Abstract

This article explores whether the past few years have witnessed what can accurately be described as a “youthquake” in British politics, following the candidature and election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party. It argues that the British Election Study team, who argue that we witnessed “tremors but no youthquake”, fail to advance a convincing case that turnout did not significantly increase among the youngest group of voters in the 2017 general election in the UK, as compared to the previous election. The article explains why their rejection of the idea of a youthquake having occurred is problematic, focusing on the limitations of the BES data, the team’s analysis of it and the narrowness of their conception of what the notion of a “youthquake” entails. This article argues that there is other evidence suggestive of increased youth engagement in politics, both formal and informal, and that some social scientists have failed to spot this due to an insufficiently broad understanding of both “politics” and “youth”. The article concludes that vital work needs to be done to better conceptualise and measure the political experiences, understandings and actions of young people, which are not adequately captured by current methods.

1. Introduction

This article explores whether the past few years have witnessed what can accurately be described as a “youthquake” in British politics, following the candidature and election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party. The purpose here is twofold: to examine the current data on the youthquake theory, assessing what these data can tell us but also where it is limited in its explanatory power, and to scrutinise the term itself and how it has been understood, placing this debate within the wider context of British politics and developments in studies of youth political engagement. Specifically, this paper argues that the British Election Study (BES) team, who claim that we witnessed “tremors but no youthquake” [1], fail to advance a convincing case that turnout did not significantly increase among the youngest group of voters in the 2017 general election in the UK, as compared to the previous election in 2015. Moreover, in declaring that the youthquake never happened, the BES team, and those who rely solely on their data and analysis, define the idea far too narrowly, focusing only on voting. This article argues, by contrast, that the concept needs to be understood much more broadly and assesses other evidence that there has been a youthquake in Britain, conceived in this way.

The article is structured as follows. First, it traces the emergence of the youthquake narrative in the aftermath of the election, which was driven by opinion polls that suggested that Labour’s better than expected result was due in large part to the support of younger voters. Second, it sets out the arguments advanced by the BES team and explains why its rejection of the notion of a youthquake having occurred is problematic, focusing on the limitations of the BES data, the team’s analysis of it and some significant methodological issues. Third, the article argues that important changes have been happening in British politics in recent years, and in youth politics in particular, and that there is evidence that young people have become increasingly politically engaged. Finally, the article concludes that there are serious problems with how social scientists tend to conceptualise and measure political engagement and that vital work needs to be done to more adequately capture the contemporary political experiences, understandings and actions of young people in Britain.

2. The Emergence of the Youthquake Narrative

Prior to the 2017 general election, Labour had been expected by many pundits to perform poorly, with the party’s leader, Jeremy Corbyn, derided by critics as too left-wing and intellectually uncompromising to be electable [2]. Labour was divided and Corbyn faced strong opposition from within his own Parliamentary party, having to face a leadership challenge less than a year after becoming party leader in 2015. At the time the general election was called, the party was well behind in the polls and it was widely believed by commentators that the Conservatives would significantly increase their majority [3,4]. However, although the Conservatives emerged as the largest party, Labour performed much better than many had expected. The party increased its share of the vote by 9.5% as compared to its 2015 election result (the party’s largest vote share rise since 1945), winning 40% of the votes cast and gaining 30 seats, giving it a total of 262 seats [5]. The Conservatives also increased their share of the vote—by 5.5% as compared to the previous election—winning 42.4% of the votes cast, but actually losing 13 seats [5]. The then Prime Minister, Theresa May, had called the election to strengthen her hand in the Brexit negotiations, but her gamble had not paid off. Having had 330 seats (the party lost a seat in a by-election in 2016), a slender majority of five, prior to the election, the party won a total of 318 seats, leaving it eight seats short of a majority, resulting in a hung Parliament [5]. The Conservatives were thereby forced to form a minority government, relying on support from the Democratic Unionist Party (a party based entirely in Northern Ireland, with its own particular concerns regarding Brexit) on motions of confidence, the Queen’s speech, the Budget and other finance bills, and on legislation relating to the UK’s exit from the EU and on national security.

Following the unexpected success of the Labour Party in the 2017 general election, the neologism “youthquake” was used by the media to describe Corbyn’s apparent success in connecting with younger voters. For example, writing in the Guardian the day after the election, the paper’s home affairs editor, Alan Travis, claimed that: “More than anything else it was a night in which Britain’s younger generation flexed their political muscles to real effect for the first time. The ‘youthquake’ was a key component of Corbyn’s 10-point advance in Labour’s share of the vote” [6]. In fact, “youthquake” was even named the 2017 “word of the year” by Oxford Dictionaries, which defines the noun as “a significant cultural, political, or social change arising from the actions or influence of young people”, the first recorded use of which dates back over 50 years to an editorial in Vogue US in 1965, being used to describe youth culture and its increasing influence on fashion and music at that time [7]. Oxford Dictionaries pointed to “a fivefold increase in usage” of the word in 2017 as compared to 2016, with “youthquake” first striking “in a big way” in June 2017, “with the UK’s general election at its epicentre” [7]. Indeed, shortly after the polling stations had closed, big claims were being made in some quarters about the impact of young people on the election. For example, the Labour MP for Tottenham, David Lammy, infamously tweeted: “72% turnout for 18–25 years old. Big up yourselves” [8]. This seemed to be based entirely on unsubstantiated rumour and, once the opinion polling companies began publishing their data, to have no foundation at all. Nevertheless, the polls did seem to suggest that Labour’s better than expected result was driven in large part by the support of young voters.

The NME exit poll [9], and data from both Ipsos MORI [10] and the Essex Continuous Monitoring survey [11], pointed to there having been a considerable increase in youth turnout in the general election, and that this had contributed to the hung Parliament. Early research by Heath and Goodwin found that the biggest increases in turnout occurred in constituencies with the largest numbers of young people [12]. Organisations such as Bite the Ballot and the National Union of Students (NUS) campaigned to both register young people and persuade them to cast their ballots, and a sizeable number of young people registered to vote in the weeks after the general election was called [13,14]. Figures from Ipsos MORI put turnout of registered 18–24-year-olds at the 2017 general election at 64%, up 21 points from 43% in 2015 and at the highest level since 1992 [10]. YouGov released figures suggesting that 57% of 18- and 19-year-olds and 59% of 20–24-year-olds had voted [15]. In addition, the fact that overall turnout increased to 69%, up from 66% in 2015 [5,16], that there was a significant rise in overall turnout in seats in towns and cities with universities, that seats with the highest proportions of 18–24-year-olds also had above average swings to Labour, and that the party had clearly targeted younger voters and performed much more strongly than predicted by most polls, all suggested that 18–24-year-olds had voted in higher numbers than in recent general elections—and that Labour had benefitted significantly from this. Asked by Andrew Marr in an interview a few days after the election if he was “in this for the long term”, Corbyn replied: “Look at me. I’ve got youth on my side” [17]. Corbyn hailed the role of young people, telling the House of Commons:

More people—particularly young people—than ever before took part in the recent general election. They took part because they wanted to see things done differently in our society; they wanted our Parliament to represent them and to deliver change for them. I am looking forward to this Parliament, like no other Parliament ever before, challenging things and, hopefully, bringing about that change.[18]

The youthquake narrative neatly explained Labour’s better than expected performance in the election and quickly became widely accepted, with commentators discussing the various failings of the Conservative Party’s election campaign, comparing it with the success of Labour’s, especially the party’s effective use of social media [19]—typically used to a much greater extent by younger than older voters—such as Facebook and Twitter, to promote its key messages and its use of celebrity endorsements. For example, prior to the election, Corbyn had been interviewed by the London grime artist JME, after the musician, along with several of his peers, such as Stormzy and Novelist, publicly backed him on social media, using #grime4corbyn [20]. The Labour leader’s apparent connection with young people seemed to be epitomised by his appearance on the Pyramid Stage at the Glastonbury Festival a couple of weeks after the election, with his speech watched by tens of thousands across the site and his supporters singing “Oh, Jeremy Corbyn” [21].

3. The British Election Study: Debunking a Myth?

The BES team published their report [1] (see also [22,23]) at the end of January 2018 and sought to overturn the received wisdom about the election, arguing that the youthquake narrative is largely a “myth”. Prosser et al.’s paper, provocatively titled “Tremors but no Youthquake”, drawing on the BES to compare data from the 2015 and 2017 general elections, suggests that, if anything, there was a slight decrease in turnout for 18–24-year-olds between the two elections [1]. The paper has been seized upon by many media outlets, sparking much debate and controversy. Prosser et al. confidently declare that: “The Labour ‘youthquake’ explanation looks to become an assumed fact about the 2017 election… But people have been much too hasty. There was no surge in youth turnout at the 2017 election” [22]—a claim that later seemed to be bolstered by the British Social Attitudes assessment of 2017 voter turnout (Curtice and Simpson 2018), which, although showing a 6% increase in turnout amongst 18–24-year-olds, found this to not be a statistically significant rise [24].

The BES is widely considered the “gold standard” of post-election analysis. This is because it combines two elements to assess electoral behaviour. First, it analyses data from a large online panel, using the same respondents in multiple waves so that individual level change can be tracked. Second, the BES uses a smaller, face-to-face survey, in which people are randomly selected from addresses across the country and contacted, and, if necessary, interviewers go back over and over again to addresses if people do not initially respond. The use of random probability samples avoids the problem of response bias, whereby the kinds of people who complete online or telephone surveys are more likely than the population as a whole to vote and should, in principle, ensure the best sample possible. Moreover, the BES cross-references its face-to-face survey with checks of the marked electoral registers from the election, so as to verify whether or not people voted [1] (pp. 6,7) [22].

In essence, Prosser et al.’s paper argues that 18–24-year-old turnout differed very little in 2017 compared to 2015 [1]. They argue that, broadly, there was an “anchoring” early on of the youthquake narrative as increasing youth turnout was a specific tactic employed by the Corbyn team and seemed to be working on a superficial level with large numbers of young people turning up to rallies [1] (pp. 2 and 16). They suggest that, when initial aggregate data (turnout increasing in areas with large youth populations) and polling seemed to confirm this, it was seized upon as evidence of a surge in youth turnout [1] (p. 2). Prosser et al.’s paper addresses a number of limitations with the assumptions and data that first generated the youthquake narrative and, quite rightly, points out various problems with aggregate-level analysis and the numerous and significant methodological issues with the polling that suggested a higher level of youth turnout than usual [1] (pp. 4–6) (see also [22,23]). Their criticism of the polling is fairly straightforward and sensible (see [23]), ranging from the fact that they either were not post-election and therefore were estimates of future turnout (Ipsos MORI), were unclear in the methodology deployed (NME) or have issues around the representativeness of the polls (Essex CMS).

Prosser et al. [1] (p. 5) are also on firm ground when they highlight the fact that all the aggregate data prove is that turnout went up in the “sorts of places” (cities) where there were lots of young people, but not that young people were necessarily the cause (correlation, not causation). For Prosser et al. [1] (p. 4), to link age and turnout in the way various commentators have done is to engage in a form of “ecological fallacy”, whereby inferences about the nature of individuals are made based on aggregate data for a group. Thus, Prosser et al. [1] (pp. 5–6) suggest that population density is the determinant factor here, and when they controlled for this the correlation between the number of young adults and turnout disappeared (this is, however, only one variable and incorporating others into their model could have altered these relationships in various directions). They also highlight that, correlationally, increased turnout was more closely linked to those areas that had high numbers of children aged zero to four living there:

What this trend is showing is not that turnout went up amongst toddlers but that turnout went up in the sorts of places with lots of toddlers. The same is true of the relationship between the number of young adults and turnout. Turnout went up slightly in the sorts of places with lots of young adults. That does not necessarily mean it was those young adults doing the extra turning out.[1] (p. 5, emphasis in original)

Here, however, they seem to be being deliberately facetious. The difference is, obviously, that toddlers cannot vote and so simply cannot be the direct cause of rising turnout, but young adults could be. It is not unreasonable for researchers, when faced with x being correlated with both y and z, and y logically not being capable of being the cause of x, to conclude that instead z might have something to do with it. Of course, the reason that there was a relationship for 0–4-year-olds could be because of the large number of young and relatively young adults living in those constituencies and the fact that very young children are more likely to be living with young or relatively young adults than with much older adults. Prosser et al. [1] (p. 5) are correct that the aggregate data they present do show the 18–24-year-old age group displaying the weakest correlational relationship to turnout of the age groups, but it is still a significant one, and the strongest correlational relationship to turnout is the 25–29-year-old bracket (a group that could be defined as relatively “young”, we would suggest). Prosser et al. [1] (p. 4) also argue that aggregate-level analysis may simply reveal “problems with the turnout denominator rather than changes in voting behaviour”, following the introduction of Individual Electoral Registration and the removal of suspected erroneous entries on the electoral register. Whereas previously young people were registered by the “head of the household” along with all eligible residents of the household, this is no longer the case, leading to fears that they are less likely to be registered. However, Prosser et al. fail to provide any actual evidence that this reform affected young people more than other age groups and the large number of young people registering to vote immediately prior to the election, discussed below, is likely to have somewhat muted any effect this may have had. Indeed, as Kellner says:

If more students were on the register in 2017 than in 2015 (including those who converted from one-address voters to two-address voters, to make sure they were able to vote on the day), then it is possible that the number of students who voted last year was higher than in 2015, even if their turnout percentage rate was the same, or even lower.[25]

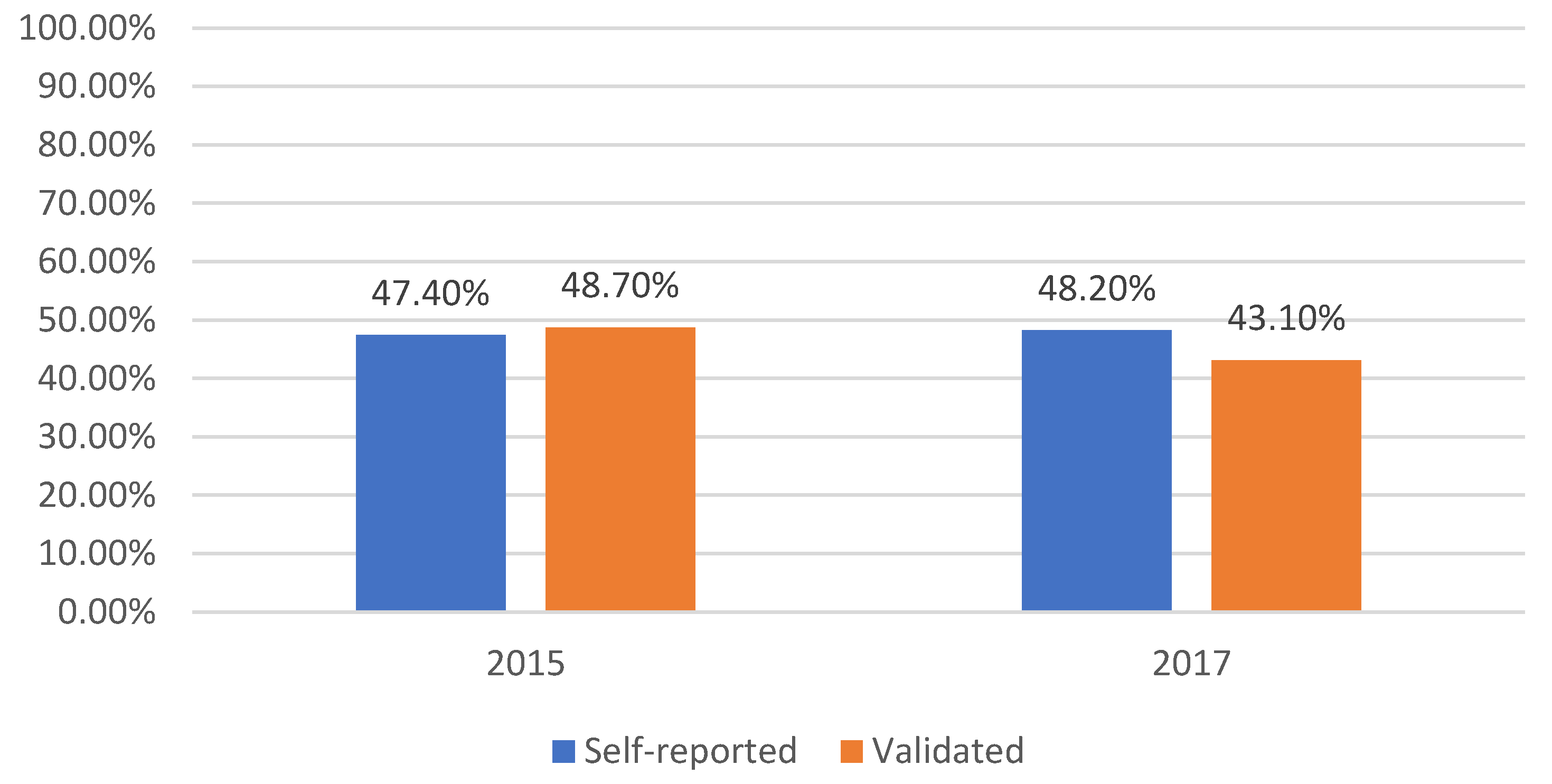

Moving on from their critique of other sources, Prosser et al.’s own data suggest that 18–24-year-old self-reported turnout in 2015 was 47.4% compared to 48.2% in 2017, and validated turnout (obtained by checking responses against the marked electoral register, where voters are marked as having voted at the polling stations on election day) was 48.7% in 2015, compared with 43.1% in 2017, as shown in Figure 1 below [1] (p. 14). Their reported confidence intervals suggest that 18–24-year-old turnout for both years was between 40% and 50% (although Stewart et al. suggest the rather wider 33% and 63% as more accurate for the BES data [26]). Prosser et al. [1] assessed the data through the use of nonparametric means analysis, pairwise comparisons and logistic regression, all yielding much the same conclusion:

There was likely a small increase in turnout across a large age range, with a slightly larger rise for those aged 30–40. The margin of error means that we cannot rule out a small increase (or decrease) in youth turnout in 2017. We can be confident, though, that there was no dramatic surge in youth turnout of the sort suggested by some other surveys. In short, there was no ‘youthquake’.[22]

Figure 1.

The British Election Study’s estimated 18–24-year-old turnout in the 2015 and 2017 general elections. Source: Prosser et al. [1].

There are, however, a number of significant problems with the BES team’s rejection of the notion of a youthquake having occurred in the 2017 general election (a term Prosser et al. [1,22,23] fail to ever properly discuss and explicitly clarify their understanding of). As the former YouGov President Peter Kellner argues, the BES claim that turnout did not significantly increase among the youngest group of voters, “goes way beyond what their data can support” [25]. Prosser et al.’s paper is based on an analysis of data obtained via national face-to-face surveys undertaken after the 2015 and 2017 general elections and the sample sizes were 2987 in 2015 and 2194 in 2017 [1]. However, the sample size the 18–24-year-old turnout comparisons are based on is incredibly small (just 157 in 2015 and 109 in 2017, with sample sizes being considerably higher for most other age groups in their sample). This is a weak basis indeed for such strong claims, especially given the large margins of error that data gathered from very small subsamples suffer from [25]. Predictably, this creates very large confidence intervals for the study (see above). Indeed, when all issues are considered, the margins could be even wider. In short, when confidence intervals are taken into account for the BES data, in purely electoral, numerical terms, a substantial rise in youth turnout is still possible, albeit statistically unlikely (scores at either extreme of the confidence intervals are less likely than those in the middle of the band).

However, the problems go further. Kellner highlights the fact that less than 50% of those contacted for face-to-face interviews actually replied to the researchers [25]. Were those who did not reply more or less likely to have voted than those who did take part in the survey? Conventional wisdom in polling suggests that those less likely to vote are also less likely to respond to surveys, but it is also entirely possible that many newly enthused Corbyn activists were too busy to reply to the survey requests, or were students (who we know are more likely to vote anyway, as voting increases in likelihood with educational level) and who, with multiple addresses, were harder to reach. But, in short, we simply do not know. In fact, as Stewart et al. [26] argue, the empirical basis for Prosser et al.’s [1] rejection of the notion of a significant increase in youth turnout in the 2017 general election is even weaker than Kellner suggests. As they point out, in addition to the less than 50% response rate for the face-to-face interviews, only two-thirds of these were actually checked against the electoral register, which “further compounds the problem of the low response rate” [26]. In fairness to Prosser et al., they are open about the problems with the validation process, and their data leads to the same conclusions, whether one uses the validated or the self-reported measures, but obviously having to rely on self-report measures of political behaviour is always problematic, as well as facing the additional issues here detailed both above and below. Stewart et al. [26] also rightly criticise the BES for the fact that nearly half of the constituencies sampled had no respondents aged 18–24, further calling into question the validity of the survey data.

Perhaps one of the strangest aspects of the data in the BES that Stewart et al. query is the large discrepancy between youth self-reported turnout and validated turnout [26]. Stewart et al. [26] suggest that it is somewhat paradoxical that the difference between these two is larger than any other age group (suggesting a heightened sense of the social desirability of voting amongst this group, and therefore more 18–24-year-olds lying than in other age groups), but also that the number of 18–24-year-olds that admitted not voting was also higher than any other age group (suggesting that, if anything, the social desirability of voting is lower amongst this age group). This is compounded by two other points: first, that it is well established in the literature that young people have a weaker sense of duty with regards to voting (not to mention a general disillusionment with formal political institutions) and, second, that for some of the other age groups in the study, validated turnout was somewhat higher than reported turnout, suggesting that some of these voters reported that they had not voted when in fact they had! Indeed, differences between self-reported and validated turnout for all age groups varied widely and wildly in the BES data, a strange occurrence and one Prosser et al. [1] offer no real explanation for. When one considers the complications of youth voting, of reaching young people and having the right constituency for them (due to students being able to be registered in two constituencies, and also being resident in separate homes at different times of the year), it seems perfectly plausible that the unusually large gap between self-reported and validated turnout is not entirely down to untruthful reporting of voting, and instead is at least partly due to issues with validation.

4. Tremors but No Youthquake?

The BES team have not, therefore, provided compelling evidence that turnout did not significantly increase among the youngest group of voters in the 2017 general election. Even on this very narrow issue, the claims and framing of the BES team appear to go well beyond what the robustness of their data actually warrants. There is also, of course, the important caveat that the BES is just one dataset, just one study, with other (admittedly problematic) datasets revealing alternative findings. More data and analysis, gathered from a variety of sources utilising a range of methods, are needed before firmer conclusions can be made about youth turnout, and, in our view, the possibility that there was a significant increase in 18–24-year-old turnout in the 2017 general election in Britain cannot as yet be ruled out.

There are also factors to be considered other than just voter turnout estimates. The run-up to the 2017 election saw record numbers of young people registering to vote [13], with 246,487 18–24-year-olds registering on the final day before the deadline, compared with 137,400 in 2015 [27]. Of course, registering to vote does not mean one will actually go on and do so, and younger people are less likely to be on the register than older voters, which may explain why they might be overrepresented in registrations, but large (and indeed larger than previous years) numbers of young people registering to vote is a sign of increased engagement in itself. There is also some indication that many of those young people registering did choose to vote too, with Sloam and Ehsan finding in the run-up to the election that “57% of 18–24 year olds stated that they were certain to vote” and that this “compared to 46% at a similar point before the 2015 election” [28] (p. 11), suggesting both that such a measure was fairly close to actual youth turnout in 2015 and that, comparing like for like, there was a substantial rise between the two elections.

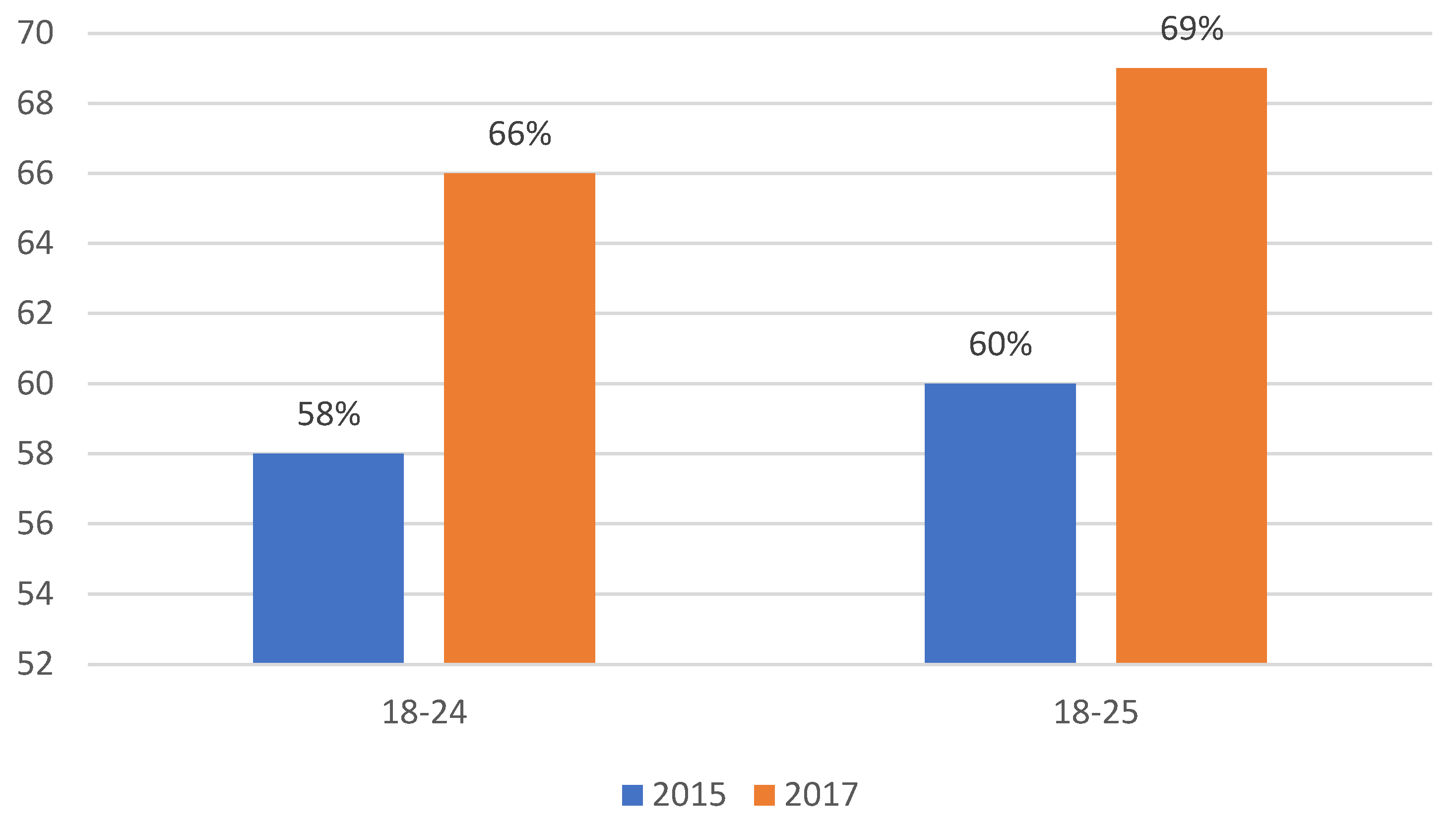

However, even if Prosser et al.’s [1] data were stronger, and we ignore the other evidence to the contrary, in our view, this still would not mean that the idea of the youthquake is redundant. We would make three points here. First, Prosser et al. [1] fail to consider how best to define a “young person” in contemporary Britain [29] (p. 8). As Furlong and others argue, many of the markers traditionally associated with a transition from youth to adulthood, such as entering employment, leaving the parental home, beginning cohabiting relationships or having children, are typically taking place at a later stage in many young people’s lives, as compared to previous generations [30]. As such, to regard “youth” as coming to an abrupt end at age 25, as Prosser et al. [1] seem to, is problematic. Interestingly, Prosser et al.’s [1] own data do show a marked increase in turnout for 25–40-year-olds—only by classifying “youth” as ending at 25 do their data deny any rise in youth voter turnout. In short, their argument actually rests almost entirely on an arbitrary age limit, set without justification. In addition, Sturgis and Jennings [31], in reporting data from the University of Essex Understanding Society Survey, which, like the BES, uses face-to-face interviews to collect data, found an increase in 18–24-year-old turnout between 2010 and 2015 (Curtice and Simpson also found this, as well as a sense of a wider gap between the parties and a slight rise in those believing it to be a duty to vote in the 2017 election [24]). Sturgis and Jennings also report an 8% increase in turnout between 2015 and 2017 for 18–24-year olds, although this was found to be non-statistically significant [31]. However, when the upper band was switched to 25, it became 9% and statistically significant (with an increase of 14% for those aged 26–30), as shown in Figure 2 below. They argue persuasively that this highlights two things: that there was clearly an increase in turnout for younger generations more broadly defined, and given that shifts in statistical significance occur with only minor shifts in age bands, ruling a youthquake out based on rather subjective age boundaries is problematic [31]. In addition, the Understanding Society Survey had the benefit of a much larger sample size than the BES—over 900 participants in its final wave. As Sturgis and Jennings say, this makes the survey better able to detect significant changes in turnout between elections [31].

Figure 2.

Understanding Society estimates of youth turnout in the 2015 and 2017 general elections. Source: Sturgis and Jennings [31].

Second, Prosser et al. [1] also fail to consider polling evidence for what Sloam, Ehsan and Henn [29] (p. 6) describe as the “cosmopolitan-left” attitudes of many young people, particularly young students and young women, as compared to older generations of voters. Indeed, Sloam and Henn uncover evidence pointing to the need to stress the heterogeneity of young people as a group, with gender, ethnicity, social class and education all important factors influencing their political values and behaviour [32]. Nevertheless, part of the notion of a youthquake should be seen as young people displaying distinctive attitudes and orientations on a range of important issues, from Brexit, to the NHS, to austerity, as compared to other age groups. The sharp increase in votes for Labour for all groups below the age of 40 (including the 18–24-year-old group), coupled with the likely effect this had in terms of swings in university towns, suggests a genuine impact in terms of parliamentary arithmetic of Labour engaging more young people than before, even if these were not necessarily previous non-voters. In short, at the very minimum, youth support for the Labour Party helped deny the Conservatives a Parliamentary majority. Prosser et al. [1] (p. 16, emphasis in original), however, question the actual impact 18–24-year-olds could possibly have had in the election (the key way in which they seem to define the youthquake):

If we are wrong about the level of turnout amongst young people and it was in fact as high as 72%... this would be 1.2 million more young voters than 2015. Even if every single one of these extra voters voted Labour (which again, seems absurd) this would only account for about one third of Labour’s vote gains in 2017. This represents the upper bound of possible youthquake effects.

There are several issues here that betray the generally narrow approach Prosser et al. display [1]. As noted above, their argument unsatisfactorily rejects the possible impact of the concentration of youth votes in certain constituencies (i.e., the “student effect”). Stewart et al., for instance, highlight the fact that the likelihood that Labour won a certain seat in the 2017 election was correlated to the number of 18–29-year-olds in that constituency [26]. Indeed, in 2017, age appeared to replace social class as the key demographic determinant of voting choice. As Sloam, Ehsan and Henn [29] (p. 7) argue, issues such as healthcare, Brexit, austerity, poverty, economic inequality and housing, in particular, were key concerns for young people, and Labour was perceived by them as much better on these issues (perhaps suggesting that rather than replacing class, age is acting as something of a proxy for class). It also ignores the role young activists could have played in securing Labour votes beyond their own age group. Moreover, while the Conservative Party’s efforts to attract younger voters in recent years (on which, see Pickard [33] pp. 177–182) predate the emergence of the youthquake narrative, nevertheless, Sloam, Ehsan and Henn [29] (p. 6) point to tangible results of this narrative in changing Conservative Party rhetoric on some policy issues, such as Theresa May’s pledge a few months after the 2017 election to freeze tuition fees. One could also point to the extension of the Help to Buy home-buying scheme, as well as initiatives to promote youth participation in the party, suggesting that perhaps the youthquake has, to some extent, become self-fulfilling.

Third, Prosser et al. [1] define the youthquake far too narrowly [29] (pp. 5,6). As the name suggests, the BES is, of course, concerned primarily with elections, and so it could perhaps be considered unfair to accuse the BES team of focusing on an insufficiently broad set of political behaviours. There are, in addition, a number of proponents of the youthquake narrative who have themselves focused on the term being defined in such terms, and so there is value in a study that addresses this specific aspect of the youthquake. However, as we have already seen, even focusing solely on elections, there are behaviours to consider within an election other than just voting (and, within voting, more than just turnout to consider in terms of impact). Yet the BES team’s arguments rest solely on voter turnout. Moreover, while the BES team focus on just one particular aspect of the youthquake debate, and address specific claims about the youthquake that others have made, this does not mean that they can therefore be let off the hook for failing to discuss what the term actually means and for simply dismissing the notion of a youthquake as a myth. This applies equally to those who have latched on to the BES team’s “refutation” of the youthquake idea too.

To return to the definition provided by Oxford Dictionaries [7], a “youthquake” is “a significant cultural, political, or social change arising from the actions or influence of young people”—hardly a purely electoral phenomenon, even at first glance. It is concerned with the wider impact of young people on society, not just with quantifiable electoral trends. Defining it more broadly opens up a greater range of avenues of political activity that extend beyond engagement with traditional political institutions, since voting is only one way to achieve social and political change. Political action can be as varied as human thought and expression. Politics is concerned, in particular, with issues around power and the consequences for individuals and society of the distribution and exercise of power [34]. Therefore, any action that aims to address distributions and uses of power and their effects should potentially be considered as political. Whilst Westminster obviously plays a central, crucial role in terms of the exercise of power in the UK, it is clearly not the only relevant reference point, and indeed is not the only site of change and contestation, today or historically.

There is, for example, significant evidence that Momentum and the Corbyn campaign tapped into youth culture in a way not seen for some time in mainstream British politics. Labour Party membership increased from around 388,000 in December 2015 to about 544,000 members by the end of 2016 [35] (p. 5), and, as both Young [36] and Pickard [37] argue, youth engagement in both of Corbyn’s leadership campaigns and Momentum activism demonstrate a level of influence over events in British politics young people have not had for some time (see also [38]). It should be noted that such activism is also a much more “high cost” form of political participation than simply voting. Sloam and Ehsan highlight how Labour’s (and specifically Corbyn’s) social media reach was larger, and more “attractive” and “interactive” than that of other parties, something they give credit to Momentum for “pioneering” [28] (p. 21; see also [19,39]). Indeed, in recent years, social media has been seen by many as a key tool both for young people to engage in a non-traditional form of political participation and for political actors to interact with them, and there have been a number of academic writings on the possibilities for political participation opened up by advances in communications technologies (e.g., [40,41,42,43]).

Sloam and Ehsan [28] (pp. 21,22) also highlight how Momentum combined online interactions with physical meet-ups and campaigning, something they believe to be particularly effective. Momentum initiatives such as “My Nearest Marginal” aimed to unseat Conservative MP’s with slim majorities and involved significant social media mobilising of young people, at a time when the official Labour machinery was focused on a very defensive campaign. In his book Rise [36] (pp. 34–40), Young highlights the “organic” and “grassroots” nature of the Labour social media campaign, which was reaching far more voters than that of the Conservatives despite being outspent considerably by them and he highlights, in particular, the over-representation of young people in spreading this digital content. In addition, the previously mentioned attendance of large numbers of young people at Corbyn rallies and the engagement Corbyn garnered from significant figures in youth culture should not simply be dismissed because they do not prove that young people’s electoral turnout increased; rather, these need to be viewed as significant acts of political engagement in themselves.

Moreover, developments in British politics since the 2017 election should not be ignored either, in particular, the wave of industrial action that has hit university campuses across the country in the University and College Union (UCU) dispute with Universities UK over the USS pension scheme. Of particular interest here is the near-unprecedented level of student-staff solidarity shown during the strikes, with more than 20 universities also seeing student occupations, and many more seeing students out on the picket lines with their staff—a level of activism not seen since the 2010 introduction of tuition fees. All of this has been over an issue that would not obviously have mobilised students. This underlines a wider point: rarely do political engagement surveys ask much, if anything, about young people’s involvement in student politics specifically, whether it be with the NUS nationally, UCU or their local students’ union. However, for many students, students’ unions can be a key institution in developing a political awareness and skillset and putting these skills into practice. To leave these spheres of political life out of the vast bulk of research in the field to date is to ignore a huge amount of relevant data about young people’s political views, development and activity. The recent wave of protests by striking schoolchildren over inaction on climate change is another example of young people clearly showing an interest in, and commitment to, political issues but expressing their views on them in ways not reliant on formal political institutions.

In our view, it is unfortunate to say the least that the BES team sought to highlight in their outputs, including a piece for the BBC [44]—which were widely reported in the media—their attempt to debunk the claim that youth (for them, 18–24-years-old) electoral turnout significantly increased in the 2017 general election, which is actually the weakest and therefore least persuasive aspect of their analysis. Moreover, the BES report was erroneously, and perhaps inevitably, seized upon by some (e.g., Fox [45]) as evidence of young people’s (continued) political apathy, whereas, in fact, it is the notion of young people as politically apathetic that ought to be accorded mythical status (see also [29] p. 8).

Youth politics has often been viewed through a distorted lens of conformity that has overlooked actually existing youth engagement, expecting young people to unquestioningly engage with formal institutions, whatever they are offering them, rather than opening up new ways of doing politics themselves. A preoccupation with formal turnout numbers risks us repeating this error and missing the bigger picture. Young people are often portrayed as “apathetic” or “disengaged” by political commentators and academics for not fitting the groove of well-established political behaviours (see e.g., Fahmy [46] and O’Toole, Marsh and Jones [47] for perspectives that challenge this viewpoint). Fahmy argues that this can be linked to wider narratives that view “delinquent” youths in a negative, moralising light and suggests that dismissing alternative forms of engagement can lead to the dangerous position of legitimising certain political acts (centred on the state), but not others [46]. It is not just its caricature of young people in which this narrative is problematic: it can also narrow political debate, behaviour and potential, approving some forms of engagement whilst rejecting others. Whilst this “apathetic” narrative often lingers on in political discourse (e.g., Fox [48]), and can surface in academic work where engagement is perhaps not always thought about deeply enough, there is a strand of research into youth political participation that looks past simplistic understandings of such engagement.

Henn and Foard, for example, found that young people generally value democracy and elections, but that they are sceptical of what is actually done as a result of these processes [49]. This extends to a deep scepticism about politicians and political parties and a lack of faith in their own knowledge of politics. Crucially, however, the authors argue that, far from feeling apathetic about politics, young people appear to be “serious and discerning (sceptical) observer-participants of the electoral process, rather than merely uninterested and apathetic onlookers” [49] (p. 57). Marsh, O’Toole and Jones [50] posit youth engagement within the theory of “everyday makers” [51], whereby citizens disillusioned with the state turn to “DIY politics” and local community activism, with a lack of faith in government leading to political action (albeit in forms that will often be missed by academic measures), not complete withdrawal or apathy. Sloam and Henn [32] argue that young people have maintained an interest in political issues throughout the past few decades, but have increasingly switched to single issue campaigning and are attracted to grassroots activist groups more open to influence, as opposed to more rigid, hierarchical traditional political institutions such as parties and unions (for a wider discussion of what might be driving some of these changing preferences and behaviours, see Allsop, Briggs and Kisby [52]). Where they are engaging with political parties, these are newer, more radical ones. Sloam and Henn discuss this in relation to the Labour Party, an old, traditional party, but one that has taken a more radical stance on social and economic issues in recent years, and a more grassroots approach to campaigning, potentially helping to explain its renewed appeal to younger people [32]. In short, whilst, in recent years, studies in youth political engagement have shown promising signs of developing a more holistic understanding of both political behaviour and youth culture, the problem political engagement as a field of study still has is that many of its measures and approaches were developed with a focus on formal political institutions that no longer (if they ever did) hold a monopoly on legitimate avenues of political change. Without correcting this, we risk mistaking different forms of engagement for no engagement at all.

Whilst young people may not engage with formal political institutions to the same extent as older generations, they are still interested in politics and do at times find alternative outlets for political engagement and expression. This itself, as we have seen, might be changing to some extent, with the possibility of Corbyn’s leadership re-engaging young people in parliamentary politics but we cannot afford to study either type of political engagement in isolation and then draw generalised conclusions about overall engagement. There needs to be a shift in how we conceptualise and measure political engagement, particularly for young people, and an appreciation of the longer-term trends that are shaping and changing their engagement patterns, being prepared to learn from these and understand their logic, rather than automatically assume engaging with traditional political institutions is the only preferable or relevant option. In particular, there are several types of behaviour that we should be including as standard in youth engagement measures, such as: digital forms of engagement, including social media activism; involvement with political organisations not rooted in Westminster party politics; trade and students’ union participation and more spontaneous, grassroots actions, e.g. the climate change school strikes. If researchers wish to study some of these activities in isolation, they can, of course, do valid, important research, but we need to be clear that any findings cannot tell us about youth political engagement in its entirety, only the particular aspect studied. Missing this nuance is a significant problem within academia, as well as the corridors of Westminster. This is not a problem confined to the UK either; several western democracies have seen a decline in formal political engagement, particularly amongst younger generations, although the data suggest that this is a trend most pronounced in the UK [32]. Many of these countries have also seen the emergence of more radical politicians and politics in recent years, rather similar to the Corbyn movement in Britain. Understanding how young people have responded to these events, in a country that has been particularly marked by these trends, can be useful for countries on a similar trajectory.

5. Conclusions: Beyond the Youthquake Debate

Young people in the UK and other advanced industrial democracies have in recent years faced a difficult environment characterised by austerity and spending cuts in welfare and public services. In Britain, many young people are facing a future of substantial student debt, limited job opportunities, modest and stagnating wages, and increasingly unaffordable housing costs. In this context, it should perhaps come as no surprise that they have felt ignored and marginalised and have thereby disengaged from formal electoral politics over time [53]. Youth voter turnout has long given academics and politicians cause for concern, falling faster than the general population’s declining turnout, with less than half of 18–24-year-olds having voted in the four general elections prior to 2017 [54]. However, this article has argued that the BES team have not provided compelling evidence that turnout did not significantly increase among the youngest group of voters in the 2017 general election and therefore the possibility that there was a significant increase in 18–24-year-old turnout cannot be ruled out. Moreover, if “young” is not defined as coming to a sudden end at age 25, then there is good evidence that there was a significant increase in turnout for young people, more widely defined. This article has argued further that there is evidence of continued engagement with politics via other means throughout the years of declining voting amongst young people and that recent years have potentially seen an increase in both types of engagement. The BES team are therefore wrong to dismiss the notion of the youthquake as a myth. Viewed in terms of the high levels of youth activism in Labour’s campaign, young people’s distinctive attitudes on a range of important issues as compared to older generations, their use of social media in political campaigning and their high levels of electoral support for Labour, there clearly have been rather more than just small tremors. The real myth, which unfortunately the BES team reinforce, is that young people are politically apathetic (e.g., Fox [48]). As this article has argued, however, much more persuasive is an anti-apathy paradigm (e.g., Phelps [55]), which holds that, while there is evidence of alienation from formal politics and institutions, young people are engaged with politics, defined more broadly.

That young people were galvanised to vote overwhelmingly for the Labour Party is an important development, potentially beginning to overcome this aversion to traditional politics. Whether Labour can be as successful at attracting the support of younger voters in a future general election, especially given the party leadership’s rather equivocal position on Brexit (to date), remains to be seen. This article has argued, however, that the youthquake is about much more than a potential rise in youth voting in one election, or even short-term shifts in party political behaviour and rhetoric. As it has argued, the evidence suggests that there were and are genuine changes happening in British politics, and in youth politics in particular. However, as this article has also sought to highlight, social science research has difficulties capturing the full diversity of young people’s political participation and needs to do more to embrace qualitative as well as quantitative analyses of this participation. In our view, political engagement measures are problematic in a number of ways. For example, as highlighted above, failing to measure all the activities that could legitimately be seen as political, which can be a particular problem for new, emergent forms of engagement, such as social media activities, that will affect the measurement of youth political engagement disproportionately. Significant work needs to be done in political science, and indeed the social science disciplines more generally, on how to conceptualise and measure political engagement, and to appreciate how this can be different for different people. This should involve conceptual, theoretical, even philosophical work, but also be rooted in the experiences, understandings and actions of young people and other groups whose political engagement is not adequately captured by current methods.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed to the analysis within the article and drafted the manuscript.

Funding

This article draws on research funded by the University of Lincoln.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hugh Bochel and Steve McKay, and also the journal reviewers, for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, accepting, of course, that responsibility is theirs alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Prosser, C.; Fieldhouse, E.; Green, J.; Mellon, J.; Evans, G. Tremors but no Youthquake: Measuring Changes in the Age and Turnout Gradients at the 2015 and 2017 British General Elections. 2018. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3111839 (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Collins, P. Jeremy Corbyn: The Politician Who Never Grew Up. Prospect. 2016. Available online: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/magazine/jeremy-corbyn-the-politician-who-never-grew-up (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Rentoul, J. I Was Wrong about Jeremy Corbyn. The Independent. 2017. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/i-was-wrong-about-jeremy-corbyn-a7781726.html (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Toynbee, P. Let’s Whoop at the Failure of May’s Miserabilism. Optimism Trumped Austerity. The Guardian. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/jun/09/theresa-may-elections-fail (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- BBC. Election. 2017. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election/2017/results (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Travis, A. The Youth for Today: How the 2017 Election Changed the Political Landscape. The Guardian. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/jun/09/corbyn-may-young-voters-labour-surge (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Oxford Dictionaries. Word of the Year 2017 Is…. 2017. Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/word-of-the-year/word-of-the-year-2017 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Lammy, D. 72% Turnout for 18–25 Year Olds. Big up Yourselves @DavidLammy, 8 June, 11:23 pm Tweet. 2017. Available online: https://twitter.com/davidlammy/status/873063062483357696?lang=en (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Britton, L. Here’s the NME Exit Poll of How Young People Voted in 2017 General Election. 2017. Available online: http://www.nme.com/news/nme-exit-poll-young-voters-2017-general-election-2086012 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Skinner, G.; Mortimore, R. How Britain Voted in the 2017 Election. 2017. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/how-britain-voted-2017-election (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Whiteley, P.; Clarke, H. Understanding Labour’s ‘Youthquake’. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/understanding-labours-youthquake-80333 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Heath, O.; Goodwin, M. The 2017 General Election, Brexit and the Return to Two-Party Politics: An Aggregate-Level Analysis of the Result. Political Q. 2017, 88, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. General Election 2017: How Many People are Registering to Vote? Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2017-39837917 (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Weale, S. Voter Registration Soars among Students with 55% Backing Labour. The Guardian. 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/may/04/voter-registration-soars-students-backing-labour-corbyn-general-election (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Curtis, C. How Britain Voted at the 2017 General Election. 2017. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/news/2017/06/13/how-britain-voted-2017-general-election/ (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- BBC. Election. 2015. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election/2015/results (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- BBC. The Andrew Marr Show. 2017. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p055l6s4 (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Hansard, H.C. 2017, 626, 8. Available online: https://hansard.parliament.uk/ (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Fletcher, R. Labour’s Social Media Campaign: More Posts, More Video, and More Interaction. In UK Election Analysis 2017; Thorson, E., Jackson, D., Lilleker, D., Eds.; CSJCC: Poole, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan, P. How Grime Music Fell in Love with Jeremy Corbyn. New Statesman. 2017. Available online: https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/music-theatre/2017/08/how-grime-music-fell-love-jeremy-corbyn (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Savage, M. Glastonbury: Jeremy Corbyn ‘Inspired’ By Young Voters. 2017. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-40394095 (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Prosser, C.; Fieldhouse, E.; Green, J.; Mellon, J.; Evans, G. The Myth of the 2017 ‘Youthquake’ Election. 2018. Available online: http://www.britishelectionstudy.com/bes-impact/the-myth-of-the-2017-youthquake-election/#.WvMBmogvzIU (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Prosser, C.; Fieldhouse, E.; Green, J.; Mellon, J.; Evans, G. Youthquake—A Reply to Our Critics. 2018. Available online: http://www.britishelectionstudy.com/bes-impact/youthquake-a-reply-to-our-critics/#.WvKwgIgvzIV (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Curtice, J.; Simpson, I. Why Turnout Increased in the 2017 General Election. British Social Attitudes. 2018. Available online: http://www.natcen.ac.uk/media/1570351/Why-Turnout-Increased-In-The-2017-General-Election.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2018).

- Kellner, P. The British Election Study Claims There Was No “Youthquake” Last June. It’s Wrong. Prospect. 2018. Available online: https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/blogs/peter-kellner/the-british-election-study-claims-there-was-no-youthquake-last-june-its-wrong (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Stewart, M.; Clarke, H.; Goodwin, M.; Whiteley, P. Yes, There Was A “Youthquake” in the 2017 Snap Election—And It Mattered. New Statesman. 2018. Available online: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/staggers/2018/02/yes-there-was-youthquake-2017-snap-election-and-it-mattered (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Scott, P. A Million Young People Register to Vote in Month Since Election Called. The Daily Telegraph. 2017. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/05/19/important-young-people-vote/ (accessed on 17 May 2018).

- Sloam, J.; Ehsan, R. Youth Quake: Young People and the 2017 General Election; Intergenerational Foundation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sloam, J.; Ehsan, R.; Henn, M. ‘Youthquake’: How and Why Young People Reshaped the Political Landscape in 2017. Political Insight 2018, 9, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A. Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgis, P.; Jennings, W. Why 2017 May Have Witnessed a Youthquake after All. LSE Blog. 2018. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/was-there-a-youthquake-after-all/ (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Sloam, J.; Henn, M. Youthquake 2017: The Rise of Young Cosmopolitans in Britain; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, S. Politics, Protest and Young People: Political Participation and Dissent in 21st Century Britain; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, C. Political Analysis: A Critical Introduction; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Audickas, L.; Dempsey, N.; Keen, R. Membership of UK Political Parties; briefing paper, number SN05125; House of Commons: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Young, L. Rise: How Jeremy Corbyn Inspired the Young to Create a New Socialism; Simon & Schuster: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pickard, S. Momentum and the Movementist ‘Corbynistas’: Young People Regenerating the Labour Party in Britain. In Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crisis; Pickard, S., Bessant, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, B. Young Voters Are on the March—Here’s How to Keep Them Coming Back for More. The Conversation. 2017. Available online: http://theconversation.com/young-voters-are-on-the-march-heres-how-to-keep-them-coming-back-for-more-84748 (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- Lilleker, D. Like me, share me: The People’s Social Media Campaign. In UK Election Analysis 2017; Thorson, E., Jackson, D., Lilleker, D., Eds.; CSJCC: Poole, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Boulianne, S. Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2015, 18, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, P. Young Citizens and Political Participation in a Digital Society; Palgrave: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Loader, B. Young Citizens in the Digital Age: Political Engagement, Young People and New Media; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Xenos, M.; Vromen, A.; Loader, B. The Great Equalizer? Patterns of Social Media Use and Youth Political Engagement in Three Advanced Democracies. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2014, 17, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosser, C.; Fieldhouse, E.; Green, J.; Mellon, J.; Evans, G. The Myth of the 2017 ‘Youthquake’ Election. 2018. Available online: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-42747342 (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- Fox, S. The ‘Youthquake’ Myth & Britain’s Millennials. 2018. Available online: https://wiserd.ac.uk/news/youthquake-myth-britains-millennials (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Fahmy, E. Young Citizens: Young People’s Involvement in Politics and Decision Making; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole, T.; Marsh, D.; Jones, S. Political Literacy Cuts Both Ways: The Politics of Non-Participation Among Young People. Political Q. 2003, 74, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. Apathy, Alienation and Young People: The Political Engagement of British Millennials. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, M.; Foard, N. Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain. Parliam. Aff. 2012, 65, 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D.; O’Toole, T.; Jones, S. Young People and Politics in the UK: Apathy or Alienation; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, H. Among Everyday Makers and Expert Citizens. In Remaking Governance: Peoples, Politics and the Public Sphere; Newman, J., Ed.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Allsop, B.; Briggs, J.; Kisby, B. Market Values and Youth Political Engagement in the UK: Towards an Agenda for Exploring the Psychological Impacts of Neo-Liberalism. Societies 2018, 8, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, M.; Oldfield, B. Cajoling or Coercing: Would Electoral Engineering Resolve the Young Citizen-State Disconnect? J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 1259–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipsos MORI. How the Voters Voted. 2017. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/how-voters-voted (accessed on 19 June 2018).

- Phelps, E. Understanding Electoral Turnout among British Young People: A Review of the Literature. Parliam. Aff. 2012, 65, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).