plans had not appeared, and therefore intendente Bonavía suggested that a new copy be made by Tolsá and be paid for by whoever was guilty of losing the first drawings. Comandante Salcedo ordered an inquiry into the offices that had reviewed them in Mexico City, but all of them denied possession. In late 1805, Tolsá, then director of the Mexican Academy, protested the unacceptable delay in payment. The plans, which included guidelines and the dimensions of the site, had been commissioned by the intendente more than six years earlier. Clearly, Tolsá did not travel to Durango for the design of the building. According to his own testimony, he completed two sets of drawings. The first followed the instructions received from Durango; the second was based on Tolsá’s own judgment, as he expressed it, considering it a better arrangement for the offices. This latter drawing, Tolsá stated, was enthusiastically received by the intendente in Durango “giving me thanks for the improvements noted in the last [version].” Tolsá argued that he had only charged 500 pesos when the just price would have been 800 pesos for a building that was intended to house the residence of the intendente, the city hall, a jail for men and women, quarters for royal officials, the royal assay establishment, the alhóndiga with the dwelling of its administrator, chapel, and other adjacent spaces. Tolsá concluded that he was not to blame for the loss of the plans he carefully elaborated and that even if he agreed to provide new copies as a courtesy of his service to the king and the public, he had neither the drafts he used nor the dimensions of the site. Therefore, he implored for his honorarium to be paid without further delay. Comandante Salcedo passed the order to the intendente Bonavía on the last day of 1805. We do not know if the plans ever appeared, but presumably the city of Durango paid, as no further exchange of documentation on this matter exists (AGN, Obras Públicas, vol. 16, exp. 1, fols. 1r–9v). |

References

Archival and Unpublished Sources

Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City (AGN)- Caminos y Calzadas, vol. 22, exp. 4, fols. 81–94.

- Alhóndigas, vol. 1, exp. 4, fols. 38–50.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 6, exp. 16, fols. 290–336.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 12, exp. 19, fols. 320–31.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 12, exp. 21, fols. 348r–374v.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 16, exp. 1, fols. 1r–9v.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 23, exp. 5, fols. 162–215.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 25, exp. 2.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 25, exp. 6, fols. 211r–234r.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 25, exp. 8, fols. 304r–317r.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 25, exp. 10, fols. 333r-359v.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 31, exp. 9, fols. 101–9.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 36, exp. 6, fols. 87–125.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 36, exp. 18, fols. 402–20.

- Obras Públicas, vol. 37, exp. 13, fols. 116–65.

- Indiferente Virreinal, Caja 3374, Expediente 042 Alhóndigas

- Mapas Planos e Ilustraciones (280)

Archivo General de Indias, Seville (AGI)- MP-MEXICO,153

- MP-MEXICO,456BIS

- MP-MEXICO,773

Archivo Histórico de la Universidad de Guanajuato, Guanajuato (AHUG)- Alhóndiga (2a), Caja 3, 1793–1809

- Alhóndiga (2a), Caja 3, 1805–08

Biblioteca Pública del Estado de Jalisco, Guadalajara (BPEJ).- Archivo de la Real Audiencia de Nueva Galicia, Bienes de Difuntos, caja 220, exp. 25

- Archivo de la Real Audiencia de Nueva Galicia, Bienes de Difuntos, caja 272, exp. 6

- Archivo de la Real Audiencia de Nueva Galicia, Ramo Civil, caja 202, exp. 25

- Archivo de la Real Audiencia de Nueva Galicia, Ramo Civil, caja 416, exp. 7

Sagrario Metropolitano, Guadalajara. Available at familysearch.org.- Registros parroquiales. Bautismos 1759–1765

- Registros parroquiales. Bautismos 1793–1799

- Registros parroquiales. Bautismos 1799–1806

- Registros parroquiales. Bautismos 1810–1815

- Registros parroquiales. Defunciones 1798–1829

Published Sources

- Alamán, Lucas. 1849. Historia de Méjico desde los Primeros Movimientos que Prepararon su Independencia en el año de 1808 hasta la época Presente. Mexico City: Imprenta de J. M. Lara. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, Leon Battista. 1581. Los Diez Libros de Architectura de Leon Baptista Alberto. Madrid: En casa de Alonso Gomez. [Google Scholar]

- Arenas Sánchez, José. 1969. Historia de la Alhóndiga de Granaditas. Guanajuato: Universidad de Guanajuato, Archivo Histórico. [Google Scholar]

- Arrom, Silvia Marina. 2001. Containing the Poor. The Mexico City Poor House, 1774–1871. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón Zester, Francisco. 1988. Paseo Filipense. Una Historia de la calle San Felipe. Guadalajara and Mexico City: Ayuntamiento de Guadalajara. [Google Scholar]

- Báez Macías, Eduardo. 1972. Guía del Archivo de la Antigua Academia de San Carlos, 1801–1843. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. [Google Scholar]

- Báez Macías, Eduardo. 1974. Fundación e historia de la Academia de San Carlos. Mexico City: Departamento del Distrito Federal. [Google Scholar]

- Bails, Benito. 1783. Elementos de Matemática. Tomo IX, Parte I. Que Trata de la Arquitectura Civil. Madrid: Por Don Joachin Ibarra. [Google Scholar]

- Barteet, C. Cody. 2019. Architectural Rhetoric and the Iconography of Authority in Colonial Mexico. The Casa de Montejo. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, Harry. 1946. A Provincial Library in Colonial Mexico, 1802. Hispanic American Historical Review 26: 162–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bielfeld, Jacob Friedrich. 1767. Instituciones Política: Obra en que se trata de la Sociedad Civil, de las leyes, de la Policía, de la Real Hacienda, del Comercio, y fuerzas de un estado. Madrid: en la imprenta de Gabriel Ramírez. [Google Scholar]

- Boils Morales, Guillermo. 1994. Arquitectura y Sociedad en Querétaro (siglo XVIII). Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales; Archivo Histórico del Estado. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Thomas. 1976. La Academia de San Carlos de la Nueva España. Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Juan Luis. 2021. Architecture and Urbanism in Viceregal Mexico: Puebla de los Ángeles, Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo, Thomas. 2010. Ciencia, cultura y política ilustradas (Nueva España y otras partes). In Las reformas borbónicas, 1750–1808. Edited by Clara García Ayluardo. Mexico City: CIDE, FCE, Conaculta, INEHRM, Fundación Cultural de la Ciudad de México, pp. 83–130. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Becerra, Arturo. 1997. Álbum del Tiempo Perdido. Pintura Jalisciense del siglo XIX. Guadalajara: El Colegio de Jalisco. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Cárdenas, Enrique. 2012. El proceso constructivo del Sagrario Metropolitano de Guadalajara: la llegada de José Gutiérrez y el inicio de la arquitectura neoclásica en la ciudad. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 34: 81–108. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-12762012000200004#nota (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Candiani, Vera. 2014. Dreaming of Dry Land. Environmental Transformation in Colonial Mexico City. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, Carmen. 2002. Los intendentes en el gobierno de Guadalajara, 1790–1809. Anuario de Estudios Americanos 59: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, Carmen. 2005. Huellas de impresores, imprentas y autores alemanes en la Nueva España: el caso de la imitación de Cristo. In Alemania y México. Percepciones mutuas en impresos, siglos XVI–XVIII. Edited by Horst Pietschmann, Manuel Ramos Medina and Marí Cristina Torales Pacheco. Mexico City: Universidad Iberoamericana, pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chanfón Olmos, Carlos, ed. 2004. Historia de la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo Mexicanos. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; Fondo de Cultura Económica, vol. II, tome III. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez Orozco, Luis, ed. 1956. Documentos sobre la Alhóndiga de Guadalajara. Mexico City: Almacenes Nacionales de Depósito. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero Herrera, Alicia Leonor. 2013. Felipe Cleere, oficial real, Intendente y Arquitecto, entre la Ilustración y el Despotismo. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico. Available online: https://ru.dgb.unam.mx/handle/DGB_UNAM/TES01000703958 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Cornejo Franco, José, Francisco Ayón Zester, and Lucía Arévalo Vargas. 1985. Obras Completas, tomo II. Guadalajara: Gobierno del Estado de Jalisco. [Google Scholar]

- Diario de México: Dedicado al Exmô. Señor Don Jose de Yturrigaray, Caballero Profeso del Orden de Santiago...: Tomo V. 1807. Mexico City: en la imprenta de la calle de Santo Domingo.

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. 2017. Jerónimo Antonio Gil and the Idea of the Spanish Enlightenment. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Martha. 1986. El albañil, el arquitecto y el alarife en la Nueva España. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 14: 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Florescano, Enrique. 1969. Precios del maíz y crisis agrícolas en México (1708–1810). Mexico City: El Colegio de México. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes Rojas, Elizabeth. 2002. La Academia de San Carlos y los Constructores del Neoclásico. Primer Catálogo de Dibujo Arquitectónico, 1779–1843. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez Ruiz, María Ángeles. 1993. La Consolidación de la Conciencia Regional en Guadalajara: El Gobierno del Intendente Jacobo Ugarte y Loyola, (1791–1798). Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/handle/10481/14312 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- García, Virginia. 1987. El almacenamiento de granos a gran escala para abastecer a la capital virreinal. In Almacenamiento de Productos Agropecuarios en México. Edited by Gail Mummert. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, Almacenes Nacionales de Depósito, S.A, pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- García Melero, José Enrique. 2002. Literatura Española sobre artes Plásticas. Volumen I: Bibliografía Aparecida en España entre los siglos XVI y XVIII. Madrid: Encuentro. [Google Scholar]

- Glasco, Sharon Bailey. 2010. Constructing Mexico City: Colonial Conflicts over Culture, Space, and Authority. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- González Franco, Glorinela, María del Carmen Olvera Calvo, and Ana Eugenia Reyes y Cabañas. 1994. Artistas y Artesanos a Través de Fuentes Documentales. Volumen I. Ciudad de México. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Gordo Peláez, Luis. 2010. Equipamientos y edificios municipales en la Corona de Castilla en el siglo XVI. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/10840/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gordo Peláez, Luis. 2013. ‘A Palace for the Maize’: The Granary of Granaditas in Guanajuato and Neoclassical Civic Architecture in Colonial Mexico. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne/Canadian Art Review 38: 71–89. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42630895 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Gutiérrez Lorenzo, María del Pilar. 2007. Educación, ilustración, e independencia en Guadalajara de Indias: la impronta del obispo navarro Juan Cruz Ruiz de Cabañas (1790–1824). In De ida y vuelta. América y España. Los Caminos de la Cultura. Edited by Pilar Cagiao Vila and Eduardo Rey Tristán. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Soubervielle, José Armando. 2013a. Un rostro de piedra para el poder. Las Nuevas Casas Reales de San Luis Potosí, 1767–1827. San Luis Potosí: El Colegio de San Luis. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Soubervielle, José Armando. 2013b. De piedra y maíz. Las Alhóndigas y el Abastecimiento de granos en San Luis Potosí Durante el Virreinato. San Luis Potosí: El Colegio de San Luis. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Andrade, Angélica Primavera. 2020. La Casa de la Misericordia. Una Solución a la Pobreza en Guadalajara. Guadalajara: Editorial Universidad de Guadalajara. [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, Luis Antonio. 1790. La Publica Felicidad. Objeto de los Buenos Príncipes. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Niell, Paul. 2015. Urban Space as Heritage in Late Colonial Cuba. Classicism and Dissonance on the Plaza de Armas of Havana, 1754–1828. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz Macedo, Luis. 2004. La Historia del Arquitecto Mexicano. Siglos XVI–XX. Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Proyección de México. [Google Scholar]

- Palladio, Andrea. 1797. Los Quatro Libros de Arquitectura de Andres Paladio, Vicentino. Traducidos e Ilustrados con notas por Don Joseph Francisco Ortiz y Sanz. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, Gabriel. 2008. Enlightenment, Governance, and Reform in Spain and Its Empire, 1759–1808. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Pietschmann, Horst. 1996. Las Reformas Borbónicas y el Sistema de Intendencias en Nueva España. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Montes, Mina. 2010. José Mariano Oriñuela y su proyecto para el establecimiento de una Academia de Matemáticas en Querétaro. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 97: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Real Ordenanza para el Establecimiento e Instrucción de Intendentes de exercito y Provincia en el Reino de la Nueva-España. 1786. Madrid: Viuda de Joaquín Ibarra, Hijos y Compañía.

- Recopilación de leyes de los reinos de las Indias: Mandadas Imprimir y publicar por la Majestad Católica del rey Don Carlos II, nuestro señor. 1681. Madrid: Julián de Paredes.

- Rees Jones, Ricardo. 1979. El Despotismo Ilustrado y los Intendentes de la Nueva España. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Razura, Adriana. 2008. José Gutiérrez, El arquitecto malagueño del neoclásico en Guadalajara, México (1766–1835). Cuadernos de Estudios del siglo XVIII 18: 181–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreffler, Michael. 2007. The Art of Allegiance: Visual Culture and Imperial Power in Baroque New Spain. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz, Mardith, ed. 1987. Architectural Practice in Mexico City: A Manuel for Journeyman Architects of the Eighteenth Century. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suplemento a la Gazeta de México del martes 22 de agosto de 1786. 1786, In Gazeta de México: Compendio de Noticias de Nueva España. México: por D. Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, Calle del Espíritu Santo, [1784–1809], pp. 185–92.

- Terán, Marta. 2017a. El Testimonio del Consulado de Guadalajara de 1802 referente al puente de Calderón. Historiografía ¿sobre sus arcos? Historias 89: 55–78. Available online: https://www.revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/historias/article/view/11033 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Terán, Marta. 2017b. Testimonio del expediente instruido a efecto de indagar y saber la necesidad que hay, y utilidad que debe resultar de edificar los puentes de La Laxa y Calderón. Historias 89: 117–36. Available online: https://www.revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/historias/article/view/11037 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Toussaint, Manuel. 1948. La Catedral de México y el Sagrario Metropolitano: Su Historia, Su Tesoro, Su Arte. Mexico City: Comisión Diocesana de Orden y Decoro. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar Esquivel, Enrique, and Adriana Garza Luna. 2006. Juan Bautista Crouset, Maestro mayor de obras de Monterey. Boletín de Monumentos Históricos 8: 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Van Young, Eric. 2006. Hacienda and Market in Eighteenth-Century Mexico: The Rural Economy of the Guadalajara Region, 1675–1820, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Chávez, Jaime Alberto. 2013. Arquitectura para la Administración Pública: Casas Reales Novohispanas siglo XVIII. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán. [Google Scholar]

- Viqueira Albán, Juan Pedro. 1999. Propriety and Permissiveness in Bourbon Mexico. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Vitruvius, Marcus. 1787. Los diez libros de architectura de M. Vitruvio Polion. Traducidos del latin y comentados por Don Joseph Ortiz y Sanz. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Catherine. 1975. The Escorial and the Invention of the Imperial Staircase. The Art Bulletin 57: 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gordo Peláez, L. Grain Architecture in Bourbon New Spain: On the Design of Guadalajara and Querétaro’s Alhóndigas. Arts 2022, 11, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020042

Gordo Peláez L. Grain Architecture in Bourbon New Spain: On the Design of Guadalajara and Querétaro’s Alhóndigas. Arts. 2022; 11(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGordo Peláez, Luis. 2022. "Grain Architecture in Bourbon New Spain: On the Design of Guadalajara and Querétaro’s Alhóndigas" Arts 11, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020042

APA StyleGordo Peláez, L. (2022). Grain Architecture in Bourbon New Spain: On the Design of Guadalajara and Querétaro’s Alhóndigas. Arts, 11(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts11020042