Abstract

The interdisciplinary nature of theatre studies often results in research that places greater emphasis on literary analysis than on architectural considerations. Consequently, theatrical literature tends to focus more on the relationship between text, author, and context, rather than on the interaction between the text and the spatiality shaped by the architecture of the performance space of the building. This research introduces and applies a mixed methodology to examine the use of theatrical space in dramatic works, concentrating on the architectural study of paratexts, which shows the influence of literature on the architectural design process of the theater building. This study focuses on the works of Luigi Pirandello, particularly Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author, exploring their influence on the Odescalchi Theatre in Rome, and vice versa. This combined approach, alongside the theatrical qualities of the texts, allows for a detailed analysis of how architecture and spatiality are represented in Pirandellian metaproductions. The findings and their architectural modelling highlight the relationship between literature and theatrical spatiality, providing a quantifiable connection in each of the works examined.

1. Introduction: Spatiality in Theatrical Architecture

Since the first community performances, theatre has been an artistic expression that integrates various art forms, which seems to unequivocally affirm its interdisciplinary character [1] and demonstrate its a complex study structure [2]. The very term theatre, derived from the Greek théatron (that is, the space from which one looks), entails the affirmation that in the dramatic event there must exist, on the one hand, a space for the realization of a collective act [3], and on the other hand, the existence of an element that must be admired from that space [4]. With the arrival of the 18th century, a clear tendency towards specialization and professional development in artistic disciplinary studies in the theatre became evident [5]. In this context, both the architectural discipline, responsible for creating the space from which to look at, and the drama, responsible for providing the material to be performed, acquire a central relevance in dramatic events and their research studies by structuring text and performance [6]. Despite being disciplines with diverse objectives and methodologies, their research elements converge in the semiotics of theatre [7]; in its study, dramatic semiotics has historically focused more on the literary sphere, specifically the study of the text (or paratext), despite also addressing space and text. As a result, it has often lacked the necessary depth in terms of architectural spatiality [8]. This emphasis on literary studies within dramatic research has led to a distancing of spatial analysis, and, consequently, architectural analysis, from theatre studies [9]. At this point, it is important to note that over the past two centuries (S.XIX and S. XX), representational studies have been increasingly valued and developed within semiotics, although they seem to still be regarded as limited in scope [10]. The latest studies within the field of representativity begin to value the importance of architecture in the theatrical event by affirming that the dramatic building, as a container of the event itself, is what shapes the final meaning of the scene and definitely influences the spectator’s perception of it [11]. Despite this emphasis on architecture as a vessel for performance, to a large extent, these studies understand the building as a mere positioner of the stage and the audience. This means that, to a large extent, the semiotics and theatrical spatiality centre the performance on the stage and the audience in the auditorium [12], the boxes, or the amphitheatre [13]. In this view, theatre is understood as the actor on stage and the spectator in the performance space. However, both theatre architecture and playwrights have continued to evolve in their respective fields, proposing new theatrical forms that have not been fully considered in existing semiotic studies. As a result, from an architectural perspective, there is a lack of comprehensive research exploring the reciprocal influence between text and theatrical architecture.

For these reasons, this paper proposes the design and application of a methodology to quantify, qualify, and subsequently model the relationship between a dramatic text and the theatrical building that houses it. To achieve this, the primary semiotic studies linking spatiality and literature in theatre, conducted throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, will serve as the foundation (the theories presented and analyzed in the following section are from the research work of Kowzan (1986) [14], Gutiérrez Flores (1990) [15], and García Barrientos (2001) [16]). The goal is to expand the field of stage analysis by incorporating the spatiality of the theatrical building, enabling its interrelation to be both qualified and quantified. A case study will be conducted focusing on the notable Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello (Agrigento, Italy, 1867–1936). Specifically, this study will analyze the relationship between the texts of two of his plays and the playwright’s synchronic architectural typology: the Italian theatre, with particular emphasis on his Odescalchi Theatre in Rome. These plays are Henry IV (Enrico IV), first performed in 1922, and Six Characters in Search of an Author (Sei personaggi in cerca d’autore), staged at his home theatre in 1925. Although it was originally performed in 1921, Pirandello revived the play four years later with revisions to the text. The changes he introduced in this reworking were primarily focused on altering the representation of its spatiality, which was inherently connected to the theatrical building [17].

This research is essential to understanding spatiality in theatre building architectural studies because it bridges the gap between dramatic literature and architectural design, emphasizing how the two influence each other. By focusing on paratexts, such as stage directions, spatial indications, and descriptive elements, in Pirandello’s works, this study uncovers the often-overlooked impact of literary elements on the spatial design of theatres. The application of a mixed methodology, combining literary analysis with architectural modelling, offers a novel perspective on how dramatic texts shape the physical layout and model various performance spaces.

The innovative aspect of this research lies in its ability to draw a quantifiable connection between the architecture of the Odescalchi Theatre in Rome and two of Pirandello’s two plays. By examining how these plays influenced the theatre’s spatial use, and conversely, how the theatre’s architecture affects the interpretation of the plays, this study creates a two-way dialogue between literature and spatiality. This approach not only advances our understanding of theatrical architecture but also provides new insights into how spatiality and the theatrical experience are shaped by both literary and architectural elements.

2. Theoretical Foundations

The semiotic study of theatre, compared to literary research on poetry, essays, or novels, has experienced a significant delay [18]. Similarly, these studies have typically concentrated almost exclusively on on-stage dramatic performance [19]. The most notable research in theatrical semiotics concerning representational spatiality has primarily occurred during the 20th and 21st centuries [20]. Among such research, after an exhaustive review of the available bibliography, it is necessary to highlight three studies. In chronological order, these studies are as follows:

- El signo en el teatro [The sign in theatre] (1986). T. Kowzan (1922–2010) [14].

- El espacio y el tiempo teatrales: propuesta de acercamiento semiótico [Theatrical space and time: a proposal for a semiotic approach] (1990). F. Gutiérrez Flores [15].

- Cómo se comenta una obra de teatro [How to comment on a play] (2001). J. L. García Barrientos (1951) [16].

The classification provided by Kowzan proposes thirteen signs to study in representation. From an initial classification of verbal and non-verbal signs, the researcher classifies them further into spatial and temporal signs. Among the spatial ones, he assumes those of the actor’s external appearance (make-up, hairstyle, and costume), those of body expression (mimicry, gesture, and movement), and those of the characteristics of the space, which are classified into props, set design, and lighting [14]. For his part, Gutiérrez Flores classifies spaces according to whether they are textual (proposed by the author in the libretto) or spectacular (the spaces in which the theatrical event takes place). At this point, it is important to note that this classification mirrors that of semiologist Bobes Naves (1987), who previously described the dramatic text as a combination of literary text and performance text [21]. Additionally, Gutiérrez Flores distinguishes between spectacular spaces, identifying scenic spectacular spaces, such as the stage, and theatrical–spectacular spaces, which he defines as all other areas of the theatre building where the theatrical event occurs, including the stage itself [15]. Furthermore, García Barrientos classifies spaces as either unique (if the work takes place in a single location) or multiple (if it occurs in more than one location); visible or invisible; iconic, if they represent a real place; metonymic, if they are only suggested to the spectator through hints; or conventional, if they follow a symbolic convention [16]. The three studies mentioned above address stage spatiality, though it is worth noting that both Gutiérrez Flores and García Barrientos base their research on the theories introduced by Kowzan [14,22], a study widely regarded by theatre critics as the most practical [8]. These theories were consolidated and expanded upon in further research by Iglesias (2024) [23], who applies the conclusions drawn from these methodologies in his work.

After outlining the key contributions of each study, several key points need to be highlighted. First, the research presented above bases its classifications of the representative adaptation of the text on the proposals of playwrights or stage directors [19]. Second, it is important to note that these studies primarily focus on the stage space, often overlooking other potential theatrical spaces within the building. This limits the exploration of extra-scenic signs and the full experience of the theatrical event [24], thereby preventing a comprehensive understanding of theatre as a whole [25]. While García Barrientos acknowledges the possibility of extending the theatrical event to the auditorium [16] (pp. 153–154), and Gutiérrez Flores, in his description of theatrical–spectacular spaces, allows for the stage to interact with other areas of the theatre building, neither goes further in exploring the relationship between the performance and the building as a whole. Therefore, these classifications are limited to the scope of the stage designer or stage director’s work [26] and overlook the potential of the auditorium or other areas that a specific architectural typology of synchronous theatre could offer to the author [6] as possible scenic spaces. After analyzing the proposed research, it can therefore be affirmed that their application must be based on the theatrical texts—that is, on the paratexts—and that, by opening up the scenic field beyond the stage, they will be the optimal starting point for the architectural reading of theatrical works.

Consequently, the starting point of the architectural reading methodology to be proposed should be contemplated in the paratexts, i.e., all of the dramatic text that is consciously contemplated in the discourse of the play, and which effectively has an influence on the perception and interpretation of the play as a whole [27]. To this extent, theatrical paratext is defined as any text found in titles, the arrangement and hierarchy of the characters, temporal and spatial indications, descriptions of sets, movements and gestures, interludes, and omitted texts [28]. Within these texts, according to the definition given by Bobes Naves, theatrical–spectacularity will be fixed in the representative part of the paratext, that is, in what are commonly known as annotations and didascalies (annotation is defined as any stage action in a text, and didascalia is a note of stage action within an actor’s speech [29]), which, in the work of some dramatists, intending to outline a clear message and discourse, could be considered to be hypertrophied [30]. Thus, here, we focus on the text of the play being analyzed and confine our field of study to what theatre criticism refers to as dramatic theatre. Dramatic theatre can be defined as all drama, from Aristotle to the end of the 19th century, where the text is the central axis of the play’s structure. It is, therefore, a logocentric theatre [31], with other elements, such as music or dance, being part of the performance but always subordinate to the written text [32]. On the other hand, when analytical study is approached from an architectural perspective, it must examine the theatrical event in its entirety. This means considering the entire stage space, not only the area framed by the stage but also any part of the theatre building that can function as a stage. In this context, stage space should be defined as any area within the theatrical building where a performance occurs, regardless of its specific character or the architectural typology of the space [33]. Therefore, essential in the spatial analysis is the impact that, as mentioned by Bobes Naves (2004) [7], the theatre building itself has on the play and on the audience. To this end, it is important to note that the typology of Italian theatre forms the foundation of all modern scenography [34] and remains the most widely used today [35]. However, it is also worth mentioning that other theatrical typologies, such as the Spanish Corral de Comedias or the English Elizabethan Theatre, with their distinct actor–spectator relationships, are still in use [36], although they are generally considered secondary to the Italian model [30].

The following chart summarizes the key contribution of the above-mentioned scholars to the understanding of the evolution of theatrical spatiality studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of key contributions to spatiality in theatres studies [14,15,16,21,23]. Own elaboration.

In this study, the Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello is taken as the foundation. Pirandello is known for his meticulous treatment of annotations and stage directions in his texts [37]. His evolution as a playwright led him to clearly define all his performative intentions in writing, especially in his metatheatrical works. It is important to note that Pirandello’s metatheatre—comprising Six Characters in Search of an Author (1921–1925), Henry IV (1922), Each in His Own Way (1924), and Tonight We Improvise (1930)—focuses on exposing theatre as theatre, laid bare in front of the audience. In other words, the theatrical space is portrayed as a dynamic environment for both actor and spectator [38], with its practices and mechanisms fully revealed [39]. This blurs the lines between fiction and reality, the mask and the face, by dismantling the barriers of verisimilitude and theatrical illusion that typically assure the spectator of what is perceived as real [40]. Specifically, regarding space, Pirandello’s metatheatricality is viewed in literary studies as a phase of deconstruction and rupture of traditional stage structure [41]. Between 1924 and 1928, Pirandello also served as director of the Teatro d’Arte [42]. Reflecting on his transition from being a playwright to also taking on the role of company director, Pirandello wrote, “I am now the puppet of my passion: the theatre” [43]. And by “theatre,” he also meant “the material: actors, the hall, the stage, and the stage machinery” [44] (pp. 5–6). Through his directorial experience, Pirandello developed a close relationship with scenography, enabling him to convey his visual ideas for the scenes in great detail. He proposed extensive didactic annotations to establish an aesthetic connection between the theatrical event, the text, and the stage in its broadest sense [45]. His vision of art, in general, and theatre, in particular, as a fusion of theory and practice, aesthetics, and materiality [46], makes him an ideal subject for this research (see the reflection that Pirandello makes on this subject with Benedetto Croce ((Pescasserolo, Italy, 1866–1952), Pirandello’s contemporary art critic [46] (p. 1123)). For Pirandello, a dramatic text that did not integrate its representational aspects within the theatrical building could not be considered true art. Therefore, his work is central to this research, where his approach will be examined through the spatial methodology proposed. It is important to note that while studies on Pirandello’s theatre and metatheatre are acknowledged, they will not play a decisive or interpretative role in this research. The focus here is on obtaining and analyzing purely architectural and spatial data regarding the building in which his works are performed, in a manner that is almost structuralist in approach, aiming for objective and verifiable results [47]. The ultimate goal is to catalogue the shift in the perspective of performative spatiality in Pirandello’s work. Additionally, choosing Pirandello, the Italian Nobel laureate, allows us to investigate the architectural typology of the Italian-style theatre, specifically the Odescalchi Theatre.

Once all aspects of this study have been outlined, the central question will focus on analyzing the referentiality between the dramatic text and the theatrical architectural structure. To address this, a hypothesis will be presented regarding the suitability of a dramatic text (paratext) to be represented (or not) within any theatrical architectural typology in a way that remains faithful to the author’s original text. To achieve this, a research framework will need to be designed that allows for the quantification and qualification of the paratexts and the inference of their influence and impact on the performative spatiality of the dramatic building contemporary to the writing of the play. It is essential to establish the representational fidelity of the text to ensure it is not freely interpreted but rather performed in accordance with the original work, rather than adapted [48]. Through this proposed methodology, the aim is to demonstrate that each theatrical text inherently reveals crucial information about its spatial representation and its functional application within the building. If these objectives can be met, the relationship between the dramatic text and the theatre building will be established.

3. Objectives and Methodology

The main objective of this paper is to obtain data with which to estimate the spatialities that the studied author’s use of text expresses via his theatrical texts (paratexts). The primary motivation stems from an observable notable gap in the deployed methodologies and available literature, which fail to connect the disciplines of theatre and architectural construction, despite the methodological works discussed earlier. Thus, this study adopts dramatic theatre as its foundational framework. Consequently, theatre forms that fall outside this definition—such as post-dramatic theatre [49], which does not rely on text as its central element or only partially incorporates it [50]—are excluded from consideration. Hence, the first objective of this research must be to develop a methodological process that demonstrates how the paratexts of dramatic theatre convey a specific spatiality within the representational space, making its quantification and qualification feasible. To achieve this, a mixed-methods approach [51] is proposed. Additionally, the second objective seeks to establish a relational framework that anchors the paratexts of dramatic theatre to the typology of theatrical building. This objective will enable an investigation into the impact of dramatic literature on the architectural design of the theatre and vice versa, exploring the influence of the built environment on the creative process of playwrights.

For all these reasons, the following research questions are posed. First, we ask ourselves: is it possible to parameterize and qualify the spaces described in the paratexts? Second, we try to find an answer for the following question: can this parameterization establish a connection between the Italian author’s text and the architectural space of the dramatic building? Finally, we ask the following question: can this connection form an inseparable relationship between paratext and architectural typologies?

Our primary aim is to evaluate whether a dramatic text can be faithfully represented within a specific theatrical architectural typology—whether conventional or otherwise [52]—or within any stage or production system that decentralizes the dramatic event [53]. To this end, this study will provide the resources necessary to confirm whether a text can be graphically represented or transmediated into an architectural framework, particularly focusing on the dramatic building and its spatial divisions.

Finally, by applying the proposed methodology to selected works of Luigi Pirandello, this research aims to draw conclusions regarding how his role as a director of the Teatro d’Arte influenced the application of the Italian-style theatre’s synchronic architectural typology.

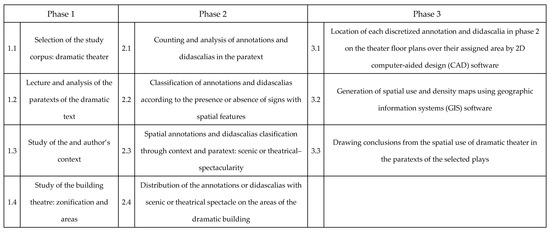

A methodology comprising three cumulative phases is proposed to achieve the stated objectives. This approach is grounded in the foundational studies of Kowzan, Gutiérrez Flores, and García Barrientos, which combine classifications to be applied to paratexts [23]. In the first phase, the research framework is established. Given the nature of this study, the works included in the corpus must be classified as dramatic plays under the criteria of theatre criticism. For this specific case study, two plays by Luigi Pirandello are selected, based on the reasoning outlined earlier. These plays are chosen from Pirandello’s metatheatrical works as they are expected to provide a stronger and more explicit connection between textuality and spatiality.

Consequently, the paratexts of Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author are analyzed from an architectural perspective. These plays were selected for their high degree of theatricality, characterized by their extensive textuality. This aligns with Roland Barthes’ (1915–1980) concept of theatricality, which emphasizes the quality and quantity of didascalies in the authors’ librettos [54]. Similarly, the selection of these works allows for a comparative analysis between a disruptive play like Six Characters in Search of an Author, which explores the contrast between reality and fictionalized reality [55], and another play considered traditional by literary critics, despite its inclusion in metatheatricality [56], Henry IV [57]. Furthermore, by choosing a play written prior to Pirandello’s role as a theatre director (Henry IV, 1922) and another in its rewritten form after he assumed that role (Six Characters in Search of an Author, 1925), this research aims to examine the impact of his experience in theatre direction on his dramatic writing and his performative use of the theatrical building.

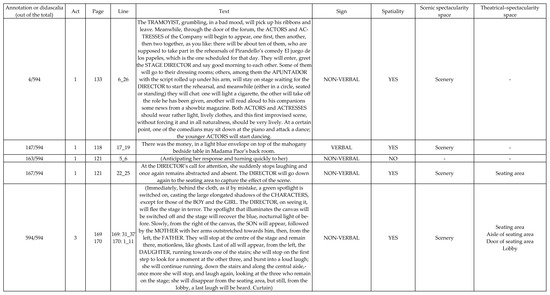

In the second phase of the deployed methodology, after reading the paratexts, we proceed to count and classify the signs proposed in them. This procedure will be carried out by classifying these annotations according to the presence or absence of spatial characteristics in accordance with Kowzan’s criteria and then reassigning them according to García Barrientos’s approach.

Afterwards, the obtained annotations will be classified according to the criteria of Gutiérrez Flores with respect to their scenic or theatrical–spectacularity. With the aim of achieving optimum and defined results, it is proposed that these classifications should be made not only according to the globality of each of the plays but also that the data should be disaggregated according to the division of the acts of each drama. By fixing all the above data, the aim is to achieve the use of the architectural space in the paratext. It should be noted that at this stage of the research, each annotation and didascalies should be analyzed both collectively within the play as a whole and individually.

In the last stage of the methodology employed, based on the data collected, it is suggested to carry out the representation in the theatrical building through a process of graphic transmediation [58] of the text to the plan. This transmedial process will reflect the linking of the texts of each play to the dramatic building. Each annotation will be related to its location on the floor plan of an Italian-style theatre, using a dot-mapping diagram that will place the annotation or didascaly in the place where the action takes place, according to the paratext of the Italian playwright. To create the graphic representation of the spatial uses, 2D and 3D computer-aided design (CAD) software (AutoCAD (v2021)) and geographic information systems (GIS) modelling and data-processing software (ArcGIS Pro 3.0.2 (v2022)) will be used.

The following procedural figure (Figure 2) is presented below to provide a summary of the methodology proposed in this study.

Figure 2.

Phases of the proposed methodological procedure. Own elaboration.

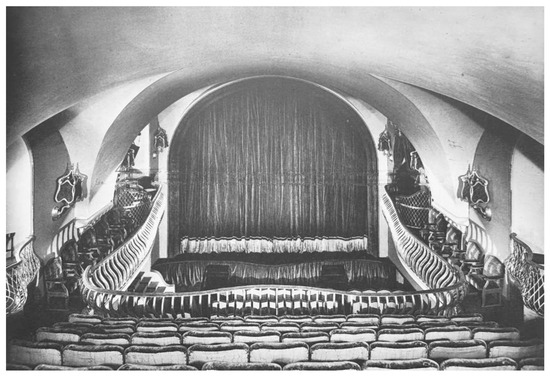

This research proposes a graphic representation of the collected data using the Odescalchi Theatre in Rome as a reference. This dramatic building, of Italian typology (Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5), incorporates the three primary areas: the stage, the former orchestra area now serving as stalls, and the upper seating area [59]. The Odescalchi Theatre was reconstructed in 1924 by Virgilio Marchi (1865–1960) to serve as the headquarters of the Teatro d’Arte, following Luigi Pirandello’s instructions [60] (p. 216). Its stage dimensions are relatively modest, with a usable space of less than 8 m in width and 7 m in depth [44] (p. 54). Despite its size, the futuristic and innovative reconstruction of the Odescalchi Theatre was regarded at the time as one of the most advanced dramatic buildings in Europe [44] (p. 55). For these reasons, the architectural design of the Odescalchi Theatre is deemed the most suitable framework for this study, allowing the transmutation of the parameters derived from the Italian author’s paratexts into spatial representations.

Figure 3.

Geometry of the Odescalchi Theatre [61] (p. 2).

Figure 4.

View of the stage of the Odescalchi Theatre [44] (p. 59).

Figure 5.

View of the Odescalchi Theatre hall [44] (p. 61).

In order to elucidate the application of the methodological procedure delineated in this section and summarized in Figure 2, the following is an example of some of the plays selected for this study. As the selection of the corpora plays, their close reading, the study of the author’s context, and the theatrical building constitute the first phase of our methodological process, these cannot be portrayed in this intended example. Therefore, the following figures show examples relating to phase 2 of the methodology applied in this paper (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Example of methodological application of annotations and didascalias in Henry IV. Own elaboration.

Figure 7.

Example of methodological application of annotations and didascalias in Six Characters in Search of an Author. Own elaboration.

The third phase of the methodological procedure will be contingent on the theatre building, as well as its zoning and areas; therefore, the modelling of the results of phase 2 can be observed at the conclusion of the Section 4 (Figures 12–15).

From the data collected and their graphic transmediation, conclusions will be derived that will allow us to link a dramatic text with a specific dramatic building typology and the possibility of studying the use of a dramatic building in a specific play.

4. Results and Discussion

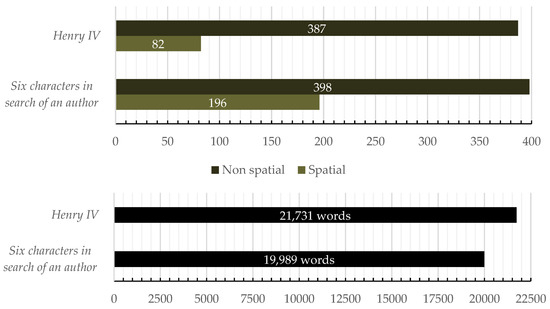

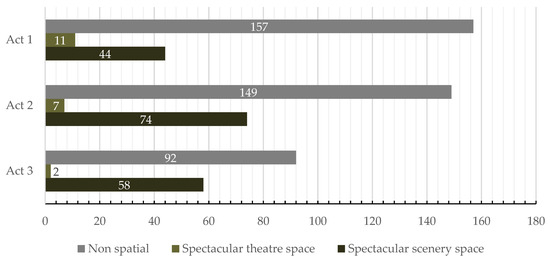

As the first phase of the proposed methodological process, the paratexts of Henry IV [46] (pp. 115–189) and of Six Characters in Search of an Author [62] (pp. 81–170), belonging to the versions listed in the bibliographical references of this work, are analyzed. After the analysis of the texts and the application of the methodology, the quantification of the didascalias and annotations in both works is obtained. The didascalias and annotations in both works are quantified and classified according to their spatial characteristics. Generally speaking, the use of theatrical space in both texts is summarized in the following figure (Figure 8). In addition, in the same figure, the length of each of the plays in words is taken as a reference.

Figure 8.

Quantification of total words in the works and distribution of annotations according to the presence or absence of spatiality. Own elaboration.

From the data gathered, it can be concluded that the spatiality in Six Characters is, in absolute terms, significantly higher (+239%) than in Henry IV. This finding becomes even more relevant when analyzing word length, where Henry IV is only 9% longer than Six Characters. When comparing the annotations or didascalias in absolute terms, the statement becomes even more compelling. In Henry IV, 17.5% of the annotations present spatial characteristics according to the methodologies mentioned above. In contrast, almost 33% of the Six Characters annotations reflect spatial characteristics. Therefore, it can be affirmed that Six Characters offers more information in its paratext about the spatiality of its representation. To conclude this phase of the architectural analysis of the works, the classification of spaces is addressed. In this analysis, it is determined that of the 82 annotations in Henry IV, 7 (8.5%) refer to spaces that are not visible during the action, and all of them (100%) are iconic spaces; that is, they are proposed by analogy with real spaces. Applying the same criteria to Six Characters, we find that 33 of the 196 annotations (16.8%) mention spaces that are not visible at the present moment of the representation. Of these, the proposed spaces include a theatre stage, a stage simulating Madame Pace’s house, a stage simulating an orchard, and a theatre proscenium; 50% (theatre stage and proscenium) are spaces that actually exist, while the other two (50%) are proposed by analogy with other real spaces. Thus, Six Characters, again, presents a more distinctive and expressed spatiality, in comparison with Henry IV.

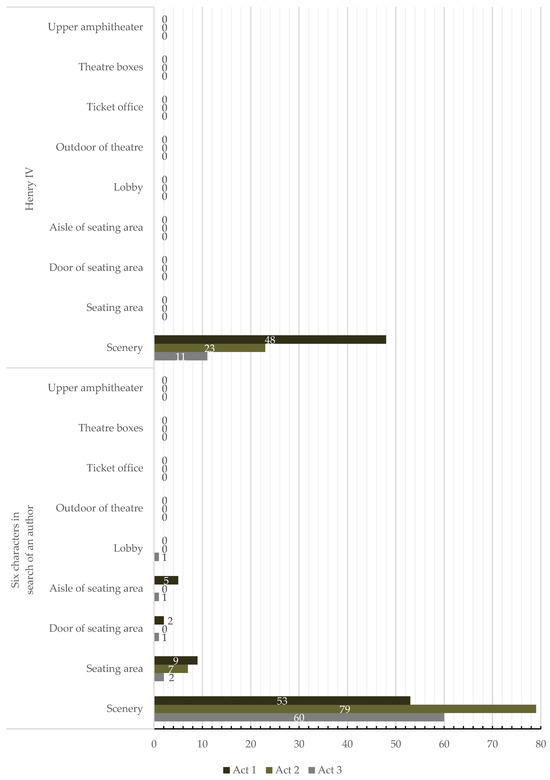

The final phase of the methodological process then commences; in this last phase, annotations and didascalies from the paratexts will be categorized based on their references to specific areas of the theatrical building, utilizing Gutiérrez Flores’s distinction between scenic spectacular spaces and theatrical–spectacular spaces. To enhance the accuracy of the results, the data will be analyzed and presented according to the division of acts within each drama. The findings for Henry IV, which features a three-act structure, are displayed in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Classification of the annotations and didascalias in Henry IV. Own elaboration.

After carefully analyzing each of the quotations from Henry IV—as shown in the figure above (Figure 9)—in detail according to act or exclusively according to spatial characteristics, it has been discovered that they make no mention of any off-stage theatrical space. Of the 82 annotations with spatiality, none of them qualify as theatrical–spectacular spatiality. Therefore, Henry IV does not propose any representation in a spectacular theatrical space, and its texts propose its representation exclusively on the spectacular stage space (100% of the annotations with spatial characteristics). Thus, the spectator has only one point of view throughout the drama: the stage.

Subsequently, the results obtained for Six Characters in Search of an Author are shown in the following figure (Figure 10), mirroring the previous presentation in three acts.

Figure 10.

Classification of annotations and didascalias in Six Characters in Search of an Author. Own elaboration.

From Figure 10 onwards, Pirandello, in this comedy, uses off-stage spectacularity. As a result, the paratext of Six Characters includes the use of spectacular theatrical architectural spaces. After implementing the methodology, it has been concluded that 10.2% of the didascalias in relation to the total number of textual annotations and didascalias with spatial characteristics refer to spectacular theatrical spaces. Meanwhile, the remaining 89.8% of the textual annotations with spatial characteristics establish representations of the spectacular stage space. If we analyze the distribution of spectacular spaces by act, Act 1 of Six Characters is mainly relevant for this characteristic spatial use, since 11 of the 55 spatial annotations and didascalias (20%) refer to at least one use of offstage spaces. The use of theatrical showmanship in Act 2 (8.6% of the totality of textual annotations with spatial characteristics) is also considered relevant.

In summary, in Henry IV, 100% of the annotations refer to the use of the stage. Meanwhile, in Six Characters, this use is reduced to 89.8%, with the remaining spatial annotations referring to other areas of the space of the theatre building. In this respect, the use of spectacular spaces allows for a more in-depth analysis. When these results are discretized on the typology of an Italian theatre, namely, the Odescalchi Theatre and its characteristic spaces [63,64], the distribution results in the following figure (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Spectacular spaces in Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author (for the calculation of these quantities, it must be taken into account that within the same dimensioning or didascalia, the author may make reference to one or several spectacular spaces). Own elaboration.

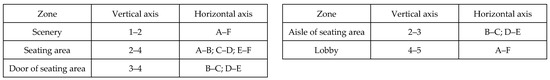

For a more detailed analysis of the spatiality in each work under study, the data from the previous figure (Figure 11), which outlines the ground-floor architecture of the Odescalchi Theatre, are presented. It is important to note that in both works, the author specifies actions only within spaces corresponding to the ground floor of the theatre. Therefore, this research focuses solely on the ground floor of the building. In accordance with the preceding figure (Figure 10) and the floor plan of the theatre building, the zones assigned between axes correspond to the following figure (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Distribution of spaces on the theater building through axes. Own elaboration.

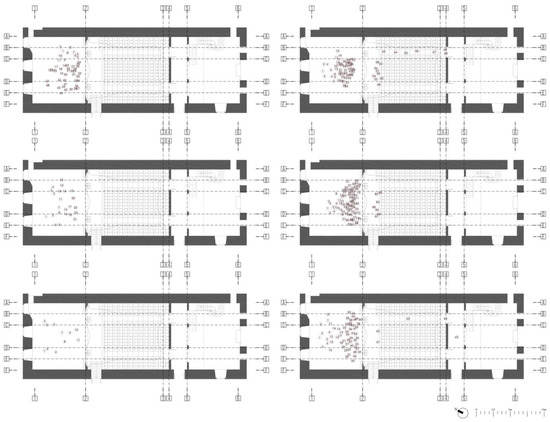

The results are represented in the following figure (Figure 13), where each annotation or didascalia from the previous figures (Figure 11 and Figure 12) is positioned within the theatre building according to the actions described in the libretto of each play.

Figure 13.

Distribution of the annotations and spatial annotations on the plan of an Italian theatre (axes shown in Figure 12). On the left, from top to bottom, Henry IV: Act I, II, and II. On the right, from top to bottom, Six Characters in Search of an Author: Act I, II, and III. Own elaboration.

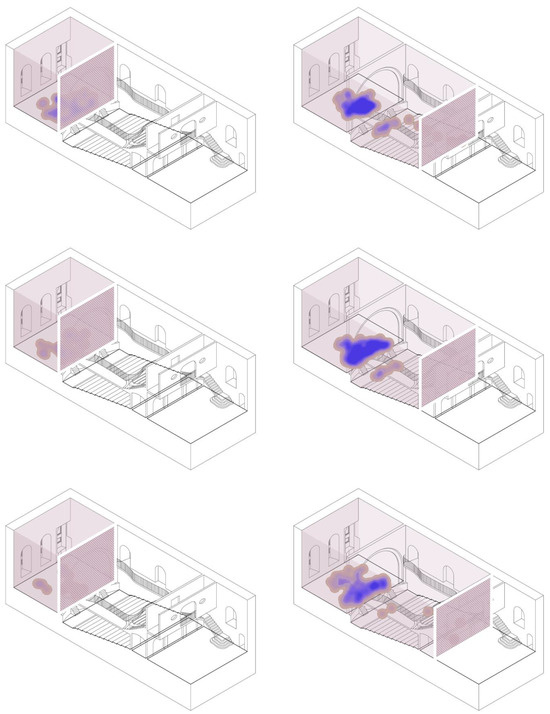

Continuing with the procedural steps outlined in the methodology of this study, the following figure (Figure 14) shows the occupation density maps proposed for the theatre building on the floor plans generated for the Odescalchi Theatre.

Figure 14.

Maps of spatial densities on the theatre building in both plays (axes shown in Figure 12). On the left, from top to bottom, Henry IV: Acts I, II, and II. On the right, from top to bottom, Six Characters in Search of an Author: Act I, II, and III. Own elaboration.

As illustrated by the figure above (Figure 14), the spatial arrangement of the text established by Pirandello in Henry IV remains constant on the stage of the Odescalchi. In contrast, in Six Characters in Search of an Author, the use of theatrical space expands into other areas of the building, encompassing the entire dramatic building, including the auditorium and even the foyer. This change in the perception of space, where the action moves throughout the building, creates a dynamic that transcends the simple idea of bringing the action down from the stage or breaking the fourth wall: Luigi Pirandello promotes a movement of the fourth wall through the drama building.

In Henry IV, the stage frame separates the action from the spectator, reflecting a classical and traditional use of theatrical space throughout the three acts. In contrast, in Six Characters in Search of an Author, this approach expands in the second act to the doors of the stalls, including both the action and the spectator within. In the third act, this fictional barrier is even extended to include the foyer of the building. Thus, the analysis of the data presented in the figure above (Figure 14) reveals a distinctive and particular use of the spatiality of the building in this play by the Italian playwright. This spatial singularity of Pirandello’s Six Characters represents an evolution—or, at least, a transformation—of the traditional veil of the fourth wall within the scenic frame. In this way, Pirandello adjusts the use of theatrical space and its perception through the dramatic paratext, making the theatre building itself the stage for the entire play. Graphically, this movement of the fourth wall, derived from the collected data, is represented within the space, as shown in the following figure. This representation also includes annotations for each act (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Evolution of the fourth wall in the plays analyzed. On the left, from top to bottom, Henry IV: Acts I, II, and III. On the right, from top to bottom, Six Characters in Search of an Author: Act I, II, and III. Own elaboration.

Finally, it should also be mentioned that following the detailed analysis of each spatial reference in each of the texts, the fact that there is theatrical spatiality in Six Characters does not imply that the general spatiality in Henry IV is not developed; it is simply expressed only in the spectacular stage space. To this end, by way of example, it is advisable to read the first spatial note in Henry IV [46] (p. 117), of 158 words, and the first one in Six Characters [62] (p. 102), of 194 words. From these, we can see the broad Barthean theatricality that the Italian author applies, in particular, to these two works.

5. Conclusions

This study, based on the analysis of the data obtained, has successfully systematized the dramatic spectacularity in the paratexts of two case studies: Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author by Luigi Pirandello, as performed in the Odescalchi Theatre. The findings derived from this analysis have been applied to two paradigmatic works of universal theatre, providing both the quantification and qualification of the use of performative spatiality within their texts, as well as their graphic parametrization on the theatrical building.

Reflecting on the research questions posed earlier in this study, the following conclusions can be drawn.

First, it can be affirmed that through the analysis of various studies on the semiotics of theatre and the classifications of theatrical spaces developed over the last two centuries, an effective methodology can be designed and applied to review dramatic theatre from the spatial perspective of the architectural building.

Second, and in answer to another of our research questions, the protagonism of the space of the theatrical building in the texts of the selected plays is affirmed. Therefore, it can be affirmed that there is an empirical and objective link that inescapably relates the texts of the author studied with the synchronic architectural typology of the Italian playwright: the Italian theatre. This is why, in the wake of this study, it can be concluded that a play such as Henry IV, in which, in its paratext, 100% of the notes and didascalias with spatial characteristics refer to the spectacular stage space, expresses its link with any dramatic typology that has a stage space. For its part, Six Characters in Search of an Author has a theatrical–spectacular charge that Henry IV does not have. This causes its link with any architectural typology that possesses a stage to drop; it has a 10.2% relationship with other dramatic architectural typologies that possess other spectacular spaces. Likewise, the data obtained allows for the graphic expression of the literary texts with respect to the author’s indications regarding dramatic architecture. This enables a broader study of both the dramatic work and the theatrical architecture.

Consequently, a totally spectacular stage play can be performed in a way that is faithful to the author’s paratext in an Italian-style theatre building, in an Elizabethan theatre, in a Corral de comedias, or in any space for the representation of conventional drama or new performances—even in an open-air performance in an urban space. However, a play in whose paratexts the author proposes spectacular theatrical spaces, however minimal they may be, restricts and limits a faithful representation of existing theatrical architectural typologies. In this sense, a play such as Six Characters, with 10.2% theatrical–spectacularity, will be anchored to Pirandello’s synchronic architectural typology—that is, the Italian Theatre—since its paratext mentions spaces belonging to this typology. In this way, this work will be compromised in its representation in an Elizabethan Theatre or a Corral de comedias as these typologies do not have the spectacular theatrical spaces that Pirandello proposes. This is to say that Six Characters can only be performed, for example, in a street theatre or a non-conventional dramatic architectural typology through an adaptation of the paratext by the stage director. In this sense, a quantification and qualification of the dramatic paratexts has been achieved that allows us to stress their connection with the architecture of the theatre building.

The evidence suggests that theatrical literature exerts an influence on the architectural design of theatres and that the architectural features of dramatic buildings, in turn, exert an influence on the creative capacity of playwrights, who are acutely aware of the potential and limitations of the spaces of the building in which they work.

In the same way, it is possible to affirm that the author—in this case, Luigi Pirandello—was fully aware of the conditioning factors, as well as of the artistic possibilities that his conventional synchronic dramatic space offered him, particularly with respect to his vision of dramatic literature as a confrontation of reality and fiction. Therefore, the Italian was creatively influenced by dramatic architecture with respect to the actions and representations that he could propose in his plays from the very moment of their genesis. Likewise, as has been suggested in this research, the data obtained specify the difference between a play written before his activity as a director and another rewritten when he was a stage director. Thus, a work written in 1922, such as Henry IV, proposes a spatiality with respect to the capacities of the building that can be characterized as conventional; however, in a play rewritten in 1925, and with the author in charge of the theatre building, the data attained through the application of our methodology show that Pirandello was fully aware of the complete and complex performativity of the theatrical event, proposing spatial games in the performance of his play through the use of theatrical–spectacular spaces in full awareness of the changes to the spatial paradigms that this produces in terms of the spectator’s perception.

Furthermore, the analysis of the results obtained reveals a change in the spatial perception of the works: whereas in Henry IV, the spectator is always behind the fourth wall, in Six Characters, Pirandello modifies this spatiality by incorporating the audience into the space destined for the action; he places the spectator within the fourth wall, making him a participant in this duality between reality and fiction. Pirandello was thus aware, once again, of the possibilities and limitations of his conventional dramatic spaces.

Thus, this analytical procedure has succeeded in quantifying, qualifying, and graphically representing, through transmediation, the spatiality of the plays Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author in a dramatic building, namely, the Odescalchi Theatre. In this way, the use of this methodology makes it possible to extend the analysis of theatre criticism, commonly centred on literary criticism, towards developing an architectural perspective. It also demonstrates Luigi Pirandello’s performative metaevolution; that is, evolution through an innovative performativity in which the author is fully aware of the space and shapes his work accordingly.

Thus, this research highlights the crucial link between dramatic literature and architectural configuration in theatre studies. By focusing on Pirandello’s works, particularly on Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author, and their influence on the Odescalchi Theatre in Rome, this study demonstrates how theatrical paratexts inform the design of performance building spaces.

The innovative mixed methodology employed in this paper combines literary analysis with architectural modelling, allowing for a deeper understanding of how spatiality is represented in theatre, thus going further than the studies carried out previously and noted in this paper. In this light, the findings of this study reveal a quantifiable connection between literature and architecture, offering new insights into the interplay between dramatic works and the built environment of theatres. This approach enriches the study of both literature and architecture, providing a comprehensive view of how space and narrative interact in the theatrical experience.

Finally, the results and conclusions of this study, based on Henry IV and Six Characters in Search of an Author, allow us to open up new lines of research in theatrical analysis. First, it will be possible to adapt this procedure to apply it to the learning of spatiality in artistic and performative teaching. This research has also focused on the general influence of architectural typology. In this regard, it is proposed that we continue our analytical work by carrying out an in-depth study of the subcategories of theatrical–spectacular spaces in each dramatic building typology. Finally, it is proposed that we validate the study via the application of this method to the rest of the Pirandellian metatheatrical works. These last two lines of study are currently being developed and elaborated within the framework of the research carried out by the author of this work on Pirandellian metatheatrical production.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Notario Sánchez, A. Investigar, reflexionar y debatir en torno a una nueva historia del Arte. In Temas de Historia del Arte: Escenarios, Contextos y Relatos; Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: Cuenca, Spain, 2024; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Vivanco, E. Deconstrucción e interdisciplina en la puesta en escena y la performance. In Experiencias Didácticas Interdisciplinarias en el Arte; Carpinteyro Lara, E., Rodríguez Luna, S., Eds.; Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla: Puebla de Zaragoza, Mexico, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, P.; Steffen, M. A place of seeing: People’s Palace Projects and the city of Rio de Janeiro. Estud. Hitóricos 2022, 76, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, C.; Torres Monreal, F. História Básica del Arte Escénico; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, M. Ekphrasis: The Illusion of Natural Sign; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pavis, P. Diccionario del Teatro: Dramaturgia, Estética, Semiología; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bobes Naves, M.C. Teatro y Semiología. Arbor 2004, 177, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral Vega, E. Análisis de Una Representación Del Teatro Breve Valleinclanesco: “El Retablo de la Avaricia, la Lujuria y la Muerte”. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carbajosa Palmero, N. Up Pictura Poesis: Reflexiones desde el teatro de Shakespeare. Signa Rev. Asoc. Esp. Semiót. 2021, 12, 587–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares Ávila, C. Condicionantes de la grabación audiovisual de espectáculos artísticos escénicos. Signa Rev. Asoc. Esp. Semiót. 2024, 33, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejo-Veloso, C. Desvíos y confluencias entre el teatro y la performance durante la transición española. Calle 14 Rev. Investig. Campo Arte 2024, 19, 272–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teira Alcaraz, J.M. El audiovisual en escena: Del teatro multimedia al teatro intermedia a través de la videoescena. Actio Nova Rev. Teoría Lit. Lit. Comp. 2020, 4, 129–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpieri, A. Reading the Signs: Towards a Semiotics of Shakespearean Drama. In Alternative Shakespeares; Drakakis, J., Ed.; Methuen: London, UK, 1991; pp. 119–143. [Google Scholar]

- Kowzan, T. El signo en el teatro. In Teoría del Teatro; Bobes Naves, M.C., Ed.; Arco Libros: Madrid, Spain, 1986; pp. 121–153. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Flores, F. El espacio y el tiempo teatrales: Propuesta de acercamiento semiótico. Tropelias Rev. Teor. Lit. Lit. Comp. 1990, 1, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Barrientos, J.L. Cómo Se Comenta una Obra de Teatro; Toma, Ediciones y Producciones Escénicas y Cinematográficas: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lorch, J. Pirandello: Six Characters in Search of an Author; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tordera Sáez, A. Teoría y técnica del análisis teatral. In Elementos para una Semiótica del Texto Artístico; Hernández Esteve, V., Romera, A., Talens, J., Tordera, A., Eds.; Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 1999; pp. 157–199. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquero González, A.; Finol, J.E. Semiótica del espectáculo: Contribución a una clasificación de los elementos no lingüísticos del teatro. Rev. Artes Humanid. UNICA 2007, 8, 281–309. [Google Scholar]

- De Marinis, M. Etienne Decroux and His Theatre Laboratory; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bobes Naves, M.C. Semiología de la Obra Dramática; Taurus Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tessing Schneider, M. Contemporaneity in Historically Informed Performance. In Performing the Eighteenth Century: Theatrical Discourses, Practices, and Artefacts; Tessing Schneider, M., Wagner, M., Eds.; Stockholm University Press: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; pp. 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, M. Da arquitetura teatral e da literatura dramática: Processo metodológico. An. Investig. Arquit. 2024, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, W. Aproximarse al acontecimiento teatral: La influencia de la semiótica y la hermenéutica en los estudios teatrales europeos. Theatre Res. Int. 1997, 22, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, D. Encyclopedia of Phenomenology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Romera Castillo, J. Teatralidad y otredad. Anagnórisi Rev. Investig. Teatr. 2020, 21, 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Ebenhoch, M. Caught in Translation Power Relations The Curious Case of Sister Maria do Céu (1658–1753). Rass. Iberistica 2023, 120, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasseau, J.M. Para un análisis del para-texto teatral. In Teoría del Teatro; Bobes Naves, M.C., Ed.; Arco Libros: Madrid, Spain, 1997; pp. 83–120. [Google Scholar]

- Almada Anderson, H.J. Decorado verbal, ticoscopia y puesta en edición en La entretenida de Miguel de Cervantes. A Escena Rev. Artes Escén. Performatividades 2024, 1, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surgers, A. Escenografías del Teatro Occidental; Ediciones Artes del Sur: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Urrego, A. El teatro posdramático: Rompimiento y creación de un texto literario. Hojas Univ. 2021, 78, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, H.T. Teatro Posdramático; Cendeac: Murcia, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de la Bandera, M.C. Contribución al Estudio Semiótico del Espacio Escénico: (Dialéctica y Formalidad de los Espacios Intra y Extra-Escénicos). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, S. Historia del Teatro Universal; Editorial Losada: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1954; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Macgowan, K.; Melnitz, W. Las Edades de Oro del Teatro; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Coso Marín, M.A.; Higuera Sánchez-Pardo, M.; Sanz Ballesteros, J. El Teatro Cervantes de Alcalá de Henares, 1602–1866: Estudio y Documentos; Tamesis Books Limited: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crespán, A. Institutionalized Violence and Oppression: Ambiguity, Complicity and Resistance in el Campo and the Conduct of Life. Comp. Drama 2024, 58, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogás Puga, G. El enclave metateatral del grotesto en el teatro argentino moderno: Conflicto gnoseológico, ontológico y metateatralidad comparada. Telón Fondo 2016, 23, 52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana, M.S. Las fronteras entre teatro y vida en Seis personajes en busca de autor de Luigi Pirandello. In De Máscaras y Espejos. A Propósito del Metateatro Europeo; Blanco, M.S., Ed.; Universidad Nacional de Jujuy: San Salvador de Jujuy, Argentina, 2013; pp. 49–63. [Google Scholar]

- De Bernardis, I. La influencia de Sterne en Uno, nessuno e centomila, de Luigi Pirandello. Comun. Hombre Rev. Interdiscip. Cienc. Comun. Humanid. 2024, 20, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ferroni, G. Storia della Letteratura Italiana. Il Novecento e il Nuovo Millennio; Mondadori Universitá: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, M. Los personajes de Pirandello: Del espiritismo al cine. Pygmalion Rev. Teatro Gen. Comp. 2012, 4, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pirandello, L. En Confidence. Le Temps, 20 July 1925; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, A.; Tinterri, A. Pirandello capocomico. In La Compagnia del Teatro d’Arte di Roma 1925–1928; Sellerio Editore: Palermo, Italy, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Boscaro, C. Didascalia drammaturgica come luogo dell’autorialità. Dunărea Jos 2023, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Pirandello, L. Luigi Pirandello: Obras Escogidas; Grande, I.; Grande, M.; Velloso, J.M., Translators; Aguilar: Madrid, Spain, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Arias, R.E. El Estructuralismo como modelo epistémico que busca explicar la realidad social. Rev. Venez. Anál. Coyunt. 2018, 2, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Rimoldi, L. El concepto de resignificación como aporte a la teoría de la adaptación teatral. ESCENA Rev. Artes 2012, 70, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Guini, E. Teatro posdramático en tiempos de crisis: Tres ejemplos de teatro-documento y devised theatre. Acot. Rev. Investig. Teatr. 2021, 46, 71–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Molina, A.; Molina Alarcón, M. Teatro posdramático y artes vivas. Bol. Estét. 2022, 59, 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagur-Pons, S.; Paz-Lourido, B.; Rosselló-Ramon, M.R.; Verger, S. El enfoque integrador de la metodología mixta en la investigación educativa. Relieve Rev. Electrón. Investig. Eval. Educ. 2021, 27, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oñoro Otero, C. Cuando el teatro es necesario. Los nuevos formatos teatrales una década después (2009–2019). Signa Rev. Asoc. Esp. Semiót. 2020, 29, 635–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, M.; Vera, A. Transmedia, Teatro y Escenografía. Cuad. Cent. Estud. Diseño Comun. 2024, 224, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Ensayos Críticos; Pujol, C., Ed.; Grupo Editorial Planeta: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Filinezhad, N.; Jamali Nesari, A.; Jamali Nesari, S.; Shahraz, S. A Deconstructive Reading on Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 904–908. [Google Scholar]

- Macías Borrego, M. Una Lectura Shakespeariana de Enrico IV de Pirandello. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Macías Borrego, M. De Hamlet a Enrico IV: Locura, alienación y asesinato como liberación. In La Muerte Violenta en el Teatro; Maestro, J.G., Ed.; Academia del Hispano: Madrid, Spain, 2016; pp. 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- García, P.; Javier, P. El mito de Frankenstein en el cine: Transmediación y ciencia ficción (Blade Runner y 2049). Trasvases Entre Lit. Cine 2020, 2, 9–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaburro, G.; Iannace, G.; Lombardi, I.; Sukaj, S.; Trematerra, A. The Acoustics of the Benevento Roman Theatre. Buildings 2021, 11, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosisio, P. Teatro dell’Occidente. Elementi di Storia della Drammaturgia e dello Spettacolo Teatrale; Led Edizioni Universitarie: Milano, Italy, 2006; Volume I: Dalle Origini al Gran Secolo. [Google Scholar]

- Marchi, V. Teatro Odescalchi a Roma. In L’Architettura Italiana. Periodico Mensile di Costruzione e di Architettura Pratica; Brossura: Torino, Italy, 1926; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pirandello, L. Seis Personajes en Busca de Autor. Cada Cual a Su Manera. Esta Noche se Improvisa; Cuevas, M.A., Luperini, R., Eds.; Ediciones Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Varela, J.A. Historia Visual del Escenario; García Verdugo, J., Ed.; La Avispa: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- López de Gereñu, J. Decorado y Tramoya; Editorial Ñaque: Ciudad Real, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).