Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Rated Health of Older Adults

2.2. Relation Between House Prices and Self-Rated Health of Older Adults

2.3. Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being (SWB)

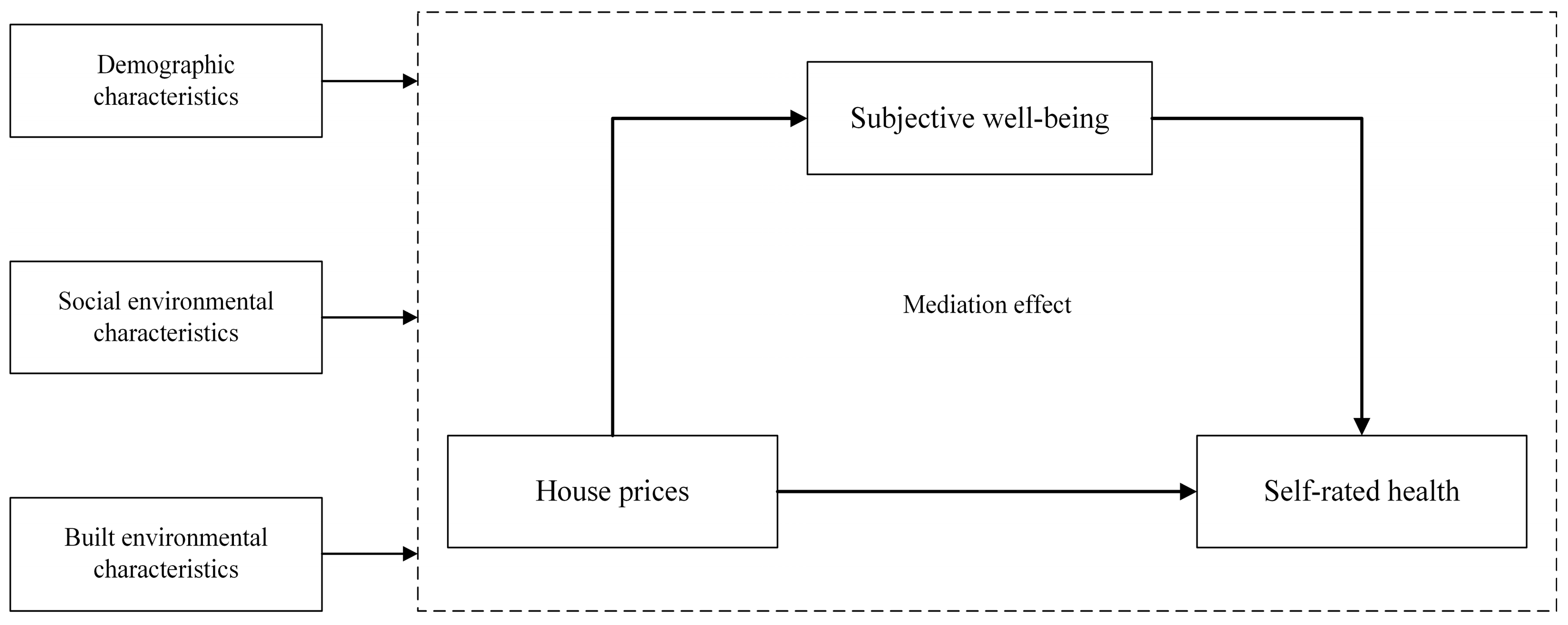

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection and Measurement

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Self-Rated Health

3.2.2. Independent Variable: House Prices

3.2.3. Mediator: Subjective Well-Being

3.2.4. Covariates

3.2.5. Model Specification

4. Results

4.1. Relationship Between House Prices and Self-Rated Health

4.2. Mediating Effect of Subjective Well-Being

4.3. Difference Between Young-Old and Old-Old

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowling, A.; Stafford, M. How Do Objective and Subjective Assessments of Neighbourhood Influence Social and Physical Functioning in Older Age? Findings from a British Survey of Ageing. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2533–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafford, M.; Mcmunn, A.; De Vogli, R. Neighbourhood Social Environment and Depressive Symptoms in Mid-Life and Beyond. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J.R.; Blaney, S.; Cerda, M.; Frye, V.; Lovasi, G.S.; Ompad, D.; Rundle, A.; Vlahov, D. Neighborhood Characteristics and Disability in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B-Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Housing and Health Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Schoenbaum, M.; Waidmann, T. Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Health: Accounting for Race Differences in Health. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1997, 52, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellaway, A.; Macintyre, S. Does Housing Tenure Predict Health in the UK Because It Exposes People to Different Levels of Housing Related Hazards in the Home or Its Surroundings? Health Place 1998, 4, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macintyre, S.; Ellaway, A.; Hiscock, R.; Kearns, A.; Der, G.; Mckay, L. What Features of the Home and the Area Might Help to Explain Observed Relationships between Housing Tenure and Health? Evidence from the West of Scotland. Health Place 2003, 9, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, C.; von dem Knesebeck, O.; Siegrist, J. Housing and Health in Germany. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, S.; House, J.S. SES Differentials in Health by Age and Alternative Indicators of SES. J. Aging Health 1996, 8, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, C.E.; Chideya, S.; Cubbin, C.; Williams, B.; Dekker, M.; Braveman, P. Should Health Studies Measure Wealth? A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Jivraj, S.; Nazroo, J.; Tampubolon, G.; Vanhoutte, B. Does the Level of Wealth Inequality within an Area Influence the Prevalence of Depression amongst Older People? Health Place 2014, 27, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disney, R.; Gathergood, J.; Henley, A. House price shocks, negative equity, and household consumption in the united kingdom. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 1179–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocjan, G.Z.; Avsec, A.; Kavcic, T. Feeling Too Low to Be Active: Physical Inactivity Mediates the Relationship between Mental and Physical Health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 341, 392–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, J.; Dickinson, H.O.; Matthews, F.; Jagger, C.; Brayne, C.; Cfas, M. Self-Rated Health Status as a Predictor of Death, Functional and Cognitive Impairment: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Eur. J. Ageing 2006, 3, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyamini, Y.; Idler, E.L. Community Studies Reporting Association between Self-Rated Health and Mortality: Additional Studies, 1995 to 1998. Res. Aging 1999, 21, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Bang, D.; Cosgrove, S.; Dulin, R.; Harris, Z.; Taylor, A.; White, S.; Yatabe, G.; Liburd, L.; Giles, W.; et al. Surveillance of Health Status in Minority Communities—Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) Risk Factor Survey, United States, 2009. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. Surveill. Summ. 2011, 60, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bombak, A.E. Self-Rated Health and Public Health: A Critical Perspective. Front. Public Health 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Lopez, A.D. Alternative Projections of Mortality and Disability by Cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997, 349, 1498–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, O.; Matthews, S.; Power, C. Dichotomous or Categorical Response? Analysing Self-Rated Health and Lifetime Social Class. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 29, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, A.; Picavet, H.S.; Nossikov, A. Health Interview Surveys: Towards International Harmonization of Methods and Instruments; WHO Regional Publications, European Series, No. 58; Office of Publications, WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1996; Volume 58, pp. 1–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L. Multiple Stereotypes of Elderly and Young Adults: A Comparison of Structure and Evaluations. Psychol. Aging 1990, 5, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmoth, K.; Tarrant, M.; Abraham, C.; Lang, I.A. Older Adults’ Perceptions of Ageing and Their Health and Functioning: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomioka, K.; Kurumatani, N.; Hosoi, H. Self-Rated Health Predicts Decline in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living among High-Functioning Community-Dwelling Older People. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylh, M. What Is Self-Rated Health and Why Does It Predict Mortality? Towards a Unified Conceptual Model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeSalvo, K.; Bloser, N.; Reynolds, K.; He, J.; Muntner, P. Mortality Prediction with a Single General Self-Rated Health Question. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Yoon, H.; Lin, S. Correlates of Self-Rated Health and Self-Rated Mental Health in Older Chinese Americans. Soc. Work. Public Health 2016, 31, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirve, S.; Juvekar, S.; Lele, P.; Agarwal, D. Social Gradients in Self-Reported Health and Well-Being among Adults Aged 50 and over in Pune District, India. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Olive, F.X.; Thorogood, M.; Clark, B.D.; Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.M. Assessing Health and Well-Being among Older People in Rural South Africa. Glob. Health Action 2010, 3, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Kawachi, I. Perceived Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Preventive Healthcare Use. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, E35–E40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Gauvin, L.; Raine, K. Ecological Models Revisited: Their Uses and Evolution in Health Promotion Over Two Decades. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.J.; Lehning, A.J.; Kim, K. Aging in Place in Gentrifying Neighborhoods: Implications for Physical and Mental Health. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, M.; Petticrew, M.; Bambra, C.; Sowden, A.J.; Wright, K.E.; Whitehead, M. Housing and Health Inequalities: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews of Interventions Aimed at Different Pathways Linking Housing and Health. Health Place 2011, 17, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, H.; Thomas, S.; Sellstrom, E.; Petticrew, M. The Health Impacts of Housing Improvement: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies from 1887 to 2007. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99 (Suppl. S3), S681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lofqvist, C.; Tomsone, S.; Iwarsson, S.; Horstmann, V.; Haak, M. Changes in Home and Health over Nine Years among Very Old People in Latvia—Results from the ENABLE-AGE Project. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2017, 32, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.G.; Keller, B.; Hood, N.; Holtzen, H. Affordable Housing and Health: A Health Impact Assessment on Physical Inspection Frequency. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellaway, A.; Macintyre, S.; Bonnefoy, X. Graffiti, Greenery, and Obesity in Adults: Secondary Analysis of European Cross Sectional Survey. BMJ-Br. Med. J. 2005, 331, 611–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Palmer, S.; Gallacher, J.; Marsden, T.; Fone, D. A Systematic Review of the Relationship between Objective Measurements of the Urban Environment and Psychological Distress. Environ. Int. 2016, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, M.; Wendel-Vos, W.; van Poppel, M.; Kemper, H.; van Mechelen, W.; Maas, J. Health Benefits of Green Spaces in the Living Environment: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Grekousis, G.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Neighbourhood Greenness and Mental Wellbeing in Guangzhou, China: What Are the Pathways? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 190, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Feng, Z.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y. Amount of and Proximity to Blue Spaces and General Health among Older Chinese Adults in Private and Public Housing: A National Population Study. Health Place 2022, 74, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stronegger, W.J.; Titze, S.; Oja, P. Perceived Characteristics of the Neighborhood and Its Association with Physical Activity Behavior and Self-Rated Health. Health Place 2010, 16, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.; Shen, Y. Understanding Wealth and Housing Inequality among China’s Older Population. China Econ. J. 2015, 8, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, W.M.; Van Zandt, S.; Mccarthy, G. Home Ownership and Access to Opportunity. Hous. Stud. 2002, 17, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M. Housing and Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 25, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Njai, R.S.; Greenlund, K.J.; Chapman, D.P.; Croft, J.B. Relationships between Housing and Food Insecurity, Frequent Mental Distress, and Insufficient Sleep among Adults in 12 US States, 20309. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, K.; Edwards, R.; Liu, B.Y.J. Effects of House Prices on Health: New Evidence from Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 192, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichera, E.; Gathergood, J. Do Wealth Shocks Affect Health? New Evidence from the Housing Boom. Health Econ. 2016, 25, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, A. Wealth effects, local area attributes, and economic prospects: On the relationship between house prices and mental wellbeing. Rev. Income Wealth 2015, 61, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Q.; Liang, L.-Q. How Do Housing Prices Affect Residents’ Health? New Evidence from China. Front. Public Health 2022, 9, 816372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoudi, A.; Dowd, J.B. Physical Health Effects of the Housing Boom: Quasi-Experimental Evidence From the Health and Retirement Study. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 1039–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toussaint, J. Housing Assets as a Potential Solution for Financial Hardship: Households’ Mental Accounts of Housing Wealth in Three European Countries. Hous. Theory Soc. 2011, 28, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A. Franco Modigliani and the Life-Cycle Theory of Consumption. BNL Q. Rev. 2005, 58, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, A.; Hepburn, K.J.; Lear, S.A.; Adshade, M.; Card, K.G. The Impact of Housing Prices on Residents’ Health: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, A.; Mas, N.; Vergara-Alert, C. Housing Wealth, Health and Deaths of Despair. J. Real. Estate Financ. Econ. 2023, 66, 569–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.; Pham, N.T.A.; Daniel, L.; Bentley, R. New Evidence on Mental Health and Housing Affordability in Cities: A Quantile Regression Approach. Cities 2020, 96, 102455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venti, S.F.; Wise, D.A. Aging and Housing Equity; NBER Working Papers; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Shen, Y.; Liang, H.; Guo, R. Housing and Adult Health: Evidence from Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuyun, C.; Jiankun, Y. Whether Housing Affects Urban Rsidents’ Health Level?—From an Empirical Analysis of Chinese General Social Survey(2015). J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 5, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Solar, O.; Irwin, A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinats of Health; Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.; Lucas, R.; Smith, H. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumannhme, S.; Attema, A.E.; Brouwer, W.B.F.; Exel, J.N.J.A.V. Life Satisfaction: The Role of Domain: Pecific Reference Points. Health Econ. 2021, 30, 2766–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Huang, R.-Y.; Wu, Y.-L.; Yeh, W.-C.; Chang, H.-C. The Impact of Living Arrangements and Social Capital on the Well-Being of the Elderly. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soosova, M.S.; Timkova, V.; Dimunova, L.; Mauer, B. Spirituality as a Mediator Between Depressive Symptoms and Subjective Well-Being in Older Adults. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Chan, M.Y. Happy People Live Longer: Subjective Well-Being Contributes to Health and Longevity. Appl. Psychol.-Health Well Being 2011, 3, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, H.-H.; Lee, T.S.-H. Family Relations, Sense of Coherence, Happiness and Perceived Health in Retired Taiwanese: Analysis of a Conceptual Model. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C.D.; Radler, B.T.; Friedman, E.M. Persistent Psychological Well-Being Predicts Improved Self-Rated Health over 9–10 Years: Longitudinal Evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychol. Open 2015, 2, 2055102915601582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Subjective Wellbeing, Health, and Ageing. Lancet 2015, 385, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamaba, K.H.; Panagioti, M.; Armitage, C.J. How Strongly Related Are Health Status and Subjective Well-Being? Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Gong, S.; Han, Y. How Does Rising Housing Price Affect the Health of Middle-Aged and Elderly People? The Complementary Mediators of Social Status Seeking and Competitive Saving Motive. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurer, K.; Wister, A. Altruistic Behaviour and Social Capital as Predictors of Well-Being among Older Canadians. Ageing Soc. 2010, 30, 157–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, F. Effects of Housing Wealth on Subjective Well-Being in Urban China. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 965–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, C.; Sorensen, B.E. Subjective Well-Being: Keeping up with the Perception of the Joneses. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 109, 439–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foye, C.; Clapham, D.; Gabrieli, T. Home-Ownership as a Social Norm and Positional Good: Subjective Wellbeing Evidence from Panel Data. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1290–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yuan, Z.Q.; Zhang, X. Does Happiness Dwell in an Owner-Occupied House? Homeownership and Subjective Well-Being in Urban China. Cities 2020, 96, 102404.1–102404.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; King, S.P.; Smyth, R.; Wang, H. Housing Property Rights and Subjective Wellbeing in Urban China. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2016, 45, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddy, M.; Gray, F. Filtering Theory, Housing Policy and the Legitimation of Inequality. Policy Politics 1979, 7, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theurer, K.; Ben Mortenson, W.; Stone, R.; Suto, M.; Timonen, V.; Rozanova, J. The Need for a Social Revolution in Residential Care. J. Aging Stud. 2015, 35, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Huang, H.-L. Social Support and the Self-Rated Health of Older People A Comparative Study in Tainan Taiwan and Fuzhou Fujian Province. Medicine 2016, 95, e3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2018; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2018; ISBN 978-7-5037-8587-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cellmer, R.; Belej, M.; Trojanek, R. Housing Prices and Points of Interest in Three Polish Cities. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2024, 39, 1509–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, C.; Kasl, S.V. Can Parental Longevity and Self-Rated Life Expectancy Predict Mortality among Older Persons? Results from an Australian Cohort. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 1998, 53B, S28–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.E.S.; Romaine, C.L.R.; Zelle, H. Psychometric Properties of the Miranda Rights Comprehension Instruments with a Juvenile Justice Sample. Assessment 2011, 18, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, P.C.; Merlo, J. Intermediate and Advanced Topics in Multilevel Logistic Regression Analysis. Stat. Med. 2017, 36, 3257–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H. Multilevel Statistical Models; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipanah, R.; Schulz, A.; Israel, B.; Mentz, G.; Eisenberg, A.; Stokes, C.; Rowe, Z. Neighborhood Context, Homeownership and Home Value: An Ecological Analysis of Implications for Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS Procedures for Estimating Indirect Effects in Simple Mediation Models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, K.; Edwards, R. House Prices, Housing Wealth and Financial Well-Being. J. Urban Econ. 2022, 129, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Kawachi, I. A Prospective Study of Individual-Level Social Capital and Major Depression in the United States. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barefoot, J.C.; Maynard, K.E.; Beckham, J.C.; Brummett, B.H.; Hooker, K.; Siegler, I.C. Trust, Health, and Longevity. J. Behav. Med. 1998, 21, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.-K.; Hong, S.-I. Assets and Life Satisfaction Patterns Among Korean Older Adults: Latent Class Analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 100, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.-L.; Chang, J.-H.; Chen, L.H. Investigating the Relationship between District-Level Socioeconomic Status and Individual Obesity in Taiwanese Adolescents: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, M.H.; Nawawi, A.H.; Sipan, I. Review of Building, Locational, Neighbourhood Qualities Affecting House Prices in Malaysia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 234, 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Wang, Y.; Fan, G.-Z. Home-Purchase Limits and Housing Prices: Evidence from China. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2018, 56, 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonen, H.D.; Sund, E.R.; Ariansen, I.; Krokstad, S. Trends in Socioeconomic Inequalities in Self-Rated Health and Mental Distress during Four Decades in a Norwegian Population: A HUNT Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Zhu, H.; Han, S.; Chen, J.; Shi, L. Impact of House Price Growth on Mental Health: Evidence from China. SSM—Popul. Health 2021, 13, 100696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmazer, T.; Babiarz, P.; Liu, F. The Impact of Diminished Housing Wealth on Health in the United States: Evidence from the Great Recession. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 130, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Yin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Sautter, J.; Qiu, L. Homeownership among Older Adults in Urban China: The Importance of Institutional Factors. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2016, 31, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawhorter, S.; Crimmins, E.M.; Ailshire, J.A. Housing and Cardiometabolic Risk among Older Renters and Homeowners. Hous. Stud. 2023, 38, 1342–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, B.K.; Kim, J.H. Intergenerational Coresidence and Life Satisfaction in Old Age: The Moderating Role of Homeownership. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 3199–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Han, B. Life Satisfaction and Mental Health of Chinese Older Adults in Different Living Arrangements. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Human Health and Biomedical Engineering, Jilin, China, 19–22 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zaninotto, P.; Steptoe, A. Association between Subjective Well-Being and Living Longer without Disability or Illness. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yuan, N.; Hu, H. Housing Quality and Its Determinants in Rural China: A Structural Equation Model Analysis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, T.; Clayton, S.; Neary, D.; Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Crime, Fear of Crime, Environment, and Mental Health and Wellbeing: Mapping Review of Theories and Causal Pathways. Health Place 2012, 18, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, C.; Cole, C.A.; Lee, M.P. Consumer Decision Making and Aging: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 3279) | |

|---|---|

| Age (%) | |

| 55~59 | 23.21 |

| 60~74 | 73.21 |

| 75~89 | 3.52 |

| ≥90 | 0.06 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 40.7 |

| Female | 59.3 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| First marriage/second marriage/cohabitation | 95.9 |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 4.1 |

| Political status (%) | |

| Party member | 6.8 |

| Non-Party member | 93.2 |

| Hukou (%) | |

| Local Hukou | 94.8 |

| Non-local Hukou | 5.2 |

| Individual income in 2017 (yuan) (%) | |

| <18,000 | 65.8 |

| 18,000~35,999 | 21.2 |

| 36,000~59,999 | 6.7 |

| ≥60,000 | 6.3 |

| Homeownership (%) | |

| Homeowner | 97.8 |

| Renter | 2.2 |

| Variable | Cronbach’s α | Standardized Cronbach’s α | Definitions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | 0.857 | 0.950 | Be annoyed by little things |

| I have no appetite and don’t want to eat. | |||

| Even in the favor of family and friends, I still can’t get rid of the depression in my heart | |||

| I don’t think it’s as good as most people | |||

| Inability to be absorbed in when doing things | |||

| Feel depressed | |||

| Feel laborious to do anything | |||

| Feel hopeless in the future | |||

| Feel like your life is a failure | |||

| Feel scared | |||

| Poor sleep | |||

| Feel upset | |||

| Talk less than usual | |||

| Feel lonely | |||

| Feel that people are not very amiable to themselves | |||

| Think life is meaningless | |||

| Once cried | |||

| Feel sad | |||

| Feel that people don’t like themselves | |||

| Feel like life can’t go on | |||

| Community Satisfaction | 0.857 | 0.860 | There are safety risks when hanging out and hanging out |

| Going out alone at night is a safety risk | |||

| Risk of burglary if you don’t lock your doors and windows | |||

| There is a risk of being targeted if wealth is exposed | |||

| Children are at risk of being trafficked when they are alone |

| Index | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Density of Population | The number of individuals per unit area |

| Urbanization rate | The proportion of the total population that resides in urban areas |

| POI density | The ratio of the number of points of interest (POI) within a specific area to the area’s size. |

| Number of tertiary hospitals | Number of urban tertiary hospitals (institutes) |

| Variable | Model 1 Self-Rated Health | Model 2 Subjective Well-Being | Model 3 Self-Rated Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | |

| House prices | −0.214 ** (0.114) | −0.118 (0.076) | −0.227 ** (0.114) |

| Built environment characteristics | |||

| Number of tertiary hospitals | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.009 ** (0.004) | 0.006 (0.004) |

| Point of Interest | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 *** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Density of Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Urbanization Rate | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.002 (0.002) | −0.002 (0.003) |

| Social environment characteristics | |||

| Social trust | −0.081 *** (0.022) | 0.059 ** (0.022) | −0.073 *** (0.022) |

| Community mutual assistance | 0.006 (0.019) | 0.056 ** (0.021) | 0.013 (0.020) |

| Community safety | 0.019 (0.028) | −0.123 *** (0.023) | 0.003 (0.028) |

| Community satisfaction | 0.002 (0.006) | −0.007 * (0.003) | 0.002 (0.006) |

| Freedom of life choice | −0.043 *** (0.011) | 0.087 *** (0.008) | −0.032 ** (0.011) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Mental Health | 0.029 *** (0.002) | −0.020 *** (0.002) | 0.027 *** (0.002) |

| Gender | −0.110 ** (0.038) | −0.079 ** (0.031) | −0.109 ** (0.039) |

| Marital status | 0.110 (0.086) | 0.044 (0.100) | 0.115 (0.086) |

| Political status | −0.083 (0.062) | 0.195 *** (0.050) | −0.059 (0.062) |

| Family income (Yuan/Year) (%) (60,000 income and above ref.) | |||

| Below 18,000 | 0.117 ** (0.075) | −0.002 (0.063) | 0.120 * (0.076) |

| 18,000~35,999 | −0.055 (0.077) | 0.054 (0.067) | −0.049 (0.076) |

| 36,000 and above | −0.106 (0.076) | 0.054 (0.067) | −0.101 (0.077) |

| Hukou | 0.134 * (0.079) | −0.063 (0.064) | 0.127 * (0.070) |

| Age | 0.010 (0.003) | 0.014 *** (0.003) | 0.011 ** (0.004) |

| Age1 (55–69) | 0.623 (0.977) | 0.855 *** (0.102) | 0.740 (0.979) |

| Age2 (≥70) | 0.505 (0.979) | 0.570 *** (0.107) | 0.585 (0.981) |

| Homeownership | −0.041 (0.139) | −0.386 *** (0.091) | −0.091 (0.138) |

| Mediator variable | |||

| Subjective well-being | −0.127 *** (0.024) | ||

| Constant | 1.300 ** (1.023) | 1.975 *** (0.340) | 1.534 (1.019) |

| Observation | 3279 | 3279 | 3279 |

| Proportion of total effect that is mediated | 0.070 | ||

| Ratio of indirect to direct effect | 0.066 | ||

| Variable | Young-Old (55–69 Years of Age) | Old-Old (70 Years of Age and Above) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 Self-Rated Health | Model 2 Subjective Well-Being | Model 3 Self-Rated Health | Model 1 Self-Rated Health | Model 2 Subjective Well-Being | Model 3 Self-Rated Health | |

| Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | |

| House prices | −0.186 * (0.111) | −0.102 (0.078) | −0.200 * (0.113) | −0.933 *** (0.284) | −0.322 (0.310) | −1.004 *** (0.249) |

| Built environment characteristics | ||||||

| Number of tertiary hospitals | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.009 ** (0.004) | 0.005 (0.004) | 0.023 ** (0.010) | 0.007 (0.011) | 0.026 ** (0.010) |

| Point of Interest | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 *** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 ** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Density of Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) |

| Urbanization Rate | −0.002 (0.003) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.012 (0.013) | 0.006 ** (0.013) | 0.010 (0.012) |

| Social environment characteristics | ||||||

| Social trust | −0.071 *** (0.021) | 0.057 ** (0.022) | −0.065 ** (0.022) | −0.206 (0.137) | 0.010 (0.098) | −0.186 (0.143) |

| Community mutual assistance | −0.005 (0.019) | 0.054 ** (0.021) | −0.012 (0.020) | 0.017 (0.122) | 0.101 (0.100) | 0.039 (0.121) |

| Community safety | 0.020 (0.029) | −0.116 *** (0.022) | 0.006 (0.029) | 0.109 (0.149) | −0.332 ** (0.116) | 0.039 (0.161) |

| Community satisfaction | 0.003 (0.006) | −0.006 * (0.003) | −0.002 (0.006) | −0.022 (0.022) | −0.010 (0.019) | −0.024 (0.021) |

| Freedom of life choice | −0.043 *** (0.011) | 0.089 *** (0.008) | −0.032 ** (0.011) | −0.031 ** (0.043) | −0.029 *** (0.009) | −0.028 ** (0.044) |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Mental Health | 0.030 *** (0.002) | −0.019 *** (0.002) | 0.028 *** (0.002) | 0.006 (0.009) | −0.029 *** (0.009) | −0.001 (0.010) |

| Gender | −0.092 ** (0.040) | −0.076 ** (0.030) | 0.101 ** (0.041) | 0.064 (0.172) | −0.145 (0.145) | 0.035 (0.159) |

| Marital Status | 0.110 (0.089) | −0.053 (0.097) | 0.116 (0.089) | −0.076 (0.322) | 0.095 (0.399) | −0.047 (0.289) |

| Political Status | −0.092 (0.064) | 0.200 *** (0.050) | −0.069 (0. 065) | −0.220 (0.353) | 0.192 (0.246) | −0.147 (0.392) |

| Family income (Yuan/Year) (%) (60,000 income and above ref.) | ||||||

| Below 18,000 | 0.137 * (0.075) | −0.004 (0.063) | 0.139 * (0.075) | −0.486 (0.327) | 0.070 (0.434) | −0.526 ** (0.243) |

| 18,000~35,999 | 0.039 (0.076) | −0.064 (0.067) | 0.033 (0.076) | −1.110 ** (0.415) | 0.022 (0.487) | −1.186 *** (0.353) |

| 36,000 and above | −0.100 (0.076) | 0.051 (0.067) | −0.095 (0.077) | −0.325 (0.422) | 0.056 (0.502) | −0.379 (0.370) |

| Hukou | −0.054 (0.144) | −0.067 (0.066) | 0.122 * (0.072) | −0.091 (0.374) | 0.127 (0.422) | −0.027 (0.350) |

| Homeownership | −0.130 * (0.071) | 0.050 *** (0.068) | −0.104 * (0.143) | 1.547 ** (0.631) | −0.777 (0.587) | −1.437 ** (0.617) |

| Mediator variable | ||||||

| Subjective well-being | −0.126 *** (0.026) | −0.247 ** (0.092) | ||||

| constant | 1.872 *** (0.310) | 2.804 *** (0.267) | 2.214 *** (0.322) | 4.448 ** (1.620) | 3.815 ** (1.367) | 5.496 *** (1.543) |

| Observation | 3162 | 3162 | 3162 | 117 | 117 | 117 |

| Proportion of total effect that is mediated | 0.069 | 0.085 | ||||

| Ratio of indirect of direct effect | 0.064 | 0.079 | ||||

| Variable | Model 1 Self-Rated Health | Model 2 Subjective Well-Being | Model 3 Self-Rated Health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | Coef. (SE) | |

| Mean income | −0.120 *** (0.035) | 0.039 * (0.022) | −0.115 *** (0.035) |

| Built environment characteristics | |||

| Number of tertiary hospitals | 0.003 (0.003) | 0.006 ** (0.002) | 0.004 (0.003) |

| Point of Interest | −0.000 (0.000) | −0.000 *** (0.000) | −0.000 (0.000) |

| Density of Population | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.00) |

| Urbanization Rate | −0.003 (0.003) | 0.000 (0.002) | −0.003 (0.003) |

| Social environment characteristics | |||

| Social trust | −0.084 *** (0.023) | 0.061 ** (0.022) | −0.076 *** (0.022) |

| Community mutual assistance | 0.003 (0.019) | 0.053 ** (0.021) | 0.009 (0.019) |

| Community safety | 0.021 (0.028) | −0.126 *** (0.023) | 0.005 (0.028) |

| Community satisfaction | −0.003 (0.006) | −0.006 ** (0.003) | 0.002 (0.006) |

| Freedom of life choice | −0.042 *** (0.011) | 0.086 *** (0.008) | −0.032 ** (0.011) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Mental Health | 0.029 *** (0.002) | −0.020 *** (0.002) | 0.028 *** (0.002) |

| Gender | −0.101 ** (0.039) | −0.078 ** (0.030) | −0.112 ** (0.039) |

| Marital status | 0.103 (0.087) | 0.050 (0.099) | 0.108 (0.087) |

| Political status | −0.077 (0.063) | 0.190 *** (0.050) | −0.052 (0.063) |

| Family income (Yuan/Year) (%) (60,000 income and above ref.) | |||

| Below 18,000 | 0.093 (0.076) | −0.023 (0.062) | 0.096 * (0.076) |

| 18,000~35,999 | −0.070 (0.076) | 0.068 (0.067) | −0.063 (0.076) |

| 36,000 and above | −0.114 (0.075) | 0.053 (0.068) | −0.109 (0.076) |

| Hukou | 0.121 * (0.080) | −0.144 (0.067) | 0.102 * (0.079) |

| Age | 0.010 ** (0.004) | 0.014 *** (0.003) | 0.011 ** (0.004) |

| Age1 (55–69) | 0.609 (1.006) | 0.872 *** (0.103) | 0.727 (1.007) |

| Age2 (≥70) | 0.491 (1.008) | 0.589 *** (0.107) | 0.573 (1.009) |

| Homeownership | −0.042 (0.141) | −0.392 *** (0.089) | −0.092 (0.140) |

| Mediator variable | |||

| Subjective well-being | −0.125 *** (0.024) | ||

| constant | 1.334 *** (1.056) | 1.936 *** (0.342) | 1.569 (1.054) |

| Observation | 3279 | 3279 | 3279 |

| Proportion of total effect that is mediated | 0.040 | ||

| Ratio of indirect to direct effect | 0.042 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Tan, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhuang, X. Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being. Buildings 2025, 15, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010053

Wang M, Tan Z, Chen R, Zhuang X. Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being. Buildings. 2025; 15(1):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010053

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Min, Zixuan Tan, Ruying Chen, and Xuefang Zhuang. 2025. "Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being" Buildings 15, no. 1: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010053

APA StyleWang, M., Tan, Z., Chen, R., & Zhuang, X. (2025). Examining the Impacts of House Prices on Self-Rated Health of Older Adults: The Mediating Role of Subjective Well-Being. Buildings, 15(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010053