1. Introduction

Informality is one of the inescapable facts that cities and their residents deal with on various levels throughout perpetuity [

1]. The phrase is generally used to refer to unlawful activities that transgress land tenure and urban planning regulations in urban areas [

2,

3]. Fernandes claims that a number of factors contribute to informality, such as poor incomes, impractical urban design, a dearth of social housing and serviced land, and broken legal systems [

4]. Among these, informal space transportation is a major factor in cities all over the world and is typically described as haphazard, impromptu, or unplanned [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Thus, in many cases, transportation in informal spaces tends to take on the character of residing in the interior, with chaotic traffic conditions that make informal spaces enclaves in the city [

9,

10]: thousands of electric carts and tricycles carry out the delivery of people and logistics between their transportation points, and the intertwining of these haphazard flows cuts the area off from the external formal transportation network, which makes the area seem like an isolated island cut off from the outside world—but that is a glaring simplification [

11]. In fact, many scholars consider this to be an efficient operating system produced under the influence of various factors, in which residents of informal areas achieve resource-intensive guidance and coordination through careful allocation of labour and resources. However, this process is inevitably limited by the historical legacy and developmental changes of urban spatial patterns, necessitating corresponding adaptive adjustments by the operating system, which results in a surface appearance of chaos. For the internal users of informal spaces, urban road space is similar to Hamilton–Baillie’s “shared space”, where transportation and social activities coexist, and where “eye contact and human interaction replace signs and rules” [

12]. Due to the flat surfaces lacking clear demarcations and the virtual absence of traffic control measures, road users are compelled to become more vigilant, moving at reduced speeds and relying on environmental cues and negotiations of right-of-way to navigate [

13,

14]. Numerous studies have been carried out on transportation in informal areas at various levels, including studies on the transportation of electric vehicles [

15], traffic disturbance and congestion in natural marketplaces [

16], and the economic and historical aspects of workers in transportation [

17,

18]. There are, however, very few globally applicable key practices due to the widely variable conditions found in different cities and areas of the world, each with a complicated history of local politics and regulations, urban shape and infrastructure, industrial types and capital demands, and transportation [

17,

19,

20,

21]. It is possible to gradually improve most existing informal spatial designs in situ, with a few exceptions in places prone to hazards. To maintain the status quo, this upgrading process must be predicated on a thorough comprehension of the current configuration and level of operation of the informal transportation network. At the same time, a thorough grasp of urban morphology and evolution is also essential for better design interventions, as some upgrading practices may seem to be less compatible with the spontaneous adaptation processes of informal urbanization [

22,

23]. Currently, research on the function and influence of people’s roles and pathways within informal spaces on the construction of informal transportation networks, as well as how their demands for mobility, accessibility, and urban space differ, is scarce, especially in the setting of China. Transportation activities within informal spaces are inevitably subject to interventions from urbanization practices. What power relations are embedded in this process and what spatial factors are influenced by it?

This study looks at Zhongda Textile City and its surrounding garment villages in Guangzhou, China, with the goal of determining the causes of the chaotic traffic congestion there as well as the needs and characteristics of the area’s informal labour population. We aim to further enhance our understanding of the complex dynamics of increasingly varied neighbourhood settings in China’s transitional cities by examining the process of spatial change at the neighbourhood scale. In light of China’s increasing urbanization, this study also contributes to the analysis of the mechanisms underlying the creation of informal space and its societal ramifications. As the capital of Guangdong Province and a core city of China’s Greater Bay Area, Guangzhou is a megacity with a registered population of 18.7 million and an administrative area of 7434 km

2. Located in the Pearl River Delta, the city has served as China’s southern gateway for global trade since the 3rd century CE and is now a national central city with a GDP exceeding CNY 2.9 trillion. Its unique “market cluster + industrial cluster” model has fostered over 600 specialized wholesale markets, forming one of the world’s most complete textile and garment industry chains. As Asia’s largest textile and garment industry cluster located in the centre of Guangzhou, the Zhongda Textile City has an important position in urban space and industry [

24,

25]. The mix of urban settlements and commercial buildings creates a lot of informal places, and because of the nature of the industry, there is a lot of informal employment and transportation in the area [

26,

27]. These characteristics make it conducive to an in-depth investigation of the interplay between the formal and the informal.

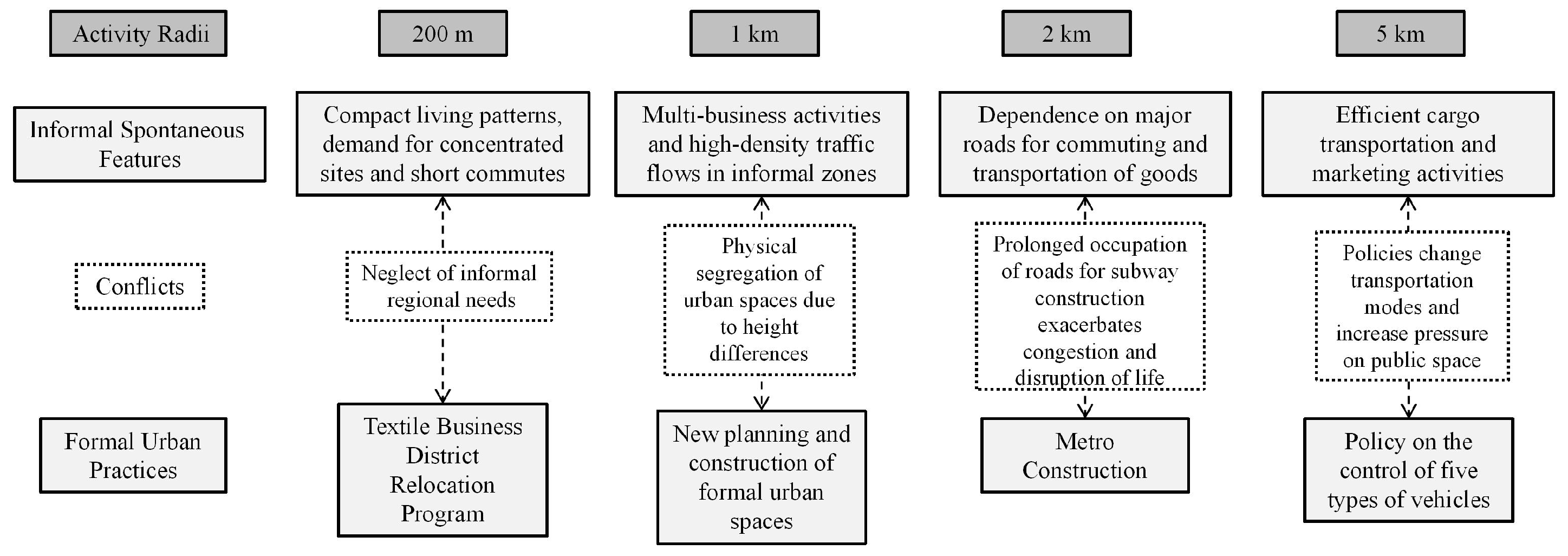

This paper proceeds as follows. We will use the activity radius as the dominant factor in establishing a mixed methods research framework for the Zhongda Textile City. After that, we will go over formal urbanization procedures and unofficial transportation operations at each of the four radii, along with any problems that may arise. We will wrap up by talking about how conflict negatively affects urban spatial relations and how planners might work to advance an inclusive agenda within these intricate relationships.

2. Materials and Methods

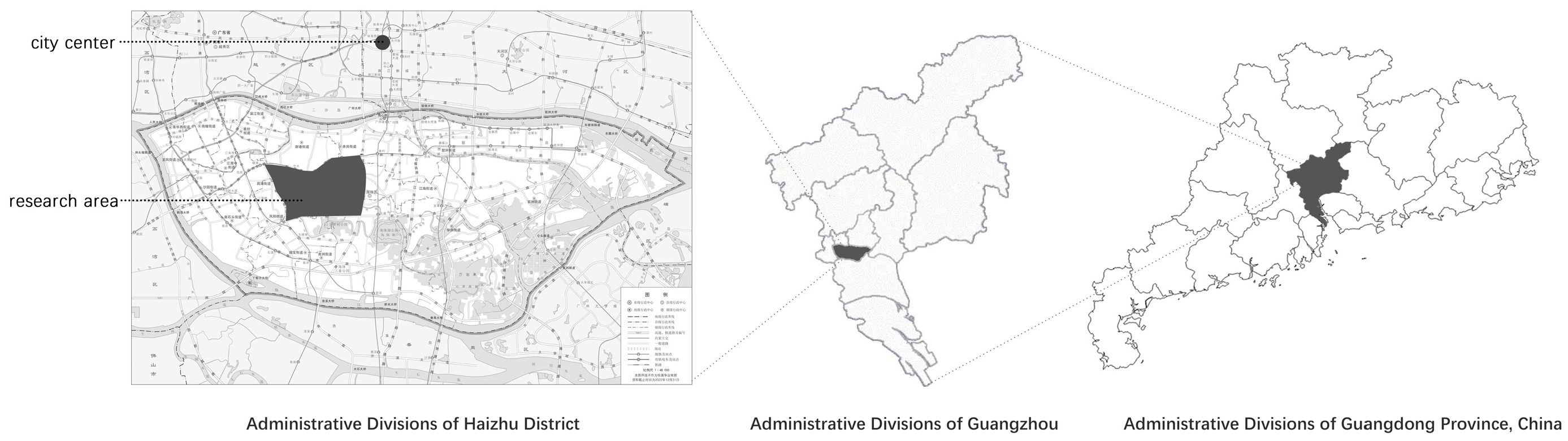

The Zhongda Textile City is situated in Guangzhou’s Haizhu City, as shown in

Figure 1, at the meeting point of the city’s old and new central axes, just five kilometres from the city centre. The Zhongda Textile Market is located on both sides of Ruikang Road in Haizhu District, Guangzhou, adjacent to Sun Yat-sen University. Covering an area of approximately 3 square kilometres, it comprises 59 sub-markets and from 20,000 to 30,000 shops. The market employs a total workforce of about 300,000 people, among whom approximately 100,000 are engaged in informal employment, primarily working within urban villages. According to the Haizhu District Fenghe Village (Kangle, Lujiang) Basic Data Survey Report, this informal workforce accounts for one-third of the total employed population. Based on an estimated total population of 300,000 and an area of 3 square kilometres (3 million square meters), the average population density is approximately 100,000 people per square kilometre. However, the distribution is highly uneven, with significantly higher densities in urban village areas. Despite being a very significant metropolitan region, the surrounding citizens are reluctant to participate in it because of the severe traffic congestion [

28]. The textile industry has a proverb that stems from the current state of the sector: “For fabrics nationwide, look to Guangdong; for Guangdong’s finest, look to Zhongda.” [

29]. Specifically, over half of the nation’s mid-to-low-end women’s ready-to-wear garments originate from the three major “garment-making villages” of Lujiang, Wufeng, and Kangle in the Haizhu District of Guangzhou. The Zhongda Textile City, located within the Kangle village area, plays a pivotal role in the domestic garment industry [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Considering the current state of the venue, it possesses distinctive characteristics. Along Ruikang Road, there are glamorous commercial buildings, such as the International Light Textile City, but, turning into the side streets, one immediately encounters the low, dilapidated self-built houses of the urban villages. Unlike the typical urban villages primarily focused on residential living, this area exhibits distinct characteristics of the textile industry. Here, corners overflow with bulging blue woven polypropylene sacks, while the occasional rumble of trucks, vans, and tricycles weaves through the air, mingled with stray wisps of cotton or silk, continuously signifying that this place is an informal textile city. This spatial duality mirrors patterns observed in global South cities like Dhaka’s garment districts and Istanbul’s Laleli textile zone, where formal–informal hybridity emerges from rapid industrial agglomeration [

35,

36]. Guangzhou’s case is particularly emblematic of China’s “world factory” urbanization model: its textile cluster combines migrant labour, informal logistics networks, and state-led market upgrades. The Zhongda Textile City is defined by the coexistence of formality and informality, with informal individual transportation accounting for the majority of the active population’s mode of transportation. Three factors establish Zhongda’s paradigmatic value: First, its 30-year organic growth trajectory (1992–present) encapsulates China’s transition from labour-intensive manufacturing to digital economy integration, offering comparative insights for Global South cities at similar developmental junctures. Second, the 5 km

2 study area concentrates 23 wholesale markets, 15,000 micro-enterprises, and 300,000 daily logistics trips—density metrics surpassing Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar (1.5 km

2/4000 shops) and comparable to Dhaka’s Narayanganj cluster [

37], enabling scalable observations. Third, Guangzhou’s “villages-in-the-city” morphology, where 138 urban villages house 60% of the migrant population, provides a distinct Chinese variant of informal settlements observed in Rio’s favelas or Nairobi’s slums, yet with stronger industry–space coupling [

38].

Investigating the pathways of people within the Zhongda Textile City is crucial for understanding the congestion within the area and how the dynamics between formal and informal spheres collectively contribute to make it an “urban enclave”.

This study’s methodology is based on the mixed-methods framework put forth by Ha Minh Hai Thai and colleagues [

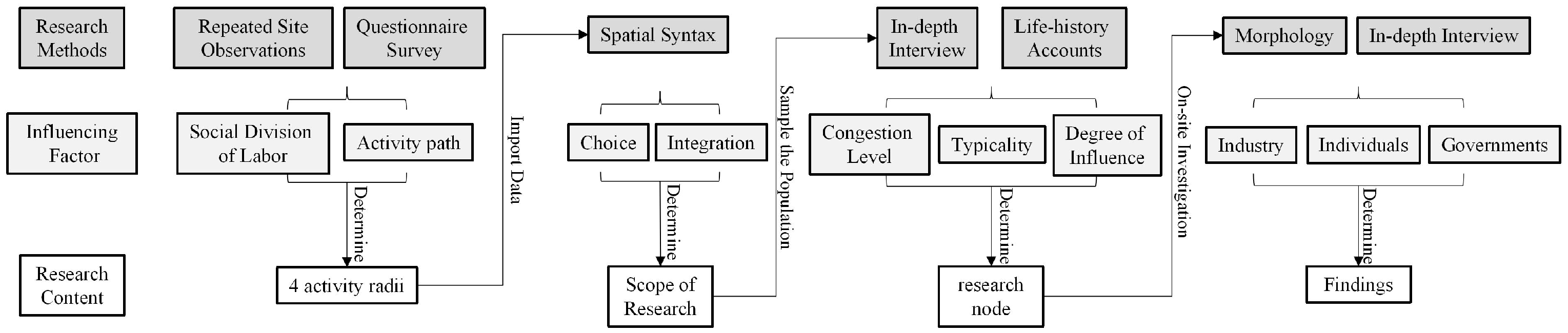

39]. Their method is primarily used to understand the spatial patterns of pathways in informally developed networks and the connections between these and informal urban business models, making it suitable for small-scale urban environments, which partially aligns with our research site and subjects. However, considering that their methodology does not suffice for a comprehensive study of roads and crowds across the entire area, we have fine-tuned and enhanced our approach. We adopted a hybrid research methodology framework, led by an activity radius, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The dominance of activity radius as the research content gives this study two main innovative advantages. Firstly, the activity radius in this study is derived from questionnaire and path tracking surveys, which encompass all the region’s roads and typical residents. This approach enables a comprehensive analysis of the traffic congestion phenomenon in the region and the identification of credible causes. Secondly, the activity radius possesses both quantifiable and individual-based characteristics. The quantifiable aspect facilitates the use of Space Syntax for quantitative analysis of the choice and integration of roads within the area. Meanwhile, the individual-based characteristic aids in the analysis and classification of complex populations within the area, beneficial for employing morphological studies and in-depth interviews for qualitative analysis. Thus, the activity radius serves as an effective intermediary, integrating qualitative and quantitative analyses within the mixed-methods research framework of this study, rendering the findings more scientifically robust.

The framework of this study consists of three main research methods: Space Syntax, morphology, and in-depth interviews. Space syntax is a set of techniques developed by Bill Hillier and others for the quantitative analysis of urban spaces from a mathematical perspective, which aids in describing the spatial characteristics of cities [

40]. Numerous academics have used it to investigate the distribution of economic activity at smaller sizes on individual streets, the connectedness of streets within an urban network, and the effects of connectivity on pedestrian movement and transit-dependent land uses [

41,

42,

43]. Using ArcGIS 10.8 and AutoCAD 2022software, we first used high-precision satellite imagery from October 2023 as a base map to help us physically align the study site and draw the road network graphic data. The degree of route choice and integration in the area was then calculated based on the previously indicated activity radius, utilizing DepthmapX software as the primary measurement tool. The results of the calculations were used to determine the extent of the study roads for the different radii.

Nonetheless, several academics have noted that the spatial syntactic theory only addresses two-dimensional planar pathways, which is insufficient to address the intricate three-dimensional urban environment under investigation [

44,

45]. Specifically, the Zhongda Textile City and the surrounding garment villages exhibit significant topographical variations, coupled with multiple floors and complex stairways connecting textile workshops and urban villages. These three-dimensional spatial features present certain limitations when applying space syntax theory for path analysis. Moreover, the mixed traffic in the Zhongda Textile City and surrounding garment villages, dominated by bicycles, electric bikes, motorcycles, and cars, combines the characteristics of disorganized, slow pedestrian movement with the formal, fast movement of vehicles, making it unsuitable for study through Space Syntax. Consequently, after defining the scope of our study using space syntax, we employed a method involving in-depth interviews and life history recordings of the population within this scope. We then selected nodes for further morphological study combined with in-depth interviews, taking into account three criteria: congestion, representativeness, and degree of influence.

“Morphology” began as a biological approach to the study of biology and was later introduced by scholars of geography and the humanities into the study of cities, calling it urban morphology [

46]. Informal space morphological studies usually combine urban mapping, physical study, and description to investigate the materiality of these spaces. Moreover, while emerging quantitative methods of analysis have driven comparisons of the structure and function of urban form, many scholars continue to emphasize the need for qualitative research. We adopt a primarily qualitative approach, focusing on two- and three-dimensional morphological topologies to generalize the above-mentioned typical nodes and provide a detailed structural analysis to obtain a deeper understanding of how residents and practitioners perceive and utilize informal spaces. High-precision remote sensing map mapping, field research mapping, and images make up the majority of the data used in this study. These are upgraded to conceptual level analysis in order to better describe the study region and provide the research findings in an understandable manner.

In addition, in order to validate the data, such as spatial syntax and morphology, and to explain the anomalies, we used semi-structured interviews (77 respondents) to collect basic information about the site and people’s perceptions of the site. Sargeant defined criteria for ensuring the quality of participants in qualitative research [

47]. Building on his work, we selected participants who could best provide insights into our research questions, particularly the causes of traffic congestion and disorder in the study area, as well as the needs and characteristics of the informal labour force.

For factory workers (26 respondents), the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) continuous employment at the current factory for ≥9 months (to ensure accumulated experience in spatial usage); (2) daily commuting on foot (to enhance sensitivity to short-distance spatial perception); (3) participation in at least three instances of factory logistics coordination (to demonstrate awareness of process optimization). The screening method involved an initial selection based on factory attendance records, followed by secondary verification using union records on labour-management negotiation participation.

For stall owners and factory transport workers (27 respondents), the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) business or work covering ≥ 3 factory sites (to ensure experience in spatial connectivity); (2) an average daily cargo transport volume of ≥500 kg (to reflect transportation intensity thresholds); (3) at least two instances of cargo damage caused by road design (to demonstrate conflict awareness). The screening process relied on identifying high-frequency transport personnel through an industrial park logistics big data platform, cross-verified with the urban management department’s stall registration system.

For renovation workers and professional transport personnel (16 respondents), the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) engagement in both intra- and inter-park business at a rate of ≥30% (to ensure dual spatial experience); (2) possession of at least two types of transport vehicles (e.g., tricycles and trucks, reflecting multimodal transport capacity); (3) experience of business disruption due to road control measures (to demonstrate policy sensitivity). Screening was conducted by analysing geographic distribution data from freight platform order records, supplemented by vehicle registration information to verify transport diversity.

For external garment wholesalers (eight respondents), the criteria included (1) a cross-city transport frequency of ≥3 times per week (to ensure experience with long-distance mobility); (2) utilization of at least two different road classes for transport (to reflect route selection strategies); (3) at least one instance of order default due to local congestion (to demonstrate an understanding of systemic interlinkages). The screening methods involved retrieving ETC highway toll records and matching them with enterprise logistics ledgers, using breach-of-contract compensation data to infer the impact of congestion.

In line with grounded theory, we employed a maximum variation sampling strategy to select respondents with diverse lifestyles and conditions to capture a broad range of perspectives. No monetary compensation or incentives were provided to participants. The interviews, conducted by two interviewers in a semi-structured format, lasted between 19 and 33 min. One interviewer led the conversation, while the other took notes and posed follow-up questions. All interviews were recorded using digital devices, transcribed, and manually coded using thematic analysis. Participants provided both verbal and written consent for recording, and their identities were anonymized according to their preferences.

3. Results

Information obtained through questionnaire surveys and path-tracking studies was ultimately synthesized from 77 samples, summarizing the patterns of productive and domestic life paths of people within the area. We found that the productive and domestic life paths of the active population in the Zhongda Textile City region involve common urban roads and node spaces, as well as transportation modes. The most significant differences were manifested in the varying radii of activity within the region, which are due to different social divisions of labour among the study samples.

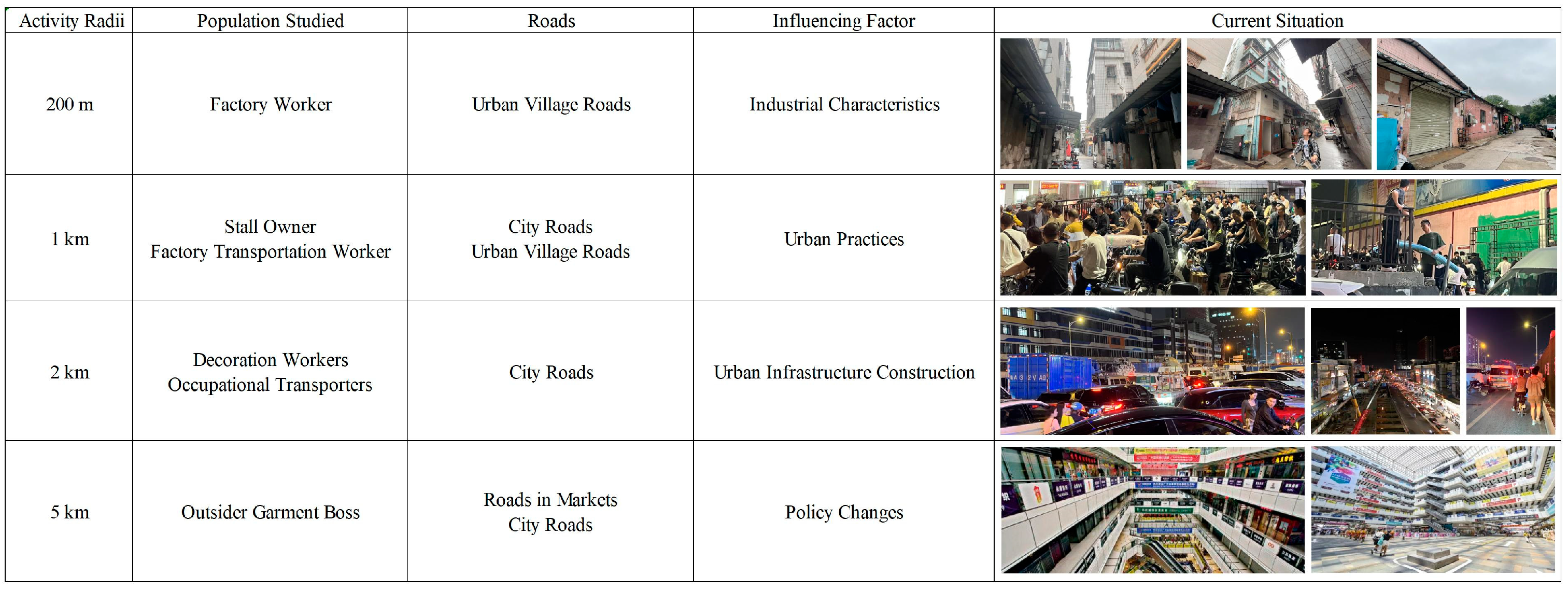

Consequently, based on the daily activity radius of the subjects, all samples were categorized into four types, as shown in

Figure 3. Individuals within a 200 m radius are predominantly factory workers whose daily activities are confined to roads within the urban villages, with typical destinations being dormitories, factories, and nearby eateries. Those with a 1000 m activity radius mainly consist of stall owners and factory transport workers; they primarily traverse city secondary roads and urban village streets, with their routine locales being residential communities, their stalls, and factories. Meanwhile, the 2000 m radius group includes renovation workers and professional transporters who utilize main city roads and secondary routes. Renovation workers frequent various neighbourhoods within the site, while transporters’ daily spots are urban village rental housing, recruitment points, and random cargo transport locations. The broadest radius of 5000 m is attributed to external garment business owners whose paths lead through market roads and main city arteries, typically to and from outer garment markets and the internal fabric market of the region.

3.1. Analysis of the Pathways Within a 200 m Activity Radius

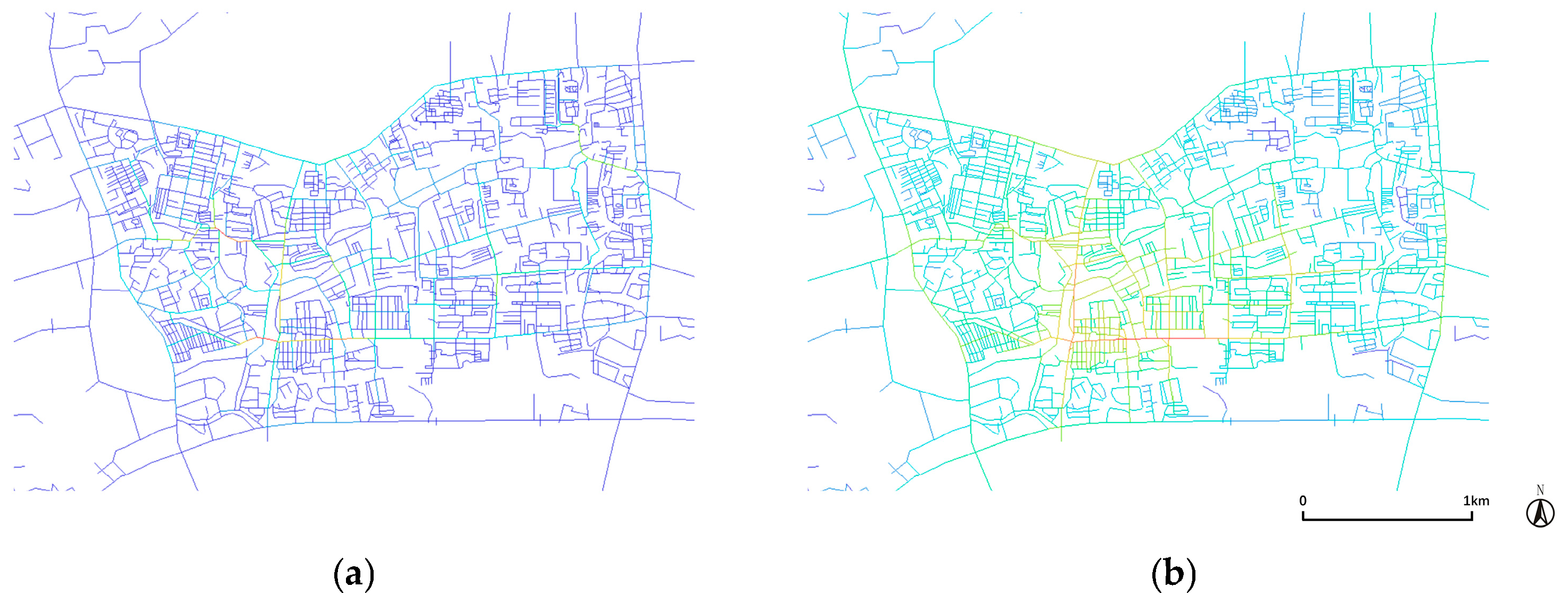

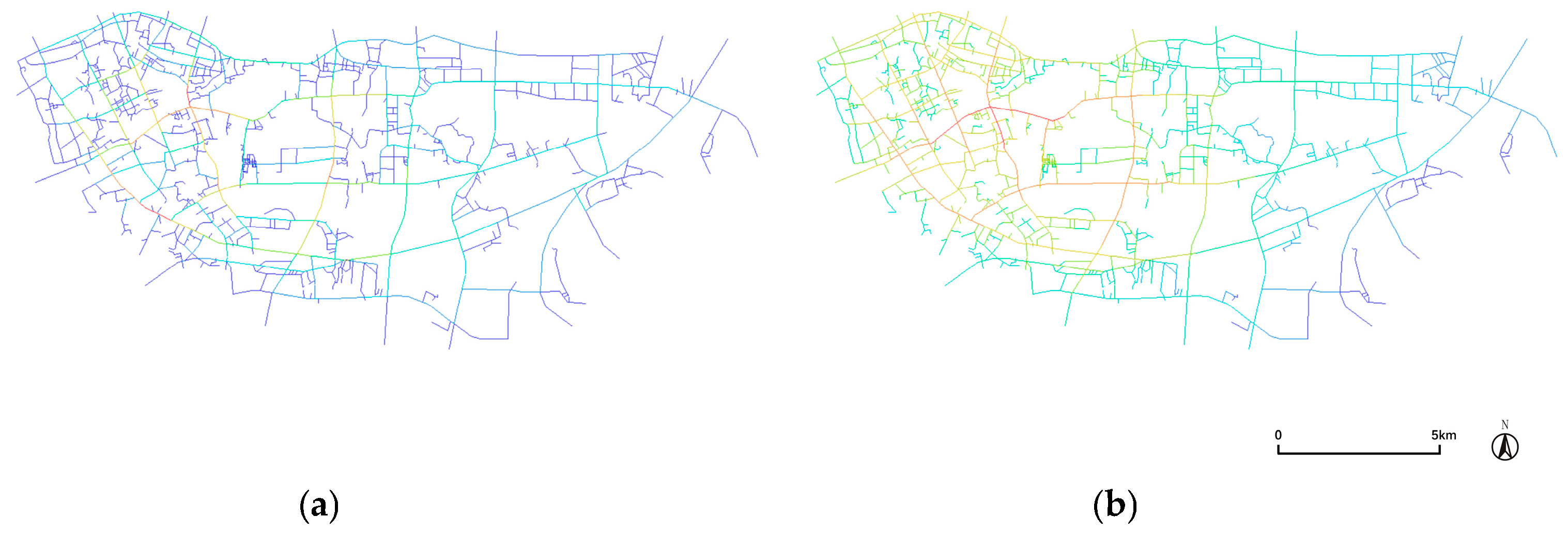

Initially, we conducted an analysis of integration and choice of the roads within the region using Space Syntax to assess the selectivity of a 200 m activity radius, as shown in

Figure 4. We can see that, under the original road system, the cyan, red, and light green roads have higher choice and integration values. These are predominantly the main roads and some secondary roads within the urban villages, which is consistent with the observation that factory workers concentrate their activities in the villages, as observed in our path-following survey.

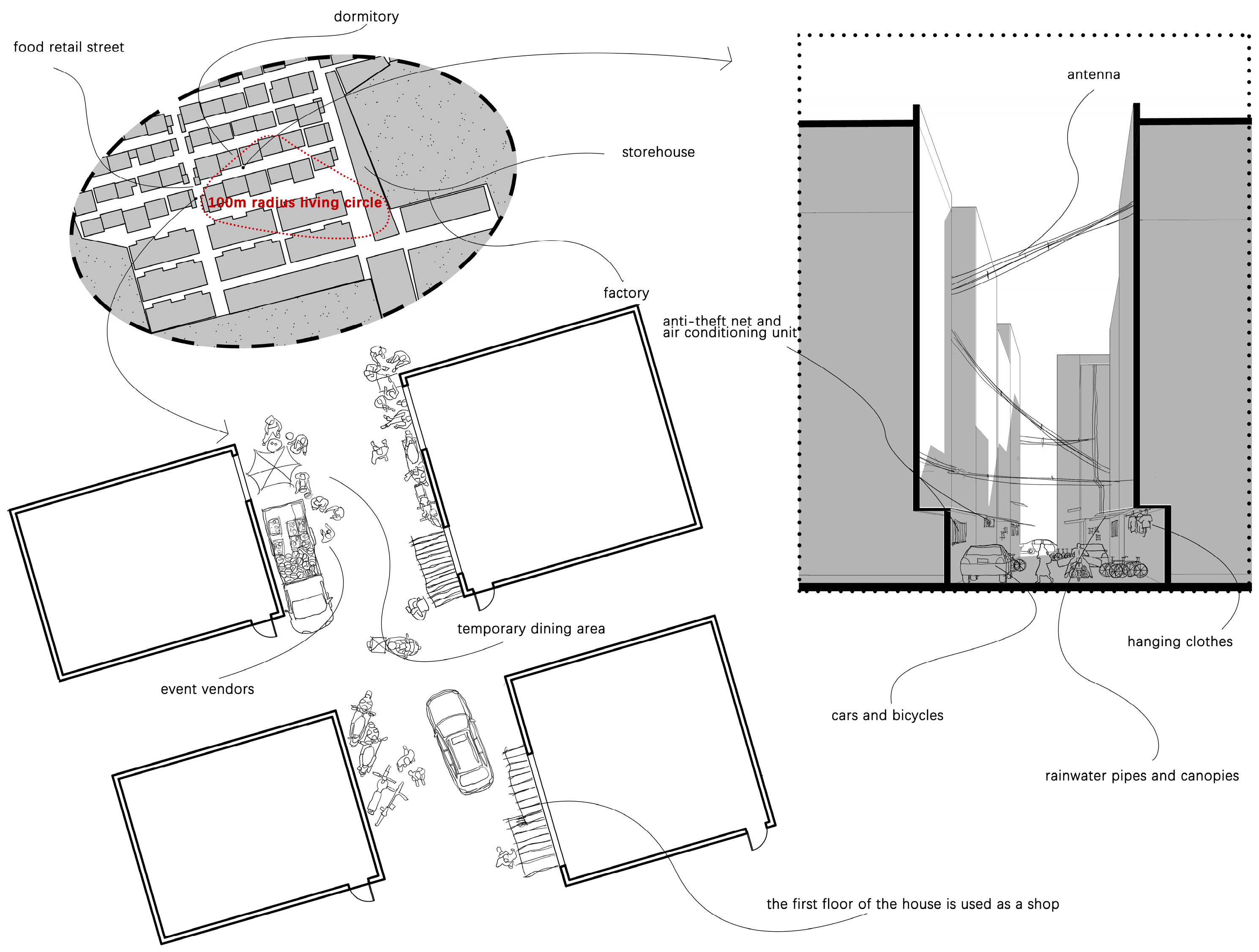

After determining the specific study area, we carried out a life history survey of the local populace and found that the factory workers in the area regularly travel between their factories, dorms, and food-vendor streets in urban villages; these three locations are all within a hundred meters of one another, forming a living circle with a 200 m radius, as depicted in

Figure 5. This compact living model is beneficial for industrial development as it ensures efficient operations. This naturally occurring living circle illustrates the textile industry’s unique requirement for centralized locations and short staff commute times.

During our in-depth discussions with locals, one factory owner provided confirmation of the model:

“I own this factory. Though not highly educated, I understand profit-making. I provided dormitories next to the factory, so employees can easily reach work, reducing lateness and excuses. This saves costs and increases profitability. Employees benefit as well, saving on rent in today’s expensive market.”

A factory worker shared their thoughts on the pros and cons of this arrangement:

“I work at this textile factory and I’m okay with the housing they offer. It’s right next to the factory, and there’s cheap food nearby. The dorms aren’t fancy, kinda cramped and damp, but hey, no rent to worry about. I can send my earnings back home to support my kids. It’s tough, but it helps my family.”

Despite the increased efficiency brought by the 200 m activity radius, it also leads to multiple issues including traffic congestion, as shown in

Figure 5. The dormitories that factory workers reside in, which are often converted from independently built homes in urban villages, have long been problematic due to their constrained streets and densely populated housing stock. According to three-dimensional morphological analysis, the five-meter-wide inter-building roads are often occupied by private cars, electric vehicles, and bicycles, significantly restricting the amount of available access space. Additionally, the narrow spaces between buildings are frequently occupied by debris, drainage pipes, canopies, and other building attachments, affecting the illumination and ventilation of indoor living spaces. From a two-dimensional morphological perspective, the dining and retail streets in urban villages, due to the presence of spontaneously formed storefronts and temporary vendors along the street-facing buildings, appear excessively crowded, even on main roads, making it even more difficult for electric and private cars to pass through.

Through in-depth interviews with factory workers, we found that the 200 m living circle not only leads to traffic congestion but also affects the physical and mental health of workers. Garment workers typically work over 12 h a day, day after day with virtually no cessation, lacking real holidays. Thus, various garment factories, both large and small, can rightfully be called “sweatshops”.

In response to the issues with the current state of affairs in Zhongda Textile City, the government suggested a proposal to move the entire textile business area to the nearby city of Qingyuan; however, the plan has proven impossible to carry out for a number of years. Through in-depth interviews, we discovered that the new industrial park’s planning disregarded the demands of those who work informally as well as the area’s naturally occurring industrial characteristics. We organized focus discussions (with the participation of eight factory owners). They expressed their views on why Zhongda Textile City could become the largest textile business district in Asia, highlighting the strong demand of the garment and textile industry for efficiently concentrated urban space:

A: “Our textile industry is super-efficient. Look, when we team up with clothing store owners, as soon as they spot a trendy outfit, they place an order, and our factory whips it up overnight. They can pick it up the next day.”

B: “Absolutely, here in Zhongda, everything from production to sales is interconnected. It’s seamless. Even if we consider moving to a new industrial park, we won’t find this kind of cooperation. The facilities aren’t keeping up, there’s no space for factories, and workers have nowhere to live. For us, with all the manual labour involved, it’s a mess.”

C: “Exactly, when I heard the government wanted us to move, I panicked. We’ve worked hard to get things going here. If we move, our efficiency will drop, and how are we supposed to run a business? We might not have fancy degrees, but we know this business inside out. It’s not just about location; it’s our way of surviving in this industry. The new place can’t meet our needs. We’re better off staying put.”

3.2. Analysis of the Pathways Within a 1 km Activity Radius

An analysis of the roads within the area was performed using space syntax to assess the selectivity and integration of a one-kilometre activity radius, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The two main urban roads that run through the site in the east–west and north–south directions, as well as the primary roads that connect the urban villages to these two highways, are observed to have a higher degree of choice and integration. These road segments typically connect the official and unofficial parts of the city or sit at their intersection, exposing two very different worlds.

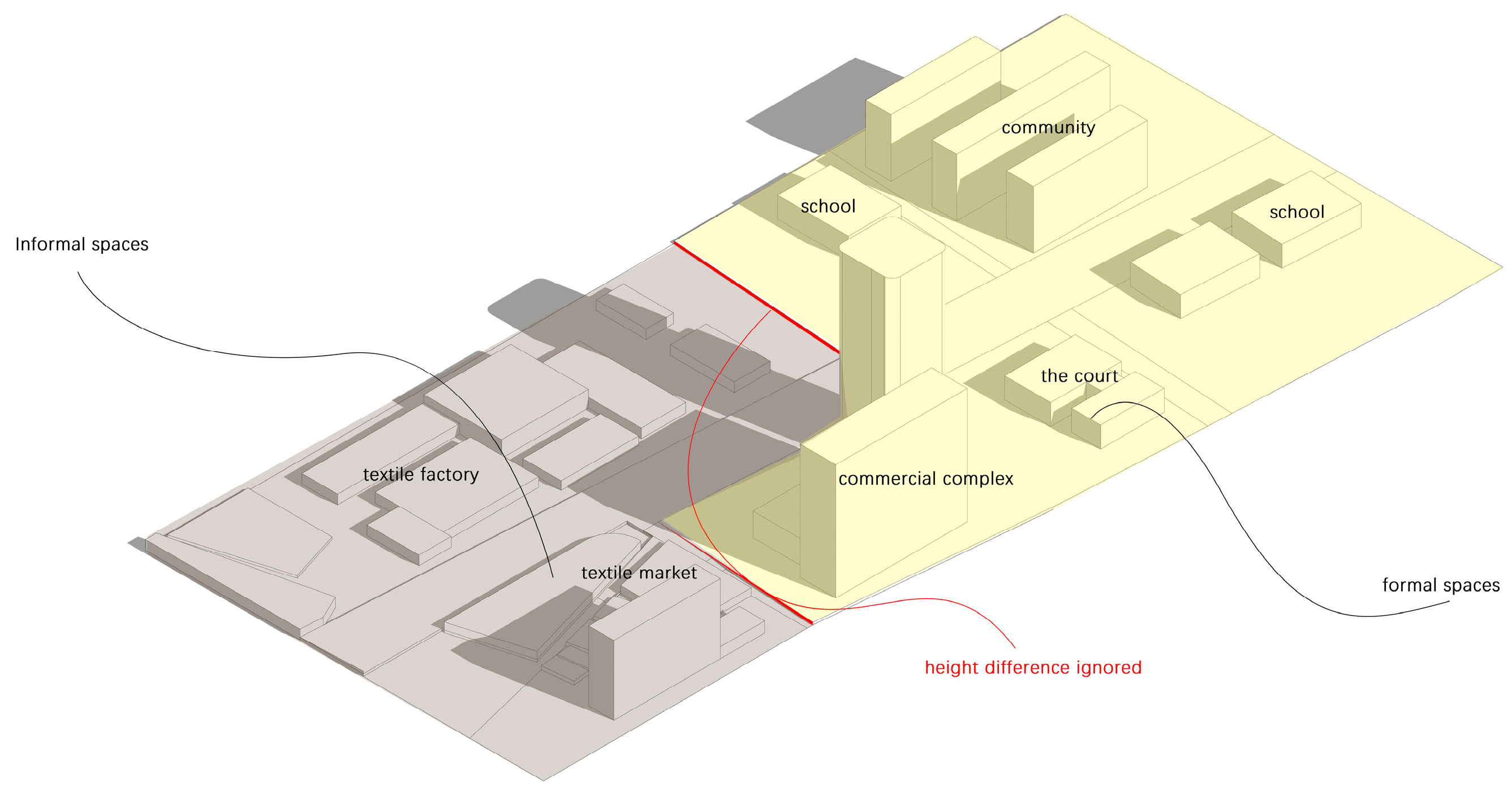

Field investigations revealed that the pathways of individuals within a one-kilometre radius often intersect between formal and informal urban areas, with a 2 m elevation difference between these two city regions, as shown in

Figure 7. For instance, tracking the case of a stall owner revealed that their residential community, situated in what is conventionally considered formal urban planning, contrasts starkly with their shop located within the chaotic environment of Zhongda Textile City. Such elevation disparities undoubtedly contribute to the fragmentation of urban spaces and significantly exacerbate traffic congestion. However, for reasons unknown, this elevation difference was entirely overlooked in the latest urban development plans of 2023.

Specifically, to the east of the elevation difference lies the newly planned formal zone by the government, comprising commercial complexes, courts, schools, and residential communities, among other amenities. Meanwhile, to the west of this elevation difference lies the informal zone where textile industries congregate, including textile factories and markets.

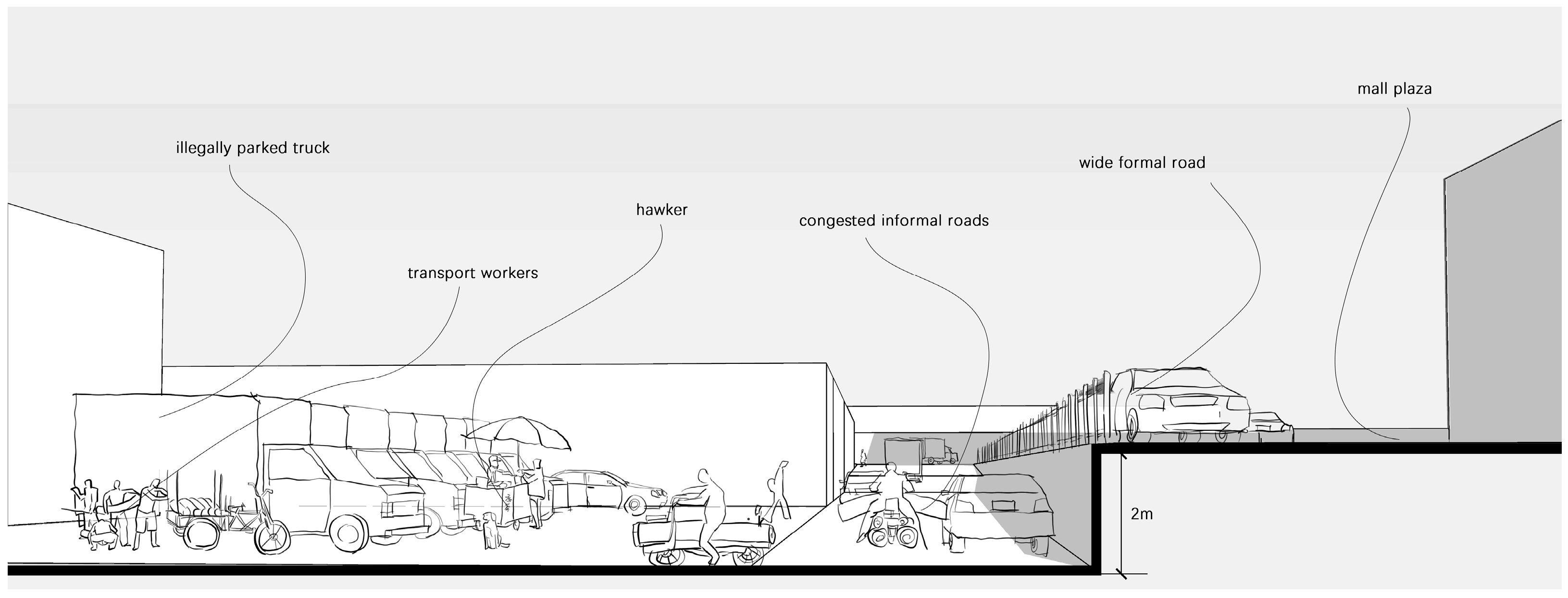

The road we investigated, situated at the boundary between formal and informal areas, exhibits a surprising duality, as depicted in

Figure 8. On one hand, facilities such as commercial complexes, courts, and schools within the formal zone appear splendid, boasting standard wide driveways and spacious plaza areas, yet they are sparsely frequented. On the other hand, areas closer to the informal zone, such as textile factories and markets, present a starkly different scene. In front of the shops, trucks are illegally parked, workers are busy unloading goods, and retail vendors sell beverages such as iced tea. The narrow road is filled with large trucks, private cars that have strayed off course, and various types of electric vehicles, all vying for limited passage space, leading to extremely hazardous traffic conditions.

The two-meter height difference not only symbolizes a clear urban spatial divide but also exacerbates traffic congestion, imposing immense pressure on pedestrians and cyclists at lower elevations. Through interviews with textile stall owners and transport workers, we gained further insight into their dissatisfaction and experiences with such urban planning.

Textile stall owner A: “The new area feels like climbing a cliff. We’re too busy to go there. Tall buildings block sunlight, my shop used to bask in sunlight, but now it feels like we’re forgotten, affecting my business.”

Transport worker A: “I ride my electric bike every day for deliveries, and that two-meter height difference is like a mountain. The roads in the market are already narrow, and with those tall buildings squeezing, delivering goods down here is a real challenge.

Transport worker B: “After years in the market, we still can’t access decent public spaces. We’re on the city’s fringe, left out by new developments.”

Transport worker C: “It feels like we’ve been cut off from that world over there. We too yearn for a better environment, but it seems that it’s constructed for the wealthy, disconnected from us who toil away. To us ordinary folks, venturing over there feels superfluous.”

This segregation between formal and informal spaces on a physical level is caused by the complete neglect and displacement of informal populations during urban planning. For those engaged in informal employment, living amidst busyness and disorder, this has created an insurmountable barrier. Rather than improving their lives, it has exacerbated the condition of traffic congestion. They often choose to avoid these disparities, congregating in the open spaces of informal areas rather than moving into so-called public spaces for activities. This reflects a profound phenomenon of social stratification.

3.3. Analysis of the Pathways Within a 2-km Activity Radius

In exploring the spatial layout and population pathways within a two-kilometre activity radius, we initially employed Spatial Syntax techniques to analyse the road selection and integration within the area, as shown in

Figure 9. Ruikang Road and Yijing Road, as the main roads at the centre of the site, exhibit the highest integration and choice. Based on field observations, these two roads play a crucial role for both the population within the area and those outside it. For instance, for local renovation workers and professional transport workers, these roads serve as vital channels for their daily commuting and cargo transportation. Conversely, for taxi drivers from outside the area, these two roads, traversing the site from east to west and north to south, often become routes they are reluctant to take but must pass through.

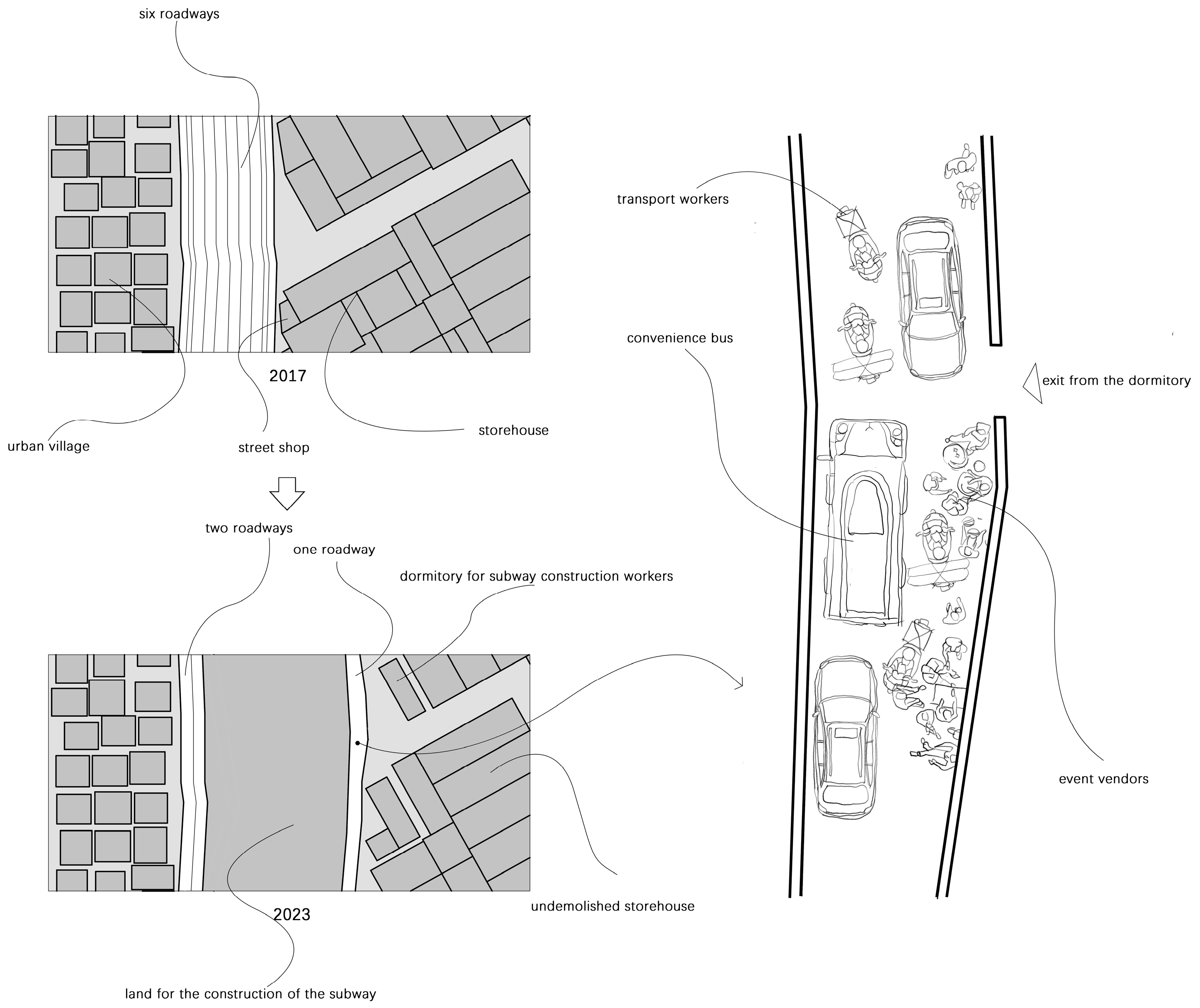

The width and traffic efficiency of Ruikang Road and Yijing Road have been greatly impacted since 2019 when they were commandeered for subway construction. Before the subway was built, Ruikang Road was a broad six-lane urban street that could handle both outside traffic and the varied travel requirements of the local transportation options. However, a large portion of the road was taken up by open excavation while the subway was being built. As a result, as shown in

Figure 10, only two lanes were left on the west side of the old Ruikang Road and only one lane’s width of road was left on the east side.

Through observation during peak operating hours of the market, we found a significant increase in congestion on Ruikang Road. In addition to negatively impacting the Zhongda Textile City area’s operational effectiveness and the standard of living of its neighbours, the encroachment caused by subway construction also breaks the area’s connection to the outside world, turning it into an isolated region inside the city.

A two-dimensional morphological study was conducted on selected nodes located on the east side of Ruikang Road. It can be observed that, on this road, which is only about the width of one vehicle lane, there is not only traffic moving in opposite directions but also a substantial presence of other informal activities, as shown in

Figure 10. Because the east side of the road stands for dorms for subway construction workers, the heat demands that they have access to extra food and drinks, such as herbal tea. As a result, improvised stands selling goods have appeared, making the already narrow route much more claustrophobic. Additionally, there are shuttle buses and tricycles hurriedly transporting goods along this road. We have traversed this road on foot, witnessing scenes of peril: private cars must stop in the slightly wider sections of the road to wait for the minibuses to pass before they have to contend with electric scooters vying for space to continue travelling along the single lane.

During the interview and investigation process, we obtained insights from various stakeholders:

Taxi drivers vented their annoyance by saying, “I have to take a detour every time when I need to cross this area, because Ruikang Road is always congested. It’s a nightmare, there is just too many people.”

An experienced transport worker related his experience: “It feels like an obstacle course every day delivering goods on these roads. To prevent accidents with other cars or sellers, you must always be alert.”

Concerns were also raised by locals: “The road in front of our house is constantly congested, the subway construction keeps taking longer than expected, and the noise really disturbs our rest. All we can hope for is a safe journey home. We now feel apprehensive about returning home because the driver constantly appears impatient when we take a taxi.”

The interviews showcase the significant effects of subway construction on the lives of local and non-local people, particularly those who depend on these primary thoroughfares for their everyday activities and means of subsistence. However, despite the inconvenience brought by the subway construction, which has turned the area into an urban enclave, the construction timeline continues to be repeatedly delayed. Interviews and associated documentation indicate that the government had maintained, since 2020, that the subway project would be finished by the year’s end. However, as of 2023, during our on-site research, inquiries to the supervisor of the subway construction revealed that there is still no hope of completing the subway construction within the next year. This implies that the local populace will have to put up with the mayhem caused by urban development encroaching on their dwelling area for at least the upcoming year.

In conclusion, the population’s activity paths within a 2000 m radius demonstrate the necessity of widening and clearly demarcating lanes on urban roadways in industrial districts where individual transportation is the primary form of transportation. It also highlights the effects of urban development initiatives, particularly major infrastructure projects, on social life and transportation in the area, with a focus on the disturbance of daily life for locals and the detrimental effects on the continuity and openness of the city.

3.4. Analysis of the Pathways Within a 5 km Activity Radius

Using Spatial Syntax, we conducted an analysis of the road network within a five-kilometre activity radius, as shown in

Figure 11. Considering the expanded radius scale, we extended the analysis from the Central Textile Commercial Circle area to the Haizhu District of Guangzhou City. Concurrently, we reduced the road network within the Central Textile area to ensure consistency in road selection criteria. From an urban scale analysis of the Haizhu District, it is evident that the four major city thoroughfares surrounding the Zhongda Textile City exhibit markedly high levels of integration and choice. This indicates the area’s importance as a central hub within the Haizhu District and may help explain the perennial traffic congestion in the vicinity.

We conducted a life history survey on individuals within a five-kilometre radius or more of the Zhongda market area. For this demographic, their activity trajectories extend beyond the boundaries of the Zhongda fabric market area, intersecting with external regions such as the Shahe wholesale market, revealing a complex network of economic interactions. Such extensive commercial activities highlight the reliance on efficient logistics and transportation systems. The large textile trading centre within the Zhongda Textile Market serves not only as a venue for commercial transactions but also as the core of economic and transportation activities in the area. Therefore, we selected one of the large textile trading centres within the region as the focal point for morphological analysis.

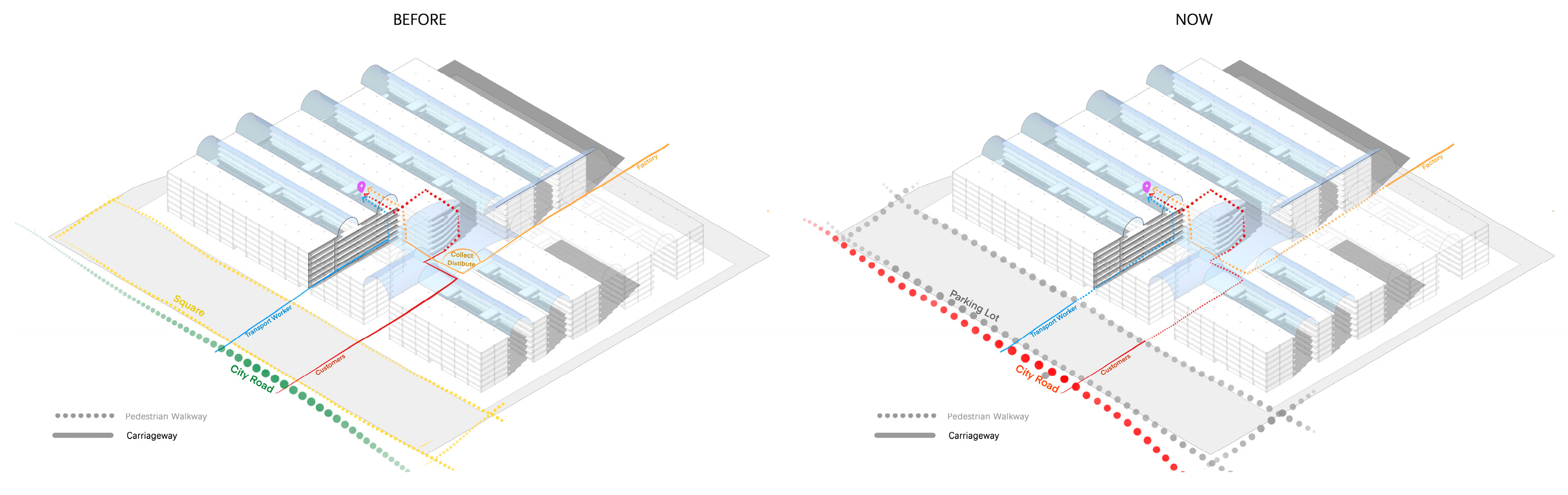

Mapping and surveying the Zhongda textile trading city, a morphological analysis reveals the characteristics and changes of the internal roads within the building, effectively reflecting the unique industrial traits of the market as well as the negative impacts of policy changes on these traits.

The primary goal of the Zhongda textile trading city’s architectural design is great efficiency, which is strongly related to a deep comprehension of the particular requirements of the textile sector. The mall is made up of two main structures: a row of long, enclosed buildings and the glass-ceilinged interior lanes that connect them. Two specific needs of the textile industry are taken into account in this design: first, a lot of street-facing storefronts are needed to support a sales model that is dominated by small retailers; second, an unobstructed internal road system is needed to facilitate the transportation of textile products. In the original operating model of the mall, clothing store owners could drive directly to the centre of the building, easily walk into shops to make their selections, and quickly summon transport workers to deliver the goods to a specified location after purchasing. Furthermore, the restocking procedure is just as efficient, since employees may drive electric cars or tricycles straight from factories to the mall’s distribution centre and then easily deliver the goods to different retailers. Despite the seemingly chaotic flow of people and logistics within the mall, which appears disorderly at first glance, there is actually a high degree of organization and efficiency. Despite the lack of cohesive planning, every submarket has an internal road structure with a distinct hierarchy that forms a regular grid of roadways to facilitate intentional and effective purchase activities. Within such a configuration, the dwell time of transportation vehicles is significantly reduced, consequently leading to a substantial increase in the efficiency of goods transportation. The mall’s entrance plaza and the surrounding areas are solely utilized for transit; they are never occupied for an extended period of time. The state of the city’s road traffic is relatively good.

However, the implementation of the Type-5 Vehicle Management policy in 2012 changed everything. Small tricycles and electric vehicles were not allowed within the market due to the restriction, which forced employees of clothing stores, transit workers, and shop owners to park their cars in plazas or other public areas outside the mall. Then, in order to deliver items to designated stores, they had to make their way through the interior of the market using manual pushcarts. This shift not only drastically decreased the industry’s operational efficiency but also resulted in a huge number of cars occupying the public areas surrounding the mall, as seen in

Figure 12, which led to chaotic parking situations and even frequent traffic jams on municipal roadways.

Many stakeholders voiced discontent with the policy in surveys and interviews:

Own A: “Our market used to be the busiest, but ever since this policy was introduced, look around, it’s empty. The big bosses are no longer willing to come here; they find it too troublesome. You could say this market has been completely ruined.”

Transport Worker B: “It’s much more exhausting now, pushing carts every day. Previously, we could drive electric cars up to the stores. We now have to walk around pushing the fabric. In addition, my revenue has decreased, deliveries are taking longer, and the task is harder.”

The Textile Trading City’s architecture is dedicated to maximum efficiency and reflects a thorough comprehension of the transportation requirements of the textile sector. Through internal logistical corridors and an efficient shop structure, it facilitates quick commodities rotation. Initially, despite its seemingly complex surface traffic conditions, there was order in the chaos. The market’s means of transportation was forced to shift by the Type-5 Vehicle Management Policy, which had an impact on its operational effectiveness and put more strain on the nearby public areas.

Finally, the analysis of activity radii, as summarized in

Figure 13, clearly shows the characteristics of informal spontaneous activities within the study area, the content of formal urban practices, and the conflicts between the two. The comparison reveals that different radii highlight various aspects of the obstacles faced by informal transportation. The 200 m radius illustrates the traffic challenges arising from the high-density coexistence of industry and residential areas within urban villages. The 1 km radius highlights the transportation difficulties caused by the spatial segregation between formal urban areas and informal settlements. The 2 km radius demonstrates how new urban infrastructure projects, such as subway construction, have led to the prolonged occupation of informal transport routes, exacerbating traffic issues. Finally, the 5 km radius reflects how government policies, which fail to accommodate the needs of informal transportation, contribute to mobility challenges.

4. Discussion

Guangzhou, like many other East Asian cities, is a fast-rising metropolis that is changing on many fronts [

48]. In our research, we focused on the traffic congestion around Asia’s largest textile mall and the typical informal residential areas within the city, known as “urban villages,” in Guangzhou. This allowed us to rethink the relationship between formal and informal spaces. This study is beneficial for a deep analysis of the internal development logic of informal spaces, examining the activity paths and needs of people associated with these spaces and the impact of urban practices on them. Although the conclusions drawn from case studies do not reveal the full picture of urban operations in informal areas, our research primarily uncovers the particularities of the case studies, including social, political, and economic backgrounds, activity paths of people in informal spaces, and urban morphological characteristics, thus making a significant contribution to the knowledge of informal urban spaces in the East Asian region.

It can be observed that within certain informal spaces, the movement is not as randomly chaotic as it superficially appears. Instead, it is the result of careful and resource-intensive guidance and coordination of labour and resources by insiders. This dynamic illustrates the spontaneous characteristics and demands of industry-led informal activities, which are primarily expressed in the pursuit of compact living patterns, strong demand for concentrated industrial land, and brief commutes. Additionally, these areas feature high-density business activities and traffic flows, utilizing a variety of flexible transportation modes on both formal and informal roads for the transport of people and goods. The pursuit of efficient goods transportation and sales activities further defines the region. These practices can be summarized by three main characteristics: a clear division of social labour, high traffic efficiency, and a high-density concentration of resources. These features are evident in our research, such as in studies dominated by a 200 m activity radius showing the compact living circles of factory workers and an integrated industrial model of production and sales. The global success of Zhongda Textile City also proves the efficiency of this spontaneously formed operational system.

However, despite the high local efficiency, we must confront the overall condition of traffic congestion throughout the region, as well as the segregation of informal spaces from other urban areas. It is found that informal areas, in the process of spontaneous formation, are affected by the historical legacy of urban spatial patterns and developmental changes in the pursuit of high density and high efficiency, presenting a chaotic surface situation, which is further exacerbated by the neglect and encroachment of the formal urbanization practices that are supposed to be optimized and governed by them.

This is manifested in four main ways: (1) a mismatch between city planning and the demands of informal spaces, (2) a physical divide between formal and informal areas, (3) prolonged occupation of informal spaces by urban infrastructure development, and (4) policy formulation ignoring existing experiences. In conclusion, the primary cause of traffic congestion in the research area is mostly due to the inconsistency between the practices of urban morphological upgrading and the spontaneous adaptations of informal settings.

The informal spaces in our case study serve as excellent examples of the essential qualities that define the term “informal space”, including dynamism, fluidity, temporariness, recyclability, and reversibility [

49]. Its process of development follows principles such as spontaneity and self-organization in modelling, occupying and generating space, as our investigation found many garment factory workers spontaneously configure extensive privatization of their living and working spaces as well as the surrounding road space. In contrast, formal planning processes within the study site provide precise rules and directions for the construction of territories, such as the overall layout of the textile market and the planning policy settings related to access. Lefebvre H refers to the fact that the new social reality resulting from the coexistence of these two ways of structuring space is based neither on the formal nor on the informal but on their dialectical relationship in space [

50]. In other words, the quality of the interaction between the two spatial concepts—rather than a single formal or informal process—determines the successful output of urban spatial planning and design procedures [

51,

52]. Informality is an organizing logic that can only develop in the presence of rules or formal structures that facilitate its success [

53,

54]. The relationship between formality and informality is expressed through interaction.

In our study, there is a dichotomy between formal and informal spaces, and the two types of spaces on the site are in a state of imbalance due to government initiatives that are partly motivated by development. On one hand, the government hopes to transform and upgrade urban forms, such as constructing subways, planning new industrial zones, and building large-scale commercial facilities and schools in the surrounding areas, as well as establishing a regulatory system for the entry and exit of Type-5 vehicles in the textile market, aimed at restructuring and regulating informal spaces. On the other hand, due to the industry operating norms that have spontaneously formed over a long period at the medium-to-large textile markets, and the inertia in urban spatial configuration, the region’s informal workforce has its own unique demands on urban space. The market’s position in the global economy makes any changes almost impossible. The conflict between formal and informal sectors thus leads to competition and contention over space by different groups and activities. Essentially, this is a matter of inequality in power and resources. There exists a certain gap between spatial allocation and actual space occupation.

Our research highlights the impact of conflicts between formal and informal spaces on traffic congestion and how these conflicts deepen urban spatial divisions. To promote more inclusive urban governance, we suggest the following two strategies:

(1) Understanding and Addressing Power Inequalities: Focus on the conflicts and inequalities within formal and informal power structures, recognizing and supporting the needs of marginalized groups to safeguard their interests. Urban planning departments should respect the rights of informal populations to equal use of urban spaces. New urban plans should honour the spontaneous characteristics of existing setups, avoiding long-term occupation of existing spaces and designing reasonable buffer zones to reduce fragmentation between informal spaces and other urban areas.

(2) Enhancing Intersectoral Collaboration: Urban governance should encourage cooperation among different stakeholders, including government agencies, non-governmental organizations, the informally employed, and social movement groups. Joint development of policies and planning interventions that affect informal vendors should ensure that existing social experiences and industry needs are reflected in policies, achieving broader consensus and participation.

While there is no direct method to fundamentally resolve the issue of unequal governance relationships in informal spaces, pursuing an inclusive agenda that incorporates these two governance elements may be a good starting point.