A Study on the Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

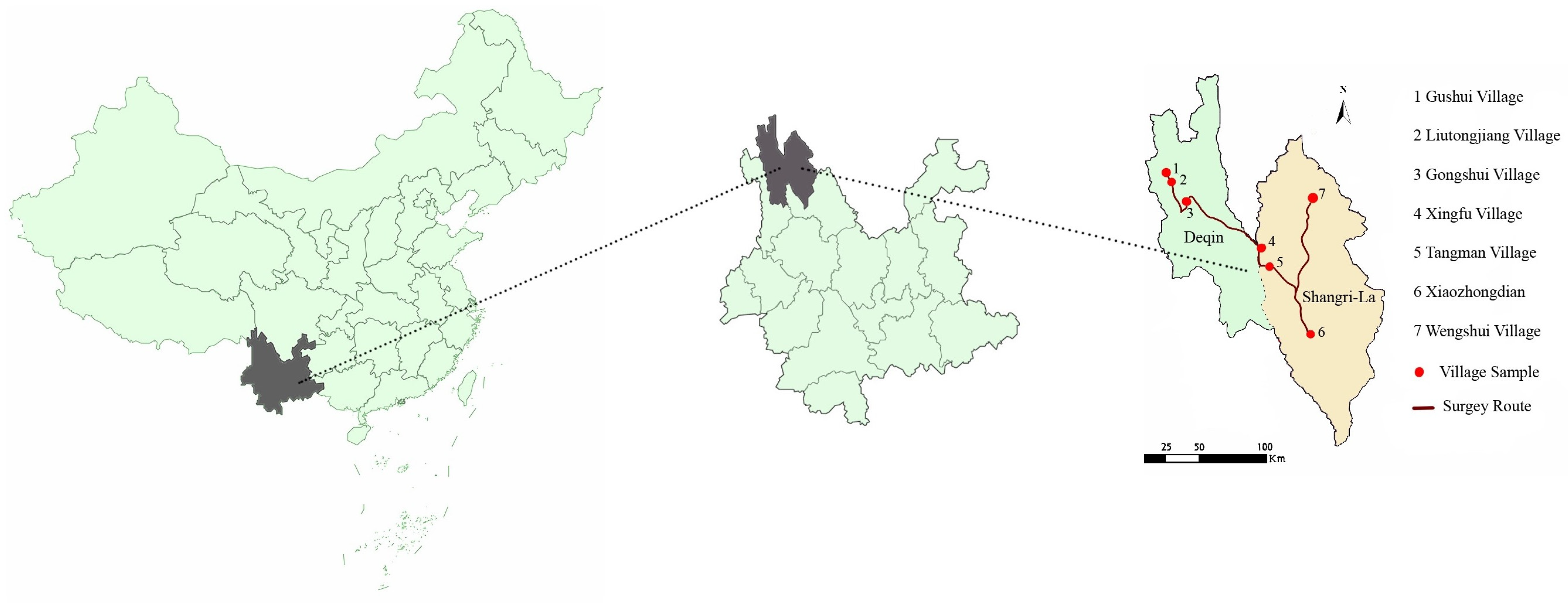

2. Research Area, Object, and Methodology

2.1. Survey Area

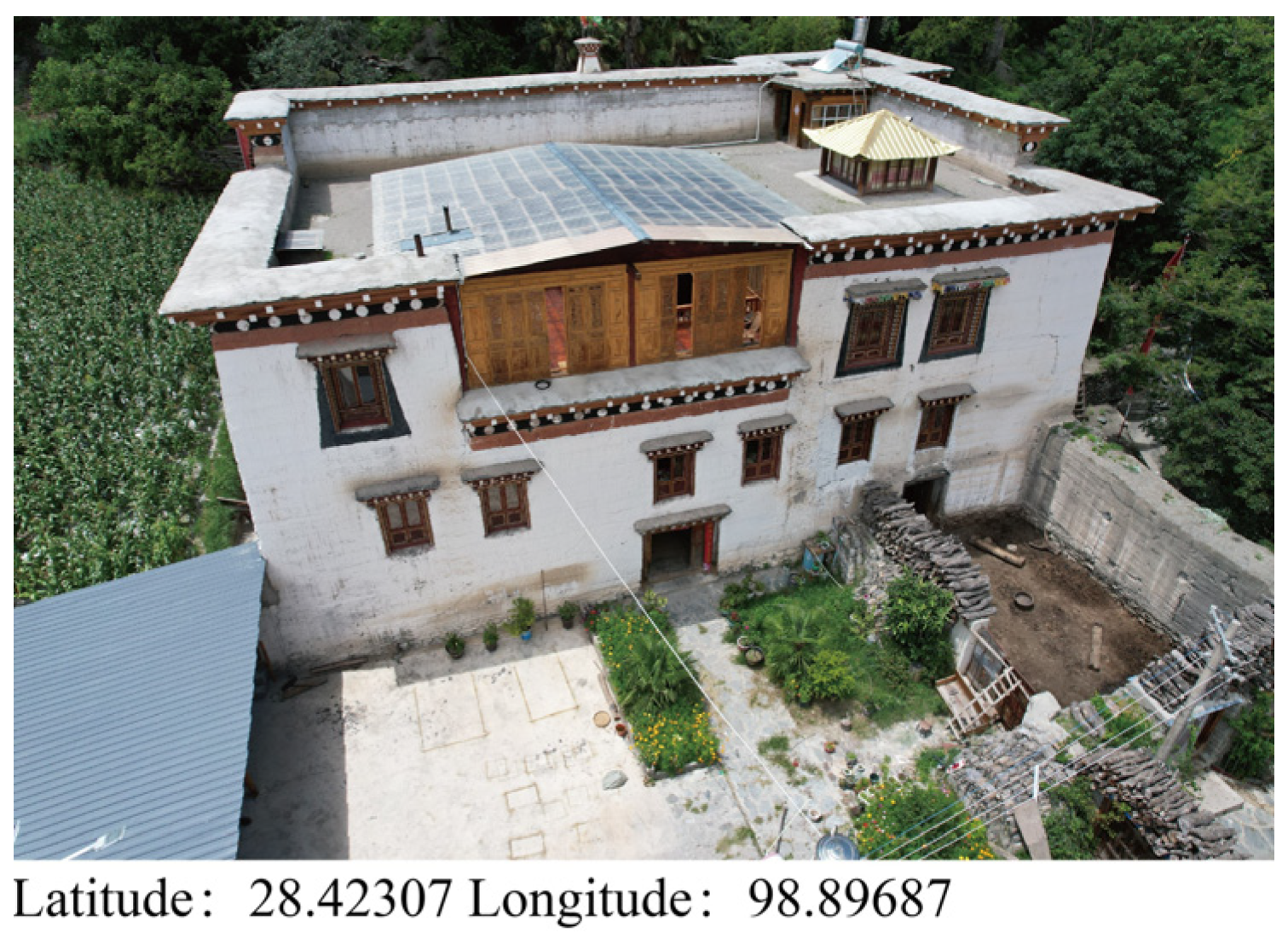

2.2. Survey Samples

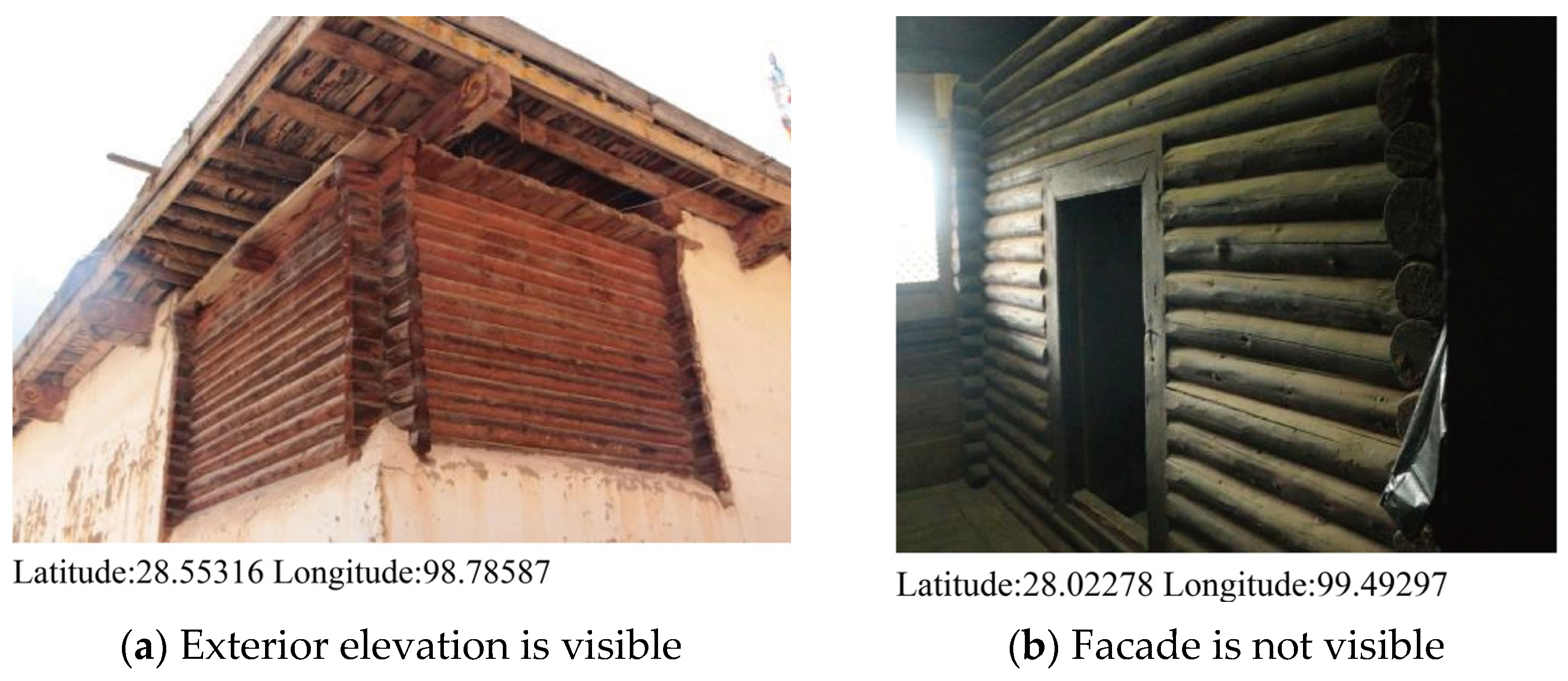

2.3. Survey Methodology

3. The Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region

3.1. The Settlement and Site Selection Characteristics

3.1.1. Type of Settlement

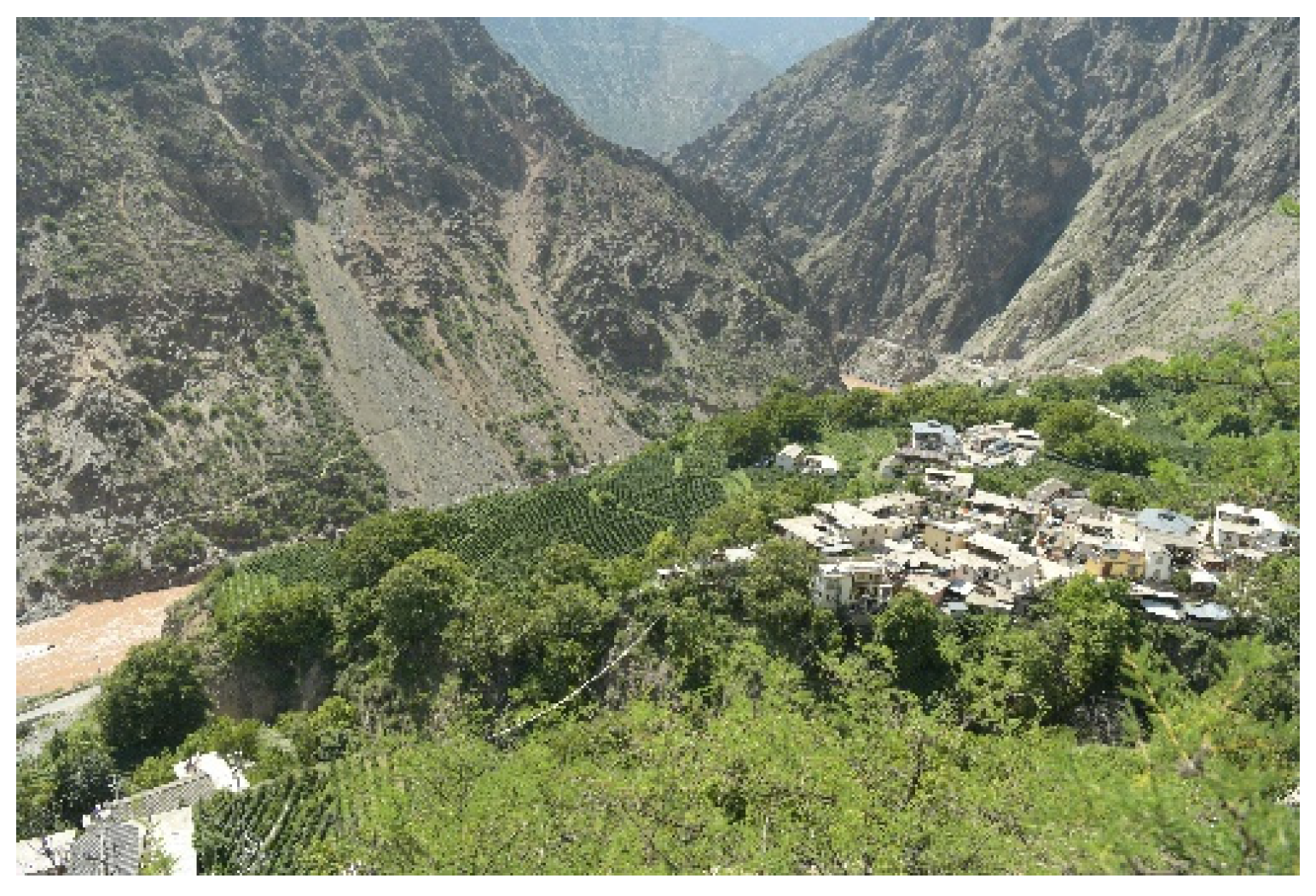

Mountain Settlements

Valley Settlements

Plant Land Settlements

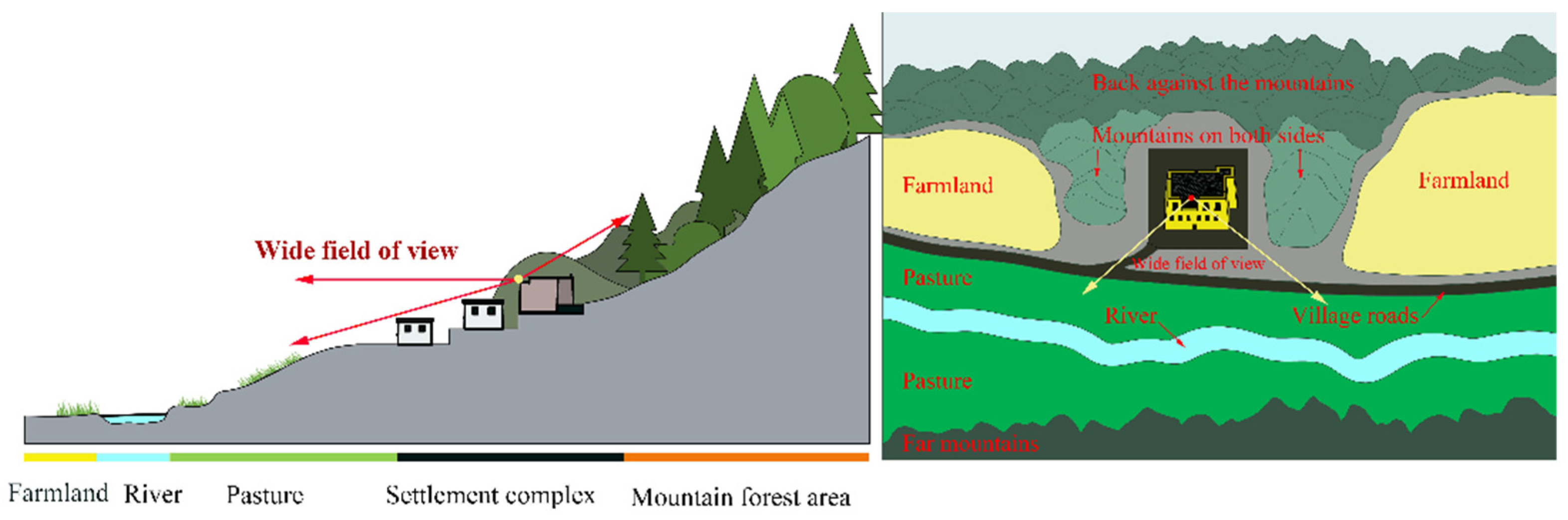

3.1.2. Site Selection Characteristics

Security and Defense

Solid Foundation

Ecological Adaptation to the Environment

3.2. Spatial and Functional Characteristics of Tusi Manor Architecture in the Yunnan–Tibet Region

3.2.1. Courtyard Layout

3.2.2. Building Type

- (1)

- Flat-roofed Tusi manor

- (2)

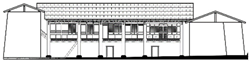

- Sloped-roofed Tusi manor

3.2.3. Formal Characteristics

Planar Feature

- (1)

- Concave-shaped layout

- (2)

- “U”-shaped layout

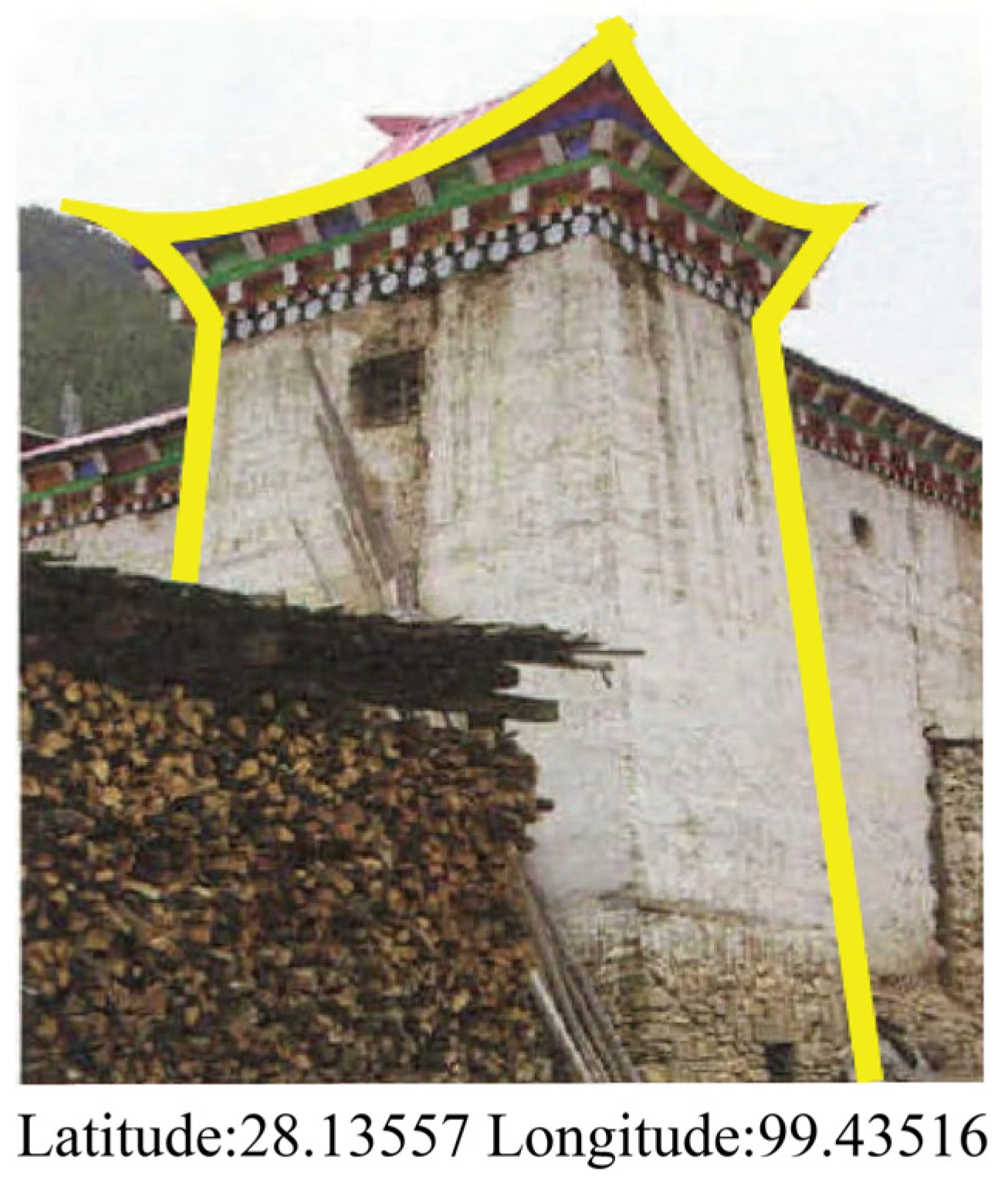

Elevation Features

- (1)

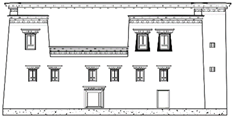

- Main facade—Front facade

- (2)

- Secondary elevations

3.2.4. Functional System

Administrative Functions

Faith and Folklore Functions

Residential Functions

Security Defense Functions

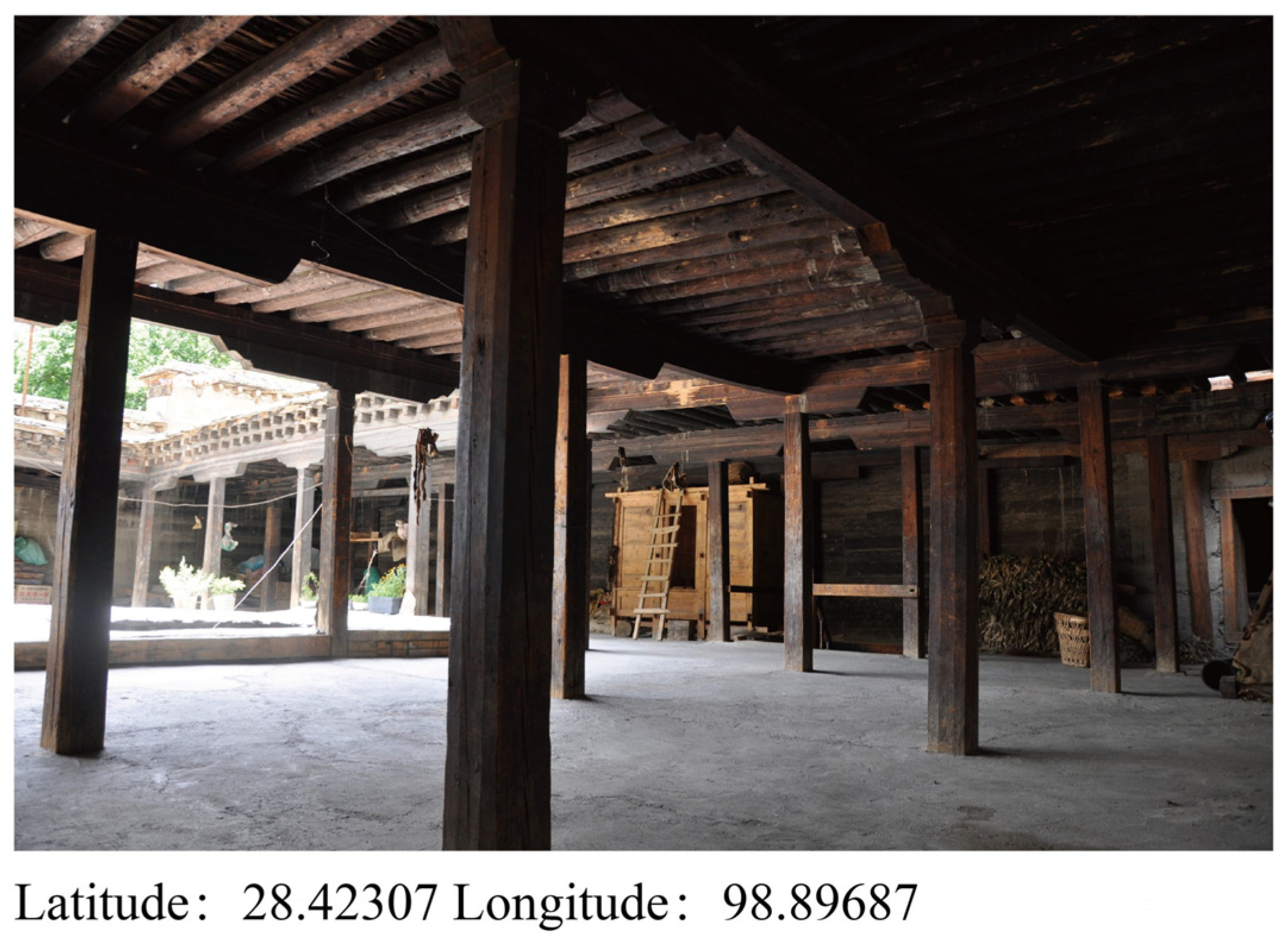

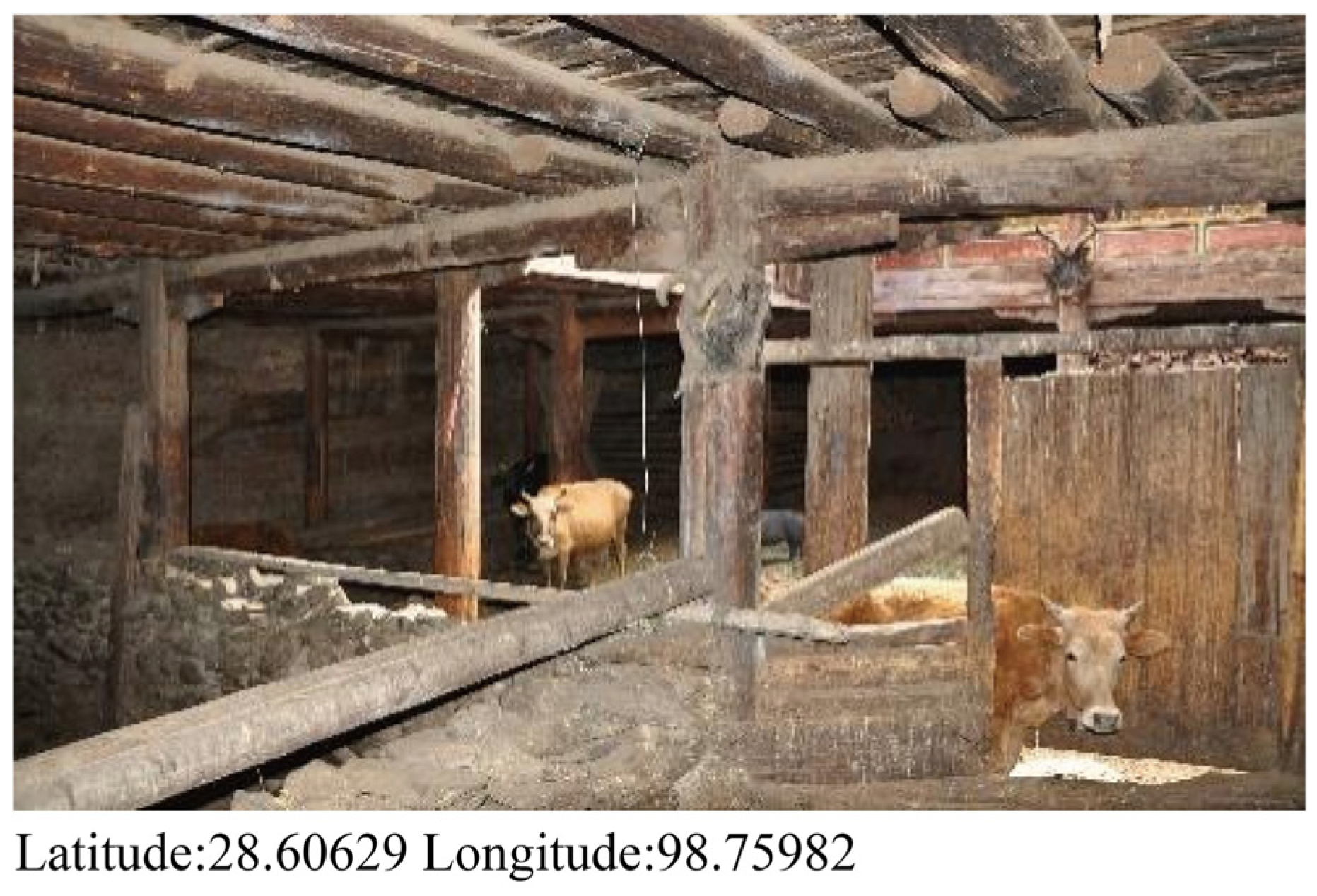

Captive Livestock

3.2.5. Spatial Layout

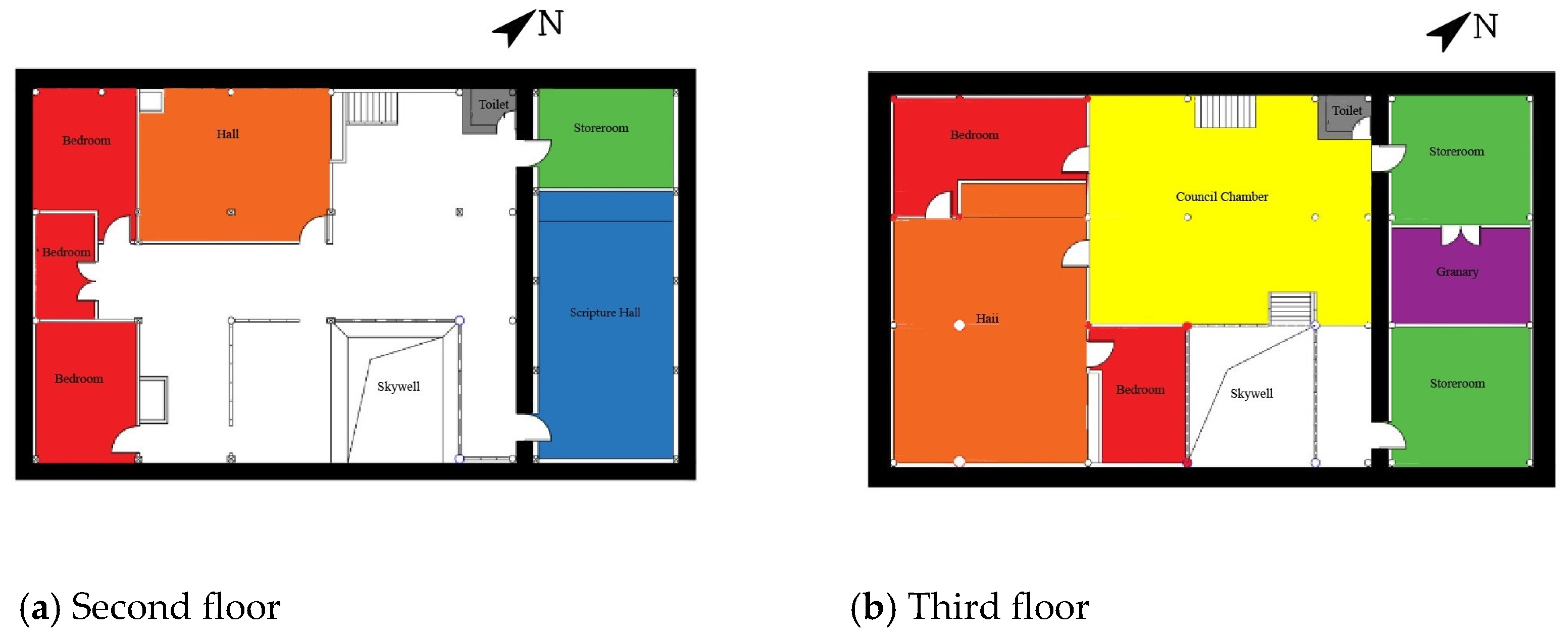

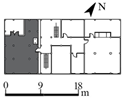

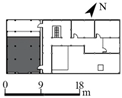

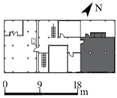

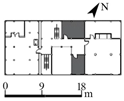

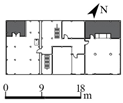

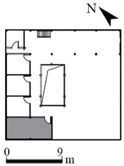

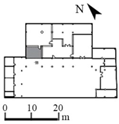

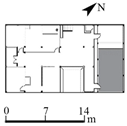

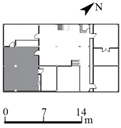

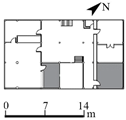

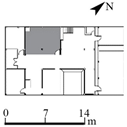

Indoor Functional Distribution

Indoor Functional Space Analysis

- (1)

- Faith and Folklore Space I: Scripture Hall

- (2)

- Faith and Folklore Space II: Hall

- (3)

- Council Chamber

- (4)

- Bedroom

- (5)

- Secret room

- (6)

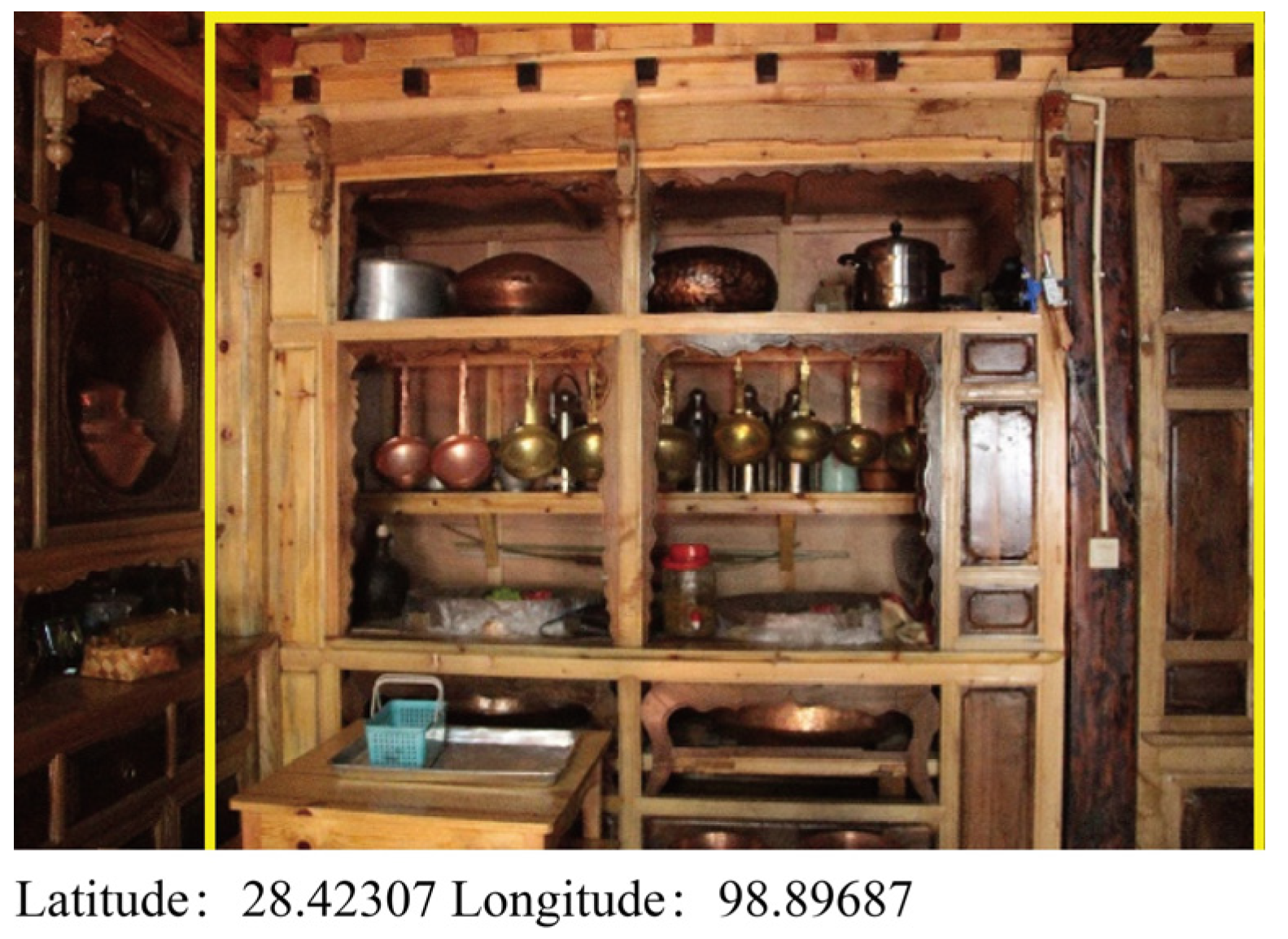

- Storeroom

- (7)

- Staircases and corridors

4. Architectural Characteristics Analysis of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region

4.1. Adaptation to the Natural Environment

4.2. Dominance of Tibetan Culture

4.3. The Influence of the Tusi System

4.4. Multiculturalism

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, B.J. Chinese Ancient Architectural Wooden Construction Techniques, 2nd ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ghad, M.; Hadeer, A. Rehabilitation of Mounemantal, Historical, and Traditional Buildings. J. Eng. 2015, 3, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Imtiaz, S.; Arif, S.; Nawaz, A.; Shah, S.A.R. Conservation of Socio-Religious Historic Buildings: A Case Study of Shah Yousuf Gardez Shrine. Buildings 2024, 14, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.C. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y.; Nakatani, N. Historic conservation in Tibetan region amidst rapid urbanization: A case study of Dukezong Old Town. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2023, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ashish Ganju, M.N. Documentation and conservation of vernacular architecture: Conservation and continuity. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Nong, Z.; Liu, H. Mechanical Performance Degradation of Decaying Straight Mortise and Tenon Joints: Tusi Manor, Yunnan-Tibet Region. Forests 2024, 15, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Su, Y.; Qiang, M. A study on the Atlas and Influencing Factors of Architectural Color Paintings in Tibetan Timber Dwellings in Yunnan. Buildings 2024, 14, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. China’s Tusi System; Nationalities Publishing House: Kunming, China, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Nong, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, K.; Yin, M.; Yuan, Z.; Su, Y.; Qiang, M. Degradation of Mechanical performance of Hoop Head Tenon-Mortise Joint of Tusi Manor with decay disease in Tibetan areas in Yunnan. Buildings 2024, 14, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Study on the Ethnic Characteristics of Architecture in the Bozhou Tusi System. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2014, 23, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.P.; Dong, S.W. Architectural Art and Cultural Connotation of the Mo Tusi in Xincheng. Lit. Artist. Debates 2010, 2, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Spatial Layout and Structural Analysis of Tangya Tusi Royal City Ruins. Sanxia Forum 2013, 5, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Xu, Z.; Guo, J. Analysis of the Spatial Layout and Stylistic Characteristics of Guizhou Tusi Architecture. Shanxi Archit. 2021, 47, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.W. A Study on the Tusi-Style Architecture of the Handong School: A Case Study of the Local Construction Techniques of Tusi Architecture in Guizhou Province. Ph.D. Thesis, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, Y. Tracing the Evolution of Tusi Architectural Timber Frameworks Based on the “Yingzao Fashi”: A Case Study of the Patriarch Temple in Laosicheng. Decoration 2023, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Qiao, X.; Liu, J. Reconstruction Study of the Administrative Building Area in Yongshun Laosicheng Tusi Site: Based on the Construction of Architectural Group Hierarchy. Archit. J. 2023, 1, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, X. Research on the Protection and Reuse Design of the Qiaojia Ado Tusi Mansion Ruins. Archit. Cult. 2022, 12, 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.Y. The Crystallization of Two Cultures: Tibetan Dwellings in Zhongdian, Yunnan. Cent. China Archit. 1998, 4, 135–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F. A Study on the Architecture of Yunnan Tusi Mansions. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G. A Study on the Architectural Forms and Cultural Connotations of Yunnan Tusi Government Offices: Taking Nandian and Menglian Xuanfusi as Examples. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Shu, L. Analysis of the Architecture and Cultural Connotations of Dai Tusi Government Offices: A Case Study of the Nandian Xuanfusi in Lianghe County, Yunnan Province. Southwest Borderl. Natl. Res. 2009, 6, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, M. Analysis of the Form and Causes of Traditional Tibetan Dwellings in Diqing, Yunnan—A Case Study Based on Field Surveys and Comparative Research in Tangman Village. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2022, 43, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, R.A. Tibetan Civilization; Faber and Faber Ltd.: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Tucci, G. The Religions of Tibet; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, S. Traditions of Appearance: Adaptaion and change in Eastern Tibetan Dwellings. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2003, 15, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Federica, M.M.; Liuhong, V. The Tibetan village of north west Yunnan a basic grammer of local authenticity. Chian Tibetol. 2008, 11, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.Z.; Yang, Y.Z. Regional Architectural Culture of Southwest China; Hubei Education Press: Wuhan, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, X.; Lu, H.; Xia, Q.; Ren, L. Research on the Influence of Tibetan Water Culture on Settlement Space. J. West. China’s Hum. Settl. 2020, 35, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Qiang, M. Analysis of the Characteristics of Timber-Frame Dwellings in Yunnan Tibetan Area. Shanxi Archit. 2014, 40, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.A. Study on the Construction Techniques of Traditional Tibetan “Tu Zhang Diaofang” Dwellings in Northwest Yunnan. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Yingzao Fashi; Huazhong University of Science and Technology: Wuhan, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. History and Culture of Dwellings; South China University of Technology Press: Guangzhou, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q. A Study on Tibetan Vernacular Architecture and Its Cultural Connotations. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. A Study on Tibetan Dwellings from the Perspective of “Religion—Belief”. J. Guizhou Natl. Stud. 2019, 40, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Research on the Interior Spatial Structure of Tibetan Dwellings in Shangri-La, Yunnan. Art Res. 2019, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, G. Ethnic Housing Forms and Culture in Yunnan; Yunnan University Press: Kunming, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Ning, Z. Analysis of the Relationship between “Regional Advantages” and “Ethnic Aggregation” in the Residential Architecture of Tusi in Northwest Yunnan. Resid. Quart. 2016, 5, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, H. Study on the Architectural Culture of Tibetan People’s Residence. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y. Study on the Form Characteristics and Structural Mechanical Properties of Tusi Manor in Yunan-Tibet Region. Ph.D. Thesis, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Lu, H.; Xu, L. Application of artificial intelligence technology and virtual reality technology in building energy conservation. Green Constr. Intell. Build. 2025, 1, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

| Courtyard Layout | Characteristics | Courtyard Layout Form | Legend |

|---|---|---|---|

| The main building enclosed by courtyard walls | The main rectangular structure is enclosed by irregularly shaped courtyard walls. Key features include the integration of the courtyard walls with the building’s rammed earth walls, forming a roughly square-like (“kou”-shaped) courtyard layout, with the main gate positioned on the side of the courtyard. |  |  |

| The main building enclosed by side rooms and courtyard walls | The overall architecture is arranged in a “U” shape, with a rectangular main building facing forward and two side rooms distributed on the left and right. These side rooms were historically used as living quarters for the Tusi and monastic cells. The courtyard features a relatively regular square layout, with the main gate positioned on one side of the courtyard wall. |  |  |

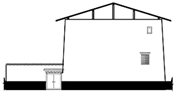

| Form | Characteristics | Pictures of Tusi Manor | Elevation Drawing of Tusi Manor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concave shape | The skywell connects various functional spaces within the building, and the main elevation of the building presents a concave shape. |  |  |

| The second and third floors are set back to form a skywell, around which the building creates an incomplete corridor. The main elevation of the building presents a concave shape, forming a semi-open space. |  |  | |

| It is enclosed by two individual structures (left- and right-wing rooms) and the courtyard walls, with the main elevation of the building presenting a concave shape. |  |  | |

| L-shaped | The architectural form is a setback style, with the exterior facade presenting an L-shaped elevation. |  |  |

| L-shaped variation | The architectural form is a multi-level setback style, presenting an L-shaped variation in its elevation. |  |  |

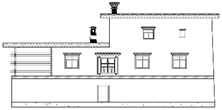

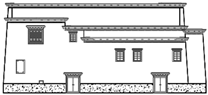

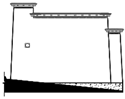

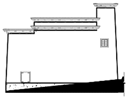

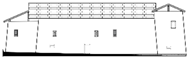

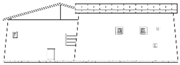

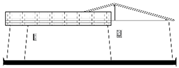

| Sample Name | Rear Elevation | Left Elevation | Right Elevation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xingfu Tusi Manor |  |  |  |

| Tangman Tusi Manor |  |  |  |

| Xiaozhongdian Tusi Manor |  |  |  |

| Sample Name | Building Width L (Meter) | First Floor Height H1 (Meter) | Second Floor Height H2 (Meter) | Third Floor Height H3 (Meter) | Building Total Height H4 (Meter) | H1/L | H2/L | H3/L | H4/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gongshui Tusi Manor | 27.4 | 2.5 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 12.9 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| Liutongjiang Tusi Manor | 18.8 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 8.4 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.45 |

| Gushui Tusi Manor | 20.7 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 8.9 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

| Xiaozhongdian Tusi Manor | 38.9 | 2.4 | 3.0 | / | 8.7 | 0.06 | 0.08 | / | 0.22 |

| Xingfu Tusi Manor | 28.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 10.5 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.37 |

| Tangman Tusi Manor | 21.1 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 9.4 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.45 |

| Sample Name | Building Width L (m) | Door Width L1 (m) | Window Width (Second Floor) L2 (m) | Window Width (Third Floor) L3 (m) | L1/L | L2/L | L3/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gongshui Tusi Manor | 27.4 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Liutongjiang Tusi Manor | 18.8 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Gushui Tusi Manor | 20.7 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Xiaozhongdian Tusi Manor | 38.9 | 3.2 | 1.0 | / | 0.08 | 0.03 | / |

| Xingfu Tusi Manor | 28.1 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Tangman Tusi Manor | 21.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Example | Council Chamber | Scripture Hall | Hall | Bedroom | Storeroom | Monastic Hall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gushui Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Gongshui Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Xingfu Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Liutong jiang Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Xiao zhongdian Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Tangman Tusi Manor |  |  |  |  |  |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, Y.; Li, M.; Cheng, M.; Qiang, M.; Zhou, X. A Study on the Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region. Buildings 2025, 15, 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071134

Su Y, Li M, Cheng M, Qiang M, Zhou X. A Study on the Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region. Buildings. 2025; 15(7):1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071134

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Yanwei, Man Li, Mengshuai Cheng, Mingli Qiang, and Xuebing Zhou. 2025. "A Study on the Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region" Buildings 15, no. 7: 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071134

APA StyleSu, Y., Li, M., Cheng, M., Qiang, M., & Zhou, X. (2025). A Study on the Architectural Form and Characteristics of Tusi Manors in the Yunnan–Tibet Region. Buildings, 15(7), 1134. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15071134