Investigating Stakeholder Perspectives on the Knowledge Management of Construction Projects: A Case Study of the Vietnamese Construction Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resource-Based View and Knowledge-Based View

2.2. KM in Organsiations

2.3. Emergent Events in Construction Projects

2.4. KM in the Emergent Events Context

2.5. A Case of the Vietnamese Construction Industry

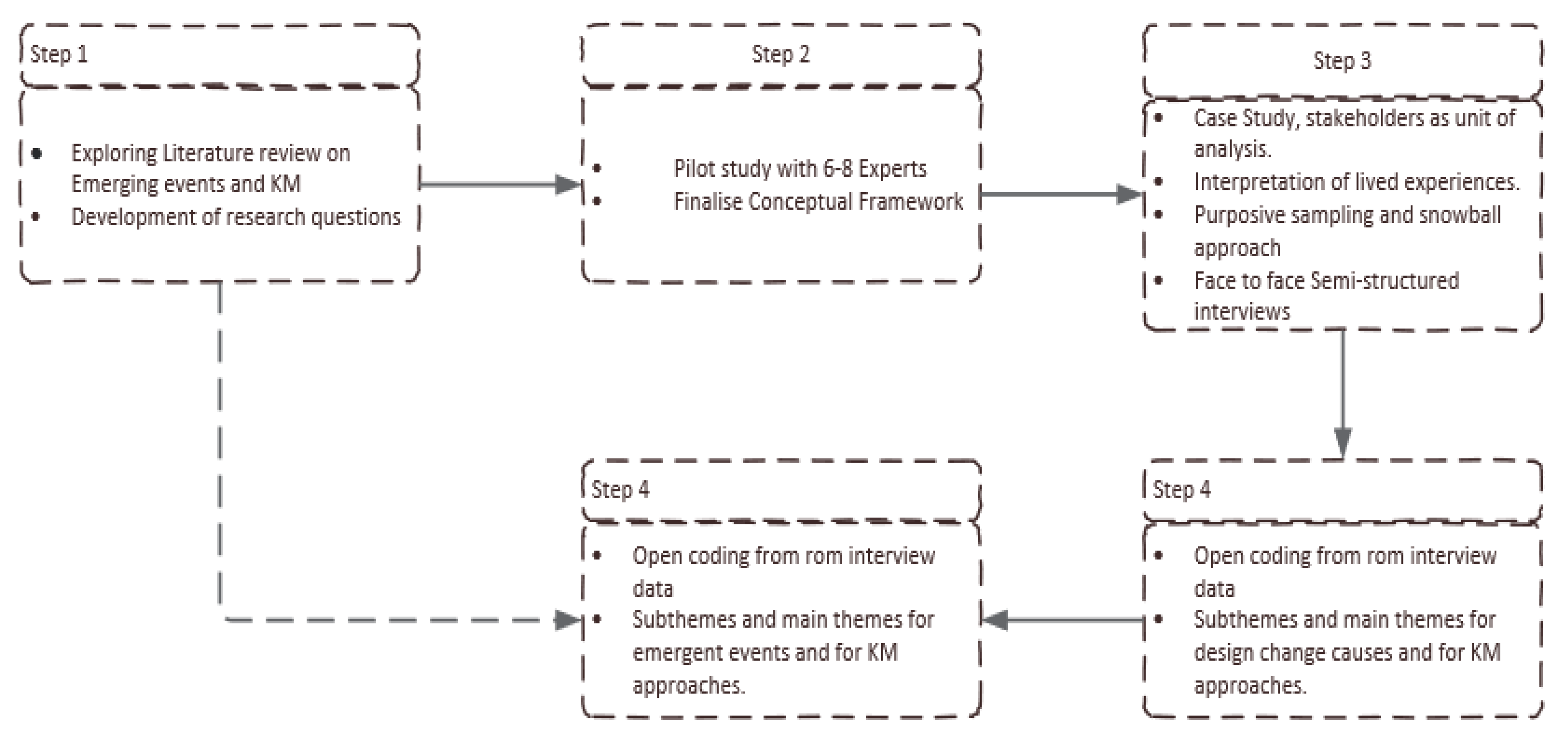

3. Methodology

3.1. Pilot Study

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Analysis

4. Findings

4.1. Emergent Events

4.1.1. Design Changes

4.1.2. Supply Delays

4.1.3. Safety-Related Incidents

4.1.4. Poor Workmanship

4.2. KM Practices to Overcome Emergent Events

4.2.1. Expert-Driven Decision-Making

4.2.2. Knowledge-Sharing Practices

4.2.3. Application of Innovative Techniques and Best Practices

4.2.4. Reuse of Past Project Knowledge and Experience

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bjorvatn, T.; Wald, A. Project complexity and team-level absorptive capacity as drivers of project management performance. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 876–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maylor, H.; Turner, N. Understand, reduce, respond: Project complexity management theory and practice. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 1076–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachbagauer, A. Managing complexity in projects: Extending the Cynefin framework. Proj. Leadersh. Soc. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauget, B.; Wald, A. Relational competence in complex temporary organizations: The case of a French hospital construction project network. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahabi, A.; Nasirzadeh, F.; Mills, A. Assessing the impact of project brief clarity using project definition rating index tool and system dynamic. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Shavarebi, K.; Skitmore, M. Capturing and reusing knowledge: Analysing the what, how and why for construction planning and control. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 875–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Le, Y. Organizational Culture and Knowledge Sharing in Construction Project Organization: A Review. Adv. Inf. Sci. Serv. Sci. 2012, 4, 122–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Bui, T.T.D. Factors affecting construction project outcomes: Case study of Vietnam. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2010, 136, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.N.; Le-Hoai, L. Critical success factors for implementation process of design-build projects in Vietnam. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2016, 14, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maemura, Y.; Kim, E.; Ozawa, K. Root causes of recurring contractual conflicts in international construction projects: Five case studies from Vietnam. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 05018008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.Y.Y.; Pham, V.M.C.; Hoang, T.P. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for architectural, engineering, and construction firms: Case study of Vietnam. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 1105–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.N.; Chih, Y.-Y.; Le-Hoai, L.; Nguyen, L.D. Project-Based A/E/C Firms’ Knowledge Management Capability and Market Development Performance: Does Firm Size Matter. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Tuan, K.N. Delay factor analysis for hospital projects in Vietnam. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.D.; Ogunlana, S.; Quang, T.; Lam, K.C. Large construction projects in developing countries: A case study from Vietnam. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2004, 22, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebekozien, A.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Ramotshela, M. A qualitative approach to investigate stakeholders’ engagement in construction projects. Benchmarking Int. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hällgren, M.; Maaninen-Olsson, E. Deviations, ambiguity and uncertainty in a project-intensive organization. Proj. Manag. J. 2005, 36, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatikonda, M.V.; Rosenthal, S.R. Technology novelty, project complexity, and product development project execution success: A deeper look at task uncertainty in product innovation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2000, 47, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.C.; Anumba, C.J.; Carrillo, P.M.; Bouchlaghem, D.; Kamara, J.; Udeaja, C. Capture and Reuse of Project Knowledge in Construction; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Dosumu, O.S.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Impact of Design Errors on Variation Cost of Selected Building Project in Nigeria. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Edwards, D.J.; Watson, H.; Davis, P. Rework in civil infrastructure projects: Determination of cost predictors. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Smith, J.; Teo, P. Putting into practice error management theory: Unlearning and learning to manage action errors in construction. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 69, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, P.; Ruikar, K.; Fuller, P. When will we learn? Improving lessons learned practice in construction. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, M.; Eppler, M.J. Harvesting project knowledge: A review of project learning methods and success factors. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Skitmore, M. Investigating design changes in Malaysian building projects. Archit. Eng. Des. Manag. 2017, 14, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. J. Manag. 2016, 27, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, E.; Loosemore, M. The impacts of industrialization on construction subcontractors: A resource based view. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M.; Baden-Fuller, C. A Knowledge-Based Theory of Inter-Firm Collaboration. Acad. Manag. Proc. 1995, 1995, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.S.W. Knowledge creation in multidisciplinary project teams: An empirical study of the processes and their dynamic interrelationships. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, T.; Finegan, A.; Walker, D. Applying project histories and project learning through knowledge management in an Australian construction company. Learn. Organ. 2006, 13, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Shavarebi, K. Enhancing project delivery performances in construction through experiential learning and personal constructs: Competency development. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 22, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Abdul-Rahman, H.; Chen, W. Collaborative model: Managing design changes with reusable project experiences through project learning and effective communication. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1253–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Helo, P.; Kekäle, T. Critical factors for knowledge management in project business. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Tsui, E.; Kianto, A. Knowledge-friendly organisational culture and performance: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L. Organizational Learning: Creating, Retaining and Transferring Knowledge, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.L.; Scarbrough, H. Knowledge management in practice: An exploratory case study. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1999, 11, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanyi, M. Knowing and being. In Knowing and Being: Essays; Grene, M., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969; pp. 123–207. [Google Scholar]

- De Long, D.W.; Fahey, L. Diagnosing cultural barriers to knowledge management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2000, 14, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.B.; Khan, K.I.A.; Nasir, A.R. Tacit knowledge sharing in construction: A system dynamics approach. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge Management and Knowledge Management Systems: Conceptual Foundations and Research Issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, G.D. Knowledge management in organizations: Examining the interaction between technologies, techniques, and people. J. Knowl. Manag. 2001, 5, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; Ingram, P. Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2000, 82, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Liu, X.; Andersson, U.; Shenkar, O. Knowledge management of emerging economy multinationals. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohale, V.; Ambilkar, P.; Gunasekaran, A.; Verma, P. Supply chain risk mitigation strategies during COVID-19: Exploratory cases of “make-to-order” handloom saree apparel industries. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2022, 52, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, G.N.; Tsai, J.C.-A.; Jiang, J.J.; Klein, G. Coping with uncertainty: Knowledge sharing in new product development projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2021, 39, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri-Ghasabeh, M.; Chileshe, N. Knowledge management: Barriers to capturing lessons learned from Australian construction contractors perspective. Constr. Innov. 2014, 14, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anumba, C.J.; Egbu, C.; Carrillo, P. Knowledge Management in Construction, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, J. Formal and Informal Practices of Knowledge Sharing between Project Teams and Enacted Cultural Characteristics. Proj. Manag. J. 2015, 46, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadonikolaki, E.; Verbraeck, A.; Wamelink, H. Formal and informal relations within BIM-enabled supply chain partnerships. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2017, 35, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Palladino, R.; Pezzi, A.; Kalisz, D.E. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marandi Alamdari, A.; Jabarzadeh, Y.; Samson, D.; Sanoubar, N. Supply chain risk factors in green construction of residential mega projects—Interactions and categorization. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 30, 568–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Nohria, N.; Tierney, T. What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 106–116, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Brosch, G.; Yang, B.; Cadden, T. Dissemination and communication of lessons learned for a project-based business with the application of information technology: A case study with Siemens. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 31, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T. Knowledge Networks: Explaining Effective Knowledge Sharing in Multiunit Companies. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasvi, J.J.; Vartiainen, M.; Hailikari, M. Managing knowledge and knowledge competences in projects and project organisations. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2003, 21, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen, K.; Kujala, J.; Lehtonen, P.; Ruuska, I. A stakeholder network perspective on unexpected events and their management in international projects. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2010, 3, 564–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, A. Project management of unexpected events. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2008, 26, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatitu, J.N.; Kabubo, C.K.; Ajwang, P. Approaches on Mitigating Variation Orders in Road Construction Industry in Kenya: The Case of Kenya National Highways Authority (KeNHA). Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2020, 10, 6195–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.; Hobbs, B. The complexity of decision-making in large projects with multiple partners: Be prepared to change. In Making Essential Choices with Scant Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 375–389. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A leader’s framework for decision making. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 68–76, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Suresh, S.; Olayinka, R.; Chinyio, E.; Renukappa, S. Impact of knowledge management on construction projects. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Manag. Procure. Law 2017, 170, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.D.; Smith, J.; Ackermann, F.; Irani, Z.; Teo, P. The costs of rework: Insights from construction and opportunities for learning. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.S.; Elhegazy, H.; Elzarka, H. Key factors affecting the decision-making process for buildings projects in Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yap, J.B.H.; Wood, L.C.; Abdul-Rahman, H. Knowledge modelling for contract disputes and change control. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saoud, L.A.; Omran, J.; Hassan, B.; Vilutiene, T.; Kiaulakis, A. A method to predict change propagation within building information model. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2017, 23, 836–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Lin, E.T.A. Conceptualizing “COBieEvaluator” A rule based system for tracking asset changes using COBie datasheets. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 1093–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilter, O.; Celik, T. Investigation of Organizational and Regional Perceptions on the Changes in Construction Projects. Tek. Dergi 2021, 32, 11257–11286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotnour, T. Organizational learning practices in the project management environment. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2000, 17, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Gilovich, T. The anchoring-and-adjustment heuristic: Why the adjustments are insufficient. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, T.; Finegan, A.; Walker, D. Biases and heuristics in judgment and decision making: The dark side of tacit knowledge. Issues Informing Sci. Inf. Technol. 2004, 1, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Arif, M.; Egbu, C.; Toma, T. Knowledge retention in construction in the UAE. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference of the Association of Researchers in Construction Management (ARCOM), Leeds, UK, 6–8 September 2010; pp. 887–896. [Google Scholar]

- Egbu, C.O. Managing knowledge and intellectual capital for improved organizational innovations in the construction industry: An examination of critical success factors. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2004, 11, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Lim, B.L.; Skitmore, M.; Gray, J. Criticality of project knowledge and experience in the delivery of construction projects. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2022, 20, 800–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle, M.; Paul, W.; Kate, H. 2022 Engineering and Construction Industry Outlook; Deloitte Consulting LLP: New York, NY, USA, 2022; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- GSO. Press Release Social and Economic Situation in the First Quarter of 2018; General Staistics Office: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Nhat, H.; Nguyen Tuan, N.; Vu Thi, H.; Dao Hong, Q.; Le Thi Thuy, D. Vietnam Economic Situation; FPT Securities: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2019; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V. Ready for the Leap; FPT Securities: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015; pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Statista Dossier on the construction industry in Vietnam; Statista: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Le, N. Vietnam construction industry performance issues and potential solutions. J. Adv. Perform. Inf. Value 2017, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.H.; Dinh, T.H.; Gotze, U. Roadworks design: Study on selection of construction materials in the preliminary design phase based on economic performance. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, Q.V.; Nguyen, T.Q. A Case Study of BIM Application in a Public Construction Project Management Unit in Vietnam: Lessons Learned and Organizational Changes. Eng. J.-Thail. 2021, 25, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, N.V.; Toan, N.Q.; Phong, V.V.; Durdyev, S. Impact of BIM-related factors affecting construction project performance. Int. J. Build. Pathol. Adapt. 2023, 41, 454–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, N.L.; Tuan, N.A. Modeling of planning function management in Vietnam’s public construction works. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2023, 13, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Hadikusumo, B. Impacts of human resource development on engineering, procurement, and construction project success. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2017, 7, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toan, N.Q.; Tam, N.V.; Hai, D.T.; Quy, N.L.D. Critical Factors Affecting Labor Productivity within Construction Project Implementation: A Project Manager’s Perspective. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 751–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.P.; Chileshe, N. Revisiting the construction project failure factors in Vietnam. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2015, 5, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, K.D.; Nguyen, P.T.; Nguyen, Q. Disputes in Managing Projects: A Case Study of Construction Industry in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, X.B.; Nguyen, Q.B.M.; Ma, T.; Gao, S. Soft skills of construction project management professionals and project success factors: A structural equation model. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Thuyet, N.; Ogunlana, S.O.; Dey, P.K. Risk management in oil and gas construction projects in Vietnam. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2007, 1, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanh, H.D.; Kim, S.Y. Evaluating impact of waste factors on project performance cost in Vietnam. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 18, 1923–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.N.; Le-Hoai, L. Relating knowledge creation factors to construction organizations’ effectiveness. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2019, 17, 515–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, S.T.; Nguyen, V.T.; Nguyen, N.H. Relationship networks between variation orders and claims/disputes causes on construction project performance and stakeholder performance. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Do, S.T. Assessing the relationship chain among causes of variation orders, project performance, and stakeholder performance in construction projects. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2023, 23, 1592–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, P.N.; Vu, L.T. Knowledge Management Model for Construction Design Consulting Companies. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, N.H.; Nhi, D. Comparative Analysis of Knowledge Management Software Application at E&Y and Unilever Vietnam. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2019, 6, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N.T.D.; Aoyama, A. Exploring cultural differences in implementing international technology transfer in the case of Japanese manufacturing subsidiaries in Vietnam. Contemp. Manag. Res. 2013, 9, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Burgess, S. A case analysis of ICT for knowledge transfer in small businesses in Vietnam. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Q.H. Information technology competence, process management and knowledge management: A case of manufacturing firms of Vietnam. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 763–773. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc-Tan, N.; Gregar, A. Knowledge management and its impacts on organisational performance: An empirical research in public higher education institutions of Vietnam. J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 18, 1950015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.T.; Pham-Nguyen, A.-V.; Misra, S.; Damaševičius, R. Increasing innovative working behaviour of information technology employees in Vietnam by knowledge management approach. Computers 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, L.; Thi, C.H. Critical Success Factors In Knowledge Management: An Analysis of the Construction Industry in Vietnam. J. Econ. Dev. 2019, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; Volume 5, p. 219. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N. Research Methods for Business Students, 5/e; Pearson Education: Bangalore, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzes, D.S.; Dybå, T.; Runeson, P.; Höst, M. Case studies synthesis: A thematic, cross-case, and narrative synthesis worked example. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2015, 20, 1634–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.D.; Chileshe, N.; Rameezdeen, R.; Wood, A. External stakeholder strategic actions in projects: A multi-case study. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.D.; Lopez, R.; Edwards, D.J. Reviewing the past to learn in the future: Making sense of design errors and failures in construction. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2013, 9, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Teo, P.; Morrison, J.; Grove, M. Quality and safety in construction: Creating a no-harm environment. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 05016006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbu, C. Knowledge production and capabilities—Their importance and challenges for construction organisations in China. J. Technol. Manag. China 2006, 1, 304–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, G.H.; Dainty, A.R.; Millett, S.J.; Neale, R.H. Client-led strategies for construction supply chain improvement. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2004, 22, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraagen, J.M. How experts solve a novel problem in experimental design. Cogn. Sci. 1993, 17, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, P.E.; Li, H.; Irani, Z.; Faniran, O. Total quality management and the learning organization: A dialogue for change in construction. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2000, 18, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, J.B.H.; Toh, H.M. Investigating the principal factors impacting knowledge management implementation in construction organisations. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2020, 18, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.H.; Long, L.D. Project scheduling with time, cost and risk trade-off using adaptive multiple objective differential evolution. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2018, 25, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Xie, Q.X.; Xia, B.; Bridge, A.J. Impact of Design Risk on the Performance of Design-Build Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143, 04017010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, A.S.; Ab Razak, M.A.; Abd Shukor, A.S. Identification of Factors Influencing Time and Cost Risks in Highway Construction Projects. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Xu, X.; Shen, G.Q.; Fan, C.; Li, X.; Hong, J.K. A model for simulating schedule risks in prefabrication housing production: A case study of six-day cycle assembly activities in Hong Kong. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.J.; Power, D. Innovative knowledge sharing, supply chain integration and firm performance of Australian manufacturing firms. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 6416–6433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S.; Sexton, M.G. Role of knowledge in managing construction project change. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2009, 16, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.N.; Islam, N. Knowledge Transfer from International Consultants to Local Partners: An Empirical Study of Metro Construction Projects in Vietnam. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. (IJKM) 2018, 14, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiewiora, A.; Murphy, G. Unpacking ‘lessons learned’: Investigating failures and considering alternative solutions. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2017, 13, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aragao, R.R.; El-Diraby, T.E. Using network analytics to capture knowledge: Three cases in collaborative energy-oriented planning for oil and gas facilities. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 1429–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.C.; Carrillo, P.M.; Anumba, C.J. Case Study of Knowledge Management Implementation in a Medium-Sized Construction Sector Firm. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, S.; Whitty, S.J. Developing a systemic lessons learned knowledge model for organisational learning through projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Method | Data Collection | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case study | Interviews, observations, and document analysis | BIM adoption extended project duration and increased project costs. Organizational restructuring was required for effective BIM implementation. |

| Literature review and qualitative case study | Case study data obtained from road construction projects | Selection of construction materials in the preliminary design phase can be based on economic performance using life cycle costing. |

| Quantitative | Survey questionnaire disseminated to stakeholders in construction projects | Variation orders and claims or disputes exert a direct effect on project performance, which, in turn, influences shareholder performance. |

| Quantitative | Questionnaire survey from professionals involved in public construction works management | Certain behavioral dimensions of planning function management significantly impact management effectiveness in public construction works. |

| Quantitative | Survey questionnaire from practitioners involved in EPC projects | Human resource development positively affects human resource competency, job performance, and project success in EPC projects. |

| Mixed method | Survey; semi-structured interviews | Critical causative factors for construction project failure in Vietnam include poor project planning, lack of experience, design changes, and financial capacity issues. |

| Literature review | Analysis of research on construction projects | Variation orders exert a significant impact on project performance and indirect effects on shareholder performance. |

| Quantitative questionnaire survey with BIM users | Questionnaire survey with BIM users | BIM-related factors, especially external factors, exert a significant impact on construction project performance. |

| Quantitative | Survey distributed to project managers | Critical factors impacting construction labor productivity include construction management ability, financial status, work discipline, and resource availability. |

| Quantitative | Survey questionnaire conducted with construction projects | Disputes in the Vietnamese construction industry arise from factors such as the diversity of working styles, reluctance to work, and poor teamwork. |

| Qualitative | Semi-structured interviews with professionals and validation with consultancy construction experts | The developed KM model enables construction design consulting companies to enhance design performance and decision-making. |

| Quantitative | Survey with project management professionals | Project managers’ soft skills significantly contribute to project success factors and overall project success. |

| # | Stakeholder Type | Designation | Industry | Qualification | Experience [Years] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Client | Project Manager | Construction | Undergraduate | 11–15 |

| P2 | Chief Financial Officer | Label Stock and Adhesive Manufacturer | Master’s | 11–15 | |

| P3 | Program Manager | Construction | Master’s | 16–20 | |

| P4 | Project Coordinator | Higher Education | Master’s | 16–20 | |

| P5 | Director Property and Operations | Higher Education | Master’s | 16–20 | |

| P6 | Contractor | Managing Director | Construction | Undergraduate | 16–20 |

| P7 | Managing Director | Construction | Master’s | 16–20 | |

| P8 | Project Director | Construction | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P9 | Project Coordinator | Technical/Engineering | Undergraduate | 16–20 | |

| P10 | Project Manager | Technical/Engineering | High School Diploma | 21–25 | |

| P11 | Design and Consulting | Project Director | Construction | Undergraduate | 16–20 |

| P12 | Senior Business Development Manager | Technical/Engineering | Undergraduate | 7–10 | |

| P13 | Project Manager | Construction | Master’s | 7–10 | |

| P14 | Program Manager | Construction | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P15 | Program Manager | Construction | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P16 | Subcontractor | Program Manager | Glass/Facade Installation | Master’s | 11–15 |

| P17 | Project Supervisor | Technical/Engineering | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P18 | Program Manager | Pile Construction and Consulting | Undergraduate | 16–20 | |

| P19 | Assistant Chief Engineer | Electrical | Undergraduate | 7–10 | |

| P20 | Director | Ceramic, Porcelain Tiles | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P21 | Supplier | Supply Manager | Cement Manufacturing | Master’s | 11–15 |

| P22 | Supply Manager | Ceramic Tiles/Flooring | Master’s | 21–25 | |

| P23 | Sales Manager | Furniture | Master’s | 11–15 | |

| P24 | Supply Manager | Furniture | Undergraduate | 11–15 | |

| P25 | Supply Manager | Textile and Fabric | Undergraduate | 11–15 |

| Theme | Sub Theme | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Design changes | Poor requirements’ understanding | ‘Design teams exhibit poor understanding’ (P1, P2, P5). ‘Project manager offering limited perspective’ (P3). |

| Market-driven changes | ‘Clients often change requirements due to market pressures or concepts promoted by their head offices’ (P9). ‘New standards on sustainability requires the construction companies to comply with these requirements’ (P21). | |

| Cost and time issues | ‘Design changes can be costly and lead to project extensiboonons, impacting time and cost’ (P7). ‘The rapid attention and early identification of design changes can essentially mitigate their impact on project performance’ (P6). | |

| Supply delays | Material quality issues | ‘Steel failed the test and needed replacement’ (P12). ‘The exit cover quality was still inconsistent; therefore, we had to send it back to the factory’ (P3). |

| Material supply issues | ‘Often, a problem related to material delivery is due to materials’ shortage’ (P15). ‘Sometimes, they cannot meet a client’s demand for an earlier delivery date’ (P22). | |

| Material substitution | ‘Replace materials to cut costs’ (P24). ‘COVID compelled firms to purchase from the local market’ (P21). | |

| Safety-related incidents | Safety guidelines and equipment | ‘Large organizations possess safety guidelines and safety equipment on site’ (P7). ‘Human safety is paramount’ (P11). ‘Weak safety measures are key issues in local companies’ (P14). |

| Safety supervision and preparedness | ‘Large-scale projects are usually supervised by foreigners; however, accidents still occur’ (P18). ‘Human attitude is a key factor for safety incidents‘‘No one was ready to manage the issue’ (P12). ‘This organization comprehensively utilizes methods to avoid such accidents through the application of preventative measures’ (P16). | |

| Compliance and safety training | ‘The enforcement of rules is lax; in Vietnamese projects, the fine is not significant’ (P10). ‘Workers exhibit no serious attitude on safety’ (P2). ‘Companies and staff must comply, and compliance should be enforced through ‘punishment and penalties’ (P5). | |

| Poor workmanship | Insufficient training | ‘In rural areas, they [Workers] often exhibit no construction background’ (P13). ‘… heavily relies on consultants for crafting project requirements’ (P11). |

| Descriptions | Clients | Consultants | Contractors | Sub-Contractors | Suppliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training or international visits | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Computer-based platforms | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Discussions/meetings | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Documents or reports | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Emails | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Social messaging apps | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Database | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ulhaq, I.; Maqsood, T.; Khalfan, M.; Le, T.; Rauf, A. Investigating Stakeholder Perspectives on the Knowledge Management of Construction Projects: A Case Study of the Vietnamese Construction Industry. Buildings 2023, 13, 2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112745

Ulhaq I, Maqsood T, Khalfan M, Le T, Rauf A. Investigating Stakeholder Perspectives on the Knowledge Management of Construction Projects: A Case Study of the Vietnamese Construction Industry. Buildings. 2023; 13(11):2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112745

Chicago/Turabian StyleUlhaq, Irfan, Tayyab Maqsood, Malik Khalfan, Tiendung Le, and Abdul Rauf. 2023. "Investigating Stakeholder Perspectives on the Knowledge Management of Construction Projects: A Case Study of the Vietnamese Construction Industry" Buildings 13, no. 11: 2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112745

APA StyleUlhaq, I., Maqsood, T., Khalfan, M., Le, T., & Rauf, A. (2023). Investigating Stakeholder Perspectives on the Knowledge Management of Construction Projects: A Case Study of the Vietnamese Construction Industry. Buildings, 13(11), 2745. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13112745