1. Introduction

The Prussian residences of Western Pomerania, placed in romantic landscaped parks, had no chance of continuing their residential function after World War II, after Poland had taken control of the Western Territories. Most of these facilities were more or less completely destroyed and looted. After World War II, multi-apartment functions, elementary schools or orphanages were located in these historic buildings. Those functions are not currently able to be maintained, as they require both the conservation and renovation/re-adaptation of the buildings. Some facilities have been completely destroyed, and a process of further devastating degradation is still taking place before our very eyes. A discussion of the causes and effects of this infamous charter relating to the protection of monuments requires further separate study. Other researchers have also highlighted problems with the adaptation of rural noble and aristocratic residences in other regions of Poland (

Węcławowicz 2019;

Marcinów 2015).

Today, most of the historic residences in the Western Territories of Poland have lost their original function and need a new one to survive. The use of the resources of historic residential buildings in connection with the dynamic development of cultural tourism and other non-touristic forms of use of historic buildings, requires changes in the policy of heritage protection, and especially changes in the approach to and strengthening of market solutions. The necessity of finding an appropriate function for the functional and spatial distribution of a historic object has been expressed, amongst others, by Jadwiga Gancarz-Żebracka. Without introducing systemic solutions, many valuable historic resources will remain only troublesome and expensive souvenirs of the past (

Gancarz-Żebracka 2013). The most basic and obvious factor that allows a monument to survive is its continued use, preferably if this is a continuation of its original function.

In Poland, for many years, the revitalization and adaptation of manors, castles and palaces into other functions has been undertaken, both in theory and in conservation practice. The stock of residential historic buildings is extensive. KOBiDZ/NID data lists 320 castles, 2388 manors and 1786 palaces (a total of 4494). Kozak quotes different data relating to these resources, according to his own calculations (

Kozak 2008) (

Table 1). According to the author’s data, there are 340 castles, 2438 mansions and 1754 palaces (4532 in total). This difference results from the inclusion by KOBiDZ of objects registered as historic, the author’s omission of city palaces (which are not at the centre of landed estates) and differences in the assessment of the nature of a monument as a manor or a palace. In the area of Western Pomerania, there are also many historic residential buildings, which are often an expression of a centuries-old belonging to eminent noble and knightly families.

Palaces and manors are a means of measuring the historical development of particular regions in Poland. Certain development cycles can be traced back by studying these particularly intense periods of development of residential architecture in different regions. In the territories of Western Pomerania, after the boom during the Middle Ages and in Renaissance times, a later wave of economic recovery only appeared in the second half of the 19th century, and was an expression of the industrial boom in Germany, as well as a result of the policy of subsidizing large German landed property, under the Kulturkampf policy (

Kozak 2008).

Most of these buildings, although they survived the Second World War, were doomed to be destroyed or were adapted to functions inadequate to their value and status, after Poland took control over the Western Territories in 1945. The cause of this inglorious process of annihilation of many residential buildings, manors and palaces in the western territories was a post-war process, consisting of changes in nationality as well as political and social changes: the exodus and displacement of Germans, as well as the settlement within the community of people from eastern and central Poland, and changes in social structure (social homogenization, confiscation of property under the slogan of “socialization” and land nationalization, etc.). As a consequence, during the period of implementation of this policy by the socialist state, profound national, social and economic changes took place, which were intensified by the policy of erasing the German past. The lack of interest on the part of the State in financing the necessary and costly renovation and conservation works on valuable residential buildings in Western Pomerania led to a significant impoverishment of the rich stock of historic residential buildings. There is no need to hide the fact that this omission was a conscious policy of the Polish People’s Republic, aimed at erasing the so-called “Regained lands”, standing as testimonies to Prussian and German culture. Despite the treatment of these buildings being declared as on a par with other monuments in Poland, those historical monuments which were evidence of German and Prussian culture in the Western Territories did not receive the substantive financial support necessary for their maintenance that they deserved. The destruction of residential buildings in Western Pomerania went through several stages. Part of this resource was plundered by the Soviet army and burned down, or dismantled by post-war settlers for the construction and renovation of nearby houses. Amongst those palaces which suffered annihilation as a result of World War II were those in the vicinity of Szczecin, the Western Pomeranian capital: Bezrzecze, Zdroje, Płonia, the palace in Dobropol, the manor house in Dolsk, and the castle in Dobra Nowogardzka, (blown up for building materials), as well as many other rural residences, the only traces of which that are left today are manor parks (

Łuczak 2011).

Some of the facilities remained in good condition, and were hastily adapted into much-needed housing functions (multi-family) for agricultural workers on state-owned farms or into non-residential functions, such as offices, state farm management, schools, health centres and holiday centres for state-owned enterprises, etc. In the wave of socio-economic and political changes (decommunization, communalization and privatization) in the 1990s, part of this resource was transferred into private hands. Many residential properties remain in varying degrees of ruin to this day—mainly for financial reasons. The possibility of obtaining significant financial support for the necessary, but costly conservation and protection works has been difficult for many years. This is evidenced by, amongst other things, data on subsidies granted from 2007–13, included in the Report on the State of Preservation of Immovable Monuments in Poland.

The use of subsidies granted in 2007–2013 from the funds of the Rural Development programme for individual types of monuments, broken down by voivodship, shows a total of 9,316,743 PLN in subsidies for historic residential buildings, public utility buildings, castles and greenery which had been allocated in Poland during this period. A huge disproportion can be seen in the subsidies granted between the Lower Silesian Voivodeship, which had received the highest subsidies (of PLN 1,736,937 in total) and the West Pomeranian Voivodeship—which had received subsidies at the lowest level of 0.00 PLN(!) Another type of disproportion, in the same rural development programme, was the subsidy granted for sacred buildings, which in the Lower Silesian Voivodship amounted to 17,144,691 PLN, in Western Pomerania to 18,454,791 PLN, and in total in Poland to 203,806,841 PLN, i.e., twenty times more than for other, non-sacred monuments.

Those facilities for which new owners were found, who could bear the burden of their revitalization, adaptation and maintenance, were given a chance of survival. The historic residences in the area of Western Pomerania, which, thanks to conservation works and new functions, have retained their functionality, include, amongst others, the castles in Szczecin, Pęzino, Krąg, Stuchów, Trzebiatów, and Tuczno, a manor in Skarbimierzyce, and the palaces in Przelewice, Rybokarty, Ostoja, Trzygłów, Cieszyno, Brzóski, Koszewo and Koszewko (

Łuczak 2011, author’s own findings). However, many new owners have not been able to manage their renovation according to conservation guidelines or have neglected the upkeep of these buildings, which has led to their ruin. Perhaps part of the blame for many historic monuments being brought to a state of complete destruction can be laid on excessive conservation requirements, which have discouraged potential investors from investing in historic buildings. In the post-war period, a number of monuments of the Western Pomerania Region were brought to ruin, such as: the castle of the Knights Hospitaller in Swobnica, the half-timbered manor house in Świerzno, the neo-Gothic palaces in Kozia Góra, Wierzbiecin, Żelmów, Grzymiradz, the manors in Łozienica, Piaski Wielkie, Stolec and many others (

Pilch and Kowalski 2012). Maintaining a historic building in a usable condition, especially in remote locations and at a distance from important urban centres, requires the injection of large financial resources by the owners, and much effort and persistence in achieving this goal.

Today, the situation of residential buildings located in the Western Territories of Poland has changed significantly. The current policy of the state, a member of the European Union, has eliminated the imbalance in the treatment of monuments due to their historical cultural affiliation. Such a policy has created better possibilities for external financing to be obtained for the undertaking of reconstruction initiatives, revitalization, conservation and adaptation or for the re-adaptation of monuments in the Western Territories, including historic residential buildings. The issue of adapting historic buildings to new functions, corresponding to contemporary needs, is well-known, well-described and systematized (

Szmygin 2009). Nevertheless, each monument is different; they differ in their method of construction, technical condition, compositional and artistic value, location and surroundings, as well as in the historical importance and conservation requirements relating to each of these facilities.

Amongst those residential buildings that have survived in Western Pomerania, despite the unfavourable circumstances described above, should undoubtedly be included the palace in Maciejewo (

Figure 1). Before 1945, the name of today’s village of Maciejewo was “Matzdorf”. After a major readaptation in the 1970s and its renovation from the function of a hotel, the palace was transformed into a nursing home in 2020. The facility was not entered in the register of monuments until 2018, after renovation and adaptation changes, relating to the change of function of the facility, had been undertaken. The bibliography on the palace in Maciejewo is modest. Therefore, it seems appropriate to share some information about this building and its recent history.

2. Case Study of the Palace Residence in Maciejewo

2.1. Overall Characteristics of the Project

The scientific research presented in this article concerns a case study of one historic building, seen against the background of its historical development and the resulting changes in its use and equipment, as well as changes in the shape of the building and its surroundings. Before the start of the project, historical and in-situ studies were carried out on the facility, in order to re-analyze material values and historical messages, unknown when introducing adaptations after war damage. On the basis of these studies, an adaptive re-use project was developed and implemented. The example studied of the palace in Maciejewo presents a methodology of operation that can be imitated and developed in other similar cases. The following case study shows the fate of the property in Maciejewo, which has moved in a more positive direction during the latest phase of the building’s history. Unfortunately, this is quite a rare example of the preservation of the historic and functional values of a residential building integrated within park surroundings.

The example presented of the historic Palace in Maciejewo (in terms of the adaptive re-use of a historic building), shows the importance of selecting a function for a building that can maintain the historic value of the property and its surroundings, despite the new requirements for necessary adaptational changes to be introduced (

Figure 2). The presented project for the adaptive re-use of the palace to the fulfilment of a nursing home function is a solution that will provide the residents of the facility with comfort, as well as extraordinary architectural and landscape harmony, during the last years of their life. Additionally, the historic palace building will be preserved and taken care of. This is a solution that could also be successfully used with other facilities, having similar spatial and locational parameters. The quality of preservation of the interiors of the historic building, and the quality of the natural park surroundings, are advantages that most nursing homes lack.

2.2. The Genius Loci of Maciejewo

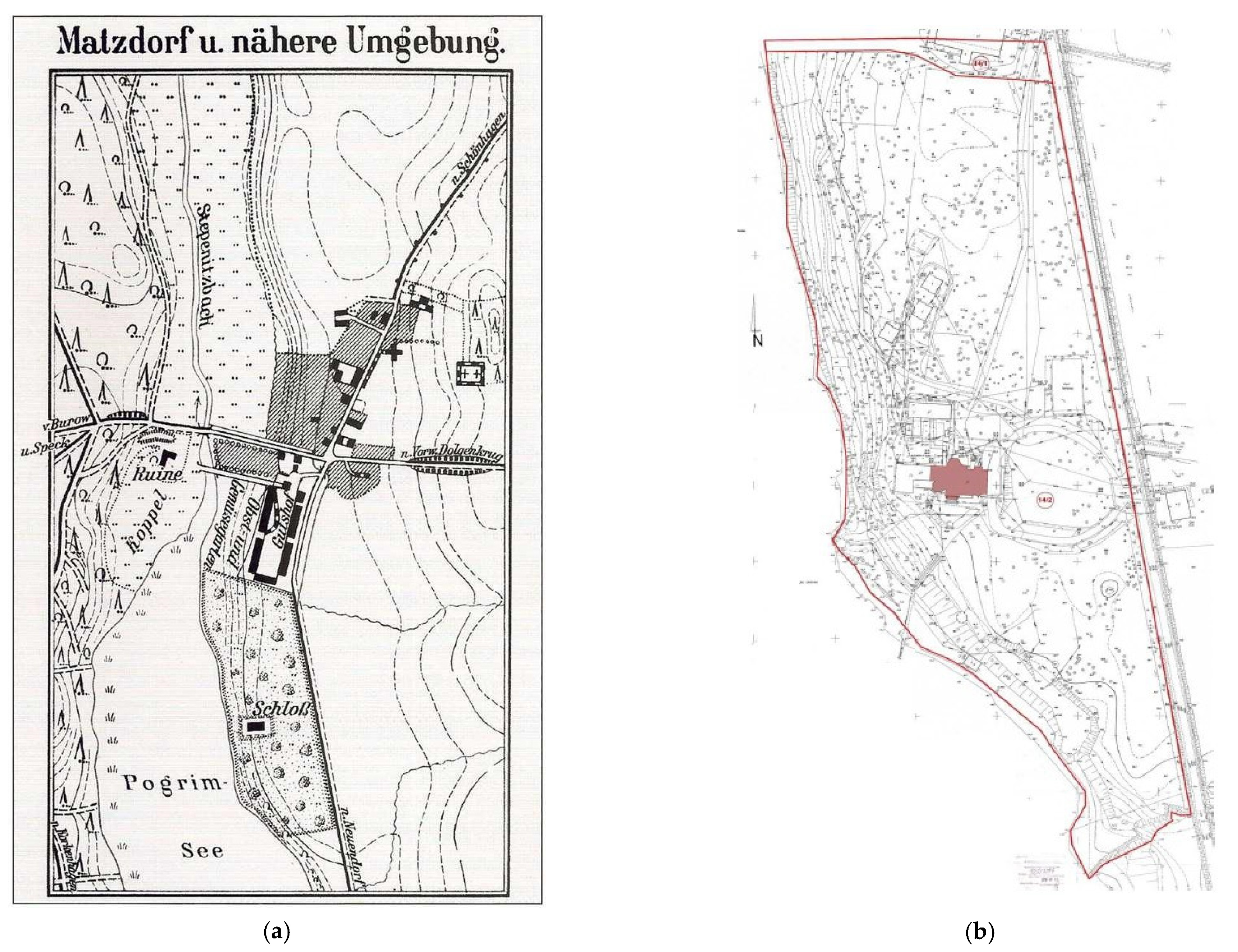

The palace in Maciejewo is located in the district of Maszewo, Goleniów county, on the edge of the Goleniów Forest, approx. 80 km from Szczecin. It is picturesquely situated on a slight hill above Lake Lechickie, from which the River Stepnica flows (

Figure 3a). The German name of ‘Lake Lechickie’ is ‘Pogrim See’. The palace building, designed in neo-Gothic style in the form of a castle with a tower, with an asymmetrical composition and an octagonal tower topped with a battlement, is integrated into the natural layout of the terrain topography, closing the longitudinal axis of Lake Lechickie from the north. The building is surrounded by a landscaped, English-style palace park, with an area of 76 ha 846 m

2, with a unique old forest, numerous examples of whose trees (including oaks, lindens, elms, beeches and others) have monumental dimensions, with a trunk circumference of 200–300 cm, whilst 30 trees have a trunk circumference of over 300 cm (

Haas-Nogal 2018).

The palace and park complex in Maciejewo was entered into the register of monuments, under number A-1794, only on 26 November 2018, before the last re-adaptation works on the building started (

Figure 3b). It had been listed in the Lexicon of Monuments of Architecture in Western Pomerania since 2012, although it was not formally a protected monument (

Gibczyński 2018a,

2018b). The uniqueness of the palace layout is characterized by a clear separation of the residential part, located in the central part of the palace park, from the economic part of the property—stables, cowsheds and barns as well as farm buildings, located on the north side, outside the park border.

2.3. History of the Maciejewo Estate

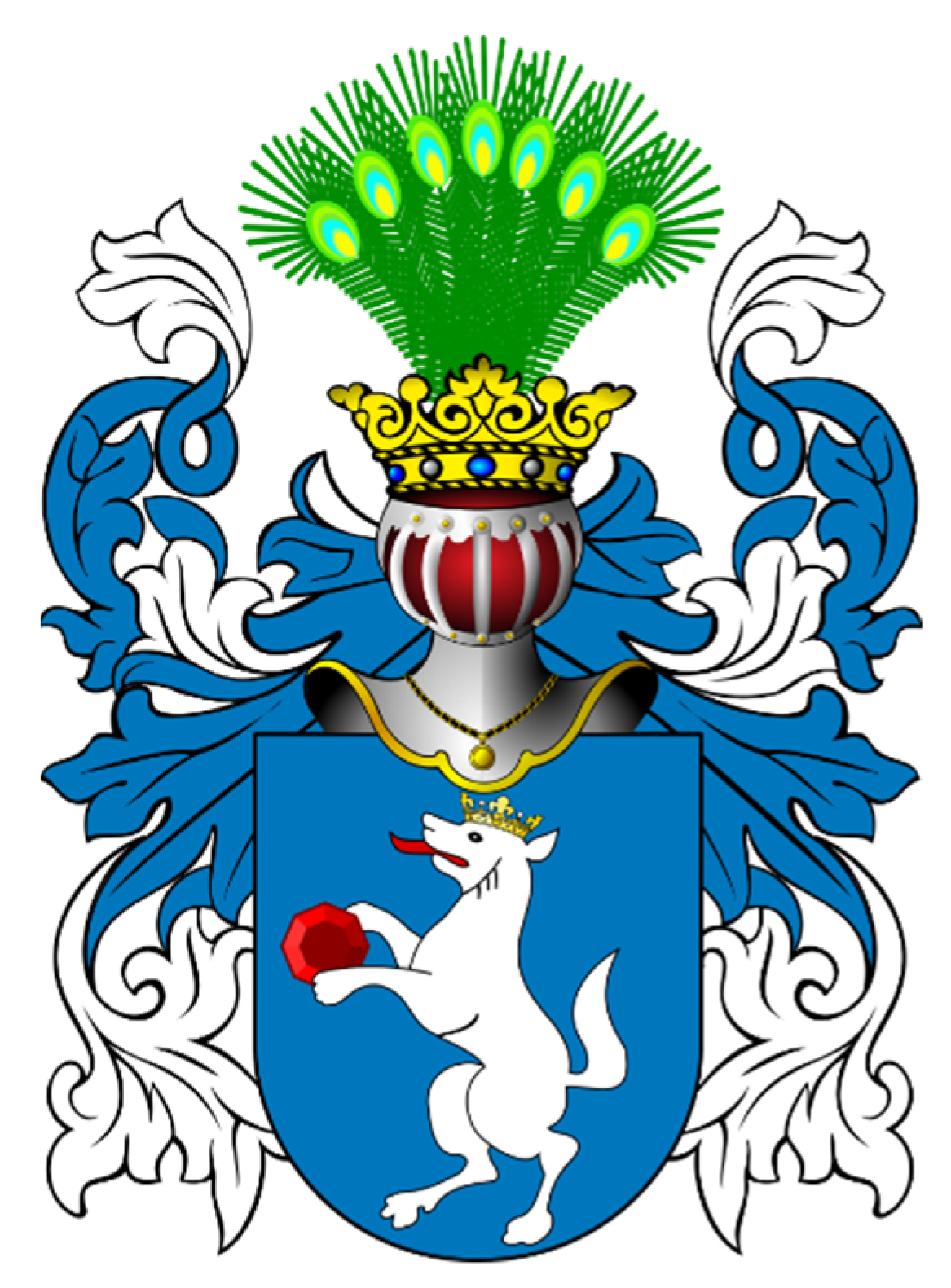

The estate of Maciejewo is historically connected with a family of Dutch settlers, the von Flemmings, in whose possession it remained until 1945 (

Figure 4). The earliest known owners of the Maciejewo estate were the von Visen and von Petersdorf families. They managed the land and the castle, which was located on the peninsula of Lake Lechickie from the north, in a different place than the later-erected and currently-existing palace. The fortified castle of the von Visen family was probably built in the 15th century and was then used until the middle of the 17th century by the von Petersdorf family. Later, it was abandoned and fell into disrepair (

Kalita-Skwirzyńska n.d.). There are relics of the stone walls of the castle; it is possible to identify these in the forest surrounding Lake Lechickie (

Radacki 1976). According to historical sources, the castle was in ruins as early as 1759. Next to the castle ruins, a half-timbered manor was erected, which was the first seat of the von Flemming family in this area. It was a spacious wooden mansion of half-timbered construction, known from the engraving from 1846, erected on the premises of the castle courtyard, which was still surrounded by embankments and a moat. The probable author of the construction of the first seat of the von Flemming family in this area was Eustachius von Flemming, who died in 1616. In 1835 there is a mention of the acquisition of the property, with 6674.83 morphs of land, by Franz Wilhelm Carl von Flemming, marshal and national envoy, residing in Bodzęcin (

Berghaus 1872). In 1892, the estate of 1673 ha was managed by Thamm Hasso von Flemming (

Brüggemann 1784). In 1869, a new manor house was built in the farm yard. The son of Thamm Hasso, Franz-Wilhelm Carl von Flemming, undertook the expansion of the village and the construction of a new farm complex. The founder of the new seat of the family (the present palace), was the son of Franz-Wilhelm Carl von Flemming, Paul Hasso Tam von Flemming, who inherited the property in 1896. The construction of the new palace residence was performed thanks to the Thamm Hasso von Flemming foundation, which undertook the implementation of this investment (

Kalita-Skwirzyńska n.d.). The palace was built in the years 1899–1900 on a sandy slope descending to the lake, south of the existing farm. Between the farm and the palace, a park with insulating greenery, composed of native trees, was established. Decorative flower beds and rare trees were planted south of the palace. In 1902, the developer of the entire establishment, Paul Hasso Thamm von Flemming, and his wife Viola Bonin from Dreżewo (Drewitz) lived in the palace. Their son, Erdmar Eduard Hasso, inherited the estate in 1934 and lived in the palace with his family until 1945 (

Walkiewicz 2014).

2.4. Following the Typological Prussian Pattern of a Residence in a Natural Landscape

The imperial summer residence was surrounded by a landscaped park, designed by Peter Joseph Lenne and Hermann von Pückler-Muskau. A characteristic feature of this establishment was its waterside location and the combination of the park landscape with the natural landscape of the Havel River valley and the surrounding hills (

Figure 5).

This allowed for distant views of the open landscape and water from the residential interiors. Another important feature of this establishment was the removal of all farm and residential buildings from the residential part, surrounded on all sides by a park, which, apart from its aesthetic and recreational functions, also had an insulating function (

Kalita-Skwirzyńska 2008). This characteristic feature of incorporating the natural open landscape into the composition of the landscape park and isolating the palace from other farm buildings is also clearly visible in the landscape layout of the palace residence in Maciejewo. Obtaining such a unique aesthetic effect was possible, thanks to the choice of the unique location of the palace within the natural landscape.

2.5. Adaptations and Reconstruction Works of the Palace in Maciejewo in the Period after 1945

The palace in Maciejewo survived World War II in good condition. During the period of the Polish People’s Republic, the palace building shared the fate of many similar Prussian residences in the western lands and was utilised for educational purposes. An agricultural school operated in the palace building until 1982. The next owner of the property was Przedsiębiorstwo Turystyczne Pomerania (Tourist Enterprise Pomerania), which has many tourist facilities in the region of Western Pomerania. The palace was then adapted to function as a hotel (

Figure 6). In 1998, amid a wave of re-privatization of state-owned enterprises, the palace in Maciejewo, along with the surrounding landscaped park, with an area of 76 ha 846 m

2, became private property.

At that time, a superficial renovation of the palace was carried out, including the repair of damaged window frames on aluminum windows and the introduction of an “atmospheric” interior design, not historically related to the building. However, the authentic decor of the banqueting hall and two tiled stoves in a richly-ornamental form were preserved. No fundamental changes were made to the structure of the facility, but only those changes necessary in relation to the facility’s ability to function as a hotel. In 2000, the hotel function was extended by the addition of a two-storey pavilion, connected to the main body of the palace. The author of the project for the expansion of the palace in Maciejewo was arch. Bogusław Pruchniewicz, along with his team (

Figure 7).

In the basement of the added pavilion, a recreational pool was built, with a view of the historic landscape park and Lake Lechickie. On the upper ground floor, level with the palace’s ground floor, there is a multi-functional room, mainly serving as a banquet, wedding and restaurant hall, with large glazing connecting the interior of the building to the beautiful greenery of the park’s old trees. The added pavilion was designed in contemporary form, characteristic of the architecture of the nineties, in a way that does not violate the integrity of the original body of the palace. The pavilion, thanks to the large amount of glazing, makes reference to the form of a “palace orangery” and is a shape that balances the asymmetric composition of the palace in the view from Lake Lechickie (

Figure 8). Unfortunately, during the renovation of the façade in 2000, the window frames were replaced with orange aluminum and the window bands and lintels were eliminated, which deprived the palace’s façades of stylish decorativeness.

The following items remain from the original elements of the palace that had been permanently connected to the preserved-body of the building: the wooden structure of the roof truss of the main body and the tower, the Klein-type ceramic-steel ceilings over the basements, the wooden beam ceilings with soffit and plaster on reeds above the ground floor and first floor, two wooden two-speed staircases with a baluster railing, (located on both sides of the corridor running along the main body of the building), a wooden spiral staircase in the tower, two columns with Corinthian capitals flanking the passage from the hall to the corridor on the ground floor and forming the basis of the arcade, the stucco decoration of walls and ceilings, along with the floral and geometric motifs in the rooms of the hall, the former garden lounge and the former dining room on the ground floor of the palace, a tiled fireplace with neo-Renaissance forms and a stove with richly-profiled ceramic tiles and a figurative relief (

Figure 9a,b).

In the vestibule, a floor made from terracotta tiles with a geometric pattern has been preserved; on the ground floor, internal, double-leaf door joinery, frames and panels within frames; and in the former ballroom, door carpentry decorated with neo-Gothic forms and with ogival glazing. In the entrance hall, a double-leaf door topped with a tripartite transom has survived. According to the guidelines of the Provincial Conservator of Monuments, protection should extend to the body of the building, the form of the roof, the composition of the facade, along with architectural details and the above-described elements of the structure and original equipment of the palace. These guidelines were fully observed in the re-adaptation and renovation works.

3. Results of the Adaptive Re-Use Project in Maciejewo

After over 20 years of the palace being used as a hotel, the building was ready for a major renovation, not only due to the usual wear and tear of the many elements of the building, but also to the increased requirements for hotel facilities and raised standards of finishing and equipment, as well as because of the nondegenerate wear and tear of many technical and functional solutions. As a result, the competitiveness of this facility had decreased compared to other new hotel developments that had appeared in the Western Pomeranian Voivodeship. The facility had also ceased to comply with current technical regulations, the bulk of which, with regard to facilities intended for the permanent residence of people, have been significantly tightened. It became necessary to make strategic decisions related to further ensuring that the palace could function effectively. The property found a new owner; a foundation that decided to change its function into a nursing home, a building intended for the permanent residence of the elderly. Properties with such a function, popular in Western European countries, are still rare in Poland and are very much sought after. Hence, the project to change the function of the palace in Maciejewo into a nursing home was encouraged by the Municipal Office in Maszewo, due to the possibility of it increasing the number of new jobs, and this aim was included in its design and implementation. Design work on the adaptive re-use of the palace facility was entrusted to the design office Urbicon Ltd. from Szczecin. The facility has undergone a process of adaptive re-use—from the function of a dilapidated hotel to the function of a nursing home, with a higher standard (DPS). It has been adapted to the requirements of construction, sanitary and conservation regulations.

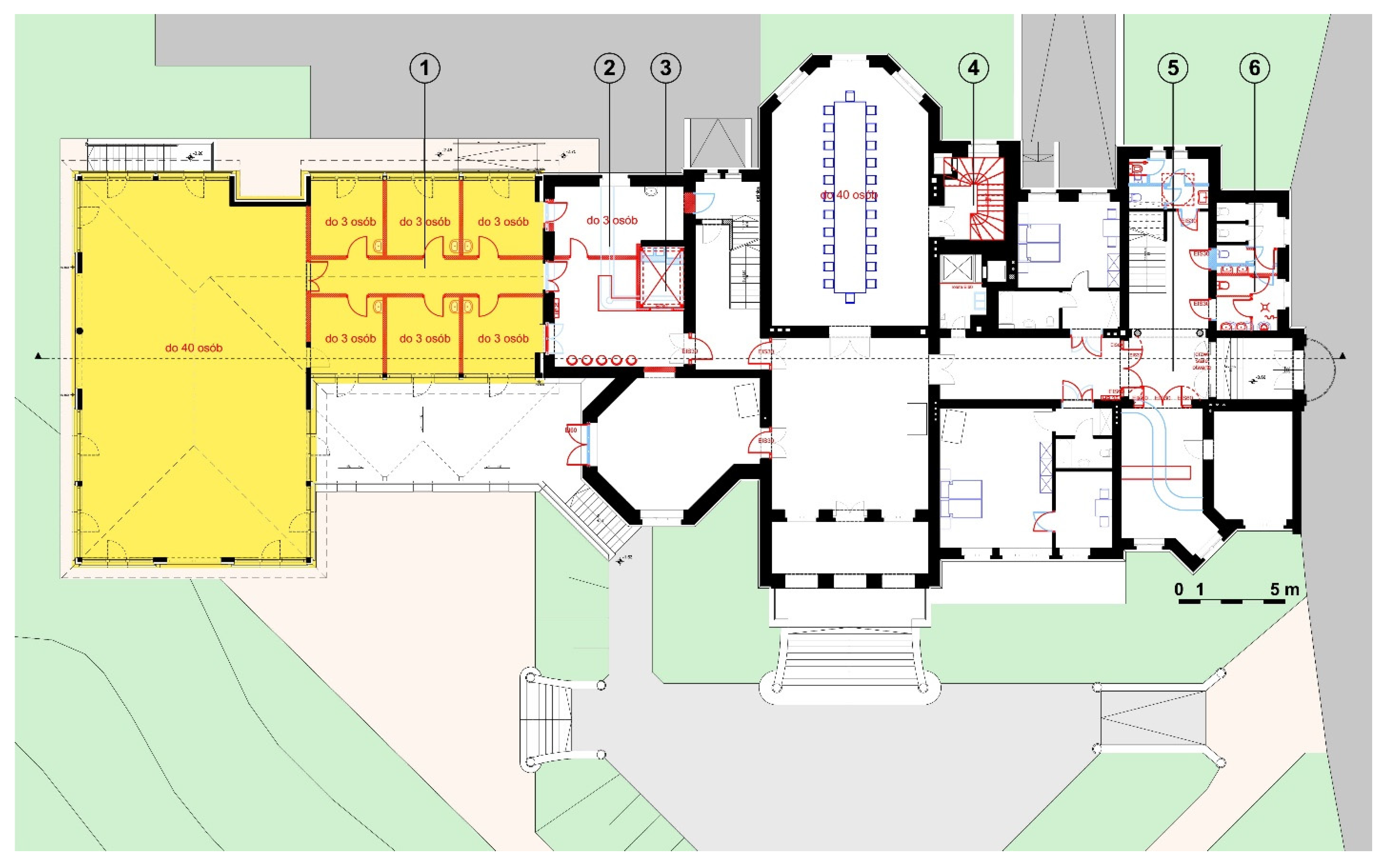

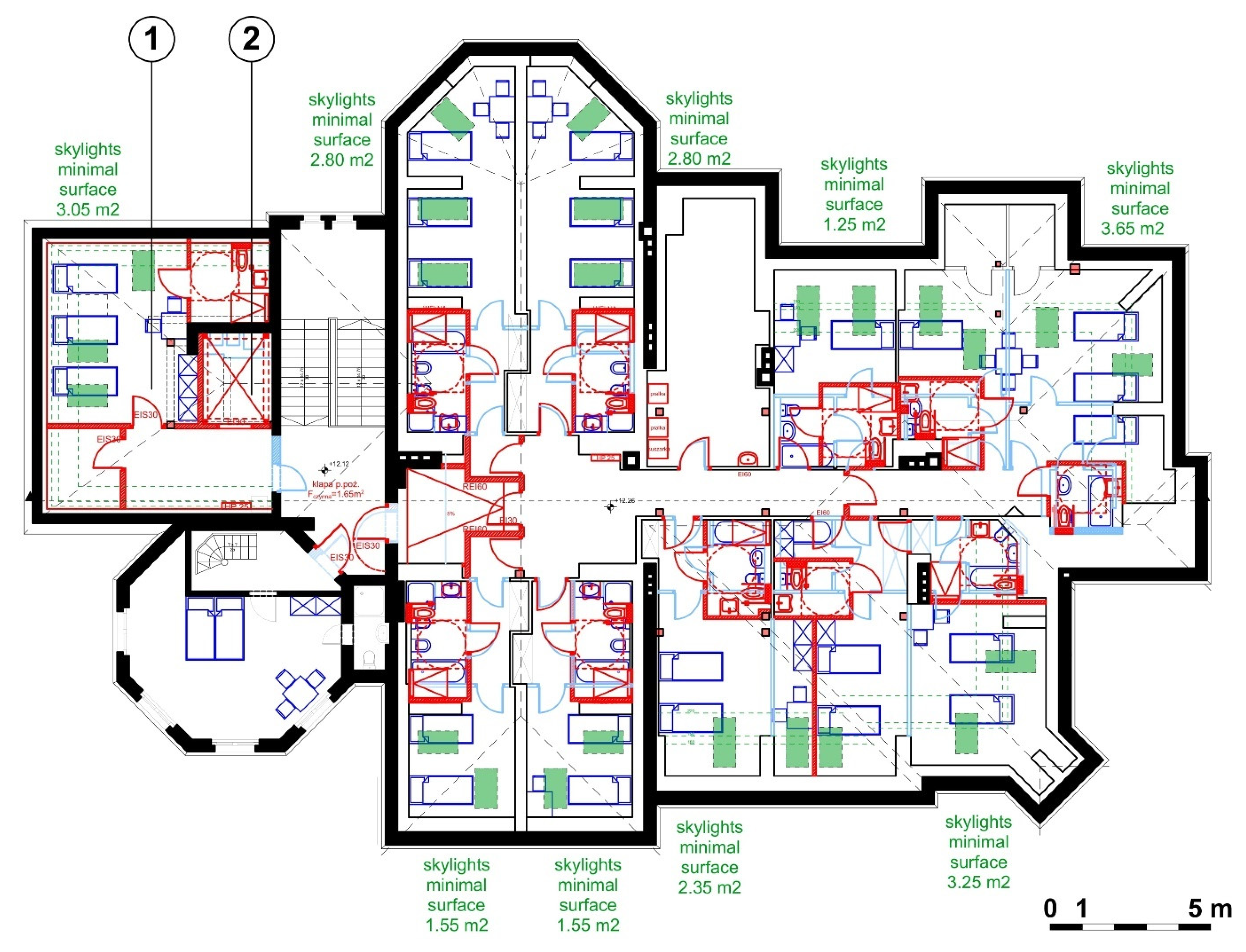

Before starting the design, a detailed inventory of the facility was made and the necessary changes to the layout of the interior were determined—due to its change of function as well as due to fire regulations and technical requirements. On this basis, a conceptual design of the functional changes inside the palace was developed for the needs of the DPS. The most important legal acts regulating the operation of Nursing Homes (Retirement Homes) which had to be considered, were: the Act of 12 March 2004 on social assistance; the Act of 11 March 2004 on taxation of goods and services; the Ordinance of the Minister of Social Policy of 28 April 2005 on the issuing and withdrawal of business permits in the field of running a facility providing round-the-clock care; and the Regulation of the Minister of Labour and Social Policy of 23 August 2012 on social welfare homes. The external body (facades and roof) of the facility was left virtually unchanged. This conceptual design became the basis for the formation of the conditions for the development. The conditions for the development were positively assessed by the Provincial Conservation Office in Szczecin. Based on these conditions, a multi-disciplinary design was prepared for the adaptative re-use of the palace building (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

The main changes that have had to be introduced in relation to the existing conditions consist of ensuring appropriate fire protection conditions, i.e., the introduction of a passenger-goods lift with a rescue function; the separation of fire zones, including the separation of the up-to-now open staircases by means of walls and fire doors, and the replacement of internal doors with woodwork of appropriate fire resistance and a clear width of 90 cm; the introduction of hydrant risers and a voice alarm system; the installation of a smoke exhaust system for the evacuation staircases, and the raising of the guard rails of the emergency stairs, etc.

The hitherto-unused attic of the building was converted into residential rooms with bathrooms. In order to ensure the proper lighting of the rooms, it was necessary to introduce skylights in the roof, so as not to change the form of the external facade. These windows, due to the shape of the roof and cornice, are not visible from ground level. The wooden roof truss in the attic was protected against biological and fire corrosion by covering the wooden elements with plasterboards. The roofs were insulated with mineral wool. The roof sheathing, flashing and roofing felt were replaced. Particular attention was paid to the seals between the flat roof and the vertical walls of the tower and the parapets of the façade. Hotel rooms, intended for the permanent residence of residents, as well as bathrooms in these rooms, and sanitary facilities for general use on the ground floor, also required re-adaptation. The bathrooms were enlarged, adapting them to the requirements relating to the movement of disabled people in wheelchairs, including the elimination of floor thresholds and other architectural barriers that had existed in the building. There are glass partitions with doors, referring to the drawing of historical partitions, separating the hotel corridors from the emergency staircases. Apart from the living rooms, the palace also includes a catering complex with a modern kitchen and storage facilities in the basement and a dining room in the former ballroom on the ground floor. The kitchen located on the ground floor was connected by a goods lift and kitchen stairs to provide a meal service to the dining room. In the pavilion (added in 2000), there is a health care unit (consultation and treatment rooms) and a recreation and rehabilitation room. The existing recreational pool in the basement was left for renovation and adaptation. The original layout of the rooms on the upper ground floor, with original stucco decorations and durable fittings in the form of cladding, parquet floors and antique furnishings, has been carefully preserved.

Defects in the ceiling stucco work were corrected, and wooden cladding, high wooden frames and door leaves were restored. The window joinery made of aluminum profiles, installed during the previous renovation in 2000, was left to be replaced during the next renovation of the building, due to the high cost and to its satisfactory technical condition. On the ground floor, one of the rooms was converted into a multi-denominational chapel. The walls of the palace, after filling in the plaster defects, both from the outside and from the inside, were repainted with carefully-selected paint. Bright, pastel tones were adopted, with the window frames highlighted in white. In the interiors, the existing dark colours of the wooden finishing elements of the building (doors, wooden partitions, balustrades, cladding) were replaced with shades of subdued white and warm grey. This contributed to the brightening-up of the interior and introduced a friendly “colourful atmosphere”, which is particularly important for elderly residents. Following the positive results of the consultation with the Provincial Conservator of Monuments in Szczecin, a building permit for the construction design of the palace re-adaptation was obtained.

4. Discussion

The issues of adapting historic mansions and palaces to modern functions have been discussed, taking as an example the historic palace and park complex in Maciejewo (Matzdorf), Western Pomerania.

The case study of the palace in Maciejewo illustrates the thesis that, in order to survive, historic buildings must be used for those purposes corresponding to their structure, and maintained on an ongoing basis. Many residences in the Polish Western Lands have lost their original function and need a new one in order to survive. These processes of functional adaptation will have to be repeated in many similar cases, if monuments are to avoid being affected once again by a loss of functionality.

The method of adaptive re-use has been introduced, in the sense of the revitalization of a facility, combined with a change in its function. The palace in Maciejewo is an example of such a facility; one that is undergoing another functional metamorphosis—adaptive re-use—after having been an agricultural school, a recreation centre and a hotel, to finally becoming an exclusive nursing home.

One of the essential problems discussed during the adaptation of mansions and palaces into a nursing home function is the fact that historical palaces have representative interiors with a large area, which can certainly make it difficult to properly adapt these rooms to, for example, rooms for the residents of a nursing home, without introducing major, destructive changes.

In accordance with conservation doctrine, as adopted in Poland, the historical value of historical objects constitutes a superior value to that of utility needs, and their adaptation should be adequate to meet the requirements of preserving those values. The adaptive-reuse method applies mainly to those historical objects whose value in terms of their original substance and functional systems has largely been degraded or obliterated by deterioration and numerous reconstructions, and whose continued existence depends on them being given a new functionality. However, each historic building has its own individual history, features and specific dimensions.

In the case in question of the Palace in Maciejewo, the planned adaptive-reuse into a nursing home will not affect the existing, historically-valuable features of the facility. The object had already been exposed, since the period just after WW II, to a number of subsequent reconstructions and adaptations, which had left only part of the original interior arrangement in place. In the project approved for execution, no major changes are planned to the representative, historic rooms of the palace, which are located on the ground floor. These rooms will continue to serve the general (social) purposes of the building. The upper floors of the Palace were transformed over 20 years ago into hotel functions. Their adaptation so as to meet the needs of a nursing home requires only minor changes (such as the size of the door openings and the dimensions and equipment of the bathrooms being adjusted for disabled people in wheelchairs). The adaptation of the attic of the palace is a project aimed at acquiring new, but previously extensively used, space for the nursing home, without changing the size of the building’s dimensions. The attic has been divided into separate rooms, in such a way as not to disturb the structure of the wooden roof trusses and to ensure optimal functional and spatial solutions. The provincial conservator’s consent was not obtained for the insertion of windows in the side walls. Therefore, skylights have been introduced, which are sized to provide sufficient light for the permanent residence of people and are not visible from ground level in the vicinity of the palace. In some rooms with larger dimensions, it has been possible to set up more beds (up to four) for patients of the nursing home. It was the investor’s wish to demonstrate the possibility of ensuring the maximum use of the facility. It is obvious that these larger rooms can be arranged with better comfort, if required, for a smaller number of residents. This will depend to a large extent on the formula of nursing home adopted and the health conditions of incoming patients.

Another problem under discussion has been to secure conditions of safety of use (evacuation routes, etc.) and to meet fire protection regulations. These restrictions, in the case of the adaptation of historic buildings to contemporary functions, such as that of a nursing home, must be met, but the solutions applied must also take into account the preservation of existing historic values. This is a matter of making certain compromises, in order to find individual solutions for each case.

In the case of the adaptation project of the Palace in Maciejewo, the issues of evacuation and the means of access to the two existing staircases were solved and agreed. Additional doors were introduced, separating the staircases on all floors, in accordance with the recommendations of the fire protection expert and with the consent of the Provincial Conservator of Monuments. A building permit was obtained for the presented adaptation project. It is currently in the final phase of construction and fitting of equipment.

Another topic for discussion concerns the stylistic integrity of the adapted buildings. “Should new additions and reconstructions, relating to their existing historical substance, be marked in accordance with the letter of the Venice Charter, and to what extent and in what form?” The answer to this question was given in the applied project solutions. As part of the author’s inventive supervision, additional details were developed, in the spirit of preserving the stylistic integrity and authenticity of the building’s historical substance; not imitating the “historical”, but neither exposing their contemporary character.

5. Materials and Methods

The project of the palace in Maciejewo, using the method of adaptive re-use, re-adaptation (also known as renewed adaptation), has been developed according to Adaptive Re-use Design Guidance Note issues, published by the ODASA (

Harrison et al. 2014). This guidance highlights the many sustainable, cultural, economic and placemaking advantages of re-using existing buildings and describes “the adaptive re-use methodology”. This methodology also makes reference to the Burra Charter and Practice Documents published by ICOMOS. There are also several contemporary publications concerning the adaptive re-use method in historic buildings. The adaptive re-use of buildings, where changes in structure sit alongside new programmes and functions, poses the fundamental question of how the ‘past’ should be included in the design for the ‘future’ (

Wong 2016).

Adaptive re-use can be understood as the process of repairing and restoring existing buildings for new or continued use. As such, it is becoming an essential part of architectural practice nowadays. (

Plevoets and Van Cleempoel 2019). In their book, Plevoets and Van Cleempoel have even introduced the methodology of adaptive re-use as a new discipline, developing innovative and creative approaches in order to rethink and redesign existing buildings. The Polish school of conservation of monuments is well known all over the world, and the effects of conservation works can serve as an example. The adaptive re-use method, however, has a slightly different message. According to this method, the restoration of the building is not intended to restore the former glory of the building, but should be future-oriented, using the traces of the past as the base structure for new layers of contemporary use and architectural shape.

6. Conclusions

The type of adaptive re-use of historic, formerly-residential buildings to other functions, which was carried out over previous years in Western Pomerania, must, in most cases, be changed due to the threat of the physical and biological degradation of these buildings. In order to keep historic buildings functioning and in good estate, the necessary architectural changes (functional, structural, colour, etc.), and other changes resulting from the introduction of new functions, must be implemented. It is, however, the aim of adaptive re-use methodology, as applied in this project, to maintain as much of the existing historical elements of the facility as possible.

Historic residential buildings with park surroundings constitute a unique historical heritage, requiring the care of conservators. This care should be carried out regardless of their significance or the effects of historical events that took place there.

In the process of adaptive re-use, particular attention should be paid to the preservation of the authentic parts of buildings and their equipment. The historic reconstruction of non-existing elements of the facilities should be an exception.

The revitalization and reconstruction of the compositional values of residential parks requires early and appropriate cartographic, geological and hydrological analyzes, as well as in-situ surveys.

According to the adaptive re-use method applied here, the restoration of the building is not intended to restore the former glory of the building, but to be future-oriented, using the traces of the past as the base structure for new layers of contemporary use and architectural shape.