Abstract

Migrants have disproportionately higher rates of morbidity and mortality when compared to the host population and this reflects the reality of health inequalities in many countries. It is imperative to engage with communities to identify their needs and to include these in the delivery of public health programs and health care services. The aim of this paper is to outline a new approach that systematically ensures that vulnerable groups, such as migrants, can become actively involved and are not simply the passive recipients of program activities. The community engagement framework is based on practical experiences of working in a cross-cultural context in both rural and urban settings and is implemented as seven key steps: 1. stakeholder connection; 2. communication; 3. needs assessment; 4. informing the wider community; 5. strengthening community capacity; 6. building partnerships; and, 7. follow-up. The framework offers a flexible template that can be used to engage with vulnerable groups in future public health programs.

1. Introduction

Globally, many countries are experiencing an unprecedented flow of migrants. This pace is likely to accelerate, in Europe; the events in North Africa and the Middle East continue to raise migration via the Mediterranean. In 2015, the number of international migrants worldwide (people residing in a country other than their country of birth) was the highest ever recorded having reached 244 million (from 232 million in 2013) [1]. The internationally agreed definition for a migrant is broad and could apply to a number of contexts but it is used in this paper as ‘any person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of (i) the person’s legal status; (ii) whether the movement is voluntary or involuntary; (iii) what the causes for the movement are; or, (iv) what the length of the stay is’ [2]. Many migrants come from countries where poverty has impacted on the quality of health-care systems and where there is a mistrust of government services, a situation that can be made worse by restricted legal rights and different language, spiritual, and cultural beliefs [3].

It is imperative to engage with communities in public health programs in order to identify their needs. This is especially important for vulnerable groups such as migrants but could apply to other contexts including people affected by disease outbreaks and health emergencies. The aim of this paper is to outline a new approach that ensures that people are actively involved in the delivery of public health programs and health care, and are not simply the passive recipients of information and services. To contextualize the new approach that is presented in this paper, it has been discussed in the context of migrant population groups.

Migrant communities function in a similar way to any other community. They occupy a spatial dimension, such as a rural village, a temporary camp, an urban or slum neighbourhood, or a virtual space or place, and a non-spatial dimension that involves relationships between people. Within the geographic dimensions of a community, multiple sub-communities often exist and individuals may belong to several of these ‘interest groups’ at the same time. Interest groups exist as a legitimate means by which individuals are organised around a variety of social activities, for example, funerals, or to address a shared concern, for example, dissatisfaction with local healthcare services [4]. Within the dimension of a community ‘settings’ offer a social context in which migrants engage in daily activities including in schools, workplaces and hospitals. Settings are used to promote health by reaching the people who occupy them, by raising awareness, developing skills, gaining better access to services, improving the physical environment, or strengthening organizational structures [5]. In a school setting, for example, a program can engage with teachers, students, migrant parents, and health providers and it has been used in Belgium when a migrant child has a problem such as missing classes. The aim is to clarify the problem and involve parents in its solution by understanding their rights, responsibilities and obligations toward their own child’s school success. The approach is tailored to address migrant needs and to find ways to motivate an interest in their children’s education [6].

The ‘point of entry’ into a migrant community can be effectively made through community-based organisations, a mechanism that has been used by government and non-government programs [7]. Community engagement should be a collaborative process between an agency and a community to decide an appropriate direction, however, in practice it is usually led only by the agency that controls the situation, for example, by identifying the key health issues to be addressed. Community engagement can be used to coerce the community into participating in program activities without identifying local needs or using local capacities. The key issue is whether the agency wants to help to empower the migrant community or to simply promote participation in a program that the agency is being employed to deliver [8].

2. A Framework for Engaging Migrant Communities

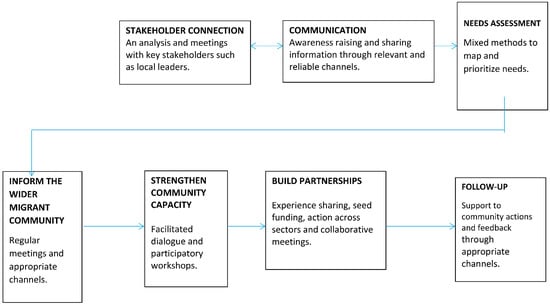

The unfamiliarity with a specific cultural context can make it more difficult to understand the reality of the situation and this can influence the delivery of services. A team comprising both practitioners and migrants can provide the most suitable approach when working in a cross-cultural context. Language often presents issues for how people communicate across cultural divides, for example, during face-to-face consultations. However, intercultural communication is not only about language and although interpretation services are important [9] culture determines how migrant communities function at a local level and how they may or may not uptake healthcare services. The following framework (see Figure 1) uses a systematic approach through seven key steps to help overcome cross-cultural issues to engage with communities: 1. stakeholder connection; 2. communication; 3. needs assessment; 4. informing the wider migrant community; 5. strengthening community capacity; 6. building partnerships; and, 7. follow-up.

Figure 1.

Engaging with vulnerable communities.

The key steps in the framework have been developed and used elsewhere in attempts to engage with communities, including stakeholder analysis, needs assessment, and communication. The methodologies for each step are therefore not discussed in detail in this paper. What is new about the framework is that it is based on extensive practical experiences [10] of working in a cross-cultural context in both rural and urban settings that were collated from discussions with both Practitioners and community representatives during the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak in West Africa. This context provided the opportunity to consult with many people involved in community engagement in a large scale and concentrated public health program. The framework offers a systematic template for the engagement with vulnerable groups in future public health programs.

2.1. Stakeholder Connection

There is always a power relationship between any outside agency and the range of people with whom they work. These people are often described as the program stakeholders and include the primary stakeholders, the community, at whom services, information, and resources are targeted, for example, women, adolescents, and men. Secondary stakeholders act as an intermediary in the delivery of the services, for example, non-government organisations or private health promotion agencies. The stakeholders are identified during the planning phase and may specifically target the marginalised in different socio-economic and cultural groups that are excluded from preventive, treatment, and rehabilitation services [11].

Westernised concepts such as community engagement can be interpreted differently in different cultural contexts. In practice, it is therefore better to use local interpretations of the concepts as a ‘working’ alternative to using professional or technical terminology. The purpose is to provide all stakeholders with a more mutual understanding of the aim of the program, and in which the primary and secondary stakeholders are involved and toward which they are expected to contribute, for example, by giving up their time or by using local resources. The identification of a ‘working definition’ of the key concepts that are used in the design of a program can be refined by using simple qualitative approaches, such as focus groups during the design phase and involving the stakeholders [12]. Working in urban neighbourhoods is quite different from a working in a rural context and the engagement may start with the city authorities alongside collaboration with local enforcement and administrative authorities. A standard operational procedure for community engagement, especially with stakeholders in densely populated, urban neighbourhoods has not yet fully emerged and requires urgent professional attention.

2.2. Communication

Communication is a key strategy that is used by agencies for the purpose of providing information that will help to maintain people’s involvement in the program, but also to help them to protect and improve their health status. The communication approach focuses on the transfer of knowledge about a particular health issue, for example, information about the symptoms of diabetes. With this newly acquired information, vulnerable people can then make an informed decision about, for example, if they should seek further advice from a health professional. An informed choice is one that is based on relevant knowledge about health behaviour and the perceived risk that is associated with a wrong choice, consistent with the decision-maker’s values and behaviour [13]. However, because of the complex social and cultural circumstances associated with behaviour change an individual may also choose not to make healthy choices or positive changes to their lifestyles, even if they have been well informed. In part, this is because making the healthy choice is not always an easy option due to the lack of a supportive or equitable environment including access to health care services [14]. Successful communication campaigns have achieved improvements in the level of awareness and have changed specific behaviours using social marketing, peer education, and the social media. The communication strategy has used many techniques including edutainment, health journalism, interpersonal, advocacy, risk communication, and culture-specific activities, such as story-telling. However, the evidence is mixed, seemingly working in some contexts, but not in others. Communication campaigns must use a comprehensive approach by including a range of techniques and tailored and community-led interventions that are culturally appropriate and that reinforce key health messages [15].

2.3. Needs Assessment

Needs assessment is used to identify the needs that are reported by an individual, group, or community, and the resources and outcomes that are required [16]. Migrants do have specific health needs that may result, for example, from their exposure to conflict causing stress and anxiety that can consequently have a direct effect on their physical and mental health. However, the diversity of some migrant communities can create problems in regard to the exclusion of specific groups. The participation can then become empty and frustrating for those whose involvement is passive and can have a negative effect on the success of a program or allow those in authority to claim that all sides were considered whilst only a few benefit [17]. In practice, who will participate in the needs assessment is essentially decided through the representation of a few on behalf of the majority, for example, the elected representatives of a migrant community. This is because it is not usually possible for everyone to participate in the needs assessment, even when using participatory methods. There is therefore a professional responsibility to ensure that all groups are represented in the needs assessment.

2.4. Informing the Wider Community

Informing the wider community during the ongoing implementation of a public health program is important so that people understand about any progress and about any problems.

Informing the wider migrant community is usually achieved through regular updates and the dissemination of information through appropriate channels. For example, in New Zealand, language barriers and a lack of resources translated into Chinese were identified as the key reasons for failing to engage with local services by Chinese migrants. These issues were resolved by the use of appropriate communication channels including social media, public meetings and radio broadcasts and by working with the network of Chinese community-based organisations [18].

2.5. Strengthening Community Capacity

Capacity building is the process to strengthen knowledge, skills and competencies. Community capacity building increases people’s abilities to define, assess, analyse, and act on health (or any other) concerns of importance to themselves [19].

Capacity building has been ‘unpacked’ into nine ‘capacity domains’ that represent the factors that allow for people to better organize and mobilize themselves towards gaining greater control over their lives. The capacity domains have been successfully implemented as a tool to strategically plan for action and to evaluate the outcomes [20], as follows:

- a period of observation and discussion is important to firstly adapt the approach to the social and cultural requirements of the participants;

- action is achieved through strategic planning for positive changes in the nine domains at a community level based on: Identifying specific activities; sequencing activities into the correct order to make an improvement; setting a realistic time frame including any targets; and assigning individual responsibilities to complete each activity within the program time frame; the resources that are necessary to improve the present situation; and,

- each domain is measured and graphically displayed to compare changes in capacity.

2.6. Building Partnerships

Partnerships demonstrate the ability of a community to develop relationships to be better able to collaborate. This may involve an exchange of services, pursuit of a joint venture based on a shared goal or an advocacy initiative to change policy. The purpose of a partnership is to grow beyond local concerns and to take a stronger position on broader issues through networking and resource mobilisation [21].

Partnerships help to build the capacity of the community through an expanded membership and resource base. In turn, this provides communities with the ability to have a greater collective influence and the ability to better mobilize resources. The STI/HIV prevention program in Amsterdam, for example, worked with migrants to promote sexual health through creating a partnership, providing a grant scheme and the support by health professionals. In particular, the involvement of community-based organisations in partnership with government services so as to include the experiences of migrants in the implementation of the program demonstrated the potential for future success in achieving the program goals [7]. The Stadtteilmütter (Neighbourhood Mothers) project in Berlin used the inclusion of mothers from different nationalities in partnership with local authorities to empower migrant families by informing them how to better access information, resources and services [22].

2.7. Follow-up

The purpose of follow-up is to maintain contact with the community, to inform them and to ensure that the community and its leaders continue their support for ongoing program activities.

Follow-up activities involve supporting and encouraging communities to continue working with the program, sharing information about available services and resources and opportunities to provide inputs into the implementation of specific interventions. The follow-up can use a range of channels of communication such as on-line community notice boards, the social media or texting or arrange face to face meetings at gatherings in communal settings such as in health centres, youth centres or ‘hubs’, that are centres where mixed-services are provided to migrants.

3. Conclusions

Vulnerable groups including migrants have disproportionately higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to the host population and suffer greater health inequalities. They often have specific health needs and it is imperative to engage with them to identify these needs and to include them in the delivery of public health programs and health care services. This paper outlines a new approach that systematically ensures that vulnerable people can become actively involved in public health programs and that they do not merely become the passive recipients of information, resources, and services. The community engagement framework has not been tested in its entirety, but most of the seven key steps have and its flexibility permits it to be applied in both rural and urban settings. The framework offers a template that can be adapted and used in future public health programs and the author would be interested to hear about other experiences of using the framework approach in different contexts.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). Operational Portal. Mediterranean Situation. 2018. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean (accessed on 23 September 2018).

- International Organization for Migration. Key Migration Terms. 2017. Available online: https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Napier, D.; Ancarno, C.; Butler, B.; Calabrese, J.; Chater, A.; Chatterjee, H.; Guesnet, F.; Horne, R.; Jacyna, S.; Jadhav, S.; et al. Culture and Health. Lancet 2014, 384, 1607–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakus, J.D.L.; Lysack, C.L. Revisiting community participation. Health Policy Plan. 1998, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; Wills, J. Foundations for Health Promotion, 3rd ed.; Bailliere and Tindall: Edinburgh, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cherkezova, S.; Tomova, I. An Option of Last Resort? Migration of Roma and Non-Roma from CEE Countries; Roma Inclusion Working Papers; UNDP Europe, Bratislava Regional Office: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wagemakers, A.; van Husen, G.; Barrett, J.; Koelena, M. Amsterdam’s STI/HIV programme: An innovative strategy to achieve and enhance the participation of migrant community-based organisations. Health Educ. J. 2015, 74, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G. The challenge of behaviour change and health promotion. Challenges 2017, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglieri, F.; Colucci, A.; Barbina, D.; Fanales-Belasio, E.; Luzi, A. Communication and cultural interaction in health promotion strategies to migrant populations in Italy: The cross-cultural phone counselling experience. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 2013, 49, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Laverack, G. Health Promotion in Disease Outbreaks and Health Emergencies; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials; UNAIDS/07.30E/JC1364E; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cass, A.; Lowell, A.; Christie, M.; Snelling, P.L.; Flack, M.; Marrnganyin, B.; Brown, I. Sharing the true stories: Improving communication between Aboriginal patients and health care workers. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 176, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dormandy, E.; Michie, S.; Weinman, J.; Marteau, T. Variation in uptake of serum screening: The role of service delivery. Prenat. Diagn. 2002, 22, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laverack, G. The Pocket Guide to Health Promotion; Mc-Graw Hill Education: Maidenhead, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, E.; Diop, N.; Laverack, G.; Leye, E. What works and what does not: A discussion of popular approaches for the abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2013, 2013, 348248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, G. Needs and Capacity Assessment for health Education and Health Promotion, 4th ed.; Jones and Bartlett Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, L.; Fozilhujaev, B.; Tashbaeva, C.; Djamankulova, K. Community Development in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan; Occasional Paper Number 40; INTRAC: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, S.; Laverack, G.; Nayar, S.; Foroughian, S. Community engagement for health promotion: Reducing injuries among Chinese people in New Zealand. Health Educ. J. 2011, 70, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonte, R.; Laverack, G. Capacity Building in Health Promotion, Part 1: For Whom? And For What Purpose? Crit. Public Health 2001, 11, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G. Community Capacity Building. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life Research; Michalos, A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://refworks.springer.com/mrw/index.php?id=2801 (accessed on 23 September 2018).

- Laverack, G. Health Promotion Practice: Power and Empowerment; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Good Ideas. Neighborhood Mothers Leading the Way in Neukölln, Germany. 2013. Available online: http://citiesofmigration.ca/good_idea/neighbourhood-mothers-leading-the-way-in-neukolln/ (accessed on 23 September 2018).

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).