The Convergence and Mainstreaming of Integrated Home Technologies for People with Disability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Perspectives on Disability Underlying Research into Integrated Home Technologies

3. Framework for Understanding Functioning and Technology as Environmental Factors

4. Environmental Interventions as Part of Rehabilitation

5. Common Terms and Definitions for Assistive Technology

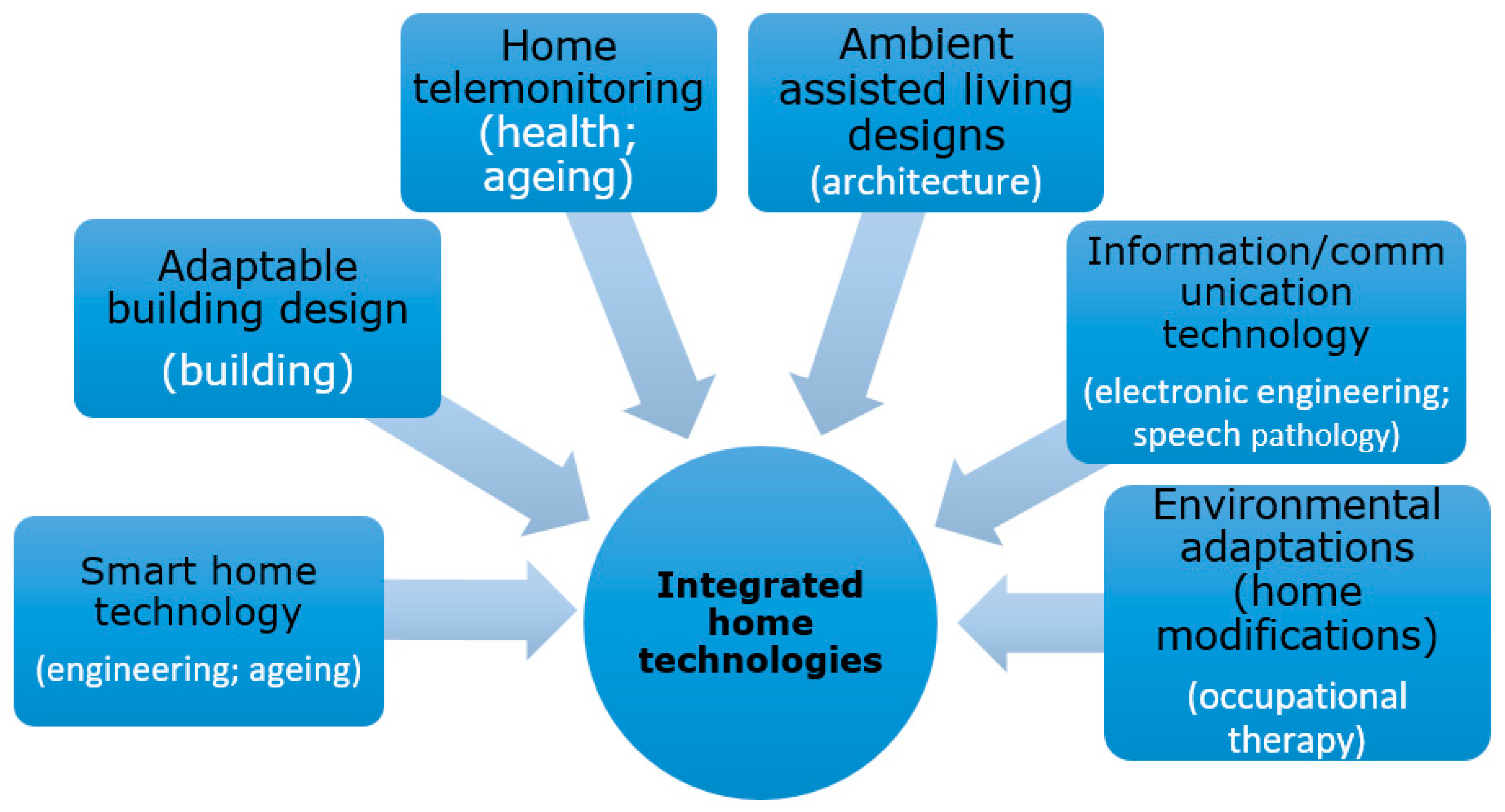

6. Interconnectivity between Technologies and Environments

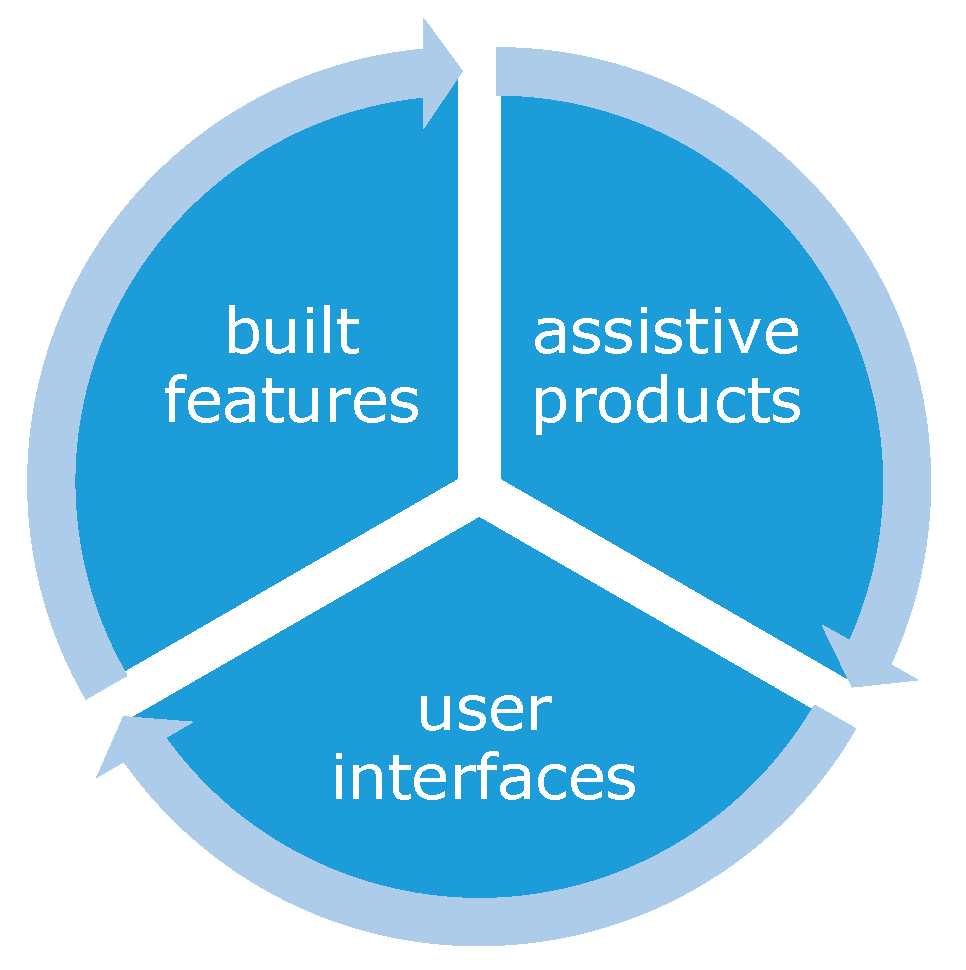

7. Convergence of Assistive Technologies in Smart Homes

8. Mainstreaming Inclusive Design

- adaptable (configurable in such a way to tailor to individual user’s requirements)

- adaptive (automatically adapting to the user’s preferences),

- based on more flexible architectures (mobile and ubiquitous computing, with applications that can be downloaded from the “cloud”) [47] (p. 10).

9. Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shakespeare, T. Disability: Suffering, Social Oppression, or Complex Predicament? In The Contingent Nature of Life: Bioethics and Limits of Human Existence; Rehmann-Sutter, C., Mieth, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the aging process. In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.O., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Cooper, B.; Strong, S.; Stewart, D.; Rigby, P.; Letts, L. The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 1996, 63, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M. The environment: A focus for occupational therapy. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 58, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, S.; Kelly, G.; Kernohan, W.; McCreight, B.; Nugent, C. Smart home technologies for health and social care support. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, CD006412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, J.; Hayes, J. Self-determination and Empowerment: A Feminist Standpoint Analysis of Talk about Disability. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2000, 28, 671–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, B.; Hearn, J. Researching others: Epistemology, experience, standpoints and participation. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2004, 7, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Situated Knowledges. In The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader; Harding, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hekman, S. Truth and Method. In The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader; Harding, S., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, P.; Freas, D.; Maislin, G.; Stineman, M. Recovery from Disablement: What functional abilities do rehabilitation professionals value the most? Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 1600–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schraner, I.; de Jonge, D.; Layton, N.; Bringolf, J.; Molenda, A. Using the ICF in Economic Analyses of Assistive Technology Systems: Methodological Implications of a User Standpoint. Disabil. Rehabil. 2008, 30, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K. Introducing the 3rd Era of Care, and 7 Waves of TLC Applications; i-CUHTec: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frontera, W.; Bean, J.; Damiano, D.; Fried-Oken, M.; Jette, A.; Jung, R.; Lieber, R.; Malec, J.; Mueller, M.; O’ttenbacher, K.; et al. Rehabilitation Research at the National Institutes of Health: Moving the Field Forward (Executive Summary). Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiris, G.; Thompson, H. Smart homes and ambient assisted living applications: From data to knowledge- empowering or overwhelming older adults? Contribution of the IMIA Smart Homes and Ambient Assisted Living Working Group. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2011, 6, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson, A.; Hartung, R. An infrastructure for individualised and intelligent decision-making and negotiation in cyber-physical systems. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 35, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare, T.; Watson, N. Beyond models: Understanding the complexity of disabled people’s lives. In New Directions in the Sociology of Chronic and Disabling Conditions: Assaults on the Lifeworld; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lenker, J.; Harris, F.; Taugher, M.; Smith, R. Consumer perspectives on assistive technology outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2013, 8, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanov, D.; Bien, Z.; Bang, W. The smart house for older persons and persons with physical disabilities: Structure, technology arrangements, and perspectives. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2004, 2, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.; Campo, E.; Estève, D.; Fourniols, J.Y. Smart homes—Current features and future perspectives. Maturitas 2009, 64, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerniauskaite, M.; Quintas, R.; Boldt, C.; Raggi, A.; Cieza, A.; Bickenbach, J.E.; Leonardi, M. Systematic literature review on ICF from 2001 to 2009: Its use, implementation and operationalization. Disabil. Rehabil. 2011, 33, 281–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementing the Social Model of Disability: Theory and Research; Barnes, C., Mercer, G., Eds.; The Disability Press: Leeds, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, M.; Derosiers, J.; St-Cyr, D.T. Comparing the Disability Creation Process and International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Models. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2007, 74, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerkens, Y.F.; de Weerd, M.; Huber, M.; de Brouwer, C.P.M.; van der Veen, S.; Perenboom, R.J.M.; van Gool, C.H.; ten Napel, H.; van Bon-Martens, M.; Stallinga, H.A.; et al. Reconsideration of the scheme of the international classification of functioning, disability and health: Incentives from the Netherlands for a global debate. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letts, L.; Rigby, P.; Stewart, D. Using Environments to Enable Occupational Performance; SLACK Incorporated: Thorofare, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.; Gould, M.; Bickenbach, J. Environmental barriers and disability. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2003, 20, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E. Advancing Universal Design. In The State of the Science in Universal Design: Emerging Research and Developments; Maisel, J.L., Ed.; Bentham Sciences Publishers, State University of New York at Buffalo: Buffalo, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Darrah, J.; Law, M.C.; Pollock, N.; Wilson, B.; Russell, D.J.; Walter, S.D.; Rosenbaum, P.; Galuppi, B. Context therapy: A new intervention approach for children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2011, 53, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.; Law, M.; Coster, W.; Bedell, G.; Khetani, M.; Avery, L.; Teplicky, R. The Mediating Role of the Environment in Explaining Participation of Children and Youth with and without Disabilities Across Home, School, and Community. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, J.A. Design for the Ages: Universal Design as A Rehabilitation Strategy; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yuginovich, T.; Soar, J.; Su, Y. Impact analysis of Smart Assistive Technologies for people with dementia. In Proceedings of the COINFO, Information Sharing in the Cloud, Nanjing, China, 23–25 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rehabilitation International’s Position Paper on the Right to [Re]Habilitation. Available online: www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/ahc3ri.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- World Health Organization; World Bank. The World Report on Disability; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, S.; Elsaesser, L.; Scherer, M.; Sax, C. Promoting a standard for assistive technology service delivery. Technol. Disabil. 2014, 26, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Health Assembly Resolution on Health Technologies (WHA60.29). Available online: www.who.int/medical_devices/resolution_wha60_29-en1.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 July 2019).

- Elsaesser, L.-J.; Bauer, S. Provision of assistive technology services method (ATSM) according to evidence-based information and knowledge management. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steel, E.J.; Layton, N.A. Assistive Technology in Australia: Integrating theory and evidence into action. Aust Occup Ther J. 2016, 63, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, M.A.; Johnson, M.A. On modelling assistive technology systems—Part 1: Modelling framework. Technol. Disabil. 2008, 20, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.M.; Polgar, J.M. Chapter 1—Principles of Assistive Technology: Introducing the Human Activity Assistive Technology Model. In Assistive Technologies, 4th ed.; Cook, A.M., Polgar, J.M., Eds.; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Government Publishing Office. Assistive Technology Act of 1998. United States Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- FOLDOC Online Dictionary. Available online: foldoc.org/ (accessed on 20 May 2019).

- Gentry, T. Smart homes for people with neurological disability: State of the art. Neurorehabilitation 2009, 25, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Demiris, G.; Thompson, H.J. Ethical considerations regarding the use of smart home technologies for older adults: An integrative review. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2016, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeder, B.; Meyer, E.; Lazar, A.; Chaudhuri, S.; Thompson, H.J.; Demiris, G. Framing the evidence for health smart homes and home-based consumer health technologies as a public health intervention for independent aging: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimarlund, V.; Wass, S. Big Data, Smart Homes and Ambient Assisted Living. Imia Yearb. 2014, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAATE. Service Delivery Systems for Assistive Technology in Europe—Position Paper; AAATE: Linz, Austria, 2012; Available online: https://aaate.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2016/02/ATServiceDelivery_PositionPaper.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2019).

- Braun, A.; Wichert, R.; Kuijper, A.; Fellner, D. Benchmarking sensors in smart environments—Method and use cases. J. Amb. Intel. Smart. En. 2016, 8, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Policy on Ageing. The Potential Impact of New Technologies; Centre for Policy on Ageing—Rapid review: London, UK, July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Labonnote, N.; Høyland, K. Smart home technologies that support independent living: Challenges and opportunities for the building industry—A systematic mapping study. Intell. Build. Int. 2015, 9, 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croser, R.; Garrett, R.; Seeger, B.; Davies, P. Effectiveness of electronic aids to daily living: Increased independence and decreased frustration. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2001, 48, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, M.; Maye, F. Enhancing occupational performance in the virtual context using smart technology. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 79, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myburg, M.; Allan, E.; Nalder, E.; Schuurs, S.; Amsters, D. Environmental control systems—The experiences of people with spinal cord injury and the implications for prescribers. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Cassim, J.; Coleman, R. Addressing the Challenges of Inclusive Design: A Case Study Approach. In Universal Access in Ambient Intelligence Environments; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Casacuberta, J.; Sainz, F. Evaluation of an Inclusive Smart Home Technology System. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Ambient Assisted Living and Home Care, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2–5 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Rau, P.; Salvendy, G. Design and evaluation of smart home user interface: Effects of age, tasks and intelligence level. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2009, 28, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewsbury, G.; Clarke, K.; Rouncefield, M.; Sommerville, I.; Taylor, B.; Edge, M. Designing acceptable ‘smart’ home technology to support people in the home. Technol. Disabil. 2003, 15, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, D.; Walker, G. Beyond adaptation: Getting smarter with assistive technology. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2014, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, K.; Goggin, G.; Kent, M. Disability’s digital frictions: Activism, technology, and politics. Fibreculture J. 2015, 26, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. ISO 9999 Assistive Products for People with Disability—Classification and Terminology; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Assistive Technology (AT) | “…inclusive of products, environmental modifications, services, and processes that enable access to and use of these products, specifically by persons with disabilities and older adults” [39] cited on page 3 of [40]. |

| Technology designed to be utilized in an assistive technology device or assistive technology service. Section 3(3) of the Assistive Technology Act) [41]. | |

| Assistive Products (or AT Devices) | Assistive products include especially produced or generally available devices, equipment, instruments, or software used by or for persons with disability

|

| Assistive Technology Services | Any service that directly assists an individual with a disability in the selection, acquisition, or use of an assistive technology device [41]. |

| Electronic Assistive Technology (EAT) | Refers to a broad range of devices. All electronic assistive technologies use information and communication technology (ICT) as a core component, generating dynamic, often intelligent devices capable of invoking a response following an action by a user. In addition, integration of a networked ICT infrastructure facilitates device communication, widening functional capability and capacity [6]. |

| Information and Communications Technology (ICT) | Extended term for information technology (IT) that stresses the role of unified communications and the integration of telecommunications (telephone lines and wireless signals), computers, as well as necessary enterprise software, middleware, storage, and audio-visual systems, which enable users to access, store, transmit, and manipulate information [42]. |

| Smart Home Technology (SHT) | Any technology that automates a home-based activity [43]. |

| A smart home is viewed as a holistic and centrally controlled environment that enables interpretation of resident health needs and proactively responds to changes in health [44]. | |

| Personal living spaces of older adults with embedded sensor technologies to promote independence and wellness are termed smart homes [45]. | |

| Smart houses include devices that have automatic functions and systems that can be remotely controlled by the user to enhance comfort, energy saving, and security for the residents of the house [19]. | |

| A residential setting equipped with a set of advanced electronics, sensors, and automated devices specifically designed for care delivery, remote monitoring, early detection of problems or emergency cases, and promotion of residential safety and quality of life [46]. | |

| Smart Home and Ambient Assisted Living (SHAAL) | Systems utilize advanced and ubiquitous technologies, including sensors and other devices that are integrated in the residential infrastructure or are wearable, to capture data describing activities of daily living and health-related events [46]. |

| Ambient Assisted Living | Use of information and communication technologies to augment the life environment and make it “smarter” (more adaptable, adaptive) for everybody [47]. |

| Environmental Adaptations | Also termed home modifications or environmental interventions, refers to the alteration of aspects of environment(s) to facilitate access and outcomes for individuals and groups [26]. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Layton, N.; Steel, E. The Convergence and Mainstreaming of Integrated Home Technologies for People with Disability. Societies 2019, 9, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9040069

Layton N, Steel E. The Convergence and Mainstreaming of Integrated Home Technologies for People with Disability. Societies. 2019; 9(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleLayton, Natasha, and Emily Steel. 2019. "The Convergence and Mainstreaming of Integrated Home Technologies for People with Disability" Societies 9, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9040069

APA StyleLayton, N., & Steel, E. (2019). The Convergence and Mainstreaming of Integrated Home Technologies for People with Disability. Societies, 9(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9040069