Abstract

Cyprus with its rich cultural heritage has been the showcase of ornamentation throughout history with a rich variety of materials, details, and narratives. Integrating ornamentation with its body architecture can be seen as one of the storytellers of these narratives through design elements. After the mid-1990s when casinos had been banned in Turkey, five-star casino hotels became one of the main investment areas in North Cyprus. Together with this new building type and new users’ expectations with a new understanding of holidays, the 21st century brought the changing use of ornamentation in hotel interiors and, hence, decoration came to the fore more than before. Hotel lobbies welcoming the users to their second homes and introducing the hotels’ identities have always been seen as the most important area of hotels by investors, designers, and hotel managers. Sometimes the reception areas were perceived as the living room of the hotel customers where they feel attached culturally, socially, or economically, and sometimes it could be a place where they can feel themselves as one of the characters of ancient history, a king or a queen for a while. Hence, hotel interiors, in general, and hotel lobbies, in particular, acted as a cultural representative, a social status symbol, and a political image of the story told. The aim of this paper is to examine five-star hotel lobbies within the framework of ornamentation through a reading model created with the concepts used by theoreticians. Together with the site visits and visual recordings, the analysis conducted in this paper is based on qualitative data incorporated by a rich theoretical background on ornamentation. The paper tries to highlight the representational value of ornamentation that can help to understand and interpret the spatial transformation of hotel interiors.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of their existence, humans have added ornamentation to their lives. This process has been applied in many different areas such as clothing, living spaces, objects, surfaces, and vehicles, starting from the human body [1]. The ornamentation applied in different places varies according to the conditions of the time, ethnic values, material and spiritual conditions, geography, social and political experiences, and many different factors such as ethical values. Architecture is the main discipline among all diversification in which ornamentation varies conceptually over time. Time has been the most important witness to changes in the adornments applied in architectural and interior spaces. Many important architects and theorists have provided criticisms and interpretations in this regard, both theoretically and practically. Different and contradictory thoughts produced from these works show that the most important factor in determining right/wrong depends on the personal background of the designer and the user.

Cyprus is an island with very different cultural heritage values, with its rich cultural infrastructure in the history of ornamentation. In addition to the existing built environment that combines different civilizations from the past, there has been a lot of recent construction in the field of architecture. Tourism is one of the emerging investment sectors of Cyprus due to the advantage of its geography and the use of casino hotels as a revenue source strategy in the economy. Over time, hotels with higher bed capacities are being built on the island, and this has become a major source of income for the country’s economy [2].

Hotels are also the most significant building type in which ornamentation is emphasized in new buildings on the island. Ornamentation has also been culturally representative, an aesthetic element, a story source, a social element, or a political image for these buildings. It has been understood from the studies conducted on Northern Cyprus that all expenditures made for international tourists positively affect the tourism industry and can bring high income to institutions and the sector [3]. From this perspective, it can be said that very ambitious architectural designs with large budgets in hotels without being too modest is a sales and marketing strategy. Ornamentation is an important element in the design of hotel spaces within this aspect [4].

However, Northern Cyprus hotels, with their intricate ornaments, have not been thoroughly examined in academic contexts. While the article ‘Postmodernist Hotel-Casino Complexes in Northern Cyprus’ by Yücel-Besim et al. [5], lists postmodern hotel buildings based on their architectural styles, it does not touch upon ornamentation. Traditional studies of Northern Cyprus ornaments prevail in the literature, lacking exploration of contemporary Northern Cyprus ornaments (such as the master thesis by Zehra Öngün ‘Ornamentations in Interior spaces (case study: old houses in Nicosia)’—1998 [6] and Cemile Çakmak Aydınlı’s book ‘Ornamentation in traditional Cyprus Houses’—2015) [7]. Despite the popularity of contemporary period decorations in international publications, there remains a significant deficiency in the study of hotel buildings, particularly, interiors. Thus, this article aims to address this gap by examining contemporary ornamentation in Northern Cyprus casino hotel interiors.

This study addresses the meaning and approach of ornamentation from the beginning of the contemporary period to today’s architecture. These issues, which are discussed in a conceptual context in the chronological process, are interpreted with respect to the tourism space decorations designed after 2000 in Northern Cyprus, accompanied by the resulting data. It is observed how the ornamentation used in hotels, which serve as nature/culture/entertainment services, is applied in Northern Cyprus. Ornamentation is also analyzed by its use in new world conditions and superior technology possibilities.

For this reason, within the scope of the applied method, ornamentations in the entrance, lobby, and reception as welcoming areas of five-star hotels are studied in Northern Cyprus. In this paper, the relationship and contradictions between contemporary and traditional styles of ornamentation are discussed. Additionally, it is intended as a way to read all the different ideas in a conceptual context. Another aim of the study is to understand not only the formal structure of the ornament but also the meanings it represents. It is believed that understanding how the decorations in hotel spaces reach the place and the people is very important for future hotel designs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ornamentation in the Contemporary Period

Ornamentation is an important part of works of art in all cultures. In the field of decoration of today’s architecture, there are many different complex styles and design trends. In these trends, ornamentation is one of the most common tools used in general character adaptation. This ornamenting work is an issue that requires deep investigations into its structure, use, and sociocultural effect [8]. Franz Sales Meyer collected the decoration elements mentioned in the book entitled ‘A Handbook of Ornament’ under headings such as ‘geometric lines’, ‘natural elements’ (plants, fruits, and human and animal figurines), ‘artificial objects’, and ‘symbols’. The method that must be applied to arrange the points and lines in motifs, to combine them as in geometric shapes, is no different from the process of formation of any design. In this process, the motif in the ornament is formed by the application of design principles and elements such as a certain order, and balance [9].

The use of ornamentation in architecture has long been a source of debate with respect to architectural aesthetics. Ornamentation is generally defined as the preparation of objects that are functionally completed for visual enjoyment or cultural significance [10]. In the debate about functionalism in architectural design at the end of the 19th century, Louis Sullivan claimed that ornamentation brought liveliness and individuality to buildings. Sullivan, who believed in the priority of function, also argued that the application of ornamentation with this approach makes a significant contribution to the building. The use of floral ornaments in the buildings of Sullivan comes from this idea [11]. At the beginning of the twentieth century, designers revised the concept of ornamentation. Architect Adolf Loos, in his 1908 article, ‘Ornament and Crime’, argued that the most important feature of the early twentieth century was the absence of ornaments in design, writing that in the new world order, ornamentation is no longer an element that designers should apply [12]. Similarly, Venturi commented on ‘how modernism is associated with a minimalist approach’, suggesting there is not much room to add historical symbolism to a modern-style building. Venturi’s buildings were different from each other. Certain historical factors from a particular region contributed to the symbolism that Venturi included in his work. As he intended to incorporate symbolism in his designs, he appreciated and understood a wide range of traditionally inspired buildings. The symbolism he used in his traditional hybrid architecture, which he tried to apply for himself, stems from elements such as local materials, regional construction traditions, and climate [13].

Antonio Gaudi is one of the important architects of Art Nouveau, a movement that is widely accepted as the beginning of contemporary (architectural) design after Arts and Crafts. He mentioned the importance of ornamentation by talking about the representative mission of humans, life, and nature, and explained that the ornaments depict a tale in their work. Art Nouveau comprises art that is known for its asymmetry and is decorated by plants, birds, insects, and geometric forms. Nature, geometry, city art, Islamic art, and Japanese art were the sources of inspiration for this style [14].

Henry van de Velde became aware of the importance of technology and engineering in the contemporary era. Instead of the complete rejection of ornamentation, he supported the concept of ‘abstract ornamentation’, in which the lines and colors are balanced. He believed that ornamentation should be interpreted in a contemporary way. This situation, which can also be seen between different attitudes and approaches, shows that the adoption of modernism does not happen all at the same time. The ‘ornamentation and function’ relations were mentioned by August Schlegel in the first decades of the 20th century While discussing the concept of aesthetics, Schlegel put forward one of the three basic elements of a structure, together with the requirements and ornamentation, as well as the Vitruvian logic of function [15].

Products that are manufactured by industrial production conditions, completely free of decoration and functional, form the expression of the age. Loos, who opposed ornamentation with this thought, stated that a style of his own already existed. In his writings, he explained that the ornament, which causes unnecessary time and labor, belongs to the past, and also criticized it for not being economical. According to this view, he believed that ‘the element that should be in decoration is not an ornament, but the real material itself’. These thoughts help to understand the importance Loos attaches to materials in design [16].

Pugin is one of the most important architects of the 19th century. He discussed the idea of ‘direct transfer of material’ in his designs in the Gothic Revival style for which he was the pioneer. In his principles, there were concepts such as ‘from pure material’, ‘from the structure’, ‘from the function’, and ‘the spirit of the time’. In this way, it was ensured that future modernist generations would avoid decoration in their designs [6]. In the argument that ‘form follows function’, Sullivan mentioned the priority of function in design and showed that he did not close the doors to ornamentation by using floral-patterned ornaments in his buildings [11].

Ruskin believed that ornamentation represented spiritual communication between man and God. He also cared about the narrative side of ornamentation in the 19th century. He thought there was a parallel relationship between the quality of ornamentation and the quality of craftsmen. High-quality ornamentation improves the quality of the craftsman. He mentioned that craftsmen create a narrative in ornamentation and qualify this as the appearance of history. This made these narratives sacred, and Ruskin strongly criticized the iron structures formed during the Industrial Revolution [12].

In opposition to Ruskin’s thoughts, Le Corbusier fully supported the architecture and conditions of the period in his work ‘Towards an Architecture’. He analyzed the industrial process and products formed in the new social structure and devised the architectural principles that reference this process. In his designs, he created a composition with the principles of mathematical order, Plato’s splendor, fiction, harmony, etc. He also wrote that meaningless ornaments did not belong to the age [11]. Like Loos, he did not adopt ornamentation and considered it unnecessary because it did not contribute to architecture. He believed that ornamentation was part of a dead understanding such as old architecture [17]. Le Corbusier did not change his attitude toward ornamentation. He described the ornaments of the Ottoman mosques’ interiors with the words ‘majestic coat of whitewash’. During his trip, he drew modernist-looking city sketches, and these actually reflected reality [18].

Frank Lloyd Wright’s ornamentation, integrated with the structure and sometimes containing Art Deco lines, established the human–nature relationship in its basic principles. It also involved designs that opened the building to its surroundings. Wright used the ornament with the materials. In facade aesthetics, his method defined the interior–exterior and semi-open spaces with their surroundings, which were spread out toward nature. Further, organic structures that were integrated with the location, as if they were a part of the building, were revealed. Wright accepted ornamentation, which he saw as the abstract rhythm of the building, as part of the building elements in the interior. He also created an aesthetic concept called ‘machine aesthetics’, inspired by the conditions of the period [11].

Walter Gropius explained that people chose rationalization as a method of purification by nature, and that visual history in architecture should be rationalized and purified. He said that with the purification of the new architecture, the quality of the structural functions will be increased, be sensible, and will create a clearer and more economical approach to solutions. Gropius saw the ornament as a dream and strongly emphasized that Bauhaus-style ornaments would have no place [19].

Robert Venturi saw the ornamentation as symbols of the building telling the story, and he included everything he liked in history in his designs. He became the advocate of using history in design and considered the narrative in ornamentation as a symbolic representative, not as its real view. According to him, history was the most powerful reference used for the design of buildings, and therefore his buildings were different from the modernist logic [13]. Postmodernists reject the strict rules set by the early modernists and argue that construction techniques, forms, and stylistic references make sense. Intelligence, embellishment, and reference were a harbinger of return. The return was as valid for interior spaces as it was for facades. This style is also defined as ‘neo-eclectic’, with the introduction of architectural reference (the narrator of culture and identity) and ornamentation to the buildings. The idea of ‘less is more’, which believes in the necessary and minimal use of materials and rejects the existence of decoration, has now been replaced by Robert Venturi’s sentence ‘less is a bore’ [20]. Technology has been used as a tool in architecture, especially in the 21st century with ‘computer-aided design’ and different computer programs, and consequently, architecture has been brought into a whole new era. Designs are no longer like the old ones. Both architectural and decorative forms can be designed and produced using many different scopes. Symbolic embellishments representing social status, prestige, title, and distinctive figures can be produced much more easily using advanced digital technology [21].

Massey wrote that ornamentation, which was shown as an obstacle to the advancement of society in the last century, has an important role in the advancement of today’s technology. All industrial methods used for parametric architecture were able to produce materials such as repeating ornaments, similar pattern lights, and common number production. (In fact, Frank Gehry gave us clues about today’s conditions in the story of the formation process of the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum.) Opincariu, who defines ornament as a means of communication, wrote that the meanings of the exterior facades are not just as seen. According to him, these ornaments are a mirror that shows the material capacity and technical logic in the new conceptual framework [22].

According to Levit, ornamentation contributes to the comfort of products that are difficult to apply and also to the production of molds in assemblies. According to the definition of Fairhurst, ornamentation is the function of architecture today [23]. Antoine Picon wrote that ‘modern ornamentation seems to emphasize the tactile quality rather than its functional function’. He explained that with the use of modern ornamental devices, a sense of touch can be felt in the visual perception. He relates this to the hypnotic effect experienced by humans with respect to the 1960’s Op Art movement [24].

2.2. Ornamentation as Representation

‘To represent’ literally means to express or describe with a term, character, symbol, or similar entity. It is also known as visualizing or depicting in the mind, i.e., presenting. Hans-Georg Gadamer defines ornamentation as decoration and representation. He explains that sometimes when used alone, even objects without any context can represent the context of life in decorated spaces. In his work, Gadamer describes ornamentation as the pleasure of those who attract attention with the visual show it creates and then experience it, by making the audience look at the whole picture in a cultural context through decoration [25].

By using representations, one can have experiences not only with the real object but also with its depiction in another environment. The fact that representatives have an active role in social and cultural structures, allowing architects to speak on these issues, actually means that architects have a language of expression [26]. From this point of view, architects can be representatives who tell the design stories of buildings in an artistic context, and the ornament used in this story is considered the most important decoration element.

Picon explained in detail the concept of ‘power’ that he embellished in his work. First of all, he argued that ornamentation is a sign of wealth, and mentioned that it deals with social status as the indicator of authority in the places where it is used. The ornamentation used in the past in monarchies, religious buildings, or aristocratic families has not lost its influence today and is also seen in buildings that are intended to convey a message of power and wealth, such as public or corporate business buildings [27]. In their book entitled ‘The Function of the Ornament’, Farshid Moussavi and Micheal Kubu, like Pugin, saw ornamentation as a representative tool in architecture and wrote that the mentioned representational functions are indicators of the political and socio-economic status of the owners of the ornaments [28].

At the end of the 19th century, modernist architects rejected this symbolic style, and subsequently, many representations such as history, astronomy, mythology, and animal figures in interior spaces disappeared over time [27]. Representation in architecture, the story to be told, can refer to the past, as well as approaches to the present and the future. Here, the representative begins to represent designers’ experiences according to physical data such as an architectural element or space. This process is generally the interpretation phase. Apart from the one-to-one transfer method of symbolic figures, in the works called ‘Ideantal Representation’, there are interpretations developed with the designer’s lines that emerge as a result of the act of representation [29].

According to Mihaela Criticose [30], ornamentation has a transfer mission that transforms thought into a phenomenon and helps the observer to perceive the space. In this transfer process, it sometimes finds itself through a presence in space and sometimes through abstract representations. Thus, she characterizes ornamentation as a ‘means of meaning’. In addition, she discusses the function of ornamentation that harmonizes the object and completes the object with the whole. ‘Visual thinking’, which designers constantly use to better understand the visual representation of designs, is interpreted through the interaction of both internal and external visual representations [31]. From this perspective, it can be derived that ornamentation is a visual tool used in the process of transferring the meaning and thoughts in representation, directly or metaphorically.

By dint of modern construction techniques and technology, the use of building materials freely produced in any pattern allows today’s architects to reflect their inspiration in their designs. In Jean Nouvel’s architecture, it is frequently seen that, especially, Islamic geometric patterns are applied and represented with contemporary building techniques. Patterns can be used multi-dimensionally, and in the application of the newest materials and methods. They represent both the cultural heritage of the region where the design is located and the current conditions of the new world we live in [32]. It is seen that Nouvel also applied this ‘cultural representative’ approach in his designs in Islamic regions as well. At this stage, it is understood that there is a close parallel relationship between the conceptual approach and representation. When all the experiences that have been or will be experienced in past, present, and future timelines are read through embellishment, some postmodern conceptual approach ideas emerge.

2.3. Postmodern Hotel Interiors and Ornamentation

The development of ornamentation in the contemporary period has affected hotel architecture as well as all building types. The process started with plain buildings devoid of ornamentation in the modern period, and then with the advent of the ostentatious postmodern movement, hotel architecture became completely different. As a result of advanced technology and high construction opportunities, ornamentation has become not only a process applied to the building, but the building itself. Buildings that could not be built before have become possible. Particularly the Las Vegas adventure has brought irreversible radical innovations to the architecture of the whole world in the hotel industry. The ‘designer hotel trend’, used in thematically designed entertainment industry buildings such as The Walt Disney Company and Universal Studio, has been well suited to Las Vegas architecture. Vegas hotels, combined with casino and entertainment services, are philosophically designed with a ‘replicature’ approach. In this way, opportunities have been created where ornamentation can be applied to the maximum extent during the design process [33].

In the postmodern era, where history is one of the important elements that will guide design in a conceptual context, ornamentation has pioneered the transfer of past ties. As can be understood from Venturi’s comments about Vegas, one of the biggest revolutions of the postmodern period has become a part of popular culture with large-scale ornamentations and graphics in the form of billboards and the designs of boulevards, buildings, and spaces [34].

Architectural companies that design contemporary hotels, such as Bjarke Ingels Group, have used ornamentation with the influence of postmodernism in their designs. The mostly visual ornamentation in the projects represents a superficial flood of images in the production of contemporary society. Since the facade decorations of the Arlanda hotel (depictions of Swedish royal figures) have an important role in urban portraits and revive history in the memories, a mission has been taken [35]. Transferring ostentation and exaggeration into the design creates the feeling that users are in a completely different world in the places they are in. For this purpose, a kitsch style was created that postmodernized ‘cultural tourism’ and transformed it into a ‘lifestyle’ hotel. This style, which is also defined as ‘Faux Architecture’ in the literature, was generally implemented with a general perspective on ‘what the old decoration looked like’ by thoughtlessly combining historical elements and details. Kitsch, interpreted as ‘misfortune’, is interpreted as causing the symbolic meanings created by ornamentation to lose value and become cheap [36].

Hotel interiors are places where the user can define the identity of the place and at the same time create a theme or concept experience that can remain in their memories of the hotel. It is very important to include architectural narratives in the design and for the designer to see the project like a movie scene for the development of contemporary hotel interior design. This is understood from Jean Nouvel’s design of ‘The Hotel’ in Louzen [37]. Five-star hotels in Northern Cyprus, which look like ships, temples, palaces, skyscrapers, mansions, castles, and chateaus, have been designed and put into service with this thematic perspective.

It has been seen in this study that, although ornamentation is mentioned in studies on hotel designs in the literature, there are very few studies directly related to contemporary hotel interior ornamentation. The analyses focused on the buildings’ general character and the findings remained mostly on an architectural scale. Ornamentation is mostly seen on facades and traditional applications. In the research, casino hotel buildings in Northern Cyprus are classified and listed according to their chronological and characteristic features, and structural appearance [5].

3. Conceptual Framework of Ornamentation

Ornamentation, which has been discussed since the time of Vitruvius, has been used as an architectural tool that represents people’s belonging to the region, their lifestyles, social status, traditional cultures, the character structure of the applied region, and the innovative values in the process over the ages. It has been clearly seen in the research that ornamentation has maintained its traditional vision in the application styles of contemporary period conditions, has adapted to the present day, and has taken its place in architecture in a mixed style with the synthesis of the old and the new.

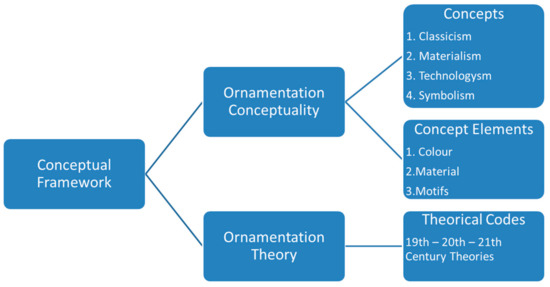

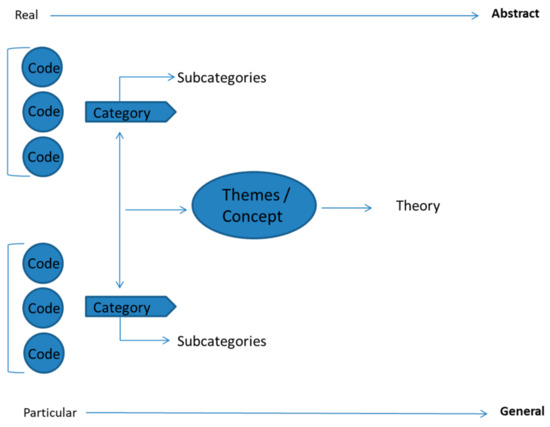

The design, concepts, and all factors related to design applied in this representation process were studied in the light of chronological, sociological, and anthropological data in the literature study. As shown in Figure 1, with the conceptual framework produced, ornamentation has been classified both theoretically and practically together with the infrastructure of today’s applications. In this context, contemporary-period decoration has been diversified in terms of ‘concepts’ such as classicism, materialism, technologism, and symbolism. In addition, the colors, materials, and motifs used in ornamentation are described as ‘concept elements’. In the study, the concepts are explained mostly in terms of the constructed buildings and the perspectives of the architects. The coding studies in ornament theory can be seen in Table 1 in the previous section.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework process studied by Author.

Table 1.

Ornamentation coding study.

3.1. Classicism

A group of architects who opposed the ideas of modernism and international styles were inspired by the 18th century, the Renaissance, and even Roman Architecture, adding a new interpretation to the classical style. It is believed that classicism comprises a wealth of architectural knowledge that carries many civilian values and is freely adaptable. This has been under the influence of a revolution in interior architecture after a period in which the ornament was almost ignored [38].

Charles Siegel described in his book, ‘An Architecture for Our Time, The New Classicism’, a new classical style with some present factors in the formation of this style. In the study, which indicates differentiation from old neoclassic styles through factors such as simplicity, decentralization, human scale, historical continuity, local styles, and culture over technology, it is explained that classicism shows differences according to the regions and thus shows variability with its decorations [39].

The existence of a developing global economy in the world, especially with the influence of the modernism project that developed at the beginning of the 20th century, has provided an opportunity for the new generation of postmodern architects who want to express identity and cultural emphasis in design to try the classical style again.

In fact, there has been a sense of belonging to both newly established countries and cities in the reform process since classical history. While many societies were creating their modern/new images, they turned their faces to the West, and Westernism turned into an ideal role model for the developing new world conditions.

New classicism, adapted from the heritage of Ancient Roman and Greek architecture, features exaggerated scale, a symmetrical plan type, magnificent Doric/Iconic columns, domed roofs with flat ceilings, designs with more basic forms, and simple decoration. In some academic works, it has been seen that neoclassicism has been diversified into Strict–Classical–Minimal Classicism types. Figurative, abstract, and late modern iconic ornamental elements on buildings helped in the classification process [4].

Robert Stern, who defines ornament as ‘the Handmaiden of Historical Allusion’, listed the desires of postmodernism with the principles of contextualism, allusion, and ornamentation. Stern believes that ornamentation does not necessarily have to reference history or culture, particularly on vertical surfaces. He argues that decoration should reach people with ‘elaborations’ coming from their own nature and ‘buildings articulation’ on a human scale [40].

New Classicism was studied in the Northern Cyprus region in the article titled ‘The New Architectural Classicism In Northern Cyprus’. This movement is classified from the works of Robert Stern, and Andreas Papadakis and Harriet Watson. These are classified as (1) Figurative, (2) Abstract, (3) Postmodern/Free Style, and (4) Ironic/Kitch Classicism. Although the common point in these variations is the classical style, the differences are clearly seen in the decorations of the space. Thus, the narrative, mission, and function of ornament are also understood through classicism [41].

3.2. Materialism

Accompanied by the development of the industrial revolution in contemporary architecture, the production of new building materials, structural elements, and other products in the construction business has been achieved cheaper and faster. The modern lifestyle, capitalist conditions, and new urbanism concepts in society have left behind the choice of traditional materials and have created perspectives that introduce new more attractive materials. Materials such as iron, steel, zinc, glass, and so on are more common in architecture, especially in northern countries. These have improved the constructivist style and have become indispensable for contemporary material structures.

Undoubtedly, this change in the art of architecture with modernism has also influenced the ornamentation in buildings. The concept of decoration has been a priority for both the designer and the user in architecture throughout the entire architectural process. In a study in 1910, Adolf Loos argued that the ornamental elements used in the traditional style should not be in modern architecture, saying that it was a crime to embellish, thus approaching the 20th century in a completely different way. In rejecting periodical adornments and figurative approaches, Loos used materialism as an ability to compensate for these losses. He saw the material as an element expressing culture and architecture instead of ordinary use, and applied it to his designs [42].

Looking at the interior of Loos’ house, it can be observed that although the architect refused to ornament, the natural pattern in the material in the space is at the forefront, and ornamentation work has been performed in a functional context. The irony in Loos’s choice of exaggerated and expensive materials in the space, arguing that ornamentation is a costly and time-consuming practice, is thought-provoking. Loos argued that in the style of Mies Van Der Rohe, there should not be a lot of leftovers or superficial and unnecessary details in the design, and rich materials and forms should be applied instead of detailed ornamentation. Mies, who described his buildings as ‘skin and bones’ architecture, also glorified the main rational form of the building and the details of the materials used with the idea of ‘God is in the details’, which he had already stated, and argued that there is no need for any other ornamentation [43]. The Barcelona Pavilion is one of the best buildings in Mies’ design of materialistic transmission.

According to Wright, the material will reveal its own form, proportion, and ornament [44]. In his own architectural style and the ‘organic architecture’ that is the principle in his designs, he attempts to understand the natural structure of the material and stick to that. Defending the idea that the most beautiful material is a material from nature, Wright argued that he used nature as his best source for ‘aesthetics in architecture’. Hence, the materialist approach formed by the concepts of nature and organic beauty of the period promoted by the modernist project was accepted.

Modernist architectural ideals, which designers have aimed to achieve since the Industrial Revolution, take place in the minds of architects with this approach. The sovereignty of technology has created an abstract architecture that can be achieved through the use of plain geometry and has been implemented in architecture with a rational and purist approach in the sense of simplicity and functionality [45]. The visual presentation obtained through the use of materials in spaces inevitably achieves the ornamentation process in the space through the beauty of the material.

3.3. Technologism

The beginning of the importance of mechanization and the positivist flow toward the end of the 18th century emphasized the necessity of a search for various areas of life and began to validate the sovereignty of technological thought. While technology represented an approach to artistic production, architecture was perceived as a formative capacity for various materials, limited by scale and detail [46]. In architecture, the period in which technology was at the forefront of the conceptual dimension can be examined from two separate historical perspectives. The first of these is based on the 19th-century Industrial Revolution and the second is the ‘High-Tech’ approach, i.e., the postmodern and de-constructive style and the ongoing period of the early 1970s [47].

As a result of the Industrial Revolution, the emerging structure of manufacturing technology and the utopian approaches of designers have become the most important elements in the name of aesthetics in construction. Accordingly, ornaments are transferred with this design approach applied. This approach, in particular for the Italian futurists and the Russian constructivists, has been a worldwide example in buildings such as the Eiffel Tower in Paris (1889) and Crystal Palace in England (1851).

Every building designed by ‘Team 4’ (N. Foster, R. Rogers, N. Grimshaw, and M. Hopkins) between 1967 and 1987 was called ‘High-Tech’, when postmodernism had started and de-constructivism had ended. The main characteristics of this architectural approach are as follows: typical materials are metal and glass; openness in expression; industrial production ideas; to benefit from different industries from the image and technology building industry; and priority is given to flexibility in use. In 1970, R. Rogers started to work with R. Piano, building the Center Pompidou, a cultural and arts center that would be completed in 1977. He had won a contest in Paris in 1971, and the new building made High-Tech a focal point. The Pompidou Building has a completely flexible plan and represents a ‘victory for cell’ and ‘machine technology’ [47]. In this respect, ornamentation was this technology itself in a conceptual context.

In the new architecture of the 21st century, new production standards and concepts formed due to the development of technology have created a new paradigm. The new architecture in this paradigm based on tectonic and constructive principles has now become a more digital architecture, a more abstract design approach than the 20th-century avant-garde approaches. Drafting has provided a different conceptual direction by enabling preparation of the materials used in ornamentation, digital techniques, and computer-based programs [48].

Technology, which has helped to transfer architecture to the concept, to transfer expression to the concept, and to complete unfinished work has its best example in the contemporary architecture by the famous French architect Jean Nouvel [8]. Postmodern architect Frank Gehry’s buildings, with an extraordinary design story, are one of the examples of how complex architectural forms can be solved with the help of a computer. Although digital manufacturing methods lack the physical properties of natural materials, and even though the first models are physically made, they have a great respect for the formal complexity of the forms. Materials imbued with digital methods have great significance for the formal complexity of the structure, as if it had a meaning like a traditional material. With the aid of digital technology in the production of the Bilbao Guggenheim Museum, surfaces have been created at very different angles in the structure, and geometrical transfer of three-dimensional objects has become feasible [49]. Frank Gehry’s metallic floral building has become one of the best examples of a new understanding emerging from the combination of organic architecture and high-tech architecture.

Charles Jencks defines contemporary ornament as ‘the cultural expression of selected patterns’. While describing the patterns as the motif of the house, Jencks explains that the shapes and forms of different geometries created by the universe can be formed with the help of computers in contemporary decoration. In his studies on the new complexity paradigm, Jencks wrote that the new architecture was ‘produced by combining ornamental patterns with computer generation’ [50]. The traditional ethnic Arab motifs and ornaments used by the Institute du Monde Arab in 1987, the Doha Tower in Qatar in 2012, and the Louvre in Abu Dhabi in 2017 can be counted as the best examples of representations of ornamentation in terms of architectural symbolic values. The diversity of industrial building materials produced by technology, and the ornamentation of materials used in building facades, show not only the interior but also the urban scale [8]. Jean Nouvel’s constructions have created a landmark mission in the cities they are in and proved the value of ornament.

3.4. Symbolism

Ornaments, which were considered the ‘most conspicuous form of representation’ until the first half of the 19th century, were cataloged in critical analyses of architecture under the name of ornamental ‘sign’. However, later documentation of the representational development of ornaments in architecture has caused serious controversy regarding the historical origin of ornaments. This brought about a paradigm shift in the 20th century that caused the perception of morphologically dividing architecture into two, analogically and symbolically [51].

The new concept in the architecture following the Industrial Revolution that started in the second half of the 19th century supported pure forms. The ‘basic forms’ and ‘basic colors’ supported by modernism and Bauhaus are also seen in architecture as a symbol in the architectural movement, which does not support symbolism. Le Corbusier’s analogy with the machine for life [46] is a remodeling of the symbolic context of architecture with its ‘international style’, a minimal ornamentation principle common to both the interior and the exterior of the building, which has spread widely with the principle of applicability. The glass house, designed by Philip Johnson in 1949, is an important example with its symbolic value for its era, rational form, transparent façade, and limited furniture, to convey its presence in nature to the minimal level, of course with a different approach than Mies’.

The alleged failure of modernism, then, became a stepping stone to the reconstruction of the cultural symbolism that transformed postmodernism, and this represented a whole new process in architecture [52]. Venturi has applied modernity only in modern building techniques, has taken reference from elements of history in his constructions, and has entered into a new regional architecture that uses symbolic imagery. Ornamentation is a free architectural element that comes from the region itself; it can be a traditional reflection of culture and civilization and is not mistaken for the right side of this new style. Some have defined this as postmodernism and it is also called traditional Western architecture [13]. Venturi House, which Venturi built for his mother and which has a natural appearance as a retrospective in interior design, is described in the literature as a one-part summary of the design story of Venturi’s design vision. Neo-eclectic postmodern architectural ornamentation is seen as a historical reference; color and symbols are used in the interior and exterior. Venturi, while stating that buildings in modernism-unsigned (no-ornament) architecture are actually considered symbols, also said that postmodernism has added wit, ornamentation, and reference to symbolist architecture and defended modernism with an opposite attitude.

After postmodernism, the de-constructivist movement began, which is opposed to the historicism of postmodern architecture and the ideology of modernism, but it is still a correct example of modernism as its reference and differentiation. In this style, constructions must have their own unique identity, a technological and foldable architectural style, so that they can go to the most extreme points a design can reach. The goal in the design of structures that can be produced with higher freedom has been to produce a symbolic mission for the building with the materials to be selected, in addition to creating the desired form of the structure. While the London City Hall building symbolizes modernism with its transparent material on its outer walls, the building has become a symbol of democracy in the region, with the influence of the idea of building a universal iconic form and universal pattern for the iconic image [53].

4. Materials and Methods

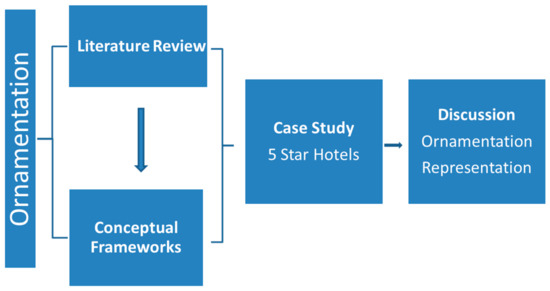

This study, in which a qualitative research method was applied, deals with the interpretation of ornamentation in today’s theoretical context and the determination of the relationships between space and ornamentation. In this context, theoretical research and a case study were carried out as a foundation. For this reason, the study was performed in three phases. The diagram showing the process of the method appears in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Ornamentation analyses process study.

4.1. ‘Creating a Theoretical Basis by Narratives’

The first stage of the study carried out for this purpose was to research and read all the necessary sources in the academic literature in order to understand and interpret the ornamentation in contemporary architecture. The literature review later provided reference support for the information required for the ‘Conceptual Framework’ study (Figure 1). Being able to understand both the theoretical and conceptual changes that ornamentation has undergone within the modern period by studying it through the literature has contributed to the identification of the physical structure and semantic mission of the ornament [12].

While conceptual diversity in ornamentation was discussed within the scope of the study, the elements in the concepts used were created based on the generalization of visual and written literature information. In addition to this process, one of the most important parts of the study was the coding method prepared from studies on ornamentation.

While the source references were selected in the literature study, studies that explained ornamentation in different aspects in a semantic context and included the philosophy of showing the study narrative were selected. All definitions, analogies, examples, explanations, and metaphors used regarding the ornamentation written in the narratives were converted into words and codes. These words were clustered according to their semantic similarities and a coding table was created as a result [54]. Figure 3 shows the transition model from streamlined codes to theory for qualitative research, a study by Saldana.

Figure 3.

A streamlined codes-to-theory model for qualitative inquiry by Saldana, 2016 [54].

Within the framework of the theoretical study, a conceptual framework for ornamentation was developed using the chronological coding method shown in Table 1 to sum up all the theories. In this context, as a result of the different perspectives that have existed since the time of Vitruvius, some common concepts and their starting points can be accepted. When looking at these concepts, the first thing that stands out is that in the process of the developing contemporary world, the concept of ‘new’ has been accepted in every sense and transferred to architecture. In the postmodern world, the value given to humans is shown from a different vision. This is shown with the background of historical references that concepts such as the importance of regionalism today, the transfer of culture and identity to the structure and its sustainability, and adding taste and style to architecture are unchangeable cyclical phenomena that have been going on for centuries. Just as thoughts are conveyed through written literature using words, they also influence practices related to literature. It is important not only to be a thinker but also to be a practitioner and even a user.

This section aims to provide guidance on how we should interpret a practice with a profound philosophical background, such as architecture. It summarizes the works of contemporary architectural theorists from the 19th to the 21st century in a lexical context and codes their thoughts for the study of space and common language analysis. In this way, visual applications and intellectual theories can be combined and discussed.

Using this method, the common points in hundreds of comments made on the subject can be determined, and abstract concepts can be expressed more clearly. The coding study was transferred to the table on a time basis, starting from the nineteenth century until this stage of the twenty-first century (Table 1). This charting then served as a vital basis for the case study and discussion processes that took place in subsequent stages.

4.2. ‘Evaluating Ornamentation in Case Study’

The study was mainly carried out with respect to five-star casino hotels in Northern Cyprus, which generate great economic income and have strongly applied ornamentation in their designs. Since ornamentation is an important element of the spatial story that is intended to be told to hotel users [33], it was important for us to analyze these spaces. For this reason, a study was carried out according to the current island-wide five-star hotel list obtained by the ‘Northern Cyprus Tourism Planning Department’ [55]. This study was carried out mostly using observational and photographic methods. During the observations, all elements that served as ornamentation in the spaces were analyzed. Many details such as directly or indirectly ornamented surfaces, ornamentation methods, two- or three-dimensional shapes used, the relationships between the decorated elements among themselves and with the space, the materials used, colors, ornamentation styles, and concepts were identified and documented.

The analysis phase lasted for six months to determine the differences in space usage in the high season and low season, which are important for the tourism sector. The information and criteria from the theoretical study acquired in the first phase served as a guide in the spatial analysis. All the resulting data were transferred to a table and collected in a single format (Table 2). Hotels were listed with their concept and conceptual element information, with visuals added. The paintings enabled us to interpret the ornamentation from a broader perspective with the ‘logic of looking at the whole picture’ and prepared the work to move on to its third phase.

Table 2.

Hotel ornamentation analysis table.

4.3. ‘Discussion Considering All the Data’

The main principle in carrying out this phase was to collect and interpret the results obtained in the first and second phases in a single pool. In particular, the words obtained through coding methods were combined with the data in today’s applications, and a conceptual conclusion was reached. While carrying out this process, long-term experiences in the hotel locations, the current history of Cyprus, its political, economic, and socio-cultural situation, and comprehensive reference sources in the literature formed the background.

5. Results

In this part of the study, in the prepared ornament table, the analyses of the entrance sections of five-star casino hotels in Northern Cyprus were listed in alphabetical order, and the ornamentation in the spaces was studied in both physical and conceptual contexts. The study, conducted on a total of twenty-three hotels, was developed according to the results obtained by calculating the common denominator of the data in an analytical manner.

As a result of the research carried out within the scope of the case study, the decorations in the hotel entrance–reception–lobby sections were analyzed in detail. In the observation and detection study, the hotel’s general ornamentation concept and concept elements were examined. The data obtained from the analysis allowed the following discussions to be undertaken.

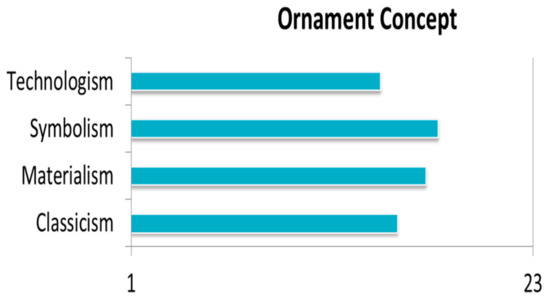

5.1. Concepts

As shown in the Figure 4, the ornaments were viewed in terms of the concepts of symbolism, classicism, materialism, and technologism. It has been seen in hotels designed with many different thematic approaches that ‘symbolic’ approaches are mostly applied in the design of five-star casino hotels. Mythological characters and exaggerated postmodern elements in the designs have created a very rich database in terms of ornamentation and played the role of an inviting representative for the entertainment industry in tourism.

Figure 4.

Ornamentation concept chart.

In addition, as a result of the case study, the island’s ‘Ottoman Empire’ history has been a great source of inspiration for hotel interiors. Accordingly, it has been determined that the designs of postmodern hotel buildings in Northern Cyprus are more Ottoman architecture and Western classical architecture than the vernacular architectural style [38].

In this approach, both the representation of regional identity and the fact that it is very close to the users’ culture, most of whom come from Turkey and the Middle East, have made the design advantageous. Conversely, this style can be described as remarkable and more exotic for tourists coming from different locations. The material has become very important for ornamentation, both with the conceptual approach it brings and its role in other concepts. This is not only true for most modernist hotels that reject the traditional style, but also for casino hotels that have a story in their design and do not shy away from lavish displays of wealth and luxury to show off to their guests. The feeling of rarity and uniqueness of the materials imported from abroad has become more remarkable for the users.

The most important architectural changes in the 21st century have undoubtedly occurred thanks to the development of technology. In parallel with these, the design approach in Northern Cyprus hotel architecture has been open to unimaginable decorations, especially when it comes to casino culture.

Technology has managed to excite users with opportunities such as the multi-dimensional surface works it adds to the design, its challenges in structure, the formal freedoms in the materials used, and the luxury of alternative diversity. In the analysis, it was also seen that the decoration of the space had the effect of technology adding to the space in this way. With the competitive side of tourism, there is an indispensable need to bring buildings up to world standards.

5.2. Concept Elements

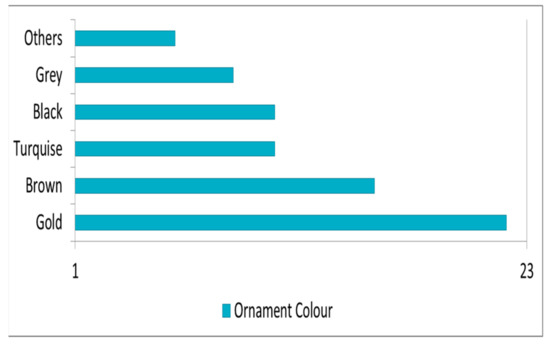

- Color:

When looking at the cases in terms of color usage, the first observation is the ‘indispensability of the gold color’. As seen in Figure 5, gold has become the most dominant color choice in almost all hotels. The color gold, which has been an indicator of power and wealth since ancient times, is a dominant element in the decoration of almost all spaces and serves as a complement to other colors. Especially in the classical style, ‘brown’ color decorations on a cream background color are frequently seen both on the floor and on the furniture.

Figure 5.

Ornamentation color chart.

Black and gray colors were mostly seen in hotels that approach the design as more contemporary and abstract, in contrast to the traditional style. For this reason, it was determined that gold is used less than other colors. Black and gray were mostly used with light colors due to the contrasting effect they create. Natural marble and polished wood were found in furniture and coverings.

Apart from the colors written above, the limited use of colors in spaces is seriously striking. The fact that hundreds of shades of colors in the color palette are not evident in most decorations is both disappointing and thought-provoking. It has been observed that colors are generally used in textile products in a single tone with a smooth transition. This approach, which prevents color confusion, creates the feeling of an effort to modernize even the most classical applications. Contrary to all these observations, it has been observed that the most popular dynamic color used in decorations is turquoise. As the name suggests, it seems logical that this color was chosen with the influence of cultural ties.

- Material:

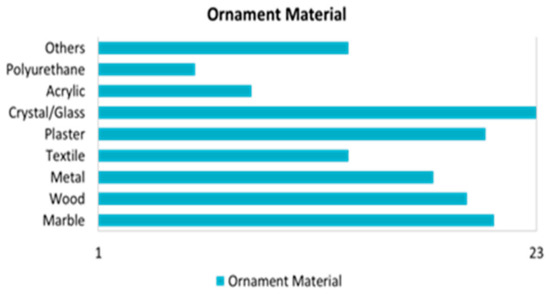

During this research, a wide variety of materials were encountered in hotels where millions of dollars were invested. The subject was not only the materials in the space but also the meaning of the materials, and especially their mission in terms of decoration. The first point analyzed in the study is the determination that despite the advanced changes in time and technology, the most popular materials used in spaces are still traditional materials. It is clearly seen that as the modernity of the material increases, its presence in the usage diagram decreases. General comments about the materials used are as follows.

As shown in the Figure 6, it was observed that crystal/glass chandeliers are an important welcoming element in all hotels, from the most classical to the most minimal. Crystals, with their inherent shine and reflection properties, have become the most characteristic element of the entrance section, even in a large-scale design.

Figure 6.

Ornamentation material chart.

Wood is used in details such as jambs, foils, furniture coverings, and wall reliefs. While its presence increased in the classical style in the space, its use decreased in more contemporary approaches. It is still considered one of the most preferred materials in today’s spaces, especially due to its cutting into the desired shape with CNC machines and new types of wood polishes and paints.

Metal materials such as iron, copper, brass, and steel have added tremendous elegance and ostentation to hotel designs. Gold, which is especially an indicator of wealth, has been applied to various materials in different shapes and sizes, and over time, it has become a more permanent and bright solution against the possibility of fading in the area where foil paint is applied.

One of the most striking findings in this study is the simplicity of the textile choices used in the spaces. While textiles were especially seen in furniture upholstery and curtains, the simple approach applied served as a balancing element to the general decorations applied in other elements of the space. Contrary to previous periods, ornamentation is not seen as competing with different elements, rather it is now seen as being more interconnected between surfaces.

It appears that marble is indispensable. It was used primarily as a floor covering material in all but a few hotels and was decorated with different colors and different motifs when applied. In addition, it was observed on the table tops of furniture such as, reception desks, middle/side tables, nesting tables, consoles, and dressers, and also wall coverings. Its usage area changed depending on the homogeneity of its structure. While smoother, less patterned, and veined marble models were preferred on floors, marbles with mixed patterns were mostly used in furniture. It has also inspired the use of quartz and onyx materials in some hotels.

Wooden ceilings and wall ornamentations of the past have been replaced by plasterboard due to the advantage of it being easier, cheaper, and faster to use. Plasterboard material can take the desired shape due to its flexibility; thus, it can adapt to all kinds of styles. It is one of the most popular materials used in contemporary architecture, especially with new lighting systems and colorings.

Acrylic material is used in many different forms and in many different areas. Its initial state, the liquid form, is molded into the desired form and takes its place in the space with different functions. Our research found that this material was seen in column decorations, floor coverings with its sister material epoxy, stair railings, and furniture.

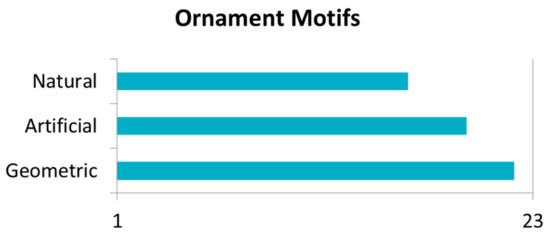

- Motif types:

In the space ornamentation motif typology study, which was guided by Mayer’s publication [2], it was seen that mostly geometric motifs were used in hotels. Appearing in both classical and modern styles, ‘geometric’ motifs have been applied in basic shapes; straight, diagonal, and organic lines; and in traditional cultural motif applications. This type of motif is especially seen in spaces with Islamic figures inspired by the Ottoman style. The second type of motif was the ‘artificial’ type. These motifs were applied in various styles in the characters produced from mythological themes, contemporary art products, inscriptions, abstract figures, and similar works in the hotels examined. Finally, ‘natural’ motifs, which we found were applied the least today, although they were the most popular motif type of the past period, are now mostly seen in plant figures. Three-dimensional transfers seen in geometric shapes are mostly applied in two dimensions and mostly in textiles. In addition, while the motifs were mostly seen on marble floors, they later also appeared in wallpapers, wood carvings, suspended ceiling decorations, and textiles. Figure 7 statistically shows the motif type usage rates in the case study.

Figure 7.

Ornamentation motif chart.

6. Discussion

Within the scope of this research, various definitions of ornaments are found in the literature, influenced by factors such as time, region, politics, economy, culture, and history. These interpretations, whether direct or indirect, can be challenging to comprehend and may lead to confusion. It is crucial to extract the correct insights from these explanations and classifications, especially when evaluating abstract concepts in architecture.

Interpreting space according to contemporary definitions, particularly in the analysis of contemporary decoration, presents a significant challenge. Additionally, the lack of exemplary works on contemporary interior decoration in Northern Cyprus necessitates its development from scratch within the methodology of this study. Furthermore, due to the coinciding pandemic, the closure of hotels in Northern Cyprus delayed the analysis process, as these establishments’ reopening and occupancy rates were uncertain.

The study’s findings suggest that the decoration was integrated into the space both contextually and conceptually. The relationship between ornament and perceiver, its design philosophy, mission, and the effects it generates fall under the contextual category. Similarly, application styles, sensory transfers, design language, and character have been interpreted as part of the conceptual categories.

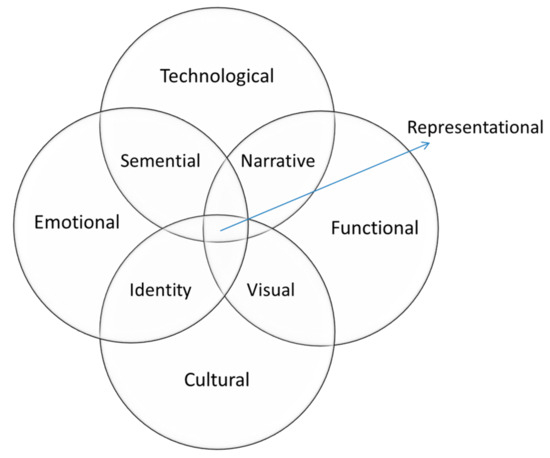

6.1. Contextual

When 21st-century Northern Cyprus hotel interior ornamentation is read within the framework of the same generation of theories, it is seen that some common topics emerge in the context of the meaning and mission of ornamentation. These themes lead us to question why the ornamentation was undertaken in that way. As shown in Figure 8, when the visuals and theories in the working process come together, the cultural, functional, technological, and emotional infrastructures of ornamentation are observed. Additionally, it is believed that the intersections arising from the relationships between these infrastructures give rise to semantic, narrative, visual, and identity approaches. The fact that the representative approach in decoration is the midpoint in all these concepts supports the main objective of this study.

Figure 8.

Relational diagram of ornamentation factors and concept.

6.1.1. Culture and Identity

In the observations made within the scope of the case study, one of the most striking features was the ostentation and exaggeration approach used in hotels. The interiors of the buildings, many of which are designed in a postmodern style, bear resemblance to the architectural style of the buildings. As Kiessel et al. mentioned, the architectural styles of all the tourism buildings introduced ‘Ironic/Kitsch Classicism’ [41]. The kitsch-inspired style of the casino areas is formed mostly by the combination of classical eclectic elements.

While the ‘Social Status Indicator’ theory mentioned in Balık’s [21] work sometimes allows users to understand the glorious history of the past and feel part of it. The casino culture in Northern Cyprus operates with show-business logic, just like in the Las Vegas story [34]. Hotels are responsible for having all the infrastructures and sensory presentations needed by this entertainment sector. This service must be constantly updated with changes in popular culture and always maintain the highest standard of customer satisfaction. With the ‘symbolic ornament’ gamble, objects and visuals are given meaning, and the story they carry helps the thematic style used in hotels. Squarez [29] also mentioned ‘Ideantal Representation’ in his study and commented that the decorations used in design can represent thoughts and many different ideas. The lions of Cratos Hotel, the parametric decorations of Eleksus Hotel, the rich variety of materials used by Merit Hotel, and hundreds of similar details all give the same message as if they support the theory of ‘Identical Figures Represent’. For them, ornamentation is a symbol of power and wealth that they use to influence their users. Pushing the boundaries of the concept of luxury and reflecting it to hotel guests and increasing their satisfaction has become an important marketing strategy, especially for casino customers. In addition to these theories, when looking at Lynn’s ‘Regional Culture’ idea [12], no reference to the region was found in the ornamentation of any of the hotels evaluated.

6.1.2. Technological

From the point of view that ornamentation is defined as ‘Means of Meaning’ by Squarez [29], technology has occupied a very important place in theoretical terms with respect to the method of applying meanings. Almost all writers have interpreted ornamentation in terms of the developments that occur under the influence of today’s digital world. When we interpreted Balık’s ‘Digital Manufacturers’ idea [21] in the ornamentation of Northern Cyprus hotels, it was observed that there was no direct use other than the LED screen panels used in The Arkın İskele Hotel. It has been determined that mobile/smart technologies, which we can define as ‘dynamic ornaments’, are not preferred in projects built with huge budgets. Massey’s ‘Advancing Technology’ discourse [12] can be seen in the large-scale roof structures of the buildings, the variety of materials that can be produced in various lengths and dimensions, and finally the facade cladding with thematic figures and lighting systems.

6.1.3. Functional

In line with technological advancements, the notion of enhancing the functional capacity of ornamentation has become integrated into the architectural perspective of the new generation. While in the past, two-dimensional ornaments were solely applied to surfaces, today we observe that they can also manifest as monumental forms of the building itself. In this context, scholars such as Opincariu, Massey [22], and Gleiter [21] have discussed the functional role of ornamentation in their works.

The analyses conducted in hotels indicate that the ornamentation used in interiors not only functions as a decorative element but serves as an impressive (discussed under ‘emotional’) and symbolizing (discussed under ‘culture and identity’) tool.

6.1.4. Visual

In the hotel analysis study, it was clearly understood that visuality was one of the most important starting points for the use of meaningful or meaningless ornamentation. The ‘Visual Perception Equipment’ that Picon [27] stated in his article is a definition made exactly for decoration. These perception methods explain the importance and mission of ornamentation in different types of designs, as Gleiter [21] mentioned in his ‘Style and Taste’ comment. While the decoration created by the floor covering creates an Op-Art effect thanks to the application techniques in the Grand Pasha Nicosia Hotel, the traditional marble floor coverings of the Kaya Palazzo Hotel can make users experience the style of today’s Renaissance building. Massey [22] explained the freedom in design with the words ‘Free Surface’, within all the possibilities we have in the contemporary period we live in, and it has been analyzed that this logic encourages the interior design process of most hotels. As if supporting this idea, ‘Distinctive Figure’ describes the importance of the unique belonging of the ornamentation, even in ornaments that can be applied as desired. The approaches for aesthetics in ornamentation have become a common indispensable part of all the hotels on the list.

6.1.5. Emotional

The purpose of all decorations is to provide immediate excitement to the user, evoking adoration for the place and even fostering a bond between the place and the person. All of this depends on understanding people well and being able to give the right answer to their expectations. What Venturi [13] wanted to describe as a ‘Story Teller’ in the twentieth century related to describing the place as a story space and giving the excitement and happiness of fairy tales to the listeners. Stories in Northern Cyprus hotels vary depending on the region. In Iskele-Bafra hotels, which have magnificent beach potential, there are thematic hotels that have completed their designs with entertainment, such as the Temple of Artemis, Noah’s Ark, and Concorde. The hotels in the region, particularly those focused only on casinos, have a ‘prestige’ mission in decoration, as Balık mentioned. The craziness of surface decorations at casino entrances makes users feel like they are in another world and at a different time. The excitement intended to be given to the user of the space will later result in positive feedback to the operator, and the ornamentation will also serve as a marketing strategy. While ornamentation can be defined as an element that both directs and is guided by emotions, the ‘Emotional Quality’ mentioned by Picon [27] supports these thoughts.

6.1.6. Semantical and Narrative

The authors, architects, and theorists considered within the scope of the literature review consistently attempted to explain decoration through storytelling while defining it. Studies were at times conducted using rational logic and at other times through the use of analogies and metaphors. The primary objective was to cultivate inspiration that delves into the depths of ornamentation, approach it philosophically when necessary, and convey ornamentation to our lives and designs in the most precise manner. As a result, it is apparent that all the factors and concepts identified were established through narratives and meanings. Figure 7 illustrates how flexible and variable these factors can indeed be in a conceptual context, serving as an intersection between various elements.

6.2. Conceptual

6.2.1. Concept

Based on Figure 3 and the case study, it was determined that symbolism emerged as the most prevalent concept type in hotels. This observation suggests that the effects of postmodernism, a period when symbolism was particularly prominent in contemporary architecture [53], continue to influence hotel spaces in Northern Cyprus today. This implies that the decorations used in these spaces serve as storytellers of cultural narratives. Concepts featuring historical or mythological figures have contributed to establishing an emotional connection with the users.

6.2.2. Concept Elements

The observations indicate that five-star hotel establishments in Northern Cyprus have opted for classical elegance in their designs to offer an exclusive service to their customers. Crystal chandeliers and large-surface natural marble (seen in Figure 6, prominently featured in hotel entrance designs, convey a narrative of elegance and opulence. Complementing these materials, ‘gold’ (depicted in Figure 5 emerges as the most popular color in decoration, symbolizing a sense of privilege and high status for the users. The concept of ‘gold’, an important marketing strategy, exerts a similar symbolic influence on the atmosphere of the place [56].

Furthermore, upon examining motifs, described as the smallest unit of decoration utilizing unlimited colors in various materials [9], geometric-type applications are found to be most prevalent (Figure 7. Motifs, allowing direct figurative expression of culture and identity on the surfaces they adorn, have remained a crucial element of conceptual expression in design since ancient times. The simple geometric shapes within the motifs visually appeal to diverse user profiles in the hotel building designs that bring together multicultural audiences.

In conclusion, each element integrated into design concepts serves as a representative of the main theme in an intellectual context and across different fields.

7. Conclusions

In the context of this study, ornamentation has been re-evaluated in the realm of contemporary popular culture, particularly within the innovative environments reflective of the eclectic approaches of the postmodern era. Notably, it has been discerned that the utilization of ornamentation in present-day hotel architecture in Northern Cyprus is aligned with contemporary ornamentation theories. Moreover, with the influence of avant-garde approaches, it has been re-conceptualized through the specific case of Northern Cyprus, showcasing that ornamentation can be successfully featured in spectacular buildings despite economic or political challenges present in any given region.

Despite its centuries-old existence, the art of ornamentation has become ubiquitous worldwide due to globalization, notably impacting 21st-century architecture, among numerous other fields. Despite globalization, the transfer of cultural heritage values through the use of ornamentation serves a similar purpose as the storytelling mission intended for spatial design. Consequently, one can readily designate ornamentation as ‘culturally representative’. Examining the multicultural aspects of Northern Cyprus, it becomes evident how vital ornamentation is for architecture spanning past and future generations. It stands as an indispensable artistic application that can tangibly embody the fundamental principles of entertainment and beauty inherent in tourism structures, effectively manifesting these concepts within the physical space.

This significance has been empirically proven by examples in Northern Cyprus, as well as instances worldwide, underscoring the paramount role of ornamentation within design parameters. Consequently, this study reaffirms the enduring importance of ornamentation in shaping interior architecture.

We have devised a method that allows for the examination of how ornamentation in Northern Cyprus is perceived from a theoretical standpoint, and then how it is interpreted in a conceptual context. The framework of this method paves the way for the analysis of ornamentation in various types of buildings or decorations within tourism establishments across different regions in the future.

For some, ornamentation serves as a means to comprehend architecture; for others, it embodies the integration of nature within a space; for another group, it represents a marker of identity; and for yet another, it is an undesirable feature that should be avoided. Despite these varied perspectives, one common thread remains: ornamentation serves as a medium for the expression of diverse thoughts. Consequently, the next question arises: What is the role of this expressive medium in the design of hotels in Northern Cyprus? The answers are unequivocal: To enrich the entertainment industry, to enhance the narrative the venue aims to convey by visually articulating it, and to accomplish this within the framework of the venue’s unique design concept.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A. and H.G.; methodology, H.A.; software, H.A.; validation, H.A. and H.G.; formal analysis, H.A.; investigation, H.A.; resources, H.A.; data curation, H.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.; writing—review and editing, H.G.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jones, O. The Grammar of Ornament by Owen Jones, 1st ed.; Day and Son: London, UK, 1868; pp. 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- TRNC Prime Ministry; Cyprus Turkish Investment Development Agency. TRNC Economy, Investment Areas and Incentives. 2020. Available online: https://investnorthcyprus.gov.ct.tr/Portals/5/North%20Cyprus-%20General%20Economic%20Data.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Bozdağlar, H.; Emeahwali, O.L. The Economic Impact of International Tourists on the TRNC Economy. ARP Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Balık, D.; Allmer, A. A big yes to superficiality: Arlanda Hotel by Bjarke Ingels Group. METU J. 2015, 32, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yücel-Besim, D.Y.; Kiessel, M.; Kiessel, A.T. Postmodernist Hotel-Casino Complexes in Northern Cyprus. METU J. Fac. Arch. 2010, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öngün, Z. Ornamentations in Interior Spaces (Case Study: Old Houses in Nicosia). Master’s Thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Architecture Faculty, Famagusta, Turkey, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Çakmak, A.C. Ornamentation in Traditional Cyprus Houses; Scholars’ Press: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrache, A. Ornamental art and architectural decoration. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 51, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S. A Handbook of Ornament, 1st ed.; Architectural Book Publishing Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1849; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. Organized Crime: The Role of Ornament in Contemporary Architecture. In ACADIA Regional 2011: Parametricism: (SPC); Association for Computer-Aided Design in Architecture (ACADIA): Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011; pp. 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sağlam, H. Re-thinking the Concept of “Ornament” in Architectural Design. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 122, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontius, D. Ornament as Narrative: A Framework for Reading Ornament in the Twenty-First Century. Master’s Thesis, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, USA, May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, D. Robert Venturi and His Contributions to Postmodern Architecture. Oshkosh Sch. 2008, 3, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Orman, B. Art Nouveau & Gaudí: The Way of Nature. JCCC Honor. J. 2012, 4, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kırhallı, T.; Koçyiğit, R. Rethinking Changing Aesthetic Approaches in Architectural Theories. Güzel Sanatlar Fakültesi Sanat Derg. 2019, 12, 194–222. [Google Scholar]

- Vrahimis, A. Wittgenstein, Loos, and the Critique of Ornament. Estet. Eur. J. Aesthet. 2021, 58, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabacıoğlu, O. An Onthological Study Regarding the Question of Meaning in Architecture. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2005; pp. 45–51. Available online: https://polen.itu.edu.tr:8443/server/api/core/bitstreams/bfc9fb06-a8a0-481c-afde-ac2343e2e95e/content (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Çelik, Z. Le Corbusieri Orientalism, Colonialism; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 58–77. [Google Scholar]