Abstract

This study examines the relationships between extractive industries, power and patriarchy, raising attention to the negative social and environmental impacts these relationships have had on communities globally. Wealth accumulation, gender and environment inequality have occurred for decades or more as a result of patriarchal structures, controlled by the few in power. The multiple indirect ways these concepts have evolved to function in modern day societies further complicates attempts to resolve them and transform the social and natural world towards a more sustainable model. Partly relying on queer ecology, this paper opens space for uncovering some hidden mechanisms of asserting power and patriarchal methods of domination in resource-extractive industries and impacted populations. I hypothesize that patriarchy and gender inequality have a substantial impact on power relations and control of resources, in particular within the energy industry. Based on examples from the literature used to illustrate these processes, patriarchy-imposed gender relations are embedded in communities with large resource extraction industries and have a substantial impact on power relations, especially relative to wealth accumulation. The paper ends with a call for researchers to consider these issues more deeply and conceptually in the development of case studies and empirical analysis.

1. Introduction

The energy industry, being one of the biggest natural resources extraction industries as well as one of the biggest greenhouse gas emitting industries, offers an interesting context for the study of power and patriarchy in contemporary societies. Research on energy development and extractive industries remains largely gender neutral, which creates a gap in understanding such relations within this large sector [1]. The purpose of this paper is to investigate power relations and specifically to uncover gender dynamics relative to resource distribution/extraction and wealth accumulation. Moreover, I aim to discuss how the exploitation of natural resources is embedded in patriarchal power and its structural and relational implications.

Power as a concept has several conceptual and operational definitions with two main discourse distinctions: power over and power to. Power over refers to power as domination, where one side is deemed superior to another and has a greater impact/influence, whereas power to refers to empowerment and enabling others [2,3]. Power is a complex concept with several layers, dimensions and interpretations, and is not simply bound by the binary nature of power to and power over. Other types of power are briefly discussed later on for a more comprehensive view. For the purposes of this paper, power is discussed from the “power over” lens, drawing on the literature and relating such complex dynamics to control over energy resources and wealth. The main questions I address in this paper are:

- -

- What are the key connections between power, patriarchy and resource extraction?

- -

- Drawing from case studies in two countries, what are the contours of patriarchy, gender dynamics and resource extraction?

The main hypothesis is that patriarchy and gender inequality have a substantial impact on power relations and control of resources, in particular within the energy industry. Through relying on some theoretical components of queer ecology, I argue that patriarchy-imposed gender relations are embedded in communities with large resource extraction industries and have a substantial impact on power relations, especially relative to wealth accumulation. I refer to two brief and contrasting examples addressing the same questions on different scales (country-wide vs. city-specific) to demonstrate the diversity of dynamics, general impacts and intricate details.

Adopting a queer ecology lens on the main questions being asked here allows for a rather novel theoretical approach which is based on well-established foundational theories such as ecofeminism [4]. It can be considered an advanced conceptualization of ecofeminism since queer ecology unpacks relationships between sex/gender, nature and environmental politics [5]. Two of the main basic principles of queer ecology that lend themselves to this paper are its non-hierarchical intersectionality and the rejection of dualisms [6,7]. Expanding on this notion and the suitability of applying queer ecology to research in this intersecting area of power, patriarchy and natural resources, Bauhardt [7] (p. 371) states:

“Queer ecologies enable us to suspend natural materiality and social reproduction from the female body. The concept of ‘naturecultures’ allows an understanding of human life embedded in material and discursive processes—without putting the potential (re)productivity of the female body on the ideological pedestal of heterosexual maternity. In my view, feminist-ecological politics can draw upon these strands of thinking to develop for fresh perspectives. Global environmental policies should also be able to expect many more insights from feminist enquiry than the natural resource management approach allows today.”

Bauhardt [7] presents a compelling argument for queer ecology and highlights its relevance to this paper. An example of the importance of this perspective is the concept of “naturecultures”, quoted above, that utilizes queer ecology’s attention to discourse and language [6]. Naturecultures represents the idea of rejecting dualisms and, to a certain extent, hierarchies as it unifies both terms, demonstrating the problematic nature of attempting to separate them in theory and in practice due to their interlinked “nature”. Accordingly, unpacking gender inequality and injustice reflected in power relations and the undermining (and overmining) of the more-than-human world requires an unconventional perspective that denies domination within these relationships. As will be elaborated on below, power, patriarchy and the exploitation of nature have webbed, intersectional links that are embedded in our societies. Acknowledging this is the first step towards reverting as much damage as possible and working towards a sustainable future.

1.1. What Is Power?

Power, or power relations as a concept, is often mentioned amongst researchers, informally in passing conversations, but is rarely discussed and theoretically applied. Hence, it is essential to clarify the context from which the term will be applied in this paper prior to establishing the scholarly definition of it [8]. Power relations is discussed from a social context, relative to political structures, resource control, and decision-making processes. Generally speaking, power implies some superiority of one side over another, with most decisions being made on the superior end and strictly enforced [9]. As mentioned earlier, it is important to make the distinction between power as domination, referred to in the literature as power over, and power as in empowerment, which is referred to as power to [3,8,10]. I focus on the former understanding of power as domination; however, the complexity of this relationship extends well beyond that, hence the dire need for uncovering it both conceptually and operationally. A major critique of this generalized and rather common idea of power is that it represents just one dimension and overlooks sophisticated interactions [2]. Lukes [11] delves into the dimensionality of power and its complex dynamics as reflected in everyday life through various forms and mechanisms. One of the most controversial aspects of power is the cause and effect relationship where potential outcomes of certain “power” moves/decisions are not directly traceable or clearly linked. It is important to acknowledge the fact that “... power works in various forms and has various expressions that cannot be captured by a single formulation.” [2] (p. 41). The objectives of conceptually and operationally defining power in this paper are to answer the following questions: Who has “power over”? How does “power over” develop? What are the impacts of “power over” on societies?

Lukes’ [11] understanding and deconstruction of power and power relations suggests the need for innovative and unorthodox methods of analysis to properly situate power where it is visible, invisible, consequential, or non-consequential. Lukes [11] claims that one important dimension of power is unseen and lies in “inaction”. This is manifested in what Lukes [11] refers to as the third dimensional view of power, which is an additional aspect to the two main conventional understandings of power. The first understanding includes the visible or invisible control of one subject over another (one dimensional view), framed as an intentional and active process. The second dimension of power revolves around the contextual influence over decision-making processes, where conflict may both be overt and/or covert and where power indirectly acts to prevent or limit the expression of any opposing views to the main subject of power’s interests and demands (two dimensional view). The third dimensional view of power is regarded as the most advanced and adequate as it demonstrates that “power over” can function apart from individuals. To elaborate, this third dimension occurs when a group of people or individuals attempt to assert their power over others without conflict through transcribing notions of power and control into social ideology and values [9,11,12].

To conceptually place power as a third dimensional agent, it is important to situate it within a framework of understanding. This form of power is one which occurs when A exercises power over B through “significantly” influencing B’s wants and interests according to A’s preferences [11]. In this case, the third dimensional view of power indicates that there is rarely any conflict between those in power and those influenced by power. If we relate this to institutions and corporations, for example, we will find few to no signs of conflict based on values, social structures and systems. Additionally, those who are controlled by aspects of power are rarely consciously aware, or even skeptical of it, since it is based on social and cultural beliefs, some of which are passed down over generations and historically embedded [11,12]. According to Lukes [11], this type of power is also usually observable in collective action and less focused on individuals.

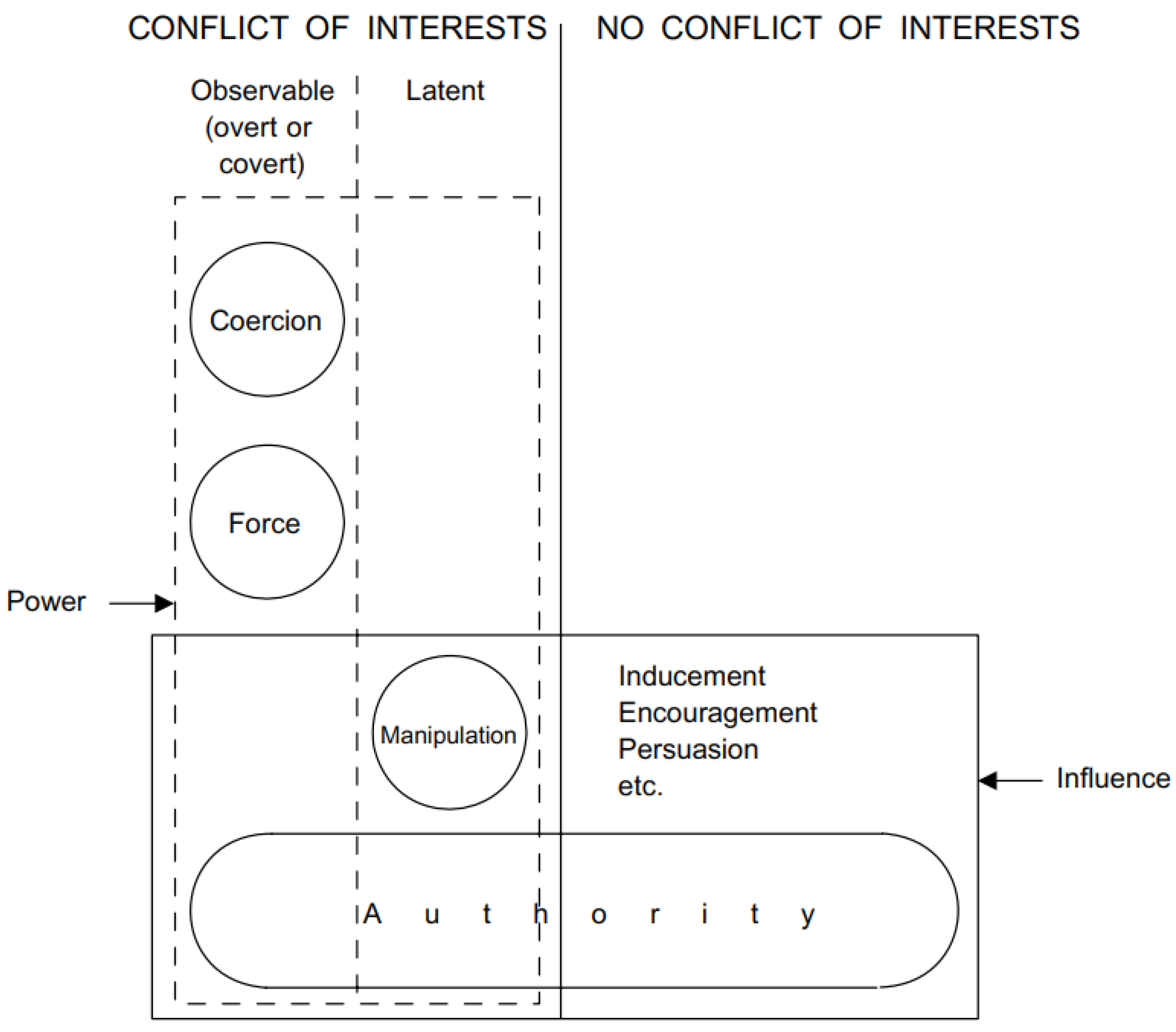

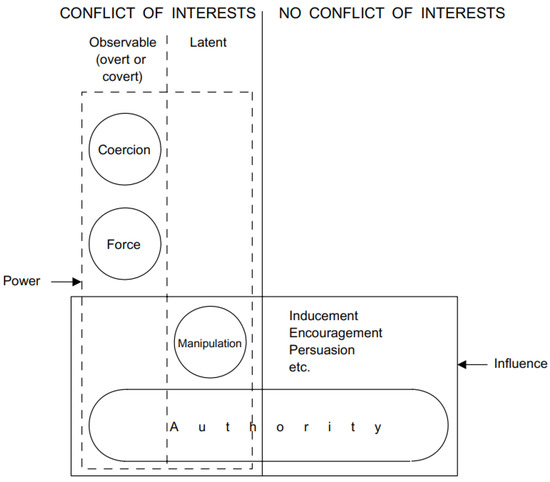

In order to apply this understanding of power to real life examples, it is important to note that social proximity between both sides of power is an essential factor [8]. For example, it may be easier to measure the power of a local government unit on the community, or the power of a local religious group over the community to which it belongs, than it would be to measure the power of one country over another. To expand on this conceptual understanding of power relative to institutions, Figure 1 presents a map of different factors and indicators of power. The figure shows that when power comes into play, conflicts of interest become “latent” and the influence of authorities becomes “manipulation”.

Figure 1.

Conceptual mapping of power as a three-dimensional concept, extracted from Lukes [11] (p. 36).

The next section elaborates on patriarchy, briefly discussing its origins, and relates it to the main topics of this paper—power relations and energy extractive industries. It is essential to note that these are complex, intertwined concepts which comprise a strong network that is hard to deconstruct. Hence, I will rely on brief examples to assess the constituents of these networks and relationships between them and highlight some of the underlying important factors.

1.2. What Is Patriarchy?

The patriarchal system is said to date back to before capitalism, where men dominated women and children within the family [13]. Patriarchy is commonly referred to as a structure or a system that governs social relations pertaining to binary genders within societies [14,15,16]. The main attribute of patriarchal social structures is the domination, oppression and exploitation of women by men [14,16,17]. It is worth noting that these generalized definitions of patriarchy do not adequately explain or address the obscurities and complexities of the term and its application in the social world, historically and currently, which are believed to be some of the reasons behind the sustainability of patriarchy over time [17,18].

It is imperative to fully understand and deconstruct all the elements of patriarchy and the male domination of all other genders, nature and property1 if we are to structurally and operationally dismantle it in the pursuit of equality [17,18]. Reasons behind its infiltration across cultures worldwide are not explicitly agreed upon, yet it is loosely attributed to colonization and the invasion of unclaimed/underprivileged territories [17]. Perhaps attempting to uncover patriarchal relations in the modern day, as discussed in this paper, will shed more light on its emergence and potentially poses a consequent step to this paper. It is perhaps striking, yet not so striking at the same time, that narratives on patriarchy persist in the literature where the same problems that existed decades ago, if not longer, are still discussed up to this day, with little to no progress on transforming the situation for the better or addressing the inequalities within the seemingly endless patriarchal system of this world [16,17,19].

Walby [16] (p. 214) discusses the operationalization of the concept of patriarchy; she states that “patriarchy is composed of six structures: the patriarchal mode of production, patriarchal relations in paid work, patriarchal relations in the state, male violence, patriarchal relations in sexuality, and patriarchal relations in cultural institutions, such as religion, the media and education”. Patriarchy is not derived from capitalism, although these six structures relate to it; it both pre-dates and post-dates capitalism [13,16]. Drastic changes undergone by patriarchy in the wake of capitalism are well acknowledged and do not alter the main argument of this paper, but they do provide a modern lens to be used for analyzing patriarchy relative to capitalism and, in particular, resource extractive industries that may have intensified the six structures mentioned above [16,17].

It is worth noting that this paper takes into consideration discrepancies regarding the definition of patriarchy. It is acknowledged that oppression against women is not seen as equal and experiences of women within patriarchal relations differ greatly across the globe and more specifically within extractive industries. Furthermore, domination of men by other men is also taken into consideration [16,20]. Arguably, one of the main premises of patriarchy was the confinement of women to the home due to the “mothering” claims and biological child bearing, which meant that men were obliged to fulfill the role of paid labor outside the home [13]. Such claims were threatening to the rise of capitalism, which mandated that everyone should work for money; however, the segregation of labor and the insistence on women’s “natural” reproductive role sustained the dominant role of males. This is not to say that there were/are no communities where women and men are seen as equal and patriarchy has no existence (see [13] for examples), but such cases are now considered exceptions. Patriarchy led to the development of hierarchical labor roles, placing women at the bottom of the hierarchy, especially pertaining to wages, forcing women to rely more on men and obliging them to marry men as per the social norms associated with binary genders, perform domestic chores, and so on. Such labor hierarchy and control over resources (financial or natural), will be explored in more detail through empirical examples in order to uncover such dynamics as they play out in modern day communities.

Following the main objectives and goals, this paper theoretically discusses these often-hidden links and relationships—at least as hidden from mainstream literature and media—and the intricacies between them. Subsequently, this paper is not necessarily offering a solution to such institutional and systemic infestations of “power over”, but merely starting the conversation and strengthening the path towards effective transformation, both academically and operationally, through proper framing of these intertwined concepts. Based on the literature and preliminary findings, it is clear that there is an undeniable link between power relations, traditional patriarchal structures, socio-economic inequalities and gender disparities. The impacts of this linkage have been found to take different forms, some more apparent than others. These forms are intricately complex and are difficult to resolve, as they are embedded in capitalistic systems and subsequent large-scale industries of all types. Focusing on extractive industries and the energy sector, we find these complexities reproduced over time and attempts to transform into alternative gender dynamics, social structures and power relations have ultimately failed and did not properly address the underlying problems.

2. Empirical Illustrations

This paper relies on empirical examples in order to analyze, contrast and compare patriarchal structures and power relations relative to extractive industry dependent economies. The two main examples chosen illustrate similar complexities at different scales (country-wide vs. city-specific), adding an element of diversity within the design and scope of inquiry. Using these two examples from the literature also facilitates comparisons of similar violence occurring in North and South America. Findings are analyzed based on the conceptual understandings and factors mentioned earlier. It is worth reiterating at this stage that these relationships and understandings can be found in the literature but need to be given more attention by researchers. This paper demonstrates that, pointing to the importance of accurately framing existing research findings relative to the underlying conceptual relations in order to enhance its applicability and potential reproduction in various contexts around the globe.

The first example is based on Elizabeth Peredo Beltran’s [21] article on the unsuccessful social transformation process in Bolivia, which followed rebellions against neoliberalism, machismo, anti-colonialism and dictatorships. She describes this almost 40-year process as continuing resistance, rebellion and proposal-making, which mainly constituted regulating workers unions and inclusion of their demands as well as respect for human rights, and recognition of indigenous communities. However, this complex transformation process, Beltran [21] claims, was short lived, and rapidly shifted direction towards exacerbating power relations and the economic and wealth gap, and political inclusion. This deterioration in the main plans of social, economic and political change were also intertwined with continued, if not increasing environmental degradation and natural resource abuse. The main insight on the flaws of those who were advocating for change was overlooking power relations, and especially power as it pertains to patriarchy, feminism, nature and ecology, and the diversity of indigenous communities. What seems to have started with the nationalization of the oil and gas industry, evolved to an overall hunger for “power”. Leaders of social movements and trade unions were only concerned with gaining access to positions of power in the government. Although environmental and leftist narratives were dispersed, maximizing “extraction” was well underway on the ground. National development plans revolved around the expropriation of gas and water, ignoring all the rights mentioned earlier, including the sanctity of indigenous lands. The oil and gas sector reached about 69% of GDP while 26% was mining activity [21]. The side effects of this included increasing infrastructure to support the shift towards extractive industry, which involved moving forward with building roads on indigenous lands regardless of previous agreements. The second upheaval, which started as a response to these atrocities in 2011, revealed true identities. The government clearly had no intention to abide by the earlier social movement’s demands and instead continued on the path of economic growth from extractive industries. The president had this response when people were protesting against road construction on indigenous lands:

“If I had time, I’d go and flirt with all the Yuracaré women and convince them not to oppose it [the TIPNIS road]; so, you young men, you have instructions from the President to go and seduce the Yuracaré Trinitaria women so that they don’t oppose the building of the road. Approved?”[21] (p. 6; extracted from Bolivian news website, La Razon, 2011)

Furthermore, another Bolivian news agency, Pagina Siete, reported the following on the country’s National Development Plan 2025:

“The new idea coming from this government is that we’re going to be an energy power. The twenty-first century for Bolivia is to produce oil, industrialise petrochemicals, industrialise minerals.”([21] (p. 7; extracted from Bolivian news website, Pagina Siete, 2015)

This plan is one that clearly contradicts the International Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) recommendations and all energy transition agreements and strategies regarding the mitigation of and adaptation to climate change [21]. Seemingly, what started with an idealistic hope for social transformation and trust in leftist leaders, evolved to become entrapments of power. Patriarchal systems of government remained in place and capitalism was relied on to allegedly achieve socialism. Patriarchy has been reproduced within this system of governance and power relations through violence (specifically against women and others); devaluing the different; erasing diversity in order for male leaders to become real men, cruel, or powerful and decide “what’s best”; limiting/ bypassing any indigenous consultation; and exploiting women and nature [21]. Beltran [21] frames the main problem as capitalism, which is seen to persist due to its ancient connections to systems of oppression such as patriarchy. To address this, she recommends social change that aims at emancipating capitalism and examining the relevant ethical dimensions.

The example of Bolivia demonstrates the complexity of the intertwined capitalism, power and patriarchy, specifically following decisions to shift the country’s economy towards resource extractive industries. Bolivia can be considered a macro-scale case study that shows the overall picture of modern-day inequality and environmental degradation. The next example is representative of a smaller scale and explores the aggravated and exacerbated patriarchy and male thirst for power following the relative growth of the resource extractive industry sector.

The second example provides a practical application of theories regarding extractive industries and patriarchy. Pennsylvania is discussed as a case study where capitalist patriarchy is most prominent due to the local socio-economic weave, especially relative to gender norms and relations. Matthew R. Filteau [1] provides an in-depth discussion of gender hierarchies in a natural-resource based local economy; an area of research which is found to be mostly gender-neutral. What started in 2003 with the first well dug in the Marcellus Shale oil reserve in Pennsylvania rapidly grew and 8200 wells were dug between 2009 and 2015, accompanied with an influx of mostly male laborers to satisfy the demand in what can be considered an early stage of development and extraction [1]. As mentioned, researchers found that towns where there is rapid economic growth, specifically due to the oil and gas industry, pose intriguing research problems due to their deeply troubling social nature (see [22,23,24,25,26]).

During the primary analysis of his qualitative grounded theory approach results, Filteau [1] found similarities amongst his interviewees where business owners, government officials, industry representatives, landowners, and leaders of local organizations—either men or women—demonstrated signs of hegemony, and residents who had high environmental awareness and did not necessarily abide by patriarchal capitalism were found to represent “alternative femininities” and “protest masculinities”. Furthermore, striking factors indirectly or directly conducted by the oil and gas industry that have contributed to the imbalance in power relations and gender dynamics included the following [1]:

- -

- Enhancing economic and cultural strength of certain men within the industry

- -

- Perpetuating unequal gender relations between men, women and so-called “lesser men”

- -

- Promoting men’s breadwinning mentality/responsibility

- -

- Facilitating women’s compliance with traditional female roles (e.g., housewife, teacher, etc.)

- -

- Promoting ideas of continued stability for local businessmen in exchange for their support for the oil and gas industry

These factors are merely headlines to what seems to have become a web of control over local values and principles. To note, “lesser men” in the paper refers to men who are not necessarily assuming dominant roles at work or at home. Spreading ideologies regarding men’s “responsibility” to provide for the family, the appeal of highly competitive salaries in the oil and gas industry and the complementary need for infrastructure, services and businesses to support the industry embeds it within the local community and culture. This example is very interesting as it clearly pertains to the third dimension of power [11] mentioned above, where social ideologies are shaped indirectly by economic demands and the overall stance of the government and the dominant industries.

3. Discussion

Briefly analyzing these examples, we find extractive industries quite problematic to the social world and any hopes for achieving gender and wealth equality as well as natural resource protection and environmental sustainability. Additionally, a high level of entanglement between the economic, social, environmental and political is evident. These case examples support the main argument that patriarchy-imposed gender relations are embedded in communities with large resource extraction industries and have a substantial impact on power relations. The literature provides a comparative narrative of the detriment of “power over” relations within the third dimension of power and the lack of just, equal wealth distribution amongst resource extractive communities around the world, and in particular between both binary genders [1,2,21,27]. I mentioned earlier that patriarchy and capitalism are also linked to violence and war. While violence amongst humans is not a central theme of this paper, perhaps the argument of Christ [17] can be applied to extractive industries; or in other words, violence against nature. Christ argues that the existence of capitalism and uneven wealth distribution is based on shameful atrocities against indigenous people and their land. If we translate that to extractive industries we find the same narrative, where wealth accumulation that is coupled with patriarchy is based upon the unjust exploitation of natural resources, women and non-binary genders.

Gender dynamics and relations in extractive industries and the extent to which patriarchy is reflected and how it is reflected on women and men separately is seen in both case studies and creates a basis for further research. I argue that gender dynamics are more complex than commonly described and should be evaluated accordingly; for example, women should not be presumably victimized in all cases [16]. Recognizing the importance of understanding these intricate relationships would provide more established research outcomes to influence policy-making and promote gender equality and natural resource justice. An intricate example demonstrating the complex diversity of gender dynamics is that found by Reed [28], where she examines gender perspectives in a forestry community in British Columbia, Canada. Not only do her findings contradict the dominant theories regarding an assumed relationship between women and nature, but they also illustrate the diversity of perspectives within groups of women and the interconnectedness of these issues, or as she refers to it, the notion of embeddedness that includes a plethora of influencing factors on social ideologies. This highly resonates with the argument of queer ecology and ideally demonstrates the potential for accepting a non-dualistic world [7].

The first example from Bolivia demonstrates the changing of ideologies as a result of power over, or the thirst for pursuing positions of power at any cost [21]. This example is also found to reiterate the deep rootedness (or embeddedness) of patriarchy in all aspects of the modern-day social world. The Pennsylvania example similarly illustrates the extent of patriarchal influence on the social weave of the resource extractive city as developed over time [1]. The social pressures on women and men to each assume certain roles and abide by them no matter what for the economic well-being of the city, and the dominant capitalistic paradigm calling for the pursuit of power but never achieving it, unveils a part of the problem lying at the intersection of power, patriarchy and gender in resource extractive societies. This may have the potential for extrapolation to many countries around the world, if not all of them.

Similar examples can be seen in different places across the world where natural resource exploitation and economic dependence reproduce patriarchal structures in society and further inequalities. While it does not directly address extractive industries per se, Lough [29] discusses agriculture, which is a resource intensive industry, as an example of embedded patriarchal traditions and control over resources and social norms alike. The author also discusses patriarchy from an operational lens and relates it to global institutions such as “development” and highlights how power over is manifested through these normalized and legitimized efforts. Additionally, he links patriarchy, power and mass media, uncovering hidden agendas and the structured silencing of such potential power relation disruptive notions. Botswana provides another relevant example where patriarchy is tied to land rights [15]. Women’s strict land ownership rights versus men reaffirms disparities between the two binary genders relative to natural resource ownership. One important distinction offered by Botswana’s case is the finding that women empowerment initiatives, including economic participation and political leadership, have to a certain extent weakened “traditional patriarchal structures, attitudes and practices” [15] (p. 237). However, over-emphasizing the apparent weakening of patriarchy occurs at the expense of concealing re-emerging gender inequalities and the development of new forms of male “power over” females, producing counter-effective results.

Another example can be found in Ross [27], where he hypothesizes that one of the main reasons women in the Middle East are not reaching equality rates similar to Western countries is the abundance of oil and petroleum industries in the area through analyzing the demographics of labor. He argues that the fact that there are disproportionately more men than women in the industry is an indication of women’s political influence and subsequently political participation. Through mapping out the relationship between oil production and female political influence, we find that a rise in the former leads to a reduction of the latter, which is supported by statistical analyses [27]. Although there have been critiques of this highly quantitative method of analysis, it is uncontested that the low political involvement of women in oil producing countries reaffirms traditional patriarchal institutions and values and limits the space for alternative institutions/voices.

Perhaps the most prominent example which comes to mind when reading this paper is that of Trump’s America. While it would have resonated with the research problems discussed here substantially, I believe this case study requires multiple papers in succession to address the plethora of social, economic, political, cultural issues. The attempts to “make America great again” have resulted in more of a dysfunctional system of governance coupled with extreme resource exploitation, social discrimination and much more, leaving researchers and non-researchers alike in agony and frustration. Castrellon et al. [30] (p. 936) describe Donald Trump as “not simply a presidential figure, but the embodiment of white supremacy, capitalism, racism, neoliberalism, patriarchy, xenophobia, Islamaphobia, homophobia, and more”. The paper adopts a creative method of portraying reflections, hopes and feelings in the face of exacerbated inequalities. It would certainly be a topic of interest moving this area of inquiry forward. Relying on unorthodox methods like those used by Castrellon et al. [30] might be appropriate since traditional analysis and problem-solving methods have failed to address these issues. The benefits and potential value of questioning all preconceived notions and assumptions, a rule often taught in academia, is perfectly illustrated by Reed [28] and is called for by queer ecologists [7]. This illustrates that women have different feelings regarding the environment, regardless of their “mothering” situation, and that power has the potential to influence women and men’s perspectives through social, political, economic and environmental pressures/factors.

Flaws in research on power, especially pertaining to international politics, can be linked to the reliance on only one form of power conception [2], which is addressed in the assessment of both examples and shows a few of the different forms of power in practice, specifically within the Pennsylvania case study. Research on social systems and their constituents requires a multi-method, interdisciplinary approach, drawing comprehensively on the background and history of all-encompassing factors. It is important to include environmental, cultural and historical epistemologies and contexts as well as intersectional factors such as anemic economic growth, corruption, and state capture amongst others [31].

4. Conclusions

Extractive industries and capitalistic governance systems have gone hand in hand with patriarchy and uneven distribution of power all over the world. Importantly, nature and natural resources are given the least attention in the pursuit of power under patriarchy [17]. This is not to say that a hierarchy of attention exists when valuing the environment and/or all genders. On the contrary—and as theorized in queer ecology—the relationship between power, gender and resources and the more-than-human world is entangled in a diverse spectrum of connections and interactions. Thus, it is important to note the meaning and true value of rejecting dualisms where naturecultures reject claims that nature is a blank canvas that has been given value through culture, and is mute and immutable, as nature has an intrinsic value that impacts human life [5,7].

The importance of this study is that it acknowledges such intertwined, highly complex relationships between all the factors mentioned above. Attempting to address patriarchy, for example, cannot be done without examining power relations, capitalism, gender roles, perceptions on nature and environmental rights, to name a few [31]. Isolating any of these from the rest will not only develop disparities but may also exacerbate problems further. Ensuring important claims to this paper are addressed in the literature is one way to avoid a narrow analysis and insignificant links between patriarchy and different industries. Research collaborations and interdisciplinarity are desperately needed to advance this area of research and realize tangible results through formulating theoretical frameworks, methodologies and solutions [14,15,16,17,18].

Perhaps the world requires a new lens that uncovers all the underlying injustice beyond resource extractive industry’s patriarchy and capitalism as a whole. It is illogical to continue living obliviously in a world which is falling apart environmentally, socially, culturally and economically while thinking that maximizing profits is the main goal. Advancing research in this area can have substantial impacts in all decision-making venues and unprecedented progress on sustainability dreams and hopes. I urge researchers to adopt a similar social theory framework when exploring empirical evidence of these issues and to investigate beneath the surface, regardless of any institutional challenges or preconceived power/patriarchal influence.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge Chloe Taylor for her ongoing support and enlightenment while I wrote this paper.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Filteau, M.R. “If You Talk Badly about Drilling, You’re a Pariah”: Challenging a Capitalist Patriarchy in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale Region. Rural Sociol. 2016, 81, 519–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.; Duvall, R. Power in international politics. Int. Org. 2005, 59, 39–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugaard, M. Rethinking the four dimensions of power: Domination and empowerment. J. Polit. Power 2012, 5, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer-Sandilands, C.; Erickson, B. Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire; Indiana University Press: Indiana, United States, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mitten, D. Connections, Compassion, and Co-healing: The Ecology of Relationships. In Reimagining Sustainability in Precarious Times; Malone, K., Truong, S., Gray, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo, S.; Hekman, S. Material Feminisms; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, Indiana, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bauhardt, C. Rethinking gender and nature from a material(ist) perspective: Feminist economics, queer ecologies and resource politics. Eur. J. Womens Stud. 2013, 20, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Power-dependence relations. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, I. Politics in Place: Social Power Relations in an Australian Country Town; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansardi, P. Power to and power over: two distinct concepts of power? J. Polit. Power 2012, 5, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. Power. A Radical View (The Original with Two Major New Chapters, 2nd ed.; MacMillan Education: London, UK, 2005; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dowding, K. Three-dimensional power: A discussion of Steven Lukes’ Power: A radical view. Polit. Stud. Rev. 2006, 4, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H. Capitalism, Patriarchy, and Job Segregation by Sex. Signs 1976. [CrossRef]

- Thakadu, O.T. Success factors in community based natural resources management in northern Botswana: Lessons from practice. Nat. Resour. Forum 2005, 29, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabamu, F. Patriarchy and women’s land rights in Botswana. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, S. Theorising patriarchy. Sociology 1989, 23, 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, C.P. A New Definition of Patriarchy: Control of Women’s Sexuality, Private Property, and War. Fem. Theol. 2016, 24, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, F.D. Theorising patriarchy: The Bangladesh context. Asian. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 37, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millett, K. The Debate over Women: Ruskin versus Mill. Victorian Stud. 1970, 14, 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, S.; Linneker, B.; Overton, L. Extractive industries as sites of supernormal profits and supernormal patriarchy? Gend. Dev. 2017, 25, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, E. Power and Patriarchy: Reflections on Social Change from Bolivia; Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/stateofpower2017-power-and-patriarchy (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- England, J.L.; Albrecht, S.L. Boomtowns and social disruption. Rural Sociol. 1984, 49, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenburg, W.R.; Bacigalupi, L.M.; Landoll—Young, C.H.E.R.Y.L. Mental health consequences of rapid community growth: A report from the longitudinal study of boomtown mental health impacts. J. Health Hum. Resour. Admin. 1982, 4, 334–352. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenburg, W.R. Women and men in an energy boomtown: Adjustment, alienation, and adaptation. Rural Socio. 1981, 46, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S.L. Socio cultural factors and energy resource development in rural areas in the West. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1978. Available online: http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US201302440163 (accessed on 2 December 2018).

- Gilmore, J.S. Boom towns may hinder energy resource development. Science 1976, 191, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, M.L. Oil, Islam, and women. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2008, 102, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.G. Taking stands: A feminist perspective on ‘other’ women’s activism in forestry communities of northern Vancouver Island. Gend. Place Cult. 2000, 7, 363–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lough, T.S. Energy, agriculture, patriarchy and ecocide. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 100–111. [Google Scholar]

- Castrellón, E.L.; Reyna Rivarola, A.R.; López, G.R. We are not alternative facts: feeling, existing, and resisting in the era of Trump. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2017, 30, 936–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P. Petroleum patriarchy? A response to Ross. Polit. Gender 2009, 5, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The domination as structured by patriarchy extends to that of males dominating war as well, which is discussed in the literature. Although it is acknowledged, it will not be elaborated on in much detail in this paper as it is not the main focus (see [17,19]). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).