The Retablos of Teabo and Mani: The Evolution of Renaissance Altars in Colonial Yucatán

Abstract

1. Introduction

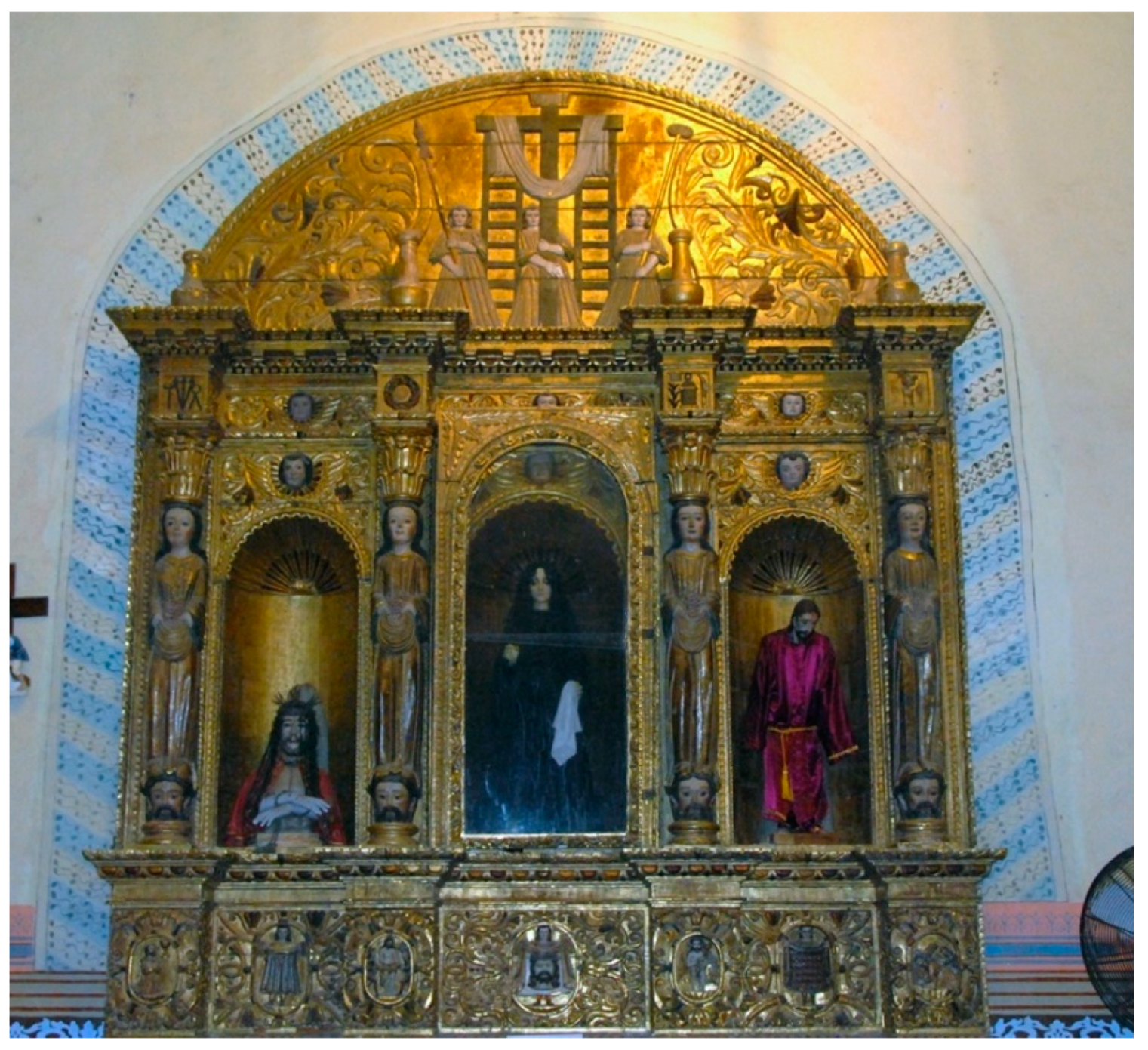

2. The Retablos

2.1. Retablo of Nuestra Señora de La Soledad

2.2. Retablo of San Antonio de Padua

2.3. Retablo of Santa Teresita del Niño Jesús (Las Ánimas)

3. The Discussion: Artists, Caryatids, Dating, Locations

3.1. Artists

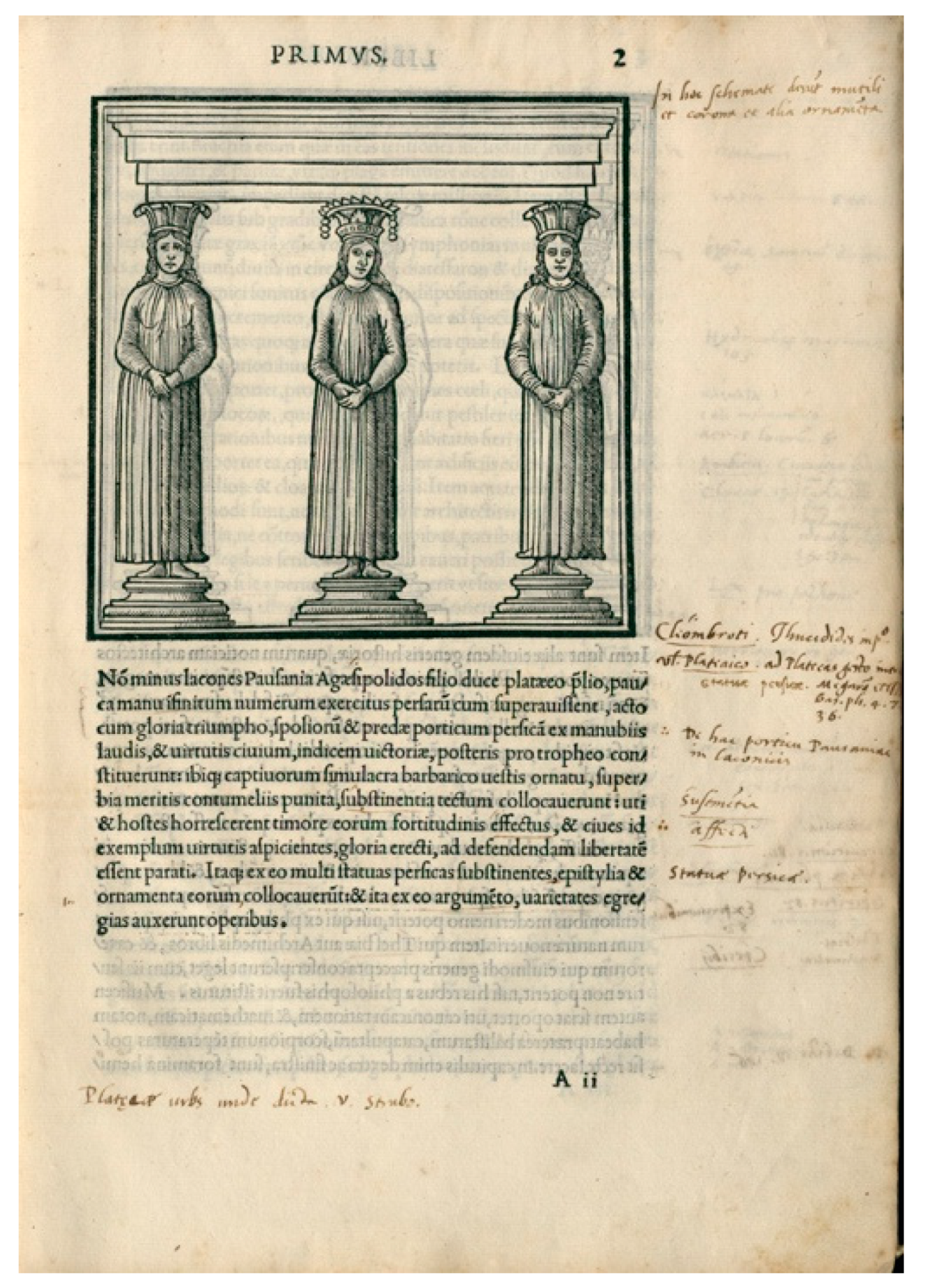

3.2. Caryatids

3.3. Dating

3.4. Locations

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

Archival Sources

Archivo General de Nación (AGN). Castillo, Andrea del. 1572. Autos que sique Dña. Andrea del Castillo, Vda. Del Cap. Francisco Montejo, Conquistador del Provincia de Yucatán, con Pedro Ledezma, sobre el pago de costa de que S.M. le hizo merced por Real Cédula de 18 de mayo de 1572, fechada en Madrid. Section: Hosptial de Jesús. Leg. 464, vol. 264, exp. 4. Mexico City, Mexico.Archivo Histórico Nacional (AHN). Bienvenida, Lorenzo de. 1548. Sobre la provincia de Yucatán, Carta del franciscano fray Lorenzo de Bienvenida al príncipe D. Felipe, dándole cuenta de algunos asuntos referentes a la provincia de Yucatán y quejándose de abusos, 1548–02–10, Yucatán. Section: Diversos-Colecciones. Leg. 23, n. 16, 2r. Madrid, Spain.Published Sources

- Alexander, Rani T. Alexander. 2004. Yaxcabá and the Caste War of Yucatán. Albuquerque: University of Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, César García. 2001. El simbolismo del grutesco renacentista. León: Universidad de León. [Google Scholar]

- Ancona, Eligio. 1889. Historia de Yucatán, desde la época más remota hasta nuestros días. 4 vols. Mérida: Imprenta de M. Heredia Argüelles. [Google Scholar]

- Arrigunaga Peón, Joaquín. 1965. Falso Mayorazgo de la Casa de Montejo. Humanitas 6: 421–37. [Google Scholar]

- Barteet, C. Cody. 2019. Architectural Rhetoric and the Iconography of Authority in Colonial Yucatán: The de Montejo. Visual Culture in Early Modernity. New York and Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barteet, C. Cody. Forthcoming. Retablos of Mani: The Convergence of Maya and Spanish Art. In Polychrome Art in the Early Modern World. Edited by Ilenia Colón Mendoza and Lisandra Estevez. New York and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bolañas, Luis Vega, and Justino Fernández. 1945. Catálogo de construcciones religiosas del Estado de Yucatán. Notas de Jorge Ignacio Rubio Mañé. Mexico City: Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bretos, Miguel A. 1992. Iglesias de Yucatán. Portafolio Fotográfico de Christian Rasmussen. Mérida: Producción Editorial Dante, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Bretos, Miguel A. 1987. Arquitectura y arte sacro en Yucatán: 1545–1823. Mérida: Producción Editorial Dante, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Caramazana Malia, David, and Manuel Romero Bejarano. 2020. Un retablo que hemos de hazer para la dicha iglesia a lo romano. Valencia y Voisín, creadores del retablo mayor de Medina Sidonia (Cádiz). Archivo Español de Arte 93: 205–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas Valencia, Francisco de. 1937. Relación Historial Eclesiástica de la provincia de Yucatán de la Nueva España, escrita el año de 1639. Edited by Federico Gómez de Orozco. Mexico City: Antigua librería a Robredo J. Porrúa e hijos. First published 1639. [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad Real, Antonio de. 1976. Tratado curioso y docto de las grandezas de la Nueva España: Relación breve y verdadera de algunas de las muchas cosas de que sucedieron al padre fray Alonso Ponce siendo comisario general de aquellas partes. Edited by Jorge García Lacroix y Víctor García Castillo Farreras. 2 vols. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricos, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico City. First published 1631. [Google Scholar]

- Cogolludo, Diego López. 1688. Historia de Yucathan. Madrid: Imprenta Real. [Google Scholar]

- Farriss, Nancy M. 1984. Maya Society under Colonial Rule: The Collective Enterprise of Survival. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giocondo, Giovanni. 1511. M. Vitruvius per Jocundum solito castigator factus cum figuris et tabula. Vencia: G. da Tridentio. Available online: http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/Traite/Images/CESR_2994Index.asp (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Gómez-Ferrer, Mercedes, and Juan Corbalán de Celis. 2012. Un contrato inédito de Juan de Juanes. El retablo de la Cofradía de la Sangre de Cristo de Valencia (1539). Archivo Español de Arte 85: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Marta Espejo-Ponce. 1974. Colonial Yucatan: Town and Region in the Seventeenth Century. Ph.D. thesis, University California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Landa, Diego de. 1566. Relación de las cosas de Yucatán. M-RAH, 9/5153. Madrid: Real Academia del la Historia Madrid. [Google Scholar]

- Lizana, Bernardo de. 1983. Historia de Yucatán: Devocionario de Nstr. Sra. de Izmal y Conquista Espiritual. Mexico City: Imprenta del Museo Nacional. First Published 1633. [Google Scholar]

- Mainar, Jesús Criado. 2017. Martín de Mezquita, Tesorero de al catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Huerta de Tarazona (Zaragoza). Merindad de Tudela: Revista del Centro de Estudios 25: 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, John, and Manuel Toussaint. 1942. Tecali, Zacatlan, and the Renacimiento Purista in Mexico. The Art Bulletin 24: 311–25. [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez Rodríguez, Hernán. 1995. Iglesia y poder, proyectos sociales, alianzas políticas y económicas en Yucatán (1857–1917). Mexico City: Colección Regiones, CONACULTA. [Google Scholar]

- Mestre, Miguel. 1688. Vida y milagros del glorioso San Antonio de Padua, Sol brillante de la iglesia, lustre de la región Seráfica, Gloriad de Portugal, Honor de España, Tesoro de Italia, Terror del Infierno, Martillo perpetuo de la herejía, entre los Santos por Excelencia el Milagrero. Barcelona: Publicado por Imp. De la Viuda e Hijo de Sierra. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Alcaide, Victor, Alfredo J. Morales, and Fernando Checa Cremades. 2009. Arquitectura del Renacimiento en España, 1488–1599. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo y Valdez, Gonzalo Fernández de. 1851. Historia general y natural de las Indias. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Padrón Mérida, Aida. 1993. Lorenzo de Ávila y Blas de Oña: Autores del retablo de Santa María en Pajares. Archivo Español de Arte 66: 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pascacio Guillén, Bertha. 2021. ‘Son retablos de talla extremados’: Los colaterales de columnas antropomorfas en el Yucatán virreinal. Fronteras de la Historia 26: 170–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Richard, and Rosalind Perry. 1988. Maya Missions: Exploring the Spanish Colonial Churches of Yucatan. Santa Barbara: Espadaña Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada, Sergio Aguayo. 1993. Pueblos y Cacique Yucatecos, 1550–1580. Mexico City: El Colegio de Mexico City. [Google Scholar]

- Quezada, Sergio Aguayo. 2014. Maya Lords and Lordship: The Formation of Colonial Society in Yucatán, 1350–1600. Translated by Terry Rugeley. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Restall, Matthew. 2001. The People of the Patio: Ethnohistorical Evidence of Yucatec Maya Royal Courts. In Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya. Edited by Takeshi Inomata and Stephen D. Houston. Boulder: Westview Press, vol. 2, pp. 354–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Mañe, Jorge Ignacio. 1941. El Excmo. Sr. Dr. D. Martin Tritschler y Córdova, Primer Arzobispo de Yucatán. Edición especial de la junta organizadora del Jubileo Sacerdotal del Excm o. Sr. Arzobispo de Yucatán Dr. D. Martin Tritschler y Córdova. Mexico City: Sobretiros de ABSIDE. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez de Aguilar, Pedro. 1639. Informe contra los adoradores de ídolos del Obispado de Yucatán: Año de 1639. Available online: http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmc1c1v7 (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Schenone, Héctor H. 1992. Iconografia del arte colonial: Los Santos. 2 vols. Buenos Aires: Fundación Tarea. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, John L. 1848. Incidents of Travel in Yucatán. 2 vols. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Castro, María de Guadalupe. 2014. El convento de Maní, Yucatán, en 1588. Boletín de Monumentos Históricos 31: 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Vanoye Carlo, Ana Raquel. 2011. Esbozo de la historia de la pintura mural virreinal de Yucatán a través del Convento de Santa Clara de Asís en Dzidzantún. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico City, Mexico City, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Vanoye Carlo, Ana Raquel. 2016. La pintura mural del convento de Santa Clara de Asís en Dzidzantún, Yucatán. Generalidades sobre la ejecución de cuatro diferentes etapas. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 38: 217–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargaslugo, Elisa. 1988. Los retablos novohispanos en opinión de don Diego Angulo Íñiguez. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 15: 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vila Jato, Maria Dolores. 1987. El retablo renacentista en Galicia. Imafronte 3-4-5: 33–49. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The years post Mexican Independence led to the neglect and destruction of many parish and townhall records during the Caste Wars of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Frequently, religious sites were targeted and destroyed, including the cathedral in Mérida and the Mani convent (Ancona 1889, vol. 3). The fragmented materials that survive are typically legal records, but there are some church materials that are gathered today at the Archivo Histórico de la Arquidiócesis in Yucatán. Although spanning the whole of the colonial era, the documents are not complete. |

| 2 | Although I identify the box as that of the myrrh, more often there are representations of dice, which are a reminder of the Roman soldiers casting dice for lots of Christ’s simple possessions. |

| 3 | Called the Titulus Crucis (Title of the Cross) the abbreviation of INRI derives from the Gospel of John vol. 19, pp. 19–20 which stated that the inscription was written in three languages: Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. |

| 4 | Saint Diego de Alcalá (or Saint Didacus). He was among the first Franciscans to assist in the acculturation of the Canary Islands. Saint Louis is the co-patron of the Third Order of Saint Francis. He is associated with Franciscans because of his charity to the poor. |

| 5 | Santiago also appeared in Hispanic Americas as Santiago Mataindios. Frequently, the only difference in iconography was the shifting of heads to adopt more Indigenous features rather than European. |

| 6 | It was not until the seventeenth century that one of the convent’s chapels (San Cristóbal) was expanded to operate as a parish church (Cogolludo 1688). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barteet, C.C. The Retablos of Teabo and Mani: The Evolution of Renaissance Altars in Colonial Yucatán. Arts 2021, 10, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020023

Barteet CC. The Retablos of Teabo and Mani: The Evolution of Renaissance Altars in Colonial Yucatán. Arts. 2021; 10(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarteet, C. Cody. 2021. "The Retablos of Teabo and Mani: The Evolution of Renaissance Altars in Colonial Yucatán" Arts 10, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020023

APA StyleBarteet, C. C. (2021). The Retablos of Teabo and Mani: The Evolution of Renaissance Altars in Colonial Yucatán. Arts, 10(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10020023