Abstract

Despite the plethora of digital and technological advances made in the construction industry over the past three decades, at its core, the sector remains human-centric. Consequently, this research investigates the core soft skills employed on public linear infrastructure (PLI) projects (during the construction phase) that are digitally enabled and concludes with the development of a decision support tool for PLI project team management. A mixed philosophical stance is implemented using interpretivism, postpositivism and grounded theory together with abductive reasoning to examine subject matter experts’ perceptions of the phenomena under investigation. Textual analysis is then utilised to formulate a decision support tool as a theoretical construct. The research findings demonstrate that communication, leadership and creativity/curiosity are the three main soft skills required of PLI projects. Furthermore, the key elements of a decision support tool—namely, trackable and measurable data, clear objectives and success criteria, and an easy-to-understand visual format—were identified. Such knowledge provides a strong base for building an emotionally intelligent project team. This research constitutes the first attempt to understand the essential soft skills required on PLI projects and, premised upon this, generate a decision support tool for project management in teams that helps to augment project performance through workforce investment via a learning organisation.

1. Introduction

Regardless of the noteworthy marketing, development, and implementation of automation and digitalisation, the construction industry relies upon the innate skills and competencies of people. Specifically, a person’s technical and interpersonal skills are essential for the successful delivery of projects within industry [1]. Current figures from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) indicate that there are approximately 1.44 million people working within the United Kingdom (UK) construction industry [2], and of these, 13.35% (or 192,300) are engaged within a civil engineering or public linear infrastructure (PLI) specialty [2]. The UK Government’s Construction 2025 Strategy (originally published in July of 2013 and not updated since) strongly promotes, advocates and prioritises a digital and technology-driven industry as a means of engendering higher productivity performance [3]. However, an undercurrent theme throughout the report denotes a more humanistic basis, as illustrated by “people” and “leadership” constituting two of the five headings for the strategy’s vision [3]. Therefore, the importance of human skills within the construction industry is inextricably linked to both current and future economic prosperity.

PLI projects are publicly funded/utilised projects that run horizontally over long distances and are essential for a modern society to function (e.g., highways, roads, railway, utilities and bridges) [4,5,6]. UK PLI projects account for approximately GBP 20.67 billion in construction output value or around 10.03% of the total construction output value [2]. Although at face value these projects appear similar to commercial construction projects, they are inherently different due to their complex inter-organisational nature [7], which embraces a plethora of stakeholders (e.g., clients, main contractors and the public) with differing values and priorities [8]. Furthermore, PLI projects are large and complex with substantial budgets, far-spanning construction sites, unique time constraints and numerous management staff responsible for overseeing these projects’ completion [9]. Exceptional soft skills are therefore quintessentially important to ensuring the smooth running of the project given that advanced digital innovations are not sentient and cannot yet build infrastructure without human intervention.

Against this prevailing mise en scène, this present research explores what soft skills are required of professionals working on digitally enabled PLI projects during the construction phase. Specifically, a comparison of academic and professional opinion is made to determine the most valuable soft skills required when working on PLI projects. New emergent knowledge engendered the development of a decision support tool that can identify soft skill gaps or priorities for employee recruitment and project team selection. Concomitant objectives seek to systematically analyse secondary data to gain an insight into the prevailing discourse of established academics on soft skills; collect primary survey data through research instruments to compare and contrast current practitioner views with academic opinion to draw reliable conclusions about the phenomena under investigation; and synthesise the primary and secondary data collected to identify the key features a decision support tool requires to enable success in PLI projects.

2. Soft Skills in Construction: A Literature Review

Historically, a dichotomy exists in the literature encompassing soft and hard skills, and within these thematic groups, there is a divergence in opinion as to what are the most important skills across multiple industries and sectors [10]. Given the myriad job roles, this vibrant discourse (and finer nuances within it) is unsurprising. However, sources adding to the cacophony of opinions are varied and include debates on which skills are more predominant within job advertisements [11]; more beneficial for personal safety management [12]; and more important in higher education institutions [13]. In 2003, the UK Government set out a plan for the future of higher education that was committed to increasing diversity, funding and accessibility for universities [14]. As accessibility to education has increased, so has the number of skilled graduates—in 2002, approximately 24% of the population were classed as graduates, which steadily rose to around 42% in 2017 [15]. Generally, the more saturated the market becomes, the greater the competition for highly skilled jobs [16]. This in turn stimulates employers to ratchet up standards for recruitment, changing soft skills from what once was a ‘nice to have’ to a higher priority to differentiate between the quality of candidates [17]. This increased demand and recognition of soft skills has also been exhibited across the supply chain [18]. However, the acknowledgment that soft skills in practice are fundamental to business success is not unanimous. For example, Grugulis and Vincent [19] favour technical skills in their case studies. Nonetheless, many publications [20,21,22] take a central stance, agreeing that both soft and technical are necessary (albeit to differing degrees).

Technical skills are defined as specific job-related abilities (such as estimating, machine operation or coding) that are often associated with qualifications [23] and are traditionally taught through higher education courses and workplace training. However, soft skills are linked throughout the literature to inherent personality traits [24] and are therefore not as straightforward to learn [25]. The inherent difficulty of gaining more soft skills through traditional education may be contributing to the noticeable increase in their importance to employers. Technical skills are ubiquitously taught, relatively easy to acquire, and thus generally less valuable. This is a representation of basic supply and demand theory [26]. Souza and Debs [27] argue that, regardless of preference towards soft or technical skill requirements, the advent of Industry 4.0 (cf. Newman et al. [28]) requires far greater focus on reskilling and upskilling to meet changing demands for a more digitally enabled workplace.

Previous research has focused on data collection methods such as reviewing job advertisements [10,29,30] or mass questionnaires—some of which require the participant to rank skills listed [1,31,32]. Answers given in structured questionnaires can leave contextual gaps and a lack of understanding of the reasoning for the answer, as low-quality responses limit data interpretation and the usefulness of the resultant findings [33]. For this reason, semi-structured interviews present a useful opportunity to delve deeper into questions posed to not only numerate responses (often on a Likert or ranking scale) but also determine why such ratings were given.

2.1. Soft Skills and Institutions

When contemplating what are perceived to be the most important soft skills in industry, it is beneficial to consider world-leading professional industry bodies because they champion the interests of that community they represent [34]. A non-exhaustive list of organisations which promote technical and interpersonal competence standards to its members include the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS); the International Project Management Association (IPMA); the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB); and the Project Management Institute (PMI).

2.1.1. Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors

The RICS has mandatory competencies that every professional, regardless of pathway, must demonstrate to become a chartered member [35]. The RICS candidate guide states that competencies covered by their standards are not directly labelled as soft skills but rather include ethics, rules of conduct and professionalism; client care; communication and negotiation; and conflict avoidance, management and dispute resolution procedures [36]. This is comparatively a small number of skills when considering (depending on pathway) that there up to sixteen more required technical competencies in each respective candidate guide and that each soft skill could be broken down further for finer nuance [35]. Aside from this, there are scant available reference documents or “best practice” guidance on soft skills. However, there is a continued professional development (CPD) course labelled “Interpersonal Excellence” offered for a fee. This course encompasses three pillars of interpersonal excellence, viz., public speaking, communication and leadership [37]. Clearly, the RICS recognises the importance of core soft skills but in the context of managing client relationships rather than within the organisations themselves. Other research studies (cf. Posillico et al. [38]) also support the notion that professional institutions place a heavier emphasis on technical competence.

2.1.2. The Project Management Institute

The Project Management Institute (PMI) has developed and promoted the “Talent Triangle” infographic as part of its learning and competency development [39]. Within this triangle, “power skills” is listed as one of the foundational pillars. The PMI defines power skills as “behaviours that enable people to succeed” and are listed as active listening; communication; conflict management; emotional intelligence; empathy; negotiation; problem solving; and teamwork [40]. These skills are in congruence with the initial literature overview but do not encompass certain skills which are deemed important by alternate literature (such as assertiveness and reliability [41]). Technical competence is still portrayed as essential through the “ways of working” and “business acumen” requirement pillars, but a heavy emphasis is placed on soft skills and they are directly linked to project success. This understanding is significant as the framework is used for educational practices; therefore, PMI-trained professionals consider soft skills as essential for project success. Moreover, the PMI has multiple blog and article posts about soft skills development through their “learning library” [42]. Evidently, the PMI and RICS concur that some generic soft skills are essential—particularly communication, management and leadership. However, what other skills are essential, and to what extent, appears dependent upon the specific organisation, project and client requirements [43].

2.2. Soft Skills in Project Teams

Project managers are the authority and hold the lion’s share of responsibility on a project [44] because they manage the complex interactions between different stakeholders and tasks. Consequently, many project managers focus upon the general oversight of a project and are purposefully removed from the intricate, technical elements of specific tasks [45]. This is not to infer that project managers are not technically minded, but rather, the profession places emphasis on managing the teams/contractors with the intricate, technical knowledge/training of a specific scope of work. Therefore, project success hinges upon the innate capabilities of individuals within a project management team because they determine the quality of work created. Defining and delineating what constitutes a successful project are different for each project manager, stakeholder and team—for example, Dvir and Lechler [46] proffered that project success is a mixture of efficiency and client satisfaction. Pinto and Selvin [47] devised a model delineating the ten factors essential to implementing a successful project, viz., a clear project mission; management support; a project schedule; client consultation; personnel; technical tasks; client acceptance; monitoring and feedback; communication; and troubleshooting. Some of these success factors are soft skills such as communication and client consultation. Others are intrinsically linked to and supported by soft skills, such as troubleshooting or monitoring, and feedback, which is associated with critical thinking and problem solving. Following this logic, soft skills subsequently support and enable project success in construction.

“Teamwork” per se is a soft skill [48] and efficient teams are supported by them. Yang et al. [49] found that teamwork is positively related to project performance and has a “statistically significant influence” on project success. Additionally, a study by Zhou et al. [50] aimed to reveal areas for career development for architects, conferring directly with employers who identified soft skills (including teamwork) as the most desirable traits. Reinforcing the notion that in times of employment over-saturation, the construction industry seeks to differentiate using soft skills [17]. In congruence, Kissi et al. [51] determined that in order to be successful in a digitised era, project managers require leadership and interpersonal skills—emphasising the codependent relationship between project success and soft skills.

However, not every individual can exhibit every soft skill; it is unreasonable to expect such. Therefore, when constructing a team that possess a blend of skills, it is beneficial to determine which soft skills are required and in what capacity to ensure every team can meet all objectives set. This is the novelty of the present research study.

2.3. Key Soft Skills for Project Success in Construction

Through the synthesis of the literature, six core soft skills were correlated with enabling project success in construction project environments—see Table 1. Due to the lack of PLI-specific research on soft skills, studies focusing on construction holistically were reviewed to identify the core skills. The primary data collection was then utilised to determine whether the skills identified in the literature are applicable to PLI projects.

Table 1.

The soft skills found in the literature to enable project success in construction.

3. Materials and Methods

This research adopts a mixed philosophical design (using interpretivism, postpositivism and grounded theory (cf. Bayramova et al. [59]) and abductive reasoning to examine industry subject matter experts’ (SMEs’) perceptions of soft skills required on PLI projects, the purpose being to identify specific soft skills for incorporation into a conceptual “decision support tool” which allows teams to gain theoretical insight into potential avenues for candidate recruitment or optimal personnel selection based on the skills required for a task [60,61]. Specifically, interpretivism provided a contextual view of soft skills within PLI projects, postpositivism analysed the results from semi-structured interviews, and grounded theory provided the knowledge foundations for developing the decision support tool.

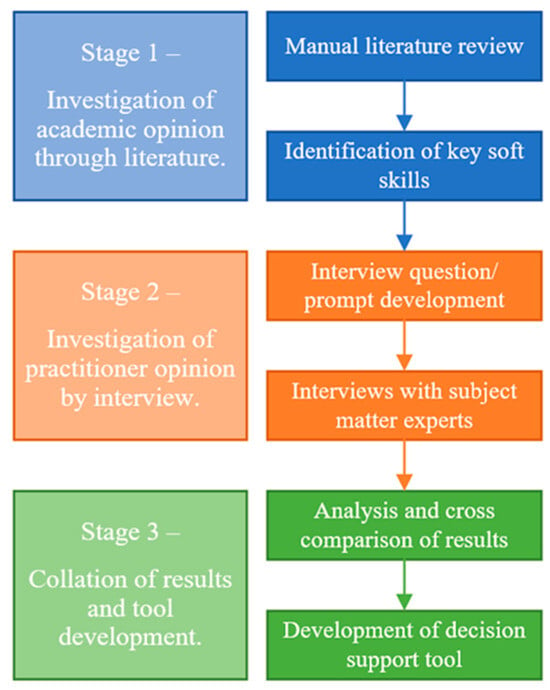

As a research approach, an iterative “cascade” process was implemented (refer to Figure 1). First, the key skills for the decision support tool were derived based on the literature findings. Second, the main interview questions/themes with supporting prompts were developed, also from the literature findings [62,63]. A semi-structured interview style was adopted because it gives the interviewer flexibility in posing different types of questions (open-ended and closed); discussing tangential exploration of topics of interest; and exploring opportunities for follow-up queries [64,65]. At this stage, interviews were conducted with eight SMEs (c.f. Tabone et al. [66]; Milford et al. [67]). Finally, through postpositivist and grounded theory lenses, the narratives from the interviews were analysed to further refine the conceptual model (made from the literature alone) and develop a final decision support tool informed by both the literature and practice [68,69].

Figure 1.

Research flow diagram.

3.1. Semi-Structured Interview

The interviews were conducted individually and via video/audio and transcripts recorded on Microsoft (MS) Teams. The semi-structured interview process utilised included predetermined questions sourced from the literature and the emergent findings from the previous research stages. Each question contained a cache of prompts at the interviewer’s disposal to ensure that answers to questions posed were full and complete. Moreover, each prompt included an associated tick box to ensure that answers received covered every respective point prior to moving to the next prompt if needed. Before recording the interview, the research aims, objectives, and key definitions were broadly discussed. This allowed the participant to gain background knowledge on the specific research topic but also afforded an opportunity to check for understanding. It also provided an opportunity for both parties (interviewer and participant) to work through various conversational norms (greetings, familiarisation with speech patterns, pace of speech, enunciation, etc.). Specifically, the semi-structured interview asked six main questions, viz.: (1) experience in professional education; (2) initial perceptions of the key skills as identified through the literature; (3) key skills’ applicability to PLI projects; (4) practicality of a decision support tool developed from the extant literature; (5) thoughts on the construct form of an ideal decision support tool; and (6) open-ended concluding thoughts. These questions were accompanied by 13 prompts that sought to ensure a full and rich answer to each question. The questions posed during the semi-structured interviews were purposely kept brief to allow for a free-flowing informal dialogue, which allowed the participants to open up to questions posed in a relaxed and friendly environment. Upon completion of the interviews, the corresponding transcripts were downloaded and reviewed for completeness. Any identifiable information was redacted and any transcription errors from the MS Teams application were rectified. Once a final transcript of the interview was formalised, it was analysed.

3.2. Data Saturation

The interview questions were developed to extract as much qualitative data from the experienced practitioners as practicable and garner a full, rich response [70]. A non-probability, purposive sample was specifically chosen to benefit from the expertise of the participants [71]. Furthermore, the entry criteria specified were limited to participants with ≥four years of experience in PLI projects and those with ≥four years of management experience (specifically, employment of workers). Therefore, only those with sufficient insightful knowledge could offer informed opinions and contribute to the study’s outcomes. During interviews, data saturation occurs when answers and themes begin to be repeated—this is a signal to start the data analysis [72]. Furthermore, according to Dibley [73], the saturation point can also be reached when the quality and quantity of data are sufficient. In combination with the participants’ extensive experience and the breadth and depth of questioning, saturation was achieved with a limited number of participants. This happened by the eighth interview, where, at this point, repetition in answers and themes was apparent enough to generate meaningful conclusions from the qualitative data collected.

3.3. Textual Analysis

Voyant Tools (an open-source “web-based” software program, available at: https://voyant-tools.org, accessed on 3 April 2025) was utilised to analyse the interview transcript narratives using word associations, word context and trends as network infographics [74]. Voyant Tools has been extensively used in various built environment publications as a robust textual analysis tool to visualise contemporary developments for a given phenomenon under investigation [75,76].

3.4. Grounded Theory Technique

As an abductive strategy, grounded theory allows for the development of theory from comprehensively analysed data [77]. It is an established research strategy and has been successfully used to explore the relationship between project managers’ competency and project complexity [78]; develop theory on the correlation between indoor built environments and occupant behaviour [79]; and study the performance of public-sector projects when consultancy is outsourced [80]. Given these past applications, its usage in this present research is justified. Once the results were textually analysed, grounded theory was used to develop the concept for the decision support tool, ensuring it embodied both data and the literature.

4. Results

The participants were selected based on years of experience in both management and PLI, with the latter being the most imperative. Table 2 identifies participants’ job roles and their years of experience—with an aggregate of 165 years of experience in the PLI sector and 116 years of management experience. This demonstrates that all participants are sufficiently experienced to comment on the phenomena under investigation.

Table 2.

Experience and roles of participants.

Qualitative data were analysed systematically to discern the general implications of the answers to allow the research themes to be informed by the content. These included “connectivity”, “communication”, “conflict avoidance”, and “leadership”.

4.1. Soft Skills in the Construction Industry

When presented with the literature review findings (i.e., the six soft skills intrinsically linked to project success), all participants agreed the listed skills were important—focusing heavily on “leadership”, “communication”, and “curiosity” in their answers. However, some participants also expressed different doubts about how well these skills are being practiced within industry. For example:

Participant A noted the following: “OK, I would definitely agree that all of those soft skills are particularly important and for different reasons. So, I would agree that those skills are highly needed in this industry. I think where there’s a discrepancy is probably how well those skills are executed.”

Participant D noted the following: “I would say that they are absolutely the essential ones. Communication being the first one that you identified most definitely and it’s something that I think not just our organisation, but all organisations can really work on… So, for me, what you’ve identified is exactly what we need to put into practice.”

When prompted if anything could be added to the list, participants suggested “resilience”, “collaboration”, “transparency”, and “tolerance” amongst others. Conversely, when asked what could be removed, some participants questioned the inclusion and importance of “conflict management”, suggesting that “negotiation” and other skills should be utilised before reaching the need for this.

Participant F noted the following: “Relationships is not on there and I think it’s, particularly in my role, really critical. For all of that stuff, really working collaboratively, yeah, that’s the umbrella term, isn’t it?”

Participant B noted the following: “The main thing for me is, is basically transparency and then to be honest with the communications... And then in terms of conflict management, I think that’s kind of a last resort.”

In addition to labelling important skills, the participants brought attention to the requirement for “overarching objectives” to connect employees and their skills together to enable them to perform optimally.

Participant C noted the following: “You’ll get a better outcome if you’re curious. Certainly, you need leadership. You need and direction and objectives, which are a little bit harder, but if you don’t get those objectives as to what you’re trying to achieve, then you also won’t do it. And also, the other skill that you need is to find mutual objectives.”

Participant H noted the following: “So, for example, some of the best people that I’ve worked for, the ones that allow you to feel comfortable, comfortable enough to speak freely and they create the right environment. Environment, I suppose, is potentially one word to it to include all that.”

Appendix A.1 depicts a summary of the answers to Question 2. Overall, emergent themes identified by the participants were a lack of utilisation of soft skills in practice, the importance of “leadership” and “communication”, and the need for “conflict avoidance” over “conflict management”. Multiple participants debated the trainability of soft skills, discussing different personality types and the need for diversity within skills—not a “one size fits all” approach.

4.2. Soft Skills in Public Linear Infrastructure

When asked if the soft skills found in the literature for construction apply to PLI, all participants responded positively and supportively. Most participants stated that the skills were important in all aspects of construction. Others replied that these skills were important regardless of industry. Two participants proposed examples of specific skills that are particularly useful in a PLI context:

Participant A noted the following: “I think particularly problem solving and where they were calling creativity and curiosity are very important to this industry.”

Participant E noted the following: “I’m fairly happy with the six because teamwork possibly lies within them. I think good teamwork is real is important, but whether that’s contained within these, or whether it needs its own separate thing—I’m fairly flexible.”

Appendix A.2 depicts a summary of the answers to Question 3. Overall, the common thread between all participants was that soft skills are important, with some participants stating that they are useful for all sectors. Some skills were suggested as being more useful for PLI, but this did not exclude them from also being useful for other industries, to a lesser extent. For example, the importance of “negotiation”, “conflict management”, and “stakeholder management” was emphasised—weaving a common theme of effective general management skills.

4.3. The Use of a Decision Support Tool

When asked if the introduction of a decision support tool relating to soft skills could be useful, all participants responded positively and supportively. Despite all reaching a consensus on the usefulness of a tool, the participants were split after this. Some participants proffered a more cautious approach, favouring to debate the logistical challenges of implementing such a tool:

Participant H noted the following: “I think it’s a difficult one to implement. So yeah, I suppose I am a bit sceptical really.”

Participant C noted the following: “Actually, being able to identify whether one part of that skill set is greater than another part of that skill set is quite tricky… I don’t know how you would pick off one versus any of the other soft skills.”

Some participants focused on the opportunities such a tool would provide for increasing efficiencies and identifying skill gaps:

Participant B noted the following: “Overall, as a public organisation, we got massive resource pressures… if we have more efficient teams in operations, that means we can achieve more with the same given number of resources.”

Participant F noted the following: “Absolutely, I think for me personally, it would be useful to understand if there are any skill gaps around those softer skills in the wider team. So, I think the decisions support tool will help to identify where there are any sort of training or skills gaps.”

Appendix A.3 depicts of the answers to Question 4. Ultimately, all participants agreed on the usefulness of a decision support tool despite some doubts being expressed about the format or metrics used for evaluation. The overarching theme within the responses culminates in the idea of the tool enabling both opportunities and threats. Participants expressed both enthusiasm for such a tool but also reservations about the implementation of it, which could be attributed to the difficulty of setting highly subjective skill selection criteria.

4.4. The Form of a Decision Support Tool

When questioned on the form a decision support tool should take, participants generally responded enthusiastically, subsequently debating the optimum format of the tool. Participants all suggested different formats for the tool, ranging from tables to Venn diagrams:

Participant A noted the following: “Venn diagrams. Yeah, it kind of resonates… because we’re not really talking about processes here.”

Participant B noted the following: “I mean MS forms, do metrics these days... from forms you can do Excel spreadsheet and from excel spreadsheet it can go to power BI dashboard.”

Participant E noted the following: “I’d say simplicity is really important in it. I’d like to see it using a generic piece of software or a generic, you know, PowerPoint or Excel… or an online link.”

Participant D noted the following: “So if you’ve all got the same view of what good looks like, then you can work back to figure out that kind of. Maybe like you say, process flow diagram.”

Despite the product differing visually, the needs described by all the participants share similarities, one theme being the need for the tool to be supported by tangible and measurable data to inform it:

Participant F noted the following: “I think it would be really helpful, but I think it needs to be clear. The format of it isn’t necessarily important, it’s those other issues that are probably quite critical. In terms of us being able to use it in a productive way. I think it definitely needs to be data driven.”

Participant D noted the following: “These for me are really tangible … What we tend to do is really kind of align things to a tried and tested measurement.”

A common thread between responses was the desire for the tool to be in an accessible format that was available to team members and not just managers. Most participants also felt the need for clear, defined objectives and success criteria to generate a more successful tool:

Participant B noted the following: “It’s easy to navigate and its very user friendly and it’s basically to encourage people to check everything.”

Participant D noted the following: “We’ve had the most success is defining what the problem is… then working back that sort of problem statement content.”

One participant discussed the potential limitations of the tool, implying it could stagnate personal skill growth if misused as a false panacea to training and development within the business. They suggested that a tool may dismiss issues with people and systems by offering training as a mitigation:

Participant A noted the following: “Is it about taking the onus away from the company to address issues and maybe putting it more on to staff to say, well, these people are having problems with, they need training, employees need training rather than dealing with the root of the problem, which might be systems or processes or other issues like that.”

Lastly, one participant expressed the need for a knowledge feedback loop to inform the tool’s progression and development:

Participant G noted the following: “Having a feedback loop when the outcome was different to what was intended. So it creates that no blame, you know, scenario for it. So it’s there to learn.”

Appendix A.4 summarises the answers to Question 5. All participants reaffirmed the usefulness of the tool by suggesting a plethora of potential formats for it to take. Despite this broad range of visualisations, there was a common intent to make an easily accessible tool for team members and managers, to use objective and trackable data, and to be development-oriented.

4.5. Presentation of the Decision Support Tool

Parallels can be drawn between the literature review findings and the primary data analysis; namely, both academics and practitioners broadly agree on the importance of soft skills for project success. The participants also responded positively to the skills found to be essential in the componential analysis of the literature, only increasing the emphasis on “curiosity” and decreasing it on “conflict management” for a PLI context. The work of Van Heerden [1] was consolidated by participants’ opinions who also noticed a link between soft skills and personality traits. Furthermore, both parties expressed some more cautionary opinions about soft skills, similar to Robles [25], who suggested they can be more difficult to teach and learn. This was echoed in the primary data collection as some participants felt that hyper-focusing on soft skills can encroach on teaching and appreciating diverse skill sets. Cumulatively, these findings provide the basis of the development of the decision support tool.

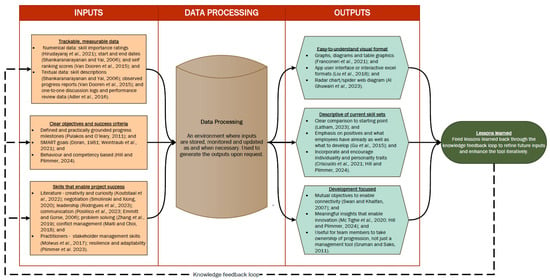

Key comments were synthesised and correlated with the literature to extrapolate the key criteria for the inputs and outputs required to make a tool that informs decisions around training, growth and development (refer to Figure 2). The graphic is structured in swim lanes and has four key segments—inputs, outputs, data processing and feeding lessons learned into a knowledge feedback loop.

Figure 2.

Key inputs and outputs for the decision support tool [20,38,53,54,55,57,58,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99].

4.5.1. Inputs

The skills established through the literature form the first requirement for the decision support tool; other proposals from the interviews are substantiated with secondary sources to further reinforce how this would make the decision support tool successful.

Trackable, Measurable Data

This requirement for trackable and measurable data can be split into examples of numerical and textual data. Numerical data can be generated by asking staff to rank themselves—or to be more objective, rank others in their team. One option would be a Likert scale [100] to create quantitative data which can be easily compared and analysed against both other employee’s ratings and the users as a format for gauging suitability for a specific job role. Van Dooren et al. [81] investigated performance management in the public sector and noted how self-assessment options present an inexpensive and unobtrusive data collection method; observation and progress reports performed by close-proximity managers also host these benefits. Similarly, employees could be tasked to share their opinions on the importance of particular skills for their job role—this ensures the decision support tool is kept in congruence with employees’ values and beliefs on what skills are key as they are the experts on the requirements of their role [82]. Contextual data such as yearly performance reviews and one-to-one discussions could be stored in the model’s database for easy access when making decisions—as noted by Adler et al. [83], performance ratings are insufficient enough by themselves to make informed decisions. Lastly, basic information such as skill descriptions and start/end dates for entries must be logged as good data maintenance and quality are key for decision making [84].

Clear Objectives and Success Criteria

Clear objectives and success criteria would be formulated by looking at job role criteria (cf. Posillico et al. [38,101]) to be functional and tailored to those in a multitude of roles. A commonly used concept in corporate settings is specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound (SMART) goals [85]. Weintraub et al. [86] recognised that defined goals help employees reach flow states, which means they benefit from reduced stress and fewer burnouts—happier, healthier employees will lead to more successful projects. In addition, SMART goals are simple to implement and can be generated independently, which makes them suitable for the decision support tool. This could be incorporated in the form of defined progress milestones that are short-term and grounded in day-to-day activities, thus addressing the disconnected nature of modern performance management tools, as identified by Pulakos and O’Leary [87]. Additionally, Hill and Plimmer’s [88] study of public-sector performance management systems theorised that a formal system should be based around skill development and competencies rather than singular task-based goals—this aligns closely with the opinions expressed by the interviewed practitioners.

Skills That Enable Project Success

The results of the primary research study (as justified by Table 1) represent some of the key skills for project success in PLI and would be the skills targeted by the decision support tool to track and monitor. These influential skills will have the largest impact in relation to strategic decisions being made and therefore the largest impact on project success factors. Participants suggested that resilience and adaptability are key for public-sector workers due to the complex and ambiguous project environments [89]. In addition, stakeholder management skills were identified as crucial for those working in PLI. The work of Molwus et al. [90] correlates this because in the UK, satisfying the various requirements of stakeholders is a key performance indicator and is commonly used to measure project success. Therefore, being able to manage stakeholders effectively can directly lead to a more successful project.

4.5.2. Data Processing

The data processing centre will act as a data repository for all inputs to be stored in until required to create the outputs. Moreover, this data repository would be kept up to date and would allow employees’ skills to be monitored and tracked. Upon request, an output can be generated that helps inform and make decisions about which team members are best for what tasks based on their current and developing skill sets.

4.5.3. Outputs

The outputs are a reinterpretation of the information provided from the inputs presented in a new graphical and textual format. These data can be condensed or amalgamated in the data processing centre for clarity, conciseness and ease of comparison. The purpose of the outputs is to rearrange the data provided on employees’ skills and objectives into an easy-to-understand format, which clearly describes their progress and (based on the content provided) offers advice and statistics which increase project success by virtue of informed decision making. For example, in the “senior project manager” role, it could be expected that leadership skills should be “well developed”. If this is not the case (based on the data from the inputs), users are notified that the team member is not suitable for this role yet.

Easy-to-Understand Visual Format

If the model was to advance from conceptual to physical, it could be presented as an interactive dashboard. Data are input via a form then stored and processed in the data processing centre, and graphs are presented for visual comparison and advice for decision making. Some suggestions for the graphical presentation formats included the radar chart (spider web diagram). This is also utilised by Van Heerden et al. [1]; it is a method of viewing multiple performance factors and is visually easy to compare to previous iterations, making it a viable output format in this context [91]. Tables and charts such as Venn diagrams have also been suggested. Using simple visuals presents benefits such as being accessible to users of all literacy levels and the ability to recognise trends, even for inexperienced users [92]. Furthermore, an MS Excel or dashboard application (app)-based interactive user interface would present these visuals in a familiar and intuitive format. Apps are widely used within the construction industry and represent a quick, affordable and user-friendly method of collecting, processing and displaying data [93]. Despite the suggestions being visually diverse, the formats are successful at simplifying the presentation of vast amounts of qualitative and quantitative data. These formats could host an informative, descriptive and development focused tool able to support decision making. The participants saw the benefits of such a tool for enhancing soft skills, linking to the work of Souza and Debs [27], who propose upskilling and reskilling as essential to meet industry’s changing demands.

Descriptive of Current Skill Sets

The decision support tool could be utilised to help mitigate the challenges in industry’s ever-changing skills climate, presenting a way for employees to increase the longevity of their skill sets via personal introspection and meaningful goal setting. Latham [94] identified that goals must be sufficiently challenging with consistent opportunities for feedback to ensure commitment and motivation from employees. The tool can be used at regular intervals over long periods of time to collect and store data. Subsequently, these entries can be compared to their predecessors to demonstrate progress and exhibit a clear comparison to the starting point—the first entry. Increasing accessibility to skill data and progress records supports employees in becoming proactive and taking ownership of their growth and development [102]. When considering the wording for describing skills, both by the employees and wording within the tool, the tone and approach should be positive. This is based on the responses and literature—there is a negligible difference in the reliability of self-assessments when presented with positive and negative wording [95]. When this is apparent, it is more appropriate to present the task positively to support employees’ engagement and morale [103]. Performance management is an inherent psychosocial process, which means sensitivity and emotional contextuality are required [88]. For this reason, it is important to incorporate and encourage individuality and personality traits; not only is it ethical as it protects employee’s mental health and self-confidence, but fostering diverse opinions, mindsets and skills reaps greater rewards. As explored by Criscuolo et al. [96], firms with more cultural and skill diversity had higher productivity levels.

Development-Focused

Moreover, as Breque et al. [104] and Posillico and Edwards [105] acknowledged, the advent of the “human-centric” approach of Industry 5.0 is upon us, further enforcing the use of a tool which develops soft skills which are less imitable by technological advances. Swan and Khalfan [97] explored how mutual objectives aided project teams on partnering projects in the UK construction industry. Similarly, the decision support tool could facilitate teams to align naturally by objective setting via job roles and mutual goals. Therefore, enabling connectivity across the organisation and ensuring decisions are being made concomitantly. Participants expressed a desire for any outputs to be meaningful in order to glean insights that enable innovation (which is not always prevalent in public-sector tools [88]). This function is enabled and supported by clear goals and an easy-to-use format as previously proposed. Collectively, these development-focused functions aim to make the tool accessible and intuitive to enable employees to take active ownership of their progression. Employees who are engaged can achieve higher levels of job performance [98] and, therefore, foster more successful projects.

4.5.4. Lessons Learned and Knowledge Feedback Loop

By collecting feedback from users and creating lessons learned, this can better inform the tool to facilitate the decision-making process in future activities. Feeding the lessons learned through the knowledge feedback loop to improve the outputs will iteratively improve the function over time. Moreover, this cyclical process would be enacted by users to encourage them to be active participants in the development and improvement cycle [99]. The process of experience, reflection and action closely aligns with Kolb’s [106] experiential learning cycle. Through observing and reflecting on the experience and whether it was a positive outcome, the inputs can be adjusted as necessary to ensure a more favourable outcome upon subsequent uses.

5. Discussion

This work presents numerous opportunities for practical application. First, the decision support tool itself is pragmatic, showing its potential to be used interchangeably between sectors as the outputs are modified based on the parameters defined. Companies may utilise this tool as a means of identifying opportunities for reskilling, personal development or identifying gaps in current skill sets. Over time, this could improve efficiencies and have a wider impact on project success as employees become more skilled, having a deeper and wider understanding of these talents. Second, using the tool sheds light on the skills required in a role for enabling project success, allowing for the recruitment of personnel with the optimum soft skills. Employees becoming more skilled through development and the recruitment of candidates with the optimal skills will make teams more agile and resilient to changing demands, which creates more opportunities for driving efficiencies. Third, the concepts behind the decision support tool’s key criteria resembles those used in education and curriculum development settings. Clearly defining the success criteria and key skills needed for job roles could have a practical application in apprenticeship course development—one of the many junctures between industry and education. Developing the findings into learning objectives and outcomes for training courses could create graduates whose skills are directly informed by business needs, closing the skills gap upon entry to new roles.

Ultimately, this study contributes to the prevailing body of knowledge by building upon the foundations set by others—from soft skills in construction [38] to the impact of soft skills on project success [49]. Although research was conducted on each topic independently, looking at PLI and soft skills though a combined lens illuminated how methods and theories applied in one aspect can yield new and novel results when applied in tandem. This was demonstrated by the participants broadly indicating that most of the soft skills found essential for general construction also apply specifically to PLI. The clear importance of soft skills in academia and practice has been made apparent [22], as well as the rift between this hypothetical understanding and the level of application in practice [10]. By exploring this further, the gap in the literature has begun to be remedied and a solid foundation to be built upon in future work has been provided.

The inherent nature of such a theoretical construct requires testing in practice (potentially as a case study) to understand the true effectiveness, which would also contribute to the validation of the data collection process. Furthermore, the data collection method is limited by sample size and the cross-sectional time horizon of the data, which only represents the views of the participants at the specific moment in time that the study was conducted.

A logical next step is to implement the tool for active testing and validation in practice. This will allow for verification on a larger sample size, as well as increasing the range of opinions and inputs informing the parameters. Additionally, an accompanying guidance document could be produced, giving instructions on the decision support tool’s use—increasing standardisation and the ease of use of the end users. Upon the completion of testing, amendments, modifications and refinement to the decision support tool can be implemented to identify the most optimum presentation format for the data.

6. Conclusions

The infrastructure industry is inextricably linked with the UK economy. To continue to sustain sector performance, successful projects completed with the ‘iron triangle’ constraints of time, cost and quality are crucial for necessary growth and development. Prioritising the skills of those responsible for project management in PLI will augment the likelihood of delivering successful projects due to the intrinsic link between soft skills and improved performance. Therefore, this will secure the current and future economic prosperity of the industry and national economy that depends upon infrastructure investment. Through collating and assessing the opinions of practitioners and academics, the prevailing importance of soft skills for project success across the construction industry has been engendered. Encouraging the adoption and development of these skills in employees will engender further tangible benefits to project efficiency and success in the PLI sector.

Advancement in the development and application of skills can be encouraged via the creation of decision support tools. By using the decision support tool as a conduit for tracking and developing skills, this actively enables both individuals and institutions to take ownership of their skill development pathways and progression. Consequently, more skilled individuals usually lead to more efficient and successful projects. By becoming more proficient at fulfilling projects to time, cost, and quality metrics, this leaves capacity for focusing on innovation and growth, forefronted by the increased emphasis on developing creativity and curiosity in the workforce. These benefits have the potential to be applied across the construction industry, not just PLI.

Advanced digital innovations are not sentient and cannot yet build infrastructure without human intervention, i.e., skilled operators, planners, and engineers. It is impossible to return to a time before machines, but a fully automated age remains a distant aspiration. Consequently, a greater emphasis should be placed on investigating the co-dependence and symbiotic nature of the relationship between human and machine to increase project success through streamlining management and performance.

Addressing the crucial lack of knowledge in this area must become a priority. Without facilitating skill development and growth using tools such as the one presented, industry and government economic targets will be missed. More research must be conducted to keep pace with the overwhelming investigation of the false panacea of automation and digital technologies which is framed as the future of construction. With the advent of Industry 5.0 and its human-centred focus, an investment in people and skills is a seminal key to fuelling development in an industry becoming more digitally reliant and saturated. By investing in people, skills and the tools to manage them, this could be the diversion to avoid a sector becoming stagnant and the key to creating a foundation for innovation in the next generation of professionals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K.D. and J.J.P.; methodology, H.K.D., J.J.P. and D.J.E.; validation, H.K.D., J.J.P. and D.J.E.; formal analysis, H.K.D., J.J.P. and D.J.E.; investigation, H.K.D.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.D., J.J.P. and D.J.E.; writing—review and editing, J.J.P. and D.J.E.; supervision, J.J.P. and D.J.E.; project administration, H.K.D., J.J.P. and D.J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding; it was non-monetarily supported by National Highways and the lead authors PhD studies are gratefully funded by Birmingham City University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to an ethical protocol that was approved by the Computing, Engineering and the Built Environment Faculty Academic Ethics Committee) of Birmingham City University (Edwards/#7741/sub1/Mod/2020/Sep/CEBEFAEC—BNV6200 ACM Version D.J. Edwards—13 October 2020).

Data Availability Statement

Anonymised data can be made available by the corresponding author upon written request and subject to review.

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the support of National Highways who gave their full, non-monetary backing for the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Question Aggregated Answers

Appendix A.1. Answers to Question 2

| Question 2: A Review of Literature Has Found the Following Soft Skills to Be Considered the Most Important to Enable Project Success in the Construction Industry: Communication; Leadership; Problem Solving; Conflict Management; Negotiation; and Creativity and Curiosity. What Are Your Thoughts on This? | ||

| Participant | Comment(s) | Implication |

| Participant A | “OK, I would definitely agree that all of those soft skills are particularly important and for different reasons. Uh. So, I would agree that those skills are highly needed in this industry. I think where there’s a discrepancy is probably how well those skills are executed. From my experience, so particularly leadership, I think people will often maybe conflate leadership with a management role or a management title. Whereas leadership skills aren’t necessarily synonymous with the job title, I think anyone can have leadership skills.” “Only ones maybe that I would add. I mean, it would come under leadership potentially is decision making and adaptability. Maybe flexibility. So, I would say maybe comparing communication and leadership, I don’t think anyone is really born a leader. I think that is something that does require a lot more training, whereas communication links more with I think personality types or personality traits.” “If we’re accepting that everyone is different and diverse, then surely we shouldn’t be trying to standardize soft skills training across employees.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant B | “I think obviously communication is the key… transparency and then to be honest with the communications. I think it’s very important to empower our team rather than tell them. As a leader or even as a team member, the main thing is we have to listen to others. So that means we need to have active listening…” “In terms of conflict management, I think that’s kind of a last resort, I would say because if you got good leadership qualities and then you got communication and problem solving and your listening skills, be empathetic and all these things like I don’t think conflicts would arise. But if there’s a conflict arise so that basically even not in negotiations, I think even if you having dialogues, you can sort out those kind of problems.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant C | “My viewpoint is normally around curiosity. I think you make for a better QS construction if you’re curious about the stuff going on around you. So, you’ll get a better outcome if you’re curious. Umm, certainly you need leadership. Uh, you need and direction and objectives… but it’s open conversations on both sides about what your true goals are and understanding the constraints of each party. So, openness and honesty.” “There is always a mix. Sometimes some skills are more important than others. The idea about conflict management is you shouldn’t have to get into conflict management if you’re doing everything well in the 1st place…you keep the passion out, it’s not personal.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant D | “I would say that they are, they are absolutely the essential ones. Communication being the first one that you identified most definitely and it’s something that I think not just our organisation, but all organisations can really work on, you get pockets of excellent communication.” “Again, it’s about embedding best practice and it’s about guiding and managing and developing people in that way so they can build their own capacity and their own development. So, I think in a nutshell, it’s about, it’s about good communication, good connectivity… success comes from a greater understanding and respect for each other. And you know, as we continue to develop in the purposeful way. We can, we can really understand that… So, all of these are so interrelated problem solving, I think there’s just a deep-rooted curiosity that we should all have. We should all be challenging and asking those five why questions.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant E | “So, the first five I hear often really often, and the 6th one (creativity and curiosity) I don’t hear that often actually, but agree with. So, the most common thing I’ve seen when I’ve been around our industry when things go wrong—It very often comes down to a breakdown in communication that wasn’t caught quickly enough.” “The creativity and curiosity, I think, is the most interesting for me there, and I think possibly a really important one and is where we’re realising we need to go. I think the diversity in our industry is really important to allow for that. I think some of the others you can sort of drive through a process quite easily but creativity and curiosity is harder to do that way.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant F | “I think creativity and curiosity is an interesting one, because that’s one I’ve never really come across before. In terms of the others, the contract that we have is very much around collaboration, about working together to deliver what is expected and all of those skills come into it. There, there have been lots of changes in personnel I think those different personalities and your ability to work with those different personalities is really key.” “So around comms, problem solving and conflict management. I think the ability to do them and do them in a way where you both understand what the other is trying to achieve is really critical from the sort of contract management side, but also those softer skills are really critical from a line management perspective. Relationships is not on there and I think it’s, particularly in my role, really critical. For all of that stuff, really working collaboratively, yeah, that’s the umbrella, isn’t it?” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant G | “I think absolutely all are essential. So, you know communicating, how you can pull the pertinent and the salient out from the masses of protecting self-interest? It’s really important. Yeah, leadership and problem solving, it’s how you delegate and allow people the authority to perform tasks. You still need to be able to make decisions, so it’s really important that you empower the team… how you could build that trust.” “Unless you have innovation and change, unless you’re curious about something how are you going to do something that’s different? So it’s really important, I suppose it’s dependent on the time you have to make a decision. You know, if you’ve only got a short time, you can’t pursue perfection and to the detriment of good. It’s about balance with I think curiosity and questioning. You know there are times you need to just get on and do. But you should have an environment that you invite people to be curious.” “It’s really important to understand that it’s not one size that fits all… it’s really important to understand the complex team and bring out the best of them. I mean, it’s part of leadership, but it’s tolerance, you know? Tolerance and understanding of the positive and negative sides of behavioural traits that people have.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant H | “I think from a leadership perspective, I think communication is really important. I think trying to get a clear message across to people is important. Problem solving, I sort of link that to leadership in terms of decision making. The conflict management yet again linked to leadership again.” “I don’t think the best leaders I’ve worked for necessarily use a handbook type approach. It’s almost secondary to that, so they’ll just happen to have certain traits that are that are very positive. So, for example, some of the best people that I’ve worked for, the ones that allow you to feel comfortable, comfortable enough to speak freely and they create the right environment. Environment, I suppose, is potentially one word to it to include all that.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

Appendix A.2. Answers to Question 3

| Question 3: From Your Experience, Do You Believe the Skills Previously Mentioned Are Applicable to Public Linear Infrastructure Projects? | ||

| Participant | Comment(s) | Implication |

| Participant A | “I think particularly problem solving and where they were calling a creativity and curiosity or are very important to this industry (PLI)… I mean, they are all of those things. Communication, leadership, problem solving, conflict management, negotiation, creativity, slash, curiosity are all particularly needed within the industry that I work in. Umm. Umm, like I said earlier, I think the extent the difference is how well those soft skills are executed at the moment and I can’t really think of anything to add to that list either.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant B | “I, I think those things are relevant for any industry. I mean irrespective of linear construction, or I mean even if you’re working for some other teams.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “For construction, I think negotiation and conflict avoidance or conflict management would be kind of a things I think people should train because I think it’s not kind of a skills you can, it is not readily available… it’s something you have to acquire… so those are, I think, more specific for not only for linear construction, but for construction as a whole, other soft skills. I think it’s pretty much you can apply for any other industries.” | ||

| Participant C | “I think they apply to any construction project, regardless of whether you’re linear or not.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “When you’re private, your stakeholders are slightly different. If you’re public. So, when you’re when you’re public, you’re you have to understand stakeholder management and you have to understand customer management… sometimes that can be a conflict in terms of conflicts of interest.” | ||

| Participant D | “Well, yeah, I think I think, yes, any infrastructure or you know it’s good common practice, good sense, it makes common sense. So, aligning these in any discipline in any industry, in any sector it is a very strong foundation in terms of in terms of approach.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant E | “I think they apply the same and in some ways because of the repetitive nature of what we often do in public linear infrastructure, and we’re often doing the same thing we can get better and improve at it. It possibly gives us more of an opportunity to apply those (skills) really well and to keep those moving.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I’m fairly happy with the six because teamwork possibly lies within them. I think good teamwork is real is important, but whether that’s contained within these, or whether it needs its own separate thing—I’m fairly flexible.” | ||

| Participant F | “Those softer skills may be applied differently, but I think they are the importance of them is consistent across both.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I think they’re equally as important to both, it’s different because you potentially got a different dynamic in construction. There are different things that you need to consider, but I think working collaboratively and the application of those skills, I say it might be applied in a slightly different way due to the personnel that are involved.” | ||

| Participant G | “You know, through the move away from adversarial into solutions and building trust and I think the partnership, mutual trust and collaboration you know in accordance with the conditions in the contract… what we want is to bring out the best and those better traits that you said on that list. Is what we want to nurture in the industry, and I think if we go back to being more adversarial, it is just short-term gains.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant H | “I’m struggling to decide in my own head whether there’s any variance in terms of who you work for. So, it’s on that basis, I’d say that they all apply. As far as I’m concerned, particularly in a leadership role It’s all about people and I think the ability to lead and get the best out of people involves having the skills to not just manage people it’s getting the best out of people in terms of what’s achieving that end goal.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

Appendix A.3. Answers to Question 4

| Question 4: The Research Proposes to Create a Decision Support Tool to Allow Managers to Make Teams with the Optimum Soft Skills or Identify Skill Gaps Within Teams. Do You Think This Tool Would Be Useful? | ||

| Participant | Comment(s) | Implication |

| Participant A | “Some sort of tool definitely would be useful. I would be very cautious and very critical in how I approached any tool that was presented to me because of that need to balance and to appreciate people’s personality traits. So I think it’s important to ensure that any tool isn’t too rigid and that it does take into account each person’s personality and what’s comfortable for each individual, rather than having this top down tool that says as a business, we want to have more problem solving skills and therefore we’re just going to select the people who maybe have the most time available.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I don’t think it’s fair to say, as a senior quantity surveyor, you’re up here on the hierarchy, so therefore you should have more soft skills than somebody lower down, because I don’t think it is that rigid and subjective. I think soft skills are much more dynamic than that, much more nuanced. So, I think that’s the one concern I would have about a tool. Yeah, I think the key to it would have to be that it’s descriptive rather than prescriptive. So, I think if it’s something that allows me to access the right information to carry out the training that I might already want to do, then that’s absolutely brilliant. Whereas if it’s something that’s prescriptive that just tells me I have to do this for this person or, you know, I think that’s going to be a little bit harder to implement.” | ||

| Participant B | “Yeah, of course… I haven’t seen something kind of a decision support tool to understand others soft skills. So that I think that’s a good, good, good one to be honest with you.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “What will happen is if the team performing well, that means there’ll be an more output we can get from each and every team… Overall, as a public organisation, we got massive resource pressures. So, we don’t have we, we haven’t I mean got a lot of staff but we got very limited number of resources. That means if we got more efficient teams are in operations, that means we can achieve more with the same given number of resources… So that means it’s practically increasing efficiencies.” | ||

| Participant C | “Umm it depends because it’s really difficult, where when we do it as a public body to go out and look for people, we’re looking for professional skill sets of which the soft skill set might be part of that. But actually, being able to identify whether one part of that skill set is greater than another part of that skill set is quite tricky…I don’t know how you would pick off one versus any of the other soft skills.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “OK, so that you then go through their competence and ‘how is your, how’s your soft skill in leadership and how’s your soft skill in in communication?’ Yeah, if you if you can start to define that in a way that actually you can then go back and say give me examples of then then I can, yeah, that would be useful… So yeah, adding soft skills to that is really useful, and I expect we’ve got some of them, but not necessarily all of them.” | ||

| Participant D | “No, 100%, 100%... so being technically gifted is brilliant, but actually how you approach this is more important. I care what you do, but I care more about how you do it… this is all about sort of good leadership and good performance management because that then gets the best out of everybody’s contribution. These soft skills are really a great tool to take people on that journey.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “Success comes back down to winning vital support and improving alignment and collaboration with others. So in order to be successful, you know, we have to strive for willing participation and buy in from others in order for us to be successful. So the benefits of all of these are high, high, achieving objectives. It’s around aligned and efficient teams… It’s about enhancing the overall employee experience. It’s about improving the end to end. It’s about increasing innovation. It’s about boosting the business insights and ultimately then it’s about improving. Whatever it is we operate in, in terms of our overall delivery and efficiency.” | ||

| Participant E | “It could be, but I think for us it wouldn’t be about an individual project team. It would be about a broader team. We deliver stuff at a portfolio level so often it’s not about an individual project because they’re too quick.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I think it’d be like of the people delivering this certain type of scheme… the sort of skills we would need in that overall team. Being able to say in a team like what are we lacking? What haven’t we got in the team? Here’s the gaps we need to fill. Then we could maybe be bespoke about recruitment and things.” | ||

| Participant F | “Absolutely, I think for me personally, it would be useful to understand if there are any skill gaps around those softer skills in the wider team. So, I think the decisions support tool will help to identify where there are any sort of training or skills gaps, what’s needed to close those skill gaps and also how those skills can then be applied to better deliver the service.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| Participant G | “I think it’s understanding the way that the people react operate the strengths and weaknesses and then being able to apply that into a practical scenario. So, if you’ve got a decision tool that then can be, I suppose you know finessed around the individual.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “A checklist is absolutely key, and a decision tool is, you know, in some ways that checklist. How can you provide that summary checklist to us? A complex task that people can understand the task from the simple cues that you’re giving.” | ||

| Participant H | “It’s hard to say without seeing it in action. How it’s ranked and scored? Because I’d say some of that could be subjective. So, I suppose I’m reluctant to make a decision without knowing what the criteria would be, because it will be very subjective. I think I’d have to see in action and see what see what comes out at the end of it. The things I’ve done in the past, it’s spat out a result about let’s say for example what I’m good at or what I’m weak at etcetera, and when I’ve discussed that with people that work me day in day out, they say, well, we don’t think that at all. I think it’s a difficult one to implement. So yeah, I suppose I am a bit sceptical really.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

Appendix A.4. Answers to Question 5

| Question 5: Can You Imagine What form a Tool Like This Would Take? What Form Would Be Easiest to Use and the Most Effective at Identifying the Skills of a Team and Assigning a Structure/Role? | ||

| Participant | Comment(s) | Implication |

| Participant A | “Venn diagrams. Yeah, kind of resonates more than a because we’re not really talking about processes here. I think the tool would have to be, almost democratic in the sense that it would require. I think everyone using it would have to really buy into the benefit of it… rather than feel like it’s something that they’re being forced to do, and I think. It would have to be democratic in the sense that everyone could get use of that tool rather than it being a management tool… there needs to be a like a balance of power really.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “Taking the, the onus away from the company to address issues and maybe putting it more on to staff to say… employees need training rather than dealing with the root of the problem, which might be per systems or processes or other issues like that.” | ||

| “My suggestion would be to start with data and if you have a number of projects over the last year, 100 projects, if you can work out how to indicate success, what makes a successful project… So, if you have that kind of our criteria and if you know what success looks like in terms of the hard skills, they the more objective kind of factor… It would really need from me, personally I think to align objective measurements of success with soft skills. It would really need some sort of trend analysis or statistical analysis to build that training tool off the back off.” | ||

| Participant B | “For me, the main thing is it’s easy to navigate. So, I don’t like I mean very complicated things… if it’s kind of a user-friendly format, automatic automated format or something like that even I mean these days I mean Ms forms, do I mean metrics these days, right? I mean it’s easy to navigate and its very user friendly and it’s basically it’s encourage people to check and everything.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I mean there are loads of complicated stuff people can’t understand. But I mean I think even if you capture everything for it forms, I think you can develop those because I mean from forms you can do Excel spreadsheet and from excel spreadsheet it can go to power BI dashboard or something like that, right? So yeah, there are a lot of new ways of presenting data. Or outcomes.” | ||

| Participant C | “Oh, I always go for an Excel spreadsheet. Yeah, a table where they fill out where they think they are… If you could do a, if you did a Venn diagram or you could do one of those. Umm. Well, like spiders web, do you know the spiders webs where you put your mark on to where you are against each of those little topics…So for me the Venn diagram would only work if you can show the growth of people so it depends what you’re looking for, but a Venn diagram shows you know these are the basic components and if you add them all up it makes a whole. But ultimately the Venn diagram will only overlap two of those at a time… a spider works quite well because you can start to show your own improvement as you as you go around against each of those tabs and then you could have different a grading as well as you go through.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “I still think you need the Excel spreadsheet or the Word document. That then explains what each of those parts means. Yeah. Yeah, and trackable too. So, you can show growth. So, it’s a rather like your personal development plan.” | ||

| Participant D | “We’ve had the most success is defining what the problem is. Uh, So what is the problem? And then and then working back that sort of problem statement content. So what’s missing in terms of structure, what’s missing in terms of material, what’s missing in terms of systems or software or investment or budget and these for me are really tangible … What we tend to do is really kind of align things to a to a tried and tested measurement.” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “Venn diagrams are great. But does the Venn diagram tell you the problem that you’re trying to solve? And I think have the direction we would like to be X and what’s the problem statement getting you there and then through things like strategy, people, tech tools, performance reporting process, that’s one thing you can get to the answer in terms of my approach.” | ||

| “If you want to create improvement, you’ve got to understand what the value proposition looks like and what good looks like in terms of the end of it. So, if you’ve all got the same view of what good looks like, then you can work back to figure out that kind of. Maybe like you say, process flow diagram.” | ||

| Participant E | “So I think digital is important. I think not using bespoke software that somebody would have to get used to or have a log into or whatever is important because I think it just becomes complex. I think it needs to recognise the fact that a manager would rarely use it. So to be successful, it’s got to allow you to dip in. It’s got to be obvious how to use it and obvious how to work through it so I’d say simplicity is really important in it. I’d like to see it using a generic piece of software or a generic, you know, PowerPoint or excel… or an online link” | This participant focused on the following:

|

| “If you’re trying to develop yourself personally, fine, it can be used for that. Equally, if a manager is trying to build a team, they need to be able to use it as well. What I would say is I’d really like to see something that wasn’t biased. So I think when these are developed, sometimes they value some skills or some personality traits more than others. But overall, in a lot of what we do, you probably want a mix of personality types. If I use it personally, I don’t come away thinking well, I’m useless because I don’t have this certain personality type.” | ||