Austenite Formation in the Oxidized Layer of Ultra-High-Strength 13Ni15Co10Mo Maraging Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

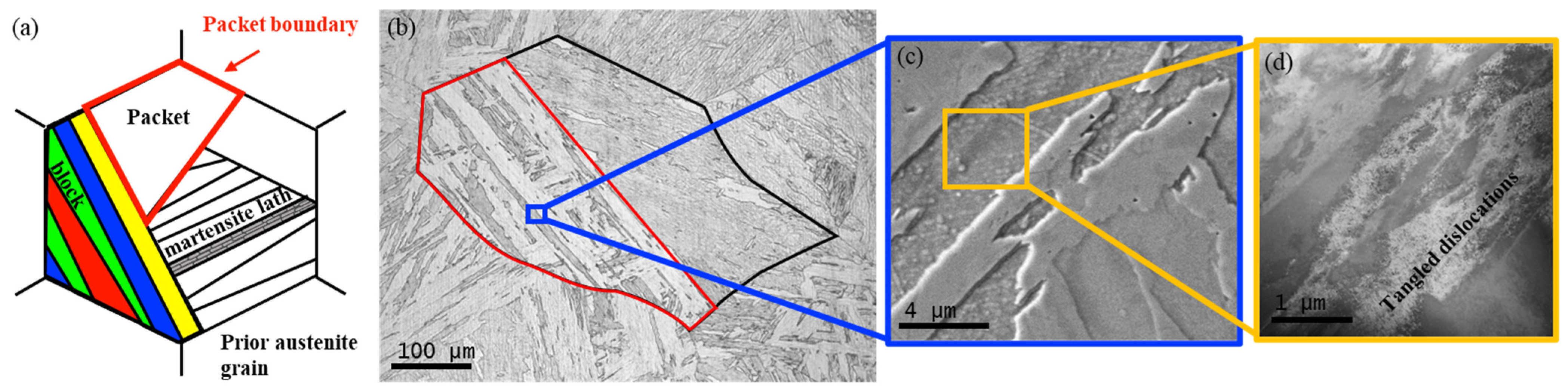

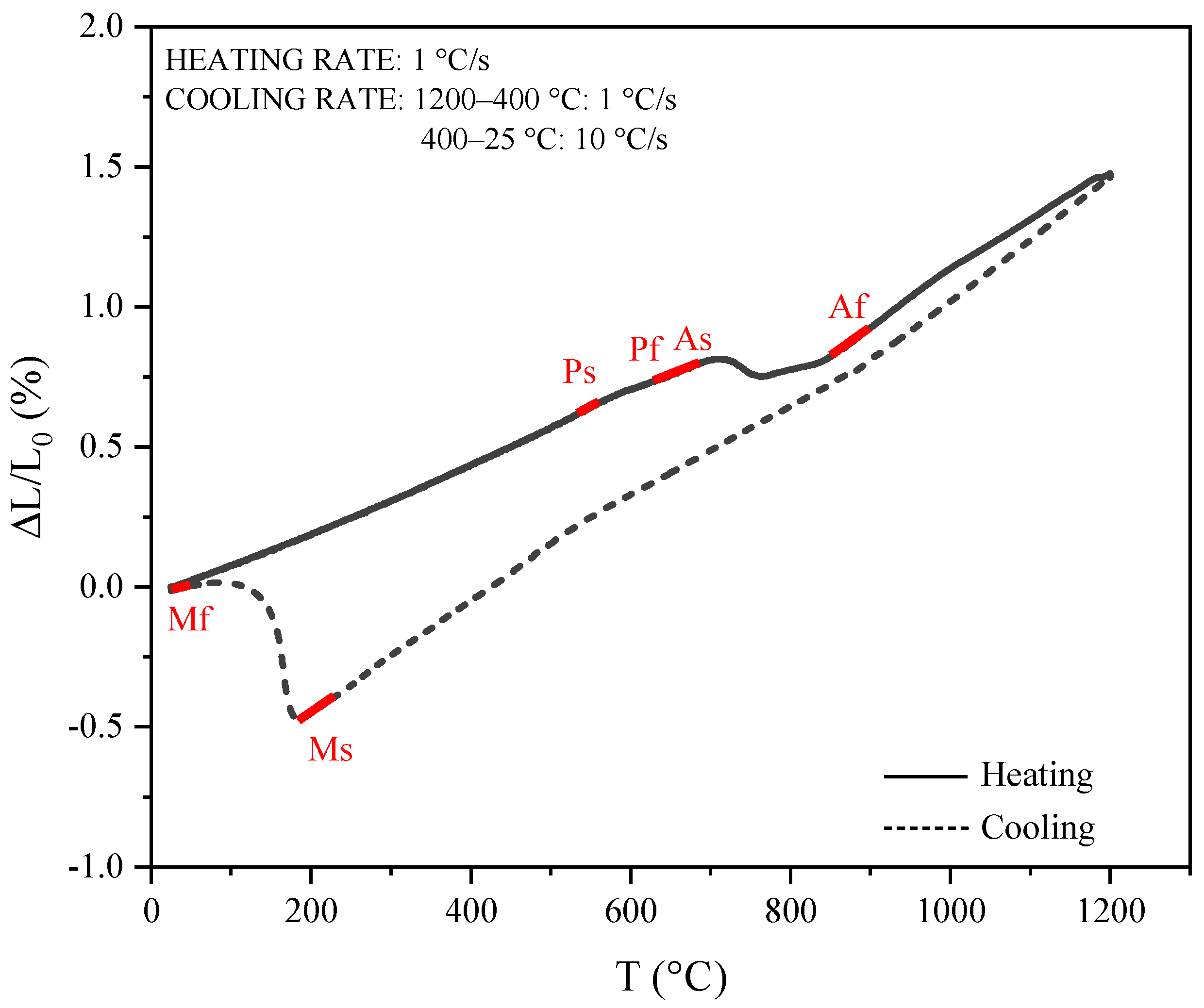

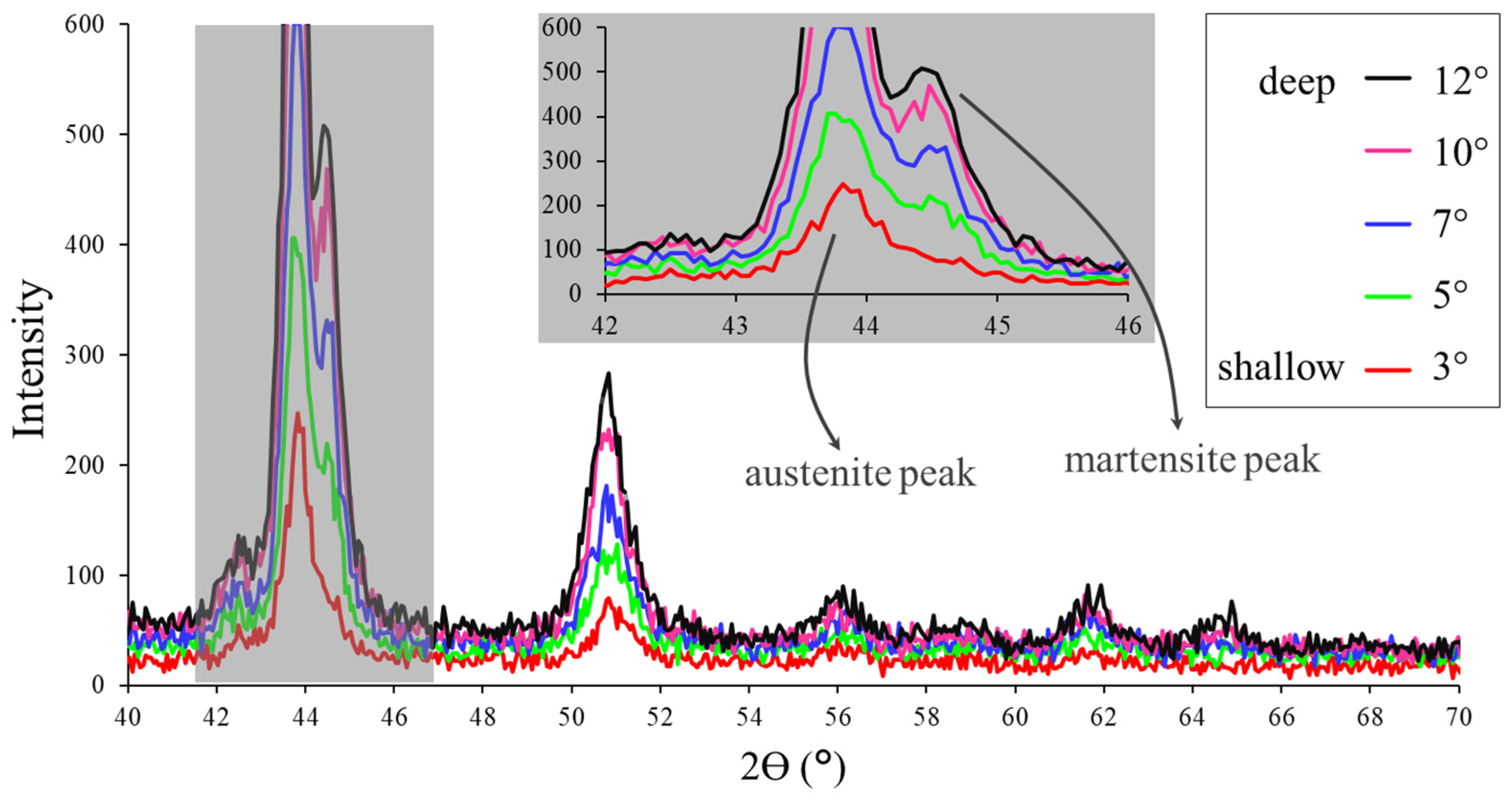

3.1. Bulk Microstructure

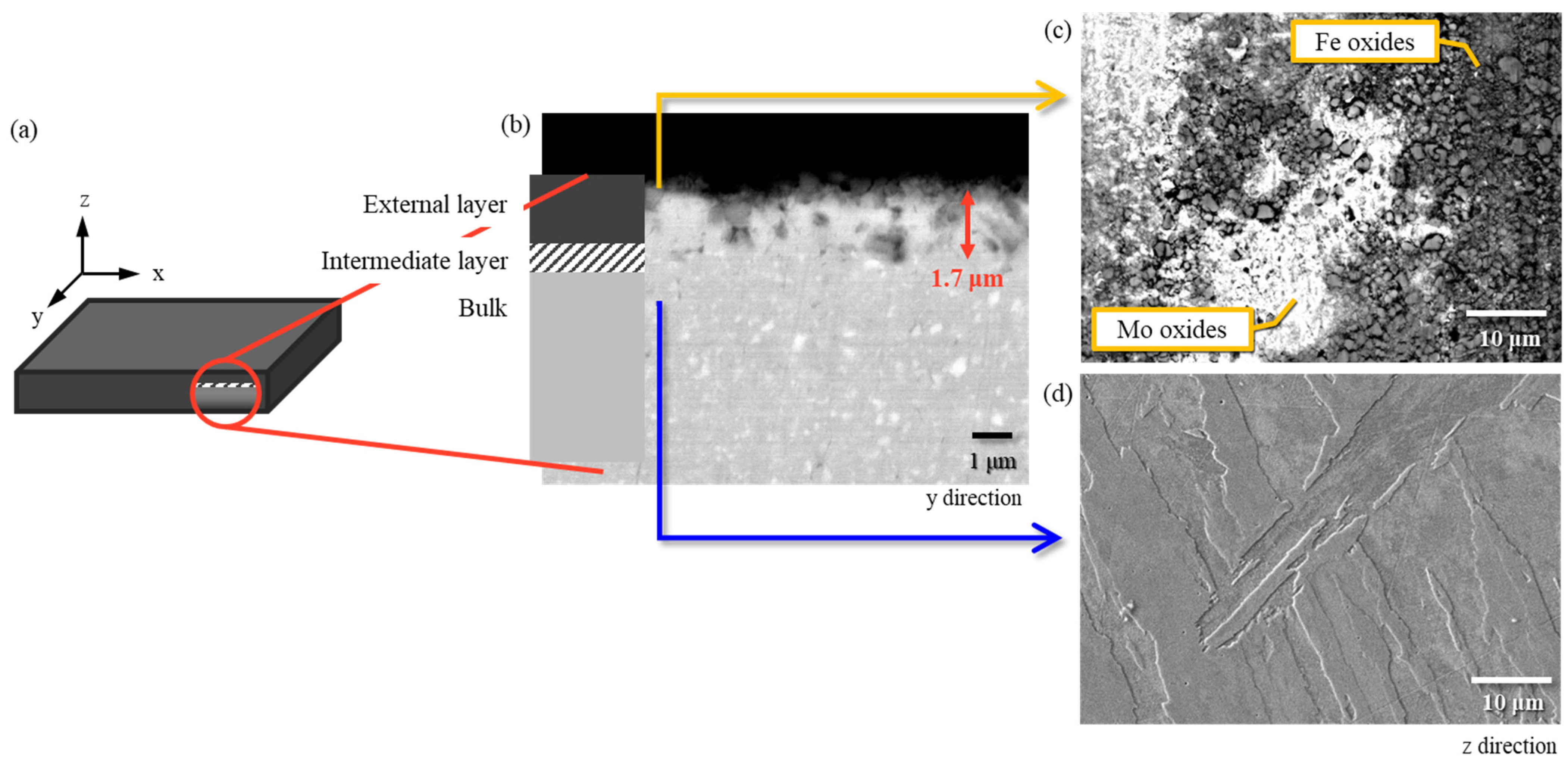

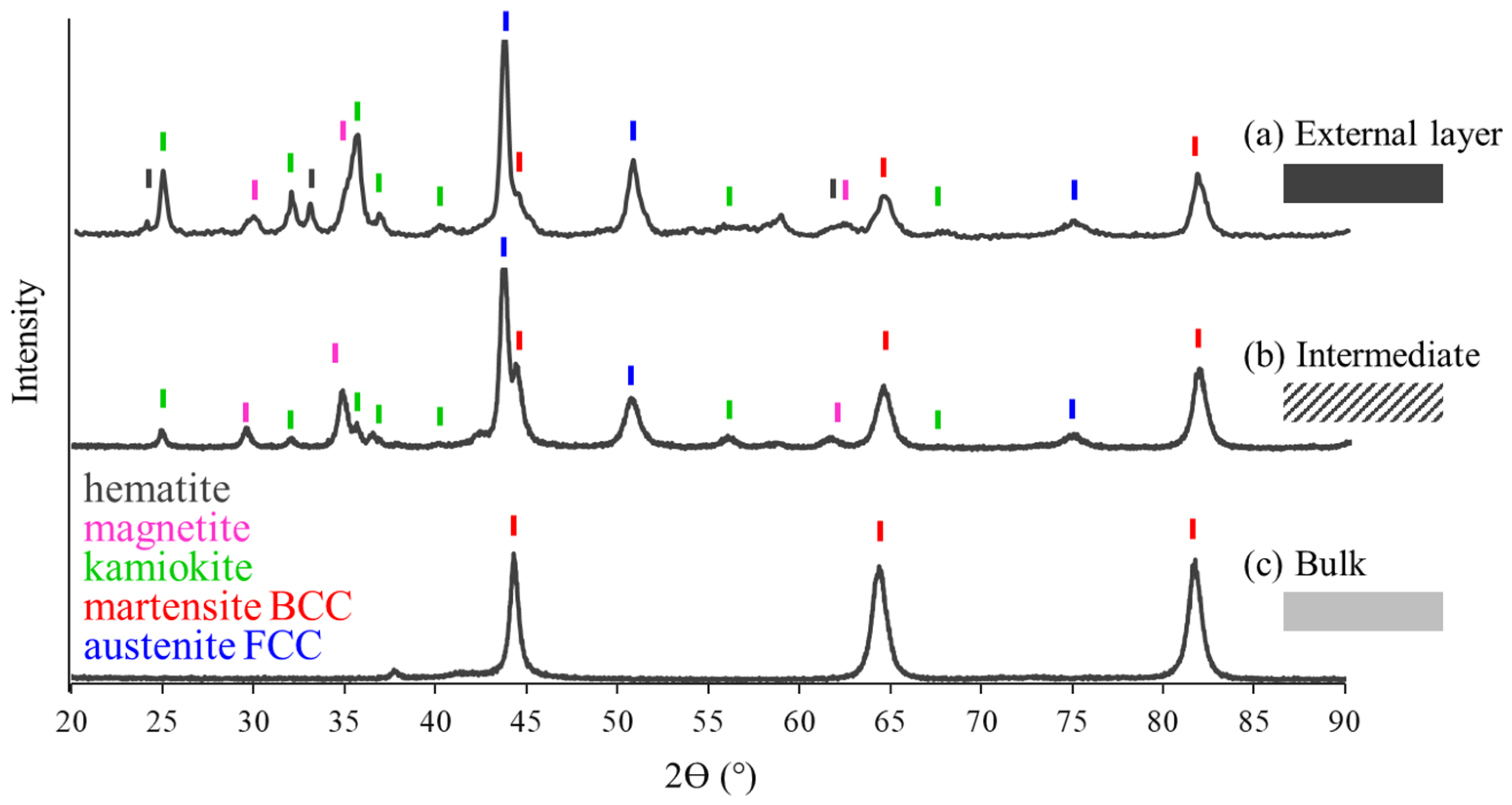

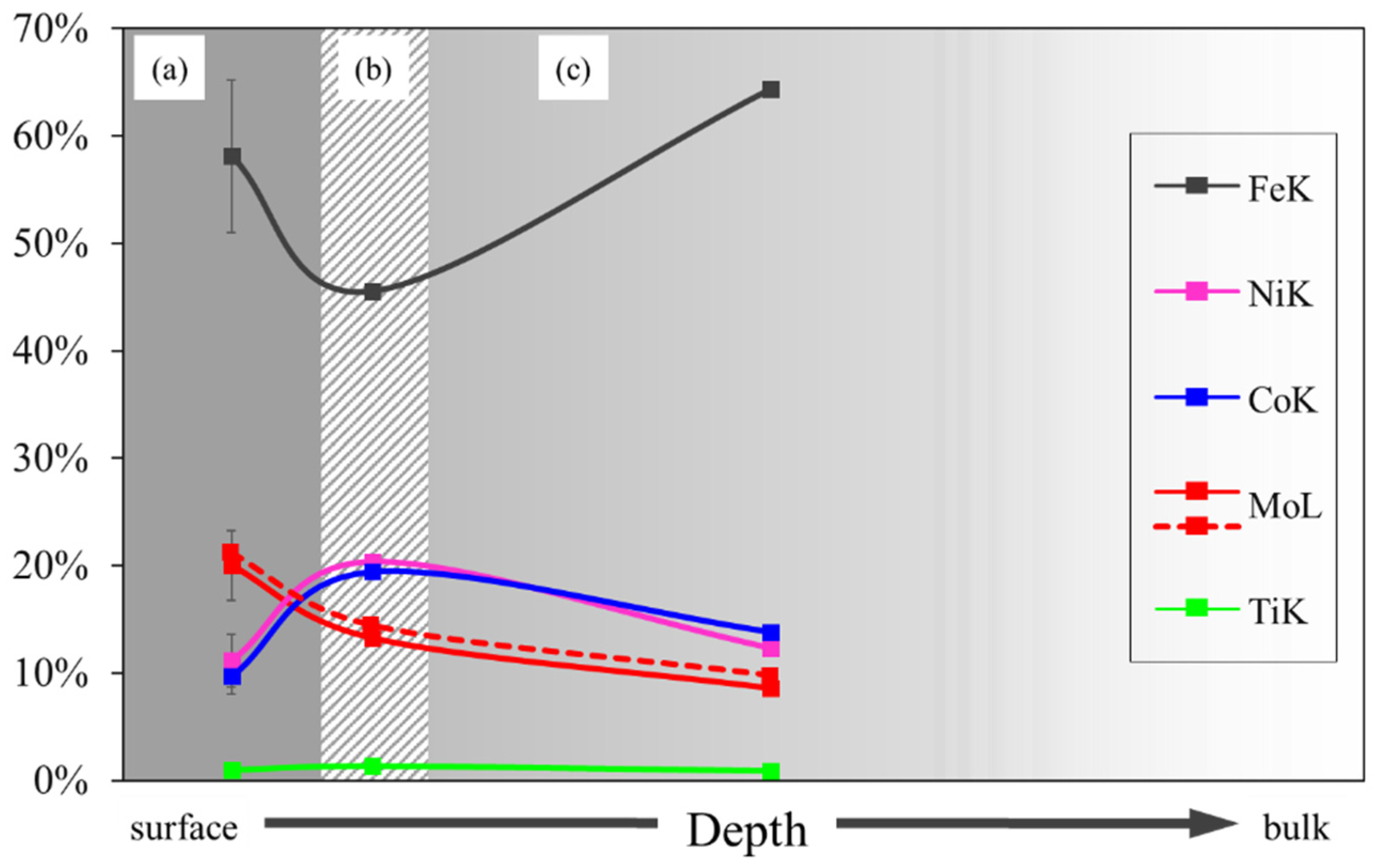

3.2. External, Intermediate and Bulk Microstructure

4. Conclusions

- Increase in the austenite stabilization field, due to the cobalt content.

- Formation of kamiokite, hematite and magnetite oxides on the steel surface during exposure to high temperatures, due to the high Mo content.

- Migration of cobalt and nickel atoms towards the bulk during the formation of oxides.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, M.N. Progress in Understanding the Metallurgy of 18% Nickel Maraging Steels. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2006, 97, 1594–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floreen, S. Maraging Steels. In Metals Handbook–VOLUME 1: Properties and Selection, Irons and Steels; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1978; pp. 445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hornbogen, E.; Rittner, K. Development of Thermo-Mechanical Treatments of a Maraging Steel for Yield Strengths above 3 GPa. Steel Res. 1987, 58, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, J.; Klaar, H.-J. Systematische Gefiigeuntersuchungen Am Martensitaushirtenden Stahl X 2 NiCoMo 13 15 10. Steel Res. 1990, 61, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, D.P.M.; Melo Feitosa, A.L.; de Carvalho, L.G.; Plaut, R.L.; Padilha, A.F. A Short Review on Ultra-High-Strength Maraging Steels and Future Perspectives. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, 20200470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, T.J.B.; Nunes, G.C.S.; Tupan, L.F.S.; Sarvezuk, P.W.C.; Ivashita, F.F.; de Oliveira, C.A.S.; Paesano, A. Aging-Induced Transformations of Maraging-400 Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A Phys. Metall. Mater. Sci. 2018, 49, 3441–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, U.K.; Dey, G.K.; Asundi, M.K. Precipitation Hardening in 350 Grade Maraging Steel. Metall. Trans. A 1993, 24, 2429–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, K.; Qu, W.; Kong, F.; Su, G. Strengthening and Toughening of a 2800-MPa Grade Maraging Steel. Mater. Lett. 2002, 56, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawad, S.A.; Nasr, A.; Fekry, A.M.; Filippov, L.O. Electrochemical and Hydrogen Evolution Behaviour of a Novel Nano-Cobalt/Nano-Chitosan Composite Coating on a Surgical 316L Stainless Steel Alloy as an Implant. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 18233–18241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baioumy, S.A.; Sanad, W.A.; El-Sherif, A.A.; Fekry, A.M.; Filippov, L.O. Electrochemical Behaviour and X-ray Fluorescence Study of AgNP-GO-CS Coated AISI 303 Austenitic Stainless Steel and Ceramic Commercial Products. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2021, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioumy, S.A.; Ahmed, R.A.; Fekry, A.M. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of Graphene Oxide/Chitosan/Silver Nanoparticle Composite Coating on Stainless Steel Utensils in Aqueous Media. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammam, R.H.; Fekry, A.M. Corrosion Behavior of 316L Stainless Steel Coated by Chitosan/Gold/Nickel Nanoparticles in Mixed Acid Mixture Containing Inorganic Anions. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2017, 12, 8991–9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Salam, H.M.A.; El-Hafez, G.M.A.; Askalany, H.G.; Fekry, A.M. A Creation of Poly(N-2-Hydroxyethylaniline-Co-2-Chloroaniline) for Corrosion Control of Mild Steel in Acidic Medium. J. Bio- Tribo-Corrosion 2020, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.E.; Sharon, J.; Yaniv, A.E. A Mechanism of Oxidation of Ferrous Alloys by Super-Heated Steam. Scr. Metall. 1981, 15, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.E.; Yaniv, A.E.; Sharon, J. The Oxidation Mechanism of Fe-Ni-Co Alloys. Oxid. Met. 1981, 16, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyling, C.J.; Kotzé, I.A.; Viljoen, P.E. The Kinetics of Oxide Film Growth on Maraging Steel as Described by Space-charge Effects. Surf. Interface Anal. 1990, 16, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Martins Cardoso, A.; da Igreja, H.R.; Garcia, P.S.P.; Chales, R.; Pardal, J.M.; Tavares, S.S.M.; da Silva, M.M.; Paesano, A.; Pichon, L. Structural Characterization of Iron Oxide Grown on 18% Ni-Co-Mo-Ti Ferrous Base Alloy Aged under Superheated Steam Atmosphere. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerra Florez, M.A.; Ribas, G.F.; Cardoso, J.L.; Mateo García, A.M.; Roa Rovira, J.J.; Bastos-neto, M.; de Abreu, H.F.G.; da Silva, M.J.G. Oxidation Behavior of Maraging 300 Alloy Exposed to Nitrogen/Water Vapor Atmosphere at 500 °C. Metals 2021, 11, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.E.; Levitzky, M.; Sharon, J. Depth profile compositional analysis of thin oxide films on Fe-Ni-Co alloys by AES-ESCA techniques. Corros. Rev. 1984, 6, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rezek, J.; Klein, I.E.; Yahalom, J. Structure and corrosion resistance of oxides grown on maraging steel in steam at elevated temperatures. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 108, 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rezek, J.; Klein, I.E.; Yahalom, J. Electrochemical properties of protective coatings on maraging steels. Corros. Sci. 1997, 39, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfistermeister, M.; Krapf, H.; Coester, E. Process for the Formation of an Anticorrosive, Oxide Layer on Maraging Steel. U.S. Patent 4.141.759, 27 February 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, A.d.A.; Brandi, S.D.; Padilha, A.F. Efeito Do Teor De Molibdênio Nas Curvas De Endurecimento Por Precipitação E Na Resistência À Oxidação a Altas Temperaturas De Aços Maraging De Ultra Alta Resistência Mecânica. Tecnol. Metal. Mater. Mineração 2015, 12, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, H.; Theisen, W. Ferrous Materials: Steel and Cast Iron; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; Volume 53, ISBN 9783540718475. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, L.G.d.; Andrade, M.S.; Plaut, R.L.; Souza, F.M.; Padilha, A.F. A Dilatometric Study of the Phase Transformations in 300 and 350 Maraging Steels During Continuous Heating Rates. Mater. Res. 2013, 16, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashanka, R.; Chaira, D. Optimization of Milling Parameters for the Synthesis of Nano-Structured Duplex and Ferritic Stainless Steel Powders by High Energy Planetary Milling. Powder Technol. 2015, 278, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Shashanka, R.; Chaira, D. Effect of Nanosize Yittria and Tungsten Addition to Duplex Stainless Steel during High Energy Planetary Milling. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 115, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashanka, R.; Chaira, D. Development of Nano-Structured Duplex and Ferritic Stainless Steels by Pulverisette Planetary Milling Followed by Pressureless Sintering. Mater. Charact. 2015, 99, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Salam, I.; Tauqir, A. Formation of solid-state dendrites in an alloy steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2004, 179, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeot, J.; Maitrepierre, P.; Manenc, J.; Thomas, B. Hardening Fe-Ni-Mo and Fe-Ni-Co-Mo Martensitic Alloys by Tempering. IRSID Int. Rep. No 116. Part I: Electron Microscope Study of Coherent Precipitation in Fe-Ni-Co-Mo Maraging Alloys. In Proceedings of the 5th International Materials Symposium, Berkeley, CA, USA, 13–17 September 1971; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Florez, M.A.C.; Ribas, G.F.; Rovira, J.J.R.; García, A.M.M.; Lima, M.N.d.; Perdrix, G.R.; Cardoso, J.L.; da Silva, M.J.G. Production and Characterization of Oxides Formed on Grade 300 and 350 Maraging Steels Using two Oxygen / Steam Rich Atmospheres. Mater. Res. 2022, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fe | Ni | Co | Mo | Ti | Al | Si | Mn | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal. | 12.85 | 15.64 | 10.49 | 0.721 | 0.052 | 0.040 | 0.040 | 0.016 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fonseca, D.P.M.d.; Carvalho, L.G.d.; Lima, N.B.d.; Padilha, A.F. Austenite Formation in the Oxidized Layer of Ultra-High-Strength 13Ni15Co10Mo Maraging Steel. Metals 2022, 12, 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12122115

Fonseca DPMd, Carvalho LGd, Lima NBd, Padilha AF. Austenite Formation in the Oxidized Layer of Ultra-High-Strength 13Ni15Co10Mo Maraging Steel. Metals. 2022; 12(12):2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12122115

Chicago/Turabian StyleFonseca, Daniela P. M. da, Leandro G. de Carvalho, Nelson B. de Lima, and Angelo F. Padilha. 2022. "Austenite Formation in the Oxidized Layer of Ultra-High-Strength 13Ni15Co10Mo Maraging Steel" Metals 12, no. 12: 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12122115

APA StyleFonseca, D. P. M. d., Carvalho, L. G. d., Lima, N. B. d., & Padilha, A. F. (2022). Austenite Formation in the Oxidized Layer of Ultra-High-Strength 13Ni15Co10Mo Maraging Steel. Metals, 12(12), 2115. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12122115