The Influence of Environmental Factors, Perception, and Participation on Industrial Heritage Tourism Satisfaction—A Study Based on Multiple Heritages in Shanghai

Abstract

1. Introduction

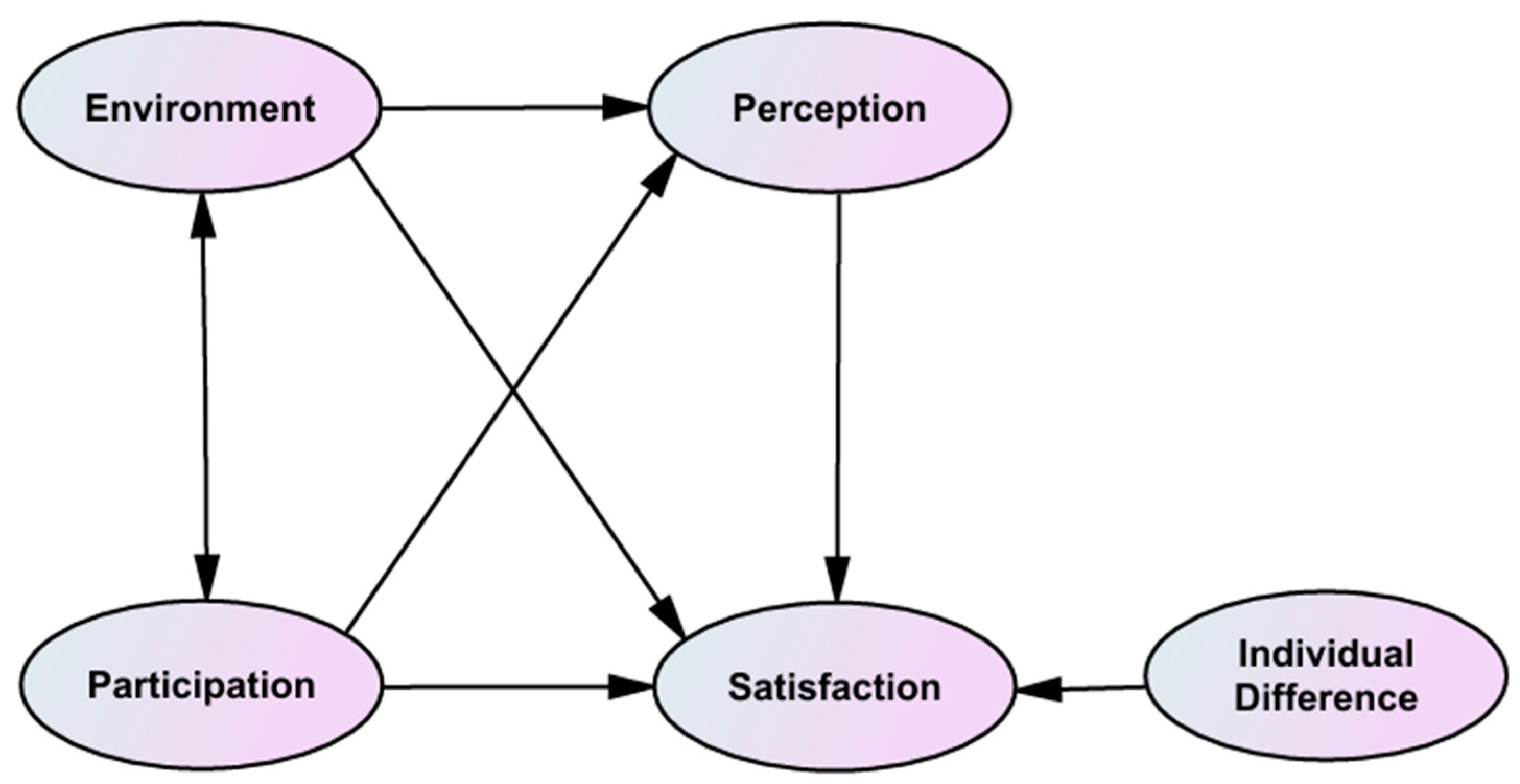

2. Literature Review

2.1. Industrial Heritage Tourism and Experience

2.2. Environmental Factors

2.3. Participation

2.4. Subjective Perception

2.5. Tourists’ Satisfaction

3. Research Design and Methods

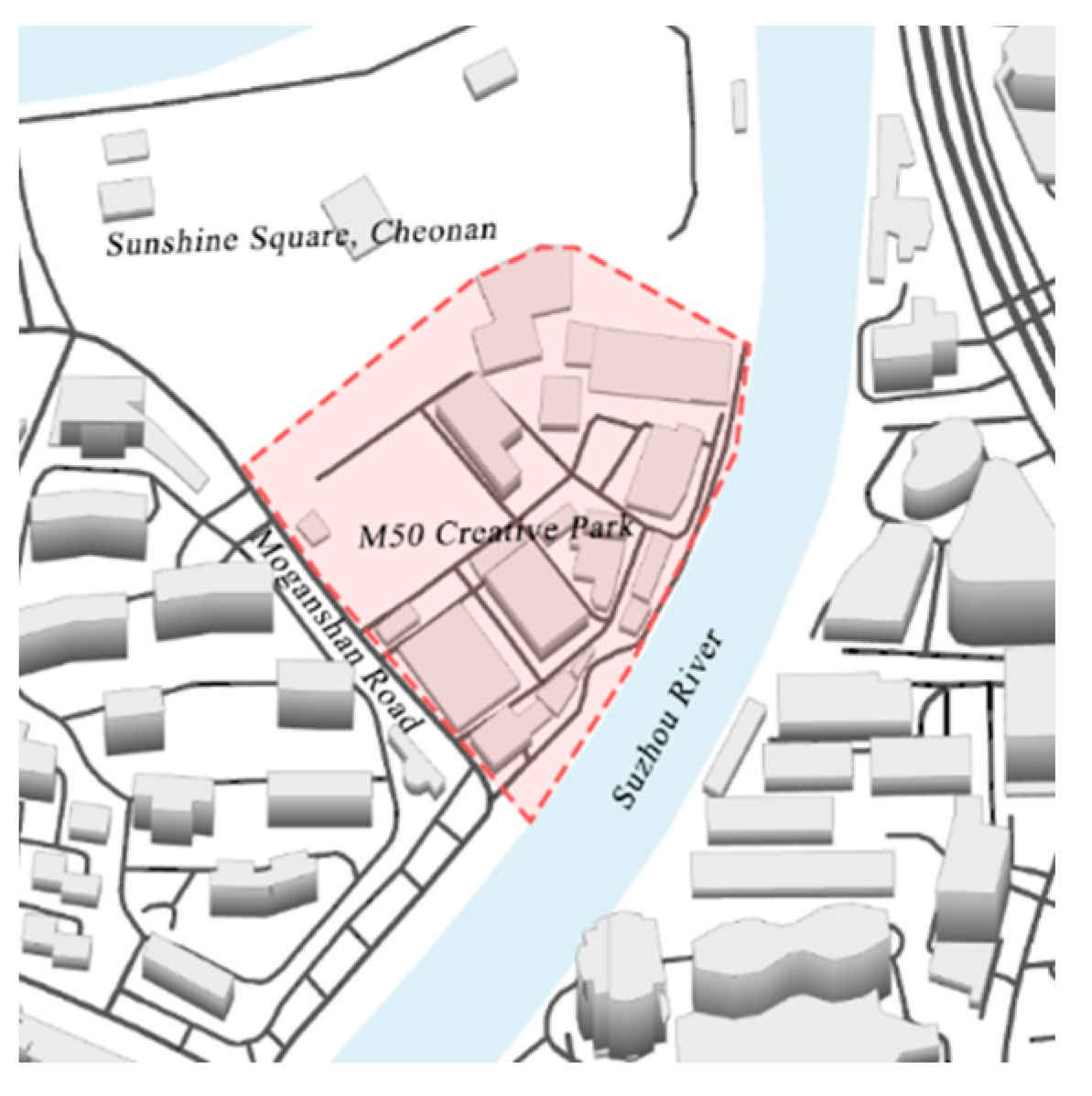

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Data Collection

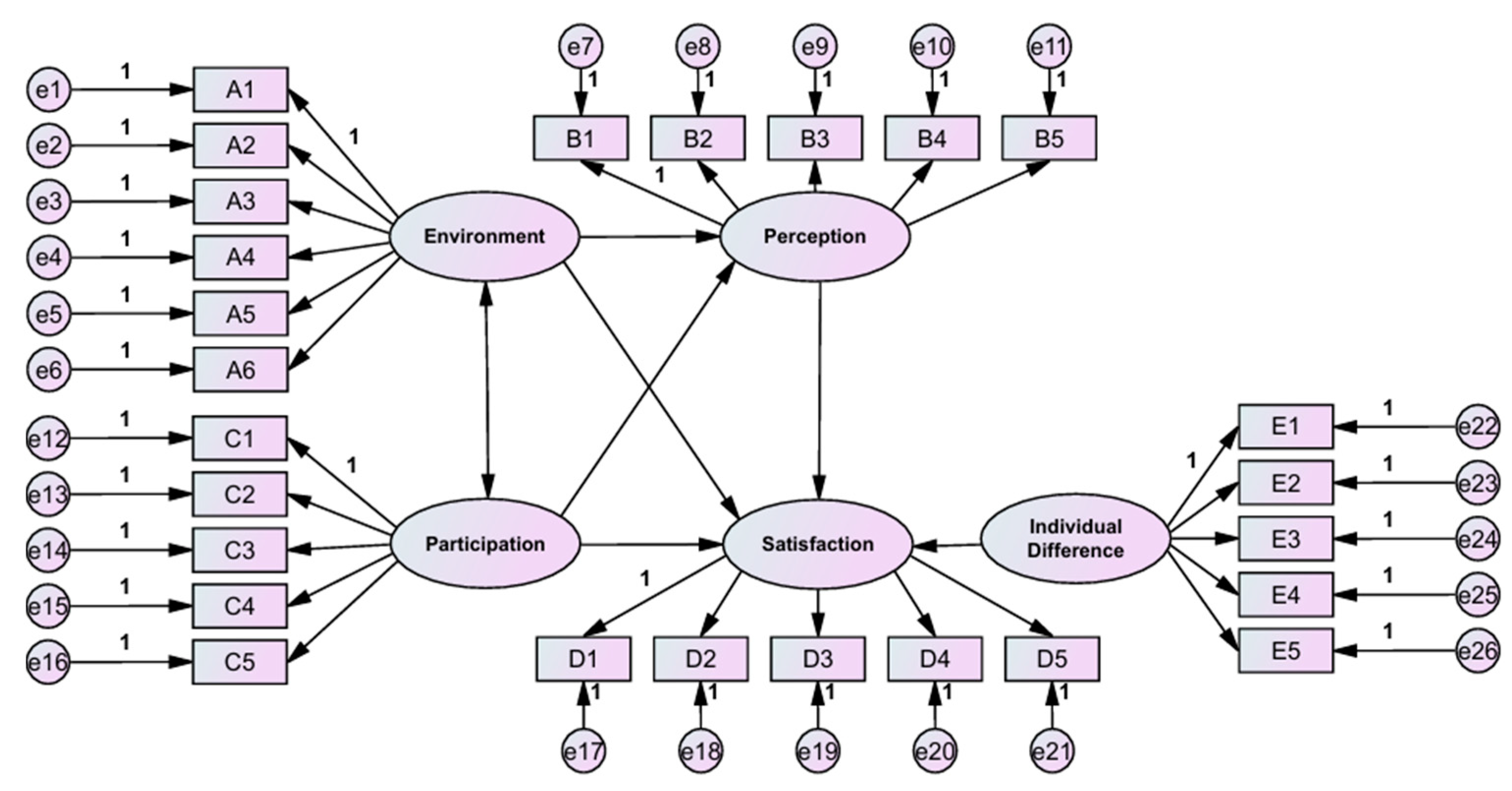

3.3. Survey Measures

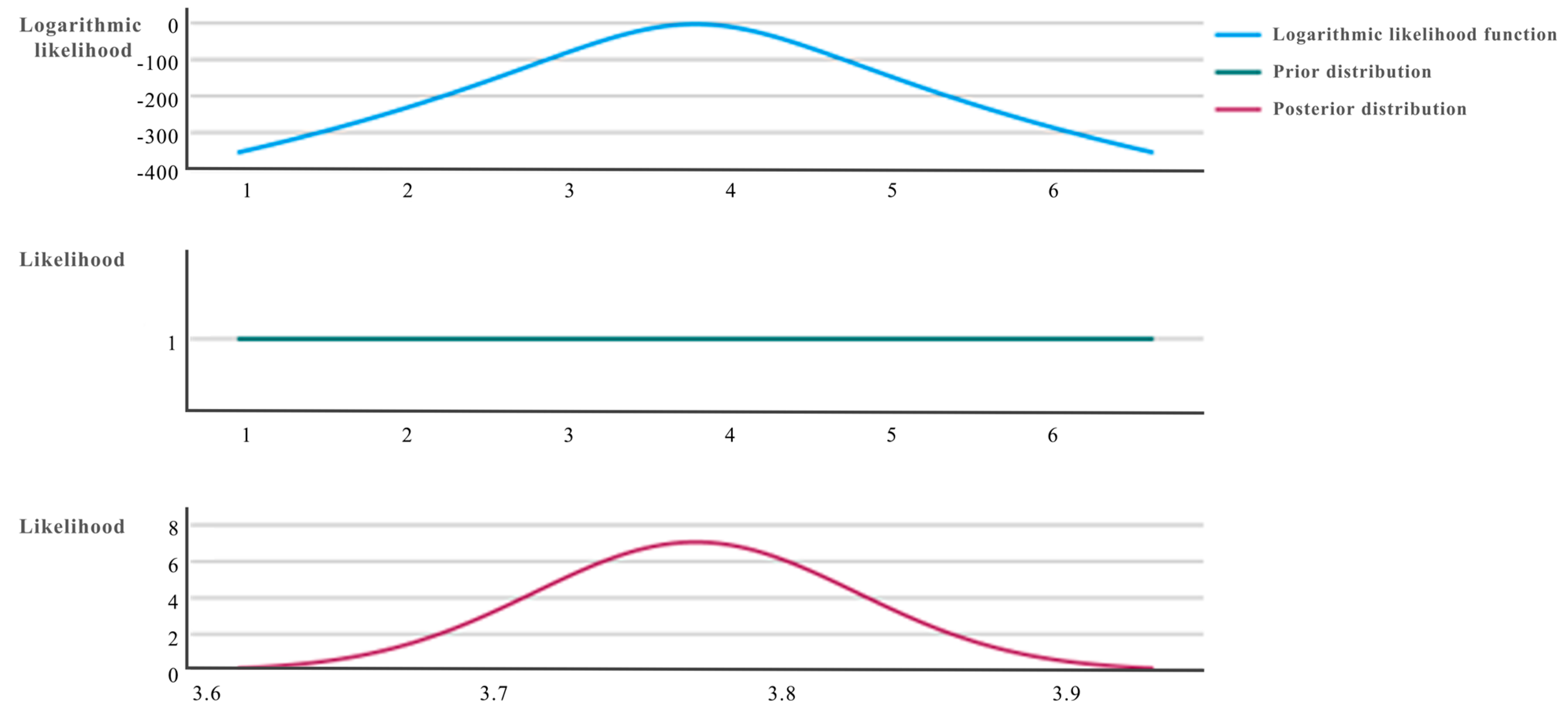

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Sample and Responses

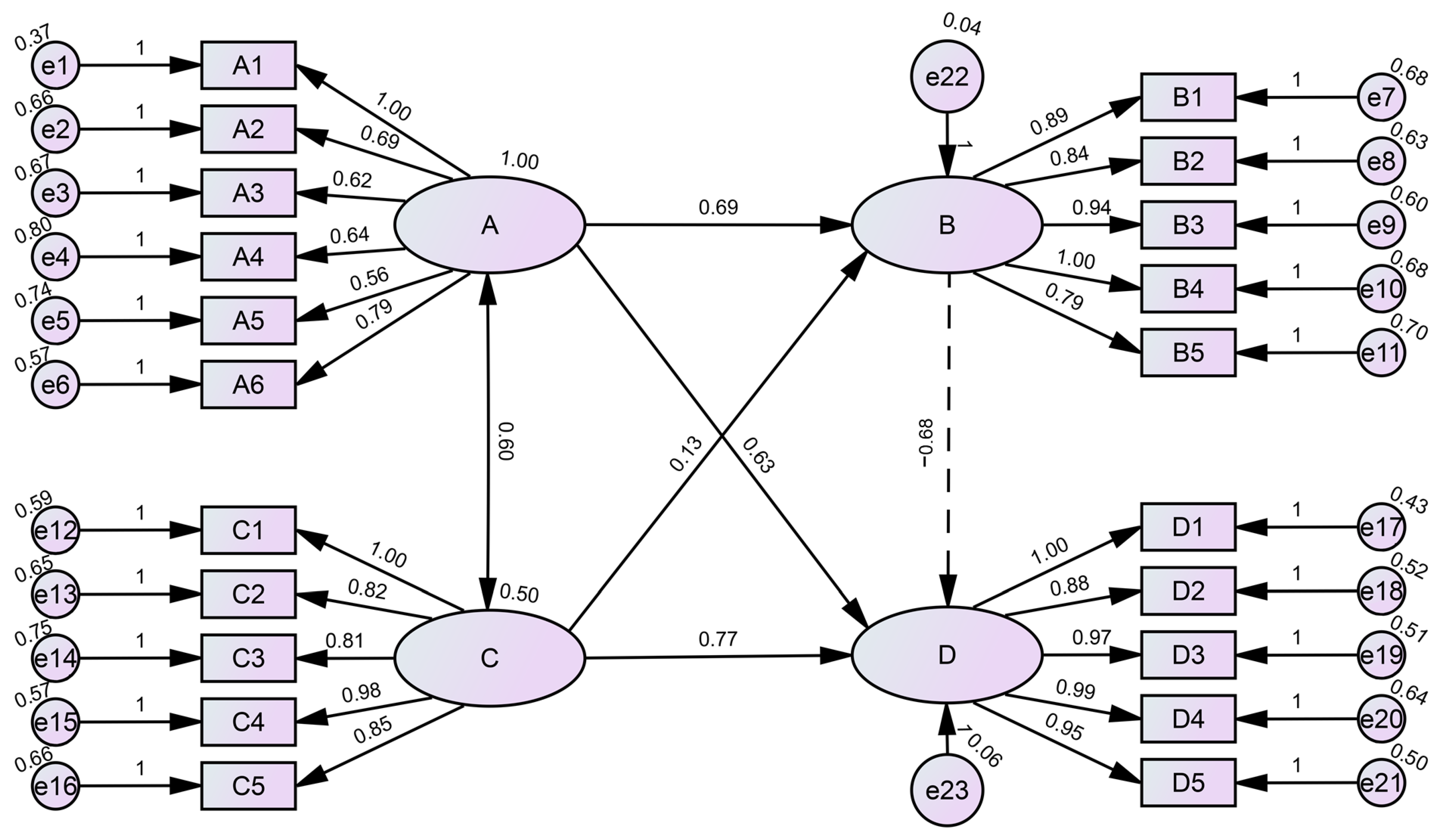

4.2. Measurement Model

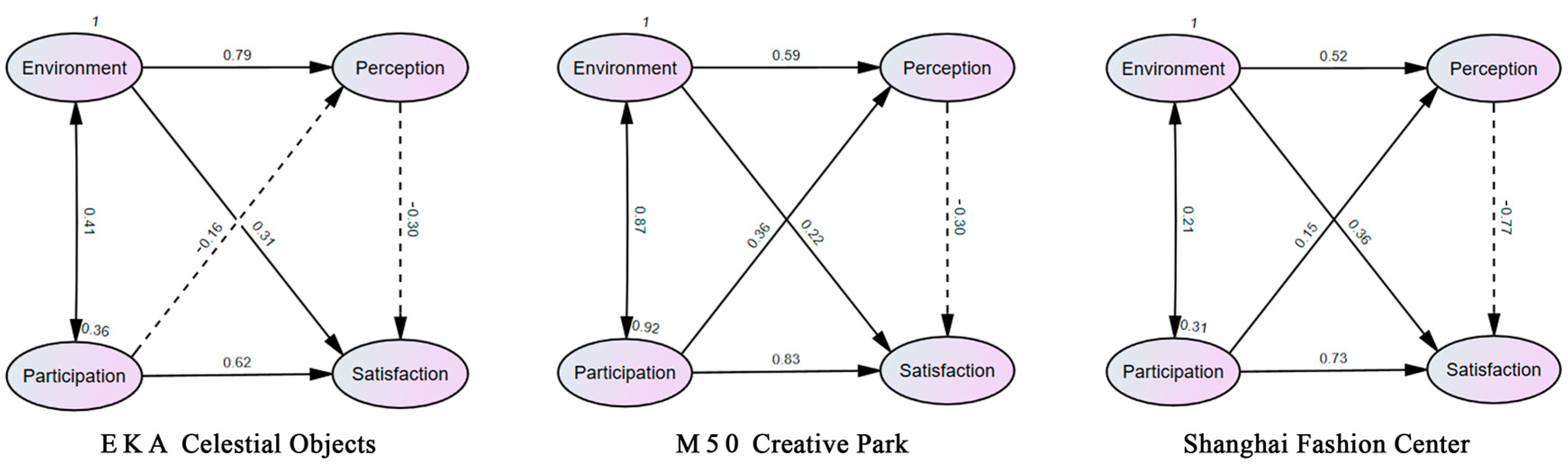

4.3. Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Gender Differences in Activity Participation

6.2. Comparison of Built Environment, Participation, and Tourism Satisfaction

6.3. The Mediating Effect of Subjective Perception

6.4. Hypothesis Testing

6.5. Advice to Managers

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

References

- Douet, J. Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Z. Heritage conservation as a territorialised urban strategy: Conservative reuse of socialist industrial heritage in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, P.; Sobouti, H.; Shahbazi, M. Adaptive re-use of industrial heritage and its role in achieving local sustainability. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJBPA-09-2021-0118/full/html (accessed on 18 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Bertacchini, E.; Frontuto, V. Economic valuation of industrial heritage: A choice experiment on Shanghai BaoSteel industrial site. J. Cult. Herit. 2024, 66, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijkamp, P. Economic valuation of cultural heritage. Econ. Uniqueness Investig. Hist. City Cores Cult. Herit. Assets Sustain. Dev. 2012, 75, 75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Caamaño-Franco, I.; Andrade Suarez, M. The value assessment and planning of industrial mining heritage as a tourism attraction: The case of Las Médulas cultural space. Land 2020, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Su, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Q. Research on global cultural heritage tourism based on bibliometric analysis. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, C. Renovation of industrial heritage sites and sustainable urban regeneration in post-industrial Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2021, 45, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.; Li, X.; Lan, D. A Dual Strategy in the Adaptive Reuse of Industrial Heritage Buildings: The Shanghai West Bund Waterfront Refurbishment. Buildings 2023, 13, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbelkasy, M.I. Sustainability of heritage buildings reuse between competition and integration case study (Fuwwah and Rosetta). J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2024, 15, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardopoulos, I. Critical sustainable development factors in the adaptive reuse of urban industrial buildings. A fuzzy DEMATEL approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eray, E.; Sanchez, B.; Haas, C. Usage of Interface Management System in Adaptive Reuse of Buildings. Buildings. 2019, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xing, W.; Lu, E.; Jia, T. Research on indoor experience satisfaction based on industrial heritage renovation: A case study of museum model. J. Hebei Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 14, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Zhang, T. Authenticity and Quality of Industrial Heritage as the Drivers of Tourists’ Loyalty and Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Song, Y.; Zhao, Y. An Evaluation Study on Tourists’ Environmental Satisfaction after Re-Use of Industrial Heritage Buildings. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Song, H.; Chen, N.; Shang, W. Roles of tourism involvement and place attachment in determining residents’ attitudes toward industrial heritage tourism in a resource-exhausted city in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yu, L.; Fang, H.; Wu, J. Research on the Protection and Reuse of Industrial Heritage from the Perspective of Public Participation—A Case Study of Northern Mining Area of Pingdingshan, China. Land 2022, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swensen, G.; Stenbro, R. Urban planning and industrial heritage—A Norwegian case study. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab, P.; Alborzi, G. Toward developing a sustainable regeneration framework for urban industrial heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 12, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desing, H.; Brunner, D.; Takacs, F.; Nahrath, S.; Frankenberger, K.; Hischier, R. A circular economy within the planetary boundaries: Towards a resource-based, systemic approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopowicz, D. Implementation of the principles of sustainable economy development as a key element of the pro-ecological transformation of the economy towards green economy and circular economy. Int. J. New Econ. Soc. Sci. IJONESS 2020, 11, 417–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvério, A.C.; Ferreira, J.; Fernandes, P.O.; Dabić, M. How does circular economy work in industry? Strategies, opportunities, and trends in scholarly literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.H.; Wu, R.Y. Mediating effect of brand image and satisfaction on loyalty through experiential marketing: A case study of a sugar heritage destination. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.R.; McMurray, I.; Brownlow, C. SPSS Explained; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.S. Revaluing Industrial Heritage: Participatory Governance in Urban’s Forestry Heritage and Historical Bridge Conservation. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2017, 8, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, D.T. (Ed.) Heritage place, leisure and tourism. In Heritage, Tourism and Society; Mansell: London, UK, 1995; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, J.T.; Morrison, A.M.; Alzua, A. Cultural and heritage tourism: Identifying niches for international travelers. J. Tour. Stud. 1998, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Heritage tourism in the 21st century: Valued traditions and new perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, J.; Henama, U.S. Growing heritage tourism and social cohesion in South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chon, K.S.; Weber, K. Convention Tourism: International Research and Industry Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harfst, J.; Sandriester, J.; Fischer, W. Industrial heritage tourism as a driver of sustainable development? A case study of Steirische Eisenstrasse (Austria). Sustainability 2021, 13, 3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.; Chieng, M. Building consumer-brand relationship: A cross-cultural experiential view. Psychol. Mark. 2006, 23, 927–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.A.; Suh, J. Transaction-specific satisfaction and overall satisfaction: An empirical analysis. J. Serv. Mark. 2000, 14, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhang, X.; Pang, Y. Evaluation of Satisfaction with Spatial Reuse of Industrial Heritage in High-Density Urban Areas: A Case Study of the Core Area of Beijing’s Central City. Buildings 2024, 14, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. Industrial Heritage Tourism; Channel View Publications: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.C.; Wall, G.; Yu, W.C. Creative turns in the use of industrial resources for heritage tourism in Taiwan. J. China Tour. Res. 2016, 12, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Affirming authenticity—Consuming cultural heritage. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 589–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine II, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B.H. Experiential Marketing: How to Get Customers to Sense, Feel, Think, Act, Relate to Your Company and Brands; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bazazzadeh, H.; Nadolny, A.; Attarian, K.; Safar Ali Najar, B.; Hashemi Safaei, S.S. Promoting Sustainable Development of Cultural Assets by Improving Users’ Perception through Space Configuration; Case Study: The Industrial Heritage Site. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Evaluating the experiences and benefits gained by tourists visiting a socio-industrial heritage museum: An application of ASEB grid analysis to Blists hill open-air museum, the Ironbridge Gorge museum, United Kingdom. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 1995, 14, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, A.J. Into the tourist’s mind: Understanding the value of the heritage experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1999, 8, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wei, C.; Nie, L. Experiencing authenticity to environmentally responsible behavior: Assessing the effects of perceived value, tourist emotion, and recollection on industrial heritage tourism. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1081464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W.; Xu, Y. Sustainable development and the rehabilitation of a historic urban district–Social sustainability in the case of Tianzifang in Shanghai. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, U. The experience of emotion: Situational influences on the elicitation and experience of emotions. In Emotions, Qualia, and Consciousness; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 2001; pp. 386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Bottero, M.; D’Alpaos, C.; Oppio, A. Ranking of adaptive reuse strategies for abandoned industrial heritage in vulnerable contexts: A multiple criteria decision aiding approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añibarro, M.V.; Andrade, M.J.; Jiménez-Morales, E. A multicriteria approach to adaptive reuse of industrial heritage: Case studies of riverside power plants. Land 2023, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Shapoval, V.; Ellis, T. Customer satisfaction and its measurement in hospitality enterprises: A revisit and update. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 2–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.M.; Baumgartner, H. The role of consumption emotions in the satisfaction response. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoli, C.; Iannantuono, M.; Giannakopoulos, V.; Fotopoulou, A.; Ferrante, A.; Garagnani, S. Building information modeling as an effective process for the sustainable re-shaping of the built environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, T.; Yildiz, D. Exploring the influence of the built environment on human experience through a neuroscience approach: A systematic review. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lee, J.; Jiang, B.; Kim, G. Revitalization of the waterfront park based on industrial heritage using post-occupancy evaluation—A case study of Shanghai (China). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Biedenbach, G.; Marell, A. The impact of customer experience on brand equity in a business-to-business services setting. J. Brand Manag. 2010, 17, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T. A study of experiential quality, perceived value, heritage image, experiential satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2017, 41, 904–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hu, X.; Lee, H.M.; Zhang, Y. The impacts of ecotourists’ perceived authenticity and perceived values on their behaviors: Evidence from Huangshan World Natural and Cultural Heritage Site. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, C. Gender and emotion expression, experience, physiology and well being: A psychological perspective. In Gender and Emotion: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Peter Lang: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Grzymisławska, M.; Puch, E.A.; Zawada, A.; Grzymisławski, M. Do nutritional behaviors depend on biological sex and cultural gender? Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 29, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neculaesei, A.N. Culture and gender role differences. Cross-Cult. Manag. J. 2015, 17, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, M.P.; Price, L.L. Differentiating between cognitive and sensory innovativeness: Concepts, measurement, and implications. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 20, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithari, C.; Frantzidis, C.A.; Papadelis, C.; Vivas, A.B.; Klados, M.A.; Kourtidou-Papadeli, C.; Pappas, C.; Ioannides, A.A.; Bamidis, P.D. Are females more responsive to emotional stimuli? A neurophysiological study across arousal and valence dimensions. Brain Topogr. 2010, 23, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, T.; Desmond, J.E.; Zhao, Z.; Gabrieli, J.D. Sex differences in the neural basis of emotional memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10789–10794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, E.N.; Picho, K.; McArdle, J.J.; Villagra, V.; Dierker, L.; Iordache, E. The paired t-test as a simple latent change score model. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, T.F. Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2003, 37, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y. An approach to assess the value of industrial heritage based on Dempster–Shafer theory. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 32, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S.; Chiu, Y.; Wang, C. The visitor behavioral consequences of experiential marketing: An empirical study on Taipei Zoo. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2007, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.-Y.; Koo, C. The Role of Augmented Reality for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Korea. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Shen, C.; Wang, E.; Hou, Y.; Yang, J. Impact of the perceived authenticity of heritage sites on subjective well-being: A study of the mediating role of place attachment and satisfaction. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Location | Space | Year Founded | Functional Use | Annual Income | Industrial Attribute |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EKA | Jinqiao Road Pudong District | 66,600 m2 | 2023 | Creative Industry Park | None | Nautical instrument factory |

| SFC | Yangshupu Road Yangpu District | 120,800 m2 | 2010 | Fashion Warehouse | Over 1.15 billion * | Cotton textile factory |

| M50 | Moganshan Road Putuo District | 41,606 m2 | 2000 | Art and Creative Park | Over 80 million ** | Woolen factory |

| Variable | No. | Constructs/Indicators | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual attribute feature | ER | E1 Gender | Male = 1, Female = 2 |

| E2 Age | 14~18 = 1, 19~44 = 2, 45~60 = 3, 61 or above = 4 | ||

| E3 Educational level | Primary = 1, Junior = 2, High school = 3, College = 4, Undergraduate = 5, Master’s degree or above = 6 | ||

| E4 Monthly income (RMB) | 2199 or below = 1 2200~7499 = 2 7500~11,999 = 3 12,000 or above = 4 | ||

| E5 Transportation options | Subway = 1, Bus = 2, Sedan = 3, Motorcycle = 4, Bicycle = 5, Walk = 6 | ||

| Environment | A | A1 Pleasant environment | Strongly disagree = 1 Disagree = 2 Normal = 3 Agree = 4 Strongly agree = 5 |

| A2 Clear sense of direction during play | |||

| A3 Embodies the industrial culture | |||

| A4 The interior design of the building is aesthetic | |||

| A5 Complete supporting facilities | |||

| A6 The features of heritage are historic | |||

| Perception | B | B1 Bring back certain memories of your past | Strongly disagree = 1 Disagree = 2 Normal = 3 Agree = 4 Strongly agree = 5 |

| B2 Learn more about industrial culture | |||

| B3 A place where culture can be passed on | |||

| B4 Willing to carefully experience the industrial culture here | |||

| B5 It gives me pleasure to visit here | |||

| Participation | C | C1 High participation in cultural activities | Strongly disagree = 1 Disagree = 2 Normal = 3 Agree = 4 Strongly agree = 5 |

| C2 High participation in consumer activities | |||

| C3 High participation in recreational activities | |||

| C4 Strong motivation for active participation | |||

| C5 It has educational significance for visitors | |||

| Satisfaction | D | D1 Willing to come here again for sightseeing and leisure | Strongly disagree = 1 Disagree = 2 Normal = 3 Agree = 4 Strongly agree = 5 |

| D2 Willing to recommend this place to my relatives and friends | |||

| D3 Willing to respect its industrial heritage and culture | |||

| D4 The experience is aligned with social media and online promotion | |||

| D5 I was satisfied with the tour overall |

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Monthly income (RMB) | ||||

| Male | 172 | 47.5 | <2200 | 43 | 11.8 |

| Female | 190 | 52.5 | 2200–7499 | 105 | 28.9 |

| Age | 7500–11,999 | 136 | 37.6 | ||

| 14–18 | 20 | 5.6 | >12,000 | 78 | 21.7 |

| 19–44 | 182 | 50.3 | Means of transportation | ||

| 45–60 | 130 | 36.0 | Subway | 101 | 28.0 |

| 61 and older | 30 | 8.1 | Bus | 66 | 18.3 |

| Education | Sedan | 90 | 24.8 | ||

| Primary or below | 17 | 4.7 | Motorcycle/battery car | 38 | 10.6 |

| Middle school | 43 | 11.8 | Bicycle | 36 | 9.9 |

| High school/vocational school | 51 | 14.0 | Walk | 31 | 8.4 |

| Junior college | 71 | 19.6 | |||

| University | 135 | 37.3 | |||

| Postgraduate or above | 45 | 12.7 | |||

| x2/df | RMSEA | CFI | AGFI | GFI | TLI | IFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | <3 | <0.080 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 | >0.8 |

| Actual | 2.079 | 0.058 | 0.896 | 0.871 | 0.898 | 0.881 | 0.897 |

| Explicit Variable | Route | Variable | EKA | M50 | SFC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | <--- | Environment | 0.370 *** | 1.000 | 0.150 * |

| A2 | <--- | 0.550 *** | 0.700 *** | 0.480 *** | |

| A3 | <--- | 0.580 ** | 0.660 *** | 0.400 *** | |

| A4 | <--- | 0.500 *** | 0.620 *** | 0.430 *** | |

| A5 | <--- | 0.510 ** | 0.610 *** | 0.420 *** | |

| A6 | <--- | 1.000 | 0.920 *** | 1.000 | |

| B1 | <--- | Perception | 0.730 ** | 0.920 *** | 1.000 |

| B2 | <--- | 1.000 | 0.690 ** | 0.910 *** | |

| B3 | <--- | 0.970 *** | 0.820 *** | 0.940 *** | |

| B4 | <--- | 0.660 ** | 1.000 | 0.860 *** | |

| B5 | <--- | 0.520 ** | 0.710 ** | 0.870 *** | |

| C1 | <--- | Participation | 0.660 ** | 1.000 | 0.570 * |

| C2 | <--- | 0.610 ** | 0.800 *** | 0.440 * | |

| C3 | <--- | 0.900 *** | 0.630 ** | 1.000 | |

| C4 | <--- | 0.830 ** | 0.880 *** | 0.840 *** | |

| C5 | <--- | 1.000 | 0.580 * | 0.820 *** | |

| D1 | <--- | Satisfaction | 0.660 ** | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| D2 | <--- | 0.610 ** | 0.840 ** | 0.720 ** | |

| D3 | <--- | 0.900 *** | 0.900 *** | 0.760 ** | |

| D4 | <--- | 0.830 ** | 1.000 | 0.960 *** | |

| D5 | <--- | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.700 ** |

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | PCCs | ||||||

| Sig | |||||||

| A2 | PCCs | 0.454 | |||||

| Sig | <0.001 | ||||||

| A3 | PCCs | 0.442 | 0.278 | ||||

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| A4 | PCCs | 0.324 | 0.209 | 0.247 | |||

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| A5 | PCCs | 0.323 | 0.245 | 0.233 | 0.294 | ||

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| A6 | PCCs | 0.410 | 0.360 | 0.323 | 0.382 | 0.371 | |

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | PCCs | |||||

| Sig | ||||||

| C2 | PCCs | 0.346 | ||||

| Sig | <0.001 | |||||

| C3 | PCCs | 0.350 | 0.271 | |||

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| C4 | PCCs | 0.361 | 0.316 | 0.320 | ||

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| C5 | PCCs | 0.321 | 0.251 | 0.230 | 0.384 | |

| Sig | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Levene’s Test for Variance Equality | Mean Equivalence t-Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Variable | F | Significance | t | DOF | Significance | Mean Difference | Standard Error Difference | |

| C1 | CV | 0.234 | 0.629 | 0.387 | 320 | 0.699 | 0.04246 | 0.10968 |

| ANOVA | 0.388 | 318.969 | 0.698 | 0.04246 | 0.10945 | |||

| C2 | CV | 0.836 | 0.361 | −0.547 | 320 | 0.585 | −0.05813 | 0.10621 |

| ANOVA | −0.547 | 315.651 | 0.585 | −0.05813 | 0.10630 | |||

| C3 | CV | 0.269 | 0.604 | −0.574 | 320 | 0.566 | −0.06397 | 0.11137 |

| ANOVA | −0.573 | 313.651 | 0.567 | −0.06397 | 0.11160 | |||

| C4 | CV | 0.135 | 0.713 | −0.186 | 320 | 0.852 | −0.02015 | 0.10817 |

| ANOVA | −0.186 | 318.069 | 0.852 | −0.02015 | 0.10805 | |||

| C5 | CV | 0.698 | 0.404 | −0.752 | 320 | 0.452 | −0.08118 | 0.10791 |

| ANOVA | −0.754 | 319.01 | 0.451 | −0.08118 | 0.10768 | |||

| Measured Variable | Gender | Avg | Standard Deviation | Mean Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 1 | 3.8235 | 0.96502 | 0.07765 |

| 2 | 3.7811 | 1.00267 | 0.07713 | |

| C2 | 1 | 3.8235 | 0.96052 | 0.07765 |

| 2 | 3.8817 | 0.94375 | 0.07260 | |

| C3 | 1 | 3.6993 | 1.02009 | 0.08247 |

| 2 | 3.7633 | 0.97752 | 0.07519 | |

| C4 | 1 | 3.8497 | 0.95815 | 0.07746 |

| 2 | 3.8698 | 0.97936 | 0.07534 | |

| C5 | 1 | 3.8301 | 0.94445 | 0.07635 |

| 2 | 3.9112 | 0.98702 | 0.07592 |

| Hypothesized Path | Site | β1 | β2 | Hypothesis Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Environment→Satisfaction> Participation→Satisfaction | EKA | 0.31 | 0.62 | Not Supported |

| M50 | 0.22 | 0.83 | ||

| SFC | 0.36 | 0.73 | ||

| H2: Environment→Participation | EKA | 0.41 | Supported | |

| M50 | 0.87 | |||

| SFC | 0.21 | |||

| H3: Satisfaction→C1 | EKA | 0.66 | Supported | |

| M50 | 1.00 | |||

| SFC | 0.57 | |||

| H4: Satisfaction→C2 | EKA | 0.61 | Supported | |

| M50 | 0.80 | |||

| SFC | 0.44 | |||

| H5: Satisfaction→C3 | EKA | 0.90 | Supported | |

| M50 | 0.63 | |||

| SFC | 1.00 | |||

| H6: Participation→Satisfaction> Environment→Satisfaction | EKA | 0.62 | 0.31 | Supported |

| M50 | 0.83 | 0.22 | ||

| SFC | 0.73 | 0.36 | ||

| H7: Perception→Satisfaction | EKA | −0.30 | Not Supported | |

| M50 | −0.30 | |||

| SFC | −0.77 | |||

| H8: Environment →Perception→Satisfaction | EKA | 0.79 | −0.30 | Supported |

| M50 | 0.59 | −0.30 | ||

| SFC | 0.52 | −0.77 | ||

| H9: Participation→Perception→Satisfaction | EKA | −0.16 | −0.30 | Supported |

| M50 | 0.36 | −0.30 | ||

| SFC | 0.15 | −0.77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Z.; Yao, J.; Shi, J. The Influence of Environmental Factors, Perception, and Participation on Industrial Heritage Tourism Satisfaction—A Study Based on Multiple Heritages in Shanghai. Buildings 2024, 14, 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113508

Fang Z, Yao J, Shi J. The Influence of Environmental Factors, Perception, and Participation on Industrial Heritage Tourism Satisfaction—A Study Based on Multiple Heritages in Shanghai. Buildings. 2024; 14(11):3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113508

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Zhiguo, Jiachen Yao, and Jianing Shi. 2024. "The Influence of Environmental Factors, Perception, and Participation on Industrial Heritage Tourism Satisfaction—A Study Based on Multiple Heritages in Shanghai" Buildings 14, no. 11: 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113508

APA StyleFang, Z., Yao, J., & Shi, J. (2024). The Influence of Environmental Factors, Perception, and Participation on Industrial Heritage Tourism Satisfaction—A Study Based on Multiple Heritages in Shanghai. Buildings, 14(11), 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14113508