Microstructural Evolution of Wrought-Nickel-Based Superalloy GH4169

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments and Methods

3. Results

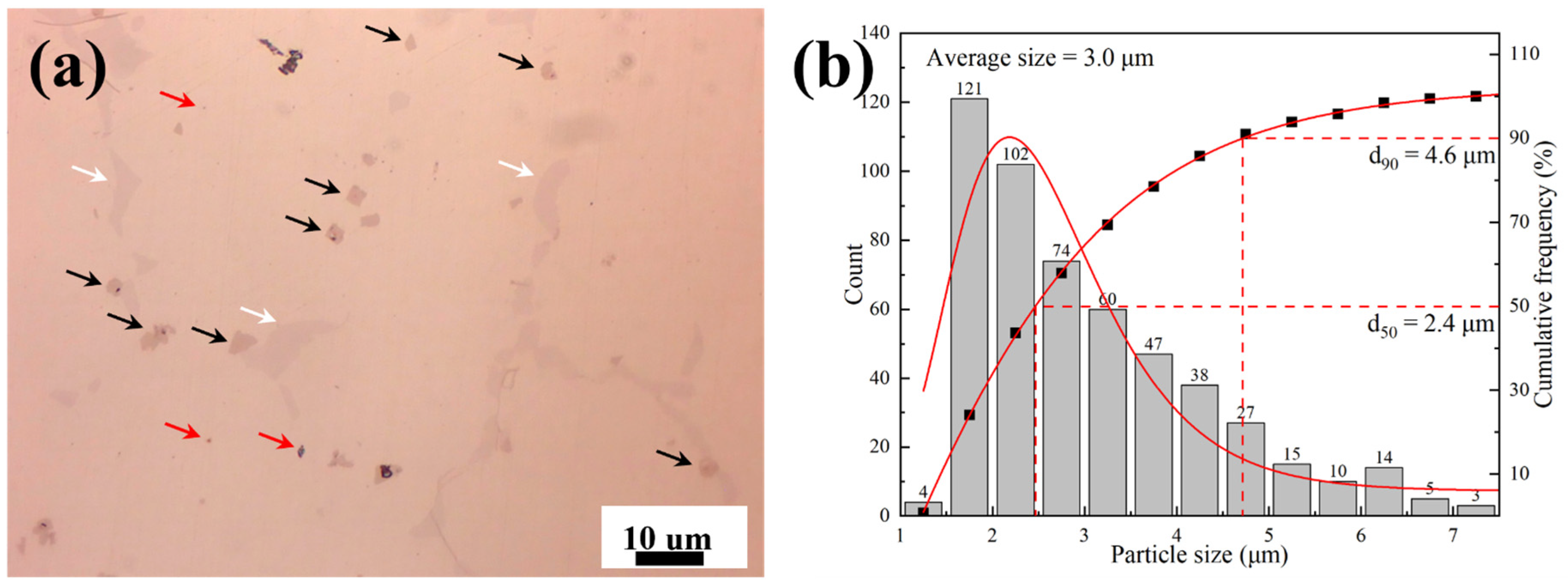

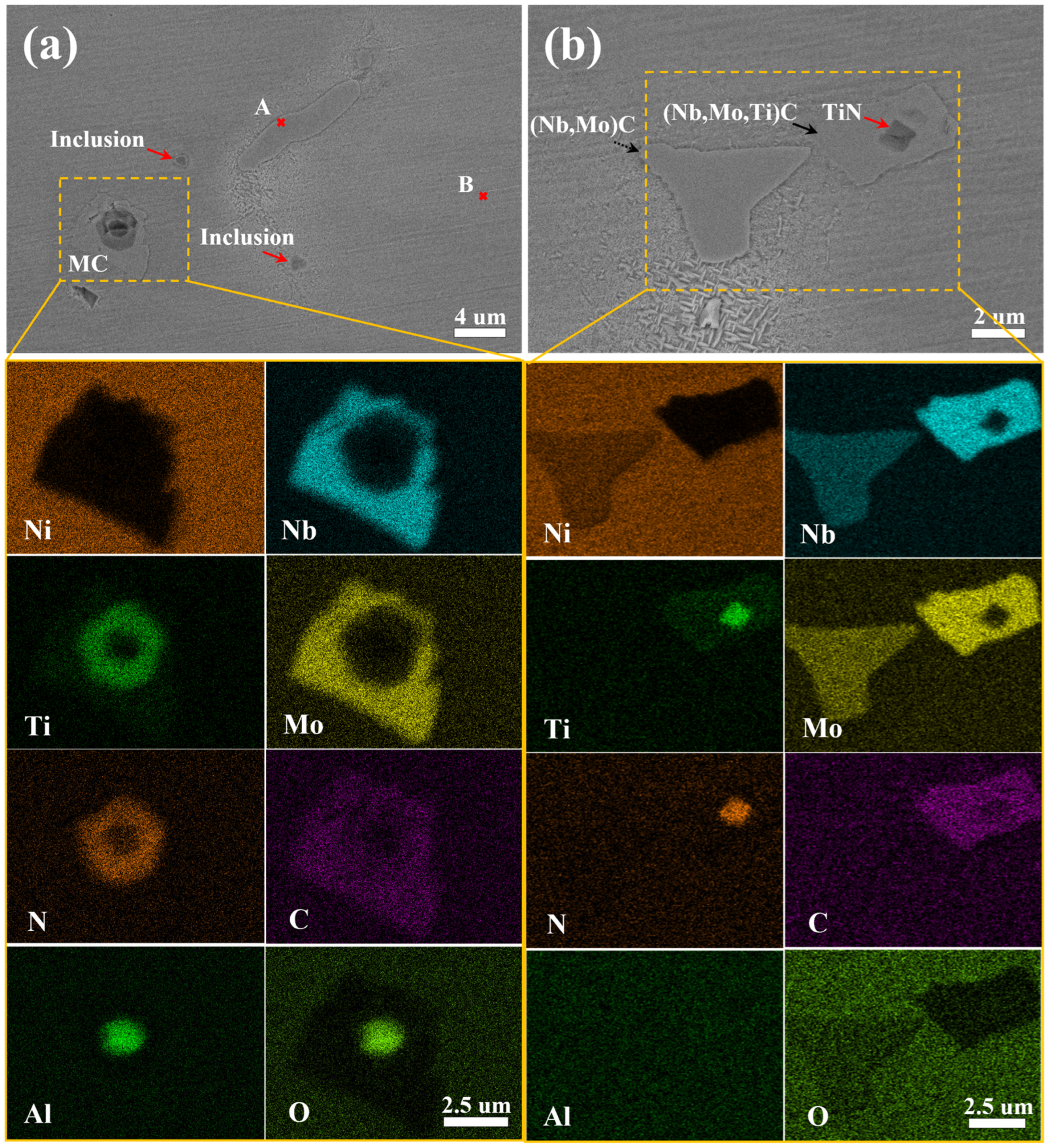

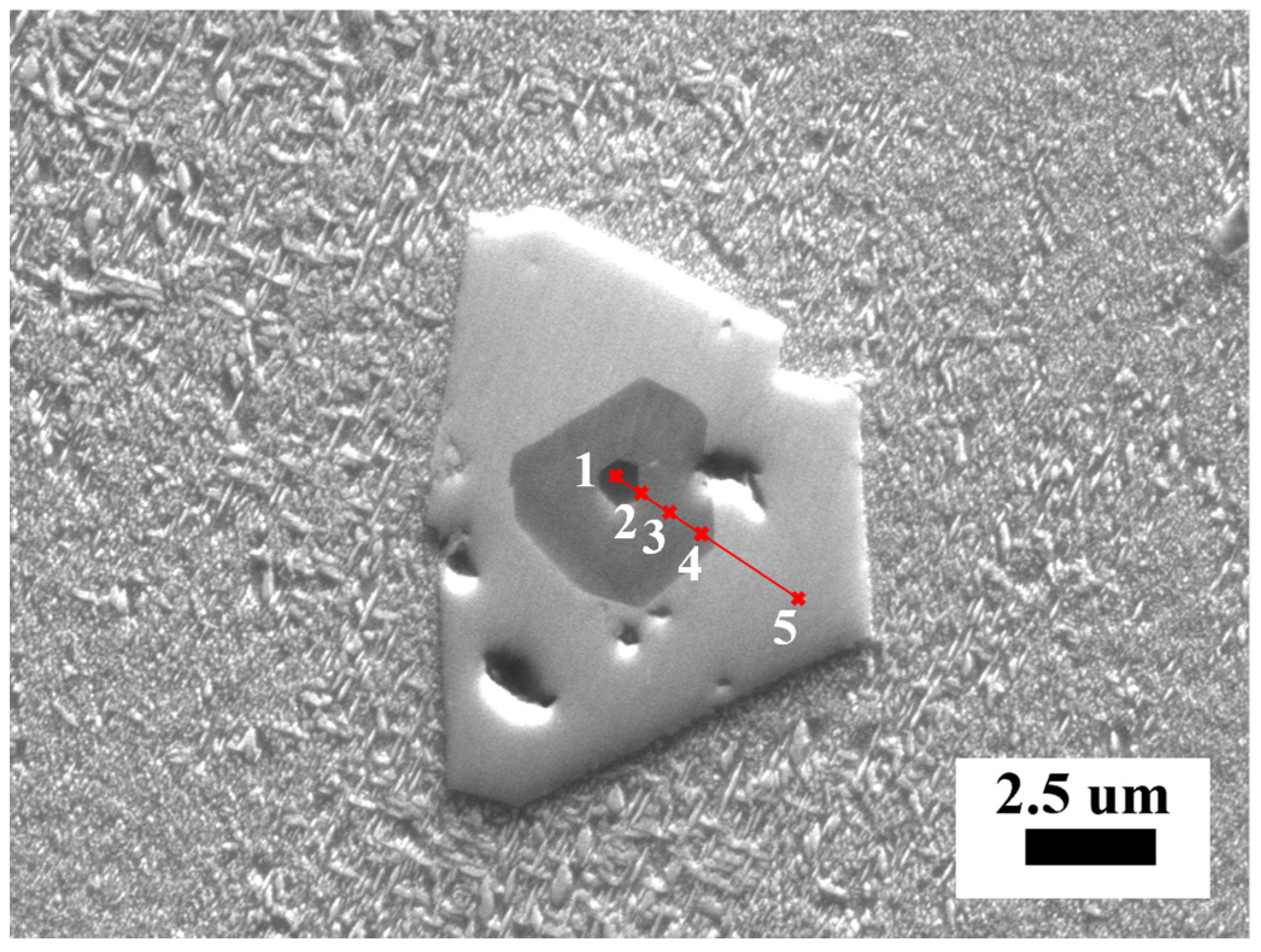

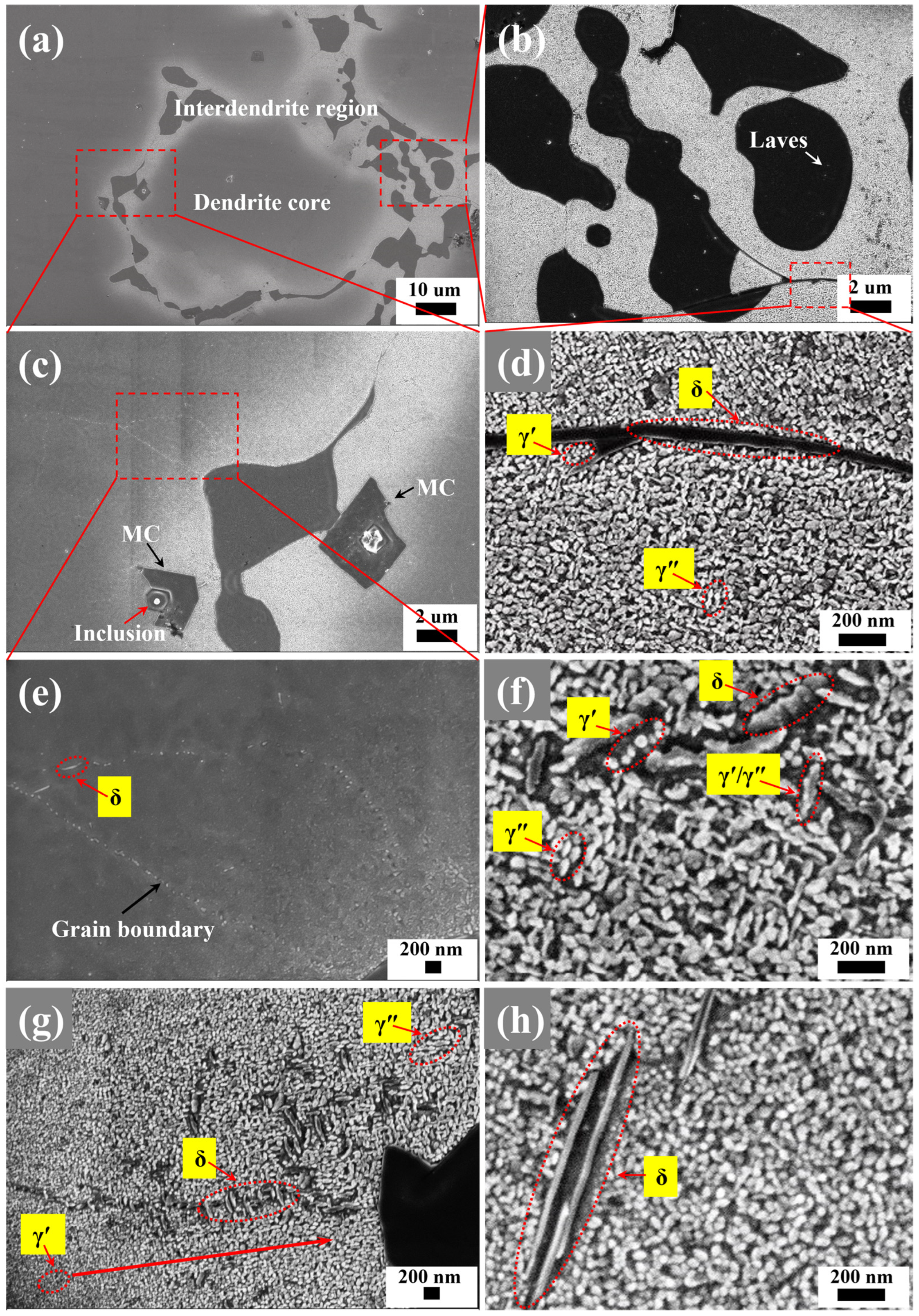

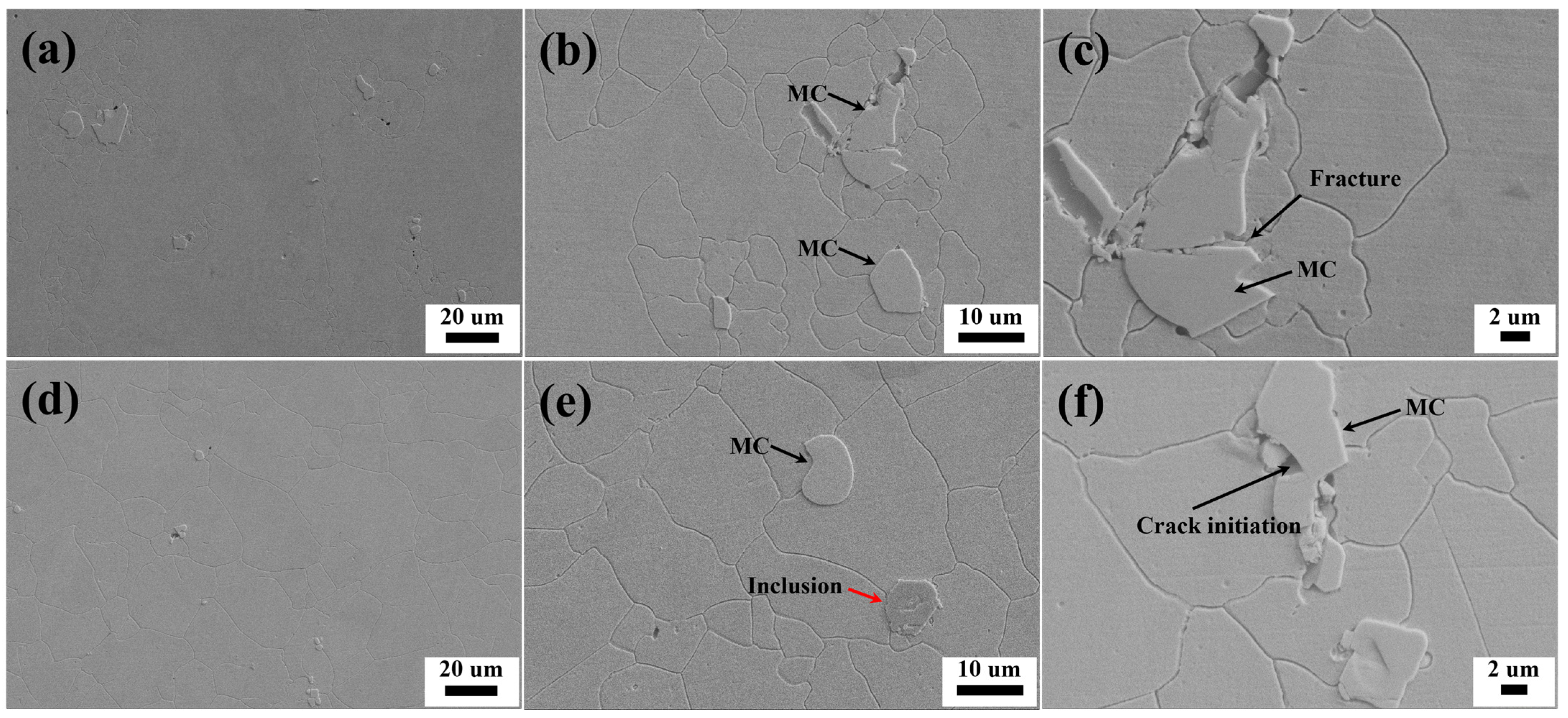

3.1. Cast Microstructure

3.2. DSC Analysis

3.3. Homogenization Microstructure

3.4. Forging Microstructure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilheim, R.; Franz, B.; Heinrich, C. Hardening Cobalt-Nickel-Chromium-Iron Alloys. US2247643A, 1 July 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Boegehold, A.L.; Hanink; Dean, K.; Webbere; Fred, J. Wrought high temperature alloy. US2860968A, 18 November 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser, D.D.; Brown, H.L. Review of the Physical Metallurgy of Alloy 718; Office of Scientific and Technical Information, U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.C. The Superalloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Akca, E.; Gürsel, A. A Review on Superalloys and IN718 Nickel-Based INCONEL Superalloy. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. (PEN) 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Filipponi, M.; Schino, A.D.; Rossi, F.; Castaldi, J.P. Corrosion behaviour of high temperature fuel cells: Issues for materials selection. Metalurgija 2019, 58, 347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Stornelli, G.; Gaggiotti, M.; Mancini, S.; Napoli, G.; Rocchi, C.; Tirasso, C.; Di Schino, A. Recrystallization and Grain Growth of AISI 904L Super-Austenitic Stainless Steel: A Multivariate Regression Approach. Metals 2022, 12, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarbarmas, M.; Aghaie-Khafri, M.; Cabrera, J.M.; Calvo, J. Microstructural evolution and constitutive equations of Inconel 718 alloy under quasi-static and quasi-dynamic conditions. Mater Des. 2016, 94, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Duan, S.; Yang, W.; Guo, H.; Guo, J. Solidification and Segregation Behaviors of Superalloy IN718 at a Slow Cooling Rate. Materials 2018, 11, 2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; El-Wahabi, M.; Cabrera, J.M.; Prado, J.M. High temperature deformation of Inconel 718. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 177, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.W. Forging of superalloys. Mater Des. 2000, 21, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Wu, X.Y.; Chen, X.M.; Chen, J.; Wen, D.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Li, L.T. EBSD study of a hot deformed nickel-based superalloy. J. Alloy. Compd. 2015, 640, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, J.J. Dynamic recrystallization—Scientific curiosity or industrial tool? Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1994, 184, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.K.; Kim, J.H.; Yeom, J.T. Recrystallization and grain growth during alloy 718 processing. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 539–543, 3094–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-C.; Shi, C.-B.; Guo, H.-J.; Wang, F.; Ren, H.; Feng, D. Investigation of Oxide Inclusions and Primary Carbonitrides in Inconel 718 Superalloy Refined through Electroslag Remelting Process. Met. Mater. Trans. B 2012, 43, 1596–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-f.; Yang, S.-l.; Qu, J.-l.; Du, J.-h.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, P.; Wang, N. Inclusions in wrought superalloys: A review. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2021, 28, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, F.; Zhang, W. Precipitation and phase transformation behavior during high-temperature aging of a cobalt modified Fe-24Cr-(22-x)Ni-7Mo-xCo superaustenitic stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 4771–4788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, S.G.K.; Sivakumar, D.; Kamaraj, M. (Eds.) 1-Physical metallurgy of alloy 718. In Welding the Inconel 718 Superalloy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowal, P.R.; Wusatowska-Sarnek, A.M. Carbides and their influence on notched low cycle fatigue behavior of fine-grained IN718 gas turbine disk material. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Derivatives, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2–5 October 2005; pp. 341–349. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, L.S.; Guimarães, A.V.; Siqueira, M.C.; Mendes, M.C.; Mallet, L.; Silva dos Santos, D.; Henrique de Almeida, L. The influence of the processing route on the fragmentation of (Nb,Ti)C stringers and its role on mechanical properties and hydrogen embrittlement of nickel based alloy 718. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16164–16178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.J.; Mirzadeh, H.; Rafiei, M. Solidification behavior and Laves phase dissolution during homogenization heat treatment of Inconel 718 superalloy. Vacuum 2018, 154, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Rui, S.-Y.; Wang, F.; Dong, J.-X.; Yao, Z.-H. Microstructure and homogenization process of as-cast GH4169D alloy for novel turbine disk. Int. J. Min. Met. Mater. 2019, 26, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.J.; Shan, A.D.; Wu, Y.B.; Lu, J.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.L.; Song, H.W. Effects of P and B addition on as-cast microstructure and homogenization parameter of Inconel 718 alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2012, 22, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.A.; Dalai, B.; Åkerström, P.; Arvieu, C.; Jacquin, D.; Lacoste, E.; Lindgren, L.-E. High Strain Rate Deformation Behavior and Recrystallization of Alloy 718. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 5243–5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Voort, G.; Manilova, E. Metallographic Techniques for Superalloys. Microsc Microanal 2004, 10, 690–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radavich, J.F. Electron metallography of alloy 718. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivatives, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2–5 October 2005; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. The precipitation of primary carbides in IN718 and its relation to solidification conditions. In Proceedings of the 6th International Symposium on Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Derivatives, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2–5 October 2005; pp. 299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, A. Primary Carbides in Alloy 718. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Superalloy 718 & Derivatives, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 10–15 October 2010; Volume 1, pp. 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman, M.; Mukhopadhyay, P.; Banerjee, S. Some aspects of the precipitation of metastable intermetallic phases in INCONEL 718. Metall. Trans. A 1992, 23, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenk, C.H.; Feng, L.; McAllister, D.; Wang, Y.; Mills, M.J. Shearing mechanisms of co-precipitates in IN718. Acta Mater. 2021, 220, 117305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, P.J.; McAllister, D.; Gao, Y.; Lv, D.; Williams, R.E.A.; Peterson, B.; Wang, Y.; Mills, M.J. Nano γ′/γ″ composite precipitates in Alloy 718. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 211913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theska, F.; Stanojevic, A.; Oberwinkler, B.; Ringer, S.P.; Primig, S. On conventional versus direct ageing of Alloy 718. Acta Mater. 2018, 156, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Logé, R.E. A review of dynamic recrystallization phenomena in metallic materials. Mater Des. 2016, 111, 548–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.X.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.H.; Liu, C.X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.G. Investigation on the meta-dynamic recrystallization behavior of Inconel 718 superalloy in the presence of delta phase through a modified cellular automaton model. J. Alloy. Compd. 2020, 817, 152773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touazine, H.; Chadha, K.; Jahazi, M.; Bocher, P. Characterization of Subsurface Microstructural Alterations Induced by Hard Turning of Inconel 718. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 7016–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotan, H.; Darling, K.A.; Luckenbaugh, T. High Temperature Mechanical Properties and Microstructures of Thermally Stabilized Fe-Based Alloys Synthesized by Mechanical Alloying Followed by Hot Extrusion. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 1790–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, J.; Rohrer, G.S.; Rollett, A. Chapter 13—Hot Deformation and Dynamic Restoration. In Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena, 3rd ed.; Humphreys, J., Rohrer, G.S., Rollett, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 469–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Shao, W.Z.; Zhen, L.; Lin, L.; Cui, Y.X. Investigation on dynamic recrystallization behavior in hot deformed superalloy Inconel 718. In Proceedings of the Beijing International Materials Week, Beijing, China, 25–30 June 2006; pp. 1297–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Schuh, C.A.; Lu, K. Stability of nanocrystalline metals: The role of grain-boundary chemistry and structure. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | C | Al | Co | Ti | Mo | Nb | Cr | Fe | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R/2 | 0.037 | 0.541 | 0.850 | 0.966 | 2.978 | 5.561 | 17.989 | 18.077 | Balance |

| Etchant No. | Etchant Name and Composition | Etching Method | Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [24] | Saturated oxalic acid solution: 15 g oxalic acid + 100 mL H2O | Electrolytic Etching | Constant current: 50 mA, 10~15 s |

| 2 [21,25] | Kalling′s II Reagent: 1 g CuCl2 + 20 mlHCl + 20 mL C2H5OH | Immerse or swab | As-cast: 5~15 s Homogenization: 30~40 s |

| 3 [26] | 20%H2SO4 + 80%CH3OH | Electrolytic polishing | Constant current: 2A, 4~6 s |

| 4 [9,22,26] | 15 g CrO3 + 10 mL H2SO4 + 150 mL H3PO4 | Electrolytic Etching | Constant current: 50 Ma, 6~10 s |

| 5 [22] | 1 g KMnO4 + 5 ml H2SO4 + 60 mL H2O + 0.2 ml HCl | Boiled and immerse | 1~7 min |

| 6 | Saturated oxalic acid solution: 15 g oxalic acid + 100 mL H2O | Boiled and immerse | 1~2 min, cleaning the surface oxide |

| Point | Ni | Cr | Fe | Al | Ti | Mo | Nb | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 52.90 | 19.78 | 18.95 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 3.12 | 3.67 | γ-matrix |

| B | 40.10 | 11.50 | 10.20 | 0.55 | 1.17 | 7.54 | 28.95 | Laves |

| No. | Ni | Cr | Fe | Al | O | Ti | N | Mo | Nb | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.221 | 0.109 | 0.076 | 9.669 | 73.867 | 8.871 | 5.231 | 0 | 0.56 | 1.396 |

| 2 | 0.471 | 0.349 | 0.19 | 1.181 | 22.351 | 30.03 | 40.678 | 0 | 2.382 | 2.368 |

| 3 | 0.432 | 0.296 | 0.167 | 1.509 | 37.14 | 24.77 | 30.847 | 0 | 1.625 | 3.214 |

| 4 | 1.602 | 0.782 | 0.46 | 0.042 | 7.58 | 32.003 | 48.872 | 0 | 2.928 | 5.731 |

| 5 | 8.87 | 2.92 | 2.908 | 0.184 | 6.984 | 6.272 | 0 | 0 | 29.326 | 42.537 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, J.; Wang, Z.; Zuo, L. Microstructural Evolution of Wrought-Nickel-Based Superalloy GH4169. Metals 2022, 12, 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12111936

Zhou W, Chen X, Wang Y, Chen K, Zhu Y, Qin J, Wang Z, Zuo L. Microstructural Evolution of Wrought-Nickel-Based Superalloy GH4169. Metals. 2022; 12(11):1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12111936

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Wei, Xiaohua Chen, Yanlin Wang, Kaixuan Chen, Yuzhi Zhu, Junwei Qin, Zidong Wang, and Lingli Zuo. 2022. "Microstructural Evolution of Wrought-Nickel-Based Superalloy GH4169" Metals 12, no. 11: 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12111936

APA StyleZhou, W., Chen, X., Wang, Y., Chen, K., Zhu, Y., Qin, J., Wang, Z., & Zuo, L. (2022). Microstructural Evolution of Wrought-Nickel-Based Superalloy GH4169. Metals, 12(11), 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12111936