1. Introduction

Hot stamping has become a key manufacturing technology for producing ultra-high-strength structural components, especially in the automotive industry, where the demand for vehicle lightweighting and crashworthiness continues to intensify [

1]. During the process, Al–Si-coated 22MnB5 boron steel sheets are heated to approximately 900–930 °C, rapidly transferred into the die, and then simultaneously formed and quenched. This thermo-mechanical sequence imposes extreme conditions on hot-work steel dies, including steep thermal gradients, repetitive contact stresses, frictional shear, high-temperature oxidation, and chemical reactions between the die and the Al–Si coating. As a result, die surface degradation remains a major factor limiting production stability and dimensional accuracy in industrial hot stamping [

2].

Mo–W alloyed hot-work steels are widely employed in hot stamping dies due to their excellent temper resistance, good thermal conductivity, and high hot-hardness retention [

3]. Nevertheless, despite these favorable properties, such steels experience complex degradation during extended industrial service. Reported failure modes include thermo-mechanical fatigue (TMF)-induced softening [

4], oxidation-assisted embrittlement [

5], adhesive wear (galling) [

2], abrasive wear [

6], and the formation of brittle Fe–Al and Fe–Al–Si intermetallic layers driven by die–sheet chemical interactions [

3]. These mechanisms are considerably more severe in hot stamping than in conventional forming operations because of the much higher temperatures and contact stresses involved.

Although numerous studies have evaluated hot-work steel behavior under controlled laboratory conditions, most investigations have focused on isolated mechanisms—such as TMF softening [

4], high-temperature oxidation [

3], or adhesive transfer of Al–Si coatings from 22MnB5 sheets [

7]. However, industrial die failures typically arise from the convolution of multiple coupled mechanisms rather than from a single dominant mode. Recent tribological and materials degradation studies highlight the need for integrated evaluation of wear, oxidation, reaction-layer evolution, and microstructural changes, yet comprehensive post-mortem analyses of Mo–W hot-work dies removed directly from production lines remain limited.

Adhesive wear, commonly referred to as galling, is widely recognized as one of the major degradation mechanisms in hot stamping dies. Under elevated temperatures and pressures, welded junctions form readily at the die/sheet interface, and their subsequent fracture during sliding removes die material and generates pits and delaminated regions [

7]. The severity of adhesive wear increases when the Al–Si coating on 22MnB5 dissolves into molten films during forming, promoting chemical bonding and material transfer [

8]. Simultaneously, brittle Fe–Al and Fe–Al–Si intermetallic compounds form at the interface, further facilitating crack initiation and surface spallation [

3,

8,

9].

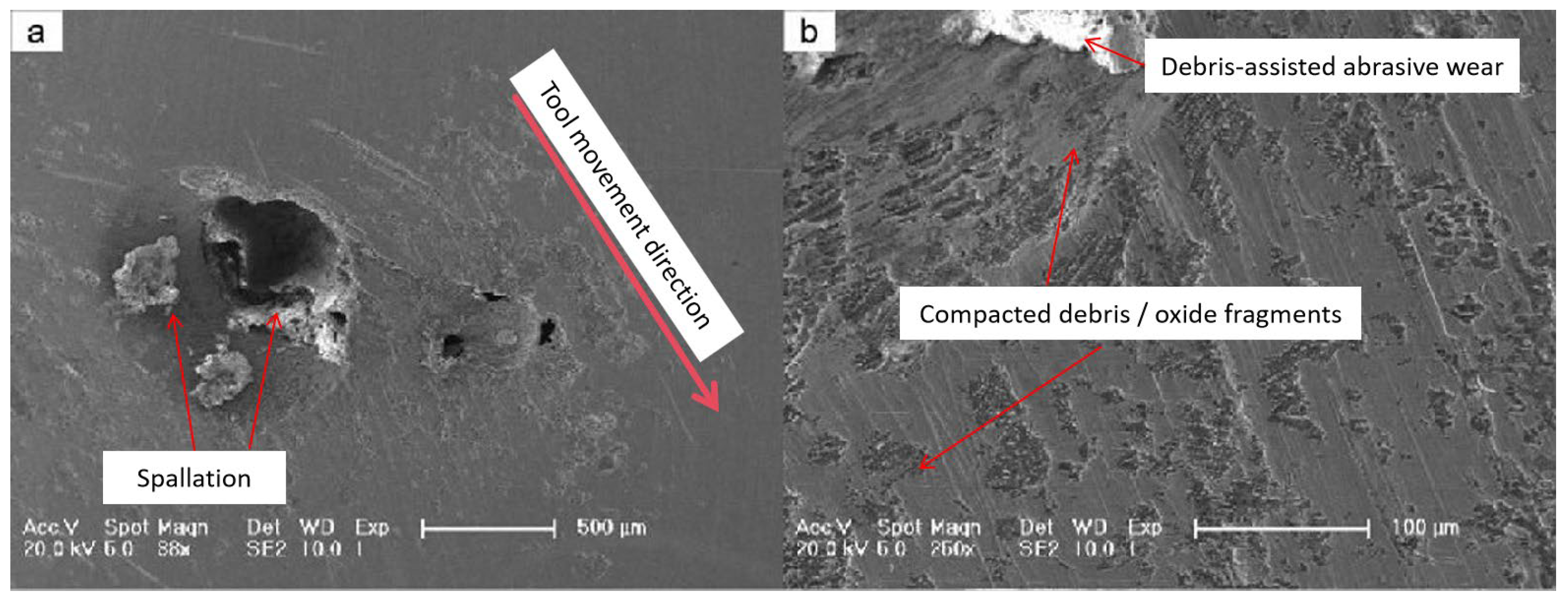

In addition to adhesion, abrasive wear plays a significant role in die deterioration. Detached oxides, fragmented intermetallic particles, and spalled debris act as hard third-body abrasives that plow the die surface and accelerate material removal [

10,

11]. The abrasive component tends to become increasingly dominant as surface roughness grows and debris accumulates during long-term service [

7,

11].

Thermo-mechanical fatigue also contributes significantly to die degradation. Each forming cycle exposes the die surface to high temperatures while cooling channels rapidly extract heat, generating steep thermal gradients that cause cyclic expansion and contraction [

3]. These cycles induce dislocation multiplication, substructure evolution, martensite tempering, and, ultimately, surface softening [

5]. Although TMF behavior in hot-work steels has been documented [

4], the relationship between microstrain evolution, reaction-layer formation, and subsequent wear has not been fully clarified.

Chemical interactions between the die surface and the Al–Si coating additionally influence degradation pathways. At forming temperatures near 900 °C, aluminum diffuses into the die surface and forms Fe–Al intermetallic compounds such as FeAl and Fe

2Al

5, as well as ternary Fe–Al–Si phases including FeSiAl

4. These brittle phases weaken the interfacial region and facilitate crack formation and propagation [

3,

6,

7]. Meanwhile, high-temperature oxidation produces Fe–O scales, which can spall and generate additional abrasive debris [

3]. The coexistence of intermetallics and oxides results in a dynamic and unstable reaction layer whose repeated formation and fracture accelerate die surface deterioration. Recent advances in die materials and surface engineering have demonstrated that ceramic-based coatings, such as AlCrN-, TiAlN-, and multilayer nitride systems, as well as duplex treatments combining nitriding and physical vapor deposition, can effectively suppress Al diffusion, oxidation, and adhesive wear in hot stamping environments. These developments provide important context for interpreting the degradation mechanisms observed in the present industrial die.

Although many of the above mechanisms have been individually reported, industrial hot stamping dies operate under far more complex conditions. In actual production environments, a die experiences tens of thousands of severe thermo-mechanical cycles, and the resulting degradation represents the cumulative effect of interacting wear, oxidation, chemical reactions, and microstructural evolution [

8]. The lack of holistic, mechanism-coupled post-mortem analyses limits the development of predictive die-life models and effective countermeasures [

2].

Given these gaps, the present work performs a comprehensive failure analysis of a Mo–W hot-work steel die removed from a commercial B-pillar hot stamping tool after extensive service. Through hardness mapping, optical microscopy, SEM/EDS, and XRD (including Williamson–Hall analysis), this study identifies the key microstructural, chemical, and tribological contributors to die degradation. Particular emphasis is placed on characterizing pit and crack morphology, reaction-layer composition, microstrain evolution, and the synergistic contributions of adhesive and abrasive wear.

This study aims to: (1) quantify mechanical softening and microstrain accumulation in service-exposed Mo–W steel; (2) characterize the composition, thickness, and morphology of reaction layers, pits, and cracks; (3) differentiate adhesive galling from oxide-assisted abrasive plowing; (4) establish a coherent degradation pathway linking TMF, oxidation, adhesion, abrasion, and brittle fracture; and (5) provide practical recommendations for improving hot stamping die life through material design, coating strategies, and process optimization.

Despite extensive studies on wear and damage mechanisms of hot forging and hot stamping tools, most existing investigations are based on laboratory-scale simulations or focus primarily on surface damage features. As a result, the subsurface degradation behavior of tooling materials under real industrial service conditions remains insufficiently understood.

In particular, the interaction between surface wear, thermal fatigue, and subsurface microstructural softening during long-term industrial operation has not been systematically clarified. This lack of integrated surface–subsurface analysis limits the accurate interpretation of tool failure mechanisms and the development of effective life-prediction strategies.

The present study addresses these gaps by investigating a Mo–W alloyed hot-work steel die extracted directly from an industrial hot stamping production line after extended service. The novelty of this work lies in: (i) the analysis of a real industrially serviced tool rather than a laboratory-tested specimen; (ii) the combined characterization of surface damage features, hardness evolution as a function of depth, and subsurface microstructural changes; and (iii) the establishment of a mechanistic framework linking surface wear to subsurface degradation under cyclic thermo-mechanical loading conditions. These results provide new insights into the degradation behavior of hot stamping dies and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of tool failure mechanisms in industrial environments.

4. Discussion

The degradation of the Mo–W hot-work steel die investigated in this study is governed by a strong coupling between thermo-mechanical fatigue (TMF)-induced softening, high-temperature oxidation, interfacial chemical reactions, adhesive galling, and debris-assisted abrasive wear. Rather than acting independently, these mechanisms interact synergistically and evolve progressively during long-term industrial hot stamping service, ultimately leading to accelerated surface failure.

TMF-induced softening constitutes the fundamental driving force underlying the observed degradation behavior. Repeated thermal cycling between approximately 600 and 700 °C at the die surface and rapid cooling through internal water channels produces severe thermal gradients and cyclic stresses. The pronounced hardness reduction (~17%) from the surface to the subsurface region, together with the coarsening of tempered martensite, confirms significant cyclic tempering and microstructural degradation. Williamson–Hall analysis further reveals elevated microstrain (~0.0021) and refined crystallite sizes (50–80 nm) in the surface region, indicating high dislocation density and lattice distortion. Similar TMF-driven softening and microstrain accumulation have been widely reported for hot-work tool steels subjected to cyclic thermal loading and high-temperature forming conditions [

3,

4,

5,

12].

In addition to individual hardness values, the hardness profiles measured as a function of depth provide further insight into the degradation behavior of the die. The observed hardness gradient from the worn surface toward the subsurface region indicates that thermo-mechanical fatigue-induced softening extends beneath the surface layer rather than being confined to the immediate contact zone. This depth-dependent softening contributes to a progressive reduction in load-bearing capacity near the surface, thereby facilitating adhesive wear, crack initiation, and subsequent debris-assisted abrasion during service.

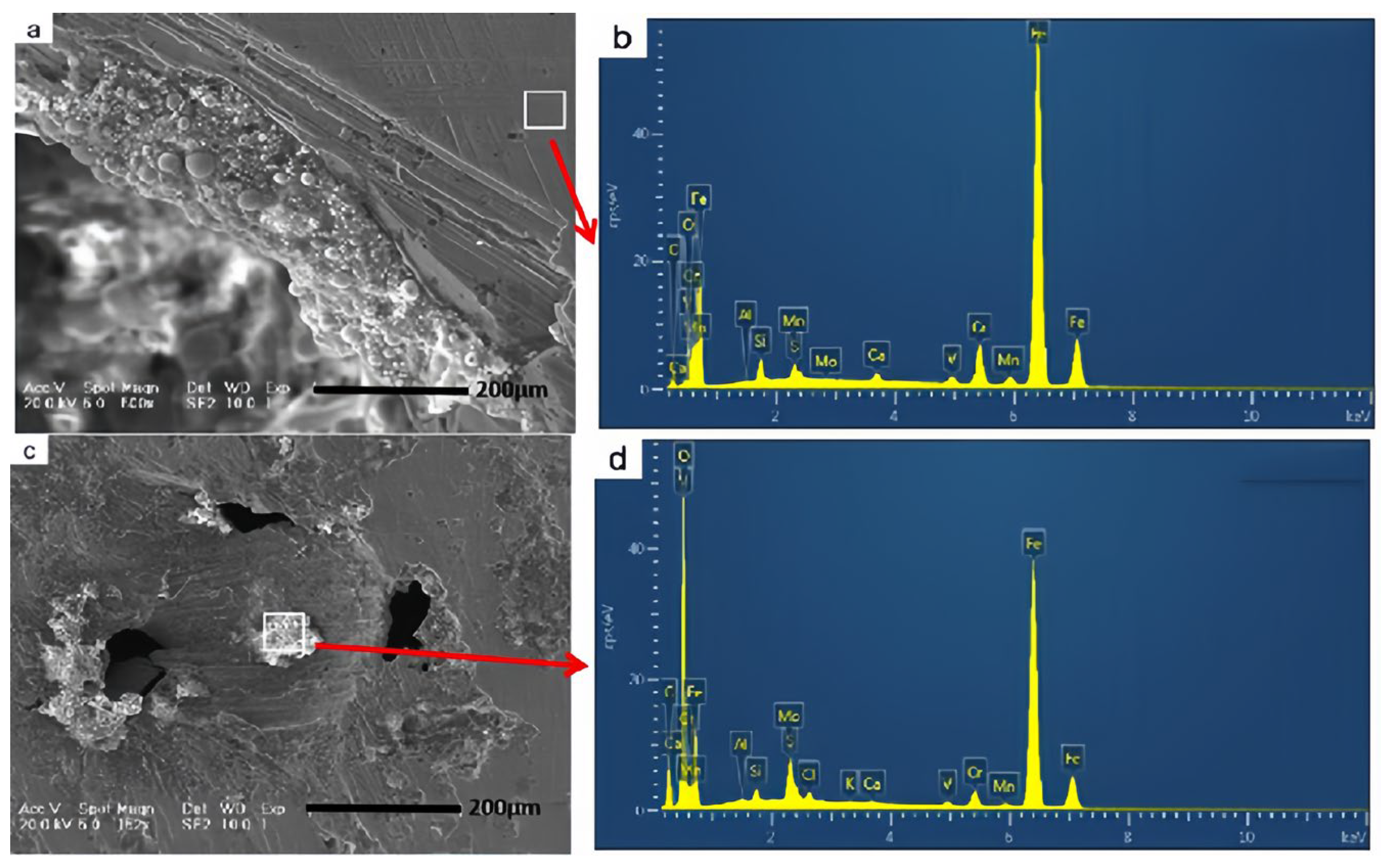

In parallel with TMF damage, high-temperature oxidation and chemical interactions with the Al–Si coating on 22MnB5 sheets promote the formation of complex reaction layers. SEM/EDS analyses confirm the presence of Fe–O oxides, Fe–Al intermetallics, and ternary Fe–Al–Si phases such as FeSiAl

4. These brittle reaction products form discontinuous layers with thicknesses of 15–40 μm, which are highly susceptible to cracking and spallation under combined thermal and mechanical loading. Previous studies have demonstrated that such reaction layers significantly weaken the die surface and serve as preferential sites for crack initiation [

3,

6,

7,

9,

10,

11]. The repeated formation and fracture of these layers thus represent a critical source of hard debris during service.

Adhesive wear (galling) is identified as the dominant wear mechanism during the early stages of die degradation. At elevated temperatures and contact pressures, welded junctions readily form between the softened die surface and the Al-rich coating, particularly when molten or semi-molten Al–Si films are present. The subsequent fracture of these junctions during sliding removes die material and generates pits and torn-out scars, as evidenced by Al-rich transferred layers observed in SEM/EDS analyses. Similar galling behavior has been extensively reported for hot-work tool steels in contact with Al–Si-coated boron steels under high-temperature sliding conditions.

As service proceeds, the wear mechanism progressively transitions from adhesion-dominated galling to a mixed adhesive–abrasive regime. This transition is closely associated with the accumulation of hard debris derived from fractured oxides and intermetallic compounds. These debris particles act as third-body abrasives that plow and cut the softened die surface, leading to pit deepening, groove formation, and accelerated material removal. The observed pit diameters of 150–600 μm and crack lengths of 40–150 μm are consistent with debris-assisted abrasive wear becoming increasingly dominant during prolonged service.

This transition from adhesive wear to debris-assisted abrasive wear is in strong agreement with recent tribological studies on tool steels. Notably, Krbata et al. demonstrated that powdered metallurgy tool steels M390 and M398 exhibit a clear evolution from adhesive galling to mixed adhesive–abrasive wear when hard debris particles are present in the contact interface. Their work highlights the critical roles of microstructure, hardness, and third-body particles in governing wear transitions. The present results closely mirror these findings, as the fractured Fe–Al–Si intermetallics and oxide debris observed here function analogously to hard third bodies, significantly accelerating abrasive plowing once adhesive tearing has occurred. This agreement reinforces the conclusion that debris-assisted abrasion represents a secondary but increasingly dominant wear mode in industrial hot stamping dies.

The concept of third-body-controlled wear provides a unifying framework for interpreting the synergistic interaction between adhesion and abrasion observed in this study. Once adhesive junctions fracture, detached fragments remain trapped within the contact zone and actively participate in subsequent wear processes. Reduced surface hardness due to TMF-induced softening further enhances the effectiveness of third-body abrasion by allowing deeper penetration of hard debris particles. This establishes a positive feedback loop in which TMF degradation promotes adhesive tearing, debris generation, and abrasive plowing, which in turn increases surface roughness, friction, and stress concentration. Similar synergistic wear–oxidation and adhesion–abrasion interactions have been reported for hot-work tool steels under high-temperature sliding and forming conditions [

9,

11,

12,

13,

14].

From an industrial perspective, the coupled degradation pathway identified in this study can be summarized as: TMF-induced softening → oxidation and intermetallic formation → adhesive junction formation and fracture → debris generation → debris-assisted abrasive wear → crack propagation and pit enlargement → final surface failure. This sequence emphasizes that long-term die performance is controlled by mixed-mode wear mechanisms rather than by isolated adhesion or abrasion alone. Consequently, effective mitigation strategies must address multiple degradation pathways simultaneously.

Potential approaches to extending die service life include alloy design strategies aimed at stabilizing carbides and improving resistance to TMF-induced softening, as well as surface engineering solutions such as AlCrN-based and multilayer nitride coatings that suppress Al diffusion, oxidation, and adhesive galling. In addition, process optimization measures, including improved cooling-channel design and controlled lubrication, can reduce thermal gradients and adhesion severity. Monitoring indicators such as hardness gradients, reaction-layer thickness, and pit size evolution may further support predictive maintenance and life management of hot stamping dies under industrial conditions.