Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict and Support on Construction Professionals’ Family Satisfaction: An Integrated Model in Chile

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Work–Family Balance and Family Satisfaction

2.2. Family Satisfaction

2.3. Work–Family Conflict and Family–Work Conflict

2.4. Social Support as a Resource for Reducing Conflict

2.5. Influence of Family Support on Family Satisfaction

2.6. Influence of Organizational Support on Family Satisfaction

2.7. Regulatory Framework in Chile: Work–Family Support Policies

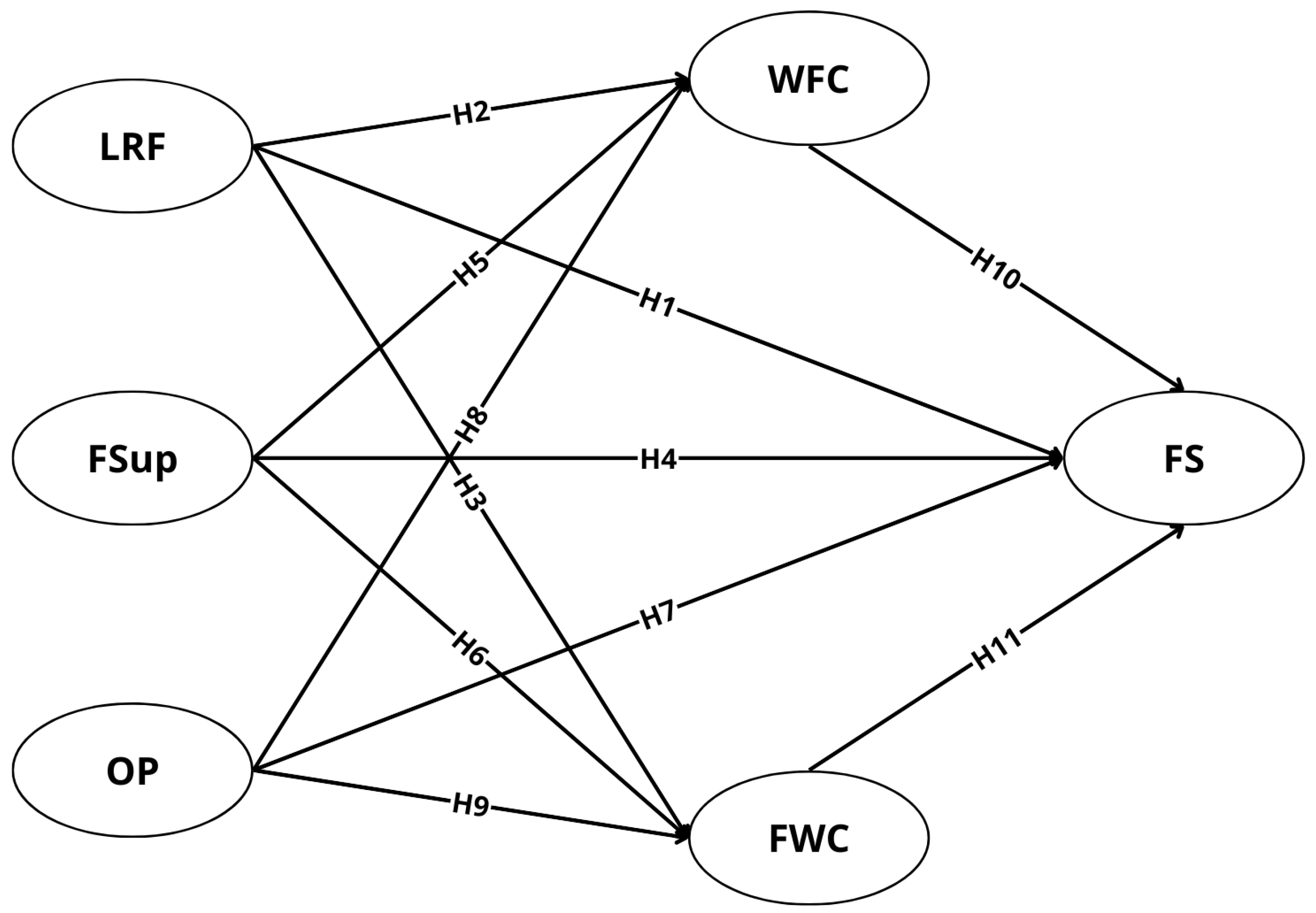

3. Theoretical Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Definition of Key Concepts

3.2. Justification of the Theoretical Model

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling

4.1.1. Evaluation of Reflective Model Measurements

4.1.2. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.2. Questionnaire

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation of the Reflective Model Measures

5.2. Discriminant Validity Assessment

5.3. Assessment of Collinearity Among the Constructs

5.4. Final Path Coefficients

5.5. Effect Size and Predictive Power

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción. Informe Anual: Desarrollo y Desafíos del Sector Construcción en Chile; CChC Publications: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V.; Turner, M. Work-family conflict in construction: Case study insights. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, M.; Chan, Y.S.; Yu, J. Integrated model for the stressors and stresses of construction project managers in Hong Kong. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. Work stress in the construction industry: A review of the literature. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 266–276. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, C. Job stress and work-life balance in construction: Evidence from Korea. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, N.; Xie, Q.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L. A study of occupational stress and satisfaction among construction workers in China. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2014, 24, 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.T.; Skitmore, M.; Leung, T.K.C. The influence of work-family balance policies on work-life balance and well-being: Evidence from Hong Kong. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 292–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. The work-life experiences of office and site-based employees in the Australian construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2013, 31, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y. Family and job interactions in construction: Stress perspectives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017042. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. Work–Life Balance and the Implications for Employee Well-Being. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. 2017. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Lingard, H.; Francis, V. Managing Work-Life Balance in Construction; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan J y West, C.P. Cambios en el agotamiento y la satisfacción con el equilibrio entre el trabajo y la vida personal en médicos y la población activa estadounidense en general entre 2011 y 2015. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P., Jr.; Mosley, D.C., Jr.; Carr, J.C. The impact of work/family demand on work-family conflict. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Trabajo y Previsión Social. Informe Anual: Condiciones Laborales y Bienestar en Chile; Ministerio del Trabajo Publications: Santiago, Chile, 2021.

- Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Valcour, M.; Den Dulk, L.; Kossek, E.E. Theorizing national context to develop comparative work-family research: A review and research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2013, 31, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.E.L.; Bruck, C.S.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D. Work-family balance: A review and extension of the literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 80, 248–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kossek, E.E.; Valcour, M.; Lirio, P. he sustainable workforce: Organizational strategies for promoting work-life balance and well-being. Psychol.-Manag. J. 2012, 15, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Neal, M.B.; Newsom, J.T. A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples’ role conflicts and role facilitation on work and family satisfaction. J. Marriage Fam. 2016, 69, 744–758. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Kacmar, K.M. The relationship of schedule flexibility and outcomes via the work-family interface. J. Manag. Psychol. 2018, 33, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Shockley, K.M. Meta-analysis of work-family conflict and family-work conflict: An examination of antecedents and outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Baltes, B.B.; Matthews, R.A. How work-family research can finally have an impact in organizations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 4, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Concha-Salgado, A.; Orellana, L.; Saracostti, M.; Beroiza, K.; Poblete, H.; Lobos, G.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Lapo, M.; Riquelme-Segura, L.; et al. Workload, job and family satisfaction in dual-earning parents with adolescents: The mediating role of work-to-family conflict. Behav. Sci. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrin, P.; Duncan, K.; Hughes, R. Family satisfaction as a component of life satisfaction: The role of work-family balance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2012, 2, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Eby, L.T.; Casper, W.J.; Lockwood, A.; Bordeaux, C.; Brinley, A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 124–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Kiburz, K.M.; French, K.A. The work-family interface: A look at life satisfaction and burnout. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Viswesvaran, C. Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 67, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L. Social support as a resource for managing work-family conflicts in demanding industries. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 345–360. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.A.; Taylor, R.B.; Johnson, M. The role of family support in mitigating occupational stress. J. Fam. Stud. 2015, 21, 198–212. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä, L.; Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T. Job demands and resources as antecedents of work-to-family conflict and enrichment: The role of affective organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 356–366. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.; Mariani, M. Strategies for managing work-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and outcomes: Examining individual and organizational differences. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 1040–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Family, work, work-family spillover, and problem drinking during midlife. J. Marriage Fam. 2000, 59, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superintendencia de Seguridad Social (SUSESO). Informe Anual sobre Riesgos Psicosociales en el Trabajo; SUSESO Publications: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff, P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. J. Marriage Fam. 2004, 66, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio del Trabajo y Previsión Social. Informe Sobre la Ley de Protección al Empleo; Ministerio del Trabajo y Previsión Social: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile. Análisis de la Ley de Teletrabajo y Trabajo a Distancia; Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción (CChC). Propuestas Para Mejorar la Conciliación Trabajo-Familia en el Sector Construcción; CChC Publications: Santiago, Chile, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Poelmans, S.; Beham, B. The moment of truth: Conceptualizing managerial work-life policy allowance decisions. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollier-Malaterre, A.; Valcour, M.; den Dulk, L.; Kossek, E.E. The fit between organizational culture and work-life policies: An integrated framework. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 52, 305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Randel, A.E.; Stevens, J. The role of identity and work-family support in work-family enrichment and its influence on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 69, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.S.; Kacmar, K.M.; Williams, L.J. Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work-family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2000, 56, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R.; Russell, M.; Cooper, M.L. Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E.W.; Côté, S. Organizational commitment and the contingent value of supportive climates: Effects on work stress and turnover intentions. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 223–247. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P.; Pearson, A.W.; Keough, S. Work-family conflict: A model of linkages between work and family domain variables and turnover intentions. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Boyar, S.L.; Wagner, T.A.; Petzinger, A.; McKinley, R.B. The impact of family roles on employee’s attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. 2015. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 19 November 2024).

- Geisser, S. A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M. Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1974, 36, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research; Marcoulides, G.A., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Estrada, J.M.V.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pampliega, A.; Merino, L.; Jiménez, I. Validación de la escala de apoyo familiar percibido. Psicothema 2006, 18, 378–384. [Google Scholar]

- Zabriskie, R.B.; Ward, P.J. Satisfaction with family life scale. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2003, 30, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Guerrero, R.; Reyes-Lagunes, I.; Wintrob, R. Psicología del Mexicano: Resiliencia, Fortaleza y Adaptación; Siglo XXI Editores: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S.C. Work cultures and work/family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Casper, W.J.; Matthews, R.A.; Allen, T.D. Family-supportive organizational perceptions and work-family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 752–770. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Characteristic | Quantity | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 140 | 28% |

| Male | 359 | 71.8% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Age | 18–25 years | 30 | 6% |

| 26–35 years | 160 | 32% | |

| 36–45 years | 160 | 32% | |

| 46–55 years | 130 | 26% | |

| 56+ years | 20 | 4% | |

| Experience | 0–2 years | 20 | 4% |

| 3–5 years | 90 | 18% | |

| 6–10 years | 180 | 36% | |

| 11–15 years | 110 | 22% | |

| 16+ years | 100 | 20% | |

| Marital status | Single | 150 | 30% |

| Married or steady partner | 280 | 56% | |

| Divorced | 50 | 10% | |

| Widowed | 20 | 4% | |

| Number of children | 0 | 150 | 30% |

| 1 | 130 | 26% | |

| 2 | 100 | 20% | |

| 3 | 70 | 14% | |

| 4+ | 50 | 10% | |

| Education level | Technical–professional | 150 | 30% |

| University education | 220 | 44% | |

| Graduate studies | 100 | 20% | |

| Doctorate | 30 | 6% |

| Construct | Indicator | Abbreviation Indicator | Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Satisfaction (FS) | In most respects, my family life is close to my ideal. | FS1 | 0.752 |

| The conditions of my family life are excellent. | FS2 | 0.739 | |

| I am satisfied with my family life. | FS2 | 0.802 | |

| So far, I have achieved the important things I want in my family life. | FS4 | 0.758 | |

| If I could put my family life back together, I would change almost nothing. | FS5 | 0.809 | |

| Family support received (FSup) | I get the emotional help and support I need from my family. | FSup1 | 0.887 |

| I can talk about my problems with my family. | FSup2 | 0.841 | |

| My family is willing to help me make decisions. | FSup3 | 0.890 | |

| My family provides practical support when I have work responsibilities that affect my time at home. | FSup4 | 0.895 | |

| Organizational Support (OS) | My supervisor understands my family demands. | OS1 | 0.705 |

| My coworkers understand my family demands. | OS2 | 0.679 | |

| My organization offers policies and resources that help me balance my work and family responsibilities. | OS3 | 0.655 | |

| Work–Family Conflict (WFC) | My job or career interferes with my domestic responsibilities, such as cooking, grocery shopping, childcare, gardening, or home repairs. | WFC 1 | 0.823 |

| The demands of my job interfere with my private life. | WFC 2 | 0.854 | |

| My job or career prevents me from spending as much time with my family as I would like. | WFC 3 | 0.855 | |

| My job creates tensions that make it difficult for me to fulfill my family obligations. | WFC 4 | 0.953 | |

| Family–Work Conflict (FWC) | My family life interferes with my ability to fulfill my work responsibilities. | FWC 1 | 0.865 |

| Spending time with my family makes it harder for me to focus on my work tasks, which sometimes impacts the work environment. | FWC 2 | 0.869 | |

| Family responsibilities affect my work performance. | FWC 3 | 0.853 | |

| My family commitments make it difficult for me to concentrate on my work. | FWC 4 | 0.981 | |

| Legal Regulatory Framework (LRF) | How often do you work late every day to leave on Fridays at 3 pm? | LRF 1 | 0.745 |

| How often do you have the option of early arrival and early departure? | LRF 2 | 0.779 | |

| How often can you change your lunchtime to start later or finish the workday earlier? | LRF 3 | 0.815 | |

| How often do you use paid parental leave outside of the post-natal period? | LRF 4 | 0.747 | |

| How often do you apply for paid marriage leave? | LRF 5 | 0.737 | |

| How often do you access paid leave to care for dependents’ illnesses? | LRF 6 | 0.740 | |

| How often do you go on paid family outings? | LRF 7 | 0.719 | |

| How often do you attend paid training during your working day? | LRF 8 | 0.774 | |

| How often do you use unpaid leave for training or personal projects? | LRF 9 | 0.796 | |

| How often do you take extended unpaid work breaks for training or personal reasons? | LRF 10 | 0.805 | |

| How often does your company implement policies that facilitate your commute from home to work? | LRF 11 | 0.855 |

| Construct | Alpha | ρ_A | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS | 0.816 | 0.827 | 0.871 | 0.759 |

| FSup | 0.761 | 0.779 | 0.786 | 0.597 |

| OS | 0.565 | 0.638 | 0.586 | 0.505 |

| WFC | 0.776 | 0.787 | 0.869 | 0.688 |

| FWC | 0.831 | 0.837 | 0.899 | 0.747 |

| LRF | 0.878 | 0.890 | 0.910 | 0.810 |

| Construct | FS | FSup | OS | WFC | FWC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSup | 0.785 | ||||

| OS | 0.818 | 0.890 | |||

| WFC | 0.759 | 0.415 | 0.773 | ||

| FWC | 0.720 | 0.785 | 0.765 | 0.660 | |

| LRF | 0.405 | 0.415 | 0.788 | 0.692 | 0.685 |

| Construct | VIF |

|---|---|

| FSup | 2.600 |

| OS | 2.750 |

| WFC | 2.750 |

| FWC | 2.300 |

| LRF | 1.300 |

| Construct | Original Sample (β) | T Statistic | p Values | Confidence Interval (5%) | Confidence Interval (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LRF → FS (H1) | 0.790 | 9.350 | 0.000 | 0.738 | 0.842 |

| LRF → WFC (H2) | −0.700 | 8.500 | 0.000 | −0.748 | −0.652 |

| LRF → WFC (H3) | −0.705 | 8.800 | 0.000 | −0.752 | −0.658 |

| FSup → FS (H4) | 0.630 | 8.100 | 0.000 | 0.585 | 0.675 |

| FSup → WFC (H5) | −0.580 | 8.900 | 0.000 | −0.634 | −0.556 |

| FSup → WFC (H6) | −0.595 | 7.300 | 0.000 | −0.640 | −0.550 |

| OS → FS (H7) | 0.045 | 1.600 | 0.110 | −0.025 | 0.115 |

| OS → WFC (H8) | −0.535 | 6.300 | 0.000 | −0.619 | −0.451 |

| OS → FWC (H9) | −0.560 | 6.750 | 0.000 | −0.612 | −0.508 |

| WFC → FS (H10) | −0.750 | 9.400 | 0.000 | −0.796 | −0.704 |

| FWC → FS (H11) | −0.770 | 10.400 | 0.000 | −0.816 | −0.724 |

| Construct | f2 | Q2 |

|---|---|---|

| FSup | 0.390 | |

| OS | 0.140 | |

| WFC | 0.210 | |

| FWC | 0.190 | |

| LRF | 0.370 | |

| General Predictive Relevance | 0.470 |

| FS Indicator | R2 | RMSEpls | Q2-Predict | RMSElm | RMSEpls-RMSElm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS1 | 0.780 | 0.482 | 0.594 | 0.368 | 0.114 |

| FS2 | 0.279 | 0.538 | 0.281 | 0.072 | |

| FS3 | 0.595 | 0.431 | 0.428 | 0.012 | |

| FS4 | 0.341 | 0.399 | 0.401 | 0.243 | |

| FS5 | 0.512 | 0.569 | 0.566 | 0.014 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neculman, B.; Sierra-Varela, L.; Schnettler, B.; Villegas-Flores, N. Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict and Support on Construction Professionals’ Family Satisfaction: An Integrated Model in Chile. Buildings 2025, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010014

Neculman B, Sierra-Varela L, Schnettler B, Villegas-Flores N. Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict and Support on Construction Professionals’ Family Satisfaction: An Integrated Model in Chile. Buildings. 2025; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeculman, Briguitte, Leonardo Sierra-Varela, Berta Schnettler, and Noé Villegas-Flores. 2025. "Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict and Support on Construction Professionals’ Family Satisfaction: An Integrated Model in Chile" Buildings 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010014

APA StyleNeculman, B., Sierra-Varela, L., Schnettler, B., & Villegas-Flores, N. (2025). Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict and Support on Construction Professionals’ Family Satisfaction: An Integrated Model in Chile. Buildings, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15010014