Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensely impacted art production and the art market all around the world. This is dramatically visible inside the Patua or Patachitra communities in Medinipur, West Bengal, where Patachitras’ scrolls characterise the economy of folk-art communities in the so-called villages of painters. Patachitras’ singing pictures belong to an ancestral tradition of storytelling and performing art. For centuries, new themes have been embodied inside the Patuas’ repertoire, creating a living heritage that has always reflected the political, religious, cultural, and social main events and, ultimately, COVID-19. Resilience has always been an important component of this heritage, as social changes and new kinds of entertainment have changed the audience addressed and the performances’ function. In the last few decades, the role of travelling artists has resisted and been readapted to the global art market by approaching art fairs and festivals both inside and outside the villages. Now, the impact of COVID-19 on the economy of these artists has been severe, as art fairs and exhibitions have been cancelled, and lockdown orders have stopped tourism and travels, significantly reducing their income. Thus, new approaches and virtual spaces of exhibiting are being experimented with to support the survival of these artists and keep the performances’ essence alive. This article aims to address how the pandemic has affected Patuas’ art market and production both from an economic and social perspective. The difficulties encountered due to the restrictive measures and the impossibility of performing will be analysed through an empirical approach. Based on telephonic interviews conducted with 30 hereditary Patuas from Naya between April 2020 to April 2021 as part of the project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus”, the article hopes to shed light on the impact of the pandemic on hereditary, performing castes in India, which might mirror the experiences of similar groups in the rest of South Asia. The article will also try to outline the future perspectives for the art market of these folk artists. The article consists of two parts: the first traces the transformative journey of Patachitra and Patachitrakars, and the second focuses on the impact of the pandemic through deploying the concepts of precarity, precariousness, and resilience.

1. Patachitra Cultural Heritage: An Ancient Tradition Facing the Art Market

Patachitra art, dating back more than 2500 years, is probably one of the oldest artistic traditions in the whole of India (Chakraborty 2017). The expression “Patachitra ” is a combination of the Sanskrit word “patta”, which means woven fabric, and “chitra”, that is, painted (Chakraborty 2017). The word “patta” was then transposed into the Bengali language as “pata” or “pat”.

The “pata” or “Patachitra” is made by storyteller artists who have transmitted this cultural tradition for generations. Although these artists are traditionally referred to as Patuas, they now prefer to be known as Chitrakars, which means “producers of paintings”.

Patachitra heritage is a traditional folk art in which the artist performs a song accompanied by the unfolding of a painting to visually show the content of the narrated story. The peculiarity of Patachitra paintings is that they are lined with fabric on the back to give them their characteristic rolled shape and make them more comfortable to carry and preserve, as they originally were made by itinerant artists. The typical scroll, “jarano pat”, reproduces a series of images depicted vertically with a length that may vary between 10 and 20 feet depending on the extent of the story.

Over the centuries, the artistic and narrative practices have remained unchanged.

Traditionally, chant and painting are two joint elements. The chant or “pater gaan” is the central element of the Patachitra, and the painting is realised only after the composition of the melody for the purpose of explaining the song visually and entertaining the spectators. The songs are divided into three phases: the story (“kahini”), the moment of glory (“mahatmya”), and finally the introduction of the artist (“bhanita”) in which he states his name and the village he comes from (Bajpai 2015).

Patua communities are located in different districts of West Bengal: Purulia, Bankura, Birbhum, Murshidabad, and Midnapore. The Midnapore region can be called the home of the Chitrakars, as it houses the majority. The largest community of artists is located in the village of Naya in Pingla district. Particularly from this village, Patachitra art became known also abroad (Chakraborty 2017).

The Chitrakars’ repertoire consists of both traditional songs handed down by their ancestors and new compositions that enrich the personal collection of each artist. It can be divided into three main groups: traditional, social, and contemporary or global.

The traditional register deals mainly with mythical stories and characters from Hinduism as well as some from Islam. The religious aspect is certainly one of the predominant components, as Hindu mythology and Muslim saints have been part of the repertoire for generations. Interestingly, Patuas have changed religion several times over the centuries, moving closer to the most influential or convenient one. Originally, they were Hindus (Chandra 2017), but now they constitute a very special case within Indian society by reproducing mainly Hindu images and idols but formally residing in Islam.

Among traditional episodes, there are also scenes of tribal life, wild animals, and folk tales, such as the marriage of fish and birds.

Besides religious and epic contents, secular themes related to Bengali society, its history, and life in the village also play an important role. Namely, another relevant aspect is covered by social issues. In the past, as itinerant artists who moved from village to village, the Patuas used to spread the news and have an informative function. It is possible to say that they have always looked carefully at the context around them, allowing themselves to be influenced and influencing it in turn. Thus, Patachitra also recounted deeds of kings and locally significant events both from a political and social perspective.

In recent decades, social themes have emerged more systematically with the support of local NGOs and the development of social awareness projects through Patachitra art. Themes such as HIV prevention, sexual diseases, education, women’s health, and rights have now become popular stories for Patuas:

In addition to social themes, from the late 1980s onwards, Chitrakar’s repertoire has continued to evolve to include contemporary global affairs. Already started during colonialism, this attention to global themes has increased with the arrival of new media and international news. Particularly, they had a strong impact not only on the Patachitra audience but also on the artists themselves, influencing their production and stimulating their sensitivity to global events in a strong manner.[...] they needed to innovate for their performances to remain fresh and relevant to contemporary society and the issues that confronted it. The Patuas thus developed a new genre of a song called samajik gaan, or “social song”, which did not replace pauranik gaan, but supplemented it.(Korom 2017)

Moreover, artists who now have the opportunity to participate in fairs and to travel are more exposed to the world around them and tend to receive more inspiration from these topics. Among the most popular ones are terrorist attacks, natural disasters, and political events.

Due to these dynamics, the Patachitra art market has also significantly changed since the last century. During the decades, several instances have changed the role of Patuas artists and the function of Patachitra singing paintings. External influences, such as the introduction of new types of entertainment, the arrival of tourism, and the logic of the western art market, introduced mechanisms unknown in the rural villages, influencing Patachitra’s production in different ways.

In origin, Patachitra was not for sale, and Patuas reused them several times during their itinerant journeys. The scrolls were used to accompany the performance and usually were not sold or left to the audience, as Patuas had to move from village to village.

During the XX century, Indian society underwent profound changes as a result of new social and cultural influences. In the thirty years between the period of independence from colonialism and the 1980s, the role of the Chitrakar started to decline as a consequence of the growing disinterest in rural entertainment.

With the introduction of new forms of entertainment, such as radio, television, and cinema with Bollywood films, patrons and villagers began to show less and less interest in the Patuas’ epic-religious performances (Hauser 2002). Many artists were forced to abandon their traditional occupation for more lucrative jobs: some migrated to the cities for day jobs; others took up farming, trading, and rickshaw transport (Sen Gupta 2012) to survive and provide food for their families.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, few Patuas still pursued their occupation, and the art of Patachitra appeared to be a tradition on the verge of disappearing.

This art form would have risked extinction if it had not found a way to introduce a double evolution: the themes addressed and the role of the artists (Chakraborty 2017).

Therefore, Patachitra’s commercialisation mainly emerged with the decline of Patuas’ demand to breathe new life into the tradition and provide the artists with an economic return.

The new phase began in the 1970s with the demand of Calcutta’s urban elite (Hauser 2002), who were uninterested in performances and willing to buy Patachitra and other artefacts just for collecting reasons as a demonstration of their social status.

Soon after, with the growth of tourism due to the promotion activity of local NGOs, these selling dynamics started to increase, and the traditional practice was applied to new artefacts to satisfy the touristic demand.

It is possible to say that Patachitra cultural heritage followed a two-fold direction: first with the diversification of artefacts and then with the mass sale of Patachitra.

The diversification of Patachitra art onto new objects became functional to satisfy the tastes and needs of new potential buyers and to provide the Patuas with a more secure economic income. Begun as early as the 1990s, the production of new artefacts increased exponentially over the years.

The style, subjects, and decoration of Patachitra were applied to various commercial items, such as umbrellas, vases, lamps, t-shirts, bags, scarves, and other items.

At the basis of this diversification were the needs of the buyers, for whom it is easier to carry something small rather than a long scroll. Moreover, these objects are preferred as they are part of everyday life and can be used for other purposes while at the same time being a tangible memory of the visit to the rural context.

By now, almost all Patuas have dedicated themselves to these new productions. This phenomenon mainly regards the village of Naya and, to a lesser extent, also the village of Habichak in Medinipur. For Habichak, the creation of artefacts began more recently and only after workshops organised in collaboration with the Chitrakars of Naya. While in other villages further north, like in the Purulia district, no alternative products can be found because of the extreme poverty of the artists who do not receive any external support and therefore can only afford to buy the sheets of paper.

The new objects on which to paint were first introduced by the NGOs, while today, the purchase mainly depends on the economic availability of the individual Patua. Naya village, more involved in these activities, was able to enjoy the income from sales right from the start, which enabled the artists to buy back the items and diversify their production. Today, every artist at Naya offers a large number of objects decorated with this technique along with Patachitra scrolls.

But with the selling, another significant change has involved Patachitras’ production and types. Whereas in the past, each artist used to create a dozen Patachitras to take with him for the travelling exhibitions, today, the quantity produced is extremely large.

Earlier, each painting was a unique piece, used several times until it was almost worn out. Today, dozens and dozens of scrolls depicting the same theme can be found at local markets or in artists’ villages. In terms of production, sizes also have changed. While in the past, only long Patachitra (“jarano pat”) used to circulate, over time, smaller rectangular and square formats (“chaukosh pat”) were introduced. The latter are easier to sell, as they are usually preferred by buyers and tourists for their easy transportation.

Some Patuas of Midnapore have also taken up the Jadupatuas scrolls of Bihar, i.e., smaller scrolls depicting tribal themes and painted only in different shades of brown (Hauser 2002). Still others have started painting mainly horizontal formats, which were in great demand among the urban elite to be used as wall decoration. Commercialisation has thus led to more consistent production of “pata” depicting a single image or character.

For visitors, Patuas’ exhibition often represents a kind of entertainment whose intrinsic meaning is not grasped, as they are more interested in the final purchase. This partly explains why it is no longer the performance that is remunerated but the individual scroll. The lack of attention paid to the songs depends on the demand of the audience. Earlier, the Chitrakar’s activity was rewarded through barter; now, the sale is done through a price that buyers are used to bargaining for.

The market is now almost exclusively tourists, art dealers, collectors, and museum curators. Prices have skyrocketed over the past two decades, but Patuas still live in a barter universe, and everything is negotiable. Therefore, also the Patachitra art market follows the offer and supply chain (Korom 2017).

On one hand, there is still a willingness to entertain through the practice of singing the paintings; on the other hand, the mechanism of selling is slowly weakening the correlation between the two. Some Patuas only perform the most representative scrolls to make the visitor understand the ancient oral tradition, limiting the repertoire to a few popular episodes:

Sometimes, the sung scrolls will not be for sale but instead are functional to the purchase of other smaller Patachitra dealing with the same theme.Now the equation is reversed: it is the scrolls that have taken on artistic value as fetishized objects, resulting in the accompanying songs becoming mere curiosities for a newly emerging international audience whose interests are not simply to be entertained by the vocal performance, which is transitory, but to purchase an object, which is permanent.(Korom 2017)

In this case, the correlation between the communicative experience lived by the observer during the performance and the painting (s)he will take with him is missing. In a way, artistic practice has adapted to the hectic pace of tourism and the market in which visitors have little time to devote to these narratives and are looking for a souvenir to take with them, a tangible symbol of their passage through that place.

If until a few decades ago, the Patachitra of Midnapore had both the characteristics of an artistic and theatrical genre; now, the latter is in danger (Chandra 2017). The art of the Patachitra has changed from performative to primarily descriptive, and it is the revitalisation phase that has reversed the mechanism (Hauser 2002). Whereas before, the scroll had only an accompanying function to the main element, which was the song, now, the opposite occurs.

For Graburn (1969), tourist art stems from the need to reformulate tradition with clear commercial intent. It must not only reflect the tastes of buyers but also maintain a strong link with tradition and community identity, conveying meaning within the context of its origin. It also represents the creativity of the artists by facilitating the of developing new styles, techniques, and content.

In the villages, there was a declination of the style of the Patachitra on goods subject to consumerism without the latter being loaded with identity meanings or coming from the development of new ideas.

However, interviews have shown that, even if the rural life of these artists is now being replaced by the rhythm and influence of the market, many Chitrakars, especially the more experienced ones, are extremely attached to the practice of singing and practice it as in the past. Therefore, Patachitra art continues to be the communicative tool of this heritage and its tradition, while the new objects are a means of pandering to the demands of the market for financial gain.

Many people who are now taking up this art form do so to seek a source of income and are not interested in learning the creative process and avoid creating songs as well. In this case, a distinction should be made between Chitrakar artists and other artists who are more interested in the economic return.

It is undeniable that many experienced Patuas are now following the marketability dynamics and are influenced by the city life, looking at being more competitive and rewarded.

Nevertheless, the opening to the global context has also brought new opportunities for the Patachitras’ market. Besides the topic of tourism and commoditization, Patuas have also the chance to perform and show their traditional art to several art spaces, museums, and galleries all around the world. Patuas’ scrolls can be found both in local and international galleries, and before the pandemic, Patuas were often invited to cultural exchanges, seminars, and workshops, creating interesting opportunities for exchanges and promotion of this rich cultural heritage.

Due to COVID-19, the exhibition process and the performances have faced an unavoidable arrest, and obviously, Patuas’ life has also changed. In the section that follows, the paper examines the impact of the pandemic on Patuas through the lenses of precarity, precariousness, and resilience, which have been seen as characterizing the creative and cultural industries (CCIs). The analysis is situated in the large body of literature that has addressed the rising uncertainty and unemployment in a number of sectors and focused on the precarity and vulnerability of certain kind of workers, particularly CCI workers.

2. Patuas’ Art Market Facing the Pandemic: Between Precariousness and Resilience

2.1. Precarity, Precariousness, Precariat

Wilson et al. (2020), in their introduction to the special issue “Planetary Precarity and the Pandemic” of the Journal of Postcolonial Writing, trace the etymological roots of the word precarious to “the Indo-European root prek- which came into Latin as the term prex, meaning ‘entreaty’ or ‘pray’, but which is also connected with the word ‘uncertain’.” They argue that the etymological meaning buried in this centuries-old term has been re-enacted and endowed with new meanings in the 20th century and that precarity today has been caused by the effects of global neo-liberal capitalism in increasing worldwide inequality as “more extensive and less visible patterns of global dispossession” and “relatively unstable and dispersed conditions of deprivation and insecurity gain ground” (During 2015). Kasmir (2018), in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, concurs that precarity has not only been perceived as a new condition produced by the neoliberalist regime of capitalism in the late 20th century but has also been defined as an ontological condition marked by anxiety, insecurity, uncertainty, and fear that is transhistorical.

It was Judith Butler’s seminal distinction between precarity and precariousness that set the conceptual framework for the precarity debates. In Frames of War, Butler (2010) defines precarity as “a politically induced condition”, a state of affairs often caused by failures in the national state. In her scheme, precarity is different precisely because it is unequally distributed. Precariousness is the inherent state of vulnerability and dependence resulting from such inequality whereby subjects might be exposed to disease, violence, poverty, and civil war. Butler regards precariousness as a generalised human condition that accrues from the fact that all humans are interdependent on each other, and therefore all are vulnerable. Precarity is often used together with the terms precarious, precariousness, and precariat. In contrast to the term precariousness, by which human life can be understood from a collective, communal, and interdependently political point of view, the precariat refers to the individual’s vulnerability as a result of his or her material existence, illustrating Giorgio Agamben’s motion of vita nuda or bare life (Agamben 1998). As Butler has shown, some lives are perceived as more legitimate as lives in the frames established by state and the media discourses. The economist Standing ([2011] 2016) proposes the notion of the “precariat,” a neologism combining “precarious” and “proletariat” that describes a “class-in-the making.” Its condition is marked by labor insecurity, stable occupational identity, and the lack of a collective voice. Standing’s notion of the precariat as a new global class has been disputed by many, such as Breman (2013) and Harvey (2012), who advances the position that given that the secure workers and the precariously employed are antagonistic classes, Standing’s precariat concept may stall rather than facilitate that project.

2.2. Precarity and the CCIs

The term precarity entered the academic vocabulary in the 1980s to describe the general condition of workers, the majority of whom are engaged in the informal economy (Casas-Cortés 2014; Castel 2003; Neilson and Rossiter 2008; Lorey 2015). This condition is articulated to the new labour regime in the post-Fordist economy characterised by a permanent feature of capitalist development, as production was being reorganized through flexible labor regimes. According to Castells and Portes (1989), precarity is the outcome of the normalization of informal work or employment as the defining feature of work in Western economies in the late 20th and early 21st century. Disengaging the notion of informal economy out from a geopolitical hierarchy in which the informal was understood to exist primarily within the Global South, Castells and Portes (1989) argued that the “informal economy is universal” cutting across countries and regions as well as diverse economic classes. This transformation of the nature of work has placed middle class workers with informal, unstable employment in the global North in the same category as marginalised, low-paid workers in the global South, a large percentage of whom have always been and continue to be employed in the informal sector (Han 2018). According to Standing ([2011] 2016),

Over the years, a large body of work has emerged that has foregrounded the difference between the creative and cultural industries (CCI) with other industries in terms of the uncertainty and insecurity that has always characterised the cultural and creative workers (CCWs). This is largely due to the fragmented and irregular nature of the employment, short term contracts, freelancing, self-employment, transitory nature of work, and so on. Abbing (2002) focuses on the CCIs’ distinctive characteristics and presents them as “exceptional”. Caves (2000) identifies three important principles in the creative and cultural industry, namely the “nobody knows” principle with respect to the nature of demand and supply; the “art for art’s sake” orientation of workers; and “the motley crew” and “how time flies” principles that acknowledges the time-bound nature of the work. Other scholars highlight the interconnected nature of skills and highly skilled individuals as well as the collaborative nature of work in the CCIs.As the 1990s proceeded, more and more people, not just in developing countries, found themselves in the status that development economists and anthropologists called ‘informal’.

2.3. Precarity, CCIs, and COVID-19

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, a large body of literature has addressed the rising uncertainty and unemployment in a number of sectors and focused on the precarity and vulnerability of certain kind of workers. In particular, the literature on the CCIs has brought to light the increasing vulnerability and precarious state of workers employed in this sector. Comunian and England (2020), in one of the earliest essays “Creative and Cultural Work without Filters: COVID-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy”, focus on the UK to examine 22 surveys conducted in the beginning of March 2020 to raise certain fundamental questions related to the cultural and creative industries. They identify three features of the CCIs, namely the characteristic precariousness of the industry due to uncertainty of the length of employment, the need to look at CCI work with filters, and the resilience that has been isolated in CCI workers following the 2008 economic crisis. Their findings reveal that although the surveys bring out visible critical factors, invisible personal and long-term sustainability has not been addressed. Banks and O’Connor (2021), in their introduction “‘A Plague Upon your Howling’: Art and Culture in the Viral Emergency” to a special issue of Cultural Trends, trace the international emergence of state policy in relation to the cultural and creative sector in the wake of COVID-19. In their view, the induction of the cultural and creative sectors in the industry and their entry into the market 40 years ago has made them vulnerable to the instabilities of the market economy and that state cultural policies are often influenced by the CCIs’ new status as industry where the market is expected to regulate the demand and supply curve. Another way of justifying state policy’s neglect of the culture and creative sector is to cite the flexibility, freedom, and self-employment avenues that CCI workers demonstrated during the last economic crisis in 2008. A report, “Culture, the Arts and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Five Cultural Capitals in Search of Solutions” by Anheier et al. (2021), reviews the cultural policy responses of Berlin, London, New York, Paris, and Toronto during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic through the lens of their respective governance capacities. Although these scholars have pointed to the wide disparities between state policies in different parts of the world, particularly those between the global South and the global North and within affluent nations with respect to ethnicity race and gender, not much research has been done on the impact of COVID-19 in the global South, particularly on marginalised folk artists.

2.4. Patuas, Precariat, and Ontological Precarity

Han (2018), in her essay “Precarity, Precariousness, and Vulnerability”, focuses on the terms lumpen proletariat and informal economy, which have had an impact on the notion of precarity as a historical condition in relation to the notion of the precariat to explore the ways in which these terms offer an image of the state that is inherited by the term precarity. Then she turns to examine the exclusion of impoverished peasants and other informal workers in the term lumpen proletariat, which has a Marxist lineage, in describing the struggles of the urban working classes employed in the formal sector in the global North. This inherited meaning of precarity that percolates to the states’ understanding of the definition of the precariat, she argues, fails to address the issues of poverty, uncertainty, and unemployment that have always plagued the majority of informal workers, particularly in rural parts of the global South. It is her turning to the second meaning of precarity “to chart a tension between asserting a common condition of ontological precarity and the impulse to describe the various ways in which vulnerability appears within forms of life”, which might offer a framework for examining the hereditary performers of Naya in relation to the term precariat.

Unlike the urban proletariat and those who have been cast in the informal economy under neoliberal capitalism, the life worlds of these hereditary performers who eked out a meagre living and led a hand-to-mouth existence as nomadic entertainers until the 1970s have been defined by uncertainty and insecurity about their own, their community’s, and their art’s survival for centuries. Korom (2006) argues that the Patuas’ lifeworlds were defined by abject penury and hardships before they found their way into settlement, security, and acquired some degree of material well-being. As Dukhushyam Chitrakar (2020e), one of the Patua elders of Naya, explains, subsistence has always been a matter of chance and probability for the nomadic performers:

Dukhushyam Chitrakar’s niece, Baharjaan Chitrakar, who lost her father at a very young age, recalls that she would often accompany her father, and even her grandfather, to villages, where they would perform to their scroll paintings and receive rice, pulses, and other items in return for providing entertainment. The breakthrough, in their case, occurred when her uncle sold some of their creations in Kolkata and earned a decent amount of money, which he shared with his family members, including Baharjaan Chitrakar (2020d). Amit Chitrakar grew up watching the difficulties faced by Patuas in earning a livelihood. For someone like his father, who was formerly a resident of Chaitanyapur in East Midnapore district, Patachitra was not sufficient for providing even bare subsistence. According to the now well-known artist, their families would have to wait till dusk for Patuas to return with whatever they would have collected throughout the day from the rural households to be able to prepare their dinner in the past. Now an established artist, Jaba Chitrakar and her husband had to wander around in nearby villages in the past displaying “pat” in order to make both ends meet. Jaba recalls the days when they would both go to different villages and bring back food and clothes in return for the entertainment that they would provide.Patuas have undergone all sorts of oppression be it social or economic. And yet they have been able to earn their subsistence to this day overcoming all types of adversities, no matter how difficult that might have been. At the very beginning [,] we used to go to villages and act as entertainers, showing our paintings and narrating the depictions that were set to tune by us. There was no guarantee as to whether we would get anything in exchange from the households we visited in the village. Some days were worse than the others when we would return empty handed and had nothing to eat. We, as a community, have been able to put food on our plates for quite a long time now. Our children have the opportunity to attend schools and colleges, and we are done with the fear of going hungry for a day.

The instability in the Patuas’ lifeworld, a part of the socio-economic difficulties they face, accrues from the irregular nature of patronage until recently. Due to instability, several Patuas were forced to abandon painting for other occupations before returning to their hereditary calling. Poverty stricken Dulal Chitrakar, now in his 70s, who moved to Naya during the 1950s, had to spend a number of years doing odd jobs, including pulling a rickshaw. The London-returned, now celebrated Yaqub Chitrakar faced many challenges while growing up that compelled him to set aside his desire to be a Patua and work as a cattle driver, a porter, and even as a mason, for varying periods of time. The son of the well-known Patua Amar Chitrakar, National Award winning Patua Anwar Chitrkar, felt disinclined to take up “pat” as a career due to his family’s impoverished condition. Instead, he decided to pursue tailoring and left his job only in the latter half of the 1990s to resume his hereditary profession. Sanuyar Chitrakar, too, joined his brother Anwar after working for nearly fifteen years as a tailor before returning to Patachitra.

Despite having found economic stability due to the growing demand for their products and increased recognition since the 1990s, the Patuas continue to be afflicted by an undefinable angst and insecurity, which conforms to the second meaning of precarity as an ontological condition. Rahim Chitrakar (2020h), Dukhushyam Chitrakar’s son, believes that these existential insecurities continue to haunt them:

Our experiences in being Patuas have been enlightening but nevertheless tormenting too. While growing up, we used to hear that our fathers used to go to villages to beg for food. We are lucky now that none of us have had to beg for food. But those memories are always haunting us like a specter from an ignoble past, affecting our present dispositions. We have always felt threatened.

2.5. COVID-19, Patua, and Precariatization

Precarity, as an ontological condition experienced by the Patuas for centuries, has become intensified after the onset of COVID-19.

But the current precarity is primarily due to the economic instability caused by the severely diminished demand for “pats” and live performances during the epidemic: “The art market had always been volatile if you ask me. It is more now due to the virus”. (Bahar Chitrakar 2020c)

It produces an unnamable anxiety, voiced in Sushama Chitrakar’s “pat” and song:

- The corona virus is so scary. So scary!

- The corona virus is so scary. So scary!

- Hitherto, the name of the virus had never been heard of.

- The corona virus is so scary. So scary!

- The more I watch television, the more anxious I feel.

- The corona virus is so scary. So scary!

(2020)

The Patuas were quick to link their own economic instability to the prevailing economic insecurity due to job losses, closure of businesses, and so on that left most people resources sufficient only for their essential needs:I had to sell the little jewelry that I had. I am now thinking whether it would be a good idea if I go and beg for food in exchange for showing my “pats”. It has completely destroyed all our savings and has imprisoned us in an impoverished life.(Manimala Chitrakar 2020f)

The art market is destroyed just like any other market. I have friends who work in different professions and are facing the same difficulty as I am.(Bahadur Chitrakar 2020b)

When they were invited to exhibit and sell their products in the Handicrafts Mela in Kolkata in December 2020, most were either unable to sell their products or had to sell them at lower prices due to the limited footfall at the Mela. Dukhushyam Chitrakar (2020e) avers,

With this recent rage of the pandemic [,] however, things have changed again. I hear it from my sons that they are not getting the amount of work they used to. Exhibitions and displays have come to a standstill is what I gather from most of those living in the villages.

Another Patua elder, Shyamsundar Chitrakar (2020j), who is in his 80s, sums up the feeling of uncertainty mentioned by each Patua:

But all of us are very unsure about what might happen next. You see, there are fresh cases emerging again and then there is the talk of lockdowns once more. This has made all of us feel very unsure and insecure about the future.

His wife, Rani Chitrakar (2020i), unpacks the uncertainty further:

It is not because of the virus, but there are certain indirect implications because of it. Personally, I have been worried about how we are going to continue with our work if this pandemic continues.

Manu Chitrakar (2020g) echoes their sentiments:

Everyone is worried more about their survival and about their individual health because if the pandemic doesn’t kill us, we’ll surely die because of hunger.

Anwar Chitrakar’s (2020a) response captures the ontological precarity that appears to have been ingrained in the Patua community affecting his creativity:

To be very honest [,] we aren’t being able to work properly. If you ask me, there is always this tension at the back of my mind. I cannot do anything creative because of this. I have to wonder always where I should put my concentration, my paintings or my survival?

Rani Chitrakar’s plaintive appeal to God for cursing the world with the scourge in her “pat” on the coronavirus (Figure 1) and the accompanying song encompasses the etymological meaning of precarity as to pray and entreaty in Wilson et al. (2020):

- O merciful Lord, what have you done!

- Why did you curse people all over the world with the coronavirus?

- That is why artists like us—the patuas—wonder when the lockdown would be finally lifted.

- When can we finally start selling the patas that we have composed?

- O merciful Lord, what have you done!

- Why did you curse people all over the world with the coronavirus?

- Why did you do this?

- Why did you do this?

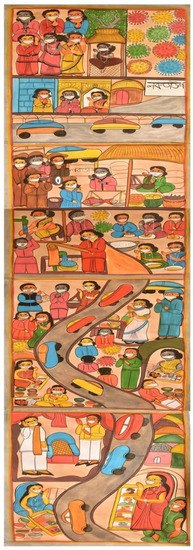

Figure 1.

Rani Chitrakar, “Coronavirus”. Commissioned by Anjali Gera Roy for Project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus”

The explanation Rani Chitrakar (2020i) provides for what she was trying to represent in her painting conveys the connected meaning of uncertainty attached to the etymology of precarity:

My painting is, in principle, a question to God as to why He plagued our lives with a virus as deadly as the corona. It seeks an answer for the cause of such a disaster from God Almighty while creating awareness among people at the same time. In addition to our efforts and strength that are needed to battle this pandemic, we also need God’s blessings.

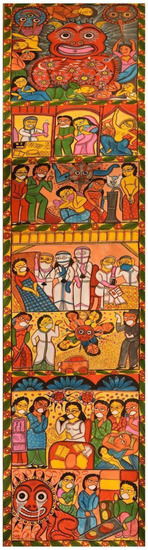

The plaintive prayer in Swarna Chitrakar’s painting (Figure 2), commissioned in April 2020 by Anjali Gera Roy for the project “Folk Artists in the Times of Coronavirus”, which returns to the etymological roots of precarity as to pray and entreat, perhaps accounts for its power to touch thousands of hearts when it went viral in May 2020:

- Listen O Merciful Lord,

- How do I tell you?

- My heart shatters in grief, listening to the woes of people in this corona-stricken world.

- Scientists all over the world are working hard to find a cure to this.

- O Merciful Lord, you are capable of doing anything and everything in this world.

- Kindly listen to the woes of people.

- You have made the scientists and the doctors very intelligent.

- There will again be a day when we’ll all come together and spend our days happily.

- Listen O Merciful Lord,

- How do I tell you?

- My heart shatters in grief, listening to the woes of people in this corona-stricken world.

- How do I tell you?

- Thank you. Greetings!

Figure 2.

Swarna Chitrakar, “Coronavirus”. Commissioned by Anjali Gera Roy for Project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus”

Although Swarna Chitrakar’s painting brought her and Naya considerable media attention (Figure 3) since its being shared on several social media and attracting tweets by several Indian ministers, such as then Minister of State for Human Resource Development, Communications and Electronics and Information Technology, Sanjay Dhotre, and Textiles Minister, Smriti Irani, almost immediately, it did not translate into short-term monetary compensation or long-term state policy on folk artists.

Figure 3.

Swarna Chitrakar’s “Pat” Goes Viral. Acknowledgments to Swarna Chitrakar.

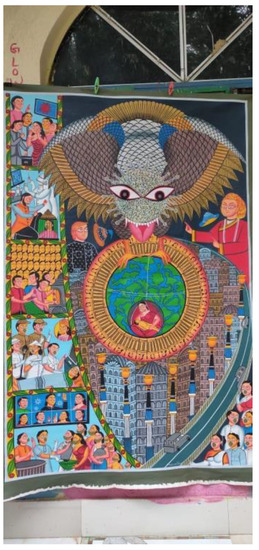

Anwar Chitrakar’s “pat” (Figure 4) garnered another award for him, namely one by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations.

Figure 4.

Anwar Chitrakar, “Coronavirus”. ICCR Award-winning Scroll without Song Acknowledgments to Anwar Chitrakar.

2.6. Resilience

The notion of resilience has acquired wide currency in the recent times and has been adopted in policy-making debates in the 21st century, particularly after the global financial crisis of 2008–2009. The ability of the CCI workers to generate forms of self-employment, short-term contracts, and project-based work during this crisis was hailed as equipping them with a resilience lacking in workers in other informal and formal sectors (Felton et al. 2010). This “creative class thesis” (Florida 2002) has been interrogated over the years since the crash with Donald et al. (2013), asking “if members of the creative class have been less likely to experience unemployment than workers in other occupational groups.” The “received notion of resilience that is atomistic and closed (Pratt 2015)” has been equally critiqued. Asserting that resilience has become a hegemonic term, Pratt (2015), in “Resilience, Locality and the Cultural Economy,” questions “the normative interpretations of resilience as they apply to the local cultural economy” and concludes that “resilience does not mean one thing for the cultural sector.” Rozentale and Lavanga’s (2014) questioning of “the universal assumptions about the nature and characteristics of the creative industries” in relation to “a less economically advanced city” in “The Universal Characteristics of Creative Industries Revisited: The Case of Riga” paves the way for their applicability to rural creative economies, particularly folk and traditional ones like that of the Patuas.

Resilience, as defined in the post 2008 CCI analysis, would definitely not have taken into account the hereditary resilience that has enabled the Patua community to survive for centuries by adapting to the need of the hour. Korom (2006), in The Village of Painters: Narrative Scrolls from West Bengal, highlighted the resilience of the painters of Naya by arguing that the Patua have worked to create a unique form of modernity. The precarity and precariousness that has underpinned Patua existence for centuries due to oppressive penury, instability, and marginalization is compensated by their ingenuity, innovativeness, resourcefulness, and resilience that has ensured the continuity of their practice dating back to several centuries (Korom 2006). Patuas’ adaptation to the market economy following the demise of their ritual informational and entertainment role and the subsequent loss of patronage from the 1970s is a classic example of their inherent resilience.

The Patuas interviewed for this project cited the inability of tourists and visitors to travel to their village; closure or limited avenues for participating in fairs, exhibitions or performances; and economic slowdown and diminishing of the purchasing power of buyers as the prime factors in their inability to market their creative productions and economically sustain themselves after the onset of COVID-19. A few of the Patuas have since been commissioned to prepare “pats” on the coronavirus for governmental and nongovernmental organizations and individual curators and invited to participate in exhibitions, such as the Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose’s 150th Centenary Celebrations in National Museum Kolkata in January 2021, opened by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Some, such as Rani Chitrakar, Swarna Chitrakar, and Jaba Chitrakar, have also been invited to do online and live workshops and exhibitions by state and private institutions. However, invitations have been restricted to approximately 20 to 25 Patuas among the 139 practicising Patuas for several reasons, including age, talent, visibility, media savviness, adaptability to new digital modes, and networks but, most of all, manipulation of market networks by a few to the exclusion of the majority.

While some of the established and well-connected Patuas, like Rani, Ranjit, Swarna, and Gurupada, acknowledged having been invited to conduct live workshops or programmes and being paid a handsome fee, the majority were able to sell their products, albeit fewer and at lower rates, only at the Handicrafts Fair in Kolkata. Most of the Patuas have become adept at using Whatsapp and other social media to share their paintings and products with regular or potential buyers to market their products. However, only a handful, like Rani, Swarna, and Ranjit admitted to having received orders for painting scrolls or objects from their regular or new clients and couriering the same. Elderly Patuas, like Dukhushyam, Shyamsundar, and Dulal lamented that everything has gone online and that they were unable to avail of the opportunities offered by the digital mode, as they were too poor or old to own or use smart phones. Younger Patuas, like Manimala and Bahadur, called attention to the appropriation of the digital marketing openings by a few Patuas with strong NGO and market networks in contrast to others who were contemplating selling their assets or taking up hard labour through the MNREGA scheme of the Indian government to make ends meet.

After having waited for state invitations to create awareness programmes on coronavirus, as they have been since the outbreak of HIV AIDS for nearly a year, the more resourceful Patuas, led by Anwar Chitrakar, Gurupada Chitrakar, Manu Chitrakar, and Bahadur Chitrakar, formed four teams of performers who went around creating awareness in the surrounding villages on their own initiative and expense initially. This perfectly illustrates their paradigmatic resourcefulness in generating self-employment. Subsequently, they were invited by several state departments, including IIT Kharagpur, to stage these awareness programmes using Patachitra performance techniques on remuneration (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Notwithstanding the resilience that the Patuas have imbibed and demonstrated over the centuries and was visible in the initiatives taken by them to find avenues for self-employment, the deadly virus claimed the life of the most enterprising and ingenious of them all, Gurupada Chitrakar, in June 2021.

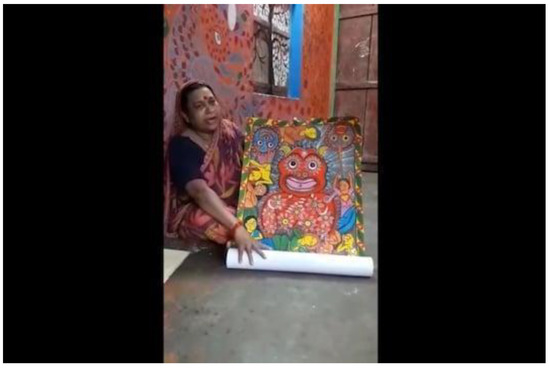

Figure 5.

Third Left Panel from Top: Manu Chitrakar, Swarna Chitrakar, Rani Chitrakar, Manimala Chitrakar, and Gurupada Chitrakar Live in Online Exhibition “Life on Scroll”, Co-hosted by Gurudev Tagore Centre For Culture, Embassy of India Mexico, and IIT Kharagpur, 20 February 2021. Photo Courtesy Gurudev Tagor Centre for Culture.

Figure 6.

Poster Exhibition and Live Performance by Naya Patuas Outside Farmers’ Market in IIT Kharagpur, 18 April 2021. Curated by Anjali Gera Roy for Project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus”.

3. Conclusions

As we saw, lockdown measures forced Patuas to stay in the villages without the possibility of exhibiting and performing and with the risk of starving, as they were not able to travel to fairs and sell their works. Initiatives from the government helped them, but the rations received were not enough. Therefore, with some external support from universities and organisations, Patuas artists started to turn their performances into online contents.

Online exhibitions have become an incredible opportunity also for those Patuas who did not have the chance to travel to show their work and connect to different parts of the world. Surely, this will represent a possible path to be followed in the future also to give all artists the possibility to showcase their scrolls and to promote the oral tradition through live performances.

As scrolls can be found in art galleries, it may represent an opportunity to promote and revitalize the performances, putting the attention on the songs and the processes and not merely to the painting. If properly exploited, this temporary arrest may lead to new opportunities and positive development for safeguarding this cultural heritage and promoting the processes behind the scroll.

Patuas have always understood their heritage in a very dynamic way and have undergone several processes of transformation over the centuries.

They do not simply report these events in a systematic way but add valuable comments as if to convey their own ethical truth. As we have just seen, this happened also with the pandemic and their condition as folk artists.

The adaptation of the Patachitra to influences, both external and internal to society, is an almost continuous symbolism that is intrinsic to their history and tradition. By negotiating their role in the surrounding world, they express the changing identity of the community of artists but also of India itself. Thus, Chitrakars have taken up the challenge of updating their tradition in a novel way, allowing them to assert that metamorphosis and reworking are part of the life cycle of this art.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and A.G.R.; formal analysis, M.Z. and A.G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z. and A.G.R.; writing—review and editing, M.Z. and A.G.R.; supervision, M.Z. and A.G.R.; funding acquisition, A.G.R. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the interviews was received from IIT Kharagpur as part of Anjali Gera Roy’s project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus” (2020–2021).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to Atmadeep Ghoshal, undergraduate intern in Project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus” (2020–2021) for conducting telephonic interviews between December 2020–January 2021 with Patuas of Naya. Copyright of all photographs included in figures belongs to Anjali Gera Roy for her Project “Folk Artists in the Time of Coronavirus” (2020–2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbing, Hans. 2002. Why are Artists Poor? The Exceptional Economy of the Arts. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anheier, Helmut K., Janet Merkel, and Katrin Winkler. 2021. Culture, the Arts and the COVID-19 Pandemic: Five Cultural Capitals in Search of Solutions. Berlin: Allianz Kulturstiftung for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, Lopamudra Maitra. 2015. Myths and Folktale in the Patachitra Art of Bengal: Tradition and Modernity. Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design 5: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, Mark, and Justin O’Connor. 2021. “A Plague Upon Your Howling”: Art and Culture in the Viral Emergency. Cultural Trends 30: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breman, Jan. 2013. A Bogus Concept? New Left Review 84: 130–38. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Judith. 2010. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Casas-Cortés, Maribel. 2014. A Genealogy of Precarity: A Toolbox for Rearticulating Fragmented Social Realities in and out of the Workplace. Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society 26: 206–26. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, Robert. 2003. From Manual Workers to Wage Laborers: Transformation of the Social Question. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel, and Alejandro Portes. 1989. World Underneath: The Origins, Dynamics, and Effects of the Informal Economy. In The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Caves, Richard E. 2000. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce. Boston: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, Urmila. 2017. Patachitra: Una forma artistica e narrativa indiana, locale e globale. Journal of Communication H-ermes 9: 135–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Sharmila. 2017. The Patuas of West Bengal and Odisha: An Evaluative Analysis. Mumbai: Himalaya Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Anwar. 2020a. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Bahadur. 2020b. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Bahar. 2020c. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Baharjaan. 2020d. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Dukhushyam. 2020e. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Manimala. 2020f. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Manu. 2020g. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Rahim. 2020h. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December 20. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Rani. 2020i. Chitrakar, Rani. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. Kolkata. December. [Google Scholar]

- Chitrakar, Shyamsundar. 2020j. Interview by Atmadeep Ghoshal. Telephone interview. December. [Google Scholar]

- Comunian, Roberta, and Lauren England. 2020. Creative and Cultural Work without Filters: COVID-19 and Exposed Precarity in the Creative Economy. Cultural Trends 29: 112–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, Betsy, Meric S. Gertler, and Peter Tyler. 2013. Creatives after the crash. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- During, Simon. 2015. From the Subaltern to Precariat. Boundary 2: 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, Emma, Mark Nicholas Gibson, Terry Flew, Phil Graham, and Anna Daniel. 2010. Resilient Creative Economies? Creative Industries on the Urban Fringe. Continuum 24: 619–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, Richard. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Graburn, Nelson H. H. 1969. Art and Acculturative Processes. International Social Science Journal 21: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Clara. 2018. Precarity, Precariousness, and Vulnerability. Annual Review of Anthropology 47: 331–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Beatrix. 2002. From Oral Tradition to “Folk Art”. Reevaluating Bengali Scroll Paintings. Asian Folklore Studies 61: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasmir, Sharryn. 2018. Precarity. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology. March 13. Available online: doi:10.29164/18precarity (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Korom, Frank J. 2006. Village of Painters: Narrative Scrolls from West Bengal. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Korom, Frank J. 2017. Social Change as Depicted in the Folklore of Bengali Patuas: A Pictorial Essay. In Social Change and Folklore. Edited by Firoj Mahmud and Sahida Khatun. Dhaka: Bangla Academy, pp. 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lorey, Isabell. 2015. State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Neilson, Brett, and Ned Rossiter. 2008. Precarity as a Political Concept, or, Fordism as Exception Theory. Culture and Society 25: 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pratt, Andy C. 2015. City, Culture and Society Resilience, Locality and the Cultural Economy. City, Culture and Society 6: 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rozentale, Ieva, and Mariangela Lavanga. 2014. The ‘‘Universal” Characteristics of Creative Industries Revisited: The Case of Riga. City, Culture and Society 5: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen Gupta, Amitabh. 2012. Scroll Paintings of Bengal: Art in the Village. Bloomington: Author House. [Google Scholar]

- Standing, Guy. 2016. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury. First published in 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Janet M., Om Prakash Dwivedi, and Cristina M. Gámez-Fernández. 2020. Planetary Precarity and the Pandemic. Journal of Postcolonial Writing 56: 439–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).