Abstract

Political distrust has been the norm, rather than the exception, in many established democracies in recent decades. Despite a wealth of data tracking deteriorating citizen attitudes towards their governments, representatives and political systems in general, there is still a debate regarding the meaning of distrust and its significance for the health of democracies. This article contributes to the discussion by providing qualitative evidence that map the meaning, evaluative dimensions and spill-over process of distrusting political attitudes. It finds, across the three national contexts studied, that citizens express political distrust using similar language and employing the same evaluative structure. Evidence suggests that political distrust is intertwined with the failure of representation and entails a fundamentally ethical dimension. This article concludes with a discussion regarding the implications of these findings for research on diffuse support in democratic systems.

1. Introduction

Discussions regarding the erosion of political trust are omnipresent in public and academic circles and have given rise to a heated debate around the health of western democratic systems [1,2]. Citizen distrust of government, politicians, political parties and representative institutions has become the norm rather than the exception starting from the 1970s, when the scholarly community was first alerted to the trends of declining political trust across established democracies. Since then, the debate rages on. Is distrust an ominous sign for democratic stability, simply an expression of dissatisfaction towards underperforming incumbents or an inevitable by-product of rising citizen expectations [3,4]? From the rich academic literature that has ensued, we know that political trust represents “a reservoir of good-will” that helps maintain support for overall democratic achievements in times of crises and that widespread political distrust can pose a fundamental challenge for the effective operation of government [5,6]. We also know that citizens who are trustful of their government and political institutions behave in a cooperative manner, complying with policy decisions and, in turn, allowing the political institutions to function efficiently [7,8,9].But to this day, we know little about how citizens themselves evaluate the untrustworthiness of democratic systems—how they describe and explain their attitudes of distrust, and how political distrust persists and spreads across parts of a democratic regime.

This article examines political distrust from the citizens’ perspective in three European democracies. It employs a micro-level and qualitative methodological approach as it seeks to understand what political distrust means for citizens, by exploring the language they use when expressing distrust, the rationale they attach to their judgements and the narratives they develop to explain how perceptions of untrustworthiness are formed. The aim is to investigate how citizens’ negative orientations towards political agents, institutions and processes can be meaningfully systematised using their narratives and what insights these provide to fill some of the gaps left by quantitative studies. Empirical research on political trust has explored the individual determinants (micro-level) of trusting attitudes and the consequences in terms of political behaviour and participation [7,10]. Research has also focused on the contextual determinants (macro-level) shaping trust at the country level [11]. The vast majority of modern scholarship has relied on surveys and on the use of cross-sectional or panel data of trust levels. Since the seminal work of Almond and Verba [12], very little research has incorporated qualitative evidence regarding citizens’ evaluation and attitudes towards regime principles, institutions and actors [13,14]. As a result, we have many informative theories regarding the institutional, cultural and psychological causes of political trust, but also a number of blind spots regarding the meaning, rationale and spread of distrusting political attitudes.

As a result, while there is widespread agreement that citizen attitudes towards their governments and political institutions are negative [3,15], we do not really know what this means for people and whether it means the same for different groups and different national contexts [16,17]. Similarly, scholarship has conceptualised political trust as relational and targeted at a specific set of political objects, either at core institutions of representative democracy or at political actors, incumbents and office holders [2,18]. And while distrusting attitudes towards different political targets may hold a different weight [11], we do not know whether political targets are evaluated as untrustworthy following similar judgments. We are thus unable to explore how distrust can be contained at the specific level or spill-over to the diffuse level and become systemic. In consequence, this limits our ability to tailor policy actions to reversing distrusting trends before they compromise the effectiveness of government operations.

Using a citizen-centred approach and qualitative empirical evidence, this article explores the meaning and evaluative components of political distrust in three European democracies. It provides crucial insights into attitudes of political distrust that can supplement existing micro- and macro-level studies, which aim to explain the causes and correlates of distrust in political actors and institutions. This article finds that while there are some differences across the three national contexts under study and according to individual demographics, overall political trust and distrust are human experiences found in any politically organised society. Citizens appear to make sense of untrustworthiness in the political world around them in much the same way and to refer to similar cognitive and affective response patterns in the countries under study. It is therefore possible to systematise a common understanding of political distrust that is expressed in terms of negative expectations, lack of representation and feelings of betrayal. Attitudes of political distrust entail evaluations that follow technical, ethical and interest-based considerations, and furthermore, they set in motion a particular emotive and behavioural set of actions. These findings put in perspective the over-emphasis on economic or institutional performance indicators and point to the importance of normative considerations regarding the institutional function and behaviour of political actors. Overall, findings can aid in the interpretation of survey results showing the persistence of distrust despite economic stability, the appeal of populist rhetoric and phenomena of distrust spilling-over from the specific to the systemic political level.

2. Dealing with Political Distrust

The Great Recession of 2008 and its aftermath, the rise of populism across democratic regimes, the popular backlash to the European project and supranational cooperation, as well as the appeal of anti-establishment parties and candidates across established democracies are all pointing to a ‘crisis of representation’ where political distrust is rampant. Many democracies have witnessed growing challenges to their political processes, with citizens becoming increasingly weary and distrustful of their politicians, turning their backs to established political parties and candidates or even taking to the streets to actively protest against policies and political institutions. Given the current political climate and the uninterrupted trend of deteriorating signs of system support, there is strong reason to believe that attitudes of distrust merit closer analysis [4,19]. The theoretical importance of political trust for the effective governance and legitimacy of democratic regimes has been highlighted by numerous scholars [3,5,20,21] and empirical studies have shown political trust is a key component of diffuse support for democratic systems [10,22,23].

Given its significance, political scientists have been using mass surveys and frequent polling to closely monitor citizen attitudes towards government, political institutions and the political system in general—first in the US and Britain, and subsequently across other European democracies. Survey trends in the last decade show a rather negative picture. In the latest Eurobarometer survey conducted in November 2018, over 60% of all Europeans claim not to trust their national parliament and national government. (Eurobarometer 90, November 2018). There are significant cross-country differences of course, but even among Scandinavian countries, approximately 30% of citizens claim not to trust their representative political institutions. Similarly, in the US, 83% of Americans claim that they ‘never’ or ‘only some of the time’ trust their government to do what is right.

The fact that citizens express primarily negative affective and cognitive orientations towards the people that govern them, their political institutions and processes has been well documented and studied in political science [3,12,24,25,26]. This new pattern of political orientations has been assigned various labels, such as ‘dissatisfied democrats’ [27], ‘critical citizens’ [3,28] or ‘emancipated citizens’ [29,30], emphasizing critical citizen attitudes combined with democratic aspirations. These approaches maintained that scepticism and political dissatisfaction that stems from a political system not living up to the democratic expectations of citizens may lead to positive change in the direction of deeper and more transparent democracies. A crucial requirement is that citizens remain dedicated and positively oriented towards the core representative institutions and principles that underpin democratic systems and that distrust is targeted towards political actors, incumbents and their policies. However, distrust at the specific level, without much change in the perceptions of untrustworthiness of political actors, has persisted for too long. It is possible that distrust of specific executives and political candidates may spill-over to the diffuse level that encompasses the entire political class and political establishment sooner or later and allow forces that challenge the existing democratic arrangements to emerge [31]. The recent surge in theoretical and empirical work that attempts to conceptualise and understand negative citizen orientations, such as ‘anti-politics’ [32] or ‘counter-democracy’ [33], or “grievance models” [18], further showcase the need to better understand negative attitudes and values towards politics.

Existing empirical work has tried to identify the causes of political trust and distrust, as well as their implications for democratic governance [7,8,11]. A number of studies looked at aggregate trust levels from a comparative perspective and explored macro-level variants, broadly categorised as institutional and economic performance or cultural-historical factors [34,35]. Other studies focusing on micro-level determinants delved deeper into the role of individual characteristics, perceptions of government performance in a series of policy areas, such as the economy, crime and security, as well as of individual evaluations of procedural fairness, impartiality and democratic standards [22,36,37]. The effects of individual levels of education, political interest and knowledge, in particular, have been highlighted as contributing to more positive orientations towards political institutions and general levels of satisfaction, although the rise in education levels and simultaneous decline in mass survey trends of trust suggest the empirical link between the two is more nuanced [38].

The insights achieved using survey data of political trust are valuable, but there are many opportunities to supplement such knowledge with qualitative empirical evidence. For example, scholars have already highlighted that the cultural versus economic grievances models are likely to be intertwined [39]. In the lived experience of citizens’ everyday politics, economic and cultural evaluations do not operate as distinct political “models”. Similarly, it is difficult to disentangle the underlying rationale for distrust when multiple crises occur. The Great Recession of 2008 saw severe economic downturns and austerity policies across many European countries but soaring political distrust might have been more a result of the democratic failures, such as the lack of responsiveness and accountability, rather than the poor economic performance [40]. Finally, the way in which distrusting citizens have chosen to behave in the political arena has varied greatly, spanning from support for anti-establishment candidates and anti-systemic parties, preferences for populist rhetoric and acts of political protests to retreat and apathy [41]. While all of these types of behavioural responses are associated to increased political distrust, the way citizens explain and rationalise their motivations for action are still being investigated.

This article argues that an inductive approach to the study of political distrust focused on citizens’ everyday social experience can serve to fill some of the gaps left by the existing approaches of empirical study, which have mainly relied on survey trust indicators. It aims to supplement scholarly knowledge of political distrust—rather than antagonise their findings—and suggest avenues for future research by exploring the meaning citizens assign to their expression of political distrust. This paper starts by asking “what do citizens mean when expressing political distrust?” and “how do they explain their judgement?”. It therefore discusses the key themes that emerge from citizens’ accounts and the evaluations that underlie their decision to distrust. Further, it considers how such judgments vary when evaluating different political agents and provides citizens’ account of how distrust can be contained or can spill-over across political targets. These insights allow us to better contextualise the phenomenon of political distrust in the current climate of a crisis of representation.

3. Methodology: Studying Trust and Distrust from the Citizen’s Perspective

By analysing narrative interviews, this article examines the themes, evaluative processes and behavioural implications of political distrust in terms of citizens’ everyday social experience. It asks how people speak about political trust and distrust, what meaning they assign to these concepts and what evaluative processes are entailed in expressions of distrust. Following a micro-level qualitative approach, this article seeks to collect and analyse people’s understanding of politics, what constitutes trustworthy and untrustworthy politics and how they choose to navigate their political systems in terms of participation, support or protest. I am interested in the meaning participants assign to distrust, the context and themes they bring up when expressing distrust and the evaluations that underpin it. These are important elements of the attitudinal constructs of political trust and distrust. Existing conceptual and empirical work links them to system support and citizens’ political behaviour, but a contemporary qualitative account of these elements is currently lacking.

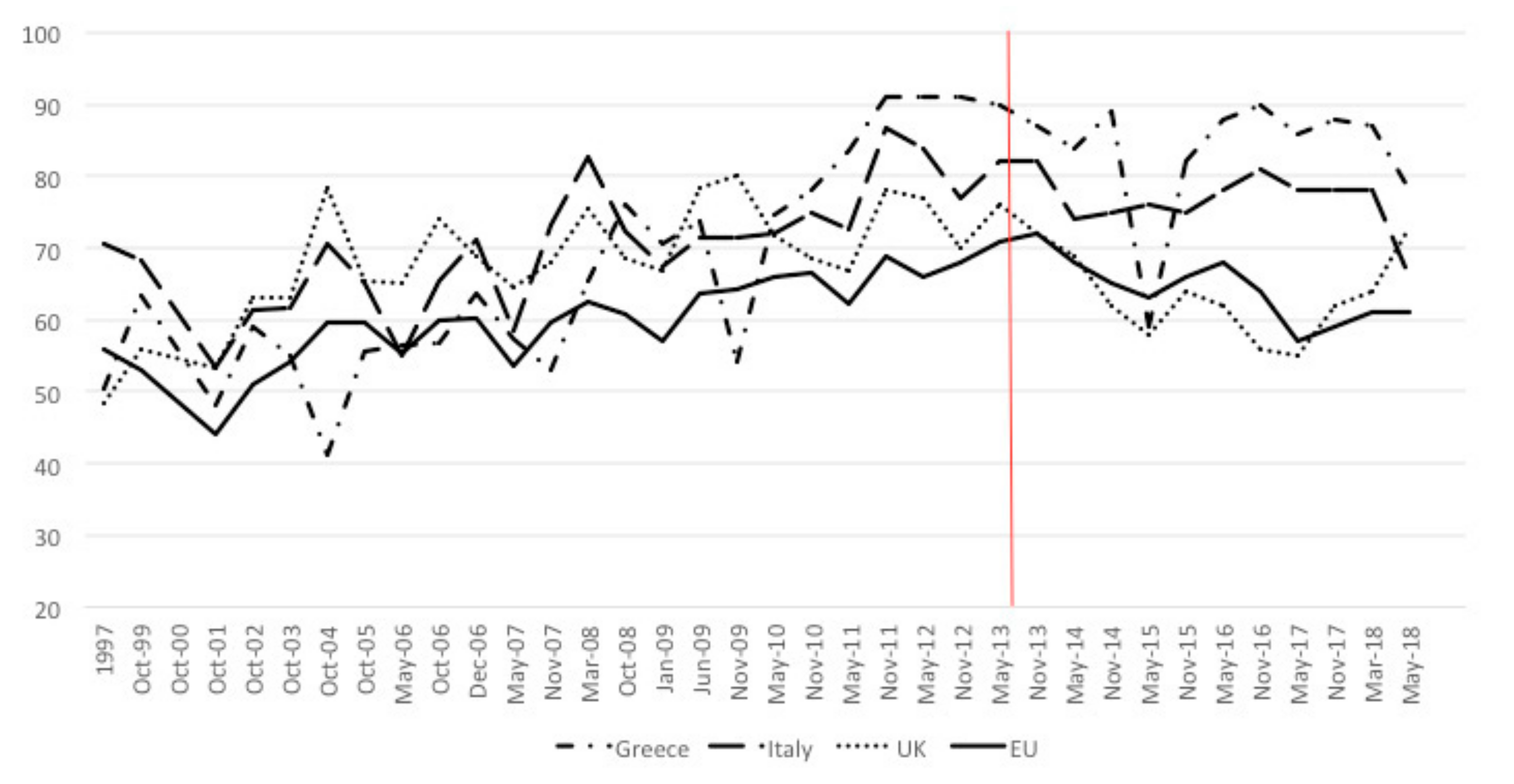

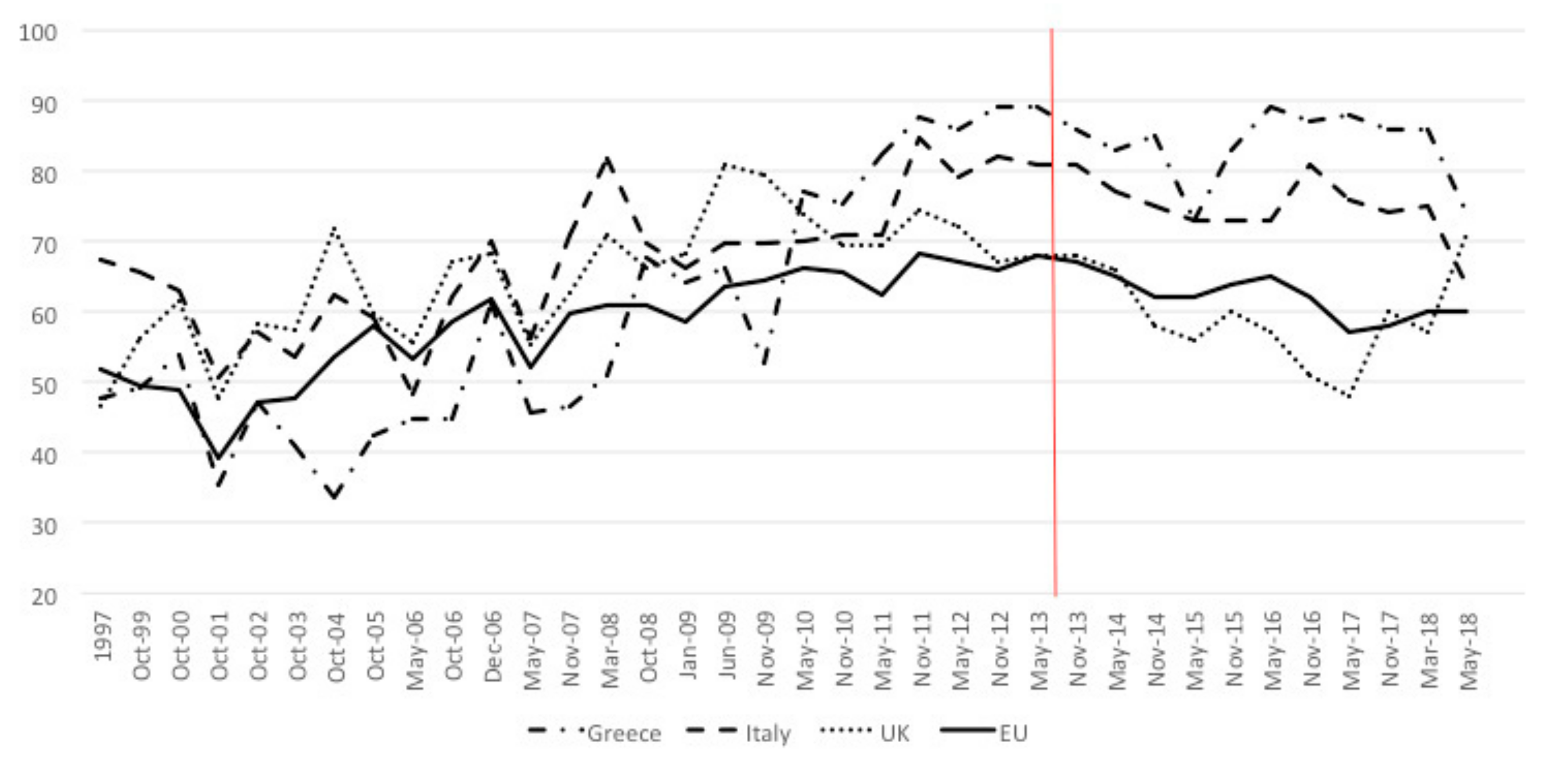

This article analyses popular narrative interviews from three European democracies. Italy, Greece and the UK were selected as cases on the basis of the availability of distrusting political attitudes among citizens. All three countries showcase lower political trust than the EU average, but differ substantively in key institutional set-ups and in their political and historical trajectories known to affect the basis for political trust at the macro-level [40]. Many approaches to research design caution against selecting cases based on the dependent variable [42,43]. This is because it prevents researchers from making causal claims about the relationship between the dependent and independent variables. While this study is not a perfect example of Mill’s method of difference, it is important to note that its aim is not to test specific theories of political distrust or make causal claims. The goal is to explore the meaning attached to political distrust across established democracies and to provide a categorisation for the everyday experience and expression of political distrust. Therefore, the countries studied were selected from the wider group of western established democracies that are plagued by deteriorating citizen evaluations of governments and key political institutions. The contextual differences in the three countries should aid in the generalisability of findings. Figure 1 and Figure 2 below present aggregate levels of distrust in national parliament and national government for Italy, Greece, and the UK, as well as the EU average. There is some variation across time, and trust levels appear to be sensitive to political developments, such as the onset of the financial crisis, the election of the Syriza government in Greece or the Brexit negotiations in the UK. Nevertheless, citizen orientations towards the national government and national parliament have been predominantly negative for a number of years, leading up to the fieldwork carried out in 2013 and have continued to be so since then. In Appendix I reflect more on the case selection, and provide specific information regarding the national contexts and linguistic differences of the three countries.

Figure 1.

Percentage of citizens that ‘tend not to trust’ their national government.

Figure 2.

Percentage of citizens that ‘tend not to trust’ their national parliament. Note: Vertical line marks the start of fieldwork (June–September 2013). The EU average includes all member states after European enlargement. Source: Eurobarometers 48–91.

A number of other countries in Europe, such as the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, could have provided fertile ground for the study of political distrust. However, existing research of political attitudes in these societies has shown that the communist experience and subsequent transition has shaped the way citizens relate and evaluate the state, as well as their community, in a fundamental way that cannot easily be compared to countries without a communist past [34,40]. Britain, Italy and Greece represent nations from a relatively homogenous group of Western European established democracies, which present variation in their historic trajectories, institutional characteristics and political culture. Table 1 presents political, institutional and socioeconomic characteristics that are known to influence political culture and baseline levels of political trust for the year fieldwork was underway.

Table 1.

Institutional, political and economic information on selected countries (2013).

As a social scientific field, political science is inherently interested in meaning. Using an often quoted example in the interpretative tradition by Gilbert Ryle, King et al. [42] comment on the fundamental difference in the meaning of a twitch and a wink—despite the identical appearance of the two actions—to highlight the implications our understanding of such meanings have on social interaction. They explain that “if what we interpret as winks were actually involuntary twitches, our attempts to derive causal inferences about eyelid contraction on the basis of a theory of voluntary social interaction would be routinely unsuccessful: we would not be able to generalise and we would know it” [39,42]. Their point is directly applicable to studies of political behaviour and emphasises the fact that without access to ‘meaning’ any attempt to derive theories around the observable implications of citizen actions would be stifled. Research interest in citizen attitudes of political distrust stems from its theorised consequences on participation, cooperation, compliance and democratic governance in general. Understanding what political distrust means for citizens and how it functions is a necessary step before investigating observable implications that form the big questions in political science.

Popular narrative interviews are a promising way of gaining access to participants’ thoughts on political distrust. Systematised as a research tool that aims to reconstruct events from the interviewee’s perspective, narrative interviews do not simply offer the recounting of events as a list, but comprehensively connect them in time and meaning [44,45]. Narrative accounts can offer important insights into the thought processes involved in political distrust, showing what types of information citizens use, how they evaluate them, the way they interpret events and choose to explain them to a third party [46]. It invites participants to elaborate on already formed attitudes which are often employed as heuristic mechanisms in the evaluation of new evidence and in the decision to act [23]. Further, the participant is at the centre of the story and assumes responsibility for presenting her views, experiences and feelings without interference from the researcher. Though these may not always appear coherent, the encouragement and lack of interruptions by the interviewee and the long length of narrative interviews offers participants the space to retrace their thoughts and connect them in a meaningful way. This interviewing method allows citizens to use their own language when expressing distrusting attitudes, to offer personal interpretations of untrustworthy behaviour and account for their significance. Structured or semi-structured interviews are common methodological tools in qualitative research but allow the interviewer to impose the selection of language, the wording, the type of topics, the timing and ordering of each question [47].

A potential shortcoming of the narrative method stems from the relation citizens’ narratives have to true events and factual reality. This is a valid point that speaks to a wider question within the study of political distrust using a micro-level research perspective: to what extent do citizen perceptions correspond to reality? The attempt to understand political distrust from a citizen’s perspective requires such an approach. Political distrust is an expression of perceived political untrustworthiness. Whether perceptions of political untrustworthiness correspond to factual evidence of untrustworthy conduct on behalf of political actors is a significant, but altogether different question, regarding the untrustworthiness of political systems. The final section of this article revisits this point and the malleability of political distrust in the current polarised information environment and age of “post-truth” politics.

The research is based on 48 narrative interviews with everyday actors (16 interviews in each country) averaging ≈1 hr in length over the summer-autumn of 2013. Using a conversational style, I invited participants to discuss their general opinions on politics and encourage them to elaborate on the views, feelings and episodes they chose to recount. When selecting participants, the aim was not representativeness, as this is not an appropriate measure of rigor in small-n studies [48]. Rather, the aim was to obtain a breadth of narratives and perspectives by interviewing citizens across the political spectrum who belong to diverse social groups. Study participants represent a varied sample in terms of key demographic characteristics known from earlier research to affect baseline levels of trust and distrust in politics, as well as other political orientations (it included among others, university students, pensioners, unemployed, professionals, activists, people with special needs, 1st and 2nd generation immigrants who have obtained passports, local volunteers). A detailed list of the entire sample and country groups is available in the Online Supplementary Materials, Appendix II. Overall, participants formed a mixed gender group (50% female), belonging to a variety of age groups (average age 41.8 years) and socioeconomic status (following the ESEC classification). Geography is also an important factor in the distribution of political distrust attitudes in each country and related political variables [9]; therefore, in order to increase the diversity of the sample, interviewees were recruited from three different geographical areas within each country, which included a big city (capital or financial centre), a smaller urban setting and a rural area.

Participants were recruited for this study in two ways. The majority of participants were approached ahead of the interview through referral networks of local people who did not participate in this study themselves but were asked to nominate other citizens who may be willing to participate. The remaining participants were invited to participate in an interview selected ‘on the spot’ from social settings, always with the aim of recruiting as diverse a sample as possible in all three national contexts. Two-thirds of participants were contacted in advance and recruited via this ‘second-referral’ method, and one-third of participants was recruited ‘on the spot’ in social settings (cafés, piazzas, restaurants). While every effort was made to obtain a diverse and balanced interviewee pool in terms of demographic characteristics, it is possible that people self-select to participate in this study on the basis of their existing political outlook, their interest in politics or even time availability. For this reason, the purpose of this study was not mentioned explicitly, and ‘distrust’ was not mentioned in any of the correspondence with participants or introductory information. Furthermore, participants who initially claimed not to have much to say or to be uninterested in politics were specifically encouraged to participate in this study and efforts were made to meet with busier participants in convenient locations (close to their place of work, during a 1 hour lunch break or after work). For the purposes of our study, it was important to not refer explicitly to the issue of political distrust, as this could predispose participants and introduce acquiescence and response bias in their accounts. The purpose of this study was introduced as an effort to better understand how (British/Greek/Italian) citizens think about politics, politicians and institutions in their country.

Interviews were conducted with the help of a handful of thematic headings to trigger thoughts and ideas on political evaluations and distrust. (The list of thematic headings and interviewee interjections is available in the Online Supplementary Materials, Appendix II). Each interview commenced with the same prompter asking participants: “What are your thoughts about politics in England/Greece/Italy?” According to Jovchelovitch and Bauer’s [45] systemisation of the narrative interview, the researcher managed to pose as an ‘outsider’ in all three national contexts with limited information about political developments and past events, and had minimal input throughout the interview, using only follow-up and encouraging remarks. Interviews averaged 58 min in length (min 41–max 79 min), providing approximately 2770 min of narrative content. The length of interviews and general approach to the subject of politics varied across participants, depending on their willingness and ability to express their views on politics uninterrupted for extended periods of time. A potential limitation of the narrative interview methodology is that certain social groups and cultural contexts are better able to take advantage of the unstructured and open nature of the interview. Narrative interviews seemed to work well in all three countries, but there was variation in the length and content of narrative accounts among people with different levels of political interest and political knowledge, as well as the eagerness of citizens to share their views between Greek, Southern Italian (more eager), and Northern Italian or English (less eager) participants. Interviews were conducted in the native language of the participants.

The following sections of this article analyse the collected data by engaging with the narratives and meaning of political distrust, the evaluations and targets of distrusting judgments as well as the emotive and behavioural implications citizens ascribe to political distrust. To do this, interview content was analysed in a stepwise procedure of text reduction and categorised in line with Bauer [44]. These steps, presented in Table 2 below, represent an eclectic collection of the most appropriate phases of qualitative analysis for political attitudes, in line with Creswell [49] and Tesch [50]. Thematic analysis offers a highly robust set of tools for the systematisation and study of qualitative data [51]. It begins with “careful reading and re-reading of the data”, in order to identify common themes that can be synthesised in patterns describing the concept under study [52]. Thematic analysis of narrative content provided manageable amounts of information and allowed for the identification of common observations, patterns and thought processes in expressions of political distrust across different participants and national contexts.

Table 2.

Seven steps of narrative content analysis.

4. Analysis and Discussion

The aim of the qualitative study of political distrust is to uncover the meaning, expression and underlying evaluation of distrusting attitudes across democracies. While individual judgments and their explanations are a personal matter, the goal was to gather enough evidence that would inform our understanding of political distrust across different citizen groups and national contexts. One of the first findings that became apparent from the data was that despite the different national contexts studied, the way participants reflected and explained their orientation towards politics could be analysed together and contribute to the identification of patterns, themes and evaluations underpinning political distrust. While the participants in this study referred to their national political actors, institutions and systems, recounted different events and even drew different conclusions from the same event, political trust and distrust was expressed and explained in a similar way across the three national contexts. As a result, the analysis and discussion presented below are conducted using all material from the three democratic contexts under study. The discussion is also supplemented by interview extracts that are representative (i.e., found in multiple narratives) and serve to demonstrate the themes, evaluations and language citizens employ in their discourse.

4.1. Political Distrust as the Failure of Representation: “It’s as If…Nothing Represents You”

Political trust and distrust are about political representation—or the lack thereof. This theme emerged clearly from narrative accounts in all national contexts. At the specific political level, participants explain how the lack of a political party, group or candidate for them to lend their support to effectively means there was no actor that shares their values and interests. Representation of a citizen’s values and interests was central in almost every narrative of trust, and particularly, of distrust. The failure of representation is expressed in terms of the lack of political actors that promote the values a citizen holds dear (G-1203, G-1205 UK-3102-1105-1209-1210-1207). At the partisan level, political parties or political figures could help to provide this link between the citizen and politics. However, when they fail, the result feels debilitating, as these young participants explain: “There is no one to represent you. So, neither on a lower nor on a higher level can I find anything. That’s why I am telling you they take away your will” (G-1203). “You cannot trust anyone! The simplest example: we will have elections next year and I do not know who to vote for (G-1205).”

Many participants from all three European democracies consider elections and the act of voting as a central feature of representative democratic systems and an integral part of their civic identity. Elections represent the opportunity for each citizen to voice their political will, to participate in the democracy they live in and to articulate their preferences in a meaningful way. Citizens expressed frustration when they were unable to find a party or candidate to support or when they knew that their act of support did not really matter. This meant that there was no way for them to affect the politics of their country or region and was interpreted as a betrayal or invalidation of the system’s democratic promise to citizens. As a result of this democratic failure, participants expressed anger, shame (for not voting), apathy, alienation and reduced feelings of efficacy (I-3201, I-3202, I-2213, I-2216, G-1204, G-1107, G-2108, G-3216, UK-1211, UK-3213, UK-1204, UK- 1210). Even for participants who did not explicitly feel a lack of representation, the act of supporting a political party was used as an example of faith and trust in that party and, by extension, to the electoral process and democratic system. The act of electoral participation validates the core process of representative democracy. A young participant explained: “you are trusting the party you vote for that, if they were to gain power, they would govern in the best interest of the country. If I didn’t have any trust, then I wouldn’t see any point in voting” (UK-3102).

At the institutional level, political distrust emerges in the context of elections when the electoral process is viewed as not functioning properly or failing to give citizens a chance to make their voices heard. This could be because of a perceived faulty electoral system, such as the closed-list system in Italy, which allowed party leaders to rank candidates however they choose. According to participants “choosing who goes into Parliament is a huge power” (I-2112) and they would describe this as “a scandal” (I-3105), “un-democratic” (I-1206) and one of the reasons for the malfunctioning of the central representative institutions. Political distrust arising from electoral system was also evident in narratives in the UK, where the first-past-the-post system made some participants describe voting as a “waste of time” (UK-1105), especially in the case of people living in a safe constituency in which a seat is held by the out-party. This becomes problematic, not only for voters who feel cheated out of their right to express electoral support for their party, but also for participants without any strong partisan preference who believe elections no longer give them the opportunity to “throw the rascals out.” A participant claimed that politicians become complacent and “feel they can do things exactly their way and not worry about their posts, because they know they will be voted in next time” (UK-3213).

Overall, political distrust was discussed in terms of the lack of representation of participants interests and values. The perception of political agents as promoting citizens’ best-interest and protecting their rights is considered equally important for the institutions that legislate and enforce the rules. When probed to elaborate what she meant when she claimed she did not feel represented “in any way”, a young Italian explained: “When I say “you represent me” it means that I give you my idea, it is as if I make this gift of trust in you and you ought to go, with my name and my face and represent me and fight for my interest and not yours. When I say, “I feel represented” for example from the institutions or by the political class, is when I know that my rights will be protected in some way. But in reality, they don’t protect them through laws and they don’t protect them through the justice system” (I-3201).

4.2. Faith and Betrayal: “Lying Point Blank in Our Faces”

The meaning of political trust and distrust can be distilled to the concept of positive or negative expectations. They are both future oriented, employed when deciding future courses of action, and since the future is unknown, trust requires a leap of faith. (It is interesting to note that both in the Italian and Greek language, the words for “trust” and “distrust” originate and contain the root of the word “faith” (fede in Italian, πίστη in Greek). But while faith was not as prominent a theme emerging from participants’ narratives, the theme of betrayal came up in the majority of distrust narratives. Feeling that your trust has been betrayed featured prominently across accounts of political distrust towards partisan actors, governments or the entire political system (UK-1210, UK-1204, I-1206, I-3103, I-1104, I-3105, G-3213, G-1204, G-3206). It also provided a contrast between political distrust and political cynicism (the assertion that one “never expected anything” (G-1107) from politicians or the political system.

This betrayal was explained using various examples from the personal and social experiences of participants. The language employed revolved mainly around lying (UK-1210, UK-1209, UK-1204), the breaking of promises (I-1206), dishonesty and deceit (I-3103, I-1104, I-3105, I-1109, G-3213), being treated as fools and disrespected as citizens (G-1204, G-3206, I-1206, I-1108). It is worth mentioning here one particular example that emerged across narratives of political distrust in the UK: war, and specifically, the Iraq war. The Iraq conflict was not salient at the time of fieldwork. However, when participants began to explain their perceptions of untrustworthiness, the Iraq war was brought up in all but one of the narratives in the UK. It was not just the war in and of itself but the realisation of a lying prime minister, government and parliament that was described as particularly “damaging” for the younger generation (UK-1105), “wrong” and “unethical” (UK-1210, UK-1209, UK-2108, UK-2106, UK-1207, UK-2108, UK-1211, UK-3212, UK-3213, UK-3214). A young professional explained: “When we see people lying, point blank in our faces, because they are trying to force on board their political agenda, it makes it very difficult to take politics seriously. If I think about the war in Iraq that happened in my student years… I remember thinking that they were lying at the time and it just reinforced, in a key time in my life why I didn’t believe or trust anything politicians would say anymore. And I think that caused a lot of damage to a whole generation” (UK-1105).

Other examples that were recalled following this theme of untrustworthiness as dishonesty, disrespect and betrayal of promises revolved around the commitments of political parties (the hike in university tuition fees by the Liberal Democratic party in 2012–2013 in the UK; numerous promises to initiate reforms in Italy, campaign promises abandoned and economic reforms in Greece). These expressions of political distrust had been building up and were often accompanied by anger. Participants would proclaim: “a promise is a contract!” (I-2213) and explain how the repeated betrayal of promises are ominous for the political actors involved. Another participant warned her political party “so, if once more you have fooled us, I think that in the next election, there will be a cataclysm!” (I-1206). (Interestingly, this party member of the centre-left Democratic Party warned against them joining a coalition government with Berlusconi’s centre-right party, after repeatedly vowing never to do so. Indeed, after the grand coalition government of 2013, both parties saw a large drop in their vote share in the subsequent elections of 2018, which marked the rise of the far-right Lega and populist 5 Star Movement).

4.3. Emotive and Behavioural Responses: “They Take Away Your Will”

The rich theoretical work on trust and distrust has given rise to two understandings based on a strategic model and a normative reciprocity model. The strategic model advanced by Hardin [53] and colleagues emphasizes the calculations involved in the decision to trust or not trust, based on past experience and evidence regarding the trustworthiness of the agent in question. The model of positive/negative reciprocity highlights the norms that govern exchanges in a given collective [54]. While both models are conceptually useful, narratives that framed expectations on the basis of past experience and evidence represented a more calculating, disinterested and detached way of expressing trust and distrust and were not as common across narratives. Participants who were able to “read the balance” of their sentiments or emphasised the separation between “good apples from bad apples” when it came to the political class, political actors and outputs, usually expressed some trust towards the political system and only specific distrust towards identified actors (UK-2106, UK-1207, UK-2108, UK-1209, I-3103, I-2115, G-1102, G-1201).

What was more prominent in participant narratives of distrust was a much more personal, emotional and normative approach using intense language and value judgments. Pervasive political distrust was expressed using profoundly personal and emotional language and describing intense reactions. Participants would refer to the untrustworthiness of the political system and the political class as a force of “destruction” (G-3213) that “takes away your will” (G-1203) and causes the “loss of your identity” (I-3202). Once the feeling of being repeatedly ‘deceived’, ‘manipulated’ or ‘fooled’ spreads, the emotional state attached to distrusting attitudes moved from anger and frustration to fear, insecurity and despair. Fear and uncertainty are omnipresent in expressions of diffuse political distrust (UK-1210, G-1203). While expressions of trust signalled a state of stability, normalcy and were seldom accompanied by strong responses, the emotive and behavioural responses of pervasive distrust were impossible to miss in participants’ narratives. Participants found that trying to shield themselves from interactions with an untrustworthy political system seemed impossible. Fear and anxiety was expressed in personal terms, such as not knowing “what the dawn will bring for me” (G-2111), everyday actions bringing “a terrifying sense of insecurity” (G-2209) and explanations that the lack of security for the citizens of a country, whether physical, economic or social “means war” (G-3115). Even in cases of specific distrust where participants tried to re-orient themselves towards other political actors (UK-1204) and find trustworthy agents elsewhere (UK-1209), there was the realisation that “if I didn’t trust them, what is the alternative really? Worrying? Panicking?” (UK-3102). The inability to proceed with your life and business as usual was expressed using language that referred to cyclicality (I-3103, I-3105, I-1108, G-1212, G-3213, G-3114), “like a dog chasing its own tail” (I-1206), and to contagion (I-1104, I-1207, G-2110, G-2111, G-3115, G-3216), “in practical terms, this is what untrustworthiness means; in the end, you become untrustworthy as well, they pass it on to you...” (G-1204).

4.4. Political Untrustworthiness: Technical, Ethical and Interest-Based Evaluations

As mentioned above, political distrust was expressed across citizen narratives as the belief that the system and its actors are untrustworthy, and therefore, that any interaction with them exposes citizens to risk and harm. Delving deeper into these perceptions of untrustworthiness, three evaluative components that follow technical, ethical and interest-based considerations emerged from the data. Technical evaluations refer to competent “management of things” (G-1102, I-2110), “getting things done” (UK-2101), overall political performance (I-2116, I-1111), political outputs and, in particular, good economic outcomes (UK-2108, G-3213, I-2112). These assessments appear to be in line with existing empirical research that highlights the importance of economic and institutional performance for political trust.

Yet, even more prominent than evaluations regarding the technical competence of political actors and technical functioning of political institutions, were evaluations of a normative nature. These evaluations are also visible in the extracts of the earlier sections that discussed the themes of representation, trust betrayal and emotive responses. Political distrust was far more commonly explained as the belief that political actors behave in a way that violates the shared moral norms of fairness and justice, than of technical incompetence. Similarly, it was the normative component of institutional performance that was central in judgments of untrustworthiness. Political distrust of institutions and the political system in general reflected the belief that the operations and outcomes failed to uphold democratic principles of fairness, failed to protect the weakest in society and failed to punish political wrongdoing (I-3103, I-3105, I-1108, G-1212, G-3213, G-3114, UK-1210, UK-1209, UK-2108, UK-2106, UK-1207, UK-2108, UK-1211, UK-3212). Poorer technical skill or political outputs could be “excused” up to a certain extent. In the words of an older participant “if you accept that no human being is infallible, then they [politicians] shouldn’t be pilloried for that…unless they are being dishonest” (UK-2108). Dishonesty, corruption, preferential treatment and patronage, the influence of special interest and personal gain are all perceived types of behaviour that violate universal moral norms of how people in a position of political power ought to behave. Similarly, a system that allows such violations to go unpunished is seen as equally untrustworthy on ethical grounds. Once citizens no longer expect that political agents violating democratic norms will be caught and disciplined, representative political institutions are at risk (UK-1207, I-1104, I-2213, I-2214, I-2115). A participant who had the opportunity to get involved in politics in her region expressed her experience in these words: “I said, ‘that’s great, I can go and effect things’, but then I saw the opposite, which is just corruption or gain. So I haven’t seen anything, to be honest with you, that really inspires me and makes me think this is ethical, because it doesn’t feel ethical to me” (UK-1210).

Finally, the third evaluative dimension that underpins perceptions of political untrustworthiness relates to incongruent interests. Whereas ethical evaluations of untrustworthiness tend to make reference to universal moral norms (honesty, fairness, justice) or sociotropic democratic norms (elected representatives ought to promote constituents’ interests, not their own), interest-based evaluations reflect more the personal interests and preferences of citizens. Participants would refer to these evaluations as policies and actions on “things that are relevant for me” or “whether my politics is being listened to” (UK-1210, UK-2108, I-2115). This dimension emerged frequently in partisan evaluations, where individuals may trust a specific political party or politician to protect them but distrust the motives of other parties and the effect their policies might have on their professional and personal life (G-2108). A young Italian professional remarked upon the difference between ethical and interest-based evaluations of political untrustworthiness he saw between his generation and the generation of the baby-boomers. Talking about the rise of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement he suggested: “In my opinion, people like me and those below the age of 40 tend to rationalise it in this way: it doesn’t matter whether someone is truly good or truly honest, what matters is that once he is exposed, whether I can punish him or not. It’s more a discourse of accountability, let’s say. Those who are older and have been socialised in the time of the First Republic, with big ideologies before the fall of the Berlin Wall, my parents or others, tend to view it, certainly in such a way because of what has happened in the past few years with all the scandals, but underneath it all they have specific expectations. They say, “I want a politician that cuts the tax on the first house”, “I want a politician that will protect pensions”, “I want a politician…” and so they have a point of view that is a bit more geared to the actual mandate” (I-2115).

As is evident in the above extract, most often judgments of untrustworthiness contained a mixture of technical, ethical and interest-based evaluations. For example, perceptions of corruption (petty or systemic) carried a combination of evaluations, spanning from the inefficiency and failure of the public domain to the unfairness of such practices and the negative impact it had on participants or those in their inner circle. Similarly, discussions regarding the economic downturn and tough austerity policies enacted in all three countries during the Great Recession carried judgments of technical incompetence, dishonesty and unfairness, as well as negative impacts for the participants and those closest to them. However, what emerged from the narratives across these three national contexts was that distrust was overwhelmingly expressed in ethical terms. This is in line with recent work that suggests diffuse distrust is more a response to failures of democratic norms rather than failures of technical and economic outputs. Crucially, this finding also helps explain how pervasive distrust offers fruitful ground for anti-establishment and populist rhetoric, which target the “morally corrupt political elite” [31]. Existing research has shown that attitudes underpinned by moral convictions are held more fervently, are more resistant to change and are more likely to motivate action. It also poses an additional challenge for the reversal of political distrust, since regaining moral credentials for entire institutions and processes is a difficult endeavour. This is not to argue that technical considerations of competent management and good outputs or interest-based evaluations are irrelevant to political distrust. All these evaluations are present and often intertwined in narratives of distrust. Nevertheless, the qualitative evidence analysed in this study help to highlight the importance of the ethical component in judgments of political distrust. Table 3 below summarises the most common expressions of political distrust following technical, ethical and interest-based evaluations, keeping in mind that the distinction between the three evaluative components empirically is not always clear cut.

Table 3.

Evaluative components of political distrust.

4.5. Targets of Distrust: “Those Who Govern Are to Blame, Not Me!”

A big unresolved question in the trust literature is whether decreasing levels of political trust and heightened distrust represent a threat to diffuse system support [3]. While political trust was originally conceived of as a measure of diffuse support [20], the relational nature of trust and distrust and the evaluative dimensions that underpin them appear to be better directed to agents, rather than impersonal institutions, processes or regimes. Narrative content provides the opportunity to identify and categorise the political targets of distrust and to examine whether the language and judgements citizens employed to express their distrust followed similar patterns across incumbents, institutions and the system. Table 4 below adapts Norris’ [3] objects of system support to present how participants in this study expressed distrust towards political targets from specific to diffuse levels. As mentioned already, participants used the concepts of trust and distrust (as well as trustworthiness and untrustworthiness) when speaking about political actors (candidates, politicians, leaders), groups of actors (parties, governments), political institutions (parliament, ministries) and the political system in general. In all cases, expressed distrust followed technical, normative and interest-based evaluations, though the precise language used was slightly different in expressing the untrustworthiness of actors and the untrustworthiness of institutions. Table 4 below indicates what aspects participants referred to when expressing distrust towards different political objects.

Table 4.

Targets of political distrust and their components.

Perceptions of untrustworthiness based on technical, ethical and interest-based evaluations appear straightforward when the target is a political actor. Participants referred to the individual behaviour of the actor (lying), her characteristics (incompetence, dishonesty) and her political acts (promoted agenda, policies voted for or enacted). Similarly, when discussing political parties and governments, many participants referred to the actions of the individual members of these groups. In the case of the government (the national cabinet either partisan or coalition), evaluations included an additional layer where participants would refer to the “government” in general as the democratically elected leadership responsible for the current state and overall direction of the country. This resulted in a more blurred attribution of untrustworthiness that encompassed “all those who govern”. For political institutions (representative and administrative), specific roles and functions were also evaluated. It is crucial to note however, that there was wide variation as to how participants chose to refer to key political institutions, in particular to their national parliament. While some insisted that “you have to think of institutions as a ladder” (I-3103) and that it is important to distinguish between an institution and the people occupy positions in it “because the quality of the people is a different thing from the quality of the institution” (G-1201), others insisted that “you identify the Parliament more with the people inside” (G-1203). Even in broader terms than the core representative political institutions, in narratives of political distrust, the political system was often equated to the existing political class; participants claimed that “the system and the politicians are so close, that it is impossible to separate them” (G-1107) (I-2213) (I-1207). Participants would say “I don’t know exactly if the mayor is to blame, if politicians are to blame or whoever… But in essence, those who govern are to blame, not me!” (G-2111). In many cases, it also reflected the belief that the political system is effectively controlled by the people inhabiting its institutions and the government and it ensures a continuous state of untrustworthiness (I-2213). Insights from narratives of political distrust add to the ongoing debate in the political trust literature on whether citizens evaluate different political institutions separately [55]. While some scholars have argued that citizens make distinctions in their evaluations of different institutions [14,15], others claim there is no evidence to support such a distinction and that political trust and distrust judgements reflect the prevailing political culture of a system [9]. This study finds both approaches to have merit for different types of citizens and evaluations. Participants who expressed strong systemic distrust and those who were less politically sophisticated tended to group individual actors, their behaviour, the institutions and the political system all in one pot, whereas participants who expressed specific distrust and those who were more informed about politics tended to differentiate in their evaluations of political targets.

Disentangling the targets of political distrust and the evaluations towards different levels of the political system can also provide an insight into the process of distrust spill-over to different political actors and, crucially, the spread of distrust from specific to systemic actors. This was an unanticipated finding of this study, which was made possible by the open nature of the qualitative narrative interviewing method. In many narratives of political distrust, the key to containing distrust was to attribute untrustworthiness to political actors and processes that were eventually replaced. Participants referred to procedures that ensured untrustworthy behaviour is caught and punished, as boosting overall system trust. A participant speaking about the UK’s involvement in the Iraq war said: “That was when the public system, that was when the British system was really let down. […] That was terrible. It was a disgrace... Well you hope that the system will prevent that from happening again. And I think the fact that David Cameron wasn’t able to get involved in Syria was a really positive thing, yes” (UK-1209). While of course war assessments differed across narratives, for many study participants in the UK, fall outs from the Iraq war or the MP expenses scandal or the betrayal of campaign promises appeared to be contained to the people and political leadership involved, “ring-fencing” trust towards the political institutions, and potentially even the political parties involved, once leading politicians were replaced.

On the other hand, the repetition of trust betrayal, the continuous process of participating in democratic politics only to find that one group of untrustworthy politicians is followed by another group of untrustworthy politicians, enables distrust to jump from the specific to the diffuse level. “So, one tells you: Vote for me and I will try to change the country”, a participant from Italy explained, “but in the end, having only seen the opposite of this for years and years, one loses trust and hope completely” (I-1111). Similarly, supporting reforms for processes and institutions that yield no result in terms of their technical operation, democratic norms and representativeness, slowly but surely builds up and morphs into a belief that the system is “crooked” (UK-2110,) and that it will remain “fundamentally corrupt” (G-1203, G1205, I-1109) and resistant to change (G-1201, UK-1207, I-2213, I-2115) no matter what. There is, therefore, an important link between attitudes of political distrust towards specific actors, such as the current government, incumbents or political parties, and the systemic level: eventually, unremitting specific distrust spills over to institutions and eats away diffuse system support. For participants who expressed systemic distrust defending representative institutions in times of crises became very difficult. These were the participants who were more open to complete system overhaul, who considered giving a chance to anti-establishment parties and actors and who found alternative models to party-based representative democracy more appealing. These were also the participants who were more likely to cut ties with their political system, either by moving abroad or by insulating themselves in their locality.

5. Conclusions

The failure of political representation, feelings of manipulation, promise breaking, rule breaking and institutional failure are prominent themes emerging in expressions of political distrust. While this analysis does not offer an exhaustive list, identifying common themes together with the underlying technical, ethical and interest-based evaluations of untrustworthiness provide additional insights into the meaning and significance of political distrust from the citizens’ perspective. Firstly, this study found the structure of political distrust as it is expressed by citizens to be similar across the three countries. The common underlying technical, ethical and interest-based evaluative components of political distrust suggest that citizens make sense of their political world in much the same way in western democracies and that their cognitive and affective response patterns to political actors are similar. While the level of distrust or the resulting judgment varied from individual to individual, qualitative evidence showed that political distrust is a concept that makes sense for citizens and that it is understood and employed in a similar manner in the three national contexts studied. Results might have been different if this study had included post-communist countries, where the democratic link between citizens, political elites and institutions has had less time to develop and economic performance is known to be more central in political evaluations [35]. Nevertheless, I expect these findings to generalise across established industrialised democracies and to provide a good starting point for the comparative study of people’s understanding of political distrust across a more diverse set of societies.

In particular, qualitative evidence highlights the importance of the normative component of distrusting attitudes, adding to a strand of literature which argues that failures of democratic principles are more relevant than the extent of economic contraction in explaining the rise and resilience of political distrust in countries hit by the Euro Crisis [40]. The high ethical standards citizens set for their representatives and representative institutions also help to account for the fertile ground distrust provides for the increased support for populist parties, and appeal of populist candidates [31]. While it is important not to equate populist attitudes with political distrust, the emphasis populist messages places on moral discourse and the Manichean view of the world means this rhetoric is very effective where ethical evaluations have given rise to perceptions of political untrustworthiness.

It is extremely difficult to link attitudes to behaviour empirically, but the narrative interviewing method allows participants to connect their judgements with their behaviour in a coherent pattern of cause and effect—to offer rationalisation and examples for their actions. It is definitely a subjective depiction of one’s behaviour, but it is a valid input, nonetheless. Emotive and behavioural implications of political distrust emerged frequently across participant narratives. Whether deciding to remove themselves from the democratic process of election altogether, not voting for the specific party that has betrayed their trust, supporting radical parties in an effort to change the system or consciously standing up against the law and refusing to contribute any further to the citizen–state relationship, participants painted a picture of political distrust as “action and reaction” that, when spreading to the systemic level, has intense and profound implications on their life.

Finally, narratives of political distrust point to the fact that there is a qualitative difference between distrust directed towards specific political actors and distrust that has spilled over to the systemic level, in terms of the behavioural and emotive reactions. Crucially however, the underlying perceptions of untrustworthiness and the process of spill over is fundamentally the same. A key take away from this study is that persistent specific distrust will eventually become systemic. Therefore, the continuous disapproval and dissatisfaction with the actions of incumbents and governments in terms of technical competence, normative stance and interest representation is something that should alert scholars and political representatives alike. The normative evaluations entailed in distrusting judgments, along with the perceptions of a failure of representation, provide a fertile ground for the appeal of populist messages and “untrustworthy” citizen behaviour. These also represent areas where further research can be very fruitful for the scholarly understanding of political trust and distrust and their implications. Specifically, large-N quantitative research employing panel data can provide further insights into the process of distrust spill-over over time. Similarly, research that aims at disentangling the normative from the instrumental and interest-based components of distrust using survey methodology and studying their prominence in motivating political action would greatly enhance our ability to formulate recommendations for battling political distrust among established democracies.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4698/9/4/72/s1, Online Appendix ‘Political Distrust and its Discontents’. Reference [56] are cited in the supplementary materials.

Funding

Part of this research was supported by the Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (scholarship for Hellenes F ZI 041-1).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following individuals who have provided feedback on this work: Michael Bruter, Sofie Marien, Silja Hausermann, Daniele Caramani, Marco Steenbergen, Malu Gatto, as well as other colleagues at the University of Zurich and the London School of Economics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Citrin, J.; Stoker, L. Political Trust in a Cynical Age. An. Rev. of Pol. Sci. 2018, 21, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmerli, S.; Van Der Meer, T.W.G. Handbook of Political Trust; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsou, E. Rethinking Political Distrust. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2019, 11, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H. Political Issues and Trust in Government: 1964–1970. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, R.J. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices: The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, M.J. Why Trust Matters: Declining Political Trust and the Demise of American Liberalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Rudolph, C. Why Washington Won’t Work: Polarization, Political Trust and the Governing Crisis; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marien, S.; Hooghe, M. Does political trust matter? An empirical investigation into the relation between political trust and support for law compliance. Eur. J. Political Res. 2011, 50, 267–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; Stoker, L. Political Trust and Trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2000, 3, 475–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmerli, S.; Hooghe, M. Political Trust: Why Context Matters; ECPR Press: Colchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, G.; Verba, S. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbing, J.; Theiss-Morse, E. Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs about How Government Should Work; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, J. Comment: The Political Relevance of Trust in Government. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1974, 68, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, V. Distrust and Democracy: Political Distrust in Britain and America; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, T.E.; Gronke, P. The Skeptical American: Revisiting the Meanings of Trust in Government and Confidence in Institutions. J. Political 2005, 67, 784–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P.; Inglehart, R. Cultural Backlash. In Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rosanvallon, P. Counter-Democracy: Politics in the Age of Distrust; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Systems Analysis of Political Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support. Br. J. Political Sci. 1975, 5, 435–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, M. Procedural Justice and Political Trust. In Handbook on Political Trust; Sonja Zmerli, S., Van der Meer, T.W.G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, M.J. The Political Relevance of Political Trust. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1998, 92, 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, R.J.; Welzel, C. The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, J.; Zelikow, P.; King, D. Why People Don’t Trust Government; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Crozier, M.; Huntington, S.P.; Watanuki, J. The Crisis of Democracy: Report on the Governability of Democracies to the Trilateral Commission; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann, H.D. Dissatisfied Democrats: Democratic Maturation in Old and New Democracies. In The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens; Dalton, R., Welzel, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 116–157. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Welzel, C. Are Levels of Democracy Affected by Mass Attitudes? Testing Attainment and Sustainment Effects on Democracy. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 2007, 28, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, C. Freedom Rising: Human Empowerment and the Quest for Emancipation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, C. The Populist Zeitgeist. Gov. Oppos. 2004, 39, 542–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.; Stoker, G. The Impact of Anti-Politics on the General Election 2015. 2015. Available online: http://sotonpolitics.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2019).

- Rosanvallon, P. The Metamorphoses of Democratic Legitimacy: Impartiality, Reflexivity, Proximity. Constellations 2011, 18, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. Trust, Distrust and Skepticism: Popular Evaluations of Civil and Political Institutions in Post-Communist Societies. J. Political 1997, 59, 418–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishler, W.; Rose, R. What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-communist Societies. Comp. Political Stud. 2001, 34, 30–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanley, V.A.; Rudolph, T.J.; Rahn, W.M. The Origins and Consequences of Public Trust in Government: A Time Series Analysis. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothstein, B.; Stolle, D. The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust. Comp. Political 2008, 40, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, Q.; Hakhverdian, A. Ideological Congruence and Citizen Satisfaction: Evidence from 25 Advanced Democracies. Comp. Political Stud. 2017, 50, 822–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, C.E. Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Torcal, M. Political trust in Western and Southern Europe. In Handbook on Political Trust; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 418–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kriesi, H. The Political Consequences of the Financial and Economic Crisis in Europe: Electoral Punishment and Popular Protest. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2012, 18, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Keohane, R.; Verba, S. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Della Porta, D. Comparative analysis: Case-oriented versus variable-oriented research. In Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences: A Pluralist Perspective; della Porta, D., Keating, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 198–222. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, M. The Narrative Interview: Comments on a Technique of Qualitative Data Collection. In Papers in Social Research Methods, Qualitative Series; London School of Economics, Methodology Institute: London, UK, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jovchelovitch, S.; Bauer, M.W. Narrative Interviewing. In Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound: A Practical Handbook; Bauer, M.W., Gaskell, G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2000; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hollway, W.; Jefferson, T. The Free Association Narrative Interview Method. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; Sage: Sevenoaks, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, E. Strategy, identity or legitimacy? Analysing engagement with dual citizenship from the bottom-up. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 994–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tesch, R. Qualitative Research: Analysis Types and Software Tools; Falmer Press: Bristol, PA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Stirling, J. Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qual. Res. 2001, 1, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.; Ezzy, D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, R. Trust and Trustworthiness; Russell Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, V.; Levi, M. Trust and Governance; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, J.; van Heerde, J.; Tucker, A. Does One Trust Judgement Fit All? Linking Theory and Empirics. Br. J. Politics Int. Relat. 2010, 12, 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilopoulou, S.; Halikiopoulou, D.; Exadaktylos, T. Greece in Crisis. J. Com. Mark. Stud. 2014, 52, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).