Modeling of Abnormal Grain Growth That Considers Anisotropic Grain Boundary Energies by Cellular Automaton Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

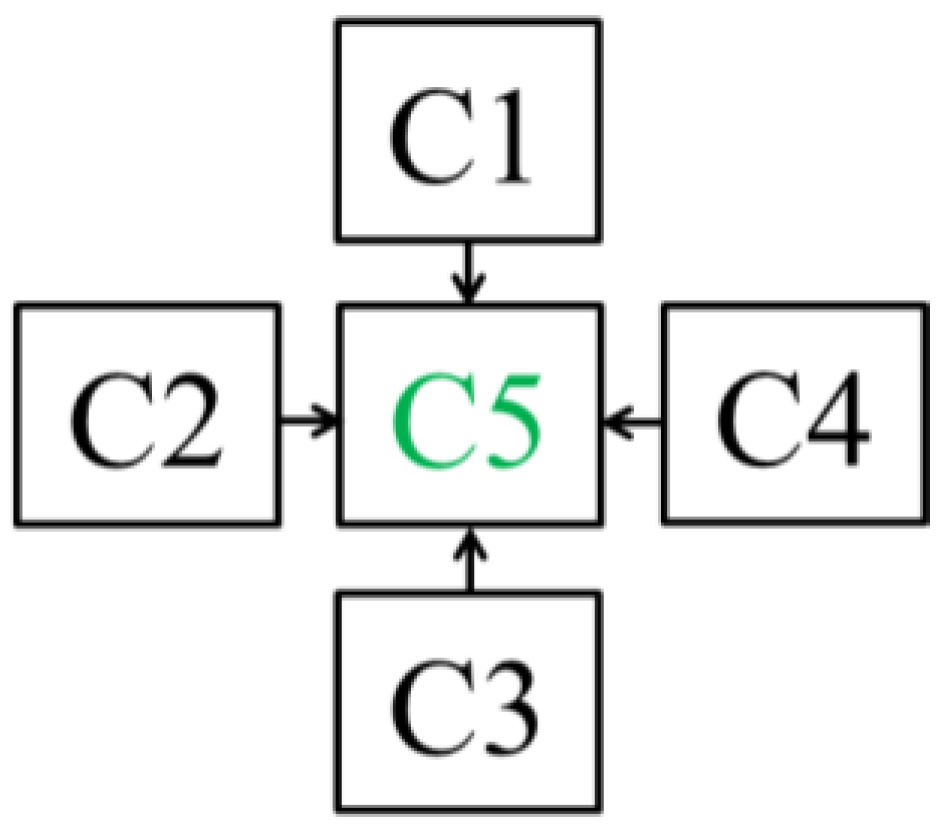

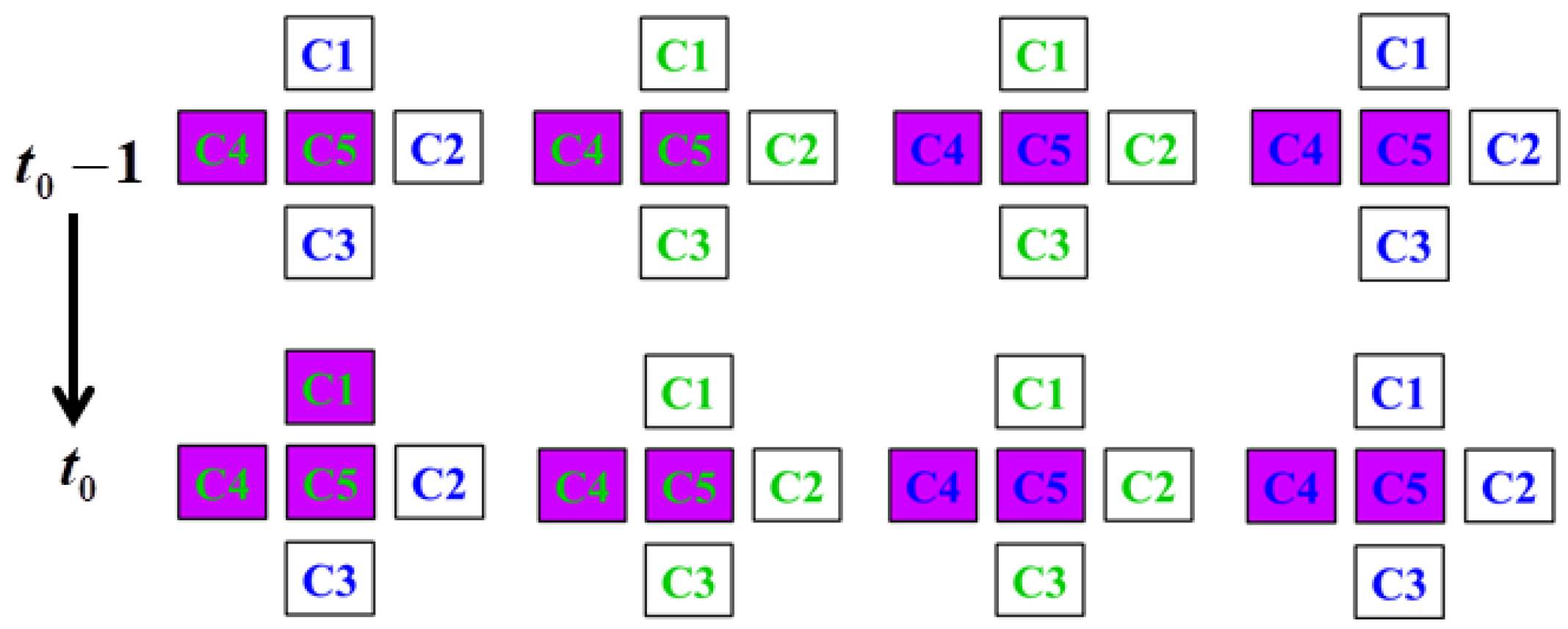

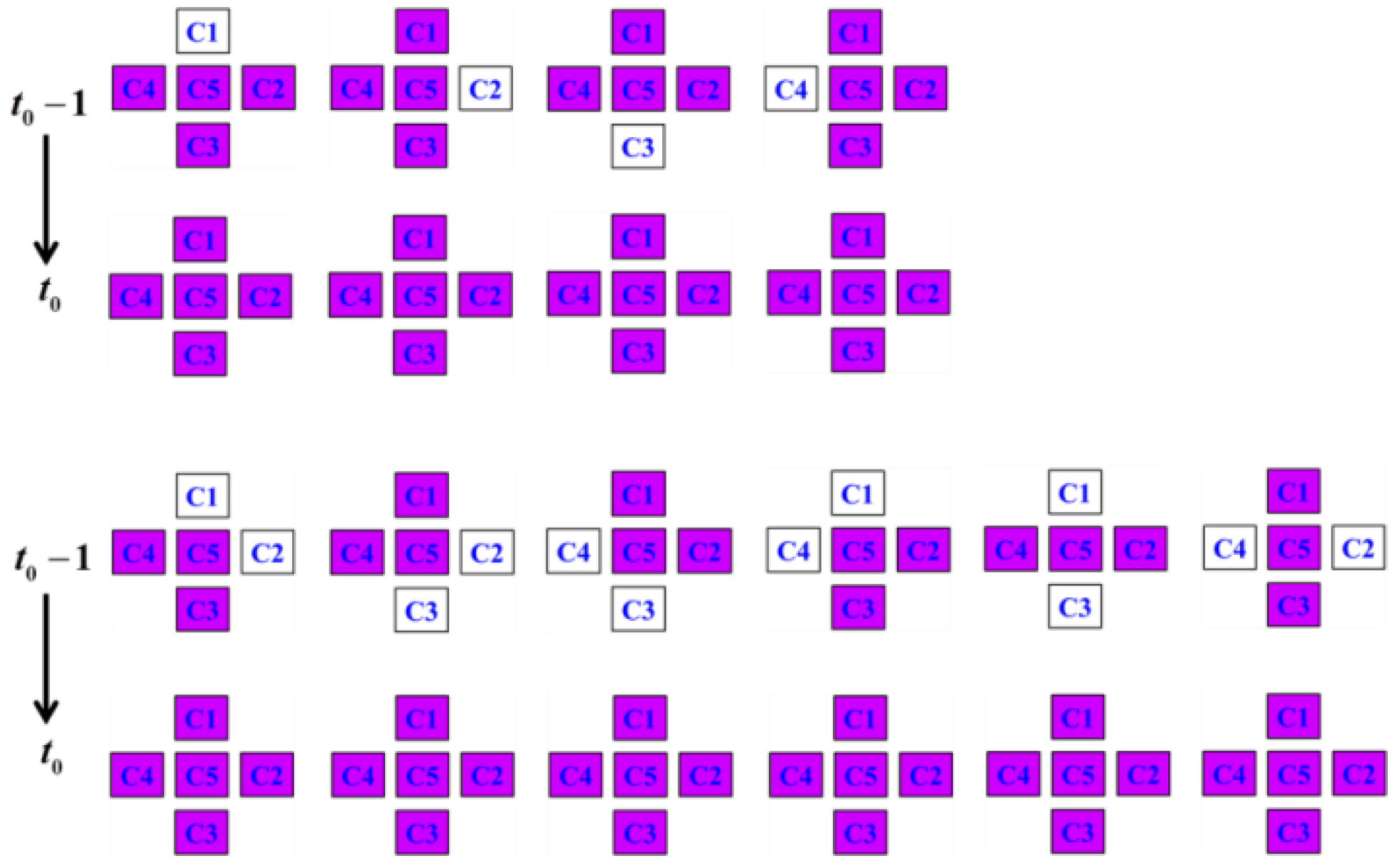

2. CA Model for AGG

3. Results and Discussion

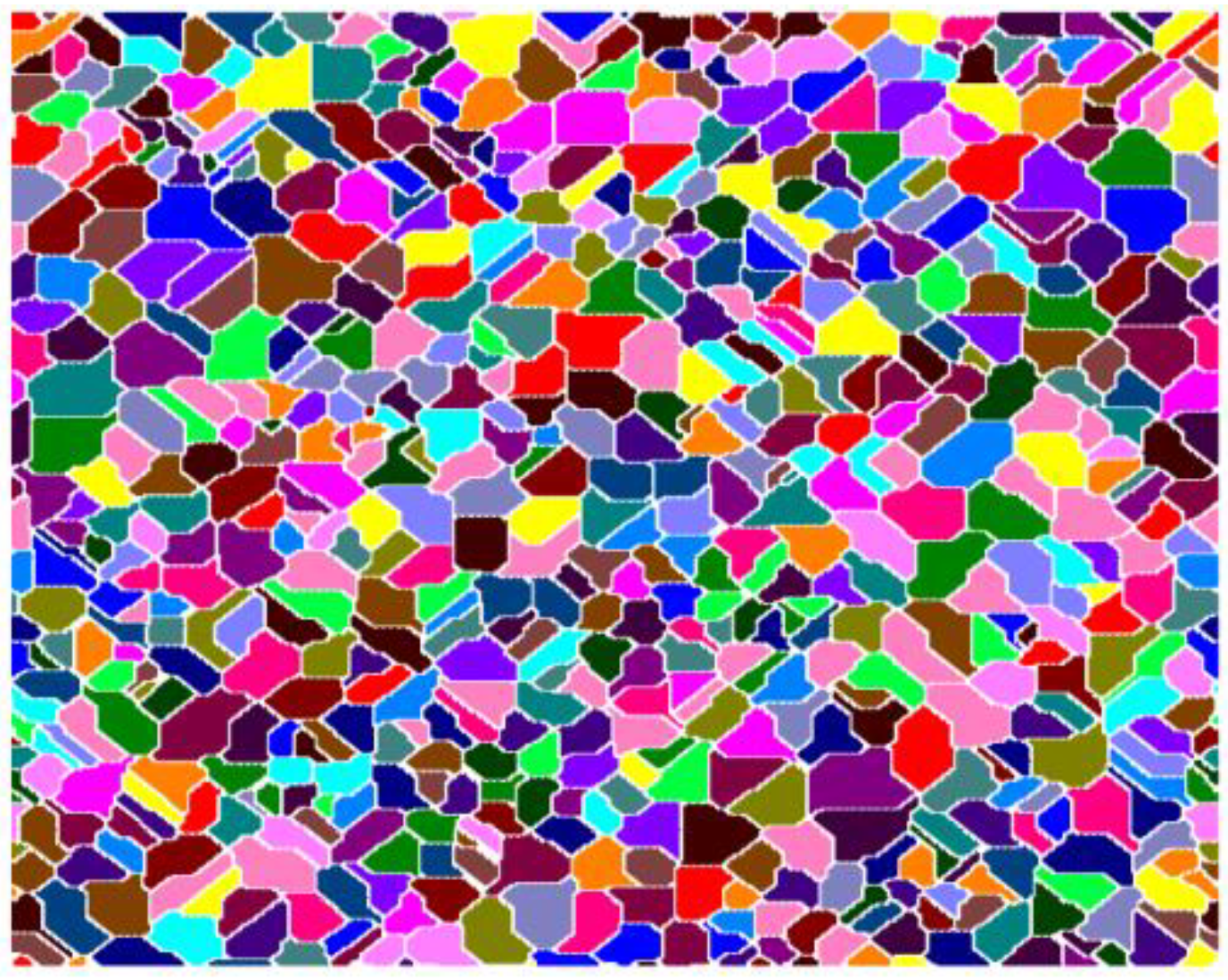

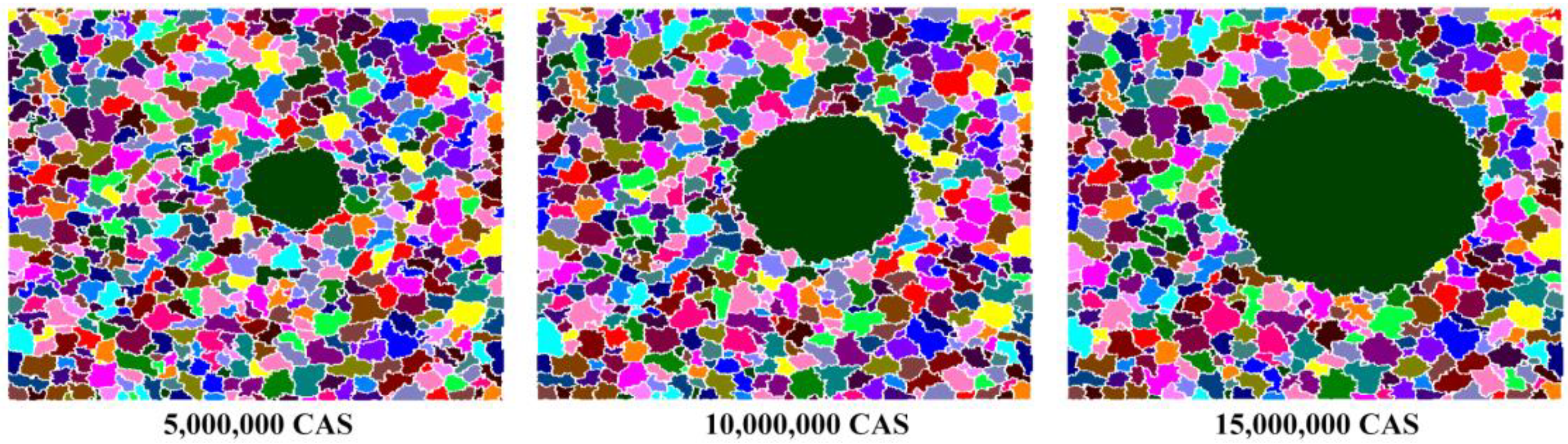

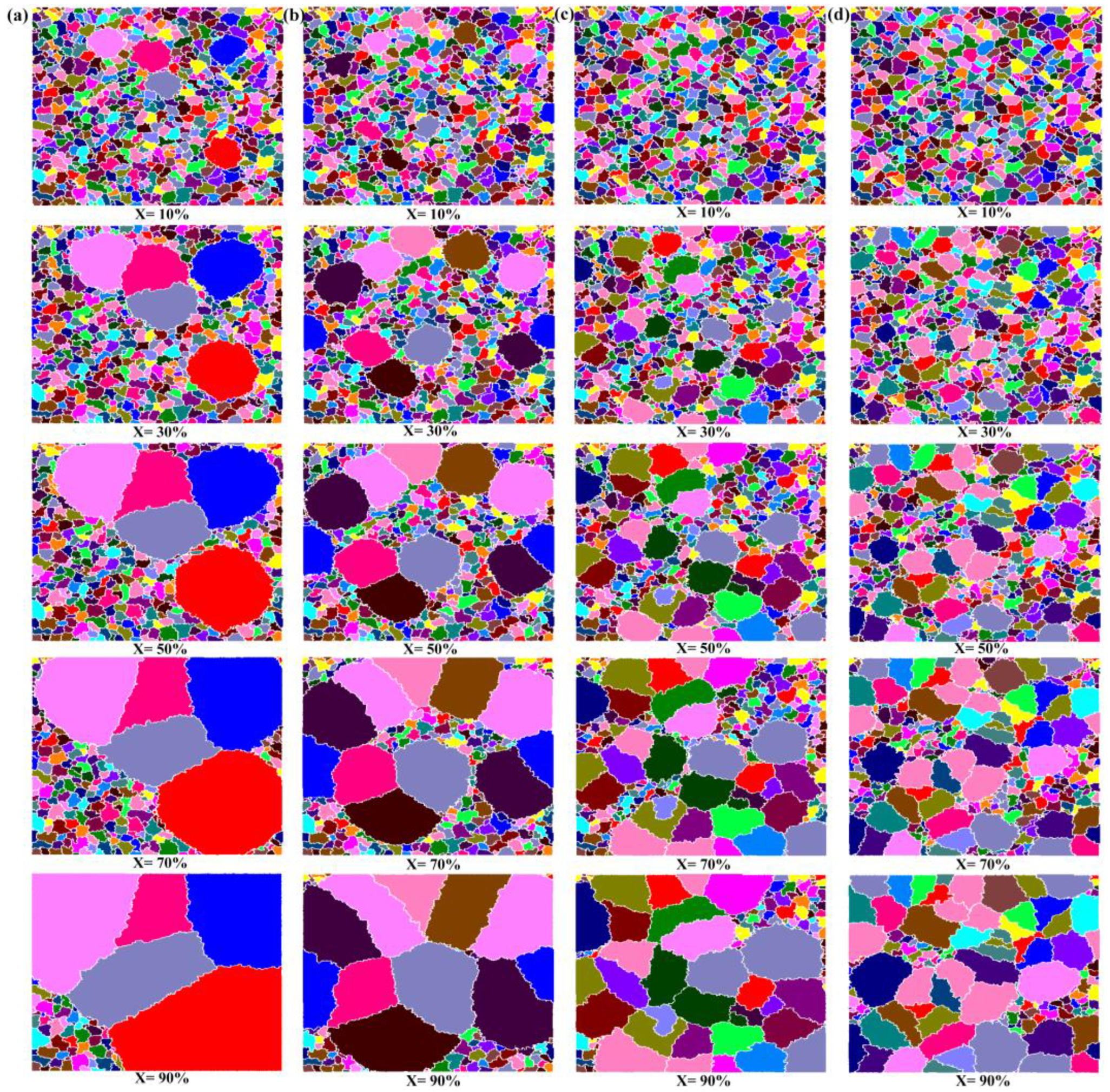

3.1. Morphology

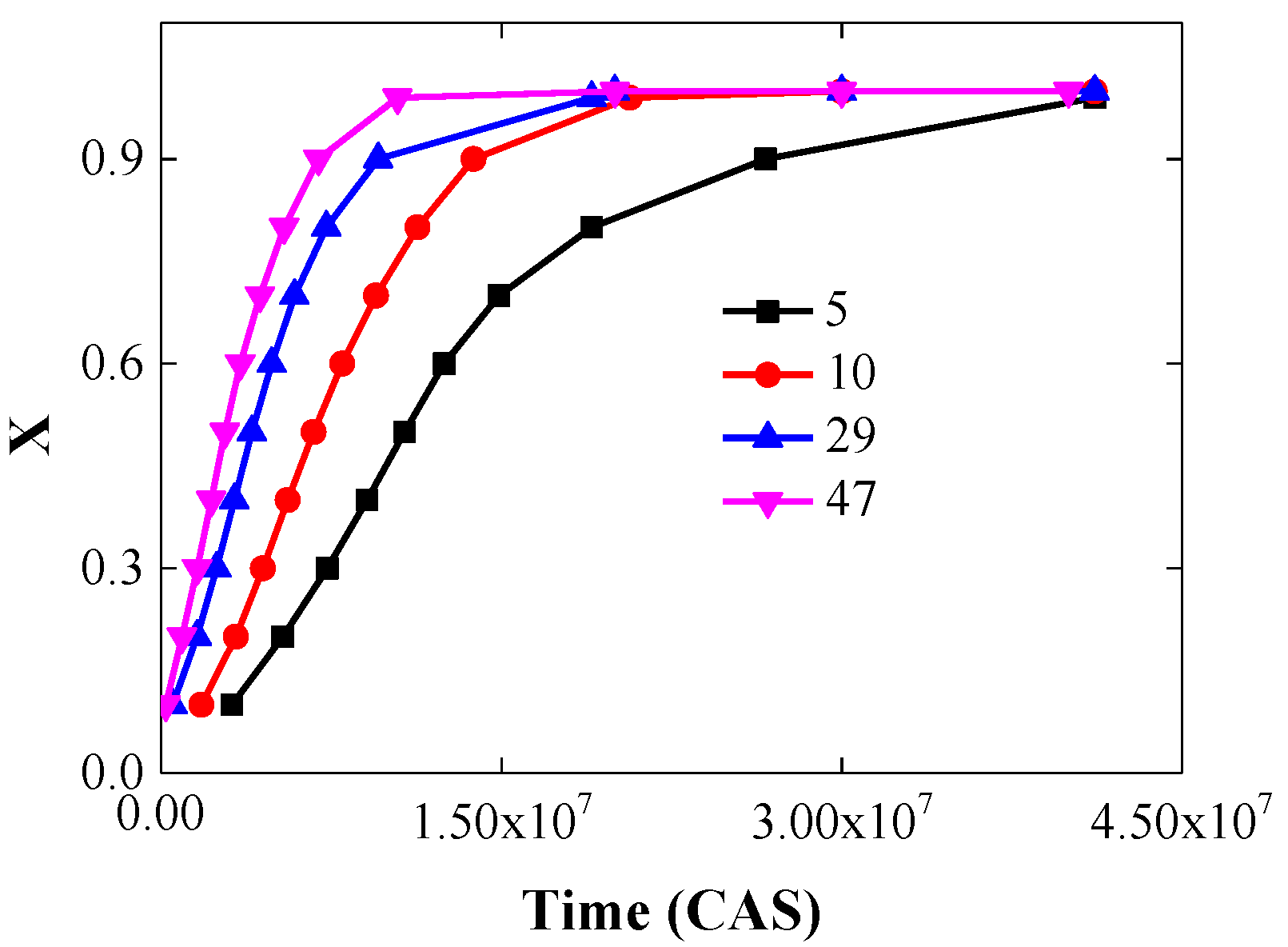

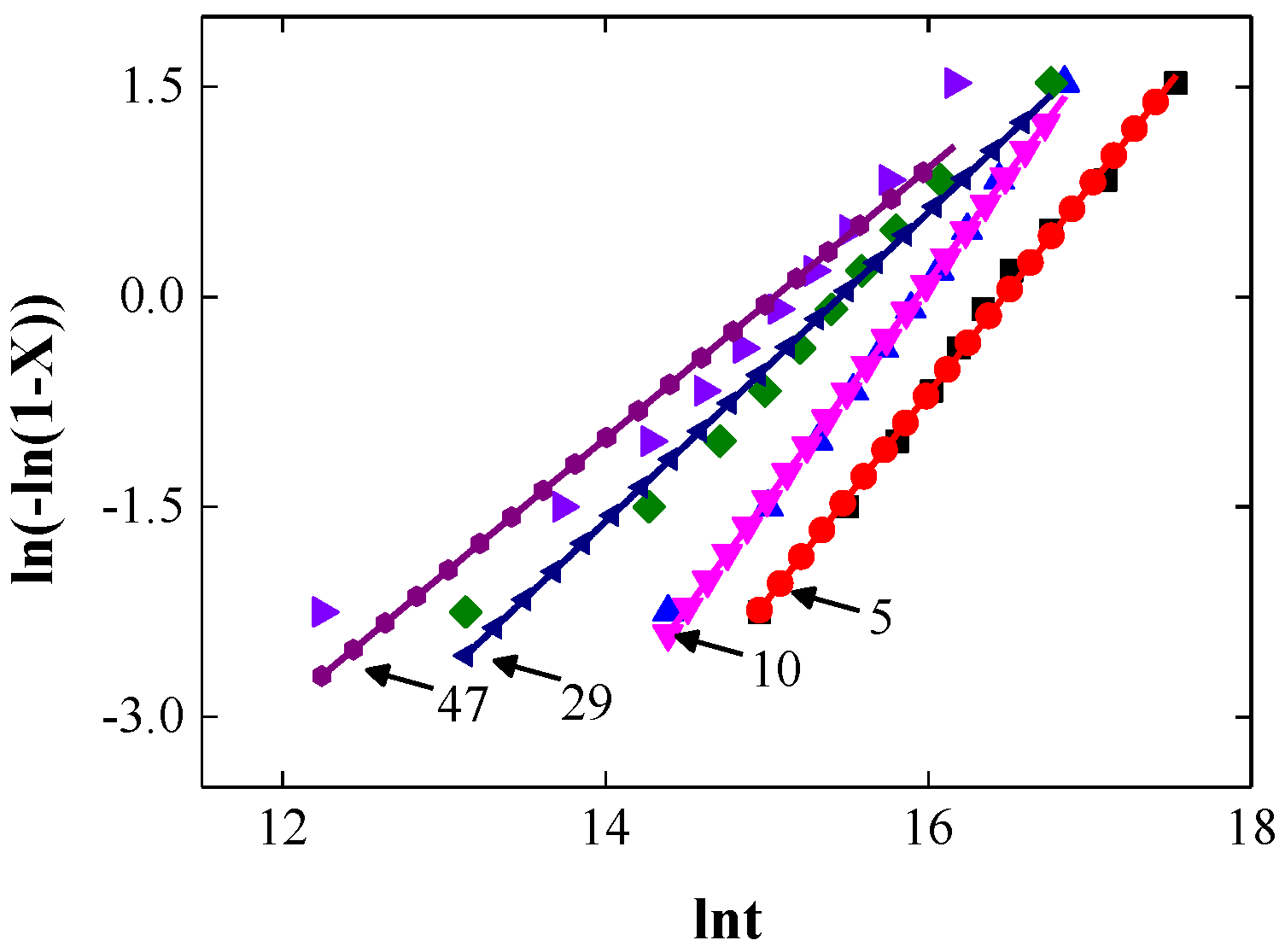

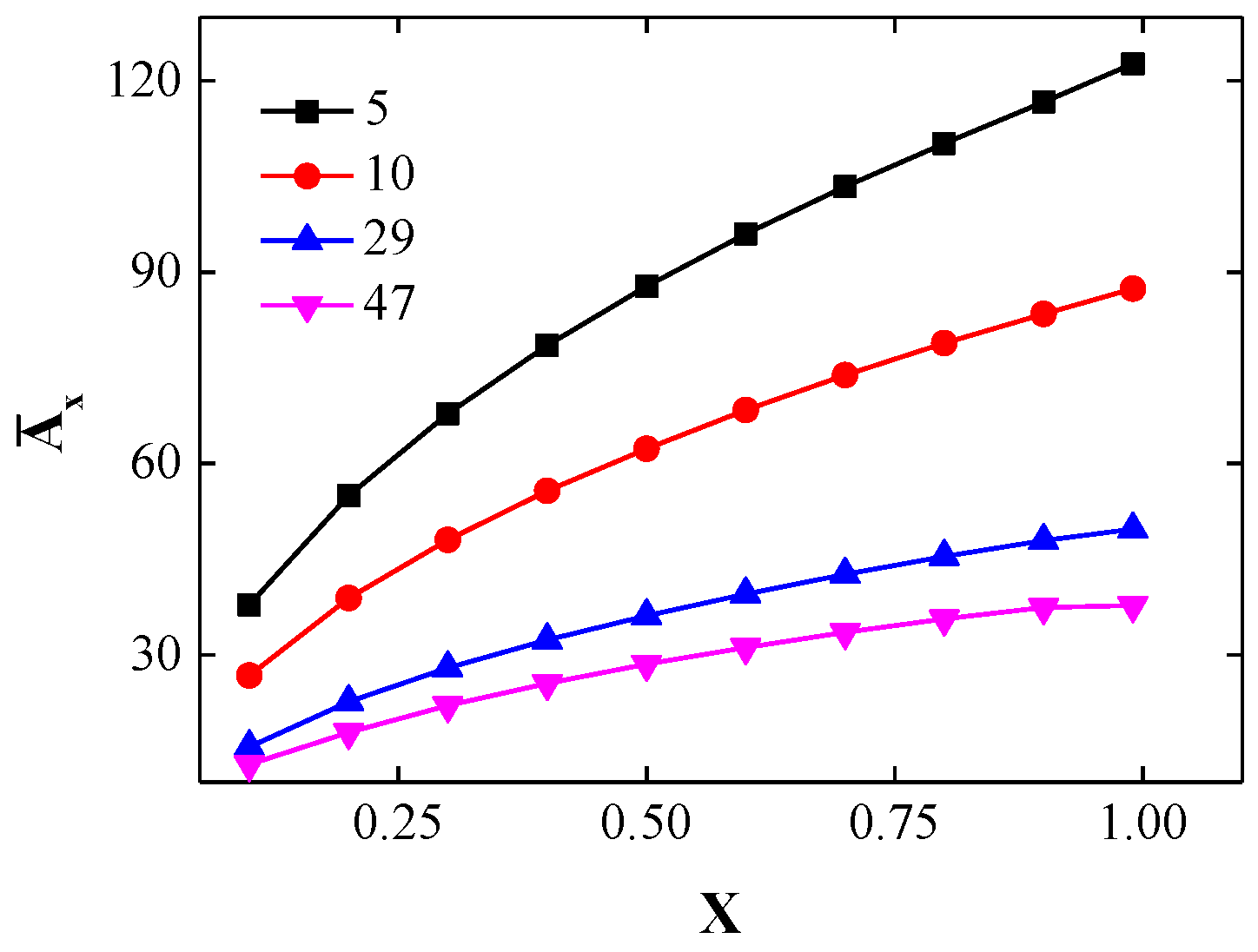

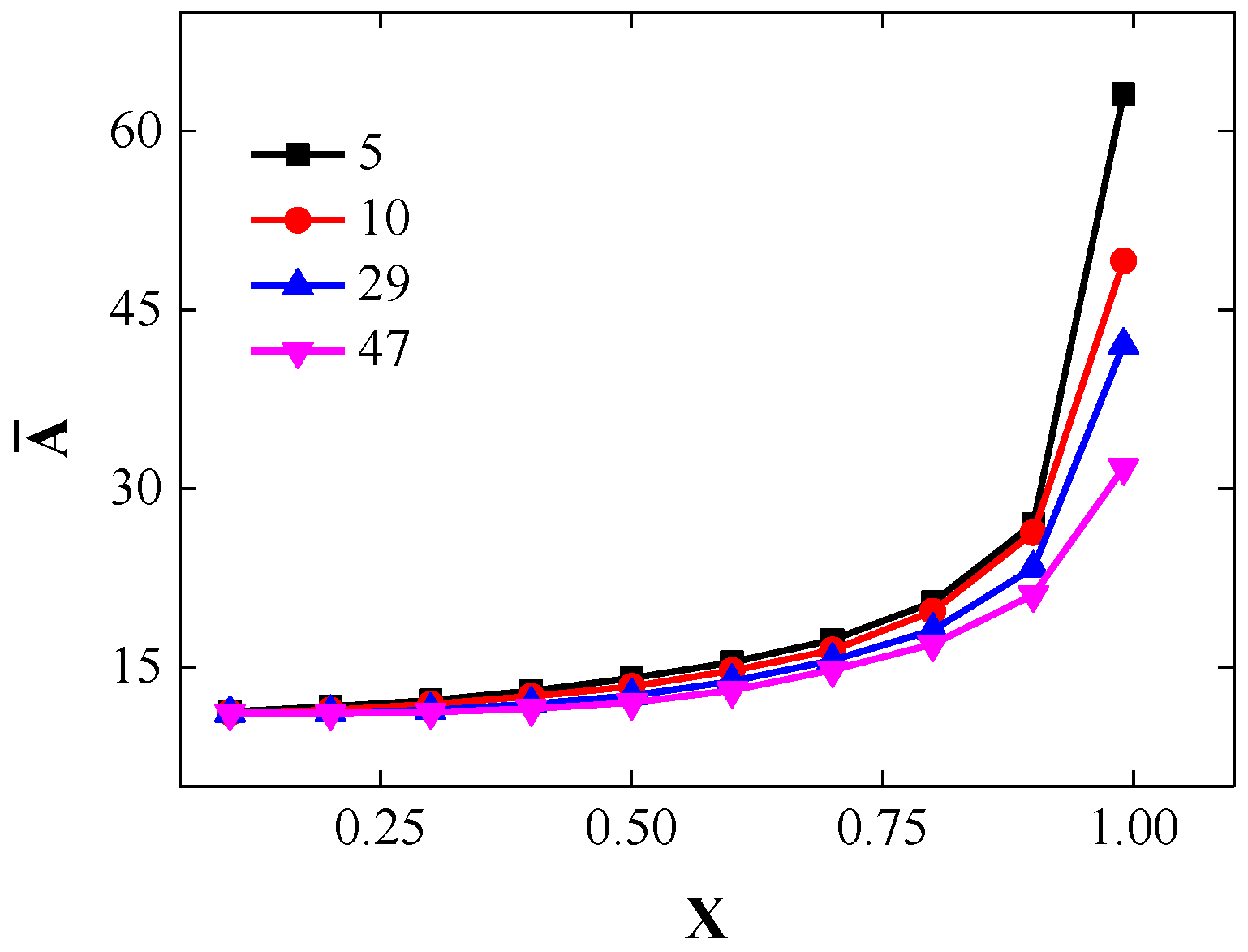

3.2. Growth Kinetics

3.3. Local Kinetics

3.4. Grain Size Distribution

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The anisotropic grain boundary energy is described based on two types of grains (Type I and Type II), which form four kinds of grain boundaries (Type I-Type I, Type I-Type II, Type II-Type I and Type II-Type II boundaries). By using a curvature-driven mechanism for the grain boundaries formed by the same kind of grains and the lowest energy principle for the grain boundaries formed by different kinds of grains, the state transition rules of AGG that considers anisotropic grain boundary energies was established.

- (2)

- In the CA model, different grains in the system are endued with different and unique orientations and thus grain coalescence is completely avoided. The morphology shows that a few grains consume adjacent small grains to achieve AGG by way of secondary recrystallization.

- (3)

- The JMA model and Hillert model are used to describe the growth kinetics of grain growth. The Avrami exponent p decreases from 1.5 to 1 with the increase in the initial Type II grains. The analysis based on growth kinetics and grain size distribution is also consistent with the microstructure evolution of AGG, which also substantiates the accuracy of the CA model for AGG.

- (4)

- Even though the CA model provided in this paper applies Rollett’s model to describe anisotropic grain boundary energy, the previously reported phenomenon of AGG caused by the wetting of the matrix and grain coalescence never occurs. This is mainly due to the difference between the CA model used in this paper and the MC model provided by Rollett in the expression of the grain growth mechanism. In other words, the CA model can consider the curvature-driven mechanism and avoid grain coalescence while the MC model cannot. Therefore, the research results of this paper are also an important supplement to the previous research results regarding AGG.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Su, F.Y.; Liu, W.L.; Wen, Z. Three-dimensional cellular automaton simulation of austenite grain growth of Fe-1C-1.5Cr alloy steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hillert, M. On the theory of normal and abnormal grain growth. Acta Metall. 1965, 13, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Militzer, M.; Perez, M. Phase field modelling of abnormal grain growth. Materials 2019, 12, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.X.; Ke, Z.J.; Li, R.H.; Song, J.Q.; Ruan, J.J. Study of Grain Growth in a Ni-Based Superalloy by Experiments and Cellular Automaton Model. Materials 2021, 14, 6922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Fang, G.; Qian, L.Y. Modeling of dynamic recrystallization of Magnesium alloy using cellular automata considering initial topology of grains. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 711, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhu, H.J.; Zhang, H.M.; Cui, Z.S. Mesoscale Modeling of Dynamic Recrystallization: Multilevel Cellular Automaton Simulation Framework. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 1286–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, H.M.; Cui, Z.S. Review on modeling and simulation of microstructure evolution during dynamic recrystallization using cellular automaton method. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2020, 63, 357–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, H.Q.; Zhang, J.; Yang, M.J.; Du, Y.; Zhao, D.D. Progress in interfacial thermodynamics and grain boundary complexion diagram. Acta Met. Sin Eng. 2021, 57, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Fu, R.D.; Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, H.J. Abnormal grain growth in the heat affected zone of friction stir welded joint of 32Mn-7Cr-1Mo-0.3N steel during post-weld heat treatment. Metals 2018, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, H.; Bulatov, V.V. Modeling of grain growth under fully anisotropic grain boundary energy. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 27, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.F.; Wang, X.H.; Zhang, J.Z.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.J.; Shen, Z.J. A general mechanism of grain growth-I. Theory. J. Mater. 2021, 7, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.; Kundin, J.; Shchyglo, O.; Mohles, V.; Marquardt, K.; Steinbach, I. Role of inclination dependence of grain boundary energy on the microstructure evolution during grain growth. Acta Mater. 2020, 188, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, J.M.; Krill, C.E. Abnormal grain growth in nanocrystalline materials. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2013, 753, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotan, H.; Darling, K.A.; Saber, M. An in situ experimental study of grain growth in a nanocrystalline Fe91Ni8Zr1 alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 2251–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnweber-Ribic, P.; Gruber, A.P.; Dehm, G.; Strunk, H.P.; Arzt, E. Kinetics and driving forces of abnormal grain growth in thin Cu films. Acta Mater. 2012, 60, 2397–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, W.; Kawalko, J.; Rutkowski, B.; Watroba, M.; Gao, N.; Starink, M.J.; Bala, P.; Langdon, T.G. Abnormal grain growth in a Zn-0.8Ag alloy after processing by high-pressure torsion. Acta Mater. 2021, 207, 116667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, M.; Polat, G.; Kotan, H. An investigation of abnormal grain growth in Zr doped CoCrFeNi HEAs through in-situ formed oxide phases. Intermetallics 2022, 146, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadollahpour, M.; Hosseini-Toudeshky, H. Materials properties and failure prediction of ultrafine grained materials with bimodal grain size distribution. Eng. Comput. 2017, 33, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grest, G.S.; Srolovitz, D.J.; Anderson, M.P. Computer simulation of grain growth-IV. anisotropic grain boundary energies. Acta Metall. 1985, 33, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srolovitz, D.J.; Grest, G.S.; Anderson, M.P. Computer simulation of grain growth-V. abnormal grain growth. Acta Metall. 1985, 33, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollett, A.D.; Srolovitz, D.J.; Anderson, M.P. Simulation and theory of abnormal grain growth-anisotropic grain boundary energies and mobilities. Acta Metall. 1989, 37, 1227–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Esche, S.K. Modeling of grain growth kinetics with Read-Shockley grain boundary energy by a modified Monte Carlo algorithm. Mater. Lett. 2002, 56, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Esche, S.K. A new perspective on the normal grain growth exponent obtained in two-dimensional Monte Carlo simulations. Modelling Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003, 11, 859–861. [Google Scholar]

- Miodownik, M.A. A review of microstructural computer models used to simulate grain growth and recrystallisation in aluminium alloys. J. Light Met. 2002, 2, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.Y.; Yu, D.H.; Wu, X.T. Simulation of grain growth behavior of hot-extruded pure magnesium by cellular automata. J. Plast. Eng. 2016, 23, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kroc, J.; Paidar, V. Modelling of the effect of triple junctions on grain boundary migration by a cellular automaton. J. Phys. IV 2001, 11, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.Y.; Huang, C.Y.; Kafka, O.L.; Lian, Y.P.; Yan, W.T.; Chen, M.J.; Fang, D.N. Grain growth prediction in selective electron beam melting of Ti-6Al-4V with a cellular automaton method. Mater. Des. 2020, 199, 109410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.Z.; Ding, H.L.; Liu, L.F.; Shin, K.S. Computer simulation of 2D grain growth using a cellular automata model based on the lowest energy principle. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2006, 429, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, K. An introductory review of cellular automata modeling of moving grain boundaries in polycrystalline materials. Math. Comput. Simul. 2010, 7, 1361–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, M.H.; Wang, X.F. Cellular automata simulation for grain growth based on anisotropic grain boundary mobility and grain boundary energy. Mater. Mech. Eng. 2012, 36, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, H.; Rai, A.K.; Hajra, R.N.; Raju, S.; Saibaba, S. Modelling the role of nucleation on recrystallization kinetics: A cellular automata approach. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1731, 030009. [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto, M.; Kamiya, M.; Nagai, T. Computer simulation of two-dimensional grain growth with anisotropic grain boundary energy and mobility by vertex model. Mater. Sci. Forum. 1996, 204, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, L.; Mei, B.; Yu, L. Modeling of Abnormal Grain Growth That Considers Anisotropic Grain Boundary Energies by Cellular Automaton Model. Metals 2022, 12, 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12101717

Ye L, Mei B, Yu L. Modeling of Abnormal Grain Growth That Considers Anisotropic Grain Boundary Energies by Cellular Automaton Model. Metals. 2022; 12(10):1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12101717

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Liyan, Bizhou Mei, and Liming Yu. 2022. "Modeling of Abnormal Grain Growth That Considers Anisotropic Grain Boundary Energies by Cellular Automaton Model" Metals 12, no. 10: 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12101717

APA StyleYe, L., Mei, B., & Yu, L. (2022). Modeling of Abnormal Grain Growth That Considers Anisotropic Grain Boundary Energies by Cellular Automaton Model. Metals, 12(10), 1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12101717