Investigation of Single-Pass Laser Remelted Joint of Mo-5Re Alloy: Microstructure, Residual Stress and Angular Distortion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Molybdenum-Rhenium Alloy Laser Remelted Joint

2.2. Observation of Microstructure and Measurement of Hardness

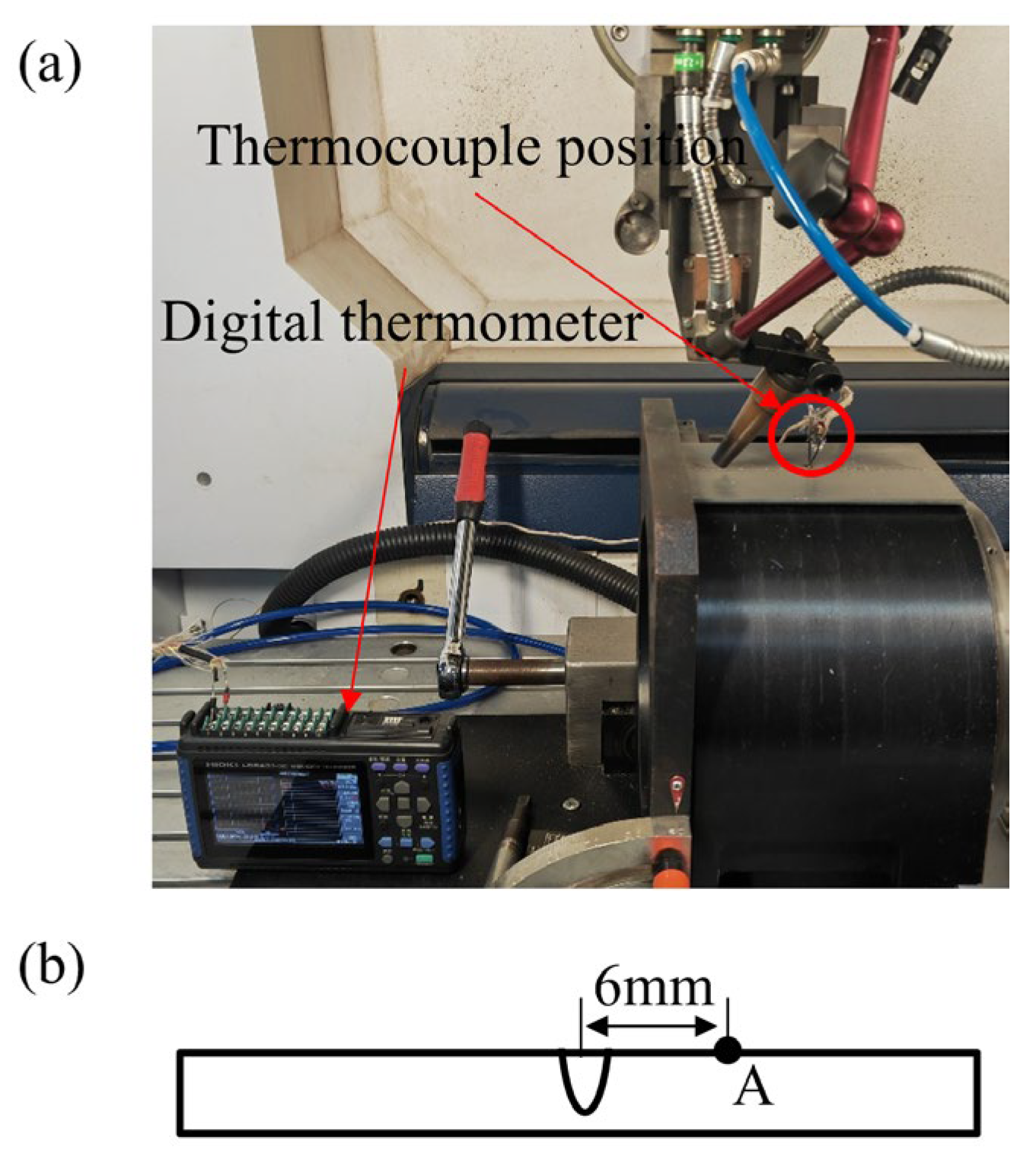

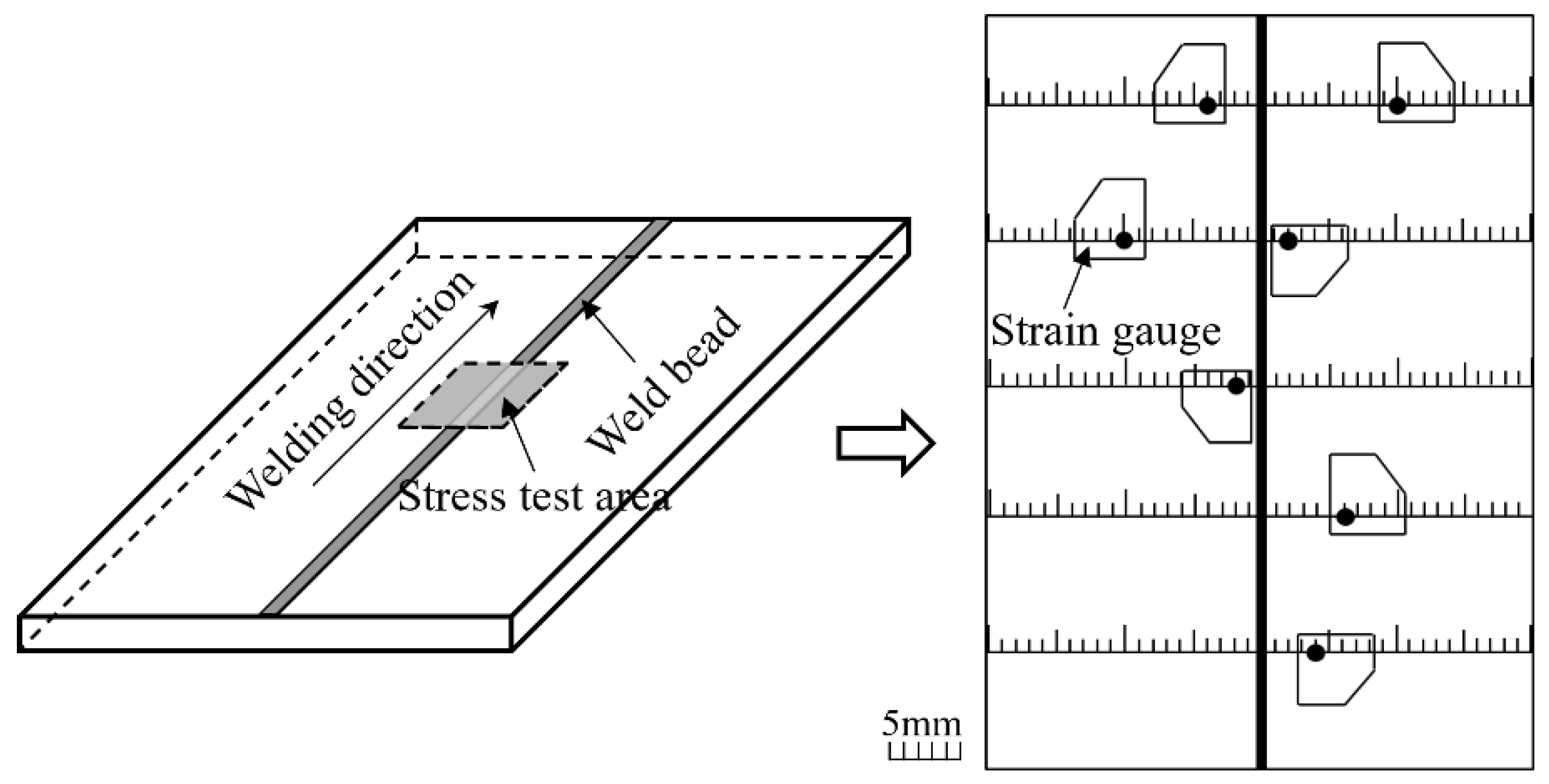

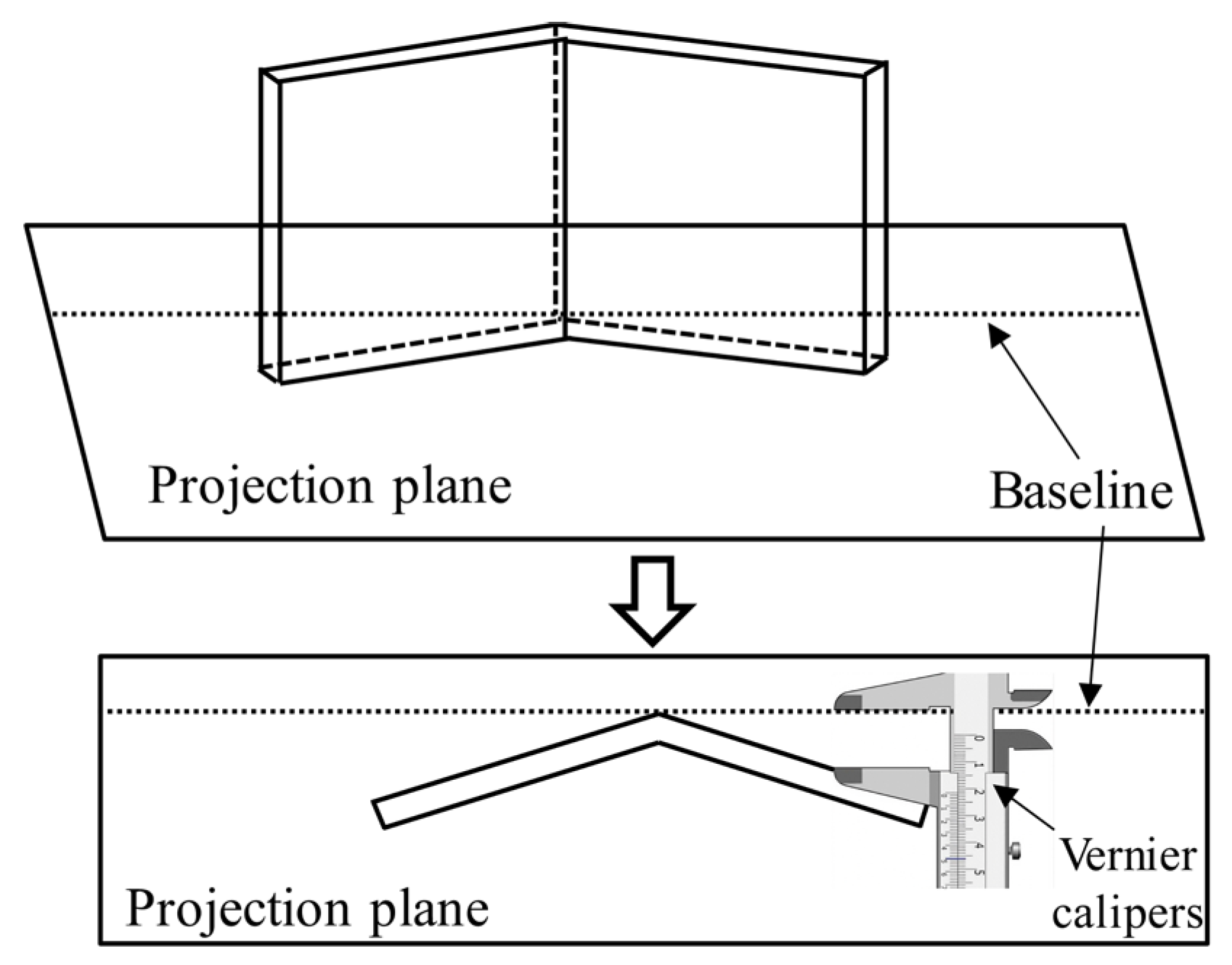

2.3. Measurement of Welding Thermal Cycle, Residual Stress and Weld Deformation

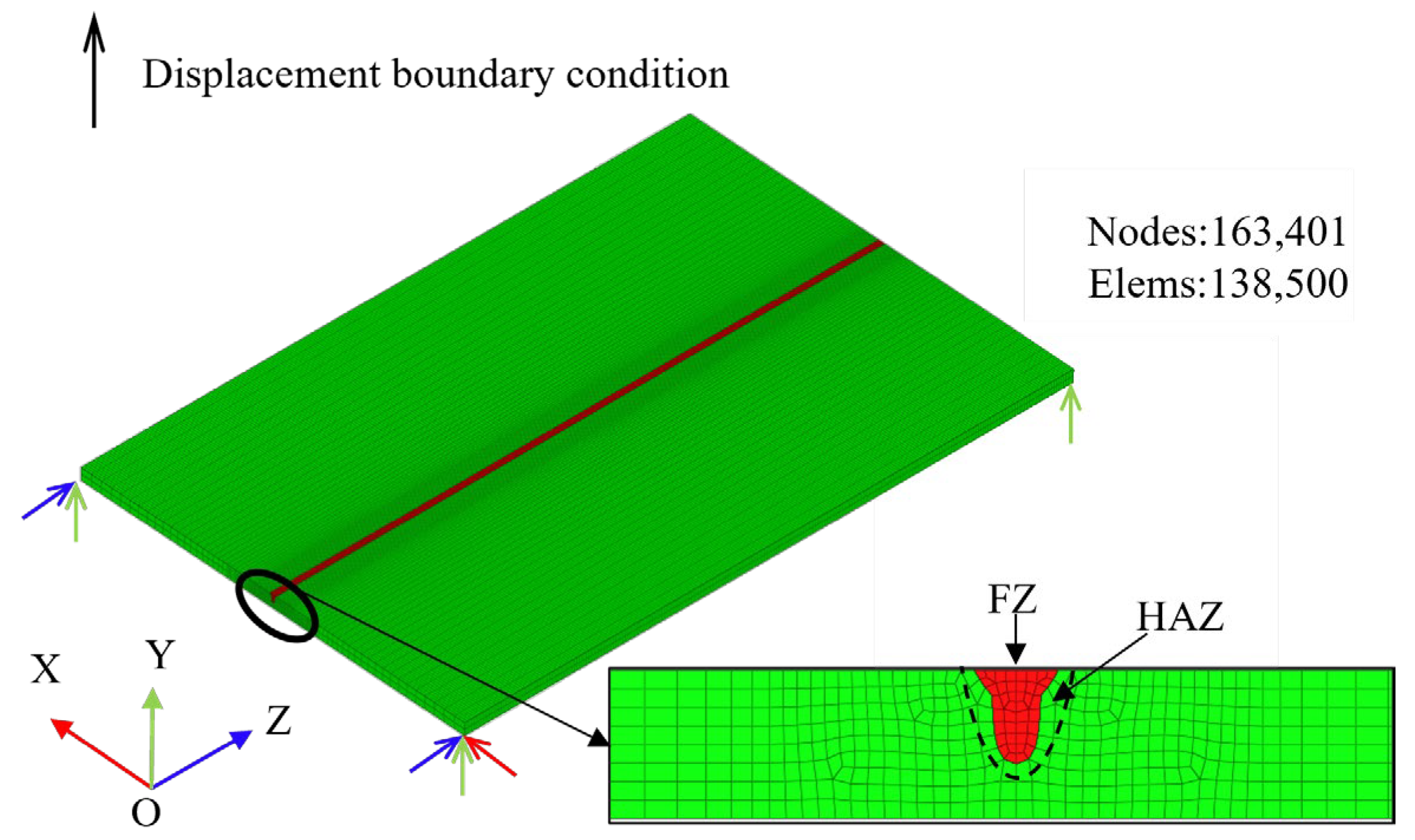

3. Finite Element Analysis

3.1. Thermal Analysis

3.2. Mechanical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Microstructure and Hardness of the Mo-5Re Alloy Laser Remelted Joint

4.1.1. Microstructural Characterization of the Mo-5Re Alloy Remelted Joint

4.1.2. Microhardness Distribution of the Mo-5Re Alloy Remelted Joint

4.2. Temperature Field, Residual Stresses, and Welding Deformation in the Mo-5Re Alloy Laser Remelted Joint

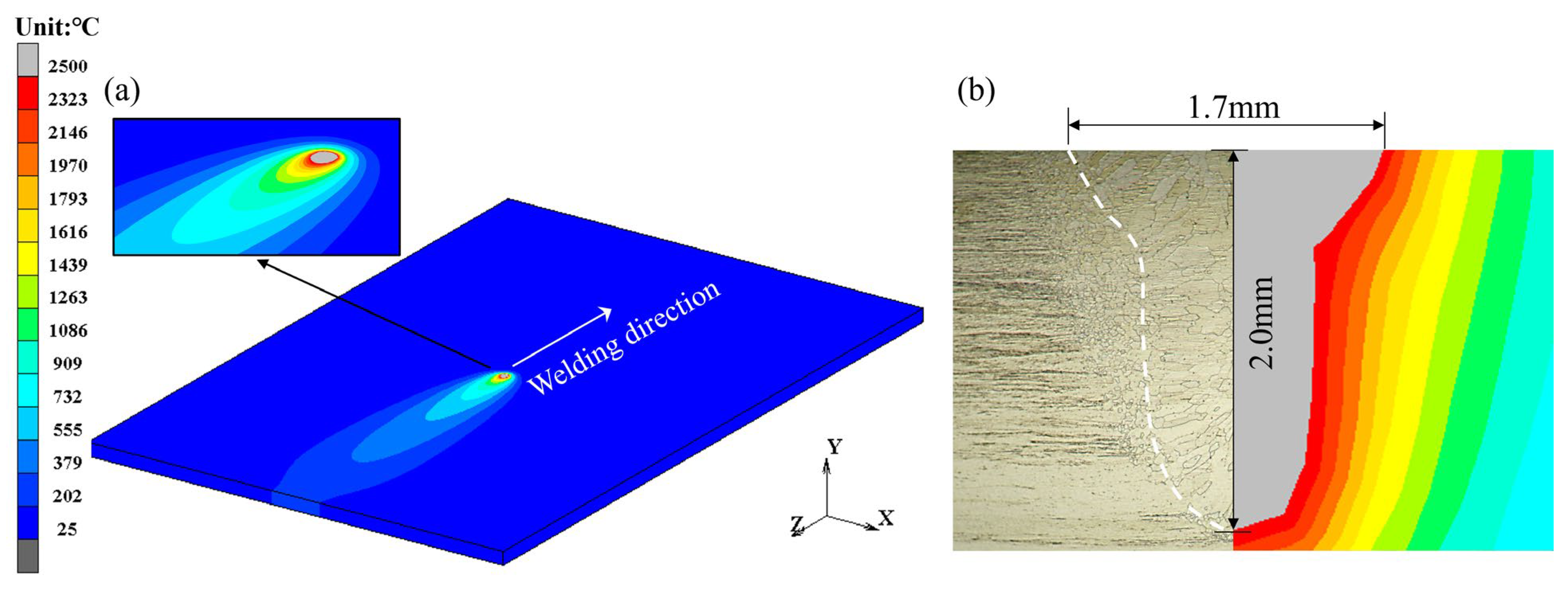

4.2.1. Temperature Field of the Remelted Joint

4.2.2. Residual Stress Distribution in the Remelted Joint

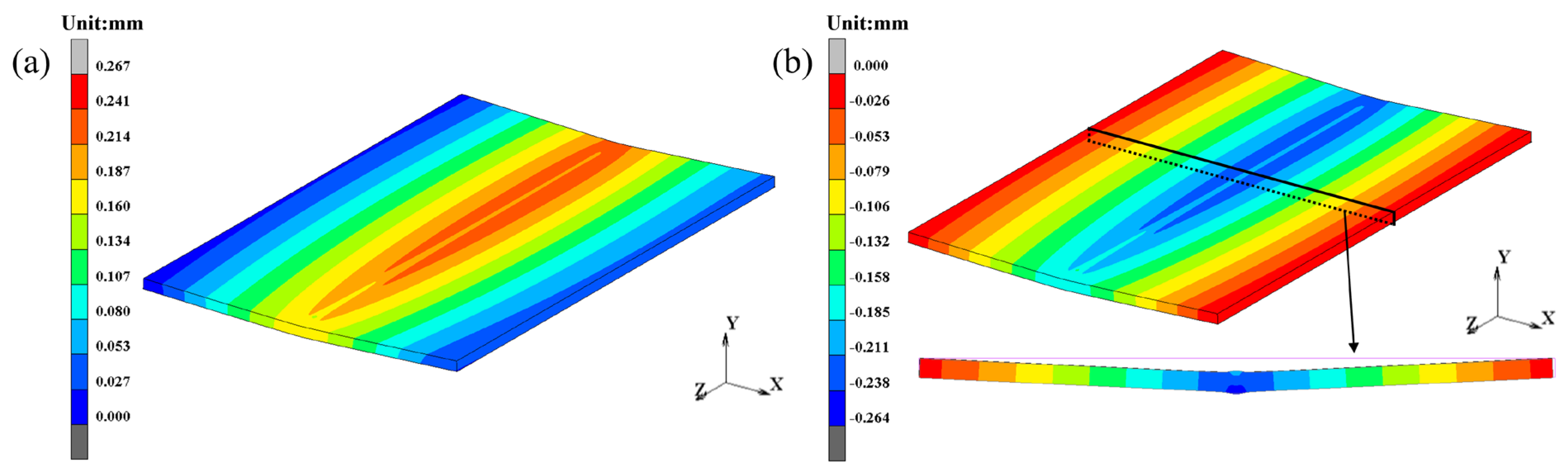

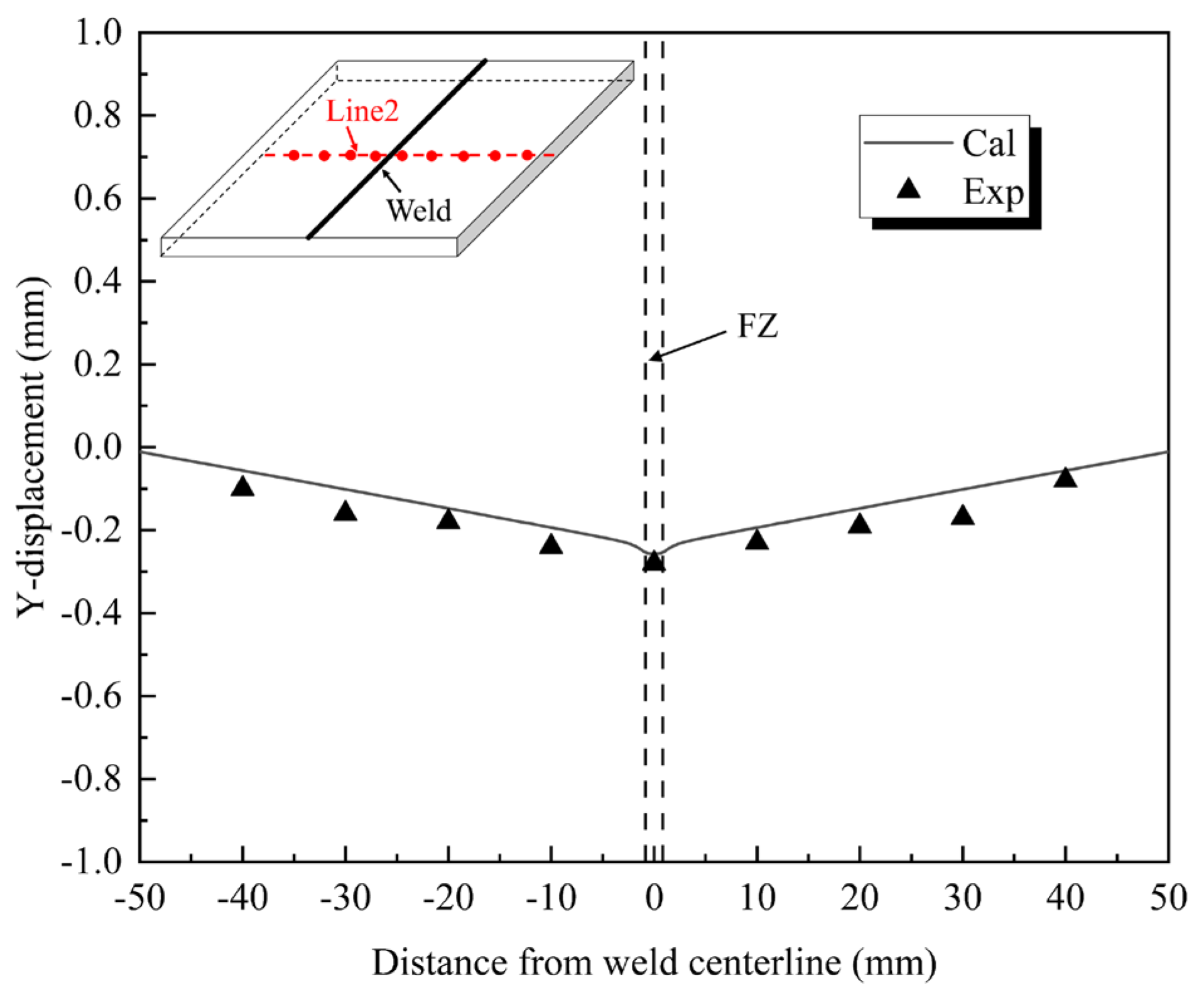

4.2.3. Welding Deformation Distribution of the Remelted Joint

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leclercq, A.; Czech, A.; Mouret, T.; Lis, M.; Wrona, A.; Brailovski, V. Molybdenum 8wt% rhenium alloy processed by laser powder bed fusion: From powder production to mechanical testing at elevated temperatures. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 132, 107266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Quan, C.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, H.; Wang, L. Strengthening-toughening mechanism of carbon-coated TiC/ZrC secondary phase doping molybdenum alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. 2025, 929, 148096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Duan, B.; Wang, D.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X. Preparation, microstructure and mechanical properties of a Ce-PSZ reinforced molybdenum alloy. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 131, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.; Umstead, W.; Xu, J.; Zhai, T. Resistance spot welding of 50Mo-50Re refractory alloy foils. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Vacuum Electronics Conference, Monterey, CA, USA, 22–24 April 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Jiang, X.P.; Zeng, Q.; Zhai, T.G.; Leonhardt, T.; Farrell, J.; Umstead, W.; Effgen, M.P. Optimization of resistance spot welding on the assembly of refractory alloy 50Mo-50Re thin sheet. J. Nucl. Mater. 2007, 366, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Zhai, T.G. The small-scale resistance spot welding of refractory alloy 50Mo-50Re thin sheet. JOM 2008, 60, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Dai, J.; Li, C. Synergistic back stress and Pd-induced heterogeneous microstructure design for high-performance Mo-5Re/Nb-1Zr brazed joints. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 133, 107363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.Z.; Wu, L.; Xu, X.P.; Zou, J.S. Phase constitution and fracture analysis of vacuum brazed joint of 50Mo-50Re refractory alloys. Vacuum 2017, 136, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Sun, Y.F.; Kato, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of friction stir welded pure Mo joints. Scr. Mater. 2011, 64, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernig, B.; Reheis, N. Joining of molybdenum and its application. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2010, 28, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Feng, K.Y.; Zhang, G.M. A novel study on laser lap welding of refractory alloy 50Mo-50Re of small-scale thin sheet. Vacuum 2017, 136, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.P.; Mcdougal, J.R.; Booher, B.A.; Ruhkamp, J.D.; Kwiatkowski, J.J. Electron Beam and Nd-Yag Laser Welding of Niobium-1% Zirconium and Molybdenum-44.5% Rhenium Thin Select Material. In Proceedings of the Energy Conversion Engineering Conference & Exhibit IEEE, Denver, CO, USA, 15–19 September 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, G.; Sun, J.; Sun, Y.J.; Cao, W.C.; Zhu, Q.; Bai, Q.L.; Zhang, L.J. Fiber laser welding of fuel cladding and end plug made of La2O3 dispersion-strengthened molybdenum alloy. Materials 2018, 11, 1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, H.D.; Zhang, L.J.; Ning, J.; An, G.; Zhang, L.L. Regulation of performance of laser-welded socket joint of Mo-14Re ultra-high-temperature heat pipe by introducing Ti into both weld and heat affected zone. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Yang, Q.J. Weldability of molybdenum-rhenium alloy based on a single-mode fiber laser. Metals 2022, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, X.D.; Zhao, L.B.; Li, Z.J. Effect of long-term thermal exposure on microstructure of laser-welded UNS N10003 alloy. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2024, 35, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Pei, J.Y.; Zhang, L.L.; Long, J.; Zhang, J.X.; Na, S.J. Laser seal welding of end plug to thin-walled nanostructured high-strength molybdenum alloy cladding with a zirconium interlayer. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 267, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Long, J.; Ning, J.; Zhang, J.X.; Na, S.J. Effects of titanium on grain boundary strength in molybdenum laser weld bead and formation and strengthening mechanisms of brazing layer. Mater. Design 2019, 169, 107681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.X.; Li, Y.X.; Shang, X.T.; Wang, X.W.; Pei, J.Y. Effect of heat input on porosity defects in a fiber Laser welded socket-joint made of powder metallurgy molybdenum alloy. Materials 2019, 12, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.X.; Li, Y.X.; Shang, X.T.; Wang, X.W.; Pei, J.Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a fiber welded socket-joint made of powder metallurgy molybdenum alloy. Metals 2019, 9, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Pei, J.Y.; Ning, J.; Zhang, L.L.; Long, J.; Zhang, G.F.; Zhang, J.X.; Na, S.J. Effects of power modulation, multipass remelting and Zr addition upon porosity defects in laser seal welding of end plug to thin-walled molybdenum alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2019, 41, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.X.; Yang, J.Z.; Wang, S.C.; Wang, X.J.; Xing, H.R.; Hu, B.L.; Wang, L.; Muzamil, M.; Wang, Q.; Feng, R.; et al. Crack generation and propagation mechanism of Mo-14Re alloy laser welding. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 121, 106684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Liu, J.Z.; Bai, Q.L.; Wang, X.W.; Sun, Y.J.; Li, S.G.; Gong, X. Effect of preheating on the microstructure and properties of fiber laser welded girth joint of thin-walled nanostructured Mo alloy. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 78, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Chen, G.Q.; Cao, H.; Liu, R.C.; Zhang, B.G.; Leng, X.S. Uncovering the weakening mechanism of electron beam welded joints of La2O3 dispersion strengthened molybdenum alloy: Experiment and simulation. Mater. Lett. 2023, 333, 133586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 31310-2014; Determination of Residual Stress in Metal Materials by the Hole-Drilling Strain Method. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Goldak, J.; Chakravarti, A.; Bibby, M. A new finite element model for welding heat sources. Metall. Trans. B 1984, 15, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.Z.; Cheng, H.M.; Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Ye, Y.H.; Deng, D.A. Numerical simulation of residual stress and welding deformation for high strength steel Q960E butt-welded joints. China Mech. Eng. 2023, 34, 2095–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muránsky, O.; Hamelin, C.J.; Smith, M.C.; Bendeich, P.J.; Edwards, L. The effect of plasticity theory on predicted residual stress fields in numerical weld analyses. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2012, 54, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.J.; Yu, H.; Zeng, X.L.; Sun, G.; Ding, X.D.; Sun, Y.J. Influences of Si-Ti combined alloying on microstructures and properties of laser welded socket joints of molybdenum. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 175, 110749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhong, W.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; He, X.F. Microstructure transformation and pore formation mechanism of Mo-14Re alloy weld by vacuum electron beam welding. Vacuum 2023, 218, 112594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | K | Na | Mn | Sn | Ca | Fe | C | N | O | Re | Mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | ≤0.002 | ≤0.002 | ≤0.0015 | ≤0.001 | ≤0.0002 | ≤0.0055 | 0.0037 | <0.0003 | 0.0013 | 5 | Bal. |

| Welding Parameters | Power (W) | Speed (m·min−1) | Spot Diameter (mm) | Defocus (mm) | Gas Flow Rate (L·min−1) | Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 2800 | 2 | 0.533 | 2.21 | 20 | 0.9 |

| Heat Source Parameters | a1 | a2 | b | c | H1 | H | r0 | n1 | n2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.45 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.45 | 0.5 | 0.35 | 0.65 |

| Temperature (K) | Density (kg·m−3) | Thermal Conductivity (W·m−1·K−1) | Specific Heat (J·kg−1·K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 10,500 | 74 | 240 |

| 473 | 74 | 240 | |

| 673 | 75 | 240 | |

| 873 | 77 | 250 | |

| 1073 | 79 | 260 | |

| 1273 | 85 | 280 | |

| 1473 | 93 | 320 | |

| 1673 | 87 | 320 | |

| 1873 | 87 | 320 |

| Temperature (K) | Linear Expansion (K−1) | Temperature (K) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 | 0.00000496 | 298 | 485 | 320 | 0.3 |

| 473 | 0.00000496 | 573 | 419 | 310 | 0.31 |

| 673 | 0.00000517 | 873 | 349 | 296 | 0.31 |

| 873 | 0.00000553 | 1173 | 228 | 282 | 0.32 |

| 1073 | 0.00000589 | 1373 | 210 | 270 | 0.32 |

| 1273 | 0.00000642 | 1573 | 185 | 255 | 0.31 |

| 1473 | 0.00000701 | 1773 | 120 | 232 | 0.3 |

| 1673 | 0.00000764 | 1873 | 120 | 232 | 0.3 |

| 1873 | 0.00000764 | — | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Peng, D.; Qiu, X.; Su, M.; Hu, S.; Li, W.; Deng, D. Investigation of Single-Pass Laser Remelted Joint of Mo-5Re Alloy: Microstructure, Residual Stress and Angular Distortion. Metals 2025, 15, 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101145

Wang Y, Peng D, Qiu X, Su M, Hu S, Li W, Deng D. Investigation of Single-Pass Laser Remelted Joint of Mo-5Re Alloy: Microstructure, Residual Stress and Angular Distortion. Metals. 2025; 15(10):1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101145

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yifeng, Danmin Peng, Xi Qiu, Mingwei Su, Shuwei Hu, Wenjie Li, and Dean Deng. 2025. "Investigation of Single-Pass Laser Remelted Joint of Mo-5Re Alloy: Microstructure, Residual Stress and Angular Distortion" Metals 15, no. 10: 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101145

APA StyleWang, Y., Peng, D., Qiu, X., Su, M., Hu, S., Li, W., & Deng, D. (2025). Investigation of Single-Pass Laser Remelted Joint of Mo-5Re Alloy: Microstructure, Residual Stress and Angular Distortion. Metals, 15(10), 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/met15101145