1. Introduction

The 6xxx series aluminum alloys—commonly classified as medium-strength aluminum alloys—are well known for their excellent weldability across a wide range of industrial applications, as well as their corrosion resistance and favorable strength-to-weight ratio [

1]. Owing to their economic advantages over higher-strength alternatives, these alloys have become increasingly preferred for lightweighting applications, particularly in the automotive sector, over the past decade [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Most studies have been conducted on the aging of 6xxx series alloys, particularly 6082 and 6061 alloys. However, there are limited studies on the artificial aging temperature–time–precipitation relationships specifically for EN AW 6056. This relatively less explored alloy stands out among these alloys due to its superior mechanical strength compared to its counterparts [

3,

5]. When subjected to controlled heat treatment processes—including solution heat treatment, quenching, and artificial aging—properties of EN AW 6056 alloys can be further optimized, resulting in improved durability, fatigue resistance, and overall performance [

7,

8,

9].

High strength in heat-treatable 6xxx series aluminum alloys is achieved through precipitation hardening, which involves the precipitation process. This treatment first starts with solution heat treatment process. Especially in Al-Mg-Si alloys, it involves heating the alloy to a high temperature, typically between 500 °C and 560 °C, to dissolve the alloying elements into the aluminum matrix, creating a homogeneous solid solution. After the solution heat treatment, the material is rapidly cooled, typically by immersion in water, to lock the alloying elements in a supersaturated solid solution state (SSSS), a process known as quenching. Following quenching, usually artificial aging treatment is performed at intermediate temperatures, which leads to the formation of nano-sized precipitates, thus enhancing the material’s strength. The nano-sized precipitates that form sequentially during aging in Al-Mg-Si alloys are named β″, β′, and β. Among these precipitates, the β″ phase provides the maximum hardness, while the β phase forms as a result of over-aging and contributes the least to the alloy’s strength. The precipitation sequence can be demonstrated as follows [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]:

Where GP-I zones refer to the coherent and spherical precipitates without an internal order. These zones are precursors of the following needle-shaped β″ precipitates [

2,

13,

18].

The addition of copper in 6xxx series alloys influences the precipitation kinetics and stability, resulting in a more complex precipitation sequence compared to Al-Mg-Si alloys. These alloys, also called Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys, exhibit the formation of semi-coherent (β′ and Q′ precipitates), distinct from the precipitation behavior of the former ones. As the aging process advances and over-aging occurs, these semi-coherent phases transform into stable β and Q precipitates. The precipitation sequence of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys can be demonstrated as follows [

10,

11].

Some studies in the literature have revealed which aging parameters or chemical compositions form metastable precipitates such as L, S, and C in the precipitation sequence of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys. For instance, Torsæter et al. investigated over-aged Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys containing 0.13% Cu, focusing on the intergrowth behavior of these precipitates and their influence on the alloy’s microstructure and properties. Under over-aged conditions, both Q′ and L precipitates were identified within the aluminum matrix, with the Q′ phase exhibiting the chemical composition Al

3.

8Mg

8.

6Si

7.

0Cu

1.

0 [

12].

Ding et al. investigated Al–Mg–Si–(Cu) alloys to evaluate precipitation behavior under various aging conditions, considering different Mg/Si ratios and copper contents. Two of the alloys contained trace levels of copper (0.06%) and had Mg/Si ratios of 0.55 and 2.13. The remaining two alloys contained relatively high copper content (0.50%), with Mg/Si ratios of 0.56 and 2.052, respectively. All workpieces underwent homogenization at 560 °C, followed by hot and cold rolling, solution heat treatment (SHT at 560 °C for 30 min), and water quenching to room temperature. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to natural aging (NA) for up to four weeks, artificial aging (AA) at 180 °C for various durations, or a combination of natural and artificial aging. The naturally aged alloys with higher Si content exhibited greater strength than those with higher Mg content. Under prolonged aging conditions, strength-enhancing lath-shaped L precipitates were observed particularly in alloys containing elevated levels of both Cu and Mg [

19].

In the study conducted by Kairy et al., Al–Mg–Si–(Cu) alloys were subjected to solution heat treatment at 550 °C for 30 min, followed by a 10 s water quench. The artificial aging parameters included an under-aged (UA) condition (20 min at 185 °C), a peak-aged (PA) condition (6 h at 185 °C), and an over-aged (OA) condition (24 h at 185 °C). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses revealed that the precipitate number density in the PA condition increased with rising Si-to-Mg ratios and copper content [

20].

The precipitation kinetics of Al–1.12 Mg2Si–0.35Si (excess Si) and Al–1.07 Mg

2Si–0.33Cu (balanced +Cu) alloys were examined, and the activation energies were determined using the Ozawa, Takhour, Kissinger, and Starink methods based on differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermograms. The results indicated that the alloy with balanced copper content requires lower activation energy for the formation of GP-I zones, β″, β′, and Mg

2Si precipitates [

11].

Recent studies on the precipitation behavior of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys have shown that specific alloying elements play a critical role in the formation and growth of precipitates, thereby significantly influencing the mechanical properties of the material. In one such investigation, solution heat treatment was applied to Al–1.15 Mg

2Si–0.34 Cu–0.21 Cr (balanced) and Al–1.14 Mg

2Si–0.34 Cu–0.21 Cr (excess Si) alloys at 530 °C for 1 h, followed by quenching at 0 °C. DSC analyses were subsequently performed at various heating rates, revealing that the temperatures corresponding to the thermogram peaks varied with heating rate. The thermograms further indicated that the peaks associated with β″ formation became more pronounced in the alloy with higher Si content [

9].

The peaks identified in the DSC thermograms provide insight into the precipitates formed or dissolved during aging. In a recent study, the peak near 80 °C was attributed to the formation of atomic clusters (Mg clusters, Si clusters, and Mg–Si co-clusters). The second peak, observed around 160 °C, corresponded to the formation of the GP-I zone. Subsequent exothermic peaks at approximately 230 °C, 270 °C, and 320 °C were associated with the formation of β″, β′, and Q precipitates, respectively [

10].

Chen et al. investigated the influence of varying copper contents (0.5 ≤ Cu wt.% ≤ 4.5) on the strength and microstructure of aged Al–Mg–Si–(Cu) alloys by examining their effects on precipitation behavior, which plays a decisive role in determining tensile strength and hardness. The alloys underwent homogenization, extrusion, solution heat treatment, and water quenching followed by artificial aging, quenching, and natural aging, respectively. Optical microscopy revealed that, along the extrusion direction, the grain morphology evolved from a pancake-like structure to a more fibrous form as the copper content increased. In the peak-aged alloy containing 0.5 wt.% Cu, β″ precipitates dominated the microstructure. With an increase in Cu content to 1.0 wt.%, the density of β″ precipitates decreased while the density of Q′ precipitates increased, likely due to the effect of copper on Si solubility within the aluminum matrix. In alloys with higher copper levels, a further increase in the density of Q′ precipitates was observed [

21].

Chakrabarti and Laughlin reviewed and synthesized the literature on the precipitation behavior of 6xxx and 2xxx series aluminum alloys, emphasizing the significance of the quaternary Q phase, which frequently dominates the equilibrium precipitate structure. Artificially aged Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys exhibit a four-phase equilibrium field that varies depending on the Cu content and the Mg/Si ratio. Within the Al–Mg–Si–Cu system, the Q phase and the aluminum matrix are common to all four-phase equilibrium fields. When Cu is added to Al–Mg–Si alloys, the θ (CuAl

2) phase becomes part of the equilibrium phase assemblage along with the Q phase. According to the four-phase equilibrium diagram, the critical Cu content required for the formation of these phases ranges between 0.2% and 0.5%, while the threshold Mg/Si ratio is approximately 1.0. The study further highlighted that precursor phases of Q′, influenced by factors such as the Mg/Si ratio and Cu content, also contribute to the mechanical properties of these alloys [

22].

Dehghani and Nekahi employed response surface methodology (RSM) to model and predict the final yield stress and elongation of AA6056 under two-step aging conditions. Unlike previous studies, their work incorporated additional thermomechanical processes, including hot rolling at 450 °C to reduce the thickness to 8 mm, followed by cold rolling to further reduce the thickness to 4 mm. The pre-aging stage was carried out at temperatures of 60, 70, 80, and 90 °C for durations of 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 h. Final aging was then performed at 165 °C for 2, 4, 6, 8, or 10 h. Cold working after pre-aging was used to refine the microstructure prior to the final aging step. The study demonstrated a significant influence of pre-strain on the precipitation behavior of β″ and Q phases during thermomechanical treatment. Specifically, pre-straining promoted the nucleation of β″/Q precipitates along dislocations, while the cold working prior to aging contributed to achieving a more uniform dislocation distribution [

23].

Yin et al. examined the precipitates formed in specimens subjected to pre-straining followed by natural aging under both over-aged and peak-aged conditions. Their results showed that artificial aging after pre-straining led to an increase in hardness, while the pre-straining itself did not alter the precipitation sequence. In alloys containing 0.42 Mg, 0.50 Si, and 1.0 Cu (wt.%), needle-shaped β″ and Q′ precipitates were observed under peak-aged conditions [

24].

Zhu et al. conducted studies on automotive sheet materials and demonstrated that, by applying bake hardening following pre-deformation (PD) after natural aging (NA), both the yield strength and ductility could be maintained at an optimal level. In the investigated alloy, the Mg/Si ratio was 0.618, while the Cu content was 0.20 wt.%, both of which play a crucial role in controlling precipitation behavior and bake-hardening response. Bake hardening was performed at 185 °C for 20 min, following the NA–PD processing sequence [

25].

One of the most recent studies reported that the presence of B′-Al

3Mg

9Si

8, Q′-Al

6Cu

2Mg

6Si

7, and Q-Al

3Cu

2Mg

9Si

7 phases enabled the acquisition of atomic-scale contrasted images using the HAADF-STEM method. It has been observed that the Q phase strengthens the covalent interaction between Si and Cu atoms, resulting in a more stable structure resistant to deformation. The presence of the Q′ phase also affected the sensitivity of the material’s mechanical response to crystal orientation, but the opposite effect was observed for the Q phase [

26].

Famelton et al. investigated the evolution of dissolved clusters and precipitate formation in detail for low (0.1%) and high-Cu-containing aluminum alloys (0.3%) using Atom Probe Tomography (APT) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) methods. In this study, the alloys were investigated using a multi-stage aging process comprising quenching followed by short-term or prolonged natural aging, pre-aging [170 °C], and final artificial aging [190 °C]. Overall, the results demonstrate that Cu addition promotes a higher precipitate number density by stabilizing solute clusters [

27].

Yang et al. focused on controlling solute aggregates to tailor the aging response of automotive aluminum alloys (Al-Mg-Si-(Cu)) and mitigate the adverse effects of natural aging. In this study, precipitation kinetics were examined for specimens that were naturally aged and subsequently artificially aged, as well as for specimens subjected only to artificial aging. It was observed that natural ageing has a retarding effect on the kinetics of artificial ageing. This study highlights the critical role of natural aging in determining the aging response of aluminum alloys used in the automotive industry [

28].

Wu et al. reported that Cu addition changes the precipitation behavior of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys, with Mg/Si ratios of 0.846, 0.826, and 0.879, and Cu contents of 0, 0.8, and 1.6 wt.%, respectively. The microstructure of the alloy containing 0.8 wt.% Cu is characterized by β′Cu, Q′, L, and C precipitates without the formation of the θ′ phase. On the other hand, in the alloy containing 1.6 wt.% Cu, the θ′ phase was observed after prolonged aging [175 °C for up to 400 h] [

29].

Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys are of significant interest for advanced engineering applications, particularly in the aerospace and automotive industries, due to their ability to be artificially aged for tailored mechanical performance. The addition of Cu to this alloy system introduces complex precipitation phenomena that can enhance strength and hardness; however, achieving the desired properties strongly depends on a thorough understanding of the aging process. Investigating this process provides essential insights into the microstructural evolution of the alloys and informs alloying strategies aimed at meeting the growing demand for lightweight yet high-strength engineering materials. Although the precipitation sequence and strengthening mechanisms of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys are known to be sensitive to chemical composition in the literature, the present study focuses the effect of artificial aging conditions on the mechanical properties of industrially relevant EN AW-6056 alloy with fixed Mg/Si and Cu composition. Accordingly, the present study examines the influence of artificial aging temperature and time on the mechanical properties of EN AW 6056.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, hot extruded aluminum blocks of EN AW 6056 with a diameter of 65 mm are used. In order to eliminate the influence of prior forming operations in the supplied EN AW 6056 alloy and to obtain a homogeneous microstructure over the entire cross-section, all specimens were subjected to a homogenization heat treatment at 450 °C for 15 min before the solution heat treatment. After this process, specimens were taken from both the center and the edge regions, and a total of six tensile tests were performed. In addition, 15 Vickers hardness measurements were carried out across the whole cross-section. The results obtained from the homogenized material are presented in

Table 1. The low standard deviation values observed in the test results indicate that the homogenization heat treatment was effective.

The chemical composition of the investigated EN AW 6056 alloy was well balanced, containing 0.92% Cu along with 0.93% Mg and 0.99% Si. The detailed elemental composition of the extruded EN AW 6056 material is presented in

Table 2.

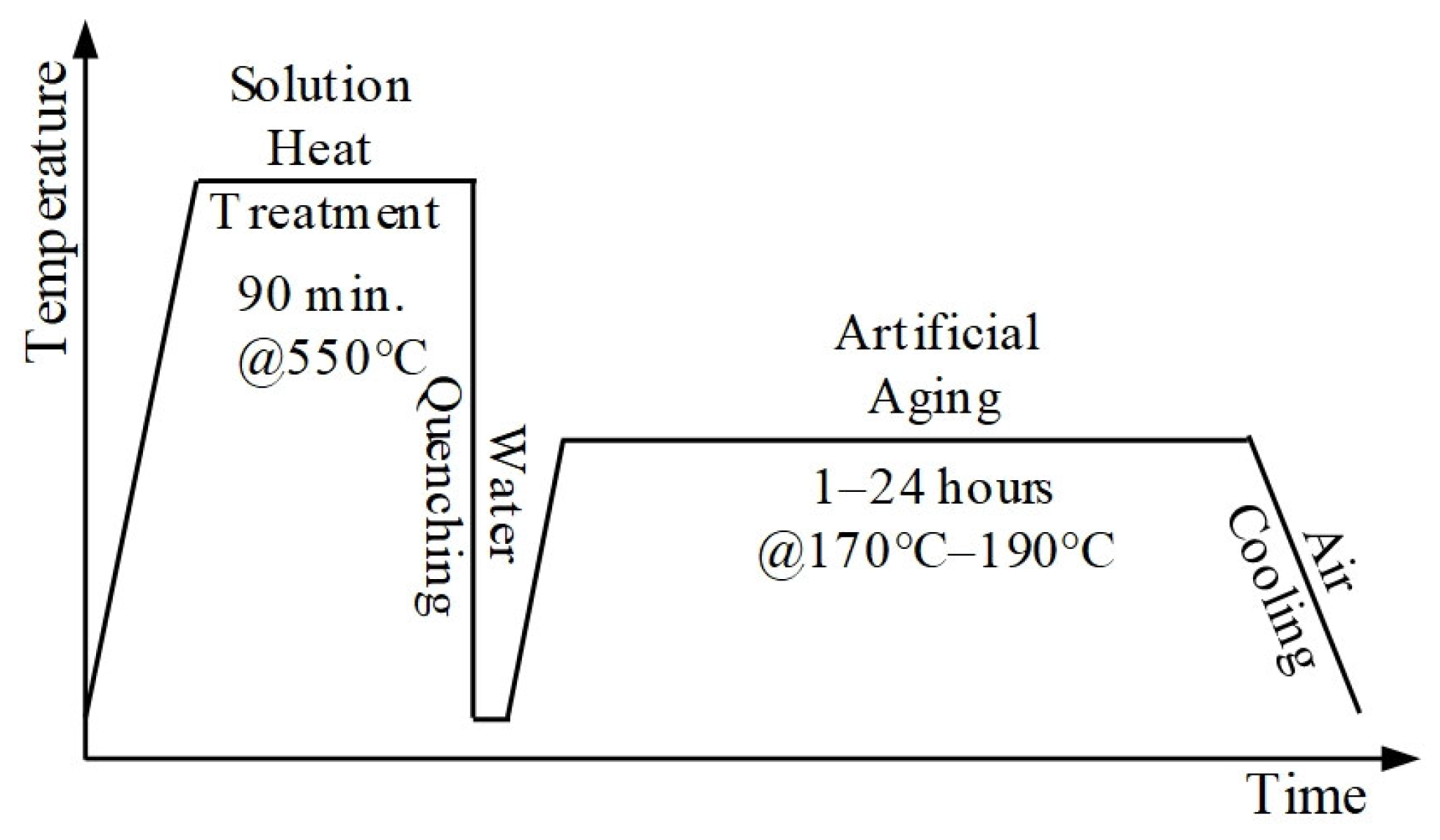

To investigate the effect of artificial aging on hardness, disks with a thickness of 11 mm were sectioned from the homogenized material. Following normalization, the specimens underwent a series of heat treatments, including solution heat treatment (SHT), quenching, and artificial aging (AA). The sequential heat treatment procedure applied to EN AW 6056 is illustrated in

Figure 1. Although there are different parameters regarding the solution heat treatment temperature for 6XXX series alloys, it is fundamentally known that it depends on the maximum solubility of the elements constituting the alloy within the aluminum matrix. Mg, Si, and Cu elements exhibit eutectic phase transition temperatures of 450, 577, and 547 °C, respectively, with corresponding maximum solid solubilities in aluminum matrix of 17.4, 1.65, and 5.7 wt.% [

30,

31]. Based on the findings of Gortan et al., who previously investigated EN AW 6082 aluminum alloys, the solution heat treatment parameters selected in this study were adopted [

32]. The SHT was performed by holding the samples at 550 °C for 90 min, after which they were quenched in room-temperature water for 10 min. Subsequently, the specimens were artificially aged according to the parameters listed in

Table 3 to identify the optimum aging temperature and duration that yield maximum hardness. Artificial aging was carried out at temperatures of 170 °C, 180 °C, and 190 °C [

20,

27]. These temperature levels were selected based on previous academic studies and values commonly used in industrial applications. In addition, the artificial aging temperatures were chosen to represent under-aging and over-aging conditions, as well as the intermediate region between them, as reported in the literature [

20,

27].

The Vickers hardness measurements were performed in accordance with ISO 6507-1 using a Future-Tech FM-700e tester (Future-Tech, Kawasaki-City, Japan) to determine the optimum aging parameters that yield maximum hardness [

33]. Prior to testing, the artificially aged specimens were sequentially ground using P400, P800, P1200, and P2500 abrasive papers (Metkon, Bursa, Türkiye). The ground surfaces were then polished with 6 μm and 1 μm diamond suspensions (Metkon, Bursa, Türkiye) to prepare them for hardness evaluation. All measurements were carried out under a load of 500 g-force with a dwell time of 15 s and were conducted using the same testing equipment by the same operator to minimize experimental variability. For each investigated heat treatment condition, two different specimens were prepared for hardness measurements. Ten hardness measurements were taken from each specimen, resulting in a total of 20 measurements for each condition, and the average value was calculated.

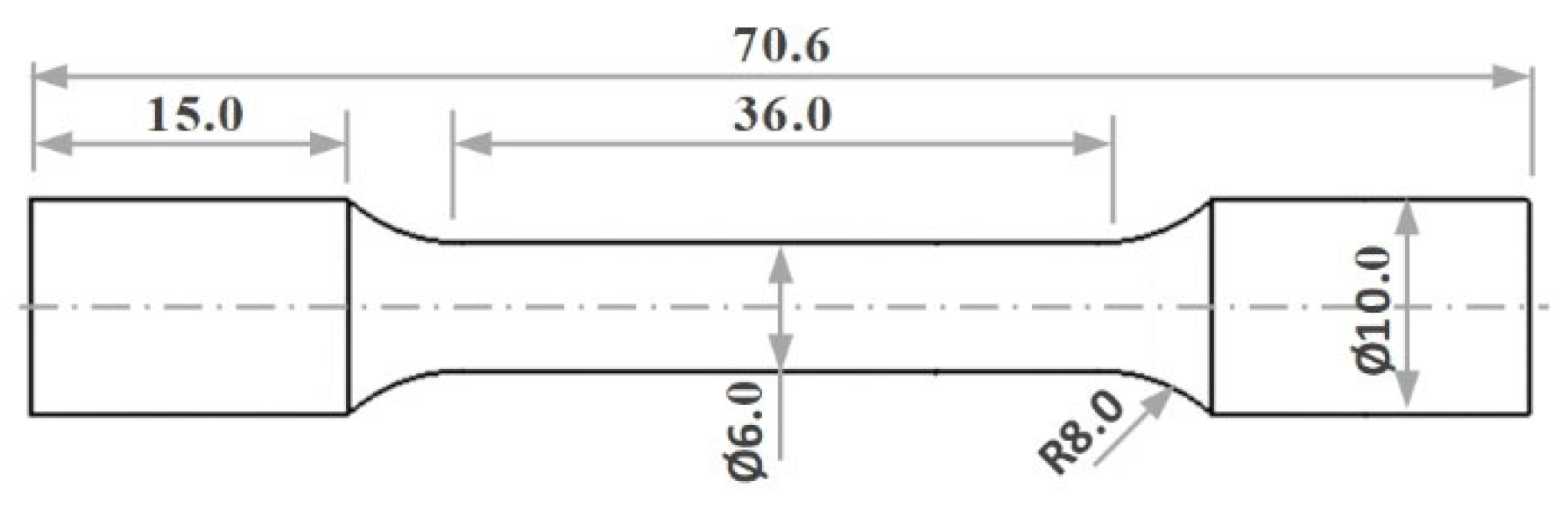

The optimum aging duration that produced maximum hardness at each aging temperature was identified based on the hardness test results. The samples aged for the times corresponding to peak hardness at 170 °C, 180 °C, and 190 °C were subsequently subjected to tensile testing in accordance with ISO 6892-1 standard [

34]. After undergoing heat treatment under various aging conditions and durations, the aluminum blocks were sectioned into four equal parts in the upright orientation. These parts were first rough-machined into 15 mm bars on a lathe, and the final tensile specimen geometry shown in

Figure 2 was precisely fabricated on a CNC lathe (DMG Mori, Wernau, Germany) to ensure the required dimensional accuracy and surface finish for reliable mechanical testing. The room-temperature tensile tests were performed using a BESMAK servo-hydraulic tensile testing system (BMT-20D, Besmak, Ankara, Türkiye) at a strain rate of 1 × 10

−3.

The artificially aged samples were ground using abrasive papers of progressively finer grit to remove the indentations left by the hardness tests. They were then polished with 6 µm and 1 µm diamond suspensions before being etched with Keller’s reagent to reveal the microstructure. Keller’s solution, which selectively attacks grain boundaries while leaving the aluminum matrix largely unaffected, was prepared by sequentially adding 5 mL of HNO3 (65%), 2 mL of HF (38–40%), and 3 mL of HCl (37%) to 95 mL of distilled water. The polished surfaces were immersed in freshly prepared Keller’s reagent for 90 s. After etching, the reagent was removed under running water, the samples were dried with compressed air, and the microstructures were examined using an Optika IM-3MET inverted polarized light microscope (Optika, Ponteranica, Italy).

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was employed to analyze the precipitation kinetics. For DSC sample preparation, the 65 mm thick aluminum bar was machined to a diameter of 3 mm on a lathe and subsequently ground with P2500 abrasive paper (Metkon, Bursa, Türkiye) to remove residual stresses. DSC specimens artificially aged at 170 °C for 12 h and 190 °C for 4 h were sectioned into 0.3 mm thick disks weighing approximately 20 mg using a micro-cutter. The DSC tests were conducted using a Hitachi DSC 7020 system (Hitachi, Ibaraki, Japan), in which the sample temperature was increased from room temperature to 400 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min.

The precipitate distribution in the artificially aged samples was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Specimens from selected heat-treatment conditions were first cut into 15 mm × 15 mm square disks with a thickness of 300 μm. These disks were subsequently punched into 3 mm diameter foils and thinned at the center using twin-jet electropolishing with a nitric acid-based solution. The resulting foils were then analyzed using a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) to characterize the microstructural features.

3. Results and Discussion

To comprehensively evaluate the influence of different aging conditions on the mechanical properties of the EN AW 6056 alloy, the hardness, DSC, TEM, metallographic, and tensile test results were jointly analyzed. This integrated assessment provides a detailed understanding of the alloy’s behavior under various aging treatments and establishes the correlation between thermal–mechanical responses and the corresponding microstructural evolution. A similar process–microstructure–property processability has also been applied to Al-based functionally graded materials processed by additive manufacturing [

35]. In the present study, processing parameters govern microstructural evolution and the resulting mechanical response.

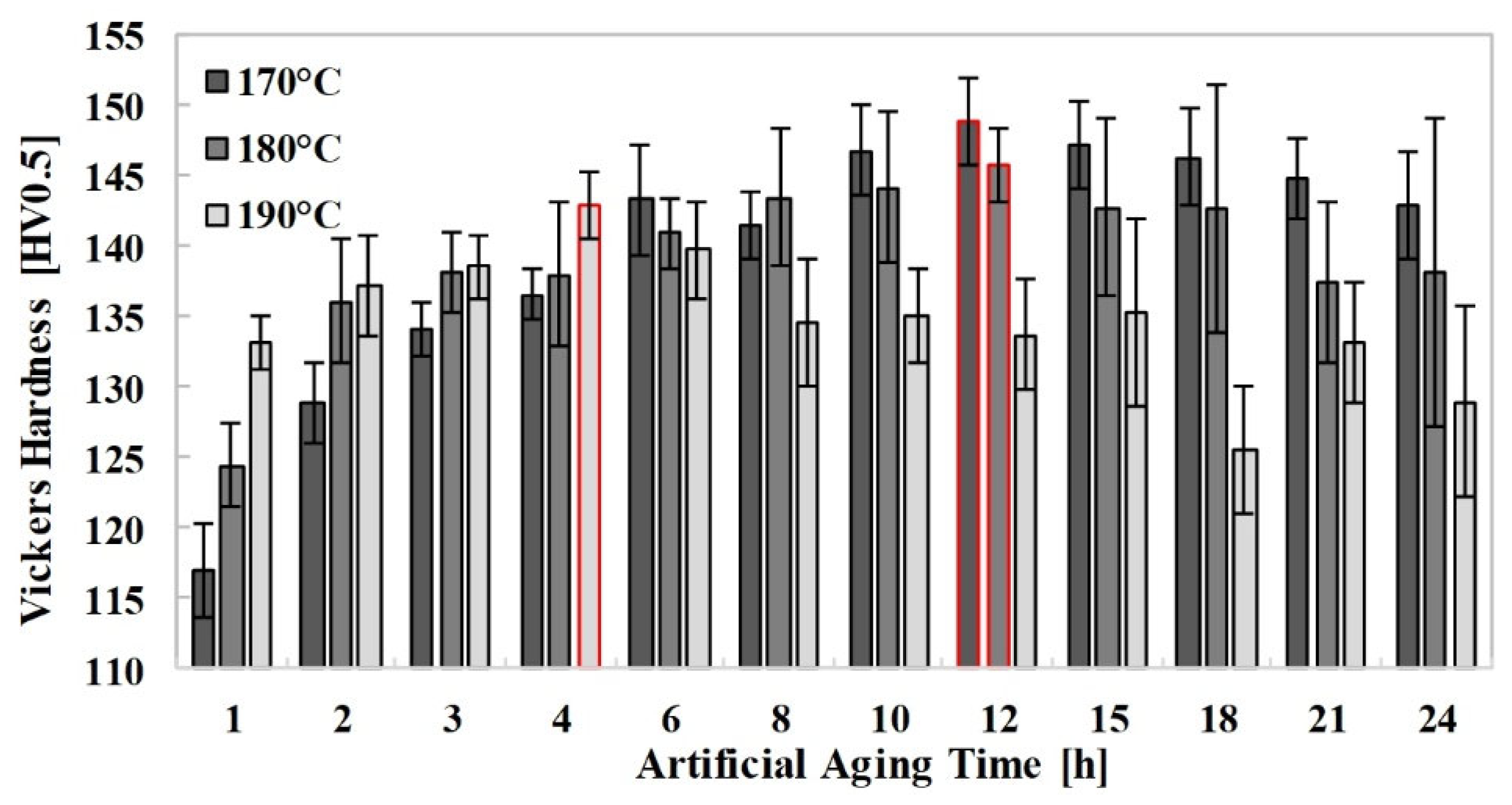

The results of the hardness test are summarized in

Figure 3, where the average values of ten measurements for each condition, along with their standard deviations, are presented. As shown in the figure, the optimum aging time for achieving maximum hardness is 12 h at both 170 °C and 180 °C. For the artificial aging process conducted at intermediate temperatures typical for Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys, it is observed that at 190 °C, the peak hardness is reached in a shorter time compared to the lower aging temperatures. Therefore, aging the material at 190 °C for 4 h offers a balance between hardness and energy efficiency. Moreover, although extending the aging time at a constant temperature initially enhances hardness, exceeding the optimum duration leads to a decrease in the hardness of the EN AW 6056 alloy. Furthermore, it was observed that increasing the artificial aging time also increased the standard deviation of the measured hardness values. At each investigated temperature level, the standard deviation of the hardness values measured up to the maximum hardness remained below ±3 HV0.5. However, when the artificial aging time was further increased, both a decrease in hardness and a noticeable increase in the standard deviation were observed.

However, since hardness results alone cannot fully characterize the mechanical performance of the alloy, additional tensile tests were conducted to evaluate its strength behavior under different aging conditions.

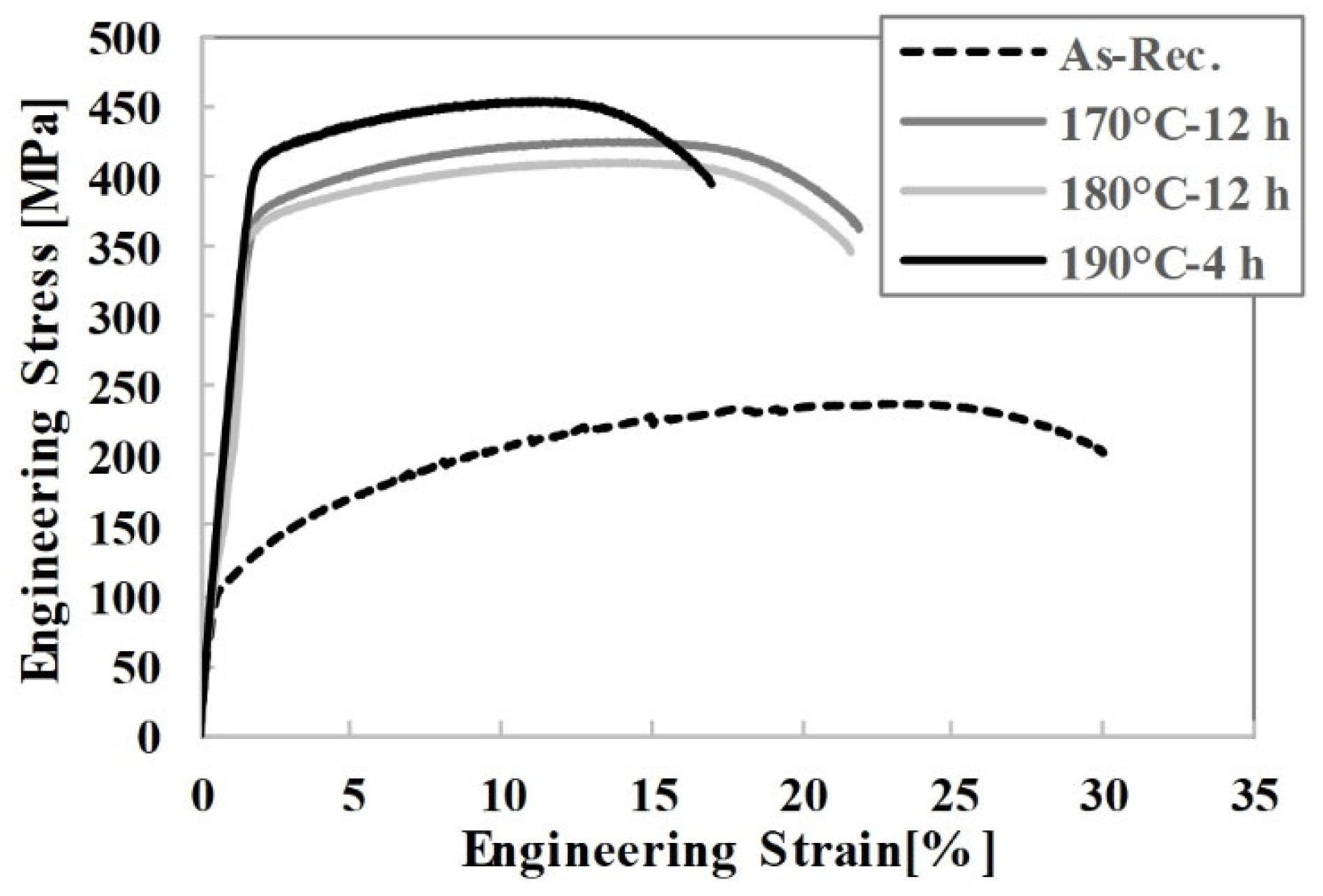

Although hardness measurements provide information about the optimum conditions for achieving maximum hardness, tensile tests are essential to determine the yield strength and ultimate tensile strength of the artificially aged specimens. Therefore, the mechanical properties corresponding to the peak hardness conditions at each investigated aging temperature were examined. The same block materials used for the hardness measurements were also employed in the tensile tests. For this purpose, two blocks were heat-treated under the selected parameters, and two tensile specimens with the geometry shown in

Figure 2 were machined from the middle sections of these blocks. Consequently, four specimens were tested for each condition. The yield strength values were determined using the 0.2% offset method. The tensile test results are presented in

Figure 4 and

Table 4.

The tensile test results reveal certain discrepancies compared to the hardness test outcomes. While the maximum hardness was obtained under the 170 °C-12 h aging condition, the highest tensile strength was recorded after artificial aging at 190 °C for 4 h. In contrast to the hardness findings, the lowest strength values were observed in samples aged at 180 °C for 12 h. These results indicate that even a 10 °C difference in the artificial aging temperature of the EN AW 6056 alloy significantly influences its mechanical properties. Moreover, the duration of the aging process also has a pronounced effect on mechanical strength. When the aging temperature increased from 170 °C to 180 °C, the average yield strength and tensile strength decreased by 18.33 MPa and 22.79 MPa, respectively. However, with a further 10 °C increase, the yield strength and tensile strength rose to 400.50 MPa and 451.41 MPa, respectively. Notably, these high values were achieved within a relatively short duration of only 4 h. The findings highlight a clear discrepancy between the hardness and tensile test results for the EN AW 6056 alloy. Another important observation from the tensile tests is that the elongation at fracture is inversely proportional to both yield and tensile strength. During peak aging, precipitates form and grow, allowing the alloy to reach its maximum hardness. At this stage, the size and distribution of the precipitates effectively block dislocation motion. As a result, the material becomes harder and stronger, but more brittle, leading to a reduction in fracture elongation. Accordingly, the highest elongation at fracture was observed in specimens aged at 180 °C for 12 h, whereas the lowest elongation was recorded in specimens aged at 190 °C for 4 h. Hereinafter, the condition aged at 190 °C for 4 h is referred to as the peak-aged state, while the condition aged at 170 °C for 12 h is defined as the transition to over-aging state.

The observed differences in hardness and tensile strength can be attributed to microstructural variations induced by the aging process. Therefore, optical microscopy analyses were initially carried out to examine the grain morphology of the EN AW 6056 alloy under different aging conditions.

The optical micrographs of the specimens etched with concentrated Keller’s reagent are presented in

Figure 5. The images correspond to the as-received sample and the specimens exhibiting the highest strength at each investigated aging temperature. The analysis of the grain structures revealed negligible variation in grain size among the different artificial aging conditions. Quantitative grain size measurements were found to be 17.44 ± 3.8 µm, 18.53 ± 3.7 µm, 23.38 ± 5.5 µm for the 170 °C-12 h, 180 °C-12 h and 190 °C-4 h, respectively. Hence, the discrepancy between the hardness and tensile test results cannot be attributed to differences in grain size after artificial aging.

The DSC thermograms obtained from two different artificial aging conditions—aging at 170 °C for 12 h and at 190 °C for 4 h—are presented in

Figure 6. In the DSC results, distinct endothermic and exothermic peaks correspond to specific precipitation or dissolution events. The exothermic peaks are associated with the formation of strengthening precipitates that enhance the hardness of the alloy, whereas the endothermic peaks are related to the dissolution or transformation of these precipitates into more stable phases. The peak temperatures were used to estimate the appropriate aging temperature range for maximizing the mechanical strength of the alloys.

In the DSC diagrams of as-quenched, peak-aged, and over-aged AA6111 alloys—which contain a copper content similar to that of the EN AW 6056 alloy—the most prominent peaks or shoulders appear in the as-quenched condition. Additionally, distinct peaks corresponding to the formation of Mg–Si clusters and GP zones have been reported in the literature [

36]. For the 6061 aluminum alloy, DSC analysis performed at a heating rate of 10 K min

−1 after solution heat treatment and quenching revealed the formation of Si clusters, identified by a shoulder near 80 °C [

37]. Ding et al. reported that variations in Cu content influence precipitation kinetics when comparing Al-Mg-Si and Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys, resulting in the β″ phase forming at lower temperatures [

19].

Literature findings on Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys indicate that exothermic peaks observed between 100 °C and 175 °C correspond to the formation of solute clusters, including Mg, Si, and Mg–Si co-clusters [

9,

11,

19,

38]. Based on these insights, the thermographic data obtained in this study are interpreted as follows: the first peak or shoulder in the DSC curve represents the formation of Si, Mg, and Si–Mg co-clusters. As the temperature increases to approximately 165 °C, the formation of Guinier–Preston (GP) zones occurs, further strengthening the alloy. An endothermic peak appearing between 200 °C and 220 °C indicates the dissolution of GP zones [

9,

10,

38]. The exact temperature of this peak depends on the artificial aging temperature, duration, and the Cu content of the alloy [

10,

19].

The third exothermic peak, detected near 250 °C, corresponds to the formation of β″ precipitates, which are primarily responsible for the strength increase under peak-aged conditions [

10,

11]. Literature reports also note that the β″ phase exhibits strength-enhancing behavior in the T6I6 temper of the 6061 alloy containing 0.25 wt.% Cu [

39]. The fourth exothermic peak corresponds to the formation of βʹ precipitates [

10]. In the specimen aged at 190 °C for 4 h, a fifth exothermic peak appears around 315 °C, which is absent in samples aged at 170 °C for 12 h and corresponds to the formation of L precipitates. Finally, the exothermic peak detected at 325 °C indicates the development of Qʹ precipitates [

9,

11].

Several studies in the literature have investigated the types of precipitates formed in the peak-aged and over-aged conditions of Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys [

8,

12,

40,

41]. It has been reported that the type-C precipitate, typically observed in Si-rich Al–Mg–Si alloys, and the Q′ precipitate found in Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys share the same crystal structure [

42,

43]. The presence of approximately 0.03 wt.% Cu in Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys has been shown to influence the evolution of precipitates during over-aging. As the aging time increases, the fraction of β″ precipitates decreases, whereas the amount of Q′ phase increases once the aging duration exceeds one week [

44].

In one study, an Al–Mg–Si–Cu alloy containing 0.5 wt.% Cu aged at 250 °C (peak-aged condition) exhibited Q′ precipitates with lattice parameters of a = 1.04 nm and c = 0.405 nm [

43]. Other studies have revealed that Q′ and L precipitates can coexist under over-aged conditions, with Q′ having the same lattice parameters as the Q phase [

12,

40]. Torsæter et al. [

12] reported that in an Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloy containing 0.13 wt.% Cu, over-aging results in the presence of both Q′ and L precipitates.

In another investigation, the precipitates formed in Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys containing 0.25, 0.01, and 1 wt.% Cu were examined under both over-aged and peak-aged conditions. The results showed that the β″ phase with a needle-like morphology dominated the peak-aged condition, whereas the L phase with a lath-like shape appeared in the alloy containing 1 wt.% Cu [

40]. Similarly, in an alloy with 0.91 wt.% Cu and an Mg/Si ratio of 0.437, subjected to pre-aging, natural aging, and a subsequent paint-bake cycle, both β″ precipitates and a lath-like Q′ phase were observed. TEM analysis in that study revealed fine dot-like features at the ends of β″ precipitates [

41].

In the present study, TEM observations confirm that under the peak-aged condition, the EN AW 6056 alloy exhibits the formation of L, Q′, and β″ phases, each with distinct morphological features. The β″ phase appears as fine needle-shaped precipitates, the Q′ phase as lath-like structures, and the L phase as narrow rectangular platelets. Although some studies have reported the formation of Q′ during over-aging, in the current work it was identified under the peak-aged condition.

Figure 7 presents TEM micrographs of specimens in the transition to over-aging and peak-aged conditions. In the transition to over-aging condition (

Figure 7a), lath-shaped Q′ precipitates with sharp edges are observed together with β″ precipitates. In addition, multiple globular βʹ precipitates appear, indicating the over-aging of β″ precipitates. The average length of the β″ and Q′ precipitates in the transition to over-aging condition are measured as 9.23 nm and 11.87 nm, respectively.

Under the peak-aged condition (

Figure 7b), β″, Q′, and L precipitates (the precursors of the Q′ phase) are detected. Multiple L precipitates with lath-like morphologies and irregular terminations are dispersed within the aluminum matrix. The Q′ precipitates exhibit sharper boundaries and greater thickness compared with the L phase. The average length of the L and Q′ precipitates in the peak-aged condition are measured as 6.95 nm and 7.32 nm, respectively.

When the TEM results are considered together with the DSC findings, the only distinct difference between the peak-aged condition and the transition to the over-aged condition is the presence of L precipitates in the peak-aged state. This observation further supports the interpretation that the exothermic peak detected in DSC analysis at around 315 °C exclusively in the peak-aged condition is associated with the L precipitate. Since no significant differences are observed in grain size or in the characteristics of other precipitate phases, it is concluded that the higher strength obtained in the peak-aged condition is predominantly attributed to the contribution of the L precipitate. This interpretation is supported by the work of Chakrabarti et al. [

22], who reported that a phase acting as the precursor to Q′ in Al-Mg-Si-(Cu) alloys enhances mechanical strength in addition to the β″ phase. The elemental composition of the S802 specimen studied by Chakrabarti et al. is similar to that of the alloy used in this work, supporting the conclusion that one of the strengthening phases present in the peak-aged condition is likely the L phase.

The combined evaluation of the hardness, tensile, DSC, and TEM results confirms that the mechanical behavior of the EN AW 6056 alloy is strongly influenced by the precipitation sequence and morphology of the strengthening phases formed during artificial aging. In particular, the formation of β″, Q′, and L precipitates under the peak-aged condition enhances the alloy’s strength, while prolonged aging promotes the transformation of β″ into βʹ and Q′, resulting in reduced hardness and ductility. These findings demonstrate the direct correlation between the microstructural evolution and the mechanical performance of the alloy, highlighting the critical role of aging temperature and duration in optimizing its properties.