A Comparison of the Project Management Methodologies PRINCE2 and PMBOK in Managing Repetitive Construction Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

- By keeping a consistent workforce throughout the project, there is no need for the frequent hiring and firing of labour. This reduces recruitment and training costs as well as the time required to onboard new workers. Skilled workers who are familiar with the project’s requirements can continue working on subsequent units, ensuring higher productivity and efficiency.

- In repetitive projects, skilled labour becomes more proficient and experienced over time. By retaining these skilled workers, their expertise and knowledge are preserved, leading to improved performance and quality. They become familiar with the project’s specific requirements and can work more efficiently, minimising errors and rework.

- In repetitive projects, the use of equipment can be optimised since the same activities are repeated. By maintaining work continuity, equipment idle time is minimised as well. Equipment can be kept operational and utilised efficiently without long periods of downtime between units. This reduces equipment-related costs and increases overall productivity.

- As workers become more experienced with the sequential activities involved in the project, they can perform their tasks more quickly and accurately. This leads to improved productivity and reduced construction time with each successive unit.

- Traditional scheduling tools are often rigid and not well-suited to adapt to the specific requirements of repetitive projects. These methods typically assume a high level of task variability, making it difficult to account for the repetitive nature of the project and the streamlined workflow it entails.

- Repetitive projects demand efficient resource allocation and management to maintain work continuity. However, traditional tools may not adequately account for the optimisation of crew allocation, equipment utilisation, and material flow. This can lead to suboptimal resource allocation, increased idle time, and reduced productivity.

- Traditional planning and scheduling techniques often overlook or underestimate the learning effect, resulting in unrealistic timelines and cost projections.

- While repetitive projects consist of recurring units, there may still be variations in design, site conditions, or other factors. Traditional tools may struggle to handle these variations effectively, leading to challenges in maintaining the desired work continuity and achieving accurate project planning.

2. Background

3. Research Object and Methodology

3.1. The Repetitive Construction Project

3.2. Project Management Model at Company X

3.3. Problems Related to Project Management at Company X

- Increased design quantities that were not paid for by the contract;

- The technological solutions for the project were only adjusted during the project;

- Lack of quality control of the project and poor quality of the anti-corrosion work carried out on certain steel structures;

- Failure to assign the responsible works managers to the relevant work operations;

- Works not foreseen in the project (installation of elevation aids, coating of steel structures before painting, and repeating the same operation twice);

- Delays in the agreed work schedule;

- Exceeded material resources.

3.4. Methodologies

3.4.1. The Analytical Quantitative Study

3.4.2. The Descriptive Qualitative Study

4. Results, Discussion and Recommendations

4.1. The Results of the Analytical Quantitative Study

4.2. Recommendations for Improvement of the Implemented Repetitive Project Management at Company X

4.3. The Results of a Descriptive Qualitative Study

4.4. Sustainability Aspect in Project Management for Future Studies

5. Conclusions

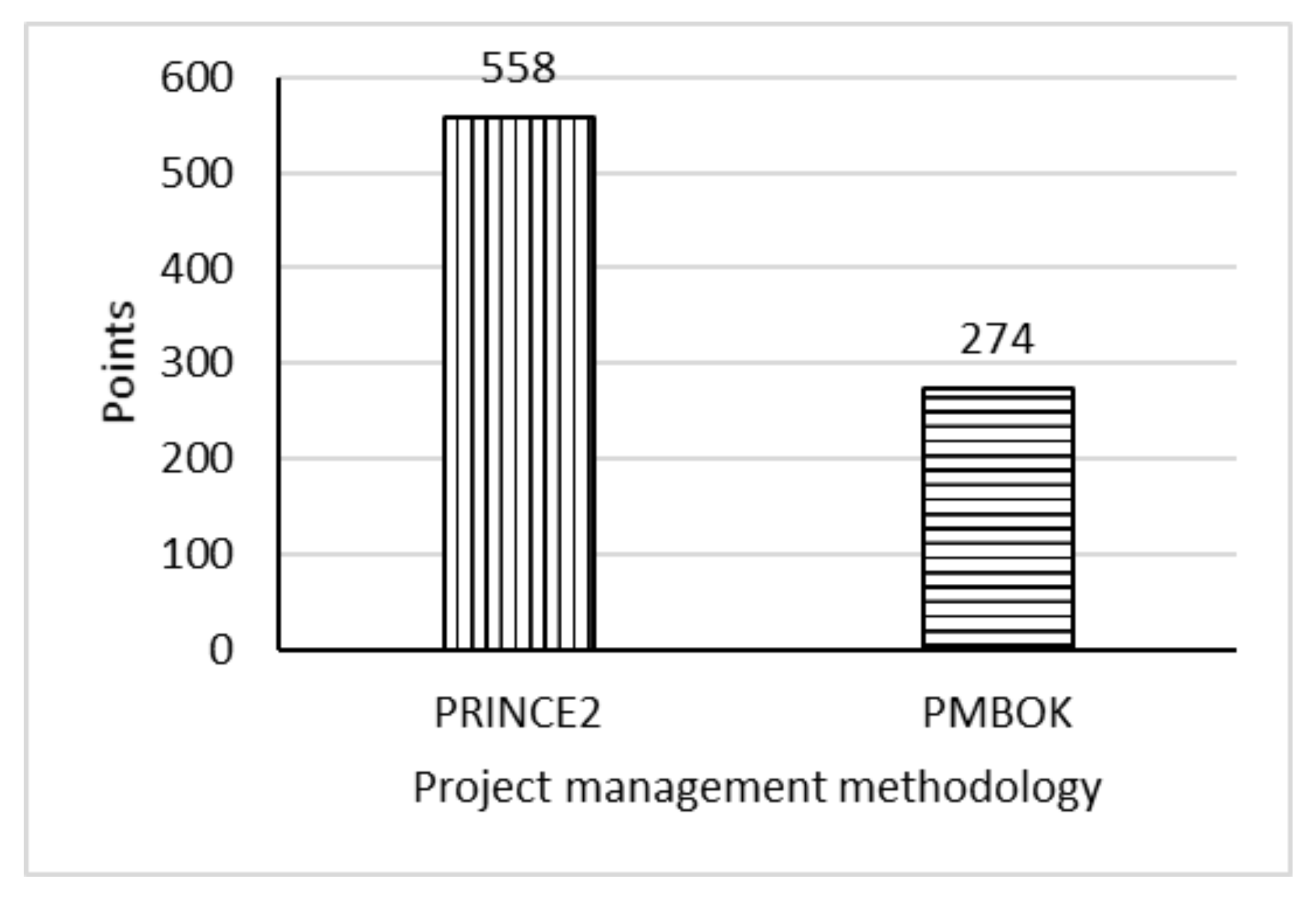

- The respondents identified the PRINCE2 project management approach as the most suitable for managing a repetitive construction project. According to the PRINCE2 project management methodology, a repetitive construction project would aim to provide as much information as possible to the project participants, to form a team and assign team leaders responsible for the phases, to establish a financial plan, a detailed timetable for the execution of the works, a quality control plan, and a plan of responsible persons, and to detail the technological sequencing of the works.

- The rational project management approach PRINCE2 should be integrated into the management of a project under study by applying the seven principles, seven themes, and seven processes. Regular project meetings with the project board should be organised, information and plans should be prepared according to the principles and themes of the project management methodology, the project manager should appoint the persons responsible for the execution of the work, quality, and material control, and the phases should be analysed responsibly with the project board. Before the works are handed over to the client, the project manager should carry out a quality control check, and the project board should control the communication between the project manager and the project team. In the project closure process, a learning-from-experience re-list should be completed, and the project results should be summarised and evaluated.

- The analysis of the anti-corrosion works project under the PRINCE2 methodology suggested the following areas for improvement: checking the project quantities and describing the technological process before the start of the project to eliminate the risks associated with project delays; periodic control of the quality of the intermediate, understanding of quality requirements, and ensuring that work is carried out to a high standard; clarifying responsibilities and tasks in the teams before the start of the project; breaking the project down into phases to increase control over certain operations (such as the first coat of paint); and preparing a detailed project plan to avoid unforeseen activities (such as an additional cover of the steel structures).

- The results of the qualitative research and the comparison of the participating companies revealed the following key similarities in project management: monitoring of relevant project progress indicators, project changes based on the project progress report, and the monitoring of project delays. Meanwhile, the main differences in project management among the surveyed companies were the project team size, the tools and methodologies used for project management, the project management philosophy, and the frequency of monitoring and discussing project progress.

- According to the studied companies, a successful project management should consist of a standardised implementation procedure, priority attention to the pre-project phase and responsiveness of project managers to problems and deviations, focus on the project, optimisation of mistakes and close communication with the customer, detailed and correct project decisions, timely communication of the project teams, and constant planning. Meanwhile, the reasons for project delays were mainly related to the lack of staff competence, inadequate project team structure, delays in materials and machinery supply, breakdowns, and inconsistencies in design solutions.

- Sustainable construction projects can minimise a project’s environmental impact, improve working conditions, and support the local economy by adopting green building practices, sustainable procurement practices, and waste reduction and management practices. By prioritising sustainability development in construction, project managers can shift their focus towards various aspects such as value creation, performance enhancement, efficiency improvement, business agility, project excellence, operational quality, paradigm shifts in thinking, flexibility, and more. Future studies should also be linked with sustainability in construction project management through energy-efficient building development. One of the things which sustainability in construction project management could adopt is green building practices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Zwainy, F.M.S.; Mhammed, I.A.; Raheem, S.H. Application Project Management Methodology in Construction Sector: Review. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. IJSER 2016, 7, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (Pmbok® Guide); Project Management Institute: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781628251845. [Google Scholar]

- PRINCE2 Training: Construction Industry. 2021. Available online: https://www.prince2training.co.uk/blog/prince2-for-the-construction-industry/ (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Knowledge Train®: PRINCE2® vs the PMBOK® Guide: A Comparison. 2021. Available online: https://www.knowledgetrain.co.uk/project-management/pmi/prince2-and-pmbok-guide-comparison (accessed on 10 December 2021).

- Murray, A.; Bennett, N.; Bentley, C. Managing Successful Projects with PRINCE2; TSO: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 0113310595. [Google Scholar]

- Jaziri, R.; El-Mahjoub, O.; Boussaffa, A. Proposition of a hybrid methodology of project management. Am. J. Eng. Res. AJER 2018, 7, 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Faraji, A.; Rashidi, M.; Perera, S.; Samali, B. Applicability-Compatibility Analysis of PMBOK Seventh Edition from the Perspective of the Construction Industry Distinctive Peculiarities. Buildings 2022, 12, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APM Group. PRINCE2 Case Study. PRINCE2 and PMI/PIMBOK®. A Combined Approach at Getronics; The APM Group Limited: Bucks, UK, 2002; Available online: https://silo.tips/download/contents-4-current-perceptions-of-relative-positioning-of-prince2-and-pmbok-appe (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Munns, A.K.; Bjeirmi, B.F. The role of project management in achieving project success. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 1996, 14, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, I.; Moselhi, O.; Zayed, T. Optimized acceleration of repetitive construction projects. Autom. Constr. 2014, 39, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, L.D.; Ohsato, A. A genetic algorithm-based method for scheduling repetitive construction projects. Autom. Constr 2009, 18, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhoucke, M. Work continuity constraints in project scheduling. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. ASCE 2006, 132, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.D.; Wong, W.C.M. New generation of planning structures. J Constr Eng Manag. ASCE 1993, 119, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reda, R.M. RPM: Repetitive project modelling. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. ASCE 1990, 116, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyari, K.; El-Rayes, K.; Asce, M. Optimal Planning and Scheduling for Repetitive Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2006, 22, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, N.; Muller, R.; Sankaran, S. The nature of organizational project management through the lens of integration. In Cambridge Handbook of Organizational Project Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 9–18. ISBN 978131666224-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, M.; Lavoie-Tremblay, M. Rethinking organizational design for managing multiple projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, D.; Nayak, S.; Damci, A. Effect of organizational culture on delay in construction. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershadi, M.; Jefferies, M.; Davis, P.; Mojtahedi, M. Achieving Sustainable Procurement in Construction Projects: The Pivotal Role of a Project Management Office. Constr. Econ. Build. 2021, 21, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, D.; Robinson, M.A. Concurrent delays in construction litigation. Cost Eng. 1995, 37, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry, M.; Hobbs, B.; Thuillier, D. A new framework for understading organisational project management through the PMO. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweis, G.; Sweis, R.; Abu Hammad, A.; Shboul, A. Delays in construction projects: The case of Jordan. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arditi, D.; Pattanakitchamroon, T. Selecting a delay analysis method in resolving construction claims. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2006, 24, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Shin, D. Delay analysis method using delay section. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2005, 131, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M.; Nielsen, Y.; Ozdemir, M. Fuzzy assessment model to estimate the probability of delay in Turkish construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 31, 04014055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamid, I. Effects of Design Quality on Delay in Residential Construction Projects. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2021, 1, 118–129. Available online: https://sace.ktu.lt/index.php/DAS/article/view/20531 (accessed on 10 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Cheung, S.O.; Arditi, D. Construction delay computation method. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudienė, N.; Banaitis, A.; Banaitienė, N.; Lopes, J. Development of a conceptual critical success factors model for construction projects: A case of Lithuania. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radujkovič, M.; Sjekavica, M. Project management success factors. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radujkovic, M.; Sjekavica, M. Development of a project management performance enhancement model by analysing risks, changes, and management. Građevinar 2017, 69, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Miller, D. Tackling design anew: Getting back to the heart of organizational theory. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, P.V.; Mahesh, G. Construction project performance areas for Indian construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2020, 22, 1443–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, A.; Ferreira, L.M.D.F. Development of delay mitigation measures in construction projects: A combined interpretative structural modeling and MICMAC analysis approach. Prod. Plan. Control 2023, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, S.; Lopes, E. Prince2 or PMBOK—A question of choice. Procedia Technol. 2013, 9, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasgozar, S.M.E.; Karimi, R.; Shirowzhan, S.; Mojtahedi, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, S.; McCarthy, D. Delay Causes and Emerging Digital Tools: A Novel Model of Delay Analysis, Including Integrated Project Delivery and PMBOK. Buildings 2019, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaeian, M.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Kabirifar, K.; Yazdani, M.; Shapouri, M. Selecting Appropriate Risk Response Strategies Considering Utility Function and Budget Constraints: A Case Study of a Construction Company in Iran. Buildings 2022, 12, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanzadeh, A.; Mahdinia, M.; Omidi Oskouei, A.; Jafarinia, E.; Zarei, E.; Sadeghi-Yarandi, M. Analyzing Health, Safety, and Environmental Risks of Construction Projects Using the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process: A Field Study Based on a Project Management Body of Knowledge. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8501-3:2006; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Visual Assessment of Surface Cleanliness Preparation Grades of Welds, Edges and other Areas with Surface Imperfections. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 8502-6:2020; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Tests for the Assessment of Surface Cleanliness—Part 6: Extraction of Water Soluble Contaminants for Analysis (Bresle Method). International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- ISO 8503-5:2017; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Surface Roughness Characteristics of Blast-Cleaned Steel Substrates—Part 5: Replica Tape Method for the Determination of the Surface Profile. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- SSPC-SP1:2015; Solvent Cleaning. The Society for Protective Coatings: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM D4940-15(2020); Standard Test Method for Conductimetric Analysis of Water-Soluble Ionic Contamination of Blast Cleaning Abrasives. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ISO 8502-4:2017; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Tests for the Assessment of Surface Cleanliness—Part 4: Guidance on the Estimation of the Probability of Condensation Prior to Paint Application. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ASTM D4285-83(2018); Standard Test Method for Indicating Oil or Water in Compressed Air. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ISO 8501-1:2007; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Visual Assessment of Surface Cleanliness Rust Grades and Preparation Grades of Uncoated Steel Substrates and of Steel Substrates after Overall Removal of Previous Coatings. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- ISO 8502-3:2017; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Tests for the Assessment of Surface Cleanliness—Part 3: Assessment of Dust on Steel Surfaces Prepared for Painting (Pressure-Sensitive Tape Method). International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 8503-2:2012; Preparation of Steel Substrates before Application of Paints and Related Products—Surface Roughness Characteristics of Blast-Cleaned Steel Substrates Method for the Grading of Surface Profile of Abrasive Blast-Cleaned Steel—Comparator Procedure. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO 4624:2016; Paints and Varnishes—Pull-Off Test for Adhesion. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Arantes, A.; Cruz, C.O. Barriers to the Adoption of Modular Construction in Portugal: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Buildings 2022, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forza, C. Survey research in operations management: A process-based perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Man. 2002, 22, 152–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, H.; Pietila, A.M.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, F.E. Managing the Construction Process: Estimating, Scheduling, and Project Control; Pearson Longman: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0138135966. [Google Scholar]

- Majrouhi, S.J. Influence of RFID technology on automated management of construction materials and components. Sci. Iran. 2012, 19, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Y.W.D.; Panda, B.; Paul, S.C.; Noor Mohamed, N.A.; Tan, M.J.; Leong, K.F. 3D printing trends in building and construction industry: A review. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2017, 12, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, J.; Oke, A.E.; Kineber, A.F.; Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Alaboud, N.S.; Daoud, A.O. Towards a New Paradigm of Project Management: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Wee, H.M.; Daryanto, Y. Big data analytics in supply chain management between 2010 and 2016: Insights to industries. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 115, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, J.; Afridi, N.K.; Khan, K.A. Adoption of Big Data analytics in construction: Development of a conceptual model. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2019, 9, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van De Ven, A.H. Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity, and flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Matthews, J.; Love, P.E.D. Integrating mobile Building Information Modelling and Augmented Reality systems: An experimental study. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewin, N.; Luck, J.; Chugh, R.; Jarvis, J. Rethinking Project Management Education: A Humanistic Approach based on Design Thinking. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 121, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toljaga-Nikolić, D.; Todorović, M.; Dobrota, M.; Obradović, T.; Obradović, V. Project Management and Sustainability: Playing Trick or Treat with the Planet. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.; Arantes, A.; Cruz, C.O. Barriers to the Adoption of Reverse Logistics in the Construction Industry: A Combined ISM and MICMAC Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaras, B.; Wern, T.S.; Kaur, S.; Haslin, I.A.; Ramasamy, R.K. Sustainable Environment to Prevent Burnout and Attrition in Project Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck Schildt, J.C.; Booth, C.A.; Horry, R.E.; Wiejak-Roy, G. Stakeholder Opinions of Implementing Environmental Management Systems in the Construction Sector of the U.S. Buildings 2023, 13, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Major Aspects |

|---|---|

| Causes of delays in construction projects | |

| Aubry et al. [21] | Relationship between organisational culture and the extent of delays. |

| Sweis et al. [22] | Financial difficulties experienced by the contractor and excessive change orders requested by the owner. |

| Arditi and Pattanakitchamroon [23] | Availability of scheduling data, analyst’s familiarity with the project software capabilities, clear specifications in the contract regarding concurrent delays, and float ownership. |

| Kim et al. [24] | Insufficient consideration of concurrent delays and inadequate consideration of time-compressed activities. |

| Gunduz et al. [25] | Quantification of the likelihood of delays in construction projects before the bidding stage. |

| Mahamid [26] | Payment delays, poor labour productivity, lack of skilled personnel, frequent change or-ders, and rework. |

| Arantes and Ferreira [33] | Late progress payments by the owner to the contractor, slow decision-making by the owner, owner interference, increase in the scope of the works, modifications of orders, inappropriate planning and scheduling, errors and discrepancies in drawings, contractors’ financial difficulties, late delivery of materials, changes to the specifications of materials during construction, late procurement of materials, bidding and contract award process, impracticable schedule and specifications in the contract, deficient communication between parties, disputes and negotiations between the parties, and late permits from authorities. |

| Approaches to decrease the likelihood of delay in construction | |

| Kim et al. [24] | Delay Analysis Method Using Delay Section (DAMUDS). |

| Gunduz et al. [25] | Relative Importance Index (RII) methodology with fuzzy logic integrated. |

| Shi et al. [27] | The methodology involves using a series of equations that can be quickly implemented into a computer program and provide rapid access to project delay data and activity contributions. |

| Arantes and Ferreira [33] | ISM-MICMAC analysis methodology to support the development of delay mitigation measures (DMMs) in construction projects. |

| Causes of PM implementation methodologies success | |

| Gudienė et al. [28] | Factors influencing a construction project’s success: external factors, institutional factors, project-related factors, PM-/team member-related factors, project-manager-related factors, client-related factors, and contractor-related factors |

| Radujkovič and Sjekavica [29] | Competent project manager (PJM), a competent team, good coordination between the manager and the team, an adequate organisational structure, culture, atmosphere, and competence, as well as a high usage of PM methodologies, methods, tools, and techniques |

| Radujkovič and Sjekavica [30] | Continuous development of competencies and improvement of management methodologies |

| Greenwood and Miller [31] | The organisational components of management activities have to include meeting the initially set deadlines and costs, making more efficient use of resources, adopting an appropriate management style, facilitating communication among the participants, and ensuring stakeholder satisfaction, with a particular focus on the project owner |

| Ingle and Mahesh [32] | Customer relations, safety, schedule, cost, quality, productivity, finance, communication and collaboration, environment, and stakeholder satisfaction. |

| PRINCE2 | PMBOK |

|---|---|

| Seven principles (continued business justification, learning from experience, defined roles and responsibilities, manage by stages, manage by exception, focus on products, and tailored to the project environment) [3,4,8]. | There is no comparative analysis of controls with PRINCE2 [4]. |

| Seven themes (business case, organisation, quality, planning, risk, change, and progress) [3,4,8]. | Ten knowledge areas (project integration, scope, time, cost, quality, resources, communication, risks, procurement, and stakeholder management) [2,4]. |

| Seven processes (project initiation, project planning, project control, stage boundaries, product delivery management, project closure, and project monitoring) [3,4,8]. | Five process groups (initiating, planning, executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing) [2,4]. |

| Forty-one activities (for example, in the project initiation process, work on the project summary and business case refinement is a repetitive activity, and discussions and document refinement should occur continuously [3,4,8]. | Forty-nine processes (grouped by process groups and knowledge areas, such as project integration management and, creating a PM plan in the planning process group) [2,4]. |

| Forty specified tools and techniques [3,4,8]. | One hundred and thirty-two specified tools and methodologies [2,4]. |

| No. | Name of Quality-Related Activity | Relevant Standard | Satisfactory Criterion/Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Before sandblasting | |||

| 1.1 | Steel surface preparation (welds and imperfections). | ISO 8501-3:2006 [38] | P2 |

| 1.2 | Determination of the presence of soluble contaminants on the surface. | ISO 8502-6:2020 [39]/ISO 8503-5:2017 [40] | 3 μg/cm |

| 2. During sandblasting | |||

| 2.1 | Quality of the surface to be cleaned before sandblasting. | SSPC-SP1 [41] | Oil- and grease-free surface. |

| 2.2 | Blast cleaning abrasives control: conductivity and lubricant contamination. | ASTM D4940-15:2020 [42] | <250 μS/cm at 20 °C temp. |

| 2.3 | Quality of supply air. | - | Oil-, water-, and moisture-free. |

| 2.4 | Environmental conditions during sandblasting: air temperature; relative humidity; dew point; and surface temperature. | ISO 8502-4:2017 [43] | Air and surface temperatures according to the material’s technical data sheet; relative humidity not exceeding 85%; and difference from the dew point greater than 3 °C. |

| 2.5 | Air compressor blotter test. | ASTM D4285:2018 [44] | Free of oil and moisture. |

| 3. Before anti-corrosive painting | |||

| 3.1 | Visual inspection of the sandblasted carbon steel surface. | ISO 8501-1:2007 [45] | SA 2.5 |

| 3.2 | Determination of dustiness on the surface. | ISO 8502-3:2017 [46] | Maximum quantity—2, size—2. |

| 3.3 | Roughness check on the surface of carbon steel. | ISO 8503-2:2012 [47]/ISO 8503-5:2017 [40] | Medium (45–75 µm). |

| 4. During anti-corrosive painting | |||

| 4.1 | Environmental conditions during painting: air temperature; relative humidity; dew point; and steel surface temperature. | ISO 8502-4:2017 [43] | Air and surface temperatures according to the material’s technical data sheet; relative humidity not exceeding 85%; and difference from the dew point greater than 3 °C. |

| 4.2 | Dry film thickness check. | - | Before each layer, according to the specified dry film thickness of each layer. |

| 4.3 | Layered painting. | - | Before every layer of paint. |

| 5. After anti-corrosive painting | |||

| 5.1 | Adhesion measurement (adhesion to coating) test. | ISO 4624:2016 [48] | A value greater than 6 MPa; Performed on SDS >200 µm |

| Function | Project Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Technical director | Advises the project team on technological matters and assists the PJM in making decisions; participates in project discussions and provides support in resolving project-related issues. |

| Project director | Supervises the PJM, organises regular project meetings, and assists in managing project issues; may also arrange additional meetings with the technical director, project director, works organisation manager, and PJM as needed; implements PMT and signs and approves project contracts. |

| Works organisation manager | Ensures an adequate number of contractors and workers, plans human resources and manages their employment and allocation in projects; organises construction documents based on client needs, including assignments, permits, orders, and instructions, which are provided alongside the site file; is responsible for monitoring compliance with safety requirements. |

| Project manager | Estimates and submits commercial proposals to clients, clarifies technical and commercial issues, and negotiates contracts; organises project team meetings, provides project briefings to contractors, monitors work execution, and hands over the site file containing relevant documents; plans initial equipment requirements, facilitates material procurement and equipment delivery, and coordinates construction permits with the client; establishes project control principles, oversees contractor and subcontractor work, monitors project progress, and makes necessary adjustments; ensures quality execution through periodic checks, approves statements and invoices, manages project costs, and participates in project discussions. |

| Supply manager | Ensures the availability of necessary tools as per the list provided by the PJM and contractor; arranges for equipment hire or purchase and its delivery to the site; is responsible for purchasing services, seeking and reserving accommodation, assembling and inspecting the specified equipment, and ensuring its readiness for use; also handles transport arrangements and reports any discrepancies as needed. |

| Warehouseman | Carries out delegated tasks from the delivery manager, arranges necessary equipment based on the provided list by the PJM and contractor, and ensures that the issued equipment for the project is in good working condition. |

| Engineer | Performs assigned tasks by the PJM, prepares construction documents such as assignment permits and orders, and compiles the site file; registers reports submitted by the contractor in the system, and provides plan-invoice outputs to the PJM, works organisation manager, and contractor weekly; also handles forms F2/F3 and internal acts. |

| Works supervisor | Formulates tasks for employees, monitors the progress and quality of work throughout the project; updates the equipment list as needed, signs construction documents including assignment permits, orders, and briefings based on customer requirements, and maintains object files; also submits the completed work to the PJM. |

| No. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | How are projects organised and managed within the company? Please describe the PM structure and responsibilities. |

| 2. | What tools/methods, PM methodologies, or approaches do you use to manage projects? |

| 3. | How do these tools, techniques, PM methodologies, or approaches contribute to improving project delivery? |

| 4. | How do you monitor the progress of construction projects (e.g., human resources, materials and machinery)? |

| 5. | What indicators do you track in project progress? |

| 6. | How often is the project progress monitored? |

| 7. | Does the existing project progress report provide clear and relevant information? |

| 8. | What would you improve in the project progress report? |

| 9. | What decisions does monitoring project progress help you make? |

| 10. | At what frequency is the project progress discussed with the contractors and how is the discussion organised? |

| 11. | Do staff easily assimilate project progress information? |

| 12. | Who in your company takes appropriate action to ensure that the targets are met? |

| 13. | If you see that a project is not going according to the plan, what action do you take? Which units of the company are involved in changing the project plan? |

| 14. | What are the success factors for PM in your opinion? |

| 15. | What are the reasons for project delays in your opinion? What should be avoided in order to deliver the projects on time? |

| No. | Questions | Number of Respondents Who Selected the Answer | Answers as a Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Please indicate your gender. | Men:80 | ~77.0% |

| Women: 24 | ~23.0% | ||

| 2. | Please indicate your age group choosing the appropriate option. | 18–25 age group: 25 | ~24.0% |

| 25–30 age group: 35 | ~33.7% | ||

| 30–40 age group: 31 | ~29.8% | ||

| 40–50 age group: 8 | ~7.7% | ||

| 50+ age group: 5 | ~4.8% | ||

| 3. | What is your educational background? Please select the appropriate option. | Secondary education: 5 | ~4.8% |

| Professional education: 5 | ~4.8% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree: 64 | ~61.5% | ||

| Master’s degree: 28 | ~26.9% | ||

| PhD degree: 2 | ~1.9% | ||

| 4. | What is your work experience in the construction sector by year? Please select the appropriate option. | Up to 1 year: 9 | ~8.7% |

| 1–5 years: 34 | ~32.7% | ||

| 5–10 years: 41 | ~39.4% | ||

| 10–20 years: 14 | ~13.5% | ||

| 20 years and more: 6 | ~5.7% | ||

| 5. | What is your position in the company? Please select the appropriate option. | Assistant manager of projects and works: 20 | ~19.2% |

| Project engineer: 25 | ~24.0% | ||

| Work manager: 12 | ~11.5% | ||

| Project manager: 26 | ~25.0% | ||

| Construction manager: 9 | ~8.7% | ||

| Head of department: 11 | ~10.6% | ||

| Head of the company: 1 | ~1.0% | ||

| 6. | What is the scope of your company activities? Please select the appropriate option. | General construction contractor: 42 | ~40.4% |

| Specialised construction works: 47 | ~45.2% | ||

| Real estate development: 15 | ~14.4% |

| No. | Questions | Number of Respondents Who Selected the Answer | Answers as a Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Which definition of a project do you think is more appropriate for the repetitive construction project? Option 1. Project—a temporary activity designed to create a unique product, service or result. Option 2. Project—a temporary organisation set up to implement one or more products according to a defined business plan. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK): 48 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2): 56 | ~46.2% ~53.8% |

| 2. | Which PM model do you think is more appropriate for the repetitive construction project? Option 1. The PMBOK PM model consists of 5 groups of management processes: initiation, planning, execution, monitoring and control, and closure. Each stage of each process group is followed by a specific deliverable or feedback. Option 2. The PRINCE2 PM model consists of 7 groups of management processes: project supervision, project inception, project planning, stages boundary management, stages control, product development management and project closure. Each process is reviewed by the PJM and approved by the project board. | Option 1 (PMBOK): 23 Option 2 (PRINCE2)—81 | ~22.1% ~77.9% |

| 3. | Which definition of the project team’s responsibilities do you think is more appropriate for the repetitive construction project? Option 1. PJM is the person responsible for leading a project team to achieve the project objectives. Responsible for completing the tasks assigned to the project team. Project team is a group of people working towards common project goals, under the authority of a PJM. Option 2. PJM is the person whose day-to-day focus is on the project, liaising with the project board throughout the project. Delegates tasks to a team leader (e.g., the works manager or works supervisor). Team Leader—responsible for the execution of the tasks assigned by the PJM and the work performed. Regularly delegates completed work for the PJM. Project staff is subordinate to team leaders to carry out assigned tasks. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK)—40 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2)—64 | ~38.5% ~61.5% |

| 4. | Which definition do you think is more appropriate for the repetitive construction project? Option 1. The roles and responsibilities of project team members should be discussed and may be specified during the project. Option 2. The roles and responsibilities of the project members must be described, and each participant must have a clear understanding of their roles and responsibilities before the project starts. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK)—18 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2)—86 | ~17.3% ~82.7% |

| 5. | Do you agree with the statement that the project in question must adhere strictly to the chosen PM methodology? | Agree (related to PRINCE2)—65 Disagree (related to PMBOK)—39 | ~62.5% ~37.5% |

| 6. | Please choose the statement you think is most appropriate for the repetitive construction project. Option 1. The PM methodology must be descriptive, i.e., it describes processes and knowledge areas but does not specify how they are to be used. Option 2. The PM methodology must be prescriptive, i.e., describing what is to be done and when. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK)—18 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2)—86 | ~17.3% ~82.7% |

| 7. | Please choose the statement you think is most appropriate for the repetitive construction project. Option 1. The PM methodology must anticipate the tools and techniques that can be applied to the project. Option 2. The PM methodology has less defined tools and techniques but is not limited to the use of best practice tools and techniques from outside the PM methodology. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK)—41 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2)—63 | ~39.4% ~60.6% |

| 8. | Please choose the statement you think is most appropriate for the repetitive construction project. Option 1. Depending on the progress of the project, a PMO is organised at the request of the PJM or instruction from the project board, involving the project board (e.g., heads of department and company) and the PJM. Option 2. The project board (e.g., head of department and head of the company) must control the work of the PJM and his/her team from project initation to project closure, regardless of the progress of the project. | Option 1 (related to PMBOK)—47 Option 2 (related to PRINCE2)—57 | ~45.2% ~54.8% |

| No. | Project Management Processes | The PRINCE2 Project Management Methodology | Tasks Completed in the Project under Review/Completed by Standard Project Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Project supervision | Regular project meetings with the project board two times a week from the start of the project to the end. | Project discussions/meetings in critical situations separately with managers. |

| 2 | Beginning of the project | Preparation of information and plans in accordance with the principles and theorems of PM methodology. Establishment of a site file, an assignment, and a project order with responsible persons. | Preparation of an object file with technological guidelines (painting technology, drawings, and project requirements) and creation of an assignment authorisation and a project order with responsible persons. |

| 3 | Planning the project | The PJM approves the documentation set out at the start of the project and adds or assigns a task to add information if the information is missing. | Human resources, equipment, and materials are approved by the PJM. |

| 4 | Phase boundary management | The PJM, together with the project board, carefully analyse the phases in progress before providing the PJM with relevant information. If necessary, the project plan is updated. | The project is not phased. |

| 5 | Phase control | The PJM designates the persons responsible for the execution and quality of the works for the intermediate control of each phase. In the event of deviations, they inform the PJM, who takes the initiative for project changes and takes decisions. Meetings are organised by the PJM with the project team leaders and/or members. | The project is not phased. |

| 6 | Product development management | The PJM carries out a quality control check before the work is delivered to the client. The project board controls communication between the PJM and the project team. | Quality control of the PJM is introduced during the project following the comments made. |

| 7 | Closure of the project | Final project documentation is produced, a register of learning from experience is kept, and the results of the project are summarised and evaluated in the company. | Final project documentation, summarising, project results and progress, is presented at the company. |

| Question No. | Summarised Answers to the Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | PM starts with the signing of the contract. The PJM is fully responsible for the success of the project and manages the team to ensure that the outcome of the project meets the terms of the contract, the detailed and technical designs and the budget. For standard, small-scale projects, the project team is quite simple: a PJM, a works manager, a foreman and an engineer. However, the PJM also uses other people in the organisation, such as the supply manager and the warehouse manager. The PM reports in weekly meetings to his/her line manager (head of the department), who controls basic criteria, i.e., time, scope and budget. The unit manager also approves the essential PM tools (PMT), the project plan, and the project schedule. If the project has a deviation from the plan that affects the budget, the unit manager has to approve the costs in the project change committee, which can include everyone, from the accountant to the company shareholders. Thus, the PJM makes decisions that do not affect the budget and plan and do not impact the business. The role of the unit manager is to oversee the execution of the process at various stages, monitor adherence to the plan, approve essential PMT, and organise changes in the event of a major deviation. Clearly, non-standard projects require additional team members, although the roles of the main actors in the project remain almost unchanged. The PJM is supported by an engineer, a supplier, a works manager, a foreman or more, and the control function is taken over by the PMC (project management committee) rather than the department manager. |

| 2. | Tools need to be user-friendly and standardised so that the PJM can manage the project efficiently and those responsible can monitor the project outcome or deviations. The main tools for PM are the risk management software (which we currently use in MS Excel spreadsheet), the project plan, and the project schedule (MS Project). We also use project progress tracking software, which was specifically developed for our company, since in small-scale projects the most important impact on the budget is the man-hours and the material yield. These indicators need to be monitored on an ongoing basis to be able to manage the result and make the necessary decisions. To monitor the budget, we use a database (Power BI) which allows us to monitor data at different cross-sections, outliers, or comparisons with the plan. Project progress and deviations need to be clearly and quickly understood, which is why the traffic light principle is used so that we can quickly see if there is a deviation and if we need to make decisions as soon as the tool is opened. |

| 3. | It is difficult to compete in the market with other organisations if you do not have key advantages (technology you have developed, machinery that your competitors do not have, or the materials you produce yourself), so you have an advantage in PM. The key is to have a standardised project procedure that clearly defines roles, who is responsible for what, who makes decisions and specifies the process and the tools used. As a result, the PJM no longer has to think about what to do or where to go in case of deviations and can therefore be more productive and focused on the outcome of the project. |

| 4. | We can monitor the working hours and materials spent in the previous period for the next day on the traffic light basis. We can see the deviation of one hour and the information is very accurate. The data is also stored to be used for new estimates. We have a unique in-house software for this. We use a tracking program to monitor the machinery where we can see its working hours and fuel consumption rates. |

| 5. | The tools we use are quite effective allowing us to compare the plan of working hours with the fact and the project budget. We can also monitor the result, but it is difficult to understand what decisions are needed in the event of a deviation, so it is most important to monitor the indicators affecting the project result. In our company, the indicators that influence the result the most are man-hours, material yield, and project resources, so we monitor these indicators the most. |

| 6. | It is sufficient to monitor the project result once a month for our projects, as we do not have the possibility to do it more frequently, but the PM has to monitor the indicators that influence the project result on a daily basis to achieve the best project result. And because the tools are user friendly, it takes only 5–10 min a day to review the key indicators. |

| 7. | The traffic-light-based progress tracking software is very user-friendly and time-saving if there is no need for a PJM and a unit manager to go into the figures in detail. Also, it should be standardised. If the traffic light is yellow, the PJM has to make decisions; if it is red, the head of the unit has to find out the reason, and we intend to standardise it in the future. |

| 8. | At the moment, we cannot monitor the direct costs of projects in the current period and compare them with the plan. This can only be conducted at the beginning of the month when the PJM does the material and cost write-off and the accounting department enters the data. If we could monitor this at least every week, we would be able to manage projects more accurately. Clearly, like other indicators, it should give a quick and clear indication of whether there is a deviation and additional time is required. |

| 9. | We do not monitor indicators for the sake of it but to make decisions that will help us manage the outcome of the project. Decisions can take many forms, such as changing the technology or equipment, adjusting the schedule, negotiating extensions, increasing resources, subcontracting, etc., if productivity is not being achieved. If material yields are exceeded, it may be necessary to change materials, order additional quantities, renegotiate with the customer, and arrange a meeting with material and equipment suppliers. It may even be the case that if the indicators show that we will not only be over the budget but also under the cost, the project change committee may decide to cancel the contract. |

| 10. | Usually, if there is no deviation, progress is not discussed with the workers, but this is a bad example, and in any case, progress should be discussed at least once a week. Workers are motivated when they know where they stand. We have tried in the company to send project progress by e-mail, but the figures are not manageable for everyone, so our e-mails get ignored. For larger projects, we use a model where we present the previous day’s progress to the lower management, which helps us communicate the problems that are preventing us from achieving the desired result. The project progress meeting should be no longer than 20–30 min, during which indicators are reviewed and problems are mapped. Another meeting is organised to address the problems. |

| 11. | It is important to show the indicators for which they are directly responsible, i.e., labour productivity and material yield. Although we do not hide the financial indicators of the project in our company, the latter would be redundant. The information conveyed must be simple and clear, and the employees must understand what is going on with the project within 5 min of looking at it, which is why coloured boxes and arrows are used. |

| 12. | The PM is always responsible for the outcome of the project, so he is naturally responsible for monitoring and controlling progress, although he may delegate this task to an engineer to inform him of deviations. The PJM takes action when he sees a deviation and delegates tasks to other team members to clarify or correct the deviation depending on the problem. Alternatives should always be applied, taking the costs and foreseeable risks into account to achieve the best or most appropriate result. |

| 13. | The PM is the person who directly influences the outcome of the project and is solely responsible for communication, both internally and externally. The PJM has the ability to decide which line managers he/she needs to support if the redesign results in a change in the final outcome that is either unchanged or insignificant to the project budget. But if, due to deviations or alternatives chosen, the planned budget is insufficient, the PJM has to approach the division manager with the estimated additional budget needed, who (un)allocates the additional budget as far as possible, or summons a project change committee, which decides on the impact on the company’s results or on the future business. Modification of the project plan and schedule is mandatory in the case of major deviations. |

| 14. | There are three success factors for PM: Firstly, a standardised and user-friendly project implementation procedure, which is where it all starts. Secondly, the behaviour of the PJM in the preparation phase of the project. The better you prepare the project before it starts, the fewer small problems you have to tackle and can concentrate on the execution phase. The primary tools for project preparation are the project plan, the schedule, and the risk management plan. Thirdly, the PJM’s attitude to problems and deviations. If he or she does not feel responsible for the outcome of the project, the outcome will never be good. |

| 15. | The reasons for project delay can be many and varied, e.g., inappropriate choice of materials, insufficient team expertise, inappropriate team structure, poor project preparation, unreliable equipment or suppliers, etc. We can anticipate and prepare for problems in advance and anticipate what we will do if there is a problem. This is a risk management plan. |

| Question No. | Summarised Answers to the Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | New projects are allocated according to the PJM’s workload and the number of projects he manages. From that point on, he/she is responsible for the implementation of the project and for taking decisions to implement it, i.e., from the drafting and modification of the draft contract to the delivery of the project. Surely, the PJM is not responsible for the progress of the work assigned to the work manager, with whom the possible solutions are discussed regularly. The PJM has to keep an eye on the progress of the work, as he takes decisions that the work manager will have to implement. In comparison, private-sector projects are much simpler and require less time input compared to legal entity projects, so ‘bigger’ projects also require extra attention, such as attending the meetings of site construction contractors, constant communication with the construction manager, adjustments to the working design, constant site visits, etc., whereas private-sector projects can be visited up to three or four times if no problems arise. If the project is problematic, if the PJM is unable to resolve the problem or if advice is needed from someone with more expertise, general management meetings are usually held with the participation of the directors of different divisions. A standard project team consists of a PJM, a works manager, a foreman, and workers. |

| 2. | Various tools are used, such as Dalux software and the Electronic Construction Work Log (ECWL). Our company does not have one specific PMT; usually we adapt to the client’s requirements (apps, ECWL, etc.) for larger works. Project allocations are usually based on a hierarchical model, i.e., division directors allocate work to lower-level managers according to the staff availability, who in turn allocate it to work managers, who, in turn, allocate it to workers. A project is usually allocated by the PJM according to priorities, contractual obligations, and deadlines. |

| 3. | New technologies are always good, but they also take time to adapt to. Nevertheless, any digitisation or systematisation of mechanical work is appreciated. For example, the ECWL greatly facilitates the description of the work and thus saves precious professional time. Also, the documentation is not lost and is archived immediately. The app is quite new, so mistakes can happen. |

| 4. | We are currently testing trial versions of various applications to find out what the company needs and which will work best. Recently, MS Excel has been used to track human resources, materials, and machinery, and is also used for materials and warehouses. |

| 5. | Project monitoring consists of many components, such as monitoring whether the project is on track, as most estimates are calculated on a project-by-project basis, worker time is calculated based on past projects of a similar nature, and the time taken to complete various tasks. The progress of the work must also be mentioned, as it is rare for everything to run smoothly in construction, and decisions need to be taken as soon as possible if a problem arises. The quantities of materials used and the wear and tear of machinery are also monitored. The financial results of projects are monitored every month. |

| 6. | Project monitoring depends on the complexity of the site, with private-sector sites requiring much less attention as the solutions are not complex, with some exceptions though. Special structures require much more supervision, as they involve more contractors with whom regular communication is required, and the technical solutions are much more complex and need to be coordinated with a greater number of responsible persons. For example, in the private sector, it is usually sufficient to visit a site up to two to three times (depending on the scope of the work), whereas, in larger sites, meetings are usually held two to three times a week until the project is delivered. |

| 7. | The information is really clear, but we would always like to see improvements, as most of the company staff is older in age and it is quite difficult to do so. Our observation is that each PJM uses his methodologies and principles, and of course, it would be ideal if everyone used the same principle. It would be much simpler, which is why we are trying to innovate in the company. |

| 8. | System optimisation, software upgrades, and deployment are required, as with the better flow of information about the facility, the profit estimation is more accurate. It is also worth mentioning that the company employs about 60% older-age workers who would find all this problematic in their day-to-day work, and we believe that additional funding is needed to improve their computer literacy. |

| 9. | Monitoring project progress helps you keep up with on-site activities so that when problems arise, decisions are made more efficiently and quickly. It also shows the number of staff needed to run the site. Time costs are assessed, which also helps to assess the scope and timing of future works, i.e., more accurate pricing in proposals and more precise schedules for the execution of works. |

| 10. | The frequency of project progress tracking depends on the complexity of the project. If the project is simple and on track, the project will be monitored by liaising with the works manager or the executor of the work. For larger projects (lasting more than one month), such as general contracts, meetings with the works managers, and contractors, are held at least once a week to discuss the progress of the project while at the same time detailing the work fronts. |

| 11. | Workers working on site are given a technical brief, both digitally and on paper (for older people), which contains only relevant and necessary information about the site so they are not overloaded with excessive information. Financial indicators are not provided to the on-site workers, as this information would be superfluous for them (except for supervisors). Each PJM uses a different methodology to assess the progress of the project. |

| 12. | The appropriate action to ensure the achievement of the targets is taken by the PJM or, in exceptional cases, the project director. All decisions relating to the works are to be taken by the PJM. In the case of delays, the PJM will hold a meeting in the company, listen to the proposals, evaluate them, and take an appropriate or alternative decision. |

| 13. | If the implementation is not going according to the plan, the first step is for the PJM to try to find out the reasons. This is followed by a meeting or simply discussing with the works managers how to optimise the work at the same time as updating the work schedules. The PJM submits proposals to the project director on how to optimise the work or how to allocate additional funds to the project. The PJM is always in contact with the client. Changes to the plan affect all levels, from department heads, who have to approve the changes, to the workers, who recieve new technical tasks included in the new work plan. |

| 14. | A constant interest in the site, and monitoring any problems on site, which may not necessarily be our company’s, but may also affect the work we do, so that we can predict and prepare for future problems. Moreover, close cooperation with other companies working on the site, whose help is sometimes very valuable. A good relationship with the client or its representative is essential for the success of the project. |

| 15. | In our case, project delays are mostly caused by production processes, machinery breakdowns, or delays in materials supply. Often it is also the lack of competence of PM or works managers, which leads to unforeseen work. Designers’ decisions and adjustments can also contribute to project delays. Although such risks are quite difficult to avoid, they should be managed by choosing reliable design companies (with extensive experience in specialised work). To avoid project delays, the competence of managers must be continuously upgraded and mechanisms updated. |

| Question No. | Summarised Answers to the Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. | First and foremost, the life of a project starts with a successful sales process, which is the responsibility of the commercial department. Later, as the project moves into the execution phase, a construction execution team is appointed. A typical construction execution team consists of a PJM, a construction manager, a project engineer, and foremen. Depending on the scope or complexity of the project, the project team may be larger, as one project may have several construction managers, project engineers, or construction managers who divide the work among themselves. The PJM is responsible for the success of the project and makes decisions and gives approvals to the issues during the project. |

| 2. | Successful and effective PM consists of applying tools, techniques, and management philosophies to achieve the project’s objectives. The company’s PM uses Building Information Modelling (BIM), which helps to monitor and manage the performance of a building throughout its lifetime, avoiding errors that lead to additional time, cost, and material costs. An intelligent cost forecasting and management software has been implemented. By assessing the purpose of the building, its materials, and other parameters relevant to the project, it allows accurate forecasting of the project costs, opening up the possibility of optimising costs during the project implementation phases. Dalux software is used to record defects and observations, Trimble is used to disseminate information, and MS Project software is used to draw up the project plan, monitor and update the schedule, and draw up the activation plan. In addition, LEAN PM philosophies are widely used in the PM. Visual aids, such as information and accident prevention posters, and a site plan are displayed next to the project to inform the employees. Five Sigma techniques, which are part of the LEAN PM principles, help to organise and control the work in progress, ensure and increase safety on the construction site, avoid repeating mistakes, and promote progress and continuous improvement. These are some of the PM philosophies, tools, and techniques that are applied in PM on different levels of the project team. |

| 3. | The above tools, methodologies, and PM philosophy help to avoid mistakes, save time, costs, and materials, optimise costs during the project phases, plan and control the project, organise and control the project work, prevent accidents, increase safety on site, and promote continuous progress during the project. |

| 4. | The progress of the project in terms of monitoring human resources, materials, and machinery is carried out in several ways—by applying the Asaichi methodology of the LEAN philosophy, which records the objectives and the results of the previous week. The breakdown by work items and the results are recorded in a table. Tracking software is used to monitor the machinery, which indicates the time the equipment is running and the fuel consumed. The progress is also tracked and recorded on the job board on the construction site, and meetings are organised to discuss the project progress. |

| 5. | The PJM monitors labour costs, material, and machinery plans and facts, forecasts project duration, and tracks financial results to derive the overall project outcome. |

| 6. | Construction managers monitor the project progress daily and take appropriate actions if they see that a project is not on track. The financial performance of the project is monitored every month after the write-offs have been made and the subcontractors’ invoices have been approved, and the results are discussed with the project board during the meetings. |

| 7. | The project progress report is presented in an informative manner, with relevant information and results. To facilitate the day-to-day monitoring of the project progress, deviations are highlighted in different colours, with positive deviations in green, minor deviations requiring attention in yellow, and negative positions requiring improvement decisions in red. Material yield and machinery deviations are indicated by arrows comparing the plan with the fact. |

| 8. | There is enough information in the daily project report, and there is room for improvement on the financial side of the project results, as accurate conclusions and assumptions can only be drawn one month after the approval of the payroll, the write-offs of materials and machinery, and the confirmation of subcontractors’ invoices. But a more detailed tracking of the financial progress should be relevant for projects that are not on track and that deviate significantly from the targets, as the additional processing of the information would put an additional burden on the responsible parties. In such cases, intermediate actuation and cost write-offs should be made. |

| 9. | Tracking the project progress helps in decision making. For example, if the work is behind the schedule, additional staff is involved in the project; if work is slowing down but it is not possible to speed up the work process, an additional agreement is negotiated with the client to extend the deadlines. If, due to technology changes, some works cannot be completed on time, additional funds are agreed upon with the client; if materials or machinery used for the works carried out in the project exceed the planned resources, the use of materials and machinery is reviewed for proper application. |

| 10. | The progress of the project is discussed at a meeting attended by the construction manager, the works managers, and the contractors. The meeting will discuss current outputs, issues and problems, and measures to improve performance. Usually, the meeting is held once a week, but the frequency may be increased or reduced depending on the project. The discussion ensures the transfer of information within the project. |

| 11. | Project progress information is passed on to the contractors, who share the information with their staff, so the last link in the analysis of the project progress information is the contractor. The project progress reports show the most relevant indicators for the contractors, such as deviations in outputs and materials, highlighted by colours and arrows. |

| 12. | The construction manager and the works manager take appropriate action to ensure that the outputs foreseen in the design are achieved and monitor the progress of the works and take measures where necessary. Deviations are communicated to the contractors by the supervisors or, in the absence of such supervisors in the design, by the construction manager. The PM, the construction manager, and the works manager are involved in monitoring the progress of the projects, and the works manager is involved in implementing changes. The progress of the projects is continuously monitored by the PJM, as he is responsible for the overall success and financial performance of the project. |

| 13. | A project plan is a roadmap to help steer a project in the right direction. If the project is not going according to the plan, additional meetings are organised to solve problems and to clarify the issues that need to be addressed here and now. To know what changes are needed, it is necessary to have a risk plan in place so that problems are identified in advance and possible solutions are known. Depending on the situation, the project change plan may involve different people from the construction manager to the commercial director. If the problems are routine and ordinary, they are dealt with within the project team by the PJM, but if the PJM is unable to make decisions and the problems are extraordinary, then the higher levels, such as the construction director or his deputy, the commercial director, are called in. |

| 14. | The success factors for PM consist of external and internal factors. The external success factors include detailed and correct design decisions and the timely delivery of materials and machinery. We cannot change the external circumstances, but we can control the internal circumstances, such as a prompt reaction to changes in the project, good teamwork, timely decisions, communication, and continuous planning (updating the project schedule and plan). |

| 15 | The causes of project delays, like success factors, can be both external and internal. External causes of delays include inconsistencies in designers’ drawings, delays in additional solutions, lack of communication with builders, etc. Internal causes of delays include lack of communication, miscommunication, human error, chaotic decisions, lack of skills of the project team, and inappropriate structure of the project team. The external causes of delays cannot be directly influenced, but the internal problems can be solved, and communication is the most important tool to eliminate them. To deliver projects on time, it is necessary to keep the project under constant control, to be aware of the problems and to solve them, and if the problems cannot be solved by the PJM, to raise them to a higher level and take the necessary decisions. |

| Criterion | Company X | Company Y | Company Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | 100–200 employees. | Up to 100 employees. | More than 200 employees. |

| Type of construction activity | Specialised construction work. | Specialised construction work. | A general construction contractor. |

| Standard project team | PJM, works manager, engineer, works executor, and employees. | PJM, works manager, works executor, and employees. | PJM, building construction manager, construction works manager, project engineer, executors, and employees. |

| Tools, techniques, methodologies, and philosophies used for PM | Risk management using MS Excel, MS Project, Power BI, and bespoke project progress monitoring software. | Dalux and MS Excel software, and Electronic Construction Work Log. | BIM, Dalux, Trimble, MS Project, MS Excel software, smart cost forecasting, and management software. LEAN PM philosophy tools—5S and Asaichi. |

| Key indicators on project progress | Man-hours, materials and machinery, and human resources. | Duration of work, wear and tear on materials, and machinery. | Man-hours, materials and machinery, and project duration. |

| Frequency of monitoring project progress | Indicators for ongoing work projects—every day. Financial indicators—every month. | For small-scale projects—depending on the progress of the project. For medium and larger projects—two to three times a week. Monthly discussion of financial results. | Indicators of work in progress—every day. Financial indicators—every month. |

| Frequency of project progress discussions with the implementers | If there are no deviations, progress is not discussed with the contractors. For larger projects—daily meetings, up to 30 min. | Undefined for small projects (up to 1 month) and at least once a week for larger projects. | Usually once a week, with building construction manager, the construction works manager, and the contractors attending the meeting. |

| Areas for improvement in the project progress report | Comparison of direct project costs in the current period with the plan every week. | System optimisation, software upgrades, and installation. | Bi-weekly monitoring of the financial performance of projects not on track. |

| What changes can be made as a result of project progress monitoring? | Changes to work technology or equipment, negotiating work extensions, negotiating unforeseen work, and terminating contracts. | Changes to work schedules, project staffing levels, and cost estimates for subsequent projects. | The number of workers on the project, the agreement with the client on the extension of deadlines, the agreement on additional funds with the client, and the use of materials and machinery. |

| Action if the project does not go according to the plan | A project change committee is organised, and the PJM contacts the head of the unit with an estimate of the additional budget needed. | The reasons for deviations are identified, a meeting is held to optimise the work, and the project plan and schedule are updated. If an additional budget is needed for a project, the PJM makes proposals to the project director. | Priority problems are addressed, meetings are organised with the project team, and, in the case of extraordinary problems, heads of departments attend the meetings to help take appropriate decisions. |

| The following PM success factors were identified | Standardised and user-friendly implementation procedure, detailed project preparation, and PJM’s handling of problems and deviations. | Focus on the project, tracking and optimising malfunction, communicating closely with collaborating companies, and maintaining good relations with the client. | External factors—detailed and correct design decisions and timely delivery of materials and machinery. Internal factors—self-sustained communication of the project team, good teamwork, and continuous planning. |

| Identified reasons for project delays | Inadequate materials, lack of team expertise, inappropriate team structure, and poor project preparation. | Machinery failures, delays in material supply, lack of competence of project teams, and designers’ decisions. | External factors include inconsistencies and delays in design solutions and a lack of communication with contractors. Internal factors include chaotic decisions, lack of skills of the project team, and inappropriate structure of the project team. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simonaitis, A.; Daukšys, M.; Mockienė, J. A Comparison of the Project Management Methodologies PRINCE2 and PMBOK in Managing Repetitive Construction Projects. Buildings 2023, 13, 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071796

Simonaitis A, Daukšys M, Mockienė J. A Comparison of the Project Management Methodologies PRINCE2 and PMBOK in Managing Repetitive Construction Projects. Buildings. 2023; 13(7):1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071796

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimonaitis, Aivaras, Mindaugas Daukšys, and Jūratė Mockienė. 2023. "A Comparison of the Project Management Methodologies PRINCE2 and PMBOK in Managing Repetitive Construction Projects" Buildings 13, no. 7: 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071796

APA StyleSimonaitis, A., Daukšys, M., & Mockienė, J. (2023). A Comparison of the Project Management Methodologies PRINCE2 and PMBOK in Managing Repetitive Construction Projects. Buildings, 13(7), 1796. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13071796