2. Relation of Dance and Religion: Classification of Dance Types

The manner in which dancing bodies in images in the church are represented is directly conditioned by the philosophical and moral attitudes of the church. The Eastern Orthodox Church

1, had rigid, but at the same time very complex, attitudes towards dance in the Middle Ages. Although dance was not a common theme, the most relevant sources for understanding its position are the manuscripts of theologians

2, especially Saint John Chrysostom (347–407), (

Saint John Chrysostom 2010); Saint Basil the Great (330–379) (

Saint Basil the Great 2010). Although these texts were written earlier, they are still relevant to the Middle Ages and later. Saint John Chrysostom initiated the question of the genesis, use, and meaning of dance and gives its interpretation. In Homily XLVIII.3 from

Homilies on the Gospel of St. Matthew, he wrote one of his most quoted sentences: “Wherever there is dance, there is the devil” (

Saint John Chrysostom 2010, p. 43). This Homily is dedicated to King Herod and Salome’s dance, the cause of John the Baptist’s death. However, at no point does the author identify a specific problematic dance, but rather makes a general remark. He continued that dancing was an unnatural and unnecessary practice: “God did not give us legs to rage, but to walk; not to jump because of that …, but on the account of that to celebrate with the Angels. If the body becomes ugly, it loses its shape before such immorality, does the soul suffer even much worse then? This is the way demons dance, this is the way servants of the demons deceive” (

Saint John Chrysostom 2010, p. 43). Perhaps the most consistent in terms of period and context are the writings of the theologian Gregory Palamas (1296–1359). He connected dancing with demonic powers, condemning bodies that incite passion.

Owing to our love to flesh, we love and seek worldly pleasures, falling into various forms of carnal passions. Since worldly enjoyment is realized through the senses and they are all different, so are the pleasures associated with them rather unlike. He enslaves (the tempters, the sinners—author’s remark) through the senses of (evil) hearing, sight, smells, making them lovers of impurity, obscene words, lewd songs, satanic dances”.

“The theological reflection of the late Middle Ages tends to avoid too general a form of condemnation, although recommendations inviting the faithful not to dance at all were not uncommon” (

Arcangeli 1992, p. 32). The treatment of dance in this period is ambivalent and remarkably complex. In Macedonian Medieval Churches, different examples of the representation of dance can be found. The reasons for this lie in the diversity of dance, its different types. Saint Gregory the Theologian (329–390) is one of the few to distinguish the various forms of dance, which shows the complexity of the issue. “When you want solemn events and celebrations, when you need to dance, then dance, yet not with the shameless dance of Herod, which was the cause of the death of the Baptist, but rather with the dance of David …” (

Saint Gregory the Theologian 2004, p. 82). This sheds a new light on the perception and position of dance as a bodily practice, allowing a counterpoint to the nihilistic, negative point of view to be created. Saloma’s provocative, immoral dances, as opposed to David’s awe-inspiring dances dedicated to God, are a thematic distinction that makes the main difference in representation of the dance motifs. This division also exists in relation to labeling the dances. Differences in dance treatment underline the author Arcangeli: “On one in this world is blamed: on the other hand, dancing dance in a ideal is classified hand, itself, different, context, among the manifestations of and as a one indeed: saints will joy, special not be without it entirely happy” (

Arcangeli 1992, p. 40).

Scholars who have dealt with terminological or linguistic analysis of church texts give the key to the different comprehension and meaning that dance had. By comparing the original sources, the scholars emphasize the difference between some Greek terms that we translate today under the sole term of dance (

Konovalov 2007;

Morozova 2013;

Akindinova and Amashukely 2015). The author Dimitriy Konovalov elaborates the use of the term dance and its etymological separators, which denote a completely different type of dance with relation to form, composition, dynamics, and bodily expression. He points out the difference between the words χορεία and ὂρχήσις from Bible texts written in Greek. “The locomotor movement that is the basis of the holy chorea is above all in a harmonious and dignified walk against the jumping of the existing dances (ὂρχήσις)” (

Konovalov 2007, p. 717). Reflecting on the use and interpretation of these various terms, he writes: “According to the interpretation of the ecclesiastical dignitaries, they considered the heavenly chorea combined with the words of praise to be the ideal form of pure religious delight. They approved of its imitation by Christians living on earth” (

Konovalov 2007, p. 714). Chorea is a noble, calm, restrained dance, more procession and walk-like than the definition of dancing today. Nicoletta Isar writes about close term

choros and points to its main characteristics. “Xορόε referred to collective coordinated movement in orderly, circular disposition; it can define the place where one dances; the choir; a round dance; the group of personages; the song performed by choir; the sence of order” (

Isar 2003, p. 183). On the opposite side, there exists a form called ὂρχήσις, it is a dynamic leap dance and corresponds to the descriptions of Middle Ages social dances

3, especially related to the lower social classes. The character, the manner of performance, and the effect it caused give a negative attribution. “Almost all of our sources, from medieval teachings to folk proverbs and sayings, associate every kind of ‘jumping’ with chaos, paganism, inciting the dark forces of the unconscious” (

Morozova 2013, online). Undoubtedly, theologians distinguished between these two types of dance by proclaiming that the restrained form of a moving procession, in their view, reflected the piety towards God, the obedience, and the morality of the participants. This was in contrast to the energetic, dynamic, free, wild, and according to the norms of that time, immoral dance, which was part of the extra-church practices and events that included social gatherings, celebrations, new ritual actions such as

dansemania4, as well as the first and most basic forms of stage performances represented through traveling forms of theater. Referring to a text by Saint Gregory the Theologian, Vladislav Darkevich comments on this dance duality: “Unlike the noble dances for King David, the wild ecstatic impulse in Saloma’s dance was emphasized in many ways” (

Darkevich 1984, p. 16). This ambiguous construct is the matrix for analysis not only of the Macedonian Orthodox, but in general for the moving representations present in religious imagery and the illustrations in religious texts and records.

Dance motifs in the Macedonian frescoes form two disparate groups. They are thematically conditioned and terminologically diversified. The Macedonian scholar Cvetan Grozdanov, in one of his rare texts dealing with dance, writes that there are “Two dominant models of representation of dance, song, instruments and dancers. The first model is related to the illustration of the Psalms of David and the figure of Miriam, the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, and the seven Israeli girls—dancers. The second model is related to the mockery of Christ...” (

Grozdanov 2008, p. 30). The first group is comprised of artifacts whose theme is linked to the dance χορεία which served to express respect and obedience to God, his worship and glorification. The second is related to the group of dances which in the Macedonian examples include a specific profile of performers. Their dances are characterized by dynamic movements, virtuous elements and acrobatics. Both groups, despite the differences, provide important information about the performance characteristics. The review and discussion of the frescoes will be presented in chronological order.

3. Praising the Lord

One of the initial tasks for the current research was to identify frescoes with dance motifs, from which the most important ones were singled out. Examining this ‘unrefined’ group with a much larger number of frescoes and icons belonging to the cycle in which the worship of the Lord is depicted, the presence of the same theme is constantly noticed. The dance motifs are, without exception, associated with the Psalms of David (148–150). This group will be presented through selection of two frescos from St. Archangel Michael, Lesnovo Monastery and St. George in the Polog Monastery and an icon from Church St. Archangels, Kuchevishte.

Several art historians have discussed the uniqueness of the depicted psalms in the Church of St. Archangel Michael, Lesnovo Monastery

5 (

Popovska Korobar 2000;

Gabelić 1998;

Radojčić 1940). The psalms are painted in the second zone of the eastern wall of the narthex. The scene from

Psalm (149.3), which reads “Let them praise his name in the dance: let them sing praises unto him with the timbrel and harp”, is presented with a mural of nine boys dancing in a chain folk dance representation (

Figure 1). The dance is closed in its form and the orientation of the performers is inwards. At the top of the composition is King David with a crown on his head holding a psalterion; next to him is the prophetess Miriam with a drum in her hands.

The lower half of the icon shows the performers facing away from the viewer, which reflects the natural body posture in this type of performance. The position of the arms is unique, in that they are intertwined. The dancer holds hands not with the next dancer on their side, but with the second, creating a connection of odd numbered or even numbered dancers. It is impossible to determine the direction of movement due to the differing orientation of the body and the steps made. Some seem to move toward the right and others to the left. The exception is the dancer dressed in blue, second from the left in the top row, who firmly stands with weight distributed on both legs and suggesting no movement. The dancers form two halves of the chain dance by facing each other. The way the dance bodies are shown is extremely striking as muscle contraction is observed. This indicates an anatomical representation of the dancers, a genuine posture that is found in dance performances. This is especially visible in the drawing of the contours of the legs, most accurately painted in the first dancer, dressed in white, and the fourth, dressed in blue, in the lower row. The fresco is well preserved and is perhaps one of the most beautiful Macedonian frescoes, as far as this motif is concerned.

There is a different type of dance composition located in the Church of St. George, The Polog monastery

6. Jesus Christ is represented in the vault of the narthex, alongside Psalms 148–150 illustrated in this section (

Figure 2). As a fragment to this composition an image of a folk dance is included. It is a female dance composed of eleven figures. On the right of the group, there is a picture of a musician, who author Dimitar Kjornakov describes as “a young child drummer” (

Kjornakov 2006, p. 135). The figures are positioned face-to-face, an orientation that is extremely popular in the stage performing arts, and form a closed circle. Nevertheless, this structuring is not typical for chain dance performances because the performers are most often facing the center or semi-profile in relation to the circular shape. This chain dance is practically impossible to perform the way it is painted. The option of frontal positions is present in the codified dance art forms where this type of dance enables direct communication between the performer and the audience. This quality has been maintained in the abovementioned fresco.

The painting composition demonstrates a variety of handholding techniques, all present in the chain dance forms, but never combined as in the fresco. The most frequent and widespread way in dance practice of holding hands is painted. However, in addition, the artist depicts an arm-in-arm technique as seen in the second dancer from the lower row and first in the upper row on the left. Macedonian ethnochoreologist Gancho Paytondjiev wrote that this position is ‘very rarely’ found in Macedonian dance practice, yet it still exists (

Paytondjiev 1973). In the Polog chain dance, we record other ways for the dancers to connect, such as holding the forearm and shoulder. The ethnochoreologist Mihailo Dimoski writes that these occur in Macedonian traditional dances; however, they are characteristic of male dances (

Dimoski 1977, p. 12). The fresco gives a rich authentic material about the methods used for connection that existed in the Macedonian traditional dances in general.

The orientation of the head and the body of the figures speaks of an unusual situation. The dancers are turned to face each other two-by-two as if building a dialogue relationship, which is unusual for folk dancing. Analyzing the distribution of the body weight, the standing axis, shows static, very stable posture in almost all the dancers. The exception is the first figure on the left in the lower row. The drapery of the dresses can give us grounds for a possible assumption that the movement would be toward the right side (characteristic of the Macedonian chain dances). Contrary to the strongly emphasized movement of the Psalm 149.3 fresco from Lesnovo Monastery, here we find a predominately static dance body posture. This is an example of the performance of the serene, graceful, female dance style typical for Macedonian female dances, but in the same time close to description of χορεία.

The only icon included in this analysis from the Church of St. Archangels, Kuchevishki Monastery

7 is

Praise the Lord (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). In an article written in the early 1940s, Svetozar Radojčić notes that “among the most interesting icons of our late painting is the large icon ‘Praise the Lord’ from the Church of St. Archangels in Kuchevishte” (

Radojčić 1940, p. 109). This excerpt indicates the interest taken in the icon since the period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941). In 1940, it was transferred from the church to the Church Museum in Skopje, and today is part of the collection of the Museum of Macedonia.

There is an uncertainty regarding the year the painting was created; the two years proposed are 1591 (

Serafimova 2005) and 1631 (

Popovska Korobar 2004). It is painted on a wooden board with dimensions of 130 × 67 × 3 cm, divided into hierarchically arranged zones: upper sky zone and lower ground zones. Jesus Christ dominates in the upper zone. The theme is the same with the above analyzed frescoes. In the lower right part, which illustrates Psalms 149–150, a dance of seven female dancers is painted, and inside the circle dance formation is a boy who is sticking a drum and a man with a string instrument. Due to the composition itself and the dimension of the painted figures, it is difficult to determine exactly which instrument, but it is most likely a stringed instrument. The gazes of musicians are focused on the grandiose figure of Christ. The dance itself may visually give the impression that these are two separate lines; however, judging by the position of the hands and the holding of the handkerchiefs, the performers dance in a closed circle. In further support of this argument is the raised hand of the dancer wearing a headscarf, located on the right. The handkerchief held in her left hand is raised, and although not quite visible, it is related to the dancer from upper zone. The dancers in the left half of the dance are also connected, forming a closed circular line. The circle formation is a constant in all the presented examples. Except for the middle dancer in the first row, where movement can be notified by the folds of the dress, the other figures show an almost completely calm posture of the body that does not give the impression of movement or initiation for movement. It is also impossible to assume the plausible direction of movement due to the different angles of the head and the body. There is no visible weight transfer. The sole moving ‘tension’ or activity is seen in the upper part of the body, in the positions of the arms. The hands in the dance have different positions; some of the dancers have their forearm raised, and others have it completely lowered or we see a combined positioning. They do not have direct physical contact, but the connection in the dance is achieved by holding a handkerchief. This kind of connection between dancers is not recorded today in Macedonian chain dances, and perhaps the first thought is that it was the imagination or creativity of the painter. However, the first ethnochoreological records made by the Janković sisters (Ljubica and Danica) in the 1930s note that this way of dancing is typical for the villages of Skopska Crna Gora, where the village of Kuchevishte is located, and for the villages of Blatija. They mention that the handholding between the dancers was achieved using handkerchiefs, hand-made cloths

8 and so-called

kjosteci (bead necklaces) (

Janković 1989). The fresco presents the authentic positions of a dance that was once a long part of the dance tradition in Macedonia.

Through the analysis of the three examples, valuable information about the specifics of the dances in the researched chronotope is obtained. The cycle of worshiping God is characterized by the performance of a

chorea and the most authentic information is related to the manner of holding hands. Some performance postures that have completely been lost in the practice of Macedonian dance are sealed in these frescoes and icons. If we make an intersection of the dance positions, some facts about dance technique can be concluded. The oldest fresco,

Psalm 149.3 from Lesnovo Monastery, demonstrates the closest bodily contact, the dancers connecting with intertwined hands, with bodies that are closely positioned and touching. They danced with a wide dance step and visible muscular articulation present in the fresco. In contrast, the female dancers of the church of St. George in the Polog Monastery show a more distant physical contact and a diverse approach of holding hands in the dance, with an almost static bodily posture. The most recent icon,

Praise the Lord, reveals an absence of any physical contact. This is due to the different gender composition which conditions a different technique of performance. Dimoski, in the description of Macedonian dances, notes: “The male style differs with firm and elastic movements of the legs, frequent bounces, kneeling and turning, whereas the female with expressed elegance and grace distinctive of the patriarchal Macedonian woman.” (

Dimoski 1977, p. 16). The strict gender division of dance composition with male or female chain dances present in the paintings was respected in the dance practice of Macedonia until the middle of the 20th century, after which, mixed gender compositions were introduced. In contrast to this apparent distinction of performances and dance style, the examples related to the second cycle (discussed below) are not conditioned by gender composition.

4. Mocking Christ

This thematic corpus is of particular interest to researchers, as it provides a wealth of information on medieval performing practices that have been erased by time. Performers and church officials were in constant antagonism and conflict. Webb explores the relationship between performers and performance, and audience and church, in late antiquity and noted “real rivalries between the two”, referencing the theatre and church authorities. (

Webb 2008). There was complexity in the general reception of performances, contributing to the basis of the critical position held by religion in the Middle Ages. In the beginning, especially in Catholicism, the church service used elements of performance, which were nevertheless later rejected and banned (

Divinjo 1978;

Krasovskaya 1979;

Harwood 1984). “It is not surprising that religion, in addition to appropriation, frequently anathematizes artistic practices (which were not used in its direct service) because it feels a strong ‘competition’ to a very similar if not often the same ‘field’ in the ‘hunt for human souls’” (

Lukić 2013, p. 265). The need to impose, in this case, the ecclesiastical value, moral and ethical system was fiercely implemented. Bakhtin points out laughter as an instrument against strong antagonism, the struggle of various power centers and the ruthless existential conditions that subsisted in the Middle Ages (

Bakhtin 1978). Laughter and joy were channels through which the tension and pressure of everyday life were articulated. “Indeed, that exceptional bias seriousness of the official church ideology had led to an outside necessity; outside the official and canonized cult of ritual and act to legalize merriment, laughter and joke that were suppressed. Thus, along with the canonized forms of the medieval culture, parallel forms of a purely cheerful (funny) characters were built” (

Bakhtin 1978, p. 87). Laughter, entertainment and joke were connected with universal entertainers who travelled and offered their skills throughout Europe. In Slavic countries, these types of performers are called

skomorokhs—cкoмopoxи (Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Polish) and a slightly different term present only in Macedonia

skomrakhs—cкoмpaxи.

The skomrakhs present in Macedonia were “tireless entertainers who wandered for centuries and through the centuries from village to village, from town to town, dragging their entire theater on their backs: few modest costumes, with long sleeves; a few masks, usually in the shape of an animal’s head, a few simple (‘folk’) musical instruments, and sometimes a trained animal (usually a bear)” (

Lužina 2007, p. 19). Their performances caused admiration, joy and laughter. They presented and parodied the “dramatic view of mankind” (

Divinjo 1978, p. 87), as proclaimed by the church, which is why it is not uncommon for them to be severely criticized and banned. As an integral part of life outside churches, they sometimes became a tool in the struggle for secular power. The Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible was quite fond of them. He used the skomorokhs for his own political benefits (

Bahrushin 1977, p. 15). Traveling performers have been the crucial link in the development of the performing arts, in that respect, as well as the canonized stage dance form that appeared later.

Fresco painters in the cycle of the Passion of Christ often painted the Mocking of Christ on the road to suffering on the hill of Golgotha where he was crucified. As some of the Psalms were illustrated with dancing bodies, the theme of Mocking Christ is found in all the selected examples and related to the presence of performers. The church had an extremely negative attitude towards the actions of the skomrakhs, recognizing in them bearers of immoral, forbidden actions. However, we find these cheerful characters sealed on the walls of churches. One of the first frescoes to record the presence of skomorokhs is located in Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (11th century). On the Macedonian frescoes, several scholars also point out the presence of skomrakhs (

Pavlovski 2004;

Lužina 2007;

Grozdanov 2008;

Maneva 2018). These groups depicted with laughter, playfulness and joy stand directly opposite to the beliefs and views held by the church. On the frescoes, they are represented, as they are seen by the faithful church, as groups that ridicule and belittle, insulting without a shred of faith and compassion. Parts of their eclectic performance with relation to dance come closer to what church texts defined as ὂρχήσις.

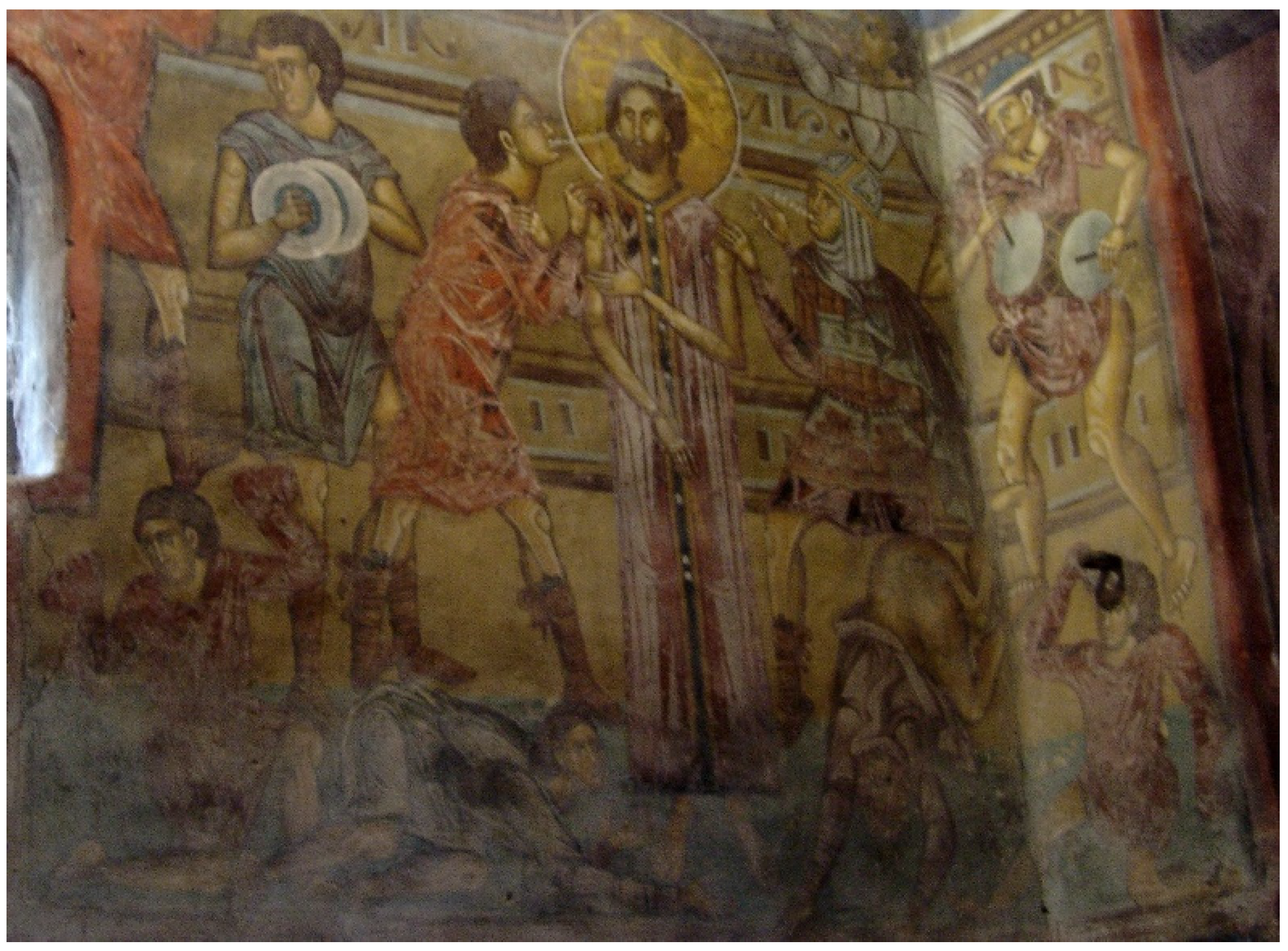

The first example to be discussed is the fresco

Mocking Christ located in the Church of St. George in the village of Staro Nagoricane

9, near Kumanovo (

Figure 5). The fresco’s mastery and beauty are emphasized by many researchers. “Such frescoes are found almost everywhere on the Balkans (from Bulgaria and Romania to Istria), but the Kumanovo one is undoubtedly the most beautiful” (

Lužina 2007, p. 20). The fresco was painted in 1317/18.

Jesus Christ is in the center of the composition. In the lower zone, there are different performers separated from each other. The self-standing or independence of the performers is one of the characteristics that differentiates it from the frescoes in the first group. Returning to the terminological differentiation of different types of dance, Konovalov writes that χορεία is a collective performance, in contrast to the individual forms of ὂρχήσις. “Even when they are a joint dance of a group of people, even then each dancer is usually independent from the others” (

Konovalov 2007, p. 718). Each of the painted skomrakhs performs a different moving element, playing their role independently and self-standing free of the others. This is largely conditioned by the improvisational character of the performance itself, where the performers are ‘feeling the pulse’, responding to the interests of the audience. There is no pre-determined synopsis in the performance, there is no synchronicity and equality of the dance itself. Analyzing the figures in the lower zone of the fresco we notice that they are in a kneeling position. The posture of the body, the lines of the legs, the muscle tension visibly indicate movement, dynamics and above all, the performing expression. The long sleeves that were part of the skomrakh’s

10 costumes were part of their performance. Kono Keiko reviews and comments on the depiction of the figures from Staro Nagoricane, and she pays great attention to the costume, specifically on the characteristic sleeves. The author draws a parallel with dance performances present in China and the Far East (

Keiko 2006). The protagonists in their ridicule bring tension and drama in the very atmosphere of the fresco through body language and tone of the movement. It is interesting that Keiko classifies the figures as dancers. It may be bold to claim that they are dancers. Historically, the traveling troupes performers possessed a variety of universal skills, including acting, singing, playing instruments, and juggling. Still the architecture of the body on the fresco confirms the existence of dance elements.

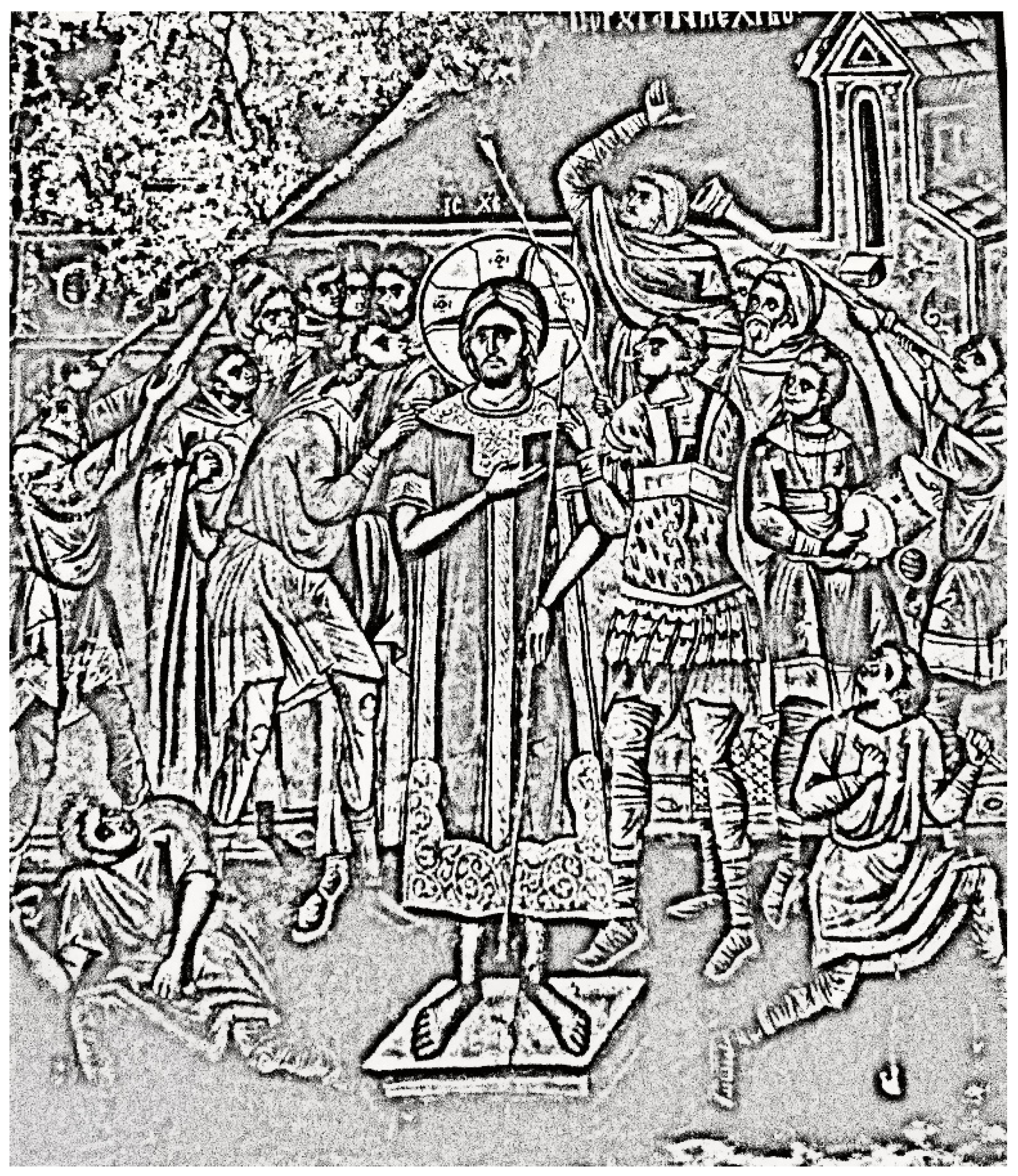

From the Church of St. George in the Polog Monastery, in addition to the fresco mentioned in the first part, we also single out the

Mocking of Christ. The fresco dates back to the middle of the XIV century (1343–1345) when the nave was painted. Although many researchers are obsessed with the fresco from Staro Nagoricane, this example from Polog offers a real wealth of information about the performing techniques and their application. Analyzing the culture and art of the Middle Ages,

Darkevich (

1984) cites several examples where acrobats, jugglers, and skomorokhs are part of the iconography depicting the passion and sin in Saloma’s dance for Herod. Jacques Le Goff makes an identical remark about the connection of virtuous performance, including dance with debauchery, the state that initiate dark forces “as well as jongleurs, who incited lascivious and obscene dances” (

Le Goff 1980, p. 60). Performers, dancers, jugglers, and actors carry that cheerful, fun side, sometimes too independently, overemphasized, out of control and repressive clichés of conduct that have become thematic material in the cycle of the Passion of the Christ.

The question of the discrepancy in the painting of the performing bodies of the skomrakhs, in relation to the representations processed in the first thematic topos, necessitates the inevitable comparison in this section. Although these are dance performances, there are great differences between the two groups, especially emphasized in the

Mocking of Christ from the church of St. George, Polog (

Figure 6). There is a rather large discrepancy in the way of representing the performing characteristics of the figures. Eugenio Barba distinguishes between the body in everyday life and the performing body. “In such cases, the acrobat shows us ‘another body’ which uses techniques so different from daily techniques that they seem to have no connection with them … Herein lies the essential difference which separates extra-daily techniques from those which merely transform the body into the ‘incredible’ body of the acrobat and the virtuoso so different from daily techniques” (

Barba 2005, p. 16). Barba mentions a technique and virtuosity that is characteristic of dance, but also many other hybrid types of performance. If we take, as an example, the male dance from the church in the Lesnovo Monastery where the quality of movement and muscular tension were emphasized, still there is not a single element that points to extra-daily techniques. The existence of a “colonized”

11 body of the frescoes in the second group is more than visible. The ability to accurately distribute the center of gravity or the ‘standing’ axis and to demonstrate stability in positions where there is an extremely disturbed balance speaks of training, exercise and performing technique. Added to this is the skill of dancing with long sleeves that only complement the effect of extra-daily techniques. “The skomorokhs who were well acquainted with folk dance, perfected the conduct of the performance and enriched the repertoire. They perfected the performances with acrobatic elements that required special preparation” (

Darkevich 1984, p. 5).

In addition to the typical kneeling positions, also detected in the other frescoes, we would emphasize two performers who stand out according to the body performing format. In the Biblical text, in the part where the soldiers mocked Christ, it is written “Again and again they struck him on the head with a staff and spit on him. Falling on their knees, they paid homage to him” (Mark 15:19). The worship before Christ seen in the Polog fresco is presented through several figures that parody the act itself. At the feet of Christ is the almost lying figure of a performer. The points of support are the feet and elbows, a particularly unstable angle that anticipates true articulation skills in all parts of the body. Of particular interest is the figure to the right of the wall composition

12. Of all the researched frescoes, including all the analyzed poses of performers, this figure most accurately depicts an acrobatic setting. The figure is painted with the back facing the viewer with the head facing down while the legs are lifted. The performer defies the laws of gravity by demonstrating virtuoso technique, standing or walking on his hands. It reveals naked body parts, showing the anatomy of a moving body. The drummer is also painted with his thighs revealed.

The number of performers is another peculiarity seen in this fresco, which we do not find in other examples with the same theme. Actors, acrobats, dancers and musicians are much more numerous than the soldiers who, according to the Bible, do the mocking. Emphasis is placed on ridicule through the performers. Contrary to the static and calmness of the figure of Jesus, all the others show visible movement and dynamics. This fresco provides rich material for reading the practices of the performers and their ‘art’.

In the church of St. Archangel Michael in Lesnovo, as well as dancers who glorified God, there is another outstanding example of performance. The painted

Mocking of Christ on the west side of the nave is presented in two scenes (

Figure 7). On one of them, we have the skomrakhs performers. The fresco shows a crowd of 15 figures densely scattered around Christ, composed of people, soldiers, musicians and scoundrels. According to their body posture, two figures that are in the lower zone stand out. This fresco, unlike the others, does not have the characteristic voluminous sleeves. The bodies of the performers are turned with their backs to Jesus, they step towards the periphery. Only their gaze remains fixed on him. The moving structure of the two bodies is different. The figure on the left has a wide stance, and the figure on the right is in an almost kneeling posture; positions that demonstrate visibly disturbed balance. This quality is connected with the presence of performing technique, it implies a performing, ‘colonized’ body. Researching the modalities of modern dance techniques, Laurence Louppe marks this quality and notes it as essential. “Dance space-time should be created through physical activity. To exist in dance, it cannot do without weight transfer, which is the only one capable of reshaping and even creating a figure or a place” (

Louppe 2009, p. 214).

Exploring the theatrical anthropology, several authors emphasize a state of so-called ‘disturbed’ balance or ‘luxury’ balance as one of the hallmarks of the ‘other body; that possesses extra-daily techniques (

Barba and Savarese 1991;

Ruffini 1998). “The changing equilibrium low can be interpreted as opposing the

force of gravity … it is a powerful extension of the ‘search’ for imbalance” (

Ruffini 1998, pp. 92–93). All depicted performers tend to show movements that are ‘risky’, different from the law of stability that is naturally inherent in humans

13. It is evident that there is a disturbance in the state of tranquility, essentially the balance. In these performers, we see a moving extension, in that they emphasize the quality of a dilated body, thus showing skill, ability and craft of performance. Despite the different dates of their creation and differences in compositional representation, the dominance in all examples is the way the bodies are displayed. They are dynamic, expressive, demonstrating competencies in the control and modelling of movement, presenting performance skills.

5. Conclusions

The iconography that was presented confirms the complex approach that religion had to dance, as well as to dance performances. The analysis of the frescoes and icons once again confirms the capacity of the body as a medium that carries different, sometimes completely opposing, meanings. An essential distinguishing factor in the dualist diametrically different treatment of dance prevails. The part in which dance is researched as a means of glorification, celebrating the Lord without exception, is associated with Psalms 148–150. All analyzed frescoes and icons present a group chain dance with a mono-gender composition. The choreography in all paintings shows a closed circle, unlike the open circular models present in the traditional dances of Macedonia today

14. In proxemics, the circle code represents perfection, since the most archaic civilizations to the present day. This form is found in the ritual dance performances of many cultures (

Sachs 1937;

Eliade 2005;

Stewart 2000;

Zdravkova Djeparoska 2011). “As far as the walking in the chorea itself is concerned, it does not imply a simple movement forward, but a compulsorily circular one. According to church fathers, the Angels and believers play chorea around the Creator” (

Konovalov 2007, p. 718). The movement according to the meager descriptions in church books, and also according to art representations, is almost static. The dancers from the fresco in the Lesnovo Monastery are the most dynamic, but they still do not show extreme positions, such as artificial ‘disturbed statics’ of the body. The direction of movement, which is crucial and which has coded meanings in the Macedonian dance culture, is almost impossible to determine on the frescoes, so this segment remains outside the analysis. The χορεία which signifies the triumph and joy of faith finds its reflection in the collective energy of the dance ensembles where we follow restraint, calmness, elegance and harmony. However, at the same time, these dancers bear valuable information about the Macedonian chain dances and style of dancing.

The second group of frescoes is the counterpoint to the first. Unlike the Psalms, the passages in the Bible describing The Passion of Christ do not directly mention a dance performance, whereas in the painting it is widely used. The represented body is one which the existence of performing techniques is evident, which connects it with the forms of medieval ‘theater’. Unlike the circular configuration, the figures in this group are independent and unconnected. The performers are disparate; each exists for themselves and attracts individual attention. In contrast to the strict observance of the gender composition of the first group, some researchers emphasize the mixed gender composition in the representations of the skomrakhs. Mishel Pavlovski, writing about the fresco from the church of St. George, Staro Nagoricane, points out that “The craft of the skomrakhs was not exclusive to men. The figure playing the wind instrument (shupelka) in the second row, according to the costume and according to the hat, is obviously a woman” (

Pavlovski 2004, p. 94). Writing about the Mocking at Staro Nagoricine, Keiko emphasizes a special moment “Mocking at Staro Nagoricino is highly dramatic: synthesizing the silence of Christ, the vigorously portrayed crowd, resounding musical instruments, gestures and costumes” (

Keiko 2006, p. 162). This quality of drama, elements of theatricality, tension that ‘hangs in the air’ only builds the effect peculiar of the second group. With the presence of musicians, performers/dancers, the way that their bodies are represented should initiate a certain emotional response. Musical instruments of the frescoes are different depending on the theme, with an exception of the drum (tapan) which appears in both groups.

In the Macedonian fresco depiction, there are unique examples of different formats of dances. The depicted dances make it achievable to read or decode information related to this specific chronotope, which has its own particular characteristics. They document and archive the medieval performing practices and dances, and are, perhaps, the only preserved sources available today.