1. Introduction

Since its formalization within architectural education, the design studio has served as a foundational pedagogical framework, continually evolving through the introduction of diverse approaches and methodologies. Studio teaching practices are continuously examined in terms of the formation, transmission, and experiential nature of educational content, evolving into a diverse and pluralistic field of research [

1]. Alongside advancements in technology, the pursuit of integrated connections between design and research, coupled with the adoption of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary methods, calls for redefining architectural education and the design studio [

2,

3]. With its dynamic and expanding scope, the design studio persistently challenges academic boundaries, extending beyond conventional pedagogical frameworks and fostering innovation in design and research. In this context, the studio’s potential to act as a conduit between academia and practice provides a configurable ground where diverse environments of design research, thinking, and doing/making can converge.

In exploring architectural design studios in terms of the interplay of design and research practices, experience becomes crucial as the primary source of knowledge transmitted, reflected, and created through design. Design studies that provide tangible studio experience play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between conceptual exploration and practical application. Tangible experiences are fundamental in shaping neural foundations that support the development and progression of more abstract learning patterns over time [

4]. Therefore, incorporating material experimentation into architectural design studios becomes a significant focus of research for generating and acquiring knowledge through tangible experiences. A deeper understanding of architecture becomes possible by moving beyond abstract drawings and actively engaging with material properties, construction techniques, and building assemblies [

5]. This underscores the need to critically reassess the role of material experimentation in fostering both representational and non-representational expressions within the studio.

In architectural design studios, design spaces are shaped by networks of mediated and unmediated relations, spanning both material and immaterial realities to produce diverse representational and non-representational expressions. Through the iterative processes of mediation, transfer, and negotiation between mediums such as drawings, models, prototypes, and installations, these spaces foster artistic multiplicity and sensory engagement [

6,

7]. Although design spaces can incorporate diverse mediums, both intangible and tangible, the immersive insights gained through material experimentation establish iterative and meaningful connections with the physical world. In this sense, material experimentation forms the basis for a tangible field of knowledge to shape the complex relationship between design space and architectural space.

Rethinking architectural design studios to incorporate material experimentation brings the dynamic interplay between the designer, material, and artifact into focus [

8]. This engagement fosters design expertise by providing experiential insights into the aesthetic, functional, and structural aspects of buildings while enhancing material understanding and tool proficiency. Moreover, it facilitates interdisciplinary and industrial collaboration, broadening the scope of architectural inquiry [

9] (p. 31). The rise of digital technologies and fabrication practices has transformed architectural design, facilitating the materialization of digital simulations and redefining the architect’s role as a digital artisan. While this shift enhances precision and efficiency, complete reliance on digital methods risks a reductionist approach, limiting diverse perspectives in design. To counter this, hybrid methodologies merging digital and traditional craftsmanship have emerged as a productive middle ground, fostering creativity while preserving craft identity [

10] (pp. 87–92). In this context, it becomes essential to explore studio fictions that equip students with the knowledge and skills to navigate both mediated and unmediated material interactions, allowing them to move beyond the constraints of purely digital craftsmanship and embrace a more integrated approach to design [

11].

As highlighted in the literature of architectural education, Bauhaus’s educational philosophy established the foundation for integrating craft and material studies into design pedagogy, promoting a holistic approach that bridged art, architecture, and technology. This legacy remains influential in contemporary architectural studios, which emphasize interdisciplinary collaboration, material-driven processes, and the integration of theory and practice. Leading institutions such as MIT, the AA School of Architecture, Bartlett, ETH Zurich, TU Delft, RMIT, Columbia GSAPP, Harvard GSD, and SCI-Arc incorporate material experimentation into their pedagogical frameworks, particularly within their design research laboratories. These studios explore advanced methodologies in digital design and fabrication while fostering interdisciplinary connections with fields such as biology, material science, and engineering. Experimental environments like AA Hooke Park, Valladura Lab, and the Valparaiso School of Architecture extend this approach through 1:1 scale application, enabling hands-on material experimentation and the realization of spatial productions. While these practices have advanced practical outcomes and enriched architectural education, there remains a pressing need to further theorize and contextualize the processes underlying experimental approaches. Tools such as installations and prototypes hold significant potential as pedagogical instruments, yet their role in fostering innovative studio practices requires deeper investigation. Furthermore, creating and implementing adaptable studio frameworks that support hands-on experimentation in both advanced and resource-limited settings is crucial for redefining the foundational content of architectural education. Broadening these practices through inclusive and accessible production environments can extend their impact across diverse educational contexts, embedding experimental methodologies as a central pedagogical strategy.

Building on this understanding, this study explores experimental pedagogical fictions and tools aimed at integrating material experimentation into studio education, expanding its scope to encompass various craft mediums. Accordingly, it adopts a descriptive and exploratory qualitative methodology, combining theoretical and practice-based methods. Using atelierz, a vertical architectural design studio, as a case study, it explores the pedagogical fictions of the studio and investigates the tools used to experiment with materials, highlighting their role in fostering creativity and advancing design processes. Firstly, drawing on Gilles Deleuze’s philosophy of creative experimentation, a philosophical interpretation of the pedagogical fiction of the studio is made in terms of contexts, tools, and actors. A conceptual framework for fictionalizing the studio to encompass material experimentation is constituted considering the experimentation process’s completely unpredictable, uncertain nature. Secondly, focusing on the experimental possibilities offered by installations and prototypes, the pedagogical use of these tools in the architectural studio is analyzed. Materials, methods and tools, interdisciplinary connections, engagement modalities, and field of discovery are used as thematic frames to evaluate material experimentation in atelierz. Based on the analysis of two semesters of atelierz’s visual and physical outputs and process documentation, the findings demonstrate the impact of installations and prototypes on understanding, designing, and applying materials, developing technical skills, transforming non-disciplinary knowledge, mediating exploration, and structuring specialized fields of inquiry. In doing so, this study presents a comprehensive exploration of a design pedagogy rooted in creative experimentalism, highlighting its potential to redefine the design studio as a laboratory where research and design are integrated, based on both the theoretical framework of experimental pedagogical fiction and the experiential insights gained from atelierz. The pedagogical values imparted to students through material experimentation are examined, along with a critical discussion of the associated challenges and risks.

2. Fictionalizing the Architectural Design Studio for Material Experimentation

Gilles Deleuze’s exploration of experimentation, both independently and in collaboration with Félix Guattari, provides a foundational framework for conceptualizing, fictionalizing, and interpreting experimental processes in architectural design. His perspective on creative acts offers critical insights into the experimental processes within design [

12]. With this view, design extends beyond its traditional problem-solving role to uncover overlooked challenges, foster creative discoveries, and explore new ways of thinking and doing. Deleuze’s concept of creative experimentation offers valuable insights into both the instrumentalization of design and the fictionalization of architectural design studios as experiential learning environments that cultivate open-ended, experimental methodologies.

Building on this understanding, fictionalizing design studios for experimental processes fosters a state of continuous flow and transformation, pushing the boundaries of static, conventional educational structures while embedding experiential insights into the learning process. Accordingly, studios must be reimagined as dynamic, self-reinventing pedagogical structures where students and professionals experiment with unconventional, integrated practices of researching, thinking, and making [

13]. To sustain a culture of continuous experimentation and inquiry in design studios, pedagogical fictions that enable collaborative participation and collective knowledge production within non-hierarchical networks become increasingly significant. A studio fiction grounded in experiential interaction, fostering both disciplinary and cross-disciplinary knowledge and skills, not only expands architectural knowledge but also supports the formation of personalized research trajectories and the development of specialized practices. Therefore, research in this field is essential not only for reinforcing the studio’s role as a space for intellectual and practical development in architectural education but also for shaping its future as a foundation for evolving professional practices and identities.

Drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s [

14] concept of the rhizome, the design studio can be envisioned as an interconnected, dynamic network of thinking and making, fostering complex lines of development and facilitating new connections across disciplinary boundaries. The creative act that shapes this network creates cycles of change that deconstruct and reconstruct existing reality. Deleuze conceptualizes the creative act as a space–time formation, emphasizing its role in reshaping the understanding of reality through experience. He argues that creativity necessitates defamiliarization, enabling a transformative engagement with the world by generating resistance. Through various acts of communication, the creative act gives rise to diverse forms of expression, ultimately fostering the emergence of creative experience [

15]. According to this perspective, philosophy generates concepts, science formulates functions, and cinema constructs movement–time. In architecture, however, the creative act transforms existing reality by producing space–time formations. Through this process, it triggers the emergence of new realities and initiates cycles of continuous change. Guided by sensory perception and intuition as essential channels of interaction, the creative act unfolds new possibilities, constantly exploring and materializing novel potentials [

16,

17,

18]. In this context, the creative act functions as a transformative and exploratory practice that continuously seeks new connections between ideas and forms of expression, while fostering resistance, channeling constructive energy, and cultivating inventive experiences.

Studio fictions informed by Deleuze’s notion of creative experimentation can create open-ended processes of exploration through direct interaction with materials. Experimenting with materials, students engage in a dynamic process of discovery that intertwines sensory perception, intuitive understanding, and reflective practice, transforming the studio into a space of creative transformation [

19]. Designing with physical artifacts allows interaction between dualities of intent and artifact, representation and realization, descriptive practice, and material practice [

20,

21]. A dialogue is developed between immaterial and material realities through intuition and action. As John Fernandez expresses, this dialogue can be “intuitive, rational, irrational, associative and informed, all at the same time”, connecting the poetic and the pragmatic or the lyrical and the technical [

21] (p. 12). Thus, interacting with material reality, students’ creative acts form a craft beyond mere technical skill and foster a deepened sensibility.

As Richard Sennett mentions, a craft intervention is not only an instrumental act but also practical, comprising more than just techniques [

22]. From this viewpoint, engaging in a craft intervention during material experimentation fosters the concurrent evolution of intuition and agency. Adnan Aksu discusses craft practices in terms of agency, embodying the architect’s specific ways of behaving and doing. The architect’s unique agency, which he develops in close relation to his identity, gives him personal behavioral skills and a reflex that shapes his reactions to the phenomena he encounters. This impulse, defined as the designer’s reflex, is closely linked to developing his/her creative insight. The architect’s knowledge, senses, skills, technical sophistication, and imagination determine the development of the designer’s reflex and shape the creative insight that this reflex provides [

10] (pp. 31–45). In this sense, experimenting with materials in the studio allows for shaping the students’ designer reflexes through the continuous cohesive relationship between designerly reflection and craft intervention.

Highlighting the concepts of ‘intentionality’ and ‘agency’, Lambros Malafouris discusses material engagement as a situated skilled practice in terms of the interrelation of maker, material, and tool [

23,

24]. Within the maker-material dialogue established via diverse tools, skill emerges not as a predefined ability but as a dynamic, context-dependent process shaped through continuous interaction. Situated skilled practice, therefore, is not merely about technical proficiency but about the ability to respond intuitively to the evolving properties of materials, adapting gestures and decisions in real time. The complex interaction between designers, materials, tools, and mediums during the shaping of situated skilled practices creates a vast network through which knowledge and skills are acquired. By structuring the pedagogical fiction of the studio around material experimentation, students actively integrate intuition, knowledge, and action, developing situated skilled practices through direct, embodied interaction with materials. This process not only strengthens their ability to engage dynamically with materials but also deepens their understanding of the cognitive and sensory dimensions embedded in the act of making. In doing so, it fosters an openness to the unexpected, where unanticipated material behaviors and emergent processes become intrinsic to learning.

The creation of a situated skilled practice is closely linked to the construction of the design space, and this space is mainly shaped by the contexts in which the design action takes place and that it addresses as the problem, the tools that are used in the design, and the actors who realize the design. The interplay of these factors is crucial for fostering interdisciplinary interaction and integrating theoretical and practical knowledge and can lead to many variable situations [

13] (pp. 65–94). This is key to creating diverse design spaces, enriching the design environment, expanding design exploration, and building an integrative medium. In constructing the design space, the architectural design studio has the potential to be transformed into an inclusive environment, open to the use of all kinds of knowledge and skills, both within and outside the scope of architectural education [

25]. Accordingly, in designing studio fiction for material experimentation, the same key factors come to the fore again to collectively shape the studio: contexts (thematic content and settings), tools (mediums and technologies), and actors (instructors and students). By broadening contexts, multiplying available tools, and encouraging the diversity of actors, the studio becomes a dynamic space for experimentation, innovation, and material exploration. Within the flexible, open framework of studio fiction, students can shape their situated skilled practice by constructing unique interactions between contexts, tools, and actors.

In the architectural design studio, context extends into the thematic framework, the geographical and urban landscapes explored, and the diverse mediums that shape the design space. The contextual and structural formations developed within the studio continuously reconfigure and expand the complexity of the context, unfolding its intricate structure through iterative reconstruction. The adoption of broad and adaptable contextual frameworks enables students to enrich the curriculum by integrating research and insights from both architectural and non-architectural disciplines across a wide range of subjects. This interdisciplinary integration fosters multiplicity, encouraging unexpected and non-hierarchical connections. Consequently, students are confronted with the problem of situating themselves in a multi-layered context to construct their design practice. This process not only unlocks a spectrum of possibilities and transformative potentials for cultivating a distinctive situated skilled practice grounded in the creative act but also establishes a generative environment for the formation of design reflexes, allowing them to continuously reconstruct and refine their approach.

atelierz is fictionalized through a broad thematic series designed to integrate different fields of knowledge in the studio. Within these thematic series, each sub-theme complements the others, establishing intricate connections and interwoven relationships that contribute to a multifaceted and multilayered exploration of the main theme. In this sense, the thematic series functions as open-ended conceptual frameworks that foster the integration of design and research, transforming the studio into a design laboratory. Students navigate within these open structures, situating themselves within the theme and constructing a specialized research framework. As they do so, the connections they establish branch out and expand, playing a critical role in the formation of a dispersed yet interconnected research network.

The development and expansion of the design studio’s usual toolkit of digital and analog equipment makes a difference not only to the development of skills over ways of doing but also to the development of different ways of thinking. It expands the scope of interaction, integrating diverse disciplines, and paving the way for alternative forms of engagement. The expansion of design mediums, coupled with the transformative differences that emerge during their transference, facilitates both the deepening and multidimensional structuring of design thinking while simultaneously posing challenges that foster the development of advanced design skills. Intention and agency evolve simultaneously, in mutual transformation. While advanced digital technologies provide a preferred environment, limiting design agencies to these tools can hinder the development of fundamental skills. In this sense, the studio’s access to a range of design and production facilities, combined with its expertise in tools and materials, helps to build an integrative medium. Considering that Deleuze defines the creative act as a continuous process of transformation and proliferation of concepts and forms of expression, the structure of atelierz, based on the interaction of multiple tools, provides an environment where the creative act is continually redefined and transformed. The use of these tools with a focus on material experimentation, enables the simultaneous and multiple development of tangible experiences, which are essential for fostering intuitive and sensory connections that guide the creative act.

atelierz expands design subject matter beyond representational media, diversifying the tools and technologies used in the studio. Design work across various scales, including 1:1 applications, challenges and extends the studio’s toolkit. The range of mediums and tools is further expanded through collaborations with industrial companies, boutique workshops (such as tailors, carpenters, and foundries), and academic fabrication labs, integrating the city’s production channels into the studio’s workflow. This broad engagement with disciplinary methods and tools, both digital and analog, fosters skill development, multiple perspectives, and a holistic approach to creativity and experimentation. The diversity of tools and technologies empowers students to develop inventive, skillful interventions that embody their evolving expertise.

The integrity of the knowledge and skills of the team of instructors and students is what constitutes the collective know-how of the studio. In addition to the actors involved in the studio, the way they are involved and the interaction between them is crucial in shaping the intellectual and practical environment of the studio. Building on Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic thinking, fictionalizing the relationships between actors to embrace the diversity of creative processes and foster a non-hierarchical model of participation becomes essential. Through nonlinear, multidirectional, and open-ended networks of interaction, individual actions expand and intertwine, shaping a dynamic creative space where personal insights and collective design reflexes emerge organically. Interaction of the different perspectives, practices, and know-hows function not only as an intellectual and practical exchange but also as a dynamic field of sensory and intuitive engagement.

Taking advantage of being a vertical studio, atelierz brings together students from different academic years, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th years, facilitating peer learning and complementing diverse skill sets. The studio’s foundation is built on a hybrid group of instructors, bringing together expertise from both academia and professional practice, fostering a dynamic exchange at the intersection of theoretical inquiry and applied design. Moreover, external experts from different disciplinary fields are brought in to conduct workshops or deliver lectures, further enriching the educational experience. This collaborative approach enriches the studio’s intellectual resources and artistic sensitivity. Varied modes of interaction are fostered, allowing students and instructors to navigate both collaborative and individual work across different phases of the process. Through these evolving interactions, students engage with unconventional workflows, explore alternative forms of agency, and develop new behavioral patterns that challenge conventional design and decision-making structures. This dynamic exchange cultivates an experimental approach to interaction, fostering situational tactics and emergent modes of practice.

The thematic series Codes of Contemporary Architecture, taken as a case study in this article, frames the inventive exploration of contemporary architecture by weaving together a variety of interrelated sub-themes. The series situates the studio as a space of practice, where experimentation and discovery transcend prevailing trends and processes, and it frames contemporaneity as a dynamic space–time construct [

26]. Running since 2018, the series comprises 14 sub-themes, each tailored with specific content, settings, tools, and technologies, along with a unique combination of instructors and students. However, this study focuses on two sub-themes, ‘7 Contemplation I/Educational Spaces’ and ‘8 Contemplation II/Living Capsules’, both of which emphasize significant material experimentation.

Aligned with this thematic structure, atelierz fictionalizes the studio by considering the experimental potential of key conceptualized factors—context, tools, and actors—structuring its workflow around two primary modes of creation: ‘excessively undisciplined works’ and ‘undisciplined works’. ‘Excessively undisciplined works’ broaden artistic exploration by embracing an expansive and amateur engagement with diverse artistic tools and methodologies, while ‘Undisciplined works’ construct experimental territories at the frontiers of architecture, fostering the development of hybrid tools and methodologies. These works align with the broader studio theme, sometimes structured as separate processes in two parts and, at other times, integrated into a single part (

Figure 1a). When structured as two separate processes, excessively undisciplined works generate unidirectional resonant effects on undisciplined works, expanding the conceptual scope of the theme by introducing a highly experimental and dispersed mode of engagement. This structure allows for an open-ended field of experimentation, where excessively undisciplined works act as a catalyst, unfolding an exploratory framework that fosters deep cognitive engagement with the studied theme. On the other hand, when both modes of creation are integrated into a single process, a bidirectional resonant effect emerges. This interplay creates a reciprocal feedback loop between excessively undisciplined works and undisciplined works, generating an intertwined and expansive field of thinking and doing/making. In this configuration, the resonant effects between these modes continuously shape and transform each other, leading to the emergence of an evolving and self-generative experimental territory that opens new speculative avenues for architectural inquiry (

Figure 1b).

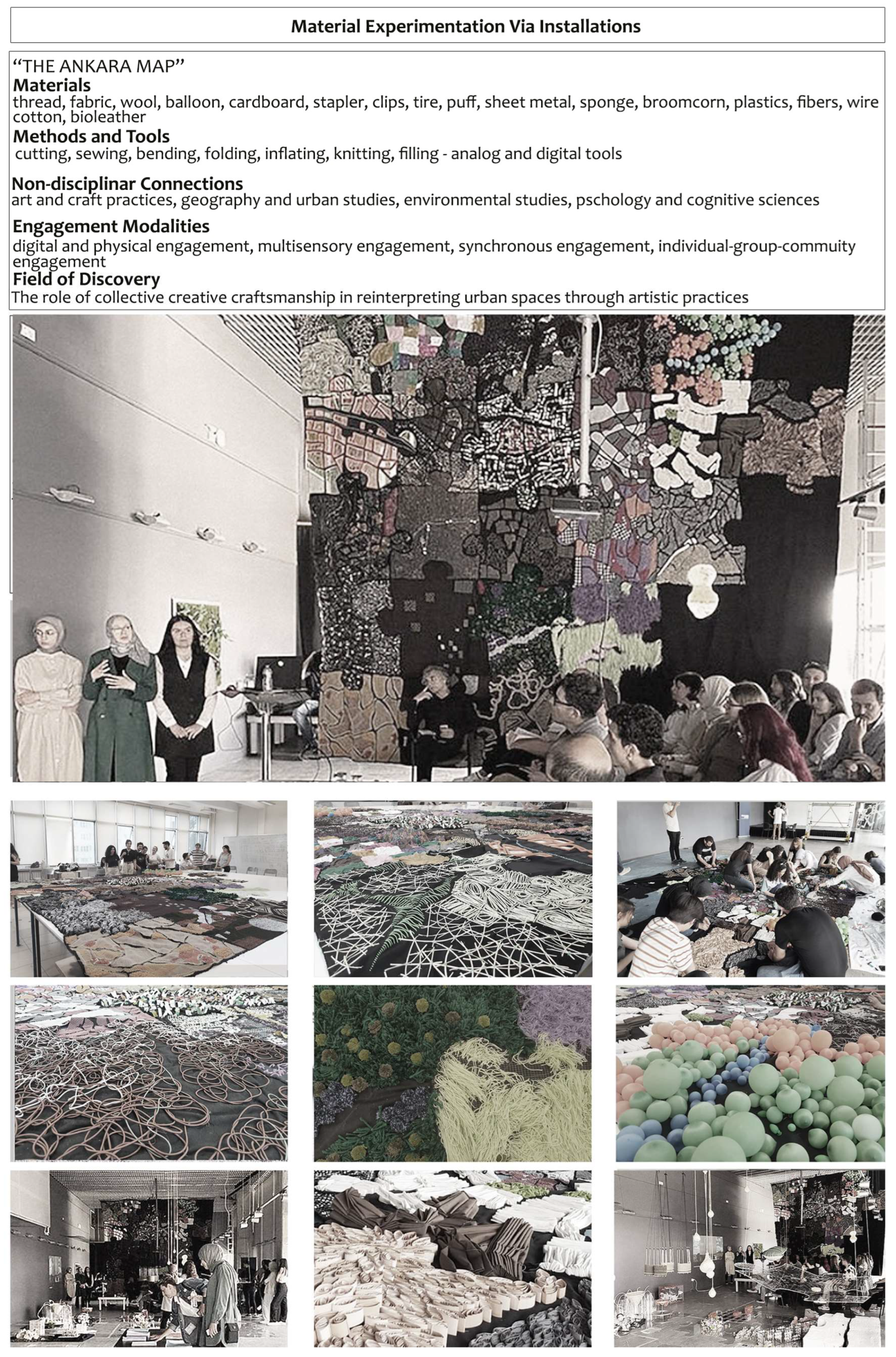

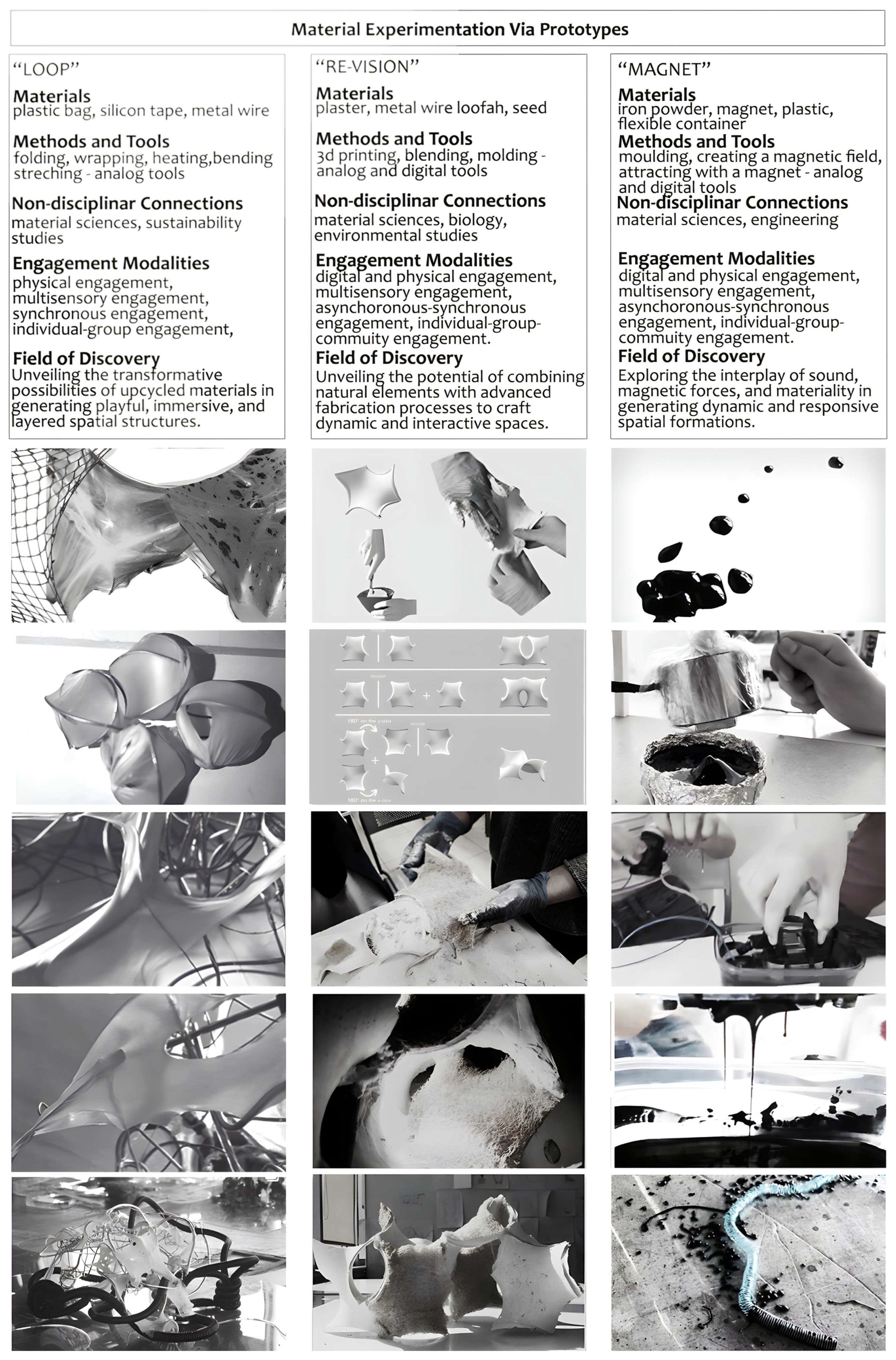

The Excessively Undisciplined Works encompass design activities that expand the studio’s thematic boundaries through artistic production, including installations, videos, performances, and objects. Students work in groups, developing specialized perspectives and discussions on the studio theme. To support their design explorations, experts from various fields are invited to the studio, providing interdisciplinary insights that enrich the creative process. These works encourage engagement with diverse disciplinary methods and tools, the acquisition of multiple skill sets, and the integration of both digital and analog techniques in various processes of doing and making. In this sense, they not only promote the specialization and evolution of unique methods and techniques but also facilitate the construction of conceptual frameworks that integrate multiple disciplinary perspectives, allowing for deeper theoretical and practical engagement with the theme. Moreover, the produced works are subjected to an interactive evaluation process involving practitioners from architecture and other disciplines, stimulating critical dialogues that broaden perspectives and deepen the learning experience.

The Undisciplined Works shifts the focus toward experimental spatial design studies, utilizing the skills and perspectives developed through Excessively Undisciplined Works. Students, working individually or in groups, are tasked with defining their spatial design problem within the studio theme and creating an artifact that experiments with space in its formal, programmatic, and structural dimensions. Through connections established both within and beyond disciplinary boundaries, the development of original design approaches is encouraged. At the same time, these works promote the formation of hybrid methods of making through the interactive use of diverse tools and techniques. The studio expands its scope by engaging with various production environments, such as workshops, laboratories, and industrial facilities, thereby enhancing its know-how. In this process, not only the tools and methods but also the range of expertise and actors involved in production become more diverse. Whether structured as distinct phases or a unified process, both components aim to cultivate students as designers who instrumentalize technology while embracing artistic sensitivity, craftsmanship, and experimental design approaches to explore new spatial potentials, challenge conventional paradigms, and foster innovative ways of designing. Within this framework, the studio experience is enriched by interrelated activities, including the construction of exhibitions showcasing studio work and the organization of thematic excursions—both long and short—that support the studio’s development through experiential learning. These complementary engagements deepen the studio’s conceptual framework while reinforcing material experimentation as a core pedagogical strategy.

4. Conclusions

This research, conducted through interwoven theoretical and practical investigations, contributes to the literature by presenting a pedagogical model for integrating material experimentation into architectural design studio practice. Through a detailed case study within the broader framework of experimental architectural design, it establishes a structured yet adaptable approach to embedding hands-on exploration in design education. The proposed model offers a repeatable, adaptable, and reinterpretative framework, generating an extensive reference system while addressing the limited body of research that examines experimental studio practices alongside theoretical discourse on material exploration.

By bridging this gap, the study highlights the transformative role of material engagement, not only in shaping inventive design practices but also in fostering architectural identity through awareness and action. It demonstrates that experimental material practices extend beyond skill acquisition, cultivating a critical and reflective approach to architectural thinking and making. Additionally, by situating the studio as a site of interactive research and practice, the study opens new avenues for future inquiry, encouraging further exploration into the evolving intersections of design education, design research, and material experimentation.

The pedagogical value of experimenting with materials in an experimentally fictionalized studio based on the creative act can be explained through the experience of atelierz, where students engaged in various experimental and exploratory design processes:

- -

Material Understanding, Designing, Processing, and Using: Students not only developed an understanding of different material properties but also gained hands-on experience with analog, digital, and hybrid processing techniques. By experimenting with unconventional material combinations and artistically exploring material properties, they were able to develop their own unique know-how through creative practice.

- -

Technical Mastery and Craftsmanship: Beyond acquiring technical skills, students created a space for themselves to explore the artistry of craft, allowing them to reflect on the poetic nature inherent in the act of making. This process helped them build a craftsperson identity, shaping their professional character while understanding and constructing both the material and themselves through making.

- -

Non-disciplinary Collaboration: Students gained insight into integrating and applying knowledge from different disciplines in their work. Through open thematic structures, they incorporated diverse knowledge sources and experimented with multiple hands-on techniques. Their intuitive and cognitive skills were challenged as they made connections between fragmented pieces of non-disciplinary knowledge, applying and reproducing them in meaningful ways.

- -

Interaction and Participation Modes: Students engaged in diverse interaction and participation modes, including individual, collaborative, and community-based practices. Physical and multisensory engagement, enabled by hands-on experimentation, deepened their connection with the creative process. Synchronous group activities fostered teamwork and collective problem solving, while asynchronous participation allowed for personal reflection and individual exploration. These varying modes not only enhanced material understanding and technical mastery but also encouraged students to engage in meaningful dialogues—both with their peers and within broader social and spatial contexts.

- -

Exploratory Design: By transforming the design process into a research process, students developed experience in unconventional ways of thinking and doing/making. Through the creation of original conceptual landscapes and inventive structural formations, they had the opportunity to mobilize their creativity in new and unexpected ways.

Considering these pedagogical values, the studio functions as a laboratory for experimentation and experiential learning, rooted in situated skilled practice. As students and instructors navigate the complex landscape of material experimentation through craft mediums, they engage in an ongoing dialogue with materials, pushing the boundaries of conventional design practice and establishing experimental research fields. Through this experimental pedagogical approach, both students and instructors participate in experiential learning processes, embracing the risks and uncertainties involved in managing processes, achieving meaningful outcomes, developing design content, and refining design expression. While these elements introduce challenges, they also offer unlimited potential for exploration and learning. By harnessing this potential, both students and instructors can continually reshape their own design agencies and redefine their unique figure of the architect.

While this study is based on the atelierz experience, the model remains highly adaptable to diverse academic and professional environments. In resource-limited studios, experimentation can focus on analog and low-tech fabrication methods, while also fostering a flexible structure that extends beyond the studio itself, integrating the university’s and the city’s production spaces into the learning process. This expansion allows students to engage with diverse material cultures, production techniques, and local craft practices, fostering a richer experimental framework. Meanwhile, technology-driven studios may incorporate computational design and robotic fabrication, further expanding the model’s adaptability.

The model’s open-ended framework extends beyond architectural education, making it applicable to fields such as industrial design, fine arts, and engineering. To ensure its effective implementation can follow a structured approach, which includes (1) defining open thematic structures aligned with institutional objectives; (2) facilitating students’ engagement with material selection and production/fabrication strategies while employing installations and prototypes as experimental learning tools; (3) fostering interdisciplinary collaboration by including diverse expertized actors and enabling non-hierarchical interaction; (4) establishing iterative and reflective feedback loops to refine both process and outcomes, fostering engagement through interaction and participation; and (5) incorporating reflective documentation methods to enhance learning experiences, support knowledge transfer, and structure studio research.

Expanding on these findings, future research could test and refine this pedagogical framework in different institutional settings, assessing its effectiveness in both research-intensive universities and practice-oriented design schools. Additionally, as a future research direction, students’ reflections on the studio fiction and their experiences could be explored through surveys or interviews, offering valuable insights into how experimental pedagogies shape their learning processes and design approaches. Furthermore, collaborations with industry partners could reveal how material experimentation in the design studio functions not only as a source of creativity but also as a space for invention, driving innovation across academia and professional practice. In conclusion, the open-ended and iterative nature of experimental design fosters a continuous process of constructing and reconstructing architectural knowledge and practice. This ever-evolving transformative force not only reshapes how design is taught and practiced but also highlights the necessity of further inquiry into how experimental pedagogies can foster critical and inventive agency, enabling engagement with the fluid and complex nature of the architectural environment and the diversifying and intricate formation of the architect figure.