Abstract

Dwelling is very much related to time. A home shields the dweller from outsiders yet, provides an opportunity to engage with the outside world. However, the time required for household chores tends to hinder this engagement, especially for women. Interestingly, co-housing projects tend to rationalise housing and mutualise time-consuming tasks, freeing up time to and thus emancipating and empowering inhabitants. This argument was put to the test in a field study in Brussels. Through a gendered perspective, the research questions and tries to identify which levers ease domestic drudgery in co-housing projects. Spatial analyses coupled with qualitative observations and interviews were carried out in two co-housing projects. The issue of freeing up time through co-housing seems particularly relevant to various categories of people. First, it addresses gender inequalities regarding an egalitarian sharing of household chores. Second, individual (divorced, elderly, or single) households could also benefit from these time savings. Understanding co-housing within this emancipating perspective could be a lever to influence future policy making and incentives.

1. Introduction

A few years ago, while we were carrying out research on Swiss cooperatives, it became apparent that co-housing eased residents’ domestic workload. Young parents, particularly mothers, testified the relief from which they could benefit in raising children in a collective environment while elderly people could organise help for their companions or themselves through the use of communal spaces and shared services. The benevolence of space, the possible mutualisation of chores and the role of an alternative dwelling governance seemed to be essential keys to questioning the traditional distribution of domestic chores. While usually trapped in care roles linked to gender, age or life circumstances, women, the elderly and single parents were able, through co-housing, to emancipate themselves and have more time to develop other activities. Indeed, freeing up time from the traditional domestic chores helps empower people in other spheres of life (work, community, political, etc.) and in the overall social realm.

This influence of co-housing on the traditional distribution of domestic work has led to this particular research. Although the literature has addressed the subject in the past [1,2,3], there has been very little research on the topic in contemporary projects [4]. Additionally, the gender perspective was usually addressed in the case of older projects set in cultural contexts—Scandinavian—where advances in feminism have been more consistent [5]. Eventually, when gender studies show interest in spatial issues, it is usually at the scale of public space, with little research on the domestic scale [6,7,8]. The current pandemic has reminded us that the domestic realm remains at the centre of gender inequalities [9].

Beyond this significance, there were at least “two other good reasons to question dwelling norms and domestic workload” [10]: the increasing interest in co-housing and the growing demographics of one-person and single-parent households struggling under domestic drudgery. Indeed, it appeared that the potential solidarity developed in co-housing projects could yield benefits for other, more vulnerable, households unable to rely either on extended families or institutional support.

Hence, to contribute to the knowledge on co-housing and its possible effects on the gender-division of housework, this paper intends to look into contemporary co-housing projects in Brussels. This contribution addresses one main question —Does co-housing relieve from domestic drudgery? —and two corollary questions are posed —Does co-housing provide for a better gender balance in household chores? What spatial and social features provide this relief?

Following this introduction, the section ‘Domestic Drudgery, Gender Inequalities and Co-Housing’ starts by defining reproductive work in relation to other types of labour and the incidence of gender in reproductive work distribution. Additionally, an understanding of co-housing is provided through a particular focus on one of its driving forces: gender equality in the domestic workload. The following section restates the research question, formulates the research hypotheses and stipulates the research methodology which results in a qualitative research at the crossroads of architecture and social sciences. The section ‘Dwelling Management in co-Housing’ reveals the results of the research in terms of space and time management amongst co-housing residents. The ‘Discussion’ section triangulates the findings around three themes: the opposition of circular and linear time, the visibility of household chores and the mutualisation of reproductive work. Finally, the ‘Conclusions’ section presents a set of reflections and questions for further research.

2. Domestic Drudgery, Gender Inequalities and Co-Housing

To introduce the research question, the notion of housework is considered from the perspective of the various roles all humans are given, and in particular their mediation in relation to gender. Additionally, the understanding of co-housing is expounded and the concept is examined as a means to reconsider housework.

2.1. Dwelling: Reconciling Roles and Gender Inequalities

If space is commonly regarded as the central element of a dwelling, it is inseparable from time [11]. Time is an inherent aspect of addressing any dwelling’s daily and long-term challenges, from the dwelling’s conception to planning for the future.

Feminists including Margaret Benston and Peggy Morton have developed a three-fold definition of time [12], expanding on the division between unproductive and productive labour. This definition was adopted by Moser and the Harvard Institute of International Development. According to them, everyone in society has three roles relating to different timescales. The first role is the reproductive one, “the childbearing and rearing responsibilities” [12]. It includes all the necessary labour to ensure biological maintenance and reproduction (giving birth and raising children), social reproduction (care and maintenance of the labour force) and care for the older generation. This labour takes place in the domestic sphere and embraces the following: meal preparation, dish washing, cleaning, laundry, hygiene care, shopping, family organization and childcare, clothing, domestic administration, etc. The second role is related to productive work. It comprises labour performed for payment in kind or cash. This kind of labour encompasses paid work, work in vegetable gardens, exchanges of services, etc. The third role is the social—‘community managing’—role. It includes activities ensuring social cohesion. This role is assumed by public authorities, groups or individuals when expressing themselves as a citizens. This role involves participation in neighbourhood committees, leisure activities, school, unions, associations, political activities, etc.

This three-fold division of work and timescale stems from feminist theories in response to classical political economy theories that consider market-related activities directly valuable. The feminist vision, however, considers domestic and social work as work in its own right, even if it is unpaid and mostly imperceptible. Therefore, housing can also be considered a (house)work space.

The coexistence of these three roles and their temporalities can be detrimental to one another. This difficult cohabitation—‘conciliation’ [13]—plays a fundamental role in dwelling issues. Conciliation seeks to find “the optimum balance in the dialectics of production (work) and reproduction (care)” [14]. This conciliation is generally harder to deal with for the most vulnerable and for women in particular. Indeed, numerous studies have shown recurring discrepancies in the proportions of reproductive work carried out by men and women [2,15,16,17,18,19] engendering gruelling conciliations for women. This inequality regarding conciliation “refers to the distribution of roles and work assigned to women and men, based on “gender roles” and not on the capacities and aptitudes of each person” [20].

2.2. Co-Housing, a Means to Reconsider Reproductive Work?

Co-housing can be defined as “self-managed collective housing” [21,22]. In contrast with traditional housing developers [23,24], co-housing features bottom-up participatory procedures, leading to ‘demand-driven’ housing [25]. This phenomenon fits into a general trend of decentralisation [21] from a welfare society and its conventional ways of living [26].

Among the tendencies to depart from traditional ways of living, relieving spouses from household burdens and gender equality in domestic workload has been one of the driving forces behind co-housing ever since it first emerged [1,2,10]. Two kinds of approaches are adopted in the co-housing projects analysed by Vestbro and Horelli, embodying the two tactics—‘practical and strategic’—deployed to fight gender inequalities [12].

First, practical answers responded to immediate needs. They were sought to reduce overall domestic workload. While modernist architects worked on ergonomics, efficient household appliances and the reduction of internal displacements in the dwelling, the first co-housing models, based on material feminism, tried to radically reduce housework for women, via externalisation [2]. This led to models where kitchenless dwellings were supplied via a central kitchen (e.g., the Kollektivhus by Markelius in Stockholm, Sweden). The idea was to relieve housework by outsourcing it, generally to other, immigrant, women [3]. These practical answers eased the domestic burden for some, privileged, women without, however, modifying domestic gender roles.

Second, strategic answers were developed, promoting an equal share of domestic chores to make them easier and “more enjoyable through collective activity rather than by outsourcing them to other women as a function of “rational life” efficiency and convenience” [27]. In this case, household chores were reduced by mutualisation (e.g., the BIG, Bo i Gemenskap, living in community, model) or a better distribution of chores within the domestic sphere itself. Strategic answers provided genuine levers to modify gender inequalities in society, easing the burden of conciliation.

3. Methodology: Co-Housing Survey through Cross-Disciplinary Study

Based on these concepts and previous findings, the present research investigates if co-housing does indeed reconsider reproductive work division and gender bias as well as the spatial and social levers to do so. It focuses on the “meaning of the “natural” and invisible activities often defined by the dominant culture as trivial” [14] and explores which features ease or redistribute those activities. In order to assess this issue, the research focuses on the reproduction role in co-housing in terms of time and space.

3.1. Research Scope

Three criteria were chosen to delineate this research. First, the research is carried out in Brussels where housing production has become a central issue over the past two decades. While the demand for housing has increased in Brussels, accessible real estate has dramatically shrunk, affecting directly the middle and lower classes [28]. Moreover, social inequalities have increased, especially in the area of the so-called ‘poor crescent’ along the Charleroi-Antwerp canal. Finally, the city’s sociological structures have evolved considerably with the emergence of a great diversity of households [29]. In this context, alternative governing modes have appeared at the scales of the city, neighbourhood and housing. Regarding housing, collaborative experiences have arisen in the middle class and new forms of co-housing are tested mostly in the private but also in the social sector (i.e., Community Land Trust Brussels) [30].

Second, the research focuses primarily on private, self-promoted co-housing projects displaying shared spaces and amenities as well as alternative modes of governance. As mentioned above, these projects are led by middle-class groups.

Third, the research focuses on the gender distribution of reproductive work. It relies on the fact that gender has an effect on the time spent on domestic chores within housing. Hence, co-housing residents are considered in their use of space and time according to their gender.

3.2. Co-Housing in Brussels

In order to evaluate the effect of co-housing on domestic workload, two case studies were selected following the aforementioned criteria. As a first step, a survey of the co-housing projects in Brussels was made, generating a specific cartography and collating general data and literature about the projects.

Co-housing is a new trend in Brussels and its impact remains limited in terms of numbers [30]. However, the phenomenon has been widely publicised in mass media and among housing researchers.

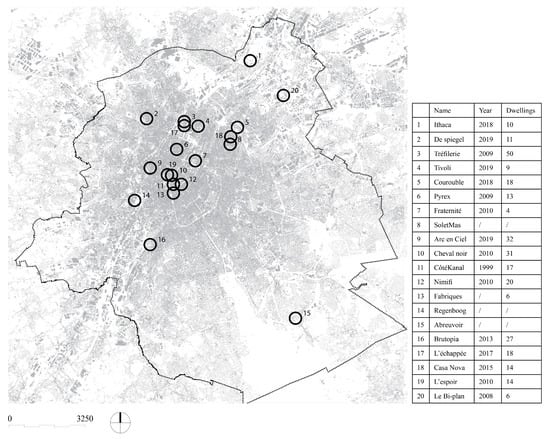

According to the census elaborated by Habitat et Participation (Co-housing projects listed under the name ‘habitat groupé’, https://www.habitat-groupe.be/liste-habitats-alternatifs/) and Samenhuizen (The inventory was carried out in 2018, https://www.samenhuizen.be/samenhuizen-cijfers, accessed on 11 June 2019), there are approximately 20 co-housing projects in Brussels today (Figure 1). They range from containing four to 50 units and the oldest one, côtéKaNaL, was built in 1999 [31], and several projects are currently under construction. The Brussels region is a limited political territory which is almost completely covered by built structures. Hence, all projects are located in a dense urban context. In most cases, it was a deliberate choice from the co-housing group to remain within the city in a quest for sustainability, particularly in terms of (soft) mobility.

Figure 1.

Co-housing projects in the Brussels-Capital region (drawn by the authors, 2019).

From this initial spatial survey, two projects—Casa Nova and L’Echappée—were selected. They were chosen according to several criteria: their recent implementation (2015 and 2017); their average size (14 and 18 dwellings), large enough to accommodate a variety of residents; the presence of common spaces that were financed by the cohousing residents; the individual dwelling layouts that were defined directly by each household; the availability of the households to take part in the research; and the self-development of the project (self-financed and self-managed without any external support, as is the case for Community Land Trust Brussels projects, for example).

3.3. A Cross-Disciplinary Study

Given the fact that time and space management influences both social and spatial dwelling constituents, a cross-disciplinary qualitative research was set up and conducted by scholars in architecture and humanities.

The analysis methodology was two-fold. From an architectural point of view, the co-housing projects were studied by means of a typo-morphological analysis (space proportion, hierarchy, spatial relations, composition, etc.). For this purpose, all projects were redrawn with the same graphic codes in order to compare them objectively. In addition to this typo-morphological analysis, interviews were carried out with the projects’ architects and the urban planners in order to comprehend their attitude regarding housing.

From a social point of view, the projects were the subject of several in-depth visits. These visits allowed the researchers to make field observations as well as conduct interviews based on the ‘comprehensive approach’ [32] with inhabitants.

The recruitment of the interviewees (as discussed with the residents prior to the interviews, inhabitants’ real names have been modified) was organised by sending an e-mail to the general address of both co-housing’s general email. Those who volunteered to participate contacted the researchers to receive information on the research theme and the interview process. Those who participated in the survey were interested in examining their dwelling through the lens of gender. Indeed, to this day, in the two case studies, no comprehensive reflection on this issue has been carried out and there is no specific working group within the co-housing projects devoted to gender equality. Only couples with children responded positively to our call. In both co-housing projects, households with children formed the majority of residents (in Casa Nova, 13 households out of 14 have children, while in L’Echappée, it is 13 out of 18). Additionally, all respondents had young children and were in their late 30s or early 40s, an age when reproductive work weighs most heavily on households. In all situations, both parents declared to be working either full-time or part-time. Furthermore, most residents admitted to being on the left-green side of the political spectrum. It is worth noting that residents who accepted to take part in the interviews were usually the most involved in the collective dynamics of the co-housing projects.

As of this writing, 13 in-depth interviews have been conducted with residents of both projects. These interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes and were conducted in the dwellings or in the collective spaces according to a semi-directive interview guide. The investigations were conducted with couples, but the interviews were organised separately between men and women, and as much as possible in non-mixed groups (non-mixing is a tactic used within various movements for the recognition of the social rights of minorities. It aims to free the voice of the oppressed (originally African-Americans) and to give everyone confidence in their ability to describe the specificities of their daily lives in order to formulate demands specific to their needs (women, LGBTIQ+, indigenous peoples, etc.)). This choice was made to ensure that the story of one of the household members did not prevail and that everyone could express their experiences independently in an autonomous way, in an atmosphere of mutual trust without judgment. The interview guide was divided in four sections focusing on reproductive roles: space management in the domestic and collective spheres as well as time management in the long and short term. During each interview, the respondents were asked to draw a plan of their home and to evaluate the organisation of their activities in the different dwelling spaces, whether private or collective. The ‘time budget’ method [33] was used to account for the activities of each person for each day of the week and the distribution between the different reproductive, productive and social/community roles.

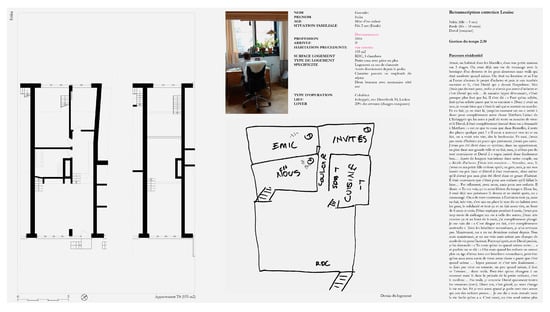

The outcomes of the research were reported in a catalogue combining spatial analysis and post-occupancy evaluation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Catalogue sample.

4. Dwelling Management in Co-Housing

To address reproductive work in co-housing, residents’ space and time management were evaluated in both projects. In line with the research objectives, two elements received particular attention: The shared co-housing spaces in relation to the private dwellings, and the gender division of reproductive work.

4.1. Space Management

As mentioned in the methods section, two projects were selected to address the research question. While similar in terms of size, they differ in their relation to the most emblematic collective space: the shared garden. Further to a description of both projects, their layouts were examined in terms of conception procedure and spatial composition.

4.1.1. Project Descriptions

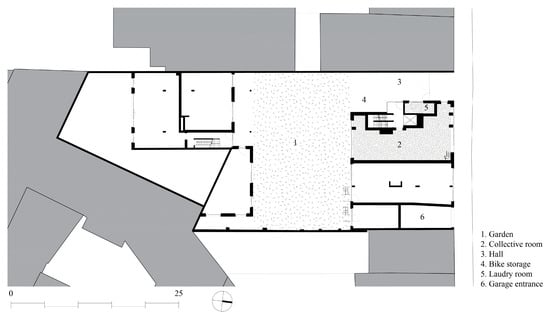

L’Echappée, designed by Stekke + Fraas, was built in Laeken in 2017. It is built around a central garden on which all 18 dwellings have a direct view. Sometimes, this relationship is very direct, as is the case for the ground floor units whose entrances and main windows overlook the garden. The project displays, in addition to the garden, a series of shared spaces: collective room, laundry, bike storage, workshop and, soon, a vegetable garden on one of the flat roofs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

L’Echappée, ground floor—shared spaces (drawn by the authors, 2019).

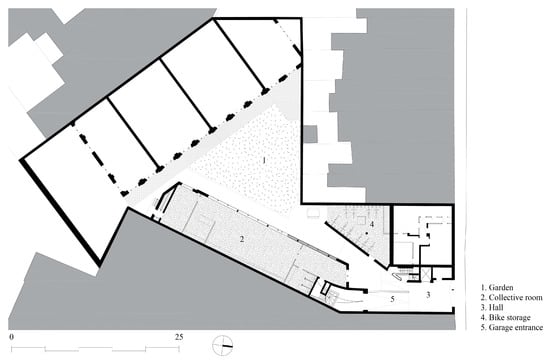

Casa Nova was built in 2015 by Accarain-Bouillot architects. In this particular co-housing project, the garden is semi central, creating a hinge between four dwellings in an old theatre building and ten apartments in a new building on the street side. The garden borders the four theatre-units, but not the street-apartments. The garden is complemented by a bike storage and a large collective passageway leading to a garage. The collective room is not used much for the moment, as it is not yet finished (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Casa Nova, ground floor—shared spaces (drawn by the authors, 2019).

4.1.2. Spatial Layouts

In both projects, a major conception difference occurred between the designs of the collective and the private realms. While the general schemes were considered as a whole, the domestic layouts in both projects were designed on an identical principle: individual arrangements were made possible within an enclosed structural work provided by the project architects.

This attitude led to two different dynamics when deciding on the layouts of the collective and the private spaces. On the one hand, the discussions about the general scheme and the collective spaces were held collectively and required unanimous agreement. On the other hand, the decisions about the dwellings themselves were made by the households. Interestingly, the private layouts remain mostly conventional with a few exceptions, similar to what can be noted in other co-housing projects [34]. They have a traditional day-night division, with gathering the parents’ and children’s bedrooms on one side and the daytime functions on the other side.

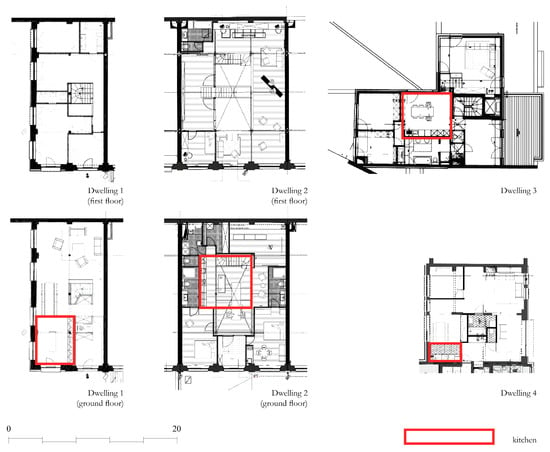

Additionally, despite differences between the individual dwellings, a recurring trait was the proportions of spaces dedicated to daily functions, which are consistently greater than those in traditional dwellings. Within these spaces, the kitchen area has particular importance (Figure 5). It is often perceived by the residents as the hinge and the most frequented space of the dwelling. In all the visited apartments, the kitchens are open, large and brightly lit. Contrarily, the bedrooms are usually minimally designed, conforming to the Brussels’ standards of 14 m2 for the parents’ bedroom and 9 to 12 m2 for the children’s [35]. This spatial disposition does not allow, as many residents testified, for many activities to take place in the bedrooms apart from sleeping.

Figure 5.

Casa Nova apartments, kitchen position (drawn by the authors, 2019).

4.2. Time Management

In terms of time organisation, two particular spans were assessed, bringing to light two different distribution of tasks: decisions concerning the long-term and day-to-day household management. In both cases, significant differences could be noticed between private and collective spaces.

4.2.1. Organising Dwelling for the Long Term

In any dwelling, time can be managed over the long run and on a day-to-day basis. Managing decisions concerning the long-term involves the pivotal moments in the dwelling process: elaborating a housing project, moving in or out, etc. In terms of long-term decisions, differences appear between the private sphere and the collective one.

Regarding the private realm, most residents speak of moments of transition in life regarding their choice to move into the projects: arrival (mostly) or departure of children, retirement, ageing, etc. These moments usually trigger reflection on the household equilibrium and ways to adjust to changes. Similarly, when asked if they could move out of the co-housing project, residents generally argue that they might do so if their “household composition was to evolve” (Sébastien). The first results tend to show that the decision of moving into the co-housing project – when it was not a co-decision – was predominantly taken by men (Sébastien, François, Frédéric). Sometimes, their partners even opposed the decision before complying with their spouses’ opinion. In addition to these housing decisions, men are also mostly in charge of the couple’s long-term contracts (car or home insurance, etc.).

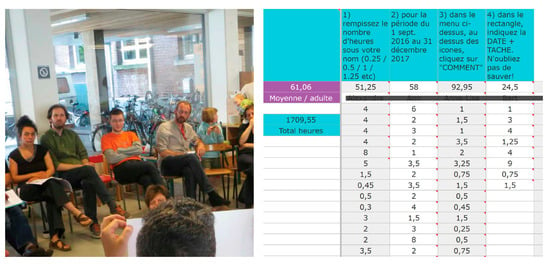

Regarding the collective realm, the elaboration process of the co-housing projects was long. It required money, time and the ability to plan ahead. It took seven years for Casa Nova to be implemented, while the process of l’Echappée took almost ten years. The residents repeatedly referred to the time needed to set up the project as an “investment” (Nadine, Cécile) – an investment they would recoup by living in the project. Sometimes, in the case of l’Echappée for instance, this time investment was even monetised: each member of the community had to contribute up to 100 h of work per year per dwelling, recorded on an online timesheet (Figure 6). Those who did not contribute to that total had to pay a certain amount of money (2% of the unit price for every 100 h). Interestingly, all residents said that everyone had an equal role in the elaboration of the co-housing projects.

Figure 6.

Project elaboration meeting and timesheet (http://www.echappee.collectifs.net, accessed on 11 June 2019, source: Matthieu Liétart, 2013).

In conclusion, the time devoted to the household’s pivotal moments is rather linear, evolving from one stage of life to another. In the case studies, it is commonly a time dominated by men for private matters but generally shared regarding co-housing decisions.

4.2.2. Managing the Dwelling on a Day-to-Day Basis

While long-term decisions relate to linear time, domestic timeis rather cyclic. To illustrate this, the domestic workload in the case studies is summarised in Table 1, displaying whether the chore is carried out in the private or collective realm, who takes care of the chore and the resident’s impression about the chore, where the chore takes place and how that space is defined.

Table 1.

Household chore distribution between collective and individual spaces (elaborated by the authors, 2019).

Three particular chores are illustrative of the workload equilibrium in the two case studies: cooking, laundry and childcare. One of their distinctive aspects is that they are carried out in both the private and the collective spheres. Moreover, these chores display the greatest differences in terms of gender repartition (division of labour between men and women in the households) and possible mutualisation (collective way of organising daily life, where the burdens of different households are pooled and then distributed with the aim of reducing the time spent on reproductive work).

Cooking is generally the first chore all households refer to in the interviews.

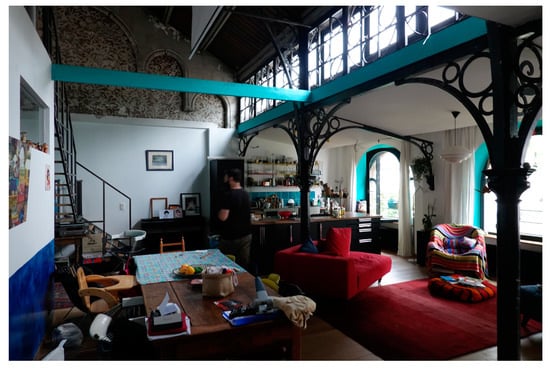

In the private sphere, it is usually a specialised chore: one of the household members takes care of it “because he enjoys cooking and does it faster” (Nadine). However, despite this specialisation, which can be the prerogative of either spouse, there is a recurring difference between the daily meals prepared by women and the exceptional meals prepared by men: “He does more extravagant meals while I do the day-to-day basics” (Sylvie). In addition, whoever is in charge of the cooking has no real impact on who takes care of washing up, tidying and putting the dishes away, which is, analyses show, a chore more often performed by women. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the central and open kitchens play an important role by literally staging the household chore (Figure 5 and Figure 7). The kitchen space itself is no longer devoted only to preparing meals but is also a socialising space where “I can have a drink with friends while preparing dinner” (François). Sometimes, this social function of the kitchen is reinforced by the fact that it relates directly to the circulation space or, at times, because it offers an additional function, such as a child’s swing in one of the apartments (Sébastien and Cécile). With the openness and emphasis significance of the kitchen space, cooking has become socially accepted as an interesting activity by some segments of the population. Overall, when men instead of women cook, it tends to be more visible.

Figure 7.

François and Nadine’s open kitchen (photo by the authors, 2019).

In the collective sphere, cooking happens in a variety of formats. In both co-housing projects, households take turns preparing a once weekly meal for the entire community. L’Echappée residents also organise a weekly auberge espagnole where they eat together in the collective room. While often ‘dreaded’ by the people in charge, these collective meals are a welcome relief to the other residents. This mutualisation principle of cooking is expanded further by sharing kitchen appliances (fridge, barbecue, raclette grill, ice cream maker, etc.), saving time and money for all. Interestingly, if cooking is highly visible in the private sphere, it is even more so in the collective realm, for several reasons. First of all, the menus are widely advertised (emails, notice boards) amongst the community. In this respect, some residents tend to show off their skills. Second, it is a social moment when the community comes together to collect the meals or eat together when possible. Third, in the case of the auberge espagnole, the meals are shared in the collective hall (Figure 8) or in the garden. Once again, the workload is either shared or performed by men.

Figure 8.

Community dinner in the collective room (http://www.echappee.collectifs.net, accessed on 11 June 2019).

Childcare is another demanding chore, and, for many, it was central to the decision-making of living in a co-housing project. “We wanted to take care of our children and, in the co-housing, we really found the solution…I didn’t want too much babysitting in our lives because I had too much…if Basile goes to the neighbours there, it’s almost family. So for me in fact, on a sentimental level too, I am very free from the fear that my children will be alone with people I don’t know. I never have that feeling and that, for me, is one of the best comforts in terms of mental load” (Nadine).

In the private sphere, this workload is usually said to be equally distributed. However, when describing the chores themselves and their related timeframes, a genuine distinction appears. Indeed, there is an equal share in waking children or putting them to bed as well as conveying them to school or kindergarten, but it is less equal regarding bathing, clothing and preparing schoolbags, which are done mainly by women. Hence, similar to cooking, the more invisible tasks are taken care of by women.

In the collective sphere, co-housing plays an essential role, as several residents mentioned that “kids are free to run around as they please” (Sylvie); after the children return from school, parents even leaving them “to play in the garden while going back to work” (François). It is not rare to find all of the kids in the community playing until late in the garden or collective room (Figure 9), “making it difficult to bring them back to our places” (Frédéric) and rules must be created among cohabitants to be able manage one’s own children.

Figure 9.

Children gathering in the collective room (source: Matthieu Liétaert, 2018).

Mutualisation plays a major role in child-rearing. Children often eat or bathe at other residents’ places. This mutualisation saves time, but potentially also money. For instance, some female residents organise a clothing chain, passing clothes from an elderly child to another as they grow. Sometimes, mutualisation in childcare is also about giving one another advice, as when some women breastfeed together in the central garden. While this knowledge exchange is random, children-oriented working groups are set up to teach explicit educational values to children, addressing citizenship (Casa Nova) or even gender issues (l’Echappée). Children’s mobility, for its part, is seldom shared amongst residents and often left to ‘improvisation’ (Cecile and Sylvie) because, for many, there is a need for another social life outside the co-housing. However, the collective project has a tremendous effect on mobility habits, first, because soft mobility is engraved in the community charters and bicycles are promoted instead of cars, despite the garages that were built at the request of the local authorities; and second because there seems to be implicit pressure among the group to stick to ethical choices. However, sharing cars “does not come as an evidence to share cars, although we thought it would” (Sylvie).

The chores related to laundry reveal a difference between the two projects: Only one has a collective laundry.

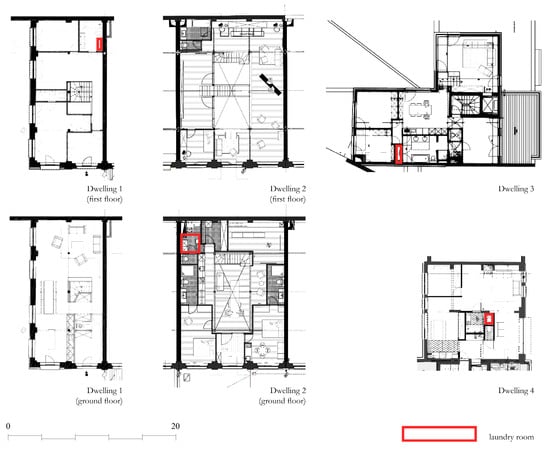

In the private sphere, there is a clear discrepancy between the households’ discourses. While men claim doing laundry to be an egalitarian chore, women believe it is not. This is due to the definition of the chore itself. While men generally speak of washing clothes alone, women associate laundry with a trio of chores: washing, hanging, folding and putting away clothes. If the first chore—washing—is usually shared, the two others remain the prerogative of women, because men do “not fold well” or women “prefer to store the clothes” (Sylvie) themselves. This very invisible chore is thus gender specialised. The spaces where those chores take place are not very enjoyable: the laundry room is often a dark closet or is included in the bathroom (Figure 10). In any case, no side activities are possible. They are often designed as the residual spaces in the dwellings’ floor plans. Folding laundry usually occurs in the bedrooms which are too intimate and, as mentioned above, too small to shelter real social activities.

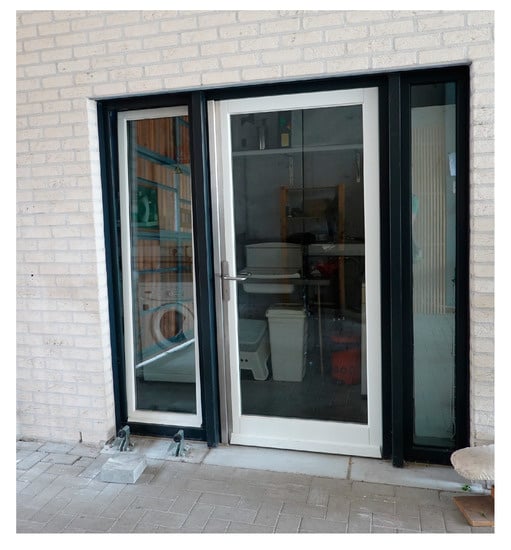

Figure 10.

Laundry rooms (drawings by the authors, 2019).

In the case of l’Echappée, there is a communal laundry room, which is in the main entry hall (Figure 11). Due to its position and glazed façade, it is highly visible to all residents. Interestingly, men tend to take a more active part in the laundry, bringing the laundry to and fro while women fold it and put it away. The very central position of the laundry room in the collective space enables everyone to see who actually takes care of the chore, leading sometimes to disbelief when seeing “that the neighbour does not do the laundry while his wife is a real feminist” (Sébastien). Furthermore, the community also provides an opportunity to exchange clothes (mostly amongst women) or hold a garage sale ofold clothing.

Figure 11.

The communal laundry room in l’Echappée (photo by the authors, 2019).

5. Discussion

The findings of the spatial and social analyses through the lenses of space and time management were triangulated to organise a series of considerations on reproductive work in co-housing projects. First, a reflection was developed on dwelling-related decisions based on their linear or cyclical nature. Then, visibility was developed as a lever to reconsider domestic workload through its potential reward. Finally, mutualisation highlighted how the pooling of household resources can ease housework for everyone.

5.1. Circular versus Linear Time

However innovative the case studies are in terms of housing, the gender-based distribution of private chore duties remains rather traditional. As noted in other research, “While some aspects of domestic social reproduction have changed enormously in the West, there has been remarkably little appetite to reconfigure individual dwelling norms to any equivalent extent” [10]. Whereas men tend to remain responsible for decisions about the long term, women are in charge of daily routine chores. This distribution is closely related to the repetitiveness of the chores. Indeed, women tend to perform the cyclical labour (tidying up, washing up, daily meals, etc.) while men perform the ‘extraordinary’ work, which is more linear (special private or collective meals, administration related to substantial expenditures, etc.).

Co-housing, however, puts this distribution between circular and linear times in question for three reasons. First, decisions concerning the long term of the co-housing project are made by a group, and no longer a duo. Accordingly, all members of the community—including women—are de facto involved in the decision-making process (as such, research could be further developed to analyse whether questions of who speaks, for what duration, for what purpose (e.g. to impose will, assume power), etc. are gendered in collective decision-making processes within co-housing).

Second, work routines attached to the collective spaces have longer cycles than private ones. Hence, being less repetitive, they seem to produce a more equally-shared workload. Moreover, the spectrum of skills embedded in the community unsettles the traditional distribution of chores between men and women. The collective nature of some chores (caring for the communal garden, making repairs, cleaning common spaces, etc.) requires reconsidering habits concerning a gendered division of chores (Figure 12). Indeed, for collective chores, discussions take place to decide on the most appropriate person to be in charge, often creating new role distributions. “Our female neighbour is incredibly good at tinkering and she has all the tools…so she coordinated the heavy works in the collective room and my male neighbour, who is useless at using a drilling machine, ends up cleaning the floor” (Frédéric). In this sense, the number of skilled people challenges the usual specialisation between men and women. Moreover, the collective discussions about these chores result in explicit choices that are often implicitly decided.

Figure 12.

The ‘Minga’ collective working day (http://www.echappee.collectifs.net, accessed on 11 June 2019).

Third, the phenomenon of co-housing is new and cannot rely on traditions. Innovative practices emerge, unsettling conventional patterns (however, it should be noted that the gender issue does not appear in the charters containing the values shared by the groups of inhabitants). Through these inventions, “the patriarchal dwelling patterns may, however, change in a public or semi-public context, such as the shared spaces, where the modes of action and distribution of space and time are conducive to the integration of genders and generations” [5].

Finally, residents praise the educational value of co-housing as ‘seeing the others operate questions your own ways of living’. Many testify that it has an influence on their lives. Other studies displayed similar findings, showing how “the time each household has spent in a particular community tends to increase the likelihood of adaptation to the social codes” [10]. The benefits of this mutual influence, however, depends on norms established by the specific group (a strong sustainable background in these case studies, which can be read in the projects’ founding charters).

5.2. Visibility and the Rewarding Value of the Chore

A second finding of the research is that there seems to be greater equality in sharing the workload when it is visible either spatially or through public debate.

In the domestic sphere, as noted in previous studies, the private realm “tends to reproduce existing gender roles” [5]. Visibility seems to play a major role in this distribution. The distinction between the chores of cooking and laundry is very illustrative. The act of cooking, on the one hand, is literally staged by the large and open kitchens. Other chores display a similar visibility, such as making repairs or gardening. Their results are perceptible when touring the dwelling, as one notes the pride in and boasts of having “designed and manufactured this window” (François). These visible chores are generally either shared or the prerogative of men. Laundry, on the other hand, remains a very invisible task within the dwelling. Along with tidying, cleaning and daily administration, laundry occurs in places that are less visible or that leave no distinctive trace. These chores appear to be by far the prerogative of women. In addition to the chores themselves, a fundamental invisible burden should be mentioned here: The mental load. The mental load is the investment in organising and managing the household [36]. It highlights the difference between performing household chores, which can be symmetrical and shared, and the organisational mental effort associated with these tasks. Once again, this workload is generally the burden of women since it is not highly visible and, hence, only marginally debated within households.

Nevertheless, these traditional patterns tend to be challenged by co-housing. Most of the domestic labour carried out in the collective realm displays a more equal distribution or even a traditional gender role inversion. Once again, visibility plays an important role. Indeed, domestic workload in the collective domain can be seen by all community members. Moreover, chore distribution is physically displayed (Excel sheets, chore boards, etc.), leaving little space for explicit gender discrimination (Figure 13). Hence, collective cooking, cleaning, gardening, or transport to school are fairly shared by all members of the community, regardless of gender.

Figure 13.

Making invisible work visible, collective chores (photo by the authors, 2019).

Visibility thus plays an important role in the distribution of chores, whether in the private or the collective realm. A distinction can be made between invisible, “shadow work” [14], considered a burden, and visible tasks that are rewarding for the people doing them. Visibility transmutes the chore by giving it a rewarding value which can be of two kinds.

First, the labour can be socially rewarding due to the value it bears in the social group. While cooking, bringing the children to school or gardening are highly valued in certain groups, other chores are less valued, such as administrative work and doing laundry. This is linked to the community’s social codes, which are often embedded in their founding charter. Eventually, like other cohousing projects, the rewarding value of some chores and their organisation on a communal basis has “had a liberating effect on women’s lives” [3].

Second, a chore’s visibility can lead to an economic reward. In the case of l’Echappée, for instance, the time invested in the project’s implementation phase was monetised. This financial valorisation of domestic workload can be paralleled to feminist demands to allocate a budget to the time spent by women in domestic work [13,15,37] even though this position could lead to women’s confinement to the domestic sphere [38].

In addition to spatial visibility, collective debates play a major role in a chore’s rewarding value. Indeed, as mentioned in other research, the deliberative democracy of co-housing does not tolerate gender inequality [1,34]. Generally, co-housing projects introduce a new governing mode—participatory democracy—based on “non-violent communication, and reciprocal attention and shared responsibility” (l’Echappée charter) and that differs from conventional dwelling practices. In both case studies, the deciding modes are very democratic and visible. Everyone has a chance to express an opinion either through plenary and monthly meetings or through digital means of communication with the group (emails or WhatsApp groups). New communication modes enable new equilibria among residents, who, in turn, acquire new skills for their private or professional lives, such as “non-violent communication that can be used in different contexts” (Frédéric). As a result, residents can no longer argue for tradition and habits; they have to produce valid arguments. Otherwise, their queries may easily be dismissed by the other group members. Hence, impulsive decisions and the usual bilateral domestic wrangling are prevented. Furthermore, through these discussions, some of the mental load related to domestic chores is exposed and can be shared more easily.

However, these new governing modes have a few drawbacks. First, they are slow. If they prevent the group from any “impulsive choices, which can be frustrating at times” (François), they take a lot of time. Some residents even refer to them as a “burden because of an overload of communication…at least four mails a day” (Sylvie) that intrudes on their personal lives. Second, residents refer to their co-housing project as a ‘ghetto’ from which they need to “run away every once in a while” (Nadine).

5.3. Mutualisation and Potential Breathing Space and Gained Time

If co-housing provides visibility that helps redistribute chores, it also provides residents breathing spaces and time for the residents by relieving them from a certain number of chores. Once again, cooking provides a good example of this possible mutualisation, with shared meals or auberge espagnole. However, the phenomenon is especially evident with childcare. Indeed, as admitted by most residents, children are free to wander as they please in co-housing areas. In terms of childcare, the community acts as an extended family in which “everyone keeps an eye on the others’ children”. According to many residents, this transfer of “some of the care and overall reproduction work to the semi-public sphere” [5] creates time to do other things.

Moreover, in terms of breathing spaces, co-housing can also act as a buffer. Indeed, several residents admit using the co-housing dynamic to externalise domestic conflicts. Some spend “at least an hour per week with other residents in the co-housing” (Nadine) to speak about their household problems while others even spend a few days in another’s dwelling to “defuse tensions in their couples” (Vanessa). Hence, family members can spend time outside their dwelling without actually leaving home in an extended sense. Accordingly, several adults find in the co-housing sphere a breathing space that they sometimes miss in their own dwelling. Indeed, spatial analyses and previous studies [5] reveal that several residents, mostly women, do not have a space of their own in their dwelling. Several factors contribute to this problem: the women’s space are not finished, the family desk is used by male partners who “hate it when other members of the family leave stuff on it” (Frédéric), compelling women to telework from the kitchen table, etc. Men, however, generally have a space of their own, whether it is a separate room, desk, coach or even piano.

The research has highlighted several levers that question the distribution of domestic workload or easing household chores altogether. Generally, co-housing contributes to a better balance or reduction of household chores [1]. This was also true in the case studies, in three ways. First, the traditional role distribution between circular and linear time is challenged by the larger group, different time schedules, innovative patterns and educational value of co-housing. Second, the visibility of chores enhances a more equal distribution. This can be the case either through spatial visibility or through public discussions generated by the governing modes of co-housing. Third, co-housing allows for mutualising household chores, creating breathing space and for all residents.

6. Conclusions

A great deal of research deals with gender inequalities in the public space. However, it seems essential to study the signification of gender roles in the domestic sphere as well since it has great political significance [4]. Indeed, quantitative research has shown that “gender segregation in domestic work continues to pose a barrier to gender equality” [39]. Hence, by easing and sharing domestic work as well as enabling the conciliation of the three roles mentioned in this paper, individuals can become more involved in their social and political lives [1,12].

Before concluding, two biases mentioned in the methodology section must be underlined. First, the people who live in the studied co-housing are generally highly educated middle-class people, confirming previous studies’ findings [1,30]. The residents, by their own admission, are on the left/green side of the political spectrum. This has a significant influence on the social codes that are shared by the group, for instance in terms of sustainability or gender equality. Second, both projects are still fairly new and thriving based on the initial dynamics (probably due to the omnipresence of young children). It would be interesting to investigate both projects in a few years to see how the co-housing dynamics evolve.

Nevertheless, preliminary conclusions can be drawn from this research.

First, it is important to emphasise the differences between conventional collective housing and co-housing projects in Brussels. While both share many commonalities, private and public housing estates of the Brussels-Capital Region are organised around by-laws of immovable property that were defined prior to the arrival of the inhabitants. Co-housing projects, however, rely on a charter rather than an internal set of regulations (the charters of L’Echappée and Casa Nova can be found at: https://www.echappee.collectifs.net/?page_id=33; https://habitatcasanova.wordpress.com/la-charte/, accessed on 11 March 2021). The charter is drawn up by the residents themselves and anyone wishing to reside in the co-housing must adhere to it. The charter establishes a set of values and imposes collective management from the start, including participatory democracy, non-violent communication, etc. Such management is organised via monthly official meetings and regular informal discussions between residents. Hence, such gatherings are much more frequent than in conventional collective housing where there is only one mandatory annual general meeting (https://www.lexgo.be/en/papers/civil-law/property-law/new-belgian-property-co-ownership-law-explained,59061.html, accessed on 11 March 2021). As noted above, the benefits of this alternative governance can be traced to the visible nature of collective decisions, which thus tend to be more egalitarian. Moreover, due to a very long preparatory period for drawing up the projects, specific relationships are built within the co-housing communities, creating much more openness compared to traditional neighbourhoods. Signs of this are doors left open (Eva) and private gardens open to all (Hugues). Co-housing becomes a place to socialise: Residents gather for sport activities (yoga classes, jogging, etc.), cinema projections, sewing classes, board games, etc. In these cases, the collective domain does not only offer relief from the household burden but also an option to spend the time gained in social activities.

Furthermore, at the scale of the projects themselves, the major difference is the production of housing ‘by and for’ the residents whereas in collective housing, the decisions are made either by the institutions or private and public/private stakeholders. Therefore, in co-housing, the inhabitants–who themselves created the co-housing–choose to share spaces and services. As demand-driven projects, the spaces tend to respond better to the actual needs of the inhabitants and to empower them [40], as do their governing modes.

In addition to these differences with traditional collective estates, co-housing projects tend to offer short- and long- term possibilities, both contributing to the strategic answers deployed to fight gender inequalities [12].

In terms of short-term impacts, co-housing does seem to challenge the conventional distribution of household chores as well as ease them to some extent through mutualisation. Hence, although the sustainable nature of these dwelling types is often praised, it should be investigated further in terms of residents’ emancipation and of women in particular. If co-housing is a means to redistribute household chores more equally, then the question is: Who could this benefit? The present research was centred on gender inequality regarding reproductive work, but it could also benefit persons who struggle to conciliate reproductive, productive and social roles, such as individuals coping with separation, single parenting, bereavement, etc. In this sense, the co-housing model could help these time-deprived people by generating solidarities that they are unable to find either in extended families or in institutions.

However, as noted by several residents, while there were “a lot of single women with children in the initial group, the project turned out to be too expensive, although it met a real need in terms of managing children” (Nadine). Indeed, nowadays in Brussels, the co-housing model is not affordable for time-deprived people, for several reasons. First, co-housing projects remain unaffordable for low-income and single people. As noted in other co-housing projects, co-housing sale prices are not below market average [41,42]. Second, public policies often advocate for large-dwelling production to maintain the family-based middle class in Brussels. These units are then either too large or too expensive for single persons. Third, studies have shown [30] that social conventions must still be circumvented in some population groups to make co-housing a genuine possibility. Indeed, Lenel’s studies show that those who are most in need of shared spaces yearn for other—more traditional—models. This concerns mainly how individual housing, unlike collective housing, remains a symbol of upward social mobility.

With regards to long-term impacts, the domestic division of roles can also be a key issue when distributing them on an economic and political level, as “it is evident that co-housing has relieved women from some of the extra housework so that they can participate in other activities either in the house or outside it” [1]. Hence, future studies should explore how and to what extent a more equal distribution of domestic workload can contribute to equality in the labour markets and political life. Similarly, social codes and traditions should still be countered, as the research shows that men tend to find it easier than women do to actually enjoy the time they gain from the relief provided by co-housing.

In this fight against social codes, a re-examination of the mental load occupies an important place. Indeed, the research illustrates that this load, generally carried by women in the domestic sphere is usually externalised and shared in the case of communal living. In this regard, co-housing has two distinctive benefits. First, it has an immediate effect regarding collective chores that become communally managed by the entire community instead of by a limited number of people. Second, co-housing, through constant discussion, make this invisible labour much more explicit than in the domestic sphere. This can be a learning experience for easing domestic drudgery.

The potential influence of reduced or better shared housework opens up future research prospects. Indeed, further research could pursue two directions. First, as this research did not focus on how the time spared in co-housing is actually used by inhabitants, it would be interesting to see if the time gained serves social, political or job-related roles. Additionally, further investigation could look into how the features that encourage reconsidering domestic workload could be implemented in other kinds of housing projects.

Author Contributions

Both authors have contributed to the conceptualization, methodology and writing of this paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vestbro, D.U.; Horelli, L. Design for gender equality—The history of cohousing ideas and realities. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sangregorio, I.-L. Collaborative Housing from a Woman’s Perspective. In Living Together: Cohousing Experiences around the World; Vestbro, D.U., Ed.; RIT Division of Urban Studies with Kollektivhus NU: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010; pp. 114–124. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L.; MacGregor, S. Beyond wishful thinking: A FPE perspective on commoning, care, and the promise of co-housing. Int. J. Commons 2019, 13, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horelli, L. The role of shared space for the building and maintenance of community from the gender perspective—A longitudinal case study in a neighbourhood of Helsinki. Soc. Sci. Dir. 2013, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Denèfle, S. Utopies Féministes et Expérimentations Urbaines; Presses universitaires de Rennes: Rennes, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mosconi, N.; Paoletti, M.; Raibaud, Y. Le genre, la ville. Trav. Genre Soc. 2015, 33, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, K. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 16, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, H. Saving space, sharing time: Integrated infrastructures of daily life in cohousing. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salembier, C. Questionner “l’Habiter” en Temps de Transition Post-Communiste: Du Corps au Monde: Parcours Ethnographique des Espaces d’un Quartier Menacé D’expulsion; Université catholique de Louvain: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, C. Gender planning in the third world: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1799–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delphy, C. L’ennemi Principal: Penser le Genre; Éd. Syllepse: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horelli, L.; Vepsä, K. In Search of Supportive Structures for Everyday Life. In Women and the Environment; Altman, I., Churchman, A., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, S. Falling Wall Press and the Power of Women. In Wages against Housework; National Library of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Benería, L.; Sen, G. Class and Gender Inequalities and Women’s Role in Economic Development: Theoretical and Practical Implications. Fem. Stud. 1982, 8, 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, C. A new approach to housing theory: Sex, gender and the domestic economy. Hous. Stud. 1990, 5, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, S.; Gregory, S.; McKie, L. “Doing home”: Patriarchy, caring, and space. Women Stud. Int. Forum 1997, 20, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencarini, L.; Sironi, M. Happiness, Housework and Gender Inequality in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 28, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herla, R. Apports féministes à la critique du travail. In Collectif Contre les Violences Familiales et L’exclusion; CVFE asbl: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L. The re-emergence of self-managed co-housing in Europe: A critical review of co-housing research. Urban Stud. Int. J. Res. Urban Stud. 2016, 2016, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCamant, K.; Durrett, C. Cohousing—A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves; Ten Speed Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchain, P. Construire Ensemble le Grand Ensemble: Habiter Autrement; Actes Sud: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, K. Self Made City; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Geest, J. A generation that is growing up that can’t even share a single facility. In Building Together. The Architecture of Collective Private Commissions. Samen Bouwen. De Architectuur van Het Collectief Particulier Opdrachtgeverschap; Housing, D., Ed.; DASH|Delft Architectural Studies on Housing: Delft, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 8, pp. 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Czischke, D. Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vestbro, D.U. From central kitchen to community cooperation: Development of collective housing in Sweden. Open House Int. 1992, 17, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dessouroux, C.; Bensliman, R.; Bernard, N.; De Laet, S.; Demonty, F.; Marissal, P.; Surkyn, J. Le logement à Bruxelles: Diagnostic et enjeux. Bruss. Stud. 2016, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criekingen, V. ‘Gentrifying the re-urbanisation debate’, not vice versa: The uneven socio-spatial implications of changing transitions to adulthood in Brussels. Popul. Space Place 2010, 16, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenel, E.; Demonty, F.; Schaut, C. Les expériences contemporaines de co-habitat en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale. Bruss. Stud. 2020, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metamorfose Project Team. CôtéKaNaL, L’histoire D’un Achat Collectif; Metamorfose Project Team: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, J.-C. L’entretien Compréhensif; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, J.-C. Casseroles, Amour et Crises. Ce Que Cuisiner Veut Dire; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Horelli, L. Self-planned housing and the reproduction of gender and identity. In Gender and the Built Environment; Ottes, L., Poventud, E., van Schendelen, M., Segond von Banchet, G., Eds.; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Règlement Régional d’Urbanisme. Arrêté du Gouvernement de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale du 21 Novembre 2006; Règlement Régional d’Urbanisme: Région de Bruxelles-Capitale: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haircault, M. La gestionordinairedelavieendeux. Sociol. Travail 1984, 26, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- De la Pena Valdivia, M. Outils de L’approche Genre, Collection; Le Monde selon les femmes: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gorz, A. Métamorphoses du Travail: Quête du Sens. Critique de la Raison Économique; Essais, F., Ed.; Éditions Galilée: Paris, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, M.Y.; Sullivan, O.; Gershuny, J. Gender Convergence in Domestic Work: Discerning the Effects of Interactional and Institutional Barriers from Large-scale Data. Sociology 2011, 45, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledent, G.; Salembier, C.; Vanneste, D. Sustainable Dwelling. Between Spatial Polyvalence and Residents’ Empowerment; Presses Universitaires de Louvain: Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, R.; Minkjan, M. Self-Builds: Between Unruly Real Estate Markets and Failed Housing Policies. In Proceedings of the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1–8 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bresson, S. L’habitat participatif en France: Une alternative sociale à la « crise »? Les Cahiers de Cost 2016, 5, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).