Abstract

Historical buildings have inhabited every epoch of history. Some of these built legacies are now in ruins and dying whilst others are somewhat undamaged. Knowledge of conservation techniques available today has allowed us to understand more innovative ways of conserving the built heritage. Such techniques are, however, incompatible with the building materials available in our historical epoch and environment. People seek to reclaim the forgotten cultural heritage in the midst of the heritage conservation era while bearing in mind that previous work seldom takes into account the inventive preservation methods of today. This study aims to explore the innovative built heritage conservation practice in the Kano metropolis, to detect deterioration and incorporate traditional wisdom and contemporary innovation according to modern urban development. The study adopted qualitative research with a descriptive approach. The descriptive research explains, examines, and interprets prevailing practices, existing situations, attitudes, reasons, and on-going processes, while the qualitative research approach uses spatial analysis methods (direct assessment of physical characteristics of the selected buildings) and focus group discussion (FGD) sessions with the custodians, prominent elderly persons, or ward head (Mai Unguwa) from each of the selected buildings. In this work, we found it necessary to survey 29 historical buildings of which three of the historic buildings from pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial architecture were purposively sampled for inclusion. This is on the basis of their value formation, processes, phenomena, and typology. The findings reveal that deterioration is due to decaying plaster and paint, moist walls, deformed openings, sagging roofs, wall cracks, roof leakages, exit spouts, stains, and corrosion. Other factors include microbes and termite attacks, inappropriate use and neglect, civilization, and inappropriate funding. Conservation was performed to avert the amount of decay while the techniques in practice are documentation methods and treatment interventions with no implementation of diagnostic methods. It further unveils the potential benefits of local treatment, as evidenced by the intervention at the Dorayi palace segment, the use of “makuba” (milled locust bean pod) to stabilize the geotechnical performance of “tubali” (local mud bricks) to improve its potency. This milled locust bean pod also serves as the water repellent consolidant in “laso” (local) plaster, which has proven to be eco-friendly, non-toxic, and effective in wall rendering. The need for immediate implementation of diagnosis techniques in the conservation of architectural heritage in the municipality and elsewhere in Nigeria and beyond is eminent. Intervention and implementation of policies, appropriate funding, and mobilization, raising awareness and sensitization on the value, significance, and state of affairs of our cultural heritage is also paramount.

1. Introduction

The philosophy of conservation and restoration began in the late 20th century, thanks to the early architectural institutes. Those institutes promoted the procedures to safeguard and preserve buildings in their existing situation and protect them from decay and deterioration [1]. They also point out that, Architect should put in place the prospects to achieve attaining the age of the most impeccable monument or heritage Thus, what makes metropolitan architectural heritage exceptional is its endurance in time; it often defies damage and natural tragedies.

The paucity of built heritage and its permanent abandonment over time call for the preservation, rehabilitation, and restoration of historical monuments. This includes the prudent management of inadequate susceptible assets, such as built heritage and monuments [2]. As such, the conservation of built heritage is critical to the provision of a sense of belonging and correlates to the rapidly transforming globe for the present and upcoming generations.

Even though not all traditions require being old-fashioned [1], no tradition or custom is to be preserved if it disagrees with a communal authentic interest of a similar nature. Neither should one be given up to perish only because it is an ancient practice. Cultural heritage is an imperative asset for the development of the local neighborhood, which is also an essential feature that enhances a city’s impact on self-identity, quality of life, and community integration. Thus, it determines the investment and tourism aesthetics of sites, forming accordingly a basis for products of cultural business and diverse economic conduct [3].

Additionally, cultural heritage and historical buildings form important assets for community development. Their value, therefore, depends on how modern society uses them as social, political or economic resources [4]. These assets, particularly in developed countries, have constantly enjoyed public concern such that they benefit from statutory protection [3,5].

Buildings of aesthetic, cultural, religious, historical, or economic significance inherited from ancient times have also been considered to be architectural heritage in Nigeria. These consist of pre-colonial buildings, African–Brazilian buildings, colonial buildings, and post-colonial buildings. These buildings were built in the midst of creativity and expertise in various regions of the country. A number of these buildings have been pronounced national monuments [6], whilst some are on the waiting list [7]. They are made from materials, such as wood, brass, clay/mud, stone, palm fronds, metal, raffia, and date palm [8]. The use of these materials arose due to their accessibility and economic benefits in the area where the structures were built.

The quest to preserve Nigeria’s built heritage emerges not only for its socio-cultural and economic importance but also because of its degradation status. Typically, materials used to erect architectural heritage buildings are subject to chemical, physical, and biological decomposition due to weather and anthropogenic actions [9]. Other causes of damage include fire, salt, microbes, and insects [10]. The outcomes of these sources of degradation are perceived as cracks, fragmentation, bulges, crust formation, surfaces, and basal erosion. Building deterioration rates are readily discernible by the ease with which these structures and sites are replaced with new developments. While many buildings of historic significance are left neither unused nor incorporated into the present urban fabric, their conservation is essential and it is precious to safeguard them for current and upcoming generations.

Previous research on the conservation of cultural heritage in the context of Kano includes the conservation of Kano’s ancient city wall and gates [11], heritage landscapes and challenges of climate change [12], challenges of preservation of cultural landscapes in traditional cities [13], conservation and restoration of spatial morphology and techniques [1,14], and an analysis of cultural heritage conservation in Kano [15].

Until now, heritage conservation studies have focused on the mundane preservation strategies that failed to harness the inventive preservation methods of emerging technologies or the innovative past approaches because those studies skipped degradation evaluation and analysis before making recommendations. Although the study by [7] proffers innovative technologies and advances afforded by new knowledge, it does not explore early or traditional knowledge of conservation practice alongside modern urban development. This study identifies this gap.

This study aims to explore the innovative built heritage conservation practice with the intent to (i) review the recent advancement in the conservation of architectural heritage as well as the cultural heritage in Kano metropolis; (ii) examine the degradation state, and implementation of innovative conservation techniques and interventions in some historic and monumental buildings in metropolitan Kano; (iii) recommend the restoration methods, incorporating traditional wisdom and contemporary innovation according to modern urban development. As such, this study stands to answer the following questions: (i). What is the recent advancement in the conservation of architectural heritage? (ii) What is the deterioration state of the selected buildings? (iii) What are the practiced intervention techniques and how can the heritage buildings be conserved, renovated, or retrofitted?

1.1. Cultural Heritage Sites in Kano, Nigeria

In most cities of the developing nations, using Nigeria as a model, the drastic increase of economic routine and quest for prime land in the metropolitan areas threaten the survival of aging reserved monument sites. It has as well been noted that natural and cultural heritage are ever more endangered through devastation by the traditional causes of decay and by transforming social and economic circumstances which intensify the situation of this stock with the phenomena of destruction and damage [16,17].

Cultural heritage in Kano is visible from the perspective that the ancient city is sheathed by the fortification wall, having three local administration expanses known as Dala, Gwale, and the Kano Municipal. The Kano Emirate in the eleventh century was a fundamental piece of the world economy, specifically in Africa, bringing together different commercial goods such as cowhide, iron, and cotton materials to mention but a few. As a result of the blow-up in the Nigerian economy and periodic growth in the number of inhabitants, Kano city could not accommodate strangers, which necessitated protecting the city and further encouraged the building of city walls to safeguard the residents from attack [15].

The old Kano cultural landscape has a compositional layout and a fortunate story that pulls in universal interest in the city. As portrayed in Figure 1, Kano is the greatest enduring stronghold of many cultural sites and events in the west of Africa. Adamu [15] further asserts that the Kano walls were founded based on the vigor of winning wars. The erection of these walls commenced with the work of Sarki Gijimasu in 1100 AD, and was carried on by Sarki Mahammadu Rumfa (1463–1499), Sarki Mahammadu Nazaki (1618–1623), and in 1834–1937 there was further opening out to allow development. These walls were pronounced national landmarks in 1959, with the National Commission for Historical Centers and Landmarks being in control [15].

Figure 1.

Kano Durbar, an annual festival. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2021.

Kano city’s cultural sites were recorded by UNESCO among world heritage sites in its tentative list [15]. They further emphasized that, in 2007, the National Commission of Museums and Monuments (NCMM) are responsible for the protection of the Emir of Kano’s royal palace, revealing the UNESCO world heritage order of the city’s revitalized walls, royal residence, and other prominent places. Over a decade of such acknowledgments by UNESCO, action on the proposal remains immobile and history specialists are alarmed that the unrelenting harm to the strongholds could put in them further danger. The remaining fractions of the revitalized walls of Kano are more imperilled with devastation than at any time in the modern era because of civic strategies that give little concern to heritage conservation. Below are some of the historic sites in Kano.

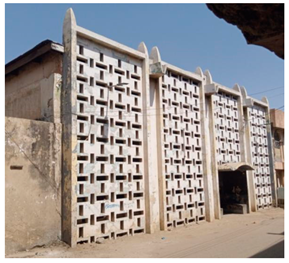

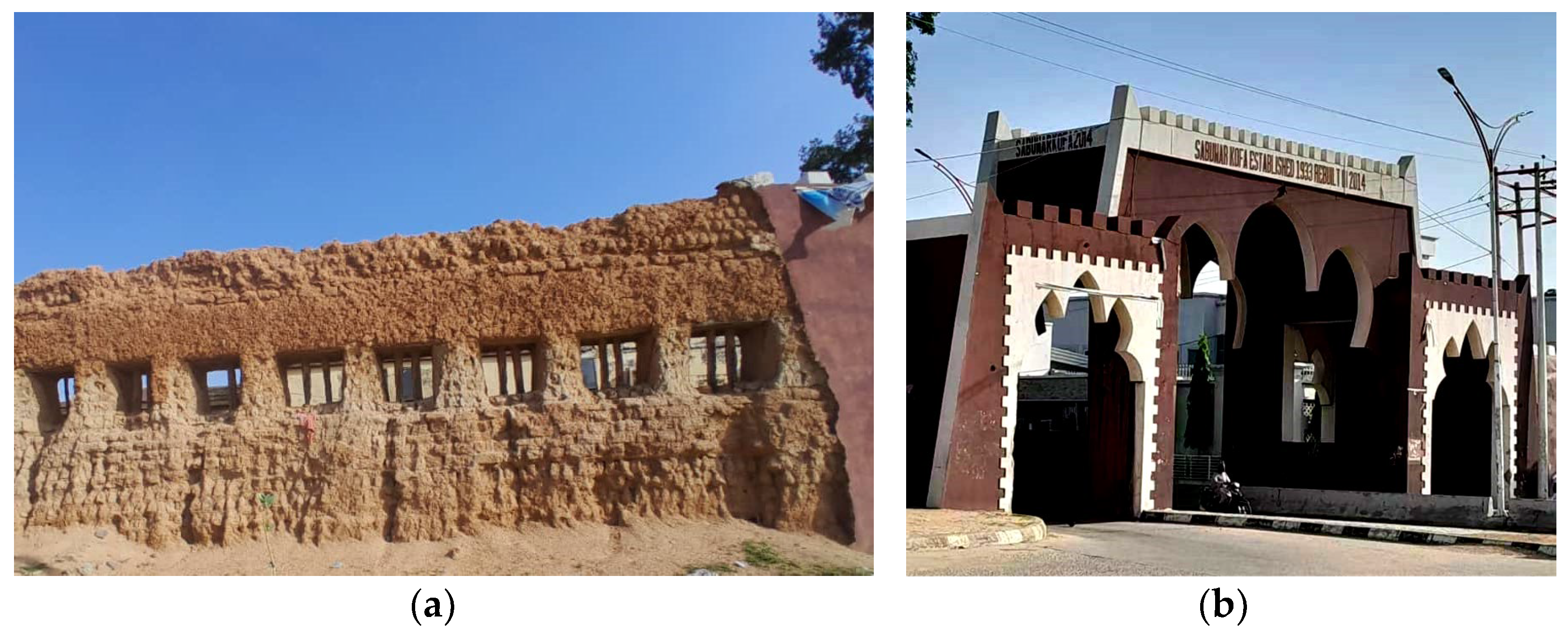

- a.

- City wall and gates: the gates which have 15 doors, as reviewed, entail 8 traditional entryways (erected with mud), 6 modernized doors (reconstructed in concrete), and 1 present-day door (ongoing project with concrete). Nevertheless, the Kano city wall remains a good-natured declaration of African indigenous deployment of its engineering to distinguish political space, as a safeguard and defence structure, a working alliance, and the executive, to mention a few (see Figure 2).

- b.

- Kurmi Market was the foremost and principally recognized marketplace that has been in existence as long as the old Kano city. Its planning was astounding and innovative in the engineering development in the design of the market layout. While investigation reveals that it was rarely conserved, relatively it has undergone a few transformations to the level that it has mislaid its historic signature to unnecessary modernism [13].

- c.

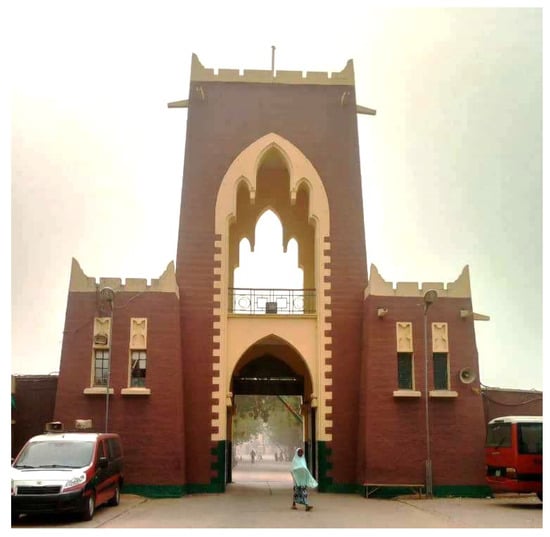

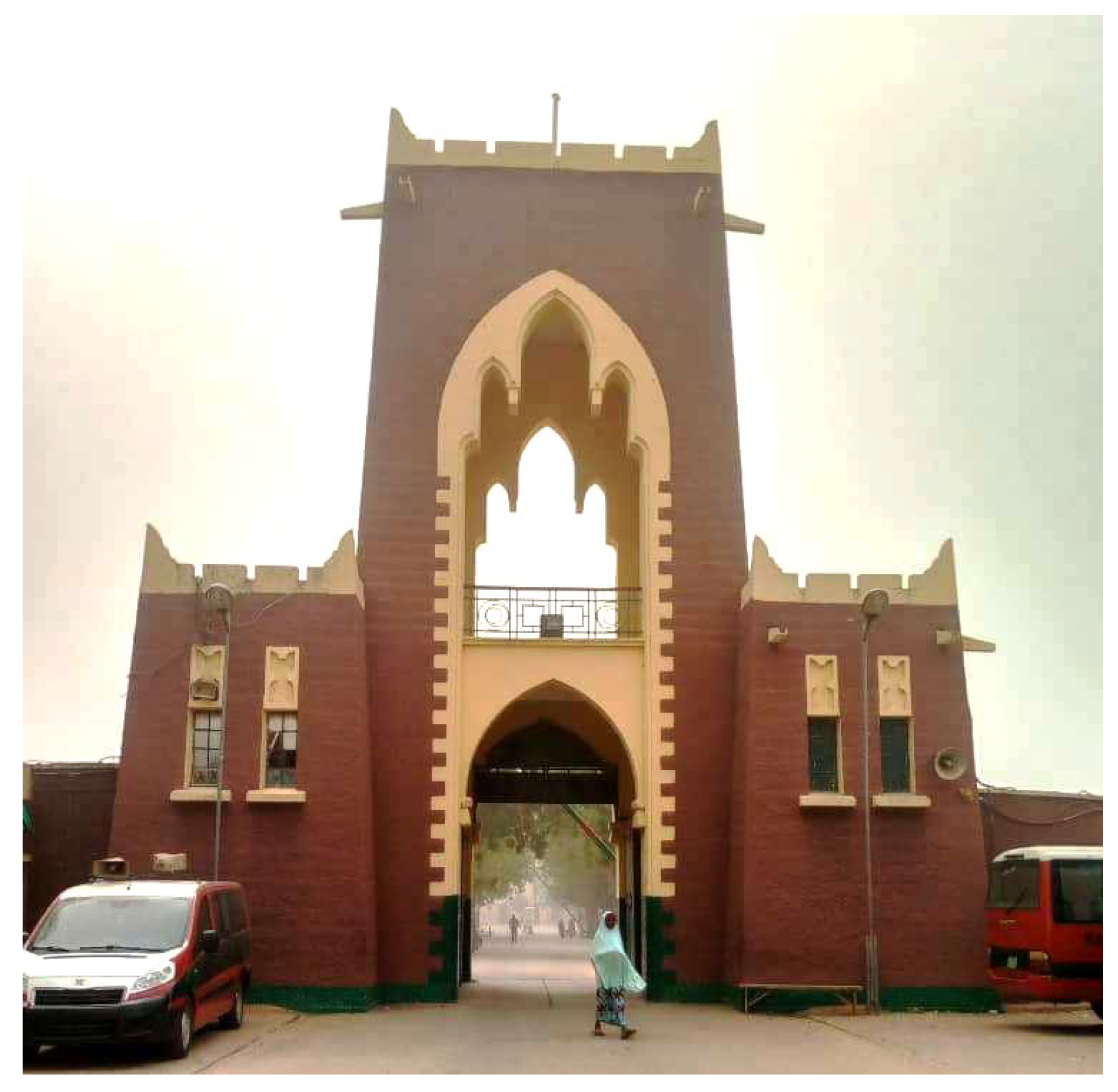

- Kano Emir’s Palace was founded by the Emir of Kano, Sarki Muhammadu Rumfa, who ruled from 1463 to 1499. The palace has three doorways, to be precise Kofar Fatalwa, Kofar Kwaru, and Kofar Kudu (shown in Figure 3). The palace is divided into three fragments; the administrative structure with spaces (Rumfar Kasa, Soran Zauna Lafiya, Soron Bello, and Soron Giwa) is situated in the south. The focal fraction entails the Emir’s family while the northern parts remain for the servants’ and workers’ quarters [15].

Figure 2.

(a) Eroded part of the ancient Kano city wall. (b) One of the rehabilitated city gates in 2014. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

Figure 2.

(a) Eroded part of the ancient Kano city wall. (b) One of the rehabilitated city gates in 2014. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

Figure 3.

Kofar Kudu, one of the prominent entrances of the Emir’s Palace in Kano. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

Figure 3.

Kofar Kudu, one of the prominent entrances of the Emir’s Palace in Kano. Source: Authors’ Fieldwork, 2023.

1.2. Contemporary Methodologies for the Conservation of Architectural Heritage

Inventive technologies have been used in the conservation of heritage buildings around the world with proven efficacy [18,19,20]. These methods include documentation, diagnostic, and treatment, where many of the techniques have proved to be non-destructive and productive.

The non-destructive techniques of heritage conservation make it possible to achieve the quantitative and qualitative aspects required for heritage buildings’ preservation, though such techniques can be elusive and time consuming [21]. Moreover, conservation procedures are classified into three [21,22,23,24] as highlighted below.

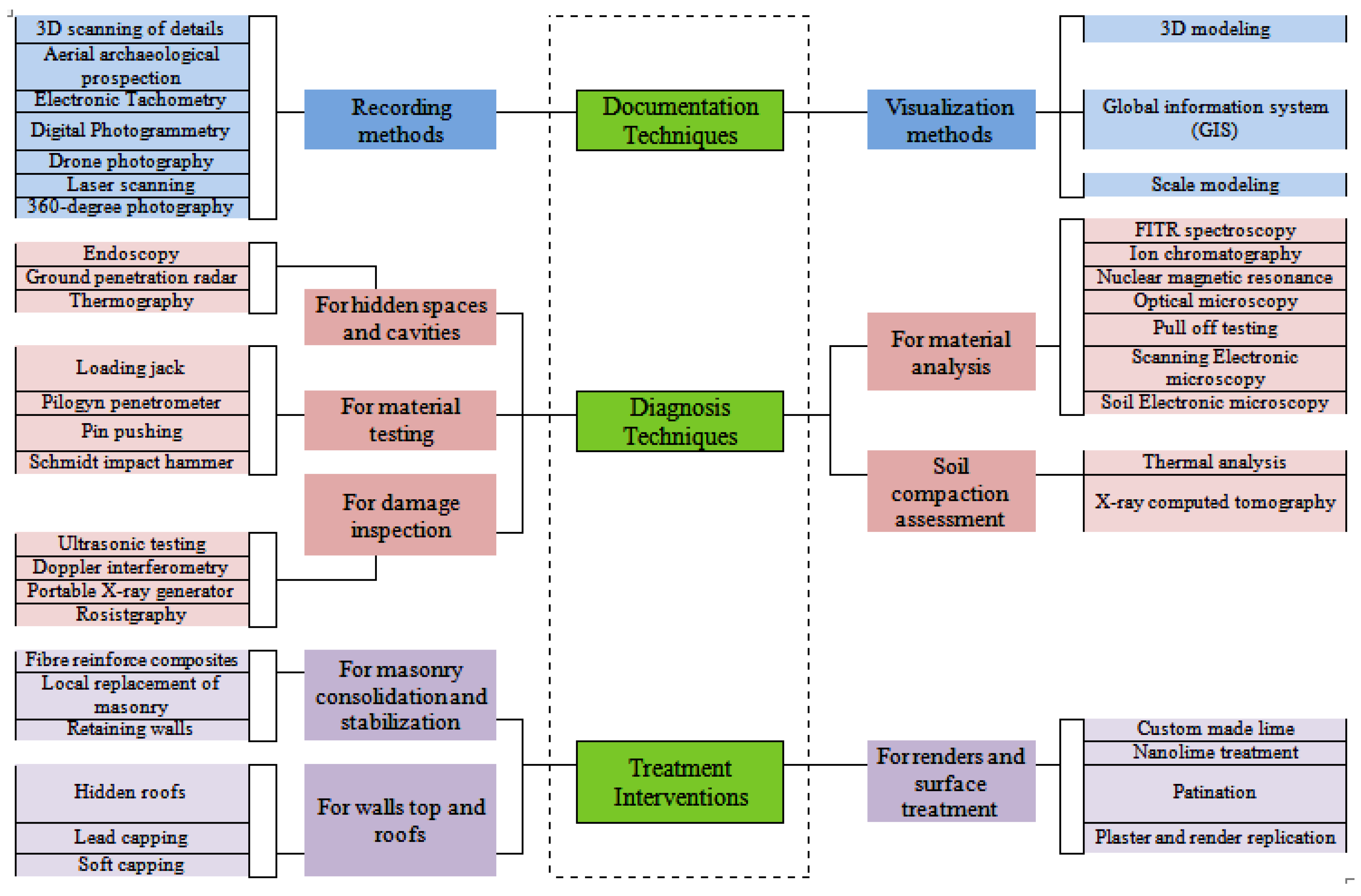

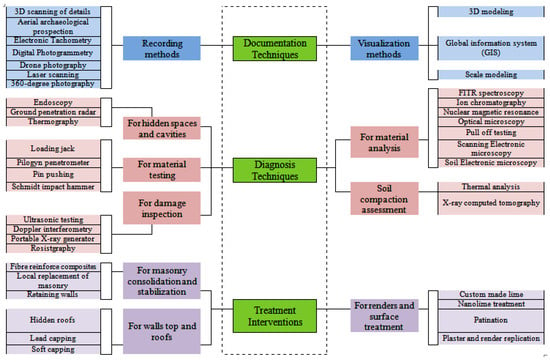

Figure 4 shows the details of different techniques required for the conservation of architectural heritage.

Figure 4.

Innovative methodologies in preservation and restoration. Adapted from [7,21].

1.2.1. Documentation Techniques

Documentation techniques include surveying heritage buildings and recording the elements required for visualization of the reflected subject to be handed to the conservationist. Such documentation methods entail observation, recording, and unveiling the data [7]. Documentation is, simply put, recording and visualization methods [22] (see Figure 4). Ref. [25] considered the image-based scheme as limited and purposely meant to capture and store only the photographic data. A combinative process, on the other hand, benefits from both image and non-image-based schemes, and, therefore, is a better option.

Furthermore, conservation processes require an understanding of the authenticity, value, and significance attached to the emotional as well as the physical characteristics of the heritage entity [26]. Gathering information on the physical conditions such as the state of the materials is, therefore, essential; it also includes examining the microstructure, chemical constituents, and morphological characteristics of the built heritage [25].

1.2.2. Diagnostic Methods

A diagnostic method involves examining the recorded deficiency for further treatment of the deterioration and decay.

Research by [21,27] unveiled the integrated and multiple ideas in the diagnosis of a putrefied built structure. The use of a three-dimensional terrestrial laser scanner was applied to examine the classification, origin, development, and history of the stone utilized in the construction, an ultrasonic measurement verified the stone size to find out the elasto-mechanical strength. Infrared thermography was used to examine the temperature of the built heritage through its surface. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and optical microscopy (OM) were used to potentially reveal the porosity, type of stone, and existence of microbes. SEM and OM can differentiate materials, identify possible biodeteriogens, and demonstrate the space and surface allotment of possible biodeteriogens [19,24]. Material classification provides the possible type of stone applied in the construction, its pore size and grain size, all of which authenticate the exposure of heritage buildings to deterioration [27,28].

Non-invasive and non-destructive methods are used to perform diagnosis, as highlighted by [29]. They [29,30] also emphasized that these techniques do not destroy the underlying material, which makes them advantageous. The materials used in these methods include nitrocellulose membranes [31], adhesive tapes [32], and sterile scalpels [33].

A Raman spectrometer was primarily used in the previous conservation works, but often does not have the proper report for the treatment carried out. This makes it unique in its potential to recognize the conservation executed [34,35]. It is often selected for in situ analysis when finding out the organic and inorganic subject on a stone bedrock. X-ray diffraction verifies the structure of natural compounds and the nature of a crystalline compound as well [36]. Nevertheless, it is avoided in some cases because of its destructive nature [7].

Some novel molecular-based diagnostic methods adopted in cultural heritage preservation include omics: genomics and proteomics. Genomics provides information on microorganisms that live in deteriorated heritage, as well on the biodeteriogens living on the heritage site [32,37,38]. Ref. [39] emphasizes the application of this method as it illustrated the array of microbes on stone monuments surrounding the UNESCO world heritage site at the West Lake Cultural Landscape of Hangzhou, where cyanobacteria were discovered as the likely biodeteriogens. The use of proteomics before conservation work is of assistance since it recognizes organic binders applied in paintings on a heritage substance or earlier conservation treatments [40]. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer recognizes organic and inorganic materials (in some cases) while sodium dodecyl sulphate→polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS→PAGE) isolates and recognizes the specific protein available in the organic substance.

Conservation of architectural heritage begins with an appropriate examination of the building and structural components to establish the basis of the degradation and its extent alongside the proper conservation treatments to be applied [41,42]. The initial evaluation is through physical inspection, in which conservationists with architects assess the decay visually, without devices. Even though this is a necessary step, it does not provide specific information concerning the history or decomposition in progress, for this reason, the call for informative diagnostic tools and skills are essential.

Nevertheless, proteomics is the best technique due to its productive act on the conservation of painted built heritage in Nigeria, because of its novel recognition of organic binders applied in paintings on a heritage substance or earlier treatments’ interventions.

1.2.3. Treatment Interventions

There are many approaches to the restoration of the built heritage with treatment intervention methods [7]. Nanotechnology methods have been broadly utilized in the conservation of built heritage as consolidants [43], cleaning agents [18], and biocides [44]. The biocides were implanted in a tetraethyl oxysilane (TEOS), water-repellent consolidant, and/or siloxane-based substance; Estel 1100, SILO III, and TEOS are nanocomposite materials which consolidated the weathered stone [7]. Ref. [45] further noted that it builds up a copper polymer organo-composite that has bacteriostatic and antifungal actions that were discharged slowly for a certain time.

Biotechnology, in the context of the restoration of cultural heritage, has been popular for more than ten years [46] and also has been used in developed nations [47]; however, it is yet to be implemented in Nigeria [7]. The benefit of biorestoration over many traditional treatments lies in its harmlessness to professionals, its eco-friendliness, non-destructiveness, precision, and efficiency [48].

Hence, the advanced techniques in the conservation of cultural heritage include nanotechnology, bio-conservation (biotechnology), and laser technology, among others, which are used due to their efficiency, safety, and ecological nature.

2. Materials and Methods

Notably, the conception and techniques for the conservation of heritage buildings in Nigeria vary considerably. This allows for a better contextualization of the topic and thoughtful results.

Nigeria is a country located on the western coast of Africa with numerous kingdoms [1,49] and has more than 250 clannish groups with each ethnic relation having its different rich artistic outlook as well as cultural heritage [50]. It is divided into northern and southern regions with the Hausa Fulani, different, although culturally identical, co-existing in northern Nigeria [51].

Kano remained an ancient city and commercial hub in West Africa for more than four hundred years, which were dated back to the early “Hausa Habe dynasty” [52,53]. The diversity embedded in the configuration of the cities is characterized by individuals of various ancestry or families of different origins, classes, and occupations coupled with the centrality of the township as shown by their grouping together for protection, trade, and religion within a bureaucracy led by an Emir or King [54,55,56]. At present, it remains the heartland of “Habe” cities, which comprise Kano itself, Jigawa, Katsina, Daura, and Zaria, as well as Gaya, to mention a few [2,17].

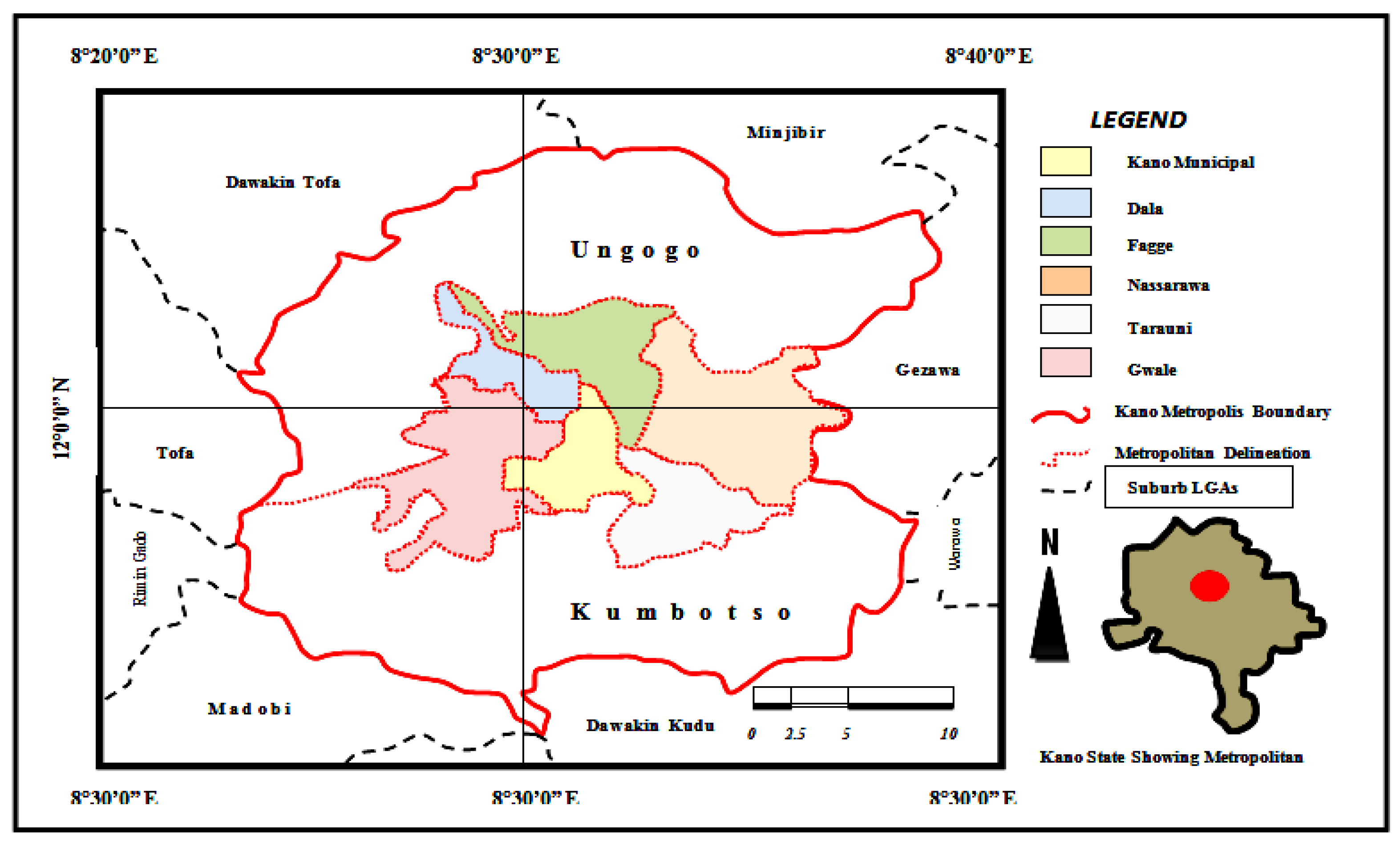

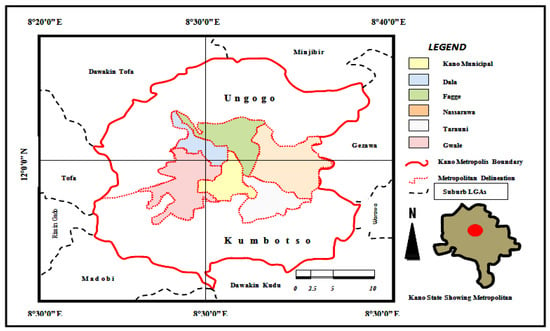

As showcased in Figure 5, the Kano metropolis is rationally located at the center of Kano state between latitudes 11°52′ N and 12°07′ N and longitudes 8°24′ E and 8°38′ E [14], serving as the major trading center of northern Nigeria, with a population of over 4 million, while Kano state has more than 10 million inhabitants [57,58].

Figure 5.

Kano metropolitan map. Source: [14].

The quick growth, rich cultural heritage, together with the political status of the city position of the Habe Kingdoms, are all factors that contributed to the establishment of “Birnin Kano” (Kano metropolis). In this regard, Kano’s urban area continues to be one of northern Nigeria’s and Africa’s biggest historical hubs. In light of this, metropolitan Kano is justified as a research interest location.

This study adopted a qualitative methodology. On the one hand, it utilises a descriptive approach to explain, examine, and interpret the prevailing practices, existing situations, attitudes, reasons, and on-going processes [59,60]. On the other hand, it makes use of spatial analysis methods, inventories/direct assessment of physical characteristics of the selected buildings, and focus group discussion (FGD) sessions with the custodians, prominent elderly persons, or ward heads (Mai Unguwa) from each of the selected buildings. It also includes a review of published documents (both printed and online) in the context of architectural heritage conservation and the Kano metropolis.

With the nature of the urban disposition of metropolitan Kano, several logical methods are used in the selection, sorting, and ordering. The research surveyed a total number of twenty-nine (29) buildings guided by the research scope. The metropolis in the study holds a good database of historical and cultural buildings from the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial eras. In this study we find it necessary to identify and survey these historical buildings on the basis of their value formation, processes, phenomena, and typology. The study purposively considers three buildings each from the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial eras. A physical evaluation through observation of the characteristics of the deterioration processes was carried out as a pilot survey to select the most deteriorated, prominent, and accessible structures for the study. A total of nine buildings, three from each period, were selected that best fit the criteria. For each of the nine selected buildings, a direct assessment of the physical features of the degradation processes and phenomena was conducted. A focus group discussion (FGD) was further conducted to validate the types of conservation techniques and interventions. This was structured with wide variables to collect viable data via voice recording. It entails building value-index, degradation, processes, phenomena, and typology of conservation techniques and interventions over a period of time.

Validation analysis is further employed. This is usually utilized in urban, architectural, and engineering research, being a descriptive and statistical classification process [61,62], including in the analysis of building functions, facilities, landscape characteristics, and elements of buildings [63]. Consequently, this study adopts revalidation analysis for the degradation hierarchical classification.

3. Results

During the field survey, a total of twenty-nine historic/monumental buildings were surveyed, as shown in Table 1; however, the study purposively considers three buildings each from the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial eras.

Table 1.

Surveyed historic/monumental buildings.

3.1. Description of Selected Pre-Colonial Buildings

As shown in Table 1, twelve historic buildings were surveyed. However, for purposive and convenient sampling, three buildings were later selected. They were all built with mud since ancient times, although have undergone some evolutionary changes.

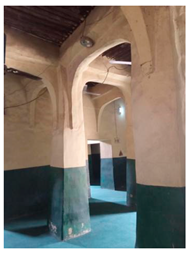

3.1.1. Dorayi Palace

Dorayi Palace, known as Dorayi mini palace, was established in the late 1800s by the Emir of Kano, Aliyu Babba (Sarki Alu) as the Emir’s rural resort and farms, later reconstructed as mini palace by the late Emir of Kano (1926 to 1953) Sarki Muhammadu Sunusi I. It is often visited by Emirs during Sallah Durbar (Hawan Dorayi) for territorial retreat, while the populace of the western precinct pays their respects to the Emir as they stay till mid-afternoon (see Table 2 for further description).

Table 2.

Description of the surveyed Dorayi Palace as a pre-colonial building.

It has undergone many restorations, the window openings were replaced with casement windows, most of the katanga/garu (fence wall) have been replaced with 225 mm sandcrete block walls, and the mud roof deck was covered (against rain and wind storms) with galvanized zinc and aluminum roofing sheet. The palace’s chamber flooring has been replaced with ceramic tiles. The building is endangered by storms, termites, cracks on the internal and external walls, floods, as well as other climatic elements.

3.1.2. Shatsari Arab Mosque

Shatsari Arab Mosque, also known as Masallacin Dandalin Turawa, was built earlier than the Kano Central Mosque as it was constructed in the early 1800s by Late Alhaji Bashir, also known as Audi, an Arab businessman who came to Kano for trading (see Table 3 for further description).

Table 3.

Description of the surveyed Shatsari Mosque as a pre-colonial building.

The most notable restoration of the building over the past few decades was that of the late Libyan president Muammar Al-Gaddafi. Thus, the building is endangered by cracks on the internal and external walls, floods, termites, as well as other climatic elements.

3.1.3. Gidan Shattima

Gidan Shattima is said to have been founded in the late 1490s by the Emir of Kano, Sarki Muhammadu Rumfa, as a prototype of the attempted 1000 housing, alongside the present residence occupied by Galadiman Kano (Gidan Galadima at Galadanci), Madakin Kano (Gidan Madaki). Shattima Shekarau (Barebari clan) is said to have been the aristocrat charged with the supervisory duty of the house when it was later converted to a lodge; he received and provided accommodation to the European and Asian envoys whenever they came for an official purpose to see the Emir. The title Shattiman Kano came into existence after the death of Shattima Shekarau (see Table 4 for further description).

Table 4.

Description of the surveyed Gidan Shattima as a pre-colonial building.

Hence, the new Kano Emirates necessitated the upgrade as the re-established structure entails an arcade, offices, private lodges, a council chamber, offices of the Emirs, and a colonnade. The building was under rehabilitation till the end of the survey, although has been put to use in recent times.

3.2. Description of Selected Colonial Buildings

As illustrated in Table 1, twelve monumental buildings were surveyed. Yet, for purposive and convenient sampling, three buildings were later selected. They were constructed with various building materials ranging from mud bricks, stone/rubble, masonry walls, and prefabricated concrete.

3.2.1. Masaka Textile Mill

Masaka textile mill, later known as Uba Lida Textiles Company, the first textile factory in Kano, commenced erection on 19 January 1950. It was built by a collection of indigenous businessmen identified as the Kano Citizen’s Trading Company (KCTC), aided by the Northern Nigeria Development Corporation, which was established in 1956 (see Table 5 for further description).

Table 5.

Description of the surveyed Masaka textile mill as a colonial building.

The mill was constructed with masonry walls, sandcrete blocks and granolithic floor, coconut lumber, steel casement doors and windows, and galvanized zinc roofing sheets. Subsequently, the old galvanized zinc roofing sheet, damaged by a wind storm, was replaced with the same material of different quality. Some broken glass windows, ceiling components, doors, precast concrete handrails, and the steel overhang at the material store were not restored. Consequently, the building is suffering from wind storms and the action of other climatic elements.

3.2.2. Kofar Kudu Sharia Court

Kofar Kudu Sharia Court, also termed Yan Awaki Sharia Court, was the first allotted Sharia Court building in the city. As a designated Sharia Court, it commenced proceedings in the 1930s under the judiciary of the defunct northern Nigeria while it serves as an archive to all Sharia Courts in the old Kano districts (see Table 6 for further description).

Table 6.

Description of the surveyed Kofar Kudu sharia court as a colonial building.

The structure was constructed with masonry walls, sandcrete blocks and terrazzo floors, steel casement doors and windows, and galvanized zinc roofing sheets. Furthermore, the old galvanized zinc roofing sheets damaged by the wind storm were replaced with the same material but of different quality. Some window broken glass, ceiling components, doors, precast concrete handrails and steel overhang at the material store were not restored. Consequently, the building is threatened by dilapidation of ceiling components, roof leakages, moisture movement, microbial attacks, and other climate elements.

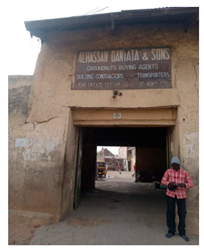

3.2.3. Gidan Alhassan Dantata

Gidan Alhassan Dantata (Alhassan Dantata House) was constructed in the late 18th century and happens to have been the first residential building in Kano city covered with galvanized zinc roofing sheets. Alhassan Dantata became the wealthiest businessman in Kano by 1922 and was later confirmed as the richest man in West Africa after his death in January 1955 (see Table 7 for further description).

Table 7.

Description of the surveyed Gidan Alhassan Dantata as a colonial building.

At the time of the survey, none of his family relatives reside in the compound, as it is only occupied by his childrens’ and grandchildren’s employees. The house was constructed with brickwork walls, sandcrete plaster and floor screed, coconut lumber, wooden doors and windows, local steel windows, and galvanized zinc roofing sheets. Hence, the building is endangered by severe cracks in the walls, storms, as well as other climatic elements.

3.3. Description of Selected Post-Colonial Buildings

As illustrated in Table 1, five contemporary buildings were surveyed. Yet, for purposive and convenient sampling, three buildings were later selected. They were constructed with various building materials including facing blocks, sandcrete plaster, masonry wall, and prefabricated concrete.

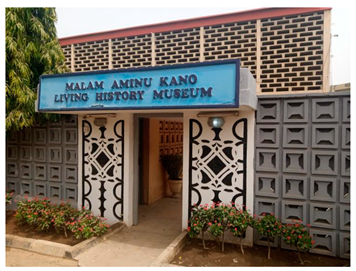

3.3.1. Mambayya House

Mambayya House, also known as Gidan Malam (Malam Aminu Kano’s residence), was founded in 1973 and was taken over during the military administration by the Federal Republic of Nigeria in 1989 alongside the adjoining houses which were paid-out, or rather compensated for, to establish the Center for Democratic Studies (CDS) (see Table 8 for further description).

Table 8.

Description of the Surveyed Mambayya House as a post-colonial building.

The building, however, is threatened by moisture movement of the external wall, minor cracks on the external/fence walls, and other climatic elements.

3.3.2. Gidan Haruna Kasim Fagge

Gidan Haruna Kasim was founded by the late Alhaji Haruna Kasim, an indigenous businessman, and constructed in the early 1960s by Alhassan Dantata and Sons at the sum of ten thousand pounds (see Table 9 for further description).

Table 9.

Description of the surveyed Gidan Haruna Kasim as a post-colonial building.

Nevertheless, the building is suffering from moisture movement, along with other climatic elements.

3.3.3. Gidan Ado Bayero

Gidan Ado Bayero was founded by the first civilian governor, Alhaji Muhammadu Abubakar Rimi in the early 1980s. Although abandoned for more than a decade, it was completed on 14 September 2001 and commissioned on 24 May 2003 as the KSIP headquarters building (see Table 10 for further description).

Table 10.

Description of the surveyed Gidan Ado Bayero as a post-colonial building.

Some of the broken tiles and gypsum ceilings were replaced with the same materials of different patterns or colors. However, the building is suffering from moisture movement, and other climatic elements.

4. Discussion

Conservation interventions of the surveyed buildings were performed individually or jointly by various stakeholders that include individuals, agencies, local and international groups, and the state and federal governments. These stakeholders include local communities such as the shatsari mosque committee, government institutes (such as Yusuf Maitama Sule University, Bayero University Kano, and the Kano State History and Culture Bureau), and traditional monarchs.

4.1. Pre-Colonial Buildings Conservation Interventions

None of the buildings have been declared a national monument nor are they on the list of buildings yet to be declared. The three buildings surveyed have undergone thorough evolutionary processes considering their age, local skills, and the building materials used for their construction subsequently.

- i

- Dorayi mini palace is an example of Hausa traditional architecture built in the late 1800s and remains among the rare palace architecture in northern Nigeria. The walls and roof of the palace are enriched with colorful motifs and engraving work.

- ii

- Shatsari Arab Mosque is also an example of Hausa traditional architecture and remains one of the most aged religious buildings in northern Nigeria as it was founded in the early 1800s. Shatsari Arab Mosque serves as a symbolic monument of socio-economic development in Hausaland during the early trans-Saharan trade.

- iii

- Gidan Shattima is another example of Hausa traditional architecture that has undergone rigorous evolutionary changes that have transformed it into contemporary architecture. The transformation started from pre-colonial building to colonial and it has now been rehabilitated as a post-colonial building. The reconstruction is ongoing at the time of the survey and none of the 15th-century materials have been restored yet; it serves as a source of knowledge about architectural revivalism in Hausaland. The building serves as a historic monument to the socio-political and economic development of the Kanawa and northern region (before and after Nigeria’s first republic).

Conservation interventions were conducted by local communities, government institutes (such as the Kano State History and Culture Bureau), traditional rulers, the Kano state government, and international individuals and communities. Despite all the interventions, the application of inventive techniques is deficient in the choice of conservation management schemes alongside inconsistent funding.

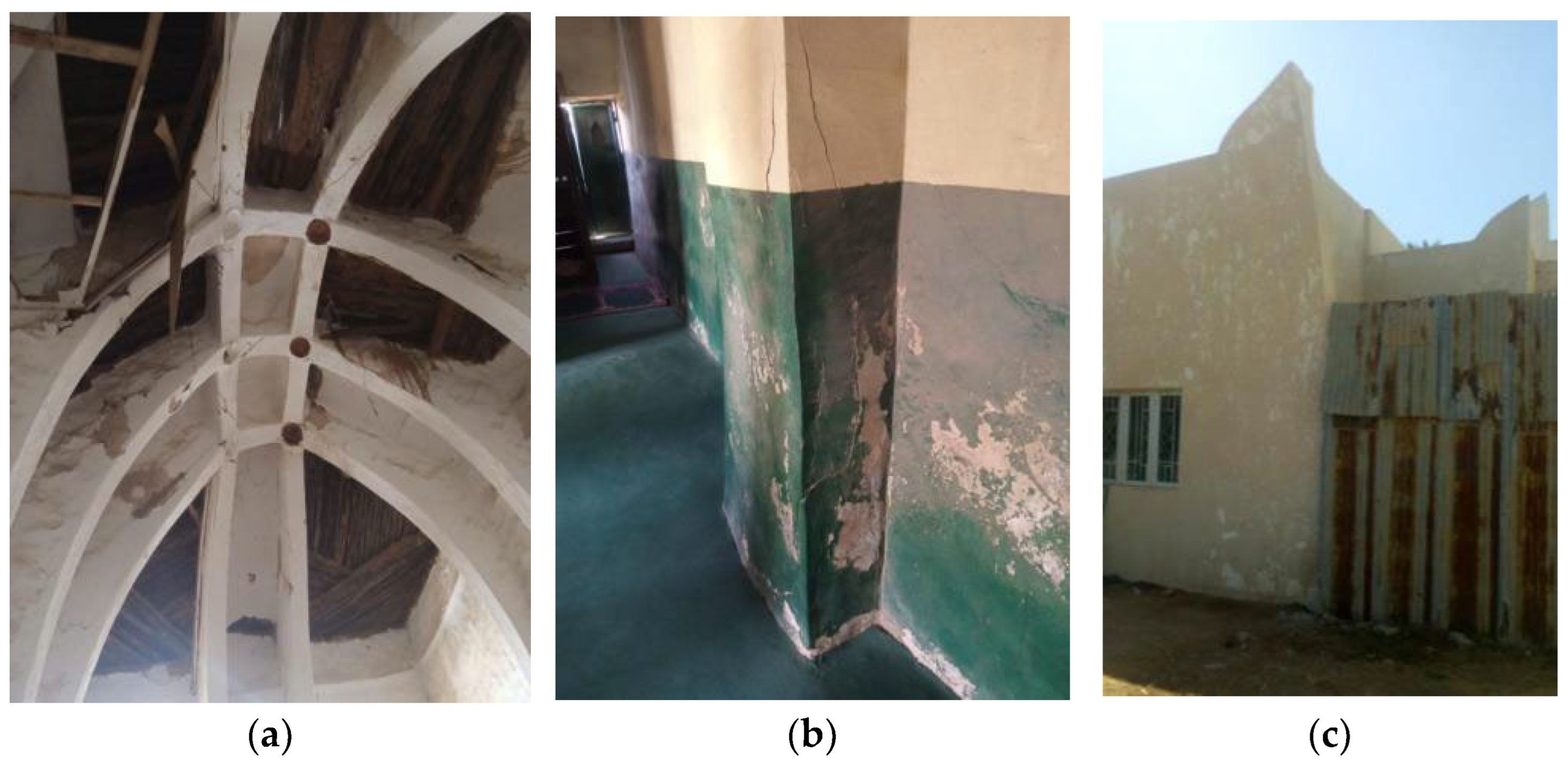

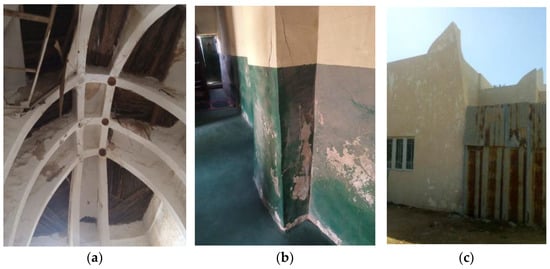

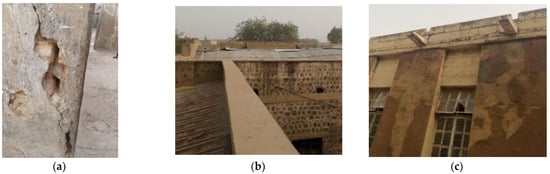

The palace and mosque were constructed with tubali (local mud bricks), marmara (stones), azara (timber), sandcrete plaster, and steel. The structure, though, is vulnerable to termites and insect attacks, windstorms, floods, along with other climatic aspects, while some causes of dilapidation include salt, microbes, and birds (see Figure 6). Moreover, judging by the evolutionary process of Gidan Shattima, the conservation intervention by the Kano state ministry of works and infrastructures from 2014 to 2021 used diverse techniques for documentation with the treatment of different varieties over time. This shows that the deterioration and defects over the period are associated with organic and inorganic decay resulting from changes in anthropogenic activities and climatic circumstances. Hence, what necessitated the reconstruction is the creation of the new emirates.

Figure 6.

Observed defects on the three pre-colonial buildings. Source: authors’ fieldwork, 2022; (a) Termite attack on azara roof at Dorayi Palace; (b) Major cracks and moisture at Shatsari Mosque; (c) Moisture effects on Gidan Shattima.

The deficiencies examined in the two buildings were documented using physical observation and digital photography but none of the deficiencies were diagnosed to recognize the causes and extent of the defects. Furthermore, heritage conservationists were not involved when addressing the defects through processes for removal, restoration, and reconstruction although inventive local treatments were used in mending cracked walls in Dorayi Palace; the use of milled locust bean pods forms an important component of plaster mortar which enhances the strength and water repellent behavior (see Table 11).

Table 11.

Conservation intervention of the three selected pre-colonial buildings in Kano metropolis, Nigeria.

4.2. Colonial Buildings

None of the buildings have been declared as a national monument nor are they in the list of buildings yet to be declared. The three buildings surveyed have undergone thorough evolutionary processes considering their age, local skills, and the building materials used for their construction subsequently.

- i

- Masaka textile mill is an example of colonial architecture built in late 1956 and remains among the rare industrial developments in northern Nigeria. Masaka textile serves as a symbolic monument of the socio-political and economic development of Nigeria during the Nigerian civil war. It not only produced uniforms worn by the heroes but served or rather produced clothing for many unions, schools, governmental, and non- governmental institutes before its closure.

- ii

- Kofar Kudu sharia court is a model of colonial architecture and remains among the rare buildings in Kano municipality as an aged judicial building in northern Nigeria, as it was founded in 1928. It serves as a symbolic monument of the legal system in northern Nigeria before and after colonial supremacy.

- iii

- Gidan Alhassan Dantata is an example of trado-modern architecture of its time; while it was built from modern materials, it adopted Hausa traditional architecture typology. It remains among the rare mixed-used dwellings within Kano city as well being the first personality building in northern Nigeria that imported western construction materials and skills. It was founded in the late 18th century and serves as a symbolic monument of the socio-economic development in Hausaland and Nigeria during the trans-Saharan business and Nigerian commodities trade.

Conservation interventions were conducted by the present occupants, property owners, government institutes (such as the Kano state judicial council), and the Kano state government. Despite all the interventions, the use of inventive techniques is deficient in the choice of conservation execution plans alongside poor funding.

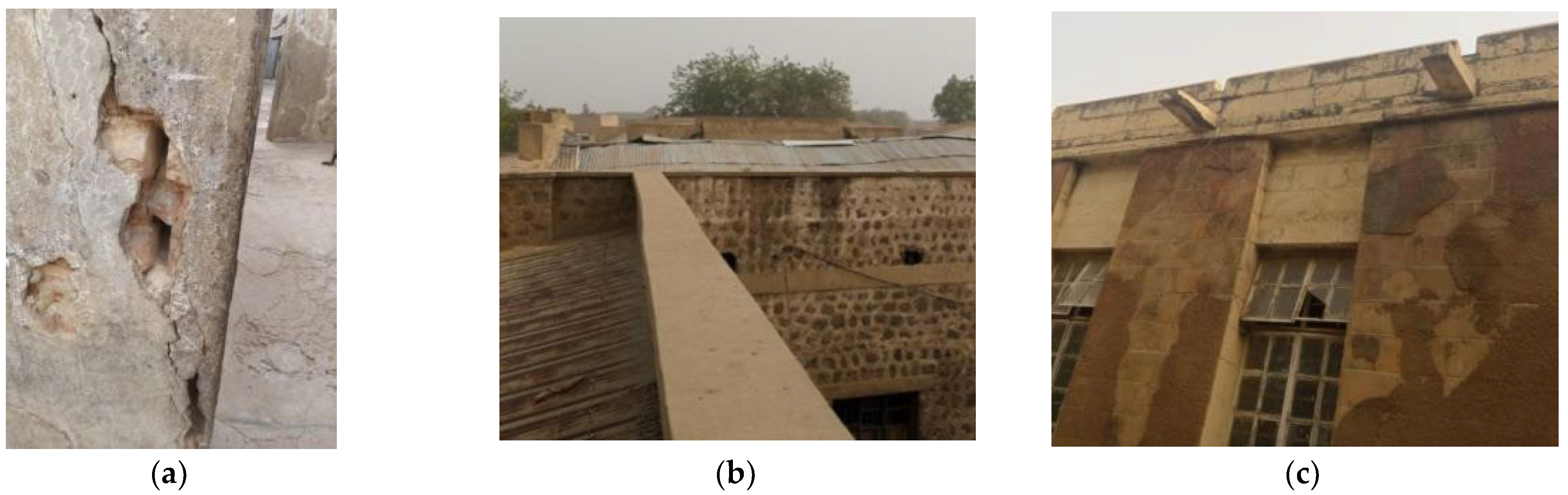

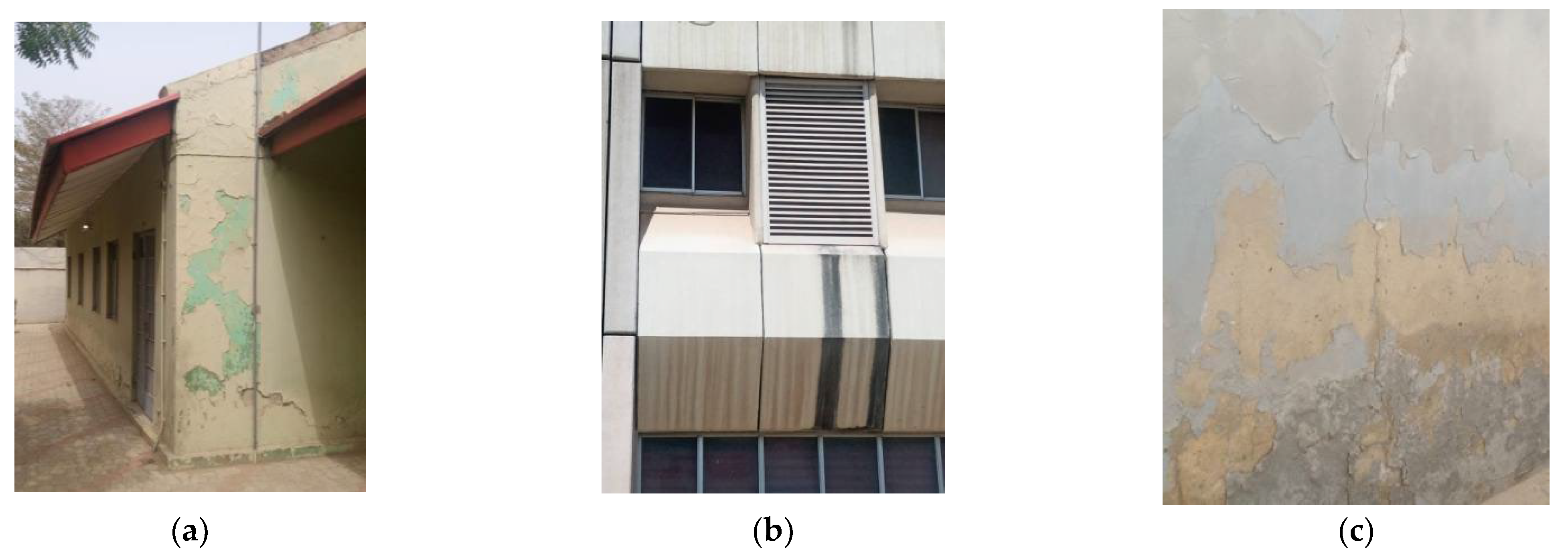

The three buildings were constructed with masonry walls, mud/adobe bricks, sandcrete plaster, and galvanized zinc roofing sheets. The buildings remain strong, although have undergone a series of restorations. However, they are exposed to climatic elements, termites, storms, and floods. Other reasons for dilapidation include fire, salt, and microbes, as well as insects (See Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Observed defects in the three colonial buildings. Source: authors’ fieldwork, 2022; (a) Major cracks at Alhassan Dantata; (b); Damaged and blown-off roofing sheets at the warehouses; (c) Salt effect/microbial growth on external walls of the courtroom.

The deficiencies examined in the two buildings were documented using physical observation and digital photography but none of the deficiencies were diagnosed to recognize the causes and extent of the defects. Furthermore, heritage conservationists were not involved when addressing the deterioration through processes for removal, restoration, and reconstruction (see Table 12).

Table 12.

Conservation intervention of the three selected colonial buildings in Kano metropolis, Nigeria.

4.3. Post-Colonial Buildings

None of the buildings have been declared as national monuments nor are they on the list of buildings yet to be declared, although, Mambayya House was taken over by the federal government of Nigeria in 1989 and at present is allotted as the Aminu Kano Center for Democratic Studies. The three buildings surveyed have undergone inclusive evolutionary processes considering the skills and building materials used for their construction subsequently.

- i

- Mambayya House particularly Malam Aminu Kano’s Living History Museum is an example of post-colonial architecture, built in 1973, and remains among the rare residential structures of its time. The museum serves as a symbolic monument of the socio-political and cultural development of Nigeria’s first republic and beyond. Hence, it serves as a resource of information on democratic studies in Nigeria.

- ii

- Gidan Haruna Kasim is a replica of post-colonial architecture and remains among the rare residential buildings of its time in the metropolis. It serves as a symbolic monument of prefabricated residential structures in northern Nigeria. Despite importing foreign materials and skills, it adopts traditional architectural typology. Consequently, it is a source of knowledge in contemporary architecture.

- iii

- Gidan Ado Bayero is an example of post-colonial architecture and remains among the rare high-rise buildings in Kano. It was founded in the early 1980s and serves as a symbolic monument of the socio-political and economic development in northern Nigeria during the second republic and beyond.

Conservation interventions were conducted by the present occupants, government institutes (such as the Kano state judicial council, Yusuf Maitama Sule University Kano), and the Kano state government. Despite all the interventions, the use of inventive techniques is deficient in the choice of conservation execution plans alongside inadequate funding.

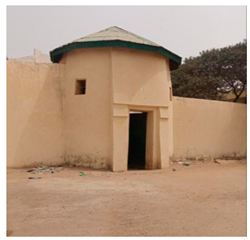

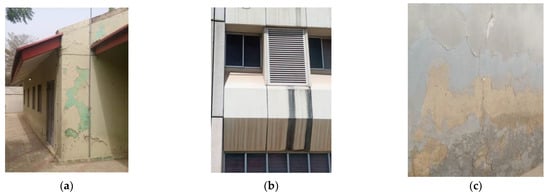

The three buildings were constructed with masonry walls, mud bricks, sandcrete plaster, and galvanized zinc roofing sheets. The buildings remain strong, although have undergone a series of restorations. However, they are exposed to climatic elements, storms, and floods. Other causes of damage include salt, surface corrosion, and microbes (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Observed defects in the three post-colonial buildings. Source: authors’ fieldwork, 2022; (a) Flaking effects at MAK History Museum; (b) Surface rust on the external walls at Gidan Ado Bayero; (c) Paint flake, salt/moisture effect on the external walls at Gidan Haruna Kasim.

The deficiencies examined in the two buildings were documented using physical observation and digital photography but none of the deficiencies were diagnosed to recognize the causes and extent of the defects. Furthermore, heritage conservationists were not involved when treating the decay through processes for removal, restoration, and reconstruction (see Table 13).

Table 13.

Conservation intervention of the three selected post-colonial buildings in Kano metropolis, Nigeria.

4.4. Results Summary

From the study it is seen that the three pre-colonial buildings went through rigorous development. Dorayi Palace and Shatsari Mosque maintain their original structures and functions, meanwhile their conservation sequence entails renovation and restoration, and the degradation remains active. Whereas Gidan Shattima developed episodically (from a pre-colonial structure to colonial and now a contemporary building) which led to changes in its purpose and it being upgraded. For the three colonial buildings, their conservation processes depict preservation to avert continuity of deterioration but no attempt was made to restore them to their original forms. Then, for the three post-colonial buildings, Mambayya House (Malam Aminu Kano Living Historic Museum in particular) has been outstanding; proper funds were mobilized and it retains its original form through the conservation, entailing renovation and restoration. Gidan Haruna Kasim is in a good state, although it has undergone some upgrades due to inheritance yet its progression entails renovation and retrofit. The contemporary building, Gidan Ado Bayero, which took about 20 years to complete, has kept its form but has undergone a change in purpose and a few upgrades. The structure was put to use years after completion and also experienced renovation, restoration, and retrofit. Table 14 shows the evolutionary processes of these buildings.

Table 14.

Evolutionary processes of the analyzed buildings.

The study reveals that deterioration occurs due to decaying plaster and paint, moist walls, distorted openings, sagging roofs, wall cracks, roof leakages, exit spouts, stains, and corrosion. Other factors include microbes and termite attack, inappropriate use and negligence, civilization, and inappropriate funding. The authors noted zero implementation of diagnosis methods and conservation was also performed to avert the amount of decay; documentation methods and treatment interventions were the key conservation approach applied.

The study also noted the potential benefits of local treatment as evidenced in the intervention of the Dorayi Palace segment; the use of makuba (milled locust bean pod) to stabilize the geotechnical performance (liberated compressive strength, permeability, shear force limit, and swelling ability) of tubali (local mud bricks) to improve its potency. This milled locust bean pod is also mixed with laso mortar to enhance the waterproofing behavior of the local plaster efficiently employed in wall rendering.

5. Conclusions

Contemporary methods of conservation are presented in this study. Given the inconsistency that we see in some of the built heritage alongside the degradable materials and the restoration techniques employed, this will simply lead to non-implementation of diagnostic techniques and the efficacy of our local treatment intervention as unreliable.

Following the study of metropolitan Kano in the context of conservation practice, this research has accomplished its aim. There is the need for the use of innovative methodologies in the conservation of architectural heritage in the municipality; achieving this will strengthen the preservation disposition of the heritage buildings. It can also serve as a principle that will guide infrastructure and building development in the metropolis. Built heritage over time has been meant to increase visits to the attractive sites which generate a lot of income for the host locality. So, conservation and restoration will facilitate safeguarding of the cultural and local bequest. It will also help the current and upcoming generations have a sense of identity and history. Consequently, for the admiration and patronage of the present and future generations, the following recommendations are offered:

- i

- Student architects should be prepared to acquire the basic knowledge of architectural heritage conservation techniques. Furthermore, new generations of architects must gain knowledge of the contemporary methodologies for the conservation of built heritage.

- ii

- The heritage assets of Kano, as well as Nigeria, calls for guiding principles and implementation. This shall spell out in detail the preservation schedules and conservation management plans.

- iii

- As in other countries, such as China and Italy, rigorous penalties should be forced and authorized on violators of the heritage conservation conducts and principles.

- iv

- As in many cities, and countries, especially ancient or historic metropolises, the surveyed buildings could, therefore, be selected by the government (local, state and national) through concerned authority for conservation and restoration. In such a regard, the interventions should be guided by historians, architects, and conservationists (care specialists, technicians, scientists, educators, and administrators).

- v

- Funds ought to be appropriated and mobilized for the restoration of deteriorating assets, whereas attempts ought to be made to pronounce some of the surveyed buildings as national monuments and once this is achieved, immediate and proper funding should be put in place.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.A.Y., A.A. and A.M.U.; Methodology, D.A.Y., A.A., J.J., J.U.H. and A.A.Y.; Software, S.Z.; Validation, A.A., J.U.H. and A.T.Z.; Formal analysis, D.A.Y., A.A., J.Z., A.M.U. and A.A.Y.; Investigation, D.A.Y., A.M.U. and M.S.G.; Resources, J.Z., M.S.G., S.Z., J.J. and A.T.Z.; Data curation, M.S.G. and J.U.H.; Writing—original draft, D.A.Y.; Writing—review & editing, D.A.Y., A.A. and J.Z.; Visualization, J.J. and A.T.Z.; Supervision, A.A., J.Z. and J.J.; Project administration, D.A.Y., A.M.U., S.Z. and A.A.Y.; Funding acquisition, D.A.Y., J.Z., A.M.U., M.S.G., J.U.H., A.T.Z. and A.A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, it remain available only on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully appreciate the support from Director Research Fellow, Mumbaiyya House alongside other building custodians for granting permission to access the selected buildings. We also thank Mal. Sani Umaru Mai-Zaure, Alh. Idris Dankaka, Abubakar Fagge, Nafiu Isyaku, Sani Ali, Garba Sani Garba and Sani Isah Sorondinki for their services as Language/drawings interpreters and photography assistance. All supplementary data and imagery sources are appropriately cited.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kabir Umar, G.; Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Usman, A.M. The practice of Hausa traditional architecture: Towards conservation and restoration of spatial morphology and techniques. Sci. Afr. 2019, 5, e00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A. SOCIO—Cultural rejuvenation: A quest for architectural contribution in kano cultural. Int. J. Adv. Acad. Res. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2019, 5, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Akinbamijo, O.B.; Alakinde, M.K. Nigerian Heritage and Conservation Landuses; Challenges and Promises. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Murzyn, M. Practical Aspects of Cultural Heritage. HERMES. 2008. Available online: www.swkk.de/hermes/research/Buchbeitraege/HERMES/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Cullingworth, B.; Nadin, V. Town and Country Planning in the UK; Routeledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- NCMM. Declared and Proposed National Monuments. 2019. Available online: http://ncmm.gov.ng/declared/ (accessed on 14 June 2022).

- Okpalanozie, O.E.; Adetunji, O. Architectural Heritage Conservation in Nigeria: The Need for Innovative Techniques. Heritage 2021, 4, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinkunmi, O.J. Conservation of traditional earth building in Nigeria: Case study of Origbo in Ife-North, Osun State. Int. J. Afr. Soc. Cult. Tradit. 2016, 4, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kigadye, F.S. Architectural Conservation in Rapidly Urbanising Cities: The Case of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Cah. Afr. Est East Afr. Rev. 2014, 49, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterflinger, K.; Piñar, G. Microbial deterioration of cultural heritage and works of art—Tilting at windmills. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 9637–9646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, A.; Bappah, B.A. Conservation of kano ancient city wall and gates: Problems and prospects in Nigeria. J. Environ. Issues Agric. Dev. Ctries. 2011, 3, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Barau, A.S. Heritage Landscapes and Challenges of Climate Change: An Example of Kano City, Nigeria. In Proceedings of the Urban Heritage Conference, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 23–28 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Iliyasu, I.I. Challenges of preservation of cultural landscapes in traditional cities: Case study of kano ancient city. In Proceedings of the International Council for Reseach and Innovation in Building and Construction (CIB), Lagos, Nigeria, 28 January 2014; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Zhu, J.; Nashe, S.A.; Usman, A.M.; Sagir, A.; Yukubu, A.; Hamma, A.S.; Alfa, N.S.; Ahmed, A. A Typology for Urban Landscape Progression: Toward a Sustainable Planning Mechanism in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamu, H.S. An Analysis of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Kano, Nigeria. Master’s Thesis, North East University, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention concerning the protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage-being World Heritage. In Proceedings of the General Conference, 17th Session, Paris, France, 17 October–21 November 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Zhu, J.; Saleh-Bala, M.; Yakubu, A.; Nashe, A.S. Evolutionary trends in landscape of Hausa Open spaces: The key enablers of “Habe” cities planning mythology. J. Reg. City Plan. 2023, 34, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kapridaki, C.; Verganelaki, A.; Dimitriadou, P.; Maravelaki-Kalaitzaki, P. Conservation of Monuments by a Three-Layered Compatible Treatment of TEOS-Nano-Calcium Oxalate Consolidant and TEOS-PDMS-TiO2 Hydrophobic/Photoactive Hybrid Nanomaterials. Materials 2018, 11, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moropoulou, A.; Zendri, E.; Ortiz, P.; Delegou, E.T.; Ntoutsi, I.; Balliana, E.; Becerra, J.; Ortiz, R. Scanning Microscopy Techniques as an Assessment Tool of Materials and Interventions for the Protection of Built Cultural Heritage. Scanning 2019, 2019, 5376214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Sagir, A.; Yusuf, A.A.; Yakubu, A.; Zakari, A.T.; Usman, A.M.; Nashe, A.S.; Hamma, A.S. A Review of Conceptual Design and Self Health Monitoring Program in a Vertical City: A Case of Burj Khalifa, U.A.E. Buildings 2023, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICE. Report Assessing Innovative Restoration Techniques, Technologies and Materials Used in Conservation; Bláha, J., Novotný, J., Eds.; Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics of the Czech Academy of Sciences: Prague, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stylianidis, E.; Remondino, F. 3D Recording, Documentation and Management of Cultural Heritage; Whittles Publishing Dunbeath: Caithness, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.-C.; Hou, M.; Li, A. Recent progress in instrumental techniques for architectural heritage materials. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.; Moser, M.; Rampold, R.; Wu, C. Documentation of cultural heritage techniques, potentials and constraints. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 14th General Assembly, Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, 27–31 October 2003; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Adetunji, O.S.; Essien, C.; Owolabi, O.S. eDIRICA: Digitizing Cultural Heritage for Learning, Creativity, and Inclusiveness; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fais, S.; Casula, G.; Cuccuru, F.; Ligas, P.; Bianchi, M.G. An innovative methodology for the non-destructive diagnosis of architectural elements of ancient historical buildings. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadd, G.M.; Dyer, T.D. Bioprotection of the built environment and cultural heritage. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 1152–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzì, C.; De Leo, F.; Bruno, L.; Krakova, L.; Pangallo, D.; Albertano, P. How to control biodeterioration of cultural heritage: An integrated methodological approach for the diagnosis and treatment of affected monuments. Work. Art Conserv. Sci. Today 2010, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Okpalanozie, O.E.; Adebusoye, S.A.; Troiano, F.; Polo, A.; Cappitelli, F.; Ilori, M.O. Evaluating the microbiological risk to a contemporary Nigerian painting: Molecular and biodegradative studies. Intern. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2016, 114, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, O.; Sannino, L.; Palomba, S.; Anastasio, M.; Blaiotta, G.; Villani, F.; Moschetti, G. Heterotrophic microorganisms in deteriorated medieval wall paintings in southern Italian churches. Microbiol. Res. 2010, 165, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzı, C.; De Leo, F. Sampling with adhesive tape strips: An easy and rapid method to monitor microbial colonization on monument surfaces. J. Microbiol. Methods 2001, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo, A.; Gulotta, D.; Santo, N.; Di Benedetto, C.; Fascio, U.; Toniolo, L.; Villa, F.; Cappitelli, F. Importance of subaerial biofilms and airborne microflora in the deterioration of stonework: A molecular study. Biofouling 2012, 28, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vazquez-Calvo, C.; Martinez-Ramirez, S.; Alvarez de Buergo, M.; Fort, R. The use of portable Raman spectroscopy to identify conservation treatments applied to heritage stone. Spectrosc. Lett. 2012, 45, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadio, F.; Daher, C.; Bellot-Gurlet, L. Raman spectroscopy of cultural heritage materials: Overview of applications and new frontiers in instrumentation, sampling modalities, and data processing. Anal. Chem. C Herit. 2016, 374, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera, L.K.; Le Borgne, S.; Videla, H.A. Modern methods for materials characterization and surface analysis to study the effects of biodeterioration and weathering on buildings of cultural heritage. Intern. J. Arch. Herit. 2008, 3, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñar, G.; Dalnodar, D.; Voitl, C.; Reschreiter, H.; Sterflinger, K. Biodeterioration risk threatens the 3100 year old staircase of Hallstatt (Austria): Possible involvement of halophilic microorganisms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Ge, Q.; Ma, Q.; Li, Q.; Fu, T.; Hu, C.; Zhu, X.; Pan, J. Identification of fungal communities associated with the biodeterioration of waterlogged archeological wood in a Han dynasty tomb in China. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Ge, Q. Deterioration-associated microbiome of stone monuments: Structure, variation, and assembly. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02680-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wang, C. Proteomic identification of organic additives in the mortars of ancient Chinese wooden buildings. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridou, M.; Török, A. In situ investigation of stone heritage sites for conservation purposes: A case study of the Székesfehérvár Ruin Garden in Hungary. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2019, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulotta, D.; Toniolo, L. Conservation of the Built Heritage: Pilot Site Approach to Design a Sustainable Process. Heritage 2019, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelazzi, D.; Poggi, G.; Jaidar, Y.; Toccafondi, N.; Giorgi, R.; Baglioni, P. Hydroxide nanoparticles for cultural heritage: Consolidation and protection of wall paintings and carbonate materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 392, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, J.; Mateo, M.; Ortiz, P.; Nicolas, G.; Zadarenko, A.P. Evaluation of the applicability of nano-biocide treatments on limestones used in cultural heritage. Herit. J. C Herit. 2019, 38, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, N.; Torsi, L.; Ditaranto, N.; Tantillo, G.; Ghibelli, L.; Sabbatini, L.; Bleve-Zacheo, T.; DAlessio, M.; Zambonin, P.G.; Traversa, E. Copper nanoparticle/polymer composites with antifungal and bacteriostatic properties. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5255–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P. Applied microbiology and biotechnology in the conservation of stone cultural heritage materials. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 73, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, I.; Abbate, M.; Poli, A.; D’Orazio, L. Bio-cleaning of nitrate salt efflorescence on stone samples using extremophilic bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.; Vaccaro, C.; Leis, M. Biotechnology applied to historic stoneworks conservation: Testing the potential harmfulness of two biological biocides. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2016, 7, 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, D.A.; Ahmed, A.; Gajale, M.S.; Tijjani, Z.A.; Yakubu, K.I.; Yahaya, B.F. Sustainable infrastructure in tourism: Quest for user’s satisfier factors in porto golf resort, Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 1st Green Environment Energy and Building Science (GEEBS), Johor, Malaysia, 16–17 October 2017; pp. 306–312. [Google Scholar]

- CCP. Global Art and Heritage Law Series; Nigeria Report. 2020. Available online: www.culturalpropertylaw.org (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Danja, I.I.; Li, X.; Dalibi, S. Vernacular architecture of Northern Nigeria in the light of sustainability. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Environmental and Energy Engineering (IC3E 2017), Suzhou, China, 22–24 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Home, R. African Urban History, Place-Naming and Place-Making. Land Issues Urban Gov. Sub-Sahar. Afr. 2021, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquhart, A.W. Planned Urban Landscapes of Northern Nigeria: A Case Study of Zaria, 1st ed.; Ahmadu Bello University Press: Zaria, Nigeria, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Fisherman, A. The Spatial Growth and Residential Location of Kano; North-Western University: Evanston, IL, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U. Transformation in Hausa Traditional Architecture: A Case Study of Some Selected Parts of Kano Metropolis (1950–2004). Ph.D. Thesis, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, G.U.; Yusuf, D.A.; Mustapha, A. Theory and Design for the Contemporary Residential Buildings: A Case Study of Kano Metropolis, North-western part of Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Environ. Stud. Res. 2019, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- NPC. Nigerian Population Census Report; NPC: Abuja, Nigeria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Naibbi, A.I.; Umar, U.M. An appraisal of spatial distribution of solid waste disposal sites in Kano metropolis, Nigeria. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2017, 5, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagi, J.O. The Essentials of Research Methodology for Educators; University Press: Ibadan, Nigeria, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Muhammad, M. Rigour in Quantitative Research: Is Therea Panacea to It? Malays. J. Quant. Res. 2018, 4, 60–68. Available online: mymedr.afpm.org.my (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Djoki, V. Morphology and typology as a unique discourse of research. Serbian Archit. J. 2009, 1, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, B.W.; Stark, B.L.; Johnston, K.L.; Smith, M.E. Urban open spaces in historical perspective:A transdisciplinary typology and analysis. Urban Geogr. 2012, 33, 1089–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, T. Typology of religious spaces in the urban historical area of Lhasa, Tibet. Front. Archit. Res. 2017, 6, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liman, M.A. A Spatial Analysis of Industrial Growth and Decline in Kano Metropolis, Nigeria. Ph.D. Thesis, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).