Abstract

During the seventeenth century, the use of smalt and indigo became increasingly common among painters’ workshops in New Spain. The unprecedented importance of these two blue pigments in oil painting may be explained by artistic and geopolitical circumstances. This article expands on the use of blue smalt—a byproduct of glass production and a material that lacks in-depth study in viceregal painting—by focusing on the technical analysis of El Triunfo de la Eucaristía and La Asunción painted by Cristóbal de Villalpando (ca. 1649–1714), which are part of the collection of the Museo Regional de Guadalajara (Mexico). The technological and material study of both paintings, situated within the trade and circulation of painting materials at the turn of the eighteenth century, shows how the painter deployed techniques rooted in his predecessors while incorporating particular technical adaptations. The authors examine cross-section samples of Villalpando’s paintings with optical microscopy, Scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX), and Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and were able to identify different qualities of smalt as well to suggest a possible provenance. These analyses evidence novel aspects in the painting tradition of workshops in New Spain that ultimately reverberated in practices of the long eighteenth century.

1. Introduction

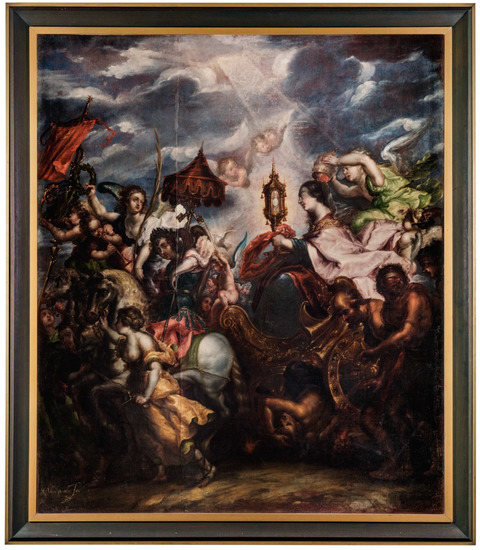

Cristóbal de Villalpando was one of the most influential artists during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century in the viceroyalty of New Spain. He was born around 1649 in Mexico City, and his artistic practice is documented between 1675–1713 (Revilla 1893, p. 83; Gutiérrez Haces et al. 1997, p. 31).1 In 1686, as new painting ordinances came into place, Viceroy Conde de Paredes appointed Villalpando as “veedor”—observer or overseer—of the guild of painters in Mexico City (Toussaint 1982, p. 138; Mues Orts 2008, p. 218). Villalpando worked on several monumental projects for the largest cities of the viceroyalty, like Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Puebla, and took part in the artistic elite of the moment alongside painters like Juan Correa (Hyman 2017). While Villalpando’s artistic production has been largely explored in scholarly research, the studies from a material and technological perspective of his work are still scarce (Arroyo Lemus 2017; Lazarte Luna et al. 2018; Mahon et al. 2019). In this contribution, we analyze two paintings of medium format, El Triunfo de la Iglesia (The Triumph of the Church, See Figure 1) and La Asunción (The Assumption, See Figure 2), both dating between the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth century and currently located at the Museo Regional de Guadalajara. The two paintings are rich in blue smalt, a pigment linked with the production of glass and ceramic enamels from German, Flemish, and Italian regions.

Figure 1.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, El Triunfo de la Iglesia (end of the 17th–beginning of the 18th century), oil on canvas, 198 × 168.3 cm, Museo Regional de Guadalajara, Guadalajara. Photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Figure 2.

Cristóbal de Villalpando, La Asunción (end of the 17th–beginning of the 18th century), oil on canvas, 198 × 168.3 cm, Museo Regional de Guadalajara, Guadalajara. Photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

Both paintings share the same size and format (198 × 168.3 cm). La Asunción gathers two moments in the same visual composition: above, the Virgin rises to the sky, while below, the apostles gather around an empty sepulcher. The inferior register is somber, while the superior is lit from an opening of heaven that wraps around Mary. A group of contorted putti in dynamic postures hold the central cloud upon which the Virgin rests. The work is closely related to a composition by Peter Paul Rubens and engraved by Schelte A. Bolswert.2 El Triunfo de la Iglesia also seems to be inspired by Ruben’s homonymous work.3 In this painting, an angel crowns a woman in a carriage that represents the Catholic church, while a triumphant procession surrounds the central character. Another angel rides a horse holding a canopy as female figures guide three horses leading the dynamic procession. The Church’s carriage runs over dark figures on the ground representing evil. While it is likely that Villalpando took inspiration from Rubens’ engraved composition, this iconographical model had already been deployed in viceregal paintings, as illustrated by Baltasar de Echave Rioja’s 1675 canvas at the Cathedral of Puebla.4 Art historian Nelly Sigaut (1989, pp. 315–72) has studied the strong influence of Rubens’ work in New Spain and particularly the relationship between the engraved sources and the paintings by Villalpando and Echave Rioja.

Villalpando himself painted several iterations of La Asunción, currently located at the Temple of San Martín de Tours, Huaquechula; the Cathedral of Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes; and at the diocesan sanctuary of Guadalupe, Zacatecas. In 1997, art historian Rogelio Ruiz Gomar described the painting from Guadalajara as the most beautiful among all these versions (Gutiérrez Haces et al. 198). Ruiz Gomar also dated the painting around the decade of the 1680s, because the lines are mostly well-defined and only in some areas are the strokes looser and lighter, which will become Villalpando’s signature formal quality that will prevail in future works.

According to the catalog of Villalpando’s oeuvre (Gutiérrez Haces et al. 1997, p. 370) and de la Maza (1964), El Triunfo de la Iglesia was found at the Archbishop’s palace in Guadalajara before becoming part of the museum’s collection. However, Agustín F. Villa (1919, p. 42) argues that the painting was originally part of a retablo located in the sacristy of the Cathedral of the same city.

The documentation related to La Asunción and El Triunfo de la Iglesia, at the Museo Regional de Guadalajara, shows that both paintings were relined with the “wax-resin method”5 between 1973–1976. El Triunfo de la Iglesia had been intervened in previously in 1842 (Sánchez González 2015, pp. 128–29, 193).

In 2016, as part of the museum’s cataloging project (Proyecto para la Catalogación de la Pinacoteca Virreinal del Museo Regional de Guadalajara), the team of the Laboratorio de Análisis y Diagnóstico del Patrimonio (LADiPA), from El Colegio de Michoacán (Mexico), took cross-section samples from the paintings to study the blue pigments used by Villalpando with optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersed X-ray analysis (SEM-EDX), and Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR). The interest in studying the blue pigments from a technological and material perspective stemmed from two unresolved issues: one from a material point of view and the other from an art-historical concern. During the viceregal period, painters had access to a limited blue palette, given that azurite tends to oxidize turning green, blue smalt tends to fade and darken, indigo can fade under certain conditions, and ultramarine blue was too expensive. The authors carried out the study, interested in reckoning with the practices developed to manipulate these materials at the core of Villalpando’s workshop, as well as the technical strategies at play that the artist undertook to acquire the desired pictorial qualities. From an art-historical point of view, by the end of the seventeenth century, the international production and trade of blue pigments—azurite, smalt, and indigo—was reconfigured; thus, the study of the paintings could bring elements to link the impact these market fluctuations had upon their artistic practices.

The novohispano blue palette has been studied by Arroyo Lemus et al. (2012), who found that the use of azurite was prominent in paintings by Andrés de Concha, Simón Pereyns, Baltasar de Echave, José Juárez, and Sebastián López de Arteaga. Interestingly, the authors located smalt in La Virgen de los Dolores by Juan Correa, a contemporary to Villalpando, who continued to use smalt in his paintings throughout his practice (Arroyo Lemus and Amador Marrero 2017, p. 231). This illustrates how a technological change took place by the end of the seventeenth century at the core of the guild of painters. This does not mean smalt was not used before, as Espinosa Pesqueira and Arroyo Lemus’s (2014) in-depth study of smalt used by Simón Pereyns shows, but smalt was used as a base layer for azurite rather than as the main blue. Villalpando’s painting technique has been studied by Mahon et al. (2019), Lazarte Luna et al. (2018), and Arroyo Lemus (2017).6 The painter used smalt as the only blue pigment in the Adoration of the Magi, a painting studied by Mahon et al. (2019) and Lazarte Luna et al. (2018). Arroyo Lemus (2017) also identified smalt in Villalpando’s Moisés y la serpiente de bronce y la Transfiguración de Jesús. These studies constituted an important reference for this work; however, as the results of this research will show, Villapando’s blue palette was more complex.

2. Materials and Methods

Five cross-section samples were taken from La Asunción—but it was possible to study only four—and six from El Triunfo de la Iglesia. The micro-samples were taken with a scalpel from areas where the paintings had small damages like craquelures or fissures.

Paint micro-samples were embedded in Nic-Tone® resin and polished until the paint layer was exposed. The cross-sections were examined with a Leica® DM 4000M Microscope equipped with a Leica® DFC 450C camera. The measurements and microphotographs were taken with the Leica Application Suite 4.0 software.

The cross-sections were later analyzed with a Scanning Electron Microscope JEOL® model JSM6390LV/LGS coupled with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (SEM-EDX) Oxford® model LK-IE250. The EDX results were processed with the software INCA Suite 4.08. An elemental mapping of each cross-section was carried out to choose the areas of interest for the EDX study. For each smalt particle, three EDX sample points were selected at a magnification of 3000×.

The study with infrared spectroscopy was done with a Fourier-transformed infrared spectrometer (FT-IR) PerkinElmer® coupled to a Spotlight 200 microscope. All the studies were performed at the Laboratorio de Análsis y Diagnóstico del Patrimonio (LADIPA-COLMICH) in La Piedad, Michoacán (Mexico).

3. Results

3.1. Painting Technique: The Blues of Cristóbal de Villalpando

The analyses of the cross-section samples demonstrated Villalpando’s differential use of blue layers to paint the skies and the fabrics of the characters’ garments; thus, the results were separated into these categories.

3.1.1. Blues for the Skies

Villalpando painted the skies in two different ways. The first method consisted of a single layer application of blue smalt and lead white [(PbCO3)2·Pb(OH)2 and was identified in the shadows of the sky at the right side of El Triunfo de la Iglesia. In the central area of the same canvas—near the hand of the triumphant Church—a lighter layer surmounts the blue base tone to achieve the desired brighter effect.

The cross-section of the sky near the left edge of the same painting showed a second method to paint the blue sky; here, Villalpando applied a base layer of a blue copper-based pigment mixed with fine smalt (7.85–14.65 microns) and lead white. Under an optical microscope, this layer seems slightly grey, an alteration that could be attributed to the fading of the smalt due to the leaching of potassium, which provokes a shift in the tetrahedral structure of cobalt and oxygen, resulting in fading (Janssens et al. 2016, p. 5). Over this layer of copper blue7 and smalt, the painter applied a thicker mixture of smalt and lead white (See Figure 3).

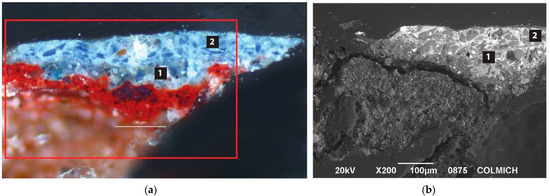

Figure 3.

Cross-section from the sky in El Triunfo de la Iglesia. (a) Under the optical microscope (20×), it is possible to see the two layers rich in blue smalt (1 and 2). (b) In the SEM image (200×), particles of smalt appear as opaque pieces of glass mixed with lead white. Images by LADiPA-COLMICH.

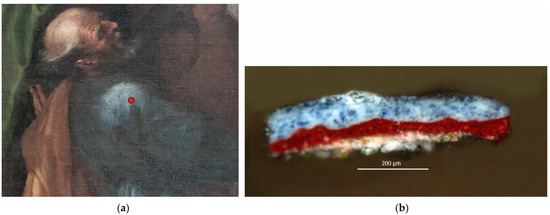

The painter used the same method to paint the shadow of the cloud that supports the Virgin in La Asunción where the first layer is composed of a copper blue pigment mixed with fine smalt (around 10 microns). Villalpando then added a superposition of fine layers of smalt and lead white. In the microphotograph, it is possible to see how the color was toned with glazes (semi-transparent yellow thin layers) in between some of the light layers to achieve the shadow effect (See Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cross-section from a cloud in La Asunción. (a) Under the optical microscope (20×), it is possible to see the superposition of layers over a red lake as well as the yellow glazes in between the white layers. (b) The SEM image (350×) allows for a closer inspection of the particles. Images by LADiPA-COLMICH.

3.1.2. Blues for the Fabrics

The study of the cross-section samples revealed three different ways to paint the blue fabrics depicted in the paintings. The first technique shares similarities to the one described for the skies. The tunic of Mary in La Asunción exposed a base layer rich in smalt, where some of the smalt particles have faded and are gray, while others maintain their vibrant blue. Over this layer, the painter applied a thick layer (58.1 microns) of smalt and lead white, followed by a thin glaze, to finish it with another layer of lead white and less smalt (See Figure 5). The top thin layer modulates the tone, and it is composed mainly of silicon and iron, as the SEM-EDX analysis showed. The blue garment of the kneeling saint on the left corner of the painting was also painted with a one-layer system of smalt and lead white (See Figure 6).

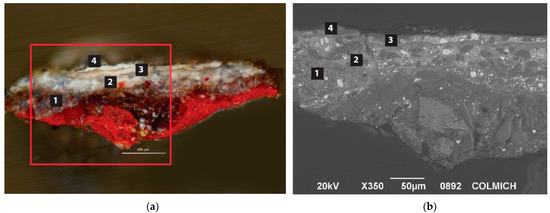

Figure 5.

(a) Detail of the Virgin’s tunic in La Asunción. The area the sample was taken from is marked with a red dot. Detail of photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. (b) Cross-section under an optical microscope (10×). Image by LADiPA-COLMICH.

Figure 6.

(a) Detail of the Saint’s blue garment in La Asunción. The area the sample was taken from is marked with a red dot. Detail of photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. (b) Cross-section under an optical microscope (10×). Image by LADiPA-COLMICH.

The samples of El Triunfo de la Iglesia showed a more complex use of materials to paint the blue fabrics. Villalpando painted the blue tunic worn by the Church with two applications of paint. The first layer, of considerable thickness (118.7 microns), is composed of smalt with a very low concentration of lead white, while the second layer is thinner (22 microns) and very dark. This top layer is rich in silicon and potassium and has a low content of cobalt, which could indicate the presence of very fine smalt, “esmalte remolido”—reground smalt—mixed with indigo, since chemical traces of sodium, magnesium, aluminum, and calcium, usually associated with indigo (Castañeda Delgado 2017, p. 107), were also identified.

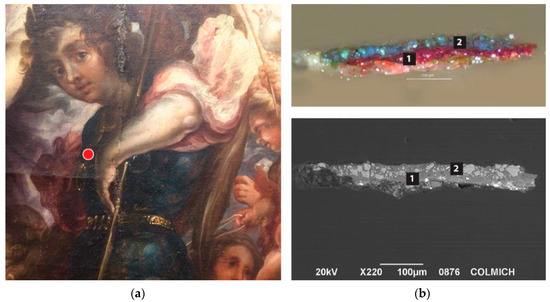

This way of using smalt contrasts with the way the artist solved the blue garment of the angel riding a horse. In this garment, the painter employed the red ground layer as an undertone for a red lake composed mainly of calcium and sulfur, and a low content of silicon, copper, and potassium. This could indicate that the substrate for the organic lake was gypsum (CaSO4). On top of this bright red layer, the artist extended a blue layer with a copper blue pigment mixed with a small quantity of lead white (See Figure 7). The translucent color layers result in a magenta undertone. In a more luminous area of the angel’s garment, the same red lake was identified as a first layer over the red ground. This layer was also rich in orange particles with high lead content, indicating the presence of azarcón (Pb3O4), a material that improved the drying properties of paints. This is also in line with Francisco Pacheco’s recommendation of the use of “aceite graso de azarcón”—fatty oil of minium—as a siccative for lakes and orpiment (Pacheco [1649] 1990, pp. 484–85).8 The same copper blue embedded in a blue matrix of, possibly, indigo,9 extends over the red lake. The painter’s selection of lakes in these samples reveals Villalpando’s mastery of translucency, which he achieved by the superposition of layers that constructed, or “dressed,” the anatomy of the angel. This systematic play of translucent layers as a key element of Villalpando’s painting identity has also been characterized by Arroyo Lemus (2017, p. 13).

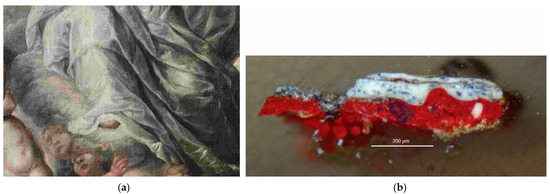

Figure 7.

(a) Detail of the angel’s blue garment in El Triunfo de la Iglesia. The area where the sample was taken from is marked with a red dot. Detail of photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. (b) The cross-section under an optical microscope (20×) (top) and the SEM image (220×) (bottom). Images by LADiPA-COLMICH.

3.2. Blue Smalt: A Closer Look

Blue smalt is an alkaline frit—ground glass—that owes its blue color to the presence of cobalt. To obtain the pigment, sand or quartz (SiO2) was melted with an alkaline salt, which functioned as a flux—like ash, lime, soda, or potash—that lowered the melting point of the mixture. The use of certain fluxes is related to the access artisans had to these materials, so the components found today in smalt can be used to determine the place where the smalt was produced. Spring (2017, p. 5) reports that the use of wood ash rich in potassium was a practice common in the north of Europe, while in the Mediterranean, glass-makers would use sodium-rich ashes. To give the glass its blue color, zaffre (safre or zafra)—the product of the calcination of cobalt-rich minerals like skutterudite ((Co2Ni)As)—was added to the mixture of sand and salt. From the calcination of skutterudite, many mineral species were obtained, including cobaltite ((Co,Fe)AsS) and smaltite ((Co,Ni)As3−x). Once the glass was melted, it was rapidly submerged in water, provoking a thermal shock that fragmented the glass (Gómez et al. 2012, p. 277). The glass particles were separated into different sizes through grinding, flotation, and decantation to be sold as smalt pigment (Seccaroni and Haldi 2016, p. 200).

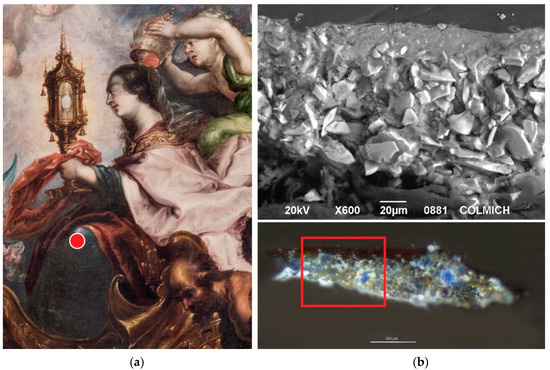

The two paintings studied in this article exhibit different qualities of smalt and different grinding degrees, as well as elemental traces that could indicate the mineral and geographical origin of the blue smalt that Villalpando used. In general, the particles of smalt found in both paintings fluctuate between 7.85 and 48.83 microns. In the seventeenth century, the quality and price of the blue pigment varied according to the size of the particles, the most expensive being the one with larger particles, because they had a more intense blue tone, while the cheapest was the smaller quality, which was thus paler. The particle size also relates to the content of cobalt, as the larger particles have a higher cobalt content (Spring 2017, p. 12; Gómez et al. 2012, p. 277). The smalt identified in the sky of El Triunfo de la Iglesia could be classified as fine smalt—esmalte fino—because it contains particles smaller than 20 microns, while the smalt used for the Church’s tunic was probably high-quality smalt—esmalte grosso—with particles surpassing the 24 microns. It is no surprise that a brighter smalt was used to achieve a deeper blue in the tunic of the main character (see Figure 8). In the painting La Asunción, however, the particle size was more regular in all the analyzed areas, with an average length of 25.59 microns, which speaks about the use of the same material throughout the painting.

Figure 8.

(a) Detail of the Church in El Triunfo de la Iglesia. The area where the sample was taken from is marked with a red dot. Detail of photograph by: Gerardo Hernández Rosales. Reproduction authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. (b) Cross-section under optical microscope (20×) (bottom) and SEM image (600×) (top). The area analyzed with SEM is marked with a red rectangle. Images by LADiPA-COLMICH.

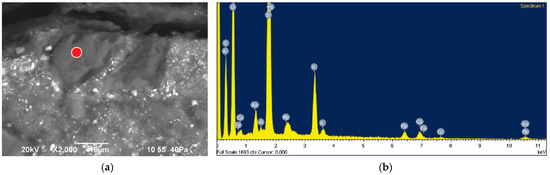

The SEM-EDX micro-analysis carried out in individual smalt particles showed an elemental pattern of silicon, cobalt, potassium, iron, and arsenic as the main components of smalt, while aluminum and lead could be considered secondary components (See Figure 9). The average content of silicon in the samples was high, around 72.52 wt.% SiO2. As per the content of cobalt, two types of smalt were identified: the first type had a cobalt content ranging between 3–4.5 wt.% CoO, while the second type—the smalt found in the tunic of the Church—presented a cobalt content between 6–9 wt.% CoO. High cobalt content resulted in darker blue (Spring et al. 2005, p. 62). This reinforces the idea that Villalpando intentionally used a more intense tone to depict the tunic of the main character.

Figure 9.

(a) SEM image of a smalt particle. The spot where the microanalysis with EDX was made is marked with a red dot. (b) EDX spectrum showing lead, potassium, cobalt, arsenic, iron, and aluminum signals. Images by LADiPA-COLMICH.

The elemental pattern of cobalt associated with arsenic and iron could be indicative of the mineral species used for the zaffre component of the glass. The values of arsenic were higher than cobalt in all of the samples (between 4.72 and 6.82 wt.% As2O3), while the content of iron was regular between 2.61 and 5.25 wt.% FeO (See Table 1). Therefore, the mineral of origin could be cobaltite10 [(Co,Fe)AsS], which contrasts with most of the studies done on seventeenth-century European paintings where the most common elemental pattern is composed of cobalt, arsenic, iron, nickel, and bismuth (Spring et al. 2005; Janssens et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Occurrences of smalt in Villalpando’s two paintings, with quantitative elemental analysis (weight% oxide).

Table 1 also shows the fluctuations in potassium and cobalt content at different sample points. This data could be related to smalt’s differential degradation. Espinosa Pesqueira and Arroyo Lemus (2014) found that the content of cobalt and potassium varies even within the same particle; according to their study, the center of the particles tend to have higher concentrations of these elements, while closer to the edges, the concentration decreases, because potassium tends to leach first from the perimeter. This experiment was replicated in this study with the samples taken from the main characters of both paintings, the tunics of Mary and the Church, respectively (Table 2). However, in the majority of the particles analyzed with SEM-EDX, the potassium content did not show a significant variation between the spots tested, which means that the particles are in a relatively good state of conservation. Only two out of the six particles analyzed showed a significant decrease in potassium near the edges. The variations in the content of cobalt do not seem to be correlated to the variations in potassium. These results are consistent with Spring et al. (2005), who reports that the content of cobalt is not affected by smalt’s degradation.

Table 2.

Evaluation of potassium and cobalt content in different points of the same particle with quantitative elemental analysis (weight% oxide).

The presence of potassium is correlated to the type of alkaline salt used as a flux to elaborate the smalt. The high content of potassium—in addition to the absence of sodium11—indicates that the flux used was potash obtained from wood ashes, a practice more commonly associated with glass production in northern Europe (Flanders and Holland). Calcium, an element also associated with the wood ashes and lime generally mentioned in glass-making recipes (Spring 2017, p. 5), was only detected in the cross-section of the tunic of the Church. Moreover, the smalt particles of this sample (with the exception of one spot) did not show lead, which contrasts with the rest of the smalt samples, where lead was a constant constituent ranging between 1.74 and 10.56 wt.% PbO.

4. Discussion

From a technological point of view, the blue color has always been difficult to work with Pacheco ([1649] 1990), in his treatise published in 1649, describes the Santo Domingo blue—the American azurite—as “el color más delicado y más dificultoso de gastar y a muchísimos pintores buenos se les muere”12 (485). By 1715, Palomino de Castro y Velasco ([1715] 1944, p. 56) in his treatise El Museo Pictórico y Escala Óptica refers to azurite as a “false color” that transforms into a bad green. Palomino de Castro y Velasco ([1715] 1944) preferred to use smalt: “Los azules se pueden labrar de diferentes colores: el más común es el esmalte, el cual se bosqueja mezclando algo con el añil, para que tenga cuerpo y cubra bien el lienzo, y sin más mixtura que el blanco (…) y en estando seco, se labra solo con esmalte fino y blanco”13 (72). Villalpando employed technological solutions that strongly resonate with Palomino’s recipes, particularly to paint the tunic of the Virgin in La Asunción, as well as the Church’s garment in El Triunfo de la Iglesia. In both cases, Villalpando used smalt with no mixture other than white, and in El Triunfo de la Iglesia, he even used indigo as a finishing layer, a technique reminiscent of Palomino de Castro y Velasco’s ([1715] 1944) recommendation to darken the blue tones: “apretando los oscuros con añil” (72).14

Palomino also recommended the use of ground smalt with nut oil as a siccative,15 implying that within the workshop, the painter would re-grind the material. The painter suggested this siccative for ultramarine, indigo, and smalt itself, but warned: “si todo el esmalte se gasta remolido, se pone negro con el tiempo” (Palomino de Castro y Velasco [1715] 1944, p. 61).16 Indeed, according to Spring et al. (2005), small particles of smalt tend to deteriorate more easily. At least three particle sizes were found in Villalpando’s paintings, one with smalt particles larger than 24 microns, which could be denominated smalte grosso, had a high concentration of cobalt (6–9 wt.% CoO), and was used for the darker areas of the fabrics. The second type of smalt had particles smaller than 20 microns—smalte fino or smaltino, a lower cobalt content (3–4 wt.% CoO), and was employed for the skies. An even finer smalt, around 7–11 microns, is present as a complement to the other blues, a copper-based blue and indigo. This last and third type could be smalt ground at the workshop.

The elemental analysis of the samples allowed an understanding of the alterations smalt has undergone in these paintings, linked with the leaching of potassium from the glass structure. The smalt that was mixed with lead white is in a better state of conservation, as it is less faded than the smalt in samples with less lead. Undoubtedly, Villalpando’s blue hues were much brighter in his time; nevertheless, the high potassium content found in the smalt samples reflects that the paintings are in a relatively good state of conservation. Arroyo Lemus and Amador Marrero (2017) report that it is common to find degraded smalt in novohispano paintings dating from the end of the sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth century. According to the authors, this type of fading is common in paintings from the workshops of Cristóbal de Villalpando and Nicolás Rodríguez Juárez (Arroyo Lemus and Amador Marrero 2017, pp. 232–33). In their SEM-EDX study dedicated to the work by Juan Correa, Arroyo Lemus and Amador Marrero found that the smalt was a cobalt potash glass. Similar to Villalpando’s cross-sections, the researchers also found that in areas where smalt was mixed with lead white, particles were less degraded, while faded particles of smalt had low potassium content (Arroyo Lemus and Amador Marrero 2017, p. 232). Nevertheless, the smalt used by Correa did not have arsenic nor lead, which suggests that Villalpando’s smalt was specific to his shop.

The constant presence of lead in the particles of smalt is also significant, and it could be derived from the white lead matrix they are in (See Figure 9). Lead reacts with the oil medium and protects potassium from leaching, which reduces its fading (Spring et al. 2005, p. 61). The presence of lead could explain the persistence of high concentrations of potassium in Villalpando’s smalt. However, the high concentration of lead along with the absence of calcium raises new questions worth investigating in the future. It could be possible that a lead-based flux was used. Lutzenberger et al. (2010, p. 369) found lead and potassium-rich glasses in German paintings from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.17 Antonio Neri (1612, p. 62), in his treaty, L’Arte Vetraria distinta in libri sette, describes the lead glass manufacture using calcinated lead mixed with “fritta di cristallo.”18 The Italian glassmaker specifies that to make a blue lead glass, the mixture had to be heated and then washed to finally add zaffre and prepare the glass (Neri 1612, p. 63). By 1662, lead glass became standardized and patented in England (Kurkjian and Prindle 1988, p. 798).19 Considering the date of Villalpando’s paintings, there is a possibility that the smalt used contained lead.

The discussion of the experiment’s results should also be framed by the geopolitical situation of the Hispanic monarchy. Among the products that the American continent provided to the monarchical economy, two blue pigments stand out: indigo and azurite from Santo Domingo. Indigo was used since pre-Hispanic times, and its use in European paintings consolidates throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, becoming—alongside cochineal—one of the crown’s most valuable products. The azurite from Santo Domingo was already mentioned in the second trip by Cristóbal Colón, and it was usually transported to Sevilla to be refined. Bruquetas (2007, pp. 147–57) reports that by 1700 the exploitation of the mines of Santo Domingo stopped and azurite became scarce and hard to acquire. While there are no archival sources yet that show evidence of the trade of this azurite to New Spain, the pigment becomes less frequent in eighteenth-century paintings. As the two paintings by Villalpando clearly illustrate, this situation led the painters of New Spain to take advantage of the local materials, like indigo, as well as a cheaper and more accessible blue: smalt. In addition to the innovations that can be recognized in Villalpando’s technique, he is not completely disconnected from the technical tradition of his predecessors. The mixture of a copper blue with indigo strongly resonates with the strokes by José Juárez in El Martirio de San Lorenzo, studied by Falcón and Vázquez (2002, p. 291), which demonstrates the coexistence of continuities, ruptures, and innovations in the making of a local painting tradition.

The history of blue smalt has been strongly linked to the production of glass and ceramic enamels since antiquity, but its use as a pigment in painting is more recent, the earliest case being from the fifteenth century (Spring 2017, p. 5).20 At that moment in time, the main producer of smalt was Venice, but as glass artisans made their way into Flanders, the Venetian techniques spread in northern Europe (Seccaroni and Haldi 2016, p. 188). Throughout the seventeenth century, Saxony was the main provider of cobalt ore, used in smalt production in Europe.21 The increase in production and commerce of smalt was reflected in its increasing use in oil painting.

There are only a few sources about the import of pigments to New Spain, however, the presence of smalt in shipments from Seville to the Indies is well documented as early as 1586 (Sánchez and Quiñones 2009, p. 62). Espinosa Pesqueira and Arroyo Lemus (2014) found smalt even earlier in a painting by Simón Pereyns, La Virgen del Perdón from 1568. While Sánchez and Quiñones (2009) do not mention the provenance of the blue smalt in the documents that they study, there are sources that report that smalt used to be imported from Flanders and Murano to Spain (Bruquetas and Presa 1997, p. 170), which could potentially give clues about the origin of the painting materials sent to New Spain.

Before concluding, it is important to open some research pathways that so far have not been explored in scholarly work. Despite that the ordinances mandated that the painters and gilders of Mexico City employed colors from Castille, it is hard to ignore that painters could have used local materials making use of the local glass and ceramic production. The first glass-makers arrived in New Spain in the sixteenth century and even though there is no record that a gremio—guild—existed to date, Peralta Rodríguez (2018, p. 5) reports that there was a “Maestro Mayor”—Master Craftsman—of glass and fine pottery appointed in the city of Puebla.22 Martins Torres (2019) notes that in Puebla there was a production of “vidrio de tres suertes: blanco cristaleño y verde y azul” (245).23 In terms of the materials used in making the glass, Castillo Cárdenas (2020) argues that glassmakers had to adapt their practices to the local materials, substituting the Iberic with endemic plants rich in sodium, like the “barrilla.”24 During the seventeenth century, artisans started using a sodium salt called “tequesquite” (Castillo Cárdenas 2020). The absence of sodium in the smalt used by Villalpando pushes us away from the possibility that these sodium-rich glasses were used by the painter; however, the link between the local glass-making practices and painting materials should be investigated further. This would also include the expensive “polvos azules” (blue powders) used as a raw material for the production of the cobalt blue glazed ceramic known as “talavera poblana.”25 As Peralta Rodríguez (2018) points out, the closeness between glass-makers and pottery artisans was not only physical but also in the use of similar materials and technologies; such is the case of the “polvos azules” to which artisans had access and that could have been employed to make painting materials.

5. Conclusions

It is certainly difficult to extrapolate the findings presented here to Cristóbal de Villalpando’s entire body of work, however, this analysis adds to the results reported by Arroyo Lemus (2017), Mahon et al. (2019), and Lazarte Luna et al. (2018) to start developing a more robust body of research around Villalpando’s painting technique. Villalpando’s mastery use of lakes to play with the transparencies of layers to depict garments comes across in El Triunfo de la Iglesia as well as in the Adoration of the Magi (Mahon et al. 2019; Lazarte Luna et al. 2018). This also includes the use of “semi-transparent yellow glazes” (Arroyo Lemus 2017; Mahon et al. 2019, p. 118) to module tones. Another commonality between the paintings studied here and the Adoration of the Magi is the good state of conservation of the paintings, which reflects the painters’ deep knowledge of the oil medium and the high quality standards of the guild by the seventeenth century.

This study contributes evidence to start pondering the protagonist role of blue smalt in the artistic practices developed in New Spain at the turn of the eighteenth century, before the invention of Prussian blue. The way painters transitioned from the use of blue smalt and indigo to the inclusion of Prussian blue in their palette is still something that needs further research.

In addition, this study sheds light on the technological formulations developed ex profeso to optimize the application of smalt and acquire pictorial qualities that responded to the artistic intentionality and the taste of the commissioners. In this regard, it is worth mentioning the ongoing contributions made by different research groups who through historical reconstructions are revealing that smalt—as well as ground glass—not only provided color but also improved the plasticity and translucency of the paint (see Hermens (2020)). It is necessary to expand the study of primary sources concerning the trade of smalt to New Spain, as well as the origin and typology of the materials. Furthermore, it is key to continue researching the possible use of local materials derived from the glass and glazed pottery production in New Spain.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to this article’s conceptualization, methodology, investigation, resources, data curation, writing, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The studies performed at the Laboratorio de Análisis y Diagnóstico del Patrimonio (LADIPA-COLMICH) were funded by CONACYT, Apoyos para Adquisición y Mantenimiento de Infraestructura en Instituciones y Laboratorios de Investigación Especializada, 2019, Proyecto 300178 “Fortalecimiento de capacidades tecnológicas para el estudio interdisciplinario, el diagnóstico y la conservación del patrimonio cultural mexicano.”

Data Availability Statement

Data regarding this research are archived at LADiPA-COLMICH.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Adriana Cruz Lara Silva and Arturo Camacho Becerra for the opportunity to study these paintings within the project of cataloging the Museo Regional of Guadalajara’s painting collection. We extend our gratitude to Esteban Sánchez for performing the SEM-EDX analysis; to Francisco Mederos Henry for his advice; and Gerardo Hernández Rosales for the photographs of the paintings. The reproduction of the paintings was authorized by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. The microscope and SEM-EDX images were used with permission of LADiPA-COLMICH.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Arroyo Lemus, Elsa. 2017. Transparencias y fantasmagorías: La técnica de Cristóbal de Villalpando en La Transfiguración. Addendum to the exhibition catalogue. In Cristóbal de Villalpando, Pintor Mexicano del Barroco. Mexico City: Fomento Cultural Banamex, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Arroyo Lemus, Elsa, Manuel E. Espinoza, Tatiana Falcón, and Eumelia Hernández. 2012. Variaciones celestes para pintar el manto de la Virgen. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 100: 85–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Lemus, Elsa, and Pablo Amador Marrero. 2017. Aproximación a los materiales y las técnicas del pintor Juan Correa. In Juan Correa. Su vida y su obra. Tomo I. Edited by Elisa Vargaslugo. coordinated by Pedro Ángeles Jiménez and Cecilia Gutiérrez Arriola. México City: UNAM-IIE, pp. 205–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bruquetas, Rocío. 2007. Azul fino de pintores: Obtención, comercio, y uso de la azurita en la pintura española. In ‘In Sapientia Libertas,’ Escritos en Homenaje al Profesor Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez. Madrid-Sevilla: Museo Nacional del Prado, pp. 148–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bruquetas, Rocío, and Marta Presa. 1997. Estudio de algunos materiales pictóricos utilizados por Zuccaro en las obras de San Lorenzo de El Escorial. Archivo Español del Arte LXX 278: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas Pérez Benítez, Mari Carmen. 1999. Técnica pictórica por Cristóbal de Villalpando en la cúpula de la Capilla de los Reyes. In La Catedral de Puebla en el Arte y en la Historia. Edited by Montserrat Galí Boadella. Mexico D.F.: Secretaría de Cultura, Gobierno del Estado de Puebla, Arzobispado de Puebla, Instituto de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades- BUAP, pp. 255–61. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda Delgado, María. 2017. Caracterización e Identificación del Índigo Utilizado Como Pigmento en la Pintura de Caballete Novohispana. Bachelor thesis, Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente, Guadalajara, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo Cárdenas, Karime. 2020. Glass Production in Colonial Mexico: Technology Transfer, Adoption, and Adaptation. Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina, Leonor. 2002. Polvos azules de Oriente. Artes de México 3: 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- de la Maza, Francisco. 1964. El pintor Cristóbal de Villalpando. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa Pesqueira, Manuel E., and Elsa Arroyo Lemus. 2014. The Use of Smalt in Simon Pereyns Panel Paintings: Intentional Use and Color Changes. MRS Online Proceeding Library Archive 1618: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiana, Falcón, and Javier Vázquez. 2002. José Juárez: La técnica del pintor. In Recursos y discursos del arte de pintar. Edited by Nelly Sigaut. Mexico D.F.: El Colegio de Michoacán-El Museo Nacional de Arte, pp. 286–306. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Marisa, Ruth Chércoles, and Margarita San Andrés. 2012. Los azules de cobalto. In Fatto d’Archimia Los Pigmentos Artificiales en Las Técnicas Pictóricas. Coordinated by Celia Diego, María Domingo and Iolanda Muiña. Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, pp. 273–91. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Haces, Juana, Pedro Ángeles, Clara Bargellini, and Rogelio Ruiz Gomar. 1997. Cristóbal de Villalpando, ca. 1649–1714: Catálogo Razonado. Mexico D.F.: Fomento Cultural Banamex, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans, Kevin, Anke Vincke, Simone Cagno, Davy Herremans, Wim De Clercq, and Koen H. Janssens. 2014. Composition and state of alteration of 18th-century glass finds found at a Cistercian nunnery of Clairefontaine, Belgium. Journal of Archeological Science 47: 121–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, Erma. 2020. I3GlasP-Imaging, Identification and Interpretation of Glass in Paint. Paper presented at Online Conference at NICAS Project Week, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, November 30. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, Aaron M. 2017. Inventing Painting: Cristóbal de Villalpando, Juan Correa, and New Spain’s Transatlantic Canon. The Art Bulletin 99: 102–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, Koen H., Geert Van Der Snickt, Matthias Alfeld, Petria Noble, Annelies van Loon, John K. Delaney, Damon M. Conover, Jason G. Zeibel, and Joris Dik. 2016. Rembrandt’s ‘Saul and David’ (c. 1652): Use of multiple types of smalt evidenced by means of non-destructive imaging. Microchemical Journal 126: 515–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurkjian, Charles R., and William R. Prindle. 1988. Perspectives on the History of Glass Composition. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 81: 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarte Luna, José Luis, Dorothy Mahon, Silvia A. Centeno, Federico Carò, and Louisa Smieska. 2018. Old World, new World: Painting Practices in the Reformed 1686 Painter’s Guild of Mexico City. AIC Paintings Specialty Group Potsprints 31: 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lutzenberger, Karin, Heike Stege, and Cornelia Tilenschi. 2010. A note on glass and silica in oil paintings from the 15th to the 17th century. Journal of Cultural Heritage 11: 365–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, Dorothy, Silvia A. Centeno, Federico Carò, and Louisa Smieska. 2019. Cristóbal de Villalpando’s Adoration of the Magi: A discussion of Artist Thecnique. Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 1: 113–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Torres, Carla Andreia. 2019. Lo Que Cuenta un Abalorio: Reflejos de unas Cuentas de Vidrio en la Nueva España. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mues Orts, Paula. 2008. La Libertad del Pincel: Los Discursos Sobre la Nobleza de la Pintura en Nueva España. Mexico D.F.: Universidad Iberoamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, Antonio. 1612. L’arte Vetraria distinta In Libri Sette. Florence: Stamperia de Giunti. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Francisco. 1990. El arte de la Pintura. Madrid: Cátedra. First published 1649. [Google Scholar]

- Palomino de Castro y Velasco, Antonio. 1944. El Museo Pictórico y Escala Óptica, Tomo Segundo. Buenos Aires: Poseidón. First published 1715. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta Rodríguez, José Roberto. 2018. Materia prima, hornos y utillaje en la producción de vidrio de la ciudad de México, siglo XVIII. Estudios de Historia Novohispana 58: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, Manuel. 1893. El arte en México Durante la Época Antigua y el Gobierno Virreinal. Mexico: Oficina Tipográfica de la Secretaría de Fomento. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez González, Andrea. 2015. La Restauración de la Pinacoteca Virreinal del Museo Regional de Guadalajara durante el Proyecto de Reestructuración 1973–1976. Principios, Criterios y Técnicas de Intervención en la Pintura Sobre Lienzo. Bachelor thesis, Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente, Guadalajara, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, José María, and María Dolores Quiñones. 2009. Materiales pictóricos enviados a América en el siglo XVI. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 95: 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seccaroni, Claudio, and Jean Pierre Haldi. 2016. Cobalto, Zaffera, Smalto Dall’antichità al XVIII Secolo. Roma: ENEA. [Google Scholar]

- Sigaut, Nelly. 1989. Una tradición plástica novohispana. In Lenguaje y Tradición en México. Edited by Herón Pérez Martínez. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, pp. 315–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spring, Marika. 2017. New Insights into the materials of the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Netherlandish paintings in the National Gallery, London. Heritage Science 5: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, Marika, Catherine Higgitt, and David Saunders. 2005. Investigation of Pigment-Medium Interaction Processes in Oil Paint containing Degraded Smalt. National Gallery Technical Bulletin 26: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Steigenberger, Gundel, and Christoph Herm. 2016. Investigation of colored lead glass glitter from an early eighteenth-century material collection, Cambridge, by electron microscopy/energy dispersive X-ray analysis. Heritage Science 4: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, Manuel. 1982. Pintura Colonial en México. México: UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, Agustín F. 1919. Breves Apuntes Sobre la Antigua Escuela de Pintura en México y Algo Sobre la Escultura. Mexico D.F.: Talleres Gráficos Don Quijote. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | While scholars have not located Villalpando’s baptismal records yet, this date of birth is well accepted in the academic community. Villalpando’s earliest works are the paintings of the retablo of San Martín de Tours, in Huaquechula, dated around 1675, which does not mean he did not start earlier his artistic production. |

| 2 | Schelte Adamsz Bolswert (printmaker) after Peter Paul Rubens, Hemelvaart van Maria met apostelen (1596–1659), print on paper, 623 × 440 mm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. |

| 3 | Peter Paul Rubens, El Triunfo de la Iglesia (1625), oil on canvas, 63.5 × 105 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid. The painting by Rubens is a sketch for a series of monumental tapestries commissioned by Infanta Isabel Clara Eugenia for the order of the Descalzas Reales of Madrid (Sigaut 1989, p. 341). |

| 4 | Baltasar de Echave y Rioja, El Triunfo de la Iglesia (1675), oil on canvas, Cathedral of Puebla, Puebla. |

| 5 | The wax–resin relining, also known as the Dutch method, consists of impregnating the painting from the back with a mixture of beeswax and resin (colophony or dammar). Through controlled heat and pressure, the mixture penetrates the pictorial layer, consolidating it, while another canvas support is added to back the original. |

| 6 | Villalpando’s mural painting technique has been studied by Casas Pérez Benítez (1999, pp. 255–61) through her research on the vault of the Capilla de los Reyes at the Cathedral of Puebla, Puebla, Mexico. |

| 7 | Through SEM-EDX analysis it was determined that this pigment is composed of copper. Additionally, the FT-IR analysis of the layer confirmed the presence of a carbonate, however, the round morphology of the particles raises the question of whether the pigment is mineral azurite or synthetic. |

| 8 | Francisco Pacheco ([1649] 1990) indicates the use of “aceite graso de azarcón” for the lakes and for “jalde” (orpiment). The oil was prepared by mixing linseed oil with ground minium. |

| 9 | Characteristic absorption bands of indigo blue were identified at 3266, 1674, 1202, 1184, 1180, 1172, 1078, 886, 854, 754, and 696 cm−1; however, the impregnation of wax–resin and the reduced thickness of the layer generated a lot of noise in the spectra; therefore, the analysis was inconclusive. |

| 10 | Nickel was not identified in any of the samples, thus, the use of smaltite as the mineral of origin was discarded. |

| 11 | A low concentration of sodium was only identified in one of the particles, and for this reason, it was disregarded as part of the composition of the smalt. |

| 12 | Translation by authors: “the most delicate and difficult color to use and that dies for many good painters.” |

| 13 | Translation by authors: “The blues can be worked from different colors: the most common is smalt, which is worked with some indigo, so it becomes more robust and covers well the canvas, with no more mixture other than white (…) and once it is dry, it is worked only with fine smalt and white.” |

| 14 | Translation by authors: “saturating the dark [blues] with indigo.” |

| 15 | While it is important to note that Villalpando could have used different oil binders for the blue color, as Palomino de Castro y Velasco ([1715] 1944) suggests, this research question could not be addressed in this study due to the wax–resin lining both paintings underwent, which limited binding media identification. |

| 16 | Translation by authors: “if all of the smalt is used re-ground, it turns black with time.” |

| 17 | The glass found in these paintings had the function of improving the drying properties of paints and was added as an extender. Lutzenberger et al. (2010) conclude that the painters used local cullet as an additive to oil paint. In contrast to the smalt used by Villalpando in the two paintings in this study, the lead-rich glass found reported by Lutzenberger et al. (2010) had a very high calcium content. |

| 18 | The “fritta di cristallo” was obtained calcinating a stone rich in quartz, which Neri describes as “Tarso,” with ashes from Levante (“polverino”). While Neri describes with detail the making of lead glass, he also references the blue smalt that painters used as an independent material; thus, it is hard to affirm whether or not lead glass was used to paint. |

| 19 | British lead glass (flint glass) has high contents of lead (between 12 and 40 wt.% PbO) (Steigenberger and Herm 2016; Kurkjian and Prindle 1988; Hellemans et al. 2014) in comparison with the content found in Villalpando’s paintings. |

| 20 | Dirk Bouts. The Entombment (ca. 1450), glue-sized painting on linen, 90 × 74 cm, National Gallery, London. Seccaroni and Haldi (2016, p. 93) recognize that it was only between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries when the extraction of cobalt became independent from the extraction of silver. It was during this period when the cobalt ores started to be more known, and cobalt stopped being a subproduct of discarded materials. |

| 21 | Saxony started to properly produce smalt until 1635, but it continued to be the main cobalt ore mine for the rest of Europe (Seccaroni and Haldi 2016, p. 216). |

| 22 | There are no records of a similar appointment happening in Mexico City according to Peralta Rodríguez (2018). |

| 23 | Translation by authors: glass of three kinds: “crystal-like white and green and blue.” Letter sent by the “procurador” of Puebla, Don Gonzalo Diaz Vargas, to the emperor ca. 1547. Cited by Martins Torres (2019, p. 245). |

| 24 | Peralta Rodríguez (2018, p. 7) also notes that local glassmakers experimented with wood ashes from pine and poplar like the glassmakers in northern Europe. |

| 25 | In the 1682 ordinances of pottery artisans, the quality that artisans had to use was specified, which they protested, claiming that the “polvos azules” (blue powders) were very expensive and could not be spent on cheap pottery (Cortina 2002, p. 48). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).