Comparative Study on Reduction in Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron-Ore Lumps and Pellets Under H2 Atmosphere

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Material

2.2. Preparation of Lumps and Pellets

2.3. Reduction Under H2 Atmosphere

2.4. Analysis and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

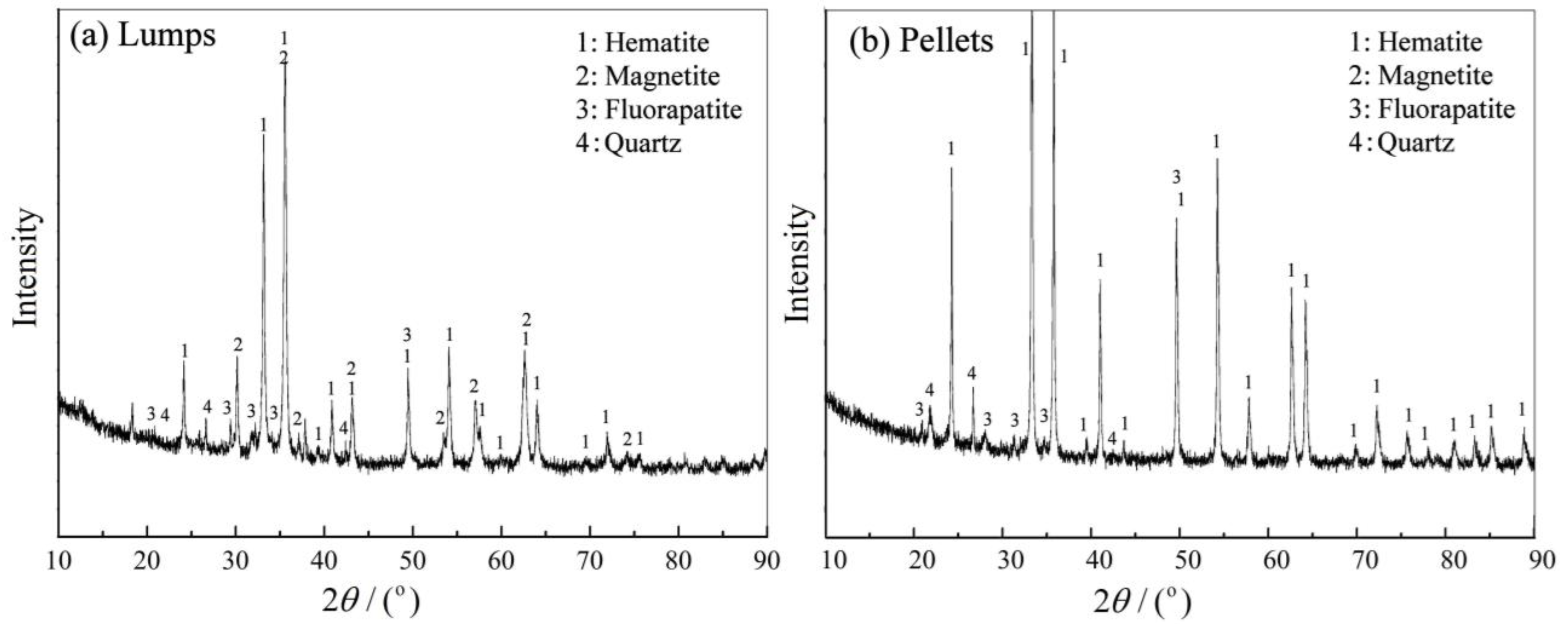

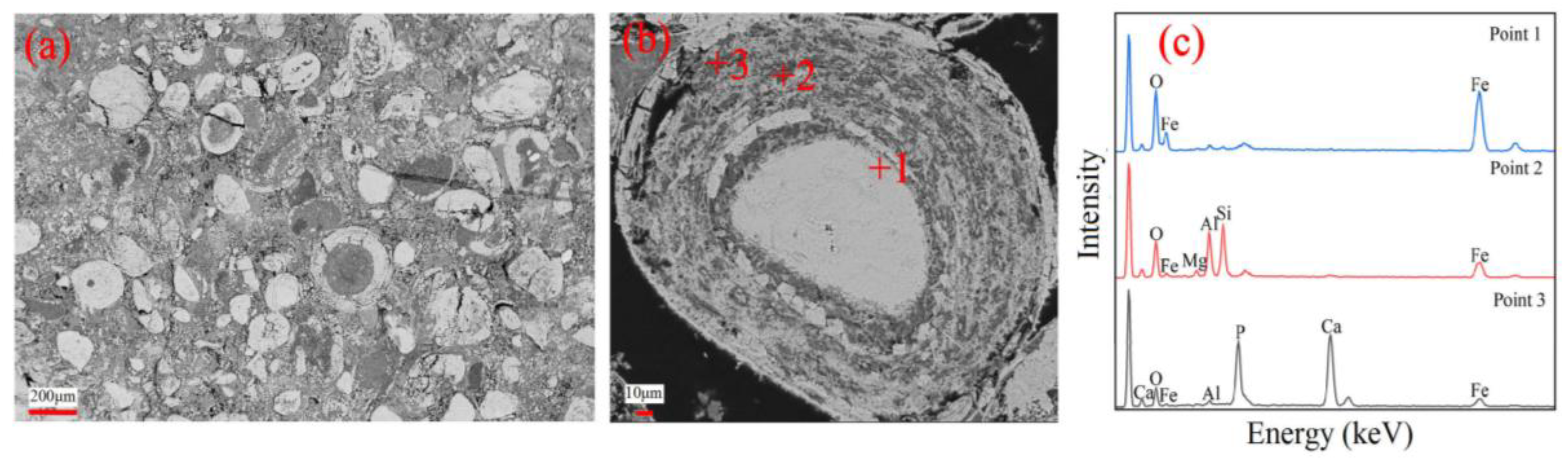

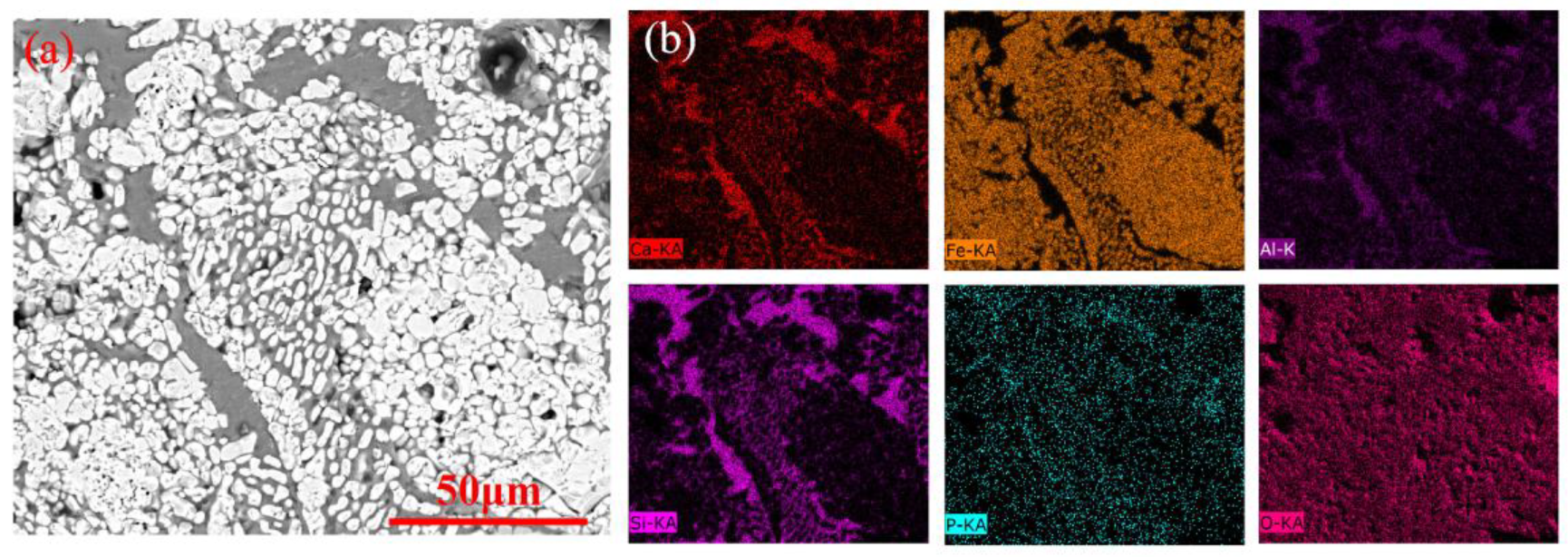

3.1. Characteristics of Lumps and Pellets

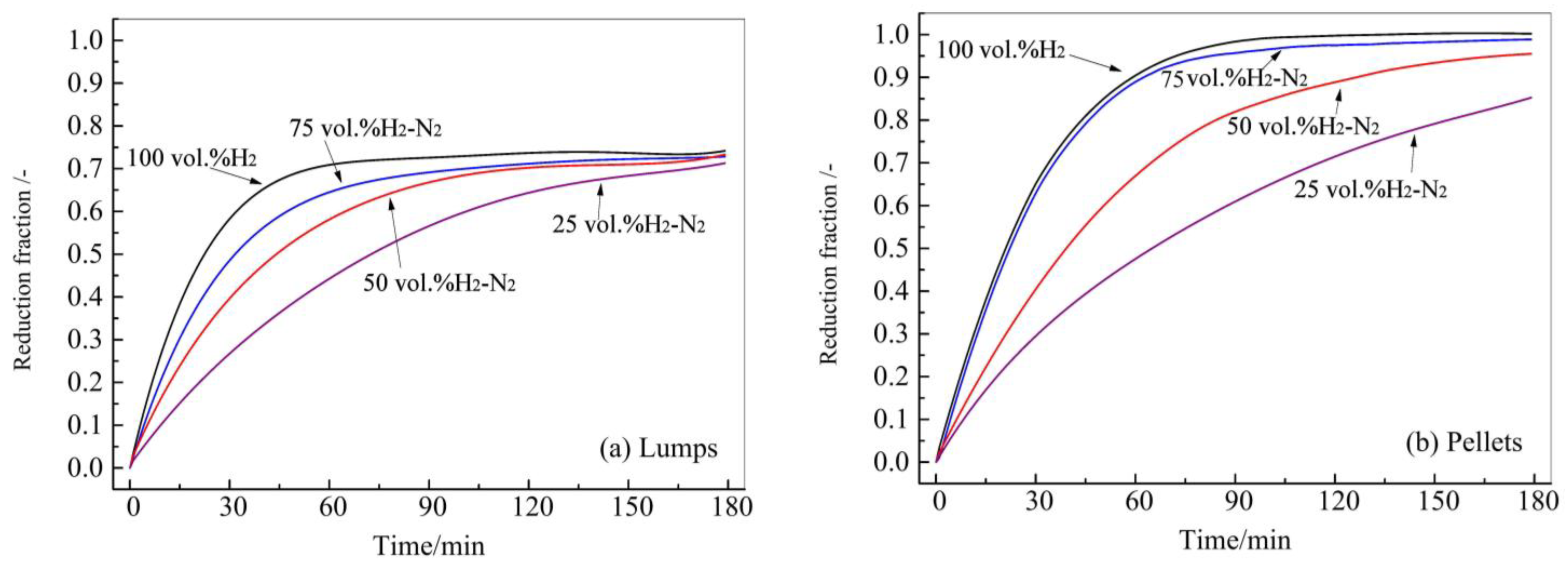

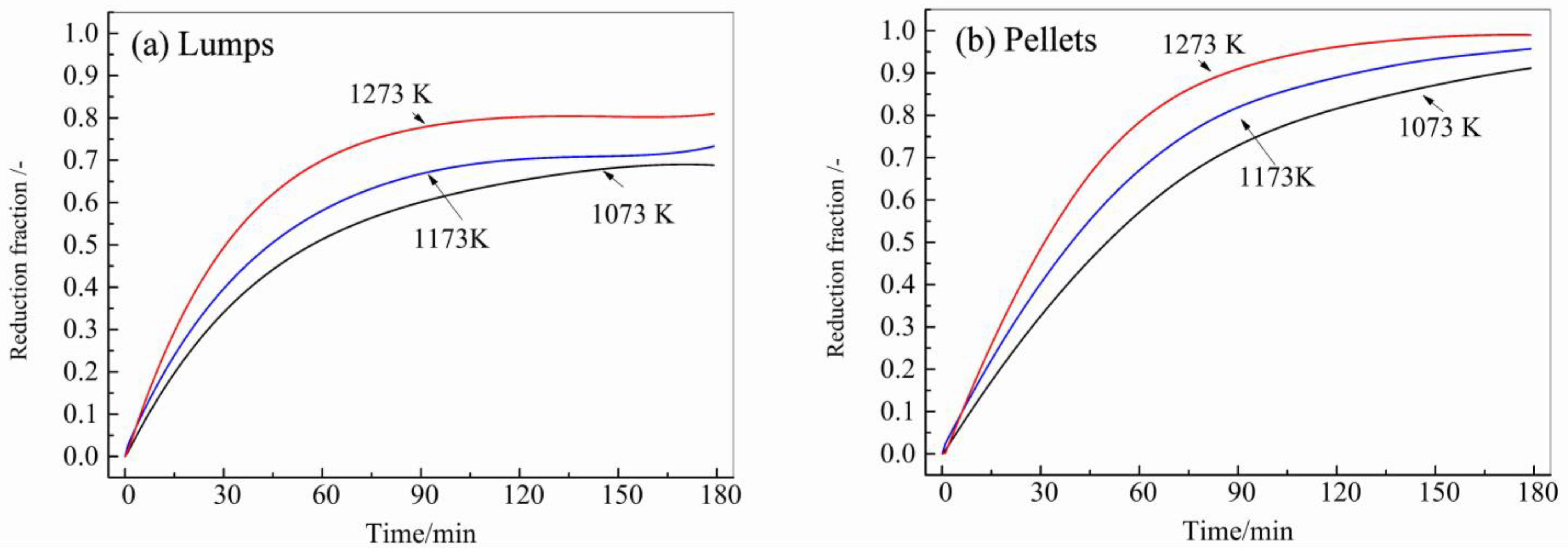

3.2. The Effect of Hydrogen Concentration and Temperature on Reduction

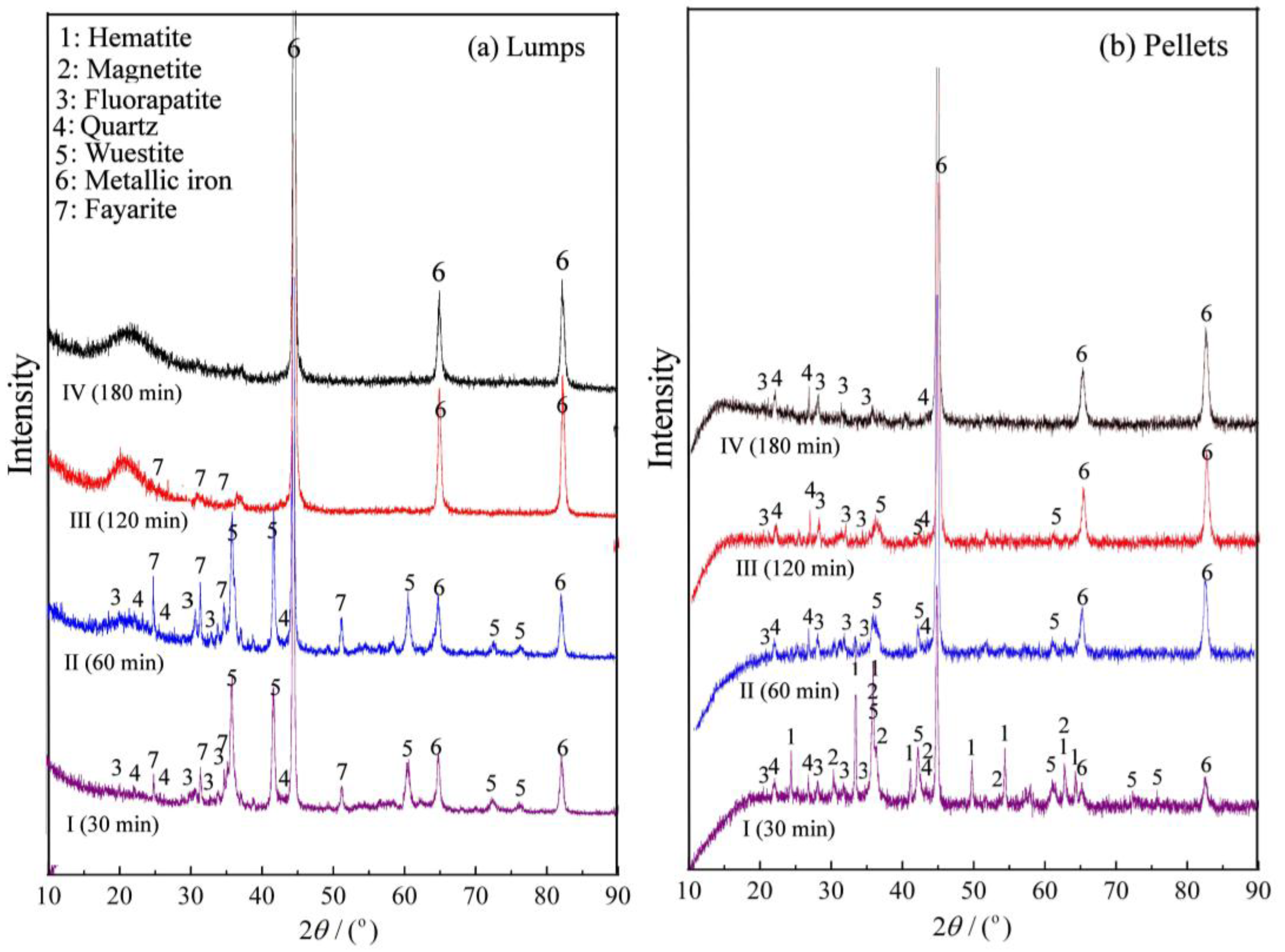

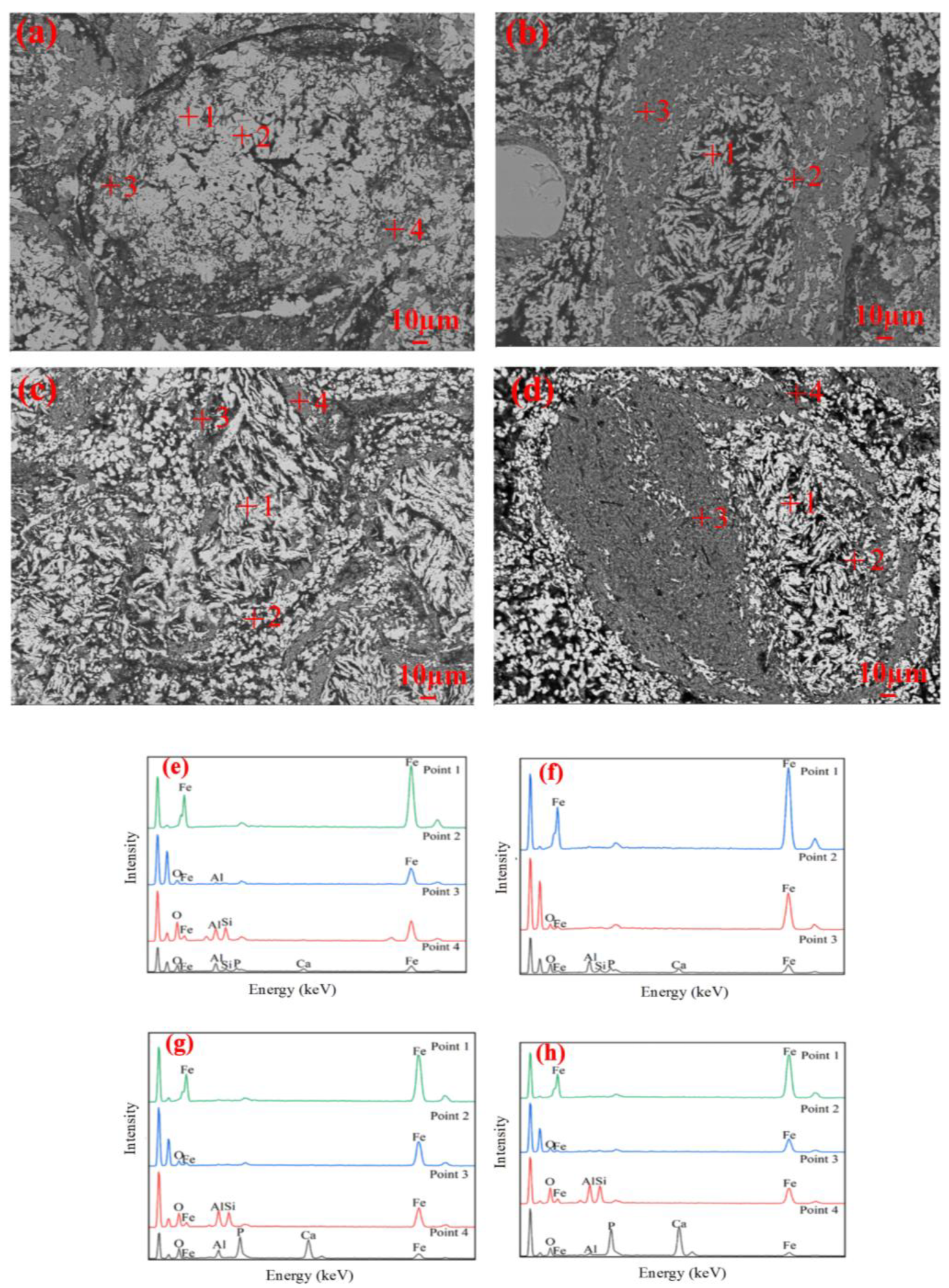

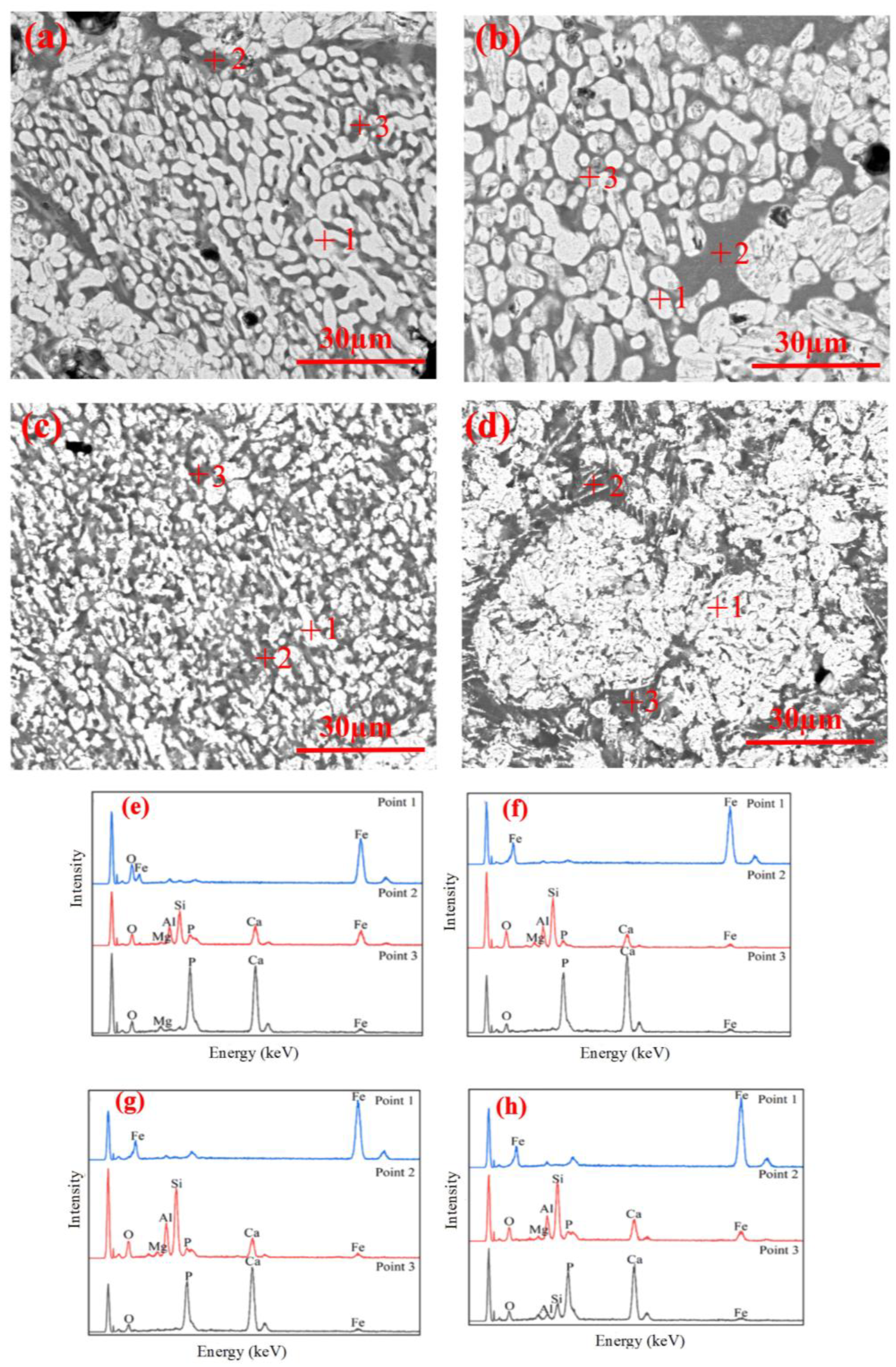

3.3. Microstructure Evolution

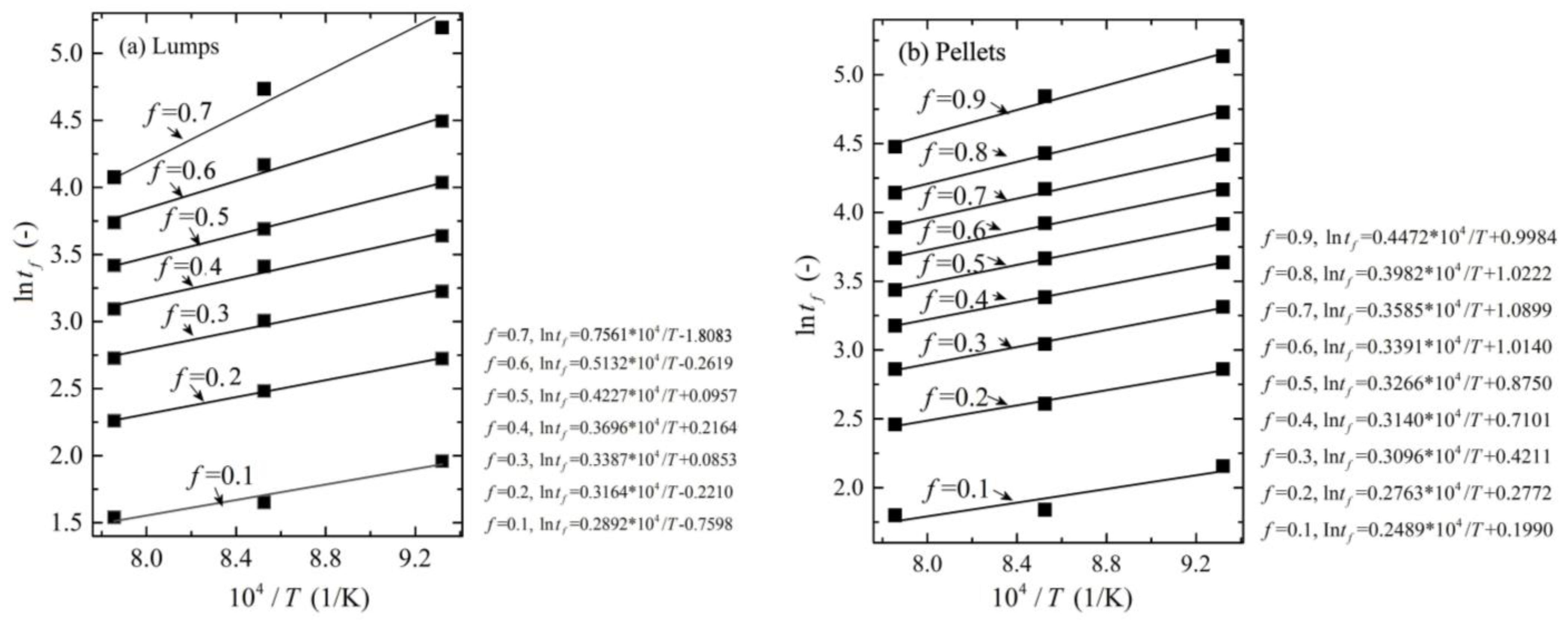

3.4. Reduction Kinetics

4. Conclusions

- The lumps had 60.15 wt.% total iron, 11.04 wt.% Fe2+ ions, and 0.83 wt.% phosphorus, and consisted of multiple oolites. In contrast, the pellets had 56.01 wt.% total iron, 0.86 wt.% Fe2+ ions and 0.73 wt.% phosphorus, and no oolitic structures existed in the pellets.

- Under the temperature range from 1073 K to 1273 K, and the concentration range of H2 from 25 vol.% to 100 vol.%, the maximum reduction fraction of lumps was 0.81, whereas the pellets reached a full reduction.

- During the reduction, the lumps retained the oolitic structure, with fayalite forming in the early stage, and glassy phases appearing in the later stage. In contrast, the pellets showed growth and agglomeration of iron particles, with negligible formation of fayalite or glassy phase.

- The reduction in lumps was controlled by internal gas diffusion under f < 0.3, by internal gas diffusion and interfacial chemical reactions under 0.3 < f < 0.6, by interface chemical reactions under 0.6 < f < 0.7, and by solid-state diffusion of ion under f > 0.7. The reduction in pellets was controlled by internal gas diffusion under f < 0.6, controlled by both internal gas diffusion and interfacial chemical reaction under f > 0.6.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereira, A.C.; Papini, R.M. Processes for phosphorus removal from iron ore—A review. Rem-Rev. Esc. Minas 2015, 68, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.H.; Gao, X.; Sohn, I.L.; Ueda, S.; Wang, W. Review of beneficiation techniques and new thinking for comprehensive utilization of high-phosphorus iron ores. Miner. Eng. 2025, 223, 109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, V.; Patra, S.; Dixit, P.; Mukherjee, A.K. Review on high phosphorous in iron ore: Problem and way out. Min. Metall. Explor. 2024, 41, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendaikha, W.; Larbi, S.; Ramdane, A. Mineralogical and chemical characterization of an oolitic iron ore, and sustainable phosphorus removal. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2024, 124, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.X.; Campos-Toro, E.F.; Zhang, Y.M.; Lopez-Valdivieso, A. Morphological and mineralogical characterizations of oolitic iron ore in the Exi region, China. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2013, 20, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baioumy, H.; Omran, M.; Fabritius, T. Mineralogy, geochemistry and the origin of high-phosphorus oolitic iron ores of Aswan, Egypt. Ore Geol. Rev. 2017, 80, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Kai, Z.; Zhen, W. Studying on mineralogical characteristics of a refractory high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoegbu, S.U. Technological challenges of phosphorus removal in high-phosphorus ores: Sustainability implications and possibilities for greener ore processing. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sun, T.; Kou, J.; Xu, H. A new iron recovery and dephosphorization approach from high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore via oxidation roasting-gas-based reduction and magnetic separation process. Powder Technol. 2023, 413, 118043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sun, T.; Kou, J.; Li, X.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z. Influence of sodium salts on reduction roasting of high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore. Miner. Process Extr. Metall. Rev. 2022, 43, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, K.; Zhang, F. Flotation dephosphorization of high-phosphorus oolitic ore. Minerals 2023, 13, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Yassin, A.A. Integrated roasting and acid leaching for phosphorus removal from high-p oolitic hematite ore: A case study from el Bagrawiya, Sudan. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 44, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, H.; Huang, J. Efficient iron recovery and dephosphorization from high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore: Process optimization and mineralogy. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.D.; Giese, E.C.; Medeiros, G.A.D.; Fernandes, M.T.; Castro, J.A.D. Evaluation of the use of burkolderia caribensis bacteria for the reduction of phosphorus content in iron ore particles. Mater. Res. 2022, 25, e20210427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Wu, X.; Chi, R. Dephosphorization of high-phosphorus iron ore using different sources of aspergillus niger strains. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2015, 176, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, C.; Li, S.; Cao, W. Fe–P alloy production from high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore via efficient pre-reduction and smelting separation. Minerals 2025, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Q.; Guo, L.; Guo, Z. A novel direct reduction-flash smelting separation process of treating high-phosphorus iron ore fines. Powder Technol. 2021, 377, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ni, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H. Fe-based amorphous alloys with superior soft-magnetic properties prepared via smelting reduction of high-phosphorus oolitic iron ore. Intermetallics 2022, 141, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Q.; Guo, Z.C.; Zhao, Z.L. Phosphorus removal of high phosphorus iron ore by gas-based reduction and melt separation. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2010, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Q.; Liu, W.D.; Zhang, H.Y.; Guo, Z.C. Effect of microwave treatment upon processing oolitic high-phosphorus iron ore for phosphorus removal. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2014, 45, 1683–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.C.; Tang, H.Q.; Li, B.K.; Zhou, Z.P. A Method of Utilization of the Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron Ore. Chinese Patent CN202210901575.5A, 28 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Tang, H. Research on pellet hydrogen reduction followed by melting separation for utilizing oolitic high-phosphorus iron ore. In TMS Annual Meeting & Exhibition 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 2034–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Q.; Qi, T.F.; Qin, Y.Q. Production of low-phosphorus molten iron from high-phosphorus oolitic hematite using biomass char. JOM 2015, 67, 1956–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.Q.; Ma, L.; Wang, J.W.; Guo, Z.C. Slag/metal separation process of gas-reduced oolitic high-phosphorus iron ore fines. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2014, 21, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobeinikov, Y.; Meshram, A.; Harris, C.; Kovtun, O.; Govro, J.; O’Malley, R.J.; Sridhar, S. Reduction of iron-ore pellets using different gas mixtures and temperatures. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2300066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Pang, K.; Barati, M.; Meng, X. Hydrogen-based reduction technologies in low-carbon sustainable ironmaking and steelmaking: A review. J. Sustain. Metall. 2024, 10, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Bu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, J.; Xue, Q.; Wang, J.; Guo, H.; Zuo, H. The low-carbon production of iron and steel industry transition process in China. Steel Res. Int. 2024, 95, 2300500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. Sustainable transition pathways for steel manufacturing: Low-carbon steelmaking technologies in enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Chu, M.S.; Li, F.; Feng, C.; Liu, Z.G.; Zhou, Y.S. Development and progress on hydrogen metallurgy. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2020, 27, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, M.; Csereklyei, Z.; Aisbett, E.; Rahbari, A.; Jotzo, F.; Lord, M.; Pye, J. Zero-carbon steel production: The opportunities and role for Australia. Energy Policy 2022, 163, 112811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Yang, H.; Tian, G.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Yu, X. Direct reduction of iron to facilitate net zero emissions in the steel industry: A review of research progress at different scales. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 140933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schéele, J. Pathways towards full use of hydrogen as reductant and fuel. Mater. Tech. 2023, 111, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Tang, H. Reduction kinetics of high-phosphorus iron ore pellet under hydrogen atmosphere. In TMS Annual Meeting and Exhibition 2025; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H. Reaction behavior of biochar composite briquette under H2-N2 atmosphere: Experimental study. Metals 2025, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.Z.; Gao, S.L.; Zhao, Q.F.; Shi, Q.Z.; Zhang, T.L.; Zhang, J.J. Kinetics of Thermal Analysis; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, T.P. Assessment of apparent activation energies for reduction reactions of iron oxides by hydrogen. J. Iron Steel Res. 1999, 6, 9–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Fe2O3 | Fe3O4 | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | P2O5 | MgO | LOI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31.76 | 46.14 | 8.28 | 4.22 | 2.74 | 1.68 | 0.40 | 4.78 | 100 |

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | Fe2O3 | K2O | TiO2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 63.57 | 18.24 | 4.97 | 4.29 | 4.16 | 2.44 | 2.22 | 0.11 | 100 |

| Total Iron | Fe2+ Ions | Phosphorus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lumps | 60.08 | 11.69 | 0.80 |

| Pellets | 56.01 | 0.86 | 0.73 |

| Reduction Fraction/- | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumps (kJ/mol) | 24.05 | 26.31 | 28.18 | 30.73 | 35.14 | 42.67 | 62.86 | — | — |

| Pellets (kJ/mol) | 20.70 | 22.97 | 25.74 | 26.11 | 27.16 | 28.19 | 29.80 | 33.11 | 37.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, H. Comparative Study on Reduction in Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron-Ore Lumps and Pellets Under H2 Atmosphere. Metals 2025, 15, 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121319

Ma H, Liu Y, Tang H. Comparative Study on Reduction in Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron-Ore Lumps and Pellets Under H2 Atmosphere. Metals. 2025; 15(12):1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121319

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Haoting, Yan Liu, and Huiqing Tang. 2025. "Comparative Study on Reduction in Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron-Ore Lumps and Pellets Under H2 Atmosphere" Metals 15, no. 12: 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121319

APA StyleMa, H., Liu, Y., & Tang, H. (2025). Comparative Study on Reduction in Oolitic High-Phosphorus Iron-Ore Lumps and Pellets Under H2 Atmosphere. Metals, 15(12), 1319. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15121319