Abstract

Peri-urban villages have become the new hotspot of rural tourism development in China as different actors strive to reconfigure the rural environment in order to meet growing tourist demands, provide distinctive tourism experience, and improve villagers’ quality of life. The presence of diverse stakeholders requires new governance wisdom. This situation also underscores the importance of examining emerging trends to enrich existing literature and guide future practices. Based on first-hand information from interviews, field investigation, and questionnaire surveys, this study illustrates the evolving structure and dynamics of governance approaches and the roles of stakeholders in creating characteristic peri-urban tourism destinations. Three exemplary cases, headed respectively by the local government, a state-owned enterprise, and artists, are investigated and evaluated. We find that collaborative approaches that foster value co-creation and benefit-sharing are gradually replacing earlier governance models that are dominated by a single party, and that proper leadership and institutional design are key to achieving collaborative governance. The findings support recommendations on openness to participation, negotiation and coordination, division of rights and responsibilities, and a combination of incentive and regulatory policies in rural tourism development.

1. Introduction

Peri-urban areas in China are increasingly welcomed by urban residents for their cultural and natural abundance, especially during the post-pandemic period. As a result, vacationing relatively close to home has become a fashionable lifestyle. This new trend also brings about potentially significant changes in the local physical environment and urban–rural interactions. For one, the remaining natural landscapes, cultural heritage sites, and rustic features become valuable assets that trigger rural revitalization [1], despite the fact that peri-urban areas are continuously encroached by urban expansion [2,3]. For another, compared with trips between cities, peri-urban nearcations not only significantly promote material and culture exchange between urban and rural areas but also generate recurring visits [4]. The tourism industry in peri-urban areas is also experiencing tremendous expansion as a large number of urban residents choose destinations near their cities for weekend trips [5].

In this process, certain peri-urban villages become the hotspot of rural tourism development. Tourism benefits these villages by creating jobs, increasing sources of income, improving living conditions, and preserving local culture and heritage [6,7]. It also offers an alternative to conventional peri-urbanization that involves massive demolition and reconstruction [8]. The physical environment of these villages is being reconfigured and upgraded to meet rising demands as various stakeholders including governments, businesses, and local individuals and organizations come onto the scene to manage tourist destinations. These actors provide villages with amenities such as public transportation, lodging, shopping, and emergency medical facilities to ensure safety and comfort. Based on this, they also attempt to create distinctive tourism experience to escape the urban routine. The naturalness and rurality of the villages are emphasized by preserving landscapes with local characteristics, maintaining slow and healthy ways of life, and showcasing the agricultural production process. Through the use of local resources such as cuisine, handicrafts, anecdotes, and folk activities, unique cultural images are created and strengthened.

The entry of diverse stakeholders for tourism development places a higher demand on the quality of governance. Tourism transforms local governance framework as a major economic driver and significantly influences the spatial restructuring of these peri-urban villages [9]. New phenomena also pose great challenges and spark debates on how to convert land and properties with mixed urban–rural functions to accommodate tourism services, how to resolve conflicts between tourism development and environmental protection, how to balance the interests of old villagers and newcomers, and how to create networked organizational structures. These questions are worth exploring to inform future governance practices but are left largely unanswered by previous rural tourism governance models in China, which were often led by either local governments, enterprises or village elites [10,11,12,13]. As argued in the relevant literature, establishing collaborative governance approaches is conducive to sustaining the management of tourism programs, improving the quality of local physical environment, and promoting rural governance overall [14].

Despite the fact that some scholars have started to study the governance and landscape transformation of Chinese tourism villages [13,15,16], relatively few studies have focused on how such collaborative governance approaches evolve and link these approaches with their influence on rural reconfiguration in peri-urban villages. To address this research gap, our study follows three typical peri-urban villages to analyze their collaborative governance approaches and identify the roles of different actors in transforming physical space. We also evaluate the performance of these approaches from the perspectives of stakeholder satisfaction and socioeconomic impact and compare them to draw more general conclusions for tourism-oriented peri-urban communities in China.

The structure of our research is as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on Chinese peri-urban tourism governance, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of three governance models and the emerging transition toward a more collaborative approach. Section 3 provides a general overview of our case study areas and elaborates on the methods we adopt for data collection and analysis. Section 4 summarizes our key findings on new governance approaches in the case study areas and the impact on physical reconfiguration and socioeconomic advancement. Section 5 discusses the theoretical and practical contributions of these cases and points out the prospect of future research. Section 6 concludes the entire paper by highlighting recommendations for governing Chinese tourism-oriented peri-urban communities in the new era.

2. Literature Review

The concept of governance is defined by many scholars in various disciplines such as political science, public administration, corporate management, natural resource management, and tourism [17,18,19]. In general, governance represents a shift from state sponsorship of projects to the delivery of these projects through partnership arrangements involving governmental and non-governmental organizations [20]. Regardless of the context, scholars agree that governance involves a variety of actors who have a stake in the specified task, which means less government control and predictability [18]. The practice of good governance thereby involves the interactions among structures, processes, and traditions that determine how power is exercised, how decisions are made, how expertise and resources are shared between public and private actors, and how citizens or other stakeholders have their say [14,21]. The role of governance has been highlighted in tourism policy literature since the 1990s [17,22,23]. In rural tourism development, in particular, the topic of governance has been conflated with the broader goal of developing rural communities [24].

Rural tourism in China has undergone almost 40 years of development since the 1980s to alleviate poverty and halt the decline of rural areas [25]. Especially after the central government proposed the rural revitalization policy in 2017, the development of rural tourism is experiencing a significant boom as it promotes the industrial development of rural areas and creates employment opportunities [12]. In this process, local governments, businesses, village collectives, and the grassroots are the main actors in contemporary rural development and renewal. The socioeconomic characteristics and physical spaces of Chinese villages are significantly reshaped by the dynamics among these actors [26]. Existing research highlights three different governance approaches for rural village reconfiguration, led respectively by local governments, enterprises, and rural elites [10,11,12,13].

The first type is led by local governments to create new rural images, using incentive measures and dedicated fiscal funds to drive the transformation of selected rural communities. This governance model, which gained popularity in the 2000s and early 2010s, is characterized by the installation of tourism-oriented regeneration projects by using authoritarian methods to acquire land and assets from villages [10]. The affected villagers are forced to leave their former land, relocated to another place, and disempowered to participate in any decision-making processes [27]. This government-driven approach uses rural tourism to gain a political reputation and economic profits and does not necessarily have the benefits to the local population in mind [28]. Unified planning and construction can significantly improve the physical environment and infrastructure of rural villages, but post-implementation management is not sustainable in the long term because local governments typically lack the necessary resources and expertise to manage these programs [12,29].

The second type is driven by profit-seeking businesses, who regard peri-urban villages as lucrative tourism properties. These enterprises purchase the usage rights of rural lands and build enclosed exclaves such as resorts, real estate projects, and amusement parks, without regard for the rural context and local needs [11]. Although the involvement of these enterprises significantly improves the management and maintenance performance of tourism programs, the resulting price increases, environmental degradation, and excessive influx of tourists using public facilities can lead to severe tensions between locals and visitors [30]. Additionally, this approach may harm the distinctive characteristics of rural areas and cause a sense of placelessness [12,31].

The third type is dominated by rural communities and often initiated by so-called rural elites. Rural elites are those who possess business acumen, leadership skills, and networking resources. They explore rural tourism locally and encourage the participation of common villagers [13]. Although villagers are motivated and empowered in many cases, this governance approach usually leads to vicious competition between different villages as they copy the experience of their peers, resulting in the severe homogenization of tourism products [32] or the tragedy of commons in the tourism market [33]. Due to the formation of coalitions of interests within individual villages, it is difficult for outside entities to become involved in the management and operation of local tourism programs [13], which suggests that the success of rural development depends mainly on the competence of rural elites. The model also poses a potential threat to the rural environment, as villagers pursue unregulated and informal ways to expand construction land and increase the square footage of buildings for economic gain [34,35].

In recent years, novel approaches of co-construction, co-creation, and co-management have been pursued to promote the tourism development of peri-urban villages in China [12,13,36]. This new phenomenon aligns with existing literature on collaborative governance, which emphasizes partnerships between state and non-state actors to maximize tourism’s contribution to local development through the effective mobilization of diverse resources [14,19,28,37]. Scholars have taken note of the role of this new paradigm in developing a collaborative system of shared value creation by involving various stakeholders and have been optimistic about its prospect [10,36,38]. The literature also discusses the essential qualities of collaborative governance [14,37,39] and their manifestation in specific cases [12,13,28]. For example, Peng et al. [13] note the new trends of collaborative governance in Shuiji Village of Fujian Province and conclude that there are five core elements of its success, including effective institutional supply, reasonable division of labor, flexible design of the property rights system, adoption of market rules to achieve distributive justice, and rational interactions to balance the power among stakeholders. According to Wei and Hu [39], the fragmentation of property rights among various atomic stakeholders and a lack of strong organization and leadership may lead to the tragedy of the anti-commons in rural tourism development. They recommend establishing rural tourism coordination agencies to distribute interests and resolve conflicts.

Despite the increasing scholarly interest and proliferation of the literature on collaborative governance in rural tourism, new trends in tourism-oriented peri-urban villages in China remain understudied, particularly in light of growing collaborative governance attempts that are currently in play. In addition, little research has focused on why and how these new governance approaches emerge and evolve and associate them with the issue of spatial reconfiguration of rural communities. To address the aforementioned inadequacy, this research explores three typical cases, investigates the process of their governance approaches, and evaluates their performance in spatial reconfiguration and socioeconomic advancement.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study Areas

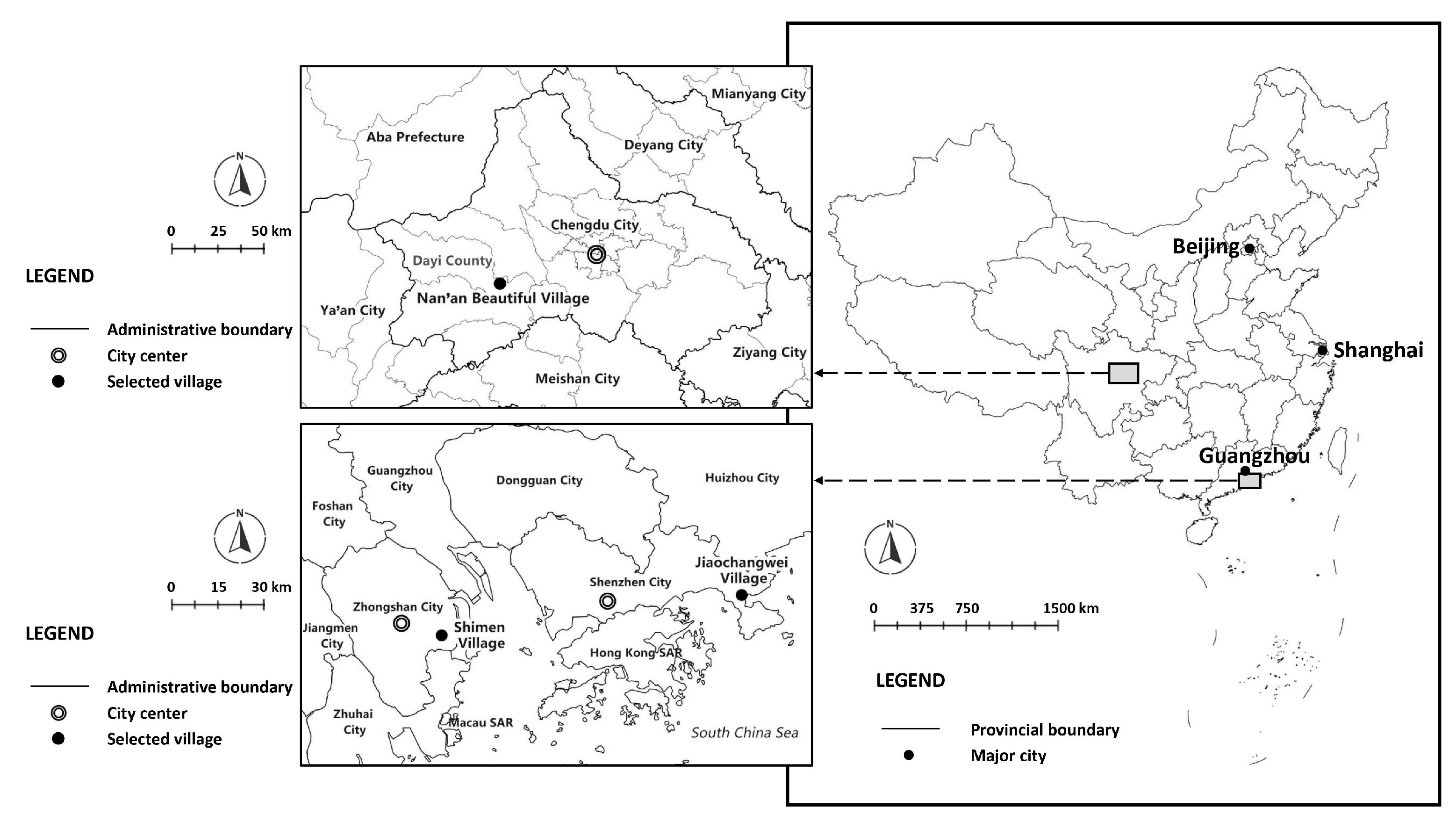

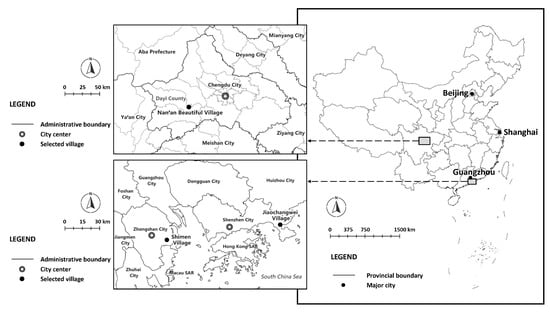

Three peri-urban villages—Jiaochangwei Village, Nan’an Beautiful Village, and Shimen Village—were selected as case study areas for the following two reasons (Figure 1). First, they have accumulated relatively rich experience in reshaping rural areas through collaborative approaches. Second, as model examples initiated by different actors, they have received widespread media coverage and stimulated heated public discussion about whether these cases can be replicated. The first two villages in particular have won awards at the national level, which is a high recognition of their innovative efforts. In summary, the local government leads the transformation of Jiaochangwei Village, a large state-owned enterprise drives the development of Nan’an Beautiful Village, and artists initiate the spatial restructuring of Shimen Village.

Figure 1.

Location of case study areas. Source: Drawn by authors.

Jiaochangwei Village is located 50 km east of Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, and has a resident population of 360. The economic base of this village was weak, as fishing was the main source of income for many generations. Although the village received several small factories that were relocated from the inner city, the majority of its young people moved to the city in pursuit of work opportunities, leading to a severe hollowing out of the village. The village has a long beach and preserves a rich Hakka culture that has the potential to attract tourists. In addition, the surrounding area of this village, the Dapeng Peninsula, has a wealth of tourism resources that form the basis for joint development [3,40]. For example, the 600-year-old walled military settlement Dapeng Fortress is a national historical and cultural site. Dongshan Temple is a Buddhist temple with a long history and many followers.

Nan’an Beautiful Village, with a resident population of 1500, is 47 km from Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province. It consists of the three small villages of Qingyuan, Xinhua, and Caishan, which also suffered from severe depopulation like Jiaochangwei did. Small-scale farming was the only source of income for villagers, apart from finding jobs in the city. These villages have a well-preserved Linpan landscape, characterized by a harmonious combination of rural houses, farmlands, woods, and irrigation canals. A state-owned enterprise, the Overseas Chinese Town Group (hereinafter the OCT Group), entered to lead a tourism project in 2017, which banded together three hamlets under the name of Nan’an Beautiful Village [41].

Shimen Village is located 16 km southeast of Zhongshan, Guangdong Province, and has a resident population of 200. It is close to Cuiheng Village, the birthplace of Dr. Sun Yat-sen, but the village itself does not possess any unique resources or landscapes, unlike the previous two cases. It also faced severe challenges with its physical environment. First, a majority of traditional rural houses were replaced with high-density and unified self-built houses, many of which were unoccupied. Second, unauthorized construction and encroachment on the collective land resulted in a lack of public space. Third, the village once had a few small factories, but they became inactive due to reasons such as environmental regulations, industrial restructuring, and poor operation. Given its predicament, Shimen Village, under the influence of several artists, decided to use art as a means to develop the local tourism industry.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Three primary methods—interviews, field investigation, and questionnaire surveys—were used in our study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to understand the development of collaborative governance approaches. In the field investigation, we used drones and portable GPS receivers to map the general layout of the physical environment and identified spatial alterations brought on by tourism development. We also evaluated the effectiveness of spatial reconfiguration from the perspective of tourists and collaborative governance from the perspective of stakeholders using questionnaire surveys.

3.2.1. Interviews and Field Investigation

We selected village leaders and project initiators as our primary interviewees because they were the most knowledgeable about the entire governance process. The questions included but were not limited to motivations of initiators, different roles of participants and their conflicts, the evolving organizing structures, and their comments on governance strategies. We conducted a cross-check examination by getting in touch with various stakeholders to evaluate the validity of different sources. The information gathered from leaders and initiators was supported by factual evidence.

Specifically speaking, we closely followed the case of Jiaochangwei Village since the beginning of its tourism-driven redevelopment in 2014. We were given the convenience of conducting field surveys and interviews as the planning consultant invited by the town government. We interviewed relevant stakeholders through phone conversations, online meetings, and in-person meetings. We kept an eye on the Nan’an Beautiful Village case ever since the OCT Group arrived. As members of the inspection team convened by the enterprise’s headquarters, we spoke in depth with local officials and the group’s managers who were in charge of this project. We started our investigation into Shimen Village in 2019, interviewing four artists in residence who witnessed the entire process of village development and three other artists who visited the village regularly. We asked the artists in residence for details on governance processes, their stories of art creation in the village, and their opinions on the existing situation and future development. They also showed us the progress of spatial reconfiguration in the village. We also randomly interviewed three short-term artists to obtain their comments on physical space, local governance, and the prospect of art-driven tourism.

3.2.2. Questionnaire Surveys

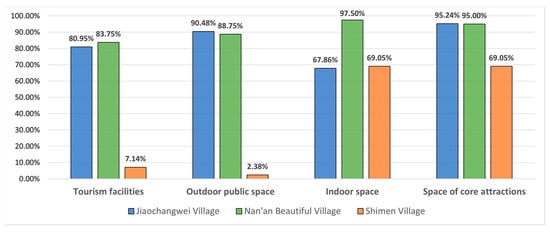

We conducted several rounds of questionnaire surveys to compare the three cases. Our first concern was tourists’ satisfaction with the local physical environment following spatial reconfiguration. Respondents were reminded to focus solely on their evaluation of the physical space rather than destination management issues. In addition to questions on basic information, the questionnaire set up five-point Likert Scale questions on the overall satisfaction and the satisfaction of specific aspects including tourism facilities, outdoor public space, indoor space, and space of core attractions. For these villages, the core attractions referred respectively to the sand beach, Linpan landscapes, and art places. Because the indoor spaces open to tourists were mainly art places, the last two questions were combined in the case of Shimen Village. For ease of analysis, we calculated the scores of satisfaction levels by combing the percentages of “satisfied” and “very satisfied”. In August 2022, the researchers and our assistants distributed questionnaires to 100 randomly selected visitors in each of the three villages. The 84, 80, and 42 valid responses were received in Jiaochangwei, Nan’an, and Shimen villages. Valid responses are those returned questionnaires that provide all the requested basic information, answer all questions attentively, and pass manual reading.

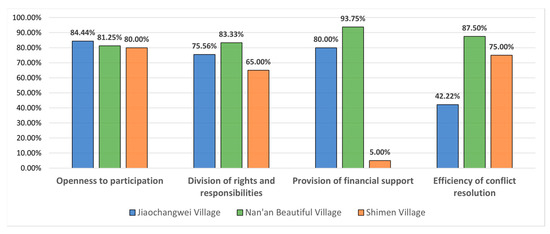

Second, we also investigated how satisfied stakeholders were with different organizing approaches. Local tourism service providers, including former villagers and newly admitted business operators, were selected as our respondents because they were the main stakeholders in tourism development and engaged in daily tourism reception activities. In the questionnaire, we designed the first three questions on their basic information, including types of service, years of operation, and revenues. The fourth question measured the overall satisfaction with existing governance approaches. The fifth to eighth questions addressed the satisfaction on four important qualities of local governance, namely openness to participation, division of rights and responsibilities, provision of financial support, and efficiency of conflict resolution. These four qualities were extracted from the literature and our interviews. Similar to those in visitor questionnaires, the choices had five levels. The researchers and our assistants also distributed questionnaires to 50 randomly selected tourism service providers in each of the three villages in August 2022. We managed to receive 45 (7 locals and 38 newcomers), 48 (22 locals and 26 newcomers), and 20 (3 locals and 17 artists) valid copies, respectively, in Jiaochangwei, Nan’an, and Shimen villages. It should be noted that due to the smaller base of visitors and tourism service providers as well as increasingly stronger access restrictions during the epidemic, we received fewer questionnaires in Shimen Village.

4. Findings

This section describes the structures and evaluates the performance of emerging collaborative governance approaches in Jiaochangwei, Nan’an, and Shimen villages. These governance models derive from the three basic governance prototypes mentioned in the literature review, but they are adapted flexibly in practice to establish collaborative platforms that fit their circumstances. As is demonstrated in the analysis, collaborative governance effectively enhances physical environment improvement and socioeconomic advancement by involving more stakeholders in tourism-driven rural regeneration.

4.1. Description of New Collaborative Governance Approaches

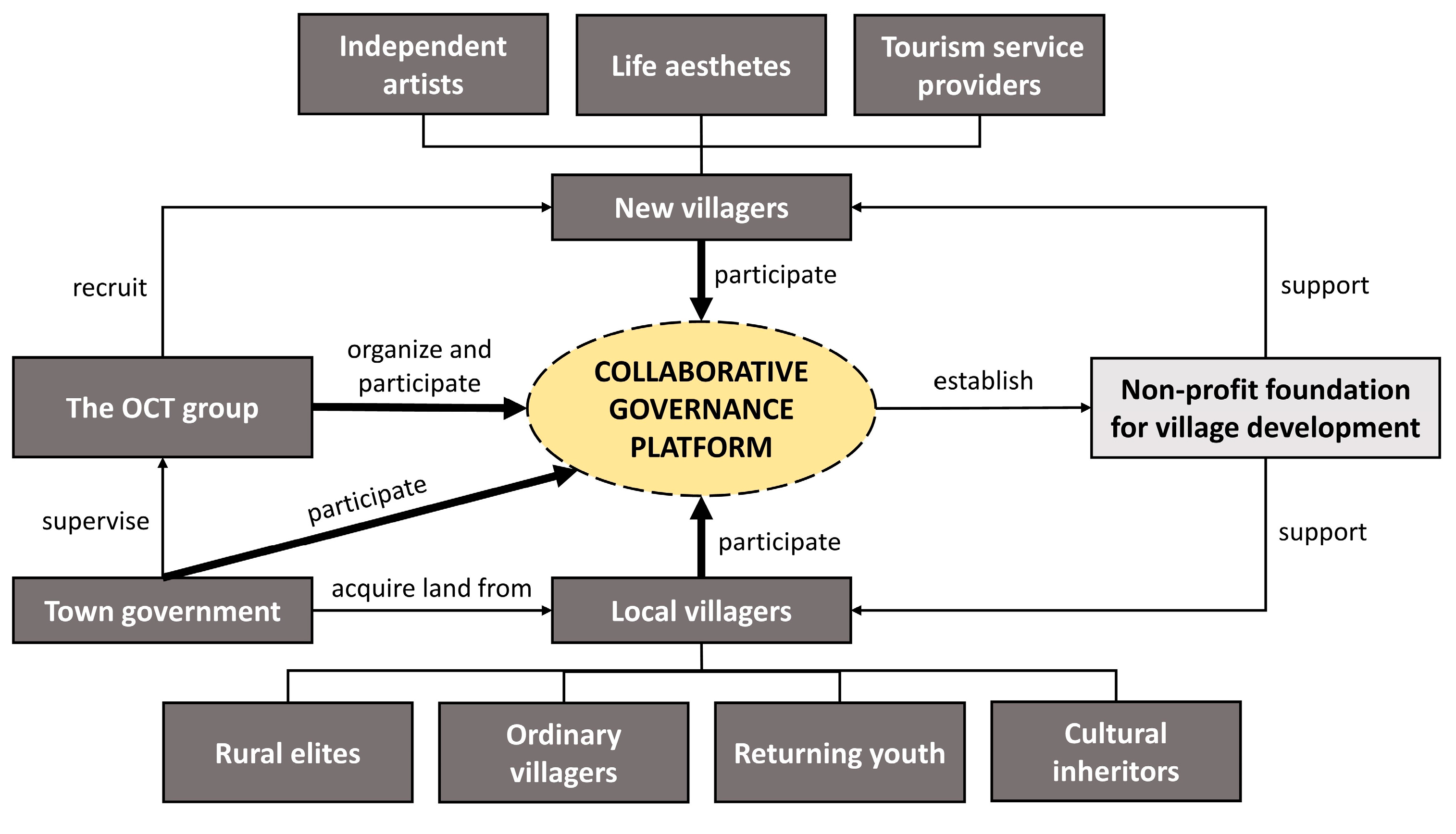

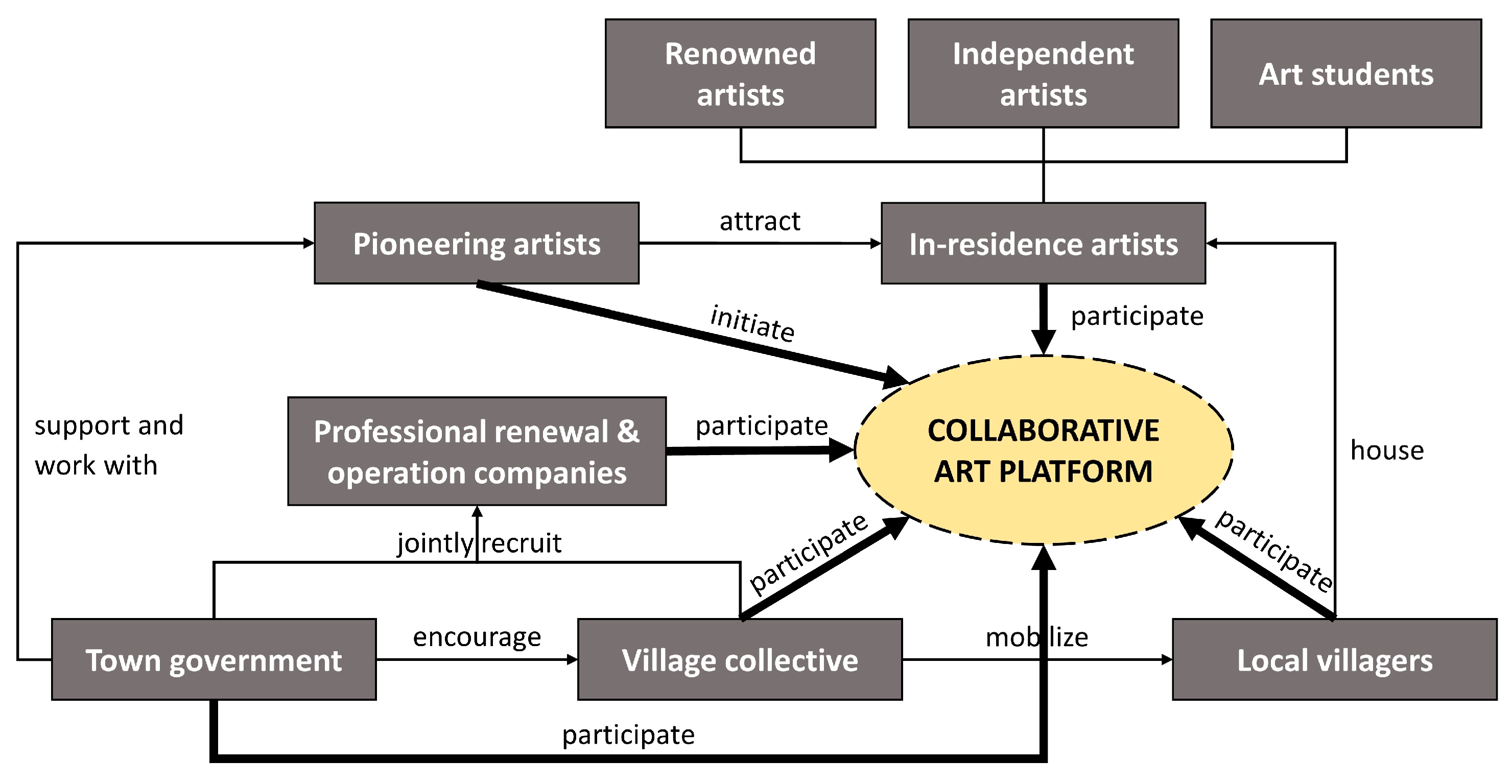

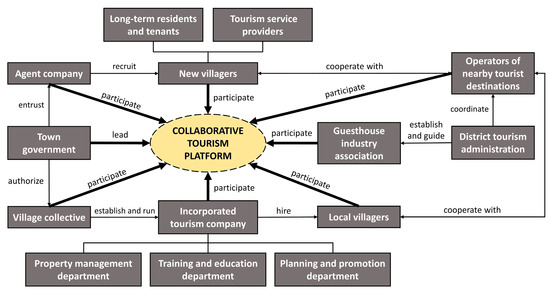

According to the information gathered from interviews, the contributions of major stakeholders and structures of collaborative governance approaches in three cases are explained with illustrative diagrams (for example Figure 2). Each dark gray box in these diagrams represents a particular stakeholder. The directional linkages between boxes show how various stakeholders are connected. The thick arrow lines highlight members contributing to collaborative governance platforms. Using information collected from field investigation, we also mapped the outcomes of spatial reconfiguration in these villages, together with photographs of their important locations.

4.1.1. Collaborative Governance Led by the Town Government

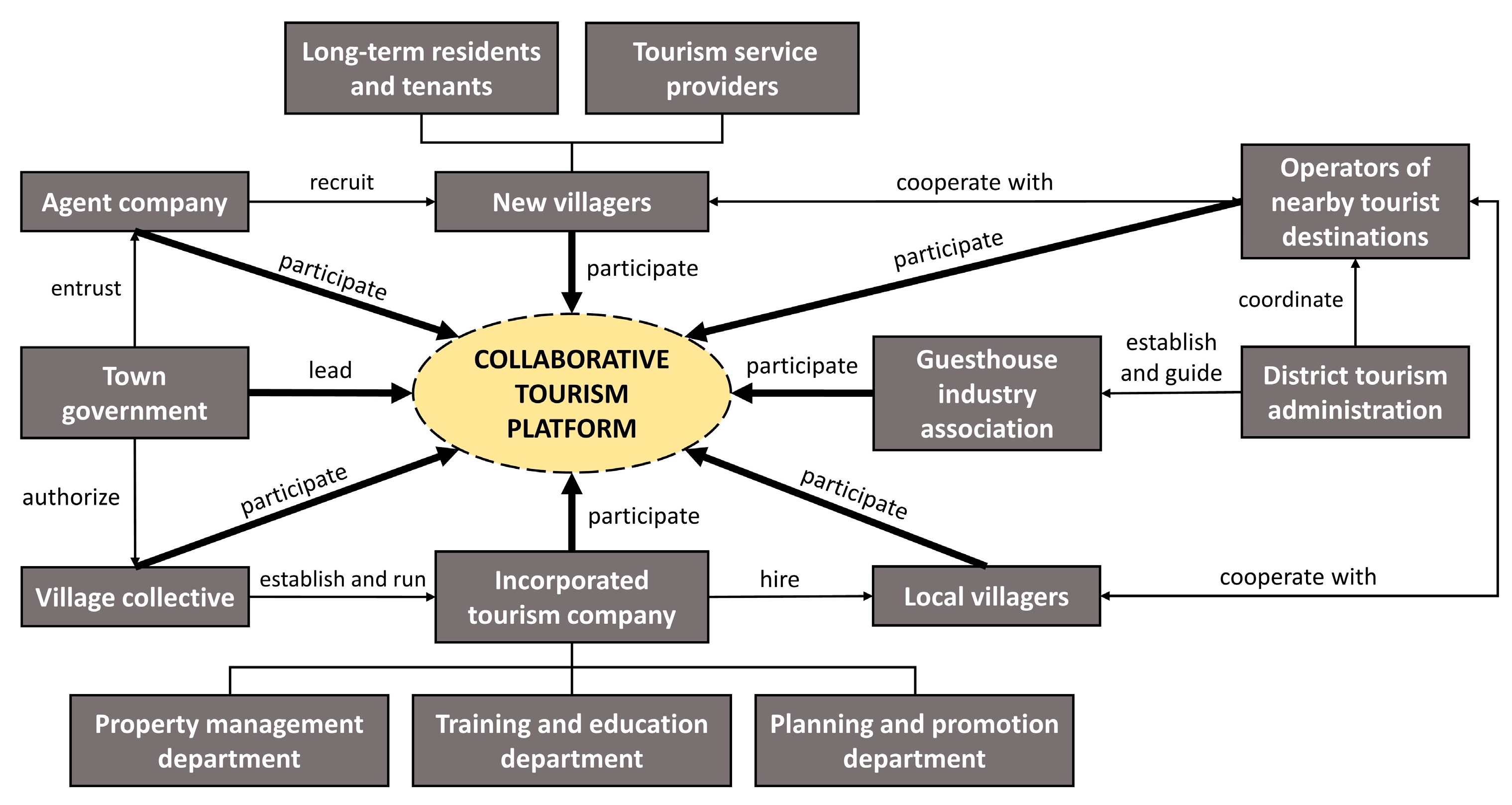

In the tourism development and the resulting spatial reconfiguration in Jiaochangwei Village, the local government abandoned the conventional arbitrary approach and instead sought to establish a collaborative tourism platform that includes multiple actors. Its governance structure involves a wide range of stakeholders, including the town government, district tourism administration, an agent company, the village collective and its incorporated tourism company, local villagers, new villagers, the guesthouse industry association, and nearby tourist destination operators (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Collaborative governance in Jiaochangwei Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on interviews.

Figure 2.

Collaborative governance in Jiaochangwei Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on interviews.

The town government still played a leading role, taking on the duties of making overall plans, organizing various stakeholders, and coordinating resource allocation. First, the government commissioned planning institutes to develop long-term blueprints for local tourism industry development and spatial reconfiguration. Second, it upgraded infrastructure such as roads, lighting, and underground pipelines, provided public service facilities such as parking lots, public toilets, and a tourist reception center, and renovated the seaside environment by eliminating illegal obstacles and establishing parks and nodal squares. The demands of villagers were respected, as the government held extensive consultations and conversations with villagers before all the alterations were made. Third, the government oversaw the entire reconfiguration process to make sure that all parties involved followed the established planning guidelines and local regulations.

The village collective established an incorporated tourism company and took over follow-ups after the completion of public space improvement by the government. The company set up several departments in charge of property management, training and education, and planning and promotion. In contrast to direct management by the local government, this strategy motivated the village and implemented effective management and maintenance. The village collective encouraged local villagers to remodel their private residences for tourism purposes, providing lodgings, dining, and entertainment to tourists (Figure 3). The tourism company helped recruit small tourism service operators for those villagers who wished to rent out their vacant homes and organized knowledge-sharing sessions and professional training programs for a few villagers who aspired to run their businesses. The population of newcomers expanded quickly. Most of these new villagers were business owners and staff members, and some new villagers were short-term residents. The government continuously supervised this process to ensure that any spatial alterations were within the scheme of the predetermined plan.

Figure 3.

Spatial reconfiguration in Jiaochangwei Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on field investigation. Photographs taken by authors.

The local authority proposed extending this collaborative platform by embracing regional co-governance in 2020 in response to the negative repercussions brought by the epidemic. To achieve this goal, the town government entrusted a professional agent company to join the tourism service association in collaboration with nearby destinations including Dapeng Fortress and Dongshan Temple, and assist with its daily operation. Regional tourism integration started to take effect, although the role of this association still needed improvement. The town government also built cycling and pedestrian connections between these destinations and adopted bundled marketing strategies in tourism promotion. In addition, under the guidance of the district tourism administration, a local guesthouse industry association was founded with the aim of establishing uniform market rules and encouraging greater inter-destination coordination, which opened up more opportunities for Jiaochangwei Village. The demands of regional tourism development were considered in the village’s spatial reconfiguration.

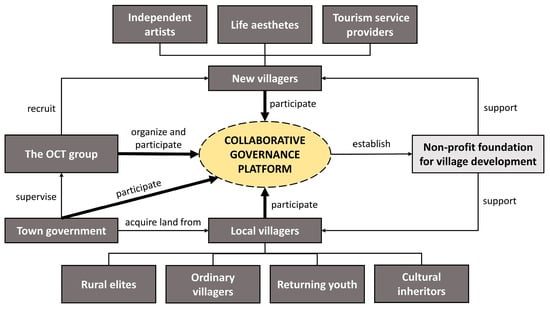

4.1.2. Collaborative Governance Led by a State-Owned Enterprise

Nan’an Beautiful Village challenges our preconceived notion that rural development projects led by enterprises are often profit-driven without concern for the welfare of residents. The enterprise in this case sought to balance economic profits with social responsibility by promoting the revitalization of rural areas. In 2017, the local town government acquired part of the farmland and collective construction land, as well as dozens of homesteads, with the consent of the villagers who wanted to test a new strategy for tourism development. The OCT Group was awarded the contract to develop this project. Due to the foresight of some rural elites who acted as the intermediary between the government, the company, and villager groups, the land acquisition process proceeded efficiently. These representatives negotiated actively with the government and the OCT Group on behalf of all interested villagers, explained the vision and initiatives of the plan to ordinary villagers, and assessed the merits and potential weaknesses of proposed spatial reconfiguration schemes.

In contrast to traditional enterprise-led practices, the OCT Group established a collaborative governance platform in early 2020 that allowed different stakeholders to participate in decision-making (Figure 4). It also established a non-profit foundation to financially support village development. With the help of this foundation, small business owners and individuals could contribute to local reconfiguration. For example, the returning youth started tourism-related businesses, and local artisans and performers acted as cultural inheritors. Ordinary villagers worked as gardeners, cleaners, tour bus drivers, and homestay operators, providing essential tourism services. In addition, the OCT Group hired a considerable number of new villagers including independent artists, life aesthetes, and managerial staff to create an attractive environment and enhance the travel experience of visitors. Local villagers and newcomers shared the tourism market by using the platform as a channel for communication.

Figure 4.

Collaborative governance in Nan’an Beautiful Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on interviews.

The physical environment of Nan’an Beautiful Village was successfully transformed under the joint efforts of stakeholders. Based on consultations with villagers and incorporating their suggestions for renovation, the OCT Group hired professional planning institutes and design firms to adjust the spatial arrangement of the village for tourism development. The traditional Linpan pattern was restored and preserved. According to their original resources, three hamlets inside Nan’an Beautiful Village were given new tourism branding and renamed flower village, rice village, and winery village, respectively. In the middle of these themed villages, a Better Life Center was established, where houses were renovated and used to accommodate visitors and host public events. Greenways were constructed to connect different Linpans (Figure 5). Adaptive reuse was widely used in the renovation of rural buildings. For example, a disused distillery was transformed into a rural meeting and exhibition center where collaborative events were held and old writings, photographs, and wine bottles were displayed to help visitors understand the history of the village. The landscapes were also considerably enhanced. First, wooden walkways were constructed over rice paddies so that visitors could better appreciate the agricultural landscapes. Second, woodlands, flower fields, and ground coverings were installed at key locations to attract tourists, including a large flower park near the north entrance. Third, the farmland was decorated with delicate handicrafts made by cultural inheritors.

Figure 5.

Spatial reconfiguration in Nan’an Beautiful Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on field investigation. Photographs downloaded from https://m.jiemian.com/article/6706017.html (accessed on 20 January 2023), https://m.thepaper.cn/baijiahao_14986218 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

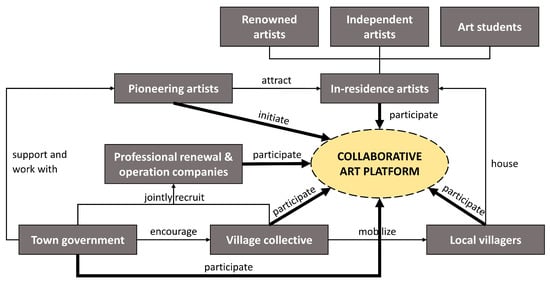

4.1.3. Collaborative Governance Initiated by the Artist Group

The case of Shimen Village presents an unusual example of creating an art community from nothing by building a collaborative art platform (Figure 6). Due to its proximity to Cuiheng Village, some pioneering artists from Beijing chose Shimen Village as the location for their studios in 2009. One leading artist, in particular, played a crucial part in promoting the redevelopment of the village by introducing art-oriented tourism. He proposed to transform the village into a cultural and artistic center where artists could create original works and visitors could enhance their aesthetic sensibility. His idea was strongly supported by both the town government and the village collective, and the government also included this vision in its planning documents.

Figure 6.

Collaborative governance in Shimen Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on interviews.

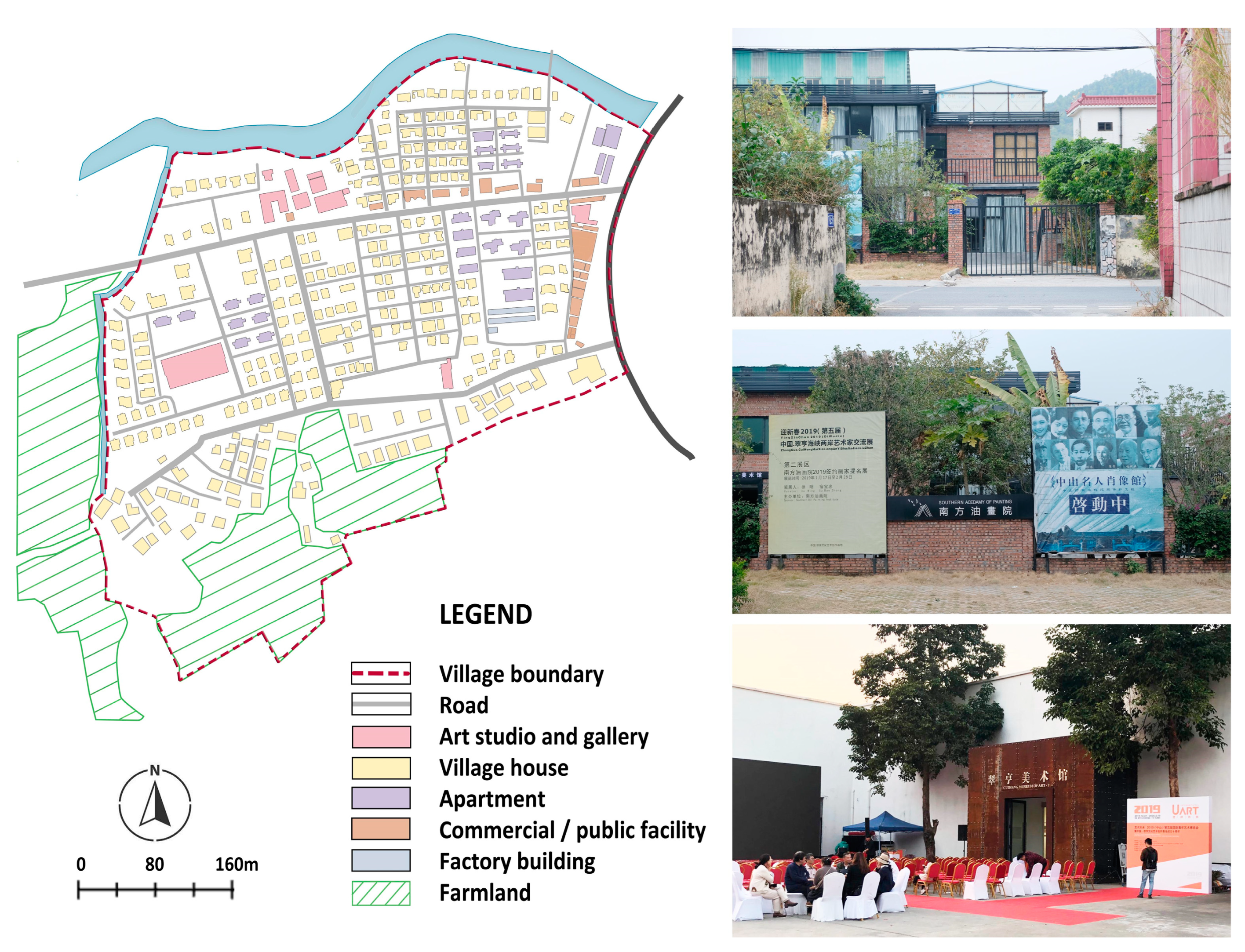

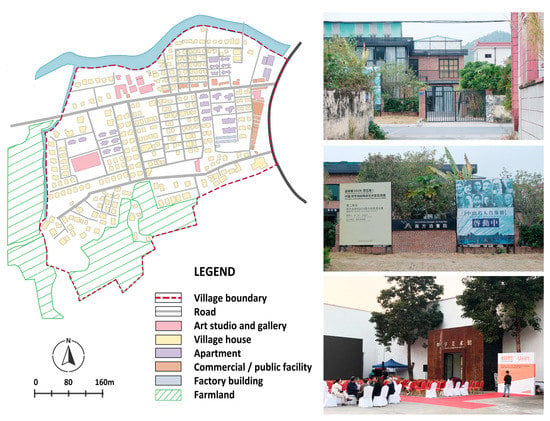

In the initial phase, the government announced a rent waiver policy to invite in-residence artists. The village collective also offered the free use of a considerable part of the unsold area of Cuiyi Garden (about 4400 square meters). With the help of his networks, the leading artist succeeded in attracting a dozen renowned artists after converting the space into art galleries and studios using raised funds. These artists have greatly enhanced the reputation of the village by hosting major art exhibitions and events. After seeing the success, more artists and art students moved to the village for training and continuing their professional careers. The village was revitalized under the influence of the artist group. In the next phase, the village collective continued to provide the artist group with other derelict properties (about 6200 square meters) free of charge, including a water plant, an elementary school, and a gathering hall. These structures were remodeled into galleries, studios, a reception center for artists, and an arts education center. In the third phase, the town government and the village collective tried to mobilize individual villagers to participate in spatial reconfiguration. Some of the private residences were changed into art facilities (Figure 7). However, because the transformation was conducted on an individual basis, the overall physical environment was far from satisfactory to attract more tourists. In particular, it was difficult to find sufficient amenities such as stores, inns, restaurants, and entertainment areas in the village.

Figure 7.

Spatial reconfiguration in Shimen Village. Source: Drawn by authors based on field investigation. Photographs taken by authors.

Witnessing the insufficient development, the town government included Shimen Village in its renewal plan in 2021 and hired professional operating companies to continue spatial reconfiguration. It also set bonus guidelines, provided dedicated funds for public space improvement, and supervised the delivery of local regulations. Operating companies developed detailed action plans, solicited social investment, and worked closely with both artists and villages to bridge spatial demands and supplies. The companies also help run tourism-related businesses and reorganized some physical spaces. Most of the villagers rented out their vacant houses to the operating companies and individual artists to build tourist amenities and art facilities at a lower price than the market rate. A smaller percentage of villagers remodeled their homes to run personal tourism businesses. Some artists also remodeled their rental properties with the owners’ permission and held exhibitions to attract visitors.

4.2. Evaluation of New Collaborative Governance Approaches

4.2.1. Motivations of Initiators

Given the different motivations of their leaders, the three cases differ in governance strategies and qualities of physical spaces. Their levels of satisfaction also varied. In the case of Jiaochangwei Village, the government intended to use this village as a model project to spur tourism growth on the Dapeng Peninsula. According to a senior official of the town government:

The Peninsula is designated as the tourism and leisure area in the comprehensive plan of Shenzhen City due to its coastal scenery. There are more than 40 peri-urban villages in this area that have the potential to develop tourism. The local government chose Jiaochangwei to demonstrate the feasibility and build the confidence of other villages. However, due to the limited resources that may be offered by the government, other villages need to depend more on themselves to attract investment. We use Jiaochangwei as a testing ground and hope that its renewal lessons can contribute to the joint development of tourist villages in the surrounding area.

In the case of Nan’an Beautiful Village, the OCT Group, as a state-owned enterprise, sought to demonstrate its political sensitivity and corporate social responsibility by reshaping the village. We were told the following during our interview with a project manager:

The vast rural area has become the new focus of national development since the launch of the Rural Revitalization Strategy in 2017. As a central government-affiliated enterprise, we need to inform the general public of our commitment to revitalizing rural communities. We aim to demonstrate our capability and expertise in this project, so we set certain criteria when selecting target villages to reach a cost-benefit balance.

In the case of Shimen Village, pioneering artists had no clear intention when they chose the village; instead, they followed their preferences. The leading artist explained his motivation in the following quote:

When I was running an artists’ studio in Zhongshan City, I met a city official. In 2008 he asked me if it was possible to start an artists’ community as part of the local effort to build a renowned historical and cultural city. He suggested several locations and I chose Shimen Village for its proximity to Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s birthplace. In my opinion, it should be able to attract artists.

4.2.2. Satisfaction Levels and Potential Conflicts

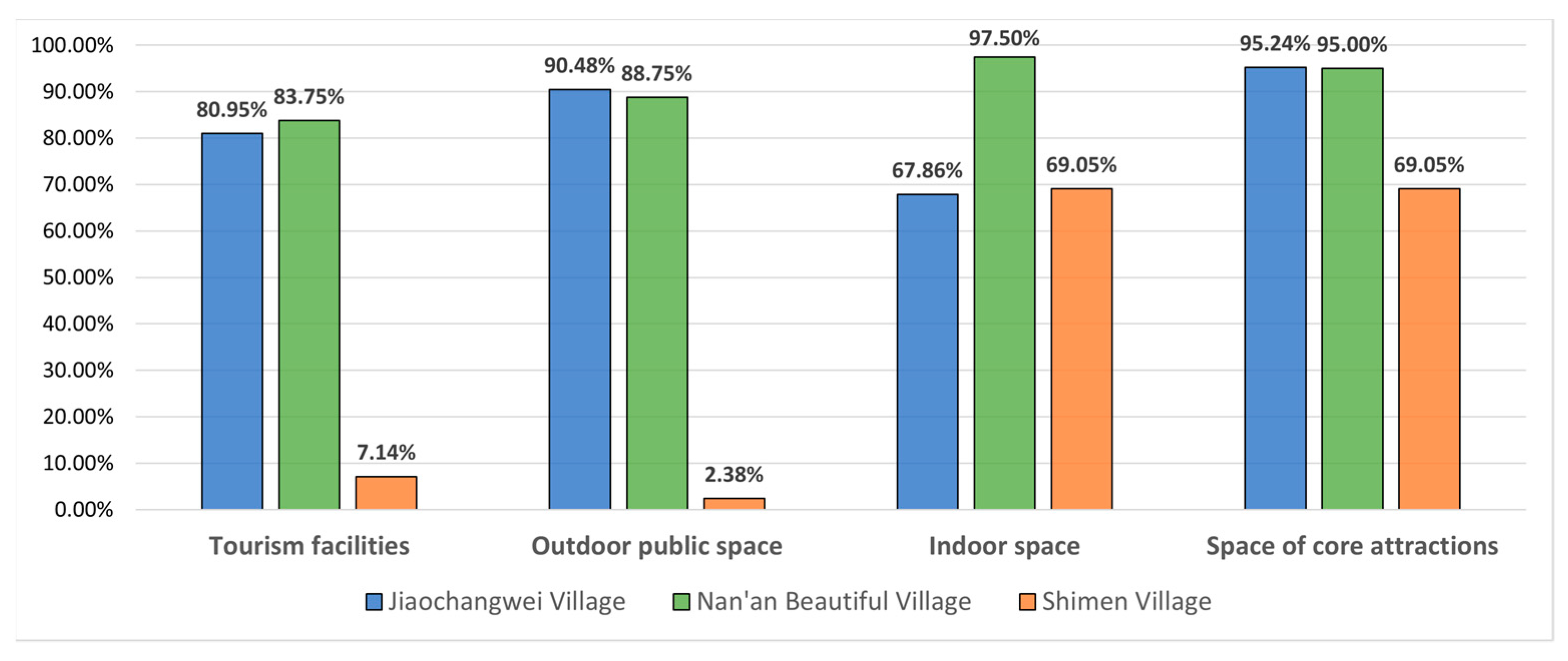

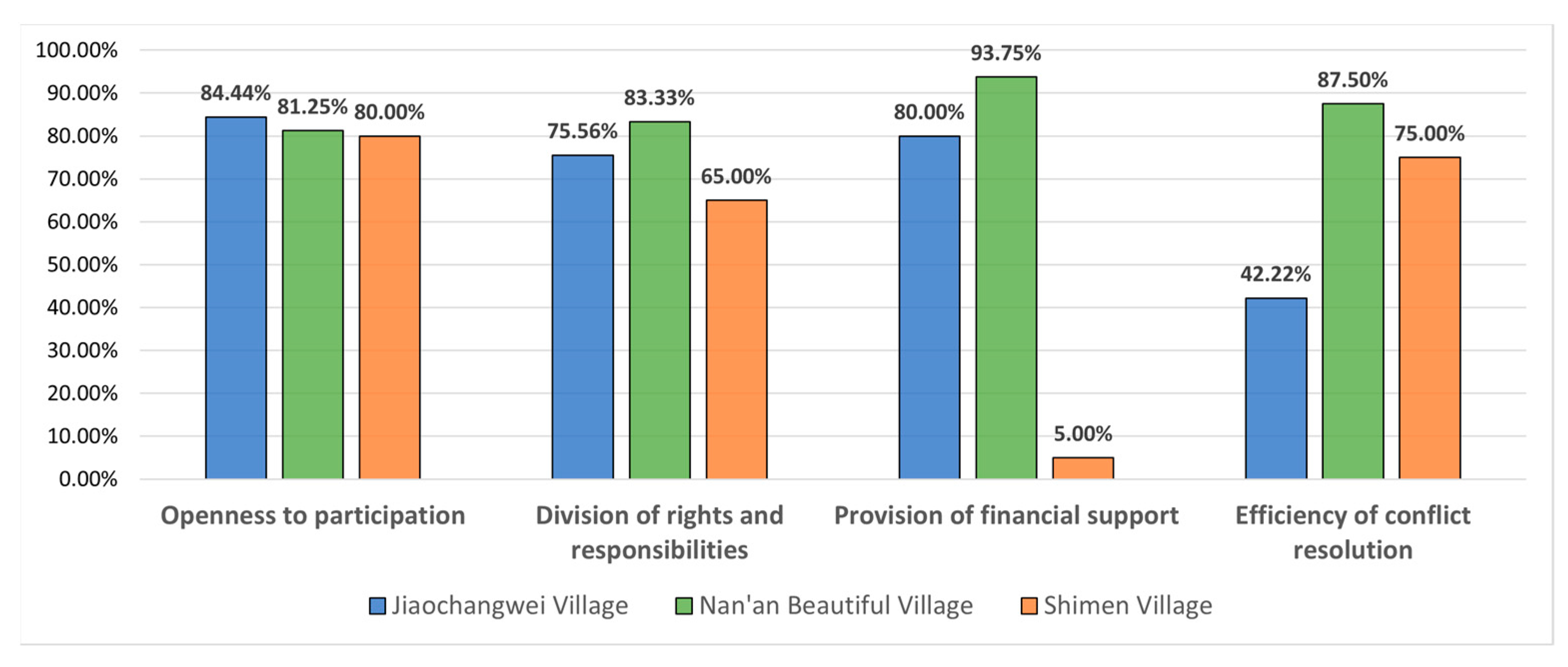

As for Jiaochangwei Village, overall satisfaction with physical space reaches up to 92.86% (78/84), with nearly half (40/84) of respondents being “very satisfied”. In detail, the satisfaction values of outdoor public space and sand beach are rated at 90.48% and 95.24% (Figure 8), which contribute significantly to the good overall impression. The lowest score (67.86%) for indoor space is due to some tourists not visiting the interiors and choosing the “neutral” option. In comparison, only 71.11% (32/45) of tourism service providers feel “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with existing governance approaches, which is probably due to the relatively low satisfaction score (42.22%) on the efficiency of conflict resolution (Figure 9). The fact that most low scores come from new villagers reveals the tensions between new villagers and local villages. These newcomers make a living by renting out residences for tourism services. If local villagers increase the rent significantly after the initial rental period to maximize their interest and are not effectively regulated, the existing mechanism cannot ensure the long-term benefits of new villagers.

Figure 8.

Satisfaction levels on specific aspects of the physical environment. Source: Drawn by authors based on results of questionnaire surveys.

Figure 9.

Satisfaction levels on important qualities of governance. Source: Drawn by authors based on results of questionnaire surveys.

Regarding Nan’an Beautiful Village, the overall satisfaction scores on both physical spaces and governance approaches reach 93.75% (75/80) and 91.67% (44/48), respectively, as evidenced by the excellent results in both specific spaces and qualities of governance (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Unlike Jiaochangwei, the OCT Group owns both the land and buildings, creating an opportunity to implement multi-win regulation. Nevertheless, questions arise as to how the proportion of overnight tourists can be increased and consumption in local guesthouses and hotels can be boosted. We also learned from the interviews that while tourist arrivals exceeded the expected target, many of them were tourists rather than consumers. The local lodging industry did not enjoy commensurate benefits. Hence, it is recommended that the project establish cooperative linkages with nearby destinations to help extend visitors’ stay.

The spatial reconfiguration of Shimen Village uses a point-to-point strategy rather than creating a comprehensive plan. Only 14.29% (6/42) of tourists rate their overall satisfaction as above average. While 69.05% of tourists are satisfied with indoor art places, their outdoor public space experience is lowest at 2.38% (Figure 8). Based on findings in the interviews, lack of financial resources is the main reason for the unsatisfactory physical space, which is confirmed by the low score (5.00%) of financial support given by respondents (Figure 9). However, 70.00% (14/20) of them still believe that local governance can promote art-oriented tourism. Artists had established 28 long-term profitable studios by 2021 and continued to hold artistic events in the village. The main challenges are to attract multi-stakeholder investment and to mobilize the participation of individual villagers. The artists are now pinning their hopes on the newly hired renewal companies, which are working to increase social investment and create connections between different stakeholders.

4.2.3. Impact on Physical Environment and Socioeconomic Conditions

These new approaches significantly enhance the physical environment of peri-urban villages, support their tourism economy, and advance their social development by fundamentally altering the local governing framework.

First, the effect of new governance is reflected most clearly in the reconfiguration of the physical environment. At the local level, both public and private spaces are reorganized according to different tourism functions. The village infrastructure is upgraded and tourism facilities and amenities are installed by renovating abandoned structures and stimulating underdeveloped land. The quality of life for local people is improved by building greenways and beautifying the village environment using decorations with local characteristics. In a larger context, spatial connections between different tourist attractions are strengthened. Regional rural trails and slow traffic systems are introduced.

Second, the employment of new governance approaches effectively promotes the development of the local tourism industry, even during the epidemic control period of 2020–2022. According to the released figures, Jiaochangwei Village attracted 900,000 overnight tourists with a revenue of CNY 500 million in 2016, only one year after the town government renovated its public space. Two years later, when private houses were continuously remodeled for tourist purposes, the number of annual overnight tourists easily surpassed the 1 million mark [42]. Although strict measures were taken to limit tourist arrivals during the epidemic years, tourism prosperity continued. For example, during the May Day holiday in 2020, guesthouse occupancy in Jiaochangwei reached 95% [43]. Similarly, the tourism economy of Nan’an Beautiful Village is also showing strong vitality. The village received 1.1 million visitors with a total revenue of over CNY 310 million in 2021 [44]. Meanwhile, more than 1000 tourism-related jobs were provided to villagers, resulting in an increase in their disposable per capita income from CNY 16,800 in 2017 to CNY 32,000 in 2021 [45]. Most visitors to Shimen Village are art enthusiasts, averaging about 86,000 per year. These tourists, who are the primary buyers of artworks, contribute to the growth of the local tourism sector by purchasing, lodging, and participating in art activities.

Third, these new governance approaches are reshaping social networks and having a positive impact on local civilization. Many of the villagers returned because of the improvement of the physical environment and the promising prospect of the tourism economy, which effectively reversed depopulation. Since over 90% of job openings in Nan’an Beautiful Village were reserved for residents of the local Dayi County, about 500 local youth with higher education attainment have returned to the village to pursue their careers [41]. In addition, the environmental awareness, tourism service skills, and teamwork abilities of the local population have been significantly improved as a result of the training sessions and education programs provided by these collaborative platforms. In our interview with a local homestay operator in Jiaochangwei, we were told of the following:

The tourism service association offers us a variety of professional training and social education opportunities. In these courses, we can learn a lot of practical knowledge about how we operate and manage our business, how we work together with other stakeholders, and the importance of protecting the environment.

In addition, the closed and exclusive clan social structures in these villages are being replaced by open and tolerant social networks. These new governance approaches highlight the diverse contributions of different stakeholders and successfully build networked cooperative links between newcomers and locals. For example, there were more than 30 resident artists and dozens of visiting artists in Shimen Village in 2021 [46]. Among them, many artists have been awarded the title of honorary villagers. These artists welcome local villagers to participate in the creation of their works of art and provide free art education to local children, in addition to renting and remodeling houses. In an interview, a well-known resident oil painter told us:

Shimen Village gives us a lot of artistic inspiration. For one thing, the villagers treat us like family members. Their daily life becomes valuable material for our creation. They often share their opinions on what to paint when we paint outdoors and invited us to their houses for dinner at mealtime. For another, the small number of tourists ensures that our artistic creations are not overly disturbed. In addition, we are under no pressure to pay high rent. In return, we only have to submit two original paintings each year.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

These new approaches described in the three cases demonstrate that cooperative thinking has been gradually embedded in the governance of tourism-driven peri-urban villages in China. Collaborative governance gradually replaces the exclusive, single-party organizational approaches and effectively avoids their disadvantages, which have been criticized by scholars [27,29,30,31,33,35]. In general, all three approaches share the following four characteristics of collaborative governance [14]. First, they strive to create platforms for co-building and co-creation, involve a broader range of stakeholders, and mobilize a wider range of resources, reflecting the attribute of openness to participation. Second, these approaches demonstrate great flexibility to timely modify and refine their structures in response to changing visitor market demands and new challenges. Existing governance structures are the result of past developments and will continue to change as new opportunities and challenges arise. In other words, these approaches underscore the importance of adaptability in enhancing collaborative governance. Third, proper institutional design is implemented by framing clear organizational structures and setting up rules to share rights and define the responsibilities of different actors. Fourth, by emphasizing equity and efficiency, these new approaches respect different stakeholders in an effort to expand overall benefits and minimize conflicts in a more efficient manner. As a result, by integrating stakeholders and establishing value co-creation systems, all stakeholders are willing to cooperate and contribute to community betterment. In this regard, this research not only enriches the scholastic literature of rural tourism development in the context of China and testifies to the theoretical connotation of collaborative governance but also has far-reaching practical implications.

Each of these cases provides valuable lessons that shed light on better public policies governing other tourism-oriented villages. Born out of the state-led governance prototype, Jiaochangwei Village is a good example of how to build strong local government leadership, how to attract more actors to participate, and how to improve connectivity between different stakeholders. First, in addition to clear vision, institutional design, resource deployment, and supervision, the local government builds its leadership by empowering the village collective and entrusting agent companies with expertise. Second, the collaborative platform involves a wide range of stakeholders and creates strong linkages among them to integrate different resources. Stakeholders include not only different levels of state sectors and different types of businesses at the local level, but also associations and non-profit social organizations that serve the entire region. However, the case also reveals the potential weakness of current government-led collaborative governance. The for-profit nature of the local villagers who own land is often the biggest obstacle to building a stable partnership with tourism service providers who rent out their properties. Therefore, it is suggested that the government take a neutral stance, facilitate communication and coordination, and predefine regulatory guidelines to prevent the abuse of land rights.

Nan’an Beautiful Village is a model of new enterprise-led collaborative governance that has achieved great success in satisfying both tourists and stakeholders and enjoys a good social reputation. This case brings us inspiration regarding the following two aspects. First, it highlights the merits of the enterprise-led model in fundraising and destination operation. Its in-depth pre-project research and extensive expertise in tourism-related spatial reconfiguration provide a solid foundation for creating a pleasant rural environment. Meanwhile, its rich experience in dealing with governments and villagers and its well-established business ties with a variety of tourism service providers pave the way for building a collaborative governance platform. Second, more importantly, in this case, corporate social responsibility is a high priority, as evidenced by its motivations and social impacts. The OCT Group maximizes social benefits by seeking to build a collaborative governance platform and maintain the overall spatial pattern economically. Therefore, we suggest that incentive policies be made to attract more qualified enterprises to invest in tourism-oriented village development. These policies should give appropriate compensation and bonuses to encourage enterprises to undertake their social responsibility.

In contrast to the previous two examples, Shimen village seems to be a less positive case due to the significantly lower satisfaction scores with both physical space and local governance. This distortion, however, may be explained by the disparity in project costs. According to our interviews, compared with CNY 150 million spent by the town government in Jiaochangwei, and a total of CNY 1 billion invested by the OCT Group in Nan’an Beautiful Village, Shimen Village raised only about CNY 30 million for this project. In the first two cases, due to the generous inputs of the leaders, the financial risks of other actors are reduced and their worries about undesirable returns are allayed, increasing the degree of willingness to cooperate. However, the case of Shimen Village represents the efforts of numerous ordinary peri-urban villages in China without ideal tourism resources and significant investment, although the current performance is far from satisfactory. Shimen Village offers valuable insight into how to affect change at the local level. First, it is very important to enlist the support of the government and the village collective. Although little direct funding is granted, the policy bonus and rent waiver have indeed made a major contribution to the development of an art community for over 13 years. Second, comprehensive plans and long-term guidelines are essential to ensure that piecemeal renewal strategies can meet the overall needs of village development. Third, the immediate priority is to engage more stakeholders, such as redevelopment companies, to attract sufficient investments. Spatial reconfiguration must have a strong financial guarantee since new facilities, home renovations, and landscaping cost significant sums of money. In view of this, we propose local government policies give solid support to these promising bottom-up initiatives, including but not limited to allocating special funds, incorporating them into statutory renewal plans, and granting prioritized development rights. In addition, we recommend strengthening guidance by establishing artists’ associations to improve the quality of art practices and attractions and adopting stricter conventions for regulating the behavior of individuals to avoid vicious competition.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Although collaborative governance approaches in these cases may have a good prospect for further promotion, they are not immediately transferable to other villages due to differences in the context of their development opportunities. In reality, not all peri-urban villages have the good fortune to be selected by the government, businesses, and artists. Our cases, which represent only a small part of Chinese villages, serve as benchmark projects that demonstrate the political, socioeconomic, and artistic aspirations of various initiators. It is without doubt that their collaborative spirit and experience are valuable references for planning and governing other villages.

Future studies can be improved by considering the following points. First, additional efforts are needed to watch the subsequent evolution of these governance approaches and their long-term effects because they have not taken shape for a long time. Second, further empirical case studies are in need to expound on the theoretical implications of collaborative governance in the context of tourism-oriented rural development in China. The result could be a categorization of typical collaborative governance paradigms and a more nuanced comparison of their similarities and differences considering, for example, local culture of communication, trust-building, face-to-face dialogues, and collaborative processes [37]. Third, it is important to evaluate the implications of the broader urbanization process on the collaborative governance of specific villages, as the phenomenon of urban expansion has a substantial impact on the dual-track urban–rural governance in China [3].

6. Conclusions

Under the guidance of China’s Rural Revitalization Strategy policy framework, tourism has attracted considerable attention as an important means of alleviating rural depopulation, boosting rural economic vitality, and preserving local landscapes and cultures. Peri-urban villages in particular are widely welcomed by urban residents given their favorable geographic location. This trend is strengthened in the post-epidemic period when nearcation becomes a new way of life. In light of this, a large number of peri-urban villages are advised to be better prepared in terms of both their governance and physical environment for growing tourism demands.

Recent years have also witnessed the emergence of multi-stakeholder collaborative governance efforts in rural tourism development, bearing the more common names of co-creation, co-building, and co-governance in the Chinese context. Unlike previous governance approaches that are often dominated by a single party, collaborative governance focuses more on structures and dynamics that lead to shared values and benefits between diverse governmental and non-governmental entities. Although some scholars are beginning to address the topic of collaborative governance in rural areas, there is still a relative dearth of research on the latest developments in collaborative governance of rural tourism in China, especially on the dynamic governance of tourism-oriented peri-urban villages and its spatial and socioeconomic effects.

In response to this insufficiency, this paper describes, assesses, and offers recommendations for three representative cases of collaborative governance that have transitioned from the prototypical government, business, and grassroots-led models. The study finds that despite the fact that their initiators have different intentions for local tourism development, all three cases have managed to establish relatively stable and structured collaborative platforms and mechanisms that involve a wide range of stakeholders. These collaborative governance approaches are developed according to different local contexts, but overall, they help improve the physical environment of peri-urban villages and improve the socioeconomic conditions of local communities. Given these merits, these cases add new wisdom to the governance of peri-urban villages in contemporary China.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. (Yao Sun) and Y.S. (Yiwen Shao); methodology, Y.S. (Yiwen Shao); investigation, Y.S. (Yiwen Shao) and Y.S. (Yao Sun); writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. (Yao Sun); writing—review and editing, Y.S. (Yiwen Shao) and Y.S. (Yao Sun); visualization, Y.S. (Yao Sun); funding acquisition, Y.S. (Yao Sun) and Y.S. (Yiwen Shao). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51908243) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51908362).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Sun, Y.; Shao, Y.; Chan, E.H.W. Co-Visitation Network in Tourism-Driven Peri-Urban Area Based on Social Media Analytics: A Case Study in Shenzhen, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 204, 103934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpoor, H.; Ahani, S. Explaining Objective Forces, Driving Forces, and Causal Mechanisms Affecting the Formation and Expansion of the Peri-Urban Areas: A Critical Realism Approach. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Chen, T.; Li, X. A New Style of Urbanization in China: Transformation of Urban Rural Communities. Habitat Int. 2016, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shen, Y.; Gu, N.; Dai, J. Development Mode of Recreation Belt around the City: Ecological Authenticity or Fashion Creativity? Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 2022, 9292668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Zha, J.; Tang, J.; Ma, R.; Li, W. Spatial-Temporal Disparities in the Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Domestic Tourism Demand: A Study of Emeishan National Park in Mainland China. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ngai, P. Organizational Communications in Developing Ethnic Tourism: Participatory Approaches in Southwest China. Tour. Cult. Commun. 2021, 21, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, F. Experience of Pro-Poor Tourism (PPT) in China: A Sustainable Livelihood Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Culture and Tourism-Led Peri-Urban Transformation in China—The Case of Shanghai. Cities 2020, 99, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahliyana, K.A.; Hadian, V.A. Citizenship Education in Community Development in Indonesia: Reflection of a Community Development Batik Tourism Village. In Promoting Creative Tourism: Current Issues in Tourism Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 35–40. ISBN 1-00-309548-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.W.; Dai, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, J. A New Model of Village Urbanization? Coordinative Governance of State-Village Relations in Guangzhou City, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Xu, H.; Chen, F.; Wei, C. Navigating Adaptive Cycles to Understand Destination Complex Evolutionary Process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Qin, M.; Feng, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, D.; Fang, Y. The Characteristics and Mechanism of Place Reconstruction in Rural Revitalization with the Participation of Government, State-Owned Enterprises and Rural Community: Taking Huanglongxi Village for Example. J. South China Norm. Univ. 2022, 54, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; He, R.; Weng, S. Collaborative Governance Model of Tourism Urbanization in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Shuiji Village in Taining County, Fujian. Geogr. Res. 2018, 37, 2383–2398. [Google Scholar]

- Bichler, B.F.; Lösch, M. Collaborative Governance in Tourism: Empirical Insights into a Community-Oriented Destination. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Rao, X.; Duan, P. The Rural Gentrification and Its Impacts in Traditional Villages―A Case Study of Xixinan Village, in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z. Strategies of Landscape Planning in Peri-Urban Rural Tourism: A Comparison between Two Villages in China. Land 2021, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beritelli, P.; Bieger, T.; Laesser, C. Destination Governance: Using Corporate Governance Theories as a Foundation for Effective Destination Management. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhanen, L.; Scott, N.; Ritchie, B.; Tkaczynski, A. Governance: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. Tour. Rev. 2010, 65, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, K.; Nabatchi, T.; Balogh, S. An Integrative Framework for Collaborative Governance. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2012, 22, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, J.; Abram, S. Defining the Limits of Community Governance. J. Rural Stud. 1998, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumptre, T.W.; Graham, J. Governance and Good Governance: International and Aboriginal Perspectives. 1999, pp. 1–27. Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/122184/govgoodgov.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Hall, C.M. A Typology of Governance and Its Implications for Tourism Policy Analysis. In Tourism Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 37–58. ISBN 0-203-72102-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. Governance, the State and Sustainable Tourism: A Political Economy Approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyim, P. Tourism Collaborative Governance and Rural Community Development in Finland: The Case of Vuonislahti. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, S.; Huang, Y. Rural Tourism Development in China. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 11, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, C.; Duffy, L.; Clark, D. Fostering Tourism and Entrepreneurship in Fringe Communities: Unpacking Stakeholder Perceptions towards Entrepreneurial Climate. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2020, 20, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, M. Rethinking Displacement in Peri-Urban Transformation in China. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2017, 49, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyim, P. Tourism and Rural Development in Western China: A Case from Turpan. Community Dev. J. 2016, 51, 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. From Rural Construction to Rural Operation: Benefit and Dilemma of the Market-Oriented Service Provision in China’s Rural Revitalization. City Plan. Rev. 2020, 44, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Li, R.; Ma, H.; Huang, L. Adaptive Change of Institutions and Dynamic Governance of the Tragedy of the Tourism Commons: Evidence from Rural China. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 53, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seamon, D.; Sowers, J. Place and Placelessness, Edward Relph. In Key Texts in Human Geography; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2008; pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tolstad, H.K. Development of Rural-Tourism Experiences through Networking: An Example from Gudbrandsdalen, Norway. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr.-Nor. J. Geogr. 2014, 68, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Meng, K.; Zhang, Q. Rural Urbanization Led by Tourism. Geogr. Res. 2015, 34, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Guo, Y. Fragmented Peri-Urbanisation Led by Autonomous Village Development under Informal Institution in High-Density Regions: The Case of Nanhai, China. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1120–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wong, T.-C.; Liu, S. The Peri-Urban Mosaic of Changping in Metropolizing Beijing: Peasants’ Response and Negotiation Processes. Cities 2020, 107, 102932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Rethinking Capital in Rural Governance from A Corporatism Perspective: Empirical Research in Village H, Jiangxi Province. Urban Plan. Int. 2020, 35, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C.; Gash, A. Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2008, 18, 543–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chen, H.; Fu, L. Process and Mechanism of Function Evolution of Traditional Villages Under the Background of Tourism Development: A Case Study of Xixinan Village, Huangshan City. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2022, 42, 874–884. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, X.; Hu, Q. Development of Rural Tourism in China: The Tragedy of Anti-Commons. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 939754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Simmons, D. Structured Inter-Network Collaboration: Public Participation in Tourism Planning in Southern China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The OCT Group. The Overseas Chinese Town Group’s Beautiful Country Practices; China Tourism Press: Beijing, China, 2021; ISBN 978-7-5032-6640-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Ni, D. Jiaochangwei Guesthouse Village Implements Enclosed Management from Today. Available online: https://sz.house.ifeng.com/news/2019_06_13-52113695_0.shtml (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, D. Jiaochangwei Ranks First among Gueshouse Villages in the Country, Reported by CCTV. Available online: http://www.sz-qb.com/attachment/pdf/202005/09/d112025c-4a09-42bd-87d3-cc6aef6e9748.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Dayi Media Center. The Linpan Landscape in Dayi Redefines the Countryside of Chengdu’s Park City Goal. Available online: http://nynct.sc.gov.cn/nynct/c100632/2019/11/15/f2894ce8a3184766b9f571551c1b5e20.shtml (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Yang, F. The Overseas Chinese Town Group Explores a New Path for High Quality Development of Cultural Tourism Industry. Available online: https://www.yicai.com/news/101483868.html (accessed on 31 January 2023).

- Nanlang Town Cultural Service and Promotion Center. The “Painter Village” in the Ancient Village Lights up the Village Culture. Available online: https://gdxk.southcn.com/zs/nlzk/xwbd/content/post_652314.html (accessed on 1 February 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).